Abstract

Early embryogenesis requires the establishment of fields of progenitor cells with distinct molecular signatures. A balance of intrinsic and extrinsic cues determines the boundaries of embryonic territories and pushes progenitor cells towards different fates. This process involves multiple layers of regulation, including signaling systems, transcriptional networks, and post-transcriptional control. In recent years, microRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as undisputed regulators of developmental processes. Here, we discuss how miRNAs regulate pattern formation during vertebrate embryogenesis. We survey how miRNAs modulate the activity of signaling pathways to optimize transcriptional responses in embryonic cells. We also examine how localized RNA interference can generate spatial complexity during early development. Unraveling the complex crosstalk between miRNAs, signaling systems and cell fate decisions will be crucial for our understanding of developmental outcomes and disease.

Keywords: miRNAs, signaling systems, pattern formation, embryogenesis

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

During embryonic development, complex genetic programs orchestrate the arrangement of distinct cell types into tissues and organs. Morphogenesis begins with the establishment of fields of progenitor cells that share similar regulatory features. This process of pattern formation relies on the ability of cells to send and receive signals from their neighbors (Li and Elowitz, 2019; Perrimon et al., 2012). Cells and tissues must actively respond and convert extracellular signal concentrations into control of target gene expression, and misregulation of these processes can lead to developmental malformations and adult disease (Hagen and Lai, 2008; Li and Elowitz, 2019). This raises the question of how cells optimize the precise combinations and levels of signaling systems required for appropriate transcriptional outputs and subsequent cell-fate decisions.

Although transcriptional regulators act to balance signaling system activity during development (Alberti and Cochella, 2017; Groves and LaBonne, 2014; Perrimon et al., 2012), recent evidence suggests that post-transcriptional regulation via microRNA (miRNA)-mediated gene silencing also plays an important role in this process. miRNAs represent a diverse class of small (~22nt) single-stranded non-coding RNA molecules that have the ability to suppress gene expression via target mRNA degradation or translational repression (Bartel, 2018; Iwakawa and Tomari, 2015). miRNAs were first observed and characterized in the invertebrate model C. elegans when lin-4 and let-7 were shown to regulate developmental timing (Lee et al., 1993; Reinhart et al., 2000). These small RNAs were later shown to be conserved in humans and other animals and play important roles in regulating developmental transitions (Lagos-Quintana et al., 2001; Lau et al., 2001; Lee and Ambros, 2001; Pasquinelli et al., 2000). Individual miRNAs can participate in hundreds of molecular interactions, and recent studies suggest that approximately two-thirds of the transcriptome is regulated by miRNA-mediated repression (Bartel, 2018; Friedman et al., 2009; Hafner et al., 2010). Despite the modest effect miRNAs may have on target gene expression (<2-fold repression) (Baek et al., 2008; Selbach et al., 2008), their combined effects can have a substantial impact on developmental processes. Indeed, several studies have demonstrated that loss of miRNA biogenesis components, including Drosha, Dicer, and Ago, leads to early embryonic lethality, underscoring the importance of this pathway in cell state transitions (Alisch et al., 2007; Bernstein et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2007). Accordingly, there may be a variety of mechanisms by which miRNAs influence signaling systems during embryogenesis.

Over the past decade, numerous miRNAs have been shown to regulate signaling system activity during early development. Given the complex nature of signaling systems, miRNAs can elicit changes in signaling activity on multiple levels, including targeting of transducers, activators, and repressors (Li and Elowitz, 2019; Perrimon et al., 2012). Recent work also suggests that miRNAs are expressed in a tissue-specific manner via activation of primary-miRNA transcription by signaling systems (Rago et al., 2019; Redshaw et al., 2013). Thus, miRNAs may provide robustness to developmental mechanisms and also act as a buffering system to optimize signal transduction during pattern formation. Here, we examine existing evidence for crosstalk between miRNAs and developmental signaling pathways and the consequences of this regulation on vertebrate embryonic patterning.

