Abstract

We studied DNA binding of a transcriptional repressor, CopF, displayed on a filamentous phage. Mutagenesis of a putative helix-turn-helix motif of CopF and of certain bases of the operator abolished the protein-DNA interaction, establishing the elements involved in CopF function and showing that phage display can be used to study repressor proteins.

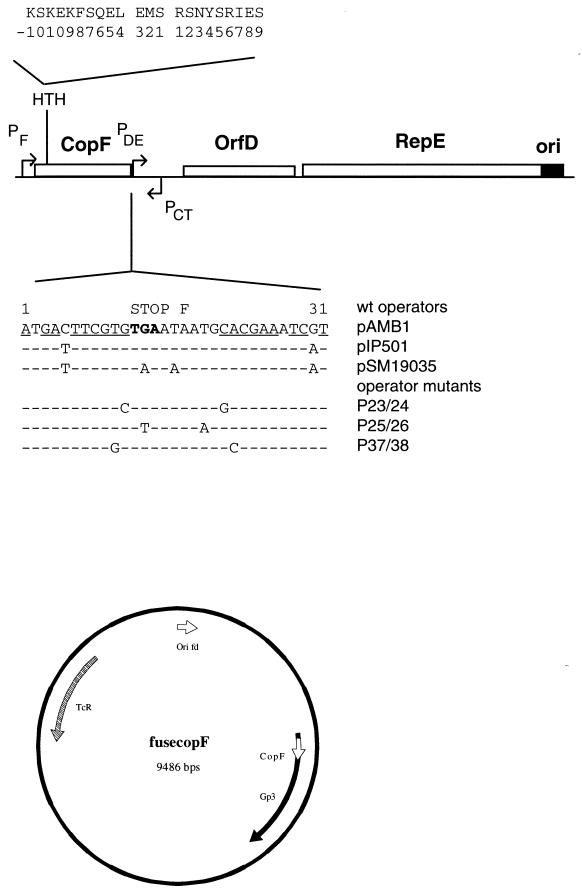

pAMβ1, pIP501, and pSM19035 are members of a family of low-copy-number plasmids isolated from enterococci and streptococci (for a review, see reference 16). The Rep proteins of pAMβ1 and pIP501 are rate limiting for replication (3, 6, 21). Their synthesis is controlled transcriptionally at two levels. The first level is a transcription attenuation system involving a countertranscript RNA (5, 4, 23). The second involves the 10-kDa products of the copF and copR genes. The two proteins bind to an operator sequence located just upstream of the Rep promoters, PDE in pAMβ1 and PII in pIP501, and repress Rep mRNA synthesis approximately 10-fold (2, 22). CopF shares up to 95% identity with CopR of pIP501 and CopS, the corresponding protein of plasmid pSM19035. The DNA binding motifs of the CopF, CopR, and CopS proteins have not been characterized. However, there appears to be a significant probability that a helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif can form within the region of the CopF protein delimited by residues at positions 16 and 37 (22) (Fig. 1). This region is strictly conserved in CopR and CopS proteins. Sequence alignment of the operator regions of pIP501 and pSM19035 with that of pAMβ1 shows that the three operators are highly conserved (Fig. 1) and that all contain an imperfect inverted repeat of 11 bp. Chemical footprint analysis of a His-tagged CopR protein from pIP501 has shown that it contacts two partially symmetric sites in the major groove of DNA, C8GTGT12 on the top strand and CGTGC on the bottom strand (the numbers refer to positions within the operator [31]). This protein was shown to interact cooperatively with the operator probe and to bind to DNA as a dimer, with a dissociation constant (KD) of 4 × 10−10 M (31, 32). Here we present evidence for the involvement of an HTH motif in CopF binding to the operator and report information concerning contacted nucleotides. These results were obtained by phage display of CopF followed by in vitro study of the interaction.

FIG. 1.

