Abstract

Introduction:

The objective of this study was to determine rates and trends in reporting of preferred language, socioeconomic factors, and sexual orientation and gender identity in published pediatric clinical trials.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study of pediatric clinical trials conducted in the United States published from January 1, 2011 through December 31, 2020 in five general pediatric and five general medical journals with the highest impact factor in their respective fields was performed. Outcomes were reporting of preferred language, socioeconomic factors, sexual orientation, and gender identity. In late 2021, descriptive statistics and logistic regression to understand how reporting of preferred language and socioeconomic factors changed over time were performed.

Results:

Of 612 trials, 29.6% (n=181) reported preferred language. Among these, 64.6% (n=117/181) exclusively enrolled participants whose preferred language was English. From 2011-2020, there was a relative increase in reporting of preferred language (8.6% per year, 95% CI 1.8, 16.0). Socioeconomic factors were reported in 47.9% (n=293) of trials. There was no significant change in the reporting of socioeconomic factors (8.2% per year, 95% CI −1.9, 15.1). Only 5.1% (9/179) of published trial results among adolescent participants reported any measure of sexual orientation and 1.1% (2/179) reported gender identity.

Conclusions:

Preferred language, socioeconomic factors, sexual orientation, and gender identity were infrequently reported in pediatric clinical trial results despite these characteristics being increasingly recognized as social determinants of health. To achieve more inclusiveness and to reduce unmeasured disparities, these characteristics should be incorporated into routine trial registration, design, funding decisions, and reporting.

Keywords: pediatrics, Clinical trials, Language, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation

Introduction

Children with preferred languages other than English, in low-income families, and who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ+) have worse health outcomes in the United States (U.S.) than children without these characteristics. Children with preferred languages other than English have higher rates of medication dosing errors, unplanned emergency department return visits, and adverse events while hospitalized.1-4 Children with lower socioeconomic status receive less care for the same conditions, have worse management of chronic conditions including cancer, and have higher rates of mortality than children of higher socioeconomic status.5-10 LGBTQ+ individuals have less access to healthcare, higher rates of psychiatric conditions including depression and suicidality, and are more likely to have unstable housing situations than children who are not LGBTQ+.11-14 One of biomedical research’s fundamental roles is to evaluate and address health inequities as well as investigate how interventions impact diverse populations.15

For over 25 years, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) have recommended that clinical trial investigators provide materials and staff that facilitate the participation of individuals with preferred languages other than English, and that informed consent information be presented “in language understandable to the subject”.16,17 The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) has designated “sexual and gender minorities as a health disparity population alongside racial and ethnic minorities, and socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.”18 The HHS, the National Academy of Medicine, the Joint Commission, and the National Academy of Sciences have recommended routine collection of patients' sexual orientation in health care settings, including clinical trials.19-22 Despite these recommendations, preferred language, socioeconomic factors, and sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) are not recorded in a standardized way in most administrative databases or electronic health records.23,24

Clinical trials provide the highest level of evidence for medications and interventions that guide and improve clinical care.25 In adult clinical trials, as few as 4-15% of published results reported measures of socioeconomic factors and only 22% reported participant SOGI.26,27 Failure to report these important participant characteristics may perpetuate known disparities, miss unrecognized health inequities, and hamper the creation of interventions needed to reduce health inequities.28

Despite the documented disparities in pediatric outcomes by preferred language, socioeconomic factors, and SOGI, an understanding of pediatric participant enrollment in clinical trials by these characteristics is lacking. Characterization of reporting of these demographics in trial enrollment has the potential to inform future reporting, recruitment strategies, and research priorities. This study was conducted to evaluate multiple domains of trial reporting in a sample previously used to explore the reporting of participants’ race and ethnicity.29 The objective was to determine rates and trends in reporting of these characteristics in pediatric clinical trials published in leading general pediatric and medical journals.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional analysis of articles published in five general pediatric journals and five general medical journals over a 10-year period. This study was exempted from review by the Boston Children’s Hospital institutional review board since all data were publicly available and no identifiable patient information collected.

Study Sample

The detailed methodology related to an analysis of reporting of race and ethnicity has been reported previously.29 Briefly, in this secondary analysis to evaluate the reporting of participant/caregiver preferred language, socioeconomic factors, and SOGI in pediatric clinical trials, articles published in the five general pediatrics journals with the highest impact factor (i.e., JAMA Pediatrics, Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, Pediatrics, Journal of Adolescent Health, and the Journal of Pediatrics) and the five general medical journals with the highest impact factor (i.e., New England Journal of Medicine, Lancet, JAMA, British Medical Journal, and PLoS Medicine) according to impact factor in the Web of Science’s Journal Citation Report in 2019 were reviewed.30 These journals were selected because it was thought they would be likely to publish the most impactful pediatric clinical trial results which had the highest likelihood of influencing clinical care for children and adolescents. Articles published from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2020 were reviewed.

