Abstract

Background

Patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases (ARD) are at a potentially higher risk for COVID-19 infection complications. Given their inherent altered immune system and the use of immunomodulatory medications, vaccine immunogenicity could be unpredictable with a suboptimal or even an exaggerated immunological response. The aim of this study is to provide real-time data on the emerging evidence of COVID-19 vaccines' efficacy and safety in patients with ARDs.

Methods

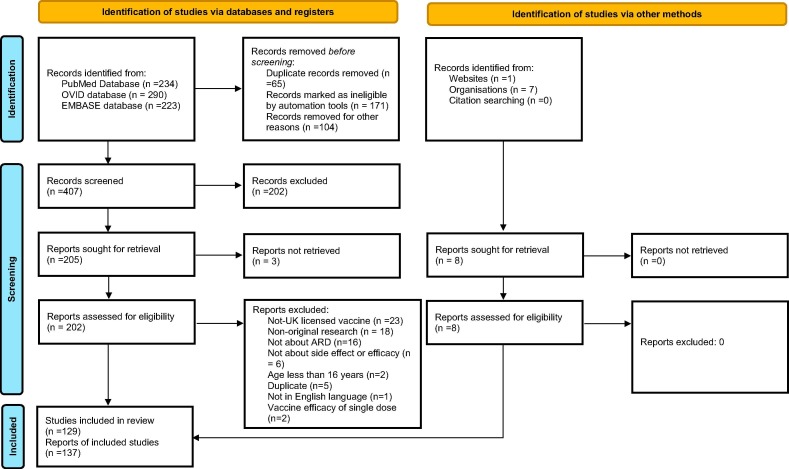

We performed a literature search of the PubMed, EMBASE, and OVID databases up to 11–13 April 2022 on the efficacy and safety of both types of the mRNA-vaccines and the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines in patients with ARD. The risk of bias in the retrieved studies was evaluated using the Quality in Prognostic Studies tool. Also, current clinical practice guidelines from multiple international professional societies were reviewed.

Results

We identified 60 prognostic studies, 69 case reports and case series, and eight international clinical practice guidelines. Our results demonstrated that most patients with ARDs were able to mount humoral and/or cellular responses after two doses of COVID-19 vaccine although this response was suboptimal in patients receiving certain disease-modifying medications including rituximab, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, daily glucocorticoids >10 mg, abatacept, as well as in older individuals, and those with comorbid interstitial lung diseases. Safety reports on COVID-19 vaccines in patients with ARDs were largely reassuring with mostly self-limiting adverse events and very minimal post-vaccination disease flares.

Conclusion

Both types of the mRNA-vaccines and the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines are highly effective and safe in patients with ARD. However, due to their suboptimal response in some patients, alternative mitigation strategies such as booster vaccines and shielding practices should also be followed. Management of immunomodulatory treatment regimens during the peri vaccination period should be individualized through shared decision making with patients and their attending rheumatologists.

Keywords: Adverse events, Autoimmune Rheumatic Disease, COVID-19 vaccine, Disease flare, Immunogenicity, Safety

1. Introduction

The intersection between coronavirus-19 disease (COVID-19) with autoimmunity has been well-recognized since the start of the pandemic [1]. The wide clinical spectrum of COVID-19 infection reflects a corresponding variable immune response mounted against the virus. All immune system components contribute to the immunological response against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) to eliminate the virus and recover from the infection. However, in patients with the most critical form of the infection, dysregulated immune response leads to deviation of the protective immunity causing severe inflammatory reactions, excessive cytokine release, and multisystem inflammatory syndrome [2].

The immune system utilizes a multi-layered approach to balance the immune reaction against true threats from antigens that should be ignored like self and inert environmental antigens [3]. The complex pathogenesis of ARDs is believed to result from a combination of genetic predisposition, environmental factors (including viral infections), and dysregulated immune response that triggers an imbalance between effector inflammatory pathways and tolerogenic control mechanisms which favors aberrant inflammatory response [4]. Many viral infections are implicated in the pathogenesis of multiple autoimmune rheumatological diseases [1]. Although this association has not yet been well understood, some of the postulated mechanisms include molecular mimicry, epitope spreading, bystander activation, and breaching of central or peripheral tolerogenic pathways [5]. On the other hand, epidemiological studies suggested that viral infections could also protect from autoimmunological pathologies through regulatory immune responses that suppress autoimmune phenomena [6].

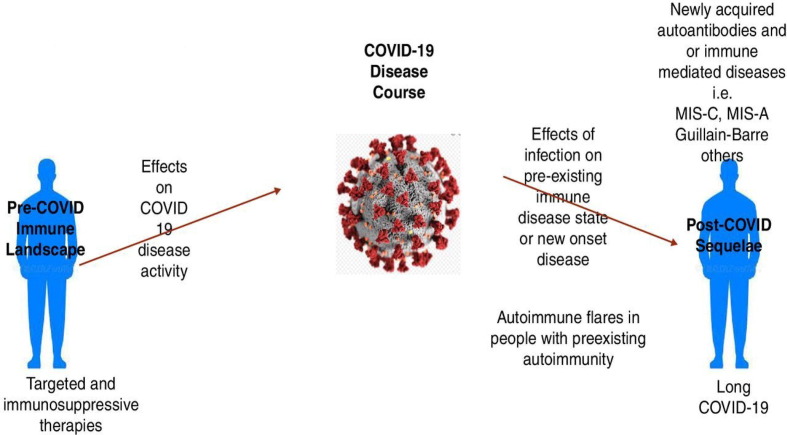

Managing ARD during the COVID-19 pandemic is challenging for both patients and healthcare providers. In addition to their inherently altered immune system, many patients receive immunomodulatory medications and are at higher risks for comorbid cardiovascular and/or interstitial lung diseases which further increase their risk for severe forms of COVID-19 infection [7]. Moreover, concerns were reported regarding the persistence and evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in immunocompromised patients leading to the emergence of virulent or vaccine-resistant variants [8]. Fig. 1 illustrates the bidirectional effects of COVID-19 disease with ARD [9].

Fig. 1.

The bidirectional relationship of COVID-19 with autoimmune rheumatic diseases[9]. Reproduced from [Rheumatology and COVID-19 at 1 year: facing the unknowns, Calabrese et al., 80, 2022] with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Several professional societies recommend COVID-19 vaccines for patients with ARD irrespective of their diagnosis or treatment regimen as the potential benefits outweigh the risks [10], [11]. However, many questions were raised regarding the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with ARD especially since those patients were largely excluded from the initial vaccine clinical trials [12]. This systematic review aims to critically review available data on the safety and efficacy of the two types of mRNA- and the adenoviral-vector AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines in patients with ARDs, and summarize the most updated international societies’ recommendations on their use in this unique population. In this paper, the term ‘COVID-19 vaccines’ refers to the two types of mRNA and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines unless specifically specified otherwise.

