Abstract

Background

Consumption of medication to alleviate pain is widespread in Germany. Around 1.9 million men and women take analgesics every day; some 1.6 million persons are addicted to painkillers. Analgesic use is thought also to be common in sports, even in the absence of pain. The aim of this study was to assess the extent of painkiller use among athletes.

Methods

In line with the PRISMA criteria and the modified PICO(S) criteria, a systematic literature review was registered (Openscienceframework, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/VQ94D) and carried out in PubMed and SURF. The publications identified (25 survey studies, 12 analyses of doping control forms, 18 reviews) were evaluated in standardized manner using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) and AMSTAR (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews).

Results

Analgesic use is widespread in elite sports. The prevalence varies between 2.8% (professional tennis) and 54.2% (professional soccer). Pain medication is also taken prophylactically in the absence of symptoms in some non-elite competitive sports. In the heterogeneous field of amateur sports the data are sparse and there is no reliable evidence of wide-reaching consumption of painkillers. Among endurance athletes, 2.1% of over 50 000 persons stated that they used analgesics at least once each month in connection with sports.

Conclusion

Analgesic use has become a problem in many areas of professional/competitive sports, while the consumption of pain medication apparently remains rare in amateur sports. In view of the increasing harmful use of or even addiction to painkillers in society as a whole, there is a need for better education and, above all, restrictions on advertising.

Around 1.9 million people in Germany take painkillers every day (1). According to estimates based on data from the Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse (Epidemiologischer Suchtsurvey), harmful consumption of painkillers (7.6%) is significantly higher than that of alcohol (2.8%) (1– 3). Dependence on painkillers (3.2%) is reported to be close to dependence on alcohol (3.1%). According to a survey carried out by the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) in 2013/2014, 30% to 40% of respondents reported that physical pain was not a factor in their use of over-the-counter painkillers (4). According to findings of the 2021 Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse, the 30-day prevalence of nonopioid analgesic use in the German population is 47.4% (e28). Given the prevalence of harmful use of painkillers and painkiller dependence in society in general, Heinz and Liu (2019) called for more studies and systematic reviews to be carried out (5).

The use of analgesics is said to be widespread not only in the general population but also specifically in sport. Here, too, analgesics are apparently often consumed in the absence of symptoms (6– 8). For example, according to studies based on data from doping control forms (DCFs), between 16.7% and 54.2% of professional football players take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (9, 10). Since doping controls are mandatory and the forms are more or less standardized, DCFs are well suited as a basis for estimating consumption of analgesics in elite-level and professional sports.

Media reports by the ARD Doping Editorial Team on excessive use of analgesics in football (11) led to a public hearing (on 27 January 2021) of experts in the German Bundestag Sports Committee on “Painkiller consumption in sport and society” (12). This revealed a heterogeneous and incomplete picture of the use of analgesics in sports, especially amateur sports. The aim of the present study was to achieve a more accurate assessment of the use of analgesics in sport.

Method

In accordance with the guidelines of the PRISMA (“preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses”) statement, a systematic, keyword-led search was carried out for publications dating from the year 2000 onwards on the use and abuse of analgesics in sport (13, 14). The literature search was conducted on 30 July 2021 on Medline and PubMed Central via PubMed, and on SURF (Sport And Research in Focus), the sport information portal of the German Federal Institute of Sport Science (Bundesinstitut für Sportwissenschaft, BISp) using the keywords listed in eTable 1. This was supplemented by a hand search. As a final step, the literature search was updated on 3 July 2022. The criteria for inclusion and exclusion of publications were determined according to a modified PICO(S) framework (etable 2). The study protocol was registered as a “free registration” at the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io). Titles and abstracts in English, French, and German were selected by two independent review panels. The suitability of the full texts selected was checked by three authors independently. If their initial evaluations were discordant, consensus was reached through discussion.

eTable 1. Search strategy for the literature review.

| Step | Operator | Search terms |

| 1 | („Painkiller abuse“ OR „pain medication“ OR analgesic* OR „anti-inflammatory drugs“ OR paracetamol OR ibuprofen OR NSAR OR NSAID*) | |

| 2 | AND | (Physical activity OR sport OR physical training OR exercise OR physical performance) |

| 3 | AND | (Use OR abuse OR misuse) |

| 4 | NOT | Therapy |

eTable 2. Inclusion/exclusion criteria: modified PICOS framework.

| P – Population | Athletes in professional, high-performance, and amateur sports |

| I – Intervention | Use and (prophylactic) consumption of analgesics (especially freely available and widely used OTC products such as ibuprofen and paracetamol, COX inhibitors, and other NSAIDs) in connection with sports activity. The use of prescription drugs, opiates, and opioids was not a search criterion. The focus was on nondoping substances that according to WADA criteria are assessed as performance-enhancing and are prohibited in sport. |

| C – Comparison | Individuals who were active in sports without using analgesics. |

| O – Outcome | Information on the consumption of analgesics and the pattern of their use by athletes, with or without information on any connection with the sports activity. |

| S – Study design | Cross-sectional and longitudinal data collection and survey studies as well as review articles in English, French, and German published from 2000 onward were included. Telephone interviews were excluded. |

COS, cyclooxygenase; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; OTC, over-the-counter; WADA, World Anti-Doping Agency

The original and review articles selected were categorized according to, among other things:

Target groups/sport groups in professional/elite sport, high-performance sport, and amateur sport;

Data collection method (for example, doping control forms, surveys);

Prevalence time periods for analgesic use;

Whether they discussed adverse drug reactions and provided data on the analgesic group or substance class (eTable 3).

eTable 3a. Studies of analgesic use in professional and elite sports (data collected from doping control forms).

| Study (reference) | Study population | Number (n) | Prevalence period | Point prevalence | Frequency of use | Use related to sport | Information on analgesic group or substance class | Any discussion of adverse drug effects | ||||

| Before competition/match day | On competition/match day | Yes | n.d. | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||

| Corrigan and Kazlauskaz (2003) (26) | Olympic Games Sydney 2000 Various sports | 2758 | 3 days before doping control | 25.6% NSAIDs | X | X | X | |||||

| Kavukcu, Burgazli (2013) (36) | Football UEFA Champions League, UEFA Cup, Turkish Super League Football 2003 to 2007 |

4176 | 72 h before the match | Use of at least one analgesic product: 34.9% NSAIDs 6.1% other analgesics |

X | X | X | |||||

| Pedrinelli et al. (2015) (e6) | Football FIFA World Cup 2000 to 2012 | 1064 | 72 h before doping control | 27.3% NSAIDs 17.5% other analgesics |

X | X | X | |||||

| Oester et al. (2019) (e4) | Football FIFA World Cup 2018 | 736 | 72 h before the match | 40.0% NSAIDs 17.0% other analgesics |

X | X | X | |||||

| Trinks et al. (2021) (e14) | Football – top German leagues, Cup, and A and B Junior Bundesliga 2015/16 to 2019/20 | 8344 | 7 days before doping control | 33.0% analgesics (2015/16 to 2019/20), of which 48.0% ibuprofen 22.0% diclofenac 10.0% paracetamol 6.0% ASA |

X | X | X | |||||

| Tscholl et al. (2008) (e15) | Football World Cup 2002 and 2006 | 2944 | 72 h before the match | 30.8% NSAIDs 4.0% other analgesics per match |

