Abstract

Escherichia coli hosts expressing fabG of Pseudomonas aeruginosa showed 3-ketoacyl coenzyme A (CoA) reductase activity toward R-3-hydroxyoctanoyl-CoA. Furthermore, E. coli recombinants carrying the poly-3-hydroxyalkanoate (PHA) polymerase-encoding gene phaC in addition to fabG accumulated medium-chain-length PHAs (mcl-PHAs) from alkanoates. When E. coli fadB or fadA mutants, which are deficient in steps downstream or upstream of the 3-ketoacyl-CoA formation step during β-oxidation, respectively, were transformed with fabG, higher levels of PHA were synthesized in E. coli fadA, whereas similar levels of PHA were found in E. coli fadB, compared with those of the corresponding mutants carrying phaC alone. These results strongly suggest that FabG of P. aeruginosa is able to reduce mcl-3-ketoacyl-CoAs generated by the β-oxidation to 3-hydroxyacyl-CoAs to provide precursors for the PHA polymerase.

Bacteria have developed several approaches to store carbon and energy in the form of polysaccharides, polyamino acids, and polyesters (17). One well-known polyester is poly-3-hydroxyalkanoate (PHA), a bioplastic material. It is known that PHAs are synthesized by polymerization of coenzyme A (CoA)-linked R-3-hydroxy fatty acids through a PHA polymerase (PhaC) (for a recent review, see reference 10). The synthesis of such CoA substrates can occur by a variety of pathways (see review in reference 10), the simplest of which uses a β-ketothiolase (PhbA) and an NADPH-dependent acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PhbB) to synthesize precursors for short-chain-length PHAs such as poly-3-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) in Ralstonia eutropha. Precursors for so-called medium-chain-length PHAs (mcl-PHAs) can be generated through fatty acid β-oxidation, which produces acyl-CoA intermediates such as enoyl-CoA, 3-ketoacyl-CoA, and/or S-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA when fatty acids are used as the sole carbon sources (see review in reference 10). Recently, Campos-Garcia and coworkers have cloned and characterized an NADPH-dependent reductase (RhlG)-encoding gene from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (2). It was demonstrated that RhlG is involved in rhamnolipid and PHA synthesis, presumably converting 3-ketoacyl esters to 3-hydroxyacyl esters (2). However, their results also suggested that reductases other than RhlG might be present in P. aeruginosa. This prompted us to investigate the existence of other reductases that might be specifically involved in mcl-PHA synthesis. Since Escherichia coli with a complete and not inhibited β-oxidation cycle is unable to synthesize mcl-PHAs, even when equipped with a PHA polymerase-encoding gene of Pseudomonas (9, 12, 13), we chose E. coli as a model system to study the role of ketoacyl reductases from P. aeruginosa in mcl-PHA production. While the present paper was being reviewed, E. coli NADPH-dependent 3-ketoacyl reductase (FabG), which catalyzes ketoacyl-ACP to 3-hydroxyacyl-ACP during fatty acid synthesis and has been well studied (3), was overproduced in E. coli recombinants carrying phaC, and PHA accumulation was observed in these recombinants (18). In this study, we demonstrated that P. aeruginosa FabG, the sequence of which has been determined, but the enzymatic properties and functions of which have not been addressed experimentally, can be involved in mcl-PHA synthesis.

Cloning of a ketoacyl reductase-encoding gene of P. aeruginosa PAO1.

