Abstract

Individuals differ widely in their drug-craving behaviors. One reason for these differences involves sleep. Sleep disturbances lead to an increased risk of substance use disorders and relapse in only some individuals. While animal studies have examined the impact of sleep on reward circuitry, few have addressed the role of individual differences in the effects of altered sleep. There does, however, exist a rodent model of individual differences in reward-seeking behavior: the sign/goal-tracker model of Pavlovian conditioned approach. In this model, only some rats show the key behavioral traits associated with addiction, including impulsivity and poor attentional control, making this an ideal model system to examine individually distinct sleep-reward interactions. Here, we describe how the limbic neural circuits responsible for individual differences in incentive motivation overlap with those involved in sleep-wake regulation, and how this model can elucidate the common underlying mechanisms. Consideration of individual differences in preclinical models would improve our understanding of how sleep interacts with motivational systems, and why sleep deprivation contributes to addiction in only select individuals.

Keywords: Incentive salience, sign-tracking, goal-tracking, individual differences, reward, reinforcement, sleep

Sleep disturbances can lead to, or exacerbate, a multitude of psychological disorders involving impulse control, behavioral inhibition, and addiction. Even partial sleep deprivation alters multiple aspects of executive function (Tkachenko and Dinges 2018), and chronic insomnia is linked to an increased risk of alcohol and substance use disorders (Marmorstein 2017; Stein and Friedmann 2006) and obesity (Katsunuma et al. 2017). The causal, mechanistic relationship between sleep and addictive disorders is difficult to study in human clinical populations. This is because a history of drug or alcohol consumption results in long-term alterations in sleep during active use, during withdrawal, and even after years of abstinence (Knapp et al. 2007; Knapp et al. 2014). Therefore, it is difficult to determine whether underlying sleep-related traits contribute to the initial development of substance use disorders, or whether sleep disturbances are the result of past exposure to drugs or alcohol. There are two important questions that are essential for understanding how sleep loss can lead to altered reward processing. First, are there underlying pre-existing differences in sleep characteristics that can predispose some individuals to either the initial development of addictive tendencies or to relapse? Second, are there individual differences in how the consumption of addictive substances, or a state of physical dependence, interacts with neural architecture to cause distinct post-addiction sleep patterns across individuals? The development of an animal model that can address these questions would be a major step toward understanding the impact of sleep quality on reward processing and addiction-related disorders.

1. The importance of studying individual variation

The study of sleep and cognitive functioning is strongly influenced by individual differences in human subjects. Several studies have looked at different aspects of cognitive processing after experimentally induced sleep deprivation, often focusing on different aspects of sustained attention, subjective ratings of sleepiness and mood, and performance in cognitive tasks. Results are strongly influenced by individual variability, which in many cases is stable over repeated testing with different SD parameters, suggesting that stable underlying behavioral traits determine why some people are more vulnerable to the negative effects of SD than others (reviewed in (Tkachenko and Dinges 2018; Van Dongen et al. 2005).

Several limbic brain regions play a key role in both reward and sleep. The dopamine-mediated mesolimbic circuitry responsible for reward and reinforcement is also heavily involved in the regulation of sleep/wake states and is strongly affected by sleep loss. In humans, a single night of sleep deprivation can decrease D2/D3 dopamine receptor availability in the ventral striatum (Volkow et al. 2008; Volkow et al. 2012; Wiers et al. 2016), which is associated with a greater propensity for risk-taking behavior (Linnet et al. 2011) and an increased risk for compulsive drug consumption (Dalley et al. 2007). Furthermore, sleep disturbances have been shown to mediate the reduced D2/D3 receptor availability that has been observed in chronic cocaine abusers (Wiers et al. 2016). However, in human populations, there is tremendous individual variation in the degree to which sleep deprivation impairs cognitive performance and enhances reward sensitivity. For example, genetic variation in the human dopamine transporter (DAT) gene has been shown to influence neural responses to sleep loss; with individuals with the DAT allele that is linked to higher phasic dopamine activity demonstrating greater striatal responses to monetary reward after sleep deprivation (Greer et al. 2016).

A recent study in humans by Satterfield et al. showed that the degree of activation of the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) by a task (but not pre-task baseline NAcc activity) predicted the number of calories consumed during a sleep deprivation session that took place days later. This suggests that stronger mesolimbic dopamine reactivity, when combined with the alterations in prefrontal functioning that result from sleep loss, can make some individuals more likely to overeat than others (Satterfield et al. 2018). This dynamic may be critically important for the regulation of motivated behavior. If sleep loss causes deficits in the “top-down” prefrontal regulation of behavior, it is likely to have greater consequences for those individuals that experience stronger “bottom-up” motivational drive to begin with.

Preclinical studies in rodents are frequently used to investigate the relationship between sleep and reward processing. However, the impact of individual variation has rarely been addressed in these models, and it would be beneficial to use the individual differences that are naturally found in animal populations to better understand the potential sources of variability in human populations. In particular, we believe the sign-tracker/goal-tracker model of incentive salience has translational relevance that cannot be captured by other models, and can provide a unique perspective on how sleep disruption can enhance reactivity to reward-paired cues. The balance between top-down and bottom-up circuitry has specifically been implicated as a mechanism underlying sign- and goal-tracking propensities (Haight et al. 2017); therefore, if humans show individual variability in how strongly the dynamic between these two processes is altered by sleep deprivation, then the ST/GT model may be a powerful tool for isolating the neural mechanisms responsible for this interaction. Here, we review evidence for a link between the brain regions involved in sleep and those responsible for the motivational impact of reward cues. We argue that by examining populations of rats that show natural phenotypic variation in the degree to which food cues engage mesolimbic circuitry, we can learn more about the role of sleep in the emotional and motivational states that are triggered by cues.

2. Studies of sleep deprivation (SD) and addictive behavior

Sleep deprivation has a major impact on reinforcement learning, often resulting in hypersensitivity to reward and cue-induced motivation. SD has been shown to enhance the sensitizing effects of amphetamine (Kameda et al. 2014), increase the drug-primed reinstatement of conditioned place preference for methamphetamine (Karimi-Haghighi and Haghparast 2018), and enhances the acquisition of cocaine self-administration and the rate of responding on a progressive ratio schedule (Puhl et al. 2013). In addition, the fragmentation of REM sleep that is caused by cocaine withdrawal expedites the development of the incubation of cocaine craving (Chen et al. 2015). SD also enhances motivation for food reward, and selectively increases the consumption of sucrose and highly palatable food, but not regular lab chow (Liu et al. 2016; McEown et al. 2016).

Sleep loss is known to cause major impairments in hippocampal-dependent memory, with several studies showing that SD prior to learning prevents the formation of new memories, and SD after learning impairs the consolidation of newly formed memories (Kreutzmann et al. 2015). Impairment in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex may also contribute to reward sensitivity, since SD impairs the type of complex cognitive processes that are mediated by these areas, such as spatial and contextual learning (Hagewoud et al. 2010a; Kreutzmann et al. 2015; McDermott et al. 2003). For example, the ability to withhold an operant response in order to receive a reward is reduced after SD, indicating reduced prefrontal inhibition and an increase in impulsive responding (Kamphuis et al. 2017). In some cases, even when sleep deprivation does not directly impair performance, it can influence the type of learning strategy recruited to perform a task, with the enhanced activity in striatal circuits acting as a compensatory mechanism to preserve performance on reward-related tasks that would normally engage hippocampal learning processes (Hagewoud et al. 2010b; Watts et al. 2012).

There is a bidirectional relationship between circadian rhythms and reward-related behavior, and given that circadian rhythms play such an integral role in regulating sleep, it is likely that individual traits related to circadian mechanisms play a role in the interaction between sleep and substance abuse (DePoy et al. 2017). Polymorphisms in circadian genes have been shown to contribute to addiction-related behaviors. For example, in mice, mutations of the clock gene can lead to a hyperdopaminergic state with elevated dopamine transmission in the VTA and NAcc, leading to enhance cocaine self-administration and conditioned place preference (McClung et al. 2005; Ozburn et al. 2012), and mutations in Per1 and Per2 can increase the consumption of alcohol (Dong et al. 2011; Spanagel et al. 2005b). In addition, rodent lines that are selectively bred for high or low alcohol preference (P/NP lines and HAD-2/LAD-2 lines) also show phenotypic variation in circadian rhythms, indicating that common genetic determinants underly the two processes (Rosenwasser et al. 2005). In humans, polymorphisms in clock genes are more prevalent in populations with alcohol use disorders (Kovanen et al. 2010). Polymorphisms in the Per2 gene have been associated with the regulation of alcohol consumption (Spanagel et al. 2005a), and reduced dopamine D2 receptor expression in the striatum (Shumay et al. 2012). Furthermore, circadian misalignment that occurs due to external factors, such as jet lag and shift work, is associated with a higher rate of substance abuse and is known to increases the risk of overeating and the consumption of high calorie food (Mendoza 2019; Partonen 2015; Webb 2017).