To determine which articles reported clinical trial results, the NIH definition of a clinical trial was used.31 Articles that reported pediatric clinical trial results, defined as those in which enrolled participants were 0-18 years of age or in which the median or mean age of participants was ≤18 years were included. Articles reporting clinical trials conducted outside the U.S. and secondary analyses of clinical trials (if the original clinical trial publication was included in the dataset) were excluded.

Measures

PubMed was queried to identify published articles in the selected journals (Appendix Query). The abstract and full text of each article were screened and reviewed by a member of the team of investigators (i.e., CAR, AMS, ENP, SM, EA, JJ, JM, or EWF) to identify pediatric clinical trials. The following trial characteristics were extracted: randomization, masking, trial phase, intervention type, disease(s) studied, listed funding sources, and trial location(s). The number of enrolled participants, participant age group(s), and, whenever reported, participant/caregiver preferred language, participant socioeconomic factors, sex, and SOGI as reported were extracted. Sex and SOGI were only collected from trials that primarily enrolled school age children or adolescents. Preferred languages were extracted as reported in the published trial results. Distinction between preferred language for medical care, primary language spoken at home, or U.S. Census questions about English proficiency was not made in the published articles. Socioeconomic factors were extracted as reported in the published trial results and included: insurance type or status, household income, community level income (e.g., county, ZIP code, neighborhood, etc.), caregiver education, caregiver employment status, or other.

The REDCap platform was used to collect and manage all data.32 Variables were extracted from the primary article, online supporting supplementary information, or the corresponding entry in ClinicalTrials.gov.

The primary outcome was the proportion of published pediatric clinical trials that reported participant/caregiver preferred language, socioeconomic factors, and SOGI in trial enrollment. As there was no standardized list of preferred languages, socioeconomic variables, or method of reporting SOGI used across the included articles, these variables were recorded as reported in the published article or supplemental information.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the number of published pediatric clinical trials that reported participant/caregiver preferred language, socioeconomic factors, and SOGI. To understand how reporting of participant/caregiver preferred language and socioeconomic factors changed over time, a hierarchical logistic regression model at the level of individual studies, with preferred language or socioeconomic factors reported as the dependent variable and year as the independent variable was constructed, with a random intercept for journal to address heterogeneity in journal reporting rate trends. An exploratory analysis was conducted using logistic regression to test associations between the outcomes of reporting preferred language and of socioeconomic factors using several trial characteristics that were hypothesized to be associated with the reporting of these outcomes. Candidate variables included participant age group, trial allocation (i.e., randomized vs. not randomized), trial size, intervention type (e.g., drug/biologic, behavioral intervention, etc.), and funding category. As the number of trials reporting SOGI data was limited, factors associated with reporting of participant SOGI or test for change over time were not assessed. P <0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were conducted using the statistical software package R version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

There were 99,866 articles, 3,782 potentially related to pediatric clinical trials, and 612 reported results of pediatric clinical trials.29 Most of the trials were randomized (93.8%, n=574) and publicly funded (55.9%, n=342) (Table 1). Nearly half of the trials enrolled 100-499 participants (46.4%, n=284). There were 28.8% (n=176) trials that primarily enrolled adolescent participants and 22.5% (n=138) that primarily enrolled pre-school and school age children. There were 565,618 total participants enrolled in the included published trials.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 612 pediatric trials published in leading general pediatric and medical journalsa

| Trial Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Participant age group in article | |

| All pediatric age groups | 91 (14.9) |

| Neonate (0-30 days) | 115 (18.8) |

| Infants and toddlers (31 days-3 years) | 92 (15.0) |

| Pre-school and school age (4-12 years) | 138 (22.5) |

| Adolescent (13-18 years) | 176 (28.8) |

| Trial allocation | |

| Randomized | 574 (93.8) |

| Not randomized | 38 (6.2) |

| Participant enrollment | |

| <100 | 172 (28.1) |

| 100-499 | 284 (46.4) |

| ≥500 | 156 (25.5) |

| Trial intervention | |

| Behavioral | 244 (39.9) |

| Drug/biologic/dietary supplement | 239 (39.1) |

| Device/procedure | 75 (12.3) |

| Screening/Referral/Health services | 54 (8.7) |

| Funding source | |

| Public | 342 (55.9) |

| Private | 112 (18.3) |

| Public and Private | 128 (20.9) |

| None Reported | 30 (4.9) |

| Participant preferred language reported | 181 (29.6) |

| Socioeconomic factor(s) reported | 293 (47.9) |

| Sex reported (N=282) b | 272 (96.1) |

| Sexual orientation reported (N=282) b | 9 (1.5) |

| Gender identity reported (N=282) b | 2 (0.7) |

JAMA Pediatrics, Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, Pediatrics, Journal of Adolescent Health, the Journal of Pediatrics, New England Journal of Medicine, Lancet, JAMA, BMJ, and PLoS Medicine

There were 282 trials that enrolled school age or adolescent participants.

