Key Points

Question

Can a patient-specific, clinician-facing communication-priming intervention (Jumpstart Guide) with discussion prompts effectively promote goals-of-care discussions between clinicians and hospitalized older patients with serious illness?

Findings

In this pragmatic, randomized clinical trial of 2512 hospitalized patients, the clinician-facing intervention resulted in a significant increase in the proportion of patients with documented goals-of-care discussions within 30 days (34.5% of patients in the intervention group vs 30.4% in the usual care group). The effect of the intervention was greater among racially or ethnically minoritized patients.

Meaning

These findings suggest that clinician-facing prompting interventions promote goals-of-care discussions, particularly among racially or ethnically minoritized patients.

Abstract

Importance

Discussions about goals of care are important for high-quality palliative care yet are often lacking for hospitalized older patients with serious illness.

Objective

To evaluate a communication-priming intervention to promote goals-of-care discussions between clinicians and hospitalized older patients with serious illness.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A pragmatic, randomized clinical trial of a clinician-facing communication-priming intervention vs usual care was conducted at 3 US hospitals within 1 health care system, including a university, county, and community hospital. Eligible hospitalized patients were aged 55 years or older with any of the chronic illnesses used by the Dartmouth Atlas project to study end-of-life care or were aged 80 years or older. Patients with documented goals-of-care discussions or a palliative care consultation between hospital admission and eligibility screening were excluded. Randomization occurred between April 2020 and March 2021 and was stratified by study site and history of dementia.

Intervention

Physicians and advance practice clinicians who were treating the patients randomized to the intervention received a 1-page, patient-specific intervention (Jumpstart Guide) to prompt and guide goals-of-care discussions.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients with electronic health record–documented goals-of-care discussions within 30 days. There was also an evaluation of whether the effect of the intervention varied by age, sex, history of dementia, minoritized race or ethnicity, or study site.

Results

Of 3918 patients screened, 2512 were enrolled (mean age, 71.7 [SD, 10.8] years and 42% were women) and randomized (1255 to the intervention group and 1257 to the usual care group). The patients were American Indian or Alaska Native (1.8%), Asian (12%), Black (13%), Hispanic (6%), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (0.5%), non-Hispanic (93%), and White (70%). The proportion of patients with electronic health record–documented goals-of-care discussions within 30 days was 34.5% (433 of 1255 patients) in the intervention group vs 30.4% (382 of 1257 patients) in the usual care group (hospital- and dementia-adjusted difference, 4.1% [95% CI, 0.4% to 7.8%]). The analyses of the treatment effect modifiers suggested that the intervention had a larger effect size among patients with minoritized race or ethnicity. Among 803 patients with minoritized race or ethnicity, the hospital- and dementia-adjusted proportion with goals-of-care discussions was 10.2% (95% CI, 4.0% to 16.5%) higher in the intervention group than in the usual care group. Among 1641 non-Hispanic White patients, the adjusted proportion with goals-of-care discussions was 1.6% (95% CI, −3.0% to 6.2%) higher in the intervention group than in the usual care group. There was no evidence of differential treatment effects of the intervention on the primary outcome by age, sex, history of dementia, or study site.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among hospitalized older adults with serious illness, a pragmatic clinician-facing communication-priming intervention significantly improved documentation of goals-of-care discussions in the electronic health record, with a greater effect size in racially or ethnically minoritized patients.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04281784

This randomized clinical trial compares the effect of a communication-priming intervention vs usual care on patient-physician discussions on goals of care for hospitalized older patients with serious illness.

Introduction

Communication about goals of care for patients with serious illness has been associated with improved patient and family outcomes as well as reduced intensity of care at the end of life.1,2 However, conducting and documenting high-quality goals-of-care discussions with seriously ill patients remains a shortcoming in many health systems.2,3,4,5,6,7 Electronic health records (EHRs) provide an opportunity to identify patients who might benefit from goals-of-care discussions and to promote these discussions, yet prior interventions have not used EHRs to accomplish these objectives.8,9

Previous randomized clinical trials (RCTs)7,10 have examined a bidirectional intervention (Jumpstart Guide) delivered to both patients and clinicians to promote goals-of-care discussions. The bidirectional intervention used patient surveys to populate 1-page guides summarizing patient-specific communication and care preferences as well as communication prompts including example language.7,10 In an RCT of outpatients with serious illness, this intervention increased the incidence of goals-of-care discussions at the targeted clinic visit from 31% to 74% (P < .001), and increased patient-assessed quality of communication.7 A subsequent pilot RCT of hospitalized patients with serious illness also showed that this bidirectional intervention increased the incidence of documented goals-of-care discussions from 8% to 21% (P = .04) during the hospitalization.11

However, surveying patients or family members for preferences prior to the intervention made the bidirectional intervention challenging to implement because of the resources required.12 In addition, these 2 trials7,11 involved manual EHR review to assess documentation of goals-of-care discussions that is time intensive. These limitations highlight the need to evaluate the effectiveness of a more scalable implementation of the intervention as well as more efficient methods to measure documented goals-of-care discussions for patients with serious illness.12,13

This large pragmatic RCT tested whether a clinician-facing communication-priming intervention (Jumpstart Guide) containing patient-specific EHR data and communication prompts increased documented goals-of-care discussions for hospitalized older patients with serious illness compared with usual care. The differential effects of the intervention were examined by age, sex, history of dementia, minoritized race or ethnicity, and study site.

Methods

Overview

This was a pragmatic, parallel, 1:1 RCT of an intervention (Jumpstart Guide) vs usual care. A waiver of informed consent was granted by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division, and all eligible patients were randomized. The waiver of informed consent was approved based on the rationale that the intervention was designed to promote standard of care. The trial protocol was published14 and appears in Supplement 1. A data and safety monitoring committee acted in an advisory capacity, evaluating the progress of the study, monitoring participant safety, and reviewing procedures for maintaining the confidentiality of the data and the quality of data collection, management, and analysis.

