Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal motor neuron disease typically leading to death within 5 years from symptom onset. ALS familial forms are associated with mutations in several genes, including Superoxide Dismutase 1 (SOD1) and Fused in Sarcoma (FUS). Although genes linked to ALS participate in disparate biological processes, ALS genetic variants largely trigger shared pathogenic events such as oxidative stress, protein aggregation and defects in RNA processing. Moreover, ALS patients show systemic hypermetabolism that leads to increased energy expenditure at rest and thus weight loss during the disease course.1 ALS hypermetabolic phenotype and weight loss have been extensively characterized in mice bearing the G93A substitution in SOD1 protein (SOD1-G93A), which exhibit skeletal-muscle metabolic reprogramming before disease onset.2,3

Only limited attention has been dedicated to the involvement of thermogenic adipocytes in ALS dysmetabolism. Differently from white adipose tissue (WAT), which stores energetic fuels into triglycerides and contributes to whole-body energetic homeostasis, brown adipose tissue (BAT) promotes adaptive thermogenesis by dissipating electrochemical proton gradient to produce heat through the mitochondrial uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1). Moreover, the third type of fat cells known as “beige” adipocytes and localized within WAT up-regulates UCP1 in response to environmental cues, thus developing a brown-like thermoregulatory behaviour in a process defined as “browning”.4

This study aimed to highlight whether BAT activation and/or the occurrence of brown-like adipocytes within WAT are events associated with weight loss in ALS mouse models.

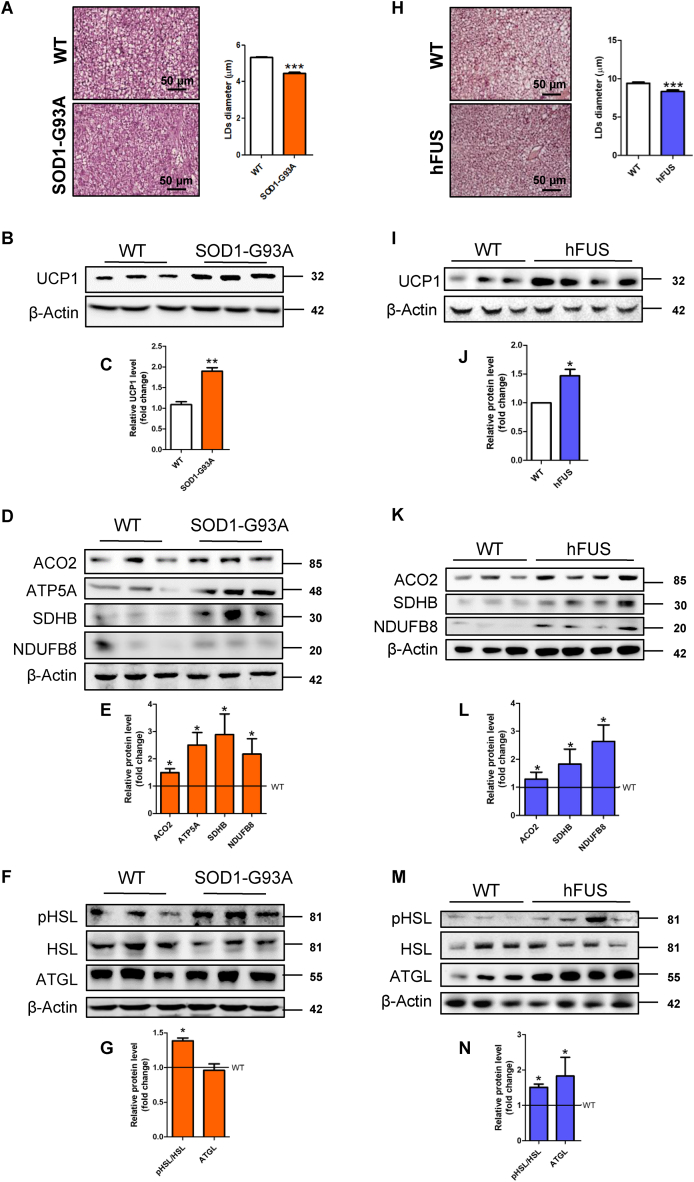

Starting from symptomatic SOD1-G93A mice (20–22 weeks of age) that manifest the decrement in body weight (Fig. S1A), we demonstrated the activation of BAT in terms of decreased diameter of lipid droplets (Fig. 1A) and upregulation of the BAT-specific markers UCP1 and PRDM16 (Fig. 1B, C; Fig. S1B). Furthermore, the reduced area of white adipocytes (Fig. S1C) and the upregulation of UCP1 protein in WAT depots (Fig. S1D, E) also revealed activation of the browning process in symptomatic SOD1-G93A mice.