The link between circadian rhythms and addictive behavior is complicated by the fact that exposure to alcohol, drugs of abuse, and food reward, can directly cause disruption or entrainment of circadian timing (Gillman et al. 2019; Hasler et al. 2012; Webb 2017). Therefore, as with other aspects of sleep, it is not yet known which features of circadian rhythms represent underlying predisposing traits, and which results from drug exposure or environmental factors. Furthermore, sleep and circadian rhythms are closely intertwined. The timing of sleep is largely under the control of circadian mechanisms, while sleep deprivation inevitably causes disruption of normal circadian rhythmicity (Rosenwasser 2009). Therefore, when evaluating the effect of sleep manipulations on addictive behavior, it is difficult to parse the impact of SD alone (i.e. total amount of sleep time lost) from the affect this would have on circadian rhythms.

3. Individual differences in the attribution of incentive salience to cues

It has long been known that a food-paired cue (conditioned stimulus; CS) that has been repeatedly paired with food reward will reliably elicit a conditioned response in rats. However, it is also true that the form of the conditioned response can vary due to individual differences, with some rats approaching and interacting with the cue itself (“sign trackers”, STs) and some approaching the site of impending food delivery (“goal trackers”, GTs). In the standard conditioning procedure used to determine sign- and goal-tracking tendencies (Flagel et al. 2009; Meyer et al. 2012; Tomie et al. 2012), a retractable lever is used as the CS. In each trial (i.e. CS-reward pairing) the lever-CS is inserted into the cage for 8s, then is retracted and a banana pellet is immediately dispensed. The reward is delivered non-contingently and is independent of any action by the rat. Rats are categorized as STs or GTs based on whether they preferentially contact the lever or the food cup during the performance of their conditioned response (Meyer et al. 2012).

For both STs and GTs the CS acquires predictive value; however, only for STs does the CS also acquire incentive value, which causes STs, but not GTs, to become attracted to the lever and interact with it when it is present. By predictive value, we mean the learning of associations and the cognitive expectation of reward; in other words, an animal understands that the CS predicts the reward and reacts with a conditioned response. By incentive value, we mean that not only does a cue elicit the cognitive expectation of reward; it also elicits a dopamine-mediated motivational state akin to craving, which in rats can be expressed as desire for the cue itself (Flagel et al. 2009; Robinson et al. 2014; Saunders and Robinson 2013; Singer et al. 2016a; Singer et al. 2016b). This tendency to attribute incentive salience to a CS makes STs more susceptible to the motivational attraction of cues than GTs (Flagel et al. 2009; Saunders and Robinson 2013). As a result, STs work harder than GTs to gain access to the CS in a conditioned reinforcement paradigm (Beckmann and Chow 2015; Lomanowska et al. 2011; Robinson and Flagel 2009), STs are more resistant to Pavlovian extinction than GTs (Ahrens et al. 2016b), and discrete cues elicit greater reinstatement of food- and drug seeking behaviors in STs than GTs (Saunders and Robinson 2010, 2013; Yager and Robinson 2010, 2013).

Genetic differences underlie many of the traits that predispose STs to be more attracted to cues than GTs. Selective breeding for addiction-related traits also co-selects for the associated ST versus GT tendencies (Flagel et al. 2010), and certain commercial vendor colonies are more likely to produce STs than others (Fitzpatrick et al. 2013). The differences between STs and GTs are associated with other psychological tendencies that are not directly related to cue responses but may contribute to individual vulnerability to addiction. Compared to GTs, STs are more impulsive (Lovic et al. 2011), have diminished attentional control and reduced cholinergic activity in the prefrontal cortex (Koshy Cherian et al. 2017; Paolone et al. 2013), show greater locomotor reactivity to a novel environment (Flagel et al. 2010), show altered dopamine regulation even in the absence of rewarding stimuli (Flagel et al. 2010; Singer et al. 2016b), show greater expression of conditioned fear (Morrow et al. 2011; Morrow et al. 2015), and are more susceptible to incentive motivation during adolescence compared to adulthood (DeAngeli et al. 2017).

Sleep disturbances can strongly influence the expression of many of the behaviors that differ between STs and GTs, such as attentional control and impulsivity (Pilcher et al. 2015), and can alter dopamine activity (Volkow et al. 2008; Volkow et al. 2012; Wiers et al. 2016) and responses to drug-paired cues (Chen et al. 2015; Puhl et al. 2013; Volkow et al. 2012). However, the direct relationship between sleep and ST/GT behavior has never been studied. Given the existing literature, we predict that SD will impact these two groups differently, particularly with regard to cue- or drug-induced motivation, as well as other measures of reward-seeking behavior. Given the dramatic differences in their cholinergic and dopaminergic circuitry (Flagel and Robinson 2017; Pitchers et al. 2017), it is also likely that STs and GTs will show differences in their baseline sleep duration and sleep architecture, as well as differences in the precise nature of sleep disturbances caused by drug exposure or environmental stressors.

One important consideration is whether the rodent stocks or strains that show individual variability in ST/GT behavior also show variability in circadian rhythms or sleep patterns. Studies of Pavlovian conditioned approach have frequently been performed in relatively homogenous rodent populations (Fitzpatrick et al., 2013); however, there is the option to use more genetically diverse populations which could provide a wide range of individual variability in phenotypic traits. For example, recent studies have used heterogenous stock (HS) rats to examine behavioral correlates of ST/GT traits. HS rats are a genetically diverse colony created from eight inbred founder strains (Solberg Woods and Palmer 2019), which can provide more powerful insight into the relationships between genetically determined traits than inbred strains. Some of the traits that have previously been linked to sign-tracking in inbred populations (like premature responding in choice reaction time tasks) are still correlated within HS rat populations (King et al. 2016), while other traits (such as “novelty seeking” and “sensation seeking”) are not (Hughson et al. 2019); demonstrating the need for further investigation into genetic correlates.

Another option is to use genetically diverse populations of mice, such Collaborative Cross (CC) and Diversity Outbred (DO) strains. It was thought that PCA was not feasible in mice after it was shown that C57BL/6J mice did not develop the clear ST/GT phenotypes seen in rats (Tomie et al. 2012). However, sign-tracking in mice varies depending on strain and sex, with C57BL/6J mice showing much lower rates of sign-tracking than some of the CC and DO founder strains (Dickson et al. 2015). Therefore, it is possible to use the ST/GT model in genetically diverse populations of rats and mice to allow precise correlations between the genetic processes underlying cue responses and those involved in various sleep-related traits.

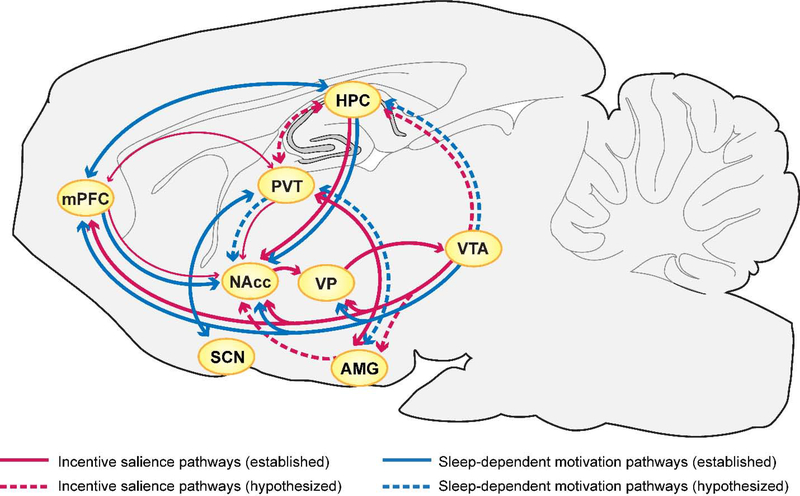

We next discuss the precise neural circuits (Fig. 1; Table 1) that are simultaneously involved in regulating sleep/wake states as well as encoding the responses to drug- and reward-related cues. As we point out, many of these structures have already been found to be differentially activated in sign-trackers vs goal-trackers, further highlighting their potentially crucial role in explaining individual differences linking sleep and addiction.

