Abstract

Objective:

Our study analysed evolving regional commitments on food policy in the Pacific. Our aim was to understand regional priorities and the context of policy development, to identify opportunities for progress.

Design:

We analysed documentation from a decade of regional meetings in order to map regional policy commitments relevant to healthy diets. We focused on agriculture, education, finance, health, and trade sectors, and Heads of State forums. Drawing on relevant political science methodologies, we looked at how these sectors ‘frame’ the drivers of and solutions to non-communicable diseases (NCD), their policy priorities, and identified areas of coherence and tension.

Setting:

The Pacific has among the highest rates of non-communicable diseases in the world, but also boasts an innovative and proactive response. Heads of State have declared NCD a ‘crisis’ and countries have committed to specific prevention activities set out in a regional ‘Roadmap’. Yet, diet-related NCD risk-factors remain stubbornly high and many countries face challenges in establishing a healthy food environment.

Results:

Policies to improve food environments and prevent NCD are a stated priority across regional policy forums, with clear agreement on the need for a multi-sectoral response. However, we identified challenges in sustaining these priorities as political attention fluctuated. We found examples of inconsistencies and tension in sectoral responses to the NCD epidemic that may restrict implementation of the multi-sectoral action.

Conclusion:

Understanding the priorities and positions underpinning sectoral responses can help drive a more coherent NCD response, and lessons from the Pacific are relevant to public health nutrition policy and practice globally.

Keywords: Pacific, Non-communicable diseases, Food policy, Nutrition policy, Priority-setting

Non-communicable diseases (NCD) are currently the leading cause of death in the Pacific, and are expected to remain so. In 2016, NCD were responsible for 68·6 % of all deaths in the region, and of these more than two-thirds were premature( 1 ). By 2040, four of the top five causes of death in the Pacific will be NCD( 2 ). The scale of the epidemic is having a dramatic impact on health outcomes, causing a reversal in life expectancy in at least one Pacific country, Tonga( 3 ). In addition to the human toll, there are significant impacts on the health system, productivity and economic growth( 3 ).

Globally, the threat posed by NCD is recognised by the inclusion of a target on NCD in the Sustainable Development Goals and the UN Decade of Action on Nutrition, 2016–2025( 4 , 5 ). The Pacific has played a lead role in the global response. Pacific Heads of State declared an ‘NCD crisis’ in 2011 and some Pacific countries have been amongst the first, globally, to introduce taxes on unhealthy food( 6 , 7 ) now accepted as a key policy response to NCD( 8 , 9 ).

However, progress has not been as rapid as hoped, especially on diet-related risk factors. In many Pacific countries, the prevalence of overweight and obesity, including childhood obesity, continues to rise( 10 ). In 2016, ‘high-plasma fasting glucose’ (diabetes) and ‘dietary risks’ (e.g. diets high in salt, fat and sugar) were linked to almost 40 % of all deaths( 1 ). The challenge of addressing diet-related NCD is exacerbated by the Pacific’s food environment: there is limited domestic food production, fresh food is rare, and imported, processed goods dominate diets. This has contributed to the transition towards more unhealthy diets( 11 ).

The WHO recommends a coordinated response across a range of sectors to improve diets and nutrition, encompassing agriculture, food supply, fiscal and retail( 9 ). However, studies suggest that operationalising a coherent policy response on food and nutrition issues is challenging in practice, given the different sectoral drivers and incentives( 12 – 14 ). As an example, there are tensions between policies to create a healthy food supply (e.g. by decreasing consumption of unhealthy processed food) and policies to improve the productivity of the agricultural sector (e.g. by adding value to the supply chain through processing) and facilitate trade( 15 ). Equally, manufacturers and retailers may resist efforts to reduce consumption of unhealthy products through price increases and restrictions on marketing( 12 , 16 , 17 ).

Cross-sectoral tensions are also noted in the Pacific, with policymakers and stakeholders reporting challenges engaging across sectors on food and nutrition issues, and different sectoral positions – for example between the food industry and health sectors – creating barriers to coherent policy development( 18 – 20 ). These challenges are exacerbated when there is no clear lead within government on food and nutrition issues, as is often the case( 12 , 16 , 18 ).

Further, studies suggest that the way different sectors understand or ‘frame’ nutrition influences their response( 21 ). An economic framing (i.e. poor nutrition is the result of poverty) will lead to a different set of policy actions to a health or agricultural framing, which may champion nutrition education, incentives for healthy eating, for example( 22 ). These different understandings can lead to lack of policy coherence, understood as ‘the systematic promotion of mutually reinforcing policies across government departments to create synergies towards achieving agreed objectives and to avoid or minimise negative spillovers in other policy areas’( 23 ).

The Pacific context

There are twenty-two Pacific island countries and territories spanning Melanesia, Polynesia and Micronesia. These nations comprise hundreds of islands, scattered over an area equivalent to 15 % of the globe’s surface. The majority are low or middle-income countries, and they are among the highest per capita aid recipients in the world( 24 ). Progress on both human and economic development is mixed and slower than in other regions of the developing world( 25 ). This is partly due to the small population size of many countries and territories, which has limited on-island expertise and institutional capacities: all Pacific countries except Papua New Guinea have populations of under 1 million( 25 ) and the smallest, Niue, has just 1600 people.

The key political body in the region is the Pacific Island Forum (PIF), which has fifteen members. The Pacific Community (SPC) is a technical and scientific agency providing support to all twenty-two countries. The WHO, FAO and World Bank also operate in the region and are active on NCD. Given the small country sizes, regional fora are particularly important in the Pacific. They are used to develop regional policies on issues of common interest, share experience on common challenges, and have been influential in the Pacific’s NCD response( 17 ). Many Pacific countries thus rely on regional bodies, and technical agencies, to provide skills and expertise not available domestically and for advice on policy development and implementation.

Previous studies, predominantly from high-income countries, have noted limited but growing use of political science methodologies to explain nutrition policies( 21 ). In the current study, we use records from regional forums to understand the priorities and context of policies relevant to diet-related NCD in the Pacific, to help identify opportunities to accelerate progress. To our knowledge, this is the first study to analyse the content and framing of food and nutrition issues at regional level in the Pacific. Findings are likely to be relevant to public health nutrition policy and practice globally, given the high burden of diet-related NCD in the region.

Methods

We used content analysis to examine the priority given to diet-related NCD by policy-makers in the Pacific region and analysed coherence in NCD-related policy commitments across sectors. Our research questions were:

What has been the evolution of the policy space at regional level for key aspects of diet-related NCD policy?

