Abstract

Objectives:

Bacteremia due to invasive Salmonella enterica has been reported earlier in children in Nigeria. This study aimed to detect the virulence and antibiotic resistance genes of invasive Salmonella enterica from children with bacteremia in north-central Nigeria.

Method:

From June 2015 to June 2018, 4163 blood cultures yielded 83 Salmonella isolates. This is a secondary cross-sectional analysis of the Salmonella isolates. The Salmonella enterica were isolated and identified using standard bacteriology protocol. Biochemical identifications of the Salmonella enterica were made by Phoenix MD 50 identification system. Further identification and confirmation were done with polyvalent antisera O and invA gene. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was done following clinical and laboratory standard institute guidelines. Resistant genes and virulence genes were determined using a real-time polymerase chain reaction.

Result:

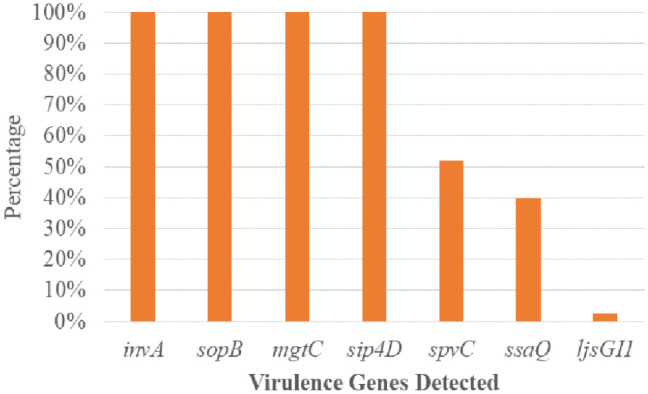

Salmonella typhi 51 (61.4%) was the most prevalent serovar, followed by Salmonella species 13 (15.7%), choleraesuis 8 (9.6%), enteritidis 6 (7.2%), and typhimurium 5 (6.1%). Fifty-one (61.4%) of 83 Salmonella enterica were typhoidal, while 32 (38.6%) were not. Sixty-five (78.3%) of the 83 Salmonella enterica isolates were resistant to ampicillin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, followed by chloramphenicol 39 (46.7%), tetracycline 41 (41.4%), piperacillin 33 (33.9%), amoxicillin-clavulanate, and streptomycin 21 (25.3%), while cephalothin was 19 (22.9%). Thirty-nine (46.9%) of the 83 Salmonella enterica isolates were multi-drug resistant, and none were extensive drug resistant or pan-drug resistant. A blaTEM 42 (50.6%), floR 32 (38.6%), qnrA 24 (28.9%), tetB 20 (20.1%), tetA 10 (10.0%), and tetG 5 (6.0%) were the antibiotic resistance genes detected. There were perfect agreement between phenotypic and genotypic detection of antimicrobial resistance in tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and chloramphenicol, while beta-lactam showed κ = 0.60 agreement. All of the Salmonella enterica isolates had the virulence genes invA, sopB, mgtC, and sip4D, while 33 (39.8%), 45 (51.8%), and 2 (2.4%) had ssaQ, spvC, and ljsGI-1, respectively.

Conclusion:

Our findings showed multi-drug resistant Salmonella enterica in children with bacteremia in northern Nigeria. In addition, significant virulence and antimicrobial resistance genes were found in invasive Salmonella enterica in northern Nigeria. Thus, our study emphasizes the need to monitor antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella enterica from invasive sources in Nigeria and supports antibiotic prudence.

Keywords: Salmonella typhi, non-typhoidal Salmonella, northern Nigeria, antibiotic resistance, bacteremia

Introduction

The type of infection that results from Salmonella enterica is determined by the virulence factors of the bacterium and the host’s factors.1–3Salmonella infection could manifest clinically as gastroenteritis (diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and fever) or a fatal febrile systemic infection (typhoid) that needs to be treated with antibiotics.4–7 Focal conditions and asymptomatic carriers are possible and are significant sources of continued infection transmission. 8 Salmonella is a gram-negative, flagellated, with O, H, and Vi antigens. More than 1800 Salmonella serovars are known.2,9Salmonellae infection is possible when the bacteria gets through the gastric acid barrier, into the mucosa of the small and large intestines, and makes toxins. 10 Invasion of the epithelial cells causes the release of cytokines that cause inflammation. 11 It results in diarrhea, leading to ulceration and the destruction of mucosal cells. Also, if this spread in the intestines persists, it could result in systemic infection. 11

Horizontal gene transfers shape bacterial genomic diversity. 12 Some pathogens have genomic islands or islets (GI) with functionally linked genes.13,14Salmonella pathogenic islands (SPIs) contain virulence genes, distinguishing them from nonpathogenic types.15–18 Virulence factors determine a host’s pathogenicity. 19 The adhesion and invasion of host cells by pathogenic S. enterica are aided by pef, spv, invA, and fim genes, respectively. Magnesium transport C (mgtC), Salmonella toxin (stn), and pip A, B, and D help the bacterium survive in the host system.20,21

The burden of invasive bloodstream infection due to S. enterica is increasing, especially in developing countries. 5 Globally, 1.2 million deaths attributable to S. enterica are recorded annually, with the vast majority occurring in resource-limited countries. 22 In resource-limited countries, non-typhoidal Salmonella infections cause bacteremia in immune-compromised and malnourished adults and children. 16 Most morality from Salmonella infection is connected to poor diagnostic infrastructures leading to misdiagnosis and drug misuse. 23 It is established that most pathogenic bacteria are acquired from the environment, food, and water sources.24,25 Although typhoidal Salmonella is a human host-adapted strain, recent literature has found typhoidal Salmonella in the food chain and water sources.26–30

The worldwide rise of multi-drug resistance is a major health concern. 31 It is becoming increasingly important to routinely apply antimicrobial susceptibility testing to select the antibiotic of choice and to screen for emerging multi-drug resistant (MDR) strains, 32 as several recent studies have reported the emergence of multi-drug resistant Salmonella pathogens from various origins, including humans, 33 birds, 34 cattle, 31 and fish. 35

Pathogens’ high antimicrobial resistance has been attributed to antimicrobial misuse in human and animal husbandry.36–39 Comparative genomic data from invasive Salmonella data and those from the environment and food chain have shown relatedness between clinical isolates and other sources.10,11,40 It has caused great concern as clinical S. enterica are resistant to the commonly used antibiotic, and some have been found to harbor extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) genes which could make treatment difficult.41–46 Recent data from surveillance has found non-typhoidal Salmonellae to be highly resistant to antimicrobials.4,47–49 Thus, clinical care for individuals with invasive Salmonella infection is expensive, increases their hospital stay, and burdens them financially.50,51 Studies have been carried out on Salmonella virulence factors, but information on invasive isolates is scarce, especially from the pediatric population. This study aims to investigate the virulence and antimicrobial resistance genes pattern of S. enterica from invasive bloodstream infection in children from north-central Nigeria.

Materials and methods

Study design

This is a secondary cross-sectional analysis of isolated S. enterica in children with bloodstream infection in the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) and Nasarawa State, Nigeria.

Collection of Salmonella isolates analyzed in the study

Eighty-three gram-negative bacilli isolates were collected from blood cultures recovered from the study conducted at seven hospitals in FCT and Nasarawa State, Nigeria. Presumptively identified Salmonella isolates from four thousand and sixteen blood cultures were processed from June 2015 to June 2018. The study was part of Community-Acquired Bacteremia Syndrome in Young Nigeria Children conducted in north-central Nigeria from 2008 to 2018 by the International Foundation Against Infectious Diseases in Nigeria. The outcomes from 2008 to 2015 had been previously reported by Obaro et al., 5 and those previously reported isolates were excluded from this study.

Isolation of S. enterica of positive blood culture

Bacterial analysis, including gram staining and biochemical analysis using the analytical profile index (API20E) (Biomerieux, SA Lyon, France), was used to identify the Salmonella pathogens. Obaro et al. 5 have previously described the protocol used to culture and isolate the S. enterica used in this work. Briefly, all positive bottles were subcultured onto MacConkey agar (Oxoid, London, UK) and Salmonella shigella agar (Oxoid) plates and then incubated at 36°C for 24 h. The isolates were frozen at −80°C in 10% skim milk glycerol (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, California, USA) until used. 52 In conducting the study, the previously collected isolates were grown onto S. shigella agar (Oxoid) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. In checking for Salmonella isolates, colonies were looked for on the plates. The morphological traits and characteristics of Salmonella species were selected, and gram staining of the selected colonies from each plate was examined. 52 Biochemical assays, including reactions on triple sugar iron agar, lysine iron agar, indole synthesis in tryptone broth, and urea splitting ability, were then conducted using the Phoenix MD (Beckon-Dickson systems, San Jose, California, USA). Molecular invA gene detection was used to validate the authenticity of the isolates. Polyvalent Salmonella antisera, A-G, A-S surface antigen, flagellar H (phase 1 and phase 2) (Beckon-Dickson systems) according to Kauffman-White Scheme 53 were used in the serotyping of the Salmonella isolates.

By Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing and Multiple Antimicrobial Resistance (MAR) Index according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute recommendations, 54 the antibiotic susceptibility of the isolates was determined. The antibiotic discs (ampicillin (10 μg), amoxicillin-clavulanate (30/10 μg), piperacillin (30 μg), piperacillin-tazobactam (30/10 μg), streptomycin (10 μg), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (10/25 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg), tetracycline (30 μg), aztreonam (30 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), amikacin (30 μg), cephalothin (30 μg), cefuroxime (30 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), cefepime (30 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg), levofloxacin (5 μg), meropenem (10 μg), imipenem (10 μg), tigecycline (25 μg), cefotaxime-clavulanate (30/10 μg), and ceftazidime-clavulanate (30/10 μg) that were utilized in a disk diffusion assay were from Oxoid. The BD PhoenixTM M50 system (Beckon-Dickson systems) was used for minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) testing. For ciprofloxacin, MIC values >0.064 g/mL were viewed as reduced susceptibility, while MIC values 4 g/mL were interpreted as resistant; for azithromycin, MIC values >16 g/mL were interpreted as resistant. According to Davis and Brown, 55 the MAR indexes were derived as the ratio of antibiotics to which resistance was demonstrated to the number of antibiotics for which the isolate was screened for susceptibility. According to Algammal et al., 32 the resistance profiles were classified as MDR, extensive drug resistant (XDR), or pan-drug resistant (PDR).

Molecular detection of resistance and virulence genes

Genomic DNA was extracted using the Maxwell 16-cell DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) on an automated machine (Maxwell 16 extraction system, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). The real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays were performed on the AriaMx system (Agilent Inc., Santa Clara, California, USA). Primers and probes were purchased from LGC, Biosearch (Novato, California, USA) for the different genes based on primers and probes used by Ibrahim et al. 56 for invA; Bugarel Weil et al. 57 for sopB, ssaQ, mgtC, spi4D, spvC, and ljsGI-1; Roschanski et al. 58 for blaTEM, blaSHV; Vien et al. 59 for qnrA; Singh and Mustapha 60 for floR and tetG; and Guarddon et al. 61 for tetA and tetB. Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 show the genes sequences and amplification conditions used. A quality-controlled positive and negative internally characterized known resistant and susceptible Salmonella typhi strains from International Typhoid Consortium 62 were used as controls for amplification for detecting the resistance genes and virulence during PCR. Also, no template controls were incorporated into the PCR as an additional method of internal control in the PCR.

A 12.5 μL of Perfecta master mix low ROX kit (Quanta Bioscience Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA), 1.0 μL of each 10 mM primers and probes, 7.5 μL of Nuclease free water (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA), and 2.0 μL of DNA template make up a 25 μL PCR reaction mixture. Thermal conditions were those described by the referenced authors (Tables 1 and 2). After the amplification experiments were completed, the cycle thresholds were determined by identifying the fluorescence signal by analyzing the amplification plots in AriaMx system software version 3.1.

Table 1.

Identification of Salmonella by API 20E.

| Salmonella ID | Clinical samples n = 83 n (%) |

|---|---|

| Salmonella typhi | 51 (61.4) |

| Salmonella typhimurium | 5 (6.1) |

| Salmonella enteritidis | 6 (7.2) |

| Salmonella choleraesuis | 8 (9.6) |

| Salmonella species | 13 (15.7) |

n: number; %: percentage.

Table 2.

The non-susceptibility pattern between invasive typhoidal and non-typhoidal Salmonellae in the study.

| Classes | Antibiotics | No of positive isolates n = 83 (%) | Salmonella enterica | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typhoidal n = 51 | Non-typhoidal n = 32 | |||||

| Beta-lactams Penicillin First cephalosporin |

Ampicillin* | 65 (78.3) | 44 (86.3) | 21 (65.6) | 0.03 | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate* | 21 (25.3) | 13 (25.5) | 9 (28.1) | 0.79 | ||

| Piperacillin* | 33 (39.8) | 20 (39.2) | 13 (40.6) | 0.41 | ||

| Cephalothin* | 19 (22.9) | 12 (23.5) | 7 (21.9) | 0.86 | ||

| Sulfonamides | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole* | 65 (78.3) | 44 (86.3) | 21 (65.6) | 0.03 | |

| Phenicol | Chloramphenicol* | 39 (46.9) | 22 (43.1) | 17 (53.1) | 0.37 | |

| Tetracycline | Tetracycline* | 41 (49.4) | 33 (64.7) | 8 (25.0) | 0.0004 | |

| Aminoglycosides | Streptomycin* | 21 (25.3) | 10 (19.6) | 11 (34.4) | 0.13 | |

| a Azithromycin (IAS)** | 9 (10.8) | 5 (9.8) | 4 (12.5) | 0.73 | ||

| Fluoroquinolone | b Ciprofloxacin (ICS)* | 24 (28.9) | 16 (31.4) | 8 (25.0) | 0.53 | |

n: number; %: percentage; ICS: intermediate ciprofloxacin susceptibility; IAS: intermediate azithromycin susceptibility. p < 0.05 = statistical significance. p > 0.05 = statistical insignificance.

Chi-square statistic.

Fisher’s exact test.

MIC ciprofloxacin>0.064 µg/mL.

MIC azithromycin >16 µg/mL.

Statistical analysis

Data were imputed and validated in Excel 2016. Descriptive statistics were computed for the multiple antibiotic resistance index. Agreement between the values of antimicrobial resistance phenotypes and their corresponding genotypes was established by κ value (coefficient of agreement) according to Jeamsripong et al. 63 Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test were used to test association as appropriate in every case. p < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant. Statistical Package for Social Science Version 20 (IBM, Santa Barbara, California, USA) was used.

Results

Prevalence and phenotypic characteristics of recovered Salmonella species

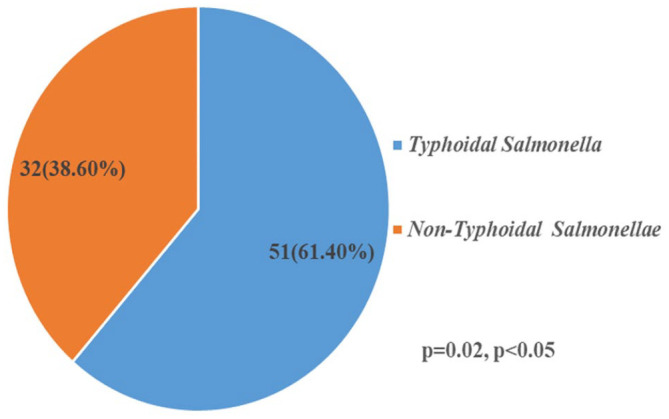

Table 1 shows the Salmonella serovars found in the study, S. typhi 51 (61.4%) was the most occurring serovar, Salmonella typhimurium 5 (6.1%), Salmonella enteritidis 6 (7.2%), Salmonella choleraesuis 8 (9.6%), and Salmonella species 13 (15.7%) were the other identified serovars in this study. Figure 1 showed a statistically significant (p = 0.02) higher typhoidal Salmonellae 51 (61.4%) than non-typhoidal 32 (38.6%) Salmonellae in the study.

Figure 1.

Classification of Salmonella enterica in the study.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing, antibiotic resistance genes outcomes

Table 2 shows the resistance pattern of the Salmonella isolates. Of the 83 S. enterica isolates, 65 (78.3%) were resistant to ampicillin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. A significant (p = 0.03) higher resistance was found in typhoidal Salmonellae 44 (86.3%) compared non-typhoidal Salmonellae 21 (65.6%). Resistance to tetracycline 41 (49.4%) was higher, with a statistically significant difference (p = 0.0004) in typhoidal Salmonellae 33 (64.7%) than in non-typhoidal Salmonellae 8 (25.0%).