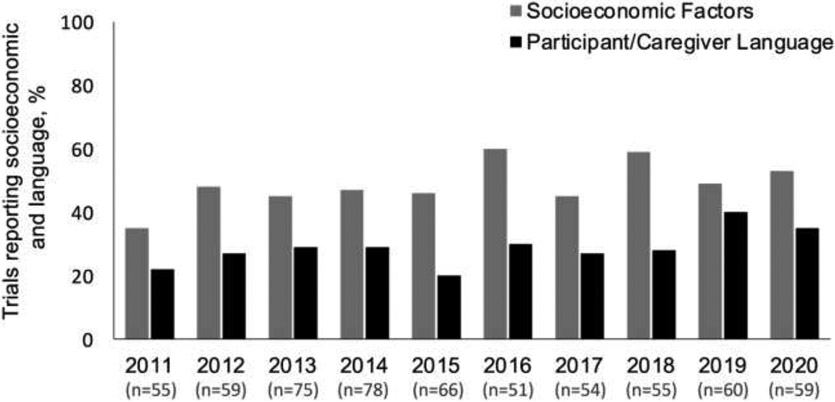

Of the 612 included published pediatric clinical trials, 29.6% (n=181) reported participant/caregiver preferred language. There was a relative increase in reporting of participant/caregiver preferred language during the study period (8.6% per year, 95% CI 1.8, 16.0) (Figure 1). Among trials that reported participant/caregiver preferred language, 64.6% (117/181) exclusively enrolled participants whose preferred language was English. Among the 64 trials that reported non-English speakers, 72% (n=46/64) reported including consent materials in languages other than English (43 in Spanish, 1 in Portuguese, 1 in Arabic, and 1 in Haitian Creole). Likewise, of the 64 trials that reported languages other than English, only 42% (n=27/64) reported having interpreters available for trial enrollment (25 with Spanish interpreters and 2 with unspecified language interpreters).

Figure 1. Trends in reporting of participant/caregiver preferred language and socioeconomic status from 2011-2020.a.

aReporting of participant sexual orientation and gender identity were too small to trend over the study period.

Besides English, the most reported participant/caregiver preferred language was Spanish (46.9%, 85/181). Eleven (6.1%) published trials reported that participants spoke other languages, but these were not specified. Only 15.1% (n=85,139/565,618) of participants’ preferred language was reported in the included published trial results.

Pediatric clinical trials that primarily enrolled infants and toddlers were more likely to report participant/caregiver preferred language than trials that primarily enrolled neonates when adjusting for other variables (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.32, 95% CI 1.14, 4.81) (Table 2). Published trials that evaluated behavioral interventions and screening/referral, or health services interventions were more likely to report participant/caregiver preferred language than trials for drugs/biologics/dietary supplements (aOR 5.14, 95% CI 3.15, 8.59 and aOR 4.87, 95% CI 2.42, 9.85, respectively).

Table 2.

Factors associated with pediatric clinical trial reporting of participant/caregiver preferred language

| Trial Characteristics | Reported Language (N=181), n (%) |

Did Not Report Language (N=431), n (%) |

Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant age group in article | ||||

| All pediatric age groups | 28 (15.4) | 63 (14.6) | 1.48 (0.71, 3.15) | 0.30 |

| Neonate (0-30 days) | 17 (9.4) | 98 (22.7) | Referent | |

| Infants and toddlers (31 days-3 years) | 36 (19.9) | 56 (13.0) | 2.32 (1.14, 4.81) | 0.02 |

| Pre-school and school age (4-12 years) | 36 (19.9) | 102 (23.7) | 0.86 (0.42, 1.78) | 0.68 |

