Abstract

Introduction

To assess outcome of a one‐time human papillomavirus (HPV)‐screening in 2017 of Danish women aged 70+.

Material and methods

Women born 1947 or before were personally invited to have a cell‐sample collected by their general practitioner. Screening‐ and follow‐up samples were analyzed in hospital laboratories in the five Danish regions and registered centrally. Follow‐up procedures varied slightly across regions. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 (CIN2) was recommended treatment threshold. Data were retrieved from the Danish Quality Database for Cervical Cancer Screening. We calculated CIN2+ and CIN3+ detection rates per 1000 screened women, and number of biopsies and conizations per detected CIN2+ case. We tabulated annual number of incident cervical cancer cases in Denmark for the years 2009–2020.

Results

In total, 359 763 women were invited of whom 108 585 (30% of invited) were screened; 4479 (4.1% of screened, and 4.3% of screened 70–74 years) tested HPV‐positive; of whom 2419 (54% of HPV‐positive) were recommended follow‐up with colposcopy, biopsy and cervical sampling, and 2060 with cell‐sample follow‐up. In total, 2888 women had histology; of whom 1237 cone specimen and 1651 biopsy only. Out of 1000 screened women 11 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 11–12) had conization. In total, 579 women had CIN2+; 209 CIN2, 314 CIN3, and 56 cancer. Out of 1000 screened women five (95% CI: 5–6) had CIN2+. Detection rate of CIN2+ was highest in regions where conization was used as part of first‐line follow‐up. In 2009–2016, number of incident cervical cancers in women aged 70+ in Denmark fluctuated around 64; in 2017 it reached 83 cases; and by 2021 the number had decreased to 50.

Conclusions

The prevalence of high‐risk HPV of 4.3% in women aged 70–74 is in agreement with data from Australia, and the detection of five CIN+2 cases per 1000 screened women is in agreement with data for 65–69 year old women in Norway. Data are thus starting to accumulate on primary HPV‐screening of elderly women. The screening resulted in a prevalence peak in incident cervical cancers, and it will therefore take some years before the cancer preventive effect of the screening can be evaluated.

Keywords: cervical cancer, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, conization, human papillomavirus, screening

An offer of cervical screening was well received by elderly women in Denmark. Out of 1000 screened women, five had CIN2+ detected. Screening resulted in a prevelance peak of cervical cancers. It will therefore take some years before the cancer preventive effect of the screening can be evaluated.

Abbreviations

- CBC

colposcopy, biopsy and cervical sampling

- CI

confidence interval

- CIN

cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- RR

relative risk

Key message.

In one‐time HPV‐screening in elderly Danish women, 4.1% of women were HPV‐positive, and 0.5% had CIN2+ detected, but more than twice as many had conization.

1. INTRODUCTION

In Denmark, as in several other high‐income countries, the current age‐specific incidence of cervical cancer is bipolar with a first peak around the age of 35 years and a second peak around the age of 80 years. The second peak has been hypothesized to be related to reactivation of latent human papillomavirus (HPV) as the immune system degenerates with increasing age and/or with new HPV‐infections resulting from new sexual relationships in middle aged women. 1 Demography is a third possible explanation, as women presently in older age have not been screened systematically for precancerous cervical lesions while they were younger. 2

Cervical screening started countywide in Denmark in the late 1960s. Since 2007, all women in Denmark aged 23–64 years have been offered cytology screening every third year from 23 to 49 years, and every fifth year thereafter. From 2012 onwards, the cytology screening from age 60 and above was replaced by an HPV check‐out test. A pilot study on primary HPV‐screening for women aged 30–59 is ongoing. Screening is free of charge and organized with personal invitation to all women in the target age‐group. However, in 2011–2016 one fourth of the cervical cancer cases, and half of the deaths from cervical cancer occurred in women 65 years and older. 3 This led to a request from patient‐ and elderly people's organizations for an increase in the upper age‐limit for cervical screening.

The problem was considered by the Danish Health Authority. Following the argument that demography was the most likely explanation for the second peak in incidence, it was decided to offer the currently elderly women a one‐time screening‐test. In 2017, all women born in 1947 or earlier were therefore personally invited to have a screening sample taken by their general practitioner. Samples were HPV‐tested to maximize sensitivity.

