Abstract

Background

Breast cancer brain metastasis (BCBM) is a growing therapeutic challenge and clinical concern. Stromal cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are crucial factors in the modulation of tumorigeneses and metastases. Herein, we investigated the relationship between the expression of stromal CAF markers in metastatic sites, platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta (PDGFR-β), and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and the clinical and prognostic variables in BCBM patients.

Methods

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of the stromal expression of PDGFR-β and α-SMA was performed on 50 cases of surgically resected BCBM. The expression of the CAF markers was analyzed in the context of clinico-pathological characteristics.

Results

Expression of PDGFR-β and α-SMA was lower in the triple-negative (TN) subtype than in other molecular subtypes (p = 0.073 and p = 0.016, respectively). And their expressions were related to a specific pattern of CAF distribution (PDGFR-β, p = 0.009; α-SMA, p = 0.043) and BM solidity (p = 0.009 and p = 0.002, respectively). High PDGFR-β expression was significantly related to longer recurrence-free survival (RFS) (p = 0.011). TN molecular subtype and PDGFR-β expression were independent prognostic factors of recurrence-free survival (p = 0.029 and p = 0.030, respectively) and TN molecular subtype was an independent prognostic factor of overall survival (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Expression of PDGFR-β in the stroma of BM was associated with RFS in BCBM patients, and the clinical implication was uniquely linked to the low expression of PDGFR-β and α-SMA in the aggressive form of the TN subtype.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-023-10957-5.

Keywords: Brain metastasis, Cancer-associated fibroblasts, α-smooth muscle actin, Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β, Prognosis, Triple negative breast neoplasms

Background

Breast cancer (BC) is one of the most common malignancies in women and the second leading cause of metastases in the brain [1]. BC brain metastases (BCBM) have a poor prognosis and restricted therapeutic response due to the minimal blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration of chemotherapeutic and targeted agents [2, 3]. Existing conventional therapies including surgical resection, whole-brain radiation therapy (WBRT), stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), targeted drugs, and immune checkpoint inhibitors are seldom curative in BM [4]. Consequently, the median survival of BM patients is about a year after diagnosis [5].

The characteristic of cancer metastases and progression is determined by the reciprocal and dynamic interactions between the cancer cells and stromal cells as part of the tumor microenvironment (TME) in the host tissue; this interaction supports in cancer cell survival, invasion, and distant metastasis [6, 7]. TME, particularly the stromal components, is a vital and critical part of the contemporary development of BC therapeutic strategies [8]. Stromal cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), are considered the most vital TME elements and are emerging therapeutic targets for BCBM. Although CAF populations are presumed to be heterogeneous in TME and have been known to promote tumorigenesis and metastasis, their precise functions in systemic or metastatic cancers are not fully elucidated [9].

Previous studies have shown that various CAFs subtypes are pro- or anti-tumorigenic, with their biological actions reliant on their specific tumor conditions [10, 11]. Specific CAF subtypes may affect tumor growth and/or inhibition, possibly according to the primary tumor types and locations [11]. The depletion of α-SMA in the tumor stroma prompts immunosuppression and cancer progression with shortened survival in pancreatic cancer patients [12]. A high expression of α-SMA is associated with longer overall survival (OS) after tumor resection in hepatocellular carcinoma and pancreatic cancer [13]. Besides, the abundant expression of stromal fibroblast activation protein (FAP) is also related to longer OS and disease-free survival (DFS) in patients with invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast [14]. These studies, therefore, argued that stromal CAFs may slow the progression of the tumor and thus increase the patient’s survival.

Numerous CAF markers have been used in clinical and biological studies of CAFs in human cancer so far [15], but the current study was conducted with a focus on PDGFR-β and α-SMA. We investigated the expression level of these markers of the stromal CAFs in BCBMs and evaluated he correlation of their expressions with clinico-pathological variables. In addition, we analyzed the recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) rates according to the expression levels of CAF markers and clinico-pathological variables.

Methods

The study subjects and clinico-radiological data

The study included 50 samples from patients with BCBM who underwent craniotomy and tumor removal at the Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital between 2004 and 2020. Only 18 out of 50 cases had a matched primary tumor sample. All the specimens were obtained from the archives of Pathology department. Experienced pathologists examined and assessed the selection of the slides and pathological parameters (SSK and KHL).

To define the clinical and radiological variables of the enrolled BCBM patients, we evaluated their clinical data at the time of the BM diagnosis. For this study, we analyzed clinical and radiological variables that have been established to be associated with brain metastasis (BM), based on our previous investigations [16, 17]. Clinical variables include age, presenting symptoms & neurological signs, the time interval from BC diagnosis to BM, the molecular subtype of BC, Karnofsky performance score (KPS), treatment modality after BM resection and date of death. Based on the initial and follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans, we analyzed the radiological variables, including location, size and tumor nature (solid vs. cystic or mixed) of resected BM, the multiplicity of BM, perilesional edema, and resection degree. The presence of extracranial metastasis was also evaluated using positron emission tomography (PET) scan or systemic CT or MRI. RFS in cases with brain tumor was generally calculated from the date of surgery to the date of local recurrence (new lesion on operation site in the cases with gross total resection, or progression in the cases with non-gross total resection). For statistical significance in survival rate, however, RFS was calculated only in 38 cases, excluding 12 cases in which partial to subtotal resection was performed. OS was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of recurrence or death, or the last follow-up visit of a living patient. Written informed consent for the use of clinical information and pathological specimens was obtained from patients or their legal surrogates. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital (CNUHH-2019–218).