| Adolescent (13-18 years) | 64 (35.4) | 112 (26.0) | 1.16 (0.58, 2.37) | 0.68 |

| Trial allocation | ||||

| Not randomized | 6 (3.3) | 32 (7.4) | Referent | |

| Randomized | 175 (96.7) | 399 (92.6) | 1.98 (0.80, 5.68) | 0.16 |

| Trial enrollment | ||||

| <100 | 45 (24.9) | 127 (29.5) | Referent | |

| 100-499 | 89 (49.2) | 195 (45.2) | 0.89 (0.55, 1.44) | 0.63 |

| ≥500 | 47 (25.9) | 109 (25.3) | 0.58 (0.33, 1.01) | 0.06 |

| Trial intervention | ||||

| Drug/biologic/dietary supplement | 37 (20.4) | 202 (46.9) | Referent | |

| Behavioral | 110 (60.8) | 134 (31.1) | 5.14 (3.15, 8.59) | <0.001 |

| Device/procedure | 11 (6.1) | 64 (14.8) | 1.02 (0.46, 2.11) | 0.97 |

| Screening/Referral or Health services | 23 (12.7) | 31 (7.2) | 4.87 (2.42, 9.85) | <0.001 |

| Funding source | ||||

| Public and Private | 36 (19.9) | 92 (21.3) | Referent | |

| Private | 30 (16.6) | 82 (19.0) | 1.02 (0.55, 1.88) | 0.95 |

| Public | 109 (60.2) | 233 (54.1) | 1.15 (0.71, 1.89) | 0.56 |

| None Reported | 6 (3.3) | 24 (5.6) | 1.06 (0.34, 3.01) | 0.91 |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (P<0.05).

There were 293 (47.9%) articles reporting some measure of participant socioeconomic factors. There was no significant change in the reporting of socioeconomic factors (8.2% per year, 95% CI −1.9, 15.1) (Figure 1). The 293 trials reporting any measure of participant socioeconomic factors described 13 different socioeconomic measures (Appendix Table). Among all studies, caregiver education (31.0%, n=190/612) and household income (22.1%, n=135/612) were the most reported measures.

Pediatric clinical trials that primarily enrolled infants and toddlers were more likely to report socioeconomic factors than trials that primarily enrolled neonates (aOR 2.04, 95% CI 1.04, 4.06) (Table 3). Trials enrolling 100-499 and ≥500 participants were more likely to report participant socioeconomic factors than trials that enrolled fewer than 100 participants (aOR 2.05, 95% CI 1.26, 3.35 and aOR 2.02, 95% CI 1.15, 3.56, respectively). Trials that evaluated behavioral interventions and screening/referral, or health services interventions were more likely to report socioeconomic factors compared to trials for drugs/biologics/dietary supplements (aOR 8.48, 95% CI 5.22, 14.11 and aOR 18.16, 95% CI 7.86, 47.07, respectively). Trials that were privately funded and those that did not report a funding source were less likely to report socioeconomic factors than trials with combined public and private funding (aOR 0.39, 95% CI 0.21, 0.72 and aOR 0.20, 95% CI 0.04, 0.68, respectively).

Table 3.

Factors associated with pediatric clinical trial reporting of participant socioeconomic factors

| Trial Characteristics | Reported Socioeconomic Factors (N=293), n (%) |

Did Not Report Socioeconomic Factors (N=319), n (%) |

Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant age group in article | ||||

| All pediatric age groups | 39 (13.3) | 52 (16.3) | 0.81 (0.39, 1.66) | 0.56 |

| Neonate (0-30 days) | 31 (10.6) | 84 (26.3) | Referent | |

| Infants and toddlers (31 days-3 years) | 55 (18.8) | 37 (11.6) | 2.04 (1.04, 4.06) | 0.04 |

| Pre-school and school age (4-12 years) | 77 (26.3) | 61 (19.1) | 1.07 (0.56, 2.06) | 0.83 |

| Adolescent (13-18 years) | 91 (31.1) | 85 (26.6) | 0.57 (0.29, 1.11) | 0.10 |

| Trial allocation | ||||

| Not randomized | 9 (3.1) | 29 (9.1) | Referent | |

| Randomized | 284 (96.9) | 290 (90.9) | 2.29 (0.90, 6.37) | 0.10 |

| Trial enrollment | ||||

| <100 | 45 (15.4) | 127 (39.8) | Referent | |

| 100-499 | 149 (50.9) | 135 (42.3) | 2.05 (1.26, 3.35) | 0.004 |

| ≥500 | 99 (33.8) | 57 (17.9) | 2.02 (1.15, 3.56) | 0.01 |

| Trial intervention | ||||

| Drug/biologic/dietary supplement | 57 (19.5) | 182 (57.1) | Referent | |

| Behavioral | 171 (58.4) | 73 (22.9) | 8.48 (5.22, 14.11) | <0.001 |

| Device/procedure | 19 (6.5) | 56 (17.6) | 1.00 (0.52, 1.87) | 0.99 |

| Screening/Referral or Health services | 46 (15.7) | 8 (2.5) | 18.16 (7.86, 47.07) | <0.001 |

| Funding source | ||||

| Public and Private | 68 (23.2) | 60 (18.8) | Referent | |

| Private | 36 (12.3) | 76 (23.8) | 0.39 (0.21, 0.72) | 0.003 |

| Public | 186 (63.5) | 156 (48.9) | 0.89 (0.54, 1.45) | 0.63 |

| None Reported | 3 (1.0) | 27 (8.5) | 0.20 (0.04, 0.68) | 0.02 |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (P<0.05).

