Abstract

Background

The reactogenicity and immunogenicity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines are well studied. Little is known regarding the relationship between immunogenicity and reactogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines.

Methods

This study assessed the association between immunogenicity and reactogenicity after 2 mRNA-1273 (100 µg) injections in 1671 total adolescent and adult participants (≥12 years) from the primary immunogenicity sets of the blinded periods of the Coronavirus Efficacy (COVE) and TeenCOVE trials. Associations between immunogenicity through day 57 and solicited adverse reactions (ARs) after the first and second injections of mRNA-1273 were evaluated among participants with and without solicited ARs using linear mixed-effects models.

Results

mRNA-1273 reactogenicity in this combined analysis set was similar to that reported for these trials. The vaccine elicited high neutralizing antibody (nAb) geometric mean titers (GMTs) in evaluable participants. GMTs at day 57 were significantly higher in participants who experienced solicited systemic ARs after the second injection (1227.2 [1164.4–1293.5]) than those who did not (980.1 [886.8–1083.2], P = .001) and were associated with fever, chills, headache, fatigue, myalgia, and arthralgia. Significant associations with local ARs were not found.

Conclusions

These data show an association of systemic ARs with increased nAb titers following a second mRNA-1273 injection. While these data indicate systemic ARs are associated with increased antibody titers, high nAb titers were observed in participants after both injections, consistent with the immunogenicity and efficacy in these trials. These results add to the body of evidence regarding the relationship of immunogenicity and reactogenicity and can contribute toward the design of future mRNA vaccines.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, mRNA-1273, immunogenicity, reactogenicity, solicited adverse reactions

The association between immunogenicity and reactogenicity following 2 injections of mRNA-1273 vaccine was assessed in adolescents and adults (≥12 years). mRNA-1273 elicited high neutralizing antibody titers regardless of reactogenicity. Systemic reactogenicity was significantly related to higher antibody titers post–second injection.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines have demonstrated high efficacy and safety in preventing severe illness and death [1, 2]. The mRNA-1273 (Moderna COVID-19 vaccine) has received full approval in adults (≥18 years) and authorization for use in children and adolescents (6 months–17 years) in the United States and among other countries [3]. In clinical trials, the mRNA-1273 vaccine induced robust neutralizing immune responses that were generally consistent across age groups, an immune marker for vaccine efficacy [4]. Additionally, mRNA-1273 vaccination elicits varying degrees of neutralization against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variants and enhanced immune responses following booster doses [5–10].

Understanding the relationship between vaccine-induced immunogenicity and reactogenicity can aid in the development of vaccines that provide effective adaptive immune responses with reduced frequency and severity of reactogenic symptoms [11, 12]. Antigens delivered by vaccination induce pathogen-associated pathways of inflammation, which, in turn, can result in localized and systemic adverse reactions (ARs) [11, 13]. Vaccine-induced immune responses and ARs can vary due to host-derived intrinsic factors (eg, age, gender, race/ethnicity, overall health), pre-existing immunity, and extrinsic properties of vaccine composition and administration, as well as individual vaccine-perceived expectations [11].

Similar to vaccines for other viral infections [11, 14], COVID-19 vaccines induce mild-to-moderate local and systemic ARs with increased systemic ARs following a second injection [1, 2, 15]. The currently licensed mRNA vaccines have been designed to mitigate interactions with the innate immune system, leading to increased protein expression and stability, including improved immunogenicity and lower reactogenicity [16–18]. A common question regarding COVID-19 vaccination is whether ARs are predictive of immune response [11]. While the overall safety and immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines are well studied, knowledge about the relationship between solicited ARs and immunogenicity is more limited [19–22]. In this study, the association between immunogenicity and reactogenicity after the first and second injections of 100-µg mRNA-1273 was assessed in participants combined from the pivotal Coronavirus Efficacy (COVE) and TeenCOVE trials [1, 23].

METHODS

Study Design

This study included participants from the prespecified, randomly selected, primary immunogenicity sets from the blinded periods of the phase 3 COVE (adults ≥18 years; NCT04470427) and phase 2/3 TeenCOVE (adolescents 12–17 years; NCT04649151) efficacy trials who received a 2-injection schedule of 100-µg mRNA-1273 vaccine [1, 4, 23]. As the assessment methods of solicited ARs, associated toxicities, and immunogenicity were prespecified and identical in the 2 trials, the data from the studies were combined for this analysis. The associations between immunogenicity through day 57 and solicited ARs (any, local, systemic) after the first and second injections of mRNA-1273 were evaluated among participants with and without solicited ARs.

The trials were conducted in accordance with the International Council for Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, Good Clinical Practice Guidance, and applicable government regulations. The central Institutional Review Board/Ethics Commit is, Advarra, Inc., 6100 Merriweather Drive, Columbia, MD 21044. All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants, Randomization, and Masking

Details of the COVE and TeenCOVE study methods and inclusion and exclusion criteria were described and are provided in the online protocols and the Supplementary Material [1, 4, 23]. Eligible participants were vaccine recipients who met inclusion criteria for the primary immunogenicity sets of both trials.

Participants were randomized to receive mRNA-1273 100 µg or placebo in the COVE (1:1) and TeenCOVE (2:1) trials. mRNA-1273 vaccine was administered intramuscularly as 2 injections, 28 days apart, in 0.5 mL containing 100 µg of mRNA-1273 or saline placebo.

Reactogenicity Assessment

Reactogenicity was assessed by the occurrence and severity of solicited local and systemic ARs reported 7 days or fewer after each injection (Supplementary Material) [1, 23]. The severity of solicited ARs according to grading scales (1–4) 7 days or fewer after each injection is presented [24]. Solicited AR data were periodically reviewed by the unblinded data and safety monitoring board.

