Abstract

Educational institutions are imbued with an institutional meritocratic discourse: only merit counts for academic success. In this article, we study whether this institutional belief has an impact beyond its primary function of encouraging students to study. We propose that belief in school meritocracy has broader societal impact by legitimizing the social class hierarchy it produces and encouraging the maintenance of inequalities. The results of four studies (one correlational study, Ntotal = 198; one experiment, Ntotal = 198; and two international data surveys, Ntotal = 88,421 in 40+countries) indicate that belief in school meritocracy reduces the perceived unfairness of social class inequality in society, support for affirmative action policies at university and support for policies aimed at reducing income inequality. Together, these studies show that the belief that schools are meritocratic carries consequences beyond the school context as it is associated with attitudes that maintain social class and economic inequality.

Keywords: belief in school meritocracy, social inequality, perception of discrimination, social class

Educational institutions were designed to provide students with formal knowledge and basic skills to prepare individuals for their future position in society (Arrow, 1973). Yet, these institutions also convey informal cultural knowledge in the form of norms, values, and beliefs that underpin educational achievement (Mijs, 2016). Central to such informal knowledge is the belief in school meritocracy—the belief that school rewards students based on their abilities and effort (merit), and not their group membership. Believing that educational institutions are fair is so ingrained in the educational system that it has been called “the education revolution’s furthest-reaching and most salient sociological product so far” (Baker, 2014, p. 183). At the institutional level, the belief in school meritocracy provides educational institutions with their raison d’être. At the individual level, these beliefs mold self-concepts and personal definitions of success or failure (van Noord et al., 2019). However, we suggest that the belief in school meritocracy may carry psychological consequences beyond the realm of the school context in that it affects the perceptions of, and attitudes toward, social class and economic inequality in society at large.

Educational Institutions and the Belief in School Meritocracy

The main purpose of educational institutions is to educate and select students to produce a merit-based hierarchy that reflects individual ability and effort (UN General Assembly, 1948, art. 26). Consistent with this, most educational institutions officially claim that their selection rules are exclusively based on merit. The resulting selection is generally treated as legitimate and is rarely challenged: Educational credentials are seen as reliable indicators of individual merit and diplomas grant access to social and economic positions in society (Easterbrook et al., 2016; Kuppens et al., 2018).

Educational institutions—both overtly and more implicitly—encourage students to believe in school meritocracy: educational institutions’ structure, discourse, and selection practices contribute to the institutionalization of an individualistic self-concept where talent and effort are seen to be the key factors of academic success (Beauvois, 2003; Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990; Deutsch, 1979; Spruyt, 2015). This idea is supported by dozens of field studies and experiments that explored this “norm of internality” (Beauvois & Dubois, 1988). These studies showed that (1) teachers value internal attributions (talent and effort) for success and failure and reward internal explanations with better grades and scholastic judgments and (2) students are particularly likely to use internal attributions of success and failure when their goal is to please their teachers (Dompnier et al., 2006; Pansu et al., 2008). In short, students are aware that meritocratic beliefs are desirable and rewarded in the education system. School culture can also transmit beliefs in school meritocracy: A longitudinal study (N = 5,648) showed that school culture emphasizing meritocracy not only affects students’ perceptions of effort as a means to succeed but also encourages the internalization of academic achievement as a component of the students’ self-image (Trautwein et al., 2006).

School Meritocracy and Educational Inequality

The belief in school meritocracy is firmly rooted in educational institutions (Brown & Tannock, 2009) despite a large body of evidence showing that educational inequality remains a considerable challenge. For instance, a study combining 30 international large-scale assessments (100 countries and 5.8 million students) provides robust evidence that the socioeconomic status (SES) achievement gap has increased in most countries over the past 50 years (Chmielewski, 2019). Nowadays, across Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2014) countries, the likelihood of attending a tertiary institution is twice as high if at least one parent has a high school diploma, and 4.5 times higher if the parents attained tertiary education.

Moreover, equality of opportunity is not always guaranteed: differences in educational attainment are observed even when abilities are comparable. For instance, many field studies and experiments have shown that lower-SES students receive lower expectations, lower grades and lower tracking recommendations from teachers than higher-SES students with the same level of performance (Autin et al., 2019; Barg, 2013; Batruch et al., 2019; Geven et al., 2021; Timmermans et al., 2018). In sum, educational institutions may (at least partially) fail to fulfill their meritocratic objectives, and, rather ironically, they may even contribute to the reproduction of social inequality (van de Werfhorst & Mijs, 2010). Recent research provides evidence that the belief in school meritocracy may paradoxically encourage the persistence of inequality of opportunities at school (Darnon, Wiederkehr, et al., 2018; Wiederkehr et al., 2015). Endorsement of school meritocracy beliefs was associated with a decrease in students’ and parents’ willingness to implement equalizing practices at school (Darnon, Smeding, & Redersdorff, 2018), and inducing this belief in classrooms reduced math and reading performance of lower-SES fifth graders (Darnon, Wiederkehr, et al., 2018).

Belief in Meritocracy and the Justification of Inequality

Belief in school meritocracy may be derived from a specific institutional discourse and shares similarities with other larger systems of societal beliefs sometimes summarized as system-justifying beliefs (e.g., general meritocratic, system-justification, protestant work ethic, just world). A specificity of system-justifying beliefs is that they tend to present the status quo positively. Prior work has found that this particularity can spill over to legitimizing the status quo between unequal groups (Jost & Hunyady, 2005). A systematic review found that priming meritocracy encourages negative evaluations, facilitates the use of stereotypes targeting low-status groups, and negatively affects decisions involving low-status group members (Madeira et al., 2019). Observational evidence indicates that a preference for meritocracy is associated with downplaying racial inequality (e.g., Knowles & Lowery, 2012), and an increase in the likelihood to embrace internal attributions to explain disadvantaged groups’ outcomes (Kuppens et al., 2018; McCoy & Major, 2007; Rüsch et al., 2010).

While prior research has found that the perception of inequalities is associated with a greater willingness to challenge the status quo (e.g., through policy and collective action; van Zomeren et al., 2008) system-justifying beliefs (such as a belief in meritocracy) weaken the strength of this relationship. For instance, cross-national evidence has shown that greater endorsement of meritocratic beliefs (at the individual or country level) is associated with the legitimatization of income inequalities (Mijs, 2021). Similar associations have been observed for the belief in the protestant work ethic—a construct conceptually related to meritocracy. A meta-analysis found that scores on the Protestant Work Ethics scale were positively associated with prejudice and negatively with the endorsement of policies aimed at helping disadvantaged members of society (Rosenthal et al., 2011). As for their effects on lower-status group members, system-justifying beliefs seem to provide some psychological benefits to all individuals (including low-status group members), but they can have negative effects at the group level by impeding intentions to advance group rights through means of collective action (Foster et al., 2006; McCoy et al., 2013; Osborne et al., 2019).