(Top) Minimal replication region of pAMβ1. Open boxes denote the three ORFs (CopF, D [of unknown function], and RepE), and the black box indicates the replication origin. Promoters are indicated with arrows. The sequence of the putative HTH motif found at position 16 of the CopF sequence is given at the top of the scheme. Below the scheme is presented the 31-bp operator sequence which spans the end of the CopF ORF just upstream from PDE. The 11-bp imperfect inverted repeats are underlined. The base positions which differ from those of the pAMβ1 operator in pIP501 and pSM19035 are indicated as are the sequences of mutant operators tested in the present report. (Bottom) Scheme of the fusecopF genome. copF has been cloned as a translational fusion with the fd minor coat protein Gp3 in fuse 5, a phage fd derivative bearing the Tn10 tetracycline resistance gene. Ori, origin of replication.

To obtain phages bearing the CopF repressor (designated fusecopF), a BglI PCR fragment containing the copF open reading frame (ORF) was cloned into the polyvalent phage display vector fuse 5 (29), cut by SfiI, as a translation fusion with Gp3. The PCR fragment was obtained using plasmid pTB19F (22) as the template with primers ACGAATCAGCCAACGGGGCTTTGGAACTAGCATTTAGA and TACCAATGGCCTCAGCGGCCACGAAGTCATTGCTTTT. Phages were propagated on Escherichia coli strain MC1061 Lambda wt (7), concentrated by precipitation with polyethylene glycol 6000, and either purified by CsCl gradient centrifugation or dialyzed against Tris-EDTA buffer. Phage concentrations were determined by Western blotting using anti-f1 antibodies. Binding reactions were carried out in a final volume of 50 μl containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, labeled DNA, and phages as indicated in the legends of the figures. After 10 min at room temperature, DNA-phage complexes were filtered on nitrocellulose (Schleicher and Schull) and filters were washed three times with 1 ml of the same buffer. Radioactivity fixed on filters reflects the binding activities of phages. fusecopF-uracylated single-stranded DNA was prepared according to the method of reference 20, using strain BW313 (19). Mutagenesis of CopF was carried out using degenerated oligonucleotides as primers for T7 polymerase. The elongation mixture was used for electrotransformation of E. coli MC1061 Lambda wt competent cells.

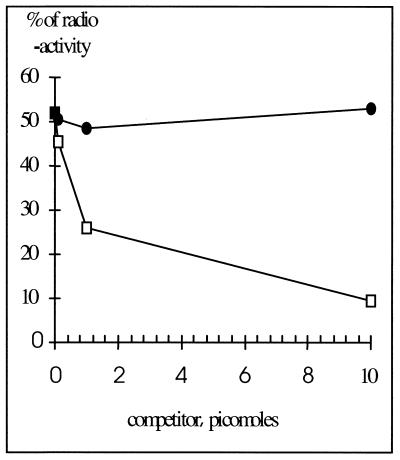

CopF repressor was displayed on M13 phage as a fusion protein with the minor coat protein Gp3 in the polyvalent phage display vector fuse 5 (29). Phage bearing CopF, denoted fusecopF (Fig. 1), was tested for affinity with the minimal-size operator (31-bp, pAMβ1 operator depicted in Fig. 1). Some 52% of the labeled operator was bound to the phage in the absence of the nonlabeled operator (Fig. 2). This amount decreased progressively with increasing amounts of the unlabeled operator fragment but not of a control competitor fragment lacking the operator (a 33-bp DNA fragment corresponding to a part of the plasmid pT181 replication origin [18]). Similar results were obtained with a 238-bp pAMβ1 DNA fragment containing the operator, where 22 to 32% of the fragment was bound to fusecopF phage while 4% of the control fragment lacking the operator was bound. Furthermore, the phage lacking CopF bound <4% of either fragment. This result shows that fusecopF interacts with the minimal-size operator in a sequence-specific manner.

FIG. 2.

