Keywords: gut microbiome, kidney transcriptomics, RNA sequencing, sex differences

Abstract

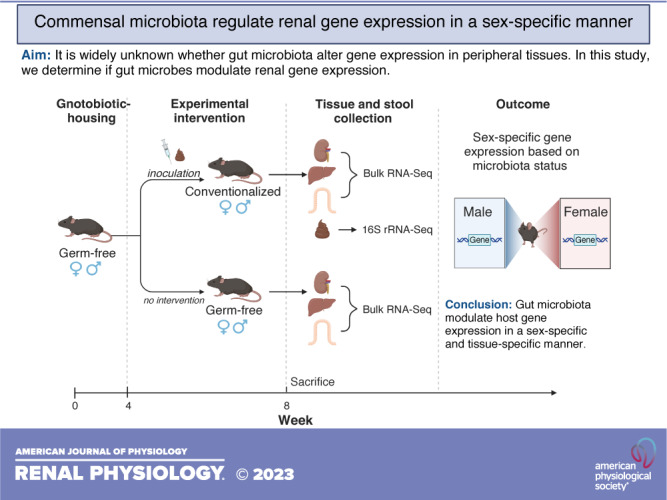

The gut microbiome impacts host gene expression not only in the colon but also at distal sites including the liver, white adipose tissue, and spleen. The gut microbiome also influences the kidney and is associated with renal diseases and pathologies; however, a role for the gut microbiome to modulate renal gene expression has not been examined. To determine if microbes modulate renal gene expression, we used whole organ RNA sequencing to compare gene expression in C57Bl/6 mice that were germ free (lacking gut microbiota) versus conventionalized (gut microbiota reintroduced using an oral gavage of a fecal slurry composed of mixed stool). 16S sequencing showed that male and female mice were similarly conventionalized, although Verrucomicrobia was higher in male mice. We found that renal gene expression was differentially regulated in the presence vs. absence of microbiota and that these changes were largely sex specific. Although microbes also influenced gene expression in the liver and large intestine, most differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the kidney were not similarly regulated in the liver or large intestine. This demonstrates that the influence of the gut microbiota on gene expression is tissue specific. However, a minority of genes (n = 4 in males and n = 6 in females) were similarly regulated in all three tissues examined, including genes associated with circadian rhythm (period 1 in males and period 2 in females) and metal binding (metallothionein 1 and metallothionein 2 in both males and females). Finally, using a previously published single-cell RNA-sequencing dataset, we assigned a subset of DEGs to specific kidney cell types, revealing clustering of DEGs by cell type and/or sex.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY It is unknown whether the microbiome influences host gene expression in the kidney. Here, we utilized an unbiased, bulk RNA-sequencing approach to compare gene expression in the kidneys of male and female mice with or without gut microbiota. This report demonstrates that renal gene expression is modulated by the microbiome in a sex- and tissue-specific manner.

INTRODUCTION

Gut microbiota are influential in maintaining host health (1), including both renal and cardiovascular function (2–4). For example, the fermentation of proteins within the gut can lead to the production of excess uremic toxins, such as indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate, and have been implicated in renal disease progression, including chronic kidney disease (CKD) (5, 6). In addition, animal models of CKD have inflamed digestive tracts in which tight junctions along the gut epithelium are disrupted and lead to a “leaky gut” (7). This breakdown of the gut barrier is responsible for the release of microbial DNA and endotoxins into the blood, where it has been detected in the serum of patients with CKD (7). Moreover, elevated circulating endotoxin levels correlate with CKD progression and severity (7, 8). Studies have also demonstrated a role for gut microbiota in cardiovascular health. For example, a fecal transplant using stool from patients with hypertension increased blood pressure in (formerly) germ-free (GF) mice (9). These studies and others indicate that gut microbiota are influential in regulating renal and cardiovascular health (2, 10–14).

Although previous reports have highlighted roles for microbial metabolites to alter host signaling pathways (15–18), recently it has been recognized that microbes also influence the host by modulating gene expression. For example, gut microbes modulate host gene regulation in colonic epithelial cells in vitro (19). Furthermore, GF mice (which entirely lack microbes) have altered gene expression in the liver, adipose, and large intestine (20), and GF piglets have decreased expression in immune-related genes within oral mucosae (21). However, the influence of microbes on renal gene expression has not been explored. To study the relationship between microbiota and renal gene expression, we used bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) of kidneys from GF and conventionalized (Conv) male and female mice and examined liver and large intestine transcriptomics for comparison. We found that microbiota influenced renal gene expression and that this influence was largely sex- and tissue specific.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Housing

All animal experiments were approved by the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee (accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care). All animals were born in sterile isolators within the Johns Hopkins GF Animal Facility. GF mice underwent weekly testing to confirm GF status and were also tested at euthanasia. Testing was performed via gram staining of collected fecal pellets, stool cultures on agar plates, and PCR testing on extracted fecal DNA using the following primers: 8F (5′- AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1391R (5′-GACGGGCGGTGWGTRCA-3′).

Conventionalization

Gut microbiota were introduced to a subset of GF mice (n = 10, equal number of males and females) at 4 wk of age via an oral gavage using a fecal slurry. The fecal slurry was composed of mixed stool from age-matched C57Bl/6J animals (n = 3 males and n = 3 females) who were fed a standard specific pathogen-free diet and housed in a standard (not GF) Animal Facility. The slurry was prepared under aerobic conditions. Each GF mouse was inoculated with 120 µL of slurry (4% weight by volume into sterile PBS).

