Abstract

Introduction

In Liberia, emergency care is still in its early development. In 2019, two emergency care and triage education sessions were done at J. J. Dossen Hospital in Southeastern Liberia. The observational study objectives evaluated key process outcomes before and after the educational interventions.

Methods

Emergency department paper records from 1 February 2019 to 31 December 2019 were retrospectively reviewed. Simple descriptive statistics were used to describe patient demographics and χ2 analyses were used to test for significance. ORs were calculated for key predetermined process measures.

Results

There were 8222 patient visits recorded that were included in our analysis. Patients in the post-intervention 1 group had higher odds of having a documented full set of vital signs compared with the baseline group (16% vs 3.5%, OR: 5.4 (95% CI: 4.3 to 6.7)). After triage implementation, patients who were triaged were 16 times more likely to have a full set of vitals compared with those who were not triaged. Similarly, compared with the baseline group, patients in the post-intervention 1 group had higher odds of having a glucose documented if they presented with altered mental status or a neurologic complaint (37% vs 30%, OR: 1.7 (95% CI: 1.3 to 2.2)), documented antibiotic administration if they had a presumed bacterial infection (87% vs 35%, OR: 12.8 (95% CI: 8.8 to 17.1)), documented malaria test if presenting with fever (76% vs 61%, OR: 2.05 (95% CI: 1.37 to 3.08)) or documented repeat set of vitals if presenting with shock (25% vs 6.6%, OR: 8.85 (95% CI: 1.67 to 14.06)). There was no significant difference in the above process outcomes between the education interventions.

Conclusion

This study showed improvement in most process measures between the baseline and post-intervention 1 groups, benefits that persisted post-intervention 2, thus supporting the importance of short-course education interventions to durably improve facility-based care.

Keywords: accident & emergency medicine, education & training (see medical education & training), medical education & training

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This study contributes to limited research on educational interventions in low-income and middle-income countries—where emergency care is in its infancy—by evaluating changes in care processes as a result of educational interventions.

This study evaluated both paediatric and adult populations which fully represents the patient population presenting to the emergency department.

This is an observational cross-sectional study, so causality cannot be established.

This is a single centre study and generalisability of results is unknown.

The study design retrospectively reviewed documents and did not include direct observations which may not fully represent actual practice.

Introduction

Emergency care has been increasingly recognised as a fundamental component to strengthening health systems1–5 and an effective means to address multiple Sustainable Development Goals and reduce the overall burden of disease.1 6 An estimated 54% of annual deaths in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) could be addressed by prehospital and hospital-based emergency care.7 More specifically, injury-related mortality disproportionately effects LMICs, and accounts for more than 90% of the total global mortality related to injury.8 Timely emergency care saves lives across the spectrum of illness from injuries to acute presentations of chronic disease and is the first contact with the health system for many individuals.1 2 9 10

Emergency care in Liberia, like many LMICs, is still in its early development. In 2007, emergency care was first included in Liberia’s national health plan and basic package of health services.11 12 There has been some development of emergency education at the national referral hospital in the capital of Monrovia; however, no other consistent or standardised emergency medicine curriculum has been established.13 The basic package of health services outlines the essentials of emergency care for each level of service.11 Currently, there are no formal indicators measuring care or process outcomes for emergency care nationally.

In 2014, the Ebola outbreak led to the near-collapse of the country’s already weakened health system, which was recovering from recent civil war (1989–1996 and 1999–2003).13–15 In 2015, responding to the Ebola epidemic, the global non-profit organisation Partners In Health (PIH), at the invitation of and in partnership with the Liberian government, came to Liberia to support the emergency response and long-term strengthening of the health system. Given clear emergency care needs in Maryland County, a key goal of PIH’s became to expand and strengthen emergency services, which included developing the health workforce capacity to provide high-quality emergency care with the support of emergency care education sessions and triage implementation. The objective of this observational study was to evaluate key process outcomes before and after triage implementation and emergency care education interventions to assess its impact on quality of care and identify areas for future improvement.

Methods

Study design

An observational, retrospective cross-sectional study of patients presenting to a regional hospital emergency department (ED) in Southeastern Liberia.