X | X | X | |||||

| Tscholl et al. (2009) (9) | Football 6 FIFA Men’s World Cup tournaments U-17 to U-20 and Women’s World Cup 2003 to 2007 | 2488 | 72 h before the match | 16.7% – 36.6% NSAIDs 0.1– 5.9% other analgesics |

X | X | X | |||||

| Tscholl et al. (2010) (e16) | World Athletics Championships 12 IAAF Youth and Veterans 2003 to 2008 | 3887 | 7 days before doping control | 27.3% NSAIDs 13.1% other analgesics |

X | X | X | |||||

| Tscholl and Dvorak (2012) (e19) | Football FIFA World Cup 2010 | 736 | 72 h before the match | 34.6% NSAIDs and 6.4% other analgesics |

X | X | X | |||||

| Tsitsimpikou et al. (2009) (e20) | Olympic Games 2004Various sports | 2463 | 3 days before competing | 11.1% NSAIDs and 3.7% other analgesics |

X | X | X | |||||

| van Thuyne et al. (2008) (e21) | Dutch and Belgian elite athletes competing in individual and ball sports 2002 to 2005 | 18 645 | 3 days before competing | NSAIDs: 20.9%–31.1% volleyball 18.6%–25.7% football 16.3%–23.7% basketball 14.3%–16.2% handball 11.2%–14.9% athletics 4.4%–12.3% swimming 4.0%–5.7% cycling 2.8%–16.3% tennis Other analgesics: 0.5%–0.8% volleyball 0.8%–2.1% football 0.0%–1.8% basketball 0.9%–2.6% handball 0.4%–0.9% athletics 0.0%–2.3% swimming 0.8%–2.7% cycling 0.0%–2.9% tennis |

X | X | X | |||||

| Vaso et al. (2015) (10) | FIFA World Cup 2014 | 736 | 72 h before the competing | NSAIDs: 54.2% FIFA World Cup 30.6% Match Other analgesics: 12.6% FIFA World Cup 5.4% Match |

X | X | X | |||||

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; n. d., no data; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

The main distinguishing features between the three sport groups were:

Revenue (professional versus elite sport);

Performance level (professional/elite sport versus high-performance sport);

Time commitment and the performance concept (high-performance sport versus amateur sport).

Evaluation of publications and studies

The studies selected were independently assessed by three authors in a standardized manner for the quality of their methodology and their risk of bias using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (15). Cross-sectional cohort and survey studies were assessed using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) with regard to selection of study participants, data collection, comparability of study groups, and quality of ascertainment of exposure (16).

Reviews, which ranged from the narrative to the selective or systematic, were reviewed using AMSTAR (“a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews”) (15). The criteria were: study design, study selection, data extraction, systematic literature search, study data/characteristics, consideration of the risk of bias in the primary studies, statistics, and potential conflicts of interest.

If the initial evaluations were discordant, consensus was reached through discussion. The study quality or the risk of bias in the study findings was not used as an exclusion criterion.

Results

Publication selection and study evaluation

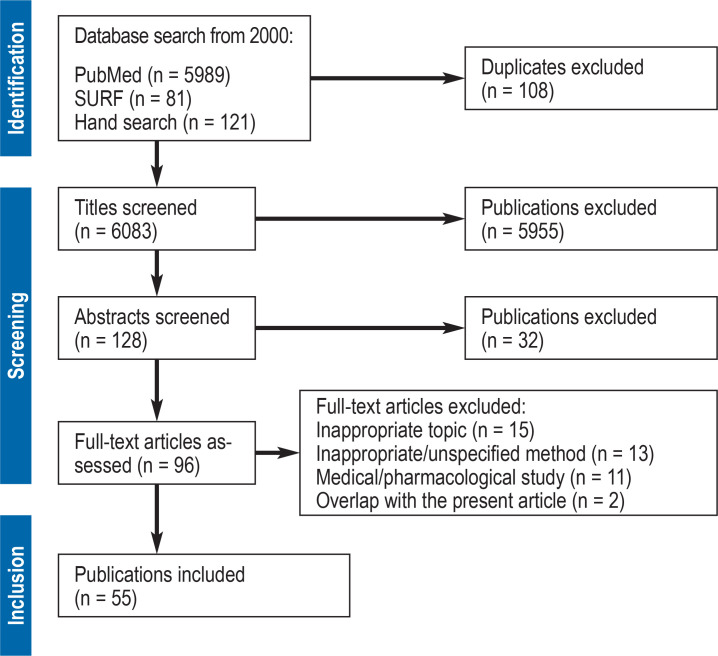

Out of 6191 publications, after removal of duplicates 6083 studies remained for title screening (figure). Of these, 128 studies were identified for abstract analysis and 96 were selected for full text analysis. Of these publications, 41 full texts were excluded, and 55 publications remained for content analysis (6– 10, 12, 17– 40, e1– e25).

Figure.

PRISMA flow chart of the literature review: PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; SURF, sport information portal of the German Federal Institute of Sport Science

For the selected publications on the use of analgesics in sport, the NOS and AMSTAR assessment tools revealed varying degrees of representativeness, quality limitations, and risk of bias. eTable 4 lists studies based on doping control forms, all of which were rated using the NOS instrument at 7–8 stars out of a possible maximum of 9. In contrast to this, the risks of limited representativeness and bias are much higher in survey studies (etable 5); here the study ratings ranged from 2 to 7 stars. According to AMSTAR, review articles primarily exhibit weak systematic methodology, lower quality, high risks of bias, and thus are more narrative in character (eTable 6).

eTable 5. Quality assessment of survey studies on analgesic use in high-performance and amateur sport.

| Study (reference) | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total (max. 9) |

| Aavikko et al. (2013) (17) | **** | ** | * | 7 |

| Alaranta et al. (2006) (18) | **** | ** | * | 7 |

| Broman et al. (2017) (20) | **** | * | * | 6 |

| Brune et al. (2009) (22) | ** | * | 3 | |

| Chlíbková et al. (2018) (24) | ** | * | 3 | |

| Didier et al. (2017) (27) | **** | * | * | 6 |

| Dietz et al. (2016) (28) | **** | ** | * | 7 |

| Dowse et al. (2011) (29) | **** | * | * | 6 |

| Gorski et al. (2011) (30) | ** | * | 3 | |

| Hoffmann and Fogard (2011) (32) | **** | * | * | 6 |

| Holmes et al. (2013) (34) | * | * | 2 | |

| Joslin et al. (2013) (35) | ** | * | 3 | |

| Küster at al. (2013) (38) | **** | ** | * | 7 |

| Lai-Cheung-Kit et al. (2019) (39) | **** | * | * | 6 |

| Mahn et al. (2018) (40) | **** | ** | * | 7 |

| Martínez et al. (2017) (e1) | **** | * | * | 6 |

| Pardet et al. (2017) (e5) | **** | * | * | 6 |

| Rosenbloom et al. (2020) (e7) | **** | * | * | 6 |

| Rossi et al. (2021) (e8) | **** | ** | * | 7 |

| Rotunno et al. (2018) (e9) | **** | ** | * | 7 |

| Rüther et al. (2018) (e10) | **** | * | * | 6 |

| Schneider et al. (2019) (e11) | **** | ** | * | 7 |

| Seifarth et al. (2019) (7) | **** | * | * | 6 |

| Taioli (2007) (e13) | **** | * | * | 6 |

| Whatmough et al. (2017) (e24) | ** | * | 3 |

Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for evaluating cohort studies:

The individual studies are scored for selection (representativeness of the exposed cohort and selection of the non-exposed cohort; ascertainment of exposure; demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study), comparability, and recording of exposure/endpoint (validity of the data provided [outcome], endpoint within a sufficient observation period, consideration of and control for missing data).