Stool Collection and 16S Microbial Sequencing

Fecal samples from male (n = 5) and female (n = 5) Conv mice were collected at the time of euthanasia. Pellets were removed from the distal large intestine, collected on dry ice, and then stored at −80°C. For the isolation of bacterial DNA, we used the QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Cat. No. 51604, Qiagen), and fecal DNA was isolated following the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen). 16S microbial sequencing (2 × 300-bp paired-end reads) was performed using the Illumina MiSeq sequencing platform and standard Illumina sequencing primers. The Johns Hopkins University Single Cell and Transcriptomics Core performed library preparation and sequencing, and samples were analyzed by Resphera Biosciences. The Resphera database curates more than 11,000 unique species and was used for 16S taxonomic assignment. For analysis, Trimmomatic was used to assess paired-end reads for quality and a minimum length of 200 bp (22). FLASH (23) and QIIME (24) were used to merge reads and screen for quality, respectively. Sequences that were spurious hits to the Phix control genome were identified by BLASTN and removed. The remaining sequences were stripped of primers and assessed for chimeras using UCLUST (25) (de novo mode). To screen for contamination in sequencing reads, Bowtie2 was used to filter any mouse-associated contaminants, followed by BLASTN to screen against the GreenGenes 16S rRNA database (used in preprocessing to identify non-16S sequences that were incorrectly amplified). The RDP classifier (80% confidence threshold) was used to identify and filter any mitochondria or chloroplast contamination. High-quality 16S rRNA sequences were normalized to 94,000 sequences per sample and assigned to taxonomic lineages for downstream α diversity and taxonomic percent abundance estimates using Resphera Insight (26). 16S rRNA sequencing reads are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database (PRJNA910131).

Tissue Collection and RNA Isolation

At 8 wk of age, GF mice (n = 10) and Conv mice (n = 10) were euthanized by CO2. All experiments, including euthanasia and tissue collection, were performed during the light cycle between 10:00 AM and 1:00 PM. Tissues were harvested [whole kidney, left lobe of the liver, and distal portion of the large intestine (∼2 cm)], placed in TRIzol (Cat. No. 15596026, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and stored at −80°C. To collect RNA, tissues were homogenized using a KIMBLE Dounce tissue grinder set (Cat. No. D8938, Sigma-Aldrich), and RNA was isolated following the TRIzol protocol. The supernatant from the TRIzol protocol was collected and processed using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). For the kidneys, four samples were chosen for each group (male GF, female GF, male Conv, and female Conv) based on RNA quality number values, and these 16 samples were used for bulk RNA-Seq analysis. For the liver and large intestine, three samples were chosen from each group based on RNA quality number values. Sample sizes were chosen in consultation with the Johns Hopkins Single Cell and Transcriptomics Core as well as the Johns Hopkins GF Facility.

Bulk RNA-Seq and Analysis

RNA-Seq (2 × 150-bp paired-end reads) was performed using the Illumina NovaSeq sequencing platform. DESeq2 package and output were used to estimate variance mean dependence of all normalized count data and to determine differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Negative binomial generalized linear models were performed, and the estimates of dispersion and logarithmic fold changes (male-to-female ratio or Conv-to-GF ratio) to incorporate data-driven prior distributions were calculated (27). P values were attained by DESeq2 using the Wald test and corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini and Hochberg method. Differential gene expression was performed on each pair (male Conv:male GF, female Conv:female GF, male Conv:female Conv, and male GF:female GF).

The total number of genes identified and characterized was 14,949, 13,202, and 15,736 in the kidney, liver, and large intestine, respectively. Reads were mapped to the mouse reference genome (GRCm39, genecode.vM26). DEGs were defined as having base mean expression > 15 transcripts per kilobase million, |log2 fold change| ≥ 0.5, and P value ≤ 0.5. |log2 fold change| ≥ 0.5 corresponds to a male-to-female ratio or Conv-to-GF ratio ≤ 0.71 or ≥ 1.41. Data were analyzed by sex as well as by microbiota status. RNA-Seq raw counts for all three tissues are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database (kidney: PRJNA904759, liver: PRJNA906570, and large intestine: PRJNA907282).

To identify intergroup variability of gene expression between samples, we conducted hierarchical clustering using pheatmap in R on all three tissues. Raw normalized counts (per kilobases of transcript per 1 million mapped reads) for each gene were contained, SD was calculated across each sample for the kidney (n = 16), liver (n = 9), and large intestine (n = 9), and a subset of 100 genes was determined to be most variable. An agglomerative approach was used for clustering analysis.

Single-Cell RNA-Seq Comparisons

To determine if DEGs clustered to specific kidney cell types, we compared our bulk RNA-Seq data with a previously published single-cell RNA-Seq (scRNA-Seq) dataset (29). For this data set, the authors dissected whole kidneys of C57Bl/6J (8- to 9-wk old) male and female mice into three zones (the cortex, outer medulla, and inner medulla) and sequenced 31,625 cells. The authors assigned the cells to 13 distinct clusters, and the top 50 DEGs in each cluster, compared with all other cell types, were identified. To assign genes identified in our bulk RNA-Seq to these distinct clusters, we compared male and female DEGs (Conv vs. GF) to the list of genes identified as marker genes by the aforementioned scRNA-Seq study. Log2 fold change values from RNA-Seq data were then assigned to each gene within specific renal cell types and analyzed.

