Abstract

Meat production and consumption are sources of animal cruelty, responsible for several environmental problems and human health diseases, and contribute to social inequality. Vegetarianism and veganism (VEG) are two alternatives that align with calls for a transition to more ethical, sustainable, and healthier lifestyles. Following the PRISMA guidelines, we conducted a systematic literature review of 307 quantitative studies on VEG (from 1978 to 2023), collected from the Web of Science in the categories of psychology, behavioral science, social science, and consumer behavior. For a holistic view of the literature and to capture its multiple angles, we articulated our objectives by responding to the variables of “WHEN,” “WHERE,” “WHO,” “WHAT,” “WHY,” “WHICH,” and “HOW” (6W1H) regarding the VEG research. Our review highlighted that quantitative research on VEG has experienced exponential growth with an unbalanced geographical focus, accompanied by an increasing richness but also great complexity in the understating of the VEG phenomenon. The systematic literature review found different approaches from which the authors studied VEG while identifying methodological limitations. Additionally, our research provided a systematic view of factors studied on VEG and the variables associated with VEG-related behavior change. Accordingly, this study contributes to the literature in the field of VEG by mapping the most recent trends and gaps in research, clarifying existing findings, and suggesting directions for future research.

Keywords: Systematic literature review, Vegetarianism, Veganism, 6W1H

Non-standard Abbreviations

-

•

Vgt: Vegetarianism; Vgn: Veganism, M: Meat consumption; AHR: Animal-Human relationship; C: Cultured meat consumption; D: Diet; F: Food; P: Philosophy of life.

-

•

HL: Health; EN: Environment; AN: Animals; CL: Cultural & Social; SN: Sensory; FT: Faith; FN: Financial & economic; PL: Political; JS: Justice & world hunger.

-

•

A: Attitudes; M: Motivations; V: Values, T: Personality; E: Emotions; K: Knowledge; B: Behavior; I: Intentions; S: Self-efficacy or Perceived Behavioral Control; N: Networks; O: Norms; D: Identity; P: Product Attributes; F: Information.

-

•

CR: Correlational: M-CR: Mixed method study including Correlational section; EX: Experimental; EXC: Choice Experiment.

1. Introduction

Meat production contributes to animal suffering [1], environmental problems (loss of biodiversity, climate change, or water pollution) [2], and public health problems (zoonotic diseases such as COVID-19 and chronic non-communicable diseases such as type II diabetes) [3]. Consequently, there is an increasing interest in a dietary transition to reduce or exclude animal products [[4], [5], [6], [7]]. Such dietary transitions would directly support goal 12 of the Agenda for Sustainable Development of the United Nations (2019), which is to “ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns” [8]. Adopting and maintaining vegetarian and vegan lifestyles are two of the most promising ways to achieve this goal [9,10].

VEG has a long history, dating back to ancient Greek philosophers, and can encompass various underlying approaches, including dietary behaviors, food and other product choices, social justice movements, and political activism [11]. Vegetarianism, as a philosophy of life, generally relates to the protection of non-human animals (hereafter referred to as “animals”), which, in practice, translates to a lifestyle that abstains from the consumption of all types of animal flesh, including meat (i.e., beef, pork), poultry (i.e., chicken, turkey), and fish and seafood [12]. Vegetarianism comprises several modalities: ovo-vegetarianism (accepts the consumption of eggs but not dairy products), lacto-vegetarianism (accepts the consumption of dairy products but not eggs), or lacto-ovo-vegetarianism (accepts the consumption of both eggs and dairy products) [13,14]. By contrast, veganism can be understood as a philosophy of life rooted in anti-speciesism, which, in practice, translates to rejecting the consumption of any product (or service) which involves the exploitation of an animal either in the context of food (meat, eggs, dairy, honey, gelatin), clothing (leather, silk), or any other form (entertainment and experimentation) as far as possible and practicable [15,16]. Veganism also promotes the production and consumption of alternatives free of animal use. To address vegetarianism and veganism (VEG), both of which avoid animal flesh products, many authors use the term “veg*an-ism” [8,17].

Over the last 50 years, the interest of consumers, entrepreneurs, and public institutions in the VEG phenomenon has grown [18,19]. VEG has increasingly spread worldwide [7,18,20,21]; for example, the number of individuals following some kind of VEG lifestyles is considered to have doubled from 2009 to 2016 [21], with 2019 being labelled “the year of the vegan” by The Economist [8]. The growing realization of the importance of these phenomena has also been reflected in academia, where studies on VEG have flourished in the last decade [7]. In this regard, VEG has rapidly expanded from philosophical and medical disciplines to other areas related to psychology, consumer behavior, and behavioral science [22]. One of the reasons for the increase in this research is related to the fact that, although VEG is seen as a promising avenue that brings a more ethical, sustainable, and healthier society, such a lifestyle transition is also seen as a challenge [23,24].

This extraordinary progression of scientific knowledge makes it advisable to know the current trends to map and have an overview of VEG research. Previous narrative literature reviews [11,22,25] have been of great relevance for this and have illuminated the way for researchers, practitioners, and public actors. However, owing to the increasing number of studies published in the last decade, it is highly recommended to update the knowledge and have a holistic view of the VEG literature. To achieve this, the most appropriate methodology is a systematic literature review [26,27]. This logic has been recently used to analyze the aspect of identity in veganism [28].

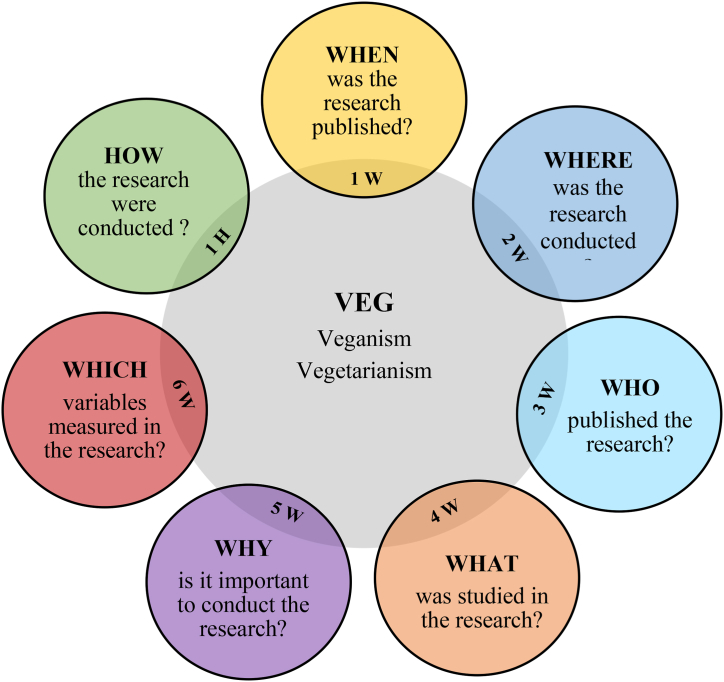

In this study, we conducted a systematic literature review in the VEG field to extend, complete, and update previous literature reviews. Specifically, our work principally focused on reviewing the quantitative studies in psychology, behavioral science, social science, and consumer behavior literature published in scientific journals from 1978 up to December 31, 2022, on VEG. A successful systematic literature review relies on straightforward research questions provided at the beginning of the process [27]; therefore, we articulated our objectives using the 5W1H [29], which explores a phenomenon from multiple perspectives based on the following questions: (1 W) “WHEN” refers to the period of the analysis and possible trends in VEG research; (2 W) “WHERE” focuses on the countries in which VEG studies have been conducted; (3 W) “WHO” refers to the journals in which VEG studies have been published; (4 W) “WHAT” refers to the different research streams and frames included in the VEG body of research; (5 W) “WHY” includes the reasons (environmental, health, or animals) that made VEG an essential topic for scholars to study; and (1H) “HOW” focuses on reviewing the different research methodologies and statistical analyses employed in the literature on VEG. Additionally, we added another question, “WHICH,” comprising the variables measured in the studies. Thus, we followed a 6W1H approach (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

6 W & 1H approach applied to VEG literature.

This study contributes to the existing literature on VEG by mapping the state of the art, identifying trends and gaps in research, clarifying existing findings, and suggesting directions for future research. Our systematic literature review also highlighted the factors examined in VEG and the variables associated with VEG-related behavior change, thus playing an important role in advancing research on VEG. For practitioners, our study will help elucidate possible interventions and design more effective (marketing) campaigns to improve and promote the transition to VEG. Additionally, these interventions may be beneficial for private organizations and public authorities seeking to design policies to encourage fairer and more sustainable consumption and healthier lifestyles.

This article is organized as follows: In Section 2, we outline the methodology. Next, we present the results of our analysis, which was performed using the 6W1H approach. In Section 4, we discuss the main findings and future avenues of research. Finally, in Section 5, we highlight the main contributions and managerial implications of the study.

2. Methods

The systematic search included articles up to December 31, 2022. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines were used for reporting the methods of this systematic literature review [30]. The systematic literature review protocol included the following steps: (1) search strategy; (2) inclusion, exclusion, and selection criteria; and (3) data extraction.