Women responded positively to the screening initiative, as 30% of these 70+ aged women participated. In total, 4.1% of participating women tested high‐risk HPV‐positive, with the prevalence decreasing slightly with increasing age. 4 As planned, the histology outcome was reported after end of the recommended follow‐up period. 5 , 6 , 7 However, it turned out that follow‐up periods had been longer than anticipated. We therefore updated the follow‐up with two more years of observations and report on both benefit and harm. As cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN2) was the threshold for treatment of CIN in postmenopausal women in Denmark, 8 we used detected cases of CIN2+ as the main measure for outcome of the intervention. Finally, we report on the impact so far on the national cervical cancer incidence.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

Organization of the one‐time screening of elderly women in Denmark has been described in detail before. 4 In brief, during 2017 women were personally invited to have a cell‐sample collected by their general practitioner, samples were analyzed region‐wise at the hospital pathology laboratories, and all data were collected in the national Pathology Data Bank. For definition of target population, see Figure 1. The follow‐up strategy differed somewhat across regions, Table 1. Most noteworthy, in the Capital Region all high‐risk HPV‐positive women were referred directly for colposcopy, biopsy and cervical sampling (CBC). In other regions only women HPV16/18‐positive or positive with other high‐risk HPV combined with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance and worse (ASCUS+) in cytology triage were referred directly for CBC, while women positive for other high‐risk HPV and with normal cytology were recommended repeated testing after 12 months.

FIGURE 1.

Eligible population for the one‐time primary HPV‐screening of elderly women in Denmark in 2017.

TABLE 1.

Organization of cervical screening for women aged 70 and above in Denmark in 2017 by region.

| Activity | Region a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | Central | South | Zealand | Capital | |

| HPV‐assay | Cobas 4800© | Cobas 4800© | Cobas 4800© | Cobas 4800© | BD Onclarity© |

| Result reported | HPV 16, 18, other b , negative | HPV 16, 18, other b , negative | HPV 16, 18, other b , negative | HPV 16,18, other b , negative | HPV 16, 18, other b , negative |

| Cytology triage | Other only | Other only | Other only | Other only | None |

| Referral for CBC c | 16+, 18+, (other+ with ASCUS+ d ), sometimes first‐line conization | 16+, 18+, (other+ with ASCUS+ d ) | 16+, 18+, (other+ with ASCUS+ d ) | 16+, 18+, (other+ with ASCUS+ d ) | All HPV+ sometimes first‐line conization |

| Repeated testing after 12 months | Other+ and normal cytology | Other+ and normal cytology | Other+ and normal cytology | Other+ and normal cytology | Not relevant |

| Type of repeated test | Cytology + HPV | Cytology + HPV | Cytology + HPV | HPV | Not relevant |

| Referral to CBC c | All HPV+ and/or ASCUS+ d , sometimes first‐ line conization | 16+, 18+ and/or ASCUS+ d | All HPV+ and/or ASCUS+ d | All HPV+ | Not relevant |

| Repeated testing after 12 months | Not relevant | Other+ and normal cytology | Not relevant | Not relevant | Not relevant |

| Terminated | HPV‐negative and cytology normal | HPV‐negative and cytology normal | HPV‐negative and cytology normal | HPV‐negative | Histology normal |

Full names of regions: The North Denmark Region, The Central Denmark Region, The Region of Southern Denmark, Region Zealand, The Capital Region of Denmark. For short: Region North, Central Region, Region South, Region Zealand, Capital Region.

Other high‐risk HPV‐types than 16 and 18.

CBC Colposcopy, biopsy, and cervical sampling. In Region North, Central Region, Region South, and Region Zealand cervical sampling was endocervical cell‐sampling, in Capital Region it was endocervical curettage.

Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance and worse.

Repeated testing was performed with HPV‐test and cytology in Region North, the Central Region, and Region South, but with HPV‐test only in Region Zealand. At repeated testing in Region North, Region South, and Region Zealand, women were referred for CBC if they were HPV‐positive or had abnormal cytology. If neither of these findings occurred, follow‐up was terminated. The same scheme was used in the Central Region, but women HPV‐positive only for other types than HPV 16/18 and with normal cytology were recommended an extra follow‐up after 12 months. Due to shortage of gynecologists in Region North, some women at referral for CBC had first‐line conization. In the Capital Region, some gynecologists also used first‐line conization for women with an atrophic cervix uteri.

