Abstract

Intersectionality and minority stress frameworks were used to guide examination and comparisons of psychological distress (depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms) and protective factors (religiosity, spirituality, social support) among 673 Black, Latinx, and White lesbian and bisexual women with and without histories of sexual assault. Participants were from Wave 3 of the 21-year longitudinal Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women (CHLEW) study. More than one-third (38%) of participants reported having experienced adolescent or adult sexual assault (i.e., rape or another form of sexual assault) since age 14. Confirmatory factor analysis, structural equation modeling, and multivariate analyses of covariance were used to analyze the data. Results revealed that levels of religiosity/spirituality and psychological distress varied by race/ethnicity and by sexual identity (i.e., Black lesbian, Black bisexual, Latinx lesbian, Latinx bisexual, White lesbian, White bisexual). Black lesbian women reported the highest level of religiosity/spirituality whereas White lesbian women reported the lowest level. White bisexual women reported the highest level of psychological distress whereas White lesbian women reported the lowest level. We found no significant differences in reports of sexual assault or in social support (i.e., significant other, family, friend, and total social support). However, White lesbian women had higher friend, significant other, and total social support relative to the other five groups of women with minoritized/marginalized sexual identities. Future work should examine whether religiosity, spirituality, and social support serve as protective factors that can be incorporated into mental health treatment for lesbian and bisexual who have experienced sexual assault to reduce psychological distress.

Keywords: sexual assault, sexual minority women, mental health, spirituality and religiosity, protective factors, intersectionality

Adolescent/adult sexual assault (i.e., any unwanted sexual experience ranging from unwanted sexual contact to anal or vaginal penetration) occurs at higher rates among women with minoritized/marginalized sexual identities (e.g., lesbian, bisexual), hereafter referred to as sexual minority women (SMW), than among heterosexual women (Martin et al., 2011; Walters et al., 2010). Bisexual women experience higher rates of rape than either heterosexual or lesbian women (Heidt et al., 2005; Hequembourg et al., 2013), which suggests they experience more severe sexual assault. In studies of college populations (Edwards et al., 2015), community-based SMW (Hughes, McCabe, et al., 2010), and in studies comparing sexual minority individuals and their siblings (Balsam et al., 2005), sexual minority individuals report more interpersonal violence (Edwards et al., 2015), including childhood abuse and sexual assault (Balsam et al., 2005), relative to their heterosexual counterparts. Sigurvinsdottir and Ullman (2016) suggest two explanations for the higher rates of sexual assault among SMW: (1) because of their homophobic beliefs, perpetrators target SMW for harassment and violence; and (2) stressors related to the marginalization of SMW heightens their general levels of stress compared to heterosexual women. Higher levels of stressors are theorized to contribute to psychological distress and lead to greater engagement in high-risk behaviors (e.g., risky sexual behaviors) (Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2016), which may in turn place SMW at disproportionately higher risk for sexual assault (Goldstein et al., 2007). Thus, it is important to understand associations between sexual assault, psychological distress, and protective factors to ultimately help promote resilience.

SMW are more likely to report psychological distress than heterosexual women (Bostwick et al., 2010) largely due to the influence of minority stressors resultant from the marginalization and stigmatization of minoritized sexual identities (Meyer, 2003). Sexual minority stressors combined with SMW’s higher rates of sexual assault may further increase risk for psychological distress. Indeed, sexual assault survivors are at heightened risk for experiencing psychological distress, including depression (Au et al., 2013; Carey et al., 2018), anxiety (Carey et al., 2018), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Au et al., 2013). In a meta-analysis of sexual assault and psychopathology, more incidents and greater severity of sexual assault were associated with greater psychological distress (Dworkin et al., 2017). Heidt et al. (2005) found that SMW who experienced child sexual abuse, and/or adolescent/adult sexual assault had significantly higher rates of depression, general distress, and more symptoms of PTSD than SMW who did not report sexual assault.

Factors such as religion, spirituality, and social support may buffer the negative impacts of violence and play a role in post-assault recovery. It may be important to consider race/ethnicity when exploring protective factors among SMW who have experienced sexual assault. In a meta-analysis, Ano and Vasconcelles (2005) found positive religious coping (e.g., forgiveness) to be associated with better psychological adjustment. Among sexual assault survivors who reported that they believed in God, Black women were more likely than Latinx and White women to turn to spirituality to cope with sexual assault (Ahrens, Abeling, et al., 2010). In addition, Latinx women sexual assault survivors who used religion to cope reported higher levels of psychological well-being relative to Latinx women survivors who did not use religion to cope (Ahrens, Abeling, et al., 2010). In addition, spirituality, which is more common than religiosity among SMW, may provide some protections against minority stress (Drabble et al., 2017). Social support has also been found to moderate the negative impact of childhood and adult sexual assault (Bryant-Davis et al., 2012). Among SMW whose families or peers are religious and/or oppose same-sex sexual experiences, Black and Latinx SMW may receive less social support than do White SMW (Barnes & Meyer, 2012).

Intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989) is helpful in understanding how various social statuses such as gender, race/ethnicity, and sexual identity intersect at the individual level. Women who are sexual and racial/ethnic minorities can be conceptualized as multiply marginalized (i.e., they experience marginalization due to their sexual, racial/ethnic, and gender identities). Studies comparing rates of adult sexual assault by race/ethnicity report varying findings (Bryant-Davis et al., 2009). However, it is well established that Black women report experiencing rape at a rate 50% higher than do White and Latinx women, and Latinx women report lower rates of sexual assault compared to White and Black women (Black et al., 2011). These rates may be artificially low, as Latinx women may be less likely to disclose sexual assault because of their cultural beliefs (Ahrens, Rios-Mandel, et al., 2010).