1.1. Overview of the mRNA and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines

Multiple COVID-19 vaccines were developed rapidly with the help of advanced health science technology. In the UK, and up to April 2022, three SARS-CoV-2 vaccines were approved and have been available for use which are: Moderna (mRNA-1273), Oxford/AstraZeneca (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19/AZD1222) and Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT162b2) vaccines [13]. The three vaccines use different vaccination platforms to stimulate the production of neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) against the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein. Therefore, they block the binding of viral particles with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors on the cell surface membrane preventing viral fusion [14].

1.2. mRNA vaccines

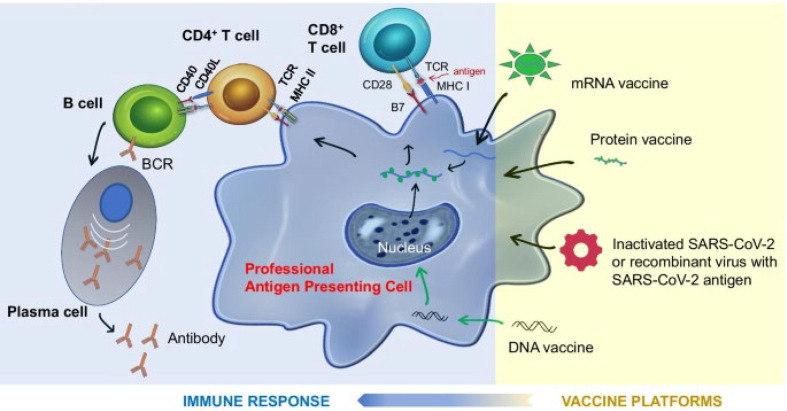

Both Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines utilize engineered RNA wrapped in lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) to generate full-length spike proteins in the cytoplasm without entering the cell nucleus. The LNPs stabilize the mRNA and work as adjuvants to induce B-cell and T-follicular helper cells' immunological reactions [15]. In this process, the S protein is presented by the major histocompatibility complexes class I and class II (MHC-I and MHC-II) to elicit CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell immunity resulting in memory T-cells and B-cells production with NAbs formation [15]. However, a single dose of either type of mRNA vaccine was found to be associated with more than 90 % efficacy in preventing symptomatic disease [16], [17]. Considering the low detectable titer of NAbs after a single dose of mRNA vaccine, Sadarangani et al. suggested that this early efficacy is mainly attributed to non-neutralizing antibodies immunity where innate immune mechanisms confer early protection by the production of type I or type III interferons leading to pathogen-agnostic protection [12].

1.3. Adenoviral-vectored vaccine

Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine uses a modified chimpanzee DNA adenovirus to deliver DNA vectors into the cellular cytoplasm which migrate to the nucleus afterward to produce S protein particles. Thereafter, S protein particles are expressed on the cellular surface membrane using MHC-I and MHC-II complexes which promote T-cells, B-cells and plasma cell activation [17]. Notably, a single dose of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine was found to stimulate polyfunctional antibodies including NAbs and other antibody-dependant effector functions. It was also shown to be associated with innate immunity stimulation by facilitating monocyte-mediated and neutrophil-mediated phagocytosis [14]. Moreover, in vitro studies demonstrated potent T-cell response in the form of tumor necrosis factor and interferon-gamma production from CD4+ T cells upon antigenic stimulation [18]. Fig. 2 illustrates the mechanism of action for multiple types of vaccination platforms [19].

Fig. 2.

Mechanism of action of different types of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, modes of antigen presentation and generation of protective immunity[19]. This image is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License found at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

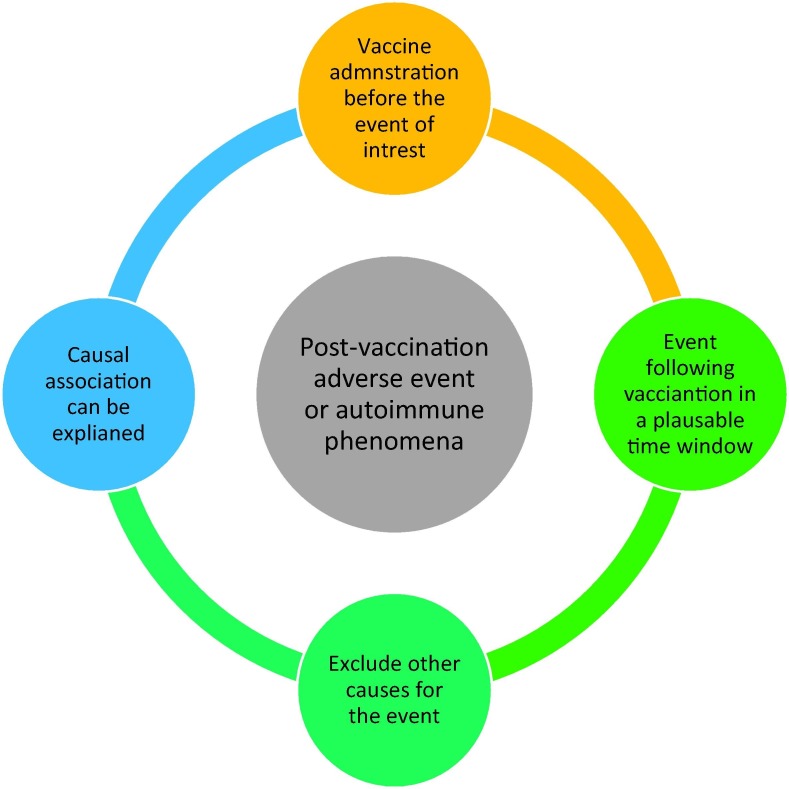

1.4. Definition of vaccine-related adverse events

According to the WHO guidelines, adverse events post-vaccination are defined as any unpleasant, unfavourable, or unintended medical events after vaccination that do not necessarily have a consistent or causal relationship with the vaccine [20]. Recently, the WHO proposed a comprehensive analytical and algorithmic four-step diagram to evaluate the causality of adverse events and autoimmune phenomena after COVID-19 vaccines as demonstrated in the diagram below (Fig. 3 ) [21].

Fig. 3.

Causality assessment of post-COVID-19 vaccination adverse events and autoimmune phenomena based on the WHO (2022) guidelines [21].

2. Methods

2.1. Research questions

The systematic review research questions and study outcomes are demonstrated in Table 1 .

Table 1.

The systematic review research questions and study outcomes.

| Research questions |

|

| The PICO question |

| P: Patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases |

| I: Receiving at least two doses of any of the UK-licensed COVID-19 vaccines |

| C: The population in the control group |

| O: Outcomes measures including: |

| Primary outcome: |

| Immunological response to COVID-19 vaccine defined by anti-SARS-COV-2 Antibody titer and/or cellular response measured by SARS-CoV-2 specific interferon release essay |

| Secondary outcomes: |

| Severity of breakthrough COVID-19 infection post vaccination defined according to the National Institute of Health 2021 criteria [27] (Supplementary Table 1) |

| Biological agents’ effects on COVID-19 vaccine immunological response |

| DMARDs’ effect on COVID-19 disease vaccine immunological response |

| Incidence of vaccine-related adverse events |

| Exacerbation of ARD activity |

| Precipitation of new-onset ARD |

2.2. Literature search

A literature search for this review was conducted in the databases of PubMed, EMBASE, and OVID with no restriction on the year of publication as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines as illustrated in Appendix 2 [22]. Table 2 shows the keywords used for each database search.