We registered all follow‐up in terms of screens, biopsies and conizations over an approximate four‐year period from start of screening during 2017 to mid‐October 2021. As follow‐up data were retrieved from the Pathology Data Bank, a conization was defined as a cone specimen. HPV‐test was classified as HPV‐positive (including only high‐risk types) or negative, HPV16/18 or other HPV‐types only. Biopsies and cone specimens were classified as less than CIN2, CIN2 (including CIN unclassified), CIN3 (including adenocarcinoma in situ), or cancer. According to Danish guidelines, CIN2 was the treatment threshold for postmenopausal women 8 and loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) is used for conization.

For Denmark in total and for each of the five regions, we report on number of women invited, screened, HPV‐positive, HPV16/18, other HPV positive, having histology, conization, CIN2+, CIN3+, or cancer. For the years 2009–2021 we report on annual number of incident cervical cancer cases for women aged 70 and above. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4. Tabulated, anonymized incidence data on cervical cancer by 5‐year age‐groups for the years 2009–2021 were provided by eSundhed (Personal communication, Danish Health Data Authority, 18 October 2022 and 30 January 2023).

2.1. Ethics statement

Data were provided by the Danish Clinical Quality Program, National Clinical Registers via the Danish Quality Database for Cervical Cancer Screening. The key data source in this quality program is the Pathology Data Bank. This study was part of routine quality assurance of the Danish Cervical Screening Program. The Central Region guaranteed that data were used in accordance with the data protection legislation. In Denmark, ethical approval is not required for research projects based exclusively on register data.

3. RESULTS

In this one‐time screening, 359 763 elderly eligible women were invited and 108 585 (30%) participated, Figure 1. There were limited regional differences in participation with rates between 29% and 31% for the five regions, Table 2. HPV was detected in screening tests for 4479 women, 4.1%, ranging from 3.4% in Region South to 4.8% in the Central Region. Overall, 24% of the HPV‐positive women were positive for HPV16/18, and 76% were positive for other HPV‐types only, and similar distributions were seen for the regions, except for the Capital Region where 20% of the samples were positive for HPV16/18 and 80% positive for other HPV only. These regional differences were probably explained by different assays with BD Onclarity© used in the Capital Region and Cobas4800© elsewhere, Table 1.

TABLE 2.

Outcome of cervical screening for women aged 70 and above in Denmark in 2017 by region. Follow‐up including October 2021.

| Region | Denmark | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | Central | South | Zealand | Capital | ||

| Number | ||||||

| Invited women | 39 143 | 75 937 | 81 273 | 58 459 | 104 951 | 359 763 |

| Screened women, n (% of invited) | 11 414 (29%) | 23 654 (31%) | 25 212 (31%) | 17 807 (30%) | 30 498 (29%) | 108 585 (30%) |

| HPV‐positive, n (% of screened) | 512 (4.5%) | 1130 (4.8%) | 855 (3.4%) | 736 (4.1%) | 1246 (4.1%) | 4479 (4.1%) |

| HPV16/18, n (% of positive) | 133 (26%) | 284 (25%) | 219 (26%) | 190 (26%) | 243 (20%) | 1069 (24%) |

| HPVother/unknown, n (% of positive) | 379 (74%) | 846 (75%) | 636 (74%) | 546 (74%) | 1003 (80%) | 3410 (76%) |

| Any histology (% of screened) | 326 (2.9%) | 505 (2.1%) | 481 (1.9%) | 508 (2.9%) | 1068 (3.5%) | 2888 (2.7%) |

| Conization (% of screened) | 238 (2.1%) | 184 (0.8%) | 166 (0.7%) | 164 (0.9%) | 485 (1.6%) | 1237 (1.1%) |

| CIN2+ | 66 | 112 | 113 | 90 | 198 | 579 |

| CIN3+ | 50 | 76 | 87 | 53 | 104 | 370 |

| Cancer | 5 | 10 | 20 | 7 | 14 | 56 |

| Detection rates for CIN2+ per 1000 | ||||||

| CIN2+/screened | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 |

| CIN2+/HPV+ | 129 | 99 | 132 | 122 | 159 | 129 |

| CIN2+/histology | 202 | 222 | 235 | 177 | 185 | 200 |

| CIN2+/conization | 277 | 609 | 681 | 549 | 408 | 468 |

| Detection rates for CIN3+ per 1000 | ||||||

| CIN3+/screened | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| CIN3+/HPV+ | 98 | 67 | 102 | 72 | 83 | 83 |