RESULTS

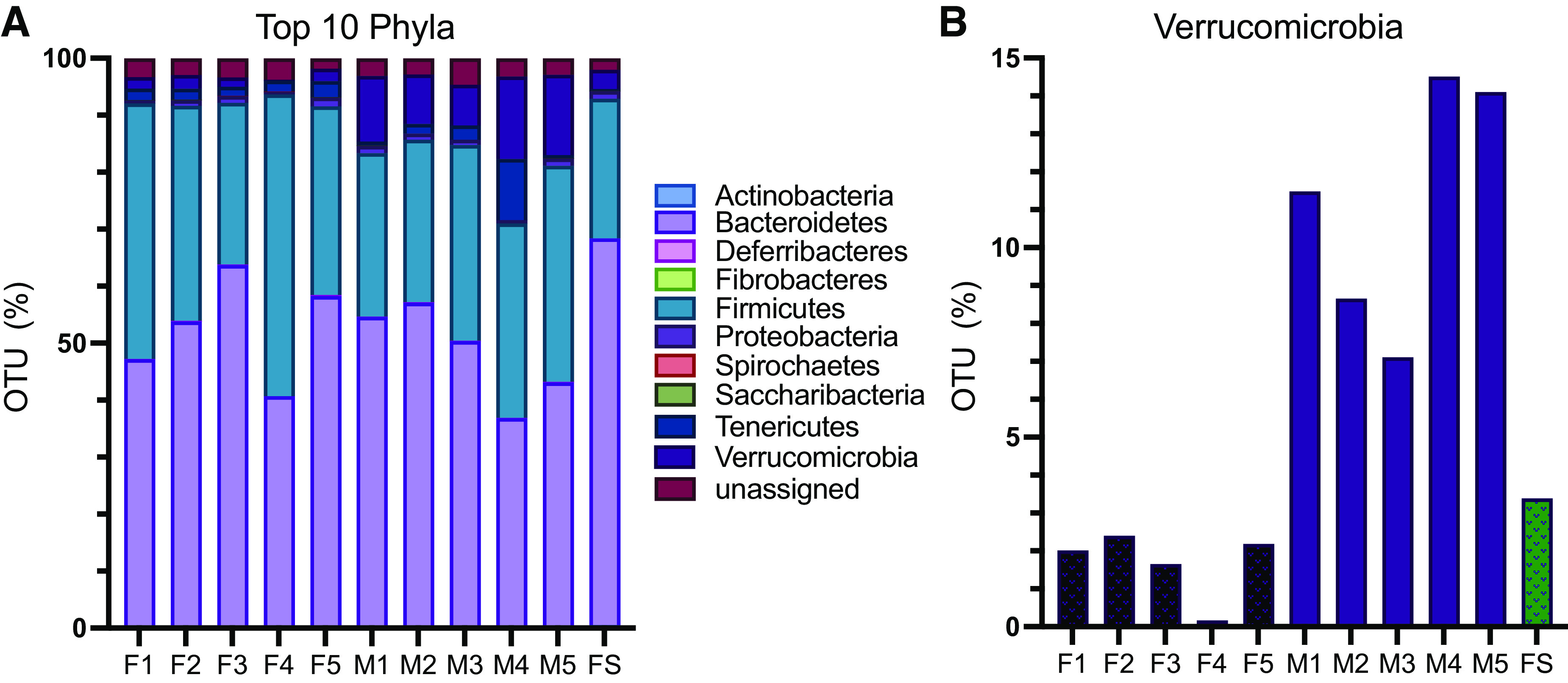

Conventionalization Is Similar in Male and Female Mice

Male and female mice were conventionalized using a fecal slurry that was an even mix from both male and female donors. To determine if there were any differences in conventionalization in male versus female recipients, we performed 16S rRNA sequencing on stool collected from male Conv and female Conv mice. In parallel, we analyzed the fecal slurry used for inoculation. Figure 1A shows the relative abundance of the top 10 major phyla. Conventionalization was similar in males and females across all phyla with the exception of Verrucomicrobia (1.68% of the gut microbiome in females and 11.17% in males; Fig. 1B). The Firmicutes-to-Bacteriodetes ratio (F:B) was also analyzed. We observed no significant difference (P = 0.62, t test) in F:B of male Conv (F:B = 0.68) versus female Conv (F:B = 0.75) mice.

Figure 1.

16S sequencing of conventionalized samples. Fecal samples from conventionalized mice were collected at euthanasia, and 16S RNA was sequenced. The fecal slurry (FS) used for inoculation was analyzed in parallel. A: relative abundance of the top 10 major phyla showing similar conventionalization in males (M) and females (F) across most phyla. B: Verrucomicrobia was significantly more abundant (P = 0.005, t test) among males vs. females.

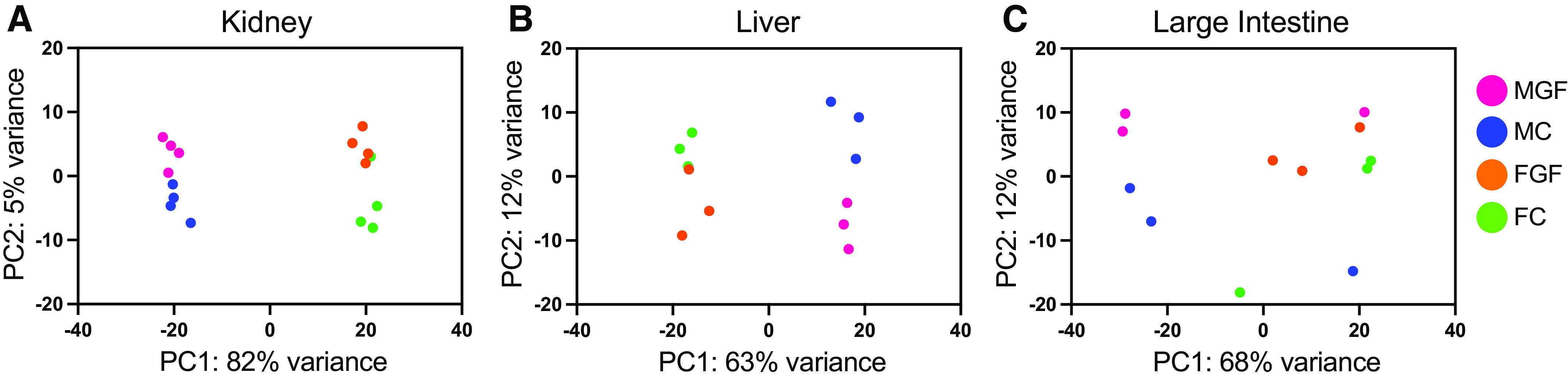

Both Sex and Microbial Status Influence Renal Gene Expression

Principal component (PC) analysis was used to analyze kidney RNA-Seq data (Fig. 2). In the kidney, samples clustered by sex (male vs. female) on the PC1 axis and by microbiome status (GF vs. Conv) on the PC2 axis (Fig. 2A). Clustering by sex and by microbiome status was also seen in the liver (Fig. 2B), but clear clustering by sex and/or microbiota status was not apparent in large intestine samples (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Principal component (PC) analysis of RNA-sequencing data from the kidney, liver, and large intestine. Principal component analysis was used to show the relationship between individual samples from the kidney (A), liver (B), and large intestine (C). FC, female conventionalized; FGF, female germ free; MC, male conventionalized; MGF, male germ free. Data from the kidney and liver clustered by sex along the PC1 axis and microbiota status along the PC2 axis.

