Abstract

Background:

Higher rates of dementia are reported in people with history of coronary artery disease. Smaller hippocampal volume (HV) is a risk factor for the development of dementia.

Objective:

This study assessed whether coronary artery calcification (CAC) and carotid intima media thickness (CIMT) are associated with HV in participants from the Dallas Heart Study (DHS), a community-based study of Dallas County, Texas residents.

Method:

Data from a total of n = 1821 participants in the DHS with brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), CAC, and CIMT data were included in the present study, after excluding those with a history of myocardial infarction or stroke. To evaluate the effect of CAC and CIMT on total HV, four linear regression analyses were conducted in which the primary predictor was: (1) CAC as a continuous metric; (2) CAC as a binary metric (CAC = 0 vs. CAC ≥ 1); CAC as a continuous metric, but only for those with CAC > 0; and (4) CIMT as a continuous metric. Demographic and cardiovascular disease risk factors, as well as intracranial volume, were entered into the model as covariates.

Results:

Participants were largely women (58.2%) with a mean age of 49.7 ± 10.3 years. Forty-six percent of the sample reported being Black and approximately 14% reported being Hispanic. All three variations of the CAC effect were non-significant predictors of total HV (β = −0.013, p = .602; β = −0.011, p = .650; β = 0.036, p = .354, respectively), as was the effect of CIMT (β = 0.009, p = .686).

Conclusions:

Current findings suggest non-significant relationships between both CAC and CIMT, and total HV, while controlling for other related factors in a large, diverse, community-based sample of people without history of myocardial infarction or stroke. In the context of existing evidence that both coronary artery disease and smaller HV are associated with the development of dementia, the present findings suggest that neither marker of cardiovascular disease examined here, is associated with a reduction in HV in the population studied. Longitudinal studies are needed to assess relationships between CAC and CIMT and HV over time.

Keywords: coronary artery calcification, carotid intima media thickness, hippocampus, coronary artery disease, magnetic resonance imaging, dementia

INTRODUCTION

Research on cardiovascular disease and dementia suggests higher rates of dementia in people with atherosclerosis, angina, and history of myocardial infarction (1). Additionally, prior studies demonstrate that more significant coronary artery calcification (CAC) is nearly pathognomonic for coronary artery atherosclerosis, with higher scores reflecting higher atherosclerotic burden and higher risk of adverse cardiovascular events (2). However, the relationship between atherosclerosis and dementia remains unclear. One cross-sectional study demonstrated an increased risk for dementia in persons with greater amounts of CAC (3). This relationship was attenuated when adjusting for brain volume, suggesting that structural brain differences may influence the effects of CAC on dementia risk; that is, CAC burden may influence brain volumes (3). One study examined hippocampal volume (HV) in 20 cognitively normal male patients (mean age of 60 years) with coronary artery disease (CAD), defined as “significant stenosis of one or more major coronary arteries,” that was confirmed using coronary angiography and 20 healthy control comparisons (4). They observed that HV was approximately 14% smaller in individuals with CAD compared to controls without CAD.

A hypothesized mechanism of the relationship between dementia and CAD is cerebral hypoperfusion (5). Importantly, carotid intima media thickness (CIMT) exacerbates cerebral hypoperfusion (6). CIMT is the measure of the thickness of the two innermost layers of the carotid artery – the intima and media – and is a widely used surrogate marker of carotid atherosclerosis (7). Furthermore, CIMT predicts coronary artery disease risk, and may play a role in the relationship between cardiovascular disease and dementia (8). However, the literature is mixed regarding the relationship between CIMT and HV. Romero et al. did not find a relationship between CIMT and HV in n = 1975 participants aged 63 years on average, in the Framingham Offspring Cohort (9). In contrast, Baradarah et al. observed that CIMT changes over time predicted smaller HV in individuals from the Framingham Offspring Cohort (10).