| CIN3+/histology | 153 | 150 | 181 | 104 | 97 | 128 |

| CIN3+/conization | 210 | 413 | 524 | 323 | 214 | 299 |

| Number needed for CIN2+ detection | ||||||

| Screened/CIN2+ | 173 | 211 | 223 | 198 | 154 | 188 |

| HPV+/CIN2+ | 7.8 | 10.1 | 7.6 | 8.2 | 6.3 | 7.7 |

| Histology/CIN2+ | 4.9 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 5.0 |

| Conization/CIN2+ | 3.6 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.1 |

| Number needed for CIN3+ detection | ||||||

| Screened/CIN3+ | 228 | 311 | 290 | 336 | 293 | 293 |

| HPV+/CIN3+ | 10.2 | 14.9 | 9.8 | 13.9 | 12.0 | 12.1 |

| Histology/CIN3+ | 6.5 | 6.6 | 5.5 | 9.6 | 10.3 | 7.8 |

| Conization/CIN3+ | 4.8 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 4.7 | 3.3 |

Out of 4479 HPV‐positive women, 2060 were recommended first‐line cell‐sample follow‐up, and 1921 (=93%) underwent this procedure, Figure 1. The remaining 2419 test‐positive women were recommended CBC, and 2071 (=86%) underwent this procedure, while 256 (=11%) women had instead cell‐sample follow‐up. Taken together, 5% of the HPV‐positive women had no follow‐up (139 + 92 = 231) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Flow‐diagram for outcome in eligible participants of cervical screening of elderly women in Denmark in 2017. CBC, colposcopy, biopsy and cervical sampling; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; FU, follow‐up; HPV, human papillomavirus; Recom, recommended.

In follow‐up, 2888 of the 4479 screen‐positive women had a histology performed, equivalent to 64%. There were 1237 of the 4479 screen‐positive women who had a conization, equivalent to 28%. During follow‐up, 579 CIN2+ cases were diagnosed in cone specimens or biopsies; 209 CIN2 (including unclassifiable CIN); 314 CIN3, and 56 cancer cases. Five CIN2+ (95% CI: 5–6) cases were detected per 1000 women screened; 129 per 1000 HPV‐positive women; 200 per 1000 women with a histology; and 468 per 1000 women with conization, Table 2. Three CIN3+ (95% CI: 3–4) cases were detected per 1000 women screened; 83 per 1000 HPV‐positive women; 128 per 1000 women with a histology; and 299 per 1000 women with conization. The CIN2+ detection rate per 1000 HPV‐positive women was higher in the Capital Region than in the Central Region; 159 vs. 99, p < 0.0001, relative risk (RR) = 1.60 (1.29–1.99), a surprising finding as the HPV16/18 detection rate was lower in the Capital Region, but the follow‐up strategy was more radical. The CIN2+ detection rate per 1000 women with conization was considerably lower in Region North than in the Central Region; 277 vs 609, p < 0.0001, RR = 0.46 (0.36–0.58) reflecting that conization was in Region North often used as first‐line follow‐up of a positive HPV‐test. In the Capital Region, conization was also in some instances used as first‐line follow‐up, and there the CIN2+ detection rate per 1000 women with conization was also below that in the Central Region; 408 vs 609, p < 0.0001, RR = 0.67 (0.57–0.79).

For Denmark in total, the number needed to screen for detection of one CIN2+ case was 188. This number was somewhat lower in Region North and the Capital Region, 173 and 154, respectively, where the follow‐up regimes were more radical. On the national basis, five women had histology for each detected CIN2+ case, and 2.1 women underwent conization. The numbers of conizations per detected CIN2+ case were highest in Region North and the Capital Region, 3.6 and 2.4, respectively, and lowest in the Central Region and Region South, 1.6 and 1.5, respectively. The treatment threshold was CIN2+, but for completeness also number needed to screen for detection of one CIN3+ case is reported; for Denmark in total, it was 293.