Study setting

The observational study was carried out at J.J. Dossen (JJD) hospital, the only county referral hospital in rural, Southeastern Liberia. It is a government-run hospital supported by PIH and provides services free of charge. JJD serves a primary catchment area of 187 000 people in Maryland county, and receives additional referrals from neighbouring counties.16 At the time of the education interventions, JJD’s eight-bed ED was primarily staffed by nurses and physician assistants (PA). There was no trained emergency medicine physician at the hospital. Specialists in the four core clinical departments of paediatrics, internal medicine, surgery and obstetrics and gynaecology provide back-up clinical support to the ED in their respective clinical areas as needed. Prior to 2019, none of the ED staff had specific emergency care education courses. In addition to nurses and PAs, nursing aides and nursing students worked within the ED; after triage was implemented in May 2019, nursing aides primarily staffed ED triage.

Education interventions

A series of education interventions were undertaken with ED staff, that included both nurses and physician assistants, to train them on the implementation of the Integrated Interagency Triage Tool (IIATT) and completion of the WHO Basic Emergency Care course. For the first intervention, a series of education sessions were conducted to improve emergency care at JJD in late April and early May 2019. First, staff were trained on the WHO-ICRC-MSF integrated interagency triage tool through didactics followed by real-time supervision and mentorship on the implementation of triage.17–19 Triage is an essential component of emergency care; it evaluates a patient’s acuity and prioritises evaluation and treatment based on the severity of the patient’s condition.6 The IIATT assigns patients to a three-tier acuity system, based on specified symptoms, physical signs and high risk vital signs.17–19

Following the IIATT training, 12 staff received 2 weeks of education on the WHO Basic Emergency Care (BEC) course, followed by the complementary PIH Fundamentals of Emergency Care training. The WHO BEC course was composed of didactic, small group sessions and skills sessions, designed to train staff to identify and manage acute illnesses and injuries with limited resources.20 21 The supplemental PIH course included additional topics (eg, approach to conditions such as abdominal pain and fevers), and skills such as basic EKG (electrocardiogram) and ultrasound. The didactic courses were followed by 2 weeks of clinical mentorship by a visiting faculty emergency physician. Afterwards, ongoing occasional clinical mentorship was supported by non-EM faculty who worked at JJD.

In mid-October 2019, 16 JJD staff participated in a 3-day refresher education session. Five participants had not completed the initial education intervention, so received a precourse 1 day intensive training on key concepts covered previously. An emergency physician assistant provided ongoing clinical mentorship 4 days a week for the subsequent 3 months.

Study population

The study was conducted from 1 February 2019 to 31 December 2019. During this period, all patients presenting to the JJD ED for whom a visit was either documented in the ED ledger or a separate paper chart were included in the study.

Data collection

Trained data collectors extracted information from the paper ED records into a predeveloped data extraction tool. Prior to May 2019, all visit documentation occurred exclusively in the ED ledger, including demographics, reason for the visit, vital signs, lab testing, key results, diagnosis and disposition. After May 2019, documentation included three sources: the ED ledger, an ED triage form and a ED provider documentation form adapted from the WHO Emergency Unit forms.22 These forms were introduced in May 2019 and used by staff performing the initial evaluation and resuscitation. The ED ledger was a bound book with paper records, described above. The ED triage form documented triage acuity based on presenting symptoms and vital signs based on the interagency integrated triage tool. The ED provider documentation form included sections for vital signs, chief complaint, primary survey, history of presenting illness, review of systems, past medical history, assessment and plan. Data collectors reviewed all these source and recorded demographics, initial vital signs, select clinical process measures and outcome variables.

Variables and outcomes

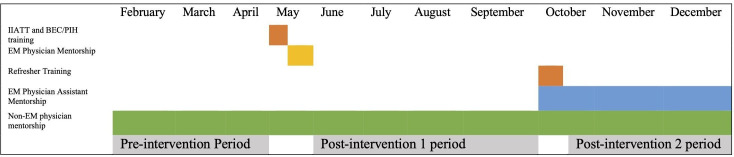

We classified visits from 1 February 2019 to 30 April 2019 as ‘pre-intervention’, visits from 29 May 2019 to 13 October 2019 as ‘post-intervention 1’, and 21 October 2019 to 31 December 2019 as ‘post-intervention 2.’ Visits from 1 May 2019 to 28 May 2019 and 14 October 2019 to 20 October 2019 were considered to be in ‘intermediate’ time periods (eg, time periods during the education sessions themselves) and excluded from comparative analyses (as seen in figure 1). Data with missing date and age variables were also excluded from the analysis.