Only 5.1% (9/179) of trial results among adolescent participants reported participant sexual orientation and only 1.1% (2/179) reported measure of participants gender identity. No trials that enrolled school-aged children reported SOGI. Four of the publications that reported sexual orientation were trials that assessed HIV-focused interventions and the other five reported sexual health-related interventions. Among the two trials that reported gender identity, one was an intervention targeting sexual-minority youths and the other was an assessment of adolescents’ response to cigarette packaging.

Discussion

Across a wide range of clinical trials there was underreporting of social determinants of health including preferred language, socioeconomic factors, and SOGI. Participant/caregiver preferred language was infrequently reported in published pediatric clinical trials and though participant/caregiver socioeconomic factors were more commonly reported, these data were still reported in less than half of published trial results and used a wide range of measures that makes potential comparison of results across studies difficult. Reporting of participant sex was common, but SOGI were rarely reported. Though the collection of these variables in clinical trials may create the need for additional time spent collecting data and may lead to some participants/caregivers wondering why these are collected, the inclusion of these well-documented social determinants of health will help standardize sociodemographic data collection.

Preferred language was infrequently reported in this sample. When preferred language was reported, nearly two-thirds of published trials excluded non-English speaking participants/caregivers, despite over 13% of people living in the U.S. (i.e., 60 million) who report that they speak a language other than English at home.33 Thus, pediatric clinical trial enrollment was exclusionary of a large proportion of children in the U.S. based on primary language alone. Lack of equitable representation by preferred language limits the generalizability of research findings to diverse patient populations and may perpetuate extant health disparities. The exclusion of participants whose preferred language was not English is disconcerting in light of recommendations put forth by the HHS in 1995 and recently reiterated by the FDA to encourage the participation of individuals who speak all languages.16,17 While federal policies mandate the provision of healthcare to patients in a language they understand,34 there are no such policies mandating the inclusion of participants who prefer a language other than English in research. Some funders discourage exclusion of research participants based on their preferred language. Additional policies regarding the inclusion of patients who prefer a language other than English may be needed.35-37

Though structural and individual barriers including systemic racism, researcher bias, immigration status, and distrust of healthcare systems may reduce clinical trial enrollment,38 the default of enrolling English-speaking participants is likely the result of convenience, resource limitations, and the hegemony of English in health care.39 Recruitment and enrollment of participants whose preferred language is not English requires the provision of translated enrollment materials and interpreters, which add additional costs to research. However, if pediatric trials are meant to be representative of all pediatric populations, such provisions should be made available. The Affordable Care Act mandates the availability of interpreters for clinical care;40 if the same requirement for medical research was implemented this could improve clinical research recruitment efforts of patients with a preferred language other than English. Language-concordance has been shown to improve health outcomes and may also improve representation in research.41 Recruiting and retaining linguistically diverse clinical investigators and research staff could facilitate greater enrollment of linguistically diverse participants.

Fewer than half of clinical trial publications included participant/caregiver socioeconomic factors, but this was more common in behavioral and screening/referral or health services trials. There is mounting evidence that socioeconomic factors including neighborhood poverty, insurance type and status, and health literacy are important determinants of pediatric health.5,7,42-47 It is important to note that disparities in outcomes by these social determinants of health are determined by societal and systemic factors. Recognition of the influence of socioeconomic factors on pediatric health among investigators may partially explain the greater reporting of participant/caregiver socioeconomic factors in this study. This study’s results suggest that pediatric clinical trials that enrolled larger numbers of participants and those that studied behavioral and screening interventions were more likely to report participant/caregiver socioeconomic factors. Trialists evaluating behavioral interventions may have greater recognition of socioeconomic factors’ role in health outcomes, given the association of poverty and behavioral health disorders in children.48