Competition experiments. Increasing amounts of cold competitor were added to the labeled operator target in binding reactions with fusecopF. Reaction mixtures containing Tris-HCl (pH 7.5, 10 mM), NaCl (100 mM), the labeled 31-bp operator (1.2 × 10−9 M), and phages (1.6 × 10−8 M) were incubated for 10 min at room temperature before filtering of DNA-protein complexes and counting of radioactivity. The percentage of radioactivity bound to the filters is plotted as a function of competitor amount. Squares, 31-bp operator competitor; circles, 34-bp control segment lacking the operator.

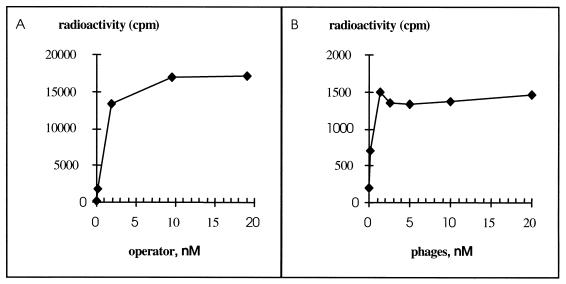

The apparent KD of phage-displayed CopF was determined using the formula KD = [OT]1/2 − 1/2[RT], where [OT]1/2 is the total operator concentration at which half of the repressor is bound and [RT] is the total repressor concentration (27). In order to estimate the [OT]1/2, increasing amounts of DNA were incubated with phages at a fixed concentration (Fig. 3A). [OT]1/2 was 6.5 × 10−10 M. [RT] was estimated as follows. Assuming that each complex contains one phage only, the concentration of active phage should be equal to the maximal concentration of complex formed in the experiment, that is, at the plateau of the curve (Fig. 3A), which corresponds to about 16,000 cpm. A conversion factor between radioactivity and molarity of complex was determined experimentally (Fig. 3B). At the plateau of this curve all DNA molecules are saturated with repressor, so the concentration of complexes should be equal to the molarity of the DNA. The deduced concentration of phage active for binding is equal to 6.5 × 10−10 M and represents 65% of the phage particles used in the assay. A KD of 3.25 × 10−10 M was determined in the experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 3, and an average value of 3.37 × 10−10 M was deduced from two independent experiments, close to that reported for His-tagged CopR (4 × 10−10 M [32]).

FIG. 3.

Determination of KD. (A) Titration curve of phages with DNA. Binding reactions were carried out with increasing amounts of the labeled operator target and a constant phage concentration (10−9 M). The operator concentration at which half of the phages are complexed ([OT]1/2) corresponds to 6.5 × 10−10 M. (B) Titration curve of DNA by phages. Binding reactions were carried out with increasing amounts of phages at a constant DNA concentration (5.7 × 10−11 M). At the plateau, the concentration of DNA-protein complexes is 5.7 × 10−11 M and corresponds to an activity of 1,400 cpm. The concentration of phage active for binding the 31-bp target, [RT], can be deduced from the curve in panel A. The plateau at which all active phages are complexed to DNA corresponds to an activity of 16,000 cpm, equivalent to 11.4 × 10−11 to 5.7 × 10−11 M, that is, 6.5 × 10−10 M. So KD deduced from this experiment corresponds to 3.25 × 10−10 M.

We tested whether the putative HTH motif can be isolated as an independent protein domain. For this purpose, the 54 N-terminal amino acids of CopF, which encompass the motif, were fused to Gp3. The 40 C-terminal amino acids were also fused to Gp3, as a control. Interaction with the 31-bp operator was measured by a filter binding assay with the resulting phages, and results were compared with those for fusecopF. No binding was found with either the amino-end fusion (3% of the fusecopF binding activity) or the carboxyl-end fusion (4.3% of the fusecopF binding activity, with the background representing 3.4%). This result indicates that the interaction requires the whole protein. To investigate the involvement of the putative HTH motif of CopF in protein-DNA interaction directly, a mutagenesis of the motif and the operator was therefore carried out.