Figure 1.

Overlapping circuits for sleep/wake regulation and drug/reward-related encoding. There is substantial overlap in the neural pathways involved in the attribution of incentive salience to cues (red) and those that mediate the effects of sleep disturbances on motivated behavior and reward seeking (blue). Solid lines represent pathways that have been directly studied in these functions, and dashed lines represent connections that are hypothesized to play a role. There are individual differences in the degree to which rats are susceptible to the incentive motivational effects of reward cues, with some rats (STs) demonstrating stonger attraction to cues than others (GTs). Sign- and goal-tracking behavior are associated with different patterns of activity in mesolimbic circuitry, most notably expressed as greater activity in dopaminergic VTA projections (thick lines) and reduced activity in PVT and mPFC projections (thin lines) in STs relative to GTs. Since much of the same circuitry also plays a critical role in the ability of sleep to influence emotional and motivational states, this ST/GT model should reveal important information about how sleep affects reward processing, and how the loss of sleep can enhance the ability of reward cues to gain control over behavior. The regions shown represent pathways involved specifically in the ability of sleep to alter motivation for reward; brainstem mechanisms of sleep-wake regulation are not shown. Abbreviations: mPFC – medial prefrontal cortex; PVT – paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus; HPC – hippocampus; NAcc – nucleus accumbens; VP – ventral pallidum; VTA – ventral tegmental area; SCN – suprachiasmatic nucleus; AMG – amygdala.

Table 1.

Pathways with overlapping roles in motivational responses to cues and the effects of sleep deprivation on reward-related behavior.

| Pathways | Role in motivation | Effect of sleep deprivation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| VTA – NAcc – VP | Attribution of incentive salience to cues (STs > GTs) | Hyperactivity and enhanced reward seeking |

Flagel et al., 2017; Satterfield et al., 2019 |

| PFC – PVT – NAcc | Predictive value of reward-paired cues (GTs > STs) | Weakened inhibitory control over reward seeking |

Haight et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2016 |

| AMG – NAcc | Amplification of conditioned responding without changing the target of approach | Increase in the subjective valuation of food cues |

DeFeliceantonio and Berridge 2012; Rihm et al., 2018 |

4. Role of the mesolimbic system in incentive motivation and sleep

4.1. Ventral tegmental area (VTA) and nucleus accumbens (NAcc)

Dopamine activity in the pathway from the VTA to the NAcc is well known to be a crucial mediator of reward and reinforcement. However, there is debate about the exact role that dopamine plays in reward; whether it encodes hedonic pleasure and euphoria, reward-prediction, or motivational salience (Berridge 2007). There is a compelling argument that dopamine specifically encodes the state of incentive motivation, much of which comes from evidence that dopamine signaling is important for sign-tracking but not goal-tracking behavior (Berridge 2007; Flagel et al. 2011; Flagel and Robinson 2017). For example, reward-paired cues elicit greater dopamine release in the NAcc in STs than GTs (Flagel et al. 2011) and STs have greater surface expression of the DA transporter in the NAcc than GTs (Singer et al. 2016b). Although disruption of activity in the NAcc-shell does not impair sign-tracking acquisition (Chang and Holland 2013; Chang et al. 2018), disruption of activity in the NAcc-core will reduce approach to the lever in STs, but not approach to the food cup in GTs (Chang et al. 2012b; Flagel et al. 2011; Fraser and Janak 2017; Saunders and Robinson 2012). Thus, it appears that cues must be attributed with incentive salience to engage dopamine-mediated reward circuitry, and that the predictive value of cues is not sufficient (Flagel et al. 2011; Yager et al. 2015).

Key structures in the mesolimbic system are also activated during sleep and play a vital role in the reprocessing and encoding of memories with high emotional or motivational content (Oishi and Lazarus 2017; Perogamvros and Schwartz 2012; Perogamvros et al. 2013). There has been some debate about the role of the VTA in sleep (Oishi and Lazarus 2017) since early electrophysiological studies found that VTA dopamine neurons did not change firing rates across sleep-wake states (Miller et al. 1983). However, in more recent studies, single unit recordings have shown that burst firing patterns in the VTA, but not mean firing rates, differ between REM sleep, NREM sleep, and wakefulness, with burst firing observed during REM sleep that is similar to activity patterns seen during the consumption of food reward (Dahan et al. 2007). Consequently, dopamine concentrations in the NAcc are higher during waking and REM sleep compared to NREM sleep (Eban-Rothschild et al. 2016; Lena et al. 2005). In addition, it is well known that stimulant drugs that increase dopamine concentrations are powerful promoters of wakefulness (Boutrel and Koob 2004). There is also recent evidence that VTA dopaminergic neurons are directly involved in promoting wakefulness in response to environmental stimuli. Optogenetic or chemogenetic activation of VTA neurons initiates and maintains wakefulness despite high homeostatic sleep pressure, and this effect is primarily mediated by projections to the NAcc (Eban-Rothschild et al. 2016; Oishi et al. 2017). Finally, there is evidence that mesolimbic dopamine activity also plays an important role in the generation of dreams (Feld et al. 2014), and it has been suggested that the dopaminergic forebrain pathway plays a larger role in dreaming than the cholinergic brain stem mechanisms that trigger REM sleep (Solms 2000). Since the same pathway from the VTA to the NAcc is critically involved in both the attribution of incentive salience to cues and the regulation of sleep-wake states, it is likely that individual differences between STs and GTs will also be expressed as differences in dopaminergic control of sleep and wakefulness.

4.2. Hippocampus (HPC)

The hippocampus is known to play a critical role in learning, as well as the consolidation of memories during sleep (Dudai 2004). Network connectivity between the NAcc and the hippocampus may also play an important role in mediating the effects of SD on reward-related behavior and motivation. The encoding of memory by the hippocampus depends on the reactivation of specific experience-related neural firing sequences during NREM sleep, and if this neuronal replay is interrupted by sleep loss it impairs the subsequent recall of spatial and contextual memories (Chen and Wilson 2017). A similar process of spontaneous replay has been observed in the ventral striatum during NREM sleep following performance of a reward-related task (Ahmed et al. 2008; Lansink et al. 2008; Pennartz et al. 2004), and this reactivation is critical for the encoding of reward-related memories, such as the spatial location of food reward (Lansink et al. 2012). Replay sequences in the NAcc can be triggered by sharp wave ripples in the hippocampus (Singer and Frank 2009) and replay in the NAcc is dominated by pairs of neurons in which hippocampal “place” cells fire immediately before the reward-related NAcc neuron (Lansink et al. 2009). Therefore, joint reactivation of hippocampal and NAcc firing patterns represents an important mechanism for consolidation of place-reward associations, and may be particularly vulnerable to disruption by SD.

Reward encoding can also take place within the hippocampus itself. Place cell firing fields accumulate near goal locations (Hollup et al. 2001), and there are dedicated populations of neurons in the HPC that specifically encode proximity to reward (Gauthier and Tank 2018). The ventral region of the HPC plays a particularly important role in reward processing. The ventral HPC sends prominent glutamatergic projections to the NAcc which are responsible for carrying spatial information to the NAcc and are critical for linking reward learning with contextual information (Britt et al. 2012; Lansink et al. 2008; Lansink et al. 2009). For example, the learning of context-drug associations selectively strengthens the connection between ventral HPC place cells and medium spiny neurons in the NAcc (Sjulson et al. 2018), and disruption of this pathway by inactivation of the ventral (but not dorsal) HPC impairs the retrieval of contextual reward memory (Riaz et al. 2017).

The ventral HPC also plays an important role in sign-tracking. One study found that lesions of the ventral HPC, but not dorsal HPC, impaired the initial learning of a sign-tracking response (Fitzpatrick et al. 2016a). In another study, STs were found to have elevated myo-inositol (a marker of glial activity and proliferation) in the ventral (but not dorsal) HPC relative to GTs (Fitzpatrick et al. 2016b). Therefore, individual differences in the HPC inputs to the NAcc could be a contributing factor in the development of ST versus GT behavioral responses. It is possible that differences in hippocampal ripple-triggered activity in the NAcc during sleep may play a critical role in how some individuals develop stronger incentive motivational associations with reward cues than others. Examination of this connection in the ST/GT model would be a critical first step in understanding the importance of the HPC in the attribution of incentive salience to cues.