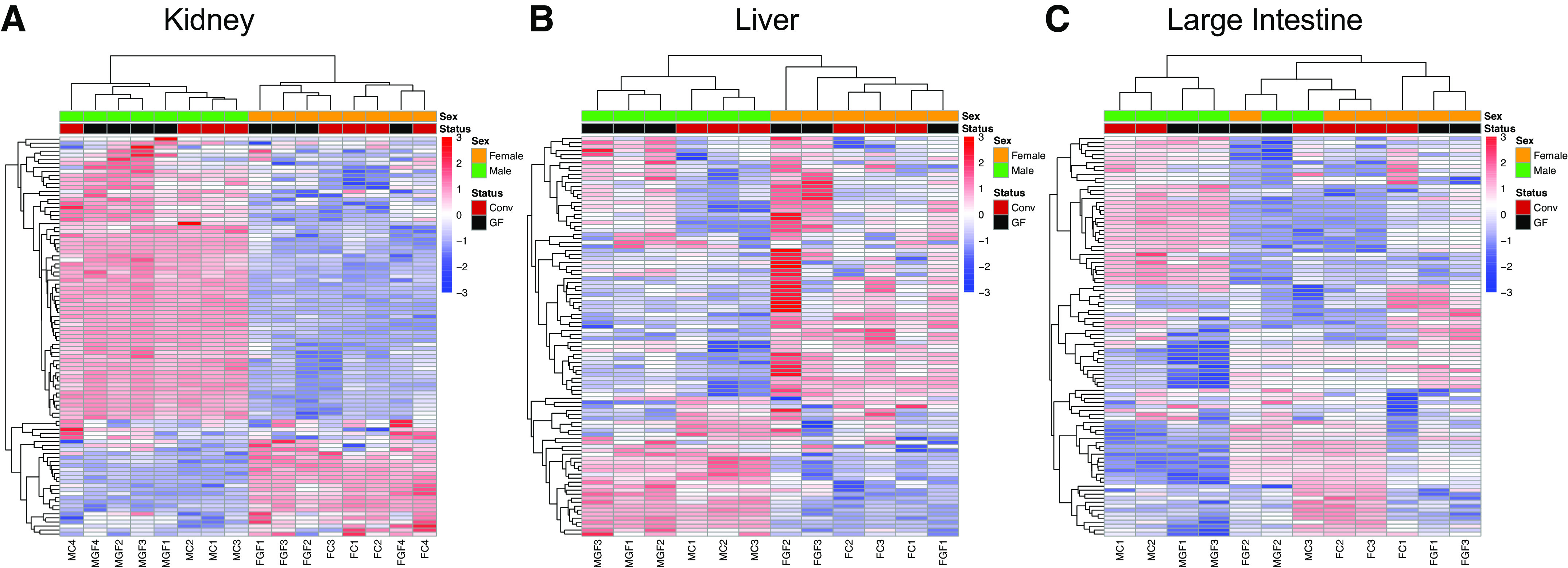

In agreement with the PC analysis, unsupervised hierarchical clustering showed that renal gene expression clustered entirely by sex and largely by GF or Conv status (Fig. 3A). By comparison, the liver demonstrated similar expression patterns to the kidney (Fig. 3B), whereas in the large intestine, these patterns were less clear (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the top 100 variable genes in the kidney, liver, and large intestine. Raw normalized counts (per kilobase of transcript per 1 million mapped reads) were used to calculate variability across all samples sequenced. For each gene, SD was calculated to determine variability. Conv, conventionalized; GF, germ free. A: clustering of the top 100 differentially expressed genes in the kidney showed clear separation by sex, with some separation by microbial status as well. B: sex was the dominant factor in clustering of liver differentially expressed genes, with microbial status also having a strong influence. C: the large intestine demonstrated the most variability between samples without distinct clustering by sex and/or microbiota status.