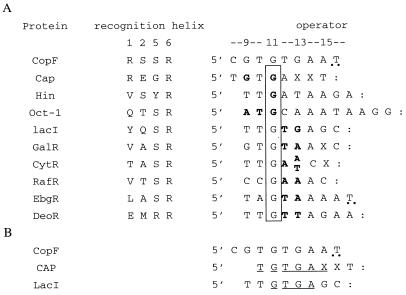

Comparisons of crystal or nuclear magnetic resonance structures of complexes between seven different HTH proteins and their DNA binding sites (434R, 434C, LacI, Lambda R, catabolite gene activator protein [CAP], Hin, and Oct-1) have led Suzuki et al. (34) to propose that amino acids at positions 1, 2, 5, and 6 of the DNA-contacting alpha helix are often involved in specific interaction with a set of one to four consecutive bases within a half-operator sequence, while amino acids at positions −1 and 9 of the recognition helix often contact phosphates. Among these proteins (Fig. 4), four possess an arginine at position 6 of their recognition helix, which interacts with a guanine in the operator (LacI [9, 26], CAP [28, 10, 13, 14], Oct-1 [17], and Hin [15]). Furthermore, at least five prokaryotic repressors homologous to the Lac repressor have an arginine at position 6 of their recognition helix, which may be predicted to interact with a G in their operator (24): GalR (37), CytR (36), RafR (1), EbgR (33), and DeoR (35). These nine operators can be aligned with respect to this G (Fig. 4), which is presumably critical for binding, since its change to A, C, or T leads to derepression of PLac in vivo while its change to A or C abolishes binding of CAP to its target (25, 28). Additional interactions between recognition helix amino acid 1 and 2 side chains and base positions (Fig. 4) are in great part responsible for specific recognition by each repressor of the cognate operator. Indeed, the specificity of LacI can be changed to that of any of the above-named LacI family repressors by replacement of the corresponding amino acids at positions 1 and 2 of the recognition helix and of the two bases located 3′ to the crucial G (24).

FIG. 4.

Recognition helices and consensus operators of HTH proteins having at position 6 of their recognition helix an arginine, which was shown or predicted to interact with a G. (A) Amino acid sequences of CAP (28, 10, 13, 14), Hin (15), Oct-1 (18), LacI (25, 14, 26), GalR (37), CytR (36), RafR ( 1), EbgR (33), and DeoR (35) and nucleotide sequences of their operators. The operators have been aligned according to the G known to interact with R at position 6 of the recognition helix in CAP, Hin, Oct-1, and LacI and predicted to do so in other LacI family repressors (24). This key G is boxed, and the symmetry center of the operator is shown by two dots. In bold letters are indicated base positions (on the 5′-to-3′ DNA strand or the opposite) that interact with amino acid positions 1 and 2 of the recognition helix. The putative recognition helix of CopF as well as the part of its operator homologous to that of CAP or LacI is indicated. (B) Sequence alignment of the CopF operator with that of CAP and LacI. Underlined positions are conserved.

CopF possesses two arginines at positions 1 and 6 of its putative recognition helix, and its operator contains four guanines in its left half (Fig. 4A). Moreover, the CopF operator shares 5 bp of sequence (Fig. 4B) with CAP and the LacI operator, spanning base pairs involved in specificity (Fig. 4A). The alignment of the CopF operator with that of CAP or LacI suggests that guanine 13 or 11 may be involved in binding to Arg6. In order to test the involvement of the putative CopF HTH and operator motifs in binding, substitutions of arginines 1 and 6, serine 5, and guanines 13 and 11 were carried out. An operator variant, containing a mutation known to affect the copy number of plasmid pAMβ1 in vivo (a transversion from thymine to guanine at position 10) was also tested.

Two mutant phages were obtained after mutagenesis at position 1, containing Leu or Ile, and three were obtained after mutagenesis at position 6, two having Pro and one having Gln. These phages showed no significant binding to the operator (Table 1). Out of three mutant phages at position 5, two carrying Gln or Pro did not bind the operator while the third, carrying Thr, could bind only inefficiently. This shows that seven different mutations targeted to the putative recognition helix affect binding of CopF to the wild-type (wt) operator, by affecting either HTH formation (the probability is indicated in Table 1) or the binding specificity.