Where the risk of bias is low, one star is given; the maximum possible number of stars is nine (16).

eTable 4. Quality assessment of studies on analgesic use in professional and elite sport (data collection based on doping control forms).

| Study (reference) | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total (max. 9) |

| Corrigan and Kazlauskaz (2003) (26) | **** | * | ** | 7 |

| Kavukcu and Burgazli (2013) (36) | **** | * | ** | 7 |

| Oester et al. (2019) (e4) | **** | * | ** | 7 |

| Pedrinelli et al. (2015) (e6) | **** | * | ** | 7 |

| Trinks et al. (2021) (e14) | **** | ** | ** | 8 |

| Tscholl et al. (2008) (e15) | **** | * | ** | 7 |

| Tscholl et al. (2009) (9) | **** | ** | ** | 8 |

| Tscholl et al. (2010) (e16) | **** | ** | ** | 8 |

| Tscholl and Dvorak (2012) (e19) | **** | * | ** | 7 |

| Tsitsimpikou et al. (2009) (e20) | **** | * | ** | 7 |

| van Thuyne et al. (2008) (e21) | **** | * | ** | 7 |

| Vaso et al. (2015) (10) | **** | ** | ** | 8 |

Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for evaluating cohort studies:

The individual studies are scored for selection (representativeness of the exposed cohort and selection of the non-exposed cohort; ascertainment of exposure; demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study), comparability, and recording of exposure/endpoint (validity of the data provided [outcome], endpoint within a sufficient observation period, consideration of and control for missing data).

Where the risk of bias is low, one star is given; the maximum possible number of stars is nine (16).

Use of analgesics in professional and elite sport

The 12 studies selected included 48 977 DCFs collected at World Championships, Olympic Games, competitive events, or during training (Table 1, eTable 3). The DCFs asked questions about the consumption of analgesics and dietary supplements during the 72 hours or 7 days before the dope test or competition. In elite sports, NSAID use varies greatly from sport to sport, ranging in the selected studies from 2.8% in professional tennis to 54.2% in professional football (10, e21). In the 2014 Football World Cup, per match 30.6% of players took NSAIDs (10). Trinks et al. (2021) determined a 33% level of analgesic use in the top German football leagues (Men’s Bundesliga, 2nd Men’s Bundesliga, Men’s 3rd League, Women’s Bundesliga, Junior Bundesliga) (e14). Olympic athletes in other sports reported average rates of NSAID use of 11.1% to 25.6% (26, e20). A Belgian–Dutch study reported rates of NSAID use ranging from 2.8% (tennis) to 31.1% (volleyball) (e21).

Table 1. Summary of detailed literature analysis*.

| Study design/data collection method | Target groups | Number of studies | Prevalence intervals and range of findings on analgesic use | Main findings | Sources |

| Doping control forms | Professional/elite athletes | 12 | Competition runup 3 days 2.8% (tennis) to 54.2% (football) NSAIDs Up to 17.5% (football) other analgesics 2 studies reported 7-day prevalence | In elite sports, the use of analgesics is mostly widespread, variable, and often prophylactic. | 9, 10, 26, 36, e4, e6, e 14 e16, e19 e21 |

| Surveys | Professional/elite athletes High-performance athletes Amateur athletes | 25 | Competition day 3.1% (half-marathon) to 70% (ultra-marathon) NSAIDs 0.5% (half-marathon) to 17.4% (ultra-run) other analgesics | Data for analgesic use in recreational/high-performance sports are dominated by running. Prevalences range from low to very high consumption. Some of the use is prophylactic. Not every study records the use of other analgesics apart from NSAIDs. | 6, 7, 17, 18, 20, 24, 27–30, 32, 34, 35, 38–40, e1, e5, e7–e11, e13, e24 |

| Weekly prevalence 6.3% (half-marathon) to 50.4% (5-km run) NSAIDs Only one study reported other analgesics: 3.2% (half-marathon) and 5.4% (56-km run) | |||||

| 1-year prevalence 35.8% (ultra-marathon) to 92.6% (football) NSAIDs 7.8% (Olympics) to 64% (football) other analgesics | |||||

| Study design/data collection method | Target groups | Number of studies | Object | Main findings | Sources |

| Reviews | Professional/elite athletes High-performance athletes Amateur athletes | 18 | Narrative and selective literature reviews | Frequency of analgesic use, analgesic abuse, prophylactic use of analgesics, adverse drug reactions, hazards and risks of analgesic use. | 8, 19, 21–23, 25, e2, e3, e12, e17, e18, e22, e23 |

| Systematic literature reviews | 12, 31, 33, 37, e25 |

*See also eTables 3–6; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Use of analgesics in high-performance sport

The 25 survey studies and 18 reviews evaluated mostly focus on endurance athletes (for example, half-marathon, marathon, ultramarathon) in the nonprofessional setting (Table 1, eTable 6). Compared to professional and elite sports, these studies suggest a lower level of analgesic consumption in high-performance sports. Nevertheless, among survey studies, which have a lower risk of bias than reviews, there are clear differences between individual studies: while a 60.3% rate of NSAID use was reported in participants in a 112-km ultramarathon event (e1), and a 60.5% rate on race day in a 161-km run (32), Rotunno et al. (e9) found rates of race-related painkiller use ranging from 3.1% (half-marathon) to 9.2% (56-km run) among over 75 000 endurance-trained participants.

Apart from running, individual studies are available for football (e8, e13), basketball (e11), diving (29), mountain biking (24), and triathlon (7, 28, 30), among others. Here, NSAID consumption on race day ranges from 10% of participants in an ultra mountain bike race (24) to 47.4% in a triathlon competition (30).

