Highlights

-

•

Project Catalyst promoted cross-sector collaboration within states.

-

•

Collaboration within state leadership teams increased 17% during the project.

-

•

States made practice and policy changes to improve IPV services.

-

•

State collaborations may lead to policies improving IPV survivors’ health/safety.

Keywords: Intimate partner violence, Human trafficking, Domestic violence, State leadership, Collaboration, Cross sector collaboration, Health policy

Abstract

Intimate Partner Violence and Human Trafficking are major public health problems with myriad health and social consequences. This paper describes a federal initiative in the United States to formalize cross-sector collaborations at the state-level and encourage practice and policy changes intended to promote prevention and improve health and safety outcomes for Intimate Partner Violence/Human Trafficking (IPV/HT) survivors.

Project Catalyst Phases I and II (2017–2019) engaged six state leadership teams, consisting of leaders from each state’s Primary Care Association, Department of Health, and Domestic Violence Coalition. Leadership teams received training and funding to disseminate information on trauma-informed practices to health centers and integrate IPV/HT considerations into state-level initiatives. At the beginning and end of Project Catalyst, participants completed surveys assessing the status of their collaboration and project goals (e.g., number of state initiatives involving IPV/HT, number of people trained).

All domains of collaboration increased from baseline to project end. Largest improvements were seen in ‘Communication’ and ‘Process & Structure,’ both of which increased by more than 20% over the course of the project. ‘Purpose’ and ‘Membership Characteristics’ increased by 10% and 13%, respectively. Total collaboration scores increased 17% overall. Each state made substantial efforts to integrate and improve responses to IPV/HT in community health centers and domestic violence programs, and integrated IPV/HT response into state-level initiatives.

Project Catalyst was successful in facilitating formalized collaborations within state leadership teams, contributing to practice and policy changes intended to improve health and safety for IPV/HT survivors.

1. Introduction

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV), defined as sexual violence, stalking, physical violence, and psychological aggression perpetrated by a romantic or sexual partner, is a significant public health problem with profound health and social consequences throughout the lifespan (Smith et al., 2018). Those who have experienced IPV are more likely to have chronic health conditions, mental health concerns, and higher rates of alcohol/tobacco use (Breiding et al., 2008). Instances of violence and sexual coercion can both directly cause and exacerbate health conditions by creating barriers for survivors to seek medical care, keep appointments, and follow treatment guidelines (Miller & McCaw, 2019). Alongside increasing attention to the health effects of IPV, there has been a growing awareness of the prevalence and consequences of human trafficking, which includes sexual exploitation, forced labor, and domestic servitude (Cockbain and Bowers, 2019, Richards, 2014). Like IPV, human trafficking has significant negative health effects (Oram et al., 2012, Richards, 2014, Zimmerman et al., 2011, Zimmerman and Kiss, 2017). Given the associations between Intimate Partner Violence/Human Trafficking (IPV/HT) and chronic health conditions, the healthcare and public health sectors are well-positioned to offer support and services to IPV/HT survivors.

Healthcare providers can play a major role in reducing the short- and long-term health impacts of IPV/HT (Colombini et al., 2008, Hamberger et al., 2015, Macias-Konstantopoulos, 2016). Identification through routine inquiry, universally educating all patients, and providing brief counseling in primary healthcare settings can significantly increase safety and support for survivors and prevent future abuse (Miller & McCaw, 2019; Moyer & US Preventative Services Task Force, 2013). Systems-level interventions that incentivize and enable providers to implement universal education and referral to resources are essential to improving care for those experiencing IPV/HT (Gmelin et al., 2018, Miller-Walfish et al., 2021).

Collaboration between sectors, defined by mutually beneficial, structured relationships with shared goals, success, and responsibility (Mattessich et al., 2001), is key to solving public health problems (Fawcett et al., 2010, Mattessich and Rausch, 2014, Roussos and Fawcett, 2000). Policies at the local, state, and federal level can reinforce collaborative behaviors among community partners (Aarons et al., 2016, Gakh, 2015, Towe et al., 2016); however, each agency must “buy in” for positive results of collaboration to be sustainable (Aarons et al., 2014, Green et al., 2016). Formalized partnerships between victim service agencies and health care centers have resulted in meaningful changes to clinic policy through modification of guidelines, training requirements, and screening tools (Miller-Walfish et al., 2021). Such formalized collaboration has also been shown to shift policies and protocols within victim service agencies (Miller-Walfish et al., 2021). Understanding how state-level organizations interact with each other and achieve collective goals can inform efforts to increase cross-sector collaboration, ultimately improving the health and safety of patients.