Prior research has shown HV to be predictive of later cognitive decline, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease (11–15), thus warranting further examination of risk factors for decreasing HV. Given this need, and the relatively incongruous findings from prior research, the present study sought to examine the effect of both CAC and CIMT on HV in a large multiracial and multiethnic population using data from the Dallas Heart Study (DHS), a community-based study designed to identify demographic and biological factors associated with cardiovascular health in individuals in Dallas County, Texas (16). It was hypothesized that both higher CAC and CIMT values would be predictive of lower HV.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

Dallas Heart Study

The Dallas Heart Study (DHS) is a multiethnic population-based sample of individuals residing in Dallas County, Texas designed to identify environmental and biological factors associated with cardiovascular disease. The study oversampled for Black individuals with the goal of studying cardiovascular risk factors in this population (16). The sampling was conducted across two sequential phases; data collection for the first phase of the study (DHS-1) began on July 1, 2001 and occurred during three separate visits with the participant. During the first visit (in-home), a structured interview was conducted during which the participant provided information regarding their demographic characteristics, medical history, and lifestyle habits. The participant’s height, weight, and blood pressure were also collected. During visit 2 of the first phase, also conducted in the participant’s home, blood and urine samples were collected. Finally, visit 3 of the first phase consisted of several imaging studies, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and electron beam computed tomography (16). The second phase of the study (DHS-2) began on September 1, 2007. During this phase, data were collected in one visit, and included a repeat assessment of medical history, lifestyle habits, height, and weight. Participants were also asked to participate in imaging studies including cardiac multi-detector computerized tomography for coronary artery calcification measurements, carotid MRI for wall thickness measurements, and brain MRI for hippocampal and other brain volume measurements (16).