Use of analgesics in amateur sport

In contrast to the study and data situation for professional and elite sports, in the heterogeneous amateur sports sector there is a lack of original studies and reviews giving a comprehensive and valid picture of the prevalence of painkiller use (Table 1, eTables 5– 6).

eTable 3c. Review articles on analgesic use in sport.

| Study (reference) | Object of study | Method | Systematic search | Selective search | PRISMA model | Information on analgesic group or substance class | Any discussion of adverse drug effects | |||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

| Alaranta et al. (2008) (19) | Medication use among athletes | Not described | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Berrsche and Schmitt (2022) (e25) | Analgesic use in young high-performance athletes | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Brune et al. (2008) (21) | Dangers of sport and analgesics | Not described | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Brune et al. (2009) (22) | Analgesic use in amateur and high-performance sport | Not described | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Brune et al. (2009) (23) | Painkillers: fatal use in amateur sport | Not described | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Ciocca (2005) (25) | Medications and supplements in athletes | Not described | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Graf-Baumann (2013) (8) | Abuse on the rise in sport – nothing happens without painkillers | Not described | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Harle et al. (2018) (31) | Pain medication management in elite athletes | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Holgado et al. (2018) (33) | Analgesic use in sport – pain modulation and performance enhancement | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Koes et al. (2018) (37) | NSAID use by athletes | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Leyk and Rüther (2021) (12) | Analgesic use in sport and in society | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Müller-Platz et al. (2011) (e2) | Doping and drug abuse in leisure and amateur sport | Not described | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Niederberger and Geisslinger (2016) (e3) | Analgesics in amateur sport | Not described | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Seidel (2015) (e12) | Medication abuse in runners and its consequences | Not described | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Tscholl (2014) (e17) | Use of NSAIDs in elite sport | Not described | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Tscholl et al. (2015) (e18) | NSAID use in professional football (FIFA World Cup tournaments) | Not described | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Warden (2009) (e22) | Prophylactic misuse and recommended use of NSAIDs by athletes | Not described | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Warden (2010) (e23) | Prophylactic analgesic use and risk/benefit analysis in sport | Not described | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Apart from some single studies, the literature predominantly reports figures from running or endurance sports (eTable 3). These sometimes originate from individual events and differ significantly as to the figures cited for painkiller consumption. According to Brune et al. (2009), for example, 61% of respondents took analgesics before the start of the Bonn half-marathon/marathon (6), whereas in the study by Mahn et al. (2018), which analyzed data from runners in the Hannover marathon, only 17% stated that they had ever taken painkillers before a marathon race (40).

In contrast, the results of Rüther et al. (2018) (e10) and of Leyk and Rüther (2021) (12) are based on data collected at more than 100 running events in the period from 2016 to 2020. More than 96% of the over 50 000 respondents selected the response options “never” or “rarely” when asked about the frequency of their use of pain medication in connection with sports (table 2). 2.1% of the athletes reported taking painkillers at least once a month, mainly for musculoskeletal complaints.

Table 2. Frequency of analgesic use by athletes (n = 54 184).

| Number n (%) [95% CI] | |||||||

| Never | Rarely | Once or moreper month | Once or more per week | Daily | No data | Totaln (%)* | |

| Men | 26 261 (81.3) [80.9; 81.7] |

4931 (15.3) [14.9; 15.7] |

448 (1.4) [1.3; 1.5] |

86 (0.3) [0.2; 0.3] |

36 (0.1) [0.1; 0.2] |

534 (1.7) [1.5; 1.8] |

32 296 (100) |

| Women | 16 663 (76.1) [75.6; 76.1] |

4370 (20.0) [19.4; 20.5] |

477 (2.2) [2.0; 2.4] |

69 (0.3) [0.2; 0.4] |

20 (0.1) [0.1; 0.2] |

289 (1.3) [1.2; 1.5]) |

21 888 (100) |

| Total | 42 924 (79.2) [78.9; 79.6] |

9301 (17.2) [16.8; 17.5] |

925 (1.7) [1.6; 1.8] |

155 (0.3) [0.2; 0.3] |

56 (0.1) [0.1; 0.1] |

823 (1.5) [1.4; 1.6] |

54 184 (100) |

*Any deviations from 100% are due to rounding effects; CI, confidence interval

To summarize, the systematic literature review concluded that there is no scientifically robust evidence for widespread use of analgesics in amateur sport (12, e10).

Discussion

Important limitations of this systematic literature review arise from the different forms of data collection used in the studies, the study types, and the heterogeneous study populations. The risks of limited representativeness and of bias are evaluated in eTables 4–6. In addition, significantly fewer studies are available for the wide and highly diverse field of amateur sport than for professional/elite and high-performance sport. It is virtually impossible to assess any changes over time in painkiller consumption.

The results of the systematic literature review show that the use of analgesics is widespread in professional/elite sport and, to some extent, also in ambitious high-performance sport. Both studies based on DCFs and survey studies show that in top-level national and international football, for example, about one in two and one in three players, respectively, regularly take painkillers (10, 11, e14, e26). Analgesic consumption varies obviously from sport to sport (eTable 3).

However, using analgesics does not necessarily mean misusing them, nor does it necessarily mean that they are being used in connection with the sport being practiced. DCFs give no information about any disease-related, sport-related, or prophylactic reasons for use. Even some survey studies did not ask whether the painkiller use was related to the sporting activity (eTable 3) (17, 18, 20, 28, 32, 34, e8, e13). On the other hand, studies that specifically asked about why painkillers were taken show that they were being used prophylactically (6– 8). This is well seen in endurance sports: The longer and more grueling a competition, the more frequently painkillers are taken in the runup to it. In ultra-endurance sport, this may be the case in 60.3% to 70% of all competitors (32, 35, e1). Even in the match-playing sports, analgesic use in the absence of symptoms cannot be ruled out (e11, e25). According to Schneider et al. (2019), 5% of high-performance players take analgesics in order to prevent pain. Apart from prophylactic use, up to 84% of young high-performance basketballers still report occasionally using analgesics (e11).

Findings on analgesic consumption in professional/elite sport cannot be simply extrapolated to the field of amateur sport. However, in regard to ambitious amateur sport there is a gray area, such as in endurance or ultra-endurance sports, where participants take analgesics more often. The extent of training and the energy expenditure of these amateurs are quite comparable to those of professional/elite athletes in ball sports or athletics (for example, in sprinting/throwing disciplines).

The results of the literature review show that there is no reliable evidence of widespread analgesic abuse in amateur sport. There is a lack of solid data from original studies and reviews on this question. Only two selective studies, whose data were collected as part of a large running event and which show methodological ambiguities, conclude that analgesics are widely used in endurance sports (up to 61%) (6, 38). This is in contrast to the findings of a South African study of over 70 000 runners, where the use of analgesics ranged from 3.6% of participants in a half-marathon to 16.4% in a 56-km race (e9).

The results of our own survey do not suggest that analgesics are widely used in amateur sport at present (12, e10): only 1.7% of participants took painkillers “one to several times per month” and 0.4% “weekly” or “daily” in connection with their sporting activities. Further analysis showed that health reasons predominated for the use of painkillers.

This brings the discussion to another aspect of the use of analgesics in sport, and that is the question of whether and to what extent analgesic use is indicated to enable exercise and training. For example, analgesics can certainly be beneficial in patients undergoing medical exercise therapy. However, adverse effects of analgesics can be made worse by physical activity, not only in patients under medical exercise therapy, but also in healthy athletes. For example, higher levels of exercise lead to a reduction in glomerular filtration rate in the kidney. Taking anti-inflammatory drugs increases the risk of chronic kidney disease and acute kidney failure.

Especially when it comes to preventive use of analgesics, it should be remembered that these substances suppress important warning signs (pain, infection-related raised temperature, etc.), thereby increasing the risk of serious illness (6, 8, 19, e12, e22, e23). Table 3 lists observed symptoms and diseases that have been reported in the literature to be connected with analgesic use in sport.