Participant sex has long been acknowledged as a biological variable that should be incorporated in research.49 This study demonstrated that nearly all published pediatric clinical trials enrolling older children reported participant sex. In contrast, SOGI were rarely reported. In 2015 there were an estimated 1.3 million high school students in the U.S. who identified as LGBQ+; as of 2019 11.7% of high school students identified as non-heterosexual and 13.3% had same-sex sexual contact.50-52 Likewise, nearly 10% of U.S. adolescents have a gender-diverse identity (e.g., trans girl, trans boy, genderqueer, nonbinary).53 Though LGBTQ+ identity may not have surface-level biologically plausible reasons to suspect differences in intervention outcomes, it must be recognized that neither do race, ethnicity, language preference, nor socioeconomic status. Yet research shows that these factors are true determinants of health. Rather than ignore SOGI status among participants, researchers should appreciate that LGBTQ+ individuals experience higher rates of stigma, discrimination, mental and behavioral health challenges, health risk behaviors, and poor health outcomes.11-14 Thus, it is important to understand how these individuals may have different outcomes within clinical trials. Standardization of best practices for SOGI data collection is needed for clinical trials. SOGI questions from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, PhenX Toolkit, and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System offer a starting point by providing easy-to-implement questions.52,54-56 Additionally, Harvard Medical School recently published recommendations for data collection around SOGI and sex development with proposed questionnaires to facilitate this process.57

Limitations

This study is subject to several limitations. This sample of published pediatric clinical trials in medical journals with the highest impact factor is not representative of all pediatric clinical trial results and may have introduced some bias in reporting of these key participant characteristics. Though there are standardized questions put forth by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities to assess participant English proficiency,58 this study could not distinguish between preferred language for medical encounters, language preference for written or verbal medical communication, or language spoken at home. This study was unable to confirm whether reported preferred language represents that of the caregiver or that of the pediatric participant, which is a complexity inherent to pediatric research.59 Additionally, this study did not assess the reporting of health literacy. Lastly, this study assessed the reporting of preferred language, socioeconomic factors, and SOGI and was not designed to determine if these data were obtained as part of the pediatric trials or not.

Conclusions

Participant/caregiver preferred language and participant SOGI were infrequently reported in published pediatric clinical trial results. However, participant socioeconomic factors were reported in nearly half of all published clinical trial results. The proportion of published pediatric clinical trials that reported participant/caregiver preferred language increased from 2011 to 2020 but was still underreported. To achieve more inclusive pediatric clinical trials and to ensure that clinical trial results are generalizable and address disparities, researchers need to broaden their perspective on demographics, should incorporate these factors into their data gathering and analysis, and work to delineate and report how these differences ultimately affect participants response to research to improve care for all children. Finally, funding and publishing entities should consider these factors in deciding which trials to support and disseminate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Chloe Rotman, MSLIS at Boston Children’s Hospital for her assistance in developing the PubMed query as well as acquiring the full text articles reviewed in this study. Chloe Rotman did not receive compensation for her contributions.

CPD was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (K24DK104676 and 2P30 DK040561). KAM was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K08HS026503). The funders/sponsors did not participate in the work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Part of these data were presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting in Denver, Colorado in April 2022.

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. No financial disclosures have been reported by the authors of this paper.

Credit author statement

Chris A. Rees, Eric W. Fleegler: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Project administration, Resources, Writing - original draft

Amanda M. Stewart, Elyse N. Portillo, Sagar Mehta, Elorm Avakame, Jasmyne Jackson, Jheanelle McKay: Data curation, Validation, Writing - review & editing

Kenneth A. Michelson: Formal analysis, Visualization, Software, Writing - review & editing

Christopher P. Duggan: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - review & editing