Resistance to other antimicrobials was as follows: amoxicillin-clavulanate 21 (25.3%), piperacillin 33 (39.8%), cephalothin 19 (22.9%), chloramphenicol 39 (46.9%), streptomycin 21 (25.3%), azithromycin 9 (10.8%) with no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in typhoidal Salmonellae and non-typhoidal Salmonella in the study. Intermediate ciprofloxacin susceptibility occurred in 24 (28.9%) Salmonella isolates. Also, intermediate azithromycin susceptibility occurred in nine (10.8%) Salmonella isolates.

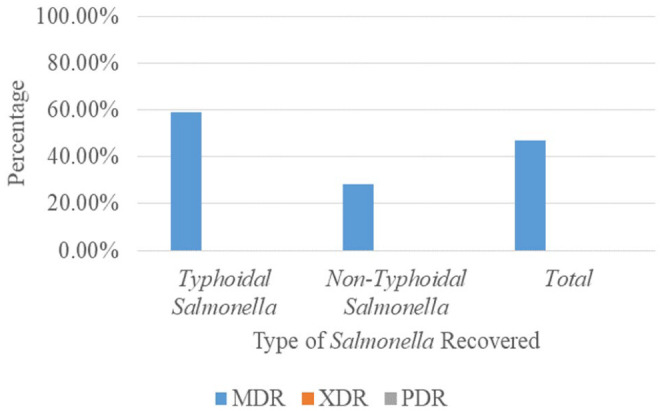

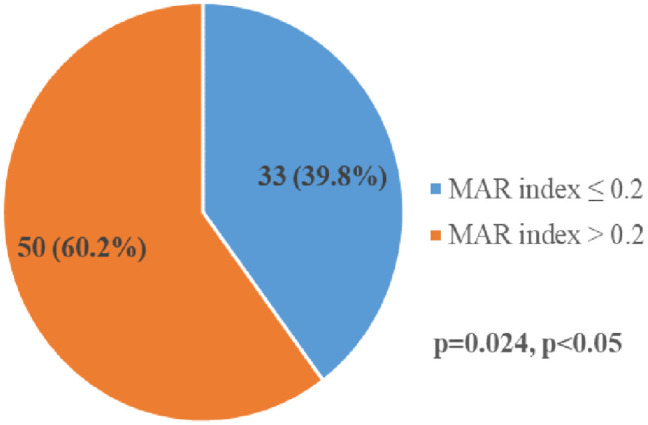

MDR was found in 39 (46.9%) of the 83 S. enterica isolated. Of the 39 S. enterica isolates that demonstrated MDR phenotypically, 30 (58.9%) were typhoidal Salmonellae. In comparison, nine (28.1%) of them were non-typhoidal Salmonellae. No XDR and PDR were observed in the study, as shown in Figure 2. Figure 3 shows the MAR indexes of the Salmonella isolates, 50 (60.2%) of the isolates showed higher statistically significant MAR (>0.2) than the other 33 (39.8%) Salmonella isolates with MAR ⩽ 0.2.

Figure 2.

Occurrence of MDR of Salmonella enterica isolated.

MDR: multi-drug resistant.

Figure 3.

Multiple antimicrobial resistance index of Salmonella serovars.

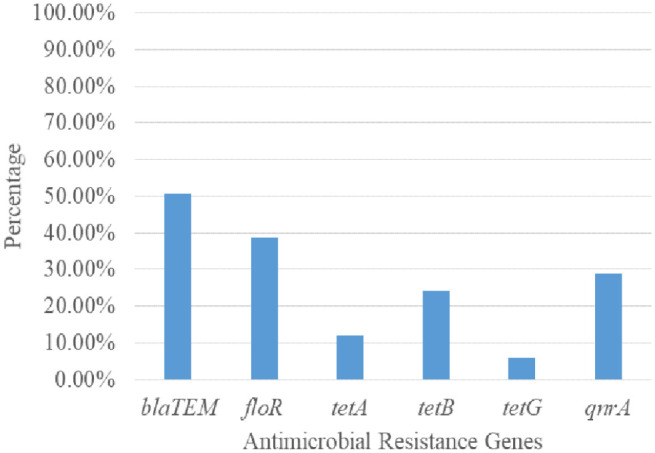

Of the resistance genes investigated, the blaTEM gene with 42 (50.5%) was the most common occurrence in the study. The occurrences of the other resistance genes were as follows, floR 32 (38.6%), tetA 10 (12.0%), tetB 20 (24.1%), tetG 5 (6.0%), and qnrA genes 24 (28.9%). The study showed no blaSHV and blaCTX-M, as shown in Figure 4. Table 3 shows the occurrence of the resistance genes in typhoidal and non-typhoidal S. enterica. There was no statistical significance (p > 0.05) differences in the occurrence of the resistance genes in typhoidal and non-typhoidal S. enterica.

Figure 4.

Prevalence of resistance genes from the Salmonella enterica isolates.

Table 3.

Occurrences of resistance genes in typhoidal and non-typhoidal Salmonella in the study.

| Classes | Genes | No positive isolates N = 83 (%) | Salmonella enterica | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typhoidal n = 51 | Non-typhoidal n = 32 | ||||

| Beta-lactams | bla TEM * | 42 (50.6) | 29 (56.9) | 13 (40.6) | 0.15 |

| bla SHV | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA | |

| blaCTX-M | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA | |

| Chloramphenicol | floR * | 32 (38.6) | 20 (39.2) | 12 (37.5) | 0.88 |

| Tetracycline | tetA ** | 10 (12.0) | 8 (15.7) | 2 (6.3) | 0.30 |

| tetB * | 20 (24.1) | 13 (25.5) | 7 (21.9) | 0.71 | |

| tetG ** | 5 (6.0) | 2 (3.9) | 3 (9.4) | 0.37 | |

| Fluoroquinolone | qnrA * | 24 (28.9) | 16 (31.4) | 8 (25.0) | 0.53 |

n: number; %: percentage; NA: not applicable. p < 0.05 = statistical significance; p > 0.05 = statistical insignificance.

Chi-square statistic.

Fisher’s exact test.

For even phenotypic resistance recorded, the corresponding gene was determined, κ agreement analysis was done, and the outcomes showed perfect agreement for chloramphenicol (κ = 0.954), tetracycline (κ = 1), and ciprofloxacin (κ = 1), but there was a moderate agreement between phenotypic detection of β-lactam and the genotypic detection with κ = 0.60 as shown in Supplemental Table 3.

PCR-based detection of virulence-determined genes

Of the seven virulence genes examined, SPIs encoding genes (invA, sopB, mgtC, and spi4D) were found in all the Salmonella isolates 83 (100.0%). Gene spvC occurred in 45 (51.8%) S. enterica recovered in the study. In comparison, gene ssaQ occurrence was found in 33 (39.8 %) of the Salmonella isolates, but the ljsGI-1 gene was found in 2 (2.4%) of the Salmonella isolates shown in Figure 5. The prevalence of spvC genes in typhoidal Salmonellae 30 (58.8%) was insignificantly higher than non-typhoidal Salmonellae 16 (57.1%). In contrast, gene ssaQ occurrence in typhoidal Salmonellae 17 (33.3%) is significantly (p = 0.02) lower than in non-typhoidal Salmonellae 16 (57.1%). The ljsGI-1 gene was found only in two (3.9%) typhoidal sub-group, as shown in Table 4.

Figure 5.

Prevalence of virulence genes from the Salmonella enterica isolates.

Table 4.

Occurrence of virulence genes in invasive typhoidal and non-typhoidal Salmonella.

| Genes | Total | Typhoidal | Non-typhoidal | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n = 83 n (%) |

n = 51 n (%) |

n = 32 n (%) |

||

| invA | 83 (100.0) | 51 (100.0) | 32 (100.0) | 1.0 |

| sopB | 83 (100.0) | 51 (100.0) | 32 (100.0) | 1.0 |

| mgtC | 83 (100.0) | 51 (100.0) | 32 (100.0) | 1.0 |

| Sip4D | 83 (100.0) | 51 (100.0) | 32 (100.0) | 1.0 |

| spvC | 45 (51.8) | 30 (58.8) | 15 (42.8) | 0.29 |

| ssaQ | 33 (39.8) | 17 (33.3) | 16 (57.1) | 0.02 |

| ljsGI-1 | 2 (2.4) | 2 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.52 |

n: number; %: percentage. p < 0.05 = statistical significance; p > 0.05 = statistical insignificance.

Chi-square statistic.

Fisher’s exact test..