2.1. Search strategy

The first step of conducting the systematic literature review was keyword design. Following the backward and forward search methods [27], we created a pool of terms related to VEG literature that represented the main objectives of the review and were included in the previous reviews [11,22]. Additionally, we screened through the preliminary keyword results in several non-medical articles that focused on VEG. The resulting keyword syntax designed was: title, abstract, and keywords = [(vegan* OR vegetarian* OR plant-based*)] AND [(diet* OR food* OR lifestyle* OR movement* OR activism*) OR (eat* OR choos* OR choice* OR behavio* OR chang* OR purchas* OR buy* OR pay* OR cosnum* OR substitut* OR lik* OR familiar* OR reject* OR avoid* OR accept* OR restrict* OR disgust* OR information*) OR (motiv* OR reason* OR attitude* OR intention* OR willing* OR belief* OR perception* OR value* OR identity* OR emotion* OR empathy* OR norm* OR social* OR knowledge* OR familiarity* OR gender*)].

We used Web of Science (WoS) for our search. WoS was preferred to other databases because it is the world's leading scientific citation search engine and the most widely used research database [31,32]. WoS has guaranteed scientific content, strict filtering, and anti-manipulation policies, and offers many resources for searching and collecting metadata [[33], [34], [35], [36]]. In addition, WoS focuses on Social Sciences and Humanities (and less on Health Sciences) [37], which is more in line with the objectives of our study and covered all major journals relevant to our topic. However, it is worth mentioning that the final number of articles included in our systematic literature review resulted from reviewing the reference list of studies retrieved through WoS.

2.2. Inclusion, exclusion, and selection criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion criteria

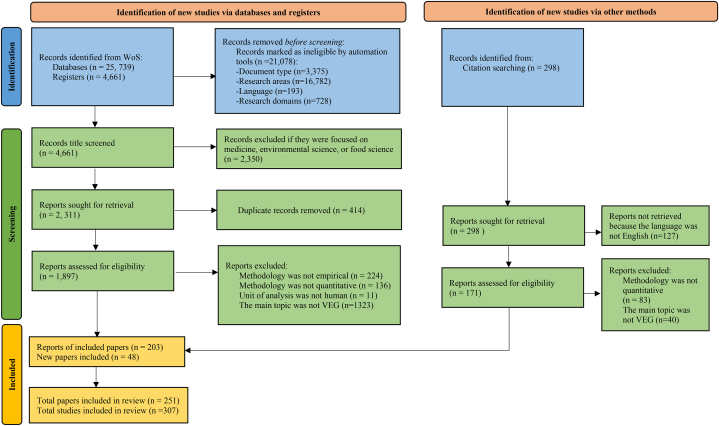

The systematic search included articles up to December 31, 2022. During the initial search, 25,739 articles were identified through their titles, abstracts, and keywords (Fig. 2). Once the articles were identified, we filtered the results following the inclusion criteria based on the following: (1) discipline: we included articles related to behavioral science, psychology, sociology, and business economics; (2) document type: we included only peer-reviewed articles; and (3) language: we only included articles written in English to ensure consistency and comparability of terms across the included studies. This was especially important as VEG is a recently emerging multi-disciplinary area.

Fig. 2.

PRISMA Flow diagram of the systematic literature review of quantitative VEG studies [30].

2.2.2. Exclusion criteria

Initially selected articles were removed based on the following: (1) research area: if their key focus was not on behavioral and psychological aspects of VEG. Thus, articles concerning medical issues (e.g., nutritional status or diseases), specific environmental problems (e.g., gas emissions or water), and technological challenges of food science (e.g., the chemical process of producing vegan products) were not included; (2) unit of analysis: studies with units of analysis different from individuals or households were excluded; and (3) methodology: we excluded qualitative studies. This decision was made because qualitative and quantitative approaches differ not only in their research techniques but, more importantly, in the ontological and epistemological perspectives they adopt [38]. Thus, we considered that separating quantitative from qualitative studies was advisable to gain a deeper knowledge on the issue. We focused on quantitative studies because there has been a more pronounced growth of quantitative studies and a greater interest in statistically measuring the factors that explain the adoption (or rejection) of VEG lifestyles. The selection protocol had no restrictions on sample characteristics (country and sex) and study setting (laboratory or restaurant).

This step left 203 articles for a full manuscript review. Finally, the reference list of articles was also reviewed, and 48 qualifying articles were added to the sample for data extraction. A total of 251 articles (307 studies, given that some articles included several studies) were recognized for data extraction. Initial screening for eligibility was performed by the three authors, each of whom reviewed one-third of the articles through the abstracts. To ensure consistency in the selection process, 5% of the articles were randomly assigned to a different author to perform an inter-reviewer reliability test [39,40]. The results indicated excellent agreement in this first step, as 96.5% of the articles were equally identified by the reviewers, and Cohen's kappa was 0.91.

2.3. Data extraction

A coding template was designed in Excel to extract specific data to answer the 6W1H questions. Information on WHEN (year of publication), WHERE (country of the sample), and WHO (journals) was coded directly. The coding of WHAT was more complicated; therefore, we designed a coding protocol to perform a preliminary content analysis of the data following the recommendations of Welch and Bjorkman [41]. We initially started pilot coding 30 articles, considering two main research streams: veganism (Vgn) and vegetarianism (Vgt). The coding of these research streams was based on the provided definitions of VEG and explained earlier. In this understanding, some scholars addressed their objective on vegetarianism (Vgt) and considered veganism (Vgn) as a sub-category of vegetarianism (Vgt). In these studies, we coded the stream as Vgt-Vgn. It should be noted that some studies also used the term “plant-based” in their studies; however, when reviewing the work, we observed that the authors used that term as a synonym for vegetarianism, veganism, or both. Therefore, following the same approach for vegetarianism, we coded these studies in the corresponding group of currents. In the second round of coding, we identified that veganism and vegetarianism were also studied simultaneously (Vgt-Vgn) as well as with other phenomena: meat consumption, animal-human relationship, and cultured meat consumption; we called these three new streams secondary streams. In total, coding was performed with seven streams.

To provide more nuanced information concerning WHAT, a further coding step was conducted to reclassify the studies not only concerning the streams but also the following three frames: (1) food, referring to specific products; (2) diet, referring to dietary practices; and (3) philosophy of life, referring to a social movement and lifestyle, focusing on the characteristics of the person consuming VEG products or following a VEG diet or philosophy of life. As mentioned previously, sometimes, these three frames were analyzed in combination (e.g., food and diet). Overall, five research frames were identified. To ensure the decision in coding, each article was scanned for keywords using an agreed a priori system. The manuscripts were also re-checked, ensuring accuracy and agreement, and differences were discussed with the third researcher to reach inter-coding agreement, which provided a measure of consistency.

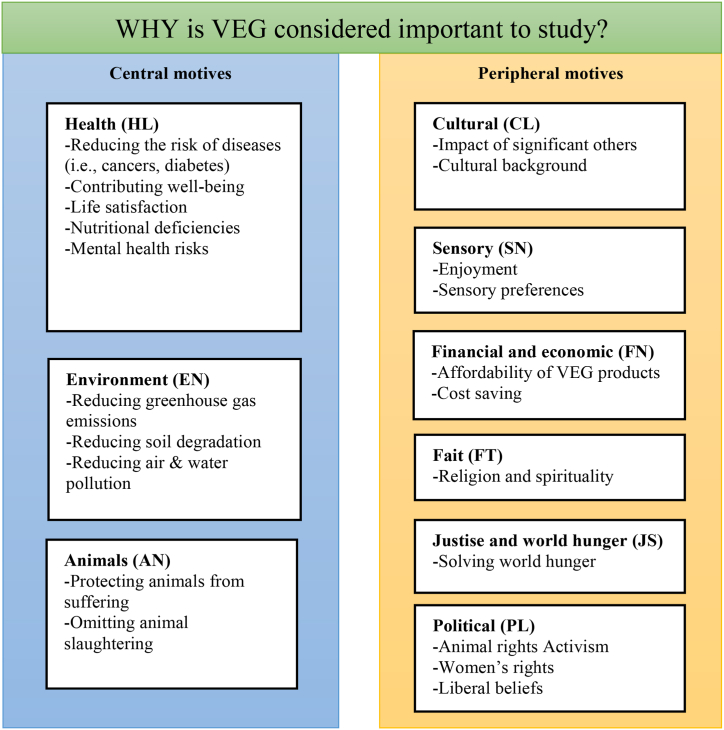

For WHY, we were interested in coding the reasons that scholars considered VEG as an important subject to be studied. Reasons from existing literature were classified into two broad categories: central and peripheral reasons. Central reasons included health issues, concern for animals, and environmental sustainability. Peripheral reasons comprised justice and world hunger; faith, religion, and spirituality concerns; sensory factors; cultural and social aspects; financial and economic aspects; and political concerns.

WHICH aimed to explore the variables measured in the VEG studies (attitudes or values). Finally, for HOW, we collected information contained in the methodology section of the articles regarding the type of study, sample, and statistical techniques. Thus, we collected information regarding the unit of analysis (individuals vs. objects), type of data (longitudinal vs. cross-sectional), data sources (secondary vs. primary), number of data sources, data collection methods (archival data, or surveys), and the year of data collection. Information on the sample comprised the size, country, mean age, percentage of female participants, racial or ethnic origin of respondents, and VEG orientation of respondents (vegetarian or vegan). Additionally, we checked whether the sample was representative of the corresponding general population. Subsequently, the studies were classified into non-experimental or correlational or experimental (choice experiment, or within-subject and between-subjects).

We also collected information regarding the dependent and independent variables, number of constructs, and the theoretical frameworks and scales used to measure them (especially if the scale used was designed ad hoc to study the VEG phenomenon). Finally, regarding the statistical techniques, we compiled information about the analyses and techniques used (e.g., t-tests, correlation tests, ANOVA, MANOVA, regressions, SEM, and latent class analysis). We also checked for the use of normality tests (if required), scale validation, moderation, and mediation tests, as well as whether the study was aware of the possible threat of common method effects (if required), social desirability, or other potential biases. The criteria for coding HOW included the guidelines of the Effective Public Health Practice Project.