Immunohistochemistry for BM samples

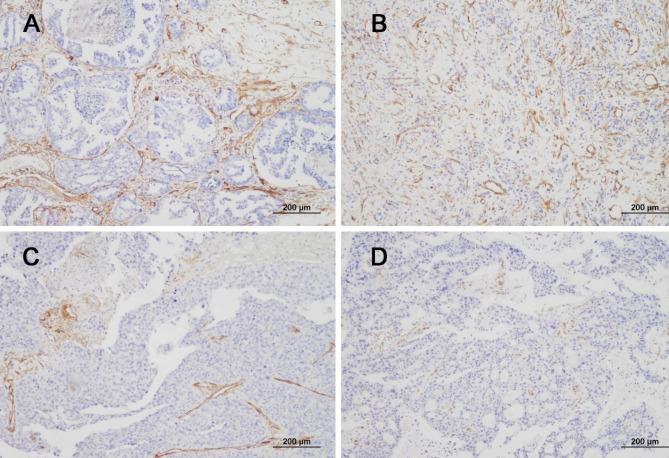

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed as previously described [18]. Tissue Sect. (3 μm thick) were subjected to IHC using a Bond-max autostainer (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). The following antibodies were used: PDGFR-β (1:400 dilution; catalog no. ab32570; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and α-SMA (1:100 dilution; catalog no. ab5694; Abcam). IHC slides were assessed by pathologists (SSK and KHL), who were blinded to the clinical details. The distribution of CAFs varied significantly according to the molecular subtype and could be grouped into three patterns (Fig. 1). Briefly, in pattern A, CAFs were located around medium-to-large tumor cell clusters. The CAFs in pattern B encased individual cancer cells or intermingled closely with small tumor nests. In pattern C, the CAFs were scarcely present in the tumor tissue. The scores of immunostaining in stromal CAFs were given according to the relative ratio of the area stained by the CAF markers to the area of the tumor cells (Fig. 1): 0, no staining; 1, ≤ 3%; 2, ≤ 10%; and 3 > 10%. Since PDGFR-β and α-SMA are well-known pericyte markers and tend to stain strongly in vascular structures, great care was taken to exclude vessels during the interpretation of the staining area. We assessed the expression levels of PDGFR-β and α-SMA and determined the optimal cut-off value to represent statistical significance by grouping scores of 0, 1, and 2 together and comparing them to a score of 3. Therefore, the cases with scores 0, 1, and 2 were categorized into a low expression group, and the cases with score 3 into a high expression group.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of CAF marker expression by pattern and score. (A) A representative case with a combination of high PDGFR-β expression and CAF pattern A was shown, and its molecular subtype was luminal A-like. (B) A representative case with a combination of high PDGFR-β expression and CAF pattern B was shown, and its molecular subtype was HER2-positive. (C) A representative case with a combination of low PDGFR-β expression and CAF pattern C was shown, and its molecular subtype was triple-negative. The triple negative type had a high proportion of low expression. (D) The case was composed of a combination of low PDGFR-β expression, CAF pattern 4, and luminal A subtype. In luminal-A type, the proportion of low expression was relatively low

Statistical analyses

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 23.0 software for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Comparisons between the expression of CAF markers and clinico-radiological variables were performed using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test as appropriate. The kappa value was obtained to show the concordance of expression between different CAF markers or in matched pair samples, and the Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to show the difference in expression level between groups. The effects of clinico-radiological variables and expression and patterns of CAF markers on RFS and OS were determined using the Kaplan–Meier method with log-rank tests. The cox regression model was used for multivariate analysis of patients’ survival. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Correlation between expressions of PDGFR-β/α-SMA in stromal CAFs and clinico-radiological characteristics of BCBM patients

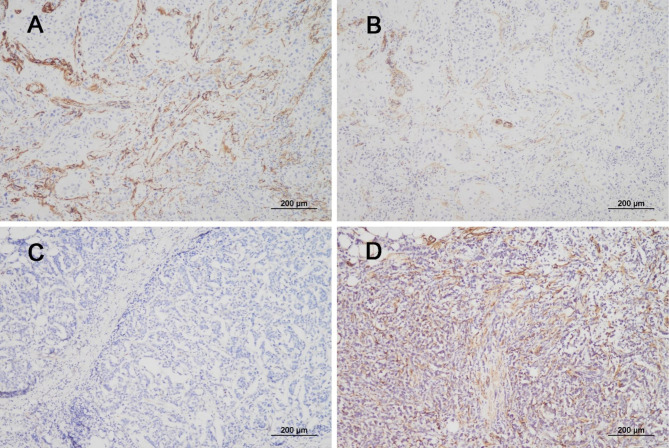

The clinico-radiological and pathological characteristics of the 50 cases of BCBM are summarized in Table 1. In molecular subtypes, 10 cases (20%) were luminal A, 6 cases (12%) luminal B, 19 cases (38%) HER2-positive, and 15 (30%) were TN subtypes. In IHC, PDGFR-β and α-SMA, characteristic biomarkers of CAFs, were specifically stained in the stromal portion, not in the tumor portion. The expression of PDGFR-β was scored as follows; score 1 in 11 cases, score 2 in 16 cases, and score 3 in 23 cases. In α-SMA, 9 cases were scored as 1, 18 cases as 2, and 23 cases as 3. In a comparison of the markers in the same case, the score of expression was consistent in the majority of BM cases and showed a moderate level of agreement (kappa value = 0.684) (Fig. 2A-B & Table 2). PDGFR-β and α-SMA expressions were similarly examined in 18 matched primary tumor samples out of 50 cases. Compared to BCBM samples, the expression intensity of PDGFR-β and α-SMA was relatively high in the primary tumor samples without statistical significance (p = 0.177 and 0.132, respectively), and the concordance was low (kappa value = 0.170 and 0.148, respectively) (Supplementary Tables 1–2). When comparing the expression of PDGFR-β and α-SMA in 18 cases of primary BC samples, the expression of the two markers showed no agreement (kappa value = 0.091) (Fig. 2C-D & Supplementary Table 3). It is generally known that a kappa value of 0.8 or more indicates a strong level of agreement, 0.6–0.79 indicates a moderate level, and 0.2 or less indicates no agreement [19].