Figure 1.

Education Intervention Timeline 2019: the timeline of the study including education session time periods, the time periods pre-interventions and post-interventions, as well as time periods where mentorship was provided. BEC, Basic Emergency Care; EM, Emergency Medicine; IIATT, Integrated Interagency Triage Tool; PIH, Partners In Health.

Due to differences in documentation standards prior to the ED education session, we focused our analyses on variables and process metrics that were reliably and routinely captured in the JJD ED register. The study team reviewed process metrics recommended by the African Federation of Emergency Medicine, as well as a review of quality metrics used in LMIC EDs.23 24 From these lists, study outcomes were chosen based on local context, hospital and government priorities and pre-existing documentation patterns that determined what baseline data was available. Outcomes focused primarily on the effectiveness domain of quality of care.25 The primary study outcome was a complete set of recorded vital signs at any time during the patient’s ED visit and was chosen given the importance of vital signs to triage and emergency care.26 27 A full set of vitals for patients aged 5 and over includes heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, blood pressure and temperature. A full set of vitals for patients under age 5 includes heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation and temperature. Blood pressure was not reliably recorded in this younger age group so was not included.

Secondary outcomes examined included documentation of blood glucose for patients presenting with altered mental status or a neurologic complaint; antibiotic administration or prescription in patients with a presumed bacterial infection; malaria diagnostic testing in patients with temperature ≥38°C; oxygen administration for hypoxia; repeat vital signs for shock; and intravenous fluids for shock (hypoxia and shock were defined by age, table 1). A physician assistant interpreted the final diagnoses to determine if the visit was due to a presumed bacterial infection. In the absence of microbiology capability to perform cultures and accounting for local context and practice patterns, all diagnoses of pneumonia, urinary tract infections, meningitis, cellulitis and sepsis were presumed to have been bacterial. Tuberculosis (TB) was excluded from the list of bacterial infections, as patients with TB are referred to TB clinic to initiate treatment and therefore not reliably documented as part of ED care. A patient was coded as a neurologic complaint if the clinical documentation included altered mental status, weakness, dizziness, or seizures.

Table 1.

Variable definitions

| Hypoxia | |

| Age ≤5 years | SpO2 ≤94% |

| Age >5 years | SpO2 ≤92% |

| Fever | Temperature ≥38℃ |

| Shock vitals | |

| Age 0 to <1 years* | HR >160 bpm |

| Age ≥1 to < 3 years* | HR >160 bpm |

| Age ≥3 to < 5 years* | HR >140 bpm |

| Age ≥5 to < 13 years | HR ≥130 bpm or a systolic blood pressure <70 mm Hg |

| Age ≥13 years | HR ≥130 bpm or a systolic blood pressure <80 mm Hg |

*Note: Blood pressure was not included as a criterion in the younger age groups as it is not reliably recorded.

HR, Heart rate; SpO2, Oxygen saturation.

Data analysis

Data were transcribed into Excel, then imported into and analysed with Stata (V.15).28 Simple descriptive statistics were used to describe the patient demographics and χ2 analyses were used to test for significance using a nominal threshold of 0.05. ORs and 95% CIs were calculated for predetermined process measurements as described above.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Results

There were 8774 patient visits recorded in the JJD ED from 1 February 2019 to 31 December 2019 and included in our analysis: 2732 in the pre-intervention time period, 3194 in the ‘post-intervention 1’ time period, 2296 in the ‘post-intervention 2’ time period and 552 in the ‘indeterminate’ time periods, which were excluded from the analysis (table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic description of gender and age at J.J. Dossen Hospital*

| Age (years) | Male, n (%) | Female, n (%) | Gender missing, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

| 0 to <5 | 1102 (52.9) | 954 (45.8) | 29 (1.4) | 2085 (25.4) |

| 5 to <18 | 858 (47.6) | 917 (50.9) | 26 (1.4) | 1801 (21.9) |

| 18+ | 2015 (47.6) | 2183 (51.6) | 36 (0.9) | 4234 (51.5) |

| Age missing | 40 (39.2) | 56 (54.9) | 6 (5.9) | 102 (1.2) |

| Total | 4015 (48.6) | 4110 (54.9) | 97 (1.2) | 8222 |

*Includes all patients from pre-intervention, post-intervention 1 and post-intervention 2 time periods.