Microbiota-Dependent Changes in Gene Expression Are Unique to the Kidney

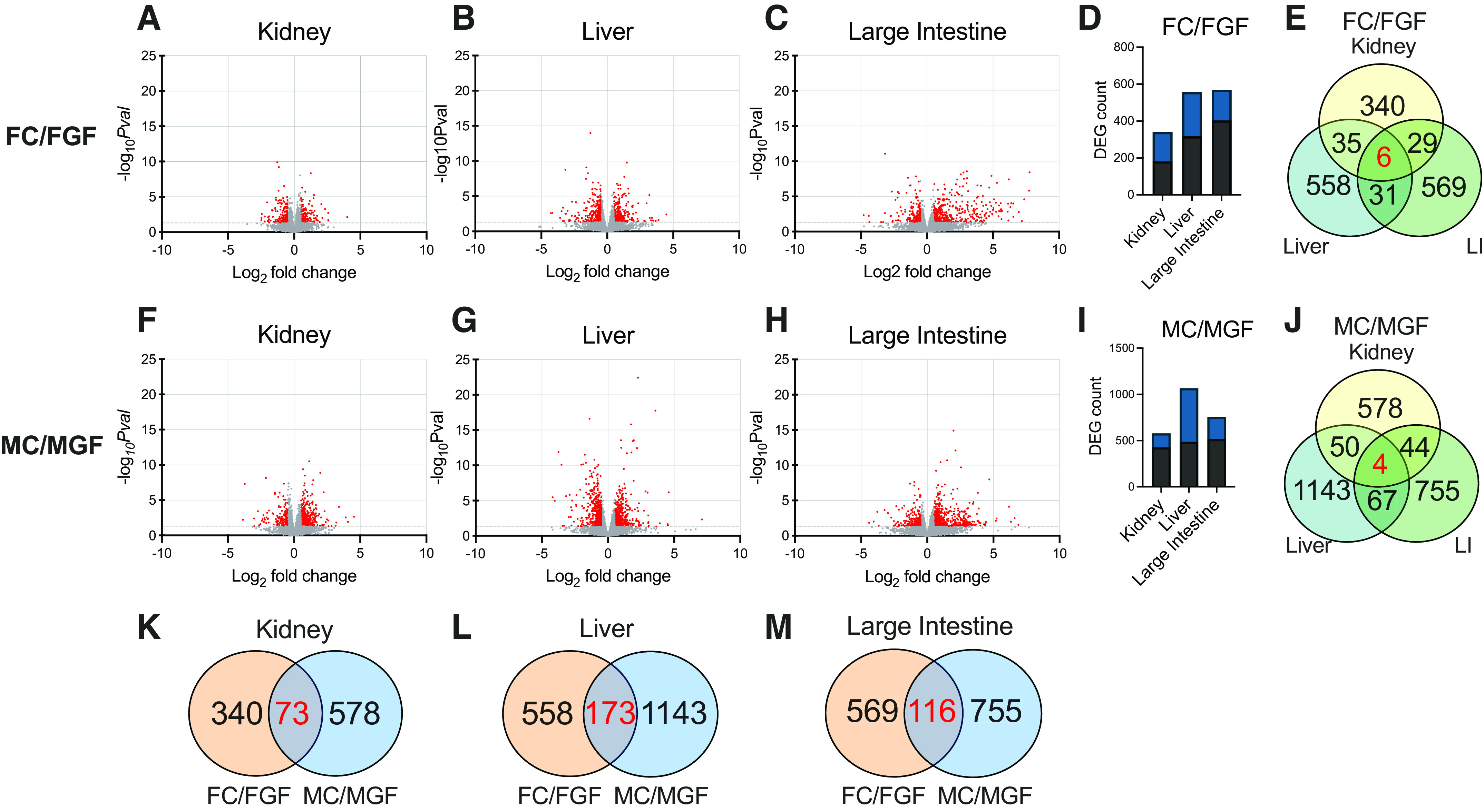

Genes differentially expressed by microbiome status are shown in Fig. 4. We found a number of genes differentially regulated by microbial status in the kidney in both males (340 DEGs) and females (578 DEGs); 51% of these DEGs were upregulated in the presence of gut microbes in females (Fig. 4D), and 74% of these DEGs were upregulated in the presence of gut microbes in males (Fig. 4I). We also observed a greater number of genes differentially regulated in the liver and large intestine compared with the kidney in both females (Fig. 4, B–D) and males (Fig. 4, G–I).

Figure 4.

Volcano plot analysis comparing conventionalized vs. germ-free data. Data are shown here separated by both tissue and sex. The total number of genes identified was 14,949 (kidney), 13,202 (liver), and 15,736 (large intestine). FC, female conventionalized; FGF, female germ free; MC, male conventionalized; MGF, male germ free. A–C and F–H: volcano plots illustrating differential expression calculated by microbial treatment (conventionalized:germ free). Genes with significant changes [P ≤ 0.05, which correspond to −log10 P value (−logPval) ≥ 1.3) are shown in red; genes without significant changes (−log10Pval ≤ 1.29) are shown in gray. D and I: total numbers of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified in each tissue with respect to males and females (conventionalized vs. germ free). DEGs were defined as follows: base mean ≥ 15, |log2 fold change| ≥ 0.5, P ≤ 0.05. Black bars represent the number of genes that were upregulated; blue bars represent the number of genes that were downregulated. E and J: Venn diagrams showing how many DEGs were in common across organs within each sex. E: six genes coregulated in females [period 2 (Per2), joining chain of multimeric IgA and IgM (Jchain), lipoprotein lipase (Lpl), exostosin-like glycosyltransferase 1 (Extl1), metallothionein 1 (Mt1), and metallothionein 2 (Mt2)]. J: four genes coregulated in males [period 1 (Per1), Mt1, Mt2, and forkhead box O3 (Foxo3)]. Venn diagrams comparing DEGs altered by gut microbiota in males and females in the kidney (K), liver (L), and large intestine (M). Over 90% of genes were either differentially regulated in females or males, and <10% of genes commonly regulated in both sexes. Differential expression was analyzed using separate pairwise comparisons. All P values were attained using the Wald test and corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini and Hochberg method.

We next investigated if the genes regulated by microbes in the kidney are kidney specific or if these genes are globally regulated by microbes. We found that the majority of the genes that changed with microbial status were specific to the kidney (vs. the liver or large intestine, 80% of DEGs were specific to the kidney in females and 85% of DEGs in males). In fact, only six genes changed in all three tissues in females [period 2 (Per2), joining chain of multimeric IgA and IgM (Jchain), lipoprotein lipase (Lpl), exostosin-like glycosyltransferase 1 (Extl1), metallothionein 1 (Mt1), and metallothionein 2 (Mt2)] and only four genes changed in all three tissues in males [period 1 (Per1), forkhead box O3 (Foxo3), Mt1, and Mt2] (Fig. 4, E and J). Mt1, Mt2, and Per2 were upregulated in GF females compared with Conv females. In contrast, Lpl, Extl1, and Jchain were decreased in GF females versus Conv. The four genes that changed across tissues in males were all significantly upregulated in GF compared with Conv.

Microbes Alter Renal Gene Expression in a Sexually Dimorphic Manner

We wondered whether microbiota regulate the same genes in males and females. In the kidney, we found that of the 578 DEGs identified in males (Conv vs. GF) and 340 DEGs identified in females, 73 genes were differentially expressed in both sexes (Fig. 4K). The liver and large intestine exhibited similar sexually dimorphic trends, with the majority of DEGs (90% in the liver and 89% in the large intestine) changing in either males or females but not in both (Fig. 4, L and M). These analyses demonstrate that the influence of gut microbiota on gene expression is sex specific.