‘Project Catalyst: Statewide transformation on health, IPV, and human trafficking’ was designed to increase cross-sector collaboration and encourage policy changes that would ultimately promote prevention and improve health and safety outcomes for IPV/HT survivors (Futures Without Violence, 2023). This paper describes the effect of Project Catalyst on collaboration between state agencies and explores how collaboration is associated with states’ efforts to improve care for IPV/HT survivors.

2. Methods

2.1. Project overview

Project Catalyst aimed to increase collaboration between the Primary Care Association, Department of Health, and Domestic Violence Coalition in participating states/territories in the United States. This paper includes data from six funded states in Phases I and II of Project Catalyst (2017–2019). One territory was excluded because of significant differences in inter-agency structure and geographic outreach. Phase III was not included because its project period was substantially longer due to the COVID-19 pandemic and collaborations were influenced by the emphasis on pandemic response. The six states represented four regions (2 South, 1 Northeast, 1 Midwest, 2 West), with populations ranging from approximately 1.5 to 9.5 million (5%-43% living in nonmetro areas) (US, 2022). Funding was awarded through a competitive selection process. Most states received $75,000; one state received $25,000 because they were unable to engage their Department of Health. The funding period was 10 months. All procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Project Catalyst created State Leadership Teams (SLTs) of leaders from each state’s Primary Care Association, Department of Health, and Domestic Violence Coalition. Each SLT received training and funding to engage and educate Health Resources and Services Administration-funded health centers and Family Violence Prevention and Services Act-funded domestic violence programs in trauma-informed practices for IPV survivors. SLTs were also encouraged to integrate IPV/HT considerations into state-level initiatives and incentivize collaboration between health centers and domestic violence programs.

Project Catalyst fostered a collaborative environment through an in-person kick-off event and monthly webinars. In webinars, SLT members discussed successes and challenges facilitating trainings and implementing policy changes. Futures Without Violence provided technical assistance, including hosting ‘Training for Trainers’ so SLT members could train health center staff and IPV advocates in their state. Training of Trainers covered a range of topics, including Healing-Centered Engagement, dynamics of IPV/HT and their impact on survivor health, and strategies for implementing the CUES (Confidentiality, Universal Education, Empowerment, and Support) intervention (Miller et al., 2011, Miller et al., 2015, Miller et al., 2016, Miller et al., 2017). SLT members from previous project phases served as mentors, sharing their experiences to facilitate cooperation and enhance intra-SLT relationships.

2.2. Measures

At the beginning and end of Project Catalyst, SLT members completed the Collaborative Behavior Survey (CBS) and State Policy Assessment tool. The evaluation team distributed the survey at the in-person kick-off meeting and emailed an online follow-up survey to SLT members. SLTs recorded the number of staff trained in their state.

The CBS contained 28 items modified from the Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory and grouped into six domains: Environment, Membership Characteristics, Process & Structure, Communication, Purpose, and Resources (Mattessich et al., 2001). Items were rated on a Likert 5-point scale (1=“strongly disagree” to 5=“strongly agree”). Internal consistency reliability for the full scale was excellent (α = 0.93). Results for the Environment and Resources domains are not reported because of poor reliability (α < 0.5). Membership Characteristics assesses mutual respect and trust within the group and involvement of the right groups (7 items; α = 0.78). Process & Structure assesses understanding of objectives and individual responsibilities, participation, flexibility, and adaptability (7 items; α = 0.87). Communication assesses interactions between group members (2 items; α = 0.73), and Purpose assesses understanding and agreement on vision and goals (6 items; α = 0.78). Scores of 4.0 or above indicate strengths, scores of 3.0–3.9 are borderline or in need of attention, and scores below 3.0 indicate areas of concern (Derose et al., 2004, Mattessich et al., 2001).