Given the widespread use of analgesics in society and in different parts of the world of sport, it is also worth noting at this point how omnipresent painkiller advertising is on television, in the print media, and, increasingly, in internet forums and through influencers. People are promised, among other things, appropriate and rapidly effective solutions for various types of pain. This can help to lead to a state of affairs where many people are careless about their use of painkillers, which in the form of nonprescription (over-the-counter) analgesics are easily accessible (e27). The freedom to self-medicate has been created by the law, which has obliged pharmaceutical manufacturers to provide comprehensive information in the form of package inserts. However, survey results show that important information about adverse drug effects and recommendations for use are still not well known (4). In addition to more targeted information, advertising restrictions could help to reduce the harmful use of painkillers in sport and in society at large (5).

Table 3a. Symptoms and diseases associated with analgesic use in sport (excluding musculoskeletal system).

| Organ system | Symptoms/diseases | Sources | Remarks |

| Blood | Anemia | 9, 22, 23, 40 | Especially with ASA use: „sports anemia“ common in endurance athletes; anemia increased by hematuria and hematochezia; bone marrow suppression described |

| Bleeding diathesis | 6, 7, 20, 22, 33, e3, e11 | Especially with ASA use: increased bleeding on injury, increased risk of compartment syndrome, delays in necessary surgery | |

| Thrombembolism | 37, 40 | Mechanical stress on platelets; increased elimination in spleen might lead to formation of larger platelets | |

| Electrolytes | E.g. hyponatremia | 6, 7, 24, 30, 32, 33, 35, 38, e1, e3, e5–e7, e9, e11, e23 | Risk of electrolyte imbalance, local muscle cramping, seizures, and cardiac arrhythmias |

| Skin | Urticaria, angioedema | 18, 26 | |

| Cardiovascular | Cardiovascular problems | 10, 24, 28, 33, 34, 38, 39, 40, e7, e9, e23 | No further details of symptoms in the literature cited |

| Hyper-/hypotension | 9, 20, 24, 34, e1, e11 | Pathogenesis via the kidneys is discussed | |

| Arrhythmias | 6, 22, e18 | More common in the presence of electrolyte imbalance (among other things) | |

| Heart failure | 37, e17 | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 7, 37, 38, e23 | ||

| Liver | Liver damage | 25, 33, 39, 40, e11, e14 | Because of its limited duration and strength of action, paracetamol is often overdosed |

| Lungs | Asthma/ bronchospasm | 18, 24, 26, 33, 40, e3, e8, e11, e20 | Bronchospasm and asthma attacks often triggered by ASA in particular, especially in athletes due of the increased prevalence of asthma |

| Gastrointestinal | GI symptoms | 10, 18–20, 23, 26, 28, 30, 32, 34, 37, 38, e1, e4, e6, e7, e9, e11, e12, e20, e22, e23 | No further details of symptoms in the literature cited |

| Nausea, vomiting | 33, 39, 40, e7 | Reduced perfusion due to redistribution during sport Prostaglandins reduced by analgesics Mechanical stress and NSAIDs lead to reduced barrier function and increased permeability (toxic bacterial products, loss of fluids/electrolytes/blood) |

|

| Diarrhea | 19, 33, 40, e7 | ||

| Stomach ache, gastritis | 9, 19, 30, 33, 38–40, e7, e17, e18, e23, e24 | ||

| GI bleeding | 6, 8, 10, 22, 23, 33, 38–40, e2, e5, e7, e9, e17, e18, e23 | ||

| Ulcer | 25, 33, 39, 40 | ||

| Kidneys | Altered renal function | 9, 10, 18–21, 26, 28, 30, 34, 35, 38, 39, e9, e11, e12, e24 | Reduced kidney perfusion due to redistribution during physical activity and prostaglandins reduced by NSAIDs Kidneys stressed by i ncreased accumulation of metabolites with frequent fluid deficit (sweating, losses via GI tract, reduced fluid intake) |

| Hematuria | 6, 22, 23, 38, 40, e2, e18 | ||

| Chronic kidney failure | 18, 23, 25, 33, e1, e4, e14 | ||

| Acute kidney failure | 6, 20, 22, 24, 26, 32, 33, 35, 37, 40, e3, e5, e7, e9 | ||

| Central nervouse system | Fatigue | 18, 19 | |

| Dizziness | 18, 19, 39, 40 |

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; GI, gastrointestinal; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Table 3b. Symptoms and diseases of the musculoskeletal system associated with analgesic use in sport.

| Organ system | Symptoms/diseases | Sources | Remarks |

| Ligaments | Poorer healing, increased elasticity | 18, 19, 25, e17, e22, e23 | Risk of premature return to training with inadequate mechanical load capacity, limited mobility, limited collagen synthesis |

| Joints | Cartilage injuries, arthritis | 19, 21, 33 | Risk of overuse/misuse due to decreased pain perception; faster progression of hip and knee osteoarthritis with NSAIDs has been described in the literature |

| Bones | Delayed healing | 9, 18–20, 25, 35, e4, e7, e9, e12, e15, e17–e19, e23 | NSAIDs have proven useful to prevent ossification after joint replacement; delayed bone healing after fracture has been discussed in the literature |

| Risk of stress fractures | 19, e7, e12 | NSAIDs affecting collagen and matrix synthesis may lead to decreased bone remodeling | |

| Muscles | Delayed healing/ recovery | 9, 10, 18, 19, 23, 33, 39, e9, e15–e18, e22, e23 | |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 24, 32, e5, e12 | ||

| Tendons | Delayed healing | 25, 35, e6, e9, e19, e22, e23 | Limited collagen synthesis |

NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

eTable 3b. Survey studies on analgesic use in high-performance sport and amateur sport.

| Study (reference) | Study population | Number (n) | Prevalence period | Point prevalence | Frequency of use | Use related to sport | Information on analgesic group or substance class | Any discussion of adverse drug effects | ||||

| Before competition/match day | On competition/match day | Yes | n.d. | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||

| Aavikko et al. (2013) (17) | Para-Olympic competitors (PA) Finnish Olympic competitors (OA) |

92 (PA) 372 (OA) |

7 days 12 months |

7-day prevalence (PA/OA): 16.3%/6.7% NSAIDs 8.7%/1.1% other analgesics 12-month prevalence (PA/OA): 34.8%/48.7% NSAIDs 16.3%/7.8% other analgesics |

X | X | X | |||||

| Alaranta et al. (2006) (18) | Finnish elite athletes in all fields (FSA) vs. reference persons in the general population (REF) | 446 (FSA) vs. 1 503 (REF) |

7 days 12 months |

7-day prevalence: 8.1% FSA NSAIDs Odds ratio FSA vs. REF: 3.6% of all athletes (P < 0.05) 1.8% skill sports 1.9% endurance sports 2.1% team sports 9.5% speed and power sports (p < 0.05) |

X | X | X | |||||

| Broman et al. (2017) (20) | Disability Football World Championships participants (Int. Blind Sport Assoc. Football WC & Int. Fed. Cerebral Palsy Football WC) | 242 | 48 h before the match | Analgesic use at least once during the tournament: 38.0% NSAIDs 23.0% other analgesics |

X | X | X | |||||

| Brune et al. (2009) (6) | Bonn Marathon runners | 1 024 | X | 61.0% analgesics before the start 11.0% for pain before the start |

X | X | X | |||||

| Chlíbková et al. (2018) (24) | Mountain bike race (MT) and ultra mountain bike race (UMT) participants | 63 MT68 UMT | X | 10.0 % NSAIDs | X | X | X | |||||

| Didier et al. (2017) (27) | Mountain ultramarathon runners | 163 (72 km) 134 (160 km) | 1 month before the run | X | 9.8% NSAIDs 6.7% other analgesics |