Sample Selection

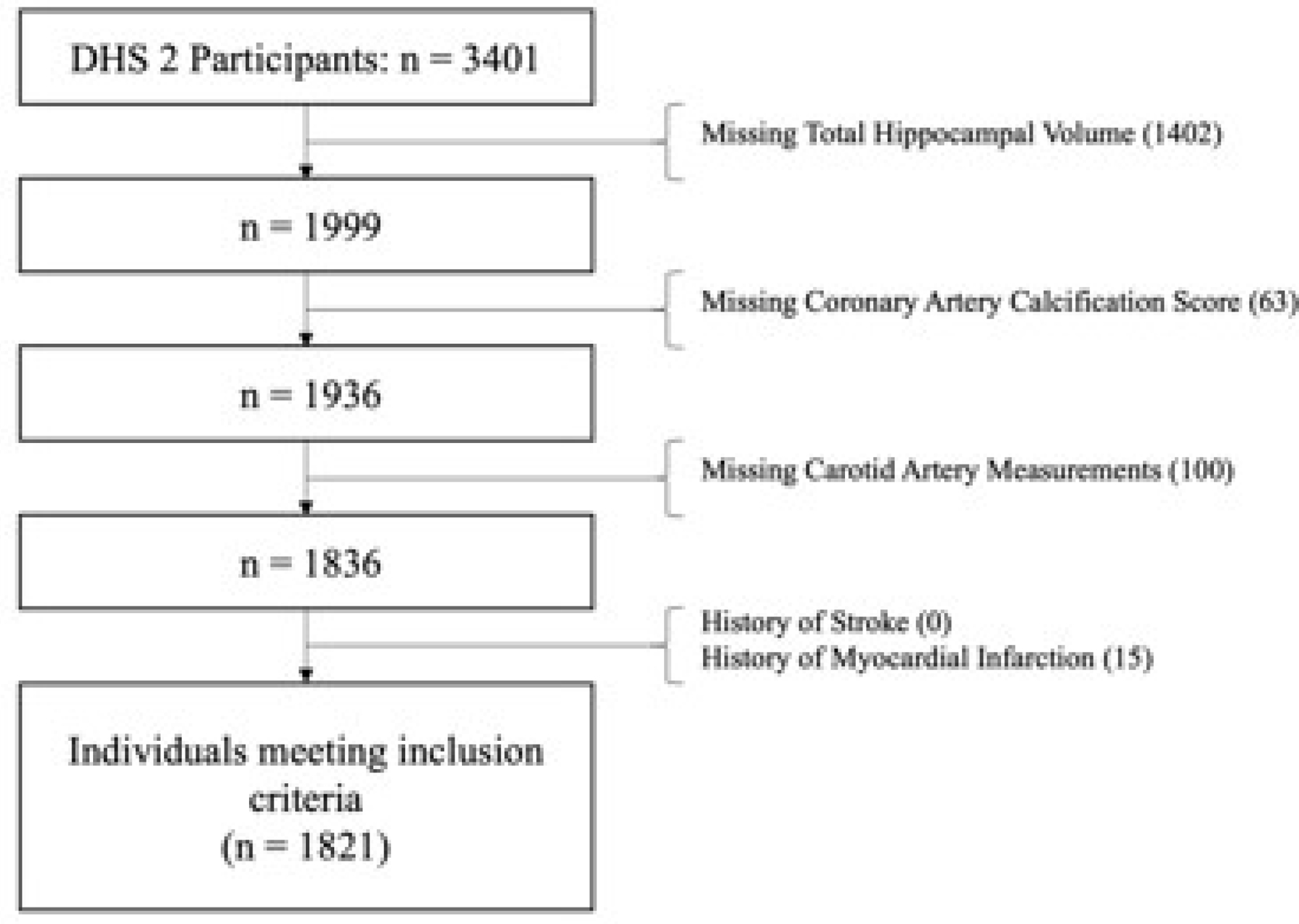

Participants from the DHS-2 cohort who had undergone multi-detector computer tomography (MDCT) of the coronary arteries and structural neuroimaging using MRI were included in the present study (n = 1836). Participants with a history myocardial infarction or stroke were excluded from analyses, resulting in a final analytical sample of n = 1821. Selection criteria are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Sample selection criteria and flow.

Measures

As part of DHS-2, coronary artery calcification (CAC) was measured twice for each subject with MDCT using methods previously described (17). Scores are represented in Agatston units, the standard system of quantification for severity of CAC on coronary CT [12]. CIMT was also assessed. To measure intima-media thickness of internal and common carotid arteries (CIMT) as well as HV, brain MRI was quantified. FreeSurfer automated image analysis suite Version 4.4 software was used to calculate grey matter volume and white matter volume. Left and right hippocampal volumes were measured separately for each participant and were summed to determine total hippocampal volume. Additional information about the imaging methodology can be found elsewhere (18–22). Finally, available demographic and clinical information from DHS-2 were entered into the analyses as covariates including age (years), sex, ethnicity, education (years), BMI (kg/m2), body surface area (m2), systolic blood pressure (mmHg), total cholesterol (mg/dL), HDL cholesterol (mg/dL), and intracranial volume (mm3).

Statistical Analyses

Prior to conducting primary analyses, data were checked for assumptions of normality and linearity. Deviations from normality were found in both CAC and CIMT and as such, were natural log transformed into ln(CAC+1) and ln(CIMT+1), respectively. A constant of one was added to each value of CAC and CIMT to avoid null data in individuals for whom CAC = 0 and/or CIMT = 0. Additionally, CAC scores were computed as the average of both the participants’ left and right CAC scores, and the value for CIMT was obtained by averaging the internal and common carotid artery intima-media thicknesses for each subject.