3. Results

3.1. WHEN were the VEG studies conducted?

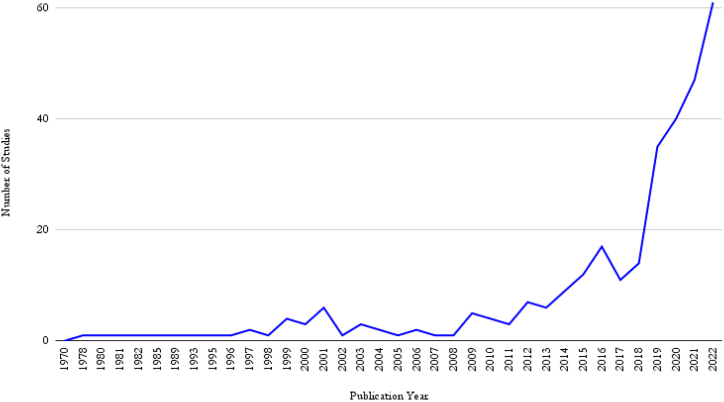

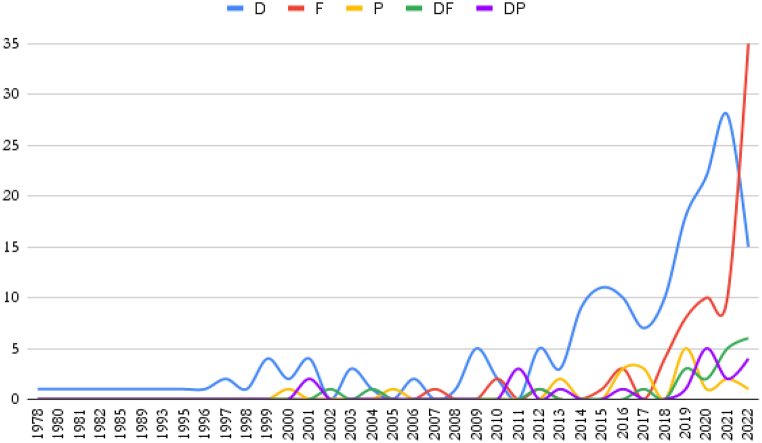

The final 307 studies covered a period from 1978 to December 31, 2022. The characteristics of the studies are summarized in Table 8 in Annex. Eighty-four percent of the studies included in this review were published in the last ten years (see Fig. 3). The findings provide reasonable evidence that academic interest in VEG research has grown exponentially. Exploring the evolution in more detail, we observed three peaks in the number of publications. First, in 1999 the number of publications per year increased from one to four; second, in 2015, the number of publications increased again to approximately more than ten articles per year. Finally, the most significant evolution occurred in 2019, when the number of publications doubled (from 14 to 35). The trend also grew steadily until 2021; in 2022, this number increased to 61 studies. Most of the publications in 2021 were related to the special issue of Appetite journal, titled “The psychology of meat-eating and vegetarianism.”

Fig. 3.

Count of VEG topic studies published from 1978 up to December 31, 2022.

3.2. WHERE were the VEG studies conducted?

In terms of regional concentration, research was focused on developed countries, mainly in the US (33%), the UK (10%), Germany (6.5%), Australia (3.5%), Canada (3.3%), and Spain (3.3%). It should be noted that many studies (12%) included data from more than one country, but these international samples were mainly from the US and the UK. A simultaneous analysis of WHEN (publication year) and WHERE (country) also showed that the pioneer countries were the US, UK, Australia, and Canada. Other countries’ quantitative inquiries on VEG started in 2000 by studies in New Zealand, Finland, and the Netherlands. Geographical orientations became more widespread from 2015 onward (Table 1).

Table 1.

Simultaneous analysis of WHERE and WHEN.

| Country of data | Publication year of each study |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum | 1978 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1985 | 1989 | 1993 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| USA | 101 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 12 | 16 | 7 | 13 | |||||||||||

| International | 35 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 11 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UK | 31 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 10 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Germany | 20 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Australia | 11 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spain | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Canada | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Finland | 9 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| New Zealand | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| France | 7 | 4 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Italy | 7 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| China | 7 | 1 | 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Switzerland | 6 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Portugal | 6 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Netherlands | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Belgium | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Austria | 3 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Denmark | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poland | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turkey | 3 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Taiwan | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brazil | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chile | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sweden | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Argentina | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ireland | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Norway | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Croatia | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Slovenia | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Malaysia | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnam | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korea | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sum | 307 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 17 | 11 | 14 | 35 | 40 | 47 | 61 |

3.3. WHO published the VEG studies?

The reviewed articles were published in 92 different journals (Table 2). Regarding the number of articles published in each journal, the relevance of Appetite was evident, with 21.8% of all articles reviewed published in this journal. This was followed by Food Quality and Preference (6.8%), Sustainability (4%), and British Food Journal (3%).

Table 2.

Journals and their research areas.

| Research Areas | Papers | Journal Name |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Sciences & Nutrition-Dietetics | 124 | Appetite; Food Quality and Preference; Sustainability; British Food Journal; Foods; Future Foods, Plos One; International Journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity |

| Behavioral Science & Public health | 42 | Nutrition & Food Science; Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; Applied Research in Quality of life; Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition; European journal of clinical nutrition; Complementary Medicine Research; Obesity science & practice; Ecology of food and nutrition; Journal of nutrition education and behavior; Journal of the American Dietetic Association; Florida Public Health Review; Nutrients; Public health nutrition; Journal of Adolescent Health; Journal of Biological Education; Frontiers in Nutrition; Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine; Health Education Journal; Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; Nutrition Research; bmc public health; Research in Veterinary science; International Journal of environmental research and public health |

| Psychology | 28 | Group Processes & Intergroup Relations; The Journal of social psychology; Basic and Applied Social Psychology; The Psychological Record; European Journal of Social Psychology; Stigma and Health; Psychosomatics; International Journal of; Psychology; Personality and Individual Differences; Eating behaviors; International journal of social psychology; Journal of affective disorders; Motivation and Emotion; Social Psychological and Personality Science; Psychology of Men & Masculinity; Social Psychology; Psychological Science; Frontiers in psychology; Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society; Journal of environmental psychology; Journal of health psychology; Health psychology and behavioral medicine |

| Business & Economics (Consumer behavior) | 21 | Ernahrungs Umschau; Journal of food products marketing; Journal of Managerial Issues; Journal of consumer ethics; American journal of agricultural economics; International Journal of Consumer Studies; Amfiteatru Economic; Psychology & Marketing; Ecological Economics; International Journal of Consumer Studies; Journal of retailing and consumer services; Journal of Marketing Communications; Data in brief; Applied economics perspectives and policy; International journal of hospitality management |

| Sociology & Anthroprology | 19 | Social Development; Social justice research; Social Choice and Welfare; Society & Animals; Rural Sociology; Anthrozoös; Collegium Antropologicum; Journal of Contemporary Religion; Political Studies; Animals; Fat studies; Societies |

| Behavioral Science & Food-Technology | 17 | Food policy; Food Research International; Futures; Scientific Reports; Agriculture and agricultural science procedia; Food Hydrocolloids; Online Information Review; Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions; Sustainable Production and Consumption; Environmental Communication; Journal of food science; Livestock Science; Agricultural and food economics |

| Sum | 251 |

3.4. WHAT has been studied in VEG research?

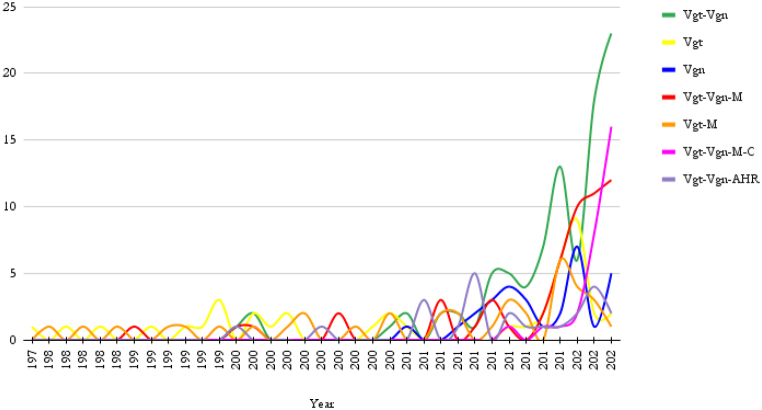

3.4.1. Streams of VEG

As it is shown in Table 3, we discerned the following seven streams: vegetarianism and veganism (Vgt-Vgn); vegetarianism (Vgt); veganism (Vgn); vegetarianism, veganism, and meat consumption (Vgt-Vgn-M); vegetarianism and meat consumption (Vgt-M); vegetarianism, veganism, meat consumption, and cultured meat consumption (Vgt-Vgn-M-C); and vegetarianism, veganism, animal-human relationship (Vgt-Vgn-AHR). The research mainly focused on Vgt-Vgn (30%), Vgt-Vgn-M (17.6%), Vgt (13%), and Vgt-M (12%).

Table 3.