How do different regional sectoral groups (comprising predominantly state actors) conceptualise or frame the drivers of the NCD epidemic and responses to it?

What are the areas of coherence, inconsistency and tension between these different priorities and framings and what are the implications for effective action on NCD?

Frameworks for analysis

Both data extraction and content analysis were guided by theories of policy-making. We drew on elements of Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework( 26 ) because of its emphasis on identifying policy actors’ core beliefs and values as influencers of actors’ understanding and their subsequent policy responses. Core beliefs are defined as ‘normative beliefs’, such as the importance of individual freedom versus social equality; while values relate to perceptions of the relative priority of different policy goals and the seriousness of a ‘problem’; approaches to addressing the problem, and the role of different actors, including the state. We also drew on a policy space analysis framework – which considers the ‘space’ or scope actors have to shape and drive policy agendas and has been used to trace the evolution of health policy agendas – to inform our analysis of policy content over time( 27 , 28 ). Drawing on both frameworks, we examined how the substance of policy action recommended differed over time, and analysed revealed beliefs and frames of different sectoral actors (i.e. in policy statements).

Data collection

We used the WHO’s NCD Global Action Plan( 9 ) to determine sectors most relevant to food and nutrition policy, and then searched electronically to identify which of these sectors held significant meetings involving ministers or heads of sector (i.e. the chief civil servant) in the Pacific. We focused on high-level meetings where participants have a mandate to make or implement policy. In addition to Leaders (Heads of State) meetings, we identified: finance and economy; agriculture; health; trade; education; trade and foreign affairs as relevant sectors which also convened regular, high-level meetings.

We searched online for documents from these meetings from 2008 to present. A ten-year time frame was chosen as sufficient to track the evolution of policy, and because NCD have risen to prominence globally in this period, with the first UN High Level Meeting (HLM) on NCD held in 2011, and the most recent in 2018. We included three types of documents in our analysis: communiqués or outcome statements (short documents reflecting key decision points); meeting reports (these contain more detail on meeting discussions); and regional strategies or plans endorsed at these meetings. Documents not available online were requested from Pacific and UN agencies involved in convening meetings. Given the limited number of trade meetings (see below), we also reviewed the Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic Relations (PACER) Plus trade agreement.

We excluded from our analysis summaries of workshop sessions held within high-level meetings and expert- or country-level presentations made to these meetings, on the grounds that these did not necessarily have collective endorsement. We also excluded meetings attended by more junior officials, as these were not decision-making meetings.

Data analysis

We took two approaches to document analysis, drawing on identified political science methodologies. First, we analysed the content of regional policies by sector. To do this, we developed a data extraction framework in Microsoft Excel 2016, which: (i) listed key policy actions and responses on diet-related NCD (again based on the WHO Global Action Plan); and (ii) considered aspects of how the NCD problem is ‘framed’ through questions such as ‘who should take action on NCD’, ‘why are NCD a problem’ and ‘what would be the most effective policy response’ (see supplementary material). We then searched each document for text relevant to these categories, developing one spreadsheet per sector. Second, we compared spreadsheets to identify areas of coherence, opportunities and tension in relation to the NCD response. Four authors (RD, ES, ER and AG) worked on data extraction, with each author taking the lead on one or more sectors. RD and AMT compared all spreadsheets for consistency, and conflicts were resolved by consensus.

Findings are presented as follows: first, the policy space analysis on the evolutions relevant to diet-related NCD in the Pacific; second, sectoral framings of NCD and specific policy priorities discussed at regional meetings; third, areas of tension and opportunities. We then discuss the implications of our findings for maintaining momentum on diet-related NCD; highlight areas where progressing policy may be challenging due to different sectoral framings; and the role of regional institutions. We also make recommendations on priorities for the future NCD response.

Results

We identified fifty-eight relevant regional forums covering six sectors, as well as Heads of State meetings (Table 1) and reviewed at total of seventy documents related to these meetings. The majority of meetings were political (i.e. ministerial) but we also included eleven head of sector meetings from the health and education sectors only. Available records suggested that finance ministers and Heads of State met annually during the period under review; trade ministers met annually until 2016 while foreign ministers only began meeting in 2016. Health, education and agriculture ministers met every second year, and there was one joint meeting of health and finance ministers. Heads of health met annually from 2013, and heads of education met five times between 2010 and 2017. We also identified three ad hoc multi-sectoral meetings held in the Pacific relevant to diet-related NCD prevention during the period relevant to our study: the Food Secure Pacific Summit (2010, attended by agriculture, health and trade sectors); the Conference on Small Island Developing States (2014, attended predominantly by Heads of State); and the Pacific NCD Summit (2016, predominantly health representatives with some Heads of State).

Table 1.

Overview of documents analysed and the framing of diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCD)

| SECTOR | No. of meetings reviewed, 2008–2018 | Regional plans | Docs referencing NCD* | Reference to multi-sectoral response? | Main driver of diet-related NCD | Commitment to resource NCD response? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | ||||||

| Leaders | 10 Heads of State | N/A | 7 | 70 | Y | Imported unhealthy food; food insecurity | Y – but no target |

| Finance | 9 Ministerial | N/A | 5 | 55 | Y | Imported unhealthy food | Y – but no target |

| Foreign Affairs | 3 Ministerial | N/A | 0 | N/A | No reference | N | |

| Trade | 7 Ministerial | N/A | 1 | 14 | Y (trade and health only) | No reference | N |

| Health | 5 Ministerial | N/A | 11 | 100 | Y | Imported unhealthy food | N |

| 6 Head of Sector | |||||||

| Agriculture | 4 Ministerial | N/A | 3 | 75 | Y | Imported unhealthy food; decline in local production; poor quality standards | N |

| Education | 4 Ministerial | 1 † | 1 | 11 | N/A | No reference | N/A |

| 5 Head of Sector | |||||||

| Ad Hoc Meetings | |||||||

| Food Secure Pacific | 2010 | 1 ‡ | 1 | 100 | Y | Food insecurity | N |

| SIDS conference | 2014 | N/A | 1 | 100 | Y | No reference | N |

| Joint Health-Finance | 2014 | 1 § | 1 | 100 | Y | Imported unhealthy food | N |

| Pacific NCD Summit | 2016 | N/A | 1 | 100 | Y | Food environment: trade, agricultural production | Y – supported establishment of funding mechanism |

SIDS: Small Island Developing States; N/A: Not applicable; Y: Yes; N: No.

Meetings that issued both a communiqué and meeting report were counted as a single reference.