4.3. Ventral pallidum (VP)

The VP has received less attention than the VTA and the NAcc, but also plays an important role in reward and reinforcement. The VP is the primary output structure for mesolimbic reward circuitry. It is heavily innervated by the GABAergic medium spiny neurons in the NAcc (Creed et al. 2016; Ho and Berridge 2013; Kupchik et al. 2015; Root et al. 2015), and projects back to the VTA and to several areas involved in the regulation of movement (Root et al. 2015; Zahm 2000). Due to these connectivity patterns, the VP is thought to be a primary hub where motivational output from the NAcc is translated into appetitive behavior (Smith et al. 2009); however, there is also evidence for bi-directional communication between the NAcc and VP, as cue responses in the VP sometimes precede and drive those in the NAcc (Chang et al. 2018; Richard et al. 2016).

The VP is a heterogeneous structure, with rostral-caudal differences in cell morphology and connectivity patterns (Kupchik and Kalivas 2013; Root et al. 2015; Zahm 2000). For example, there are topographic differences in projection patterns, with the anterior VP receiving projections from the NAcc shell and the posterior VP receiving projections from the NAcc core (Kupchik et al. 2015; Root et al. 2015). The functional differences between anterior and posterior regions are not well understood; however, some studies have found that they play different roles in modulating reward-related behavior (Root et al. 2010; Root et al. 2013), and have even been shown to have opposite effects on hedonic responses to food reward (Smith and Berridge 2007; Smith et al. 2009).

Several studies have shown that neurons in the caudal VP respond to food cues, with the magnitude of the response reflecting the strength of the cue’s motivational impact (Avila and Lin 2014a, b; Smith et al. 2011; Tachibana and Hikosaka 2012; Tindell et al. 2005; Tindell et al. 2006). The VP has also been shown to specifically encode the incentive value of a cue in a way that can be experimentally dissociated from reward prediction (Smith et al. 2011; Tindell et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2009). For example, chemogenetic inactivation of the VP can impair the acquisition (but not expression) of sign-tracking behavior, while leaving goal-tracking unaffected (Chang et al. 2015). Importantly, the VP is the only structure where differences in single-unit neural activity have been documented between STs and GTs. In two previous studies, STs have shown sustained changes in neural activity during exposure to the lever cue that are greater, in terms of proportion of responsive cells and the magnitude of responses, than that of GTs (Ahrens et al. 2016a; Ahrens et al. 2018). The heightened VP activity in STs was specifically evoked by the lever cue. When the same animals were trained with a tone cue that predicted identical reward, but did not support the attribution of incentive salience, the tone did not elicit the robust changes in neural activity that were seen with the lever. Therefore, not only does the VP reflects individual differences in motivational tendencies, it tracks dynamic changes in incentive value of cues as they change from trial to trial within a single animal (Ahrens et al. 2018). Few studies have specifically focused on the role of the VP during sleep; however, the VP has been examined as part of the larger basal forebrain region, which has been shown to play a very important role in mediating both sleep and waking states (Jones 2017; Yang et al. 2017). The basal forebrain describes a large area that encompasses the VP in addition to other subcortical structures, such as the medial septum, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, substantia innominata, magnocellular preoptic nucleus, and extended amygdala (Yang et al. 2017). The basal forebrain contains a mix of cholinergic, glutamatergic, and GABAergic cells that co-express different calciumbinding proteins. Among these cell types four different functional activity patterns have been identified. The most common type (~50%) are cortically-projecting cells that show maximal firing during waking and REM sleep, but not NREM sleep (Jones 2017), and when optogenetically stimulated produces a rapid desynchronization of EEG and an increase in wakefulness (Irmak and de Lecea 2014; Xu et al. 2015). The cholinergic neurons almost exclusively fall in this wake-promoting category (Lee et al. 2005), as do most glutamatergic neurons and some parvalbumin-positive GABAergic neurons (Hassani et al. 2009). A second type (~20%) are sleep-active, meaning they respond more during NREM sleep than during active brain states. Most these neurons are somatostatin-positive GABAergic neurons, with some glutamatergic neurons, and they project primarily to the prefrontal cortex (Hassani et al. 2009; Xu et al. 2015). The third type is relatively infrequent (~10%) and are glutamatergic neurons that respond maximally during waking. The fourth type (~20%) is maximally responsive during REM sleep, but not waking. These are a mix of GABAergic and glutamatergic cells that project primarily to the posterior hypothalamus (Jones 2017). Although basal forebrain neurons have been well characterized in the context of sleep and wakefulness, it is not known whether there are individual differences in the composition or function of these different cell types. It is also not known whether the VP itself shares all of the same characteristics as this larger basal forebrain region. Finally, further research is needed to determine what role the VP plays (if any) on the ability of sleep to alter reward seeking behavior.

4.4. Medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC)

The mPFC is a key component of the mesolimbic reward system. It is involved in the evaluation of the salience and motivational significance of reward-paired cues, and in selection and initiation of motivated actions (Moorman and Aston-Jones 2015; Moorman et al. 2015). Two important areas of the mPFC, the prelimbic and infralimbic regions, have very different projection patterns and can play different roles in reward-driven behavior. Although both are connected with several areas that are involved in motivation and emotion, such as the VTA, hippocampus, and amygdala, and paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT) (Li and Kirouac 2012; Vertes 2004), there are especially prominent projections to the NAcc. The prelimbic cortex projects primarily to the NAcc core, and the infralimbic cortex projects primarily to the NAcc shell (Vertes 2004). These pathways have been shown to have opposite effects on a range of motivated behaviors, such as cocaine self-administration (LaLumiere et al. 2010; Peters et al. 2008; Peters et al. 2009), sucrose reinforcement (Peters and De Vries 2013), and conditioned fear (Maren and Quirk 2004; Peters et al. 2009). The prelimbic cortex is important for the acquisition of excitatory conditioning (Meyer and Bucci 2014), and often acts as a “go” signal that instigates reward seeking; whereas the infralimbic cortex is important for the expression of well-learned inhibitory behavior, acting as a “stop” signal that suppresses previously learned conditioned responses (LaLumiere et al. 2010; Peters et al. 2009; Peters and De Vries 2013). However, other studies suggest that the function of the mPFC is more complex than this simple dichotomy (Moorman et al. 2015); for example, the prelimbic cortex has also been shown to inhibit dominant responses in favor of more adaptive, goal-driven behavior (Meyer and Bucci 2014).

In addition to its role in the expression of reward-seeking, the mPFC is important for the consolidation of reward-related memories during sleep. For example, the ability of sleep deprivation to enhance sucrose seeking and consumption is associated with a selective weakening of the glutamatergic pathway from the mPFC to the NAcc (Liu et al. 2016). The mPFC also has strong functional connections with the hippocampus. It receives direct projections from the ventral hippocampus CA1 (Adhikari et al. 2010; Hoover and Vertes 2007), and studies that have recorded from both the mPFC and hippocampus have found correlations between spike times in the two regions, as well as coherent theta rhythms (Adhikari et al. 2010; Benchenane et al. 2010; Colgin 2011). Furthermore, the mPFC and hippocampus reactivate together during slow-wave sleep, with synchronous bursts of activity occurring in both structures during sharp-wave ripples in the hippocampus (Colgin 2011; Wierzynski et al. 2009).

The mPFC also mediates aspects of executive function that may be particularly relevant to STs and GTs, such as impulsivity and attentional control. It has been shown that STs have low levels of cholinergic activity in the mPFC relative to GTs, and that this causes poor attentional control in STs compared to GTs (Paolone et al. 2013). At the same time, STs have greater dopamine responses to cues in the mPFC than GTs, which couple with low cholinergic activity, is thought to contribute to the reduced “top-down” control of behavior seen in STs relative to GTs (Pitchers et al. 2017). Furthermore, as mentioned above, projections from the prelimbic cortex to the PVT are thought to mediate behavioral control in GTs (Haight et al. 2017). Therefore, given that the mPFC plays such a prominent role in multiple reward-seeking paradigms, consolidation of reward memories during sleep, and individual differences in incentive salience attribution, we believe this this is an area where fundamental phenotypic differences in ST/GT neurocircuitry are very likely to be observed.