WHAT streams have emerged in the VEG quantitative studies?a.

| STREAMS | Studies | References |

|---|---|---|

| PRINCIPAL | ||

| Vgt-Vgn | 92 | Allen et al. [42.I]; Arenas-Gaitán et al. [8], Aschemann-Witzel & Peschel [43]; Bagci & Olgun [18]; Boaitey & Minegishi [44]; Bobić et al. [45]; Brandner et al. [46]; Braunsberger et al. [47]; Brouwer et al. [48]; Bryant [49]; Cardello et al., [50]; Chung et al. [51]; Clark & Bogdan [20]; Cliceri et al. [3,52]; Cramer et al. [53]; Crnic [54]; Estell et al. [55]; Falkeisen et al. [56]; Feltz et al. [57]; Ghaffari et al. [58]; Gili et al. [59]; Graça et al. [60.II, 61]; Haas et al. [62]; Hibbeln et al. [63]; Hoffman et al. [64]; Isham et al. [65]; Judge & Wilson [66,67]; Kessler et al. [68,69]; Krizanova et al. [70]; Krizanova & Guardiola [71]; Larsson et al. [72]; Ma & Chang [73]; MacInnis & Hodson [74,75]; Montesdeoca et al. [76]; Moore et al. [77]; Moss et al. [78]; Müssig et al. [79]; Nguyen et al. [80]; Nocella et al. [81]; Noguerol et al. [82]; Norwood et al. [83]; Palnau et al. [84]; Paslakis et al. [85]; Pechey et al. [86]; Pfeiler & Egloff [87]; Ploll et al. [88]; Pointke et al. [89]; Pribis et al. [90]; Reuber & Muschalla [91]; Rondoni et al. [92]; Rosenfeld [93,94]; Rothgerber [95,96]; Ruehlman & Karoly [97]; Siebertz et al. [98]; Spencer et al. [99]; Tan et al. [17]; Taufik et al. [6]; Thomas [100]; Valdez et al. [101]; Valdes et al. [102]; Vergeer et al. [103]; Veser et al. [104]; Villette et al. [105]; Vizcaino et al. [106]; Wang et al. [10]; Weiper & Vonk [107]; Wyker & Davison [108] |

| Vgt | 41 | Back & Glasgow [109]; Bacon & Krpan [110]; Barnes-Holmes et al. [111]; Barr & Chapman [112]; Cooper et al. [113]; Dietz et al. [114]; Hargreaves et al. [115]; Hopwood et al. [116]; Janda & Trocchia [117]; Kalof et al. [118]; Kim et al. [119]; Lea & Worsley [120,121]; Lindeman & Sirelius [122]; Lusk & Norwood [123]; Mohamed et al. [124]; Parkin & Attwood [125]; Piester et al. [126]; Plante et al. [127]; Preylo & Arikawa [128]; Rosenfeld [129.I, 130]; Rosenfeld & Tomiyama [131]; Rosenfeld et al. [132]; Schenk et al. [133]; Segovia-Siapco et al. [12]; Sims [134]; Stockburger et al. [135]; Thomas et al. [136]; Tian et al. [137]; Vinnari et al. [138]; White et al. [139]; Worsley & Skrzypiec [140,141]; Zhang et al. [142] |

| Vgn | 30 | Adise et al. [143]; Braunsberger & Flamm [19]; Bresnahan et al. [144]; Crimarco et al. [145]; De Groeve et al. [146]; Dyett et al. [147]; Eckart et al. [148]; Heiss et al. [149,150]; Janssen et al. [151]; Judge et al. [9]; Kalte [152,153]; Kerschke-Risch [154]; Mace & McCulloch [155]; Marangon et al. [156]; Miguel et al. [157]; Phua et al. [158,159]; Radnitz et al. [160]; Raggiotto et al. [161]; Rothgerber [162]; Stremmel et al. [163]; Wrenn [164,165] |

| SECONDARY | ||

| Vgt-Vgn-M | 54 | Allen et al. [42.II]; Amato et al. [166]; Anderson et al. [167]; Asher & Peters [2,13]; Bagci et al. [168]; Davitt et al. [169]; De Groeve et al. [14]; Duchene & Jackson [170]; Faber et al. [171]; Falkeisen et al. [56.II]; Faria & Kang [172]; Feltz et al. [57]; Forestell et al. [173]; Graça et al. [60.I]; Grassian [174]; Grünhage & Reuter [175]; Hagmann et al. [176]; Haverstock & Forgays [177]; Hinrichs et al. [178]; Kirsten et al. [179]; Lea et al. [180,181]; Lim et al. [182]; Mann & Necula [183]; Migliavada et al. [184]; Montesdeoca et al. [76]; Neale et al. [185]; Nykänen et al. [186]; Papies et al. [187.1 l&lll]; Pechey et al. [188]; Perry et al. [1]; Pohojolanian et al. [189]; Povey et al. [190]; Profeta et al. [191]; Rabès et al. [192]; Reipurth et al. [193]; Rothgerber [194]; Schobin et al. [5]; Sharps et al. [195]; Sucapane et al. [196]; Timko et al. [197.l]; Tonsor et al. [198. Ll,lll,lV]; Trethewey & Jackson [199]; Urbanovich & Bevan [200]; Vainio [201]; Vainio et al. [202,203]; Waters [204]; Zur & Klöckner [205] |

| Vgt-M | 37 | Apostolidis & McLeay [21]; Beardsworth & Bryman [206,207]; Besson et al. [208]; De Houwer & De Bruycker [209]; Earle & Hodson [23]; Fessler et al. [210]; Giacoman et al. [211]; Giraldo et al. [212]; Graça et al. [213]; Hoek et al. [214]; Hussar & Harris [215]; Lindeman & Sirelius [122. II]; Lourenco et al. [24]; Mullee et al. [216]; Neuman et al. [217]; Patel & Buckland [218]; Rosenfeld [129.II]; Rosenfeld & Tomiyama [219]; Rosenfeld et al. [220]; Rothgerber [221]; Rozin & Fallon [222]; Rozin et al. [223]; Ruby et al. [224]; Santos & Booth [225]; Schösler et al. [226,227]; Shickle et al. [228]; Siegrist & Hartmann [4]; Timko et al. [197]; Vandermoere et al. [229]; Weinstein & de Man [230] |

| Vgt-Vgn-M-C | 29 | Apostolidis & McLeay [231]; Bryant & Sanctorum [232]; Carlsson et al. [233]; Chen et al. [234]; de Visser et al. [235]; Gómez-Luciano et al. [236]; Gousset et al. [237]; Jang & Cho [238]; Katare et al. [239]; Li et al. [240]; Marcus et al. [241]; Martinelli & De Canio [242]; Michel et al. [243,244]; Milfont et al. [245]; Ortega et al. [246]; Oven et al. [247]; Pais et al. [248]; Profeta et al. [249,250]; Slade [251]; Tonsor et al. [198.I]; Van Loo et al. [252]; Ye & Mattila [253] |

| Vgt-Vgn-AHR | 24 | Bilewicz et al. [254]; D'Souza et al. [7]; Díaz [15,255]; Dodd et al. [256,257]; Espinosa & Treich [258,259]; Fiestas-Flores & Pyhälä [260]; Hamilton [261]; Hielkema & Lund [262]; Knight & Satchell [263]; Lund et al. [264]; Phillips & McCulloch [265]; Ploll & Stern [266]; Pohlmann [267]; Rothgerber [268,269] |

| Sum | 307 | |

Vgt: Vegetarianism; Vgn: Veganism; M: Meat consumption; AHR: Animal-Human relationship; C: Cultured meat consumption.

To differentiate between the various studies that are presented in certain papers, we have adopted the convention of utilizing Latin numerals, which are enclosed within square brackets after the reference numbers. By way of illustration, to cite the first study reported in Allen et al.'s [42] paper, we have used the notation Allen et al. [42. I].

By simultaneously analyzing WHAT (streams) and WHEN (publication years), we noticed that the first quantitative study on the Vgn stream was conducted in 2010 (Fig. 4). Academic interest in Vgn research grew steadily, except for a decline in 2018. However, Vgt studies started decades earlier, in 1981. The Vgt stream was the pioneer in the quantitative approach of VEG, but this trend was not continuous; we observed a gap from 2010 to 2016 in the Vgt stream. Interestingly, in 2020 there was a peak in research focused on Vgn and Vgt streams. Finally, we observed an evolutionary increase of studies in the Vgt-Vgn-M-C stream.

Fig. 4.

When and what (streams).

3.4.2. Frames of VEG

By analyzing the different conceptualizations of VEG in research, we observed that 56% of studies framed it as diet, 24% as consumption of VEG food products, and 6% as the philosophy of life. Some studies also considered VEG as a combination of two frames: diet and consumption of VEG food products (6.5%) and diet and philosophy of life (6%). To get a more accurate picture of the focus of researchers, we crossed the streams with the frames of VEG. As shown in Table 4, framing the VEG phenomenon as diet was more present in Vgt stream (70.7%), followed by Vgt-Vgn-M (68.5%) and Vgt-M (67%) streams. Expectedly, framing VEG as food was more prevalent in Vgt-Vgn-M-C (79%). Through the simultaneous evaluation of seven streams and five frames, we found a total of 35 distinct research categories on VEG. This analysis showed that 19.5% of studies focused on Vgt-Vgn. D stream, followed by Vgt-Vgn-M.D (12%), Vgt-D (9%), and Vgt-M. D (8%). It is noteworthy to mention that in four research categories (Vgt-Vgn-M.P, Vgt-Vgn-M.DP, Vgt-Vgn-M-C.P, and Vgt-Vgn-AHR.DF), we did not find any published articles.

Table 4.