To investigate whether a specific mcl-ketoacyl-CoA reductase which is exclusively involved in mcl-PHA synthesis is present in P. aeruginosa, the genomic DNA sequence of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (www.pseudomonas.com [release of March 1999]) was searched for homologous regions to the acetoacetyl-CoA reductase-encoding genes from Alcaligenes sp. strain SH-69 (accession no. AF002014), Acinetobacter sp. strain RA3849 (accession no. L37761), Paracoccus denitrificans (accession no. D49362), Chromatium vinosum D (accession no. A27012), Ralstonia eutropha H16 (accession no. J04987) and Rhizobium meliloti 41 (accession no. U17226). One fragment located in contig 50 of the Pseudomonas Genome Project was found to have the highest homology to the known acetoacetyl-CoA reductase-encoding genes. Sequence analysis revealed that this fragment contains the fabG gene (GenBank database accession no. U91631), which was recently identified as part of a fabD-fabG-acpP-fabF gene cluster and encodes the 3-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) reductase (7). The deduced amino acid sequences of FabG showed an overall 30 to 35% identity to the known acetoacetyl-CoA reductases and 32 to 55% identity to FabG enzymes from other origins. The entire fabG gene was subsequently cloned from PAO1 by using the PCR primers 5′-TGGCTCGAGAGAGAGAAAGGAGA-3′ and 3′-CAGATCTTAAGCAACGCCTT-5′. PCR amplifications using total P. aeruginosa PAO1 DNA, Taq DNA polymerase (Promega), and a Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp PCR System 9600 were carried out. After restriction with XhoI and EcoRI, the PCR product was cloned into SalI- and EcoRI-digested pUC19 to generate pET201. Since pET201 was found unstable in E. coli recombinants (data not shown), plasmid pET200 was constructed as follows. pET201 was digested with EcoRI and HindIII. The 750-bp fabG-containing fragment obtained was then inserted into pBCKS (Promega) to get pET202, which was further cut with BamHI and KpnI, and the fabG-containing fragment was then ligated into pCK01 (4), resulting in pET200.

Ketoacyl-CoA reductase activity of FabG in recombinant E. coli.

In order to determine whether the cloned fabG gene product of P. aeruginosa is active toward CoA esters, thus providing a substrate for the PHA polymerase, pET200 was transformed into E. coli hosts MF4100 (fadR) (derived from MC4100 [Biolabs]), RS3338 (fadR fadL; B. J. Bachman), JMU193 (fadR fadB) (15), and JMU194 (fadR fadA) (15). The fadR gene encodes a protein that exerts negative control over genes necessary for fatty acid oxidation (see review in reference 1). A mutation in fadR derepresses transcription of these genes, as a result of which the fad genes are constitutively expressed, rendering E. coli capable of growth on mcl fatty acids (1). Mutations in fadA or fadB block fatty acid oxidation and result in accumulation of specific acyl-CoA intermediates (15). E. coli hosts carrying pET200 were then analyzed for ketoacyl-CoA reductase activity. In analogy to the previously reported acetoacetyl-CoA reductase assay using different-chain-length 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA substrates (5), the FabG reductase was assayed with glycine-NaOH buffer (50 μmol [pH 9.0]), NADP+ (100 nmol), and 3-hydroxyoctanoyl-CoA (100 nmol), which was prepared according to the method described previously (6). The reaction was initiated with 3-hydroxyoctanoyl-CoA at 30°C. 3-Ketoacyl-CoA reductase activity was monitored by examining A340 due to the reduction of NADP+ during oxidation of 3-hydroxyoctanoyl-CoA (5).

E. coli MF4100, RS3338, JMU193, and JMU194 carrying pET200 exhibited a relatively high ketoacyl-CoA reductase activity (from 50 to 90 mU/mg of total protein), whereas the control strains harboring vector pCK01 showed only a background reductase activity (10 to 20 mU/mg of protein), which is probably caused by the FabG of E. coli. These results strongly indicate that FabG of P. aeruginosa is able to use CoA esters as substrates.

mcl-PHA synthesis in E. coli recombinants expressing phaC and fabG of Pseudomonas.