The State Policy Assessment tool measured policies, programs, and practices related to IPV/HT response, including the number of state initiatives integrating IPV/HT (Scott et al., in press). SLT members were contacted by email in October 2021 (2–3 years after funding ended) to inquire about progress, including integration of IPV/HT into state initiatives, additional trainings conducted, and other state policy changes made since the conclusion of Project Catalyst.

2.3. Data analyses

Data were analyzed in Stata SEv16.1. Responses from each SLT were aggregated at each time point (baseline and project end) by calculating the median score for each domain. We examined descriptive data, absolute changes, and percent changes for domain scores across states and individually. The number of state-level initiatives integrating IPV/HT at the beginning and end of the project period was tabulated.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

SLT members in all six states completed the baseline survey (N = 19 individuals from 17 organizations). At project end, SLT members from all but two organizations completed follow-up surveys (N = 18 individuals from 15 organizations). All states had at least two respondents at each timepoint. The State Policy Assessment tool was completed by all six states at both baseline and project end. Updates on changes made after project end were provided by five of six states.

3.2. Changes in collaboration across and within states

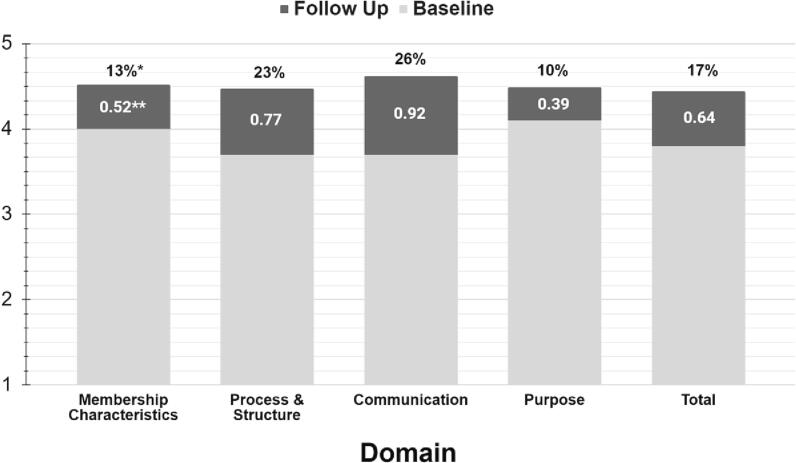

Changes in collaboration across states were evaluated by averaging states’ median scores for each domain at baseline and follow up. The absolute numerical change and percent change in scores are reported in Table 1 and Fig. 1. There were increases in all collaboration domains from baseline to project end. The largest increases were in Communication and Process & Structure, with gains of 0.77–0.92 points reflecting increases of more than 20%. Scores for Purpose and Membership Characteristics were above 4.0 at baseline, but also increased, with gains of 10% and 13%, respectively. Total collaboration scores increased 17%.

Table 1.

Changes in Collaboration Scores across States by Domain.

| Domain | Baseline Score | Follow Up Score | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membership Characteristics | 4.0 | 4.5 | 0.52 | 13% |

| Process & Structure | 3.7 | 4.4 | 0.77 | 23% |

| Communication | 3.7 | 4.6 | 0.92 | 26% |

| Purpose | 4.1 | 4.5 | 0.39 | 10% |

| Total | 3.8 | 4.4 | 0.64 | 17% |

Fig. 1.

Changes in Collaboration across States by Domain: *Percent change in score from baseline to follow-up. **Absolute change in score from baseline to follow-up.