X | X | X | ||||

| Dietz et al. (2016) (28) | Triathlon competitorsLong/half distance Ironman European Championship in Germany | 2 987 | 12 months | 20.4% analgesics among users of doping substances 12.4% among nonusers of doping substances |

X | X | X | |||||

| Dowse et al. (2011) (29) | Divers | 531 | ≤6 h before dive | 57.0% analgesics (NSAIDs, paracetamol, etc.) | X | X | X | |||||

| Gorski et al. (2011) (30) | Triathlon competitors Ironman | 327 | 3 months | X | X | 59.6% NSAIDs 3-month-prevalence 25.5% on the day before the competition 17.9% immediately before the competition 47.4% during the competition |

X | X | X | |||

| Hoffmann and Fogard (2011) (32) | Ultramarathon runners (161 km) | 500 | X | Finishers (during the run): 60.5% NSAIDs 16.8% acetaminophen Nonfinishers (during the run): 46.4% NSAIDs 10.0% acetaminophen |

X | X | X | |||||

| Holmes et al. (2013) (34) | American college football players | 210 | Lifetime prevalence | X | 95.7% ever taken NSAIDs High consumption (usually and always): 10.9% before the game 32.7% after the game 5.2% before training 20.4% after training |

X | X | X | ||||

| Joslin et al. (2013) (35) | Desert Race ultramarathon runners Colorado to Utah (148 miles/6 days) and New York Marathon runners | 27 (ultramarathon)46 (marathon) | X | NSAIDs ultramarathon vs. marathon runners: 59% vs. 63% training 70% vs. 26% during the run 59% vs. 61% recovery period Acetaminophen ultramarathon vs. marathon runners: 26% vs. 15% training 11% vs. 11% during the run 11% vs. 17% recovery period Diclofenac ultramarathon vs. marathon runners: 19% vs. 4% training 7% vs. 2% during the run 4% vs. 4% recovery period |

X | X | X | |||||

| Küster at al. (2013) (38) | Bonn Marathon runners | 3913 | X | 49% analgesic users vs. 51% non–analgesic users 20% users of analgesics during competition use analgesics during training |

X | X | X | |||||

| Lai-Cheung-Kit et al. (2019) (39) | Participants in Réunion Le Grand Raid ultrarun (167 km) | 1142 | 1-year prevalence | 35.8% used an NSAID at least once | X | X | X | |||||

| Mahn et al. (2018) (40) | Hannover Marathon runners | 655 | 17% ever used an analgesic before the start of this marathon or another one | X | X | X | ||||||

| Martínez et al. (2017) (e1) | Mallorca Mountain Race ultramarathon runners | 58 (112 km) 118 (67 km) 62 (44 km) |

X | NSAIDs before, during, and after competition: 60.3% ultramarathon 49.2% trail run 35.5% marathon |

X | X | X | |||||

| Pardet et al. (2017) (e5) | Participants in Le Grand Raid ultrarun (64 km-163 km) | 1691 | X | NSAIDs: 5.8% preparation period 6.5% during competition Other analgesics 6.5% preparation period 17.4% during competition |

X | X | X | |||||

| Rosenbloom et al. (2020) (e7) | UK parkrun participants (5 km) | 806 | 1-year prevalence 1-week prevalence | NSAIDs: 88% within 1 year 50.4% within the last 1–7 days |

X | X | X | |||||

| Rossi et al. (2021) (e8) | Professional footballers 2nd league, Italy | 378 | 1-year prevalence | 91.8% NSAIDs 64% other analgesics >30 days/year: 35.7% NSAIDs 21.8% other analgesics |

X | X | X | |||||

| Rotunno et al. (2018) (e9) | Run participants, South Africa | 47 069 (21.1 km) 29 585 (56 km) |

1-week prevalence | X | Week before the run: NSAIDs: 6.3% (21.1 km) 12.8% (56 km) Other analgesics: 3.2% (21.1 km) 5.4% (56 km) During the run: NSAIDs: 3.1% (21.1 km) 9.2% (56 km) Other analgesics: 0.5% (21.1 km) 7.2% (56 km) |

X | X | X | ||||

| Rüther et al. (2018) (e10) | City run participants (nationwide, up to marathon distance) | 15 454 | Prevalence per day/week/month | Analgesic use: 0.1% daily 0.3% once or more/week 1.8% once or more/month 17.2% rarely 80.5% never |

X | X | X | |||||

| Schneider et al. (2019) (e11) | Basketballers (junior athletes 13–19 years) | 182 | At least 1 analgesic: 40.1% often 84.1% occasionally Prefer NSAIDs: 13.0% used in the absence of pain 4.9% prophylactically |

X | X | X | ||||||

| Seifarth et al. (2019) (7) | Triathlon competitors, super-sprint to long-distance | 1989 | 3 months | 11.3% analgesics Prophylactic/therapeutic use: 2.0%/4.7% training 3.6%/3.5% competition |

X | X | X | |||||

| Taioli (2007) (e13) | Professional footballers 1st and 2nd league, Italy | 743 | Prevalence per day/month/year | NSAIDs/year: 92.6% chronic users 86.1% current users Other analgesics/year 36.0% chronic users 32.7% current users |

X | X | X | |||||

| Whatmough et al. (2017) (e24) | Marathon runners London | 109 | X | NSAIDs: 34.1% before the run 45.9% planned to take during the run Out of 28 participants asked, 57.1% reported having taken a NSAID at the end of the run |

X | X | X | |||||

n.d., no data; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

eTable 6. Quality assessment of review articles on analgesic use in sport.

| Study (reference) | 1. Was the review planned/defined a priori? | 2. Were study selection and data extraction performed by two individuals independently? | 3. Was a comprehensive and systematic literature search performed? | 4. Were unpublished study data and gray literature included in the review? | 5. Did the review provide a a list of the studies included and excluded? | 6. Were the study characteristics (characteristics of patients, interventions, and endpoints) of the included studies reported either in table format or in detail in the text? | 7. Was the risk of bias of the included primary studies assessed according to established methods? | 8. Was the risk of bias of the included studies taken into account in the interpretation of the review findings? | 9. Was the statistical analysis of the study results appropriate? | 10. Was the potential for publication bias addressed? | 11. Were conflicts of interest addressed? |

| Alaranta et al.(2008) (19) | No | No | No | Unclear | No | No | No | No | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Berrsche and Schmitt (2022) (e25) | Yes | No | No | Unclear | No | Unclear | No | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Brune et al. (2008) (21) | No | No | No | Unclear | No | Unclear | No | No | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Brune et al. (2009) (22) | No | No | No | Unclear | No | Unclear | No | No | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Brune et al. (2009) (23) | No | No | No | Unclear | No | Unclear | No | No | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Ciocca (2005) (25) | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | No | No | No | No | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Graf-Baumann (2013) (8) | No | No | No | Unclear | No | Unclear | No | No | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Harle et al. (2018) (31) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Holgado et al. (2018) (33) | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | No | No | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Koes et al. (2018) (37) | Unclear | No | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | No | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Leyk and Rüther (2021) (12) | Unclear | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | No | No | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Müller-Platz et al. (2011) (e2) | No | No | No | Unclear | No | Yes | No | No | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Niederberger and Geisslinger (2016) (e3) | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Seidel (2015) (e12) | No | No | No | Unclear | No | No | No | No | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Tscholl (2014) (e17) | No | No | No | Unclear | No | No | No | No | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Tscholl et al. (2015) (e18) | No | No | No | Unclear | No | Yes | No | No | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Warden (2009) (e22) | No | No | No | Unclear | No | No | No | No | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Warden (2010) (e23) | No | No | No | Unclear | No | Unclear | No | No | Not applicable | Not applicable | Unclear |

AMSTAR, a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews (15)

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Our thanks go to our IT specialist, Michael Trunzler, for his excellent programming work in the ActIv project. We thank Matthias Krapick, medical documentalist, for his valuable contributions to the systematic literature search, data preparation, and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. Vits holds shares in Sanofi S. A. and Zur Rose Group AG.