TABLE 1.

Effect of amino acid replacement at positions 1, 5, and 6 of the putative recognition helix on the binding activity of CopF to the 31-bp wt operator

| Amino acid at recognition helix position:

|

% Residual activity with the mutant/that with the wta | % Probabilityb of HTH formation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 6 | ||

| Ile | 15.8 | 25 | ||

| Leu | 15.3 | 25 | ||

| Arg | 100 | 71 | ||

| Gln | 11.6 | 50 | ||

| Pro | 14.9 | 25 | ||

| Thr | 24.1 | 25 | ||

| Ser | 100 | 71 | ||

| Gln | 14.8 | 50 | ||

| Pro | 11.9 | 0 | ||

| Arg | 100 | 71 | ||

Phages bearing mutant CopF were prepared and tested by a filter binding assay with labeled operator. Residual activity corresponds to the ratio of the radioactivity bound by the phage displaying the mutant relative to that of the phage displaying the wt protein. In this experiment, the background radioactivitiy in control reaction mixtures free of phages corresponded to 11.5% of the radioactivity found with the phage carrying the wt protein.

The probability of HTH motif formation in mutant CopF protein is given according to the method of Dodd and Egans (11).

Since arginines 1 and 6 of the recognition helix appear to be involved in binding, we tested whether the guanosines with which they were predicted to interact were also important for binding. Three operator variants were synthesized for this purpose (Fig. 1). In the first (P23/24) G11 was replaced by C. Simultaneously, C21, which is placed symmetrically to G11 relative to the operator center, was replaced by G. In this way, both putative half-operator sites were modified, in order to avoid a possible residual interaction with CopF due to a functional half-site. In the second (P25/26), G13 was replaced by T and the symmetrical T19 was changed to A. The third (P37/38) contained the mutation T10 to G, known to affect the copy number of pAMβ1 in vivo (30) and a symmetrical change, A22 to C. The binding activities of the three operator variants were compared to that of the wt operator and a control 33-bp fragment lacking the operator (P1/OC1). CopF did not bind operators P23/24 and P37/38 (about 2% of the wt operator, similar to the level of binding of the control fragment). Operator P25/26 was only partially inactivated, since it kept about 30% of the wt operator activity. These data suggest that nucleotides T10 and G11 are critical for binding but that G13 is not. Involvement of T10 and G11 and the symmetrical nucleotides in binding of CopF to its target is in agreement with the fact that the homologous CopR protein of pIP501 protects the CGTGT motif, stretching from positions 7 to 12, against chemical attack (31). It should be noted that the G13-to-A change does not abolish CopF binding in vivo, since the copy number of a pSM19035 derivative with copS deleted can be decreased by the CopF protein expressed in trans (22). In this plasmid, three other operator positions, C5, T16, and G30, differ from those of pAMβ1, which indicates that all of them are not critical for CopF binding.

This work demonstrates the feasibility of displaying a functional HTH structure on a filamentous phage. Interestingly, CopF, which is an intracellular protein, was exported on phages efficiently, since up to 65% of the phages were active for binding. Such efficient exportation may be due to a relatively small size of CopF (94 amino acids). Most HTH proteins bind DNA as dimers, and the homologous protein CopR from pIP501 does so (32). This suggests that CopF can dimerize when it is displayed on phage, a conclusion supported by the tightness of the binding, similar to that reported for a His-tagged CopR dimer (32). This tightness of binding may be due to a polyvalent phage display or to the fact that the Gp3CopF protein fusion dimerizes before assembling into the phage coat. Whatever the reason, the possibility of displaying a functional HTH structure on a phage should facilitate studies of the rules governing the interaction between it and its DNA target, mainly by allowing easy isolation and testing of numerous protein variants. Such studies have led previously to establishing a basic interaction code between a zinc finger structure and its target (see reference 12 for a review).