Immunogenicity Assessment

Immunogenicity after the first and second injections of mRNA-1273 vaccine was assessed in samples from the blinded periods of the COVE trial at days 1 (pre-injection 1), 29 (28 days post-injection 1, pre-injection 2), and 57 (57 days post-injection 1, 28 days post-injection 2) and the TeenCOVE trial at days 1 (pre-injection 1) and 57 (57 days post-injection 1). A validated SARS-CoV-2-spike (S) protein pseudotyped virus neutralization antibody (nAb) assay (Wuhan-Hu-1 D614G; Duke University, Durham, NC) was used to quantify geometric mean (GM) titers (GMTs) at inhibitory dilutions of 50% (ID50) and 80% (ID80). Serum binding antibody (bAb) GM levels were evaluated in the same samples from the COVE trial using an electrochemiluminescent immune assay specific for SARS-CoV-2-S protein (Meso-Scale Discovery [MSD] multiplex assay; NIH Vaccine Research Center, Rockville, MD). Immunogenicity assessment and assay details are described in the Supplementary Material.

Statistical Analysis

The primary analysis population consisted of the per-protocol immunogenicity analysis sets of the COVE and TeenCOVE trials and included participants without evidence of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection at baseline, who received 2 injections of mRNA-1273 100 µg, and had SARS-CoV-2 serology values at baseline and at 1 or more post–baseline visit, without major protocol deviations. Linear mixed-effects models for within-participant repeated measures with log-transformed antibody levels as the dependent variable, group variable (with/without solicited ARs), follow-up time, and interaction between group and follow-up time as fixed effects, adjusted for baseline characteristics (age group, gender, race/ethnicity group, risk factor for severe COVID-19), were used to evaluate the associations between solicited ARs and the immunogenicity outcomes through day 57 as described in the Supplementary Material. Bonferroni adjustment was used to control an overall significance level of 0.05 for multiplicity. The resulting least-squares means, difference of the means, and 95% confidence interval (CI) back-transformed to the original scale are presented. Immunogenicity data at or after the time points of a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection were excluded from the analysis. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses for varying individual and composite reactogenicity events including penalized linear mixed-effects models were performed. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

Trial Population

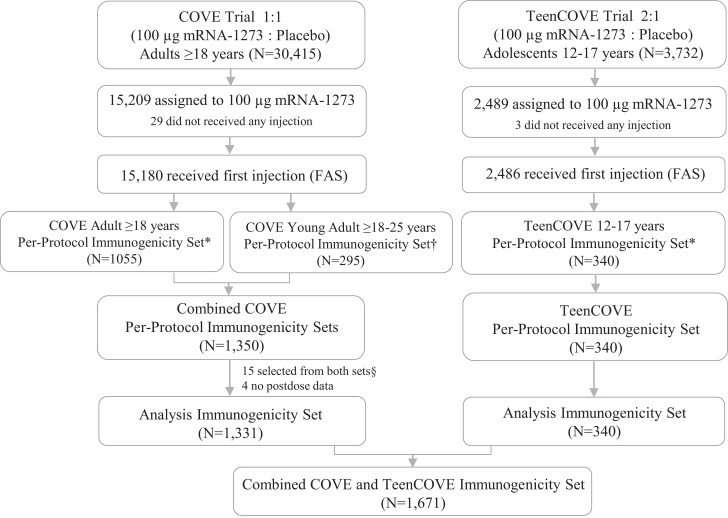

The associations of immunogenicity and reactogenicity were assessed in a combined immunogenicity analysis set of 1671 participants from the COVE (n = 1331) and TeenCOVE (n = 340) trials who received 2 injections of mRNA-1273 100 µg [1, 23]. Eligible participants for the analysis included 1051 and 280 participants from the original (n = 1055) and young-adult (n = 295) COVE trial in the analysis, respectively (Figure 1). The median time to follow-up post–first injection during the blinded periods in these analysis populations was 6.8 months (interquartile range [IQR]: 5.8–7.3 months).

Figure 1.

Trial profile immunogenicity analysis population. *The per-protocol immunogenicity subset consisted of randomly selected participants in the full analysis set (FAS) who received both planned injections (ie, received assigned treatment) with injection 2 received within 21–42 days after injection 1, had no virologic or serological evidence of SARS-CoV-2 at baseline, and had no major protocol deviations that impacted critical or key data. †Young adults from the COVE trial randomly selected for immunogenicity comparison in the TeenCOVE trial. §Fifteen samples from 18–25-year old participants selected from both immunogenicity sets. Abbreviations: COVE, Coronavirus Efficacy trial in adults; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TeenCOVE, phase 2/3 trial in adolescents.

The overall baseline characteristics of the combined immunogenicity sets were representative of the study populations in the main trials (Table 1) [1, 23]. The median age was 40 years (IQR: 21–62 years; 20.4% were 12–17 years, 58.5% were 18–64 years, and 21.1% were ≥65 years) and 52% of participants were male. Racial and ethnic representations were consistent with US demographics.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Participants at Baseline

| Characteristics | mRNA-1273 100 µg, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age, y (IQR) | 40 (21–62) |

| Age categories | |

| ȃ12–17 y | 340 (20.4) |

| ȃ18–25 y | 322 (19.3) |

| ȃ26–64 y | 656 (39.2) |

| ȃ65+ y | 353 (21.1) |

| Gender | |

| ȃMale | 872 (52.2) |

| ȃFemale | 799 (47.8) |

| Race | |

| ȃWhite | 1245 (74.5) |

| ȃBlack or African-American | 216 (12.9) |

| ȃOthersa | 210 (12.6) |

| Ethnicity | |

| ȃHispanic or Latinx | 431 (25.8) |

| ȃNon-Hispanic and others | 1240 (74.2) |

| Race and ethnicity group | |

| ȃWhite and non-Hispanic | 896 (53.6) |

| ȃCommunities of color | 775 (46.4) |

| Body mass indexb | |

| ȃ<30 kg/m2 | 1083 (64.9) |

| ȃ≥30 kg/m2 | 586 (35.1) |

| Risk for severe COVID-19c | |

| ȃYes | 432 (25.8) |

| ȃNo | 1239 (74.2) |

| Clinical study | |

| ȃCOVE | 1331 (79.7) |

| ȃTeenCOVE | 340 (20.3) |

N = 1671. Abbreviations: COVE, Coronavirus Efficacy trial in adults; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IQR, interquartile range; TeenCOVE, phase 2/3 trial in adolescents.

The “Others” category includes Asian (4.3%), American Indian or Alaska Native (1.2%), Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander (0.4%), multiple races (2.9%), other races (2.5%), and unknown (1.4%).