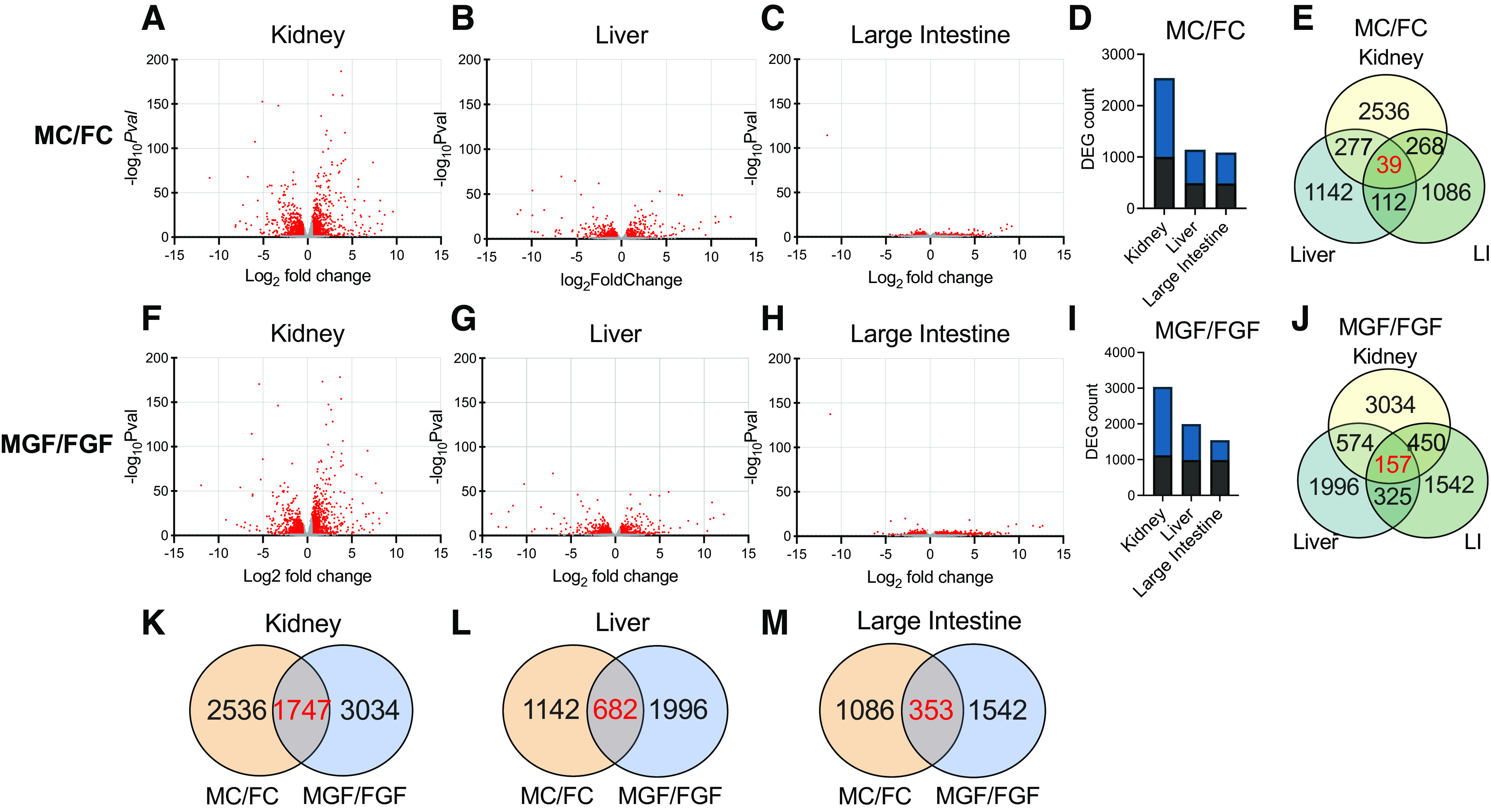

To further explore the role of sex, male-female comparisons are shown in Fig. 5. Interestingly, the bulk of the genes that were altered based on sex (males vs. females, irrespective of microbiota status) occurred in the kidney (Fig. 5, D and I). A subset of the genes that were differentially regulated by sex was dependent on the gut microbiota (of the 2,536 DEGs in male vs. female Conv mice, only 1,747 DEGs were shared by male vs. female GF mice; Fig. 5K). Intriguingly, there were over 1,000 genes that were differentially regulated by sex in GF kidneys that were not regulated in Conv kidneys (Fig. 5K); this may represent sex-specific compensatory changes that occur in the absence of gut microbial signals.

Figure 5.

Volcano plot analysis comparing male vs. female data. Data are shown here separated by both tissue and sex. The total number of genes identified was 14,949 (kidney), 13,202 (liver), and 15,736 (large intestine). FC, female conventionalized; FGF, female germ free; MC, male conventionalized; MGF, male germ free. Volcano plots illustrating differential expression calculated by sex (male:female) for both conventionalized (A–E) and germ-free (F–J) mice. Genes with significant changes [−log10 P value (−logPval) ≥ 1.3] are shown in red; genes without significant changes (−log10Pval ≤ 1.29) are shown in gray. Total numbers of male:female differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in each tissue for both conventionalized (D) and germ-free (I) mice. DEGs were defined as follows: base mean ≥ 15, |log2 fold change| ≥ 0.5, P ≤ 0.05. Black bars represent the number of genes that were upregulated; blue bars represent the number of genes that were downregulated. E and J: Venn diagrams illustrating DEGs differentially regulated by sex that were in common between different organs in conventionalized and germ-free mice. E: 39 genes were differentially regulated in the kidney, liver, and large intestine in conventionalized mice. J: 157 genes were shared in germ-free animals across all three tissues. K–M: Venn diagrams illustrating DEGs in common between conventionalized (male vs. female) and germ-free (male vs. female) animals for each organ. K: 31% of male:female DEGs in the kidney were altered in both conventionalized and germ-free animals. L: 22% of male:female genes in the liver were differentially expressed based on microbes. M: <15% of male:female genes in the large intestine were differentially regulated in both conventionalized vs. germ-free mice, emphasizing that the effect of microbes on gene expression is highly sexually dimorphic. Differential expression was analyzed using separate pairwise comparisons. All P values were attained using the Wald test and corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini and Hochberg method.