Pacific Regional Education Framework 2018-2030.

Food Secure Pacific Plan 2010.

Pacific NCD Road Map 2014

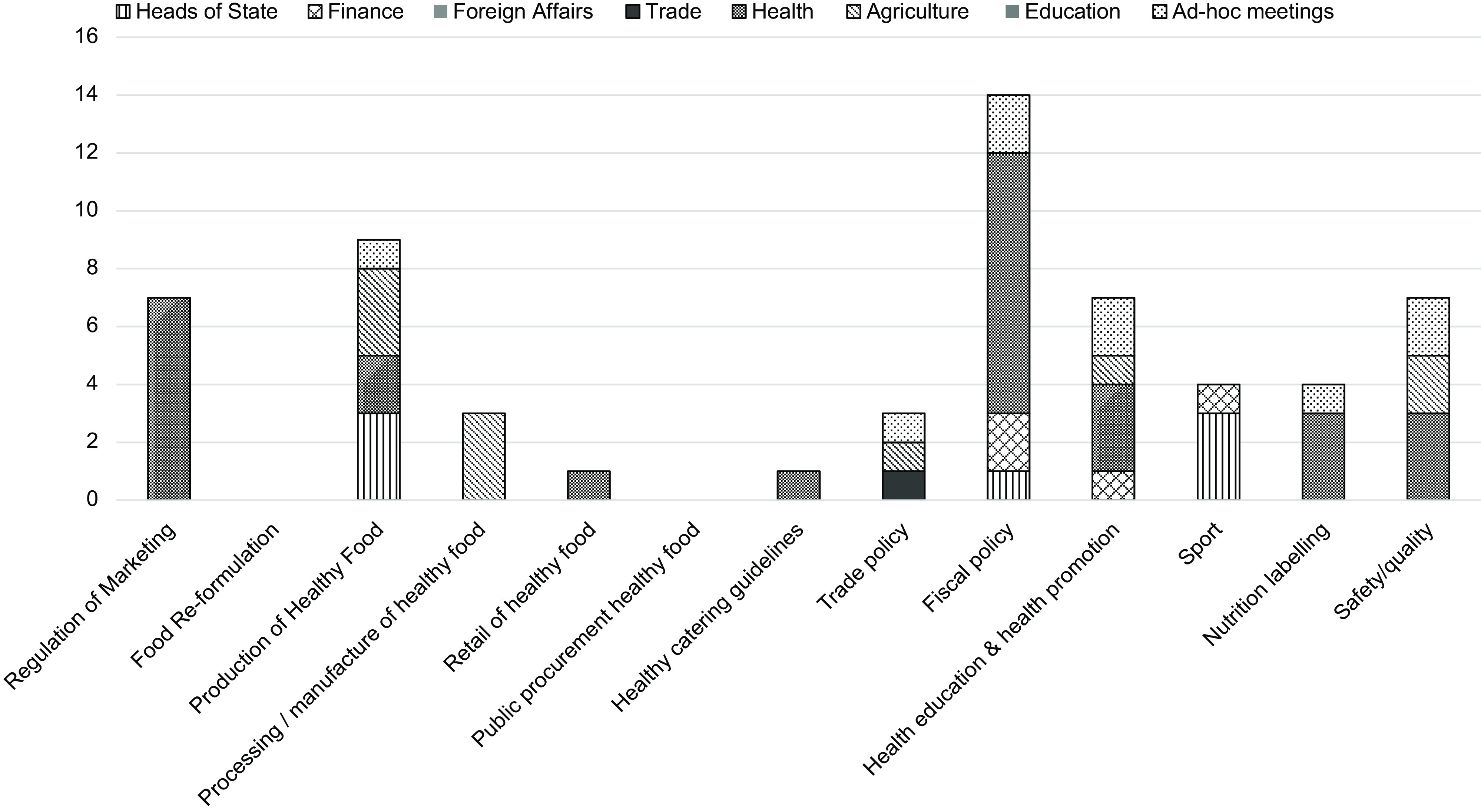

We found all sectors considered diet-related NCD in regional meetings held between 2008 and 2018 (Table 1), with most attention given to fiscal policy (Table 2, Fig. 1). Broadly, we found stronger attention to NCD in the early 2010s, with less articulated commitment from 2015, and early signs of re-prioritisation in 2017–2018. NCD remained framed as a health issue throughout the decade; however, discussion of appropriate policy responses shifted over time from a targeted focus on regulating the food environment to a broader suite of measures encompassing nutrition education, sport and community empowerment.

Table 2.

Proposed actions to improve nutrition and prevent diet-related NCD, by sector

| SECTOR | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heads of State | Sport | Sport | Sport | |||||||

| Fiscal Policy | ||||||||||

| Finance | Fiscal Policy | Education | Fiscal Policy | Sports | ||||||

| Food Production | ||||||||||

| Health | Fiscal Policy | N/A | Fiscal policy | N/A | Fiscal Policy | Fiscal Policy | Fiscal policy | Fiscal Policy | Fiscal Policy | Fiscal policy |

| Marketing* | Quality/Safety | Marketing | Marketing | Marketing | Marketing | Marketing | ||||

| Quality/Safety | Labelling | Education | ||||||||

| Education | Labelling | |||||||||

| Food Production | ||||||||||

| Agriculture | Food Production | N/A | Food Production | N/A | N/A | Food Production | N/A | Increase Trade | N/A | |

| Processing | Processing | Processing | ||||||||

| Quality/Safety | Quality/Safety | Quality/safety | ||||||||

| Education | Education | |||||||||

| Labelling | ||||||||||

| Ad Hoc Meetings | Food Secure Pacific: | Joint Health and Finance: | NCD Summit: | |||||||

| Safety/Quality | Safety/Quality | Fiscal Policy | ||||||||

| Labelling | Fiscal Policy | Trade | ||||||||

| Production | ||||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||

| SIDS: Education |

N/A: No meeting held that year.

‘Marketing’ refers to measures to restrict marketing of unhealthy consumables.

Fig. 1.