Two participants had missing baseline weight and height data.

Risk for severe COVID-19 includes chronic lung disease, significant cardiac disease, severe obesity, diabetes, and liver disease. This risk factor was applicable in the adult participants and no risk was determined for all adolescent participants. Among 1331 adult participants, the risk for severe COVID-19 (432 [32.5%]) included those with chronic lung disease (92 [6.9%]), significant cardiac disease (79 [5.9%]), severe obesity (140 [10.5%]), diabetes (184 [13.8%]), and liver disease (18 [1.4%]).

Reactogenicity

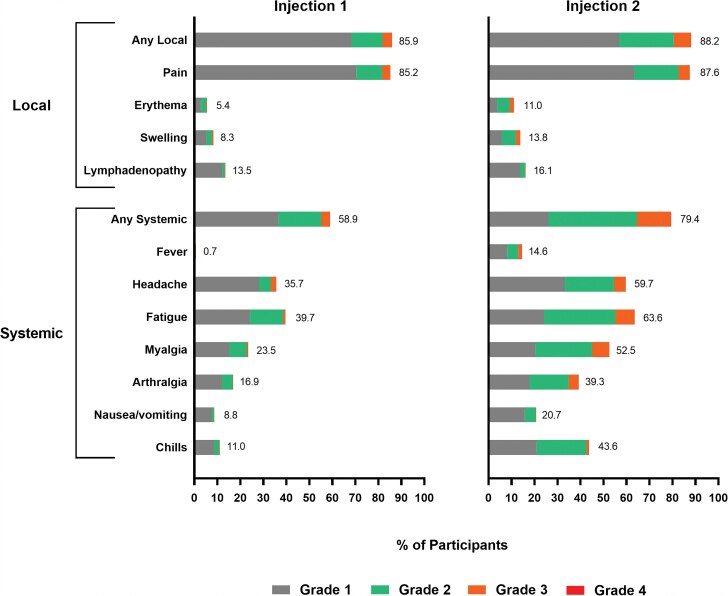

The occurrences of solicited local ARs were similar after both injections, and systemic ARs were higher after the second than the first injection (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1). The majority of solicited ARs after both injections were mild or moderate lasting 2–3 days, and the persistence of ARs beyond 7 days was similar after each injection. The frequencies of severe (grade 3) solicited ARs were greater after the second injection. The most common local ARs were pain following both injections and erythema, swelling, and axillary swelling or tenderness after the second injection. The most frequent systemic ARs were headache, fatigue, myalgia, and arthralgia after both injections, with chills and fever more common after the second than after the first injection. Grade 4 fevers (>40.0°C/104.0°F) occurred in 1 and 3 participants after the first and second injections in the adult study, respectively, while no grade 4 events occurred in the adolescent study. No adverse events considered by the investigator to be vaccine-related leading to study discontinuation occurred during the blinded periods of the 2 trials.

Figure 2.

Solicited adverse reactions after first and second injections of mRNA-1273 vaccine. Percentages of participants in the immunogenicity subset (N = 1671) who had a solicited local or systemic reaction, within 7 days following injections 1 and 2 of mRNA-1273 100 µg, are shown. The maximum toxicity grade (grade 1 [mild], grade 2 [moderate], grade 3 [severe], and grade 4) is presented. Grade 4 fevers (>40.0°C/104.0°F) occurred in 1 and 3 participants after the first and second injections in the adult study, respectively, while no grade 4 events occurred in the adolescent study.

Associations Between Immunogenicity and Adverse Reactions

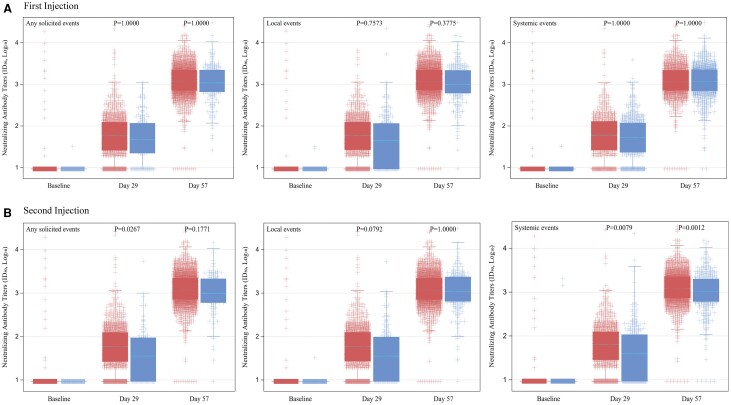

The associations of solicited ARs that occurred after the first and second injections with immunogenicity outcomes at days 1, 29, and 57 were assessed using linear mixed-effects models. The baseline GMTs (95% CI) of nAb ID50 were similar between participants with and without any solicited ARs after the first (9.5 [9.3–9.7] vs 9.3 [8.8–9.9]) and second (9.5 [9.3–9.7] vs 9.3 [8.6–9.9]) injections. Postbaseline GMTs were higher in participants who experienced solicited ARs compared with those without after both injections (Figure 3). Significantly higher day 29 GMTs were found in participants who experienced solicited ARs after the second injection compared with those without (geometric mean ratio [GMR]: 1.47 [1.02–2.12]; P = .027). Significantly higher day 29 and 57 GMTs were not observed in participants who reported solicited ARs after the first injection and local ARs after each injection compared with those without. Significantly higher day 29 (GMR: 1.33 [1.04–1.69]; P = .008) and day 57 (GMR: 1.25 [1.06–1.48]; P = .001) GMTs were observed in participants with systemic ARs after the second injection than those without systemic ARs (Tables 2 and 3, Figure 3). The GMTs were also significantly higher in the younger population and were not different by gender, race, and ethnicity groups and risk for severe COVID-19 (Supplementary Table 2). Similar trends were found across different individual and composite solicited local and systemic ARs.

Figure 3.

Distribution of neutralizing antibody titers (ID50) in mRNA-1273 vaccine recipients with and without adverse reactions. Neutralizing antibody titers (ID50) by pseudovirus neutralizing antibody assay in log10 scale at baseline (prior to injection 1), day 29 (prior to injection 2, 28 days post–injection 1), and day 57 (57 days post–injection 1, 28 days post–injection 2) after receipt of injections 1 and 2 of the mRNA-1273 vaccine in participants with (red) and without (blue) adverse reactions after 1 injection (A) and 2 injections (B). P values by linear mixed-effects models with Bonferroni multiplicity adjustment. Abbreviations: ID50, 50% inhibitory dilution.