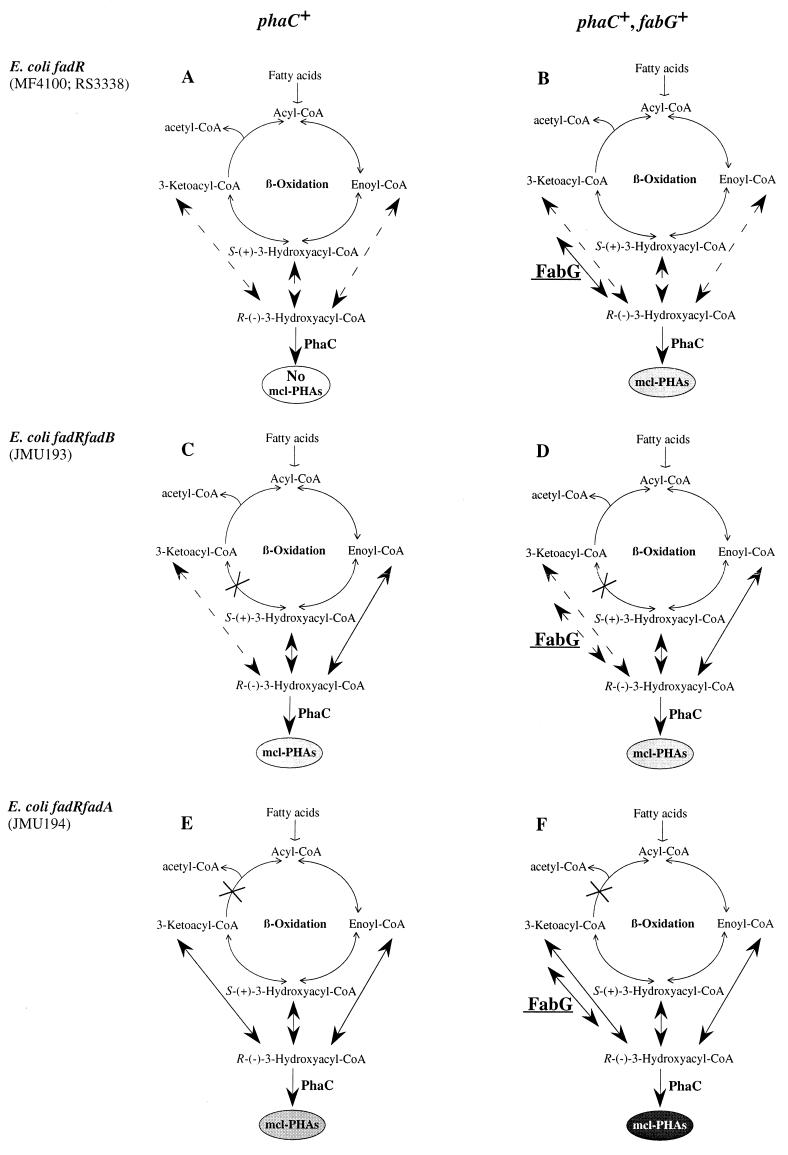

To synthesize mcl-PHA in recombinant E. coli, plasmid pBTC2 (14), which contains phaC2 of Pseudomonas oleovorans Gpo1, was used. MF4100 and RS3338 carrying pBTC2 and/or pET200 were cultivated in M9 minimal medium (16) with 10 mM sodium octanoate as a carbon source. For growth of the fadB- or fadA-negative E. coli strains JMU193 and JMU194 carrying pBTC2 and/or pET200, 0.2% (wt/vol) yeast extract was used as a carbon source and 2 mM hexadecanoate was added as a cosubstrate for PHA formation and growth. Cell cultures were induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) in the early exponential growth phase and harvested in the stationary phase. PHA accumulation and PHA composition were analyzed as previously described (8). No detectable PHA (less than 0.1% PHA of cell dry weight) was found in either E. coli MF4100 or RS3338 harboring phaC only (Table 1). Addition of fabG in both E. coli recombinants resulted in about 3% PHA with a composition similar to that found in wild-type Pseudomonas strains (8) (Table 1). Therefore, we concluded that fabG of P. aeruginosa facilitated PHA production in these strains, supporting the notion that FabG channels β-oxidation intermediates, probably 3-ketoacyl-CoAs, to the PHA polymerase in E. coli fadR recombinants (Fig. 1B versus A). To further verify this hypothesis, E. coli mutants JMU193 and JMU194, which are deficient in β-oxidation steps downstream and upstream of the formation of 3-ketoacyl-CoA, respectively, were further investigated for PHA production when carrying the phaC and/or fabG gene (Fig. 1C to F). Without the fabG gene, JMU193 and JMU194 carrying phaC (Fig. 1C and E) accumulated PHA to levels of about 5 and 14%, respectively (Table 1). Addition of fabG in JMU193 carrying phaC did not cause significant changes in PHA content or composition (Table 1). Introduction of fabG to recombinant JMU194 carrying phaC resulted in increased PHA production to 20%, however, confirming that FabG might be capable of converting 3-ketoacyl-CoAs to 3-hydroxyacyl-CoAs (Fig. 1F). To prove that the 3-hydroxyalkanoate compounds obtained are not due to accumulated monomers, we isolated and determined the Mw of the polymers described above as detailed in reference 11. The Mw of the polymers isolated from the recombinants was significantly lower (Table 1) than the Mw of the polymer produced by the wild-type organisms (11). In all E. coli recombinants tested, PHA was never found in cells harboring the ketoacyl reductase-encoding fabG gene without phaC.

TABLE 1.