Setting

The trial was conducted at 3 hospitals at UW Medicine, the health system affiliated with the University of Washington (2 teaching hospitals, including a university hospital and a safety-net county hospital, and a community hospital). The university hospital is an academic medical center that provides subspecialty care to the region; it has 529 acute care beds and 86 intensive care unit (ICU) beds. The county hospital is a university-operated tertiary care hospital and regional referral center and is the only level 1 trauma center serving a 5-state region; it has 413 acute care beds and 89 ICU beds. The community hospital is academically affiliated and serves a large geriatric and nursing home resident population; it has 218 acute care beds and 15 ICU beds.

Patient Population

Eligible patients had been hospitalized, were aged 55 years or older, and were identified using International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes documented in the EHR during the 2 years prior to the hospitalization that indicated presence of 1 or more of the 9 chronic conditions used by the Dartmouth Atlas15,16,17 to study end-of-life care: dementia, cancers of poor prognosis, chronic pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, heart failure, chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes with end-organ damage, and peripheral vascular disease. These 9 conditions account for 90% of deaths among Medicare beneficiaries in the US.16 In addition, all hospitalized patients aged 80 years or older were also included to increase inclusivity of important and understudied populations at high risk of hospital morbidity and mortality.18,19

To be eligible for randomization, patients had to be in the hospital for at least 12 hours but not longer than 96 hours. Among patients meeting eligibility criteria, those without documentation of goals-of-care discussions or palliative care consultations during the current hospital admission (determined through manual daily screening of hospitalized patients) were enrolled and simultaneously randomized.12,20,21,22,23,24 Patients were considered ineligible if they had received a transplant within the prior year, were currently receiving hospice or comfort care, had been admitted for a suicide attempt or psychiatric diagnosis, or had hospital records designated as no-information status (eg, patients under law enforcement custody or victims of violence). Clinicians were allowed to opt out of the study or ask that an individual patient not be included (see exclusions in Figure 1).

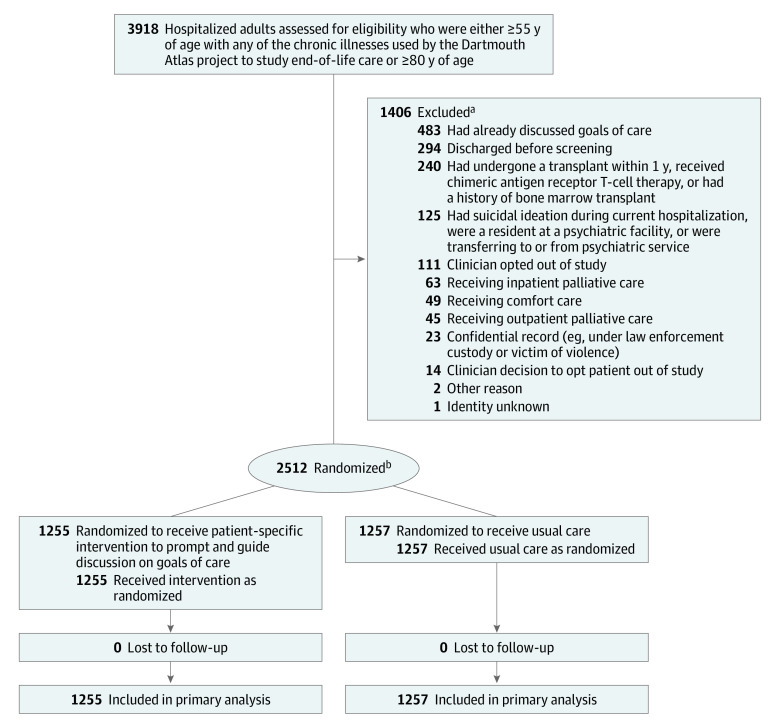

Figure 1. Eligibility Assessment, Randomization, and Flow of Patients Through a Trial of a Communication-Priming Intervention to Promote Goals-of-Care Discussions.

aSome patients were ineligible for more than 1 reason.

bStratified by study site and history of dementia.

Sample Size Calculations

With a target sample size of 2000 (1000 per group) and 2-sided significance level of .05, the estimated power was 80% to detect a difference of at least 6% in the proportion of patients with documented goals-of-care discussions between those randomized to the intervention vs usual care. In the sample size calculation, normal approximation to the binomial was used and an average proportion of 0.54 with goals-of-care discussions was assumed based on the proportion among all participants in a prior trial of the intervention.

Randomization

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio using variable block sizes ranging from 2 to 6, and stratified for dementia based on ICD-10 codes and study site using Access version 16.0 (Microsoft). Randomization occurred between April 2020 and March 2021. Enrollment was extended beyond the target sample size of 2000 to increase the number of patients with a history of dementia and was concluded immediately prior to a change in the EHR vendor at the study sites in an effort to avoid the anticipated stress associated with such a change. Randomization occurred within the first 5 days of hospitalization.