Table 2.

Neutralizing Antibody Titers (ID50) by Any Adverse Reactions and Systemic Adverse Reactions Within 7 Days After the First and Second Injections

| Solicited AR | GMT (95%CI)a First Injection (N=1671) | GMT (95%CI)a Second Injection (N=1671) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With AR | Without AR | GMR (95% CI) |

With AR | Without AR | GMR (95% CI) |

|

| Any ARs | ||||||

| ȃDay 29 | 58.5 (54.3, 63.1) | 49.5 (41.2, 59.5) | 1.18 (0.88, 1.59) | 59.1 (55.0, 63.6) | 40.2 (31.8, 50.6) | 1.47 (1.02, 2.12)b |

| ȃDay 57 | 1184.3 (1126.6, 1245.0) | 1070.3 (932.5, 1228.5) | 1.11 (.89, 1.38) | 1190.7 (1133.8, 1250.5) | 949.3 (800.8, 1125.4) | 1.25 (.96, 1.63) |

| Systemic ARs | ||||||

| ȃDay 29 | 59.8 (54.5, 65.6) | 54.0 (48.7, 59.9) | 1.11 (.90, 1.36) | 61.0 (56.4, 66.1) | 45.9 (39.9, 52.9) | 1.33 (1.04, 1.69)b |

| ȃDay 57 | 1189.6 (1119.7, 1263.9) | 1144.2 (1064.6, 1229.6) | 1.04 (.91, 1.19) | 1227.2 (1164.4, 1293.5) | 980.1 (886.8, 1083.2) | 1.25 (1.06, 1.48)b |

| Headache | ||||||

| ȃDay 29 | 59.4 (52.7, 67.1) | 56.2 (51.6, 61.1) | 1.06 (.85, 1.32) | 64.1 (58.4, 70.4) | 49.5 (44.7, 54.8) | 1.30 (1.06, 1.59)b |

| ȃDay 57 | 1168.2 (1081.5, 1261.8) | 1172.1 (1105.8, 1242.4) | 1.00 (.86, 1.15) | 1263.8 (1190.1, 1342.2) | 1046.8 (973.7, 1125.3) | 1.21 (1.05, 1.39)b |

| Fatigue | ||||||

| ȃDay 29 | 59.6 (53.2, 66.8) | 55.9 (51.2, 61.0) | 1.07 (.86, 1.32) | 63.5 (58.2, 69.3) | 48.3 (43.3, 54.0) | 1.31 (1.07, 1.62)b |

| ȃDay 57 | 1174.9 (1092.1, 1263.9) | 1168.3 (1100.2, 1240.6) | 1.01 (.88, 1.16) | 1238.7 (1168.1, 1313.5) | 1065.1 (987.5, 1148.7) | 1.16 (1.01, 1.34)b |

| Myalgia | ||||||

| ȃDay 29 | 58.4 (50.7, 67.4) | 56.8 (52.5, 61.5) | 1.03 (.81, 1.31) | 64.8 (59.0, 71.1) | 49.7 (44.9, 54.9) | 1.30 (1.06, 1.60)b |

| ȃDay 57 | 1218.3 (1108.7, 1338.9) | 1155.6 (1095.2, 1219.3) | 1.05 (.90, 1.24) | 1240.0 (1162.8, 1322.2) | 1101.1 (1030.0, 1177.0) | 1.13 (.98, 1.29) |

| Arthralgia | ||||||

| ȃDay 29 | 57.0 (48.3, 67.2) | 57.3 (53.1, 61.8) | .99 (.76, 1.30) | 65.4 (58.7, 72.8) | 52.3 (47.8, 57.2) | 1.25 (1.02, 1.54)b |

| ȃDay 57 | 1184.6 (1060.3, 1323.5) | 1168.6 (1109.8, 1230.5) | 1.01 (.85, 1.21) | 1235.2 (1147.5, 1329.7) | 1133.1 (1067.7, 1202.6) | 1.09 (.95, 1.25) |

| Nausea or vomiting | ||||||

| ȃDay 29 | 60.1 (47.1, 76.7) | 57.0 (53.0, 61.3) | 1.05 (.72, 1.54) | 66.7 (56.7, 78.5) | 55.2 (51.2, 59.6) | 1.21 (.92, 1.58) |

| ȃDay 57 | 1128.6 (968.0, 1315.9) | 1175.1 (1118.4, 1234.7) | .96 (.76, 1.22) | 1320.0 (1193.9, 1459.4) | 1135.3 (1077.1, 1196.6) | 1.16 (.98, 1.37) |

| Chills | ||||||

| ȃDay 29 | 79.7 (62.8, 101.1) | 55.3 (51.4, 59.4) | 1.44 (.99, 2.09) | 71.9 (64.6, 79.9) | 48.6 (44.5, 53.2) | 1.48 (1.20, 1.82)b |

| ȃDay 57 | 1475.6 (1287.0, 1691.8) | 1137.7 (1082.4, 1195.8) | 1.30 (1.04, 1.61)b | 1310.7 (1222.2, 1405.5) | 1074.3 (1010.4, 1142.2) | 1.22 (1.06, 1.40)b |

| Fever | ||||||

| ȃDay 29 | 89.8 (34.3, 234.9) | 57.1 (53.3, 61.3) | 1.57 (.37, 6.66) | 82.0 (68.4, 98.4) | 53.9 (50.0, 58.0) | 1.52 (1.14, 2.04)b |

| ȃDay 57 | 1546.8 (886.3, 2699.6) | 1169.9 (1115.6, 1226.7) | 1.32 (.57, 3.05) | 1612.0 (1432.6, 1814.0) | 1109.0 (1054.5, 1166.3) | 1.45 (1.20, 1.76)b |

Any ARs included any local and systemic ARs. Quantified by a validated pseudotyped virus neutralization assay against the Wuhan-Hu-1 D614G isolate with an ID50. GMTs were assessed at days 29 and 57 following injections 1 and 2. Day 29 = pre-injection 2 and 28 days post-injection 1. Day 57 = 57 days post-injection 1 and 28 days post-injection 2. Immunogenicity was assessed in the blinded periods of the COVE trial at days 1, 29, and 57 and the TeenCOVE trial at days 1 and 57. Abbreviations: AR, adverse reaction; CI, confidence interval; COVE, Coronavirus Efficacy trial in adults; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; GMR, geometric mean ratio (with and without ARs); GMT, geometric mean titer estimated by geometric least squares mean; ID50, 50% inhibitory dilution; TeenCOVE, phase 2/3 trial in adolescents.