Little research has examined SMW of color’s (SMWOC) experiences and associated correlates of sexual assault and how those may differ from those of White SMW (Balsam et al., 2015). Bostwick et al. (2019) found that although Black and Latinx SMW report higher rates of lifetime sexual assault than White SMW, they report lower or similar rates of depression. Similarly, Balsam et al. (2015) found that despite young SMWOC’s reporting more socioeconomic stressors and discrimination, mental health symptoms were similar to their White counterparts. However, in comparisons between heterosexual and SMW of color the latter often report more psychological distress (e.g., depression, PTSD symptoms) (Balsam, et al., 2015; Bostwick et al., 2019). Overall, findings suggest that although SMWOC report more psychological distress than heterosexual women of color, they do not report more distress than White SMW—despite SMWOC’s higher rates of trauma (Bostwick et al., 2019). Findings suggest the importance of considering racial/ethnic differences in potential protective factors for psychological distress among SMW.

Past work has examined the role of risk and protective factors for psychological distress outcomes among SMW (Tyler & Ray, 2021), psychological distress and suicidality among Black and White sexual minority adults (Almazan, 2019), and associations between sex, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation and depressive symptoms (Holm et al., 2021). However, this study extends prior work by examining racial/ethnic and sexual identities simultaneously among women while considering: (1) levels of psychological distress and protective factors, and (2) history of sexual assault. Current research suggests that both race/ethnicity and sexual identity are important for understanding sexual assault and psychological distress in SMW (Bostwick et al., 2019). There is far less research examining the association between protective factors and psychological distress among SMWOC versus White SMW.

The aims of this study were twofold: (1) examine the interaction between race/ethnicity and sexual identity (i.e., Black lesbian or bisexual, Latinx lesbian or bisexual, and White lesbian or bisexual) on levels of psychological distress (i.e., depression, anxiety, PTSD) and in protective factors (i.e., spirituality, religiosity, social support) in women with and without histories of sexual assault; and (2) among women with and without histories of sexual assault, examine the role of different types of social support (i.e., friend, family, significant other, and total) and whether the association between social support and sexual assault varies by race/ethnicity and sexual identity. Given the paucity of research related to SMW’s multiple marginalized statuses (e.g., gender, sexual identity, race/ethnicity), the study hypotheses were novel but limited in scope. Specifically, it was expected that: (1) SMWOC would report more protective factors than White SMW; and (2) psychological distress (i.e., depression, anxiety, PTSD) would not differ significantly between White SMW and SMWOC.

Methods

Data were from Wave 3 of the Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women Study (CHLEW), a 21-year longitudinal study of SMW’s health. Wave 3 of CHLEW included 722 participants who identified as only lesbian (n = 397), mostly lesbian (n = 118), bisexual (n = 180), mostly heterosexual (n = 8), only heterosexual (n = 6), other (n = 11), or refused to answer (n = 2). Only women who identified as only lesbian/mostly lesbian or bisexual (n = 698) were included in the present study. Women who identified as mostly or only lesbian were combined because they did not differ on any of the key study variables. Participants were racially and ethnically diverse, with 37.4% White, 36.0% Black, and 23.2% Latinx. Given their small numbers, 25 women who identified as Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 10), Native American/Alaskan Native (n = 13), or who indicated that they “don’t know” their race/ethnicity (n = 2) were excluded. The final sample included 673 Black, Latinx, and White SMW. Participants’ mean age was 40.0 (SD = 14.3); 32.2% had completed some college, 26.6% had completed graduate or professional school, 21.1% had a bachelor’s degree, 12.6% a high school diploma/GED, 7.3% some high school, and 1.0% had an eighth grade education or less (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Self-Report Measure |

Lesbian Women |

Bisexual Women |

Total |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. | Percentage, % | Freq. | Percentage, % | Freq. | Percentage, % | |

|

| ||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 199 | 39.7 | 62 | 36.0 | 261 | 38.8 |

| Black | 184 | 36.7 | 66 | 38.4 | 250 | 37.1 |

| Latinx | 118 | 23.6 | 44 | 25.6 | 162 | 24.1 |

| Education | ||||||

| 8th grade or less | 2 | 0.4 | 5 | 2.9 | 7 | 1.0 |

| Some high school (HS) | 29 | 5.8 | 19 | 11.0 | 48 | 7.1 |

| HS Diploma | 57 | 11.4 | 28 | 16.3 | 85 | 12.6 |

| Some college | 158 | 31.4 | 52 | 30.2 | 210 | 31.2 |

| Bachelor’s | 110 | 22.0 | 33 | 19.2 | 143 | 21.2 |

| Graduate School | 144 | 28.7 | 35 | 20.3 | 179 | 26.6 |

| Relationship status | ||||||

| Single/dating | 148 | 29.5 | 78 | 45.3 | 226 | 33.6 |

| In a relationship | 105 | 21.0 | 45 | 26.2 | 150 | 22.3 |

| Living w/Partner | 220 | 43.9 | 40 | 23.3 | 260 | 38.6 |

| Separated | 23 | 4.6 | 5 | 2.9 | 28 | 4.2 |

| Partner died | 4 | 0.8 | 2 | 1.2 | 6 | 1.3 |

Note. Single/dating = not in a committed relationship. In a relationship = in a committed relationship, not living with a partner. Living w/partner = living with a partner in a committed relationship. Partner died = in a past relationship in which the partner had died.