Even though there is significant conceptual overlap between system-justifying beliefs (and general meritocracy more specifically) and belief in school meritocracy, theoretically speaking, they are not identical. First, conceptually speaking, the two concepts relate to two different levels of abstraction. Whereas general meritocracy beliefs entail more diffuse societal beliefs (e.g., just-world beliefs) that are not attached to specific institutions or to specific agents responsible for safeguarding meritocracy, belief in school meritocracy is a belief that is linked to a specific institution with clear institutional objectives. Second, school meritocracy is a necessary but not sufficient condition for general meritocracy to exist in society; that is a country may have meritocratic schools for instance but not a meritocratic society. Indeed, this is the case in many countries where school meritocracy and violations of general meritocracy (e.g., high corruption) are both high (e.g., Maldives, Lesotho, the Philippines, South Africa, and Uzbekistan are among the 10 most educationally mobile countries in the world in spite of their high levels of corruption; see Global Database on Intergenerational Mobility, 2018; Corruption Perception Index; 2021 1 )

The Present Research

We propose that belief in school meritocracy legitimizes the social and economic hierarchy well beyond the school context. We conducted four studies testing the hypothesis that belief in school meritocracy affects perceptions and attitudes related to the social and economic hierarchy in society at large. Specifically, we formulated two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Belief in school meritocracy should be associated with lower perceived unfairness of social class (Studies 1–2) or income (Studies 3a–3b) inequality.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Belief in school meritocracy should be associated with lower willingness to challenge inequality either by means of collective action (H2a; Studies 1–2) or by supporting policies that aim to reduce inequality (H2b; Studies 1–3b).

Study 1

Study 1 tested the main hypothesis that belief in school meritocracy is associated with attitudes beyond the school context, namely, lower perceived unfairness of social class inequality (H1), willingness to challenge social class inequality by means of collective action (H2a), or through policy change (H2b). In line with previous research findings (van Zomeren et al., 2008), in Study 1, we also explored whether perceptions of discrimination and privileges mediate the effect of belief in school meritocracy on willingness to pursue collective action or policy changes.

Method

Participants

Psychology students from a large Australian university (N = 198) completed an online questionnaire for course credits (168 women and 30 men). As we did not have an a priori expectation about the target effect size, the sample size was determined by the number of participants who signed up for the study during the course of one semester. A sensitivity power analysis revealed that our sample size was sufficient to detect a small-sized effect (f2 = 0.04) of belief in school meritocracy using a multiple regression with one control variable with a power of .80 (α = .05).

Variable

All measures used a 7-point response scale. All items, material, data, and code can be found online at: https://osf.io/at236/?view_only=8b33efb78d754a7188d841a1e42579a4.

Predictor Variable: Belief in School Meritocracy

Wiederkehr et al.’s (2015) eight-item belief in school meritocracy scale was adapted to the Australian university context (e.g., “In school, students get the grades they deserve,”α = .80, M = 4.21, SD = 0.92). Higher scores indicated a greater belief in school meritocracy.

Outcome Variables Testing H1: Perceived Unfairness of Social Class Inequality

Perception of Social Class Discrimination

Schmitt et al.’s (2002) 5-item perception of discrimination scale was adapted to social class. (e.g., “Individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds as a group have been victimized by society,”α = .84, M = 4.78, SD = 0.96). For this and the subsequent measures of perceptions of inequality, higher scores indicated more perceived discrimination against individuals of lower SES.

Perception of Social Class Privileges

Schmitt et al.’s (2002) 5-item perception of privilege scale was adapted to social class (e.g., “Individuals from higher socioeconomic backgrounds in general have had opportunities that they wouldn’t have gotten if they were from a lower socioeconomic background,”α = .77, M = 5.30, SD = 0.86).

Perception of Institutional Social Class Privileges (at University)

Five items were created to measure perception of social class privilege at university (e.g., “Schools tend to prefer students from high socioeconomic backgrounds,”α = .79; M = 3.50, SD = 1.09).

Outcome Variables Testing H2a: Willingness to Engage in Collective Action

General Collective Action

Jetten et al.’s (2011) three-item collective action scale was adapted to social class (e.g., “Thinking about how individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are treated makes me want to fight for their rights,”α = .80; M = 4.82, SD = 1.07).

Specific Collective Action

Four items were created to measure collective action intentions at university (e.g., “I would take part in a demonstration to raise awareness about socioeconomic inequality in Australia,”α = .88; M = 4.05, SD = 1.24).

Outcome Variable Testing H2b: Support for Policies Reducing Social Class Inequality

Four items were created to measure support for affirmative action policies (e.g., “I think that schools/universities should allow students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds to enter with slightly lower grades,”α = .42; M = 4.48, SD = 0.84).

Control Variables: Political Orientation and Subjective SES

Political orientation and subjective SES were included as control variables as they may be associated with belief in meritocracy, and perceptions of discrimination as well as general attitudes toward inequality (Son Hing et al., 2011). Participants reported their political orientation on a scale ranging from 1 (very liberal) to 7 (very conservative) and indicated their subjective SES by choosing where they stand in terms of SES on a scale from 1 (lowest SES) to 10 (highest SES, see MacArthur scale; Kraus & Stephens, 2012).

Results

To test Hypotheses 1, 2a, and 2b, for each of our six outcome variables, we performed a linear regression analysis with belief in school meritocracy as a predictor and political orientation and subjective SES as control variables. As shown in Table 1, results indicated that belief in school meritocracy was negatively related to perception of social class discrimination, perception of social class privileges, and perception of institutional social class privileges (H1), general collective action intentions, but not specific collective action (H2a), and support for affirmative action (H2b).

Table 1.

Effects of Belief in School Meritocracy Controlling for Political Orientation and Subjective SES in Study 1.

| Belief in school meritocracy | Political orientation | Subjective SES | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | β | SE | p | η2p | β | SE | p | η2 | β | SE | p | η2 |

| Social class discrimination (H1) | −.15 | .07 | .04 | .02 | −.22 | .06 | .00 | .06 | −.06 | .05 | .15 | .01 |

| Social class privileges (H1) | −.20 | .06 | .00 | .05 | −.12 | .05 | .03 | .02 | −.13 | .04 | .00 | .06 |

| Institutional privileges (H1) | −.23 | .08 | .00 | .04 | −.02 | .07 | .72 | .00 | −.19 | .05 | .00 | .06 |

| General collective action (H2a) | −.19 | .08 | .02 | .04 | −.06 | .07 | .34 | .00 | −.03 | .05 | .55 | .00 |

| Specific collective action (H2a) | −.04 | .10 | .67 | .00 | −.07 | .09 | .38 | .00 | −.04 | .06 | .52 | .00 |

| Support for affirmative action (H2b) | −.20 | .06 | .00 | .05 | −.25 | .05 | .00 | .11 | −.04 | .04 | .34 | .00 |

Note. SES = socioeconomic status.