Table 2.

Keywords used for database search for this review.

| Database | Keywords |

|---|---|

| PubMed Date of search: 11th April 2022 |

(COVID-19 vaccine OR SARS-COV-2 vaccine) AND (Efficacy OR Effectiveness OR Safety) AND (autoimmune rheumatic diseases OR autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases OR connective tissue diseases OR rheumatoid arthritis OR systemic lupus erythematosus OR spondyloarthritis OR systemic sclerosis OR Sjögren’s’ syndrome OR inflammatory myopathy OR vasculitis) |

| OVID Date of search: 12th April 2022 |

((COVID-19 vaccine or SARS-COV-2 vaccine) and (efficacy or effectiveness or safety) and (autoimmune rheumatic disease or autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic disease or connective tissue disease or rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus or spondyloarthritis or systemic sclerosis or Sjogren's syndrome or inflammatory myopathy or vasculitis)).af. not (Review or Editorial).pt. |

| EMBASE Date of search: 13th April 2022 |

('covid-19 vaccine'/exp OR 'covid-19 vaccine' OR 'sars-cov-2 vaccine'/exp OR 'sars-cov-2 vaccine') AND ('efficacy'/exp OR efficacy OR effectiveness OR 'safety'/exp OR safety) AND ('autoimmune rheumatic diseases' OR 'autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases' OR 'connective tissue diseases'/exp OR 'connective tissue diseases' OR 'rheumatoid arthritis'/exp OR 'rheumatoid arthritis' OR 'systemic lupus erythematosus'/exp OR 'systemic lupus erythematosus' OR 'spondyloarthritis'/exp OR 'spondyloarthritis' OR 'systemic sclerosis'/exp OR 'systemic sclerosis' OR 'sjögren syndrome' OR 'inflammatory myopathy'/exp OR 'inflammatory myopathy' OR 'vasculitis'/exp OR 'vasculitis') |

2.3. Eligibility criteria

Articles identified by the defined search keywords were screened for the possibility of inclusion in this study based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria by two reviewers who worked independently. Any discrepancy in the screening process was resolved by a third reviewer.

2.3.1. Inclusion criteria

-

•

Original research

-

•

Patients aged ≥16 years

-

•

Written in the English language

-

•

Accessibility to the full text

2.3.2. Exclusion criteria

-

•

Non-original research including review articles, editorial papers, and study protocols

-

•

Pre-clinical trials, in vitro studies, reports on animal models

-

•

Phase-1 and phase-2 clinical trials.

-

•

Preprints

In addition, a selected number of international guidelines from relevant societies was assessed for relevance and their recommendations were summarized.

2.4. Study flow chart

The study flow chart is demonstrated in Fig. 4 .

Fig. 4.

Study flow diagram (adapted from updated 2020 PRISMA guideline [26]).

2.5. Data extraction and publication quality assessment

Data collection included study details about the authors, year of publication, region and time of data collection, type of population, sample size, study design, main topic, and key findings as summarised in supplementary Table 2. In addition, case reports and series which were identified by the search criteria were summarised in supplementary Table 3. The quality of included studies was assessed by two authors independently, and in case of disagreement by a third author, using the Quality in Prognostic Studies (QUIPS) tool developed by Hayden et al. (supplementary Table 4) [23]. This tool evaluates six areas that are considered important to judge the risk of bias in prognostic studies whenever possible which include population, study attrition, measurement of prognostic factors, confounding risk, outcome measures, and analysis.

2.6. Ethical consideration

This review article was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Faculty of Life Science and Education, University of South Wales, UK.

3. Results

3.1. Efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with ARD

3.1.1. Immune response to COVID-19 vaccines in patients with ARD

The efficacy profile of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with ARD is summarized in Table 3 . We identified 35 observational studies on the COVID-19 vaccine humoral response including 12 studies that also assessed the cellular response (supplementary Table 2). Most of the studies were conducted in Western countries and included patients with various forms of ARD (RA, SLE, systemic sclerosis, spondylarthritis, psoriatic arthritis, cryoglobulinemia, polymyalgia rheumatica, different types of vasculitis, and juvenile inflammatory arthritis). One study focused on older patients with ARD [24], and another one was conducted mainly on adolescents and young adults [25]. The number of patients included in individual studies varied from 12 to 686 participants with ARD. The most commonly used vaccines in the described studies were mRNA vaccines followed by the Adenoviral-vector vaccine AstraZeneca. Around half of the studies (18) had a moderate risk of bias according to the QUIPS tool, while 11 and 6 studies had low and high risks of bias respectively (supplementary Table 4).

Table 3.

Summarized study results on the efficacy of mRNA and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases.

| Immune Response after COVID-19 Vaccines in Patients with ARD | |

| Humoral response |

|

| Cellular response |

|

| Effect of Immunomodulatory Agents on COVID-19 Efficacy in Patients with ARD | |

| Methotrexate |

|

| Mycophenolate mofetil |

|

| Glucocorticoids |

|

| other csDMARDs |

|

| tsDMARDs |

|

| Tumor Necrosis Inhibitors |

|

| Rituximab |

|

| The severity of breakthrough COVID-19 in vaccinated patients with ARD | |

| More severe disease with the use of BCDT or mycophenolate and in the presence of comorbid lung disease | |

| ARD: Autoimmune Rheumatic Disease; BCDT: B-Cell Depleting Therapy; DMARDs: Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs; csDMARDs: conventional synthetic DMARD; tsDMARDs: targeted synthetic DMARD | |

Humoral response after two doses of COVID-19 vaccines was measured using antibody (Ab) level directed toward SARS‐CoV‐2 spike S1 protein (Anti-S) which is also known as the receptor-binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (Anti-RBD Abs), and/or neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) that block the interaction between RBD and ACE2 [26]. However, anti-nucleocapsid Abs were measured in some studies to differentiate prior COVID-19 infection [27]. As illustrated in the supplementary Table 2, reported rates of seroconversion in patients with ARD were in the range of 77–100 % in the absence of B-cell depleting therapy (BCDT) use, although the humoral response in patients with ARD was delayed with a reduced antibody titer [28]. Also, this rate was affected by the type of immunomodulatory medication used as explained in the subsequent section. Moreover, the rate of seroconversion was lower in older age [29], [30], [31], [32] and with certain comorbidities (interstitial lung disease [33] and myositis [34]), and higher in the presence of previous COVID-19 infection [25], [35], [36]. However, it was not affected by the type of underlying type of ARD [25], [29], [37].

SARS-CoV-2 specific cellular response was measured by interferon-γ (IFNγ) production assay, or immune cell phenotyping using high-parameter spectral flow cytometry. Most studies showed significant increases in vaccine-induced cellular immunity (range 69 % to 82 %), but this level was affected by the type of immunomodulatory medication used as explained later. Notably, the level of SARS-CoV-2 specific cellular response correlated with the humoral response [38], except for patients using BCDT.