Procedure

Wave 3, conducted in 2010–2012, included participants from the original CHLEW sample (n = 354) and a new supplemental sample (n = 368) of younger (ages 18–25), bisexual, and additional Black and Latinx women. Face-to-face interviews that lasted 60–90 minutes were conducted by female interviewers. Although the CHLEW is a longitudinal study, Wave 3 includes the largest and most diverse sample and was the most recent Wave completed at the time of the current study. Waves 4 and 5 of the CHLEW were not yet completed when the current study was conducted (see Hughes et al., 2021 for a detailed description of the study and its participants).

Measures

Adolescent sexual assault.

We used a well-validated child sexual abuse (CSA; Wyatt, 1985) measure to assess adolescent sexual assault. Participants were asked about sexual experiences before the age of 18, ranging from exposure and fondling to anal and vaginal penetration (e.g., “Did someone ever ask you or force you to show them any of your private or sexual parts?”) To differentiate child and adolescent experiences of sexual assault/abuse, we used an age cutoff of 14 for CSA (Livingston et al., 2007). Sexual assault that occurs between ages 14 and 17 has characteristics more similar to adult sexual assault than to child sexual abuse (Livingston et al., 2007). Thus, women who experienced child sexual abuse using Wyatt’s criteria (Wyatt, 1985) from the age of 14–17 were reclassified as having experienced adolescent sexual assault. Using the new modified criteria, we created a dichotomous variable for sexual assault experiences (i.e., 0 = no adolescent sexual assault; 1 = adolescent sexual assault).

Adult sexual assault.

Adult sexual assault questions included: “Since age 18, have you ever been raped, that is, someone had sexual intercourse with you, when you did not want to, by threatening you or using some degree of force (yes/no)?” and “Have you ever experienced any other kind of sexual assault (yes/no)?” Experiences of adolescent (ages 14–17) and adult sexual assault (ages 18 and over) were used to calculate the study’s sexual assault variable (0 = no sexual assault; 1 = sexual assault; adolescent or adult sexual assault). The final sexual assault variable was coded to include experiences after the age of 14 to be consistent with sexual assault literature that defines and assesses assault after the age of 14 (Koss et al., 1987). No psychometric data exist for this item, but this has been used in prior work (Drabble et al., 2017).

Psychological Distress

National Institute of mental health diagnostic interview schedule current depression.

The CHLEW used the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS)-Depression measure. This includes a 14-item measure that approximates a clinical diagnosis of depression according to diagnostic statistical manual-III (DSM-III) criteria (Robins et al., 1981). The current study used a symptom count by tallying the number of yes responses for the total number of symptoms of depression (range = 0–8). In the current study, the internal consistency was 0.77.

Anxiety.

Anxiety was assessed using one item, “Have you ever considered yourself to be a ‘nervous or anxious’ person about things other people would not usually worry about?” (yes/no) (yes = 1, no = 0) (Wilsnack et al., 1997). There are no psychometrics for this item, but it has been used in prior work (Johnson et al., 2013) and was adapted from the neuroticism scale of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1991).

Short screening scale for posttraumatic stress disorder.

This 7-item measure was used to screen for potential lifetime PTSD in participants exposed to traumatic events as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (APA, 1994). This PTSD measure was chosen to reduce participant burden, due to its validity for use with a community sample and its strong concordance with PTSD-related symptoms included in PTSD structured interviews (Breslau et al., 1999; (Kimerling et al., 2006), and because it has been used successfully in other large-scale studies (Roberts et al., 2011; Trudel-Fitzgerald et al., 2016) as well as in the NESARC (Bohnert & Breslau, 2011). A score of four or greater on this scale indicated a “positive case” (i.e., likely meeting DSM-IV criteria) of PTSD. However, this is simply a screening tool which does not provide an actual PTSD diagnosis. In the current study, the internal consistency of this scale was 0.81.

Protective Factors

Religiosity.

Consistent with prior work (Drabble et al., 2017), religiosity was assessed by asking “Would you say that you currently are”: very religious, somewhat religious, not at all religious (range = 0–2).

Spirituality.

Similarly, spirituality was assessed using the following question: “We would also like to know about your spirituality. By ‘spirituality’ we mean how often you spend time thinking about the ultimate purpose of life or your own relationship to a higher power in life. In this sense, would you say that you currently are”: very spiritual, somewhat spiritual, not at all spiritual (range = 0–2). No psychometric data exist for this item, but this item has been used in prior work (Drabble et al., 2017).

Frequency of prayer.

The prayer question asked, “About how often do you pray?” and had Likert options from (5) several times a day to (0) never (range = 0–5). No psychometric data exist for this item, but this item has been used in prior work (Drabble et al., 2017).

The multidimensional scale of perceived social support.

(MSPSS; Zimet et al., 1988). The MSPSS is a 12-item measure that assessed perceived social support from (1) significant other, (2) family, and (3) friends. Response options were on a Likert-scale that ranged between 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). Subscale scores were calculated by summing responses for each of the four items on each subscale. In addition to social support from the three sources listed above we also calculated a total social support score by summing responses to questions about the three sources of social support. The MSPSS has shown good internal reliability with alphas ranging from .84 to .92. In the current study, the internal consistency was 0.90. The subscales’ individual reliability alphas were adequate: significant other (0.91), family (0.94), and friends (0.93).

Sexual identity.