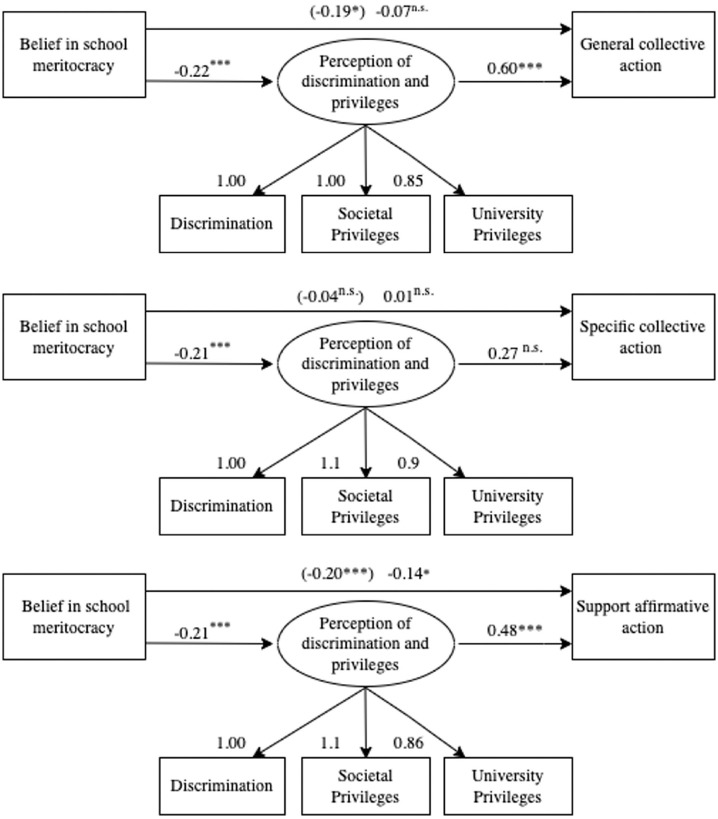

Supplementary Analyses: Structural Equation Models

We tested whether our measures of perceptions of discrimination and privileges may be used as a latent mediator between our predictor and our three outcome variables. Results of the analyses controlling for political orientation (see Figure 1) suggest that support for general collective action and for affirmative action are mediated by perceptions of discrimination and privileges. The indirect paths for both outcomes were also significant (ps < .005). In the case of specific collective action, neither the total effect nor the effect of the mediator on the outcome was significant.

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Models Controlling for Political Orientation in Study 1.

Study 2

Study 2 tested the same hypotheses as Study 1 using an experimental design (i.e., manipulations of school meritocracy) to assess the causal nature of the effects.

Method

Participants

Psychology students from an Australian university (N = 192; 140 women, 49 men and 3 non-binary persons) completed an online questionnaire for course credits. A power analysis using G*Power for an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with one between-participants variable and one control variable with a power of .80 (α = .05) revealed that 191 participants were needed to detect the same effect size as observed in Study 1 (ηp2 = .04).

Variables

School Meritocracy Manipulation

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions: high or low school meritocracy. In the high level of school meritocracy condition (n = 99), participants were asked to read the following text: “A report from the OECD suggests that (. . .) Australia is a ‘world leader in educational mobility.’” This means that ‘there are very few barriers for Australian students who work hard to get ahead in the educational system.’ This was followed by statistical information indicating that social class has little impact on educational outcomes in Australia. In the low level of school meritocracy condition (n = 93), the text read as follows: “While educational disadvantage is a problem across the globe, the problem is especially pronounced in Australia. This means that there are still many barriers even for Australian students who work hard to get ahead in the educational system.” This was followed by statistical information indicating that social class has a strong impact on educational outcomes in Australia. Note that the text manipulating low vs. high levels of school meritocracy was adopted from two separate articles from “The Conversation” (for the content of the manipulation, see the Supplemental Material). In both conditions, to ensure that they read it thoroughly, participants were asked to write a short summary of the results presented in the text.

Variables

After the manipulation, participants answered the same measures as used in Study 1, for descriptive information, see Table S1 in the Supplemental Material.

Results

For our six outcome variables, we again performed linear regression analysis with meritocracy condition (coded −0.5: low school meritocracy; 0.5: high school meritocracy) as a predictor and political orientation and subjective SES as a control variables. Consistent with Study 1, results indicated a negative effect of the manipulation of school meritocracy on perception of social class discrimination, perception of social class privileges, perception of institutional social class privileges (H1), and support for affirmative action (H2b). We did not observe a significant effect on general and specific collective action intentions (H2a). Table 2 presents the full results. We ran additional analyses with subjective social status as a control variable. Results remained identical.

Table 2.

Effects of Experimental Condition (School Meritocracy) Controlling for Political Orientation and Subjective SES in Study 2.

| Variables | Belief in school meritocracy | Political orientation | Subjective SES | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | p | η2p | β | SE | p | η2 | β | SE | p | η2 | |

| Social class discrimination (H1) | −.37 | .14 | .01 | .04 | −.14 | .06 | .04 | .02 | −.07 | .05 | .18 | .01 |

| Social class privileges (H1) | −.44 | .13 | .00 | .06 | −.09 | .06 | .16 | .01 | −.04 | .05 | .40 | .00 |

| Institutional privileges (H1) | −.40 | .16 | .01 | .03 | −.11 | .07 | .10 | .01 | −.02 | .06 | .78 | .00 |

| General collective action (H2a) | −.06 | .15 | .68 | .00 | −.28 | .07 | .00 | .08 | −.03 | .05 | .64 | .00 |

| Specific collective action (H2a) | −.30 | .19 | .12 | .01 | −.28 | .09 | .00 | .05 | −.02 | .07 | .72 | .00 |

| Support for affirmative action (H2b) | −.23 | .12 | .05 | .02 | −.19 | .05 | .00 | .06 | −.07 | .04 | .08 | .02 |

Note. SES = socioeconomic status.