To evaluate the predictive ability of CAC on total HV, three multiple regression analyses were conducted, differing only in the nature of the CAC predictor variable. In model 1, CAC was represented as ln(CAC+1); in model 2, CAC scores were dichotomized into CAC = 0 (coded as 0) and CAC > 0 (coded as 1); and in model 3, CAC was again represented as ln(CAC+1), the analysis of which included only those participants with CAC > 0. A fourth linear regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the predictive ability of CIMT on total HV (model 4). All four regression models included the following covariates: age (years), sex, ethnicity, education (years), BMI (kg/m2), body surface area (m2), systolic blood pressure (mmHg), total cholesterol (mg/dL), HDL cholesterol (mg/dL), and intracranial volume (mm3). Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). The family-wise error was set a priori as α ≤ .05, with results deemed statistically significant at a Bonferroni-corrected p ≤ .0125.

RESULTS

Participants included in the present study (n = 1821) were 58.2% female, with a mean age of 49 ± 10 years Forty-six percent of the individuals identified as Black and 13.9% identified as Hispanic. The average CAC score was 81.53 ± 334.62 with 59% of the participants having CAC = 0, and 41% having CAC ≥ 1. The average CIMT score was 27.81 ± 6.58 and the average total HV was 6.77 ± 0.851 mL. Complete demographic and clinical characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1062 | 58.2 |

| Male | 759 | 41.8 |

|

| ||

| Race and Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 253 | 13.9 |

| non-Hispanic Black | 838 | 46.0 |

| non-Hispanic White | 686 | 37.7 |

| Other/unknown | 44 | 2.4 |

|

| ||

| CAC (dichotomized) | ||

| CAC = 0 | 1076 | 59.1 |

| CAC > 0 | 745 | 40.9 |

|

| ||

| Mean | SD | |

|

| ||

| Age | 49.73 | 10.29 |

| Education (years) | 12.84 | 2.15 |

| BMI | 29.26 | 5.56 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.95 | 0.21 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 130.39 | 18.27 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 195.44 | 39.67 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 53.59 | 15.26 |

| Total hippocampal volume (mL) | 6.77 | 0.85 |

| Intracranial volume (mm3) | 1127.81 | 242.47 |

| CAC | 81.53 | 334.62 |

| ln(CAC) | 1.41 | 2.15 |

| CIMT | 27.81 | 6.58 |

| ln(CIMT) | 3.34 | 0.21 |

Note. Analytic n = 1821.

To evaluate the predictive ability of CAC on total HV, three regression analyses were conducted in which the effect of CAC was represented as: (1) ln(CAC+1), (2) dichotomized CAC with CAC = 0 vs. CAC ≥ 1, and (3) ln(CAC+1) using an analytic sample of only those individuals with CAC > 0). All three derivatives of CAC were found to be non-significant predictors of total HV (β = −0.013, p = .602; β = - 0.011, p = .650; β = 0.036, p = .354, respectively). However, age, sex, body surface area, and intracranial volume were found to significantly predict total HV in all three CAC models, excepting surface area in model 3. Results from the CAC regression models are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Linear Regression Results for Models with CAC as Primary Predictor of Hippocampal Volume

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Model 1 | β | p | Lower | Upper |

| ln(CAC + 1) | −0.013 | .602 | −.024 | .014 |

| Age | −0.093 | < .001 | −.012 | −.004 |

| Sex | 0.095 | .006 | .047 | .277 |

| Ethnicity – Non-Hispanic White | 0.273 | < .001 | .392 | .557 |

| Ethnicity – Hispanic | 0.170 | < .001 | .290 | .528 |

| Education (years) | 0.027 | .262 | −.008 | .029 |

| BMI | −0.042 | .260 | −.017 | .005 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 0.142 | < .001 | .255 | .869 |

| Systolic blood pressure | −0.001 | .953 | −.002 | .002 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.017 | .437 | −.001 | .001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | −0.008 | .355 | −.003 | .002 |