Sexual identity was assessed using an item that asked participants, “How do you define your sexual identity? Would you say that you are: ‘only lesbian/gay,’ ‘mostly lesbian/gay,’ ‘bisexual,’ ‘mostly heterosexual,’ ‘only heterosexual/straight’ or ‘other.’” Given similarities in outcomes for women who identified as only lesbian and mostly lesbian we combined these two groups in the current study. Women who identified as mostly or only heterosexual were excluded.

Data Analytic Strategy

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), structural equation modeling (SEM), and multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVA) were used to test this study’s hypotheses. SEM allows for the examination of latent constructs that are not observable by considering several variables per latent construct simultaneously. This approach leads to more valid conclusions at the construct level and reduces measurement error (Kline, 2011). SPSS 27 was used to conduct MANCOVAs while Mplus version 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) was used to conduct CFA and SEM analyses. The expectation maximization (EM) algorithm was used to obtain maximum likelihood estimation with robust weighted least squares WLS (WLSMV). Acceptable fit for CFA and SEM analyses was determined if the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1993) values were less than 0.10, Standardized Root Mean and Square Residual (SRMR; Hu & Bentler, 1999) values were less than 0.08, and Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990) values were greater than 0.90 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Given the large sample size, models were considered to have acceptable fit if the chi square was significant (Kline, 2011).

Using CFA, individual factors scores (i.e., composite scores) were calculated to give each participant a score for each of the latent constructs. Using factor scores for SEM is a longstanding and accepted practice (DiStefano et al., 2009) when full scalar invariance is not achieved by the data. Our final factor model assumed full partial scalar invariance of indicators for religiosity, spirituality, depression, and anxiety, while allowing intercepts of PTSD and prayer indicators to vary across groups beyond differences in factor scores (Byrne et al., 1989). Factor scores provide information about an individual’s placement on the latent constructs and are standardized with a mean of zero. Thus, scores can fall above or below the mean and can be negative if they fall below the group’s mean (DiStefano et al., 2009). Additionally, sociodemographic variables were controlled for in the analyses. Age of the participant was used as a continuous variable. Education was coded as a categorial variable: (1) no formal schooling, (2) eighth grade or less, (3) some high school, (4) high school diploma or GED, (5) some college, (6) bachelor’s degree, and (7) graduate or professional school. Having children living in the household was coded dichotomously (yes/no).

Results

Measurement Model

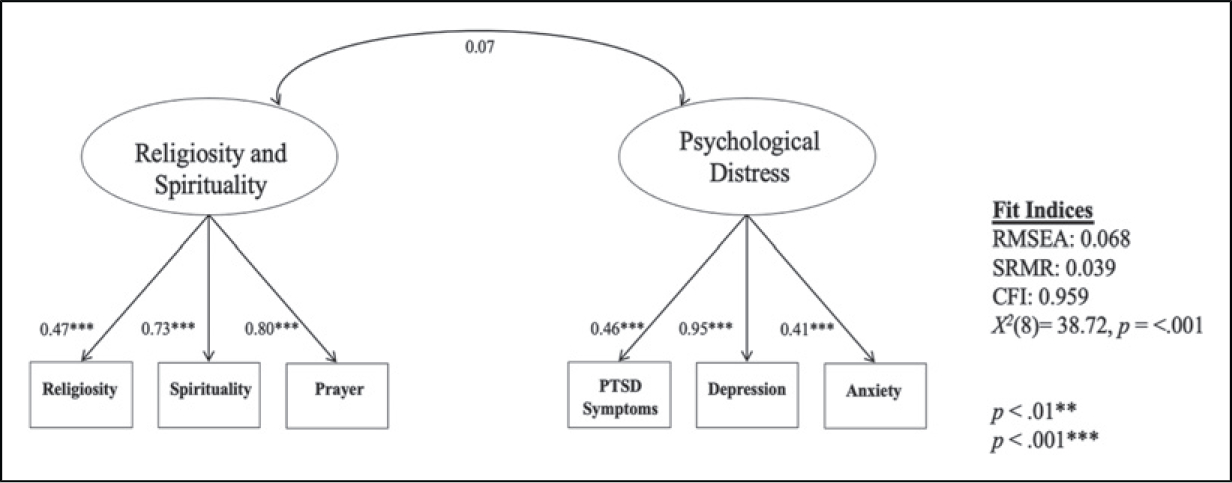

We evaluated a preliminary measurement model with two latent constructs: protective factors and psychological distress. Protective factors indicators included spirituality, religiosity, prayer, and social support. Psychological distress indicators included symptoms of PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Protective factors and psychological distress were allowed to covary. Unit loading identification was used to scale the latent factors and all other parameters were freely estimated. The results indicated that the model provided poor fit to the data, (χ2 (13) = 113.03, p < .001, RMSEA = .107 (90% CI [.089–.125]), SRMR = .060, CFI = .849). Two alternative models guided by theory were tested: (1) frequency of prayer removed; and (2) social support removed. For example, social support was removed because it was theoretically different from religiosity, spirituality, and frequency of prayer. While the first model did not improve model fit, dropping social support did so. Once social support was dropped, (Figure 1) results indicated that the model provided adequate fit to the data, χ2 (8) = 38.72, p < .001, RMSEA = .068 (90% CI [.045–.093]), SRMR = .039, CFI = .959. The latent construct, protective factors, was renamed religiosity/spirituality to be more descriptive. Religiosity/spirituality and psychological distress were not significantly associated in the model.

Figure 1.

Final measurement model.