Table 1.

Clinico-radiological and pathological features of the patients with BCBM

| Variable | No. | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | < 60 | 35 | 70% |

| ≥ 60 | 15 | 30% | |

| Sex | Female | 49 | 98% |

| Male | 1 | 2% | |

| Molecular type | Luminal A | 10 | 20% |

| Luminal B | 6 | 12% | |

| HER2 | 19 | 38% | |

| TN | 15 | 30% | |

| CAF pattern | Type A | 24 | 48% |

| Type B | 20 | 40% | |

| Type C | 6 | 12% | |

| PDGFR-β | Low | 27 | 54% |

| High | 23 | 46% | |

| α-SMA | Low | 27 | 54% |

| High | 23 | 46% | |

| Tumor location | Supratentorial | 37 | 74% |

| Infratentorial | 13 | 26% | |

| Extracranial Mets | Absent | 12 | 24% |

| Present | 38 | 76% | |

| BM symptom | Mild to moderate | 31 | 62% |

| Severe | 19 | 38% | |

| KPS | ≥ 80 | 32 | 64% |

| < 80 | 18 | 36% | |

| BM multiplicity | Single | 24 | 48% |

| Multiple | 26 | 52% | |

| BM development | Metachronous | 49 | 98% |

| Synchronous | 1 | 2% | |

| BM size | < 4 cm | 22 | 44% |

| ≥ 4 cm | 28 | 56% | |

| Peritumoral edema | Mild to moderate | 27 | 54% |

| Severe | 23 | 46% | |

| Tumor nature | Solid | 27 | 54% |

| Cystic or mixed | 23 | 46% | |

| Resection degree | Gross total | 38 | 76% |

| Partial to subtotal | 12 | 24% | |

| Postoperative RT/GKS | Absent | 16 | 32% |

| Present | 34 | 68% | |

BC, breast cancer; BM, brain metastasis; α-SMA, alpha-smooth muscle actin; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; GKS, gamma knife radiosurgery; KPS, Karnofsky performance score; Mets, metastasis; PDGFR-β, platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta; RT, radiation treatment; TN, triple negative

Fig. 2.

Comparison of PDGFR-β and α-SMA expression in the same case. In the same BM case, the expression of PDGFR-β (A) at score 3 and α-SMA (B) at score 2 was compared. Comparison of the two markers in 50 BM cases, showed a moderate level of agreement (kappa value = 0.684). The expression of PDGFR-β (C) at score 1 and α-SMA (D) at score 3 in the same primary BC was compared. The expression of the two markers showed no agreement in 18 primary BC samples (kappa value = 0.091)

Table 2.

Comparison of immunohistochemical expressions of PDGFR-β and α-SMA in stromal CAFs.

| α-SMA | Total | Kappa value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score 1 | Score 2 | Score 3 | ||||

| PDGFR-β | Score 1 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 11 | 0.684 |

| Score 2 | 1 | 12 | 3 | 16 | ||

| Score 3 | 0 | 3 | 20 | 23 | ||

| Total | 9 | 18 | 23 | 50 | ||

α-SMA, alpha-smooth muscle actin; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; PDGFR-β, platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta

The correlation between the expression of PDGFR-β and α-SMA and clinico-radiological variables in 50 enrolled patients is summarized in Table 3. Within the various clinico-radiological characteristics, the expression of these markers was correlated with molecular subtypes. In the aggressive TN subtype, the expression of PDGFR-β (p = 0.073) and α-SMA (p = 0.016) was significantly low compared with other molecular subtypes. High expression of these markers was related to a specific type B pattern of CAF distribution (p = 0.005 in PDGFR-β, p = 0.028 in α-SMA). Interestingly, the high expression of these markers was associated with the tumor with solid tumors (p = 0.009 in PDGFR-β, p = 0.001 in α-SMA). Collectively, PDGFR-β and α-SMA expressions were significantly related to the pattern of CAF distribution, molecular subtypes, and tumor nature of BM.

Table 3.

Correlation between expression of PDGFR-β/α-SMA and clinico-radiological variables in 50 patients with BCBM

| Variables | No. | PDGFR-β expression | p value | α-SMA expression | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Low | High | |||||

| Age (year) | < 60 | 35 | 20 (57%) | 15 (43%) | 0.496 | 20 (57%) | 15 (43%) | 0.496 |

| ≥ 60 | 15 | 7 (47%) | 8 (53%) | 7 (47%) | 8 (53%) | |||

| Sex | Female | 49 | 27 (55%) | 22 (45%) | 0.460 | 27 (55%) | 22 (45%) | 0.460 |

| Male | 1 | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | |||

| Molecular type | Non-TN | 35 | 16 (46%) | 19 (54%) | 0.073 | 15 (43%) | 20 (57%) | 0.016 |

| TN | 15 | 11 (73%) | 4 (27%) | 12 (80%) | 3 (20%) | |||

| CAF pattern | Type B | 20 | 6 (30%) | 14 (70%) | 0.005 | 7 (35%) | 13 (65%) | 0.028 |

| Other type | 30 | 21 (70%) | 9 (30%) | 20 (67%) | 10 (33%) | |||

| Tumor location | Supratentorial | 37 | 19 (51%) | 18 (49%) | 0.526 | 19 (51%) | 18 (49%) | 0.526 |