We used phage display to study the interaction of CopF with its operator target. There was no previous experimental evidence for the presence of an HTH structure on the protein, although computer analysis suggested a reasonable probability that such a motif exists (22). We show here that seven different amino acid substitutions clustered in the putative HTH motif disrupt the CopF-operator interaction. These substitutions were targeted to arginines at position 1 and 6 of the putative recognition helix and to serine at position 5. These results support the involvement of the HTH motif in binding to DNA. Furthermore, conservation of the binding site seems to be a feature of HTH proteins (38). A DNA recognition box, TNTNAN, has been proposed for these proteins (12). This box is contained in the CopF operator (TGTGAA). Taken together, these results lead us to propose that an HTH structure can indeed form on CopF and that it mediates CopF binding to its operator. Substitution of the first two bases of the TGTGA motif abolishes the interaction, while replacement of the second G (position 13 of the operator; see Fig. 1) only weakens the binding. Because Arg in the HTH motifs of several repressors is known to interacts with a G, it is tempting to speculate that in CopF, Arg6 interacts with G11. However, this conclusion should be considered preliminary, since it is supported by negative evidence only and should be confirmed, for instance, by the finding of CopF variants able to interact with a mutant operator containing a G11. Such study could be undertaken by using a phage display approach.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aslanidis C, Schmitt R. Regulatory elements of the raffinose operon: nucleotide sequences of operator and repressor genes. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2178–2180. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.4.2178-2180.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brantl S. The copR gene product of plasmid pIP501 acts as a transcriptional repressor at the essential repR promoter. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:473–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb02182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brantl S, Behnke D. The amount of RepR protein determines the copy number of plasmid pIP501 in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5475–5478. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5475-5478.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brantl S, Wagner E G. Antisense RNA-mediated transcriptional attenuation occurs faster than stable antisense/target RNA pairing: an in vitro study of plasmid pIP501. EMBO J. 1994;13:3599–3607. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06667.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brantl S, Birch-Hirschfeld E, Behnke D. RepR protein expression on plasmid pIP501 is controlled by an antisense RNA-mediated transcription attenuation mechanism. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4052–4061. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.4052-4061.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruand C, Le Chatelier E, Ehrlich S D, Jannière L. A fourth class of theta-replicating plasmids: the pAMβ1 family from Gram-positive bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11668–11672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casadaban M, Cohen S N. Analysis of gene control signals by DNA fusion and cloning in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1980;138:179–207. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choo Y, Klug A. Physical basis of a protein-DNA recognition code. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuprina V P, Rullmann J A C, Lamerichs R M J N, van Boom J H, Boelens R, Kaptein R. Structure of the complex of lac repressor headpiece and an 11 base-pair half operator determined by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and restrained molecular dynamics. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:446–462. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Combrugghe B, Busby S, Buc H. Cyclic AMP receptor protein: role in transcription activation. Science. 1984;224:831–838. doi: 10.1126/science.6372090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dodd I B, Egans J B. Improved detection of helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motifs in protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5019–5026. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.17.5019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebright R H. Proposed amino acid-base pair contacts for 13 sequence-specific DNA binding proteins. In: Oxender D L, editor. Protein structure, folding, and design. A. R. New York, N.Y: Liss; 1986. pp. 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebright R H, Cossart P, Gicquel-Sanzey B, Beckwith J. Mutations that alter DNA sequence specificity of the catabolite gene activator protein of E. coli. Nature. 1984;311:232–235. doi: 10.1038/311232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebright R H, Kolb A, Buc H, Kunkel T A, Kradow J S, Beckwith J. Role of glutamic acid-181 in DNA-sequence recognition by the catabolite activator protein (CAP) of Escherichia coli: altered DNA-sequence-recognition properties of [Val181]CAP and [Leu181]CAP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6083–6087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.17.6083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng J A, Johnson R C, Dickerson R E. Hin recombinase bound to DNA: the origin of specificity in major and minor groove interactions. Science. 