| Smoking status - current | −0.033 | .213 | −.178 | .040 |

| Smoking status - past | 0.011 | .666 | −.068 | .107 |

| History of diabetes | 0.029 | .195 | −.038 | .188 |

| Intracranial volume (mm3) | 0.246 | < .001 | .000 | .000 |

|

| ||||

| Model 2 | β | p | Lower | Upper |

|

| ||||

| CAC dichotomous | −0.011 | .650 | −.099 | .062 |

| Age | −0.094 | < .001 | −.012 | −.004 |

| Sex | 0.093 | .006 | .046 | .274 |

| Ethnicity – Non-Hispanic White | 0.274 | < .001 | .392 | .557 |

| Ethnicity – Hispanic | 0.170 | < .001 | .290 | .528 |

| Education (years) | 0.027 | .264 | −.008 | .028 |

| BMI | −0.041 | .269 | −.017 | .005 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 0.142 | < .001 | .258 | .871 |

| Systolic blood pressure | −0.002 | .946 | −.002 | .002 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.017 | .429 | −.001 | .001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | −0.009 | .711 | −.003 | .002 |

| Smoking status - current | −0.033 | .219 | −.177 | .041 |

| Smoking status - past | 0.012 | .642 | −.067 | .108 |

| History of diabetes | 0.029 | .188 | −.037 | .189 |

| Intracranial volume (mm3) | 0.246 | < .001 | .000 | .000 |

|

| ||||

| Model 3 | β | p | Lower | Upper |

|

| ||||

| ln(CAC + 1) | 0.036 | .354 | −.017 | .046 |

| Age | −0.183 | < .001 | −.023 | −.009 |

| Sex | 0.115 | .033 | .016 | .375 |

| Ethnicity – Non-Hispanic White | 0.254 | < .001 | .307 | .567 |

| Ethnicity – Hispanic | 0.154 | < .001 | .208 | .630 |

| Education (years) | 0.038 | .327 | −.014 | .043 |

| BMI | −0.043 | .461 | −.024 | .011 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 0.105 | .085 | −.060 | .931 |

| Systolic blood pressure | −0.007 | .848 | −.004 | .003 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.035 | .313 | −.001 | .002 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.043 | .257 | −.002 | .007 |

| Smoking status - current | −0.072 | .091 | −.314 | .023 |

| Smoking status - past | 0.032 | .437 | −.083 | .192 |

| History of diabetes | 0.043 | .228 | −.059 | .248 |

| Intracranial volume (mm3) | 0.212 | < .001 | .000 | .000 |

Note. Reference categories are female (sex), non-Hispanic Black (ethnicity), and non-smoker (smoking status), and CAC = 0 (dichotomous CAC). Model 3 includes only those with CAC > 0. Omnibus results for Model 1: F(13,1817) = 40.670, p < .001, R2 = 0.262, analytic n = 1821; Model 2: F(13,1817) = 40.664, p < .001, R2 = 0.262, analytic n = 1821; Model 3: F(13,731) = 15.857, p < .001 R2 = 0.257, analytic n = 745.

Likewise, to evaluate the effect of CIMT on total HV, a fourth regression analysis was conducted (model 4). Similarly to that found for the CAC models, ln(CIMT) was also found to be a non-significant predictor of total hippocampal volume (β = 0.009, p = .686), while the effects of age, sex, ethnicity, body surface area, and intracranial volume were significant. Results from the CIMT regression model are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Linear Regression Results for Model with CIMT as Primary Predictor of Hippocampal Volume

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Model 4 | β | p | Lower | Upper |

| ln(CIMT + 1) | 0.009 | .686 | -.236 | .358 |

| Age | −0.099 | < .001 | −.012 | −.004 |

| Sex | 0.100 | .003 | .057 | .287 |

| Ethnicity – Non-Hispanic White | 0.266 | < .001 | .377 | .544 |

| Ethnicity – Hispanic | 0.160 | < .001 | .263 | .504 |

| Education (years) | 0.031 | .203 | −.006 | .030 |

| BMI | −0.042 | .261 | −.018 | .005 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 0.140 | < .001 | .247 | .864 |

| Systolic blood pressure | −0.008 | .721 | −.002 | .002 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.015 | .483 | −.001 | .001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | −0.003 | .904 | −.003 | .002 |

| Smoking status - current | −0.036 | .180 | −.184 | .035 |

| Smoking status - past | 0.019 | .467 | −.055 | .121 |

| History of diabetes | 0.033 | .135 | −.027 | .201 |

| Intracranial volume (mm3) | 0.245 | < .001 | .000 | .000 |

Note. Reference categories are female (sex), non-Hispanic Black (ethnicity), and non-smoker (smoking status). Omnibus results for Model 4: F(13,1817) = 40.210, p < .001, R2 = 0.264, analytic n = 1821.