Intervention

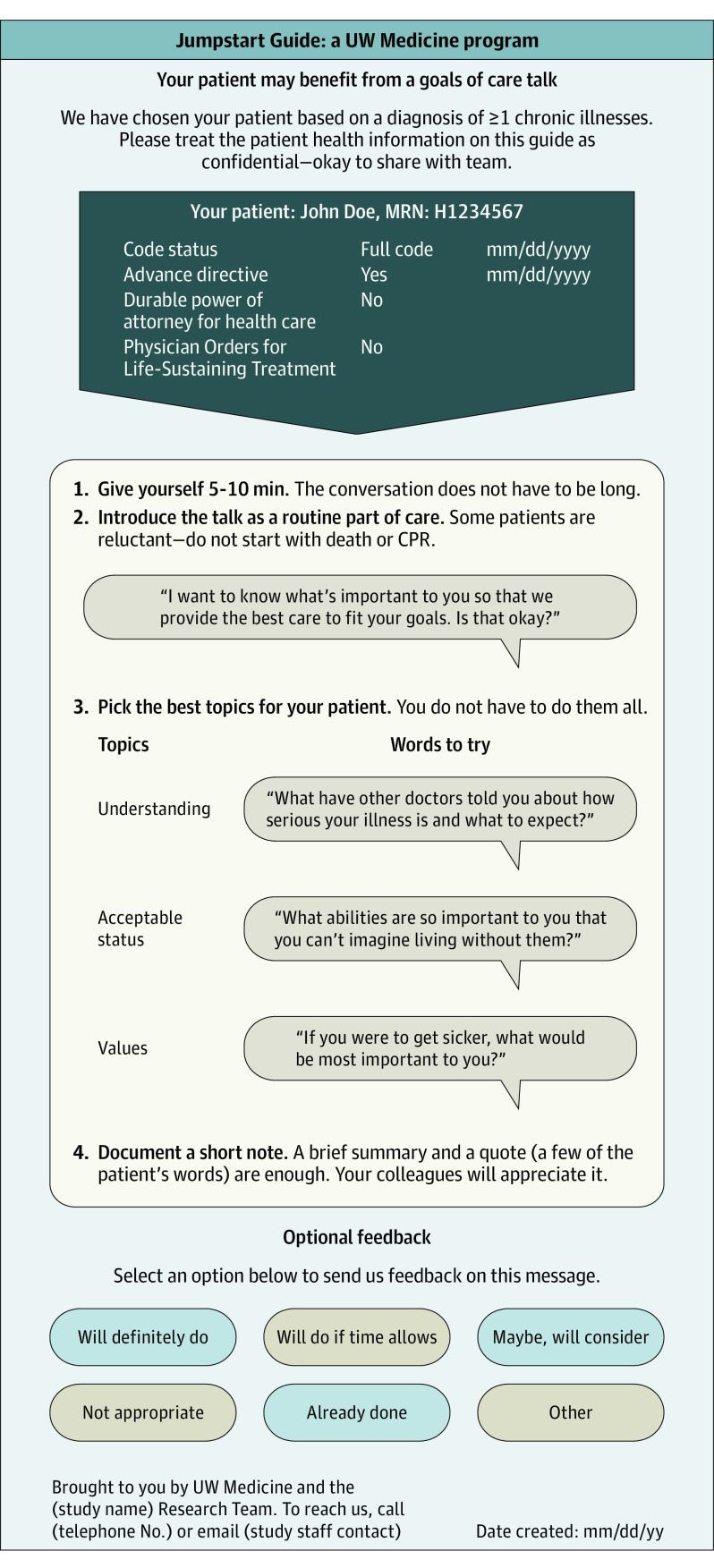

Automated methods were used to examine structured data elements in the EHR prior to randomization, identifying current code status as well as prior Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment and advance directives; this information was included on the 1-page intervention (Figure 2) to inform goals-of-care discussions along with example language for conducting such discussions. The intervention was delivered to the primary hospital team (the attending physician as well as all resident physicians and advanced practice clinicians on the care team) via secure email. The email containing the intervention was only sent once. Clinicians also received 1 pager message to alert them to the presence of the intervention in their email box. The intervention was delivered on the day of patient randomization.

Figure 2. Example of Intervention.

The intervention was emailed to clinicians on the day of patient randomization and a message was sent to clinicians via their pagers to alert them to the presence of the intervention in their email box. CPR indicates cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Outcomes and Covariates

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients with EHR-documented goals-of-care discussions within 30 days of randomization. Documented goals-of-care discussions were identified by natural language processing (NLP)–screened human abstraction25 and this process is separately described.13 Goals-of-care discussions were defined as those that were about a patient’s overarching goals for medical care.26 Discussions solely focused on code status were not considered to be goals-of-care discussions.

To measure the primary outcome, a deep-learning NLP model was trained to screen EHR text for passages likely to contain documented goals-of-care discussions. Passages that screened positive by the NLP model were then reviewed by research coordinators to determine the presence or absence of documented goals-of-care discussions. The screening threshold was set to achieve a patient-level sensitivity of 92.6% for NLP-screened human abstraction in a 159-patient internal validation sample; this discrimination threshold corresponded with a patient-level sensitivity of 99.2% and specificity of 33.2% for the NLP model functioning as a standalone classifier within the same validation sample.13 Randomization was concealed from abstractors, and instances of disagreement were resolved by consensus.

The prespecified secondary outcomes obtained from the EHR were the metrics associated with intensity of care (any ICU admissions, any emergency department [ED] visits, any palliative care consultations, and ICU- and hospital-free days) assessed at 30 days after randomization; hospital readmission within 7 days after hospital discharge; and death within 30 days after randomization.

Race, ethnicity, and sex were collected from the EHR. Minoritized race or ethnicity was defined as race and ethnicity other than non-Hispanic White (ie, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander). To identify patients with a history of dementia not captured by the ICD-10 codes at randomization, research coordinators also performed a manual adjudication of EHR notes for dementia diagnoses.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses included (1) descriptive analyses of the patient characteristics within the 2 randomization groups, (2) evaluation of the treatment effect of the intervention on the primary outcome, (3) evaluation of the treatment effect of the intervention on the secondary outcomes, (4) evaluation of modifiers of the treatment effect on the primary outcome, and (5) a sensitivity analysis. The intention-to-treat principle was followed for the primary analysis.

The effect of the intervention on the primary outcome was quantified by the between-group difference in proportions and evaluated with a linear regression model with robust SEs. The primary analysis was adjusted for study site and history of dementia as defined by ICD-10 code because randomization was stratified on these factors. For the primary outcome, whether the effect of the intervention varied by age, sex, history of dementia, minoritized race or ethnicity, or study site was also evaluated. Differences in the effect of the intervention among individual races and ethnicities were also explored.