1994;263:348–355. doi: 10.1126/science.8278807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jannière L, Gruss A, Ehrlich S D. Plasmids. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J A, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria: biochemistry, physiology and molecular genetics. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 625–644. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klemm J D, Rould M A, Aurora R, Herr W, Pabo C O. Crystal structure of the Oct-1 POU domain bound to an octamer site: DNA recognition with tethered DNA-binding modules. Cell. 1994;77:21–32. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koepsel R R, Murray R W, Kahn S A. Sequence-specific interaction between the replication initiator protein of pT181 and its origin of replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5484–5488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.15.5484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kunkel T A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:488–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunkel T A, Bebenek K, McClary J. Efficient site-directed mutagenesis using uracil-containing DNA. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:125–139. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Chatelier E, Ehrlich S D, Jannière L. Biochemical and genetic analysis of the unidirectional theta replication of the S. agalactiae plasmid pIP501. Plasmid. 1993;29:50–56. doi: 10.1006/plas.1993.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le Chatelier E, Ehrlich S D, Jannière L. The pAMβ1 CopF repressor regulates plasmid copy number by controlling transcription of the repE gene. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:463–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb02181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Chatelier E, Ehrlich S D, Jannière L. Countertranscript-driven attenuation system of the pAMβ1 repE gene. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:1099–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehming N, Sartorius J, Kisters-Woike B, von Wilcken-Bergmann B, Müller-Hill B. Mutant lac repressors with new specificities hint at rules for protein-DNA recognition. EMBO J. 1990;9:615–621. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehming N, Sartorius J, Oehler S, von Wilcken-Bergmann B, Müller-Hill B. Recognition helices of lac and Lambda repressor are oriented in opposite directions and recognize similar DNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7947–7951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewiss M, Chang G, Horton N C, Kercher M A, Pace H C, Schumacher M A, Brennan R G, Lu P. Crystal structure of the lactose operon repressor and its complexes with DNA and inducer. Science. 1996;271:1247–1254. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5253.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riggs A D, Suzuki H, Bourgeois S. Lac repressor-operator interaction. J Mol Biol. 1970;48:67–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schutz S C, Shields G C, Steitz T. Crystal structure of a CAP-DNA complex: the DNA is bent by 90°. Science. 1991;253:1001–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1653449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott J K, Smith G. Searching for peptide ligands with an epitope library. Science. 1990;249:386–390. doi: 10.1126/science.1696028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seegers J F. Use of continuous culture for the selection of plasmids with improved segregational stability. Plasmid. 1995;33:71–77. doi: 10.1006/plas.1995.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinmetzer K, Brantl S. Plasmid pIP501 encoded transcriptional repressor CopR binds asymmetrically to two consecutive major grooves of DNA. J Mol Biol. 1997;269:684–693. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinmetzer K, Behlke J, Brantl S. Plasmid pIP501 encoded transcriptional repressor copR binds to its target DNA as a dimer. J Mol Biol. 1998;283:595–603. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stokes H W, Hall B. Sequence of the ebgR gene of Escherichia coli: evidence that the EBG and LAC operon are descended from a common ancestor. Mol Biol Evol. 1985;2:478–483. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki M, Yagi N, Gerstein M. DNA recognition and superstructure formation by helix-turn-helix proteins. Protein Eng. 1995;8:329–338. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.4.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valentin-Hansen P, Hojrup P, Short S A. The primary structure of the DeoR repressor from Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:5927–5937. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.16.5927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valentin-Hansen P, Larsen J E L, Hojrup P, Short S A, Barbier C S. Nucleotide sequence of the CytR regulatory gene of E. coli K12. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:2215–2229. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.5.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Von Wilcken-Bergmann B, Müller-Hill B. Sequence of galR gene indicates a common evolutionary origin of lac and gal repressor in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:2427–2431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.8.2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weickert M J, Adhya S. A family of regulators homologous to Gal and Lac repressors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15869–15874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]