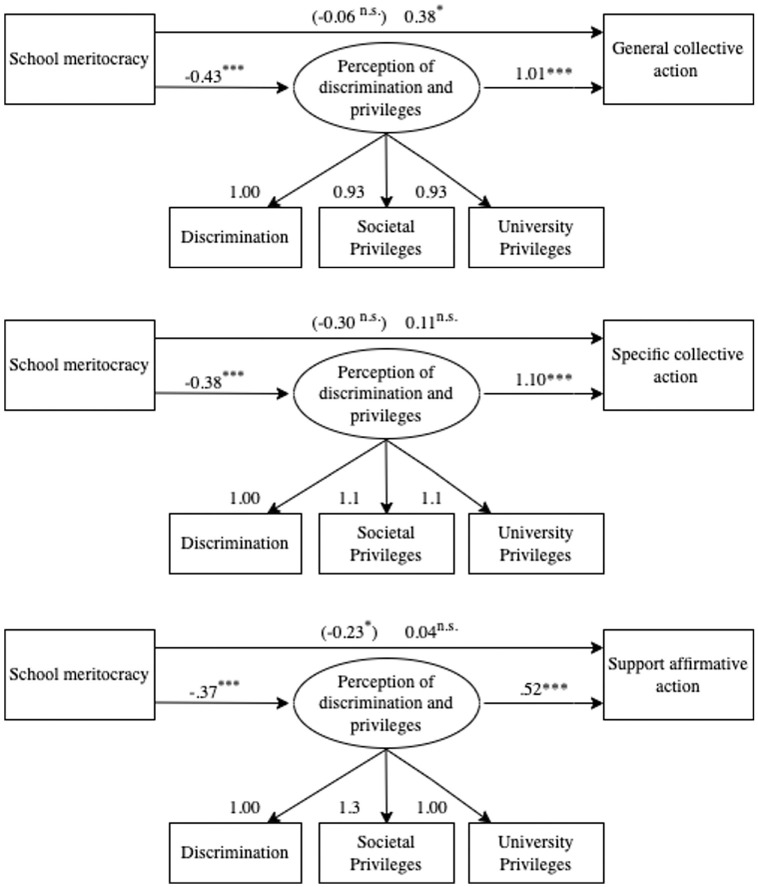

Supplementary Analyses: Structural Equation Models

We again explored whether a latent construct tapping perception of discrimination and privileges mediated the effect of the manipulation on our three outcome measures. Results of the analyses controlling for political orientation show that all direct paths (ps > .001; see Figure 2) and indirect paths were significant (ps < .012; see the Supplemental Material, p. 5) even though the total effect on general and specific collective action were not.

Figure 2.

Structural Equation Models Controlling for Political Orientation in Study 2.

Discussion

These results replicate Study 1 findings and show experimentally that the manipulation of school meritocracy causally reduced the perceived unfairness of social class inequality (H1) and support for policies aimed at reducing social inequality (H2b). Moreover, it appears that perceptions of injustice mediate the effect of belief in school meritocracy on support for affirmative action policies. The support for our hypothesis that belief in school meritocracy reduces willingness to engage in collective actions (H2a) is more mixed.

This could be because the target victim group (low-SES individuals) is not the same as participants’ own group (university students at a prestigious university). Belonging to the disadvantaged group is often an important antecedent of collective action, as shown by van Zomeren et al. (2008). The results of the supplementary analyses, however, do indicate that belief in school meritocracy may at least partially affect collective action intentions indirectly by inducing stronger perceptions of group-based injustice.

Study 3a

In the first two studies, the generalizability of the findings is limited by the size and nationality of the samples (Henrich et al., 2010). Some dependent variables (e.g., institutional privilege) were also conceptually close to the predictor. For these reasons, Study 3a used a large-scale cross-national sample that measured income inequality-relevant variables. We tested the hypotheses that belief in school meritocracy is associated with lower perceived unfairness of income inequality (H1) and lower support for policies aimed at reducing income inequality (H2b). Testing boundary conditions of our effects, we focused in particular on tests of the hypothesis that effects may be stronger for those who benefit more from the status provided by a belief in school meritocracy (i.e., highly educated individuals). We also explored whether the national context (i.e., national income inequality and national educational inequality) may also be a boundary condition of the effects.

To ensure that belief in school meritocracy is indeed conceptually distinct from general meritocracy belief, we also conducted further analyses controlling for general meritocracy belief. Because earlier research used different operationalization of this concept (García-Sánchez et al., 2019; Mijs, 2021; Roex et al., 2019), we used all six different possible operationalizations. Results from our further analyses revealed that all original effects remained significant when controlling for general meritocracy belief and that general meritocracy belief itself was often not significant in the models tested. For details, see Tables S11–16 in the Supplemental Material.

Method

Sample

We used the data from the 2009 social inequality module of the International Social Survey Program (ISSP). The ISSP is a series of national surveys based on probability-stratified sampling to ensure cross-national comparability. Given that most of the variables of interest contain questions about income inequality, we excluded participants who did not receive a regular income (i.e., students, unemployed individuals not looking for employment or individuals who never worked). The analytical sample comprised 51,794 individuals (54.83% females; Mage = 48.41; SD = 16.43) from 41 countries (n = 126,327 respondents per country).

Variables

All measures used 5-point response scales.

Predictor Variable: Belief in School Meritocracy

School meritocracy belief was operationalized following García-Sánchez et al.’s (2019) procedure. The items refer to the belief that people have equal access to educational opportunities regardless of systematic group-based 2 (e.g., “In your country, people have the same chances to enter university, regardless of their gender, ethnicity, or social background”). We averaged the three items, see S6 in the Supplemental Material for all items (α = .58 3 , M = 3.24, SD = 0.90). Higher values indicate a stronger belief in school meritocracy.

Outcome Variables Testing H1: Perceived Unfairness of Income Inequality

We averaged all 2009 ISSP items (i.e., three) relevant to H1 (e.g., “Differences in income in your country are too large,”α = .68, M = 3.77, SD = 0.94). Higher values indicated higher perceived unfairness. See Table S8 in the Supplemental Material for a description of the items.

Outcome Variables Testing H2B: Support for Policies to Reduce Income Inequality

We averaged all 2009 ISSP items (i.e., five) relevant to H2b (e.g., “Is it the responsibility of government to reduce differences in income?,”α = .56, M = 3.78, SD = 0.63). Higher values indicated higher support for policies.

Results

We ran regression models including country fixed effects (dummy variables for countries). Fixed-effects models allow to control for all time-invariant country-specific factors and focus exclusively on within-country effects. The estimates of this model are therefore not contaminated with spurious effects of stable, unmeasured country confounders (known as unobserved heterogeneity), such as different level of educational inequality or income inequality in countries (Verbeek, 2008). This analytical strategy enables one to isolate the effects of belief in school meritocracy over and above the actual level of educational meritocracy by only comparing participants within the same countries (i.e., effect of low vs. high belief in school meritocracy within the same [actual] meritocratic school context). Beta coefficients should be interpreted as the pooled within-country effect of belief in school meritocracy on the outcome measures.