Religiosity/Spirituality and Psychological Distress Findings

A MANCOVA was conducted to examine the role of religiosity/spirituality and psychological distress in the context of sexual assault. The variable race/ethnicity grouped by sexual identity (1 = White lesbian, 2 = Black lesbian, 3=Latinx lesbian, 4=White bisexual, 5= Black bisexual, 6= Latinx bisexual) was included as a grouping variable (i.e., independent variable). Sexual assault was included as an independent variable. Religiosity/spirituality and psychological distress were included as dependent variables. Results from the MANCOVA indicated that there was no statistically significant interaction effects for race/ethnicity by sexual identity and sexual assault on religiosity/spirituality and psychological distress, F (10, 1196) = 0.75, p = .988, Wilk’s Λ = .998, partial η2 = .006.

We found a statistically significant main effect for sexual assault on both dependent variables (religiosity/spirituality and psychological distress): F (2, 598) = 14.03, p < .001, Wilk’s Λ = .955, partial η2 = .045. Tests of between-subject effects revealed that religiosity/spirituality, F (1, 613) = 15.36, p = .001 and psychological distress F (1, 613) = 17.09, p < .001 varied based on whether participants reported any versus no sexual assault, confirming a main effect. A one-way ANOVA was conducted to compare religiosity/spirituality and psychological distress in women who did not report sexual assault (n = 382) and women who did (n = 235). Women who did not report sexual assault had lower levels of religiosity/spirituality (M = .04, SD = 0.72) than women who did (M = 0.24, SD = 0.77); F (1, 616) = 10.25, p < .01. Additionally, women who did not report sexual assault reported lower levels of psychological distress (M = −.05, SD = 0.78) than women who did (M = 0.28, SD = 0.71); F (1, 616) = 14.21, p < .01.

Results of the MANCOVA analyses indicated that there was a statistically significant main effect for race/ethnicity by sexual identity on both religiosity/spirituality and psychological distress: F (10, 1196) = 12.70, p < .001, Wilk’s Λ = .817, partial η2 = .096. Tests of between-subject effects indicated a significant main effect for race/ethnicity by sexual identity on religiosity/spirituality, F (5, 614) = 20.30, p < .001 and on psychological distress F (5, 614) = 3.87, p < .01.

Follow-up pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections indicated that Black lesbian (M = 0.52, SD = 0.52) and Black bisexual (M = 0.28, SD = 0.52) women had the highest levels of religiosity/spirituality of women in the study. White bisexual (M = 0.50, SD = 0.70) and Latinx bisexual (M = 0.44, SD = 0.70) had the highest levels of psychological distress and White lesbian women (M = 0.02, SD = 0.84) had the lowest levels (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted Means for Religiosity/Spirituality and Psychological Distress across Race/Ethnicity by Sexual Identity.

| Religiosity/ Spirituality |

Psychological Distress |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intersectionality Group | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

|

| ||||

| Black lesbian women | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.11 | 0.72 |

| Black bisexual women | 0.28 | 0.52 | 0.08 | 0.66 |

| Latinx lesbian women | −0.04 | 0.62 | 0.22 | 0.74 |

| Latinx bisexual women | 0.02 | 0.87 | 0.44 | 0.70 |

| White lesbian women | −0.01 | 0.80 | 0.02 | 0.84 |

| White bisexual women | −0.50 | 0.83 | 0.50 | 0.70 |

| All SMW | 0.12 | 0.75 | 0.15 | 0.76 |

Social Support Findings

To address Aim 2, we used MANCOVA to examine the role of social support for friends, family members, and significant other. Race/ethnicity by sexual identity was included as a grouping variable and sexual assault was included as an independent variable. The different types of social support were included as dependent variables. Results from the MANCOVA indicated that there was no statistically significant interaction of race/ethnicity by sexual identity and sexual assault on the dependent variables social support, friend, family, and significant other support: F (20, 1977) = 0.72, p = .809, Wilk’s Λ = .976, partial η2 = .006. Results of the MANCOVA indicated no significant main effect for sexual assault on all four types of social support: F (4, 596) = 2.66, p = .468, Wilk’s Λ = .994, partial η2 = .006.

We did find a main effect for race/ethnicity by sexual identity on the dependent variables, F (20, 1977) = 2.66, p < .001, Wilk’s Λ = .916, partial η2 = .022. Tests of between-subject effects with Bonferroni corrections showed main effects across race/ethnicity by sexual identity (see Table 3) for total social support, F (5, 613) = 4.46, p = .001, friend social support, F (5, 613) = 7.20, p < .001, and significant other support, F (5, 613) = 4.28, p = .001. The total social support mean for White lesbian women was significantly higher than for Black lesbian women, p < .001, but not statistically different from the means of Latinx lesbian women or White bisexual women. Among lesbian women, the mean friend social support score for White women was significantly higher than for Black women, but there was no difference between White and Latinx lesbian women. There was also no significant difference in friend social support between White lesbian and bisexual women. However, Latinx lesbian women reported significantly higher levels of social support from friends than did Latinx bisexual women, p = .030. In terms of support from significant others, White lesbian women reported significantly higher support than Black lesbian women, p = .002, but they did not differ significantly from White bisexual women or Latinx lesbian women. Across the three race/ethnicities, the trend for bisexual women’s lower rates of all types of social support compared to lesbian women was apparent.

Table 3.

