Abstract

While wealth inequality is increasing worldwide, social interaction quality among communities is simultaneously decreasing. Although inequality is primarily correlated with the income gap, inequality is also significantly associated with the housing price gap, especially in South Korea. This study explores the correlation between housing price inequality and social interaction levels in Seoul. For this analysis, the housing price Gini coefficient was utilized through the housing transaction price, and social interaction was measured using the Korea Housing Survey. The results of this study indicate that the social interaction level was low in regions with large housing price inequality. Moreover, the social interaction level was low in regions where housing price inequality increased for 10 years. Furthermore, the negative correlation between housing price inequality and social interaction was significant only in the lower-asset class. The fact that inequality negatively influences social interactions only in the low-asset class is another aspect of inequality.

Keywords: Housing price inequality, Housing price gap, Social capital, Social interaction, Korea Housing Survey

Introduction

Wealth inequality is growing worldwide and causes various social issues. In most countries around the world, inequality has been steadily increasing over the past 30 years (Kawachi & Wamala, 2007), and the rate of increase is particularly threatening (Maclennan & Miao, 2017; Piketty, 2014). Wealth inequality is a social problem that many scholars are most concerned with, including Piketty (2014), Diamond (2019), Putnam (2016), and Sandel (2020). In addition, social issues and challenges related to socioeconomic inequality have received increasing attention in the social sciences field (Nijman & Wei, 2020). One social problem associated with wealth inequality is the retreat of social capital. Previous studies have empirically analyzed the hypothesis that social capital factors, such as community participation and trust, are low in regions with high income inequality (Eric, 2013; Kawachi et al., 1997; Putnam, 2000; Uslaner, 2003; Wilkinson, 2005). Thus, previous studies have illustrated that if a community economic gap grows, the social distance between neighboring residents increases and social interaction decreases.

Asset inequality has received as much attention as income inequality has in South Korea. In South Korea, negative perceptions are growing in public social opinion due to rising inequality, and economists and policymakers are concerned about political instability and economic growth hampering due to increased economic inequality (Yang & Greaney, 2017). Significantly, South Korea has a low redistribution rate even among OECD countries, and the gap between rich and poor is widening regarding income, real estate assets, and financial assets (Shin, 2020). In particular, asset inequality in South Korea is a feature of the widening gap owing to housing assets. Specifically, the difference in the wealth growth rate is increasing between homeowners and non-owners in South Korea. In addition, South Korea’s wealth inequality is characterized by a large difference in the asset growth rate depending on the level of current housing prices. According to a study by the Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements (2020), homeownership contributes significantly to enlarging the wealth gap. Moreover, South Korea Homeownership statistics (2020) state that the difference in wealth growth is huge between the bottom 10% and the top 10% of housing assets. In short, socioeconomic inequality in South Korea is characterized by a large asset gap based on housing ownership and prices.

Although many previous studies have explored low social capital because of income inequality, few have empirically examined the low social capital caused by asset inequality, such as housing prices. Previous literature in recent decades has analyzed the relationship between social capital and wealth inequality, mainly focusing on income inequality. However, because wealth inequality has a greater increase in the gap owing to housing asset value than income inequality in a nation such as South Korea, additional research is needed on the relationship between the housing asset value gap and social capital. Therefore, this study aims to explore the characteristics of social capital in an unequal environment by focusing on the housing price gap. We examine whether the social capital level is low in regions with large housing price gaps, like regions with large income gaps. Moreover, we analyzed the detailed characteristics according to the change rate of the housing price gap and household wealth levels. The first hypothesis is that the social capital level would be low in regions with high housing price inequality. The second hypothesis is that the social capital level would be lower in regions with increasing housing price inequality. Through the second hypothesis, we attempt to find the meaning of not only current inequality but also the situation in which inequality is increasing. Finally, the third hypothesis is that there is a difference in the association between housing price inequality and social capital depending on individual asset levels. Through the third hypothesis, we attempt to verify whether the low social capital according to the highly unequal environment is equal for everyone or different by economic level.

To achieve the aim of this study, we collected house prices and quantified the housing price inequality index for each of the 25 autonomous districts of Seoul. As a social capital variable, this study uses the response to the social interaction degree with neighbors through the Korea Housing Survey. Additionally, this study included other variables that had a causal relationship with social interaction as control variables in the analysis model. Finally, we analyze the relationship between the housing price gap and social interaction using an ordinal logistic regression method. This study explains the implications and discussion points based on the results of the analysis of the housing price gap and social interaction.

The results of this study would contribute to understanding the relationship between social capital and wealth inequality based on the housing prices gap. Regarding social capital, the first empirical analysis focuses on the current level of wealth inequality, and the second empirical analysis focuses on the increase in wealth inequality. These two empirical analyzes assist us in understanding the relationship between current levels and rising wealth inequality rates with social capital. Finally, the third empirical analysis explored the relationship between wealth inequality and social capital according to individual economic level. This empirical analysis would help understand how the association between wealth inequality and social capital changes according to the individual economic level. Such empirical analyzes are part of the gap in existing research and provide the necessary knowledge to understand the association between wealth inequality and social capital.

Literature Review

Wealthy Inequality in Urban Areas

Wealthy inequality has emerged as a social issue according to globalization,. Moreover, spatial segregation has intensified with the widening gap in income, race, and occupation (Chiu & Lui, 2004; Lemanski, 2007; Wessel, 2000). Global migration and developments in transportation have created disproportionate regional growth and geographical income inequality (Williams, 2009). The regional imbalance created by global migration has led to human capital and technology becoming concentrated in specific regions (Williams et al., 2004). Particularly, as transportation has become inexpensive, wealthy inequality has increased, as technical experts move to certain city hubs with airports (Williams, 2009; Williams & Baláž, 2009, 2003). In addition, the spread of automobiles has made it possible to separate poor urban areas from affluent suburban areas (Florida, 2017). Sassen (1991) has explained that the influx of immigrants from developing countries structurally leads to socioeconomic inequality in industrialized capitalist societies. Consequently, the wealth gap has increased, as human and material resources are concentrated in specific areas of the city, and the benefits of urban innovation and economic growth are concentrated in particular classes (Florida, 2017).