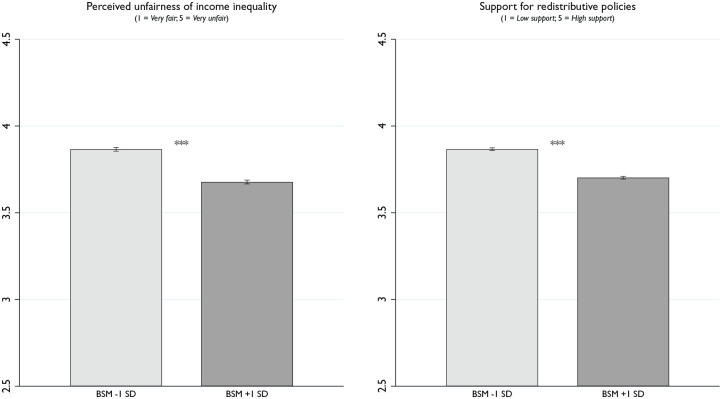

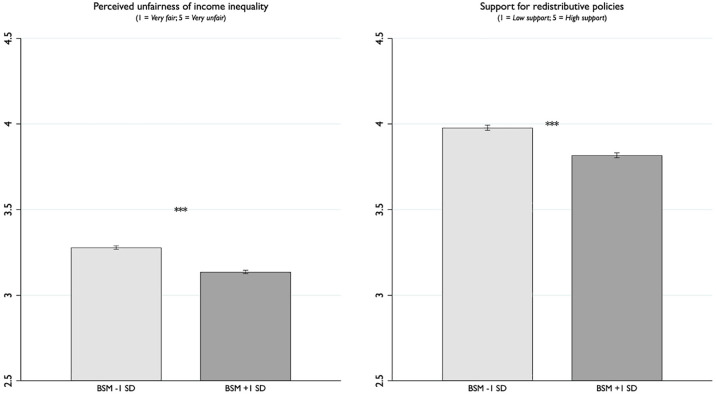

For both outcome variables, we used belief in school meritocracy as a predictor and educational degree and age as control variables (Figure 3). The two control variables were included as they potentially affect participants’ belief in school meritocracy (i.e., different diplomas or cohorts experiencing different education systems) as well as their attitudes toward income inequality (i.e., different income). Results indicated that higher belief in school meritocracy was negatively associated with the perceived unfairness of income inequality (H1), and support for policies aimed at reducing inequality (H2b). Table 3 presents the full results.

Figure 3.

Effect of Beliefs in School Meritocracy in Study 3a.

Note. BSM = belief in school meritocracy.

Table 3.

Fixed-Effect Models; Centered Variables, Controlling for Respondents’ Age, in Study 3a.

| Model 0 (main effects) | Model 1 (interaction effect) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | H1: inequality unfair | H2b: support for redistributive policies | H1: inequality unfair | H2b: support for redistributive policies | ||||

| BSM | −0.10*** | (0.005) | −0.09*** | (0.003) | −0.11*** | (0.005) | −0.09*** | (0.003) |

| Degree | −0.04*** | (0.003) | −0.03*** | (0.002) | −0.04*** | (0.003) | −0.03*** | (0.002) |

| BSM × degree | −0.02*** | (0.003) | −0.01*** | (0.002) | ||||

| Cons. | 3.76*** | (0.0012) | 3.69*** | (0.008) | 3.76*** | (0.0012) | 3.69*** | (0.008) |

| Adj. R2 | .0169 | .0288 | .0179 | .0296 | ||||

| Log lik. | −62,206 | −44,124 | −62,179 | −62,179 | ||||

| N | 50,651 | 50,665 | 50,651 | 50,665 | ||||

Note. BSM = belief in school meritocracy.

p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001; ISSP 2009.

We also ran the same models with two additional control variables: political orientation and wealth. However, these variables were not included in the main models because of the large number of missing values. Including these variables meant approximately 75% of responses were lost (Ncountry = 31; Ntotal = 11,347). The detailed summary of these results—which were stronger with the added control variables—can be found in the Supplemental Material (Table S2).

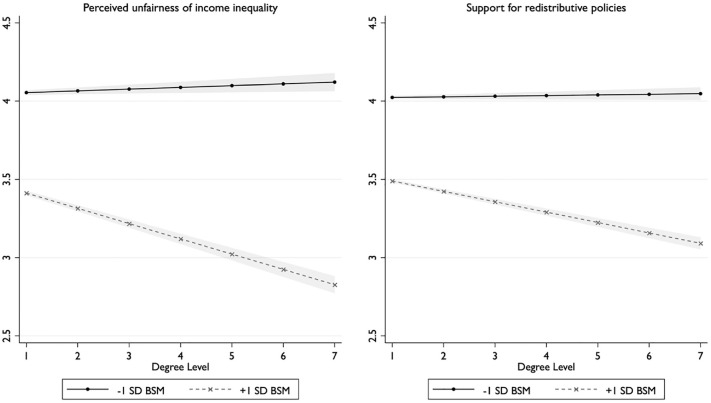

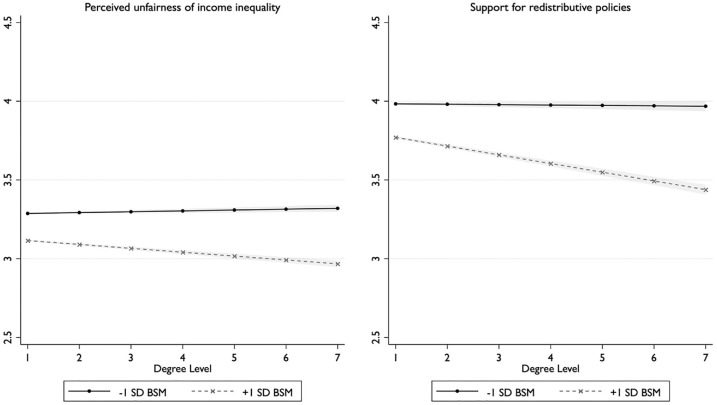

As a supplementary analysis, we added the interaction term between educational degree and belief in school meritocracy in each of our main models. This analysis aimed to explore whether the legitimizing effect of belief in school meritocracy is stronger for individuals who benefited most from the school system (Duru-Bellat & Tenret, 2012; Kuppens et al., 2018). Results indicated that the effects of belief in school meritocracy on the perceived unfairness of social class inequality and lower support for redistributive policies was stronger for more educated participants than less educated participants (see Table 3 and Figure 4). The same analyses were conducted with educational degree as a categorical variable. Results can be found in the Supplemental Material (Tables S3 and S4).

Figure 4.

Effect of Beliefs in School Meritocracy as a Function of Educational Degree in Study 3a.

Note. BSM = belief in school meritocracy.

In Supplementary Material (Tables S17–18), we also report multilevel analyses exploring whether the effect of belief in school meritocracy or its interactive effect with educational degree varied as a function of national income inequality (i.e., Gini index), or national educational inequality (i.e., intergenerational mobility index). Overall, results showed that the effect of belief in school meritocracy was stronger in more economically egalitarian countries for both dependent variables and in educationally egalitarian countries for support for distribution policies. The interactive effect with degree was also stronger in more economically egalitarian countries for support for distribution policies. Note that given the rather low number of higher-level clusters (N = 40), these results should be interpreted with some caution (Arend & Schäfer, 2019).

Study 3b

Study 3b replicated Study 3a with more recent data (2018). By testing support for our hypotheses 10 years after the 2007/2008 Global Financial Crisis (which may have affected attitudes toward income inequality), we can determine the robustness of our findings. Study 3b also added relevant control variables in the main analyses.

Method

Sample

We used the 2018 round of the European Social Survey (ESS), another series of national surveys based on probability-stratified sampling to ensure cross-national comparability. Once again, we excluded participants who did not receive a regular income. The analytical sample comprised 44,879 individuals (Mage = 53.06; SD = 17.27; 53.62% female) from 29 countries (n = 154,755 respondents per country).

Variables

Predictor Variable: Belief in School Meritocracy

One item was used to measure belief in school meritocracy (“Overall, everyone in [country] has a fair chance of achieving the level of education they seek”; M = 5.81, SD = 2.49). Responses ranged from 1 to 11. Higher scores indicated higher belief in school meritocracy.