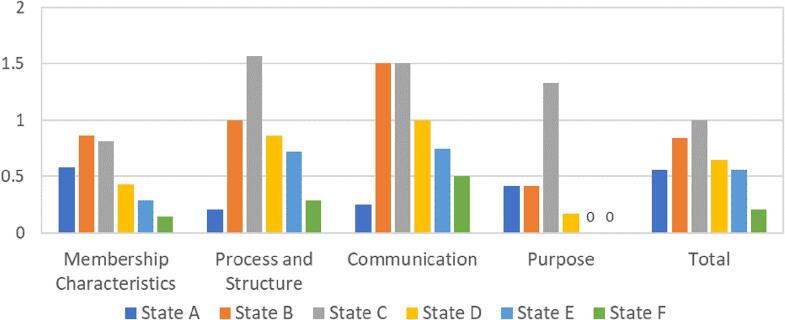

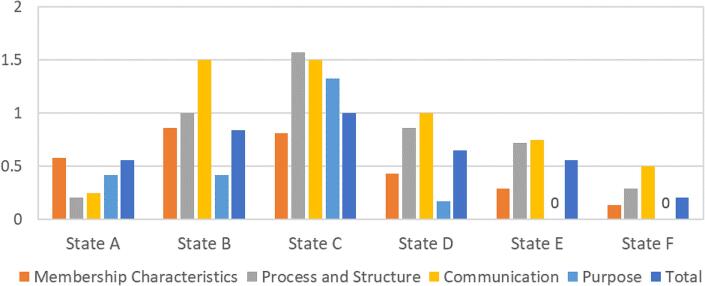

Fig. 2 illustrates changes by domain with each state shown individually. All six states reported absolute positive increases in Membership Characteristics, Process and Structure, and Communication. Increases varied in magnitude, with large increases of 1-point or more for Process & Structure in two states and Communication in three states. No states had an increase of this magnitude in Membership Characteristics. In the Purpose domain, one state experienced a large change (greater than1-point), while three states had smaller changes and two states had no change. All but one state experienced an increase of 0.5-point or more in total collaboration. Fig. 3 illustrates these changes grouped by each individual state.

Fig. 2.

Absolute Change in Collaboration Median Scores by Domain.

Fig. 3.

Absolute Change in Collaboration Median Scores by State.

3.3. Project accomplishments and changes in collaboration by state

Participating states made substantial efforts to improve responses to IPV/HT in community health centers and domestic violence programs. States were expected to train staff in at least five community health centers and five domestic violence programs, and all six states exceeded this expectation.

In addition to training staff (Table 2), states integrated Project Catalyst materials into other trainings and disseminated training tools related to IPV/HT through shared websites for health centers and/or domestic violence programs. States also integrated IPV/HT into state-level initiatives, including those related to clinical quality improvement, the patient-centered medical home, patient engagement, population health, and social determinants of health. Scott and colleagues (2023) provide additional results from the Project Catalyst evaluation. Below we describe changes in collaboration and accomplishments for individual states.

Table 2.

Training Efforts and Integration of IPV/HT into State Initiatives.

| Providers/Advocates Trained | Initiatives Reported at Start of Project Catalyst | Initiatives Reported at End of Project Catalyst | |

|---|---|---|---|

| State A | 258 | 2 | 0 |

| State B | 306 | 1 | 1 |

| State C | 211 | 2 | 1 |

| State D | 81 | 0 | 7 |

| State E | 90 | 1 | 7 |

| State F | 151 | 1 | 4 |

State A had small-to-moderate positive absolute changes in all domains (5–17%). Their total collaboration score increased from 4.0 to 4.5, indicating that the state began with solid collaboration that was further strengthened during the project. Although IPV/HT was integrated into two state initiatives at project start, no initiatives were reported at project end. State A was the only state that did not integrate IPV/HT into any state-level initiatives during the project period. Following Project Catalyst, State A reported continued training efforts, including providing CUES training to health professionals, integrating trauma-informed practices into curriculums in multiple sectors (e.g., law enforcement, faith, education), and adapting the curriculum for new audiences (e.g., veterinary technology students). State A also reported collaborations with other state coalitions and plans to seek grant funding.

State B demonstrated increases in Membership Characteristics (21%), Process & Structure (28%), and Communication (43%), with a smaller 10% improvement in Purpose. At baseline, their total collaboration score of 3.8 indicated collaboration that was ‘borderline;’ however, their score increased to 4.6 by the end of the project. State B reported integrating IPV/HT into one initiative at project start and one new initiative at project conclusion. Since the end of the project, State B’s Coalition Against Domestic Violence and Community Health Center Association partnered to create online learning modules to educate health center staff on the health impacts of IPV. The state also provided training for staff in Ryan White HIV/AIDS programs and developed a process to certify Case Managers as IPV advocates. State B’s leadership team continues to collaborate to provide resources (e.g., CUES safety cards) to health centers.