3.1.2. Effect of immunomodulatory agents on COVID-19 efficacy in patients with ARD

We identified 36 observational studies that investigated the relationship between immunological response to COVID-19 vaccines and the type of immunomodulatory drugs used including conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs), targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs), and biological therapy. The number of included patients in each study ranged from 12 to 686. Around half of the studies (18) had a moderate risk for bias according to the QUIPS tool, while 11 and 7 studies had a low and high risk of bias respectively (supplementary Table 4).

3.1.2.1. Effect of methotrexate on the immunological response to COVID-19 vaccines

Several studies showed reduced humoral and cellular responses to COVID-19 vaccines with methotrexate use (supplementary Table 2). Nevertheless, Cristaudo et al. found no difference in antibody response between patients and controls if the methotrexate dose was held one week after the vaccine dose [35]. On the other hand, at least three observational studies did not find significant differences in COVID-19 vaccine immunogenicity with the use of methotrexate even without drug modification at the time of peri-vaccination [25], [29], [39].

3.1.2.2. Effect of mycophenolate mofetil on the immunological response to COVID-19 vaccines

Mycophenolate mofetil was also found to have a negative impact on the serological response to COVID-19 vaccines in 8 studies (supplementary Table 2), while one study did not show a significant association between the two variables [35]. Of note, Connolly et al. conducted a prospective cohort study on the effect of temporary holding of mycophenolate mofetil one week after vaccination in 24 patients with ARD compared to 171 patients who continued mycophenolate. The authors found statistically and clinically significant differences between both groups in the rate and the level of humoral responses in favour of the group who held mycophenolate mofetil. However, two patients in the latter group had a disease flare that required oral and topical glucocorticoids respectively [39].

3.1.2.3. Effect of glucocorticoids on the immunological response to COVID-19 vaccines

Many studies also found that glucocorticoid use was associated with a lower serological response to COVID-19 vaccines (supplementary Table 2), and one study showed a marginal and statistically nonsignificant negative effect of glucocorticoid use on the cellular response [32]. According to Cook et al. findings, blunted humoral response with glucocorticoid use was dose-dependent (particularly with doses above 10 mg per day) [36]. Nevertheless, Ruddy et al. study showed that although patients receiving steroid-containing regimens had lower seroconversion rates, all patients who were using glucocorticoid monotherapy had positive seroconversion [33].

3.1.2.4. Effect of other csDMARD on the immunological response to COVID-19 vaccines

Santos et al. found lower SARS-CoV-2 Ab titer in response to the COVID-19 vaccine with azathioprine use but not leflunomide [40]. In contrast, Deepak et al. (2021) did not show significant differences in vaccine immunogenicity with the use of azathioprine, leflunomide, teriflunomide, or 6-mercaptopurine [35]. Another interesting study by Simader et al. in a group of patients with ARD who were not receiving BCDT found that using DMARD monotherapy did not affect the rate or titer of seroconversion, whereas using DMARDs combination therapy was negatively associated with both the titer and rate of seroconversion after two doses of the vaccine [41]. Regarding COVID-19-specific cellular immunity, only tacrolimus was associated with impaired T-cell response [31].

3.1.2.5. Effect of tsDMARD on the immunological response to COVID-19 vaccines

Only a few studies addressed the effect of tsDMARDs (JAK inhibitors) on the immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines. Iancovici et al. investigated the immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines in 12 patients with RA treated with JAK inhibitors compared to a control group of 26 healthy individuals, and found that JAK inhibitors use in RA was associated with suppressed humoral response to mRNA vaccine both quantitatively and qualitatively [42]. However, Deepak et al. did not find a significant association between JAK inhibitor use and the immunogenicity of the mRNA vaccine [35].

3.1.2.6. Effect of TNFi on the immunological response to COVID-19 vaccines

Most of the reviewed studies did not show detrimental effects of TNF inhibitors on COVID-19 vaccine humoral immunogenicity (supplementary Table 2). However, Iancovici et al. found reduced antibody titer levels in patients with JIA receiving TNF inhibitors compared to the control group although their plasma-neutralizing activity was preserved [42]. On the other hand, Dimopoulou et al. prospective cohort study on 21 patients with JIA receiving TNF showed a 100 % seroconversion rate with no difference in the humoral response according to the type of TNF inhibitor used [25].

Regarding cellular response, one study by Picchianti-Diamanti et al. found a modest but statistically significant decrease in the level of IFN-γ levels in RA patients receiving TNF inhibitors [27].

3.1.2.7. Effect of rituximab on the immunological response to COVID-19 vaccines

Rituximab use negatively affected the humoral immunological response to COVID-19 vaccines in all twenty-one studies that investigated this relationship with reported seroconversion rates of 10–49 %. Factors associated with lower seroconversion with rituximab use in patients with ARD were older age, low IgM level, low IgG, lack of CD19 reconstitution at the time of vaccination, shorter interval from last rituximab dose, concomitant use of immunosuppressants, and the dose of rituximab given. On the other hand, having a previous COVID-19 infection or receiving a booster vaccine was associated with a higher seroconversion rate in this subset of patients (supplementary Table 2).

Kant et al. examined the effect of booster doses of mRNA vaccine in 15 patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis who were treated with rituximab. All patients had completed their vaccination schedule without any detectable anti-SARS-CoV‐2 spike S1 IgG antibody, and they were all B-cell depleted at the time of completion of the first vaccination series. The third dose of the COVID-19 vaccine yielded a serological response in 46.7 % of the patients (7 out of 15). Most of the patients who were seroconverted had B cell reconstitution at the time of the third dose (5 out of 7). Interestingly, the two patients who had positive seroconversion after the third dose despite being B-cell depleted were vaccinated by different types of COVID-19 vaccines between the first series (adenoviral-vector vaccine Johnson & Johnson) and the subsequent booster doses (Moderna or Pfizer) [43].

Regarding T-cell immunity, many studies showed preserved COVID-19-specific cellular immunity in the setting of rituximab use independent of the humoral immune response ranging between 53 and 71 % (supplementary Table 2). Notably, Krasselt et al. found that patients who did not seroconvert after two doses of the vaccine and were B-cell depleted due to rituximab use had increased T-cell response with a statistically significant p-value (P = 0.0398) [37]. In addition, Jyssum et al. found that the third dose of the COVID-19 vaccine was associated with a positive cellular response in all patients [44].

3.1.2.8. Effect of other biological agents on the immunological response to COVID-19 vaccines

Few studies showed decreased immunological response to COVID-19 vaccines in patients with ARD receiving biological agents other than TNF inhibitors and rituximab. Abatacept was found to be associated with a lower humoral response to COVID-19 vaccines in six studies and a lower cellular response in two studies (supplementary Table 2). Similarly, Picchianti-Diamanti et al. study showed that most patients with RA who were receiving IL-6 inhibitors had humoral and cellular responses to the vaccine although the level of SARS-CoV-2 specific Ab titer and IFN-γ were reduced in this subset of patients [27]. In regards to the IL-1 inhibitors, Valor-Méndez et al. showed that humoral response to mRNA-vaccine occurred in 9 out of 10 patients with ARD who received IL-1 inhibitors with higher titers than the control group, and with similar neutralizing activity [45].