Regulation of patterning signals by miRNAs

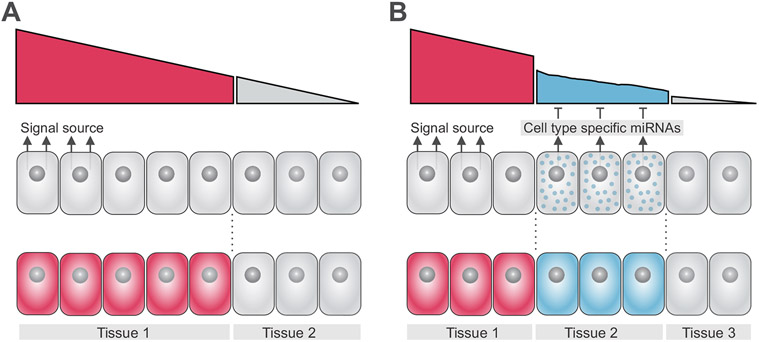

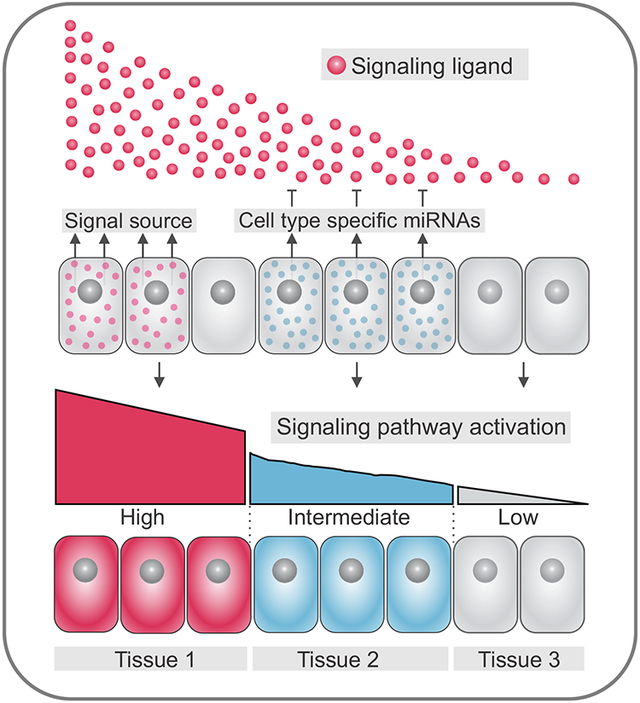

The spatial patterning of vertebrate embryos relies on the activation of signal transduction pathways, such as Wingless (Wnt), Transforming Growth Factor beta (TGF-β), and Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF). During early development, these signaling systems form gradients of activity that imbue progenitors with positional information (Gurdon et al., 1998; Wolpert, 1969; Zecca et al., 1996). Signaling gradients are set up via the localized production of secreted ligands by cells that act as the signal source (Fig. 1A). Ligands will diffuse through territories within the embryo and interact with receptors in target cells, triggering intracellular responses and activation of downstream genes (Kerszberg and Wolpert, 2007; Zhu and Scott, 2004). Varying levels in the activation of signaling transduction pathways may yield distinct transcriptional outputs and influence cell fate decisions. As a result, cells closer to the signal source may be specified as a particular tissue (Fig 1A), whereas cells that are further away may adopt an alternate fate.

Figure 1. miRNAs modulate signaling system levels in the early embryo.

(A) Varying levels of activation of signal transduction pathways yield distinct transcriptional outputs, delineating cell fate decisions. Cells receiving high levels of a particular signal near the source will become part of tissue 1, whereas cells farther away from the signal source which receive lower, if any, activation of the pathway will become part of tissue 2. (B) Tissue-specific expression of miRNAs (in tissue 2) results in dampened signaling system activity in intermediate cells (blue), resulting in formation of three distinct progenitor domains as compared to Fig. 1A.

Since spatial regulation of gene expression is crucial to early development, additional mechanisms act in conjunction with signaling gradients to ensure proper patterning. These include the localized expression of inhibitory molecules (Lander, 2007; Yamamoto et al., 2004), cellular features that control the dispersion of ligands (Zhu and Scott, 2004), and processes involved in post-transcriptional regulation. In particular, miRNAs have emerged as essential regulators of signaling pathway activity during pattern formation (Copeland and Simoes-Costa, 2020; Rago et al., 2019; Rosa et al., 2009; Silver et al., 2007). miRNAs are expressed throughout many stages of development in both invertebrates and vertebrates and disruptions in the temporal regulation of miRNAs can result in subtle or severe developmental defects (Harfe, 2005; Rosa and Brivanlou, 2009; Watanabe et al., 2005). Furthermore, miRNAs can modulate the cellular response to environmental signals by targeting components of transduction pathways. This level of regulation has been shown to confer additional robustness to developmental patterning (Choi et al., 2007; Copeland and Simoes-Costa, 2020; Kim et al., 2011; Leucht et al., 2008). Furthermore, by altering the sensitivity of embryonic progenitors to different levels of ligands, miRNAs can generate additional spatial complexity in the early embryo.

This concept is illustrated in Figure 1B, which shows how the localized expression of miRNAs can support the specification of a new regulatory domain within a field of progenitor cells. In this example, the activity of the morphogen is dampened by a set of miRNAs, resulting in lower pathway activation in intermediate cells (“tissue 2” progenitors). Since miRNAs can target multiple components of the same pathway (see below), progenitors of tissues 1 and 2 may display drastically different responses to similar concentrations of a ligand (Fig. 1B). We propose that RNA interference can thus prime progenitors to interpret extracellular cues in unique ways, either heightening or lowering the sensitivity of cells to a given signal. This may be crucial for the generation of cellular and spatial heterogeneity in early embryogenesis. Furthermore, cell fate commitment often requires precise combinations of extracellular signals. In these instances, a cell’s collection of microRNAs may modulate signal transduction to ensure the proper integration of spatial inputs during specification.

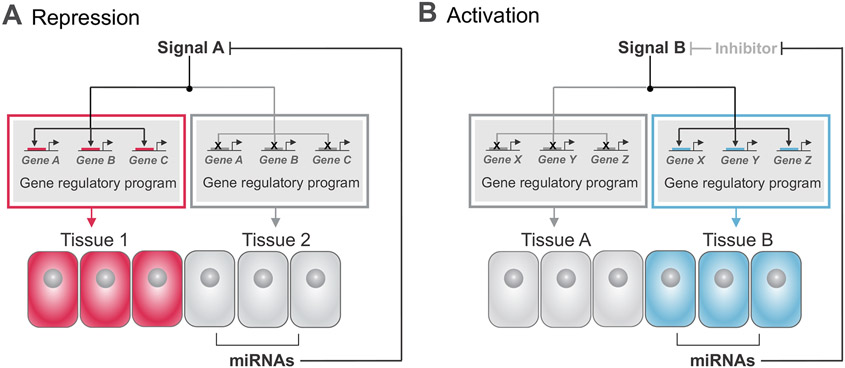

miRNAs can promote or repress signaling pathways

Although several studies have reported that deletion of individual miRNAs results in modest phenotypic effects (Chen et al., 2014; Giraldez et al., 2005; Miska et al., 2007; Park et al., 2012), the combinatorial activity of miRNAs can lead to a range of developmental outcomes. This is partly because signal transduction mobilizes complex biochemical pathways composed of multiple components, which might be activating or inhibitory. Combinations of miRNAs expressed in progenitor cells can act in concert to target different components within an individual pathway. Accordingly, miRNA regulation can either enhance or dampen the intracellular response to a particular signal (Inui et al., 2010). Generally, miRNAs can target activating or repressing components of signaling pathways to inhibit or promote their activity, respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. miRNAs can promote or repress signaling pathways.