State C exhibited consistent improvements across all domains, with large increases (greater than 1.3 points; 36–52%) in Process & Structure, Communication, and Purpose, as well as Membership Characteristics (21%). State C was the only state with a substantial improvement in Purpose; it had the lowest score at baseline and the highest possible score at follow-up. All domain scores improved from the ‘borderline’ range to the ‘strength’ range, with the total score increasing from 3.5 to 4.5. State C reported integrating IPV/HT into two initiatives at the start of Project Catalyst, one of which was also reported at project conclusion. At follow-up, State C reported continued efforts to integrate IPV into new state initiatives and programs (e.g., Falls Prevention Coalition, support program for court-involved families, Maternal Mortality Review Committee, health coaching program). The state Department of Public Health also received a grant to provide technical assistance to improve systems’ responses to survivors of violence. State C used these funds to create tailored, state-specific resources for use by IPV advocates, health center staff, and local health coaches.

State D improved 24% in Process & Structure and 25% in Communication. There were smaller changes in Membership Characteristics (12%) and Purpose (4%). Their total collaboration score increased from 3.6 to 4.3. Although IPV/HT was not integrated into any initiatives at project start, State D reported integration into seven initiatives at project conclusion. This was the largest increase in initiative number reported by any state. Members of the State D leadership team were not reachable for follow-up; accordingly, the extent to which these efforts continued after the project ended is unknown.

State E exhibited moderate increases in Process & Structure (19%) and Communication (23%). There was a small change in Membership Characteristics (7%) and no change in Purpose. Their total collaboration score increased from 3.8 to 4.4 by the end of the project. State E reported integrating IPV/HT into one initiative at the start of Project Catalyst and seven initiatives at its conclusion, demonstrating substantial progress during the project period. Since that time, State E has continued training medical, dental, and behavioral health specialists. State E has also provided tangible resources like first aid kits and Narcan to improve care.

State F had small changes across domains, with improvements of 4–14%, and no change in Purpose. The SLT reported good collaboration at baseline, with a total score of 4.0, and a slight increase to a total score of 4.3 at project end. The SLT in State F included only the Primary Care Association and Domestic Violence Coalition; the Department of Health was not involved, and the state received less funding than others. State F reported integrating IPV/HT into one initiative at project start and four initiatives at project end. Since project conclusion, State F implemented a state-level program to address IPV as part of their Medicaid health system transformation work and began participating in an LGBT health improvement network. The SLT continues to disseminate information about IPV to health centers and domestic violence programs. They also obtained additional grant funding to adapt materials for local Indigenous communities.

4. Discussion

Project Catalyst was designed to increase collaboration between states’ Primary Care Associations, Departments of Health, and Domestic Violence Coalitions. Leadership teams in each state were provided training and funding to educate staff in health centers and domestic violence programs and encouraged to disseminate information on trauma-informed practices, integrate IPV/HT considerations into state-level initiatives, and incentivize collaboration between health centers and domestic violence programs. At project start, collaboration scores for 4 of 6 SLTs indicated that their collaboration ‘needed attention,’ while scores for the remaining two SLTs indicated that collaboration was a strength. All SLTs demonstrated improvements in multiple domains of collaboration during the project. Although the magnitude of changes varied by state, total scores for each SLT indicated strong collaboration by project end. Similarly, although efforts to address IPV/HT varied, all states greatly exceeded the expectations of Project Catalyst.

During the project period, States A, B, and C trained larger numbers of providers, while States D, E, and F successfully integrated IPV/HT into multiple state initiatives. Interestingly, the states that were able to train the largest number of advocates saw decreases or no change in the number of initiatives at project end. These findings suggest that states differed in their focus during the project period, with some SLTs prioritizing training and others prioritizing system-level changes. After the project ended, states continued their efforts to varying degrees. All states who provided follow-up information described continued training efforts. State E also distributed tangible resources, and States C and F integrated IPV into new state initiatives and obtained additional grant funding.