A sensitivity analysis evaluated the differences in the effect of the intervention by history of dementia as determined by the 2 methods used (footnotes c and d in Table 1) to identify dementia. The effect of the intervention on the secondary outcomes was quantified by the risk difference in proportions or means using regression models similar to those used for the primary outcome.

Table 1. Demographics and Baseline Characteristics in a Trial of a Communication Guide.

| Characteristic | Intervention (n = 1255) | Usual care (n = 1257) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 70 (63-80) | 70 (62-80) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Female | 543 (43.3) | 513 (40.8) |

| Male | 712 (56.7) | 744 (59.2) |

| Race and ethnicity, No./total (%)a | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 21/1218 (1.7) | 24/1216 (2.0) |

| Asian | 143/1218 (11.7) | 149/1216 (12.3) |

| Black | 168/1218 (13.8) | 148/1216 (12.2) |

| Hispanic | 77/1248 (6.2) | 73/1249 (5.8) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 4/1218 (0.3) | 9/1216 (0.7) |

| Non-Hispanic | 1171/1248 (93.8) | 1176/1249 (94.2) |

| White | 882/1218 (72.4) | 886/1216 (72.9) |

| Minoritized race or ethnicity, No./total (%)b | 409/1224 (33.4) | 394/1220 (32.3) |

| Marital status, No./total (%) | ||

| Married | 502/1238 (40.5) | 515/1242 (41.5) |

| Single | 346/1238 (27.9) | 349/1242 (28.1) |

| Widowed | 199/1238 (16.1) | 187/1242 (15.1) |

| Divorced or separated | 191/1238 (15.4) | 191/1242 (15.4) |

| Limited spoken English proficiency, No. (%) | ||

| No | 1061 (84.5) | 1078 (85.8) |

| Yes (prefer another spoken language) | 186 (14.8) | 171 (13.6) |

| Use American Sign Language or need interpreter or interpreter services | 3 (0.3) | 0 |

| Preferred language not documented | 5 (0.4) | 8 (0.6) |

| Chronic illness (categories are not mutually exclusive), No. (%)c | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 424 (33.8) | 442 (35.2) |

| Heart failure | 356 (28.4) | 342 (27.2) |

| Lung disease | 339 (27.0) | 341 (27.1) |

| Kidney failure | 301 (24.0) | 326 (25.9) |

| Cancer | 300 (23.9) | 296 (23.5) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 269 (21.4) | 269 (21.4) |

| Diabetes | 190 (15.1) | 196 (15.6) |

| Dementia | ||

| History of dementia at randomizationd | 140 (11.2) | 140 (11.1) |

| Expanded definition for history of dementiae | 172 (13.7) | 183 (14.6) |

| Liver disease | 163 (13.0) | 152 (12.1) |

| Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR)f | 4 (2-6) | 4 (3-6) |

| Advance directive in EHR prior to admission, No. (%) | 97 (7.7) | 134 (10.7) |

| Designated power of attorney prior to enrollment, No. (%) | 154 (12.3) | 167 (13.3) |

| POLST prior to enrollment, No. (%) | 94 (7.5) | 90 (7.2) |

| Study site, No. (%) | ||

| County hospital | 485 (38.6) | 487 (38.7) |

| Community hospital | 328 (26.1) | 327 (26.0) |

| University hospital | 442 (35.2) | 443 (35.2) |

Abbreviations: EHR, electronic health record; POLST, Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment.

Determined from EHR patient registration data using fixed categories.

Patients were considered minoritized if they had known minority race or known minority ethnicity. The denominators of 1224 (intervention) and 1220 (usual care) reflect the sum of (1) patients with known race and known ethnicity, (2) patients with known non-White race and unknown ethnicity, and (3) patients with known Hispanic ethnicity and unknown race.

Determined through EHR extraction of International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), diagnosis codes relevant to each chronic illness for the 2 years prior to the patient’s hospital admission.

Based on ICD-10 diagnosis codes in the EHR recorded at any time within the 2 years prior to the patient’s hospital admission or from an EHR indication of history of dementia by manual screening.

Based on additional manual abstraction of EHR records after randomization.

Based on the sum of weighted scores assigned to 17 comorbidities (range, 0-26) identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes and ICD-10 codes. Higher scores are prognostic of higher mortality.

The analyses were completed using SPSS version 27 (IBM) and Stata IC version 16.1 (StataCorp).

Results

Of 3918 patients screened, 2512 were enrolled and randomized (1255 in the intervention group and 1257 in the usual care group; Figure 1). The mean age was 71.7 years (SD, 10.8 years) and there were 1056 women (42%). The patients were American Indian or Alaska Native (1.8%), Asian (12%), Black (13%), Hispanic (6%), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (0.5%), non-Hispanic (93%), White (70%); race was unknown for 3% and ethnicity was unknown for 1%. Of 2444 patients with known race and ethnicity, known non-White race, or known Hispanic ethnicity, there were 803 (33%) with minoritized race or ethnicity. There were 280 patients with dementia identified by ICD-10 codes (known at the time of randomization) and an additional 75 identified after randomization by manual EHR review. Patient characteristics were similar between treatment groups (Table 1).

Primary Outcome

The proportion of patients with EHR-documented goals-of-care discussions within 30 days of randomization was 34.5% (433 of 1255 patients) in the intervention group and 30.4% (382 of 1257 patients) in the usual care group (hospital- and dementia-adjusted difference, 4.1% [95% CI, 0.4%-7.8%], P = .03; Table 2).