VEG has been studied in WHAT frames through the streams?

| STREAMS | Frames |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum | D | F | P | DF | DP | |

| PRINCIPAL | ||||||

| Vgt-Vgn | 92 | 60 | 20 | 4 | 6 | 2 |

| Vgt | 41 | 29 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Vgn | 30 | 11 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 6 |

| SECONDARY | ||||||

| Vgt-Vgn-M | 54 | 37 | 15 | 2 | ||

| Vgt-M | 37 | 25 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Vgt-Vgn-M-C | 29 | 1 | 23 | 4 | 1 | |

| Vgt-Vgn-AHR | 24 | 11 | 1 | 4 | 8 | |

| SUM | 307 | 174 | 75 | 19 | 20 | 19 |

Vgt: Vegetarianism; Vgn: Veganism; M: Meat consumption; AHR: Animal-Human relationship; C: Cultured meat consumption; D: Diet; F: Food; P: Philosophy of life.

The publication of five VEG research frames over the years is shown in Fig. 5. Studying VEG through the diet frame increased over the years, with peaks in 2021 (28 studies) and 2015 (11 studies). However, this interest decreased to 15 studies in 2022. By contrast, there was a relatively high number of studies analyzing VEG in the food consumption frame, with two peaks in 2022 (35 studies) and 2020 (10 studies). It is worth noting that the number of studies in other frames was relatively small and did not seem to follow any temporal pattern.

Fig. 5.

When and what (frames).

3.5. WHY have researchers found it relevant to study VEG?

In Section 2.3, we undertook a classification of the relevance of studying the VEG phenomenon as cited in the reviewed articles. Our analysis yielded two distinct groups: central and peripheral reasons. The former comprised concerns related to health, environmental issues, and animal welfare. The latter encompassed a diverse range of additional factors, including cultural and social considerations, sensory preferences, faith, financial and economic implications, political concerns, and world hunger. For clarity, we will discuss these nine motives below according to the order of importance in which they appear in the reviewed studies (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

WHY it is important to study VEG.

3.5.1. Central motives

Among the reasons identified in the studies to justify the importance of studying VEG, health concerns (83%) had the highest presence. Exploring this further, we found that many articles referred to the health aspect of VEG as the respondents’ motivation [42,143]. Some authors explained the positive effect of VEG on the human body by mentioning specific benefits, such as reducing cholesterol, blood pressure, or risk of diabetes, as well as reducing the incidence of cancers, heart disease, and hypertension [2,3,63,144]. More recently, a body of research interested in a more holistic view of health considered VEG options as an essential contributor to well-being and quality of life [8,53,115]. However, a minority referred to the potential adverse physical health effects, such as nutritional deficiencies (vitamin B12, zinc, or iron) if a well-planned VEG diet is not followed [53], or mental health risks, such as risks of stigmatization, discrimination, or feelings of embitterment [48,91,168]. Simultaneous analysis of WHY and WHAT showed that health considerations were the most frequently cited concern across all streams. Notably, more articles focused on Vgn (93%) and Vgt-Vgn (89%). Table 5 summarizes the convergence of these motives in each stream.

Table 5.

WHY did scholars considered VEG important to be studied?

| REASONS | Sum | HL | EN | AN | CL | SN | FN | FT | PL | JS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRINCIPAL | ||||||||||

| Vgt-Vgn | 92 | 82 | 65 | 51 | 30 | 24 | 17 | 16 | 12 | 5 |

| Vgt | 41 | 34 | 29 | 26 | 17 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 1 | 7 |

| Vgn | 30 | 28 | 24 | 26 | 12 | 14 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 11 |

| SECONDARY | ||||||||||

| Vgt-Vgn-M | 54 | 44 | 47 | 31 | 17 | 17 | 13 | 8 | 9 | 5 |

| Vgt-M | 37 | 31 | 31 | 29 | 13 | 15 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 5 |

| Vgt-Vgn-M-C | 29 | 22 | 26 | 20 | 5 | 9 | 16 | 5 | 1 | 3 |

| Vgt-Vgn-AHR | 24 | 15 | 9 | 24 | 9 | 12 | 4 | 9 | 4 | |

| Sum | 307 | 256 | 231 | 207 | 103 | 103 | 77 | 70 | 38 | 36 |

Vgt: Vegetarianism; Vgn: Veganism; M: Meat consumption; AHR: Animal-Human relationship; C: Cultured meat consumption.

HL: Health; EN: Environment; AN: Animals; CL: Cultural & Social; SN: Sensory factors; FT: Fait; FN: Financial & economic; PL: Political; JS: Justice & world hunger.

In the reviewed literature, there was a significant presence of referring to the environmental benefits of VEG (75%). Diversity in arguments and approaches was also observed when analyzing the environmentalist discourse. Some authors emphasized specific impacts; for example, they discussed how replacing animal-based diets with VEG diets could help reduce greenhouse gas emissions [9,60,67] and soil degradation [19,62,66], and tackle current problems related to air, soil, and water pollution [214], biodiversity loss [62], as well as climate change [61]. Nevertheless, most studies addressed the environmental benefits of VEG quite loosely, using terms such as a “sustainable” strategy [183] or alternatives to lessen the impacts of the current animal agriculture. Similarly, some authors mentioned that VEG alternatives comply with the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. However, the terms “vegan” or “vegetarian” are absent in these goals [8]. Analyzing the frequency of environmental concerns among different streams indicated that environmental issues were the most frequently cited concern in the Vgt-Vgn-M-C stream with a prevalence of 89.6%, followed by 87% in the Vgt-Vgn-M stream and 83% in the Vgt-M stream. This suggests that environmental issues may have a significant role in encouraging studies transitioning from meat consumption to cultured meat consumption.

Approximately two-thirds of the reviewed studies (67%) included varied arguments on animal-related concerns. In some instances, animal-related concerns were considered a central aspect of VEG discourse, while in others, they were only tangentially referenced. References to animal concerns appeared implicit and subsumed under the general term of “ethical” [64,170] or “moral” reasons [117,212]. Conversely, in other instances, the phenomenon of VEG appeared firmly rooted in the animal rights or animal protection movement [255]. Another example of these differences was found when researchers discussed the drivers of following, adopting, or consuming VEG options. For example, some researchers emphasized the positive aspects of VEG for animals; we found references to “compassion toward animals” [54], “animal advocacy” [258], “affection toward animals” [255], or “animal welfare” [243,263]. In contrast, other researchers highlighted the detrimental effects of the current animal agriculture on animals and how VEG alleviates this negative impact. These studies often used expressions such as “animal suffering” [117], “animal exploitation” [260], or “animal slaughter” [81].

Notably, we also found diverse philosophical approaches adopted in the studies to defend VEG. Some research aligned strongly with welfarist positions [114,145,215], while others aligned with abolitionist or animal rights perspectives [60,116,256]; to a lesser extent, anti-speciesism discourses were also incorporated [15]. The presence of animal concerns significantly depended on the stream. Expectedly, in the Vgt-Vgn-AHR stream, animal considerations were found in all of the studies, followed by 86% in the Vgn stream.

3.5.2. Peripheral motives

In this category, distinguished three sub-groups according to the relevance with which they appeared in the reviewed research. In the first sub-group, we found cultural and social, and sensory motives, each present in 33% of the studies. Cultural and social factors included the influence exerted by certain people or groups on an individual's decisions about their VEG choices. Specifically, studies focused on analyzing the impact of people's close networks, mainly families or peers [21], and online vegan discussion groups [19]. Cultural and social factors were mainly observed in the Vgt stream (41%).

For sensory reasons we referred to consumer or producer concerns about the sensory aspects of VEG alternatives, which are typically related to VEG foods (i.e., taste, texture, odor, or appearance) [99,117,143]. Sensory reasons were primarily observed in the Vgt-Vgn-AHR (50%) and Vgn (46%) streams.

In the second place, we found references to financial and economic, and faith reasons, present in 25% and 22% of the articles, respectively. VEG studies citing financial and economic reasons were relatively scarce. These typically covered cost savings from the consumer's perspective [174]. These concerns were primarily mentioned in the studies on the Vgt-Vgn-M-C stream (72%), which was expected owing to the growing market of VEG products. Faith motives included both religious [109,231] and spiritual beliefs [45]. Generally, these reasons were typically studied as drivers of VEG choices [68,100]; however, these concepts require further exploration. Faith reasons appeared mainly in the Vgt-Vgn-AHR stream (37%).

Finally, we found that political, and justice and world hunger arguments [130,153] had a much lower presence in the studies; specifically, they were each mentioned in only 12% of the articles. Political aspect of the VEG referred to connections to other social movements and other political issues beyond animal protection; in this sense, we found references to claims for women's or LGBTQ rights [258]. In most cases, these political issues were neither defined nor explained in depth. Political motives were primarily observed in the Vgn (20%) and Vgt-Vgn-AHR (16%) streams. Justice and world hunger concerns referred to the world hunger problem [13,205] and various arguments on how VEG can improve food availability or exacerbate social inequality and injustices [161,164]. However, these arguments require more specificity and detail. They were mainly explored in Vgn studies (36%). In general, we observed that 50% of studies were commonly mentioned in HL-EN-AN (Table 8 in Annex).

3.6. WHICH variables were analyzed in VEG studies?

Before proceeding to a detailed study of the variables examined in the literature, it should be noted that only 29.6% of the studies used theoretical frameworks to measure the variables under examination. In this group of studies, we found that 33.7% used the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [270]; 8.6% of the studies used the Unified Model of Vegetarian Identity [271]; 7.6% applied human values theory [272]; 7.6% employed the Transtheoretical Model [273], and 4% used Social Dominance Orientation [274]. The usage of these theories across the seven streams of studies is summarized in Table 6. It is worth noting that approximately 11% of the reviewed studies applied other theoretical frameworks than the five most prevalent ones.