In States D and E, improvements in SLT collaboration occurred concurrently with observable indicators of progress, specifically increases in the number of state initiatives integrating IPV/HT during the project. For States B and C, substantial improvements in collaboration during the project period appeared to facilitate ongoing and expanding efforts to address IPV/HT after the project ended. State C demonstrated particularly substantial growth, reporting several new state initiatives and securing additional funding. State C was the only state with a large increase in Purpose, and it is possible that shared purpose may be important to sustained collaborative efforts. Lastly, although States A and F both exhibited relatively little change in collaboration during Project Catalyst, these two states had the highest total collaboration scores at the start of the project, indicating that SLT collaboration was already a relative strength. State A reported expanded training efforts at follow-up, and State F reported successfully integrating IPV/HT into state initiatives during and after Project Catalyst. The SLT in State F was smaller and received less funding; they may have collaborated with other state partners who were not formally involved in Project Catalyst to achieve their goals.

Across states, the largest improvements were seen in the Communication domain. Previous studies of cross-sector collaboration have found that formal partnerships can improve communication and relationships between individuals in different sectors (Gmelin et al., 2018, Green et al., 2016, Miller-Walfish et al., 2021, Wendel et al., 2010). Accordingly, Project Catalyst as an intervention strategy is well-equipped to improve groups’ interactions with each other. Monthly virtual meetings encouraged partners, researchers, and funders to communicate with and seek technical assistance from other member organizations. SLTs participated in planning calls with the technical assistance provider and were encouraged to reflect on their work as a team; these strategies may have further strengthened communication within SLTs. Effective communication can facilitate ongoing collective learning and mutual trust, which are critical to effective collaboration (Aarons et al., 2014, de Montigny et al., 2019).

Large increases were also seen in the Process & Structure domain. Common challenges to collaboration include unclear roles and responsibilities, conflicting organizational cultures and priorities, and differences in professional training and approaches (Aarons et al., 2014, Gmelin et al., 2018, McCullough et al., 2020). Project Catalyst provided a unifying goal along with clear expectations and roles for each organization in the SLT. Action planning activities and ongoing technical assistance may have helped SLTs clarify objectives and roles during the project. The large changes in Process & Structure suggest that Project Catalyst led to improvements in understanding of objectives and individual responsibilities, participation, flexibility, and adaptability within the states.

Smaller increases were evident in the domains of Membership Characteristics and Purpose. Baseline scores in both domains were relatively high, indicating that most SLTs began the project with trust, respect, and agreement on vision. Notably, the two states that saw no change in Purpose both started with scores of 4.3 at baseline. The grant application process may have facilitated growth in these domains prior to the start of the project. Continued attention to these domains is warranted to build upon strengths in these areas, as complacency in any area may be detrimental to the sustainability of existing partnerships.

5. Limitations

The small number of states limits the generalizability of our results to other states. No states had scores indicating problematic collaboration at the project start, perhaps because the application process required some baseline collaboration between the agencies involved. Collaboration prior to the project may have created a floor effect and limited potential improvements in collaboration; still, it is notable that even SLTs with strong collaboration at the start of the project demonstrated remarkable improvement.

Participants’ knowledge of project goals and limited anonymity may have increased social desirability and other response biases. In addition, follow-up data collection was less standardized and may have resulted in reporting biases. Our measure of collaboration did not adequately assess Environment (i.e., history of collaboration, political climate) and Resources (i.e., funding, human capital, leadership skills), with these subscales demonstrating poor internal consistency reliability. Qualitative assessment of these domains in future research may help us better understand heterogeneity within these domains and how they change over time. Qualitative and mixed methods studies are needed to increase our understanding of how collaboration develops, is sustained, and translates into measurable changes in policies and practices. Lastly, although the practice and policy changes made by states were intended to improve health and safety outcomes for IPV/HT survivors, we are unable to evaluate the actual impact of these changes on survivors’ outcomes.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Overall, our findings suggest that Project Catalyst was successful in facilitating collaboration within SLTs. All participating states made substantial practice and policy changes intended to improve health and safety outcomes for IPV/HT survivors, meeting the goals of Project Catalyst. Both trainings and state-level initiatives are crucial for supporting survivors of violence. Formal partnerships, such as those created through Project Catalyst, facilitate the identification of shared goals and values among organizations and individuals with diverse perspectives and approaches. Although differences in organizational culture, expectations, and approaches may serve as barriers to collaboration, intentional efforts to identify shared values and discuss differences can overcome mistrust and frustration between organizations (Aarons et al., 2014). Here, states that experienced improvements in communication and the process and structure of the collaboration saw sustained impact of Project Catalyst through the integration of IPV/HT into state-level initiatives and policy changes.