References

- 1.Harris LM, Dreyer BP, Mendelsohn AL, et al. Liquid Medication Dosing Errors by Hispanic Parents: Role of Health Literacy and English Proficiency. AcadPediatr. 2017;17(4):403–410. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Portillo EN, Anne MPH, Michael MS, et al. Association of limited English proficiency and increased pediatric emergency department revisits. 2021;28(9):1001–1011. doi: 10.1111/acem.14359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen AL, Rivara F, Marcuse EK, McPhillips H, Davis R. Are language barriers associated with serious medical events in hospitalized pediatric patients? Pediatrics 2005;116(3):575–579. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan A, Yin HS, Brach C, et al. Association between Parent Comfort with English and Adverse Events among Hospitalized Children. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(12): e203215. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rees CA, Pryor S, Choi B, et al. The influence of insurance type on interfacility pediatric emergency department transfers. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(12):1907–1909. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang L, Rees CA, Michelson KA. Association of Socioeconomic Characteristics With Where Children Receive Emergency Care. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2022. 1;38(1):e264–e267. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rees CA, Monuteaux MC, Raphael JL, Michelson KA. Disparities in Pediatric Mortality by Neighborhood Income in United States Emergency Departments. J Pediatr. 2020;219:209–215.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colvin JD, Zaniletti I, Fieldston ES, et al. Socioeconomic status and in-hospital pediatric mortality. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e182–e190. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasegawa K, Stoll SJ, Ahn J, et al. Association of insurance status with severity and management in ED patients with asthma exacerbation. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17(1):22–27. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.11.28715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aristizabal P, Winestone LE, Umaretiya P, Bona K. Disparities in Pediatric Oncology: The 21st Century Opportunity to Improve Outcomes for Children and Adolescents With Cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ B. 2021;41:e315–e326. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_320499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchmueller T, Carpenter CS. Disparities in health insurance coverage, access, and outcomes for individuals in same-sex versus different-sex relationships, 2000-2007. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(3):489–495. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.160804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gender Martin-Storey A., sexuality, and gender nonconformity: understanding variation in functioning. Child Dev Perspect. 2016;10(4):257–262. doi.org/ 10.1111/cdep.12194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell ST, Fish JN. Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Youth. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2016;12:465–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baams L, Wilson BDM, Russell ST. LGBTQ youth in unstable housing and foster care. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20174211. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dankwa-Mullan I, Rhee KB, Williams K, et al. The science of eliminating health disparities: summary and analysis of the NIH summit recommendations. Am J Public Heal. 2010;100 Suppl(Suppl 1):S12–S18. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.191619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Office for Human Research Protections. Informed Consent of Subjects Who Do Not Speak English (1995). https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/obtaining-and-documenting-infomed-consent-non-english-speakers/index.html. Published 1995. Accessed September 7, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Food and Drug Administration. Enhancing the Diversity of Clinical Trial Populations — Eligibility Criteria, Enrollment Practices, and Trial Designs Guidance for Industry, https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/enhancing-diversity-clinical-trial-populations-eligibility-criteria-enrollment-practices-and-trial. Published 2020. Accessed September 7, 2021.

- 18.National Institutes of Health. Coordination of Sexual and Gender Minority Mental Health Research at NIMH, https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/organization/od/odwd/coordination-of-sexual-and-gender-minority-mental-health-research-at-nimh. Accessed August 31, 2021.

- 19.Healthy People 2020. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health. Published 2021. Accessed August 31, 2021.

- 20.Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Published 2011. Accessed August 31, 2022. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64806/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Joint Commission. Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient-and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT): a field guide. https://www.jointcommission.org/lgbt/. Published 2014. Accessed August 31, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Understanding the Status and Well-Being of Sexual and Gender Diverse Populations. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020 Health Disparities Data Widget. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlid=93. Published 2018. Accessed August 31, 2021.

- 24.Lion KC. Caring for Children and Families With Limited English Proficiency: Current Challenges and an Agenda for the Future. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(1):59–61. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartling L, Scott-Findlay S, Johnson D, et al. Bridging the gap between clinical research and knowledge translation in pediatric emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(11):968–977. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nalven T, Spillane NS, Schick MR WL. Diversity inclusion in United States opioid pharmacological treatment trials: A systematic review. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2021;29(5):524–538. doi: 10.1037/pha0000510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alegria M, Sud S, Steinberg BE, Gai N, Siddiqui A. Reporting of Participant Race, Sex, and Socioeconomic Status in Randomized Clinical Trials in General Medical Journals, 2015 vs 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e2111516. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker KE, Streed CG Jr, Durso LE. Ensuring That LGBTQI+ People Count - Collecting Data on Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Intersex Status. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(13):1184–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2032447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rees CA, Stewart AM, Mehta S, et al. Reporting of Participant Race and Ethnicity in Published US Pediatric Clinical Trials From 2011 to 2020. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(5):e220142. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Web of Science. Journal Citation Reports, https://jcr-clarivate-com.ezp-prodl.hul.harvard.edu/JCRLandingPageAction.action. Published 2019. Accessed November 18, 2020.

- 31.National Institutes of Health. NIH’s Definition of a Clinical Trial. https://grants.nih.gov/policy/clinical-trials/definition.htm. Published 2017. Accessed January 15, 2021.