Table 2. Effect of Clinician-Facing Intervention on Primary and Secondary Outcomes.

| Intervention (n = 1255) | Usual care (n = 1257) | Adjusted difference, % (95% CI)a | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||||

| EHR-documented goals-of-care discussions within 30 d, No. (%) | 433 (34.5) | 382 (30.4) | 4.1 (0.4 to 7.8) | .03 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Required ICU care within 30 d after randomization, No. (%) | 343 (27.3) | 356 (28.3) | −1.0 (−4.4 to 2.5) | .58 |

| Required ED care within 30 d after randomization, No. (%) | 217 (17.3) | 234 (18.6) | −1.3 (−4.3 to 1.7) | .39 |

| Hospital readmission within 7 d after hospital discharge, No. (%) | 81 (6.5) | 90 (7.2) | −0.7 (−2.7 to 1.3) | .48 |

| Death within 30 d after randomization, No. (%) | 70 (5.6) | 64 (5.1) | 0.5 (−1.3 to 2.2) | .59 |

| Palliative care consultation within 30 d after randomization, No. (%) | 63 (5.0) | 62 (4.9) | 0.001 (−1.6 to 1.8) | .91 |

| Time spent out of ICU and alive within 30 d after randomization, mean (SD), d | 27.8 (6.2) | 27.9 (6.1) | −0.08 (−0.6 to 0.4)b | .75 |

| Time spent out of hospital and alive within 30 d after randomization, mean (SD), d | 21.6 (9.1) | 22.0 (8.7) | −0.4 (−1.1 to 0.3)b | .31 |

| Time spent in hospital after randomization, mean (SD), d | 8.4 (11.9) | 8.1 (12.1) | 0.3 (−0.6 to 1.3)b | .48 |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; EHR, electronic health record; ICU, intensive care unit.

Adjusted differences are expressed as differences in percentages or means, as appropriate, from linear regression models with robust SEs adjusted for history of dementia (as measured at randomization) and study site.

Data are expressed as adjusted difference in means (95% CI).

Secondary Outcomes

There were no significant between-group differences for the secondary outcomes (Table 2). In the intervention group, 27.3% were admitted to an ICU within 30 days after randomization compared with 28.3% in the usual care group (risk difference, −1.0% [95% CI −4.4% to 2.5%]). In the intervention group, 17.3% required ED care within 30 days after randomization compared with 18.6% in the usual care group (risk difference, −1.3% [95% CI, −4.3% to 1.7%]).

In each group, the mean time spent out of the hospital and alive within 30 days after randomization was about 22 days. In each group, the mean time spent out of the ICU and alive within 30 days after randomization was about 28 days. In each group, the mean duration of time spent in the hospital after randomization was about 8 days. The vast majority of patients were discharged within 30 days (95.5% in the intervention group vs 96.1% in the usual care group). Death within 30 days after randomization occurred in 5.6% of the intervention group and 5.1% of the usual care group (risk difference, 0.5% [95% CI, −1.3% to 2.2%]).