(A) With repression, miRNAs targeting activators of Signal A ensures that Signal A is repressed, thus suppressing the gene regulatory program in red from being active in specified tissue 2 (cells in gray). (B) With activation, miRNAs targeting inhibitors of Signal B allow the activation of Signal B. Activation of Signal B specifies the gene regulatory program in blue to be activated in tissue B (cells in blue). Each example represents individual circumstances in which repression or activation of a signaling pathway can result in differentiation of specific tissues.

Inhibition of a signaling pathway occurs through the action of miRNAs that target its activating components (Fig. 2A). For example, the highly conserved Drosophila miRNA miR-8 negatively regulates the Wnt/Wingless (Wg) pathway. Identified in a genetic screen for regulators of Wg signaling, miR-8 inhibits two positive regulators of Wg, wntless (wls) and a gene referred to as CG32767. Additionally, miR-8 directly targets the transcription factor TCF (T-cell factor) which binds to DNA and co-activates target gene transcription in the Wnt pathway (Kennell et al., 2008). In vertebrates, we observe a similar mechanism via miR200a, the human and mouse homologs of miR-8, which regulates Wnt signaling by directly targeting the nuclear effector β-catenin (Kennell et al., 2008; Su et al., 2012). This represents an example where a highly abundant miRNA alone mediates significant changes in signaling outputs by targeting multiple activating components of a pathway. However, in most cases, due to their modest effect on target gene expression, miRNAs work together to dampen the effects of a signaling pathway. For example, multiple miRNAs, including miR-125b, miR-326, and miR-324, all have been shown to target Hedgehog (Hh) signaling, which plays essential roles in development including controlling cerebellar granule cell progenitor development. miR-125b and miR-326 were shown to target Smoothened and miR-324-5p targets Gli1; both targets are activators of Hh signaling in human medulloblastoma cells (Ferretti et al., 2008).

Although miRNAs function to repress gene expression, this regulation can result in signaling pathway activation when miRNAs target key inhibitors of a signaling pathway (Fig. 2B). For example, the Hippo signaling pathway, which controls tissue growth throughout development, has been shown to be activated by miR-372 (miR-373 in mammals) and miR-278 in Drosophila. miR-372/373 target the large tumor suppressor (LATS) kinase, and miR-278 targets its upstream regulator Expanded. Repression of LATS and Expanded by their respective miRNAs results in activation of Yes-associated protein (YAP) and Taffazin (TAZ), the nuclear effectors of Hippo signaling, causing overall activation of the pathway (Nairz et al., 2006; Teleman et al., 2006; Voorhoeve et al., 2006).

The above examples of repression and activation of signaling pathways demonstrate how miRNAs are highly integrated into the control of developmental signaling systems. These modes of regulation explain how the same signal can have different effects based on the cell type-specific miRNAs that are expressed in that context. In this way, miRNAs can act to fine-tune the transcriptional output of signaling systems during embryonic development. In the remainder of this review, we will further explore this concept by discussing the role miRNAs play in regulating signaling systems to control cell fate decisions and pattern formation throughout vertebrate development.

Examples of regulation of signaling pathways by miRNAs

FGF signaling

Fibroblast growth factor signaling (FGF) plays an uncontested role in vertebrate embryogenesis (Dorey and Amaya, 2010). Briefly, FGF extracellular ligands bind to receptor tyrosine kinases resulting in receptor dimerization(Ray et al., 2020). This event can trigger the activation of several intracellular signal transduction pathways associated with cell differentiation and proliferation, including the RAS-MAPK and PI3K-AKT pathways (Dorey and Amaya, 2010; Schlessinger, 2000). FGF signaling drives key embryonic patterning events, including, but not limited to, the formation of the mesoderm and ectoderm (Bökel and Brand, 2013; Ciruna and Rossant, 2001; Fürthauer et al., 1997; Wells and Melton, 2000; Wilson et al., 2000). In such cases, secreted FGF ligands form a concentration gradient over a target tissue, leading to induction of various cell types based on the level of signaling system activity produced (Balasubramanian and Zhang, 2016). The spatiotemporal complexity of FGF signaling in the early embryo provides us with a useful system to examine how miRNA-mediated gene silencing can impact patterning events.

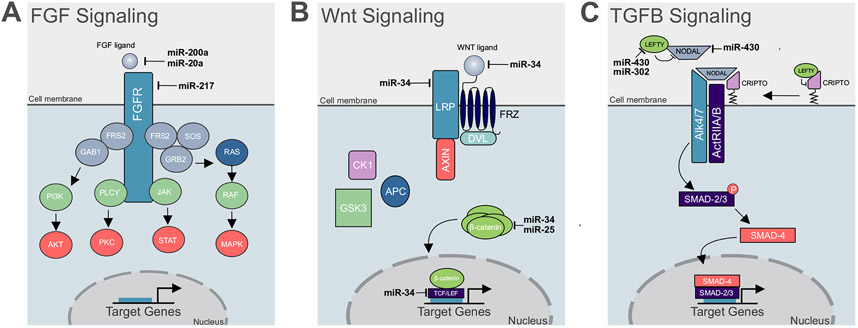

Consistent with this idea, we have recently demonstrated that post-transcriptional tuning of FGF signaling is critical for induction of chick neural crest cells (Fig. 3A) (Copeland and Simoes-Costa, 2020). A gradient of FGF and Wnt activity are critical for partitioning the ectoderm into the neural plate and neural crest (Groves and LaBonne, 2014). Our results demonstrated that a group of miRNAs, enriched in neural crest, work in a concerted fashion to post-transcriptionally attenuate FGF signaling and create conditions for proper cell specification of the neural crest lineage. Inhibition of these tissue specific miRNAs leads to the expansion of the neural plate at the expense of neural crest cells, underscoring their contribution to ensuring proper levels of FGF signaling during neural crest induction. A similar mechanism is observed in D. melanogaster, where mir-9 targets several components of the FGF signaling pathway to pattern the midbrain-hindbrain boundary (Leucht et al., 2008); highlighting the importance of post-transcriptional tuning of FGF signaling in developmental patterning events. These findings support the idea that miRNAs play an essential role in regulating gene expression levels by acting in a combinatorial fashion to target multiple components of a signaling pathway.