The log-transformed antibody levels were analyzed using linear mixed-effects models with the group variable (with and without ARs), the follow-up time, and the interaction between the group and follow-up time as fixed effects, including age category, gender, combined race and ethnicity group, and risk for severe COVID-19 as covariates.

Significant difference by Bonferroni adjustment controlling for an overall significance level of 0.05.

Table 3.

Neutralizing Antibody Titers (ID50) by Local Adverse Reactions Within 7 Days After the First and Second Injections

| Solicited ARs | GMT (95%CI)a First Injection (N=1671) | GMR (95% CI) |

GMT (95%CI)a Second Injection (N=1671) | GMR (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With AR | Without AR | With AR | Without AR | |||

| Local ARs | ||||||

| ȃDay 29 | 58.9 (54.6, 63.6) | 49.2 (41.8, 58.0) | 1.20 (.91, 1.57) | 59.5 (55.2, 64.1) | 44.8 (37.3, 54.0) | 1.33 (.99, 1.79) |

| ȃDay 57 | 1196.5 (1137.2, 1258.8) | 1030.7 (912.8, 1163.8) | 1.16 (.95, 1.41) | 1184.7 (1126.6, 1245.7) | 1078.5 (945.0, 1230.9) | 1.10 (.89, 1.36) |

| Pain | ||||||

| ȃDay 29 | 58.9 (54.6, 63.6) | 49.5 (42.2, 58.2) | 1.19 (.91, 1.55) | 59.4 (55.1, 64.0) | 45.7 (38.1, 54.9) | 1.30 (.97, 1.74) |

| ȃDay 57 | 1197.0 (1137.5, 1259.7) | 1035.4 (919.7, 1165.7) | 1.16 (.95, 1.40) | 1183.4 (1125.2, 1244.6) | 1092.5 (960.6, 1242.4) | 1.08 (.88, 1.33) |

| Axillary swelling or tenderness | ||||||

| ȃDay 29 | 75.4 (60.4, 94.3) | 55.4 (51.5, 59.6) | 1.36 (.96, 1.93) | 70.6 (58.8, 84.7) | 55.2 (51.2, 59.5) | 1.28 (.95, 1.72) |

| ȃDay 57 | 1347.9 (1191.5, 1524.9) | 1145.3 (1088.6, 1204.9) | 1.18 (.97, 1.44) | 1350.5 (1205.9, 1512.4) | 1139.5 (1082.5, 1199.4) | 1.19 (.99, 1.42) |

| Swelling (hardness) | ||||||

| ȃDay 29 | 69.0 (51.9, 91.8) | 56.6 (52.6, 60.8) | 1.22 (.79, 1.89) | 68.3 (56.4, 82.9) | 55.8 (51.8, 60.1) | 1.23 (.90, 1.67) |

| ȃDay 57 | 1283.1 (1095.8, 1502.4) | 1161.7 (1105.8, 1220.4) | 1.10 (.86, 1.41) | 1239.7 (1097.0, 1401.0) | 1160.1 (1102.6, 1220.5) | 1.07 (.88, 1.30) |

| Erythema (redness) | ||||||

| ȃDay 29 | 81.4 (54.1, 122.5) | 56.6 (52.7, 60.7) | 1.44 (.77, 2.68) | 76.1 (60.7, 95.3) | 55.6 (51.7, 59.8) | 1.37 (.96, 1.95) |

| ȃDay 57 | 1305.8 (1075.2, 1585.9) | 1163.6 (1108.3, 1221.7) | 1.12 (.83, 1.51) | 1285.1 (1120.6, 1473.7) | 1158.1 (1101.5, 1217.5) | 1.11 (.89, 1.38) |

Immunogenicity was assessed in the blinded periods of the COVE trial at days 1, 29, and 57 and TeenCOVE trial at days 1 and 57. Quantified by a validated pseudotyped virus neutralization assay against the Wuhan-Hu-1 D614G isolate with ID50. Abbreviations: AR, adverse reaction; CI, confidence interval; COVE, Coronavirus Efficacy trial in adults; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; GMR, geometric mean ratio (with and without ARs); GMT, geometric mean titer estimated by geometric least squares mean; ID50, 50% inhibitory dilution; TeenCOVE, phase 2/3 trial in adolescents.

The log-transformed antibody levels were analyzed using linear mixed-effects models with the group variable (with and without ARs), the follow-up time, and the interaction between the group and follow-up time as fixed effects, including age category, gender, combined race and ethnicity group, and risk for severe COVID-19 as covariates.

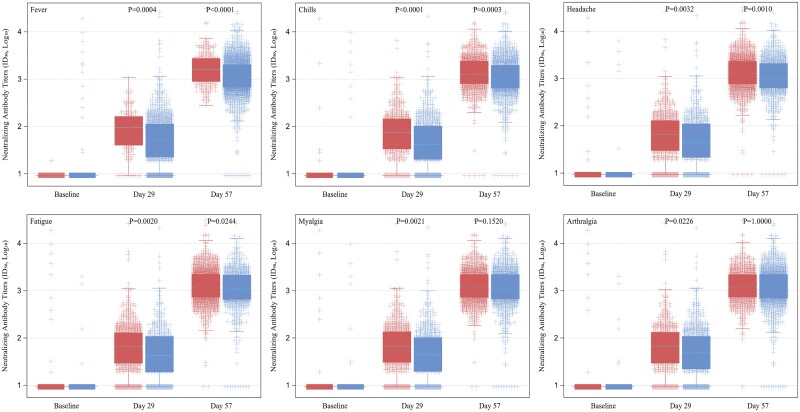

The associations of individual solicited ARs after the first and second injections with immunogenicity outcomes were assessed. Significantly higher day 29 GMTs were associated with the occurrence of systemic ARs of headache, fatigue, arthralgia, myalgia, chills, and fever after the second injection. Significantly higher day 57 GMTs were observed in participants who experienced systemic ARs of chills after the first injection and headache, fatigue, chills, and fever after the second injection compared with those without (Table 2, Figure 4, and Supplementary Figure 1). However, significant associations of GMTs with the occurrence of any individual local ARs after both injections were not found (Table 3). In separate analyses of each trial, significant associations between ARs and nAb titers were found in the COVE trial, consistent with those observed in the combined analysis population; however, associations were not significant in the TeenCOVE trial (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 4.