3.1.3. Severity of breakthrough COVID-19 in vaccinated patients with ARD

According to the results from the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) Coronavirus Vaccine (COVAX) physician-reported registry, 0.7 % of fully vaccinated patients had breakthrough COVID-19 infections [46]. Liew et al. described COVID-19 breakthrough infections in 87 fully vaccinated patients with rheumatic diseases who were reported to the Global Rheumatology Alliance registry. The mean time for infection onset after the second dose was 112 (±60) days, and among the 22 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 disease, more than half were receiving BCDT or mycophenolate, and 8 had comorbid lung disease. Five out of the fully vaccinated patients died of whom three were using BCDT and two patients had concomitant lung disease [47].

3.2. Safety of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with ARD

We reviewed 36 observational studies from more than 30 countries on COVID-19 vaccines associated adverse events and ARD disease flare with reassuring safety profiles for both mRNA- and the adenoviral vector AstraZeneca SARS-CoV-2 vaccines (supplementary Table 2). Most of the reviewed studies had moderate risks of bias according to the QUIPS tool (20 studies), while 10 and 6 studies had high and low risks respectively (supplementary Table 4). Precipitation of a new onset ARD was mostly reported through case reports and case series as demonstrated in the supplementary Table 3. The safety profile and possible adverse events of COVID-19 vaccines are summarized in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Summarized study results on the Safety of mRNA and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases.

| Adverse events of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with ARD |

|

| Exacerbation of disease activity in patients with ARD after receiving COVID-19 vaccines |

|

| Precipitation of new-onset ARDs after receiving COVID-19 vaccines in patients with no prior diagnosis of ARD |

|

| ARD: Autoimmune Rheumatic Disease; DMARDs: Disease Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs |

3.2.1. Adverse events of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with ARD

Adverse events of COVID-19 vaccines were reported in nearly all the studies and were mostly self-limiting. The most frequently reported local adverse events were injection-site reactions, while systemic effects included fever, fatigue, headache, myalgia, and arthralgia. Among the 36 studies, only two papers reported serious COVID-19-associated adverse events [46], [48]. The previously mentioned COVAX registry analysis reported an overall adverse events rate of 37 %, of which 0.4 % were categorized as serious events that eventually resolved/recovered [46].

COVID-19 vaccine-associated adverse events occurred more frequently in females, in older age, and in patients with higher disease activity (supplementary Table 2). The types of ARD and immunomodulatory medication used were not related to the incidence of COVID-19 vaccine side effects [49]. Two studies showed that the use of mRNA vaccines was associated with higher rates of side effects compared to other vaccine platforms [49], [50], including a higher rate of thromboembolic events although this difference was not statistically significant [49]. While Lee et al. (2022) showed comparable adverse events between both types [51].

3.2.2. Exacerbation of disease activity in patients with ARD after receiving COVID-19 vaccine

Several studies did not show higher risks of disease flare in the few months post-vaccination. Pinte et al. conducted a prospective cohort study on a total number of 623 patients with ARD (416 vaccinated patients) which showed no difference in the incidence of disease flare among vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals with ARD with a mean follow-up period of 5.9 months [52]. On the other hand, some studies reported an incidence rate of ARD flare in the range of 2.1–15.9 % post vaccination albeit most of the flares were short-lasting. Predictors of disease flare included previous COVID-19 infection, using combination immunomodulatory drugs, having a flare in the past 6 months [53], and discontinuation of treatment [54] (supplementary Table 2).

3.2.3. Precipitation of new-onset ARDs after receiving COVID-19 vaccines in patients with no prior diagnosis of ARD

The temporal association of new-onset ARD with the administration of COVID-19 vaccines was described in a total of 127 patients as case reports and case series (supplementary Table 3). They were reported more frequently with the use of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines in patients aged 50 years or more and occurred 1-day to 4-week post-vaccination.

The most commonly reported incident of ARD following vaccination was PMR (32 cases), followed by undifferentiated oligoarthritis (21 cases), nonspecific polyarthritis (19 cases), leukocytoclastic vasculitis (8 cases), and others (ANCA-associated vasculitis, inflammatory myositis, SLE, RA, GCA, systemic sclerosis, multisystemic inflammatory syndrome, adult-onset Still’s disease, Sjogren’s syndrome, sweet syndrome, and various types of vasculitis (supplementary Table 3).

4. Current international societies’ recommendations on COVID-19 vaccines in patients with ARD

We reviewed seven international societies’ recommendations on COVID-19 vaccination in patients with ARD (supplementary Table 5) plus the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website for the general use of COVID-19 vaccine in immunocompromised patients [55]. All societies recommended prophylactic vaccination against the SARS-CoV-2 virus for patients with ARD irrespective of their disease activity or treatment regimen.

The American College of Rheumatologists (ACR) recommended either type of mRNA vaccine over other vaccine platforms, but other authorities did not prefer one vaccine platform over the other. Notably, the Brazilian Society of Rheumatology recommended using different vaccine platforms for third doses from the initial series, whereas the ACR advised using a booster dose of mRNA vaccines in all patients irrespective of their initial vaccination platform.

Regarding rituximab use, all the reviewed treatment guidelines recommended the administration of COVID-19 vaccine toward the end of the rituximab infusion period around 2–4 weeks before the next dose, or before the commencement of rituximab therapy if possible and in the absence of organ- or life-threatening conditions. The ACR stated that rituximab dosing and timing should either be given according to the CD-19 value or a booster dose to be given 2–4 weeks before the next dose, whereas the British Society for Rheumatology recommended against delaying COVID-19 vaccine in patients who are B-cell depleted (supplementary Table 5).

Regarding other immunosuppressive medications, only the ACR gave a clear recommendation that except for TNF inhibitors and other anti-cytokines; all other csDMARDs, tsDMARDs, subcutaneous abatacept, subcutaneous belimumab, and intravenous cyclophosphamide are to be temporarily held 1–2 weeks post-vaccination if disease activity is stable. On the other hand, other authorities did not recommend routine interruption of immunosuppressive treatment regimens but suggested that treatment modifications should be based on shared decision plans between patients and attending rheumatologists/healthcare providers (supplementary Table 5).

5. Discussion

Our study results indicate that with the exception of patients receiving rituximab or other BCDT, most patients with ARD were able to develop adequate levels of vaccine immunogenicity although at a slower rate than healthy controls. Variables associated with lower humoral response included older age, comorbid interstitial lung disease, and certain immunomodulatory medications such as methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and glucocorticoids (doses above 10 mg daily), abatacept as well as BCDT. However, virus-specific cellular response was less affected by these medications. In terms of the few breakthrough COVID-19 infections in fully vaccinated individuals with ARD, worse outcomes occurred more frequently in patients receiving rituximab/BCDT and those with comorbid interstitial lung disease. Reassuringly, both local and systematic adverse events of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with ARD were self-limited, and most studies did not report a higher incidence of disease flare post-vaccination.