With the increasing wage gap, there has been an increase in regional separation concerning race, occupation, and income at a similar level. Castells (1989), a leading researcher of this phenomenon, found that as cities became globalized, they were divided into rich and poor regions. An imbalance in wealth distribution causes urban spatial imbalances (Castells & Mollenkopf, 1991). An increase in poor inhabitants in the downtown area and wealthy inhabitants outside the city leads to spatial imbalances in the area (Krumholz, 2013; Sassen, 1990, 1994). Global megacities are spatially segregated according to class and income (Scott et al., 2001). In this process, urban marginality is formed structurally, causing inequality within the region to be fixed (Sassen, 1998). As restaurants, high-end boutiques, and forms of entertainment that support the newly emerging elite emerge around high-income residents, they lead to geographical imbalances that create an uneven gap in urban services (Chiu & Lui, 2004). Such residential segregation, according to wealthy inequality, has a significant impact on local social networks, as information channels obtained from communities vary by income class (Florida, 2017). Namely, housing separated by income produces social segregation by schools, churches, and local communities, and social interactions between different income classes decrease (Sharkey, 2013).

Wealthy Inequality and the Quality of Social Interactions

Various studies have explored to verify the hypothesis that social capital decreases in high economic inequality regions. The concept of social capital means various resources that people can obtain through social interaction with neighbors and communities (Bourdieu, 1986). Social capital is formed as individuals interact with neighbors or participate in communities (Putnam, 2000) and are accumulated in the form of resources that individuals enable to utilize (Coleman, 1990). As social and economic disparity increases, community hierarchy and class disparity occur; it follows a mechanism by which opportunities for social exchange are small and social distance increases (Wilkinson, 2005). Previous researchers emphasized that the greater the difference in the economic hierarchy of the region, the greater the difference in lifestyle, culture, and interests between socioeconomic classes leads to a decrease in social interactions.

Social capital has a feature working based on social class and socioeconomic status (Bourdieu, 1986; Coleman, 1988; Lin, 2001). According to Kawachi et al. (2008), economic inequality and social capital are highly likely to have a negative association because opportunities for social exchange would reduce among similar classes in large unequal communities. According to Lin (2001), the dominant social capital relationship is a homogeneous interaction, and artificial efforts must accompany heterogeneous interaction. In other words, the more similar the socioeconomic level of communities, the more active social interactions, and the greater the socioeconomic level gap, the fewer social interactions. As a result, the dominant causal association between economic inequality and social capital is that social capital decreases as regional economic inequality increases (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2010).

An increase in wealthy inequality is strongly correlated with a decrease in social quality, such as an increase in social distance and a reduction in social trust, community participation, and social networks. As inequality increased in the United States in the 1970s, geographic disparities and segregation between the rich and poor also increased (Massey, 1996). The World Income Inequality Database’s analysis of the impact of income levels and income inequality on social trust in 20 countries showed that individual income levels alone were insufficient to explain social trust, while regional income disparities reduced social confidence by approximately 13% (Eric, 2013). The results of a study analyzing income inequality and hostility levels in 10 U.S. cities confirmed the relationship between average hostility values and income inequality (Williams et al., 1995). Putnam examined the level of participation in voluntary local organizations and communities in 20 local governments in Italy and demonstrated that income inequality and community participation are closely related (Putnam, 2000; Putnam et al., 1993).

A society with large income gaps has numerous social diseases, such as psychological anxiety, income stratification, crime, and teenage pregnancy; additionally, citizens’ quality of life is low (Pickett & Wilkinson, 2010). The income gap raises personal anxiety and intensifies anxiety within a group, resulting in various social problems (Delhey et al., 2017). In a European study, regions with high income inequality were found to have high distrust, status anxiety, and reduced happiness. These results differ depending on a city’s overall income (Delhey & Dragolov, 2014). In an environment with high inequality, overall life satisfaction is low (Delhey & Dragolov, 2014), it is difficult to form a sense of togetherness (Uslaner & Brown, 2005), and the perception of conflict is high (Alber et al., 2007; Hadler, 2003). Urban spaces concentrated on low-income and low-class people lead to gated communities (Blakely & Snyder, 1997) and poor social interactions among classes (Wessel, 2000). A long-term study in the United States from 1972 to 2008 found that middle- and lower-income groups had higher happiness levels in a fair society (Oishi et al., 2011).

The widening gap between the high- and low-income classes in cities has highlighted a significant cause for the decline in the quality of social relationships (Putnam, 2000; Uslaner, 2003; Wilkinson, 2005). Social cohesion and trust have been demonstrated to decrease with increasing social stratification (Kaplan et al., 1996; Kawachi et al., 1997; Kennedy et al., 1996; Wilkinson, 1994). Moreover, disproportionate income distribution leads to the separation of residential areas in cities, consequently forming a structural mechanism that reduces social interaction between classes (Castells, 1989; Wessel, 2000). Additionally, low-income clusters are spatially isolated and have difficulty forming social capital with other classes (Curley, 2010; Wilson, 1987). Residents with low incomes face a vicious cycle of increased inequality because of reduced social pathways caused by the segregation of residences and social exclusion, as well as difficulty in accessing high-quality jobs and opportunities to accumulate human capital (Rungo & Pena-López, 2019; Wilson, 1987, 1996). Moreover, spatial separation among social classes and the lack of social interactions, integration, and dialogue lead to further public spending (Wessel, 2000).

Several studies have substantiated the hypothesis that an increase in the income gap increases social distance and decreases the quality of social relationships. Putnam’s (2000) study of 50 U.S. states indicated that the decline in social capital and the increase in income inequality after the twentieth century were nearly the same. According to Wilkinson (2005), the structural mechanism produced by income inequality increases social distance between income groups and deteriorates the quality of social relationships. Wilkinson explained that deepening income inequality widens the disparity in social status, which increases social distance by income group and consequently deteriorates the quality of social relationships, such as a weakened level of trust and reduced participation in community life (Wilkinson, 2005; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2010).