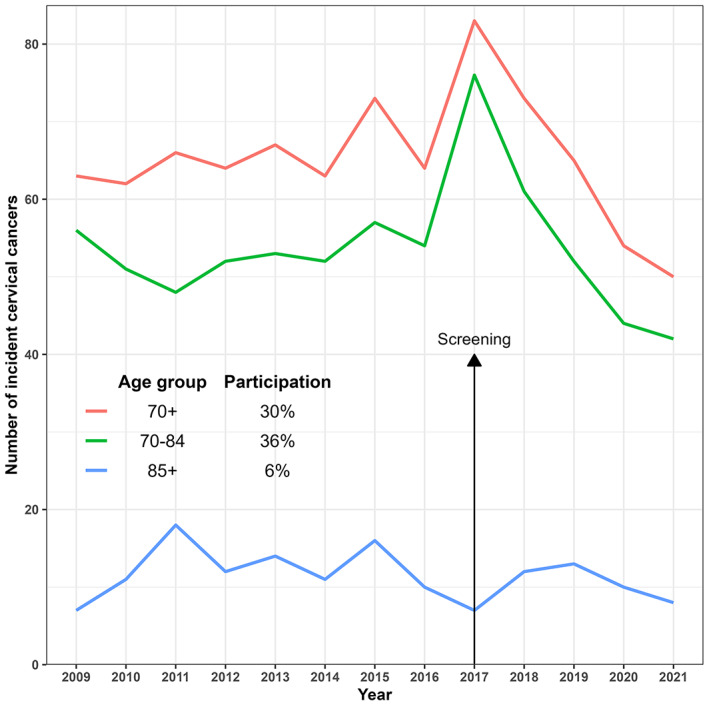

During the years 2009–2016, the annual number of incident cervical cancer cases for women aged 70+ in Denmark fluctuated around 64 (Figure 3 and Table S1). However, in 2017 the number reached 83, whereafter it decreased to 54 in 2020 and remained stable at this level in 2021 with 50 new cases.

FIGURE 3.

Incident cases of cervical cancer in women aged 70+ in Denmark by year 2009–2021.

4. DISCUSSION

To reduce cervical cancer incidence in old age, a one‐time, primary HPV‐screening was offered to women aged 70+ in Denmark. Women with detected CIN2+ were treated. One‐third of the targeted women accepted screening. In total, 41 per 1000 screened women had a positive HPV‐test; 27 had a histology sample taken; 11 underwent conization; and five out of 1000 screened women had CIN2+ detected. Close to 200 women needed to be screened for detection of one CIN2+ case, and close to 300 women for detection of one CIN3+ case. Screening outcome reflected regional differences in follow‐up strategy. Radicality in follow‐up was decisive for both benefit of screening in terms CIN2+ detection rate and for harm in terms of proportion of women undergoing conization. Although the purpose of screening is to detect precancerous lesions, our study demonstrated that also asymptomatic invasive cancers were detected at this prevalence screen.

The strength of this study was use of high‐quality data from the national Pathology Data Bank ensuring complete registration of all HPV, cytological and histological diagnoses following the positive HPV‐test. We did not correct for deaths and emigrations during the last two years of follow‐up, which means that we slightly underestimated completeness of follow‐up when we used number of screened women as denominator. Our regional data were not age‐adjusted, as the regions in this age‐range have similar age distributions. 9 We did not have data on individual cervical screening history, which could have been valuable as about half of cervical cancers are diagnosed in women with no or insufficient screening history. 10 It would have been valuable to follow all HPV‐positive women through the diagnostic process from HPV, to cytology, to histology outcome. Unfortunately, this was not possible. The regions had different follow‐up recommendations, and the practice in real life did not always follow the recommendations. Therefore, we were not able in a reliable way to illustrate the full flow across the diagnostic spectrum. Given the very wide stage‐dependent range in survival of cervical cancer patients, 11 it would have been valuable to have stage data for the cancers. Unfortunately, we did not have access to these data.

In 139 countries with documented official recommendations on cervical screening, only 14 countries reported end of screening at age 70 or older. 12 One of these countries is Australia, where all women aged 25–74 have been offered primary HPV‐screening since 2017. 13 During the period December 2017–December 2019, 88 889 women aged 70–74; and 6194 women aged 75+ were screened, of whom 4.3% (95% CI: 4.2–4.4) and 5.4% (95% CI: 4.9–6.0), respectively, were HPV‐positive. Our data are well in agreement with this finding, as 4.3% of the Danish women aged 69–73 were HPV‐positive, and 4.1% of women aged 74–78. 4 Only 87 CIN2+ cases were detected in Australian women aged 70+, giving a CIN2+ detection rate of 0.09% (95% CI: 0.07–0.11), compared with 0.5% (95% CI: 0.5–0.6) in Denmark. In interpretation of the difference, it should be considered that in the Australian data 16% of cell‐samples from women aged 70+ were non‐screening samples and excluded from the analysis; while in Denmark only 3.1% of samples were non‐screening samples and excluded from the analysis.