| Infratentorial | 13 | 8 (62%) | 5 (38%) | 8 (62%) | 5 (38%) | |||

| Extracranial Mets | Absent | 12 | 6 (50%) | 6 (50%) | 0.750 | 5 (42%) | 7 (58%) | 0.325 |

| Present | 38 | 21 (55%) | 17 (45%) | 22 (58%) | 16 (42%) | |||

| BM symptom | Mild to moderate | 31 | 17 (55%) | 14 (45%) | 0.879 | 17 (55%) | 14 (45%) | 0.879 |

| Severe | 19 | 10 (53%) | 9 (47%) | 10 (53%) | 9 (47%) | |||

| KPS | ≥ 80 | 32 | 19 (59%) | 13 (41%) | 0.309 | 19 (59%) | 13 (41%) | 0.309 |

| < 80 | 18 | 8 (44%) | 10 (56%) | 8 (44%) | 10 (56%) | |||

| BM multiplicity | Single | 24 | 13 (54%) | 11 (46%) | 0.982 | 11 (46%) | 13 (54%) | 0.266 |

| Multiple | 26 | 14 (54%) | 12 (46%) | 16 (62%) | 10 (38%) | |||

| BM development | Metachronous | 49 | 27 (55%) | 22 (45%) | 0.460 | 27 (55%) | 22 (45%) | 0.460 |

| Synchronous | 1 | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | |||

| BM size | < 4 cm | 22 | 12 (55%) | 10 (45%) | 0.945 | 11 (50%) | 11 (50%) | 0.615 |

| ≥ 4 cm | 28 | 15 (54%) | 13 (46%) | 16 (57%) | 12 (43%) | |||

| Peritumoral edema | Mild to moderate | 27 | 16 (59%) | 11 (41%) | 0.419 | 18 (67%) | 9 (33%) | 0.052 |

| Severe | 23 | 11 (48%) | 12 (52%) | 9 (39%) | 14 (61%) | |||

| Tumor nature | Solid | 27 | 10 (37%) | 17 (63%) | 0.009 | 9 (33%) | 18 (67%) | 0.001 |

| Cystic or mixed | 23 | 17 (74%) | 6 (26%) | 18 (78%) | 5 (22%) | |||

BC, breast cancer; BM, brain metastasis; α-SMA, alpha-smooth muscle actin; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; GKS, gamma knife radiosurgery; KPS, Karnofsky performance score; Mets, metastasis; PDGFR-β, platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta; RT, radiation treatment; TN, triple negative

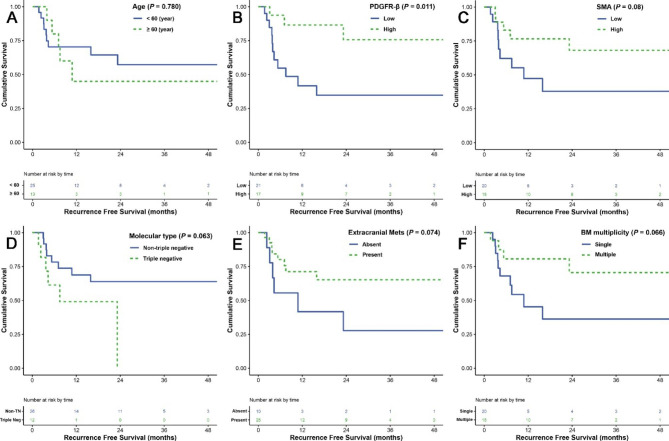

Prognostic significance of PDGFR-β/α-SMA in stromal CAFs and clinico-radiological characteristics concerning survival outcomes

We analyzed the RFS and OS of the patients based on the CAF-markers expression and clinico-pathological variables. As shown in Fig. 3 & Table 4, RFS analyses using the Kaplan-Meier estimator and log-rank test revealed that higher expression of PDGFR-β was significantly related to longer RFS (p = 0.011, 31.2 m in low expression vs. 50.1 m in the high expression). A similar trend was found in the analysis of α-SMA expression with marginal significance (p = 0.080, 28.3 m in low expression vs. 56.4 m in the high expression). As in presumption, the TN subtype was correlated with shorter RFS (13.5 m in TN subtype vs. 52.5 m in non-TN subtypes, p = 0.063). On multivariate analysis, high expression of PDGFR-β (p = 0.011, hazard ratio [HR] 0.228, 95% confidence index [CI] 0.060–0.868) and TN molecular subtype (p = 0.029, HR 4.202, 95% CI 1.158–15.256) were independent predictors of RFS.

Fig. 3.

Recurrence-free survival (RFS) analyses using the Kaplan-Meier estimator and log-rank test were performed according to age (A), PDGFR-β expression (B), α-SMA expression (C), molecular subtype of BCBM (D), presence of extracranial metastasis (E), and multiplicity of BM lesions (F)

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for recurrence-free survival (RFS) predictors in 38 patients with BCBM that were removed by gross total resection

| Characteristics | No. | Mean (months) | P-value (univariate) | P-value (multivariate) | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | < 60 | 25 | 48.5 | 0.780 | 0.275 | 1 | 0.571–7.164 |

| ≥ 60 | 13 | 31.8 | 2.023 | ||||

| Sex | Female | 37 | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Male | 1 | --- | |||||