Proposed actions to address diet-related non-communicable diseases, by regional meeting (1 count per regional meeting mentioned)

Evolution of policy on diet-related NCD

Box 1 charts the changing policy space for NCD in the Pacific, highlighting milestones in the NCD response from 2008 to 2018. The decade began with a strong focus on diet-related NCD: the 2010 Food Secure Pacific summit( 29 ) highlighted the social and economic challenge of the epidemic and endorsed a regional food security framework focused on unhealthy food imports. In 2011, Pacific health ministers( 30 ) and then Heads of State( 31 ) declared an ‘NCD crisis’. NCD remained a specific topic in Heads of State communiqués in 2012 and 2013, though both reported NCD under the heading of ‘regional health initiatives’, suggesting it was perceived as a health issue( 32 , 33 ). Trade and finance ministers maintained the momentum, both sectors discussing NCD for the first time in 2013( 34 ). In 2014, the first and only joint meeting of Pacific health and finance ministers was held( 35 ) specifically focused on NCD prevention; participants endorsed the Pacific NCD Roadmap Report( 3 ) which has since become a key guiding document for the region. The period of sustained attention on NCD culminated in the 2016 ‘Pacific NCD Summit’( 36 ). Intended as a multi-sectoral event, attendees were predominantly from the health sector, again suggesting NCD were framed as a health issue.

Box 1:

Timeline of significant events

– 2010 Food Secure Pacific Summit

– 2011 Food Secure Pacific Plan launched

– 2011 Pacific health ministers’ issue a communique declaring an “NCD Crisis”

– 2011 Pacific Leaders’ (Heads of State) declare NCDs a “human social and economic crisis”

– 2013 NCDs discussed at finance and economic ministers’ meeting (FEMM) for the first time

– 2014 NCD Roadmap released

– 2014 Joint meeting of health and finance ministers’ endorses NCD Roadmap

– 2014 FEMM agrees to include NCDs as a standing agenda item on FEMM meetings

– 2014 Small Islands Developing States (SIDS) conference issues the SIDS Accelerated Modalities of Action (SAMOA) pathway with specific focus on NCDs

– 2015 Pacific health ministers’ meeting focuses on a 20 year review, ‘Healthy Islands’

– 2016 Pacific NCD Summit: focus on the Pacific NCD Roadmap implementation, and prevention and control of diabetes.

– 2017 Pacific Health Ministers highlight childhood obesity and the Pacific Monitoring Alliance on NCD Action

– 2018 Pacific Leaders highlight childhood obesity

We found fewer expressed commitments on diet-related NCD prevention from the middle of the decade. The 2014 and 2016 Heads of State communiqués did not include a specific section on either health or NCD (though statements annexed to these declarations, on Oceans( 37 ) and Fisheries( 38 ) did cross-reference the epidemic). The 2015 and 2017 communiqués made no mention of NCD at all. In the same period, finance ministers’ reiterated their commitment to NCD but also noted ‘mixed progress in implementing the Roadmap’( 39 ).

Framings of diet-related NCD, their causes and the most effective interventions, shifted over the course of the decade in response to the evolving policy space. Health ministers initially singled out heart disease, cancer and diabetes as priority NCD( 30 ) and commitments focused on specific nutrients within the food supply, such as an agreement to develop targets on fat, sugar and salt as an enabler of fiscal and regulatory measures( 40 ). The NCD Roadmap also advocated a targeted approach, urging countries to prioritise measures to address diet, alcohol and tobacco consumption. However, towards the middle of the decade, looser commitments on ‘expanding health promotion and protection’ emerge. While all sectors continued to reference unhealthy diets, linked to highly-processed imported foods, as contributing to diet-related NCD (see Table 2) a broader definition of NCD was also embraced, to include rheumatic heart disease and mental health( 41 ) alongside a greater focus on individual behaviour and community empowerment( 42 ) as response mechanisms. There were signs of a shift back to a narrower focus on nutrition and diet-related NCD over the last two years: the 2018 Heads of State communiqué included a specific reference to childhood obesity( 43 ) following a strong focus on this issue at the 2017 Health Minsters’ meeting( 39 ).

Sectoral analysis

In summary, we found many sectors shared similar values (in Sabatiers’ definition) on the importance of NCD and how to tackle them. NCD were a high priority for Heads of State and the health sector, and received significant attention from agriculture and finance sectors. The contribution of trade and specifically unhealthy food imports to diet-related NCD was a consistent theme across sectors, although there were no specific commitments on reducing these imports. Interventions most frequently referenced as effective responses were fiscal measures (mainly taxes on unhealthy products) and nutrition education, with other actions to promote nutrition less visible. Heads of State, finance, health and agriculture all expressed concern for the social and economic consequences of NCD, beyond health, and all acknowledged that a multi-sectoral response was critical (Tables 1 and 2). Although multi-sectoral action was widely recognised as critical to the NCD response, we found no examples outside the health sector of regional meetings committing to specific, inter-sectoral actions or collaborations.

Leaders (Heads of State)

Pacific Heads of State have shown strong interest in NCD issues (Table 1), framing the epidemic as a ‘human social and economic crisis’ owing to high levels of premature death, lost productivity and increased healthcare costs( 31 ). Food insecurity and unhealthy, imported food were identified as drivers of NCD( 37 ) and the importance of influencing dietary choices was noted( 31 , 43 ). In their 2011 NCD declaration, Leaders’ committed to five NCD policy responses including reduction of salt, fat and sugar consumption. However, while later Leaders’ meetings continued to acknowledge the seriousness of the NCD challenge and its drivers, the only response interventions specifically mentioned in subsequent communiques were sports-promotion programmes.

Finance and economy

Finance and economic ministers’ emphasised the unsustainable costs associated with NCD and implications for the economy( 35 ) and private sector( 44 ). Foods high in sugar, salt and fat, including imported foods, were highlighted as a driver of NCD( 35 ). The policy response mentioned most frequently by this group was taxation targeted at NCD risk factors (Table 2). Only tobacco taxation was specified, although taxation of unhealthy consumables was implied in mention of ‘taxes to support behaviour change’( 45 ).

Agriculture

Agriculture stakeholders framed the rise in NCD prevalence as linked to declines in local food production, volatile food prices and the rise of imported, low-quality foods( 46 – 48 ). Further, agriculture leaders framed a more resilient and productive agriculture sector, leading to the production of safe and nutritious food, as a key NCD prevention strategy, stating:

Given the rapid change in diets and increased reliance on imported, highly-processed foods […] an important strategy for the agriculture sector is to develop sustainable agro-food based solutions to nutritional problems, creating and maintaining a diversified supply of locally-produced foods and promoting their consumption as part of a balanced diet( 39 ).

Proposed actions focused on improving the productivity and competitiveness of Pacific-based agriculture and fisheries as primary industries( 49 ), adding nutritional value to food production using post-harvest technologies and processing( 47 , 50 ) and better promotion of locally available produce( 50 , 51 ). The role of the state in supporting agricultural development was characterised primarily as technical, i.e. facilitating access to scientific and technical advice needed to improve productivity. There was also a regulatory role in relation to food safety.