The high level of COVID-19 vaccine immunogenicity in patients with ARD is consistent with other studies as well [56], [57]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Tang et al. showed that patients with ARD achieved seroconversion in 79 % (95 %CI: 67–89 %), and cellular response in 69 % (95 %CI: 55–81 %) after the second dose of mRNA-vaccine [56]. Also, in the subset of patients treated with rituximab who had an absent humoral response, almost half of the patients developed seroconversion after a third dose [43], and in one study, all patients had detectable virus-specific cellular responses irrespective of humoral response [44]. These promising results should encourage rheumatologists to recommend COVID-19 vaccines to patients with ARD and consider a third dose for those who are receiving strong immunosuppressive medications.

According to this review, several immunomodulatory medications other than BCDT were also found to have detrimental effects on COVID-19 vaccine immunogenicity including methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, glucocorticoids, and abatacept. However, the evidence was not consistent in all studies. For example, multiple high-quality studies showed that methotrexate impairs humoral and/or cellular response to the COVID-19 vaccine, while other few studies with a moderate or high risk of bias were not able to confirm this association (supplementary Table 2). In regards to TNF inhibitors and other anti-cytokines such as IL6 inhibitors and IL17 inhibitors, this review did not show a significant impact of these biological agents on the seroconversion rate post-COVID-19 vaccination which is in line with previous studies that demonstrated considerable immunogenicity post influenza and pneumococcal vaccines in patients receiving TNF inhibitors [58], IL6 inhibitor [59] and IL17 inhibitor [60].

Breakthrough symptomatic infection was reported at a very low rate (<1 %) in several large registries in fully vaccinated patients with ARD [61]. Identified risk factors included treatment with certain modalities such as BCDT and mycophenolate, older age as well as the presence of comorbid lung disease. As discussed earlier, these risk factors were also found to be associated with lower vaccine immunogenicity. Additionally, older age (more than 65 years) and multiple comorbidities were associated with higher rates of breakthrough infections in the general population [62]. Reassuringly, breakthrough infections in vaccinated individuals were less severe with a shorter duration of symptoms compared to unvaccinated individuals [63]. These findings support COVID-19 vaccines' effectiveness in the general population and in patients with ARD as no vaccine can prevent infection in all its recipients.

Regarding the risk of post-vaccination disease flare, the reviewed literature showed that the incidence of disease flare post-vaccination was very minimal, and it was similar between groups of patients who were vaccinated and unvaccinated. Similarly, the previously mentioned meta-analysis by Tang et al. found that although post-vaccination arthralgia was more common in patients with ARD, objective disease activity scores such as Disease Activity Score-28 (DAS-28), and Systemic Lupus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) among others did not differ before and after receiving the vaccine. Given the low rate of disease flares among vaccinated patients with ARD, Machado et al. suggested that these observed exacerbations could be explained by the natural disease course rather than by being provoked by COVID-19 vaccination [46].

New-onset ARD post-COVID-19 vaccination has been described more frequently in patients above the age of 50 years and with the use of mRNA vaccines. The novel adjuvanticity of the new COVID-19 vaccines might contribute to the development of a range of inflammatory and autoimmune conditions by triggering autoimmunity [64], [65]. However, vaccines likely work as contributory factors in individuals with predisposing genetic and/or environmental backgrounds to develop the characteristic complex and multifactorial ARDs [91,67]. It is also worth noting that incident ARDs have been increasingly recognized following COVID-19 infection itself [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71]. Nevertheless, it’s difficult to directly compare the incidence of new-onset ARD post-vaccination versus new-onset ARD post-COVID-19 infection.

Vaccine hesitancy is a major obstacle to vaccine utilization in the general population and in patients with ARD. We provided in this study real-world data on the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with ARDs. We also highlighted the small potential risk for post-vaccination disease flare or adverse events, and discussed the timing of vaccine administration in relation to disease activity and medication use in order to optimize COVID-19 vaccine uptake. This information could be used to tailor individualized approaches for COVID-19 vaccination in this unique population of patients.

However, this review has several limitations. First, most of the published papers were on patients receiving mRNA vaccines, and few studies included patients receiving the adenoviral-vector vaccine AstraZeneca. Second, we used the immunological response as the primary outcome of this study as a surrogate marker for vaccine efficacy; however, to date, the level of humoral or cellular response to SARS-CoV-2 virus that conveys protection from symptomatic disease, hospitalisation, or death is not yet well-defined. Third, this review is subjected to the limitations inherent in observational studies including selection bias, response bias, observer bias, and the difficulty in controlling confounding factors which make it difficult to draw causal conclusions. Finally, neither patients’ nor physicians’ perspective on COVID-19 vaccination was explored which might affect vaccine acceptance and utilization, outlining these areas for future research.

6. Conclusion

Both types of mRNA vaccines and the adenoviral vector AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective in patients with ARDs. Booster doses should be routinely recommended for older patients with ARDs, those receiving potent immunosuppressant medications, and patients with comorbid interstitial lung disease. Due to the waning immunity after vaccination and the suboptimal response in some patients with ARDs, further preventive measures such as social distancing and other public health guidelines should be followed. Modifications of immunomodulatory medications must be individualized through a shared decision process taking into consideration patients’ clinical characteristics, types of medications used, and baseline disease activity in line with international professional guidelines. Our findings should assure patients with ARDs that adverse events are rare and self-limiting, and rheumatologists that potential disease flares are adequately manageable with conventional therapies.

Funding

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Anwar I. Joudeh: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Abdu Qaid Lutf: Data curation, Resources, Validation, Visulazation, Writing – review & editing. Salah Mahdi: Data curation, Resources, Validation, Visulazation, Writing – review & editing. Gui Tran: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

This work was completed in partial fulfilment of an MSc in Rheumatology from the University of South Wales. The Open Access Fee was supported by Qatar National Library.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.05.048.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Winchester N., Calabrese C., Calabrese L. The intersection of COVID-19 and autoimmunity: what is our current understanding? Pathogens and Immunity. 2021;6(1):31–54. doi: 10.20411/pai.v6i1.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.García L. Immune Response, Inflammation, and the Clinical Spectrum of COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Middleton's Allergy: Principles and Practice. 9th ed. Elsevier; 2022. ClinicalKey. Available at: https://www.clinicalkey.com/.