Figure 3. Examples of miRNA regulation of signaling systems during embryonic patterning events.

(A) In the early chick embryo, miRNAs 200a, 20a, and 217, work in a concerted effort to target the FGF ligand and receptor, leading to decrease pathway activation in neural crest cells, as compared to the neighboring cell population, the neural plate. (B) In Xenopus miR-34 targets multiple components of the Wnt Signaling pathway, including the Wnt ligand, LRP, and the nuclear effectors β-catenin, and LEF1. In zebrafish, the mammalian ortholog of miR-25 targets β-catenin. Attenuation of the Wnt signaling pathway by miR-34 and miR-25 is essential for normal anterior posterior patterning in the early embryo. (C) In Zebrafish, miR-430 targets both the Nodal ligand, and its antagonist, Lefty, to balance Nodal signaling activation, leading to proper delineation of the developing mesoderm and endoderm. In human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), miR-302 targets the antagonist Lefty, but not the Nodal ligand, highlighting species specific targeting events via miRNAs.

Wnt signaling

The Wingless (Wnt) signaling pathway is highly conserved, and it is known to control many cellular processes throughout development, including cell proliferation, cell polarity, cell fate, and body axis determination (Fossat et al., 2011; Yamaguchi, 2001). Wnt proteins are secreted glycoproteins that bind to the Frizzled (Fz) family of receptors. In the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, Wnt ligands bind Fz with the co-receptor low-density-lipoprotein-related protein5/6 (LRP5/6). The binding of Wnt ligands to this receptor complex leads to inhibition of β-catenin degradation, allowing β-catenin to be stabilized and thus translocate to the nucleus. Subsequently, β-catenin interacts with members of the T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) family of HMG-box containing transcription factors to directly bind to DNA and co-activate target gene expression (Cadigan and Waterman, 2012; Komiya and Habas, 2008).

Abnormal activation or inhibition of Wnt signaling leads to major developmental defects, especially during axis specification (Fossat et al., 2011; Yamaguchi, 2001). For example, in Xenopus, ectopic Wnt activation induces a secondary body axis (Du et al., 1995), underscoring the importance of mechanisms that ensure precise regulation of this signaling system. Accordingly, there are multiple reports of miRNA-mediated suppression of components of the Wnt pathway. The miR-34 family, under the control of p53, has been shown to be a potent suppressor of Wnt signaling that targets genes like β-catenin, Wnt1, Wnt3, LRP6, and LEF1 (Bommer et al., 2007; Chang et al., 2007; He et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2011; Yamakuchi et al., 2008). Mutations in the 3’UTR of β-catenin, which contains miR-34 binding sites, are sufficient to cause axis duplications in Xenopus embryos (Kim et al., 2011). This phenotype represents an example of tissue-specific function of miR-34, which is essential for attenuation of Wnt signaling in order to prevent embryonic axis duplication (Fig. 3B).

Similar modes of regulation occur in invertebrates like sea urchin. In Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, β-catenin is regulated by at least two miRNAs, one of which is the ortholog of miR-25. Mutations in the 3’ UTR of β-catenin, which contains multiple miRNA binding sites, resulted in endodermal and mesodermal defects. Furthermore, this manipulation resulted in an increase in transcript levels of endodermal regulator genes (Stepicheva et al., 2015). Thus, miRNA suppression of β-catenin is essential to limit the endoderm transcriptional program from being aberrantly activated (Fig. 3B). These studies identify tissue-specific miRNA suppression of Wnt signaling as an essential regulatory mechanism acting in cell fate specification. While Wnt levels in the early embryo are known to be controlled by a balance of pathway-specific antagonists, these studies show miRNAs are an integral part of the regulatory programs controlling pattern formation.

TGF-β signaling

Transforming growth factor TGF-β family signaling is yet another system that plays a crucial role in axis formation and patterning of multiple tissues in the early vertebrate embryo (Zinski et al., 2018). One such family member Nodal, is critical for establishing the mesoderm and endoderm during gastrulation (Shen, 2007). Key to the regulation of Nodal, is the downstream activation of extracellular inhibitors that can modulate the activity of Nodal ligands, including Lefty (Branford and Yost, 2002; Feldman et al., 2002). Interestingly, Lefty activity is essential for proper patterning, as loss of this antagonist leads to ectopic mesodermal induction (Agarwal et al., 2015; Branford and Yost, 2002; Feldman et al., 2002). Similar to other signaling systems discussed in this review, Nodal has been shown to act as a morphogen, eliciting changes in cell fate decisions based on fluctuations in concentration, particularly between the mesoderm and endoderm (Chen and Schier, 2001; Green and Smith, 1990). Given that a subtle balance of activity between agonists and antagonists of the TGF-β superfamily is required for proper embryogenesis, it is likely that post-transcriptional regulation via miRNAs modulates the activity of this signaling system.