Health

Every health meeting document we reviewed referenced NCD. We found a strong focus on regulating the food environment, and a clear preference for fiscal measures to increase price and reduce consumption of unhealthy food. Applying food taxes was recommended in the majority of documents (Table 2), although the 2017 ministers’ meeting noted ‘significant challenges’ with implementing these measures( 41 ). Other regulatory measures endorsed by health stakeholders included: the development of targets for recommended levels of fat, sugar and salt in local and imported products( 40 , 52 ); legislation to protect children from marketing of such foods( 41 , 42 , 52 ); and introducing national legislation on food labelling( 42 , 52 ). Community-level education and awareness building, especially for children and youth was also featured( 42 , 53 ). The 2015 and 2017 ministers’ meetings endorsed a new monitoring framework to monitor progress towards the NCD Roadmap, the Pacific Monitoring Alliance on NCD Action (MANA).

More so than any other sector, health calls for engagement with the private sector to improve the food environment, in 2009 calling on Ministries of Industry and Labour to:

work with food businesses and major exporting countries’ manufacturers to improve the quality and safety of food( 54 ).

Like other sectors, the health sector highlighted the negative impacts of trade; notably, the 2016 NCD Summit (attended primarily by health stakeholders) called for the impact of free trade agreements on population health to be monitored( 39 ).

Trade and Foreign Affairs

Of the seven trade ministers’ meetings we reviewed, only one made reference to NCD. In 2013, ministers ‘considered’ links between NCD and trade, noting ‘the importance of a balanced approach to public health’ and the need for trade and health officials to work closely( 39 ). The meeting makes explicit reference to alcohol and tobacco imports, but not unhealthy food.

Concluded in 2017, but not yet in force, PACER Plus is a comprehensive trade agreement signed by Australia, New Zealand and nine Pacific Island Countries( 55 , 56 ). While several sectors and Heads of State make a direct link between the NCD epidemic and the growth in imports of unhealthy, processed foods; the PACER Plus Agreement does not include any specific reference to NCD or nutrition-related NCD risk factors. Further, while PACER Plus specifically excludes alcohol and tobacco from scheduled commitments relating to market access, unhealthy food was not covered by this exclusion. Where the agreement does reference food, the focus was not on public health.

We did not find any mention of NCD in documentation from the three foreign ministers’ meetings.

Education

Diet, food, nutrition and NCD were largely absent from reports of education meetings. The Pacific Regional Education Framework 2018–2030( 57 ), endorsed by both ministers and heads of sector( 58 , 59 ), acknowledged child well-being as a key concern of the education sector, but does not link well-being to health. We found just one mention of NCD: in 2014, education ministers discussing the importance of sex education in schools to prevent HIV ‘unanimously agreed that NCD should be given equal priority and attention’( 39 ).

Tensions and opportunities in policy development

We identified several tensions in the policy framings of different sectors that may impact the effectiveness of efforts to address diet-related NCD. First, there may be a tension between the desire to reduce unhealthy food imports (mentioned by many sectors) and support for increased trade. Many Heads of State communiqués reference free trade as key to economic growth( 31 – 33 , 37 , 60 ) while finance ministers advocate increased Pacific exports( 44 ). Similarly, within the agriculture sector, there were calls for both trade restrictions to protect consumers from poor quality and unsafe food contributing to NCD as well as increased trade, to allow Pacific produce access to international markets( 29 ).

Second, efforts to increase economic returns from agriculture (and fisheries) may be in tension with measures to prevent NCD through improved diet. Four finance ministers’ communiqués( 34 , 61 – 63 ) described agriculture and fisheries as productive sectors that drive growth, although none cross-reference nutrition objectives. Equally, the agriculture sectors’ promotion of processing to add value to products may be inconsistent with the health sector goal of decreasing consumption of unhealthy, processed food. Third, we found that the agriculture sector prioritised food security, i.e. increasing the supply and affordability of locally-grown food through improving the productivity of the agriculture sector. By contrast, the health sector was less concerned whether food is local or imported, and more focused on improving nutrition.

As shown in Fig. 1, many internationally-recognised measures to improve nutrition and prevent diet-related NCD were under-represented in Pacific regional discussions. This suggests an opportunity to expand the scope of response efforts, through increased support to:

Promote production of healthy local food

Stimulate the import of healthy and nutritious foods, and reduce import of unhealthy foods

Encourage retail of healthy foods (e.g. subsidies)

Reformulate locally-produced food to reduce salt and sugar content

Introduce catering policies/guidelines for schools, workplaces, hospitals

Restrict marketing of unhealthy foods, e.g. to children

Improve food labelling

In addition, many sectors referenced ‘education’ as an important approach to prevent NCD (Table 2), suggesting a clear opportunity for increased focus on health/nutrition education in schools, as recommended in the NCD Roadmap and the WHO( 39 ).

Discussion

The regional response to diet-related NCD in the Pacific has been characterised by high-level political support. Our review found that many sectors recognise their role in addressing the epidemic, and that there is cross-sectoral support for key measures, such as taxation on unhealthy food and drink. However, we also identified tensions between sectoral framings of NCD issues, which may be a barrier to progressing other priority strategies set out in the WHO NCD Action plan( 8 ). In particular there are conflicts between the priorities of trade, health and agriculture sectors, and a lack of priority demonstrated by them and the education sector in considering their role in a comprehensive NCD response.

In line with previous studies( 27 ) our policy space analysis demonstrated that international priorities and evidence may have been influential in driving local (or in our case regional) policy and practice( 64 ). Echoing studies on nutrition policy from other low-income countries, our study also highlighted the difficulty of maintaining momentum for specific policy goals over time; the complexity of operationalising multi-sectoral action (even when there is strong recognition it is needed); and the long-standing challenge of moving from rhetorical commitment to implementation( 64 – 66 ). We identified opportunities to broaden the scope of efforts to prevent diet-related NCD( 67 – 69 ).