Outcome Variables Testing H1: Perceived Unfairness of Inequality

We recoded and averaged all 2018 ESS items (i.e., six) relevant to H1 (e.g., “In your opinion, are differences in wealth in [country] unfairly small, fair, or unfairly large?,”α = .55, M = 3.22, SD = 0.71). Responses ranged from 1 to 5. A higher score indicated higher perceived unfairness. See Table S21 in the Supplemental Material for a description of the items.

Outcome Variable Testing H2b: Support for Policies to Reduce Income Inequality

We used the only 2018 ESS item relevant to H2b: “The government should take measures to reduce differences in income levels” (M = 3.91, SD = 0.98). Responses ranged from 1 to 5. A higher score indicated higher support for the redistributive policy.

Results

For both outcome variables, we used belief in school meritocracy as a predictor and educational degree, age, political orientation, and household income as control variables (Figure 5). Results indicated that higher belief in school meritocracy was negatively associated with the perceived unfairness of social class inequality (H1), and support for policies aimed at reducing inequality (H2b). Table 4 presents the full results.

Figure 5.

Effect of Beliefs in School Meritocracy in Study 3b.

Note. BSM = belief in school meritocracy.

Table 4.

Fixed Effect Models; Centered Variables, Controlling for Respondents’ Age, in Study 3b.

| Model 1 (main effects) | Model 2 (interaction effect) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | H1: inequality unfair | H2b: support for redistributive policies | H1: inequality unfair | H2b: support for redistributive policies | ||||

| BSM | −0.03*** | (0.001) | −0.03*** | (0.002) | −0.03*** | (0.001) | −0.03*** | (0.002) |

| Degree | −0.01*** | (0.002) | −0.03*** | (0.03) | −0.01*** | (0.002) | −0.03*** | (0.003) |

| Income | −0.02*** | (0.001) | −0.04*** | (0.002) | −0.02*** | (0.001) | −0.04*** | (0.002) |

| Political orient. | −0.05*** | (0.002) | −0.08*** | (0.002) | −0.05*** | (0.002) | −0.08*** | (0.002) |

| BSM × degree | −0.01*** | (0.001) | −0.01*** | (0.001) | ||||

| Cons. | 3.55*** | (0.020) | 4.67*** | (0.030) | 3.52*** | (0.018) | 4.55*** | (0.027) |

| Adj. R2 | .0590 | .0740 | .0607 | .0762 | ||||

| Log lik. | −29,941 | −42,615 | −299,120 | −42,575 | ||||

| N | 32,132 | 31,960 | 32,132 | 31,960 | ||||

Note. BSM = belief in school meritocracy.

p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .00; ESS 2018.

We again added the interaction term between educational degree and belief in school meritocracy in each of our main models. Replicating Study 3a, results indicated that the effects of belief in school meritocracy on the perceived unfairness of income inequality and lower support for redistributive policies was stronger for more educated participants than less educated participants (see Table 4 and Figure 6). The same analyses were conducted while controlling for general meritocracy. All results remained significant except for one, see Table S24 in the Supplemental Material. Overall, out of the 28 models tested in Studies 3a (24 models, 6 different operationalizations × 4 models, see Tables S11–16) and 3b (four models) controlling for general meritocracy belief, belief in school meritocracy or the interaction with degree remained significant in 27 of the 28 tested models. This confirms that school meritocracy findings are not reducible to general meritocracy beliefs. For details, see the Supplemental Material.

Figure 6.

Effect of Beliefs in School Meritocracy as a Function of Educational Degree in Study 3b.

Note. BSM = Belief in School Meritocracy.

We also report multilevel analyses exploring whether the effect of belief in school meritocracy or its interactive effect with educational degree varied as a function of national income inequality (i.e., GINI index), or national educational inequality (i.e., intergenerational mobility index). The pattern of results was similar to Study 3a. Overall, results were identical for both indicators of inequality and they showed that the effect of belief in school meritocracy was stronger on the perception of unfairness of economic inequality whereas the interactive effect with degree was stronger on support for redistributive policies in more economically and educationally egalitarian countries. For more details on the models, see the Supplemental Material, Tables S25–26.

Discussion

Results of Studies 3a and 3b confirmed that belief in school meritocracy was negatively associated with the perception that income inequality is unfair and with lower support for redistributive policies. Moreover, these negative associations were stronger for more educated participants than less educated participants. This moderation by education can be interpreted in different ways. For instance, education could have increased “political sophistication” (i.e., highly educated individuals shape their environment to have it correspond with their political beliefs or personality, see Osborne & Sibley, 2012; van der Heijden & Verkuyten, 2020), which could explain why it strengthens these associations. Alternatively, we believe these results rather suggest that the legitimizing effect of belief in school meritocracy is stronger for “the winners” of this supposed meritocracy. Thus, belief in school meritocracy could serve a twofold legitimizing function: (1) justifying the position individuals occupy in the hierarchy and (2) reaffirming the merit of their high status and the privileges associated with this status (Mijs & Hoy, 2021; Sidanius & Pratto, 2001).

This explanation seems plausible particularly in light of the finding that the interactive effect, when significant, was consistently stronger in more egalitarian countries. It could be that belief in school meritocracy particularly serves a legitimizing function when individuals’ relative advantage is weaker and threatened (i.e., for highly educated individuals who live in more egalitarian countries). In other words, egalitarian contexts may be more threatening to higher-status individuals because they offer little differentiation on the basis of status. Higher-status individuals may therefore embrace belief in school meritocracy more to justify support for a hierarchy in which their status should be recognized as superior and distinct.

General Discussion

Schools’ official task is to develop students’ knowledge and skills, but in the process, schools also convey informal beliefs, norms, and values that shape students and society (Guimond & Palmer, 1990). Arguably, one of the most impactful is the belief in school meritocracy. Because of this belief, we live in a “schooled society” where education is one of the primary sources of social and economic stratification (Baker, 2014).

In this article, we proposed that belief in school meritocracy not only affects students while they are in school, but also affects society at large by shaping attitudes toward social and economic inequality. Specifically, we hypothesized that belief in school meritocracy not only entails believing that processes in schools are fair but also that the differences in life outcomes based on the educational hierarchy are also fair. We presented converging evidence to support this hypothesis, using a wide array of methods (correlational, experimental, and data survey), collected in large, heterogeneous samples. Our four studies provided consistent support for the proposition that belief in school meritocracy is associated with lower perceived unfairness of social and income inequality and lower support for policies aiming at reducing such inequality. Study 2 goes beyond correlational evidence and shows that manipulated levels of school meritocracy causally affect these outcomes. Studies 3a and 3b provide evidence that the effect is generalizable. Importantly, the models used in Studies 3a and 3b (i.e., fixed-effect models) show that it is the belief rather than the actual level of school meritocracy that is associated with the legitimization of income inequality as the comparisons are made within countries (i.e., within the same meritocratic and economic context).