Several lines of evidence support a role for post-transcriptional regulation of Nodal activity through the activation of the miR-430/427/302 family (Alberti and Cochella, 2017; Choi et al., 2007; Rosa et al., 2009). In Zebrafish, miR-430 balances Nodal signaling system activity by targeting both the agonist squint and the antagonist lefty during gastrulation, promoting proper delineation between mesoderm and endoderm (Choi et al., 2007). Similar targeting of Nodal agonists and antagonists is also observed in Xenopus and human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) (Fig.3C), highlighting the conservation of post-transcriptional tuning mechanisms across organisms (Rosa et al., 2009). Intriguingly, in hESCs, only Lefty antagonists, but not Nodal, are targets of miR-302. Loss of miR-302, and therefore an increase in Nodal pathway activity, inhibits mesodermal and endodermal fates and expands neuroectodermal derivatives(Rosa et al., 2009). These results demonstrate that although the miR-430/427/302 family is highly conserved, there exists species-specific targeting of the Nodal pathway, leading to various consequences on germ layer formation.

Spatial regulation of miRNAs

Signaling systems are main contributors to developmental gene regulatory networks (GRNs), serving as critical inputs for transcriptional activation of cell type specific factors (Sauka-Spengler and Bronner-Fraser, 2008; Simões-Costa and Bronner, 2015). Given that protein coding genes and miRNAs are transcriptionally controlled in a similar fashion, they are subject to the same modes of regulation (Bartel, 2018). Indeed, several lines of evidence from multiple species have demonstrated that nuclear effectors of signaling systems and tissue specific transcription factors, bind to the promoter regions of intergenic miRNAs, driving their tissue specific expression (Fu et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2014; Qian et al., 2011; Rago et al., 2019; Thompson and Cohen, 2006). These findings suggest an intriguing paradigm in which sets of miRNAs activated by an active signaling system in one tissue may inhibit response to opposing signals diffusing from other embryonic territories. In this scenario, miRNA-mediated repression would support the antagonistic interactions often observed between distinct signal transduction pathways. Such a mechanism would lend itself to proper partitioning of tissue boundaries during early patterning events.

Recent studies have demonstrated that several miRNAs are transcriptionally regulated by Smad proteins in the context of cancer and development. In mouse ES cells and early embryos, several miRNAs have been found to be directly regulated by pSmad2/3, the nuclear effectors of TGF-β signaling (Redshaw et al., 2013). Additionally, a study in Zebrafish has identified Nodal activation of miRNAs as an essential process in heart laterality development (Rago et al., 2019). This process requires the attenuation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) factors in the left lateral plate mesoderm by Nodal activated miRNAs, leading to proper left/right division of the lateral plate mesoderm required for heart morphogenesis (Rago et al., 2019). This study in particular highlights the complex nature of miRNA activation and target gene regulation present in different developing tissues.

Along with transcriptional signaling effectors activating tissue specificity of miRNAs, epigenetic mechanisms including DNA methylation and histone modifications have been found to effect miRNA expression in development and disease (Chuang and Jones, 2007; Liu et al., 2013; Sanchez-Vasquez et al., 2019; Weber et al., 2007). For example, in the early chick embryo, hypermethylation of the miR-203 promoter via DNMT3B results in accumulation of EMT factors PHF12 and SNAIL2, leading to delamination and migration of neural crest cells. The recruitment of DNMT3B to the miR-203 locus is directed by SNAIL2, forming a negative feedback loop that enables expression of miRNA target genes (Sanchez-Vasquez et al., 2019). Along with transcription factor directed DNA methylation, studies in cancer have demonstrated that signaling systems, including TGF-β, can direct methylation at the miR-200 loci, resulting in a corresponding decrease in its expression levels (Gregory et al., 2011). These results suggest that miRNAs may form feedback loops with transcriptional effectors to modulate signaling system levels in an epigenetic dependent manner, promoting cell state transitions.

Recently, super enhancer activity has also been linked to activation of highly active and highly abundant master miRNAs in a cell type specific fashion (Suzuki et al., 2017). Interestingly, association of miRNA loci with super enhancers increases recruitment of miRNA processing machinery, boosting miRNA production(Suzuki et al., 2017). Given the drastic changes in chromatin architecture present during early developmental processes, super enhancer activity at miRNA loci may facilitate rapid turnover of miRNAs required for patterning events in a plethora of tissues and cell types. Although recent studies and advancing techniques have revealed complex layers to the regulation of miRNA expression (Bartel, 2018; Rago et al., 2019; Sanchez-Vasquez et al., 2019; Suzuki et al., 2017), much work remains to be done to elucidate the interplay between these mechanisms and various developmental processes.

Discussion

Here, we examine how miRNAs regulate embryonic patterning by modulating signaling systems that are reiteratively used during development. We have discussed how experiments performed in the last decades have demonstrated that (i) miRNAs can act individually or in sets to modulate how progenitor cells respond to extracellular cues; (ii) regulation of signal transduction pathways is complex, cell-type specific, and can result in either their activation or repression and (iii) differential expression of miRNAs may increase spatial complexity and cellular diversity, and also confer robustness to developmental processes. These paradigms shed light on new mechanisms that are crucial for the integration of extrinsic and intrinsic cues required for cell fate commitment and underscore the importance of RNA interference in development and disease.

The multiple roles miRNAs have in the regulation of morphogenetic events raises the question as to whether their dysregulation contributes to congenital malformations. Although the loss of key miRNA biogenesis components leads to early embryonic lethality (Alberti and Cochella, 2017; Alisch et al., 2007; Bernstein et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2007), changes in miRNA sequence or gene target sites could lead to deleterious effects on gene expression resulting in embryonic dysmorphogenesis (Kloosterman and Plasterk, 2006). Accordingly, miRNAs may serve as useful biomarkers for early detection of embryonic malformations in pregnancy and could provide a platform for disease therapeutics (Li and Zhao, 2014). Furthermore, numerous studies that target individual miRNAs in model organisms show that these manipulations result in a range of developmental defects.