Methodology

Spatial Unit of the Study Area

South Korea experienced flexible social movements and a relatively fair socioeconomic distribution during the industrial growth periods of the 1970s and the 1980s. During this period, Korea’s income inequality was relatively low compared to that of other countries. In fact, the country was evaluated as achieving “growth with equity” or “shared prosperity” (Koo, 2019). However, since the mid-twentieth century, inequality has intensified because of the side effects of tremendous economic growth. In 2017, the Gini coefficient had increased to 0.36. Thus, South Korea can no longer be viewed as an equal society (Kang et al., 2020; Koo, 2019). Korea’s inequality level is close to that of the United States and is the highest among OECD countries. As such, accelerating inequality is currently recognized as Korea’s most severe social problem (Koo, 2019).

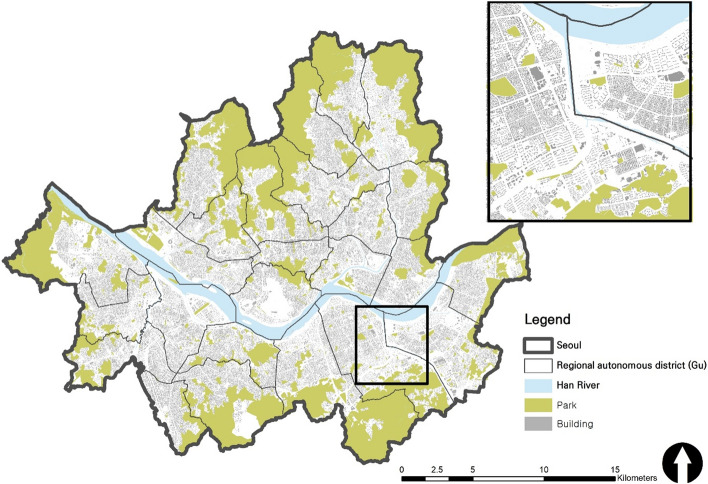

The spatial unit analyzed included 25 regional autonomous districts (Gu) in Seoul (Fig. 1). As shown in the figure, the 25 autonomous districts of Seoul are divided by nature, such as streams, mountains, and topography, and large-scale physical infrastructure such as highways. Therefore, each autonomous district has slightly different social, economic, and industrial characteristics. These regional residential districts are Seoul’s primary autonomous administrative districts, which combine the 425 smallest administrative districts into 25 districts with similar living standards. This study calculates the housing prices inequality index based on the regional residential districts of Seoul. Furthermore, the inequality index was combined with individual citizen survey data for each unit.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of housing units in Seoul, South Korea

Data Source and Variables Measurement

In South Korea, as the inequality owing to housing is as large as the inequality by income, this study measured the level of regional wealth inequality using the housing price, not the income. The inequality by housing price is the price gap between houses in the region, and a region with a large housing price gap means high wealth inequality in the region. The income gap and the housing price gap have different characteristics. While income represents the short-term financial status of individuals and households, assets such as housing represent the long-term financial status of accumulated wealth (McKenzie, 2005). Similar to income, housing is a commodity that reveals an individual’s economic class (Watt, 1996). However, though the income level is difficult to measure visually, the housing level is possible. The housing quality indicates a household’s economic level based on location, size, and a number of rooms (Laaksonen et al., 2009). As a result, the regional income gap is hard to measure with the naked eye, but there is a visual aspect to judge the regional housing price gap. Therefore, this study aims to measure the level of regional wealth inequality through the regional housing price gap, not the regional income gap.

To measure the degree of housing price inequality in autonomous districts, this study used actual housing transaction price data from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport (MOLIT). Because the MOLIT provides housing transaction prices for all autonomous districts in Seoul, this study calculated the housing price Gini coefficient for each autonomous district in Seoul in 2017 using the data. Although there is an index to calculate inequality, such as Pareto coefficients, Theil’s T-statistic, and dissimilarity index, we applied the Gini coefficient, which is the most used measure (Cushing et al., 2015; McAleer et al., 2017). Whereas the quintile share ratio or Pareto coefficient mainly considers a specific class, such as the top class or the bottom class, the Gini coefficient index considers all classes. As this study explores the characteristics of social capital according to the overall economic imbalance rather than a study focusing on a specific class, we utilized the Gini coefficient as a wealth inequality index. The Gini coefficient is a figure between 1 and 0, where 1 indicates perfect inequality and 0 indicates perfect equality. The formula for the Gini coefficient G for any individual house i and j is as follows: n is the number of individual houses in the area, is the average house price in a region, is the price of house i, and is the price of house j. The house price Gini coefficient is calculated by comparing the prices of all houses in pairs and dividing the difference by the average house price .

This study uses items from the Korea Housing Survey for the dependent variable and control variables. The Korea Housing Survey investigates social interaction levels and personal characteristics annually. This study utilized the responses of 14,788 of the 16,169 Seoul citizens from the 2017 Korea Housing Survey, excluding unfaithful responses. As the dependent variable, this study utilized items that responded to the degree of social interaction. The social interaction variable, which asked how much people exchanged with their neighbors, consisted of four choices ranging from very weak to very strong. Respondents who checked the level of social interaction highly mean that their relationship with their neighbors is excellent. This study also included control variables related to social interaction, such as age, gender, and income, in the analysis model. The respondents were male and female adults aged 19 years or older, and their educational backgrounds were divided into college graduates and non-graduates. “Monthly income” is the average monthly household income, and “total assets” are the total assets of the current household, including finance and real estate.

Moreover, we included the length of residence, type of housing, moving intention, and residence stability variables as residential environment factors that would affect social interaction. The housing types included single-family housing, multi-family housing, and apartment complexes. “Moving intention” consisted of planning to move out or lack of such intention. Finally, residential stability consisted of four choices, ranging from very weak to very strong, regarding the fear of eviction by the lessor. Table 1 shows the summary statistics and measurements of all variables in this analysis model.

Table 1.