The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Atzendorf J, Rauschert C, Seitz N-N, Lochbühler K, Kraus L. The use of alcohol, tobacco, illegal drugs and medicines: an estimate of consumption and substance-related disorders in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl. 2019;116:577–584. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (BfArM) International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (ICD-11 MMS) Entwurfsfassung: ICD-11 MMS. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften e. V. (AWMF) S3-Leitlinie Medikamentenbezogene Störungen (AWMF-Register-Nr.: 038-025) www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/038-025l_S3_Medikamtenbezogene-Stoerungen_2021-01.pdf (last accessed on 21 April 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert Koch-Institut. Robert Koch-Institut. Berlin: 2015. Anwendung rezeptfreier Analgetika in Deutschland. Eine Befragungsstudie zum Anwendungsverhalten, zur Kenntnis von Anwendungsinformationen und Bewertung eines möglichen Packungsaufdrucks in der erwachsenen Allgemeinbevölkerung. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heinz A, Liu S. Addiction to legal drugs and medicines in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:575–576. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brune K, Niederweis, Kaufmann A, Küster-Kaufmann M. Analgetikamissbrauch bei Marathonläufern. Jeder Zweite nimmt vor dem Start ein Schmerzmittel. MMW Fortschr Med. 2009;151:39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seifarth S, Dietz P, Disch AC, Engelhardt M, Zwingenberger S. The prevalence of legal performance-enhancing substance use and potential cognitive and or physical doping in German recreational triathletes, assessed via the randomised response technique. Sports. 2019;7 doi: 10.3390/sports7120241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graf-Baumann T. Missbrauch im Sport nimmt zu „Ohne Schmerzmittel läuft nichts“. MMW Fortschr Med. 2013;155:62–64. doi: 10.1007/s15006-013-0892-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tscholl P, Feddermann N, Junge A, Dvorak J. The use and abuse of painkillers in international soccer: data from 6 FIFA tournaments for female and youth players. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:260–265. doi: 10.1177/0363546508324307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaso M, Weber A, Tscholl PM, Junge A, Dvorak J. Use and abuse of medication during 2014 FIFA World Cup Brazil: a retrospective survey. BMJ Open. 2015;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007608. e007608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CORRECTIV, ARD Dopingredaktion. Pillenkick. Schmerzmittelmissbrauch im Fußball. https://correctiv.org/top-stories/2020/06/08/pillenkick/ (last accessed on 5 April 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leyk D, Rüther R. Schmerzmittelkonsum im Sport und in der Gesellschaft Ausgewählte Fakten zur öffentlichen Anhörung des Sportausschusses des Deutschen Bundestages am 27.01.2021. www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/818272/cf51d57bc44da349429bd368106e3cc1/20210127-Leyk-data.pdf (last accessed on 14 February 2023) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. Br Med J. 2009;339:1–27. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ziegler A, Antes G, König I. Bevorzugte Report Items für systematische Übersichten und Meta-Analysen: Das PRISMA-Statement. Dtsch med Wochenschr. 2011;136:e9–e15. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmucker C, Nothacker M, Möhler R, Kopp I, Meerpohl J. Bewertung des Verzerrungsrisikos von systematischen Übersichtsarbeiten: ein Manual für die Leitlinienerstellung. www.cochrane.de/de/review-bewertung-manual (last accessed on 1 February 2023) 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmucker C, Nothacker M, Rücker G, Muche-Borowski C, Kopp I, Meerpohl J. Bewertung des Biasrisikos (Risiko systematischer Fehler) in klinischen Studien: ein Manual für die Leitlinienerstellung. www.cochrane.de/sites/cochrane.de/files/uploads/manual_biasbewertung.pdf (last accessed on 1 February 2023) 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aavikko A, Helenius I, Vasankari T, Alaranta A. Physician-prescribed medication use by the Finnish paralympic and olympic athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2013;23:478–482. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31829aef0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alaranta A, Alaranta H, Heliövaara M, Airaksinen M, Helenius I. Ample use of physician-prescribed medications in Finnish elite athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2006;27:919–925. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-923811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alaranta A, Alaranta H, Helenius I. Use of prescription drugs in athletes. Sports Med. 2008;38:449–463. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broman D, Ahmed OH, Tscholl PM, Weiler R. Medication and supplement use in disability Football World Championships. PM R. 2017;9:990–997. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brune K, Niederweis U, Krämer BK. Unheilige Alianz zum Schaden der Niere. Dtsch Arztebl. 2008;105:1894–1897. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brune K, Niederweis U, Küster M, Renner B. Laien- und Leistungssport: Geht nichts mehr ohne Schmerzmittel? Dtsch Arztebl. 2009;106:2302–2304. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brune K, Niederweis U, Küster-Kaufmann M. Schmerzmittel - fataler Einsatz im Breitensport. DAZ. 2009;149:68–73. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chlíbková D, Ronzhina M, Nikolaidis PT, Rosemann T, Knechtle B. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug consumption in a multi-stage and a 24-h mountain bike competition. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ciocca M. Medication and supplement use by athletes. Clin Sports Med. 2005;24:719–738. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2005.03.005. x-xi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corrigan B, Kazlauskas R. Medication use in athletes selected for doping control at the Sydney Olympics (2000) Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13:33–40. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Didier S, Vauthier J-C, Gambier N, Renaud P, Chenuel B, Poussel M. Substance use and misuse in a mountain ultramarathon new insight into ultrarunners population? Res Sports Med. 2017;25:244–251. doi: 10.1080/15438627.2017.1282356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dietz P, Dalaker R, Letzel S, Ulrich R, Simon P. Analgesics use in competitive triathletes its relationship to doping and on predicting its usage. J Sports Sci. 2016;34:1965–1969. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2016.1149214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dowse MSL, Cridge C, Smerdon G. The use of drugs by UK recreational divers: prescribed and over-the-counter medications. Diving Hyperb Med. 2011;41:16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorski T, Cadore EL, Pinto SS, et al. Use of NSAIDs in triathletes: prevalence, level of awareness and reasons for use. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:85–90. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.062166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harle CA, Danielson EC, Derman W, et al. Analgesic management of pain in elite athletes: a systematic review. Clin J Sport Med. 2018;28:417–426. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoffman MD, Fogard K. Factors related to successful completion of a 161-km ultramarathon. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2011;6:25–37. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.6.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holgado D, Hopker J, Sanabria D, Zabala M. Analgesics and sport performance: beyond the pain-modulating effects. PM R. 2018;10:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmes N, Cronholm PF, Duffy AJ, Webner D. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in collegiate football players. Clin J Sport Med. 2013;23:283–286. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318286d0fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joslin J, Lloyd JB, Kotlyar T, Wojcik SM. NSAID and other analgesic use by endurance runners during training, competition and recovery. S Afr J Sports Med. 2013;25 101 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kavukcu E, Burgazlı KM. Preventive health perspective in sports medicine: the trend at the use of medications and nutritional supplements during 5 years period between 2003 and 2008 in football. Balkan Med J. 2013;30:74–79. doi: 10.5152/balkanmedj.2012.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koes B, van Ochten J, van Middelkoop M. NSAIDs use in athletes. Dansk Sportmedicin. 2018;22:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Küster M, Renner B, Oppel P, Niederweis U, Brune K. Consumption of analgesics before a marathon and the incidence of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and renal problems: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lai-Cheung-Kit I, Lemarchand B, Bouscaren N, Gaüzère B-A. Consommation des anti-inflammatoires non stéroïdiens lors de la préparation au Grand Raid 2016 à La Réunion. Science & Sports. 2019;34:244–258. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahn A, Flöricke F, Sieg L, et al. Consumption of analgesics before a marathon and effects on incidence of adverse events: the Hannover marathon study. IJAR. 2018;6:1430–1441. [Google Scholar]