- 32.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009. Apr;42(2):377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dietrich S, Hernandez E. Language Use in the United States: 2019. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2022/acs/acs-50.pdf. Published 2022. Accessed September 30, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 34.US Health and Human Services. Section 1557: Ensuring Meaningful Access for Individuals with Limited English Proficiency. 2016:2010. www.hhs.gov/civil-rights/for-individuals/section-1557. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curt AM, Kanak MM, Fleegler EW, Stewart AM. Increasing inclusivity in patient centered research begins with language. Prev Med (Baltim). 2021;149:106621. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Department of Justice. The President Executive Order 13166-Improving Access to Services for Persons With Limited English Proficiency Department of Justice Enforcement of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964-National Origin Discrimination Against Persons With Limited English. Federal Register. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Nondiscrimination in Health and Health Education Programs or Activities, Delegation of Authority. Federal Register. Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/06/19/2020-11758/nondiscrimination-in-health-and-health-education-programs-or-activities-delegation-of-authority. Accessed March 15, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spector-Bagdady K, Lombardo P. U.S. Public Health Service STD Experiments in Guatemala (1946-1948) and Their Aftermath. Ethics Hum Res. 2019;41(2):29–34. doi: 10.1002/eahr.500010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, Hoffsuemmer J, Martin E, Edwards D. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Heal Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):879–897. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.US Department of Health and Human Services. HHS Finalizes Rule on Section 1557 Protecting Civil Rights in Healthcare, Restoring the Rule of Law, and Relieving Americans of Billions in Excessive Costs. Available at: https://public3.pagefreezer.com/content/HHS.gov/31-12-2020T08:51/https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/06/12/hhs-finalizes-rule-section-1557-protecting-civil-rights-healthcare.html. Accessed March 20, 2022.

- 41.Diamond L, Izquierdo K, Canfield D, Matsoukas K, Gany F. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Patient-Physician Non-English Language Concordance on Quality of Care and Outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1591–1606. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04847-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mannix R, Chiang V, Stack AM. Insurance status and the care of children in the emergency department. J Pediatr. 2012;161(3):536–541.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cook Q, Argenio KL-DS. The impact of environmental injustice and social determinants of health on the role of air pollution in asthma and allergic disease in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(5):1089–1101.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barrett JT, Lee LK, Monuteaux MC, Farrell CA, Hoffmann JA, Fleegler EW. Association of County-Level Poverty and Inequities With Firearm-Related Mortality in US Youth. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(2):e214822. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farrell CA, Fleegler EW, Monuteaux MC, Wilson CR, Christian CW LL. Community Poverty and Child Abuse Fatalities in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017;139(5):pii:e20161616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jutte DP, Badruzzaman RA, Thomas-Squance R. Neighborhood Poverty and Child Health: Investing in Communities to Improve Childhood Opportunity and Well-Being. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21(8S):S184–S193. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naccarella L, Guo S. Health Equity Implementation Approach to Child Health Literacy Interventions. Child. 2022;9(9):1284. doi: 10.3390/children9091284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol Bull. 2002;128(2):330–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Institutes of Health. NIH Policy on Sex as a Biological Variable. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sex-gender/nih-policy-sex-biological-variable. Accessed December 2, 2021.

- 50.Zaza S, Kann L Barrios LC. Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adolescents: Population Estimate and Prevalence of Health Behaviors. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2355–2356. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kann L, Olsen EO, McManus T, et al. Sexual Identity, Sex of Sexual Contacts, and Health-Related Behaviors Among Students in Grades 9-12 - United States and Selected Sites, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(9):1–202. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6509a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rapoport E, Athanasian CE, Adesman A. Prevalence of Nonheterosexual Identity and Same-Sex Sexual Contact Among High School Students in the US From 2015 to 2019. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(9):970–972. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kidd KM, Sequeira GM, Douglas C, et al. Prevalence of Gender-Diverse Youth in an Urban School District. Pediatrics. 2021;147(6):e2020049823. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-049823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.BRFS. 2020 BRFSS Questionnaire. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdf-ques/2020-BRFSS-Questionnaire-508.pdf. Published 2020. Accessed December 15, 2021.

- 55.PhenX Toolkit. Protocol - Biological Sex Assigned at Birth. https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/protocols/view/11601. Published 2021. Accessed December 15, 2021.

- 56.PhenX Toolkit. Protocol - Sexual Orientation. https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/protocols/view/11701. Published 2021. Accessed December 15, 2021.

- 57.Cheloff AZ, Jarvie E, Tabaac AR, et al. Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Sex Development: Recommendations for Data Collection and Use in Clinical, Research, and Administrative Settings. Available at: https://dicp.hms.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/sites/default/files/MFDP_files/PDF/DCP-Programs/LGBT/SOGI%20Data%20Collection.pdf. Published 2022. Accessed February 11, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 58.PhenX Toolkit: Social Determinants of Health Collections. https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/collections/view/6 Published 2020. Accessed October 1, 2021

- 59.Ragavan MI, Cowden JD. The Complexities of Assessing Language and Interpreter Preferences in Pediatrics. Heal Equity. 2018;2(1):70–73. doi: 10.1089/heq.2017.0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.