Table 6.

Most extensively researched theories in each stream of VEG studies.

| STREAMS/THEORIES | Theory of planned behavior (TPB) [270] | Unified Model of Vegetarian Identity (UMVI) [271] | Human values [271] | Transtheoretical model (TM) [273] | Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) [274] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRINCIPAL | |||||

| Vgt-Vgn | Clark & Bogdan [20]; Chung et al. [51]; Graça et al. [60]; Nocella et al. [81]; Wyker & Davison [108] | Montesdeoca et al. [76]; Reuber & Muschalla [91]; Rosenfeld [93] | Wyker & Davison [108] | Allen et al. [42]; Braunsberger et al. [47]; Veser et al. [104] | |

| Vgt | Janda & Trocchia [117] | Plante et al. [127]; Rosenfeld [129,130]; Rosenfeld et al. [132] | Dietz et al., [114]; Kalof et al. [118]; Lindeman & Sirelius [122] | Lea & Worsley [120] | |

| Vgn | Phua et al. [158,159] | Braunsberger & Flamm [19] | |||

| SECONDARY | |||||

| Vgt-M | Rosenfeld [129. II]; Rosenfeld et al. [220] | Lindeman & Sirelius [122] | Lourenco et al. [24] | ||

| Vgt-Vgn-M | Asher & Peters [2,13]; Graça et al. [60]; Lim et al. [182]; Povey et al. [190]; Urbanovich & Bevan [200]; Zur & Klöckner [205] | Amato et al. [166]; Bagci et al. (2021); Kirsten et al. [179]; Montesdeoca et al. [76] | Allen et al. [42]; Pohojolanian et al. [189]; Zur & Klöckner [205] | Asher & Peters [13]; Lea et al. [180]; Waters [204] | |

| Vgn-Vgt-M-C | Chen [234]; Marcus et al. [241] | Apostolidis & McLeay [231] | Milfont et al. [245] | ||

| Vgt-Vgn-AHR | D'Souza et al. [7]; Díaz [15,255]; Ploll & Stern [266] | Hielkema & Lund [262] | Bilewicz et al. [254] | ||

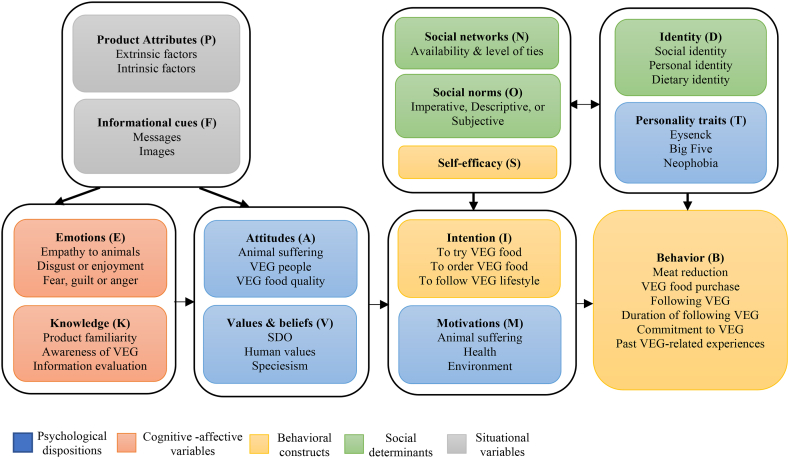

For the specific variables analyzed in the literature, we grouped them into five categories: psychological dispositions, cognitive-affective variables, behavioral constructs, social determinants, and situational variables. Table 7 summarizes the convergence of these variables and constructs in each stream; as illustrated, the prevalence of the variables depended on the stream in question, and in many of them, some variables were overlooked. For clarity, we analyzed each construct group according to the order of frequency in which the variables appeared in the studies.

Table 7.

WHICH variables has been measured in each stream of VEG quantitative studies?

| STREAMS | Sum | Psychological dispositions |

Cognitive-affective variables |

Behavioral constructs |

Social determinants |

Situational variables |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | M | V | T | E | K | B | I | S | N | D | O | P | F | ||

| PRINCIPAL | |||||||||||||||

| Vgt-Vgn | 92 | 57 | 34 | 23 | 18 | 20 | 14 | 63 | 19 | 10 | 13 | 9 | 7 | 20 | 16 |

| Vgt | 41 | 26 | 19 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 28 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 5 |

| Vgn | 30 | 17 | 16 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 23 | 10 | 3 | 13 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 10 |

| SECONDARY | |||||||||||||||

| Vgt-Vgn-M | 54 | 36 | 17 | 13 | 5 | 14 | 13 | 46 | 15 | 7 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 15 | 7 |

| Vgt-M | 37 | 26 | 19 | 6 | 4 | 12 | 8 | 28 | 6 | 11 | 2 | 7 | 5 | ||

| Vgt-Vgn-M-C | 29 | 23 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 18 | 19 | 3 | 2 | 16 | 9 | ||

| Vgt-Vgn-AHR | 24 | 21 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 15 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 7 |

| Sum | 307 | 206 | 121 | 66 | 38 | 73 | 53 | 221 | 77 | 26 | 62 | 36 | 26 | 70 | 59 |

Vgt: Vegetarianism; Vgn: Veganism; M: Meat consumption; AHR: Animal-Human relationship; C: Cultured meat consumption.

A: Attitudes; M: Motivations; V: Values, T: Personality; E: Emotions; K: Knowledge; B: Behavior; I: Intentions; S: Self-efficacy or Perceived Behavioral Control; N: Networks; O: Norms; D: Identity; P: Product Attributes; F: Information.

3.6.1. Psychological dispositions

Psychological dispositions included variables related to attitudes, motivations, values, and personality traits. Attitudes, understood as perceptions, and opinions on VEG-related issues, applied to different aspects and 67% of the studies measured attitudes. This variable was mainly constructed as attitudes toward animals [15,136,167], meat [137,141], and VEG lifestyles [54,108]. In addition, some studies measured attitudes in the context of justification strategies for non-VEG lifestyle choices [258]. Some authors differentiated between positive, negative, and neutral attitudes [23,49], but most studies did not make such distinctions and referred to attitudes as a uniform construct. Similarly, they did not differentiate between cognitive, affective, and conative aspects recognized in the consumer behavior literature [275]. Attitudes were primarily found in studies on Vgt-Vgn-AHR (87%), followed by those focusing on Vgt-Vgn-M-C (79%).

Regarding motivations, 39% of the reviewed studies were interested in studying the reasons that encouraged consumers to practice VEG (i.e., becoming a VEG, following a VEG diet, consuming VEG products). Particularly, studies focused on analyzing three types of motivations. First, studies with a strong hedonistic character, which were related to personal health, sensory appeals, and economic considerations [43]. Second, studies with a strong altruistic, ethical [8,151], or even spiritual character (e.g., Buddhism) on the adoption of VEG choices [68,261]. Here, authors differentiated between interest in animal protection (protecting animals from unnecessary suffering), environmental conservation (climate change and global warming), and human rights (the relationship between world hunger and the dedication of resources to livestock production rather than agriculture) [2,19,113,208]. Third, studies with a strong social character, in which we detected an interest in studying the effect of following VEG diets due to living with VEG family members or friends [53,114]. It is worth mentioning that some studies took a broader approach to motivations and studied them abstractly as a general concern to pursue their choice of VEG, but without delving into the type of motivation that affected the decision-making [13]. The interest in measuring motivations was observed, especially in studies on Vgn (53%), Vgt (46%), and Vgt-M (51%).

Values, understood guiding principles [42], were present in 21% of the studies. They were typically measured with extensively validated instruments, such as the Social Dominance Orientation scale [274], [e.g., 74, 104, 136,213], the Theory of Basic Human Values of Schwartz [271], [e.g., 114], or Altemeyer's Authoritarianism scale [276], [e.g., 67,74]. These studies concluded that the likelihood of practicing VEG was associated with greater endorsements of liberalism, universalism, and left-wing ideology [54,164,165]. As more specific values related to the VEG, we found speciesism measurement, understood as the belief in the supremacy of humans over animals [19,94,136,213]; in these cases, the use of the Dhont et al.‘s [277] speciesism scale stood out. Similarly, we found the measurement of carnism, namely, the belief system that supports the consumption of certain animals as food [132]; in this case, the variable was measured using Monteiro et al.‘s [278] scale. It should be mentioned that many scholars considered values as motivations (i.e., referring to religious reasons as religious values) [64]. Values were observed the most in the Vgt-Vgn-M stream (25%).

Our data also showed that 12% of studies focused on measuring personality traits [3,109]. These studies employed the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire [45,113], the Big Five test [69,84,87], and the Food Neophobia (reluctant to try or eat novel food) scale [52,172]. Personality traits were observed in the Vgt-Vgn stream (19.5%), followed by the Vgt stream (12%).