Modifiers of Treatment Effect on the Primary Outcome

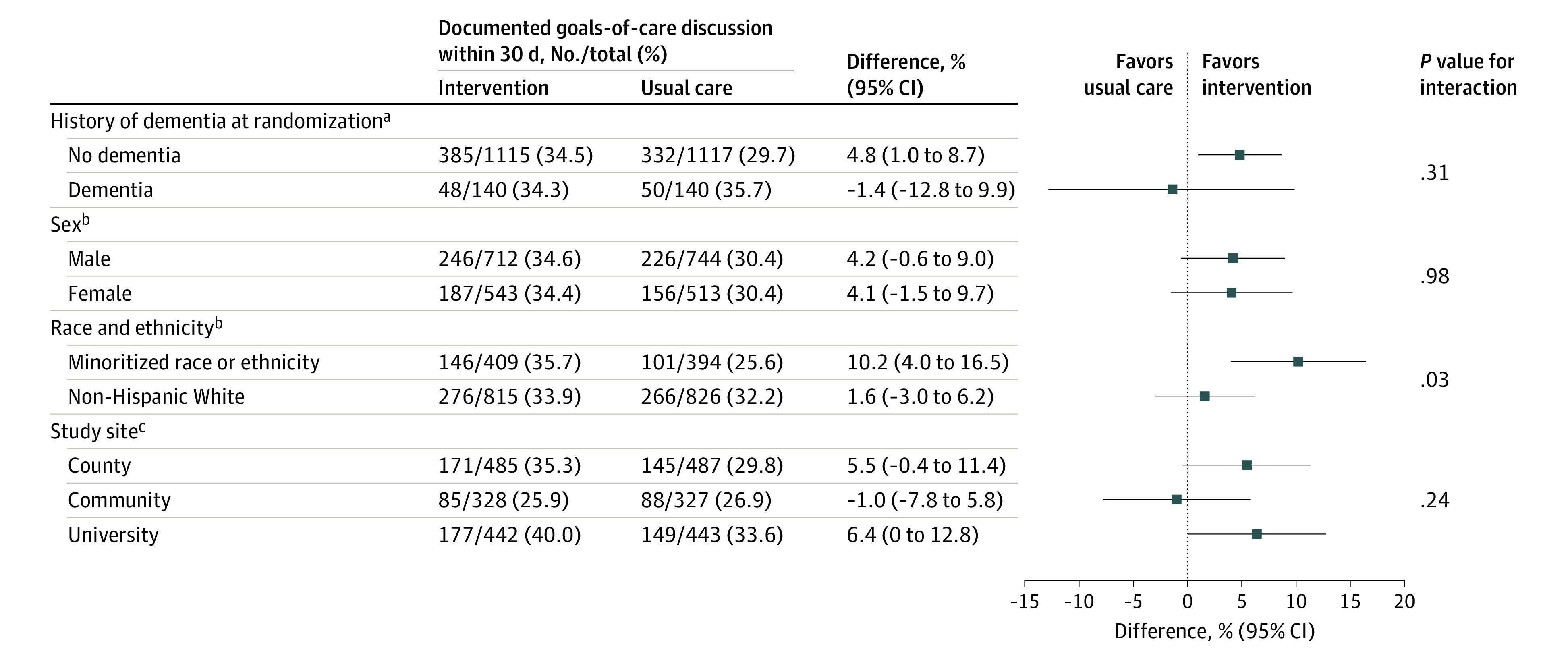

Among 803 patients with minoritized race or ethnicity, the hospital- and dementia-adjusted proportion with goals-of-care discussions was 10.2% (95% CI, 4.0% to 16.5%) higher in the intervention group than in the usual care group. Among 1641 non-Hispanic White patients, the adjusted proportion with goals-of-care discussions was 1.6% (95% CI, −3.0% to 6.2%) higher in the intervention group than in the usual care group (Figure 3). There was a statistically significant interaction between the effect of the intervention and minoritized race or ethnicity, with a greater effect seen among patients with minoritized race or ethnicity (P = .03). The analyses by individual races and ethnicities were generally consistent with these findings, although they were limited by the sample sizes (eTable in Supplement 2). There was no evidence of differential treatment effects of the intervention by sex, history of dementia, or study site as defined by the test for an interaction effect (Figure 3). There was also no evidence of differential treatment effects of the intervention by patient age.

Figure 3. Comparison of Subgroups With Regard to Associations Between the Intervention Effect and the Occurrence of Discussions on Goals of Care.

aThe difference (95% CI) was adjusted for study site.

bThe difference (95% CI) was adjusted for study site and history of dementia at randomization.

cThe difference (95% CI) was adjusted for history of dementia at randomization.

Sensitivity Analysis

In the sensitivity analysis in which dementia was defined by manual abstraction, the results were similar to the results of the primary analysis.

Discussion

Among hospitalized older adults with serious illness, a clinician-facing communication-priming intervention significantly improved EHR-documented goals-of-care discussions, with a greater effect size in racially or ethnically minoritized patients. These findings suggest that clinician-facing prompting interventions may promote goals-of-care discussions, particularly among racially or ethnically minoritized patients.

These findings are consistent with studies of other clinician-facing communication-priming interventions that have been tested in the outpatient setting among patients with serious illness. In 1 study27 of a clinician-facing intervention for patients with cancer, goals-of-care discussions in the treatment group increased from 1.3% to 4.6%. Two studies28,29 of clinician-directed communication training interventions that also had patient-specific communication prompts demonstrated reductions in patient-reported anxiety and depression in patients with cancer. Similarly, our prior RCT7 of a bilateral, patient- and clinician-facing Jumpstart Guide for outpatients with chronic life-limiting illness also found that the intervention was associated with an increase in patient-reported goals-of-care discussions. Notably, the proportion of patients in the usual care group with documented goals-of-care discussions was much lower in the current trial than in the previous outpatient RCT.7 This may be due to differences in implementation of the intervention (clinician-facing only in the current RCT vs patient- and clinician-facing in the outpatient RCT7), type of control group (usual care vs usual care with consent for enrollment and participant surveys), differences in serious illness communication between outpatient and inpatient clinical settings, or differences in the definition and measurement of the primary outcome.

Given the importance of goals-of-care discussions to patients, families, and clinicians,30,31,32,33 as well as research suggesting that communication-priming interventions may be effective in the hospital setting,34 we previously conducted a pilot trial of a bidirectional Jumpstart Guide for hospitalized patients.11 The pilot RCT11 found only a small number of goals-of-care discussions in the EHR overall (2% of 4642 notes for 150 patients), and a larger effect size (21% for the intervention group vs 8% for the usual care group) than the current RCT. The differences in findings between the pilot RCT11 and the current RCT may be explained by a number of factors. The current RCT was pragmatic and did not require participant consent because it was based on EHR data only (there were no survey data collected or used). The current RCT tested a clinician-facing intervention populated solely by EHR data, whereas the pilot trial11 tested a bidirectional intervention that required patient surveys to populate. The current RCT was conducted at 3 hospitals (including a community site) and had a larger proportion of patients with history of dementia, whereas the pilot trial11 was conducted at 2 hospitals. In addition, the primary outcome was measured over a different period in the current RCT (within 30 days of randomization) vs the pilot RCT11 (between randomization and hospital discharge), and also was measured using NLP-screened human abstraction rather than whole-chart manual abstraction.

The higher-touch design of the pilot trial11 (eg, survey-based tips, bidirectional distribution) may account for much of the difference in intervention effect observed between the pilot trial11 and the current trial. The bidirectional intervention tested in the pilot trial11 was designed to activate both clinicians and patients toward having goals-of-care discussions. In addition, there was a much lower proportion of patients with goals-of-care discussions in the usual care group in the pilot trial11 compared with the current study. Although the exact reason for this is unclear, we hypothesize that the substantial differences in screening, eligibility, and consent procedures between the 2 studies may have led to systematic differences in the characteristics of the patients enrolled.

An appealing feature of the pragmatic design of the current study is the ability to disseminate the intervention on a much wider scale than what can be achieved when requiring patient informed consent and completion of surveys. The size of the treatment effect found in the current study is of unclear clinical significance, although it suggests that such a nudge intervention can change clinician behavior. To have a more robust effect on goals-of-care discussions and change health care use, it seems likely that a stronger intervention is needed or that a clinician-facing intervention should be a component of a multifaceted intervention.