Structural changes are needed to create, sustain, and reinforce collaboration across sectors to address high-priority issues like IPV/HT. As Project Catalyst demonstrated, efforts to provide infrastructure and ongoing support can effectively increase collaboration and lead to changes in practices and policies. Legislation to authorize or require collaboration as well as to provide funding to monitor and prioritize collaborative efforts should be considered (Gakh, 2015). Without adequate infrastructure and support, legislative mandates are unlikely to lead to authentic collaboration (Gakh, 2015). State and federal efforts to provide stable infrastructure and ongoing support are necessary to build and sustain effective cross-sector partnerships.

Funding: Project Catalyst was supported through a collaboration of U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) partners, including the Administration for Children and Families’ Family and Youth Services Bureau, the Health Resources and Services Administration Bureau of Primary Health Care and Office of Women’s Health. EAM is supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH123729).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Richard B. Brown: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. Summer Miller-Walfish: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. Sarah Scott: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Anisa Ali: Writing – review & editing. Anna Marjavi: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Project administration. Elizabeth Miller: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. Elizabeth A. McGuier: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

We thank Mr. Cody Januszko for proofreading this article.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Aarons G.A., Fettes D.L., Hurlburt M.S., Palinkas L.A., Gunderson L., Willging C.E., Chaffin M.J. Collaboration, negotiation, and coalescence for interagency-collaborative teams to scale-up evidence-based practice. J. Clinical Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2014;43(6):915–928. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.876642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons G.A., Green A.E., Trott E., Willging C.E., Torres E.M., Ehrhart M.G., Roesch S.C. The roles of system and organizational leadership in system-wide evidence-based intervention sustainment: A mixed-method study. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2016;43(6):991–1008. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0751-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiding, M. J., Black, M. C., & Ryan, G. W. (2008). Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence in eighteen U.S. states/territories, 2005. Am. J. Prevent. Med., 34(2), 112–118. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cockbain E., Bowers K. Human trafficking for sex, labour and domestic servitude: How do key trafficking types compare and what are their predictors? Crime Law Soc. Chang. 2019;72(1):9–34. doi: 10.1007/s10611-019-09836-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colombini M., Mayhew S., Watts C. Health-sector responses to intimate partner violence in low- and middle-income settings: A review of current models, challenges and opportunities. Bull. World Health Organ. 2008;86(8):635–642. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.045906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Montigny J.G., Desjardins S., Bouchard L. The fundamentals of cross-sector collaboration for social change to promote population health. Glob. Health Promot. 2019;26(2):41–50. doi: 10.1177/1757975917714036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derose K.P., Beatty A., Jackson C.A. Evaluation of Community Voices Miami: Affecting health policy for the uninsured. RAND Corporation. 2004 https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR177.html [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett S., Schultz J., Watson-Thompson J., Fox M., Bremby R. Building multisectoral partnerships for population health and health equity. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2010;7(6):A118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futures Without Violence Project Catalyst: Statewide transformation on health, IPV, and human trafficking. Futures Without Violence. 2023 http://www.futureswithoutviolence.org/health/project-catalyst/ [Google Scholar]

- Gakh M. Law, the health in all policies approach, and cross-sector collaboration. Public Health Rep. 2015;130(1):96–100. doi: 10.1177/003335491513000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmelin T., Raible C.A., Dick R., Kukke S., Miller E. Integrating reproductive health services into intimate partner and sexual violence victim service programs. Violence Against Women. 2018;24(13):1557–1569. doi: 10.1177/1077801217741992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green A.E., Trott E., Willging C.E., Finn N.K., Ehrhart M.G., Aarons G.A. The role of collaborations in sustaining an evidence-based intervention to reduce child neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;53:4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger L.K., Rhodes K., Brown J. Screening and intervention for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings: Creating sustainable system-level programs. J. Women’s Health. 2015;24(1):86–91. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias-Konstantopoulos W. Human trafficking: The role of medicine in interrupting the cycle of abuse and violence. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016;165(8):582–588. doi: 10.7326/M16-0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattessich P.W., Murray-Close M., Monsey B.R. 2nd edition. Amherst H; Wilder Foundation: 2001. Collaboration: What makes it work. [Google Scholar]