Discussion

Increased resistant S. enterica has continued to pose a significant threat to human health and animal protection, and their spread is being increasingly found in clinical, food, and animal samples. Our study found typhoidal Salmonella serovars and non-typhoidal Salmonella serovars similar to the report by Awol et al. 64 in a multicenter study. Ke et al. 65 and Stanaway et al. 66 show that children in poor and middle-income countries with sub-optimal water, sanitation, and hygiene have a considerable and progressive increase in invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella (iNTS) infection. Invasive typhoid and non-typhoidal Salmonella have been previously reported in Nigerian children.5,8,27,67,68

Regarding the serovars found in this study, S. typhi was the highest, followed by S. choleraesuis, S. enteritidis, and S. typhimurium. Salmonella typhi is the most common serovar in invasive Salmonella infection in children, according to previous studies conducted in Nigeria and elsewhere.5,8,67,69–71 Serovars S. enteritidis and S. typhimurium are not frequently observed in invasive non-typhoidal infections in industrialized countries. Still, in sub-Saharan Africa, they are becoming a reoccurring decimal. Two African authors have previously reported them in invasive Salmonella infection.72,73

High levels of resistance to ampicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, and other routinely used antibiotics were found in our investigation. Salmonella strains isolated from invasive environments resist many of the most widely used antibiotics.5,67,70,71 In particular, multidrug-resistant iNTS caused life-threatening invasive disease outbreaks in children in Nigeria, Rwanda, and Malawi.67,74,75

The antimicrobial resistance of iNTS is a big problem because it can cause bacteremia in immunocompromised people. 76 The high prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant Salmonella is a serious concern for public health. 58 Salmonella typhi was the most common cause of invasive typhoidal Salmonella infection, and its high MDR and low ciprofloxacin susceptibility rates were the most striking findings of our investigation. This result is consistent with patterns seen in Cambodia by Vlieghe et al. 77 when describing MDR in S. typhi. The MDR has been observed in S. enterica in several countries in literature.78–80Salmonella typhi with multi-drug resistance was found in an assessment of typhoid fever cases in Pakistan, Vietnam, India, China, Indonesia, and Nigeria.73,81–85Our finding regarding MDR in Salmonella isolates in Nigeria agreed with previous reports and the assertion that Nigeria is in the vicinity region referred to as a hotspot for antimicrobial overuse.19,86

The MAR index, a cost-effective and valid method of bacteria origin tracking, was also calculated. It has become possible to tell bacteria apart by their resistance to the most popular antibiotics in human medicine by doing a MAR analysis.87–89 Compared to other methods of bacteria source tracking, such as genotypic characterization, the MAR indexing method is cost-effective, rapid, and easy to perform. 90 MAR index values greater than 0.2 indicate a high-risk source of contamination and index for high antibiotics usage. 88 This study reported a high MAR index >0.2 for S. enterica from invasive sources, which concerns the efficacy of treatment options available. High MAR in S. enterica has been attributed to plasmids containing one or more resistance genes,91–93 each encoding a single antibiotic resistance phenotype. 94 This study did not find XDR and PDR support in literature.91–93

Our results revealed significant positivity of blaTEM in the S. enterica studied. The blaTEM gene found in this study was slightly higher in invasive typhoidal strains than iNTS. The presence of the blaTEM gene in most of the S. enterica in our study supported earlier assertion, which suggested that blaTEM genes code for beta-lactam drug resistance like ampicillin. 95 Beta-lactamase produced by gram-negative bacteria remains the primary mechanism by which they develop resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics. Additionally, ESBLs are increasingly common among S. enterica serovars, and their frequency and prevalence have been reported to rise.96–98 Although blaCTX-M and blaSHV were not found in this study, recent studies from Asia and some parts of Africa have reported them,96,99 specifically reports of the blaSHV gene from clinical S. enterica from India.100–103 Therefore, monitoring the incidence of blaTEM in S. enterica isolates is a crucial public health tool in combatting this threat.

Salmonella enterica isolates with phenotypically intermediate ciprofloxacin susceptibility (ICS) were found to harbor plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR) genes (qnrA). This observation agrees with a report from India 104 with observations in human samples (51.4%), food-producing animals (28.6%), environmental samples (11.4%), and animal samples (8.6%), respectively.89,105–107 Ciprofloxacin has become prominent in treating severe infections caused by S. enterica, especially those resistant to nalidixic acid, which has increased significantly in recent years. Still, high resistance levels to ciprofloxacin are rare, but its resistance is foundational for other resistance mechanisms.75,108,109 Mutants resistant to fluoroquinolones are being rapidly selected due to the spread of PMQR genes. 110 Moreover, interactions between mutations in the QRDR and PMQR genes might result in high fluoroquinolones MIC. However, a study 111 speculated that the qnr genes could increase fluoroquinolone resistance.

In literature, tetA, tetB, and tetG were consistently found in S. enterica of human origin. The tetB gene is predominant among the phenotypic tetracycline-resistant strains in the literature. Our findings agreed with two studies that have reported tetA and tetB in S. enterica from a human with gastroenteritis in India and Nigeria.112,113tetG has also been reported in humans with bacteremia in Nigeria. 113 However, studies examining tetracycline resistance in multiple isolates reported tetA, tetB, and other types in S. enterica isolates from humans and those from animals, environments, and poultries.113,114 Regarding the family Enterobacteriaceae, the tetB and tetA tetracycline resistance determinants have historically been the most prevalent. 112 However, tet (C, D, E, M, O) associated with tetracycline resistance in Salmonella species and other bacteria are less frequently found.

Salmonella isolates that have developed phenotypic resistance to chloramphenicol are strongly linked to the development and expression of efflux that pumps the drug out of the bacteria’s cells,115,116 encoded by floR or cml genes. In our study, all invasive S. enterica phenotypically resistant to chloramphenicol had floR gene. These findings agree with reports of floR gene detection from S. enterica in the literature.117,118 Also, it has been asserted that the floR gene of Salmonella pathogenicity island-1 contributes to S. enterica infectivity. 92 Chloramphenicol was one of Nigeria’s most common drugs of choice in treating Salmonella-related infections. A survey revealed 72.4%–89.2% increased resistance from 1997 to 2007, thus limiting its therapeutic value.117,118 In Iraq, chloramphenicol-associated genes were highly occurring in S. enterica strains isolated from clinical samples.119,120 In literature, chloramphenicol was the first-line drug used to treat typhoid fever, but its recurrent use limits its therapeutic value due to resistance development.119,120

The presence of invA, sopB, spi4D, and mgtC genes in all the tested isolates agreed with the literature’s earlier evidence.13,121,122Salmonella invasion gene (invA) is involved in the invasion of the intestinal epithelium cells and is found in pathogenic S. enterica. 123 Therefore, for Salmonella infection to occur, invasion of the cells must occur, aided by invA gene.124–126 The invA gene influences the type of Salmonella infection that could result in either systemic or localized. 127 This gene is a transcriptional regulator required to express several genes encoding type III secretion system SPI-1 effector proteins.57,121,128 The invA gene was previously hypothesized to be widely distributed among the S. enterica isolates irrespective of their serovars or source of isolation. Thus, the invA gene is a suitable target for detecting S. enterica from different biological specimens, as documented in the literature.56,60,121,127,129–131

The inositide phosphate phosphatase (sopB) gene is an effector protein that induces macropinocytosis. Gene sopB is an actin-binding protein that interacts with the host cell actin cytoskeleton. It is required for efficient bacterial internalization by the host cell. 132 The sopB gene in all isolates is instructive because sopB has been reportedly involved in micropinocytosis. 133 Macrophages have been considered the main target of Salmonella during infection, and these cells are responsible for bacterial dissemination and control.134–136 In addition to macrophages, other immune system cells are targets of S. enterica pathogens, dendritic cells, and neutrophils.

Furthermore, B cells have also been targeted by S. enterica through the expression of sopB. 137 The sopB genes are necessary for intracellular survival in the host, so the presence of sopB gene is suggested to contribute to the invasiveness of S. enterica pathogens,138,139 found in all the isolates in this study. The sopB gene is also involved in host cell survival by activating the Akt signaling pathway, including activation of the host innate immune system and cell death. 133 The presence of bacterial effector sopB in our study supported the earlier assumption that activation of Akt pathway is mediated through the expression of sopB.