Figure 1.

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) of symptomatic SOD1-G93A and hFUS mice is characterized by augmented lipolysis and mitochondrial uncoupling. (A) Representative images of BAT from SOD1-G93A mice after staining with H&E (n = 3 in each group). Scale bars, 50 μm. The bar graph shows lipid droplets (LDs) diameter measured in at least 3 fields for each image through ImageJ (∗∗∗ P < 0.001 vs. WT). (B) Western blot and (C) densitometric analyses of UCP1 levels in BAT. β-Actin was used as loading control. Data are shown as fold change relative to a WT sample (∗∗ P < 0.01 vs. WT). (D) Western blot and (E) densitometric analyses of ACO2, ATP5A, SDHB, NDUFB8 levels in BAT. β-Actin was used as loading control. Data are shown as fold change (∗ P < 0.05 vs. WT). (F) Western blot and (G) densitometric analyses of pHSL Ser563, HSL and ATGL levels in BAT. β-Actin was used as loading control. Data are shown as fold change (∗ P < 0.05 vs. WT). (H) Representative images of BAT from hFUS mice after staining with H&E (n = 3 in each group). Scale bars, 50 μm. The bar graph shows LDs diameter measured at least in 3 fields for each image through ImageJ (∗∗∗ P < 0.001 vs. WT). (I) Western blot analysis and (J) densitometric analysis of UCP1 levels in BAT. β-Actin was used as loading control. Data are shown as fold change (∗ P < 0.05 vs. WT). (K) Western blot analysis and (L) densitometric analysis of ACO2, SDHB, NDUFB8 levels in BAT. β-Actin was used as loading control. Data are shown as fold change (∗ P < 0.05 vs. WT). (M) Western blot and (N) densitometric analyses of pHSL Ser563, HSL and ATGL levels in BAT. β-Actin was used as loading control. Data are shown as fold change (∗ P < 0.05 vs. WT).

The upregulation of the proteins ACO2, SDHB, NDUFB8, and ATP5A involved in the Krebs cycle and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) (Fig. 1D, E), the increase in NAD+/NADH ratio (Fig. S2A), and the decrease in ATP content (Fig. S2B) were compatible with augmented uncoupling respiration of BAT in ALS mice. This result was also corroborated by the reduction of triphosphate and diphosphate forms of purine nucleotides (Fig. S2B), which are endogenous inhibitors of UCP1 activity.

Oxidative metabolism of active BAT is typically sustained by multiple energetic fuels, primarily fatty acids. The stimulatory phosphorylation of the lipolytic enzyme HSL (Fig. 1F, G) and the upregulation of genes involved in lipid catabolism (Fig. S2C) demonstrated that intracellular lipids were consumed in BAT of symptomatic SOD1-G93A mice. No change was instead evidenced for plasma membrane transporters of extracellular fatty acids (Fig. S2D). The dephosphorylation of the lipogenic enzyme ACC1 (Fig. S3A, B) and the increased concentration of its product malonyl-CoA (Fig. S3C) demonstrated that lipogenesis is coupled to lipolysis to restore lipid droplets during BAT activation. Moreover, glucose-derived pyruvate was more efficiently converted into acetyl-CoA inside mitochondria, as the PDH complex was less phosphorylated/inhibited in SOD1-G93A mice (Fig. S3A, B). Finally, the decreased levels of several amino acids (Fig. S3D), including branched-chain amino acids, suggested that their metabolism is also altered in BAT of SOD1-G93A mice.

We then analysed asymptomatic SOD1-G93A mice (10–12 weeks) and observed that BAT activation/WAT browning were also manifested before weight loss. In fact, UCP1 and PRDM16 were significantly upregulated (Fig. S4A–C) even though no apparent changes were detectable in BAT histological analyses (Fig. S4D). As concerns WAT, the area of white adipocytes was reduced (Fig. S4E) and UCP1 was significantly overexpressed (Fig. S4F, G).

The upregulation of UCP1 in BAT of asymptomatic SOD1-G93A mice was associated with a slight increase of ACO2 and several OXPHOS subunits (Fig. S5A, B) as well as activation of HSL lipolytic cascade (Fig. S5C, D). Differently from symptomatic SOD1-G93A mice, we revealed increased levels of plasma membrane fatty acid transporters (Fig. S5E) and no difference in the phosphorylation state of both ACC1 and PDH (Fig. S5F, G) in asymptomatic mice.