In the baseline time period, only 3.5% of patients had a complete set of vital signs documented (table 3). In both post-intervention 1 and post-intervention 2 time periods, patients had higher odds of having a documented full set of vital signs (16%, OR: 5.4 (95% CI: 4.3 to 6.7)). Adults were statistically more likely than children to have a documented full set of vitals (OR: 1.43 (95% CI: 1.26 to 1.62)) (table 4). Triage, implemented as part of the first education intervention, significantly influenced the likelihood of having a full set of vital signs recorded: patients who were triaged were 16 times more likely to have a full set of vitals compared with those in the same time periods who were not triaged (60% vs 8.6%, OR: 15.9 (95% CI: 13.37 to 18.91)). There was no difference in vital signs obtained by gender.

Table 3.

Documented vital signs measurement by intervention period

| Pre-intervention (n=2732) | Post-intervention1 (n=3194) | Post-intervention 2 (n=2296) | ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | OR* (95% CI) compared with pre-intervention | n (%) | OR* (95% CI) compared with pre-intervention | OR† (95% CI) compared with post-intervention 1 | |

| Heart rate | 925 (33.9) | 1763 (55.2) | 2.41 (2.17 to 2.67) | 1183 (51.5) | 2.08 (1.85 to 2.33) | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.96) |

| Respiratory rate | 132 (4.8) | 647 (20.3) | 5.00 (4.12 to 6.08) | 449 (19.6) | 4.79 (3.91 to 5.87) | 0.96 (0.84 to 1.10) |

| Oxygen saturation | 656 (24.0) | 1511 (47.3) | 2.84 (2.54 to 3.18) | 960 (41.8) | 2.27 (2.02 to 2.57) | 0.80 (0.72 to 0.89) |

| Blood pressure | 888 (32.5) | 1580 (49.5) | 2.03 (1.83 to 2.26) | 942 (41.0) | 1.44 (1.29 to 1.62) | 0.71 (0.64 to 0.79) |

| Temperature | 1721 (63.0) | 2201 (68.9) | 1.30 (1.17 to 1.45) | 1752 (76.3) | 1.89 (1.67 to 2.14) | 1.45 (1.28 to 1.64) |

| AVPU‡ | 0 | 458 (14.3) | n/a | 274 (11.9) | n/a | 0.81 (0.69 to 0.95) |

| Weight | 190 (7.0) | 715 (22.4) | 3.86 (3.26 to 4.57) | 456 (19.9) | 3.32 (2.77 to 3.97) | 0.86 (0.75 to 0.98) |

| Full set of vitals§ | 95 (3.5) | 516 (16.2) | 5.35 (4.27 to 6.70) | 372 (16.2) | 5.37 (4.25 to 6.77) | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.16) |

*ORs calculated with pre-intervention group as baseline odds.

†ORs calculated for post-intervention 2 group with post-intervention 1 group as baseline odds.

‡AVPU assesses level of consciousness as either Alert, responds to Verbal stimuli, responds to Pain, Unresponsive. It is a system to assess the level of consciousness in a patient.

§A full set of vitals for patients aged 5 and over includes heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, blood pressure and temperature. A full set of vitals for patients under age 5 includes heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation and temperature

Table 4.