Although the aim of promoting goals-of-care discussions during hospitalization for acute illness is to promote decision-making for patients with serious illness,35 it is noteworthy that a statistically significant between-group difference was not detected for the secondary outcomes. This failure to influence the metrics associated with intensity of care may be attributable to both substantive and methodological factors. For example, goals-of-care discussions and their documentation may be of poor quality, failing to appropriately and adequately assess and describe patients’ goals or values and how they relate to patients’ treatment preferences.3,4,5,6 Even if goals-of-care discussions are conducted and well-documented, they may not be optimally timed or designed to meet patients’ needs; as such, care use outcomes may only be tenuously linked to the types of discussions promoted by the intervention. Furthermore, goals-of-care documentation may be difficult for other clinicians to find and access; such documentation, even when present in the EHR, may not allow treating clinicians to shape care plans based on these prior discussions.36,37,38 There remains much to be understood about the timeliness, content, quality, and documentation of goals-of-care discussions, and the relationship of these quality metrics and process measures with patient-centered, clinical, and care use outcomes.

An important finding of this RCT is that the intervention appeared to be more beneficial among racially or ethnically minoritized patients in increasing documented goals-of-care discussions. Racially or ethnically minoritized patients were one of several subgroup analyses that must be interpreted with caution. However, there are important racial and ethnic disparities in palliative and end-of-life care; for example, minoritized patient populations are less likely to receive hospice services,39 more likely to receive higher intensity care near the end of life,40,41 and more likely to report concerns regarding quality of care and clinician communication.42 Importantly, racially or ethnically minoritized patients with serious illness are also less likely to have EHR-documented goals-of-care discussions during an acute care hospitalization.43 These disparities highlight a need for racially and ethnically conscious research efforts in palliative care,44 and provide a strong rationale for developing interventions that can address these inequities. A prior study (not an RCT) of an advance care planning video and communication intervention also showed increased benefit among Black and Hispanic patients.45 The findings from the current RCT suggest that interventions to promote goals-of-care discussions may offer a useful approach to improve equity in serious illness communication.

Limitations

This study has many limitations. First, it was conducted in 1 region of the US and within 1 health care system at 3 hospitals, which may limit generalizability. Second, because data were extracted from EHRs within a single health care system, the findings are susceptible to measurement error in exposures and outcome misclassification, including outcomes occurring in other health systems.46 These risks were mitigated by focusing outcomes within 30 days rather than longer periods, by assessing covariates that are reliably documented in the EHR (demographic information, comorbidities),47 and by mitigating the potential for NLP-related misclassification through the use of NLP-screened human abstraction.25

Third, the findings may be biased by differential performance of the screening NLP model between the intervention and usual care groups, or by minoritized race or ethnicity. We believe this to be unlikely because the intervention does not modify existing documentation workflows, and the NLP model was trained on data that contained no textual documentation of the Jumpstart Guide or study-related activities. We also did not observe differential performance over these variables in the internal validation sample (eText and eFigures 1-2 in Supplement 2).

Fourth, the construct of goals-of-care discussions represents a spectrum of important discussions that are multifaceted and vary over dimensions of context, timing, depth, content, and execution—all of which influence the quality of goals-of-care discussions.48 Efforts are ongoing to refine the criteria by which goals-of-care discussions are defined and measured.13,43

Fifth, multiple racial and ethnic groups were combined into a single category for the analysis of differential treatment effects of the intervention. When racial subgroups and Hispanic ethnicity were examined separately in a prior study,43 the finding of decreased occurrence of goals-of-care discussions was maintained for Black and Asian patients. Future studies should strive to achieve power to examine groups separately.

Conclusions

Among hospitalized older adults with serious illness, a pragmatic clinician-facing communication-priming intervention significantly improved documentation of goals-of-care discussions in the EHR, with a greater effect size in racially or ethnically minoritized patients.

Section Editor: Christopher Seymour, MD, Associate Editor, JAMA (christopher.seymour@jamanetwork.org).

Trial protocol

eTable. Intervention effect on occurrence of NLP-identified goals-of-care discussions within specific racial groups and within specific ethnic groups

eText. NLP performance by randomization group or by race and ethnicity

eFigure 1. NLP performance over randomization groups within internal validation sample

eFigure 2. NLP performance over minoritized race or ethnicity within internal validation sample

eReference

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665-1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fakhri S, Engelberg RA, Downey L, et al. Factors affecting patients’ preferences for and actual discussions about end-of-life care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(3):386-394. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heyland DK, Dodek P, You JJ, et al. ; ACCEPT Study Team and the Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network (CARENET) . Validation of quality indicators for end-of-life communication: results of a multicentre survey. CMAJ. 2017;189(30):E980-E989. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1211-1218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teno JM, Gruneir A, Schwartz Z, Nanda A, Wetle T. Association between advance directives and quality of end-of-life care: a national study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):189-194. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01045.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtis JR, Downey L, Back AL, et al. Effect of a patient and clinician communication-priming intervention on patient-reported goals-of-care discussions between patients with serious illness and clinicians: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):930-940. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aslakson RA, Reinke LF, Cox C, Kross EK, Benzo RP, Curtis JR. Developing a research agenda for integrating palliative care into critical care and pulmonary practice to improve patient and family outcomes. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(4):329-343. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tulsky JA, Beach MC, Butow PN, et al. A research agenda for communication between health care professionals and patients living with serious illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1361-1366. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Au DH, Udris EM, Engelberg RA, et al. A randomized trial to improve communication about end-of-life care among patients with COPD. Chest. 2012;141(3):726-735. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee RY, Kross EK, Downey L, et al. Efficacy of a communication-priming intervention on documented goals-of-care discussions in hospitalized patients with serious illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e225088. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.5088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis JR, Sathitratanacheewin S, Starks H, et al. Using electronic health records for quality measurement and accountability in care of the seriously ill: opportunities and challenges. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(S2):S52-S60. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee RY, Kross EK, Torrence J, et al. Assessment of natural language processing of electronic health records to measure goals-of-care discussions as a clinical trial outcome. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(3):e231204. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curtis JR, Lee RY, Brumback LC, et al. Improving communication about goals of care for hospitalized patients with serious illness: study protocol for two complementary randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2022;120:106879. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2022.106879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodman DC, Fisher ES, Wennberg JE, Skinner JS, Chasan-Taber S, Bronner KK. Tracking improvement in the care of chronically ill patients: a Dartmouth Atlas brief on Medicare beneficiaries near the end of life. Published June 12, 2013. Accessed May 9, 2023. https://data.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/reports/EOL_brief_061213.pdf [PubMed]