| Molecular type | Non-TN | 26 | 52.5 | 0.063 | 0.029 | 1 | 1.158–15.256 |

| TN | 12 | 13.5 | 4.202 | ||||

| CAF pattern | Type B | 15 | 43.2 | 0.424 | 0.254 | 1 | 0.112–1.782 |

| Others | 23 | 41.8 | 0.447 | ||||

| PDGFR-β | Low | 21 | 31.2 | 0.011 | 0.030 | 1 | 0.060–0.868 |

| High | 17 | 50.1 | 0.228 | ||||

| α-SMA | Low | 20 | 28.3 | 0.080 | --- | ||

| High | 18 | 56.4 | |||||

| Tumor location | Supratentorial | 29 | 45.3 | 0.968 | --- | ||

| Infratentorial | 9 | 25.6 | |||||

| Extracranial Mets | Absent | 10 | 28.0 | 0.074 | 0.072 | 1 | 0.106–1.099 |

| Present | 28 | 44.0 | 0.341 | ||||

| BM symptom | Mild to moderate | 24 | 48.3 | 0.500 | --- | ||

| Severe | 14 | 33.4 | |||||

| KPS | ≥ 80 | 25 | 44.1 | 0.806 | --- | ||

| < 80 | 13 | 38.5 | |||||

| BM multiplicity | Single | 20 | 32.9 | 0.066 | --- | ||

| Multiple | 18 | 48.1 | |||||

| BM development | Metachronous | 37 | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Synchronous | 1 | --- | |||||

| BM size | < 4 cm | 19 | 39.0 | 0.428 | --- | ||

| ≥ 4 cm | 19 | 41.3 | |||||

| Peritumoral edema | Mild to moderate | 16 | 38.9 | 0.676 | --- | ||

| Severe | 22 | 43.7 | |||||

| Tumor nature | Solid | 23 | 45.1 | 0.919 | --- | ||

| Cystic or mixed | 15 | 38.6 | |||||

| Postoperative RT/GKS | Absent | 9 | 22.8 | 0.249 | --- | ||

| Present | 29 | 42.2 | |||||

BC, breast cancer; BM, brain metastasis; α-SMA, alpha-smooth muscle actin; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; GKS, gamma knife radiosurgery; KPS, Karnofsky performance score; Mets, metastasis; PDGFR-β, platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta; RT, radiation treatment; TN, triple negative

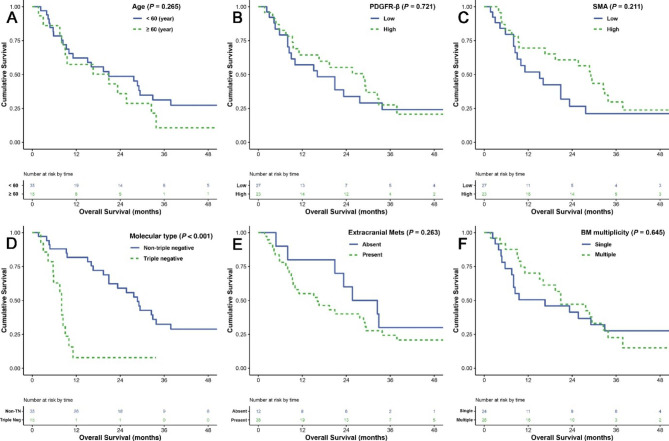

In OS analysis (Fig. 4; Table 5), only TN molecular subtype was related to significantly short OS period by univariate analysis (p < 0.001) and was also a significant predictor of shorter OS in BCBM patients by multivariate analysis (p < 0.001, HR 5.992, 95% CI 2.513–14.285). The expression of PDGFR-β or α-SMA was not significantly correlated with OS. In a view of CAF marker expression, the overall finding shows that low expression of PDGFR-β and α-SMA in stromal CAFs could be considered as a predictor of local recurrence in resected BM.

Fig. 4.

Overall survival (OS) analyses using the Kaplan-Meier estimator and log-rank test were performed according to age (A), PDGFR-β expression (B), α-SMA expression (C), molecular subtype of BCBM (D), presence of extracranial metastasis (E), and multiplicity of BM lesions (F)

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for overall survival (OS) predictors in 50 patients with BCBM

| Characteristics | No. | Mean (months) | P-value (univariate) | P-value (multivariate) | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | < 60 | 35 | 31.5 | 0.265 | 0.054 | 1 | 0.987–4.162 |

| ≥ 60 | 15 | 21.6 | 2.027 | ||||

| Sex | Female | 49 | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Male | 1 | --- | |||||

| Molecular type | Non-TN | 35 | 35.0 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 1 | 2.513–14.285 |

| TN | 15 | 9.1 | 5.992 | ||||

| CAF pattern | Type B | 20 | 29.3 | 0.498 | 0.238 | 1 | 0.306–1.343 |

| Others | 30 | 25.9 | 0.641 | ||||

| PDGFR-β | Low | 27 | 27.4 | 0.721 | --- | ||

| High | 23 | 27.8 | |||||

| α-SMA | Low | 27 | 22.3 | 0.211 | --- | ||

| High | 23 | 32.6 | |||||

| Tumor location | Supratentorial | 37 | 27.6 | 0.607 | --- | ||

| Infratentorial | 13 | 28.2 | |||||

| Extracranial Mets | Absent | 12 | 38.3 | 0.263 | --- | ||

| Present | 38 | 24.4 | |||||

| BM symptom | Mild to moderate | 31 | 30.4 | 0.457 | --- | ||

| Severe | 19 | 24.6 | |||||

| KPS | ≥ 80 | 32 | 30.6 | 0.454 | --- | ||

| < 80 | 18 | 23.6 | |||||

| BM multiplicity | Single | 24 | 26.9 | 0.645 | --- | ||

| Multiple | 26 | 26.5 | |||||

| BM development | Metachronous | 49 | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Synchronous | 1 | --- | |||||

| BM size | < 4 cm | 22 | 31.2 | 0.643 | 0.427 | 1 | 0.639–2.879 |

| ≥ 4 cm | 28 | 25.5 | 1.357 | ||||

| Peritumoral edema | Mild to moderate | 27 | 26.1 | 0.791 | --- | ||

| Severe | 23 | 30.7 | |||||

| Tumor nature | Solid | 27 | 33.7 | 0.197 | --- | ||

| Cystic or mixed | 23 | 22.1 | |||||

| Resection degree | Partial to subtotal | 12 | 20.8 | 0.442 | --- | ||

| Gross total | 38 | 29.8 | |||||

| Postoperative RT/GKS | Absent | 16 | 19.2 | 0.153 | 0.111 | 1 | 0.265–1.146 |

| Present | 34 | 31.8 | 0.551 | ||||

BC; breast cancer, BM; brain metastasis, α-SMA; alpha-smooth muscle actin, CAF; cancer-associated fibroblast, GKS; gamma knife radiosurgery, KPS; Karnofsky performance score, Mets; metastasis, PDGFR-β; platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta, RT; radiation treatment, TN; triple negative