Because the sample had a mean age of only 49 years, we conducted post hoc linear regression analyses of participants (n = 158) aged 65 years or older. Analyses were specified to include the same variables as in the primary analyses, and indicated that In(CAC+1), CAC dichotomous, In(CAC+1) in those with CAC > 0, and In(CIMT + 1) were non-significant predictors of HV.

DISCUSSION

This report examined the effect of CAC and CIMT on total HV, the former of which was examined in three ways: (1) as a continuous CAC metric in the analytic sample, (2) as a dichotomized CAC score variable assessing the presence or absence of CAC (i.e., CAC = 0 vs. CAC ≥ 1), and (3) as a continuous CAC score in a subsample of participants with at least some CAC (i.e., CAC > 0). The findings offer no evidence of a significant relationship between either CAC and CIMT, and total HV in this community-based sample. Other risk factors for CAD disease – including BMI, systolic blood pressure, total and HDL cholesterol, smoking, and history of diabetes – were not significantly related to HV. These findings are somewhat contrary to those of Koschack et al., who compared 20 cognitively normal men with CAD and 20 matched, healthy control subjects (4). However, unlike those in the present study, all participants in the Koschack et al. study had known CAD, 11 of which were scheduled for coronary artery bypass grafting at the time of the study. Koschack et al. also only included men who were approximately 10 years older, on average, than those in the DHS. In contrast people with history of myocardial infarction or stroke were excluded from the current analysis.

Results from the present study also suggest a non-significant association between CIMT and total HV. There are mixed results in the literature regarding this relationship with a cross-sectional analysis, as in the current report, from the Framingham Offspring Cohort observing a non-significant relationship between CIMT and hippocampal volume (9, 10). This discrepancy suggests that perhaps it is the progression of CIMT, representing the buildup of carotid atherosclerosis, that predicts total HV rather than the snapshot of CIMT afforded by one cross-sectional measurement. Importantly, studies in which the Framingham Offspring Cohort were also, on average, older than those in the DHS.

Past research has shown significant relationships between CAD and cognitive decline, as well as between CAD and total HV (1–3). One proposed hypothesis for the mechanism underlying these relationships has been cerebral hypoperfusion. It is theorized that cerebral hypoperfusion over time leads to decreased transport of glucose and oxygen in neurons, predisposing these neurons to degeneration and development of Alzheimer-associated pathologies, such as neurofibrillary tangles and atherosclerotic plaques, as well as amyloid angiopathy (5). Several studies have confirmed an association between vascular pathologies and cognitive impairment or dementia (3, 23–27). However, the results of the current study suggest that total HV, an antecedent to dementia, is not associated with either of the two predictors of cardiovascular disease risk examined here – CAC and CIMT. Thus, further research on the type of pathologic insults to the brain caused by cerebral hypoperfusion may be warranted. Additionally, more sensitive measures of the hippocampus, such as subfield volumes or functional imaging, might demonstrate a stronger relationship with CAC or CIMT.