To our knowledge, data have not been published from other programs offering screening to women aged 70 and above. In a small study in Sweden from September 2013–June 2015, 1051 women aged 60–89 and attending an outpatient gynecology clinic had an HPV‐test. 14 Among these women 4.1% (95% CI: 3.0–5.5) were HPV‐positive, and 0.4% (95% CI: 0.1–1.0) had CIN2. These results are well in agreement with the Danish data.

Although covering slightly younger women aged 65–69, we used data from the Norwegian randomized implementation of primary HPV‐screening for comparison. 15 In the HPV‐arm 4.3% (95% CI: 3.9–4.8) of women aged 65–69 were referred for colposcopy. In the Danish data 2.7% (95% CI: 2.6–2.8) of women had CBC, but 4.0% (95% CI: 3.9–4.2) were recommended CBC. In Norway, 0.5% (95% CI: 0.4–0.7) had CIN2+ detected like in Denmark. In Norway, samples from non‐invited women with abnormal cytology, histology or HPV‐test during the two years before the screening date were excluded from the analysis. Numbers are not given, but this exclusion criterium is similar to the one used in Denmark.

There are differences between the Australian, Norwegian and Danish programs in eligibility criteria and in follow‐up strategies for elderly women. The screening outcomes were nevertheless fairly consistent with 4.3% HPV‐positive women at age 70–74 in Australia and Denmark, and with a 0.5% CIN2+ detection rate in Norway and Denmark.

In Denmark, the Parliament decided that the one‐time offer of cervical screening to elderly women should have no upper age limit. So, it caused some uproar from gynecologists when it became clear that about 1000 women aged 100 years or older would be invited for cervical screening. 16 The gynecologists argued that it can be very difficult to take a sample of representative cells from the cervix uteri in elderly women, 17 and it was debated whether 100‐year‐old women would want an operation for a lesion that might have killed them in 10–20 years' time. 18 The discussion turned out to be theoretical. Out of 25 906 invited women aged 89+ years, 495 were screened, and only 25 of these women were HPV‐positive. 4

In the Capital Region, all HPV‐positive women were referred directly to CBC, and it was clear that a higher proportion of screened women here had histology, 3.5%, than for instance the 2.1% of women in the in the Central Region. However, in the weighting of pros and cons for direct referral to CBC, it should be taken into account that referral to cell‐sample follow‐up will require the women to attend more gynecological examinations. Clinical considerations arose concerning the follow‐up and diagnostic assessment of elderly, HPV‐positive women, as they were not covered by pre‐existing guidelines. This led the Danish Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology in 2019 to develop a new national guideline on investigation, treatment, and follow‐up of abnormal screening results in women aged 60 years and above. 19 The recommended strategy was similar with the one used in Region South.

The argument in Denmark for a one‐time screening of elderly women was that older generations of women had not been adequately screened while they were younger. 2 In England, the fact that elderly women had been screened with cytology, which is less sensitive than HPV‐testing, has been an additional argument for a “catch‐up” HPV‐test of elderly women. 20 Arguments for a higher upper age‐limit are that HPV‐infection and/or cervical lesions detected at this late point in life may not have progressed to cervical cancer in the women's remaining lifetime. Among women aged 30–49 years, the duration from abnormal cytology to cervical cancer was estimated to be on average 15 years, 21 but it may be shorter in elderly women with impaired immune system, 1 and the upper age limit was chosen when life expectancy was lower than today. 22

The variation in screening outcome across Danish counties demonstrated impact of follow‐up strategy. The benefit in terms of number of CIN2+ detection rates per number of screened women was highest in regions with the most radical strategy, but so was harm in terms of number of women undergoing conization per detected CIN2+ case. The critical issue here is use of conization as first‐line follow‐up. This procedure is recommended when the transformation zone is not visible and/or sufficient sampling not possible. 19 , 23 , 24 A Danish study recruited 102 women aged 45+ and referred for CBC to have conization at the same time. CIN2+ was detected in biopsies from 15 women and in cones from 33 women, p < 0.01, thus a higher detection rate with conization but also considerable overtreatment because two third of the women undergoing conization had <CIN2. 25 Conization may have side effects as bleeding, infection, and as a rare event perforation to the bladder or rectum. Cervical stenosis occurs in 1%–7% of women undergoing conization with an increases risk for women >46 years. 23 , 24 Stenosis is an unwanted side‐effect as it may delay diagnosis of endometrial cancer due to lack of postmenopausal bleeding. In a qualitative Danish study, HPV‐positive elderly women were willing to risk overtreatment to shorten follow‐up time and limit number of visits. 26 A follow‐up for possible side‐effects in the cohort of 1237 women who underwent conization would be a valuable evaluation of the balance between benefit and harm of conization of elderly women.