Accumulation of PHA in recombinant E. coli strains carrying pET200 and pBTC2a

| Strain | Plasmid(s) | Gene (relevant markers) | PHA content (% cell dry wt) | Composition (mol%)b

|

Mw | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3HHx | 3HO | 3HD | |||||

| MF4100 | pBTC2 | phaC+ | —c | — | — | ||

| pBTC2, pET200 | phaC+, fabG+ | 2.8 | 10 | 90 | 0 | 48,200 | |

| RS3338 | pBTC2 | phaC+ | — | — | — | ||

| pBTC2, pET200 | phaC+, fabG+ | 3.1 | 9 | 91 | 0 | 51,100 | |

| JMU193 | pBTC2 | phaC+ | 4.6 | 11 | 76 | 13 | 56,400 |

| pBTC2, pET200 | phaC+, fabG+ | 5.2 | 10 | 77 | 13 | 52,700 | |

| JMU194 | pBTC2 | phaC+ | 14.2 | 20 | 67 | 13 | 68,300 |

| pBTC2, pET200 | phaC+, fabG+ | 20.6 | 23 | 65 | 12 | 67,000 | |

E. coli recombinants were cultivated as described in the text. Determination of the PHA content and the PHA molecular weight was carried out as described previously (8, 11). Average data of three independent experiments are given.

3HHx, 3-hydroxyhexanoate; 3HO, 3-hydroxyoctanoate; 3HD, 3-hydroxydecanoate.

—, <0.1%.

FIG. 1.

Possible pathways for PHA synthesis in recombinant E. coli from alkanoates via β-oxidation cycle. Dashed lines indicate pathways or reactions that are theoretically possible, but the precursor concentrations might be too low to permit the reaction to take place. Crosses indicate a blocking of the enzymatic reaction. Amounts of PHA are indicated by the density of shading: higher intensity corresponds to larger amounts of PHA.

Summary.

Since P. aeruginosa may have several reductases which are involved in PHA synthesis (2), attempts to knock out fabG in P. aeruginosa have failed (Q. Ren et al., unpublished data), and deletion of fabG in E. coli was lethal to the cells (19), we chose a heterologous system in E. coli to study the function of P. aeruginosa FabG and its involvement in PHA production.

Our data confirmed the results obtained in parallel by Taguchi et al. (18), i.e., reduction of 3-ketoacyl-CoA is a channeling pathway for supplying 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA monomer units for PHA synthesis through fatty acid degradation and established a role for FabG in PHA synthesis. In addition to the in vivo studies and the in vitro NADPH-dependent reductase activity toward acetoacetyl-CoA determined for E. coli FabG (18), we could demonstrate in vivo and in vitro that FabG of P. aeruginosa has activity toward mcl-ketoacyl-CoA substrates. Furthermore, we proved that a polymer was produced, albeit, with low molecular weight. According to our data presented in this paper combined with data from previous research (9, 13), we propose the following model for mcl-PHA synthesis in E. coli (Fig. 1). In E. coli fadR hosts, acyl-CoAs of different chain lengths that are derived from alkanoates are degraded via the β-oxidation cycle, resulting in the formation of ketoacyl-CoA intermediates of different chain lengths. These intermediates are converted to R-3-hydroxyacyl-CoAs by an R-specific ketoacyl-CoA reductase encoded by fabG, and the resultant R-3-hydroxyacyl-CoAs with 6 to 10 carbon atoms are incorporated into a growing polyester chain by PHA polymerase. In the fadB mutant JMU193, blocking of the 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (Fig. 1C) reduces the available ketoacyl-CoA level (13). As a consequence, introduction of fabG (Fig. 1D) did not significantly increase the amount of PHA formed. In contrast, blocking of the ketoacyl-CoA thiolase in the fadA mutant JMU194 increased the available ketoacyl-CoA level (Fig. 1E) (13), resulting in an increased amount of PHA after introduction of fabG (Fig. 1F and Table 1). The substrate range of FabG of P. aeruginosa is not known yet. Since this enzyme is likely involved in fatty acid synthesis, it might process substrates with carbon chain length up to C18 as well as ACP-coupled substrates. If so, this explains why no significant changes of monomer composition could be detected in any of the E. coli recombinants tested (Table 1).