- 4.Theofilopoulos A., Kono D., Baccala R. The multiple pathways to autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2017;18(7):716–724. doi: 10.1038/ni.3731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smatti M., Cyprian F., Nasrallah G., Al Thani A., Almishal R., Yassine H. Viruses and autoimmunity: a review on the potential interaction and molecular mechanisms. Viruses. 2019;11(8):762. doi: 10.3390/v11080762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lerner A., Arleevskaya M., Schmiedl A., Matthias T. Microbes and Viruses Are Bugging the Gut in Celiac Disease. Are They Friends or Foes? Front Microbiol. 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williamson E.J., Walker A.J., Bhaskaran K., Bacon S., Bates C., Morton C.E., et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi B., Choudhary M.C., Regan J., Sparks J.A., Padera R.F., Qiu X., et al. Persistence and Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in an Immunocompromised Host. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(23):2291–2293. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2031364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calabrese L., Winthrop K. Rheumatology and COVID-19 at 1 year: facing the unknowns. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(6):679–681. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-219957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.BSR. COVID-19 guidance | British Society for Rheumatology [Internet]. Rheumatology.org.uk. 2022 [cited 5 August 2022]. Available from: https://www.rheumatology.org.uk/practice-quality/covid-19-guidance#:∼:text=It%20is%20safe%20to%20have,receive%20steroids%20in%20any%20form.

- 11.Curtis J., Johnson S., Anthony D., Arasaratnam R., Baden L., Bass A., et al. American College of Rheumatology Guidance for COVID -19 Vaccination in Patients With Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases: Version 4. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2022;74(5) doi: 10.1002/art.42109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furer V., Rondaan C., Agmon-Levin N., van Assen S., Bijl M., Kapetanovic M.C., et al. Point of view on the vaccination against COVID-19 in patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases. RMD Open. 2021;7(1):e001594. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NHS. Coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccine [Internet]. nhs.uk. 2022 [cited 5 August 2022]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/coronavirus-vaccination/coronavirus-vaccine/.

- 14.Sadarangani M., Marchant A., Kollmann T. Immunological mechanisms of vaccine-induced protection against COVID-19 in humans. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(8):475–484. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00578-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fathizadeh H., Afshar S., Masoudi M.R., Gholizadeh P., Asgharzadeh M., Ganbarov K., et al. SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) vaccines structure, mechanisms and effectiveness: a review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;188:740–750. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.08.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dagan N., Barda N., Kepten E., Miron O., Perchik S., Katz M.A., et al. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Mass Vaccination Setting. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(15):1412–1423. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson M., Burgess J., Naleway A., Tyner H., Yoon S., Meece J., et al. Interim Estimates of Vaccine Effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 Vaccines in Preventing SARS-CoV-2 Infection Among Health Care Personnel, First Responders, and Other Essential and Frontline Workers — Eight U.S. Locations, December 2020–March 2021. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2021;70(13):495–500. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7013e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folegatti P.M., Ewer K.J., Aley P.K., Angus B., Becker S., Belij-Rammerstorfer S., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: a preliminary report of a phase 1/2, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020 Aug 15;396(10249):467–478. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31604-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hwang J., Zhang T., Wang A., Li Z. COVID-19 vaccines for patients with cancer: benefits likely outweigh risks. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1) doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01046-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Global manual on surveillance of adverse events following immunization [Internet]. Apps.who.int. 2022 [cited 5 August 2022]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/206144.

- 21.World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard [Internet]. Covid19.who.int. 2022 [cited 5 August 2022]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/.

- 22.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayden J., van der Windt D., Cartwright J., Côté P., Bombardier C. Assessing Bias in Studies of Prognostic Factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):280. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boekel L., Steenhuis M., Hooijberg F., Besten Y.R., van Kempen Z.L.E., Kummer L.Y., et al. Antibody development after COVID-19 vaccination in patients with autoimmune diseases in the Netherlands: a substudy of data from two prospective cohort studies. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3(11):e778–e788. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00222-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dimopoulou D., Vartzelis G., Dasoula F., Tsolia M., Maritsi D. Immunogenicity of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine in adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis on treatment with TNF inhibitors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022 Apr 1;81(4):592–593. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magliulo D., Wade S.D., Kyttaris V.C. Immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in rituximab-treated patients: effect of timing and immunologic parameters. Clin Immunol. 2022 Jan;1(234) doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2021.108897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Picchianti-Diamanti A., Aiello A., Laganà B., Agrati C., Castilletti C., Meschi S., et al. Immunosuppressive Therapies Differently Modulate Humoral- and T-Cell-Specific Responses to COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.740249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon D., Tascilar K., Fagni F., Krönke G., Kleyer A., Meder C., et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination responses in untreated, conventionally treated and anticytokine-treated patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(10):1312–1316. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braun-Moscovici Y., Kaplan M., Braun M., Markovits D., Giryes S., Toledano K., et al. Disease activity and humoral response in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases after two doses of the Pfizer mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(10):1317–1321. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Furer V., Eviatar T., Zisman D., Peleg H., Paran D., Levartovsky D., et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases and in the general population: a multicentre study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(10):1330–1338. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prendecki M., Clarke C., Edwards H., McIntyre S., Mortimer P., Gleeson S., et al. Humoral and T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients receiving immunosuppression. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(10):1322–1329. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saleem B., Ross R.L., Bissell L.-A., Aslam A., Mankia K., Duquenne L., et al. Effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) on DMARDs: as determined by antibody and T cell responses. RMD Open. 2022;8(1) doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2021-002050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruddy J.A., Connolly C.M., Boyarsky B.J., Werbel W.A., Christopher-Stine L., Garonzik-Wang J., et al. High antibody response to two-dose SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA vaccination in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(10):1351–1352. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Visentini M., Gragnani L., Santini S.A., Urraro T., Villa A., Monti M., et al. Flares of mixed cryoglobulinaemia vasculitis after vaccination against SARS-CoV-2. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(3):441–443. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deepak P., Kim W., Paley M.A., Yang M., Carvidi A.B., Demissie E.G., et al. Effect of immunosuppression on the immunogenicity of mRNA vaccines to SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(11):1572–1585. doi: 10.7326/M21-1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cook C., Patel N.J., D’Silva K.M., Hsu T.-T., DiIorio M., Prisco L., et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 breakthrough infections among vaccinated patients with systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(2):289–291. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krasselt M, Wagner U, Nguyen P, Pietsch C, Boldt A, Baerwald C, et al. Humoral and cellular response to COVID-19 vaccination in patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases under real-life conditions. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2022 Feb 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Schreiber K., Graversgaard C., Petersen R., Jakobsen H., Bojesen A.B., Krogh N.S., et al. Reduced Humoral Response of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies following Vaccination in Patients with Inflammatory Rheumatic Diseases—An Interim Report from a Danish Prospective Cohort Study. Vaccines. 2021 Dec 28;10(1):35. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10010035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Connolly C.M., Chiang T.-Y., Boyarsky B.J., Ruddy J.A., Teles M., Alejo J.L., et al. Temporary hold of mycophenolate augments humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases: a case series. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(2):293–295. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sieiro Santos C., Calleja Antolin S., Moriano Morales C., Garcia Herrero J., Diez Alvarez E., Ramos Ortega F., et al. Immune responses to mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory rheumatic diseases. RMD Open. 2022;8(1) doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simader E., Tobudic S., Mandl P., Haslacher H., Perkmann T., Nothnagl T., et al. Importance of the second SARS-CoV-2 vaccination dose for achieving serological response in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and seronegative spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(3):416–421. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iancovici L, Khateeb D, Harel O, Peri R, Slobodin G, Hazan Y, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with Janus kinase inhibitors show reduced humoral immune responses following BNT162b2 vaccination. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2021 Nov 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Kant S., Azar A., Geetha D. Antibody response to COVID-19 booster vaccine in rituximab-treated patients with anti–neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis. Kidney Int. 2022 Feb 1;101(2):414–415. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jyssum I., Kared H., Tran T.T., Tveter A.T., Provan S.A., Sexton J., et al. Humoral and cellular immune responses to two and three doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in rituximab-treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective, cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2022;4(3):e177–e187. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00394-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valor-Méndez L., Tascilar K., Simon D., Distler J., Kleyer A., Schett G., et al. Correspondence on ‘Immunogenicity and safety of anti-SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines in patients with chronic inflammatory conditions and immunosuppressive therapy in a monocentric cohort’. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(10) doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Machado P.M., Lawson-Tovey S., Strangfeld A., Mateus E.F., Hyrich K.L., Gossec L., et al. Safety of vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 in people with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases: results from the EULAR Coronavirus Vaccine (COVAX) physician-reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(5):695–709. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liew J., Gianfrancesco M., Harrison C., Izadi Z., Rush S., Lawson-Tovey S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections among vaccinated individuals with rheumatic disease: results from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance provider registry. RMD Open. 2022;8(1) doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2021-002187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bartels L.E., Ammitzbøll C., Andersen J.B., Vils S.R., Mistegaard C.E., Johannsen A.D., et al. Local and systemic reactogenicity of COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b2 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41(11):1925–1931. doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-04972-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Y.K., Lui M.P., Yam L.L., Cheng C.S., Tsang T.H., Kwok W.S., et al. COVID-19 vaccination in patients with rheumatic diseases: vaccination rates, patient perspectives, and side effects. Immun Inflammation Dis. 2022 Mar;10(3) doi: 10.1002/iid3.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ozdede A., Guner S., Ozcifci G., Yurttas B., Toker Dincer Z., Atli Z., et al. Safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with Behcet’s syndrome and familial Mediterranean fever: a cross-sectional comparative study on the effects of M-RNA based and inactivated vaccine. Rheumatol Int. 2022;42(6):973–987. doi: 10.1007/s00296-022-05119-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee T.J., Lu C.H., Hsieh S.C. Herpes zoster reactivation after mRNA-1273 vaccination in patients with rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022 Apr 1;81(4):595–597. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pinte L., Negoi F., Ionescu G.D., Caraiola S., Balaban D.V., Badea C., et al. COVID-19 vaccine does not increase the risk of disease flare-ups among patients with autoimmune and immune-mediated diseases. J Personalized Med. 2021 Dec 2;11(12):1283. doi: 10.3390/jpm11121283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Connolly C.M., Ruddy J.A., Boyarsky B.J., Barbur I., Werbel W.A., Geetha D., et al. Disease Flare and Reactogenicity in Patients With Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases Following Two-Dose SARS–CoV-2 Messenger RNA Vaccination. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2022 Jan;74(1):28–32. doi: 10.1002/art.41924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fragoulis G.E., Bournia V.-K., Mavrea E., Evangelatos G., Fragiadaki K., Karamanakos A., et al. COVID-19 vaccine safety and nocebo-prone associated hesitancy in patients with systemic rheumatic diseases: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatol Int. 2022;42(1):31–39. doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-05039-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of COVID-19 Vaccines Currently Approved or Authorized in the United States [Internet]. CDC. 2022 [cited 15 August 2022]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/covid-19-vaccines-us.html.