In literature, 126 Salmonella’s SPI-3 island is associated with intra-macrophage invasion, which supports survival when Mg2+, required in the bacteria transported system, is of limited amount. The presence of mgtC gene in all the Salmonella in this study supported the proposition that S. enterica uses the expression of mgtC gene to circumvent the lack of Mg2+ in the bacteria. They, therefore, initiate Mg2+ production without depending on the host for Mg2+. Our findings are supported in earlier literature.13,137,139,140Salmonella enterica contains several transport systems, both inducible and constitutive. 140 These transport systems have functional complementarities to adjust the Mg2+ concentration in different environmental conditions. In addition, these systems are controlled by transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulatory networks to maintain strict control of the Mg2+ balance. 126 Regarding maintaining Salmonella viability and development in environments with low Mg2+ levels, mgtC appears to be the most crucial SPI-3 component, as reported in some S. enterica isolates 140 and S. typhi. 13 Since mgtC is encoded in a region of SPI-3 that is highly conserved, it plays a crucial role in virulence that is not met by any other factor encoded in SPI-3 or anywhere else on the S. enterica chromosome.121,141

The ssaQ gene was detected in 33 (39.8 %) Salmonella isolates examined. The importance of this gene is relevant in the surveillance of S. enterica, which has been involved in systemic infection in the past. It has been found to produce proteins for the bacteria that bind to and stabilize the larger protein, which is important for the overall efficiency of the secretory system. 142 Essential for virulence in host cells, survival in macrophages, and biofilm development is the ssaQ gene, which codes for proteins in the SPI-2 type III secretion system. 143

The Salmonella plasmid virulence (spvC) gene was significantly higher in iNTS than in typhoid Salmonella isolates. By eliminating their beta-subunits, the spvC gene renders inactive the host’s dual-phosphorylated mitogen-activated protein kinases. It is also hypothesized to play a role in systemic S. enterica infection due to its anti-inflammatory effector effects and attenuation of the intestinal inflammatory response. 144 The spvB gene may collaborate with spvC and other Salmonella effectors to play a role in pathogenesis by triggering apoptosis in human macrophages. The spv genes increase the virulence of non-typhoid Salmonella serovars to induce extra-intestinal illness, as shown by experimental models and human epidemiological data. 145 Intestinal infections caused by non-typhoid Salmonella, typically present as self-limiting gastroenteritis, can be terminated by spv genes. 129 In mice, a study 145 discovered that the spv locus in Salmonella serovars is a crucial distinction in the pathogenesis of typhoid fever compared to that of non-typhoid Salmonella bacteremia.

Study limitations

As this is a further study on Salmonella isolates from an initial isolation process, the sample size was not determined; as such, all the Salmonella isolates recovered from 2015 to 2018 were included in this study. Gene sequencing of the antibiotic resistance and the virulence genes of Salmonella isolates detected were not done to detect mutations that could adversely affect the activity of the antimicrobial agents and their pathogenicity abilities.

Conclusions

The result of our study illustrates the emergence of multi-drug resistant S. enterica from children with bacteremia in north-central Nigeria. The most common antibiotics that S. enterica recovered were resistant to were ampicillin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Some recovered S. enterica demonstrated multi-drug resistance to penicillins, first-generation cephalosporin (cephalothin), phenicol, sulfonamide, tetracycline, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolone. None of the S. enterica isolates met the criteria required for XDR and PDR designation. The recovered antimicrobial resistance genes (blaTEM, qnrA, floR, tetA, tetB, and tetG) were found. The most prevalent gene was blaTEM, while tetG was the least prevalent resistance gene. The invA, sopB, mgtC, and sip4D were found in all the recovered S. enterica isolates. At the same time, most S. enterica also harbored spvC and ssaQ genes, respectively, with ljsGI-1 gene found in only two S. typhi isolates. Therefore, this study recommends continuous monitoring of antimicrobial resistance patterns of S. enterica from invasive sources in Nigeria and encourages the prudent use of antibiotics and the practices of other infection prevention control measures.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-smo-10.1177_20503121231175322 for Antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes of invasive Salmonella enterica from children with bacteremia in north-central Nigeria by Leonard I Uzairue, Olufunke B Shittu, Olufemi E Ojo, Tolulope M Obuotor, Grace Olanipekun, Theresa Ajose, Ronke Arogbonlo, Nubwa Medugu, Bernard Ebruke and Stephen K Obaro in SAGE Open Medicine

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Laboratory staff of the International Foundation Against Infectious Disease in Nigeria for their assistance during the project implementation.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Leonard Uzairue was involved in conceptualization, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, visualization, and writing; Olufunke Shittu was involved in conceptualization, editing, and supervision; Olufemi Ojo and Tolulope M. Obuotor were involved in editing and supervision; Grace Olanipekun, Theresa Ajose, and Ronke Arogbonlo were involved in project administration and supervision. Nubwa Medugu and Bernard Ebruke were involved in methodology, supervision, and editing; and Stephen Obaro was involved in conceptualization, supervision, and editing.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval and consent to participate: The research got approvals from the Research Ethics Committees of the Federal Medical Centre Keffi (FMC/KF/HREC/052/15), the Nyanya General Hospital, FCT, Abuja (FCTA/HHSS/HMB/NH/GEN/54/II/128), and the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital (FCT/UATH/HREC/PR/61). Written informed consent was obtained from the parent or guardian of the children. The identities of all data/samples used for this study were removed entirely.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the parent or guardian of the children.

ORCID iD: Leonard I Uzairue  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2547-175X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2547-175X

Availability of data and materials: All data from this research are available at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/3njxchzht8/1.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Jajere SM. A review of Salmonella enterica with particular focus on the pathogenicity and virulence factors, host specificity and antimicrobial resistance including multidrug resistance. Vet World 2019; 12: 504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. Serotypes and the Importance of Serotyping Salmonella | Salmonella Atlas | Reports and Publications | Salmonella | CDC. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Epub ahead of print 2015. DOI: 10.1208/s12249-010-9573-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koolman L, Prakash R, Diness Y, et al. Case-control investigation of invasive Salmonella disease in Malawi reveals no evidence of environmental or animal transmission of invasive strains, and supports human to human transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2022; 16: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Igomu EE. Salmonella Kentucky in Nigeria and the Africa continent. African J Clin Exp Microbiol 2020; 21: 272–283. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obaro SK, Hassan-Hanga F, Olateju EK, et al. Salmonella bacteremia among children in central and Northwest Nigeria, 2008-2015. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61: S325–S331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim SH, Methé BA, Knoll BM, et al. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella in sickle cell disease in Africa: Is increased gut permeability the missing link? J Transl Med; 16. Epub ahead of print 2018. DOI: 10.1186/s12967-018-1622-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song W, Shan Q, Qiu Y, et al. Clinical profiles and antimicrobial resistance patterns of invasive Salmonella infections in children in China. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2022; 41: 1215–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olanira O, Japhet O, Asinwa HJ, et al. Isolation and evaluation of Salmonella and Shigella spps in children in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Int Clin Pathol J 2016; 2: 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC. Serotypes and the Importance of Serotyping Salmonella | Salmonella Atlas | Reports and Publications | Salmonella | CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/reportspubs/salmonella-atlas/serotyping-importance.html (2018, accessed 18 March 2022).