Estimation result for interaction variable between housing price inequality and asset level

| Variable | Definition | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | |||||

| Social interaction level | 1 = very weak; 2 = weak; 3 = strong; 4 = very strong | 3.075 | 0.480 | 1 | 4 |

| Socio-demographic attribute | |||||

| Age | Years | 55.427 | 15.803 | 19 | 100 |

| Gender | 1 = female; 0 = male | 0.655 | 0.475 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of family members | Person | 2.637 | 1.226 | 1 | 9 |

| Education | 1 = above B.A. degree; no = under | 0.425 | 0.494 | 0 | 1 |

| Monthly income | Monthly household income (10,000 KRW*) | 332 | 240 | 0 | 9,000 |

| Total asset | Total household finance, property, etc. (10,000 KRW*) | 41,672 | 67,886 | 0 | 5,093,000 |

| Residential condition attributes | |||||

| Residence Length | Months | 7.770 | 8.476 | 0 | 59 |

| Housing types: single-family house | 1 = yes; 0 = no | 0.317 | 0.465 | 0 | 1 |

| Housing types: multi-family house | 1 = yes; 0 = no | 0.226 | 0.418 | 0 | 1 |

| Housing types: apartment complex | 1 = yes; 0 = no | 0.422 | 0.494 | 0 | 1 |

| Housing types: non-residential house | 1 = yes; 0 = no (reference category) | 0.035 | 0.185 | 0 | 1 |

| Moving intention | 1 = yes; 0 = no | 0.136 | 0.343 | 0 | 1 |

| Residence stability | Concern about eviction by landlord = very weak; 2 = weak; 3 = strong; 4 = very strong | 1.460 | 0.736 | 1 | 4 |

| Housing inequality attributes | |||||

| Housing price gap | Gini index of housing price in 2017 | 0.178 | 0.036 | 0.072 | 0.304 |

| Change rate of housing price gap | (%) Change rate of Gini index in 2007–2017 | − 13.099 | 20.638 | − 70.663 | 45.617 |

*10,000 KRW is roughly equivalent to 9$ in 2020 exchange rate, Std. Dev. = Standard deviation, Observation = 14,788

Method

As a dependent variable in this study, the degree of social interaction was measured on a 4-point scale. It ranged from 1 (very weak) to 4 (very strong). Therefore, this study used an ordered logistic regression analysis model with a maximum likelihood estimation. In addtion, we analyzed a robustness test to ensure the empirical analysis results' reliability, and the results were finally used. Furthermore, as the housing price inequality index involves regional data, a fixed effects model was applied to consider the region-invariant explanatory variables and heterogeneity characteristics of regions, which were not observed in the regression model. We considered unobserved regional group heterogeneity by adding regional dummy variables to the ordered logistic regression model as a region-fixed effect. The formula for social interaction according to respondent i in region t is as follows. is the dependent variable of respondent i in region t, which is a measure of the social interaction level. is the housing price inequality index of autonomous district t. is the socioeconomic characteristic of individual i in region t and each price of the respondent. is a location-specific fixed effect that considers the heterogeneous characteristics of autonomous districts. is a dummy variable with a value of 1 if it corresponds to the i-th autonomous district and 0 otherwise.

Empirical Results

Analysis Results of the Association Between Housing Price Inequality and Social Interaction

The first empirical analysis explored the relationship between housing price inequality and social interaction using an ordinal logistic regression method. Model 1 in Table 2 presents the results of the analysis of the relationship between housing price inequality and social interaction.1 In particular, Model 1 is an empirical analysis of whether the level of social capital is low in areas with currently high inequality, and Model 2 is an empirical analysis of whether the level of social capital is low in areas with high inequality compared to the past. The correlation between housing price inequality and social interaction is statistically significant, and the odds ratio (OR) is 0.788, which indicates a negative correlation. This result indicates that the odds of the social interaction level decrease by 21.2% when the housing price inequality index is high (0.1 in those regions). Therefore, a person living in a region with a high housing price inequality index is less likely to interact with neighbors than a person in a low inequality region. This result confirms the first assumption that high housing price inequality and social interaction are negatively correlated.

Table 2.

Estimation result for ordered logit regression

| Social interaction | Model 1: 2017 | Model 2: 10 years change ratio | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | O.R | Std. Err | P >|Z| | Coef | O.R | Std. Err | P >|Z| | |

| Housing price inequality attributes | ||||||||

| Housing inequality (2017) | − 0.238*** | 0.788 | 0.059 | 0.002 | ||||

| Housing inequality change rate (10 years) | − 0.011*** | 0.989 | 0.001 | 0.000 | ||||

| Socio-demographic attributes | ||||||||

| Age | 0.004*** | 1.004 | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.004*** | 1.004 | 0.002 | 0.016 |

| Female | 0.082*** | 1.085 | 0.046 | 0.055 | 0.076*** | 1.079 | 0.046 | 0.073 |

| Number of family members | 0.003*** | 1.003 | 0.021 | 0.873 | 0.006*** | 1.006 | 0.021 | 0.766 |

| Education | 0.114*** | 1.121 | 0.058 | 0.028 | 0.088*** | 1.092 | 0.057 | 0.088 |

| Log (Monthly income) | 0.086*** | 1.090 | 0.038 | 0.015 | 0.081*** | 1.085 | 0.038 | 0.021 |

| Log (Total asset) | 0.063*** | 1.065 | 0.017 | 0.000 | 0.060*** | 1.062 | 0.017 | 0.000 |

| Residential condition attributes | ||||||||

| Residence Length | 0.001*** | 1.001 | 0.003 | 0.685 | 0.001*** | 1.001 | 0.003 | 0.816 |

| Housing types (Single-family house = 1) | − 0.563*** | 0.569 | 0.073 | 0.000 | − 0.509*** | 0.601 | 0.077 | 0.000 |

| Housing types (Multi-family house = 1) | − 0.581*** | 0.559 | 0.073 | 0.000 | − 0.532*** | 0.588 | 0.077 | 0.000 |

| Housing types (Apartment complex = 1) | − 0.052*** | 0.950 | 0.123 | 0.688 | -0.042*** | 0.958 | 0.124 | 0.742 |

| Moving intention | -0.300*** | 0.741 | 0.050 | 0.000 | − 0.308*** | 0.735 | 0.049 | 0.000 |

| Residence stability | − 0.331*** | 0.718 | 0.023 | 0.000 | − 0.336*** | 0.715 | 0.023 | 0.000 |

| Cut 1 | − 6.783 | 0.355 | − 6.001 | 0.302 | ||||

| Cut 2 | − 3.884 | 0.332 | − 3.103 | 0.277 | ||||

| Cut 3 | 0.804 | 0.330 | 1.603 | 0.274 | ||||

| Observations | 14,788 | 14,788 | ||||||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.066 | 0.069 | ||||||

Coef. = Coefficient, O.R. = Odds ratio, Std. Err. = Robust standard error

* p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

This analysis explored the relationship between the change rate of housing price inequality and social interaction to confirm whether the increase in housing price inequality is negatively associated with social interaction. Model 2 presents the analysis estimation results of the social interaction level according to the change rate of housing price inequality. The correlation between the change rate of housing price inequality and social interaction is also statistically significant. The OR for the change rate was 0.989, indicating that the odds of the social interaction level decreased by 1.1% when the change rate of the housing price inequality index increased by 1% in those regions. This finding confirms the second assumption that regions where the housing price inequality index increased are low in social interaction with neighbors. Therefore, both high current housing price inequality and growing housing price inequality are negatively associated with social interaction levels.