- Mattessich P.W., Rausch E.J. Cross-sector collaboration to improve community health: A view of the current landscape. Health Aff. 2014;33(11):1968–1974. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough J.M., Eisen-Cohen E., Lott B. Barriers and facilitators to intraorganizational collaboration in public health: Relational coordination across public health services targeting individuals and populations. Health Care Manage. Rev. 2020;45(1):60–72. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E., Decker M.R., McCauley H.L., Tancredi D.J., Levenson R.R., Waldman J., Schoenwald P., Silverman J.G. A family planning clinic partner violence intervention to reduce risk associated with reproductive coercion. Contraception. 2011;83(3):274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E., Goldstein S., McCauley H.L., Jones K.A., Dick R.N., Jetton J., Silverman J.G., Blackburn S., Monasterio E., James L., Tancredi D.J. A school health center intervention for abusive adolescent relationships: A cluster RCT. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):76–85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E., Tancredi D.J., Decker M.R., McCauley H.L., Jones K.A., Anderson H., James L., Silverman J.G. A family planning clinic-based intervention to address reproductive coercion: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2016;94(1):58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E., McCauley H.L., Decker M.R., Levenson R., Zelazny S., Jones K.A., Anderson H., Silverman J.G. Implementation of a family planning clinic–based partner violence and reproductive coercion intervention: Provider and patient perspectives. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health. 2017;49(2):85–93. doi: 10.1363/psrh.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E., McCaw B. Intimate Partner Violence. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(9):850–857. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1807166. PMID: 30811911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Walfish S., Kwon J., Raible C., Ali A., Bell J.H., James L., Miller E. Promoting cross-sector collaborations to address intimate partner violence in health care delivery systems using a quality assessment tool. J. Women’s Health. 2021;30(11):1660–1666. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer, V. A. & US Preventative Services Task Force. (2013). Screening for intimate partner violence and abuse of elderly and vulnerable adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann. Int. Med., 158(6), 478–486. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-6-201303190-00588. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Oram, S., Stöckl, H., Busza, J., Howard, L. M., & Zimmerman, C. (2012). Prevalence and risk of violence and the physical, mental, and sexual health problems associated with human trafficking: Systematic review. PLOS Medicine, 9(5), e1001224. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Richards T.A. Health implications of human trafficking. Nurs. Women’s Health. 2014;18(2):155–162. doi: 10.1111/1751-486X.12112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussos S.T., Fawcett S.B. A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2000;21(1):369–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, S., Risser, L., Miller-Walfish, S., Marjavi, A., Ali, A., Segebrecht, J., & Miller, E. (in press). Policy and Systems Change in Intimate Partner Violence and Human Trafficking: Evaluation of a Federal Cross-Sector Initiative. J. Women’s Health. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Smith, S. G., Xinjian, Z., Basile, K. C., Merrick, M. T., Wang, J., Kresnow, M., & Chen, J. (2018). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data Brief—Updated Release (p. 32). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention.

- Towe V.L., Leviton L., Chandra A., Sloan J.C., Tait M., Orleans T. Cross-sector collaborations and partnerships: Essential ingredients to help shape health and well-being. Health Aff. 2016;35(11):1964–1969. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. State Fact Sheets, December 2022. Retrieved from https://ers.usda.gov/data-products/state-fact-sheets/.

- Wendel M.L., Prochaska J.D., Clark H.R., Sackett S., Perkins K. Interorganizational network changes among health organizations in the Brazos Valley, Texas. J. Primary Prevent. 2010;31(1):59–68. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0203-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman C., Hossain M., Watts C. Human trafficking and health: A conceptual model to inform policy, intervention and research. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011;73(2):327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman C., Kiss L. Human trafficking and exploitation: A global health concern. PLoS Med. 2017;14(11):e1002437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.