- 10.Mthembu TP, Zishiri OT, El Zowalaty ME. Genomic characterization of antimicrobial resistance in food chain and livestock-associated salmonella species. Animals 2021; 11: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mastrorilli E, Petrin S, Orsini M, et al. Comparative genomic analysis reveals high intra-serovar plasticity within Salmonella Napoli isolated in 2005-2017. BMC Genomics 2020; 21: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puget S, Philippe C, De Carli E, et al. Use of integrated genomics to identify three high-grade glioma subtypes with distinct genetic profiles, pathway signatures, and clinicopathologic features. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: e12500–.e12510 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elemfareji OI, Thong KL. Comparative virulotyping of Salmonella typhi and Salmonella enteritidis. Indian J Microbiol 2013; 53: 410–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khoo CH, Cheah YK, Lee LH, et al. Virulotyping of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica isolated from indigenous vegetables and poultry meat in Malaysia using multiplex-PCR. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, Int J Gen Mol Microbiol 2009; 96: 441–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilchrist JJ, MaClennan CA, Hill AVS. Genetic susceptibility to invasive Salmonella disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2015; 15: 452–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feasey NA, Dougan G, Kingsley RA, et al. Invasive non-typhoidal salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa. Lancet 2012; 379: 2489–2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dongol S, Thompson CN, Clare S, et al. The microbiological and clinical characteristics of invasive Salmonella in gallbladders from cholecystectomy patients in Kathmandu, Nepal. PLoS One; 7. Epub ahead of print 2012. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feasey NA, Dougan G, Kingsley RA, et al. Invasive non-typhoidal salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa. Lancet 2012; 379: 2489–2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okoro CK, Kingsley RA, Connor TR, et al. Intracontinental spread of human invasive Salmonella typhimurium pathovariants in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat Genet 2012; 44: 1215–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood MW, Jones MA, Watson PR, et al. Identification of a pathogenicity island required for Salmonella enteropathogenicity. Mol Microbiol 1998; 29: 883–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antonio Ibarra J, Knodler LA, Sturdevant DE, et al. Induction of Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 under different growth conditions can affect Salmonella-host cell interactions in vitro. Microbiology 2010; 156: 1120–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lokken KL, Walker GT, Tsolis RM. Disseminated infections with antibiotic-resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella strains: contributions of host and pathogen factors. Pathog Dis 2021; 74: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obaro S, Lawson L, Essen U, et al. Community acquired bacteremia in young children from central Nigeria–a pilot study. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11: 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cabral JPS. Water microbiology. Bacterial pathogens and water. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2010; 7: 3657–3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bintsis T. Foodborne pathogens. AIMS Microbiol 2017; 3: 529–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith SI, Seriki A, Ajayi A. Typhoidal and non-typhoidal Salmonella infections in Africa. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2016; 35: 1913–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ifeanyi Smith S. Molecular detection of some virulence genes in Salmonella spp isolated from food samples in Lagos, Nigeria. Anim Vet Sci. Epub ahead of print 2015. DOI: 10.11648/j.avs.20150301.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos RL, Mikoleit ML, Unit S, et al. Characterization of Salmonella isolates from retail foods based on serotyping, pulse field gel electrophoresis, antibiotic resistance and other phenotypic properties. Appl Environ Microbiol 2014; 77: 187–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith I, Anejo-Okopi J, Audu O, et al. Isolation and polymerase chain reaction detection of virulence invA gene in Salmonella spp. from poultry farms in Jos, Nigeria. J Med Trop 2017; 18: 98. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dieye Y, Hull DM, Wane AA, et al. Genomics of human and chicken Salmonella isolates in Senegal: Broilers as a source of antimicrobial resistance and potentially invasive nontyphoidal salmonellosis infections. PLoS One 2022; 17: 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Algammal AM, Hetta HF, Batiha GE, et al. Virulence-determinants and antibiotic-resistance genes of MDR-E. coli isolated from secondary infections following FMD-outbreak in cattle. Sci Rep; 10. Epub ahead of print 1 December 2020. DOI: 10.1038/S41598-020-75914-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Algammal AM, Hashem HR, Alfifi KJ, et al. AtpD gene sequencing, multidrug resistance traits, virulence-determinants, and antimicrobial resistance genes of emerging XDR and MDR-Proteus mirabilis. Sci Rep; 11. Epub ahead of print 1 December 2021. DOI: 10.1038/S41598-021-88861-W. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makharita RR, El-Kholy I, Hetta HF, et al. Antibiogram and genetic characterization of carbapenem-resistant gram-negative pathogens incriminated in healthcare-associated infections. Infect Drug Resist 2020; 13: 3991–4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Algammal AM, Hetta HF, Elkelish A, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): one health perspective approach to the bacterium epidemiology, virulence factors, antibiotic-resistance, and zoonotic impact. Infect Drug Resist 2020; 13: 3255–3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Algammal AM, Mabrok M, Sivaramasamy E, et al. Emerging MDR-Pseudomonas aeruginosa in fish commonly harbor oprL and toxA virulence genes and bla TEM, bla CTX-M, and tetA antibiotic-resistance genes. Sci Rep; 10. Epub ahead of print 1 December 2020. DOI: 10.1038/S41598-020-72264-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma F, Xu S, Tang Z, et al. Use of antimicrobials in food animals and impact of transmission of antimicrobial resistance on humans. Biosaf Heal 2021; 3: 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marshall BM, Levy SB. Food animals and antimicrobials: impacts on human health. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011; 24: 718–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kimera ZI, Mshana SE, Rweyemamu MM, et al. Antimicrobial use and resistance in food-producing animals and the environment: an African perspective. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2020; 9: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.WHO. Antibiotic resistance, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antibiotic-resistance (2020, accessed 7 May 2021).

- 40.Simpson KMJ, Mor SM, Ward MP, et al. Genomic characterisation of Salmonella enterica serovar Wangata isolates obtained from different sources reveals low genomic diversity. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0229697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oghenevo OJ, Bassey BE, Yhiler NY, et al. Antibiotic resistance in extended spectrum beta-lactamases (Esbls) Salmonella species isolated from patients with diarrhoea in Calabar, Nigeria. J Clin Infect Dis Pract; 1. Epub ahead of print 2016. DOI: 10.4172/2476-213x.1000107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramachandran A, Shanthi M, Sekar U. Detection of blaCTX-M extended spectrum betalactamase producing salmonella enterica serotype typhi in a tertiary care centre. J Clin Diagnostic Res 2017; 11: DC21–DC24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Djeffal S, Bakour S, Mamache B, et al. Prevalence and clonal relationship of ESBL-producing Salmonella strains from humans and poultry in northeastern Algeria. BMC Vet Res 2017; 13: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akinyemi KO, Iwalokun BA, Alafe OO, et al. BlaCTX-M-I group extended spectrum beta lactamase-producing Salmonella typhi from hospitalized patients in Lagos, Nigeria. Infect Drug Resist 2015; 8: 99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saka HK, García-Soto S, Dabo NT, et al. Molecular detection of extended spectrum β-lactamase genes in Escherichia coli clinical isolates from diarrhoeic children in Kano, Nigeria. PLoS One 2020; 15: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ranjbar R, Ardashiri M, Samadi S, et al. Distribution of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) among salmonella serogroups isolated from pediatric patients. Iran J Microbiol 2018; 10: 294–299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang YJ, Chen MC, Feng Y, et al. Highly antimicrobial-resistant nontyphoidal Salmonella from retail meats and clinical impact in children, Taiwan. Pediatr Neonatol 2020; 61: 432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tack B, Vanaenrode J, Verbakel JY, et al. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella infections in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review on antimicrobial resistance and treatment. BMC Med 2020; 18: 1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alcaine SD, Warnick LD, Wiedmann M. Antimicrobial resistance in nontyphoidal Salmonella. J Food Prot 2007; 70: 780–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Achiangia Njukeng P, Ebot Ako-Arrey D, Tajoache Amin E, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in the central African region: a review. J Environ Sci Public Heal 2019; 3: 358–378. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ngogo FA, Joachim A, Abade AM, et al. Factors associated with Salmonella infection in patients with gastrointestinal complaints seeking health care at Regional Hospital in Southern Highland of Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bailey A, Scott B. Diagnostic microbiology: eleventh edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press (OUP). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Popoff MY, Bockemühl J, Brenner FW, et al. Supplement 2000 (no. 44) to the Kauffmann-White scheme. Res Microbiol 2001; 152: 907–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 26th ed, CLSI supplement M100S. Wayne, PA: CLSI, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davis R, Brown PD. Multiple antibiotic resistance index, fitness and virulence potential in respiratory Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Jamaica. J Med Microbiol 2016; 65: 261–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ibrahim WA, Abd El-Ghany WA, Nasef SA, et al. A comparative study on the use of real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and standard isolation techniques for the detection of Salmonellae in broiler chicks. Int J Vet Sci Med 2014; 2: 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weill F-X, Brisabois A, Fach P, et al. A multiplex real-time PCR assay targeting virulence and resistance genes in Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium. BMC Microbiol 2011; 11: 151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roschanski N, Fischer J, Guerra B, et al. Development of a multiplex real-time PCR for the rapid detection of the predominant beta-lactamase genes CTX-M, SHV, TEM and CIT-type AmpCs in Enterobacteriaceae. PLoS One 2014; 9: e100956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vien LTM, Minh NNQ, Thuong TC, et al. The co-selection of fluoroquinolone resistance genes in the gut flora of Vietnamese children. PLoS One; 7. Epub ahead of print 2012. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Singh P, Mustapha A. Multiplex TaqMan® detection of pathogenic and multi-drug resistant Salmonella. Int J Food Microbiol 2013; 166: 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guarddon M, Miranda JM, Rodríguez JA, et al. Real-time polymerase chain reaction for the quantitative detection of tetA and tetB bacterial tetracycline resistance genes in food. Int J Food Microbiol 2011; 146: 284–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wong VK, Holt KE, Okoro C, et al. Molecular surveillance identifies multiple transmissions of typhoid in West Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016; 10: 1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jeamsripong S, Li X, Aly SS, et al. Antibiotic resistance genes and associated phenotypes in Escherichia coli and Enterococcus from cattle at different production stages on a dairy farm in Central California. Antibiotics 2021; 10(9): 1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Awol RN, Reda DY, Gidebo DD. Prevalence of Salmonella enterica serovar typhi infection, its associated factors and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns among febrile patients at Adare general hospital, Hawassa, southern Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis 2021; 21: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ke Y, Lu W, Liu W, et al. Non-typhoidal salmonella infections among children in a tertiary hospital in ningbo, zhejiang, china, 2012–2019. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020; 14: 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stanaway JD, Parisi A, Sarkar K, et al. The global burden of non-typhoidal salmonella invasive disease: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19: 1312–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Akinyemi KO, Fakorede CO. Antimicrobial resistance and resistance genes in salmonella enterica serovars from Nigeria. New Delhi: Blaha, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ikhimiukor OO, Oaikhena AO, Afolayan AO, et al. Genomic characterization of invasive typhoidal and non-typhoidal Salmonella in southwestern Nigeria. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2022; 16: 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Akinyemi KO, Oyefolu AOB, Mutiu WB, et al. Typhoid fever: tracking the trend in Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. Epub ahead of print 2018. DOI: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ifeanyi Smith S. Molecular detection of some virulence genes in Salmonella spp isolated from food samples in Lagos, Nigeria. Anim Vet Sci 2015; 3: 22. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ogundipe OO, Ogundipe FO, Bamidele FA, et al. Incidence of bacteria with potential public health implications in raw Lycopersicon esculentum (tomato) sold in Lagos State, Nigeria. Niger Food J. Epub ahead of print 2015. DOI: 10.1016/s0189-7241(15)30043-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gordon MA. Invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2011; 24: 484–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Crump JA, Heyderman RS. A perspective on invasive salmonella disease in Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61: S235–S240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brisabois A, Cazin I, Breuil J, et al. Surveillance of antibiotic resistance in Salmonella. Eurosurveillance. Epub ahead of print 2017. DOI: 10.2807/esm.02.03.00181-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kariuki S, Gordon MA, Feasey N, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and management of invasive Salmonella disease. Vaccine 2015; 33: C21–C29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.de Jong HK, Parry CM, van der Poll T, et al. Host-pathogen interaction in invasive Salmonellosis. PLoS Pathog. Epub ahead of print 2012. DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vlieghe ER, Phe T, De Smet B, et al. Azithromycin and ciprofloxacin resistance in Salmonella bloodstream infections in Cambodian adults. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2012; 6: e1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Butler T. Treatment of typhoid fever in the 21st century: promises and shortcomings. Clin Microbiol Infect. Epub ahead of print 2011. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cajetan Ifeanyi CI, Bassey BE, Ikeneche NF, et al. Molecular characterization and antibiotic resistance of Salmonellain children with acute gastroenteritis in Abuja, Nigeria. J Infect Dev Ctries. Epub ahead of print 2014. DOI: 10.3855/jidc.4185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.The European union summary report on antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2017. EFSA J. Epub ahead of print 2019. DOI: 10.2903/j.efsa.2019.5598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Raufu I, Bortolaia V, Svendsen CA, et al. The first attempt of an active integrated laboratory-based Salmonella surveillance programme in the north-eastern region of Nigeria. J Appl Microbiol 2013; 115: 1059–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kiran Y, Yadav SK, Geeta P. A comparative study of typhidot and widal test for rapid diagnosis of typhoid fever. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci 2015; 4: 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mehmood K, Sundus A, Naqvi IH, et al. Typhidot – a blessing or a menace. Pakistan J Med Sci 2015; 31: 439–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu J, Liu L, Jin Y, et al. Epidemiological characteristics and molecular typing of Samonella spp. in Longgang district of Shenzhen during 2010-2013. J Trop Med 2015; 15(9): 1262–1265. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Karkey A, Jombart T, Walker AW, et al. The ecological dynamics of fecal contamination and Salmonella typhi and Salmonella paratyphi A in municipal Kathmandu drinking water. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016; 10: e0004346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nwabor OF, Dickson ID, Ajibo QC. Epidemiology of Salmonella and Salmonellosis. Int Lett Nat Sci. Epub ahead of print 2015. DOI: 10.18052/www.scipress.com/ILNS.47.54. [DOI]