Distribution of neutralizing antibody titers (ID50) in mRNA-1273 vaccine recipients with and without individual systemic solicited events within 7 days after second injection. Neutralizing antibody titers (ID50) by pseudovirus neutralizing antibody assay in log10 scale at baseline, day 29, and day 57 after receipt of mRNA-1273 vaccine in participants with (red) and without (blue) individual systemic solicited events within 7 days after the second injection. P values by linear mixed-effects models with Bonferroni multiplicity adjustment. Abbreviation: ID50, 50% inhibitory dilution.

Significantly higher day 29 GMTs were associated with multiple reactions of headache, fatigue, arthralgia, myalgia, and chills after the second injection (GMR: 1.67 [1.11–2.50]; P = .001). Significantly higher day 57 GMTs were associated with multiple reactions of headache, fatigue, arthralgia, myalgia, chills, and fever after the second injection (GMR: 1.54 [1.08–2.20]; P = .002). Specifically, significantly higher day 29 (GMR: 1.67 [1.11–2.50]; P < .001) and day 57 (GMR: 1.78 [1.24–2.57]; P < .001) GMTs were also associated with chills and fever together after the second injection (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6).

Spike bAb results were available for 1043 of the 1055 COVE participants in the immunogenicity set and were generally similar to those seen for nAb results (Supplementary Table 7). Levels of bAb were significantly higher in participants with local ARs at day 29, including pain after both injections and erythema after the second injection. Significantly higher bAb levels were observed in participants with systemic reactions after the second injection, including fatigue, arthralgia, and nausea at day 29 and headache, myalgia, chills, and fever at both days 29 and 57.

Higher nAb titers were also generally observed in participants reporting severe systemic reactions than those reporting mild or moderate or none after the second injection (Supplementary Table 8). Day 29 and 57 GMTs were higher with any, local, and systemic severe ARs after the second injection than those with mild/moderate ARs and those without ARs (day 57 GMRs: 1.36 [1.06–1.74] and 1.23 [1.02–1.48] for systemic severe and mild/moderate vs without ARs after the second injection, respectively). The overall results were also generally consistent with those for ID80 titers (Supplementary Tables 9–11) and among subgroup and sensitivity analyses.

DISCUSSION

In this study, 2 injections of 100-µg mRNA-1273 vaccine elicited robust nAb titers at day 57 in participants combined from the primary immunogenicity sets of the blinded periods of the adult (COVE) and adolescent (TeenCOVE) trials, regardless of whether participants reported ARs [1, 23]. We found that higher nAb titers measured at days 29 and 57 were significantly associated with the occurrence of solicited systemic ARs after the second injection, whereas associations with local ARs were not significant after any injection. Higher nAb titers were significantly associated with the occurrence of individual systemic ARs of chills after the first injection and fever, chills, headache, fatigue, arthralgia, and myalgia after the second injection. Significantly higher spike bAb levels were also observed in those with systemic ARs after the second injection in participants in the COVE trial.

The reactogenicity and immunogenicity observed after 2 injections of mRNA-1273 were previously reported in the COVE and TeenCOVE trials [1, 4, 23]. The vaccine induced high nAb titers after the first injection, which increased substantially after the second injection, as well as mild-to-moderate local and systemic ARs in a majority of individuals at higher frequencies and increased severity of systemic ARs following the second injection. Increased reactogenicity has been observed after repeated doses for other vaccines, attributed to pre-existing immunity acquired following natural infection or vaccination, and is associated with robust humoral and cell-mediated responses upon additional doses [11]. The finding of significant associations of systemic ARs following the second injection in our study may be a result of immunity acquired after the first injection as evidenced by increased nAb titers seen in participants at day 29 (pre-injection 2) and related to the induction of pathways of inflammatory responses by vaccine antigens that release immune mediators and products of inflammation into the circulation, which have been shown to be associated with systemic reactogenicity [11, 14, 17, 18]. In line with this, studies have shown that mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines elicit higher antibody responses following single vaccinations in previously SARS-CoV-2–infected individuals versus those who are infection naive, including mRNA-1273, which elicited 27-fold and 3-fold higher nAb titers in those who were SARS-CoV-2 positive versus negative at baseline following the first and second injections in the COVE trial [4, 25–27]. Additionally, booster doses of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines induce rapid increases in nAb and/or S-specific T-cell responses [7, 26, 28, 29]. Taken together, these studies suggest memory recall of pre-existing, priming-induced immunity.

While our findings are the first to suggest a relationship between the reactogenicity and immunogenicity of mRNA-1273 vaccine, the clinical significance of higher antibody titers in those with systemic ARs remains unclear. Studies of such a relationship have yielded mixed results, with some studies indicating associations with systemic ARs after the second injection but no association with local ARs and other studies that have not shown any relationship [19–22]. The inconsistency in results of past and current studies may be partly attributed to differing study methods and antibody assays used in the assessments, as well as fundamental differences in the composition and administration of the vaccines. The mRNA vaccines have demonstrated high efficacy and safety; however, apparent differences observed in immune responses and comparative effectiveness have been attributed to differing mRNA doses, intervals of boosting and priming, and/or lipid nanoparticle formulations used in packaging and optimization of the mRNA vaccines [19–22, 30, 31]. Additionally, ARs such as fatigue, headache, pain, and myalgia were most commonly reported in both placebo and vaccine participants in COVID-19 vaccine trials, although the frequencies of occurrence were higher in the vaccine groups, indicating that individual perception and expectations may also influence AR symptoms [12].