4.5. Amygdala (AMG)

The AMG is an essential part of the mesolimbic circuitry; however, there is limited information on the role the AMG plays in ST/GT behavior. It does not appear to be essential for the initial attribution of incentive salience to cues, but it may act to amplify incentive value once it has been acquired, possibly through dense glutamatergic projections from the amygdala to the NAcc (Britt et al. 2012; Stuber et al. 2011). In one study, opioid stimulation of the central nucleus of the amygdala enhanced the intensity of conditioned responses without changing the target of approach, causing STs to show stronger sign-tracking and GTs to show stronger goal-tracking (DiFeliceantonio and Berridge 2012). In another study, lesions of the basolateral amygdala reduced the rate of lever pressing in STs after extended training, and disconnection of the basolateral amygdala and the NAcc produced deficits in both the acquisition of sign-tracking and in the rate of responding in trials when sign-tracking occurred (Chang et al. 2012b). In contrast, lesions of the central nucleus of the amygdala had no effect on the acquisition or expression of sign-tracking behavior (Chang et al. 2012a).

The amygdala is also involved in the ability of sleep deprivation to enhance the motivational effects of food cues. In a recent human study, a single night of sleep deprivation increased the subjective valuation of food cues and caused a parallel increase in activity in the amygdala and hypothalamus (Rihm et al. 2018). In another study, subjects that experienced sleep debt in daily life demonstrated elevated amygdala reactivity to food cues, which was reduced after optimal sleep (Katsunuma et al. 2017). Therefore, the increased activity in the amygdala that results from suboptimal sleep may act to amplify the incentive motivation that is triggered by reward-paired cues, and contribute to the heightened reward-seeking behavior that often follows sleep deprivation.

4.6. Paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT)

The PVT is a thalamic midline structure with numerous connections to cortical, limbic, and motor structures (Kelley et al. 2005; Li and Kirouac 2012), including dense projections to the NAcc, prelimbic and infralimbic cortices, and amygdala (Vertes and Hoover 2008). Recent studies have found that the PVT may be one of the key structures mediating incentive versus predictive cue responses seen in STs and GTs. Under normal conditions the PVT appears to suppress the attribution of incentive salience to cues and plays a role in preventing GTs from expressing attraction to cues. For example, disruption of PVT activity has been shown to increase sign-tracking behavior and decrease goal-tracking behavior, causing rats previously identified as GTs to switch to sign-tracking (Haight et al. 2015). Furthermore, disruption of the PVT increases cue-induced reinstatement of drug seeking in GTs to the level normally seen in STs (Kuhn et al. 2017). A recent dual-labeling study (c-fos and flourogold) found that in both STs and GTs a food-paired cue activated the projection from the prelimbic cortex to the PVT, suggesting that this pathway mediates the predictive value of the cue, which both STs and GTs experience equally. However, in STs, the cues also activated subcortical pathways from the hypothalamus and amygdala to the PVT, as well as projections from the PVT to the ventral striatum, suggesting that these connections are involved in processing the incentive value of a cue. Therefore, the prelimbic-to-PVT pathway is hypothesized to be part of an inhibitory mechanism by which GTs exert greater cortical “top-down” control over motivated behavior and react primarily to the predictive value of a cue. The lack of this inhibition causes STs to act more on “bottom-up” emotional impulses driven by subcortical circuitry (Haight et al. 2017).

In addition to its prominent role in incentive motivation, the PVT is also ideally situated to play an important role in modulating sleep-wake states. The PVT receives synaptic inputs from, and projects back to, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which is the master clock that regulates circadian rhythms in mammals (Alamilla et al. 2015; Colavito et al. 2015; Moga et al. 1995; Peng and Bentivoglio 2004; Vertes and Hoover 2008). Through its dense projections to limbic areas, the PVT can relay information about circadian rhythms from the SCN to the NAcc, amygdala, infralimbic and prelimbic cortices (Vertes and Hoover 2008). In addition, axon terminals of SCN fibers terminate on PVT neurons projecting to the amygdala (Peng and Bentivoglio 2004). Many of these connections are reciprocal, and since the PVT projects back to the SCN it can mediate the ability of behavioral arousal and attentive states to alter circadian rhythms. For example, inputs from the PVT can shift membrane potential in SCN neurons and make them more responsive to external light cues transmitted through the retinohypothalamic tract (Alamilla et al. 2015). Therefore, the PVT is in an ideal position to relay information about circadian timing from the SCN to brain regions involved in motivation aspects of behavior, and to also provide regulatory feedback to the SCN.

4.7. Other relevant brain regions

There are other brain areas that are potentially involved in the regulation of both sleep and reward in addition to those discussed above. For example, the habenula is likely to play a role, since it has been suggested to regulate specific aspects of sleep, namely motor suppression and the generation of REM sleep (Hikosaka 2010). It is also involved in reinforcement learning, and is thought to mediate the suppression of behavior when faced with failure to receive an expected reward or the avoidance of punishment (Hikosaka 2010). The lateral habenula also plays a role in symptoms of depression and in the processing of negatively-valenced information. It is hyperactive in individuals suffering major depression and shows greater synaptic activity during learned helplessness in rats, which can be reversed with antidepressant treatment (Yang et al. 2018).

Another potential area of investigation is the locus ceruleus, which ennervates the majority of the brain and regulates norepinephrine levels. The locus ceruleus is relevant for sleep as norepinephrine is one of the major wake-promoting neurotransmitters in the brain, and is important for attention and vigilance (Hofmeister and Sterpenich 2015). It is also thought to be involved in the negative, stress-inducing effects of drug withdrawal (Belujon and Grace 2011). Therefore, although the roles of the habenula and locus ceruleus are less well characterized in the context of addicition than other mesolimbic areas, it is likely that variability in the functioning of these areas could contribute to the individual differences seen in both sleep characteristics and reward-seeking behavior.

5. Critical need for the study of individual differences in sleep-reward circuitry

There is significant overlap between the neural circuitry controlling the motivation for reward and the circuitry controlling sleep-wake states (Fig. 1). Given the many points of interaction between these systems, it is easy to see why these behavioral states are so closely intertwined, and how acute or chronic sleep disturbances can cause such profound changes in the consumption of food, drugs, and alcohol. Individual differences are a major concern for the study of both addiction and sleep disorders. There is tremendous individual variation in how these conditions develop, the effects they have on health and social functioning, and how they respond to treatment. Rodents show natural phenotypic differences in the degree to which food-paired cues engage mesolimbic dopaminergic activity and elicit incentive motivational states. These individual differences have a strong genetic component, and are associated with other behavioral traits that are frequently comorbid with addictive tendencies. By taking advantage of these individual differences, it may be possible to determine whether certain sleep patterns represent an underlying predisposing factor for addictive behavior. For example, a predisposition for poor quality or fragmented sleep, prior to any drug or reward exposure, may be one of several traits that are part of an addictive phenotype. Disordered sleep may cause certain individuals to experience greater attraction to incentive cues when they are first encountered (leading to sign-tracking), which may then be exacerbated by further cue exposure or by the sleep deficits that can result from the comsumption of drugs or alcohol. Another possibility is that baseline sleep characteristics do not differ between STs and GTs, but the hyper-responsive mesolimbic circuitry that underlies sign-tracking may render STs especially vulnerable to the negative effects of sleep deprivation on reward-seeking behavior. In either case, the ST/GT model could provide a better understanding of how the neural pathways mediating sleep and motivation interact with each other, and ultimately lead to treatment strategies for substance use disorders that are more closely tailored to the unique needs of each invidual.

Highlights.