- 56.Tang K.T., Hsu B.C., Chen D.Y. Immunogenicity, effectiveness, and safety of covid-19 vaccines in rheumatic patients: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomedicines. 2022 Apr 1;10(4):834. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10040834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alsaed O., Emadi S.A., Satti E., Muthanna B., Veettil S.F., Ashour H., et al. Humoral Response of Patients With Autoimmune Rheumatic Disease to BNT162b2 Vaccine: a Retrospective Comparative Study. Cureus. 2022 Apr 29;14(4) doi: 10.7759/cureus.24585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hua C., Barnetche T., Combe B., Morel J. Effect of methotrexate, anti–tumor necrosis factor α, and rituximab on the immune response to influenza and pneumococcal vaccines in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2014 Jul;66(7):1016–1026. doi: 10.1002/acr.22246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mori S., Ueki Y., Hirakata N., Oribe M., Hidaka T., Oishi K. Impact of tocilizumab therapy on antibody response to influenza vaccine in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Dec 1;71(12):2006–2010. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Richi P., Martín M.D., de Ory F., Gutiérrez-Larraya R., Casas I., Jiménez-Díaz A.M., et al. Secukinumab does not impair the immunogenic response to the influenza vaccine in patients. RMD Open. 2019;5(2) doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2019-001018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lawson-Tovey S., Hyrich K.L., Gossec L., Strangfeld A., Carmona L., Raffeiner B., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination in patients with inflammatory rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(1):145–150. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yek C., Warner S., Wiltz J.L., Sun J., Adjei S., Mancera A., et al. Risk factors for severe COVID-19 outcomes among persons aged≥ 18 years who completed a primary COVID-19 vaccination series—465 health care facilities, United States, December 2020–October 2021. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(1):19–25. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7101a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Antonelli M., Penfold R.S., Merino J., Sudre C.H., Molteni E., Berry S., et al. Risk factors and disease profile of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK users of the COVID Symptom Study app: a prospective, community-based, nested, case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):43–55. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00460-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Teijaro J.R., Farber D.L. COVID-19 vaccines: modes of immune activation and future challenges. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021 Apr;21(4):195–197. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00526-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.De Marco G., Giryes S., Williams K., Alcorn N., Slade M., Fitton J., et al. A Large Cluster of New Onset Autoimmune Myositis in the Yorkshire Region Following SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination. Vaccines. 2022 Aug;10(8):1184. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10081184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bellavite P. Causality assessment of adverse events following immunization: the problem of multifactorial pathology. F1000Research. 2020;9:170. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.22600.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baimukhamedov C., Barskova T., Matucci-Cerinic M. Arthritis after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021 May 1;3(5):e324–e325. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00067-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fineschi S. Case report: systemic sclerosis after Covid-19 infection. Front Immunol. 2021 Jun;28(12):2439. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.686699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moeinzadeh F., Dezfouli M., Naimi A., Shahidi S., Moradi H. Newly diagnosed glomerulonephritis during COVID-19 infection undergoing immunosuppression therapy, a case report. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2020 May 1;14(3):239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Uppal N.N., Kello N., Shah H.H., Khanin Y., De Oleo I.R., Epstein E., et al. De novo ANCA-associated vasculitis with glomerulonephritis in COVID-19. Kidney Int Rep. 2020 Nov;5(11):2079. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hsu T.Y., D'Silva K.M., Patel N.J., Fu X., Wallace Z.S., Sparks J.A. Incident systemic rheumatic disease following COVID-19. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021 Jun 1;3(6):e402–e404. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00106-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.