- 16.Wennberg JE, Fisher ES, Goodman DC, Skinner JS. Tracking the Care of Patients with Severe Chronic Illness: The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care 2008. Trustees of Dartmouth College; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iezzoni LI, Heeren T, Foley SM, Daley J, Hughes J, Coffman GA. Chronic conditions and risk of in-hospital death. Health Serv Res. 1994;29(4):435-460. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaslavsky O, Zelber-Sagi S, LaCroix AZ, et al. Comparison of the simplified sWHI and the standard CHS frailty phenotypes for prediction of mortality, incident falls, and hip fractures in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(10):1394-1400. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. ; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group . Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146-M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hicks K, Downey L, Engelberg RA, et al. Predictors of death in the hospital for patients with chronic serious illness. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(3):307-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavin K, Davydow DS, Downey L, et al. Effect of psychiatric illness on acute care utilization at end of life from serious medical illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54(2):176-185.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sathitratanacheewin S, Engelberg RA, Downey L, et al. Temporal trends between 2010 and 2015 in intensity of care at end-of-life for patients with chronic illness: influence of age under versus over 65 years. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(1):75-81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.08.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown CE, Engelberg RA, Sharma R, et al. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and healthcare intensity at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(9):1308-1316. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steiner JM, Kirkpatrick JN, Heckbert SR, et al. Identification of adults with congenital heart disease of moderate or great complexity from administrative data. Congenit Heart Dis. 2018;13(1):65-71. doi: 10.1111/chd.12524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindvall C, Deng CY, Moseley E, et al. Natural language processing to identify advance care planning documentation in a multisite pragmatic clinical trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(1):e29-e36. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Secunda K, Wirpsa MJ, Neely KJ, et al. Use and meaning of “goals of care” in the healthcare literature: a systematic review and qualitative discourse analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1559-1566. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05446-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manz CR, Parikh RB, Small DS, et al. Effect of integrating machine learning mortality estimates with behavioral nudges to clinicians on serious illness conversations among patients with cancer: a stepped-wedge cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(12):e204759. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.4759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernacki R, Paladino J, Neville BA, et al. Effect of the serious illness care program in outpatient oncology: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(6):751-759. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paladino J, Koritsanszky L, Nisotel L, et al. Patient and clinician experience of a serious illness conversation guide in oncology: a descriptive analysis. Cancer Med. 2020;9(13):4550-4560. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker E, McMahan R, Barnes D, Katen M, Lamas D, Sudore R. Advance care planning documentation practices and accessibility in the electronic health record: implications for patient safety. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(2):256-264. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):821-832.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sudore RL, Heyland DK, Lum HD, et al. Outcomes that define successful advance care planning: a Delphi panel consensus. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(2):245-255.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.08.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bischoff KE, Sudore R, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, Smith AK. Advance care planning and the quality of end-of-life care in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):209-214. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma C, Riehm LE, Bernacki R, Paladino J, You JJ. Quality of clinicians’ conversations with patients and families before and after implementation of the Serious Illness Care Program in a hospital setting: a retrospective chart review study. CMAJ Open. 2020;8(2):E448-E454. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20190193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):256-261. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinuff T, Dodek P, You JJ, et al. Improving end-of-life communication and decision making: the development of a conceptual framework and quality indicators. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(6):1070-1080. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernacki RE, Block SD; American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force . Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1994-2003. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.You JJ, Fowler RA, Heyland DK; Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network (CARENET) . Just ask: discussing goals of care with patients in hospital with serious illness. CMAJ. 2014;186(6):425-432. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen LL. Racial/ethnic disparities in hospice care: a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(5):763-768. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barnato AE, Herndon MB, Anthony DL, et al. Are regional variations in end-of-life care intensity explained by patient preferences?: a study of the US Medicare population. Med Care. 2007;45(5):386-393. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000255248.79308.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muni S, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, Dotolo D, Curtis JR. The influence of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status on end-of-life care in the ICU. Chest. 2011;139(5):1025-1033. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Welch LC, Teno JM, Mor V. End-of-life care in black and white: race matters for medical care of dying patients and their families. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1145-1153. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53357.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uyeda AM, Lee RY, Pollack LR, et al. Predictors of documented goals-of-care discussion for hospitalized patients with chronic illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2023;65(3):233-241. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown CE, Curtis JR, Doll KM. A race-conscious approach toward research on racial inequities in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(5):e465-e471. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volandes AE, Zupanc SN, Paasche-Orlow MK, et al. Association of an advance care planning video and communication intervention with documentation of advance care planning among older adults: a nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220354. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dziadkowiec O, Callahan T, Ozkaynak M, Reeder B, Welton J. Using a data quality framework to clean data extracted from the electronic health record: a case study. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2016;4(1):1201. doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wells BJ, Chagin KM, Nowacki AS, Kattan MW. Strategies for handling missing data in electronic health record derived data. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2013;1(3):1035. doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uyeda AM, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, et al. Mixed-methods evaluation of three natural language processing modeling approaches for measuring documented goals-of-care discussions in the electronic health record. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(6):e713-e723. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

eTable. Intervention effect on occurrence of NLP-identified goals-of-care discussions within specific racial groups and within specific ethnic groups

eText. NLP performance by randomization group or by race and ethnicity

eFigure 1. NLP performance over randomization groups within internal validation sample

eFigure 2. NLP performance over minoritized race or ethnicity within internal validation sample

eReference

Data sharing statement