The effect of cervical screening of elderly women on cervical cancer incidence depends on the women's willingness to participate. In Australia, 30% of women aged 70–74 were hysterectomized, and 35% of remaining eligible women had a screening sample registered. 13 In Denmark, 15% of women aged 70+ were hysterectomized, and 30% of eligible women were screened; 44% in the age group 69–73 years. 4 Coverage is thus still a challenge when it comes to impact of screening on the national cancer rates. Within the routine screening program, self‐sampling has proved to increase coverage in under‐screened women. 27 , 28 , 29 It remains to be seen if this would be the case also for elderly women.

In the years before the screening of elderly women in Denmark, annually 64 women aged 70+ years were diagnosed with cervical cancer. In the screening, nine times as many women were diagnosed with CIN2+, and 19 times as many women underwent conization. It is therefore reasonable to expect that the one‐time screening will lower cervical cancer incidence in elderly women. However, the screening resulted also in a prevalence peak of cervical cancers, and it will take some years before the full effect of the screening on cervical cancer incidence of elderly women can be evaluated. Elderly women and health care authorities will then have a clearer picture of benefit and harm. It was nevertheless promising that the number of cervical cancer cases had decreased to 54 in 2020 and remained at the same low level in 2021.

5. CONCLUSION

In 2017, Danish women aged 70+ received a one‐time invitation for primary HPV‐screening. The background was a relatively high incidence of cervical cancer in women above screening age. In total, 4.1% of screened women were HPV‐positive. Based on HPV‐type and cytology triage, about half of the women were recommended cell‐sample follow‐up, and the other half referral for CBC. In total, five per 1000 screened women had CIN2+ diagnosed, and three per 1000 CIN3+. Among the HPV‐positive women 28% had a conisation performed, but less than half of these women had a diagnosis of CIN2+. The screening resulted in a prevalence peak in incident cervical cancers, and it will therefore take some years before the cancer preventive effect of the screening can be evaluated.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MS and EL conceptualized and designed the study. PVH undertook the statistical analysis. MS and EL drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors commented on the table layout and manuscript, and all others accepted the final version for submission.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was financially supported by the Danish Cancer Society (R247‐A14608).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

BA reports non‐financial support from Roche and Axlab outside the submitted work. RS is a consultant for Merck. EL reports non‐financial support from Roche outside the submitted work. The remaining authors report no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Danish Health Data Authority for providing updated cervical cancer incidence data.

Skorstengaard M, Viborg PH, Telén Andersen AB, et al. A cervical screening initiative for elderly women in Denmark. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2023;102:791‐800. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14574

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Access to data from this study can be obtained from the Danish Clinical Registries (RKKP) following the Danish data protection legislation. https://www.rkkp.dk/siteassets/forskning/kontakt‐til‐patienten‐til‐forskningsformal/retningslinjer_forskning_version6_3.pdf

REFERENCES

- 1. Gravitt PE. The known unknowns of HPV natural history. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4593‐4599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lynge E, Lönnberg S, Törnberg S. Cervical cancer incidence in elderly women‐biology or screening history? Eur J Cancer. 2017;74:82‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Danish Cancer Register . [Incident cancer cases]. Accessed June 12, 2020. https://www.esundhed.dk/Registre/Cancerregisteret/Nye‐kraefttilfaelde. [In Danish].

- 4. Andersen B, Christensen BS, Christensen J, et al. HPV‐prevalence in elderly women in Denmark. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154:118‐123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. St‐Martin G, Viborg PH, Andersen ABT, et al. Histological outcomes in HPV‐screened elderly women in Denmark. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0246902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Danish Quality Database for Cervical Cancer Screening . [Results of the one‐time screening: Cervical screening in Danish women born before 1948 – 1st Report.] 2019. [In Danish].

- 7. Danish Quality Database for Cervical Cancer Screening . [Results of the one‐time screening: Cervical screening in Danish women born before 1948 – 2nd Report.] 2019. [In Danish].