Adjusted Means for Social Support Variables across Race/Ethnicity by Sexual Identity.

| Support Variable | Black SMW |

Latinx SMW |

White SMW |

All SMW |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bisexual |

Lesbian |

Bisexual |

Lesbian |

Bisexual |

Lesbian |

Total |

|||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Social support | 63.58 | 11.15 | 63.33 | 12.44 | 63.72 | 15.80 | 66.57 | 12.64 | 67.34 | 12.29 | 69.52 | 10.38 | 66.17 | 12.51 | |

| Friend support | 21.60 | 4.21 | 21.93 | 5.18 | 20.55 | 6.01 | 22.99 | 4.44 | 23.20 | 4.28 | 24.24 | 3.69 | 22.80 | 4.66 | |

| Significant other | 21.45 | 3.98 | 21.58 | 4.62 | 21.60 | 5.36 | 22.45 | 4.42 | 23.13 | 4.19 | 23.71 | 4.10 | 22.50 | 4.47 | |

| Family support | 19.29 | 6.32 | 18.38 | 6.80 | 20.07 | 6.74 | 19.58 | 6.62 | 19.1 1 | 6.31 | 29.98 | 7.30 | 19.33 | 6.84 | |

Discussion

The current study adds to the growing body of literature on racial/ethnic differences in health disparities among SMW. We compared psychological distress (i.e., symptoms of depression, anxiety, PTSD) and protective factors (i.e., spirituality, religiosity, social support) in a community-based sample of Black, Latinx, and White lesbian and bisexual women with and without histories of adoslecent/adult sexual assault. This study’s findings augment the current literature by providing a better understanding of how intersecting identities are associated with protective factors and psychological distress, and how they vary in multiply marginalized women.

Findings related to Hypothesis 1 were complex. While we initially hypothesized that SMWOC would report more protective factors than White SMW, we found that this was the case only for a few types of protective factors. For example, SMWOC reported higher levels of religiosity/spirituality than White SMW. Specifically, Black lesbian women reported the highest levels of religiosity/spirituality while White lesbian women reported the lowest. For all SMW in our study, sexual assault was associated with higher levels of both religiosity/spirituality and psychological distress. Future work should examine whether religiosity/spirituality serves as a protective factor that can be incorporated into mental health treatment for Black lesbian women to reduce psychological distress associated with sexual assault. By understanding differences in protective factors, healthcare providers can better support SMW who experience sexual assault.

Despite SMWOC reporting higher levels of religiosity and spiritualty they reported lower social support. Contrary to Hypothesis 1, compared with White SMW, Black and Latinx bisexual women reported the lowest levels of social support, friend support, and significant other support. Differences in levels of social support are important given that social support is a powerful tool, particularly during a survivor’s post assault recovery (Bryant-Davis et al., 2012). For example, in a sample of Black female sexual assault survivors, women who experienced greater social support were less likely to report symptoms of depression and PTSD (Bryant-Davis et al., 2012). Bisexual women of color reported the lowest levels of social support. This finding was not surprising given previous research findings indicating that bisexual individuals report experiencing discrimination, microaggressions, and binegativity both from heterosexual and other monosexual sexual minorities (Balsam et al., 2011). Moreover, Meyer et al. (2008) found that racial/ethnic minority lesbian, gay, and bisexual people (LGBs) reported having smaller social support networks than did White LGBs. Having a smaller social support network does not necessarily translate into fewer opportunities to receive social support, but it does indicate that there are fewer people to whom racial/ethnic minority LGBs can go for support.

While prior work has found that Black sexual assault survivors who endorsed greater engagement in religious coping also reported greater symptoms of depression and PTSD (Bryant-Davis et al., 2011), we did not find a significant association between these variables. This discrepancy in findings might be explained by the difference in the latent construct being measured. For example, frequency of prayer is more reflective of engagement in this activity and does not provide insight into how this protective factor is actually being used. While our item on frequency of prayer sheds light on how frequently SMW in the study pray, it fails to tell us whether they use prayer to decrease their stress or as a form of religious repentance or punishment. Future work might endeavor to disentangle this complex relationship as it is particularly relevant for women with minoritized sexual identities, as religious beliefs can create identity conflict, especially if they are associated with religions that condemn sexual minority status and behaviors (Barnes & Meyer, 2012; Beagan & Hattie, 2015).

Contrary to Hypothesis 2, psychological distress did differ significantly between White SMW and SMWOC. Latinx and White bisexual women reported the highest levels of psychological distress. This is consistent with literature which suggests that bisexual women may experience higher levels of stress than lesbian women given their lower acceptance among both heterosexual and lesbian and gay communities (Balsam et al., 2011). These nuanced findings highlight the importance of using intersectionality as a framework in studies of sexual minority people.

This study is not without limitations. The adult sexual assault measure was not behaviorally-specific. As such, we were unable to assess assault severity and reporting of adult sexual assault relied on women labeling their experience as such. Given that many women who experience sexual assault may not perceive their experience as assault, our measure likely led to underreporting (Koss et al., 1987).

Various items including items in the protective factor latent construct were single items without psychometrics, thus, findings related to these variables should be interpreted with caution. The measure of depression used DSM-III criteria, rather than the newer DSM-IV or DSM-V criteria; thus, findings related to depression may have differed if a measure using the newer criteria had been used. Because the study used non-probability methods to recruit the sample, and because all SMW in the study were recruited from the Chicago metropolitan area, study findings may not generalize to all lesbian and bisexual women, particularly those who live in less urban or rural locations. Although less visible a decade ago, an increasing number of women are identifying as asexual, mostly heterosexual, pansexual or sexually fluid. Research is needed that includes large enough samples of these groups to better understand how they may be similar to or different from lesbian and bisexual women. Thus, more research is needed on diverse subgroups of women with minoritized/marginalized sexual identities.