There is individual variation in the effects of sleep loss on reward circuitry

This individual variation has been difficult to study in preclinical animal models

There exists a Sign/Goal Tracker model of individual differences in cued motivation

There is overlapping circuitry responsible for both sleep and ST/GT behavior

ST/GT model can be used to study individual variation in sleep-reward interactions

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Terry Robinson and Wayne Aldridge for helpful discussions related to these topics. This work was supported by grants to OJA from the NIH (R03MH111316), Michigan Institute for Computational Discovery & Engineering (MICDE Catalyst Grant) and the Joyce and Don Massey Family Foundation / MCIRCC.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adhikari A, Topiwala MA and Gordon JA (2010). Synchronized activity between the ventral hippocampus and the medial prefrontal cortex during anxiety. Neuron 65(2): 257–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed OJ, McFarland J and Kumar A (2008). Reactivation in ventral striatum during hippocampal ripples: evidence for the binding of reward and spatial memories? J Neurosci 28(40): 9895–9897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahrens AM, Meyer PJ, Ferguson LM, Robinson TE and Aldridge JW (2016a). Neural Activity in the Ventral Pallidum Encodes Variation in the Incentive Value of a Reward Cue. J Neurosci 36(30): 7957–7970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahrens AM, Singer BF, Fitzpatrick CJ, Morrow JD and Robinson TE (2016b). Rats that sign-track are resistant to Pavlovian but not instrumental extinction. Behav Brain Res 296: 418–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahrens AM, Ferguson LM, Robinson TE and Aldridge JW (2018). Dynamic Encoding of Incentive Salience in the Ventral Pallidum: Dependence on the Form of the Reward Cue. eNeuro 5(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alamilla J, Granados-Fuentes D and Aguilar-Roblero R (2015). The anterior paraventricular thalamus modulates neuronal excitability in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of the rat. Eur J Neurosci 42(10): 2833–2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avila I and Lin SC (2014a). Motivational salience signal in the basal forebrain is coupled with faster and more precise decision speed. PLoS Biol 12(3): e1001811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avila I and Lin SC (2014b). Distinct neuronal populations in the basal forebrain encode motivational salience and movement. Front Behav Neurosci 8: 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beckmann JS and Chow JJ (2015). Isolating the incentive salience of reward-associated stimuli: value, choice, and persistence. Learn Mem 22(2): 116–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belujon P and Grace AA (2011). Hippocampus, amygdala, and stress: interacting systems that affect susceptibility to addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1216: 114–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benchenane K, Peyrache A, Khamassi M, Tierney PL, Gioanni Y, Battaglia FP and Wiener SI (2010). Coherent theta oscillations and reorganization of spike timing in the hippocampal- prefrontal network upon learning. Neuron 66(6): 921–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berridge KC (2007). The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 191(3): 391–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boutrel B and Koob GF (2004). What keeps us awake: The neuropharmacology of stimulants and wakefulness promoting medications. Sleep 27(6): 1181–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Britt JP, Benaliouad F, McDevitt RA, Stuber GD, Wise RA and Bonci A (2012). Synaptic and behavioral profile of multiple glutamatergic inputs to the nucleus accumbens. Neuron 76(4): 790–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang SE, Wheeler DS and Holland PC (2012a). Effects of lesions of the amygdala central nucleus on autoshaped lever pressing. Brain Res 1450: 49–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang SE, Wheeler DS and Holland PC (2012b). Roles of nucleus accumbens and basolateral amygdala in autoshaped lever pressing. Neurobiol Learn Mem 97(4): 441–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang SE and Holland PC (2013). Effects of nucleus accumbens core and shell lesions on autoshaped lever-pressing. Behav Brain Res 256: 36–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang SE, Todd TP, Bucci DJ and Smith KS (2015). Chemogenetic manipulation of ventral pallidal neurons impairs acquisition of sign-tracking in rats. Eur J Neurosci 42(12): 3105–3116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang SE, Todd TP and Smith KS (2018). Paradoxical accentuation of motivation following accumbens-pallidum disconnection. Neurobiol Learn Mem 149: 39–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen B, Wang Y, Liu X, Liu Z, Dong Y and Huang YH (2015). Sleep Regulates Incubation of Cocaine Craving. J Neurosci 35(39): 13300–13310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Z and Wilson MA (2017). Deciphering Neural Codes of Memory during Sleep. Trends Neurosci 40(5): 260–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colavito V, Tesoriero C, Wirtu AT, Grassi-Zucconi G and Bentivoglio M (2015). Limbic thalamus and state-dependent behavior: The paraventricular nucleus of the thalamic midline as a node in circadian timing and sleep/wake-regulatory networks. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 54: 3–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colgin LL (2011). Oscillations and hippocampal-prefrontal synchrony. Curr Opin Neurobiol 21(3): 467–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Creed M, Ntamati NR, Chandra R, Lobo MK and Luscher C (2016). Convergence of Reinforcing and Anhedonic Cocaine Effects in the Ventral Pallidum. Neuron 92(1): 214–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahan L, Astier B, Vautrelle N, Urbain N, Kocsis B and Chouvet G (2007). Prominent burst firing of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area during paradoxical sleep. Neuropsychopharmacology 32(6): 1232–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dalley JW, Fryer TD, Brichard L, Robinson ES, Theobald DE, Laane K, Pena Y, Murphy ER, Shah Y, Probst K, Abakumova I, Aigbirhio FI, Richards HK, Hong Y, Baron JC, Everitt BJ and Robbins TW (2007). Nucleus accumbens D2/3 receptors predict trait impulsivity and cocaine reinforcement. Science 315(5816): 1267–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeAngeli NE, Miller SB, Meyer HC and Bucci DJ (2017). Increased sign-tracking behavior in adolescent rats. Dev Psychobiol 59(7): 840–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DePoy LM, McClung CA and Logan RW (2017). Neural Mechanisms of Circadian Regulation of Natural and Drug Reward. Neural Plast 2017: 5720842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dickson PE, McNaughton KA, Hou L, Anderson LC, Long KH and Chesler EJ (2015). Sex and strain influence attribution of incentive salience to reward cues in mice. Behav Brain Res 292: 305–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DiFeliceantonio AG and Berridge KC (2012). Which cue to ‘want’? Opioid stimulation of central amygdala makes goal-trackers show stronger goal-tracking, just as sign-trackers show stronger sign-tracking. Behav Brain Res 230(2): 399–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dong L, Bilbao A, Laucht M, Henriksson R, Yakovleva T, Ridinger M, Desrivieres S, Clarke TK, Lourdusamy A, Smolka MN, Cichon S, Blomeyer D, Treutlein J, Perreau-Lenz S, Witt S, Leonardi-Essmann F, Wodarz N, Zill P, Soyka M, Albrecht U, Rietschel M, Lathrop M, Bakalkin G, Spanagel R and Schumann G (2011). Effects of the circadian rhythm gene period 1 (per1) on psychosocial stress-induced alcohol drinking. Am J Psychiatry 168(10): 1090–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dudai Y (2004). The neurobiology of consolidations, or, how stable is the engram? Annu Rev Psychol 55: 51–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eban-Rothschild A, Rothschild G, Giardino WJ, Jones JR and de Lecea L (2016). VTA dopaminergic neurons regulate ethologically relevant sleep-wake behaviors. Nat Neurosci 19(10): 1356–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feld GB, Besedovsky L, Kaida K, Munte TF and Born J (2014). Dopamine D2-like receptor activation wipes out preferential consolidation of high over low reward memories during human sleep. J Cogn Neurosci 26(10): 2310–2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fitzpatrick CJ, Gopalakrishnan S, Cogan ES, Yager LM, Meyer PJ, Lovic V, Saunders BT, Parker CC, Gonzales NM, Aryee E, Flagel SB, Palmer AA, Robinson TE and Morrow JD (2013). Variation in the form of Pavlovian conditioned approach behavior among outbred male Sprague-Dawley rats from different vendors and colonies: sign-tracking vs. goal-tracking. PLoS One 8(10): e75042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fitzpatrick CJ, Creeden JF, Perrine SA and Morrow JD (2016a). Lesions of the ventral hippocampus attenuate the acquisition but not expression of sign-tracking behavior in rats. Hippocampus 26(11): 1424–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fitzpatrick CJ, Perrine SA, Ghoddoussi F, Galloway MP and Morrow JD (2016b). Sign-trackers have elevated myo-inositol in the nucleus accumbens and ventral hippocampus following Pavlovian conditioned approach. J Neurochem 136(6): 1196–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flagel SB, Akil H and Robinson TE (2009). Individual differences in the attribution of incentive salience to reward-related cues: Implications for addiction. Neuropharmacology 56 Suppl 1: 139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flagel SB, Robinson TE, Clark JJ, Clinton SM, Watson SJ, Seeman P, Phillips PE and Akil H (2010). An animal model of genetic vulnerability to behavioral disinhibition and responsiveness to reward-related cues: implications for addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 35(2): 388–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flagel