Model 1 presents the correlation between social interaction level and individual socio-demographic and residential condition attributes. Regarding socio-demographic attributes, age, gender, educational background, monthly income, and total assets are statistically associated with the degree of social interaction. The OR for age was 1.004, indicating that the odds of social interaction level increased by 0.4% per year. Regarding gender, the OR for females was 1.085, indicating that the odds of social interaction levels increased by 8.5% for females compared to males. The OR for college graduation respondents was 1.121, indicating that the odds of social interaction level increased by 12.1% for those with a bachelor's degree. The OR of monthly income was 1.090, indicating that the odds of social interaction level increased by 9.0% when monthly income increased by 1%. Finally, the OR of total assets was 1.065, indicating that the odds of the social interaction level increased by 6.5% when total assets increased by 1%. Concerning residential conditions, single-family house residence, multi-family house residence, moving intention, and residence stability were significantly associated with social interaction level. The ORs of single-family house and multi-family house inhabitants were 0.569 and 0.559, respectively. The OR of moving intention was 0.741, indicating that the odds of social interaction level decreased by 25.9% for those with moving intention compared to those who had no moving intention. The OR of residential stability was 0.718, indicating that the social interaction level decreased for respondents with high residential instability.

Analysis Results of the Association Between Housing Price Inequality and Social Interaction by Asset Level

The third empirical analysis explores the relationship between housing price inequality and social interaction by asset level in order to confirm whether the negative aspects of inequality differ depending on the level of wealth. Table 3 presents the results of the analysis of the relationship between housing price inequality and social interaction by the total asset level.2 This model was analyzed by classifying respondents into lower and higher asset groups based on the asset average. The correlation of the housing price inequality index with the social interaction level in the low total assets group is statistically significant (Model 3). The OR of housing price inequality is 0.532, indicating that the odds of the social interaction of the low-asset group decreased by 46.8% in those regions where the inequality index increased by 0.1. The OR for the low-asset group was 25.6% points higher than that of Model 1 for all respondents. However, the correlation of the housing price inequality index with the social interaction level in the high total assets group was not statistically significant (Model 4). These results indicate that the social interaction of the low-asset group is negatively associated with the housing price inequality index. In contrast, the social interaction of the high-asset group is little affected by the inequality index. Consequently, the unequal environment based on the housing price gap has an unfairly deleterious effect on people by the asset level. In addition, the difference in the negative association between social interaction and housing price inequality according to asset level was statistically significant (Appendix A).

Table 3.

Estimation result for ordered logit regression by total asset level

| Social interaction | Model 3: Low-asset respondents | Model 4: High-asset respondents | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | O.R | Std. Err | P >|Z| | Coef | O.R | Std. Err | P >|Z| | |

| Housing inequality attribute | ||||||||

| Housing price inequality (2017) | − 0.631*** | 0.532 | 0.059 | 0.000 | 0.098*** | 1.103 | 0.114 | 0.343 |

| Socio-demographic attributes | ||||||||

| Age | 0.000*** | 1.000 | 0.002 | 0.878 | 0.013*** | 1.014 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Female | 0.120*** | 1.128 | 0.067 | 0.043 | 0.077*** | 1.080 | 0.068 | 0.220 |

| Number of family members | 0.024*** | 1.024 | 0.030 | 0.413 | -0.001*** | 0.999 | 0.031 | 0.967 |

| Education | 0.093*** | 1.097 | 0.083 | 0.220 | 0.181*** | 1.199 | 0.087 | 0.012 |

| Log (Monthly income) | 0.037*** | 1.038 | 0.048 | 0.418 | 0.178*** | 1.195 | 0.067 | 0.002 |

| Residential condition attributes | ||||||||

| Residence Length | 0.007*** | 1.007 | 0.005 | 0.140 | − 0.003*** | 0.997 | 0.004 | 0.388 |

| Housing types (Single-family house = 1) | − 0.453*** | 0.636 | 0.091 | 0.002 | − 0.414*** | 0.661 | 0.187 | 0.143 |

| Housing types (Multi-family house = 1) | − 0.342*** | 0.710 | 0.105 | 0.021 | -0.460*** | 0.631 | 0.180 | 0.106 |

| Housing types (Apartment complex = 1) | 0.043*** | 1.044 | 0.161 | 0.781 | 0.080*** | 1.084 | 0.299 | 0.771 |

| Moving intention | − 0.242*** | 0.785 | 0.070 | 0.007 | − 0.346*** | 0.708 | 0.074 | 0.001 |

| Residence stability | − 0.330*** | 0.719 | 0.029 | 0.000 | − 0.294*** | 0.745 | 0.046 | 0.000 |

| Cut 1 | − 8.739*** | 0.473 | − 5.222*** | 0.631 | ||||

| Cut 2 | − 5.865*** | 0.449 | − 2.217*** | 0.582 | ||||

| Cut 3 | − 1.294*** | 0.440 | 2.749*** | 0.581 | ||||

| Observations | 7,362 | 7,426 | ||||||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.054 | 0.069 | ||||||

| Total asset range (10,000 KRW) | Under 27,000 | Above 27,000 | ||||||

Coef. = Coefficient, O.R. = Odds ratio, Std. Err. = Robust standard error

* p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

Conclusion and Discussion

This study shows that the social interaction level is low in regions with high housing price gaps. This result is similar to those of previous studies showing that income inequality is negatively correlated with social capital (Eric, 2013; Kawachi et al., 1997; Kennedy et al., 1998; Wilkinson, 2005). Similar to the income gap, the housing price gap is negatively correlated with the social interaction level, even though housing is an accumulated form of wealth and income is a short-term form of wealth. Wilkinson (2005) described the mechanism by which large income inequality induced social distance by income class and decreased the degree of social interaction. This mechanism may work similarly in regions of high housing price inequality. In addition, although an individual’s income is invisible, housing represents an individual’s social status because of housing visual features (Park, 2006; Watt, 1996). It is possible to roughly predict the price of apartment units based on the location, brand, and quality of the surrounding environment in South Korea (Choi et al., 2017; Shin & Kim, 2016). Therefore, although people would not know the other person’s income, they would distinguish their socioeconomic position depending on their housing conditions. As the housing price gap is visually more pronounced than the income gap, housing price inequality may have a more direct association with social interaction.