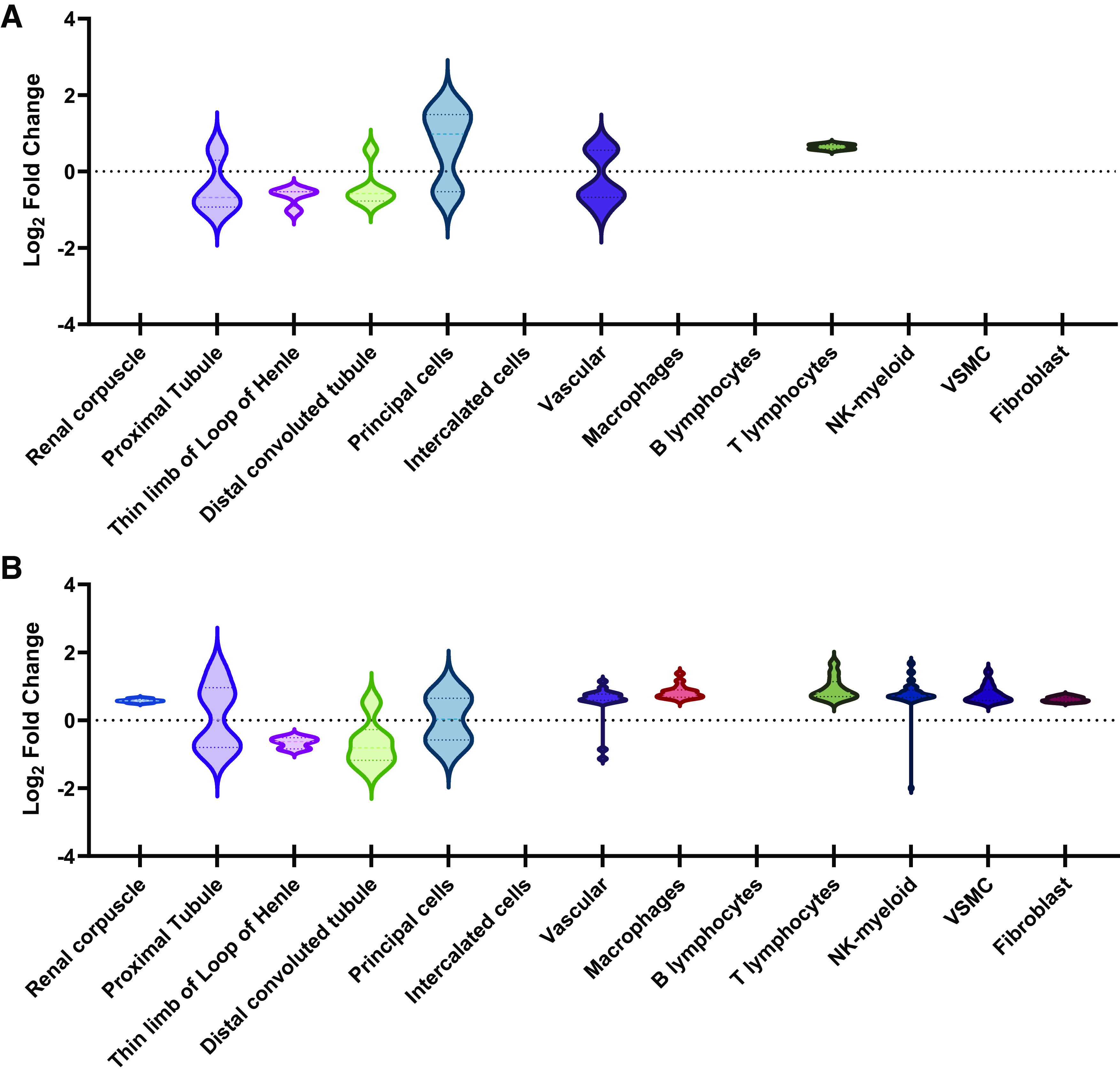

Differential Gene Expression in Renal Cell Types

Next, we compared our data with the data from Ransick et al. (29), who performed unbiased scRNA-Seq on kidneys from two female and two male mice. In this study, “marker genes” of each renal cell type were identified based on the top 50 DEGs within each cluster. By comparing our kidney DEGs (Conv vs. GF) with the genes identified as marker genes in the study by Ransick et al., we were able to match 33 DEGs from our female data to at least one cell type (Supplemental Table S1) and 176 DEGs from our male data to at least one cell type (Supplemental Table S2). We found that in females, the clusters with the largest magnitude of log2 fold changes belonged to principal cells (log2 fold change between +1.73 and −0.54), vascular cells (log2 fold change between +0.66 and −1.03), and the proximal tubule (log2 fold change between +0.57 and −0.96) (Fig. 6A). In males, these clusters were natural killer cell differentiation by myeloid lineage (log2 fold change between +1.69 and −1.99), the proximal tubule (log2 fold change between +1.45 and −0.96), and vascular cells (log2 fold change between +1.15 and −1.14) (Fig. 6B). This implies that there may be commonality in the cell types being regulated by microbes between male and females, even when the genes themselves differ between sexes. Altogether, these data suggest that microbes regulate specific genes within various cell types in the kidney.