By analysing mice overexpressing human WT FUS (hFUS), we corroborated the activation of BAT in another ALS mouse model. As observed for SOD1-G93A mice, symptomatic hFUS mice exhibiting weight loss (Fig. S6) also showed a decrease in lipid droplet diameter (Fig. 1H) and an increase in UCP1 levels (Fig. 1I, J). This was associated with the increase of OXPHOS subunits, ACO2 expression (Fig. 1K, L) and activation of the lipolytic cascade in terms of HSL phosphorylation and ATGL upregulation (Fig. 1M, N).

Collectively, our data demonstrated that the increase of UCP1 expression in BAT of SOD1-G93A mice is already evident before the manifestation of disease symptoms and maintained in symptomatic mice. Analogously, the browning process in WAT depots occurred both before and after weight loss and motor symptoms. These results well agree with the evidence that bodyweight decline in ALS patients frequently occurs decades before clinical manifestation of ALS.1,2

The activation of lipolysis and β-oxidation in BAT of symptomatic and asymptomatic mice indicates that lipid droplets are constantly degraded to sustain oxidative metabolism. The dephosphorylation/activation of PD in ALS symptomatic mice indicates that glucose oxidation boosts BAT uncoupling activity together with lipid catabolism when weight loss is manifested. Moreover, branched-chain amino acids may be additional fuels that symptomatic mice use to ignite BAT thermogenesis.

Since the hFUS mice showed the same phenotype as SOD1-G93A mice, we can hypothesize that BAT activation in ALS mouse models is a consequence of the pathology. The dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system described in ALS5 might have a role as BAT is innervated by the sympathetic, parasympathetic and sensory nerve fibers. More specifically, the neuronal control of BAT activation is mediated by the sympathetic nervous system, which activates lipolysis and mitochondrial uncoupling via norepinephrine-mediated β-adrenergic stimulation.4 Another intriguing hypothesis is that muscle-derived cytokines (myokines) that alter BAT physiology are released during muscle metabolic reprogramming and/or denervation promoting thermogenesis in ALS.

In conclusion, the activation of thermogenic adipocytes is likely to contribute to ALS hypermetabolic phenotype and/or weight loss in ALS mouse models. As BAT activation can also lead to energy expenditure in humans, the combination of drugs inhibiting BAT-mediated dissipation with diet plans that avoid weight loss represents an exciting opportunity to counteract energy expenditure in people affected by ALS and ameliorate their quality of life.

Author contributions

F. Ciccarone and M.R. Ciriolo designed the experiments and interpreted the results; S. Castelli performed most of the experiments, analysed data and prepared the figures; F. Ciccarone wrote the paper; M.R. Ciriolo edited the manuscript; S. Scaricamazza and A. Ferri were involved in SOD1-G93A mouse colony management including breeding, genotyping and evaluation of symptoms during disease progression; S. Apolloni and N. D'Ambrosi were involved in hFUS mouse colony management including breeding and evaluation of symptoms; S. Bernardini performed the histological analysis on adipose tissue; G. Lazzarino and R. Mangione performed HPLC experiments. All authors read and approved the final article.

Conflict of interests

Authors declare no conflict of interests.

Funding

This work was supported by Beyond Borders 2019 (No. E84I20000580005) from Tor Vergata University and MIUR/PRIN 2017 (No. 2017A5TXC3) (MRC).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chongqing Medical University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gendis.2022.04.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Dupuis L., Pradat P.F., Ludolph A.C., Loeffler J.P. Energy metabolism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scaricamazza S., Salvatori I., Giacovazzo G., et al. Skeletal-muscle metabolic reprogramming in ALS-SOD1G93A mice predates disease onset and is a promising therapeutic target. iScience. 2020;23(5):101087. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steyn F.J., Li R., Kirk S.E., et al. Altered skeletal muscle glucose-fatty acid flux in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Commun. 2020;2(2):fcaa154. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcaa154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zwick R.K., Guerrero-Juarez C.F., Horsley V., Plikus M.V. Anatomical, physiological, and functional diversity of adipose tissue. Cell Metabol. 2018;27(1):68–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vucic S. Sensory and autonomic nervous system dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2017;43(2):99–101. doi: 10.1111/nan.12336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.