Supplementary analyses show that this effect appears stronger for higher-educated individuals, especially in egalitarian countries. This could suggest that this belief legitimates social and economic inequality particularly when symbolic or material resources are more at stake. An important limitation, however, is that these analyses were exploratory and do not provide causal evidence for a temporal link of a potential legitimizing function. Future panel data studies are needed to confirm the directionality and causality of these effects.

In terms of societal implications, our results suggest that by strengthening attitudes that support social and income inequality the belief in school meritocracy could come at a cost that outlives students’ school years. This insight is important for two reasons. First, by showing the structural level drivers of attitudes toward inequality and policy positions, we advance on work which has studied school meritocracy primarily by showcasing its effect on lower-SES individuals (see also van Noord et al., 2019; Wiederkehr et al., 2015). Indeed, while education is often heralded as the solution to many of society’s problems (Baker, 2014), the less often talked about and darker side to educational institutions is that one of its core functions is to create a hierarchy (Batruch et al., 2019). The objective of this article was to shed light on the way a meritocratic discourse in school is used in wider society not just to legitimize the educational hierarchy, but also to support the maintenance of social and economic inequality at large. Second, even though the finding that the belief in school meritocracy is reinforced and perpetuated by teachers and school staff is disheartening, at the same time, the finding also suggests practical ways forward because this finding highlights how institutional agents can be instrumental in limiting its potential adverse effects (e.g., by promoting a more accurate depiction of schools’ inability to be completely meritocratic). Such insights form promising pathways for intervention.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-spp-10.1177_19485506221111017 for Belief in School Meritocracy and the Legitimization of Social and Income Inequality by Anatolia Batruch, Jolanda Jetten, Herman Van de Werfhorst, Céline Darnon and Fabrizio Butera in Social Psychological and Personality Science

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-spp-10.1177_19485506221111017 for Belief in School Meritocracy and the Legitimization of Social and Income Inequality by Anatolia Batruch, Jolanda Jetten, Herman Van de Werfhorst, Céline Darnon and Fabrizio Butera in Social Psychological and Personality Science

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Christine McCoy for her help on the earlier version of the manuscript.

Author Biographies

Anatolia Batruch is a Junior Lecturer at the University of Lausanne. Her research examines the structural and psychological antecedents as well as the consequences of social class inequality.

Jolanda Jetten is a professor at the University of Queensland. Her research concerns social identity, social groups, and group dynamics.

Herman Van de Werfhorst is a professor at the University of Amsterdam. His work concentrates on the role of institutions for inequalities in and through education.

Céline Darnon is a professor at the Université de Clermont Auvergne. Her research examines how the educational system contributes to reproduce and legitimate class and gender inequalities.

Fabrizio Butera is a professor at the University of Lausanne. His work focuses on social change, from the structural processes founding social influence to the cognitive and motivational mechanisms that determine individual change.

García-Sánchez et al. (2019) label this variable “equality of opportunity beliefs.”

Dependent variables in Studies 3a and 3b had low reliability: (.56 < α < .68). For both Studies 3a and 3b, we therefore tested the effect on each item separately. The effect was significant for seven out of eight of the dependent variables in Study 3a and for five out of the six in Study 3b. Results can be found in the Supplemental Material (Tables S6, S7, S22, and S23). However, as the items were selected a priori, only the results for the aggregated items are presented in the main text.

Handling Editor: Danny Osborne

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by a doctoral fellowship awarded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) to the first author (P1LAP1_164890) and a Vici grant awarded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) to Herman van de Werfhorst (#453-14-017).

ORCID iDs: Anatolia Batruch  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4669-1463

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4669-1463

Céline Darnon  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2613-689X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2613-689X

Supplemental Material: The supplemental material is available in the online version of the article.

References

- Arend M. G., Schäfer T. (2019). Statistical power in two-level models: A tutorial based on Monte Carlo simulation. Psychological Methods, 24(1), 1–19. 10.1037/met0000195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrow K. J. (1973). Higher education as a filter. Journal of Public Economics, 2(3), 193–216. 10.1016/0047-2727(73)90013-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Autin F., Batruch A., Butera F. (2019). The function of selection of assessment leads evaluators to artificially create the social class achievement gap. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(4), 717–735. 10.1037/edu0000307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D. (2014). The schooled society: The educational transformation of global culture (1st ed.). Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barg K. (2013). The influence of students’ social background and parental involvement on teachers’ school track choices: Reasons and consequences. European Sociological Review, 29(3), 565–579. 10.1093/esr/jcr104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batruch A., Autin F., Bataillard F., Butera F. (2019). School selection and the social class divide: How tracking contributes to the reproduction of inequalities. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(3), 477–490. 10.1177/0146167218791804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauvois J.-L., Dubois N. (1988). The norm of internality in the explanation of psychological events. European Journal of Social Psychology, 18(4), 299–316. 10.1002/ejsp.2420180402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beauvois J.-L. (2003). Judgment norms, social utility, and individualism. In Dubois N. (Ed.), A sociocognitive approach to social norms (pp. 123–147). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P., Passeron J.-C. (1990). Reproduction in education, society and culture (2nd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Brown P., Tannock S. (2009). Education, meritocracy and the global war for talent. Journal of Education Policy, 24(4), 377–392. 10.1080/02680930802669938 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski A. K. (2019). The global increase in the socioeconomic achievement gap, 1964 to 2015. American Sociological Review, 84(3), 517–544. 10.1177/0003122419847165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darnon C., Smeding A., Redersdorff S. (2018). Belief in school meritocracy as an ideological barrier to the promotion of equality. European Journal of Social Psychology, 48(4), 523–534. 10.1002/ejsp.2347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darnon C., Wiederkehr V., Dompnier B., Martinot D. (2018). ‘Where there is a will, there is a way’: Belief in school meritocracy and the social-class achievement gap. British Journal of Social Psychology, 57(1), 250–262. 10.1111/bjso.12214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch M. (1979). Education and distributive justice: Some reflections on grading systems. American Psychologist, 34(5), 391–401. 10.1037/0003-066X.34.5.391 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dompnier B., Pansu P., Bressoux P. (2006). An integrative model of scholastic judgments: Pupils’ characteristics, class context, halo effect and internal attributions. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 21, 119–133. 10.1007/BF03173572 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duru-Bellat M., Tenret E. (2012). Who’s for meritocracy? Individual and contextual variations in the faith. Comparative Education Review, 56(2), 223–247. 10.1086/661290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrook M. J., Kuppens T., Manstead A. S. (2016). The education effect: Higher educational qualifications are robustly associated with beneficial personal and socio-political outcomes. Social Indicators Research, 126(3), 1261–1298. 10.1007/s11205-015-0946-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foster M. D., Sloto L., Ruby R. (2006). Responding to discrimination as a function of meritocracy beliefs and personal experiences: Testing the model of shattered assumptions. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 9(3), 401–411. 10.1177/1368430206064641 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez E., Van der Toorn J., Rodríguez-Bailón R., Willis G. B. (2019). The vicious cycle of economic inequality: The role of ideology in shaping the relationship between “what is” and “what ought to be” in 41 countries. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10(8), 991–1001. 10.1177/1948550618811500 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geven S., Wiborg Ø. N., Fish R. E., van de Werfhorst H. G. (2021). How teachers form educational expectations for students: A comparative factorial survey experiment in three institutional contexts. Social Science Research, 100, Article 102599. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2021.102599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Database on Intergenerational Mobility. (2018). Global Database on Intergenerational Mobility. Development Research Group, World Bank. World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Guimond S., Palmer D. L. (1990). Type of academic training and causal attributions for social problems. European Journal of Social Psychology, 20(1), 61–75. 10.1002/ejsp.2420200106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J., Heine S. J., Norenzayan A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83. 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetten J., Schmitt M. T., Branscombe N. R., Garza A. A., Mewse A. J. (2011). Group commitment in the face of discrimination: The role of legitimacy appraisals. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41(1), 116–126. 10.1002/ejsp.743 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jost J. T., Hunyady O. (2005). Antecedents and consequences of system-justifying ideologies. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(5), 260–265. 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00377.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles E. D., Lowery B. S. (2012). Meritocracy, self-concerns, and Whites’ denial of racial inequity. Self and Identity, 11(2), 202–222. 10.1080/15298868.2010.542015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus M. W., Stephens N. M. (2012). A road map for an emerging psychology of social class. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(9), 642–656. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00453.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens T., Spears R., Manstead A. S., Spruyt B., Easterbrook M. J. (2018). Educationism and the irony of meritocracy: Negative attitudes of higher educated people towards the less educated. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 429–447. 10.1016/j.jesp.2017.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madeira A. F., Costa-Lopes R., Dovidio J. F., Freitas G., Mascarenhas M. F. (2019). Primes and consequences: A systematic review of meritocracy in intergroup relations. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, Article 2007. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy S. K., Major B. (2007). Priming meritocracy and the psychological justification of inequality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(3), 341–351. 10.1016/j.jesp.2006.04.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy S. K., Wellman J. D., Cosley B., Saslow L., Epel E. (2013). Is the belief in meritocracy palliative for members of low status groups? Evidence for a benefit for self-esteem and physical health via perceived control. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43(4), 307–318. 10.1002/ejsp.1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mijs J. J. B. (2016). The unfulfillable promise of meritocracy: Three lessons and their implications for justice in education. Social Justice Research, 29, 14–34. 10.1007/s11211-014-0228-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mijs J. J. B. (2021). The paradox of inequality: Income inequality and belief in meritocracy go hand in hand. Socio-Economic Review, 19(1), 7–35. 10.1093/ser/mwy051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mijs J. J. B., Hoy C. (2021). How information about inequality impacts belief in meritocracy: Evidence from a randomized survey experiment in Australia, Indonesia and Mexico. Social Problems, 69(1), 91–122. 10.1093/socpro/spaa059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2014). Indicator A4: To what extent does parents’ education influence participation in tertiary education? In Education at a glance 2014: OECD indicators. 10.1787/888933115521 [DOI]