3.6.2. Cognitive-affective variables

Cognitive-affective variables referred to variables associated with the emotional responses to and knowledge regarding VEG. Regarding emotions, many scholars acknowledged that VEG lifestyles and choices were affectively charged [279,280]. Despite this recognition, emotions were only present in 23% of the studies in this field. The emotions associated with VEG lifestyle and choices included disgust (toward meat) [96], sensory (dis)liking VEG foods [96,143], guilt related to diet consistency or pet food choice [96,268], anger [144], shame [213], fear [74], and affect or empathy responses (the capacity to feel what others are experiencing) [3,15,47,136,194]. Most previous studies did not use validated instruments to measure these emotions. Notable exceptions were found in the assessment of meat disgust and meat enjoyment, which was mainly measured using the disgust scale [3] and the meat attachment questionnaire [84,213], respectively. Emotional concerns were more prevalent in the Vgt-Vgn-AHR (41%) and Vgt-M (32%) streams.

Knowledge was measured in 17% of studies and referred to the familiarity with VEG products [143,227], VEG diet [13,171], and the understanding of the relevance and impacts of VEG on health [103] and environment [202]. Knowledge was explored primarily in studies focused on Vgt-Vgn-M (24%).

3.6.3. Behavioral constructs

In the behavioral constructs, we observed behaviors, intentions, and self-efficacy. The measurement of behaviors was present in 72% of the reviewed studies, primarily involving self-reported food consumption habits [2,3,167]. In many cases, the inclusion of this construct was intended to complement and compare the self-reported status as vegan, vegetarian, or neither [2,167]. Most of these scales measured general food consumption behaviors. The Food Frequency Questionnaire [4,90], the Food Choice Questionnaire [131], and purchase frequency [8,183,251] were the most commonly used instruments to measure this variable. Notably, two articles advanced the measurement of behaviors using observational measurement via experimental designs [126,136]. Another pattern we observed in our review was the interest in the temporal aspect in which behaviors are performed. In this regard, although most studies focused on current consumption behaviors, some highlighted the relevance of past behaviors [110] and the duration for which individuals practiced VEG lifestyles [2,18,64,141,165,260]. Additionally, a few studies measured more than one behavior; as sometimes, all behaviors were directly related to food consumption. For example, Crimarco et al. [145] measured participants’ overall food consumption frequency, adherence to the vegan diet, and restaurant-related behaviors. In other studies, measured behaviors were related more to health, such as alcohol consumption [113] or adequate nutritional intake [192], and more rarely, to animal-related behaviors [128,256,268]. This variable appeared most frequently in the Vgt-Vgn-M (85%) and Vgn (76%) studies.

Intentions were included in 25% of the studies. In the reviewed articles, they were measured as the willingness to cut down on meat [205], try VEG foods [143], adopt a VEG lifestyle [190,226], being VEG [255], or continue practicing a VEG lifestyle in the future [2]. Some studies specified a time frame (e.g., next month, next two years) in their questions [49,255]. For example, in Wyker and Davison's [108] study, intention was measured by asking for agreement to the statement, “I intend to follow a plant-based diet in the next year.” To assess intentions, some studies applied the Transtheoretical Model [13,108], but primarily drew on TPB [13,15]. Among the different streams, measuring intention was predominant in the Vgt-Vgn-M-C (65%), Vgn (33%), and Vgt-Vgn-M (27%).

Self-efficacy was only present in 8% of the studies, and referred to personal control, perceived ability, and perceived level of ease or difficulty in following the VEG lifestyle [2,108,200]. Self-efficacy was predominantly based on TPB, referred to under the term Perceived Behavioral Control. This construct was adapted to the VEG context by several scholars [15,60,190]. This variable was most prevalent in studies on Vgt-Vgn-M (13%). Interestingly self-efficacy was not observed in Vgn and Vgt-M streams.

3.6.4. Social determinants

The social determinants included variables related to the influence of social ties or networks, as well as identity and social norms to act (or not) in accordance with VEG. Social network was present in 20% of the studies and measured through a variety of constructs, such as group membership [136], having VEG friends and family [8], or participation in a social movement [165]. An analysis of its presence in the different streams showed that it was most prevalent in research on Vgn (43%) and Vgt-M (29%). None of the reviewed studies measured social networks in the Vgt-Vgn-M-C stream.

Our analysis showed that identity was present in 11% of the studies and was analyzed using different approaches, such as political [165], social [18,127,131], or self [142,190] identities. A notable recent construct was that of “dietarian identity” [14,18,132,179], as measured by the Dietary Identity Questionnaire [271]. Dietarian identity refers to individuals' self-image with regard to consuming or avoiding animal-based products, regardless of their actual food choices [2,166,168]. This latter qualifier is important to consider in VEG studies, because people's actual diets and their self-reported dietary identity may appear inconsistent. For example, people who self-identify as a “vegan” might still consume animal products occasionally, while other people may strictly avoid animal products but not consider themselves to be “vegan.” [166]. This variable stood out in studies on the Vgt-Vgn-M stream (20%), followed by Vgt (19%).

Finally, another way in which social determinants appeared in the literature was through the social norms, which referred to the social pressure received from society and significant others to adopt (or reject) VEG alternatives [60]. Specifically, we found this variable in 8% of the studies. In some cases, it referred to imperative (perceived social pressure) and descriptive norms (the number of VEG people in the participant's circle) [141,205]. However, it was more commonly understood as subjective norms, close to the operationalization in TPB (as the extent to which participants consider that significant people in their lives think they should follow or avoid a VEG lifestyle) [2,15]. Social norms were mainly analyzed in the Vgt-Vgn-AHR (16%) and Vgt-Vgn-M (14%) streams.

3.6.5. Situational variables

This group included product attributes and informational signals regarding VEG. Present in 22% of the studies, research on product attributes focused on two types of attributes: (1) extrinsic attributes, such as labeling, nutrition information, functional claim, visibility, affordability, accessibility, promotion, or availability [21,86,242]; and (2) intrinsic attributes, such as texture, taste, smell, visual appearance, color, or size [143,231]. Product attributes were observed dominantly in studies on Vgt-Vgn-M-C (55%), followed by Vgt-Vgn-M (27%), and Vgt-Vgn (21%).

Our analysis identified that 19% of the studies focus on analyzing the effect of different informational signals on raising awareness of VEG [144], promoting VEG products [52], and eliciting cognitive or emotional responses to VEG information [52]. For example, some studies focused on measuring the effect of exposure to specific ethical or environmental messages [170,182,258], documentaries [165], or campaigns [174] on the perception of VEG alternatives. Another group of studies measured the impact that different VEG food images had on consumers [5,52,188]. It is worth noting that these studies were often experimental and were conducted online or in laboratory settings [3,170]. Informational signals were mainly explored in studies in Vgn (33%), followed by Vgt-Vgn-M-C (31%) and Vgt-Vgn-AHR (29%) streams.

As discussed above, research has focused on examining a wide range of variables to understand the VEG phenomenon. To summarize, Fig. 7 depicts a conceptual map of the relationships explored in the reviewed studies. It is important to note that the aim of this map was not to provide a conclusive explanatory model, but rather to show how the relationship between the variables has been conceptualized in the literature and illuminate future avenues of research. The map schematically proposes that situational variables elicit certain emotional responses, which in turn can affect knowledge and attitudes toward VEG. Likewise, attitudes, a variable closely related to individuals’ values and beliefs, have a direct impact on intention, which may originate from different motivations. Intentions are assumed to be directly affected by social networks, social norms and self-efficacy, and indirectly affected by identity and personality traits. Finally, the direct and indirect effect of all these variables translates into actual behavior. All these variables translate into actual behavior.

Fig. 7.

Conceptual map of measured variables in quantitative VEG studies.

3.7. HOW the VEG studies were conducted?

All 307 studies in this review were quantitative, as per the inclusion criteria; however, we found that the studies included different research designs. Sixty-eight percent of the studies were conducted based on correlational or non-experimental design (collecting data based on surveys). Among the non-experimental studies, eight were mix-method designs and included both qualitative and quantitative data, for which we coded the quantitative part (Table 8 in Annex). Thirty-two percent of the studies were experimental. Among these, 17 were choice experiments. In addition to varied research designs, we observed different types of information regarding the data collection, sample characteristics, and statistical analysis. We discuss these three aspects below.

3.7.1. Data collection

Regarding the type of studies conducted, 87% were based on cross-sectional data (vs. 13% longitudinal data) [138,162,204]. It is worth mentioning that only 47.5% of the studies reported the year of data collection. Among the experimental studies, 31% dealt with between-participant and 9% with within-participant designs. Furthermore, the settings of these experiments were mainly online [156,159,269], in research laboratories [135,209], or in restaurants or cafeterias [186]. Manipulations varied depending on the research objective, but many involved the use of exposures to different stimuli, such as informational text messages [110,114,187], images of food [5,86,111,167], or manipulated menu design [110,125,186].

Analyzing the data sources utilized in the reviewed studies revealed that 92% of the studies relied on primary sources, 7% employed secondary data, and only a limited number used both primary and secondary data [2,21,231]. The secondary data sources were mainly obtained from national panels, such as the US National Health Survey [53], the Swiss Food Panel [4,176], the UK Integrated Household Survey [204], and the German Socioeconomic Panel [87]. An examination of the methodologies used for collecting primary data revealed that a large number of studies relied on a single source (89.5%). Relatedly, the most commonly used method was self-reported data. Only 13% of the studies supplemented the self-reported method with additional information such as body measurements [101,113,164], brain responses [135,167], or implicit attitudes [3,43,111,209].

Of the studies that used primary data, most employed surveys to collect data; among these, the use of Likert scales (ranging from 1 to 5) and yes-or-no questions was prominent. Although the reliability of the scales was addressed in general terms (mainly through Cronbach's alpha), the validity of the scales was often not considered. In this sense, factor analyses (exploratory and confirmatory) were only used in 14% of studies as the most appropriate techniques to test the validity of the scales. It should be mentioned that although many complex concepts related to VEG were investigated, 65% of the studies did not use constructs but single variables. Moreover, most variables did not result from the operationalization of the constructs from a specific theoretical framework.