Although we could demonstrate that FabG of P. aeruginosa is capable of providing precursors for mcl-PHA in recombinant E. coli, we cannot rule out the possibility that another 3-ketoacyl-CoA reductase is present in P. aeruginosa that is exclusively responsible for mcl-PHA production in the native strain. This deserves further investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Röthlisberger for DNA sequencing, G. Frank for N-terminal sequencing of the protein, D. Dennis for providing strains JMU193 and JMU194, and M. A. Prieto for providing strain MF4100.

This work was supported by grants from the Swiss Federal Office for Education and Science (BBW no. 96.0348) to Q.R.

REFERENCES

- 1.Black P N, DiRusso C C. Molecular and biochemical analyses of fatty acid transport, metabolism, and gene regulation in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1210:123–145. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)90113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campos-Garcia J, Caro A D, Nájera R, Miller-Maier R M, Al-Tahhan R A, Soberón-Chávez G. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa rhlG gene encodes an NADPH-dependent β-ketoacyl reductase which is specifically involved in rhamnolipid synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4442–4451. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4442-4451.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cronan J E, Rock C O. Biosynthesis of membrane lipids. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 612–636. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernández S, de Lorenzo V, Pérez-Martin J. Activation of the transcriptional regulator XylR of Pseudomonas putida by release of repression between functional domains. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haywood G W, Anderson A J, Chu L, Dawes E A. The role of NADH- and NADHP-linked acetoacetyl-CoA reductases in the poly-3-hydroxybutyrate synthesizing organism Alcaligenes eutrophus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1988;52:259–264. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraak M N, Kessler B, Witholt B. In vitro activities of granule-bound poly[(R)-3-hydroxyalkanoate] polymerase C1 of Pseudomonas oleovorans: development of an activity test for medium-chain-length-poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) polymerases. Eur J Biochem. 1997;250:432–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.0432a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kutchma A J, Hoang T T, Schweizer H P. Characterization of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa fatty acid biosynthetic gene cluster: purification of acyl carrier protein (ACP) and malonyl-coenzyme A:ACP transacylase (FabD) J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5498–5504. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5498-5504.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lageveen R G, Huisman G W, Preusting H, Ketelaar P, Eggink G, Witholt B. Formation of polyesters by Pseudomonas oleovorans: effect of substrates on formation and composition of poly-(R)-3-hydroxyalkanoates and poly-(R)-3-hydroxyalkenoates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2924–2932. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.12.2924-2932.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langenbach S, Rehm B H A, Steinbüchel A. Functional expression of the PHA synthase gene phaC1 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Escherichia coli results in poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) synthesis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;150:303–309. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1097(97)00142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madison L L, Huisman G W. Metabolic engineering of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates): from DNA to plastic. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:21–53. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.21-53.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Preusting H, Nijenhuis A, Witholt B. Physical characteristics of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) and poly(3-hydroxyalkenoates) produced by Pseudomonas oleovorans grown on aliphatic hydrocarbons. Macromolecules. 1990;23:4220–4224. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qi Q S, Steinbüchel A, Rehm B H A. Metabolic routing towards polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthesis in recombinant Escherichia coli (fadR): inhibition of fatty acid beta-oxidation by acrylic acid. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;167:89–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ren Q. Biosynthesis of medium chain length poly-3-hydroxyalkanoates: from Pseudomonas to Escherichia coli. Ph.D. thesis. Zürich, Switzerland: Eidgenössische Techinsche Hochschule Zürich (ETHZ); 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ren Q, Sierro N, Kellerhals M, Kessler B, Witholt B. Properties of engineered poly-3-hydroxyalkanoates produced in recombinant Escherichia coli strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:1311–1320. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.4.1311-1320.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhie H G, Dennis D. Role of fadR and atoC(Con) mutations in poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) synthesis in recombinant pha+Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2487–2492. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2487-2492.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinbüchel A. PHB and other polyhydroxyalkanoic acids. In: Rehm H-J, Reed G, editors. Biotechnology. Weinheim, Germany: VCH; 1996. pp. 405–464. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taguchi K, Aoyagi Y, Matsusaki H, Fukui T, Doi Y. Co-expression of 3-ketoacyl-ACP reductase and polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase genes induces PHA production in Escherichia coli HB101 strain. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;176:183–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Cronan J E., Jr Transcriptional analysis of essential genes of the Escherichia coli fatty acid biosynthesis gene cluster by functional replacement with the analogous Salmonella typhimurium gene cluster. J Biol Chem. 1999;180:3295–3303. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.13.3295-3303.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]