Sexual violence towards SMW continues to be a major public health problem. Future longitudinal studies of SMW are needed to illuminate the role of protective factors in ameliorating psychological distress among sexual assault survivors. Assessing protective factors and psychological distress in near-real time using ecological momentary assessment (EMA) could help us better understand the sexual assault experiences of sexual minority women. Such information is needed to develop more effective intervention and treatment strategies such as ecological momentary interventions (EMI) that take a strengths-based approach (Xie, 2013) and that consider women’s cultural identities. Such approaches may prove to be an effective way of reducing psychological distress among SMW who have experienced sexual assault.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express gratitude to the women who participated in the CHLEW study as well as to Dr. Blake Boursaw and Kelly Martin who contributed to the development of this manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The CHLEW study and Dr. Hughes’ work on this study were supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA13328–15). Training support was provided to Dr. López (T32AA007459, PI Monti). Dr. Veldhuis’ work on this manuscript was supported by an NIH F32 and an NIH K99/R00 (F32AA025816; K99AA028049; PI Veldhuis). Note: the content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIAAA or NIH.

Biographies

Author Biographies

Gabriela López, PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences, Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies at Brown University’s School of Public Health. Her research focuses on the intersection of alcohol use and sexual assault among sexual minority women.

Elizabeth A. Yeater, PhD, is a Professor of Psychology and director of Clinical Training in the Department of Psychology at the University of New Mexico. Her reserach focuses on identifying contextual and interpersonal factors associated with women’s risk of sexual victimization by using social informaiton processing model and methods borrowed from cognitive science.

Cindy B. Veldhuis, PhD, is an associate research scientist and a research psychologist at the Columbia University School of Nursing. She is interested in mixed-methods approaches to examining associations between stress and alcohol use among women in same sex relationships.

Kamilla L. Venner, PhD, is an associate professor at the University of New Mexico. She is interested in substance use treatments and culturally effective adaptations of evidence based treatments. She is also interested in American Indian/Alaskan Native populations.

Steven P. Verney, PhD, is an Alaska Native (Tsimshian) Professor in the department of Psycholgy at the University of new Mexico. He is interested in cultural factors in cogntive assessment, cognitive aging, and physical and mental health dispartieis. He is also interested in the wellbeing in older Native Americans.

Tonda L. Hughes, PhD, RN, FAAN, is Professor Emerita at the University of Illinois at Chicago and is currently a Professor of International Nursing in Psychiatry and Associate Dean for Global Health Research at the School of Nursing at Columbia University. She is interested in factors that influence the health of sexual minority women particularly in the area of substance use.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ahrens CE, Abeling S, Ahmad S, & Hinman J (2010). Spirituality and well-being: The relationship between religious coping and recovery from sexual assault. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(7), 1242–1263. 10.1177/0886260509340533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens CE, Rios-Mandel LC, Isas L, & del Carmen Lopez M (2010). Talking about interpersonal violence: Cultural influences of Latinas’ identification and disclosure of sexual assault and intimate partner violence. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2(4), 284–295. 10.1037/a0018605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almazan E (2019). Are Black Sexual Minority Adults More Likely to Report Higher Levels of Psychological Distress than White Sexual Minority Adults? Findings from the 2013–2017 National Health Interview Survey. Social Sciences, 8(1), 14. 10.3390/socsci8010014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ano GG, & Vasconcelles EB (2005). Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(4), 461–480. 10.1002/jclp.20049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Au TM, Dickstein BD, Comer JS, Salters-Pedneault K, & Litz BT (2013). Co-occurring posttraumatic stress and depression symptoms after sexual assault: A latent profile analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 149(1–3), 209–216. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Molina Y, Beadnell B, Simoni J, & Walters K (2011). Measuring multiple minority stress: The LGBT People of Color Micro- aggressions Scale. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(2), 163–174. 10.1037/a0023244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Molina Y, Blayney JA, Dillworth T, Zimmerman L, & Kaysen D (2015). Racial/ethnic differences in identity and mental health outcomes among young sexual minority women. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(3), 380–390. 10.1037/a0038680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Rothblum ED, & Beauchaine TP. (2005). Victimization over the life span: a comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. J Consult Clin Psychol, 73(3), 477–87. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes DM, & Meyer IH (2012). Religious affiliation, internalized homophobia, and mental health in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(4), 505–515. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01185.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beagan BL, & Hattie B (2015). Religion, spirituality, and LGBTQ identity integration. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 9(2), 92–117. 10.1080/15538605.2015.1029204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Chen J, & Stevens MR (2011). The national intimate partner and sexual violence surveys (NISVS): 2010 summary report. National Center for Injury and Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert KM, & Breslau N (2011). Assessing the performance of the short screening scale for post-traumatic stress disorder in a large nationally-representative survey: Short screening scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 20(1), Article e1–e5. 10.1002/mpr.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, & McCabe SE (2010). Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 100(3), 468–475. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, Steffen A, Veldhuis CB, & Wilsnack SC (2019). Depression and victimization in a community sample of bisexual and lesbian women: An intersectional approach. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(1), 131–141. 10.1007/s10508-018-1247-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Peterson EL, Kessler RC, & Schultz LR (1999). Short screening scale for DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(6), 908–911. 10.1176/ajp.156.6.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, & Cudeck R (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Bollen KA & Long JS (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T, Chung H, Tillman S, & Belcourt A (2009). From the margins to the center: Ethnic minority women and the mental health effects of sexual assault. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 10(4), 330–357. 10.1177/1524838009339755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T, Ullman SE, Tsong Y, & Gobin R (2011). Surviving the storm: the role of social support and religious coping in sexual assault recovery of African American women. Violence Against Women, 17(12), 1601–18. DOI: 10.1177/1077801211436138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T, Ullman SE, Tsong Y, & Gobin R (2012). Surviving the storm: The role of social support and religious coping in sexual assault recovery of African American women. Violence Against Women, 17(12), 1601–1618. 10.1177/1077801211436138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM, Shavelson RJ, & Muthén B (1989). Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: the issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin, 105(3), 456–466. 10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.456 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Norris AL, Durney SE, Shepardson RL, & Carey MP (2018). Mental health consequences of sexual assault among first-year college women. Journal of Am Coll Health, 66(6), 480–486. 10.1080/07448481.2018.1431915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine feminist theory and antiracist politics. The University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1(8), 139–167). [Google Scholar]