Discussion

Metastases remain a leading cause of drug resistance and tumor-induced death in BC patients [20]. Therefore, even though advanced chemotherapy based on molecular biology have improved patient survival, the development and trial of new treatment strategy have been continued with an aim of overcoming mechanisms of drug resistance and tumor relapse [21]. The TME plays a fundamental role in tumor development and progression. The study of TME might provide an insight into the novel therapeutic strategies. The fibroblasts are the most abundant cells in TME of solid tumors, such as BC, and are considered the most important elements in TME [22]. Some studies have investigated the role of CAFs in the primary site for tumor progression and distance metastases in BC [23–26]. Among the various CAF markers studied in BC [15], PDGFR-β and α-SMA were found to be important markers dividing the subpopulation of CAF. In particular, it has been reported that PDGFR-β plays an important role in identifying vascular CAF and its origin [27]. It has been reported that α-SMA can be used as an important marker for the subpopulation of CAFs associated with immune evasion of BC [28]. In addition, PDGFR-β was also identified as a marker of CAF, which plays an important role in forming the immunosuppressive TME of BC [29]. However, several studies have been conducted on PDGFR-β and α-SMA as CAF markers in the primary BC, but few studies have been conducted on PDGFR-β and α-SMA in BCBM. The present study aimed to investigate the clinical influence of metastatic site CAFs, especially with high expression of PDGFR-β/α-SMA, on clinical characteristics and prognosis of BCBM patients.

As CAF profiles are modified by reciprocal interaction with cancer cells, each CAFs might express various characteristics in correlation with different features of cancer cells [30]. Our results disclosed differential expression of PDGFR-β and α-SMA in the stroma of the metastatic site according to the molecular subtype of BC. Specifically, the expression of PDGFR-β was relatively low in the TN type. Our study is in line with a previous study which reported that low PDGFR-β expression in the primary site was more likely to be observed in the TN type [31]. Survival rates of BC patients were affected by the molecular subtypes of BCBM, the same as our data [32]. Furthermore, we observed that a higher expression of PDGFR-β or α-SMA indicated a good prognosis, particularly for RFS of patients with BCBM. CAF-related proteins also play an intrinsic role in tumor progression or suppression [33]. Some studies have supported that increased CAF protein subset in the TME tends to prolong the survival of cancer patients [12, 14]. We supposed that one of the heterogeneous CAFs subtypes, especially with high expression of PDGFR-β/α-SMA in BCBM may repress recurrence of tumor in the resection area and was sparsely related with TN, the most aggressive cancer cell subtype. However, regarding OS, the expression of the two markers had no statistical significance, and rather, the survival rate tended to be somewhat longer in the high expression groups. It is presumed that there are multiple factors for the different trends of RFS and OS in relation to the expression of these markers. Other than the fact that the TN molecular subtype acts as a very strong factor in determining the survival rate of BC patients, it is presumed that this may be the result of a complex action of various factors constituting the TME. The definite role of CAF components with regard to the survival rates of BC patients needs to be clarified in the future studies from a larger cohort of patients.

Usually, PDGFR-β and α-SMA are expressed in the stromal fibroblast and help in tissue remodeling, collagen turnover, and the wound healing process [34, 35]. Particularly, the activation and proliferation of fibroblast and production of ECM elements, known as a desmoplastic reaction, represents aspects of cancer progression and clinical outcomes in BC [24]. In the present study, there was a significant correlation between tumor nature (solid or cyst) and the expression of PDGFR-β/α-SMA. The expression of PDGFR-β/α-SMA in BCBM may also be interrelated with desmoplastic reactions. Even more, altered mechanical features of the TME such as ECM stiffness cause fibrosis by developing mechano-activation of fibroblasts. Therefore, it implies that differential expression of PDGFR-β/α-SMA according to tumor natures is correlated with desmoplastic features of BC and different mechanical stress of TME, regardless of the prognosis [36].

Previous studies have classified CAFs subtypes according to morphologic characteristics or molecular profiles [29, 30]. In the present study, the distribution of CAFs varied according to morphologic differences and could be grouped into three patterns (A, B, C). The pattern B type’s CAFs encased individual cancer cells or intermingled closely with small tumor nests. In CAFs in pattern B types, the expression levels of PDGFR-β and α-SMA were relatively high. The morphologic pattern is often related to the molecular profile and further to the functional aspect. However, unlike the correlation between the expression of PDGFR-β/α-SMA and tumor progression, there was no significant connection between our morphologic subtypes and patient clinical features. Therefore, a more detailed and suitable morphologic classification of CAFs is required for a more cost-effective prediction of prognosis with simple tissue analysis.