SB, Clark JJ, Robinson TE, Mayo L, Czuj A, Willuhn I, Akers CA, Clinton SM, Phillips PE and Akil H (2011). A selective role for dopamine in stimulus-reward learning. Nature 469(7328): 53–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flagel SB and Robinson TE (2017). Neurobiological Basis of Individual Variation in Stimulus-Reward Learning. Curr Opin Behav Sci 13: 178–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fraser KM and Janak PH (2017). Long-lasting contribution of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens core, but not dorsal lateral striatum, to sign-tracking. Eur J Neurosci 46(4): 2047–2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gauthier JL and Tank DW (2018). A Dedicated Population for Reward Coding in the Hippocampus. Neuron 99(1): 179–193 e177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gillman AG, Rebec GV, Pecoraro NC and Kosobud AEK (2019). Circadian entrainment by food and drugs of abuse. Behav Processes 165: 23–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greer SM, Goldstein AN, Knutson B and Walker MP (2016). A Genetic Polymorphism of the Human Dopamine Transporter Determines the Impact of Sleep Deprivation on Brain Responses to Rewards and Punishments. J Cogn Neurosci 28(6): 803–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hagewoud R, Havekes R, Novati A, Keijser JN, Van der Zee EA and Meerlo P (2010a). Sleep deprivation impairs spatial working memory and reduces hippocampal AMPA receptor phosphorylation. J Sleep Res 19(2): 280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hagewoud R, Havekes R, Tiba PA, Novati A, Hogenelst K, Weinreder P, Van der Zee EA and Meerlo P (2010b). Coping with sleep deprivation: shifts in regional brain activity and learning strategy. Sleep 33(11): 1465–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haight JL, Fraser KM, Akil H and Flagel SB (2015). Lesions of the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus differentially affect sign- and goal-tracking conditioned responses. Eur J Neurosci 42(7): 2478–2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haight JL, Fuller ZL, Fraser KM and Flagel SB (2017). A food-predictive cue attributed with incentive salience engages subcortical afferents and efferents of the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus. Neuroscience 340: 135–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hasler BP, Smith LJ, Cousins JC and Bootzin RR (2012). Circadian rhythms, sleep, and substance abuse. Sleep Med Rev 16(1): 67–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hassani OK, Lee MG, Henny P and Jones BE (2009). Discharge profiles of identified GABAergic in comparison to cholinergic and putative glutamatergic basal forebrain neurons across the sleep-wake cycle. J Neurosci 29(38): 11828–11840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hikosaka O (2010). The habenula: from stress evasion to value-based decision-making. Nat Rev Neurosci 11(7): 503–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ho CY and Berridge KC (2013). An orexin hotspot in ventral pallidum amplifies hedonic ‘liking’ for sweetness. Neuropsychopharmacology 38(9): 1655–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hofmeister J and Sterpenich V (2015). A Role for the Locus Ceruleus in Reward Processing: Encoding Behavioral Energy Required for Goal-Directed Actions. J Neurosci 35(29): 10387–10389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hollup SA, Molden S, Donnett JG, Moser MB and Moser EI (2001). Accumulation of hippocampal place fields at the goal location in an annular watermaze task. Journal of Neuroscience 21(5): 1635–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoover WB and Vertes RP (2007). Anatomical analysis of afferent projections to the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat. Brain Struct Funct 212(2): 149–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hughson AR, Horvath AP, Holl K, Palmer AA, Solberg Woods LC, Robinson TE and Flagel SB (2019). Incentive salience attribution, “sensation-seeking” and “novelty-seeking” are independent traits in a large sample of male and female heterogeneous stock rats. Sci Rep 9(1): 2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Irmak SO and de Lecea L (2014). Basal forebrain cholinergic modulation of sleep transitions. Sleep 37(12): 1941–1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jones BE (2017). Principal cell types of sleep-wake regulatory circuits. Curr Opin Neurobiol 44: 101–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kameda SR, Fukushiro DF, Trombin TF, Sanday L, Wuo-Silva R, Saito LP, Tufik S, D’Almeida V and Frussa-Filho R (2014). The effects of paradoxical sleep deprivation on amphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization in adult and adolescent mice. Psychiatry Res 218(3): 335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kamphuis J, Baichel S, Lancel M, de Boer SF, Koolhaas JM and Meerlo P (2017). Sleep restriction in rats leads to changes in operant behaviour indicative of reduced prefrontal cortex function. J Sleep Res 26(1): 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karimi-Haghighi S and Haghparast A (2018). Cannabidiol inhibits priming-induced reinstatement of methamphetamine in REM sleep deprived rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 82: 307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Katsunuma R, Oba K, Kitamura S, Motomura Y, Terasawa Y, Nakazaki K, Hida A, Moriguchi Y and Mishima K (2017). Unrecognized Sleep Loss Accumulated in Daily Life Can Promote Brain Hyperreactivity to Food Cue. Sleep 40(10). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kelley AE, Baldo BA, Pratt WE and Will MJ (2005). Corticostriatal-hypothalamic circuitry and food motivation: integration of energy, action and reward. Physiol Behav 86(5): 773–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.King CP, Palmer AA, Woods LC, Hawk LW, Richards JB and Meyer PJ (2016). Premature responding is associated with approach to a food cue in male and female heterogeneous stock rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 233(13): 2593–2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Knapp CM, Datta S, Ciraulo DA and Kornetsky C (2007). Effects of low dose cocaine on REM sleep in the freely moving rat. Sleep Biol Rhythms 5(1): 55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Knapp CM, Ciraulo DA and Datta S (2014). Mechanisms underlying sleep-wake disturbances in alcoholism: focus on the cholinergic pedunculopontine tegmentum. Behav Brain Res 274: 291–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koshy Cherian A, Kucinski A, Pitchers K, Yegla B, Parikh V, Kim Y, Valuskova P, Gurnani S, Lindsley CW, Blakely RD and Sarter M (2017). Unresponsive Choline Transporter as a Trait Neuromarker and a Causal Mediator of Bottom-Up Attentional Biases. J Neurosci 37(11): 2947–2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kovanen L, Saarikoski ST, Haukka J, Pirkola S, Aromaa A, Lonnqvist J and Partonen T (2010). Circadian clock gene polymorphisms in alcohol use disorders and alcohol consumption. Alcohol Alcohol 45(4): 303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kreutzmann JC, Havekes R, Abel T and Meerlo P (2015). Sleep deprivation and hippocampal vulnerability: changes in neuronal plasticity, neurogenesis and cognitive function. Neuroscience 309: 173–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kuhn BN, Klumpner MS, Covelo IR, Campus P and Flagel SB (2017). Transient inactivation of the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus enhances cue-induced reinstatement in goal-trackers, but not sign-trackers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kupchik YM and Kalivas PW (2013). The rostral subcommissural ventral pallidum is a mix of ventral pallidal neurons and neurons from adjacent areas: an electrophysiological study. Brain Struct Funct 218(6): 1487–1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kupchik YM, Brown RM, Heinsbroek JA, Lobo MK, Schwartz DJ and Kalivas PW (2015). Coding the direct/indirect pathways by D1 and D2 receptors is not valid for accumbens projections. Nat Neurosci 18(9): 1230–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.LaLumiere RT, Niehoff KE and Kalivas PW (2010). The infralimbic cortex regulates the consolidation of extinction after cocaine self-administration. Learn Mem 17(4): 168–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lansink CS, Goltstein PM, Lankelma JV, Joosten RN, McNaughton BL and Pennartz CM (2008). Preferential reactivation of motivationally relevant information in the ventral striatum. J Neurosci 28(25): 6372–6382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lansink CS, Goltstein PM, Lankelma JV, McNaughton BL and Pennartz CM (2009). Hippocampus leads ventral striatum in replay of place-reward information. PLoS Biol 7(8): e1000173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lansink CS, Jackson JC, Lankelma JV, Ito R, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ and Pennartz CM (2012). Reward cues in space: commonalities and differences in neural coding by hippocampal and ventral striatal ensembles. J Neurosci 32(36): 12444–12459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee MG, Hassani OK, Alonso A and Jones BE (2005). Cholinergic basal forebrain neurons burst with theta during waking and paradoxical sleep. J Neurosci 25(17): 4365–4369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lena I, Parrot S, Deschaux O, Muffat-Joly S, Sauvinet V, Renaud B, Suaud-Chagny MF and Gottesmann C (2005). Variations in extracellular levels of dopamine, noradrenaline, glutamate, and aspartate across the sleep--wake cycle in the medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats. J Neurosci Res 81(6): 891–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li S and Kirouac GJ (2012). Sources of inputs to the anterior and posterior aspects of the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus. Brain Struct Funct 217(2): 257–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Linnet J, Moller A, Peterson E, Gjedde A and Doudet D (2011). Dopamine release in ventral striatum during Iowa Gambling Task performance is