As verified in this study, as the housing price gap is associated with social interactions in the community, housing policymakers and urban planners should closely consider the high housing price gap as well as the income gap. Like other countries, the South Korean government does not provide income inequality data at micro-spatial units because of privacy protection policies. It is challenging to identify a wealth inequality owing to the substantial economic costs of a survey and limited information (Carter & Zimmerman, 2000; McKenzie, 2005). However, as MOLIT provides the nationwide housing transaction price data to the public monthly, it is possible to estimate the wealth gap in micro-spatial units using housing transaction data, where it is difficult to measure the income and asset gap. Notably, each local government can monitor the regional economic gap and understand which regions have high economic inequality.

This study indicated that not only a high housing price gap, but also a rising housing price gap had a negative relationship with social interaction. This finding suggests that the growing housing price gap can be as harmful for social interaction as the current high housing price gap. Particularly, social interaction is likely to decrease in areas where the housing price gap increases even if the current housing price level is low. These results complement those of previous studies that have dealt insufficiently with the rate of changing inequality. Piketty (2014) emphasized the need to consider the growing acceleration of inequality in 21st-century capitalism. Therefore, socioeconomic inequality is expected to deepen and accelerate without significant change in the future. In particular, the acceleration of inequality in South Korea cannot be ignored. As of 2018, South Korea ranked 34th in the wage comparison index for the top and bottom 10% of the 37 OECD countries (OECD, 2020a). The COVID-19 outbreak has led to a rapid worsening of inequality, thus requiring a more inclusive society (OECD, 2020b). In conclusion, the level of social interaction is likely to deteriorate rapidly as the inequality index increases.

As the third research assumption, this study explored the differences in the relationship between housing price inequality and social interaction depending on the level of an asset. The association between social interaction level and housing price inequality was not statistically significant in the high-asset group, whereas the social interaction level decreased as housing price inequality increased in the low-asset group. The findings of this study differ from those of previous studies in that the negative impact of inequality harms everyone regardless of income level. A study by Subramanian and Kawachi (2006) suggested that an unequal environment is like a polluting substance that could hurt everyone, regardless of income level. Wilkinson and Pickett (2010) also emphasized that most people would be harmed if exposed to unequal environments, regardless of class. However, the study results indicate that the social interaction level of a high-asset group is less likely to be damaged by an unequal environment. Moreover, the OR of the low-asset group is negatively higher than that of the entire group, meaning that the low-asset group could be more damaged by the unequal environment. These results indicate that the damage caused by an unequal environment causes further inequality.

Several policy implications related to the results of this study are as follows. Like regional housing prices can be adjusted by housing supply (Caldera & Johansson, 2013), customized supply would also mitigate the regional housing price gap. Public policymakers could construct a management plan to supply housing at a price level that can alleviate inequality in areas where housing prices are too skewed and where the inequality index is high. In this regard, the government should also consider mitigating the housing price gap through the supply and security of affordable housing. For example, suppose an area mainly comprises middle or high-income class housing. In that case, as it can negatively affect the social interaction of the entire community, the government should make efforts to secure affordable housing. In addition, support systems such as housing subsidies can be utilized to compensate for the imbalance in the housing asset gap. As pointed out by Piketty (2014), since the current economic system represents a structure in which assets produce assets, governments and policymakers should consider using support systems such as housing subsidies to compensate for the housing wealth gap and to avoid the negative aspects of inequality.

This study attempted to demonstrate the relationship the housing price inequality and social interaction based on the current level of inequality, the level of inequality change rate, and the level of wealth. However, this study has several limitations, as follows. Because this study focused on only the housing price inequality, it was not compared and analyzed with the housing price inequality and income inequality. In addition, this study did not find a structural explanation or logical relevance to the phenomenon of lowering the level of social interaction in regions with large housing price gaps. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze further the mechanism between the housing price gap and social exchange.

Appendix A

This appendix is a further analysis of the third empirical analysis. The third empirical analysis examines the negative association between the housing price inequality index and social interaction by the asset. As a result of this empirical analysis, the negative association between the housing price inequality index and social interaction was statistically significant in the lower asset group but not statistically significant in the upper asset group. In order to confirm whether the difference in the analysis results by asset level is statistically significant, we analyzed this association by inserting an interaction variable between the asset level and the housing price inequality index. As a result of the analysis, the interaction variables were statistically significant. Consequently, it means that the difference in analysis results by asset level was statistically significant.

See Table 4

Table 4.

Estimation result for interaction variable between housing price inequality and asset level

| Social interaction | Coef | O.R | Std. Err | P >|Z| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction variable | ||||

| Housing price inequality (2017) ⓗ | − 0.533*** | 0.587 | 0.103 | 0.000 |

| Asset level (0: low asset group, 1: high asset group) ⓐ | − 0.754*** | 0.470 | 0.210 | 0.000 |

| ⓗ x ⓐ | 0.524*** | 1.688 | 0.115 | 0.000 |

| Socio-demographic attributes | ||||

| Age | 0.005*** | 1.005 | 0.002 | 0.009 |

| Female | 0.088*** | 1.092 | 0.043 | 0.039 |

| Number of family members | 0.002*** | 1.002 | 0.021 | 0.916 |

| Education | 0.131*** | 1.139 | 0.051 | 0.011 |

| Log (Monthly income) | 0.107*** | 1.113 | 0.034 | 0.002 |

| Residential condition attributes | ||||

| Residence Length | 0.001*** | 1.001 | 0.003 | 0.683 |

| Housing types (Single-family house = 1) | − 0.523*** | 0.593 | 0.129 | 0.000 |

| Housing types (Multi-family house = 1) | − 0.509*** | 0.601 | 0.131 | 0.000 |

| Housing types (Apartment complex = 1) | − 0.015*** | 0.985 | 0.129 | 0.908 |

| Moving intention | − 0.293*** | 0.746 | 0.067 | 0.000 |

| Residence stability | − 0.327*** | 0.721 | 0.034 | 0.000 |

| Cut 1 | − 7.665 | 0.384 | ||

| Cut 2 | − 4.767 | 0.363 | ||

| Cut 3 | − 0.076 | 0.359 | ||

| Observations | 14,788 | |||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | |||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.066 | |||

Coef. = Coefficient, O.R. = Odds ratio, Std. Err. = Robust standard error

* p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

Footnotes

The total number of samples in Models 1 and 2 is 14,788, and Pseudo R2 in Models 1 and 2 is 0.066 and 0.069, respectively.