Higher spike bAb levels were also significantly associated with systemic ARs after the second injection, supporting the findings for nAb titers. The additional associations of bAb levels with local ARs observed at day 29, including pain after both injections and erythema after the second injection, are reflected by the robust increases in bAb levels observed at day 29 compared with nAb titers. These results are consistent with previous reports of the concordance of bAb levels and nAb titers in relation to immunogenicity and vaccine efficacy against mild COVID-19 [4, 32–34].

Solicited ARs following COVID-19 vaccination were shown to be more prevalent in women and younger individuals in community settings as well as in mRNA-1273 vaccine trials [1, 15]. Rates of ARs following vaccination are higher during childhood to young adulthood as the immune system matures, then decline later in life, partly due to immunosenescence and waning immunity [11]. In this study, immunogenicity following vaccination was higher in younger participants across individual characteristics (eg, gender, race, ethnicity, obesity) but were not different among gender, race, and ethnicity and severe COVID-19 risk subgroups, consistent with the immunogenicity and efficacies demonstrated in these groups in mRNA-1273 trials [4, 23].

Some study limitations are noteworthy. We established an association, and caution against causal inferences between AR symptoms and immunogenicity outcomes. While the baseline characteristics and demographic data are consistent with those of the trial populations, the results cannot necessarily be generalized to other groups not assessed in this study, including younger children (<12 years), pregnant women, immunocompromised individuals, and those with previous histories of vaccination or COVID-19 infection; however, the safety and immunogenicity of these populations have been previously reported [4, 35–37]. Although the frequencies of solicited ARs have been reported in the larger, overall safety sets of the COVE and TeenCOVE trials, the numbers of SARS-CoV-2–positive cases in the immunogenicity sets of these trials were insufficient to assess the associations of immunogenicity and reactogenicity in this study [1, 4, 38]. This study did not evaluate the relationship between solicited ARs and molecular pathways involved in the reactogenicity and the immune response; however, such investigations are currently being pursued in other vaccine clinical trials.

This present study has important strengths. The data were obtained from large and diverse study populations of randomized clinical trials designed to ensure that solicited local and systemic ARs occurred more frequently in the vaccine than the placebo participants, removing systematic biases and the nocebo effects that have been questionable in clinical practice for SARS-CoV-2 vaccines [12]. The use of longitudinal models evaluating within- and between-participant variations over time yielded consistently robust results across the differing analysis approaches, including the penalized linear mixed-effects models. Additional clinical trials that include longer follow-up times after priming-series and booster vaccinations may provide a deeper understanding of the causal association between inflammatory symptoms and immunogenicity outcomes.

Our results add to the current understanding of relationships between immunogenicity and reactogenicity and may contribute toward the design of future mRNA vaccines that provide effective immune responses with less reactogenicity by mitigating undesirable innate immune activation. While the study results indicate that systemic ARs are associated with higher antibody titers, it should be noted that mRNA-1273 vaccination elicits robust immune responses regardless of the occurrence of ARs, consistent with its demonstrated efficacy.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary material is available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Uma Siangphoe, Infectious Disease Development, Moderna, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Lindsey R Baden, Division of Infectious Diseases, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Hana M El Sahly, Molecular Virology and Microbiology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA.

Brandon Essink, Meridian Clinical Research, Savannah, Georgia, USA.

Kashif Ali, Kool Kids Pediatrics, DM Clinical Research, Houston, Texas, USA.

Gary Berman, The Clinical Research Institute, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Joanne E Tomassini, Infectious Disease Development, Moderna, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Weiping Deng, Infectious Disease Development, Moderna, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Rolando Pajon, Infectious Disease Development, Moderna, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Roderick McPhee, Infectious Disease Development, Moderna, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Avika Dixit, Infectious Disease Development, Moderna, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Rituparna Das, Infectious Disease Development, Moderna, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Jacqueline M Miller, Infectious Disease Development, Moderna, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Honghong Zhou, Infectious Disease Development, Moderna, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Notes

Data availability statement. As the trials are ongoing, access to patient-level data and supporting clinical documents with qualified external researchers may be available upon request and subject to review once the trial is complete.

Authors’ contributions. U. S., L. R. B., H. M. E. S., and H. Z. contributed to the design and/or the analyses. U. S., L. R. B., H. M. E. S., B. E., K. A., G. B., J. E. T., W. D., R. P., R. D., J. M. M., and H. Z. contributed to the review and/or interpretation of the data. U. S. and J. E. T. developed the initial draft. All authors contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the trial participants and their families and the study staff across centers for their dedication and devotion in implementing the protocol. They also thank David C. Montefiori and the Immune Assay team at Duke University Medical Center for neutralization assays and Adrian McDermont and the Vaccine Research Center, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH) team for MSD Multiplex assays.

Financial support. The Coronavirus Efficacy (COVE; NCT04470427) and TeenCOVE (NCT04649151) trials were supported by Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (contract 75A50120C00034), and by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). For the COVE trial, NIAID provided grant funding to the HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN) Leadership and Operations Center (grant number UM1 AI 68614HVTN), the Statistics and Data Management Center (grant number UM1 AI 68635), the HVTN Laboratory Center (grant number UM1 AI 68618), the HIV Prevention Trials Network Leadership and Operations Center (grant number UM1 AI 68619), the AIDS Clinical Trials Group Leadership and Operations Center (grant number UM1 AI 68636), and the Infectious Diseases Clinical Research Consortium leadership group 5 (grant number UM1 AI148684-03). The Duke laboratory received funding for sample analysis from Moderna, Inc.

Potential conflicts of interest. L. R. B. reports grants from NIH/NIAID (grant number UM1AI069412) for the conduct of this study and received grants from Wellcome Trust and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and is involved in vaccine clinical trials conducted in collaboration with the NIH, HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN), COVID Vaccine Prevention Network (CoVPN), International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI), Crucell/Janssen, Moderna, Military HIV Research Program (MHRP), Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Ragon Institute, H. M. E. S. reports grants from NIH and/or NIAID (grant number 3UM1AI148575-01S2) during the conduct of the study. K. A. reports funding to DM Clinical Research. U. S., W. D., A. D., R. D., R. M., J. M. M., R. P., and H. Z. report being employees of Moderna, Inc, and may hold stock/stock options in the company. J. E. T. is a Moderna consultant. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. El Sahly HM, Baden LR, Essink B, et al. Efficacy of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine at completion of blinded phase. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:1774–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thomas SJ, Moreira ED, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine through 6 months. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:1761–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moderna, Inc . The authorization or approval status of Moderna COVID 19 vaccine in the U.S. and other countries. Available at:https://modernacovid19global.com/en-US. Accessed 15 August 2022.