When considering the contribution that signaling system targeting miRNAs may have on developmental disease, two potential outcomes seem apparent. First, loss of a miRNA family that targets major and/or multiple components of a signaling system during early morphogenetic events (i.e, gastrulation) would most likely lead to embryonic lethality and therefore would not be present in the population. However, loss of a miRNA targeting one component of a signaling system may cause a subtle change in pathway activity. Although these effects may be modest, this could lead to slight alterations in cell fate or shifts in pattern formation, ultimately causing developmental malformations. These disease related phenotypes would most likely be more apparent in the population, as they may be less likely to cause embryonic lethality.

While, miRNAs play various roles in development, experimentally known associations between miRNAs and developmental disease remains lacking. In the coming years, more work will need to be done to understand miRNA-disease associations as related to development. Conversely, a plethora of information exists on the roles of miRNAs in cancer and adult onset diseases (Paul et al., 2018; Peng and Croce, 2016), including miRNAs which target signaling systems (Khan et al., 2019; Xia et al., 2012). As cancer is often considered a disease which aberrantly co-opts developmental programs, it will be interesting to determine if miRNAs expressed in a developmental context are re-activated in cancer, facilitating malignant transformation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Cornell CVG Scholars Award to J.C. and a Cornell Sloan Fellowship to K.W. We would like to thank the members of the Simoes-Costa Lab for critical reading of the manuscript and valuable suggestions.

Abbreviations:

- miRNA

microRNA

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor beta

- FGF

Fibroblast growth factor

- Wnt

Wingless

- hESCs

Human embryonic stem cells

- TCF/LEF

T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor

- Hh

Hedgehog signaling

- LATS kinase

large tumor suppressor kinase

- YAP

Yes-associated protein

- TAZ

Taffazin

- Fz

Frizzled receptor

- LRP5/6

low-density-lipoprotein-related protein5/6

- GRN

gene regulatory network

- EMT

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW, and Bartel DP (2015). Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberti C, and Cochella L (2017). A framework for understanding the roles of miRNAs in animal development. Development 144, 2548–2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alisch RS, Jin P, Epstein M, Caspary T, and Warren ST (2007). Argonaute2 is essential for mammalian gastrulation and proper mesoderm formation. PLoS Genet 3, e227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek D, Villén J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, and Bartel DP (2008). The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature 455, 64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian R, and Zhang X (2016). Mechanisms of FGF gradient formation during embryogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol 53, 94–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP (2018). Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell 173, 20–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Kim SY, Carmell MA, Murchison EP, Alcorn H, Li MZ, Mills AA, Elledge SJ, Anderson KV, and Hannon GJ (2003). Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat Genet 35, 215–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bökel C, and Brand M (2013). Generation and interpretation of FGF morphogen gradients in vertebrates. Curr Opin Genet Dev 23, 415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommer GT, Gerin I, Feng Y, Kaczorowski AJ, Kuick R, Love RE, Zhai Y, Giordano TJ, Qin ZS, Moore BB, et al. (2007). p53-mediated activation of miRNA34 candidate tumor-suppressor genes. Curr Biol 17, 1298–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branford WW, and Yost HJ (2002). Lefty-dependent inhibition of Nodal- and Wnt-responsive organizer gene expression is essential for normal gastrulation. Curr Biol 12, 2136–2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan KM, and Waterman ML (2012). TCF/LEFs and Wnt signaling in the nucleus. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TC, Wentzel EA, Kent OA, Ramachandran K, Mullendore M, Lee KH, Feldmann G, Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, Lowenstein CJ, et al. (2007). Transactivation of miR-34a by p53 broadly influences gene expression and promotes apoptosis. Mol Cell 26, 745–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, and Schier AF (2001). The zebrafish Nodal signal Squint functions as a morphogen. Nature 411, 607–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YW, Song S, Weng R, Verma P, Kugler JM, Buescher M, Rouam S, and Cohen SM (2014). Systematic study of Drosophila microRNA functions using a collection of targeted knockout mutations. Dev Cell 31, 784–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WY, Giraldez AJ, and Schier AF (2007). Target protectors reveal dampening and balancing of Nodal agonist and antagonist by miR-430. Science 318, 271–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang JC, and Jones PA (2007). Epigenetics and microRNAs. Pediatr Res 61, 24r–29r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciruna B, and Rossant J (2001). FGF signaling regulates mesoderm cell fate specification and morphogenetic movement at the primitive streak. Dev Cell 1, 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J, and Simoes-Costa M (2020). Post-transcriptional tuning of FGF signaling mediates neural crest induction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117, 33305–33316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorey K, and Amaya E (2010). FGF signalling: diverse roles during early vertebrate embryogenesis. Development 137, 3731–3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du SJ, Purcell SM, Christian JL, McGrew LL, and Moon RT (1995). Identification of distinct classes and functional domains of Wnts through expression of wild-type and chimeric proteins in Xenopus embryos. Mol Cell Biol 15, 2625–2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman B, Concha ML, Saúde L, Parsons MJ, Adams RJ, Wilson SW, and Stemple DL (2002). Lefty antagonism of Squint is essential for normal gastrulation. Curr Biol 12, 2129–2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti E, De Smaele E, Miele E, Laneve P, Po A, Pelloni M, Paganelli A, Di Marcotullio L, Caffarelli E, Screpanti I, et al. (2008). Concerted microRNA control of Hedgehog signalling in cerebellar neuronal progenitor and tumour cells. Embo J 27, 2616–2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossat N, Jones V, Khoo PL, Bogani D, Hardy A, Steiner K, Mukhopadhyay M, Westphal H, Nolan PM, Arkell R, et al. (2011). Stringent requirement of a proper level of canonical WNT signalling activity for head formation in mouse embryo. Development 138, 667–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, and Bartel DP (2009). Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res 19, 92–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu S, Nien CY, Liang HL, and Rushlow C (2014). Co-activation of microRNAs by Zelda is essential for early Drosophila development. Development 141, 2108–2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fürthauer M, Thisse C, and Thisse B (1997). A role for FGF-8 in the dorsoventral patterning of the zebrafish gastrula. Development 124, 4253–4264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldez AJ, Cinalli RM, Glasner ME, Enright AJ, Thomson JM, Baskerville S, Hammond SM, Bartel DP, and Schier AF (2005). MicroRNAs regulate brain morphogenesis in zebrafish. Science 308, 833–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JB, and Smith JC (1990). Graded changes in dose of a Xenopus activin A homologue elicit stepwise transitions in embryonic cell fate. Nature 347, 391–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory PA, Bracken CP, Smith E, Bert AG, Wright JA, Roslan S, Morris M, Wyatt L, Farshid G, Lim YY, et al. (2011). An autocrine TGF-beta/ZEB/miR-200 signaling network regulates establishment and maintenance of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Mol Biol Cell 22, 1686–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves AK, and LaBonne C (2014). Setting appropriate boundaries: fate, patterning and competence at the neural plate border. Dev Biol 389, 2–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Maki M, Ding R, Yang Y, Zhang B, and Xiong L (2014). Genome-wide survey of tissue-specific microRNA and transcription factor regulatory networks in 12 tissues. Sci Rep 4, 5150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurdon JB, Dyson S, and St Johnston D (1998). Cells' perception of position in a concentration gradient. Cell 95, 159–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, Khorshid M, Hausser J, Berninger P, Rothballer A, Ascano M Jr., Jungkamp AC, Munschauer M, et al. (2010). Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell 141, 129–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen JW, and Lai EC (2008). microRNA control of cell-cell signaling during development and disease. Cell Cycle 7, 2327–2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfe BD (2005). MicroRNAs in vertebrate development. Curr Opin Genet Dev 15, 410–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, He X, Lim LP, de Stanchina E, Xuan Z, Liang Y, Xue W, Zender L, Magnus J, Ridzon D, et al. (2007). A microRNA component of the p53 tumour suppressor network. Nature 447, 1130–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui M, Martello G, and Piccolo S (2010). MicroRNA control of signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11, 252–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakawa HO, and Tomari Y (2015). The Functions of MicroRNAs: mRNA Decay and Translational Repression. Trends Cell Biol 25, 651–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennell JA, Gerin I, MacDougald OA, and Cadigan KM (2008). The microRNA miR-8 is a conserved negative regulator of Wnt signaling. P Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 15417–15422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerszberg M, and Wolpert L (2007). Specifying positional information in the embryo: looking beyond morphogens. Cell 130, 205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AQ, Ahmed EI, Elareer NR, Junejo K, Steinhoff M, and Uddin S (2019). Role of miRNA-Regulated Cancer Stem Cells in the Pathogenesis of Human Malignancies. Cells 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim NH, Kim HS, Kim NG, Lee I, Choi HS, Li XY, Kang SE, Cha SY, Ryu JK, Na JM, et al. (2011). p53 and microRNA-34 are suppressors of canonical Wnt signaling. Sci Signal 4, ra71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloosterman WP, and Plasterk RH (2006). The diverse functions of microRNAs in animal development and disease. Dev Cell 11, 441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiya Y, and Habas R (2008). Wnt signal transduction pathways. Organogenesis 4, 68–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, and Tuschl T (2001). Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science 294, 853–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander AD (2007). Morpheus unbound: reimagining the morphogen gradient. Cell 128, 245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau NC, Lim LP, Weinstein EG, and Bartel DP (2001). An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 294, 858–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, and Ambros V (2001). An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 294, 862–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, and Ambros V (1993). The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75, 843–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht C, Stigloher C, Wizenmann A, Klafke R, Folchert A, and Bally-Cuif L (2008). MicroRNA-9 directs late organizer activity of the midbrain-hindbrain boundary. Nat Neurosci 11, 641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, and Elowitz MB (2019). Communication codes in developmental signaling pathways. Development 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, and Zhao Z (2014). MicroRNA biomarkers for early detection of embryonic malformations in pregnancy. J Biomol Res Ther 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Chen X, Yu X, Tao Y, Bode AM, Dong Z, and Cao Y (2013). Regulation of microRNAs by epigenetics and their interplay involved in cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 32, 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Abbott AL, Lau NC, Hellman AB, McGonagle SM, Bartel DP, Ambros VR, and Horvitz HR (2007). Most Caenorhabditis elegans microRNAs are individually not essential for development or viability. PLoS Genet 3, e215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairz K, Rottig C, Rintelen F, Zdobnov E, Moser M, and Hafen E (2006). Overgrowth caused by misexpression of a microRNA with dispensable wild-type function. Developmental Biology 291, 314–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CY, Jeker LT, Carver-Moore K, Oh A, Liu HJ, Cameron R, Richards H, Li Z, Adler D, Yoshinaga Y, et al. (2012). A resource for the conditional ablation of microRNAs in the mouse. Cell Rep 1, 385–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinelli AE, Reinhart BJ, Slack F, Martindale MQ, Kuroda MI, Maller B, Hayward DC, Ball EE, Degnan B, Muller P, et al. (2000). Conservation of the sequence and temporal expression of let-7 heterochronic regulatory RNA. Nature 408, 86–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul P, Chakraborty A, Sarkar D, Langthasa M, Rahman M, Bari M, Singha RS, Malakar AK, and Chakraborty S (2018). Interplay between miRNAs and human diseases. J Cell Physiol 233, 2007–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, and Croce CM (2016). The role of MicroRNAs in human cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther 1, 15004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrimon N, Pitsouli C, and Shilo BZ (2012). Signaling mechanisms controlling cell fate and embryonic patterning. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4, a005975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J, Zhang Z, Liang J, Ge Q, Duan X, Ma F, and Li F (2011). The full-length transcripts and promoter analysis of intergenic microRNAs in Drosophila melanogaster. Genomics 97, 294–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rago L, Castroviejo N, Fazilaty H, Garcia-Asencio F, Ocaña OH, Galcerán J, and Nieto MA (2019). MicroRNAs Establish the Right-Handed Dominance of the Heart Laterality Pathway in Vertebrates. Dev Cell 51, 446–459.e445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray AT, Mazot P, Brewer JR, Catela C, Dinsmore CJ, and Soriano P (2020). FGF signaling regulates development by processes beyond canonical pathways. Genes Dev 34, 1735–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redshaw N, Camps C, Sharma V, Motallebipour M, Guzman-Ayala M, Oikonomopoulos S, Thymiakou E, Ragoussis J, and Episkopou V (2013). TGF-β/Smad2/3 signaling directly regulates several miRNAs in mouse ES cells and early embryos. PLoS One 8, e55186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, Horvitz HR, and Ruvkun G (2000). The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 403, 901–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa A, and Brivanlou AH (2009). MicroRNAs in early vertebrate development. Cell Cycle 8, 3513–3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa A, Spagnoli FM, and Brivanlou AH (2009). The miR-430/427/302 family controls mesendodermal fate specification via species-specific target selection. Dev Cell 16, 517–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Vasquez E, Bronner ME, and Strobl-Mazzulla PH (2019). Epigenetic inactivation of miR-203 as a key step in neural crest epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Development 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauka-Spengler T, and Bronner-Fraser M (2008). A gene regulatory network orchestrates neural crest formation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9, 557–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlessinger J (2000). Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell 103, 211–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selbach M, Schwanhäusser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, and Rajewsky N (2008). Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature 455, 58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen MM (2007). Nodal signaling: developmental roles and regulation. Development 134, 1023–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver SJ, Hagen JW, Okamura K, Perrimon N, and Lai EC (2007). Functional screening identifies miR-315 as a potent activator of Wingless signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 18151–18156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simões-Costa M, and Bronner ME (2015). Establishing neural crest identity: a gene regulatory recipe. Development 142, 242–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepicheva N, Nigam PA, Siddam AD, Peng CF, and Song JL (2015). microRNAs regulate beta-catenin of the Wnt signaling pathway in early sea urchin development. Dev Biol 402, 127–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su J, Zhang A, Shi Z, Ma F, Pu P, Wang T, Zhang J, Kang C, and Zhang Q (2012). MicroRNA-200a suppresses the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway by interacting with beta-catenin. Int J Oncol 40, 1162–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki HI, Young RA, and Sharp PA (2017). Super-Enhancer-Mediated RNA Processing Revealed by Integrative MicroRNA Network Analysis. Cell 168, 1000–1014.e1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teleman AA, Maitra SN, and Cohen SM (2006). Drosophila lacking microRNA miR-278 are defective in energy homeostasis (vol 20, pg 417, 2006). Gene Dev 20, 913–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson BJ, and Cohen SM (2006). The Hippo pathway regulates the bantam microRNA to control cell proliferation and apoptosis in Drosophila. Cell 126, 767–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorhoeve PM, le Sage C, Schrier M, Gillis AJM, Stoop H, Nagel R, Liu YP, van Duijse J, Drost J, Griekspoor A, et al. (2006). A genetic screen implicates miRNA-372 and miRNA-373 as oncogenes in testicular germ cell tumors. Cell 124, 1169–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Medvid R, Melton C, Jaenisch R, and Blelloch R (2007). DGCR8 is essential for microRNA biogenesis and silencing of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nat Genet 39, 380–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Takeda A, Mise K, Okuno T, Suzuki T, Minami N, and Imai H (2005). Stage-specific expression of microRNAs during Xenopus development. FEBS Lett 579, 318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber B, Stresemann C, Brueckner B, and Lyko F (2007). Methylation of human microRNA genes in normal and neoplastic cells. Cell Cycle 6, 1001–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JM, and Melton DA (2000). Early mouse endoderm is patterned by soluble factors from adjacent germ layers. Development 127, 1563–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SI, Graziano E, Harland R, Jessell TM, and Edlund T (2000). An early requirement for FGF signalling in the acquisition of neural cell fate in the chick embryo. Curr Biol 10, 421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert L (1969). Positional information and the spatial pattern of cellular differentiation. J Theor Biol 25, 1–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H, Ooi LL, and Hui KM (2012). MiR-214 targets β-catenin pathway to suppress invasion, stem-like traits and recurrence of human hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One 7, e44206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi TP (2001). Heads or tails: Wnts and anterior-posterior patterning. Curr Biol 11, R713–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, and Lowenstein CJ (2008). miR-34a repression of SIRT1 regulates apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 13421–13426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Saijoh Y, Perea-Gomez A, Shawlot W, Behringer RR, Ang SL, Hamada H, and Meno C (2004). Nodal antagonists regulate formation of the anteroposterior axis of the mouse embryo. Nature 428, 387–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecca M, Basler K, and Struhl G (1996). Direct and long-range action of a wingless morphogen gradient. Cell 87, 833–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu AJ, and Scott MP (2004). Incredible journey: how do developmental signals travel through tissue? Genes Dev 18, 2985–2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinski J, Tajer B, and Mullins MC (2018). TGF-β Family Signaling in Early Vertebrate Development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]