Study Limitations

The results reported here address previously identified gaps in the literature and are strengthened by the large sample size and multiethnic population. However, there were several limitations of the study as well. The cross-sectional nature of the study prevented assessment of CAC, CIMT, and total HV over time. Furthermore, the relatively young average age of participants, the majority who had no CAC, may have limited our ability to detect relationships between vascular disease markers and HV. Onset of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia typically occurs at 60 years or older (28). Consequently, many studies reporting a significant relationship were conducted in individuals belonging to this age category. For example, in their prospective study on atherosclerotic disease, Bos et al. found a statistically significant relationship between atherosclerosis and cognitive decline in a sample with a mean age of 69.5 years (23). Newman et al, in their longitudinal cohort study on dementia and CAD included only participants 65 years or older (3). In contrast, the DHS participants included here were approximately 50 years of age, on average. However, the current analysis did not find a relationship between CAC or CIMT and HV in the subgroup of participants 65 years old and above. A caveat is that this subgroup had a much smaller sample size, and therefore less power, than the overall sample. An additional limitation is that by excluding individuals with history of myocardial infarction, individuals with the highest CAC burden may have been excluded at a higher rate in comparison to those with lower CAC burden, as higher burden of CAC is a strong predictor of incidence of myocardial infarction (24). Consequently, if those a with history of myocardial infarction that had higher CAC burden also had significantly lower total HV, our study would not have detected these individuals. However, a study including individuals with history of myocardial infarction would not be able to account for confounding factors affecting the relationship between history of myocardial infarction and HV.

CONCLUSION

Results from the present study suggested only non-significant relationships between either CAC or CIMT and total HV. This finding needs replication. Futures research is needed to examine these relationships longitudinally, in older populations, while using more sensitive measures of hippocampal changes.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank the UT Southwestern Office of Medical Student Research.

Funding:

No external funding was obtained for this secondary analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Dr. Brown serves on advisory boards for Sage Pharmaceuticals and Medscape/WebMD on topics unrelated to the current study. None of the other authors report any potentially relevant disclosures.