Documented vital signs measurement by age group after initial intervention*

| Age 0 to <5 (n=1401) | Age 5 to <18 (n=1214) | Age 18+ (n=2801) | ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | OR† (95% CI) compared with age group 0 to <5 | n (%) | OR† (95% CI) compared with age group 0 to <5 | OR‡ (95% CI) compared with combined age group 0 to <18 | |

| Heart rate | 517 (36.9) | 526 (43.3) | 1.31 (1.12 to 1.53) | 1849 (66) | 3.32 (2.91 to 3.8) | 2.93 (2.62 to 3.27) |

| Respiratory rate | 245 (17.5) | 211 (17.4) | 0.99 (0.81 to 1.22) | 621 (22.2) | 1.34 (1.14 to 1.58) | 1.35 (1.18 to 1.54) |

| Oxygen saturation | 466 (33.3) | 432 (35.6) | 1.11 (0.94 to 1.30) | 1527 (54.5) | 2.4 (2.1 to 2.75) | 2.29 (2.05 to 2.56) |

| Blood pressure | 167 (11.9) | 399 (32.9) | 3.62 (3 to 4.42) | 1904 (68) | 15.68 (13.1 to 18.78) | 7.68 (6.8 to 8.68)§ |

| Temperature | 1107 (79) | 898 (74) | 0.75 (0.63 to 0.90) | 1898 (67.8) | 0.56 (0.48 to 0.65) | 0.64 (0.57 to 0.72) |

| AVPU¶ | 149 (10.6) | 142 (11.7) | 1.11 (0.87 to 1.42) | 418 (14.9) | 1.47 (1.21 to 1.8) | 1.4 (1.19 to 1.64) |

| Weight | 528 (37.7) | 304 (25) | 0.55 (0.47 to 0.65) | 324 (11.6) | 0.22 (0.18 to 0.25) | 0.28 (0.24 to 0.32) |

| Full set of vitals** | 216 (15.4) | 134 (11) | 0.58 (0.54 to 0.86) | 520 (18.6) | 1.25 (1.05 to 1.49) | 1.48 (1.27 to 1.71) |

*This includes all patients after post-intervention 1 and post-intervention 2 (excluding those in the pre-intervention, intermediate time period and those patients missing an age).

†ORs calculated with age group 0–5 as baseline odds.

‡ORs calculated for combined age group 18+ with combined age groups 0 to <5 and 5 to <18 as baseline odds.

§Note that blood pressure may be less reliably measured.

¶AVPU: Alert, Verbal, Pain, Unresponsive. It is a system to assess the level of consciousness in a patient.

**A full set of vitals for patients aged 5 and over includes heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, blood pressure and temperature. A full set of vitals for patients under age 5 includes heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation and temperature.

All process outcomes measured showed significant quality improvements in the post-intervention groups compared with the baseline group, except the percent of patients with shock documented to receive intravenous fluids (table 5). After the initial education session, patients had higher odds of having a glucose documented for altered mental status or neurologic complaints (37% vs 30%, OR: 1.7 (95% CI: 1.3 to 2.2)). Patients also had higher odds of having antibiotics documented for presumed bacterial infections (87% vs 35%, OR: 12.8 (95% CI: 8.8 to 17.1)) and documented malaria diagnostic testing for fever (76% vs 61%, OR: 2.05 (95% CI: 1.37 to 3.08)) in the post-intervention 1 time periods. Additionally, patients presenting with shock were more likely to have a repeat set of vital signs documented (25% vs 6.6%, OR: 8.85 (95% CI: 1.67 to 14.06)). Although there was no statistically significant difference between pre-intervention and post-intervention 1 in patients presenting with hypoxia documented to receive oxygen, there was a statistical difference between post-intervention 2 and pre-intervention time periods (35.7% vs 11.1%, OR: 4.44 (95% CI: 1.15 to 17.25)). There were no significant differences between the post-intervention 1 and post-intervention 2 groups on any metrics. Metrics did not vary significantly by age group.

Table 5.

Documented process outcomes by intervention period

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention 1 | Post-intervention 2 | ||||

| n of total (%) |

n of total (%) | OR* (95% CI) compared with pre-intervention | n of total (%) | OR* (95% CI) compared with pre-intervention | OR† (95% CI) compared with post-intervention 1 | |

| Glucose test documented, among those with a neurologic chief complaint | 145 of 560 (25.9) | 254 of 672 (37.1) | 1.74 (1.36 to 2.22) | 169 of 469 (35.2) | 1.61 (1.23 to 2.11) | 0.93 (0.73 to 1.18) |

| Antibiotics documented, among those with a final diagnosis of presumed bacterial infection | 154 of 441 (34.8) | 415 of 478 (86.5) | 12.28 (8.83 to 17.07) | 335 of 388 (85.7) | 11.78 (8.30 to 16.71) | 0.96 (0.65 to 1.42) |