International agendas and Pacific priorities

The Pacific focus on NCD is likely to have both influenced, and been influenced by, the growing global focus on this issue. Pacific countries are likely to be have engaged in the preparatory discussions for the UN General Assembly’s first High Level Meeting on NCD in September 2011. The Pacific Leaders’ communiqué on NCD was issued a few months earlier, in July, and was subsequently referenced in the second UN HLM, in 2014( 70 ). Major publications on NCD by the WHO and World Economic Forum in 2011, though not explicitly mentioned in regional communiqués, are likely to have reinforced Pacific concerns on the health and economic impact of the epidemic. Equally, the diminishing focus on diet-related NCD that we found towards the middle of the decade may reflect a broadening of the NCD agenda at global level, away from a strong focus on tobacco and nutrition to include mental illness and road accidents, which led to a decreased emphasis on unhealthy diets( 69 ). At the same time, the international health agenda was being reframed in response to the Sustainable Development Goals( 71 ), the West African Ebola outbreak in 2014–2015, and the emergence of Universal Health Coverage as a leading priority( 72 ), potentially decreasing global attention on NCD. In the Pacific, an influential 20-year review of Pacific health( 73 ) released in 2015, found slow progress in many areas and may also have prompted a broadening of the health debate in the region.

The recent refocusing on diet-related NCD through reference to childhood obesity in the 2018 heads of state communiqué( 43 ) is likely a response to the 2016 report of the WHO Ending Childhood Obesity (ECHO) Commission( 74 ) and the establishment of a Pacific ECHO network in 2017( 41 ).

Beliefs, values and policy positions

Our review highlighted that while all sectors acknowledge the seriousness of the NCD epidemic in the Pacific, only health and agriculture prioritise NCD-prevention activities. As Sabatier notes, coherent, cross-sectoral policy responses are more likely when relevant actors have shared values and underlying core beliefs( 26 ). We found tensions between sectoral framings of diet-related NCD (i.e. views on the policy ‘problem’ and the best response) suggesting differences in underlying values and beliefs, which may in turn explain the varying levels of priority afforded to NCD across sectors and differences in policy responses.

For example, the health sector views ‘food systems’ and the food environment as driving overweight and obesity, and believes the state has a role in regulating many aspects of these systems. Although agriculture has a complementary framing, focused on the links between food security and nutrition, this sector favoured a productionist approach, prioritising increased output of healthy (often local) foods as a ‘solution’ to diet-related NCD. This food-centric approach, of prioritising agricultural production over nutrition has been identified in many low and middle-income countries( 15 , 75 , 76 ).

Finance ministers’ communiqués adopted a different framing again, reflective of neo-liberal values: they expressed concern for escalating healthcare expenditure, and, in a different context, referenced increased production of and markets for agricultural and fisheries sectors as key drivers of economic growth. This is unsurprising given many Pacific countries depend on export earnings from agriculture and fisheries( 76 ). Evidence from global studies suggests that neoliberal values related to the food industry as a source of jobs and revenue may be in tension with a value frame that seeks to re-orientate food supply systems towards production of healthy foods( 75 ).

These differences in framing reflect the varying mandate of different sectors; however, explicitly identifying them and understanding the values on which they are based is key to achieving policy coherence. Evaluating policy coherence across government departments has been prioritised in the Sustainable Development Goals( 77 ) and has been identified as critical to nutrition policy( 75 ).

Role of regional institutions and priorities to strengthen the Pacific response

Pacific regional institutions have played a key role in raising the profile of the NCD epidemic across the full range of relevant sectors, and eliciting commitments to action. Their challenge now is to build shared values – i.e. a common understanding of the drivers of the epidemic, and solutions to it – to encourage a more coherent and comprehensive policy response engaging all sectors.

National studies suggest coherent policy approaches are more likely when a lead agency is identified, this agency has strong links to senior levels of government, and where there is a single plan or agreed set of goals across sectors( 75 ). Our study found all these elements to be present at regional level in the Pacific, suggesting a firm foundation for agencies to build on. For example, SPC and WHO have partnered with PIF to put NCD onto the agenda of Heads of State and senior ministers. Equally, as both SPC and PIF are multi-sectoral agencies they are able to identify opportunities for cross-sectoral cooperation; for example SPC co-convenes joint meetings with FAO on agriculture and the WHO on health. In addition, the NCD Roadmap( 3 ) provides a common plan and set of targets that different sectors have endorsed, and assigns roles and responsibilities.

This suggests regional agencies are well placed to further support the Pacific’s NCD response, including catalysing action from sectors that have been less engaged to date. Evidently, there is a wide range of possible actions and entry points open to regional agencies; we make recommendations in three priorities areas we believe will help drive policy coherence and encourage a more comprehensive response; and, which would particularly benefit from regional (as oppose to national) support.

Trade

Trade policy provides a clear example of where higher-level coordination may encourage policy coherence, and help to overcome tensions in framings between finance, agriculture and health sectors. In a broader policy environment that seeks to expand free trade, strengthening public health safeguards in trade agreements is critical( 78 ). Support from regional agencies to clarify what nutrition-related regulatory interventions are compatible with trade agreements is therefore likely to be useful, given the widespread recognition of trade as a driver of NCD but also Pacific reliance on exports for economic development. Such work is highly technical, and many smaller Pacific countries may not have the requisite knowledge and capacities on-island( 79 ).

Education

The education sector does not appear to identify with its designated role in promoting healthy diets and food environments in schools, and has not prioritised NCD discussion in regional fora. Regional agencies, such as SPC, with links into both the health and education sector could facilitate a more coherent response.

Monitoring

Improved monitoring has a role to play in demonstrating the impact of policies and building momentum for sustained action. The Monitoring Alliance for NCD Action provides an agreed list of indicators to monitor NCD policy actions, including on diet-related NCD( 79 ), and has received regional endorsement. This will facilitate collection and dissemination of comparable data, allowing regional level analysis of progress and gaps.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of our analysis was its broad scope, covering six sectors and Heads of State, and extensive documentary analysis. Using a systematic approach to data extraction and structuring our analysis around an agreed international framework on NCD prevention also contributed to the robustness and relevance of findings. The main limitation was that we only reviewed regional documents. While these provide an indication of the prominence of NCD issues within each sector, they do not capture action at country level, which will vary and may be more progressive in some contexts. Further, although we were able to access a large number of documents through direct contact with regional agencies, we may have missed some relevant reports.