- 87.Ajayi AO, Egbebi AO. Antibiotic sucseptibility of Salmonella typhi and Klebsiella pneumoniae from poultry and local birds in Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti-State, Nigeria. Ann Biol Res 2011; 2: 431–437. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Oluyege JO, Dada AC, Odeyemi AT. Incidence of multiple antibiotic resistant Gram-negative bacteria isolated from surface and underground water sources in south western region of Nigeria. Water Sci Technol. Epub ahead of print 2009. DOI: 10.2166/wst.2009.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Su HC, Ying GG, He LY, et al. Antibiotic resistance, plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR) genes and ampC gene in two typical municipal wastewater treatment plants. Environ Sci Process Impacts. Epub ahead of print 2014. DOI: 10.1039/c3em00555k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Paul S, Bezbaruah RL, Roy MK, et al. Multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) index and its reversion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Lett Appl Microbiol. Epub ahead of print 1997. DOI: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.1997.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mather AE, Denwood MJ, Haydon DT, et al. The prevalences of salmonella genomic island 1 variants in human and animal Salmonella typhimurium DT104 are distinguishable using a Bayesian approach. PLoS One; 6. Epub ahead of print 2011. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hall RM. Salmonella genomic islands and antibiotic resistance in Salmonella enterica. Future Microbiology. Epub ahead of print 2010. DOI: 10.2217/fmb.10.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vo ATT, van Duijkeren E, Fluit AC, et al. A novel Salmonella genomic island 1 and rare integron types in Salmonella typhimurium isolates from horses in the Netherlands. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007; 59: 594–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sung JY, Kim S, Kwon GC, et al. Molecular characterization of Salmonella genomic island 1 in Proteus mirabilis isolates from Chungcheong Province, Korea. J Microbiol Biotechnol. Epub ahead of print 2017. DOI: 10.4014/jmb.1708.08040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tran-Dien A, Le Hello S, Bouchier C, et al. Early transmissible ampicillin resistance in zoonotic Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium in the late 1950s: a retrospective, whole-genome sequencing study. Lancet Infect Dis. Epub ahead of print 2018. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30705-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Maharjan A, Bhetwal A, Shakya S, et al. Ugly bugs in healthy guts! carriage of multidrug-resistant and ESBL-producing commensal enterobacteriaceae in the intestine of healthy nepalese adults. Infect Drug Resist. Epub ahead of print 2018. DOI: 10.2147/IDR.S156593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rawat D, Nair D. Extended-spectrum ß-lactamases in gram negative bacteria. J Glob Infect Dis. Epub ahead of print 2010. DOI: 10.4103/0974-777x.68531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Morales JL, Reyes K, Monteghirfo M, et al. Presencia de β-lactamasas de espectro extendido en dos hospitales de Lima, Perú. An la Fac Med. Epub ahead of print 2017. DOI: 10.15381/anales.v66i1.1342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ojdana D, Sacha P, Wieczorek P, et al. The occurrence of bla CTX-M, bla SHV, and bla TEM genes in extended-spectrum β-lactamase-positive strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Proteus mirabilis in Poland . Int J Antibiot. Epub ahead of print 2014. DOI: 10.1155/2014/935842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jamali S, Shahid M, Sobia F, et al. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of cefotaximases, temoniera, and sulfhydryl variable β-lactamases in Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter isolates in an Indian tertiary health-care center. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. Epub ahead of print 2017. DOI: 10.4103/0377-4929.208377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Haque SF, Ali SZ, TP M, et al. Prevalence of plasmid mediated bla TEM-1 and bla CTX-M-15 type extended spectrum beta-lactamases in patients with sepsis. Asian Pac J Trop Med. Epub ahead of print 2012. DOI: 10.1016/S1995-7645(12)60003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pignato S, Coniglio MA, Faro G, et al. Molecular epidemiology of ampicillin resistance in Salmonella spp. and Escherichia coli from wastewater and clinical specimens. Foodborne Pathog Dis. Epub ahead of print 2010. DOI: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shahid M, Singh A, Sobia F, et al. BlaCTX-M, blaTEM, and blaSHVin enterobacteriaceae from North-Indian tertiary hospital: high occurrence of combination genes. Asian Pac J Trop Med. Epub ahead of print 2011. DOI: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wu H, Wang M, Liu Y, et al. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella species isolated from chicken broilers. Int J Food Microbiol. Epub ahead of print 2016. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Campbell D, Tagg K, Bicknese A, et al. Identification and characterization of salmonella enterica serotype newport isolates with decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. Epub ahead of print 2018. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.00653-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pribul BR, Festivo ML, de Souza MMS, et al. Characterization of quinolone resistance in Salmonella spp. isolates from food products and human samples in Brazil. Brazilian J Microbiol 2016; 47: 196–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Marti E, Balcázar JL. Real-time PCR assays for quantification of qnr genes in environmental water samples and chicken feces. Appl Environ Microbiol 2013; 79: 1743–1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. Epub ahead of print 2018. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Feasey NA, Masesa C, Jassi C, et al. Three epidemics of invasive multidrug-resistant salmonella bloodstream infection in Blantyre, Malawi, 1998-2014. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61: S363–S371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kariuki S, Onsare RS. Epidemiology and genomics of invasive nontyphoidal salmonella infections in Kenya. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61: S317–S324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Veeraraghavan B, Sharma A, Ranjan P, et al. Revised ciprofloxacin breakpoints for Salmonella typhi: its implications in India. Indian J Med Microbiol. Epub ahead of print 2014. DOI: 10.4103/0255-0857.129804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Waghamare RN, Paturkar AM, Vaidya VM, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic drug resistance profile of Salmonella serovars isolated from poultry farm and processing units located in and around Mumbai city, India. Vet World 2018; 11: 1682–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Adesiji YO, Deekshit VK, Karunasagar I. Antimicrobial-resistant genes associated with Salmonella spp. isolated from human, poultry, and seafood sources. Food Sci Nutr. Epub ahead of print 2014. DOI: 10.1002/fsn3.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Asgharpour F, Marashi SMA, Moulana Z. Molecular detection of class 1, 2 and 3 integrons and some antimicrobial resistance genes in salmonella infantis isolates. Iran J Microbiol 2018; 10: 104–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.White DG, Hudson C, Maurer JJ, et al. Characterization of chloramphenicol and florfenicol resistance in Escherichia coli associated with bovine diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol 2000; 38(12): 4593–4598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Briggs CE, Fratamico PM. Molecular characterization of an antibiotic resistance gene cluster of Salmonella typhimurium DT104. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1999; 43(4): 846-849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Akinyemi KO, Smith SI, Oyefolu AO, et al. Trends of multiple drug resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar typhi in Lagos, Nigeria. East Cent African J Surg 2014; 2(4): 436–442. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Akinyemi KO, Smith SI, Bola Oyefolu AO, et al. Multidrug resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar typhi isolated from patients with typhoid fever complications in Lagos, Nigeria. Public Health. Epub ahead of print 2005. DOI: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Roberts MC, Schwarz S. Tetracycline and chloramphenicol resistance mechanisms. In: Meyers D, Sobel J, Ouellette M, et al. (eds) Antimicrobial drug resistance. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer, 2017, pp. 231–242. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Huang XZ, Frye JG, Chahine MA, et al. Characteristics of plasmids in multi-drug-resistant enterobacteriaceae isolated during prospective surveillance of a newly opened hospital in Iraq. PLoS One. Epub ahead of print 2012. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bugarel M, Granier SA, Weill FX, et al. A multiplex real-time PCR assay targeting virulence and resistance genes in Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium. BMC Microbiol 2011; 11: 151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Byrne A, Johnson R, Ravenhall M, et al. Comparison of Salmonella enterica serovars typhi and typhimurium reveals typhoidal serovar-specific responses to bile. Infect Immun 2017; 86: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Chaudhary JH, Nayak JB, Brahmbhatt MN, et al. Virulence genes detection of Salmonella serovars isolated from pork and slaughterhouse environment in Ahmedabad, Gujarat. Vet World. Epub ahead of print 2015. DOI: 10.14202/vetworld.2015.121-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Pal S, Dey S, Batabyal K, et al. Characterization of Salmonella Gallinarum isolates from backyard poultry by polymerase chain reaction detection of invasion (invA) and Salmonella plasmid virulence (spvC) genes. Vet World. Epub ahead of print 2017. DOI: 10.14202/vetworld.2017.814-817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Brunelle BW, Bearson BL, Bearson SMD. Chloramphenicol and tetracycline decrease motility and increase invasion and attachment gene expression in specific isolates of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. Front Microbiol 2014; 5: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Suez J, Porwollik S, Dagan A, et al. Virulence gene profiling and pathogenicity characterization of non-typhoidal Salmonella accounted for invasive disease in humans. PLoS One; 8. Epub ahead of print 2013. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kasturi KN, Drgon T. Real-time PCR method for detection of Salmonella spp. in environmental samples. Appl Environ Microbiol 2017; 83: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Huehn S, La Ragione RM, Anjum M, et al. Virulotyping and antimicrobial resistance typing of Salmonella enterica serovars relevant to human health in Europe. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2010; 7: 523–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ben Hassena A, Barkallah M, Fendri I, et al. Real time PCR gene profiling and detection of Salmonella using a novel target: the siiA gene. J Microbiol Methods. Epub ahead of print 2015. DOI: 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Tennant SM, Diallo S, Levy H, et al. Identification by PCR of non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica serovars associated with invasive infections among febrile patients in Mali. PLoS Negl Trop Dis; 4. Epub ahead of print 2010. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Nga TVT, Karkey A, Dongol S, et al. The sensitivity of real-time PCR amplification targeting invasive Salmonella serovars in biological specimens. BMC Infect Dis; 10. Epub ahead of print 2010. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ammar AM, Mohamed AA, El-Hamid MIA, et al. Virulence genotypes of clinical salmonellaserovars from broilers in Egypt. J Infect Dev Ctries. Epub ahead of print 2016. DOI: 10.3855/jidc.7437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kerr MC, Wang JTH, Castro NA, et al. Inhibition of the PtdIns(5) kinase PIKfyve disrupts intracellular replication of Salmonella. EMBO J. Epub ahead of print 2010. DOI: 10.1038/emboj.2010.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Gondwe EN, Molyneux ME, Goodall M, et al. Importance of antibody and complement for oxidative burst and killing of invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella by blood cells in Africans. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2010; 107: 3070–3075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Mulder DT, Cooper CA, Coombes BK. Type VI secretion system-associated gene clusters contribute to pathogenesis of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium. Infect Immun. Epub ahead of print 2012. DOI: 10.1128/iai.06205-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Figueira R, Holden DW. Functions of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI-2) type III secretion system effectors. Microbiology. Epub ahead of print 2012. DOI: 10.1099/mic.0.058115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Nógrády N, Imre A, Kostyák Á, et al. Molecular and pathogenic characterization of Salmonella enterica serovar bovismorbificans strains of animal, environmental, food, and human origin in Hungary. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2010; 7: 507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Choudhury M, Borah P, Sarma HK, et al. Multiplex-PCR assay for detection of some major virulence genes of Salmonella enterica serovars from diverse sources. Curr Sci 2016; 111: 1252–1258. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Huehn S, La Ragione RM, Anjum M, et al. Virulotyping and antimicrobial resistance typing of Salmonella enterica serovars relevant to human health in Europe. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2010; 7: 523–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Retamal P, Castillo-Ruiz M, Mora GC. Characterization of MgtC, a virulence factor of Salmonella enterica serovar typhi. PLoS One. Epub ahead of print 2009. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Huehn S, La Ragione RM, Anjum M, et al. Virulotyping and antimicrobial resistance typing of Salmonella enterica serovars relevant to human health in Europe. Foodborne Pathog Dis. Epub ahead of print 2010. DOI: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Bhowmick PP, Devegowda D, Ruwandeepika HAD, et al. Presence of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 genes in seafood-associated Salmonella serovars and the role of the sseC gene in survival of Salmonella enterica serovar Weltevreden in epithelial cells. Microbiology. Epub ahead of print 2011. DOI: 10.1099/mic.0.043596-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Yoshida Y, Miki T, Ono S, et al. Functional characterization of the type III secretion ATPase SsaN encoded by Salmonella pathogenicity island 2. PLoS One. Epub ahead of print 2014. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Haneda T, Ishii Y, Shimizu H, et al. Salmonella type III effector SpvC, a phosphothreonine lyase, contributes to reduction in inflammatory response during intestinal phase of infection. Cell Microbiol. Epub ahead of print 2012. DOI: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Guiney DG, Fierer J. The role of the spv genes in Salmonella pathogenesis. Front Microbiol. Epub ahead of print 2011. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-smo-10.1177_20503121231175322 for Antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes of invasive Salmonella enterica from children with bacteremia in north-central Nigeria by Leonard I Uzairue, Olufunke B Shittu, Olufemi E Ojo, Tolulope M Obuotor, Grace Olanipekun, Theresa Ajose, Ronke Arogbonlo, Nubwa Medugu, Bernard Ebruke and Stephen K Obaro in SAGE Open Medicine