| Malaria test recorded, among those with a documented fever | 139 of 229 (60.7) | 168 of 221 (76.0) | 2.05 (1.37 to 3.08) | 179 of 242 (74.0) | 1.84 (1.24 to 2.72) | 0.91 (0.59 to 1.38) |

| Oxygen delivery recorded, among those with documented hypoxia | 3 of 27 (11.1) | 20 of 71 (28.2) | 3.14 (0.85 to 11.59) | 15 of 42 (35.7) | 4.44 (1.15 to 17.25) | 1.42 (0.63 to 3.20) |

| Repeat set of vital signs recorded, among those with initial shock vital signs‡ | 4 of 61 (6.6) | 49 of 193 (25.4) | 8.85 (1.67 to 14.06) | 34 of 135 (25.2) | 4.80 (1.62 to 14.21) | 0.99 (0.60 to 1.64) |

| IVF documented, among those with initial shock vital signs‡ | 16 of 45 (35.6) | 41 of 192 (21.4) | 0.76 (0.39 to 1.49) | 23 of 135 (17.0) | 0.58 (0.28 to 1.19) | 0.76 (0.43 to 1.33) |

*ORs calculated with pre-intervention group as baseline odds.

†ORs calculated for post-intervention 2 group with post-intervention 1 group as baseline odds.

‡Shock identified by appropriate vital signs according to age.

IVF, intravenous fluids.

Discussion

The study evaluated key quality process metrics before and after emergency care education sessions at a rural Liberian hospital. Almost all metrics improved after the education sessions compared with baseline, though additional gains were not seen with a second clinical training. Notably, patients who were triaged in the post-intervention time periods showed significant gains in having full sets of vital signs documented compared with patients in the same time period who were not triaged. Our study supports clinical trainings and triage training and implementation as an important step in improving care quality.

Pre-intervention, few patients had full sets of vital signs documented. Vital signs are an essential part of a patient’s clinical evaluation, that can detect serious illness and help monitor for clinical deterioration.27 29 Post-interventions, the odds of having a full set of vitals increased fivefold. Notably, patients who were triaged were nearly 16 times as likely to have a full set of vitals than those who were not, even in the same time period, suggesting that small interventions can be associated with improved emergency care.

Despite these gains, few patients overall had a full set of vitals documented post-interventions (16.2%). There are several likely contributing factors to this. First, due to the limited human resources, triage was inconsistently implemented. Without triage, vitals were performed by the providers themselves as they evaluated patients. Due to the volume of patients, boarding patients within the ED, and human resource constraints, anecdotal reports suggest providers often only obtained partial or forwent vitals due to time pressure. In addition, providers were observed to not consistently record vitals they obtained, particularly when the ED was very busy. Additionally, equipment constraints likely impacted efficiency, as vitals machines are limited, and with intermittent electricity, automated machines were not always functional. Similarly, limited availability of specific age-appropriate vital sign equipment may have led to variability among age groups.

Large gains were seen in documented antibiotic administration among patients with presumed bacterial infections and in patients with shock receiving repeat vital signs. Patients presenting to the ED with a presumed bacterial infection were over 12 times more likely to have antibiotics documented after the initial emergency care education session, and patients presenting to the ED in shock were nearly nine times more likely to have repeat vital signs documented. These significant gains have the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality from sepsis, a significant contribution to the burden of disease in LMICs.30 31 These findings suggest that limited emergency care education sessions are associated with improved quality of emergency care provided by front-line providers and nurses. There is also a possibility that any improvement in outcomes is unrelated to the education sessions and due to other factors not evaluated.

The similarity of outcomes in the post-intervention 1 and post-intervention 2 time periods may also be impacted by limitations of human resources and equipment. Staff turnover in the ED is relatively high. Attrition meant that 31% of the participants in intervention 2 were receiving initial training rather than retraining, possibly limiting impact. Also, the presence of ED-trained supervisors was intermittent, limiting the exposure of the staff to daily supervision and mentorship to help fortify the training. In addition, several of the process metrics depended on the availability of supplies or equipment. Our findings likely reflect a need for comprehensive health system strengthening, of which education sessions are only one component. Increases in overall health financing are also needed to expand the availability of staff and materials to improve patient care. Additionally, further evaluation is needed to identify the best ways for ongoing continuing medical education and staff support. Aside from these explanations, the similarity of outcomes in post-intervention 1 and post-intervention 2 time periods could reflect that the additional education session was necessary to ensure continued higher-quality care and to keep metrics stable. If the second educational intervention did not take place, it is possible the outcomes could have been worse, especially without daily supervision or mentorship.