associated with increased excitement levels in pathological gambling. Addiction 106(2): 383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu Z, Wang Y, Cai L, Li Y, Chen B, Dong Y and Huang YH (2016). Prefrontal Cortex to Accumbens Projections in Sleep Regulation of Reward. J Neurosci 36(30): 7897–7910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lomanowska AM, Lovic V, Rankine MJ, Mooney SJ, Robinson TE and Kraemer GW (2011). Inadequate early social experience increases the incentive salience of reward-related cues in adulthood. Behav Brain Res 220(1): 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lovic V, Saunders BT, Yager LM and Robinson TE (2011). Rats prone to attribute incentive salience to reward cues are also prone to impulsive action. Behav Brain Res 223(2): 255–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maren S and Quirk GJ (2004). Neuronal signalling of fear memory. Nat Rev Neurosci 5(11): 844–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Marmorstein NR (2017). Sleep patterns and problems among early adolescents: Associations with alcohol use. Addict Behav 66: 13–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McClung CA, Sidiropoulou K, Vitaterna M, Takahashi JS, White FJ, Cooper DC and Nestler EJ (2005). Regulation of dopaminergic transmission and cocaine reward by the Clock gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102(26): 9377–9381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McDermott CM, LaHoste GJ, Chen C, Musto A, Bazan NG and Magee JC (2003). Sleep deprivation causes behavioral, synaptic, and membrane excitability alterations in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci 23(29): 9687–9695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McEown K, Takata Y, Cherasse Y, Nagata N, Aritake K and Lazarus M (2016). Chemogenetic inhibition of the medial prefrontal cortex reverses the effects of REM sleep loss on sucrose consumption. Elife 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mendoza J (2019). Food intake and addictive-like eating behaviors: Time to think about the circadian clock(s). Neurosci Biobehav Rev 106: 122–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Meyer HC and Bucci DJ (2014). The contribution of medial prefrontal cortical regions to conditioned inhibition. Behav Neurosci 128(6): 644–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Meyer PJ, Lovic V, Saunders BT, Yager LM, Flagel SB, Morrow JD and Robinson TE (2012). Quantifying individual variation in the propensity to attribute incentive salience to reward cues. PLoS One 7(6): e38987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Miller JD, Farber J, Gatz P, Roffwarg H and German DC (1983). Activity of Mesencephalic Dopamine and Non-Dopamine Neurons across Stages of Sleep and Waking in the Rat. Brain Research 273(1): 133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moga MM, Weis RP and Moore RY (1995). Efferent projections of the paraventricular thalamic nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol 359(2): 221–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Moorman DE and Aston-Jones G (2015). Prefrontal neurons encode context-based response execution and inhibition in reward seeking and extinction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112(30): 9472–9477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Moorman DE, James MH, McGlinchey EM and Aston-Jones G (2015). Differential roles of medial prefrontal subregions in the regulation of drug seeking. Brain Res 1628(Pt A): 130–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Morrow JD, Maren S and Robinson TE (2011). Individual variation in the propensity to attribute incentive salience to an appetitive cue predicts the propensity to attribute motivational salience to an aversive cue. Behav Brain Res 220(1): 238–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Morrow JD, Saunders BT, Maren S and Robinson TE (2015). Sign-tracking to an appetitive cue predicts incubation of conditioned fear in rats. Behav Brain Res 276: 59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Oishi Y and Lazarus M (2017). The control of sleep and wakefulness by mesolimbic dopamine systems. Neurosci Res 118: 66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Oishi Y, Xu Q, Wang L, Zhang BJ, Takahashi K, Takata Y, Luo YJ, Cherasse Y, Schiffmann SN, de Kerchove d’Exaerde A, Urade Y, Qu WM, Huang ZL and Lazarus M (2017). Slow-wave sleep is controlled by a subset of nucleus accumbens core neurons in mice. Nat Commun 8(1): 734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ozburn AR, Larson EB, Self DW and McClung CA (2012). Cocaine self-administration behaviors in ClockDelta19 mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 223(2): 169–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Paolone G, Angelakos CC, Meyer PJ, Robinson TE and Sarter M (2013). Cholinergic control over attention in rats prone to attribute incentive salience to reward cues. J Neurosci 33(19): 8321–8335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Partonen T (2015). Clock genes in human alcohol abuse and comorbid conditions. Alcohol 49(4): 359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Peng ZC and Bentivoglio M (2004). The thalamic paraventricular nucleus relays information from the suprachiasmatic nucleus to the amygdala: A combined anterograde and retrograde tracing study in the rat at the light and electron microscopic levels. Journal of Neurocytology 33(1): 101–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pennartz CM, Lee E, Verheul J, Lipa P, Barnes CA and McNaughton BL (2004). The ventral striatum in off-line processing: ensemble reactivation during sleep and modulation by hippocampal ripples. J Neurosci 24(29): 6446–6456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Perogamvros L and Schwartz S (2012). The roles of the reward system in sleep and dreaming. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 36(8): 1934–1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Perogamvros L, Dang-Vu TT, Desseilles M and Schwartz S (2013). Sleep and dreaming are for important matters. Front Psychol 4: 474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Peters J, LaLumiere RT and Kalivas PW (2008). Infralimbic prefrontal cortex is responsible for inhibiting cocaine seeking in extinguished rats. J Neurosci 28(23): 6046–6053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Peters J, Kalivas PW and Quirk GJ (2009). Extinction circuits for fear and addiction overlap in prefrontal cortex. Learn Mem 16(5): 279–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Peters J and De Vries TJ (2013). D-cycloserine administered directly to infralimbic medial prefrontal cortex enhances extinction memory in sucrose-seeking animals. Neuroscience 230: 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pilcher JJ, Morris DM, Donnelly J and Feigl HB (2015). Interactions between sleep habits and self-control. Front Hum Neurosci 9: 284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pitchers KK, Kane LF, Kim Y, Robinson TE and Sarter M (2017). ‘Hot’ vs. ‘cold’ behavioural-cognitive styles: motivational-dopaminergic vs. cognitive-cholinergic processing of a Pavlovian cocaine cue in sign- and goal-tracking rats. Eur J Neurosci 46(11): 2768–2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Puhl MD, Boisvert M, Guan Z, Fang J and Grigson PS (2013). A novel model of chronic sleep restriction reveals an increase in the perceived incentive reward value of cocaine in high drug-taking rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 109: 8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Riaz S, Schumacher A, Sivagurunathan S, Van Der Meer M and Ito R (2017). Ventral, but not dorsal, hippocampus inactivation impairs reward memory expression and retrieval in contexts defined by proximal cues. Hippocampus 27(7): 822–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Richard JM, Ambroggi F, Janak PH and Fields HL (2016). Ventral Pallidum Neurons Encode Incentive Value and Promote Cue-Elicited Instrumental Actions. Neuron 90(6): 1165–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rihm JS, Menz MM, Schultz H, Bruder L, Schilbach L, Schmid SM and Peters J (2018). Sleep deprivation selectively up-regulates an amygdala-hypothalamic circuit involved in food reward. J Neurosci. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Robinson TE and Flagel SB (2009). Dissociating the predictive and incentive motivational properties of reward-related cues through the study of individual differences. Biol Psychiatry 65(10): 869–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Robinson TE, Yager LM, Cogan ES and Saunders BT (2014). On the motivational properties of reward cues: Individual differences. Neuropharmacology 76 Pt B: 450–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Root DH, Fabbricatore AT, Ma S, Barker DJ and West MO (2010). Rapid phasic activity of ventral pallidal neurons during cocaine self-administration. Synapse 64(9): 704–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Root DH, Ma S, Barker DJ, Megehee L, Striano BM, Ralston CM, Fabbricatore AT and West MO (2013). Differential roles of ventral pallidum subregions during cocaine self-administration behaviors. J Comp Neurol 521(3): 558–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Root DH, Melendez RI, Zaborszky L and Napier TC (2015). The ventral pallidum: Subregion-specific functional anatomy and roles in motivated behaviors. Prog Neurobiol 130: 29–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Rosenwasser AM, Fecteau ME, Logan RW, Reed JD, Cotter SJ and Seggio JA (2005). Circadian activity rhythms in selectively bred ethanol-preferring and nonpreferring rats. Alcohol 36(2): 69–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Rosenwasser AM (2009). Functional neuroanatomy of sleep and circadian rhythms. Brain Res Rev 61(2): 281–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Satterfield BC, Raikes AC and Killgore WDS (2018). Rested-Baseline Responsivity of the Ventral Striatum Is Associated With Caloric and Macronutrient Intake During One Night of Sleep Deprivation. Front Psychiatry 9: 749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]