The total number of samples in Models 3 and 4 is 7,362 and 7,426, respectively, and Pseudo R2 in Models 3 and 4 is 0.054 and 0.069, respectively.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sungik Kang, Email: namugnel@gamil.com.

Ja-Hoon Koo, Email: jhkoo@hanyang.ac.kr.

References

- Alber J, Fahey T, Saraceno C. The perception of group conflicts: Different challenges for social cohesion in new and old member states. In: Alber J, Fahey T, Saraceno C, editors. Handbook of quality of life in the enlarged European union. Routledge; 2007. pp. 344–368. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina A, Ferrara EL. Participation in heterogeneous communities. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2000;115:847–904. doi: 10.1162/003355300554935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour MM. Social epidemiology. Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Blakely EJ, Snyder MG. Fortress America: Gated communities in the United States. Institution Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. The forms of capital. In: Richardson J, editor. Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of economic reproduction of education. Greenwood Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Caldera A, Johansson Å. The price responsiveness of housing supply in OECD countries. Journal of Housing Economics. 2013;22(3):231–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jhe.2013.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter MR, Zimmerman FJ. The dynamic cost and persistence of asset inequality in an agrarian economy. Journal of Development Economics. 2000;63(2):265–302. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3878(00)00117-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castells M. The informational city: Information technology, economic restructuring, and the urban-regional process. Basil Blackwell; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Castells M, Mollenkopf J. Conclusion: Is New York a dual city? In: Castells M, Mollenkopf J, editors. Dual City: Restructuring New York. Russell Sage Foundation; 1991. pp. 399–418. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu SWK, Lui TL. Testing the global city-social polarization thesis: Hong Kong since the 1990s. Urban Studies. 2004;41:1863–1888. doi: 10.1080/0042098042000256297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M, Park M, Lee HS, Hwang S. Dynamic modeling for apartment brand management in the housing market. International Journal of Strategic Property Management. 2017;21(4):357–370. doi: 10.3846/1648715X.2017.1315347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:S95–S120. doi: 10.1086/228943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS. Foundations of social theory. Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Costa DL, Kahn ME. Civic engagement and community heterogeneity: An economist’s perspective. Perspectives on Politics. 2003;1:103–111. doi: 10.1017/S1537592703000082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curley AM. Relocating the poor: Social capital and neighborhood resources. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2010;32:79–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9906.2009.00475.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cushing L, Morello-Frosch R, Wander M, Pastor M. The haves, the have-nots, and the health of everyone: The relationship between social inequality and environmental quality. Annual Review of Public Health. 2015;36:193–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delhey J, Dragolov G. Why inequality makes Europeans less happy: The role of distrust, status anxiety, and perceived conflict. European Sociological Review. 2014;30:151–165. doi: 10.1093/esr/jct033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delhey J, Schneickert C, Steckermeier LC. Sociocultural inequalities and status anxiety: Redirecting the spirit level theory. International Journal of Comparative Sociology. 2017;58:215–240. doi: 10.1177/0020715217713799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond J. Upheaval: How nations cope with crisis and change. Penguin; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon J. Contact and boundaries: ‘Locating’ the social psychology of intergroup relations. Theory & Psychology. 2001;11:587–608. doi: 10.1177/0959354301115001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Egolf B, Lasker J, Wolf S, Potvin L. The Roseto effect: A 50-year comparison of mortality rates. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82(8):1089–1092. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.82.8.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eric KB. Inequality and trust: Testing a mediating relationship for environmental sustainability. Sustainability. 2013;5:779–788. doi: 10.3390/su5020779. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Florida RL. The new urban crisis: How our cities are increasing inequality, deepening segregation, and failing the middle class– and what we can do about it. Basic Books; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hadler, M. (2003). Ist der Klassenkonflikt überholt? Die Wahrnehmung von vertikalen Konflikten im internationalen Vergleich. Soziale Welt, 175–200.

- Kang S, Koo JH. Distribution characteristics and correlation between regional inequality and social capital, Seoul, Korea. Seoul Studies. 2020;21:223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Kang WC, Lee JS, Song BK. Envy and pride: How economic inequality deepens happiness inequality in South Korea. Social Indicators Research. 2020;150:617–637. doi: 10.1007/s11205-020-02339-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan GA, Pamuk ER, Lynch JW, Cohen RD, Balfour JL. Inequality in income and mortality in the United States: Analysis of mortality and potential pathways. BMJ. 1996;312:999–1003. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7037.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Lochner K, Prothrow-Stith D. Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:1491–1498. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.9.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Kim D. Social capital and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour MM, Subramanian SV, Kim D, editors. Social capital and health. Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi, I., & Wamala, S. (2007). Poverty and inequality in a globalizing world. Globalisation and health, 122–137.

- Kennedy BP, Kawachi I, Prothrow-Stith D. Income distribution and mortality: Cross sectional ecological study of the Robin Hood index in the United States. BMJ. 1996;312:1004–1007. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7037.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy BP, Kawachi I, Prothrow-Stith D, Lochner K, Gupta V. Social capital, income inequality, and firearm violent crime. Social Science & Medicine. 1998;47(1):7–17. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Jang HS. Why do residents participate in neighborhood associations? The case of apartment neighborhood associations in Seoul, South Korea. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2017;39:1155–1168. doi: 10.1080/07352166.2017.1319229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koo H. Rising inequality and shifting class boundaries in South Korea in the neo-liberal era. Journal of Contemporary Asia. 2019;51(1):1–19. doi: 10.1080/00472336.2019.1663242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements. (2020). Policies to reduce inequalities in real estate assets for social cohesion. KRIHS.