Limitations

This study’s results must be considered within the context of its design. One notable limitation is that our method of measuring process metrics was documentation by the ED care provider and not direct observation of whether the care was provided. Particularly in an understaffed environment with many competing clinical demands and without administrative processes to hold providers accountable for their documentation, documentation may lag behind actual performance of tasks. There is also the risk of bias where providers document inaccurately, however, we suspect that under-reporting was likely the larger contributor. In the local care context, care processes such as placing oxygen on the patient or giving intravenous fluids do not require an order and thus might not be documented in the patient chart.

Given data systems at the hospital, we relied on retrospective data entry from paper records. It is possible additional interventions or vital sign measurements were performed but not documented. There may be unknown missing patient data, due to mixed methods of chart documentation. There was potential for missing data in the month of June, which had less data points when compared with the remaining months. Second, although this study suggests the interventions are associated with increases in quality metrics, causality cannot be established. In addition, we cannot rule out confounding between metrics and/or unmeasured variables, for example if increased rates of full sets of vital signs measured contributed to a higher likelihood of receiving repeat vitals. Future studies should address this. Third, the study looked at interventions as binary variables, but did not assess if the details of the intervention were appropriate to an individual patient. For example, overall improvement in documentation over time could have impacted results as vital signs and/or recording of interventions could have been performed more often than what was previously captured. Additionally, as noted above, any increased or decreased accessibility to equipment or supplies could have unclear contributions to the results. Future randomised studies should be considered to quantify the impact. Finally, this study was conducted at a single site in rural Liberia that had not received any prior emergency care training and the generalisability of our findings is unknown.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated an improvement in most process metrics after the implementation of triage and emergency care training in rural Liberia, supporting the utility of short-course interventions on facility-based care. This complements other evaluations of BEC trainings, which demonstrated increased emergency care knowledge and confidence.20 21 However, additional gains were not seen with a retraining several months later. Further exploration is needed to determine and intervene on other factors that influence quality metrics as well as the best methods for ongoing continued medical education and staff support.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @psonenthal

Contributors: KT, ID, AEP, VK, RHM, PU, RC and SAR contributed to study design. KT, ID, AEP, NL, VK, RHM, MH, AB, RC and SAR implemented the emergency care trainings. KT, ID, DD, TD and SM contributed to data collection. KT, ID, JG, PS and SAR contributed to data analysis. All authors contributed to interpretation of study results. KT and ID drafted the initial version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript and have approved the final manuscript version. KT and ID were equal contributors. KT is responsible for this paper and content as a guarantor.

Funding: This work was funded by the Ansara Family Foundation; funders did not have any role in study design or the analysis or publication of results.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Partners Healthcare IRB 2019P001944 as well as approved under the University of Liberia-Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation IRB 17-06-048 as part of the clinical and training protocol that Partners In Health Liberia submits annually for review.

References

- 1.Jamison DT, Gelband H, Horton S, et al. Disease control priorities, third edition (volume 9): improving health and reducing poverty. 2017. 10.1596/978-1-4648-0527-1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Anderson PD, Suter RE, Mulligan T, et al. World health assembly resolution 60.22 and its importance as a health care policy tool for improving emergency care access and availability globally. Ann Emerg Med 2012;60:35–44. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seventy-Second World Health Assembly . Emergency care systems for universal health coverage: ensuring timely care for the acutely ill and injured. n.d. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/emergency-care-systems-for-universal-health-coverage-ensuring-timely-care-for-the-acutely-ill-and-injured