It is hard to anticipate the prognosis of patients with BCBM, although several prognostic factors have been suggested, which are associated with poor prognosis. As age, KPS, tumor subtypes, extracranial metastasis, and the number of BM are associated with survival in patients with BCBM, these factors were used to identify patients with good or bad prognosis [37, 38]. However, the above mentioned factors did not show a significant association with poor prognosis in the present study, except for tumor subtypes. Those factors only showed a tendency to relate to RFS, and PDGFR-β/α-SMA also showed a tendency to a similar degree. There is a low possibility for PDGFR-β/α-SMA to be a strong prognostic biomarker, further large-scale studies should verify PDGFR-β/α-SMA as feasible biomarkers to help ameliorate predicting the patient’s prognosis with BCBM. Because this was a retrospective study with a relatively small number of patients, there may be a possibility of selection bias. In addition, this study was a simple clinico-radiological and pathological investigation using only two CAF markers. To determine the exact role of CAFs for patients with BM from BC, a further prospective study with a large sample size and more detailed information on various CAF markers is needed.

Conclusions

Our study showed different expressions levels of PDGFR-β and α-SMA in stromal CAFs of BMs according to molecular subtypes of BC. The expression of the markers was lower in TN patients, the most aggressive molecular subtype, compared to other Luminal or HER2+ BC patients. Besides, this study investigated the correlation between stromal CAFs with high PDGFR-β/α-SMA expression and favorable prognosis of BCBM patients. More aggressive BC could be capable of metastasis to the brain, and recurrence after surgical resection, with CAFs subtype with low PDGFR-β/α-SMA expression. The present study aimed to show the clinical influence of metastatic site CAFs, in connection with biomarkers, PDGFR-β and α-SMA. Owing to the limitations of this study, further research on the exact role of CAFs is needed to provide an insight into the development of new therapeutic strategies for BCBM patients with a dismal prognosis.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The English in this document has been checked by at least two professional editors, both native speakers of English. For a certificate, please see: http://www.textcheck.com/certificate/FreTPA.

Abbreviations

- α-SMA

Alpha-smooth muscle actin

- BC

Breast cancer

- BM

Brain metastasis

- CAF

Cancer-associated fibroblast

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- PDGFR-β

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

Authors’ contributions

KHL and KSM designed this study. MRA, YJK, KHL, and KSM drafted the manuscript. MRA, EJA, YJK, MGN, KHL, SMAS, and KSM performed data analysis. YJK and TKL collected clinical data. SSK and KHL carried out a pathological examination. KHL and KSM carried out the statistical analysis. MGN, SSK, SMAS, and TKL assisted with the manuscript preparation and data analysis. EJA, KHL, SMAS, KSM drafted the revised manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Minist (2022R1A2C1011889 and 2020R1A5A2031185 for KHL, 2020R1C1C1007832 for KSM) and by Chonnam National University Hospital Biomedical Research Institute (HCRI21001 & HCRI21005 for KSM & KHL). There was no role of the funding bodies in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital (CNUHH-2019-218). Written informed consent to use clinical data & pathological samples was obtained from patients or their legal surrogates. All experiments were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 and its later amendments.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Co-first authors

Contributor Information

Kyung-Hwa Lee, Email: mdkaylee@jnu.ac.kr.