- 8. Danish Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology . [Diagnosis, treatment and control of cervical dysplasia, 2012;1–30]. [In Danish].

- 9. Statistics Denmark . Accessed January 4, 2022. https://www.dst.dk/da/Statistik/emner/borgere/befolkning/befolkningstal

- 10. Dugué PA, Lynge E, Rebolj M. Mortality of non‐participants in cervical screening: register‐based cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:2674‐2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. [Danish gynecological cancer database] [In Danish] . Accessed January 16, 2023. https://www.sundhed.dk/content/cms/80/4680_dgcd‐aarsrapport‐2021‐2022‐offentliggjort‐version‐20221220.pdf

- 12. Bruni L, Serrano B, Roura E, et al. Cervical cancer screening programmes and age‐specific coverage estimates for 202 countries and territories worldwide: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10:e1115‐e1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smith MA, Sherrah M, Sultana F, et al. National experience in the first two years of primary human papillomavirus (HPV) cervical screening in an HPV vaccinated population in Australia: observational study. BMJ. 2022;376:e068582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hermansson RS, Olovsson M, Hoxell E, Lindström AK. HPV prevalence and HPV‐related dysplasia in elderly women. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0189300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nygård M, Engesæter B, Castle PE, et al. Randomized implementation of a primary human papillomavirus testing‐based cervical cancer screening protocol for women 34 to 69 years in Norway. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2022;31:1812‐1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Albinus N‐B. [Women aged 100 years invited for cervical screening]. Dagens Medicin 17 August 2017 [in Danish]. Accessed March 8, 2021. https://dagensmedicin.dk/100‐aarige‐indkaldes‐screening‐livmoderhalskraeft/

- 17. Klarskov N, Lose G. [Absurd screening offer to elderly women]. Dagens Medicin 24 August 2017 [in Danish]. Accessed March 8, 2021. https://dagensmedicin.dk/absurd‐screeningstilbud‐aeldre‐kvinder/

- 18. Rasmussen EA. [response]. https://dagensmedicin.dk/100‐aarige‐indkaldes‐screening‐livmoderhalskraeft/. Dagens Medicin 25 August 2017 [in Danish].

- 19. Danish Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology . [National guidelines for cervical cellular abnormalities. Women aged 60 and above]. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5467abcce4b056d72594db79/t/5f46241876e6b518465d3fe6/1598432295092/guideline_3844‐1_1‐202008260659.pdf [In Danish].

- 20. Gilham C, Crosbie EJ, Peto J. Cervical cancer screening in older women. BMJ. 2021;372:n280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bos AB, van Ballegooijen M, van Oortmarssen GJ, van Marle ME, Habbema JD, Lynge E. Non‐progression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia estimated from population‐screening data. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:124‐130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sherman SM, Castanon A, Moss E, Redman CW. Cervical cancer is not just a young woman's disease. BMJ. 2015;350:h2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Accessed February 2, 2023. https://www.cancer.org.au/clinical‐guidelines/cervical‐cancer‐screening/colposcopy/treatment

- 24. Regionala Cancercentrum . [Prevention of cervical cancer]. Nationellt vårdprogram 2015. [In Swedish].

- 25. Gustafson LW, Hammer A, Bennetsen MH, et al. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in women with transformation zone type 3: cervical biopsy versus large loop excision. BJOG. 2022;129:2132‐2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kirkegaard P, Gustafson LW, Petersen LK, Andersen B. ‘I want the whole package’. Elderly patients' preferences for follow‐up after abnormal cervical test results: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:1185‐1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lam JU, Rebolj M, Møller Ejegod D, et al. Human papillomavirus self‐sampling for screening nonattenders: opt‐in pilot implementation with electronic communication platforms. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:2212‐2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tranberg M, Bech BH, Blaakær J, Jensen JS, Svanholm H, Andersen B. Preventing cervical cancer using HPV self‐sampling: direct mailing of test‐kits increases screening participation more than timely opt‐in procedures—a randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ejegod DM, Pedersen H, Pedersen BT, Serizawa R, Bonde J. Operational experiences from the general implementation of HPV self‐sampling to Danish screening non‐attenders. Prev Med. 2022;160:107096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Data Availability Statement

Access to data from this study can be obtained from the Danish Clinical Registries (RKKP) following the Danish data protection legislation. https://www.rkkp.dk/siteassets/forskning/kontakt‐til‐patienten‐til‐forskningsformal/retningslinjer_forskning_version6_3.pdf