- 4.Razzak JA, Kellermann AL. Emergency medical care in developing countries: is it worthwhile? Bull World Health Organ 2002;80:900–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson P, Petrino R, Halpern P, et al. The globalization of emergency medicine and its importance for public health. Bull World Health Organ 2006;84:835–9. 10.2471/blt.05.028548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Risko N, Chandra A, Burkholder TW, et al. Advancing research on the economic value of emergency care. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001768. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thind A, Hsia R, Mabweijano J, et al. Essential surgery: disease control priorities 3rd edn. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gosselin RA, Spiegel DA, Coughlin R, et al. Injuries: the neglected burden in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:246–246a. 10.2471/blt.08.052290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calvello EJB, Broccoli M, Risko N, et al. Emergency care and health systems: consensus-based recommendations and future research priorities. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:1278–88. 10.1111/acem.12266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Razzak J, Usmani MF, Bhutta ZA. Global, regional and national burden of emergency medical diseases using specific emergency disease indicators: analysis of the 2015 global burden of disease study. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e000733. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministry of Health and Social Welfare Republic of Liberia . Basic package for health and social welfare services for liberia. 2008. Available: http://liberiamohsw.org/Policies%20&%20Plans/Basic%20Package%20for%20Health%20&%20Social%20Welfare%20for%20Liberia.pdf

- 12.Kruk ME, Rockers PC, Williams EH, et al. Availability of essential health services in post-conflict liberia. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:527–34. 10.2471/BLT.09.071068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hexom B, Calvello EJB, Babcock CA, et al. A model for emergency medicine education in post-conflict liberia. Af J Emerg Med 2012;2:143–50. 10.1016/j.afjem.2012.08.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McQuilkin PA, Udhayashankar K, Niescierenko M, et al. Health-Care access during the Ebola virus epidemic in liberia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017;97:931–6. 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Downie R. The road to recovery: rebuilding liberia’s health system. center for strategic and international studies. n.d. Available: https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/publication/120822_Downie_RoadtoRecovery_web.pdf

- 16.Government of the Republic of Liberia . 2008 national population and housing census: preliminary results. n.d. Available: https://www.emansion.gov.lr/doc/census_2008provisionalresults.pdf

- 17.Mitchell R, McKup JJ, Bue O, et al. Implementation of a novel three-tier triage tool in Papua New Guinea: a model for resource-limited emergency departments. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2020;5:100051. 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell R, Bue O, Nou G, et al. Validation of the Interagency integrated triage tool in a resource-limited, urban emergency department in Papua New Guinea: a pilot study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2021;13:100194. 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization . Clinical care for severe acute respiratory infection: toolkit COVID-19 adaptation [online]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2020. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331736 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olufadeji A, Usoro A, Akubueze CE, et al. Results from the implementation of the world Health organization basic emergency care course in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr J Emerg Med 2021;11:231–6. 10.1016/j.afjem.2021.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kivlehan SM, Dixon J, Kalanzi J, et al. Strengthening emergency care knowledge and skills in Uganda and Tanzania with the WHO-ICRC basic emergency care course. Emerg Med J 2021;38:636–42. 10.1136/emermed-2020-209718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization . Who standardized clinical form. 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-standardized-clinical-form

- 23.Broccoli MC, Moresky R, Dixon J, et al. Defining quality indicators for emergency care delivery: findings of an expert consensus process by emergency care practitioners in Africa. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000479. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aaronson EL, Marsh RH, Guha M, et al. Emergency department quality and safety indicators in resource-limited settings: an environmental survey. Int J Emerg Med 2015;8:39. 10.1186/s12245-015-0088-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization . Quality of care [online]. Geneva: World Health organization. 2022. Available: https://www.who.int/health-topics/quality-of-care#tab=tab_1

- 26.Cooper RJ, Schriger DL, Flaherty HL, et al. Effect of vital signs on triage decisions. Ann Emerg Med 2002;39:223–32. 10.1067/mem.2002.121524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeVita MA, Hillman K, Bellomo R, et al. Textbook of rapid response systems. In: Textbook of rapid response systems. Cham, 2017. 10.1007/978-3-319-39391-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brekke IJ, Puntervoll LH, Pedersen PB, et al. The value of vital sign trends in predicting and monitoring clinical deterioration: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 2019;14:e0210875. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators . Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 2020;396:1204–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stephen AH, Montoya RL, Aluisio AR. Sepsis and septic shock in low- and middle-income countries. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2020;21:571–8. 10.1089/sur.2020.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.