- E1.Martínez S, Aguiló A, Moreno C, Lozano L, Tauler P. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs among participants in a mountain ultramarathon event. Sports. 2017;5 doi: 10.3390/sports5010011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Müller-Platz C, Symanzik T, Lütkehermölle R, Müller RK, Boos C. Doping und Arzneimittelmissbrauch im Freizeit- und Breitensport. Internistische Praxis. 2011;51:173–191. [Google Scholar]

- E3.Niederberger E, Geisslinger G. Analgetika im Breitensport. Pharmakon. 2016;4:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- E4.Oester C, Weber A, Vaso M. Retrospective study of the use of medication and supplements during the 2018 FIFA World Cup Russia. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2019;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000609. e000609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Pardet N, Lemarchand B, Gaüzère B-A. Ultra-trailers’ consumption of medicines and dietary supplements, about the grand raid 2015 // La prise de médicaments et de compléments alimentaires chez l’ultra-trailer compétiteur durant la préparation du Grand Raid 2015 de l’île de La Réunion. Science & Sports. 2017;32:344–354. [Google Scholar]

- E6.Pedrinelli A, Ejnisman L, Fagotti L, Dvorak J, Tscholl PM. Medications and nutritional supplements in athletes during the 2000, 2004, 2008, and 2012 FIFA Futsal World Cups. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2015/870308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Rosenbloom CJ, Morley FL, Ahmed I, Cox AR. Oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in recreational runners participating in Parkrun UK: prevalence of use and awareness of risk. Int J Pharm Pract. 2020;28:561–568. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Rossi FW, Napolitano F, Pucino V, et al. Drug use and abuse and the risk of adverse events in soccer players: results from a survey in Italian second league players. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;53:37–42. doi: 10.23822/EurAnnACI.1764-1489.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Rotunno A, Schwellnus MP, Swanevelder S, Jordaan E, van Janse Rensburg DC, Derman W. Novel factors associated with analgesic and anti-inflammatory medication use in distance runners: pre-race screening among 76 654 race entrants-SAFER Study VI. Clin J Sport Med. 2018;28:427–434. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Rüther T, Witzki A, Schomaker R, Löllgen H, Rohde U, Leyk D. Konsum von NEM und Schmerzmitteln bei Läufern - Ergebnisse des „Bleib-gesund-und-werde-fit“-Surveys. Dtsch Z Sportmed. 2018;69 [Google Scholar]

- E11.Schneider S, Sauer J, Berrsche G, Löbel C, Sommer DK, Schmitt H. [Joint pain and consumption of analgesics among young elite athletes nationwide data from youth basketball] Schmerz. 2019;33:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s00482-018-0309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Seidel EJ. Medikamentenmissbrauch bei Läufern und die Folgen. Manuelle Medizin. 2015;53:205–208. [Google Scholar]

- E13.Taioli E. Use of permitted drugs in Italian professional soccer players. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:439–441. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.034405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Trinks S, Scheiff AB, Knipp M, Gotzmann A. Declaration of analgesics on doping control forms in German football leagues during five seasons. Dtsch Z Sportmed. 2021;72:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- E15.Tscholl P, Junge A, Dvorak J. The use of medication and nutritional supplements during FIFA World Cups 2002 and 2006. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42:725–730. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.045187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Tscholl P, Alonso JM, Dollé G, Junge A, Dvorak J. The use of drugs and nutritional supplements in top-level track and field athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:133–140. doi: 10.1177/0363546509344071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Tscholl PM. Der Einsatz von nicht-steroidalen Antirheumatika (NSAR) im Spitzensport. Dtsch Z Sportmed. 2014;65:34–37. [Google Scholar]

- E18.Tscholl PM, Vaso M, Weber A, Dvorak J. High prevalence of medication use in professional football tournaments including the World Cups between 2002 and 2014: a narrative review with a focus on NSAIDs. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:580–582. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Tscholl PM, Dvorak J. Abuse of medication during international football competition in 2010—lesson not learned. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:1140–1141. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Tsitsimpikou C, Tsiokanos A, Tsarouhas K, et al. Medication use by athletes at the Athens 2004 Summer Olympic Games. Clin J Sport Med. 2009;19:33–38. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31818f169e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.van Thuyne W, Delbeke FT. Declared use of medication in sports. Clin J Sport Med. 2008;18:143–147. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318163f220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Warden SJ. Prophylactic misuse and recommended use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs by athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:548–549. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.056697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Warden SJ. Prophylactic use of NSAIDs by athletes: a risk/benefit assessment. Physician Sportsmed. 2010;38:132–138. doi: 10.3810/psm.2010.04.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Whatmough S, Mears S, Kipps C. The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) at the 2016 London marathon. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51 [Google Scholar]

- E25.Berrsche G, Schmitt H. Schmerzprävalenzen und Analgetikakonsum bei Nachwuchsleistungsportlern - ein aktueller narrativer Überblick. Dtsch Z Sportmed. 2022;73:93–97. [Google Scholar]

- E26.Seppelt H, Löer W, Sachse J. Neue Studie im Profifußball: Schmerzmittel bei jeder dritten Dopingkontrolle. https://correctiv.org/aktuelles/fussballdoping/ 2021/03/08/neue-studie-im-profifussball-schmerzmittel-bei-jeder-dritten-dopingkontrolle/ (last accessed on 1 February 2023) [Google Scholar]

- E27.Schmitt H. Wieviel Schmerz ist erlaubt? Dtsch Z Sportmed. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- E28.Rauschert C, Möckl J, Seitz NN, Wilms N, Olderbak S, Kraus L. The use of psychoactive substances in Germany—findings from the Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse 2021. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2022;119:527–534. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.m2022.0244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]