3.7.2. Sample

The unit of analysis in 98% of the studies was the individual respondents; the rest focused on other units, such as households [183,204]. Additionally, we found that sample sizes ranged from 10 [101] to 143,362 [204] and that 11% of the studies used 100% student samples. The measurement of some socio-demographic variables was present in all the studies as necessary information to describe the sample; however, not all studies presented all or the same type of information. Regarding sex, the sample consisted of both male and female participants, except for six studies conducted exclusively with females [112,122,172,185,197]. The data also showed that female participation was generally higher than male participation, with an average of 64% of the total sample. Among those that provided this data, the percentage of female participants was higher than 50% of the total number of cases in 72% of the cases. Concerning the ethnic composition of the sample, we found that only 8% of the studies provided information on ethnicity, 74% of the respondents from the samples (on average) were Caucasian and that one study was conducted entirely on African-Americans [230]. In terms of age, 40% of the studies did not report the mean age of respondents and 98% used adults as a sample, meaning that only a few studies focused on children [12,44,140,141,215]. Regarding the VEG status of the respondents, 54% of the studies were conducted on VEG and non-VEG participants [42,205,230], 25% on only VEG participants [18,45,177], and 20.84% on only non-VEG participants [13,110,143].

3.7.3. Statistical techniques

The most used statistical techniques in order of relevance were ANOVA (or ANCOVA and MANCOVA; 44%), chi-square test (21%), t-tests (17%), and Mann-Whitney test (3%). A few studies adopted a more predictive approach by running a model with the corresponding dependent and independent variables. In these cases, the most used techniques were OLS regression (16%) [e.g., 41], logistic regression (15%) [110], or SEM/PLS models (9.7%) [15,23,255]. Very few studies performed additional analyses, such as mediation (8%) [144], and moderation (2%) [15]. Some other studies tried to classify individuals according to different characteristics and primarily used statistical techniques, such as cluster (2%), [e.g., 84, 90, 151,193] or latent class (1%) [202,231] analyses.

However, normality was assumed in most cases; only 14% of all studies (experimental and non-experimental) reported (non)compliance with the normality assumption [15,42,144]. Additionally, very few studies (20%) warned of the risk of certain or potential bias, especially the risk associated with Common Method Effects, such as selection or social desirability biases. Of these few studies, only some performed any statistical technique to ensure that bias did not threaten the results; they mainly mentioned this it in the limitations.

4. Discussion

This systematic literature review shed light on the development of quantitative peer-review studies on VEG published up to December 31, 2022, within psychology, behavioral science, social science, and consumer behavior domains. The 6W1H analytical approach was chosen as a guide for analysis to have a holistic view of the literature and capture its multiple angles. This approach aimed to answer the questions of WHEN, WHERE, WHO, WHAT, WHICH, WHY, and HOW the research on VEG was published. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first systematic literature review conducted on VEG. In this section, we highlight and discuss the most relevant findings and gaps we drew from the study.

In line with the increasing worldwide attention to VEG alternatives and with other authors' observations [7,11,22], our study confirmed that researchers’ interest in studying VEG has grown, especially in the last ten years. The results of our review showed exponential growth of publications in recent years; specifically, the average number of publications, which increased from one in the 1980s and 1990s to 61 in 2022.

The present study also showed that such interest is particularly robust within English-speaking Western countries; in this regard, we identified a geographical gap in the literature, as the studies reviewed were mainly concentrated in the US, [e.g., 2,13,143] and the UK [e.g. Refs. [14,21,49]]. This geographical dominance, which could be due to multiple causes beyond the scope of this article (e.g., greater number of researchers, potential for research funding, availability of technology, and trajectory of veganism), is a major constraint to advancing knowledge on VEG, given that both human-animal relationships and food consumption are strongly influenced by cultural factors [281,282]. Accordingly, several criticisms have emerged, claiming that research on VEG is racially biased and strongly appropriated by Western culture [165].

As for the journals in which research on VEG was published, we observed an interesting change of focus. The study on this phenomenon was born with a strong link to journals focused on animal rights and activism as VEG was clearly presented as a manifestation of a philosophical, ethical, and political stance that questions the anthropocentric position of human beings with respect to the rest of the animals. However, our review clearly showed the preference of authors in recent years to publish their research in journals highly focused on analyzing the relationship between behavioral change and nutritional or dietary choices. In this sense, we found that Appetite was the journal chosen most frequently to publish quantitative studies on VEG. This evolution indicates that the rationale for healthy and sustainable eating in VEG research has become more prominent than ever, while the implications these alternatives have for animals have been diluted. In line with this, we found that the Vgt-Vgn. D approach of research dominated the literature, while the most prominent gap in the literature was of VEG as a life philosophy or social movement. This was illustrated by the arguments expressed by researchers to defend the relevance of studying VEG, the main driver being health, followed by animal protection, environmental concerns, and other considerations (religion or spirituality, world hunger, social factors, and sensory appeal). Taken together, our results add evidence to a recent concern in the literature about the depoliticization of VEG in society (especially in veganism) that is fading from its antagonistic origins [283]. The spread of VEG in academic endeavors, as well as in business and personal practices, seems more often motivated by personal health reasons (understood in terms of physiological health) than by ethical considerations.

Focusing on the objectives and methodological approach of the studies reviewed, we highlighted five main gaps. First, through the overview obtained on the topic, we realized a notable lack of research on consumer behavior change or the process of transitioning to VEG. We identified only a few studies that analyzed self-reported lifestyle changes [e.g. Ref. [177]], especially measuring actual behavior change over time [e.g. Ref. [174]].

Second, among the variables used, we noted a preference for studying rational and conscious content over emotions, feelings, and the unconscious mind in human behavior, [e.g. Refs. [[284], [285], [286]]]. To illustrate, although there was a strong interest in studying attitudes toward meat substitutes [231], VEG individuals [75], or VEG diet [144], it was very rarely accompanied by an adequate definition and measurement of the cognitive, affective, and conative dimensions widely recognized in the literature [287,288]. Despite plenty of measures developed to examine the psychology of meat-eating [22,289], such as carnism inventory [278], meat attachment [60], or moral disengagement to meat [213], we found gaps in the tools used to measure the variables examined in VEG studies. Although some well-known scales were incorporated, such as the disgust scale [290], or personality traits [291], in general, the instruments used to measure the constructs were often not validated in the literature but constructed ad hoc for the specific research being conducted. Very little progress has been made in the development of constructs and scales tailored to VEG. The exceptions to this are the Dietary Identity Questionnaire [271], Vegetarian Eating Motives Inventory [116], and Vegetarianism Treat Scale [277].

Third, we observed that in the field of VEG, data-driven research was more prominent than theory-driven research. This is an important shortcoming, given that data-driven methods are less likely to offer clear theoretical perspectives to help analyze results [292]. We agree with Schoenfeld [293] that “theory is, or should be, the soul of the empirical scientist” [p [105]]. Theory-driven approach is especially important in quantitative research owing to its deductive logic based on “a priori theories.” [ [294] p312]. Thus, the lack of anchoring research on VEG in theoretical frameworks is another of the gaps detected in our review.

Fourth, the rapid growth and innovation of software, together with the increased availability of diverse data sources, have expanded analytical capabilities and methodological options adapted to each topic. However, our research showed that such advances had very little impact on the field of VEG studies (at least in the non-medical VEG literature), as the richness of the data was not large (mainly self-reported and cross-sectional studies); descriptive and correlational statistical techniques remained the most used analytical approaches, highlighting another gap in VEG literature. However, one innovation that was recently incorporated in VEG research and is worth mentioning is brain response measurements. These types of measurement methods were rarely used [167] as the field is still dominated by self-reported surveys, as mentioned above. Nevertheless, the contrasting results of self-reported versus physiological responses in Anderson et al.‘s [167] study highlighted the importance of using multiple data sources when attempting to analyze people's responses and to inform the dietary patterns required in dietary scales, as they provide a richer and better picture of consumer behavior.

Fifth, with respect to the samples used in the VEG studies, it is pertinent to address two important matters. On the one hand, vegans and vegetarians were often merged and studied as a unified group. However, a growing body of research demonstrated that vegans and vegetarians not only present differences in terms of behavioral and attitudinal characteristics (such as identity profiles [93], value orientations [42], and cognitive ability [113]), but that the motivations driving the adoption of their lifestyles (animal protection, environment, and health) also influence how the person experiences the VEG alternative. On the other hand, studies were expected to clearly indicate the composition of their sample according to socio-demographic variables; however, our review showed that this practice was not always met, especially regarding ethnicity, sex, and age, variables highly relevant to food, ethical consumption, and animal protection [15,144]. Analyzing the studies that provide such information would reveal that research involving minors and culturally diverse groups [54] is notably scarce. However, considering that the adoption of VEG has traditionally had a philosophical foundation [1,16,[295], [296], [297]] and that certain responses to it are learned by social contagion [298], different mechanisms depending on the age of the participants and their cultural setting are expected. In addition, we detected a very narrow and traditional approach to the concept of “gender” in that most studies used the dichotomous categories of male and female. This approach does not align with the existing discourse on diversity and gender fluidity [299] and could hinder progress in deepening our understanding of the relationship between VEG, gender issues, and animal advocacy [300,301].

5. Conclusion

5.1. Contribution