Conclusion

We found strong rhetorical commitment to addressing diet-related NCD in the Pacific, but varying commitment to specific nutrition policy actions outside the health sector. We also identified tensions between sectoral framings and underlying values that will need to be addressed if the Pacific is to progress from commitment to sustained implementation of targeted nutrition interventions. Our study suggests regional fora could play an important role here, coordinating and strengthening nutrition policy and practice, and identifying and resolving differences. Documentary and policy space analysis can be useful in this endeavour, through identifying opportunities for additional measures and providing insight on the positions and framings that underpin sectoral policy and practice. In the Pacific, further analysis, going beyond desk review, is needed to more fully describe relevant policy sub-systems, i.e. the full range of actors (including commercial and non-state actors) that share a common framing of an issue, the resources they deploy, their relative power, the extent to which recommended polices are implemented, and how these contribute to within-sector tensions in the focus and types of policies proposed.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: We acknowledge the Pacific Island Forum Secretariat and the Food and Agriculture Organization for providing documents not available online. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: J.W. is Director of the WHO Collaborating Centre on Salt Reduction. P.V. and S.T.W.T. are staff of The Pacific Community, which convenes the Pacific Heads of Health Meeting, co-convenes the Pacific Health Ministers’ Meeting, and manages the Monitoring Alliance on NCD Action (MANA) database. Authorship: R.D. and A.M.T. conceived the paper and formulated the research question. R.D., E.R., E.S. and A.G. reviewed meeting reports, and extracted relevant data. R.D. wrote the paper; all other authors reviewed and amended text. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019002118.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). (2016) GBD Compare Data Visualization. Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington; [cited 2018 October 22]. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Foreman KJ, Marquez N, Dolgert A et al. (2018) Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and alternative scenarios for 2016–40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet 392, 2052–2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Bank. (2014) Non-Communicable Disease (NCD) Roadmap Report (English). Washington, DC: World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- 4. United Nations. (2018) Sustainable Development Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg3.

- 5. UN. (2014) Decade of Action on Nutrition 2016–2025. Rome, Italy: UN Standing Committee on Nutrition, Food and Agricultural Organization. [Cited 2019 15 February]. https://www.unscn.org/en/topics/un-decade-of-action-on-nutrition. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thow AM, Quested C, Juventin L et al. (2011) Taxing soft drinks in the Pacific: implementation lessons for improving health. Health Promot Int 26, 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Cancer Research Fund International. (2018) Building momentum: lessons on implementing a robust sugar sweetened beverage tax.

- 8. World Health Organization. (2013) Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020, Annex 3. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization. (2013) Follow-up to the Political Declaration of the High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases. SIXTY-SIXTH WORLD HEALTH ASSEMBLY WHA66.10 Agenda Item 13.1, 13.2, 27 May 2013. Annex: Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases 2013–2020. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thow AM, Heywood P, Schultz J et al. (2011) Trade and the nutrition transition: strengthening policy for health in the Pacific. Ecol Food Nutr 50, 18–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thow A & Snowdon W (2010) The effect of trade and trade policy on diet and health in the Pacific Islands. In Trade, Food, Diet and Health: Perspectives and Policy Options pp. 147–168 [Hawkes C, Blouin C, Henson S, Drager N, Dubé L, editors]. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reich MR & Balarajan Y (2012) Political Economy Analysis for Food and Nutrition Security. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thow AM, Snowdon W, Schultz JT et al. (2011) The role of policy in improving diets: experiences from the Pacific Obesity Prevention in Communities food policy project. Obes Rev 12, 68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roberto CA, Swinburn B, Hawkes C et al. (2015) Patchy progress on obesity prevention: emerging examples, entrenched barriers, and new thinking. Lancet (London, England) 385, 2400–2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thow AM, Greenberg S, Hara M et al. (2018) Improving policy coherence for food security and nutrition in South Africa: a qualitative policy analysis. Food Secur 10, 1105–1130. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mozaffarian D, Angell SY, Lang T et al. (2018) Role of government policy in nutrition—barriers to and opportunities for healthier eating. BMJ 361, k2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. The Framework for Pacific Regionalism Suva. (2014) Fiji: Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat. [Cited 2018 22 October]. https://www.forumsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Framework-for-Pacific-Regionalism_booklet.pdf.

- 18. Latu C, Moodie M, Coriakula J et al. (2018) Barriers and facilitators to food policy development in Fiji. Food Nutr Bull 39, 621–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thow AM, Swinburn B, Colagiuri S et al. (2010) Trade and food policy: case studies from three Pacific Island countries. Food Policy 35, 556–564. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Waqa G, Bell C, Snowdon W et al. (2017) Factors affecting evidence-use in food policy-making processes in health and agriculture in Fiji. BMC Public Health 17, 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cullerton K, Donnet T, Lee A et al. (2016) Using political science to progress public health nutrition: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr 19, 2070–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thow AM, Kadiyala S, Khandelwal S et al. (2016) Toward food policy for the dual burden of malnutrition: an exploratory policy space analysis in India. Food Nutr Bull 37, 261–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. OECD. (2016) Better Policies for Sustainable Development 2016: A New Framework for Policy Coherence. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moustafa A & Abbott D. (2014) The State of Human Development in the Pacific: A Report on Vulnerability and Exclusion in a Time of Rapid Change. Suva, Fiji: UNESCAP. [Google Scholar]

- 25. World Bank. (2018) The World Bank in the Pacific Islands [cited 2018 22 October]. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/pacificislands/overview.

- 26. Sabatier PA (1998) The advocacy coalition framework: revisions and relevance for Europe. J Eur Public Policy 5, 98–130. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Crichton J (2008) Changing fortunes: analysis of fluctuating policy space for family planning in Kenya. Health Policy Plan 23, 339–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grindle MS & Thomas JWJPS (1989) Policy makers, policy choices, and policy outcomes: the political economy of reform in developing countries. 22, 213–248. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Food and Agriculture Organization. (2011) Towards a Food Secure Pacific. Rome: FAO. [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Health Organization. (2011) Ninth Meeting of Ministers of Health for the Pacific Island Countries - Outcome Document. Honiara, Solomon Islands 28 June 2011.

- 31. GPacific Islands Forum. (2011) Forty-Second Pacific Islands Forum. Auckland, New Zealand 7 September 2011. Report No.

- 32. Pacific Islands Forum. (2012) Forty-Third Pacific Islands Forum. Rarotonga, Cook Islands: 28 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pacific Islands Forum. (2013) Forty-Fourth Pacific Islands Forum. Majuro, Republic of the Marshall Islands 3 September 2013.

- 34. Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat. (2013) Forum Economic Ministers Meeting Action Plan. Nuku’alofa, Tonga 3 July 2013.

- 35. Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat. (2014) Joint Forum Economic and Pacific Health Ministers Meeting. Honiara, Solomon Islands 11 July 2014.

- 36. The Pacific Community. (2016) Pacific NCD Summit: Translating Global and Regional Commitments into Local Action, 20–22 June 2016. SPC: Noumea. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pacific Islands Forum. (2014) Forty-fifth Pacific Islands Forum: Palau Declaration on ‘The Ocean: Life and Future’. Koror, Republic of Palau. 29–31 July 2014.