- Osborne D., Sengupta N. K., Sibley C. G. (2019). System justification theory at 25: Evaluating a paradigm shift in psychology and looking towards the future. British Journal of Social Psychology, 58(2), 340–361. 10.1111/bjso.12302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne D., Sibley C. G. (2012). Does personality matter? Openness correlates with vote choice, but particularly for politically sophisticated voters. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(6), 743–751. 10.1016/j.jrp.2012.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pansu P., Dubois N., Dompnier B. (2008). Internality-norm theory in educational contexts. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 23, 385–397. 10.1007/BF03172748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roex K. L., Huijts T., Sieben I. (2019). Attitudes towards income inequality: “Winners” versus “losers” of the perceived meritocracy. Acta Sociologica, 62(1), 47–63. 10.1177/0001699317748340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal L., Levy S. R., Moyer A. (2011). Protestant work ethic’s relation to intergroup and policy attitudes: A meta-analytic review. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 874–885. 10.1002/ejsp.832 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N., Todd A. R., Bodenhausen G. V., Corrigan P. W. (2010). Do people with mental illness deserve what they get? Links between meritocratic worldviews and implicit versus explicit stigma. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 260(8), 617–625. 10.1177/0146167202282006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt M. T., Branscombe N. R., Kobrynowicz D., Owen S. (2002). Perceiving discrimination against one’s gender group has different implications for well-being in women and men. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 197–210. 10.1177/0146167202282006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius J., Pratto F. (2001). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Son Hing L. S., Bobocel D. R., Zanna M. P., Garcia D. M., Gee S. S., Orazietti K. (2011). The merit of meritocracy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(3), 433–450. 10.1037/a0024618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruyt B. (2015). Talent, effort or social background? An empirical assessment of popular explanations for educational outcomes. European Societies, 17(1), 94–114. https://doi.org/0.1080/14616696.2014.977323 [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans A. C., De Boer H., Amsing H. T. A., van der Werf M. P. C. (2018). Track recommendation bias: Gender, migration background and SES bias over a 20-year period in the Dutch context. British Educational Research Journal, 44(5), 847–874. 10.1002/berj.3470 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trautwein U., Lüdtke O., Köller O., Baumert J. (2006). Self-esteem, academic self-concept, and achievement: How the learning environment moderates the dynamics of self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(2), 334–349. 10.1037/0022-3514.90.2.334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR/Pages/Language.aspx?LangID=eng

- van der Heijden E., Verkuyten M. (2020). Educational attainment, political sophistication and anti-immigrant attitudes. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 8(2), 600–616. 10.5964/jspp.v8i2.1334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van de Werfhorst H. G., Mijs J. J. B. (2010). Achievement inequality and the institutional structure of educational systems: A comparative perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 407–428. 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102538 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Noord J., Spruyt B., Kuppens T., Spears R. (2019). Education-based status in comparative perspective: The legitimization of education as a basis for social stratification. Social Forces, 98(2), 649–676. 10.1093/sf/soz012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Zomeren M., Spears R., Leach C. W. (2008). Exploring psychological mechanisms of collective action: Does relevance of group identity influence how people cope with collective disadvantage? British Journal of Social Psychology, 47(2), 353–372. 10.1348/014466607X231091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek M. (2008). A guide to modern econometrics (3rd ed.). John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Wiederkehr V., Bonnot V., Krauth-Gruber S., Darnon C. (2015). Belief in school meritocracy as a system-justifying tool for low status students. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, Article 1053. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-spp-10.1177_19485506221111017 for Belief in School Meritocracy and the Legitimization of Social and Income Inequality by Anatolia Batruch, Jolanda Jetten, Herman Van de Werfhorst, Céline Darnon and Fabrizio Butera in Social Psychological and Personality Science

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-spp-10.1177_19485506221111017 for Belief in School Meritocracy and the Legitimization of Social and Income Inequality by Anatolia Batruch, Jolanda Jetten, Herman Van de Werfhorst, Céline Darnon and Fabrizio Butera in Social Psychological and Personality Science