- DiStefano C, Zhu M, & Mindrila D (2009). Understanding and using factor scores: Considerations for the applied researcher. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 14(20), 1–11. 10.7275/da8t-4g52. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L, Veldhuis CB, Riley BB, Rostosky S, & Hughes TL (2017). Relationship of religiosity and spirituality to hazardous drinking, drug use, and depression among sexual minority women. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(13), 1734–1757. 10.1080/00918369.2017.1383116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin ER, Menon SV, Bystrynski J, & Allen NE (2017). Sexual assault victimization and psychopathology: A review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 56, 65–81. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM, Sylaska KM, Barry JE, Moynihan MM, Banyard VL, Cohn ES, Walsh WA, & Ward SK (2015). Physical dating violence, sexual violence, and unwanted pursuit victimization: A comparison of incidence rates among sexual-minority and heterosexual college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(4), 580–600. 10.1177/0886260514535260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, & Eysenck SBG (1991). Manual of the Eysenck personality Questionnaire. Hodder & Stoughton. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, Barnett NP, Pedlow CT, & Murphy JG (2007). Drinking in conjunction with sexual experiences among at-risk college student drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(5), 697–705. 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidt JM, Marx BP, & Gold SD (2005). Sexual revictimization among sexual minorities: A preliminary study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 533–540. 10.1002/jts.20061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hequembourg AL, Livingston JA, & Parks KA (2013). Sexual victimization and associated risks among lesbian and bisexual women. Violence Against Women, 19(5), 634–657. 10.1177/1077801213490557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm AKJ, Johnson AN, Clockston R, Oselinsky K, Lundeberg PJ, Rand K, & Graham DJ (2021). Intersectional health disparities: The relationships between sex, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation and depressive symptoms. Psychology & Sexuality, 1–22. 10.1080/19419899.2021.1982756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, West BT, & Boyd CJ (2010). Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction, 105(12), 2130–2140. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, Wilsnack S, Martin K, Matthews A, & Johnson T (2021). Alcohol use among sexual minority women: Methods used and lessons learned in the 20-Year Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women Study. The International Journal of Alcohol and Drug Research, 9(1), 30–42. 10.7895/ijadr.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TP, Hughes TL, Cho YI, Wilsnack SC, Aranda F, & Szalacha LA (2013). Hazardous drinking, depression, and anxiety among sexual-minority women: self-mediation or impaired functioning? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 74(4), 565–575. 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimerling R, Ouimette P, Prins A, Nisco P, Lawler C, Cronkite R, & Moos RH (2006). Brief report: Utility of a short screening scale for DSM-IV PTSD in primary care. J Gen Intern Med, 21(1), 65–7. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA, & Wisniewski N (1987). The scope of rape: incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55(2), 162–170. 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JA, Hequembourg A, Testa M, & VanZile-Tamsen C (2007). Unique aspects of adolescent sexual victimization experiences. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(4), 331–343. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00383.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SL, Fisher BS, Warner TD, Krebs CP, & Lindquist CH (2011). Women’s sexual orientations and their experiences of sexual assault before and during university. Women’s Health Issues, 21(3), 199–205. 10.1016/j.whi.2010.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Schwartz S, & Frost DM (2008). Social patterning of stress and coping: Does disadvantaged social statuses confer more stress and fewer coping resources?. Social Science & Medicine, 67(3), 368–379. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, Rosario M, Corliss HL, Koenen KC, & Austin SB (2011). Childhood gender nonconformity: A risk indicator for childhood abuse and posttraumatic stress in youth. Pediatrics, 129(3), 410–417. 10.1542/peds.2011-1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JH, Croughan J, & Ratfcliff KS (1981). The NIMH diagnostic interview schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry, 38(4), 381–389. 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurvinsdottir R, & Ullman SE (2016). Sexual orientation, race, and trauma as predictors of sexual assault recovery. Journal of Family Violence, 31(7), 913–921. 10.1007/s10896-015-9793-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Chen Y, Singh A, Okereke OI, & Kubzansky LD (2016). Psychiatric, Psychological, and Social Determinants of Health in the Nurses’ Health Study Cohorts. American Journal of Public Health, 106(9), 1644–1649. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, & Ray CM (2021). Risk and protective factors for mental health outcomes among sexual minority and heterosexual college women and men. Journal of American College Health, 1–10. 10.1080/07448481.2021.1904955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ML, Chen J, & Breiding MJ (2010). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey (NISVS): 2010 findings on victimization by sexual orientation. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack SC, Vogeltanz ND, Klassen AD, & Harris TR (1997). Childhood sexual abuse and women’s substance abuse: National survey findings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 58(3), 264–271. 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt GE (1985). The sexual abuse of Afro-American and white-American women in childhood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 9, 507–519. 10.1016/0145-2134(85)90060-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H (2013). Strengths-based approach for mental health recovery. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 7(2), 5–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, & Farley GK (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]