Ethical Publication Statement: The Dallas Heart Study was approved by the UT Southwestern IRB and adhered to the guidelines set forth by the Office of Human Research Protection that is supported by U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. All participants provided written informed consent. De-identified data were used for this secondary analysis.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.van Oijen M, Jan de Jong F, Witteman JC, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Atherosclerosis and risk for dementia. Annals of Neurology: Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society 2007;61(5):403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenland P, Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, Erbel R, Watson KE. Coronary calcium score and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72(4):434–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman AB, Fitzpatrick AL, Lopez O, Jackson S, Lyketsos C, Jagust W, et al. Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease incidence in relationship to cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53(7):1101–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koschack J, Irle E. Small hippocampal size in cognitively normal subjects with coronary artery disease. Neurobiol Aging 2005;26(6):865–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fowkes R, Byrne M, Sinclair H, Tang E, Kunadian V. Coronary artery disease in patients with dementia. Coron Artery Dis 2016;27(6):511–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sojkova J, Najjar SS, Beason-Held LL, Metter EJ, Davatzikos C, Kraut MA, et al. Intima-media thickness and regional cerebral blood flow in older adults. Stroke 2010;41(2):273–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nezu T, Hosomi N, Aoki S, Matsumoto M. Carotid Intima-Media Thickness for Atherosclerosis. J Atheroscler Thromb 2016;23(1):18–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nambi V, Chambless L, Folsom AR, He M, Hu Y, Mosley T, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness and presence or absence of plaque improves prediction of coronary heart disease risk: the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55(15):1600–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romero JR, Beiser A, Seshadri S, Benjamin EJ, Polak JF, Vasan RS, et al. Carotid artery atherosclerosis, MRI indices of brain ischemia, aging, and cognitive impairment: the Framingham study. Stroke 2009;40(5):1590–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baradaran H, Demissie S, Himali JJ, Beiser A, Gupta A, Polak JF, et al. The progression of carotid atherosclerosis and imaging markers of dementia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 2020;6(1):e12015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Csernansky JG, Wang L, Swank J, Miller JP, Gado M, Mckeel D, et al. Preclinical detection of Alzheimer’s disease: hippocampal shape and volume predict dementia onset in the elderly. Neuroimage 2005;25(3):783–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morra JH, Tu Z, Apostolova LG, Green AE, Avedissian C, Madsen SK, et al. Automated 3D mapping of hippocampal atrophy and its clinical correlates in 400 subjects with Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, and elderly controls. Hum Brain Mapp 2009;30(9):2766–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steffens DC, Payne ME, Greenberg DL, Byrum CE, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Wagner HR, et al. Hippocampal volume and incident dementia in geriatric depression. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry 2002;10(1):62–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.den Heijer T, van der Lijn F, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, van der Lugt A, Krestin GP, et al. A 10-year follow-up of hippocampal volume on magnetic resonance imaging in early dementia and cognitive decline. Brain 2010;133(Pt 4):1163–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.den Heijer T, Geerlings MI, Hoebeek FE, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Use of hippocampal and amygdalar volumes on magnetic resonance imaging to predict dementia in cognitively intact elderly people. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63(1):57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Victor RG, Haley RW, Willett DL, Peshock RM, Vaeth PC, Leonard D, et al. The Dallas Heart Study: a population-based probability sample for the multidisciplinary study of ethnic differences in cardiovascular health. Am J Cardiol 2004;93(12):1473–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paixao ARM, Neeland IJ, Ayers CR, Xing F, Berry JD, de Lemos JA, et al. Defining coronary artery calcium concordance and repeatability - Implications for development and change: The Dallas Heart Study. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2017;11(5):347–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta M, King KS, Srinivasa R, Weiner MF, Hulsey K, Ayers CR, et al. Association of 3.0-T brain magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers with cognitive function in the Dallas Heart Study. JAMA neurology 2015;72(2):170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta M, King KS, Srinivasa R, Weiner MF, Hulsey K, Ayers CR, et al. Association of 3.0-T brain magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers with cognitive function in the Dallas Heart Study. JAMA neurology 2015;72(2):170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucarelli R, Peshock RM, McColl R, Hulsey K, Ayers C, Whittemore AR, et al. MR imaging of hippocampal asymmetry at 3T in a multiethnic, population-based sample: results from the Dallas Heart Study. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2013;34(4):752–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naglich A, Van Enkevort E, Adinoff B, Brown ES. Association of Biological Markers of Alcohol Consumption and Self-Reported Drinking with Hippocampal Volume in a Population-Based Sample of Adults. Alcohol Alcohol 2018;53(5):539–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowther MK, Tunnell JP, Palka JM, King DR, Salako DC, Macris DG, et al. Relationship between inflammatory biomarker galectin-3 and hippocampal volume in a community study. J Neuroimmunol 2020;348:577386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bos D, Vernooij MW, de Bruijn RF, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Franco OH, et al. Atherosclerotic calcification is related to a higher risk of dementia and cognitive decline. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2015;11(6):639–47. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams MC, Kwiecinski J, Doris M, McElhinney P, D’Souza MS, Cadet S, et al. Low-attenuation noncalcified plaque on coronary computed tomography angiography predicts myocardial infarction: results from the multicenter SCOT-HEART trial (Scottish Computed Tomography of the HEART). Circulation 2020;141(18):1452–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuller LH, Lopez OL, Mackey RH, Rosano C, Edmundowicz D, Becker JT, et al. Subclinical cardiovascular disease and death, dementia, and coronary heart disease in patients 80+ years. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67(9):1013–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roher AE, Tyas SL, Maarouf CL, Daugs ID, Kokjohn TA, Emmerling MR, et al. Intracranial atherosclerosis as a contributing factor to Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2011;7(4):436–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Debette S, Beiser A, DeCarli C, Au R, Himali JJ, Kelly-Hayes M, et al. Association of MRI markers of vascular brain injury with incident stroke, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and mortality: the Framingham Offspring Study. Stroke 2010;41(4):600–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiu C, Kivipelto M, von Strauss E. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease: occurrence, determinants, and strategies toward intervention. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2009;11(2):111–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]