- Krumholz N. Toward an equity-oriented planning practice in the United States. In: Carmon N, Fainstein SS, editors. Policy, planning, and people: Promoting justice in urban development. University of Pennsylvania Press; 2013. pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Laaksonen M, Tarkiainen L, Martikainen P. Housing wealth and mortality: A register linkage study of the Finnish population. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(5):754–760. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemanski C. Global cities in the south: Deepening social and spatial polarization in Cape Town. Cities. 2007;24(6):448–461. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2007.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N. Social capital: A theory of social structure and action. Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Maclennan D, Miao, J. Housing and capital in the 21st century. Housing, Theory and Society. 2017;34:127–145. doi: 10.1080/14036096.2017.1293378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mansyur C, Amick BC, Harrist RB, Franzini L. Social capital, income inequality, and self-rated health in 45 countries. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66(1):43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS. The age of extremes: Concentrated affluence and poverty in the twenty-first century. Demography. 1996;33(4):395–412. doi: 10.2307/2061773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAleer, M., Ryu, H. K., & Slottje, D. J. (2017). A new inequality measure that is sensitive to extreme values and asymmetries. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper.

- McKenzie DJ. Measuring inequality with asset indicators. Journal of Population Economics. 2005;18(2):229–260. doi: 10.1007/s00148-005-0224-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Medina RM, Byrne K, Brewer S. Housing inequalities: Eviction patterns in Salt Lake County, Utah. Cities. 2020;104:102804. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2020.102804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nijman J, Wei YD. Urban inequalities in the 21st century economy. Applied Geography. 2020;117:102188. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2020.102188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2020. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2020 doi: 10.1787/2dde9480-en. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2020a). How's Life? 2020a Measuring Well-being. Retrieved March 9, 2020a from 10.1787/9870c393-en.

- Oishi S, Kesebir S, Diener E. Income inequality and happiness. Psychological Science. 2011;22:1095–1100. doi: 10.1177/0956797611417262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HY. Housing welfare indicators for the quality of life in Korea. Korea Housing Studies. 2006;14(1):5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Piketty T. Capital in the 21st century. Harvard University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Springer; 2000. pp. 223–234. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. Our kids: The American dream in crisis. Simon and Schuster; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD, Leonardi R, Nanetti RY. Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rungo P, Pena-López A. Persistent inequality and social relations: An intergenerational model. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology. 2019;43:23–39. doi: 10.1080/0022250X.2018.1470511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandel MJ. The tyranny of merit: What’s become of the common good? Penguin; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen S. Economic restructuring and the American city. Annual Review of Sociology. 1990;16:465–490. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.16.080190.002341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sassen S. The informal economy. In: Castells M, Mollenkopf J, editors. Dual city: Restructuring New York. Russell Sage Foundation; 1991. pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen S. Cities in a world economy. Pine Forge Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen S. Globalization and its discontents. New Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schelling TC. Dynamic models of segregation. Journal of Mathematical Sociology. 1971;1:143–186. doi: 10.1080/0022250X.1971.9989794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott AJ, Agnew J, Soja EW, Storper M. Global city-regions: An overview. Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett R. Flesh and stone: The body and the city in Western civilization. WW Norton; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey, P. (2013). Rich neighborhood, poor neighborhood: How segregation threatens social mobility. Social Mobility Memos, December 5.

- Shin KY. A new approach to social inequality: Inequality of income and wealth in South Korea. The Journal of Chinese Sociology. 2020;7(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s40711-020-00126-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin HB, Kim SH. The developmental state, speculative urbanisation and the politics of displacement in gentrifying Seoul. Urban Studies. 2016;53(3):540–559. doi: 10.1177/0042098014565745. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley D. Geographies of exclusion: Society and difference in the West. Routledge; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. Whose health is affected by income inequality? A multilevel interaction analysis of contemporaneous and lagged effects of state income inequality on individual self-rated health in the United States. Health & Place. 2006;12(2):141–156. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uslaner EM. The moral foundations of trust. Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Uslaner EM. Trust, democracy and governance: Can government policies influence generalized trust? In: Hooghe M, Stolle D, editors. Generating social capital. Springer; 2003. pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Uslaner EM, Brown M. Inequality, trust, and civic engagement. American Politics Research. 2005;33:868–894. doi: 10.1177/1532673X04271903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watt P. Social stratification and housing mobility. Sociology. 1996;30(3):533–550. doi: 10.1177/0038038596030003007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel T. Social polarization and socioeconomic segregation in a welfare state: The case of Oslo. Urban Studies. 2000;37:1947–1967. doi: 10.1080/713707228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RG. The epidemiological transition: From material scarcity to social disadvantage? Daedalus. 1994;123:61–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RG. The impact of inequality: How to make sick societies healthier. The New Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. Income inequality and population health: A review and explanation of the evidence. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62(7):1768–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. The spirit level: Why equality is better for everyone. London: Penguin Books; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Williams AM. International migration, uneven regional development and polarization. European Urban and Regional Studies. 2009;16:309–322. doi: 10.1177/0969776409104695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AM, Baláž V. Low-cost carriers, economies of flows and regional externalities. Regional Studies. 2009;43:677–691. doi: 10.1080/00343400701875161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RB, Feaganes J, Barefoot JC. Hostility and death rates in 10 U.S. cities. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1995;57:94. [Google Scholar]

- Williams AM, Baláž V, Wallace C. International labour mobility and uneven regional development in Europe: Human capital, knowledge and entrepreneurship. European Urban and Regional Studies. 2004;11:27–46. doi: 10.1177/0969776404039140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. When work disappears: The world of the new urban poor. Alfred A. Knopf; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Won J, Lee JS. Impact of residential environments on social capital and health outcomes among public rental housing residents in Seoul, South Korea. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2020;203:103882. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Greaney TM. Economic growth and income inequality in the Asia-Pacific region: A comparative study of China, Japan, South Korea, and the United States. Journal of Asian Economics. 2017;48:6–22. doi: 10.1016/j.asieco.2016.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]