- 38. Pacific Islands Forum. (2016) Forty-Seventh Pacific Islands Forum. Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia 8 September 2016.

- 39. Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat. (2013) Forum Trade Ministers Meeting: Outcome Document. Apia, Samoa: PIF. 19 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40. World Health Organization. (2013) Apia Outcome: Tenth Pacific Health Ministers Meeting. Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific. 2 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41. World Health Organization. (2017) Outcomes of the Twelfth Pacific Health Ministers’ Meeting, Rarotonga, Cook Islands. WHO. 28–30 August 2017.

- 42. World Health Organization. (2015) Eleventh Meeting of Ministers of Health for the Pacific Island Countries - Yanuca Declaration.

- 43. Pacific Islands Forum. Forty-Ninth Pacific Islands Forum. Yaren, Nauru. 3 September 2018.

- 44. Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat. (2014) Forum Economic Ministers Meeting. Honiara, Solomon Islands. 8–11 July 2014.

- 45. Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat. 2015. Forum economic ministers meeting: FEMM action plan. Rarotonga, Cook Islands. 29 October 2015.

- 46. Food and Agriculture Organization. (2013) Tenth Meeting of the FAO Southwest Pacific Ministers for Agriculture. Apia, Samoa. 11 April 2013.

- 47. Food and Agriculture Organization. (2015) Eleventh meeting of the FAO Southwest Pacific Ministers for Agriculture. Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea. 11 May 2015.

- 48. Food and Agriculture Organization. (2017) First Joint FAO and SPC Pacific Ministers of Agriculture and Forestry Meeting. Port Vila, Vanuatu. 20 October 2017.

- 49. Food and Agriculture Organization. (2009) Eighth Meeting of the FAO Southwest Pacific Ministers for Agriculture - Full Report. Alofi, Niue. 20 May 2009.

- 50. Food and Agriculture Organization. (2011) Ninth Meeting of the FAO Southwest Pacific Ministers for Agriculture - Outcome Document. Vava’u Tonga: 5 April 2011.

- 51. Food and Agriculture Organization. (2009) Eighth Meeting of the FAO Southwest Pacific Ministers for Agriculture - Outcome Document. Alofi, Niue. 20 May 2009.

- 52. The Pacific Community. (2014) Second Heads of Health Meeting. Nadi, Fiji. 29 April 2014.

- 53. World Health Organization. (2009) Eighth Meeting of Ministers of Health for the Pacific Island Countries - Outcome Document.

- 54. World Health Organization. (2009) Eighth Meeting of Ministers of Health for the Pacific Island Countries - Full Report. Madang, Papua Guinea. 7 July 2009.

- 55. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia). Free Trade Agreements Not Yet in Force. https://dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/not-yet-in-force/Pages/not-yet-in-force.aspx.

- 56. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia). Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic Relations (PACER) Plus. https://dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/not-yet-in-force/pacer/Pages/pacific-agreement-on-closer-economic-relations-pacer-plus.aspx.

- 57. Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat. (2018) Pacific Regional Education Framework (PacREF): Moving Towards Education 2030. Suva, Fiji: 2018. https://www.forumsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Pacific-Regional-Education-Framework-PacREF-2018-2030.pdf (accessed August 2018).

- 58. Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat. (2018) 11th Forum Education Ministers’ Meeting - Outcome Document. Republic of Nauru. 24 May 2018.

- 59. UNESCO. (2017) The 22nd Consultation Meeting of the Pacific Heads of Education Systems. Nadi, Fiji. 11 October 2017.

- 60. Pacific Islands Forum. (2017) Forty-Eighth Pacific Islands Forum. Apia, Samoa. 5 September 2017.

- 61. Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat. (2009) Forum Economic Ministers’ Meeting Action Plan. Rarotonga, Cook Islands. 27–28 October.

- 62. Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat. (2014) Forum Education Ministers’ Meeting - Outcome Document. Rarotonga, Cook Islands: 31 March 2014.

- 63. Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat. (2010) Forum Economic Ministers Meeting: Forum Economic Action Plan. Alofi, Niue. 27–28 October, 2010.

- 64. Shiffman J (2007) Generating political priority for maternal mortality reduction in 5 developing countries. Am J Public Health 97, 796–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Harris J, Drimie S, Roopnaraine T et al. (2017) From coherence towards commitment: changes and challenges in Zambia’s nutrition policy environment. Global Food Secur 13, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Candel JJL & Pereira L (2017) Towards integrated food policy: main challenges and steps ahead. Environ Sci Policy 73, 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- 67. World Economic Forum. (2011) From Burden to “Best Buys”: Reducing the Economic Impact of NCDs in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Geneva: WEF, WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 68. World Health Organization. (2011) Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2010: Description of the Global Burden of NCDs, Their Risk Factors and Determinants. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Buse K & Hawkes S (2014) Health post-2015: evidence and power. Lancet (London, England) 383, 678–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. UN. General Assembly. (2014) Outcome Document of the High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Comprehensive Review and Assessment of the Progress Achieved in the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases, A/RES/68/300. 17 July 2014. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hill PS, Buse K, Brolan CE et al. (2014) How can health remain central post-2015 in a sustainable development paradigm? Globalization Health 10, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ghebreyesus TA (2017) All roads lead to universal health coverage. Lancet Global Health 5, e839–e840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Matheson D (2015) Healthy Islands Review: The First 20 Years of the Journey Towards the Vision of Healthy Islands in the Pacific. WHO. (Consultant Report).

- 74. World Health Organization. (2016) Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Baker P, Hawkes C, Wingrove K et al. (2018) What drives political commitment for nutrition? A review and framework synthesis to inform the United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition. BMJ Global Health 3, e000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Cassels S (2006) Overweight in the Pacific: links between foreign dependence, global food trade, and obesity in the Federated States of Micronesia. Global Health 2, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. UNCTAD. Goal 17: Partnerships for the Goals Geneva. https://stats.unctad.org/Dgff2016/partnership/goal17/target_17_14.html (accessed August 2019).

- 78. Thow AM & McGrady B (2014) Protecting policy space for public health nutrition in an era of international investment agreements. Bull World Health Org 92, 139–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Tolley H, Snowdon W, Wate J et al. (2016) Monitoring and accountability for the Pacific response to the non-communicable diseases crisis BMC Public Health 16, 958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019002118.

click here to view supplementary material