Kyung-Sub Moon, Email: moonks@chonnam.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Sperduto PW, Mesko S, Li J, Cagney D, Aizer A, Lin NU, et al. Estrogen/progesterone receptor and HER2 discordance between primary tumor and brain metastases in breast cancer and its effect on treatment and survival. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22(9):1359–67. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noaa025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fares J, Kanojia D, Cordero A, Rashidi A, Miska J, Schwartz CW, et al. Current state of clinical trials in breast cancer brain metastases. Neurooncol Pract. 2019;6(5):392–401. doi: 10.1093/nop/npz003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanojia D, Panek WK, Cordero A, Fares J, Xiao A, Savchuk S, et al. BET inhibition increases βIII-tubulin expression and sensitizes metastatic breast cancer in the brain to vinorelbine. Sci Transl Med. 2020;26:12558. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aax2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moravan MJ, Fecci PE, Anders CK, Clarke JM, Salama AKS, Adamson JD, et al. Current multidisciplinary management of brain metastases. Cancer. 2020;126(7):1390–406. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arvold ND, Lee EQ, Mehta MP, Margolin K, Alexander BM, Lin NU, et al. Updates in the management of brain metastases. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(8):1043–65. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson NM, Simon MC. The tumor microenvironment. Curr Biol. 2020;30(16):R921–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fares J, Fares MY, Khachfe HH, Salhab HA, Fares Y. Molecular principles of metastasis: a hallmark of cancer revisited. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):28. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0134-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salimifard S, Masjedi A, Hojjat-Farsangi M, Ghalamfarsa G, Irandoust M, Azizi G, et al. Cancer associated fibroblasts as novel promising therapeutic targets in breast cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2020;216(5):152915. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2020.152915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeBleu VS, Kalluri R. A peek into cancer-associated fibroblasts: origins, functions and translational impact. Dis Model Mch. 2018;11(4):dmm029447. doi: 10.1242/dmm.029447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bu L, Baba H, Yoshida N, Miyake K, Yasuda T, Uchihara T, Tan P, Ishimoto T. Biological heterogeneity and versatility of cancer-associated fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment. Oncogene. 2019;38(25):4887–901. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0765-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gieniec KA, Butler LM, Worthley DL, Woods SL. Cancer-associated fibroblasts-heroes or villains? Br J Cancer. 2019;121(4):293–302. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0509-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Özdemir BC, Pentcheva-Hoang T, Carstens JL, Zheng X, Wu CC, Simpson TR, et al. Depletion of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and fibrosis induces immunosuppression and accelerates pancreas cancer with reduced survival. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(6):719–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang WQ, Liu L, Xu HX, Luo GP, Chen T, Wu CT, et al. Intratumoral α-SMA enhances the prognostic potency of CD34 associated with maintenance of microvessel integrity in hepatocellular carcinoma and pancreatic cancer. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e71189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ariga N, Sato E, Ohuchi N, Nagura H, Ohtani H. Stromal expression of fibroblast activation protein/seprase, a cell membrane serine proteinase and gelatinase, is associated with longer survival in patients with invasive ductal carcinoma of breast. Int J Cancer. 2001;95(1):67–72. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010120)95:1<67::AID-IJC1012>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, McAndrews KM, Kalluri R. Clinical and therapeutic relevance of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(12):792–804. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00546-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akanda MR, Ahn EJ, Kim YJ, Salam SMA, Noh MG, Kim SS, et al. Different expression and clinical implications of Cancer-Associated Fibroblast (CAF) markers in Brain Metastases. J Cancer. 2023;14(3):464–79. doi: 10.7150/jca.80115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park JY, Moon KS, Lee KH, Lim SH, Jang WY, Lee H, et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery for elderly patients with brain metastases: evaluation of scoring systems that predict survival. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:54. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1070-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee KH, Ahn EJ, Oh SJ, Kim O, Joo YE, Bae JA, et al. KITENIN promotes glioma invasiveness and progression, associated with the induction of EMT and stemness markers. Oncotarget. 2015;6(5):3240–53. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2012;22(3):276–82. doi: 10.11613/BM.2012.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andre F, Berrada N, Desmedt C. Implication of tumor microenvironment in the resistance to chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010;22(6):547–51. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32833fb384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang Y, Wang Y, Kiani MF, Wang B, Classification Treatment strategy, and Associated Drug Resistance in breast Cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2016;16(5):335–43. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giorello MB, Borzone FR, Labovsky V, Piccioni FV, Chasseing NA. Cancer-Associated fibroblasts in the breast Tumor Microenvironment. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2021;26(2):135–55. doi: 10.1007/s10911-020-09475-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amornsupak K, Jamjuntra P, Warnnissorn M, Sa-Nguanraksa POC, Thuwajit D, Eccles P, Thuwajit SA. High ASMA(+) fibroblasts and low cytoplasmic HMGB1(+) breast Cancer cells predict poor prognosis. Clin Breast Cancer. 2017;17(6):441–452e2. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Primac I, Maquoi E, Blacher S, Heljasvaara R, Van Deun J, Smeland HY, et al. Stromal integrin α11 regulates PDGFR-β signaling and promotes breast cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(11):4609–28. doi: 10.1172/JCI125890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamashita M, Ogawa T, Zhang X, Hanamura N, Kashikura Y, Takamura M, Yoneda M, Shiraishi T. Role of stromal myofibroblasts in invasive breast cancer: stromal expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin correlates with worse clinical outcome. Breast Cancer. 2012;19(2):170–6. doi: 10.1007/s12282-010-0234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paulsson J, Rydén L, Strell C, Frings O, Tobin NP, Fornander T, Bergh J, Landberg G, Stål O, Östman A. High expression of stromal PDGFRβ is associated with reduced benefit of tamoxifen in breast cancer. J Pathol Clin Res. 2017;3(1):38–43. doi: 10.1002/cjp2.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartoschek M, Oskolkov N, Bocci M, Lövrot J, Larsson C, Sommarin M, et al. Spatially and functionally distinct subclasses of breast cancer-associated fibroblasts revealed by single cell RNA sequencing. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):5150. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07582-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu SZ, Roden DL, Wang C, Holliday H, Harvey K, Cazet AS, et al. Stromal cell diversity associated with immune evasion in human triple-negative breast cancer. Embo J. 2020;39(19):e104063. doi: 10.15252/embj.2019104063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Costa A, Kieffer Y, Scholer-Dahirel A, Pelon F, Bourachot B, Cardon M, et al. Fibroblast heterogeneity and immunosuppressive environment in human breast Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33(3):463–479e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim HM, Jung WH, Koo JS. Expression of cancer-associated fibroblast related proteins in metastatic breast cancer: an immunohistochemical analysis. J Transl Med. 2015;13:222. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0587-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park SY, Kim HM, Koo JS. Differential expression of cancer-associated fibroblast-related proteins according to molecular subtype and stromal histology in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;149(3):727–41. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeon W, Jang BS, Jeon SH, Kim JH, Kim YJ, Kim SH, Kim CY, Han JH, Kim IA. Analysis of survival outcomes based on molecular subtypes in breast cancer brain metastases: a single institutional cohort. Breast J. 2018;24(6):920–6. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahai E, Astsaturov I, Cukierman E, DeNardo DG, Egeblad M, Evans RM, et al. A framework for advancing our understanding of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(3):174–86. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0238-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajkumar VS, Shiwen X, Bostrom M, Leoni P, Muddle J, Ivarsson M, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor-beta receptor activation is essential for fibroblast and pericyte recruitment during cutaneous wound healing. Am J Pathol. 2006;169(6):2254–65. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shinde AV, Humeres C, Frangogiannis NG. The role of α-smooth muscle actin in fibroblast-mediated matrix contraction and remodeling. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2017;1863(1):298–309. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tschumperlin DJ, Lagares D. Mechano-therapeutics: Targeting Mechanical Signaling in Fibrosis and Tumor Stroma. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;212:107575. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sperduto PW, Berkey B, Gaspar LE, Mehta M, Curran W. A new prognostic index and comparison to three other indices for patients with brain metastases: an analysis of 1,960 patients in the RTOG database. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70(2):510–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sperduto PW, Mesko S, Li J, Cagney D, Aizer A, Lin NU, et al. Beyond an updated graded Prognostic Assessment (breast GPA): a Prognostic Index and Trends in treatment and survival in breast Cancer Brain Metastases from 1985 to today. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;107(2):334–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.