- 4. El Sahly HM, Baden LR, Essink B, et al. Humoral immunogenicity of the mRNA-1273 vaccine in the phase 3 COVE trial [manuscript published online ahead of print]. J Infect Dis 2022:jiac188. Available at: 10.1093/infdis/jiac188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Phase 3 trial of mRNA-1273 during the Delta-variant surge. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:2485–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Choi A, Koch M, Wu K, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 variant mRNA vaccine boosters in healthy adults: an interim analysis. Nat Med 2021; 27:2025–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chu L, Vrbicky K, Montefiori D, et al. Immune response to SARS-CoV-2 after a booster of mRNA-1273: an open-label phase 2 trial. Nat Med 2022; 28:1042–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pajon R, Doria-Rose NA, Shen X, et al. SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant neutralization after mRNA-1273 booster vaccination. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:1088–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pegu A, O’Connell SE, Schmidt SD, et al. Durability of mRNA-1273 vaccine–induced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants. Science 2021; 373:1372–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chalkias S, Harper C, Vrbicky K, et al. A bivalent omicron-containing booster vaccine against Covid-19. N Engl J Med2022; 387(14):1279–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Herve C, Laupeze B, Del Giudice G, Didierlaurent AM, Da Silva FT. The how's and what's of vaccine reactogenicity. NPJ Vaccines 2019; 4:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Amanzio M, Mitsikostas DD, Giovannelli F, Bartoli M, Cipriani GE, Brown WA. Adverse events of active and placebo groups in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine randomized trials: a systematic review. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2022; 12:100253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beutler B. Microbe sensing, positive feedback loops, and the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases. Immunol Rev 2009; 227:248–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chan CYY, Chan KR, Chua CJH, et al. Early molecular correlates of adverse events following yellow fever vaccination. JCI Insight 2017; 2:e96031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chapin-Bardales J, Gee J, Myers T. Reactogenicity following receipt of mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines. JAMA 2021; 325:2201–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. August A, Brito L, Paris R, Zaks T. Clinical development of mRNA vaccines: challenges and opportunities [manuscript published online 2022]. Curr Top Microbiol 2022. Available at: 10.1007/82_2022_259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stuart LM. In gratitude for mRNA vaccines. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:1436–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Teijaro JR, Farber DL. COVID-19 vaccines: modes of immune activation and future challenges. Nat Rev Immunol 2021; 21:195–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Coggins SA, Laing ED, Olsen CH, et al. Adverse effects and antibody titers in response to the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in a prospective study of healthcare workers. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021; 9:ofab575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hwang YH, Song KH, Choi Y, et al. Can reactogenicity predict immunogenicity after COVID-19 vaccination? Korean J Intern Med 2021; 36:1486–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Held J, Esse J, Tascilar K, et al. Reactogenicity correlates only weakly with humoral immunogenicity after COVID-19 vaccination with BNT162b2 mRNA (Comirnaty®). Vaccines 2021; 10:1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Uwamino Y, Kurafuji T, Sato Y, et al. Young age, female sex, and presence of systemic adverse reactions are associated with high post-vaccination antibody titer after two doses of BNT162b2 mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: an observational study of 646 Japanese healthcare workers and university staff. Vaccine 2022; 40:1019–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ali K, Berman G, Zhou H, et al. Evaluation of mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in adolescents. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:2241–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) . FDA, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, U.S. Guidance for industry: toxicity grading scale for healthy adult and adolescent volunteers enrolled in preventive vaccine clinical trials. Available at:https://www.fda.gov/media/73679/download. Accessed 15 August 2022.

- 25. Samanovic MI, Cornelius AR, Gray-Gaillard SL, et al. Robust immune responses are observed after one dose of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine dose in SARS-CoV-2–experienced individuals. Sci Transl Med 2022; 14:eabi8961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goel RR, Apostolidis SA, Painter MM, et al. Distinct antibody and memory B cell responses in SARS-CoV-2 naïve and recovered individuals after mRNA vaccination. Sci Immunol 2021; 6:eabi6950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jabal KA, Ben-Amram H, Beiruti K, et al. Impact of age, ethnicity, sex and prior infection status on immunogenicity following a single dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine: real-world evidence from healthcare workers, Israel, December 2020 to January 2021. Eurosurveillance 2021; 26:2100096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sablerolles RSG, Rietdijk WJR, Goorhuis A, et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of vaccine boosters after Ad26.COV2.S priming. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:951–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moreira ED, Kitchin N, Xu X, et al. Safety and efficacy of a third dose of BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:1910–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Müller L, Andrée M, Moskorz W, et al. Age-dependent immune response to the biontech/pfizer BNT162b2 coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:2065–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dickerman BA, Gerlovin H, Madenci AL, et al. Comparative effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccines in U.S. Veterans. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:105–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gilbert PB, Montefiori DC, McDermott AB, et al. Immune correlates analysis of the mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine efficacy clinical trial. Science 2022; 375:43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med 2021; 27:1205–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Plotkin SA. Updates on immunologic correlates of vaccine-induced protection. Vaccine 2020; 38:2250–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Speich B, Chammartin F, Abela IA, et al. Antibody response in immunocompromised patients after the administration of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 75:e585–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Creech CB, Anderson E, Berthaud V, et al. Evaluation of mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine in children 6 to 11 years of age. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:2011–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Collier AY, McMahan K, Yu J, et al. Immunogenicity of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines in pregnant and lactating women. JAMA 2021; 325:2370–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. US Food and Drug Administration . FDA briefing document: EUA amendment request for use of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine in children 6 months through 17 years of age. Available at:https://www.fda.gov/media/159189/download. Accessed 15 August 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.