Figure 6.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in conventionalized (Conv) vs. germ-free (GF) mice across renal cell types. Using data from Ransick et al. (29), single-cell transcriptomics of the mouse kidney revealed potential sex differences in gene expression. All DEGs characteristic of a particular renal cell type were sorted under that cell type. Data are displayed as violin plots that show the distribution in log2 fold changes for DEGs assigned to each cluster. We separately analyzed our data from females, to which 33 DEGs were assigned (A), and males, to which 176 DEGs were assigned (B). Clusters without a violin plot indicate cell types with either 0 DEGs (females: renal corpuscle, intercalated cells, and B lymphocytes; males: intercalated cells and B lymphocytes) or 1 DEG [females: macrophages, natural killer cell differentiation by myeloid lineage (NK-myeloid), vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC), and fibroblasts].

DISCUSSION

Although recent studies have explored the gut-kidney axis in health and disease (15, 30, 31), the role of host microbiota in renal gene regulation has not previously been examined. Here, we report that renal gene expression is altered by host microbiota and that these changes are dependent on sex. Moreover, the majority of the genes regulated by microbes in kidney are not similarly regulated in the liver or large intestine, suggesting that host microbiota modulate gene expression in a tissue-dependent manner.

In our study, we conventionalized male and female GF mice using the same fecal slurry (made from a mix of male and female donors) and found that Conv males had a higher abundance of Verrucomicrobia than did Conv females. Previous data on sex differences in Verrucomicrobia are mixed: one study reported that female C57Bl/6 mice, treated with a high-fat diet, had a lower abundance of Verrucomicrobia compared with males (32), but another study found that female C57Bl/6N mice, fed a standard diet, had a higher relative abundance of Verrucomicrobia compared with males (33). Intriguingly, sex differences in Verrucomicrobia abundance in this latter study were observed in wild-type mice, but differences were abolished in mutant mice (e.g., farnesoid X receptor knockout) (33). This suggests that genotype, along with sex, may influence the growth of this phylum. Indeed, it may well be that Verrucomicrobia abundance depends on additional factors (animal strain, food, environment, etc.) that vary between different animal facilities. Although we cannot rule out a role for sex differences in Verrucomicrobia to contribute to changes in host gene expression, this is unlikely to be solely responsible. Of note, the statistically significant difference in Verrucomicrobia was also observed down to the species level, Akkermansia muciniphila (P = 0.005, t test); however, this change was not significant at any level beyond the phylum level when using an adjusted P value (false discovery rate = 0.15 at the class level). Similar to Verrucomicrobia, A. muciniphila has also been associated with sex differences. In an unbiased, population-based human study, Sinha et al. (34) observed differences in the microbiome profile between males and females. They found that after controlling for various factors (e.g., medications, smoking, and diet), females had a higher abundance of A. muciniphila compared with males and concluded that this species was highly associated with sex (false discovery rate = 0.002) (34). In another report, it was observed that pretreatment with A. muciniphila protected against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute kidney in mice (35). Taken together, these studies imply that this strain is physiologically important and that it should be studied with sex taken into consideration.

We also report here that the influence of the microbiota is tissue specific. Previous studies have identified a relationship between microbiome and host gene expression in the liver and large intestine (36, 37). However, we found that most genes regulated in the kidney were not regulated in the additional tissues sequenced. Using Gene Ontology Panther pathway analysis, we found that the top 100 female DEGs (Conv vs. GF) unique to the kidney mapped to anion transport, regulation of neurogenesis, and rhythmic processes. For males, the top renal-specific pathways were mononuclear cell differentiation, negative regulation of the immune system process, and positive regulation of response to external stimuli.

Our investigation revealed that only a small fraction of genes in the kidney, liver, and large intestine were similarly regulated in both sexes. In agreement with this, previous studies have shown that the influence of microbiota on the host is often sex specific (20, 38, 39). For example, Weger et al. (20) reported that gut microbiota are required for sex-specific diurnal rhythms in gene expression. Similarly, a study using the nonobese diabetic mouse model (in which females develop type 1 diabetes at higher incidences than males) found that the sex difference in diabetes incidence is absent in GF animals (40). By comparing results from our bulk RNA-Seq to scRNA-Seq data from Ransick et al. (29), we mapped DEGs (Conv vs. GF) to specific renal cell types. In addition to the sex bias that Ransick et al. previously reported in the proximal tubule, we find that these sex differences are likely influenced by microbes.

Finally, our study revealed a small subset of genes that were commonly regulated across the three tissues we examined: Per1 (in males), Per2 (in females), and Mt1 and Mt2 (in both males and females). Previous studies have reported a sex-specific influence of Per1 on renal physiology. For example, C57Bl/6 global Per1 knockouts challenged with high-salt and mineralocorticoids decreased endothelin-1 production in male knockouts but increased endothelin-1 production in female knockouts [compared with wild-type controls (41)]. Endothelin-1 is an important regulator of kidney function and blood pressure; thus, understanding the factors poised to influence Per1 is paramount in renal health and diseases.

Both Per1 and Per2 are associated with circadian rhythm; of note, additional genes related to circadian rhythm were found to be altered in Conv and GF mice, including cryptochrome circadian regulator 1 (Cry1), cryptochrome circadian regulator 2 (Cry2), circadian associated repressor of transcription (Ciart), and basic helix-loop-helix ARNT like 1 (Bmal1) (see Supplemental Tables S4 and S5). In the kidney, Cry1 and Cry2 were significantly upregulated in both male and female GF mice compared with Conv. Furthermore, female GF mice exhibited increased renal expression (compared with male GF mice) in Cry1, Cry2, and Ciart. In the liver, Ciart was upregulated in GF males versus Conv males (log2 fold change = +4.03) and was not significantly changed in GF females versus Conv females (log2 fold change = −0.69, P = 0.45). Finally, Bmal1 was significantly upregulated in the livers of males (Conv vs. GF) but not in the kidney. Previous studies have also highlighted the fact that GF mice have alterations in circadian biology genes (20). It may be that cyclical production of microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids [which inhibit histone deacetylase 1 activity (42)] may modulate the expression of circadian genes.

Furthermore, we report that Mt1 and Mt2 were significantly increased in the absence of gut microbiota in both sexes and in all three tissues. This is consistent with a report showing that Mt2 was upregulated in the colon of GF mice using microarray [sex was not specified (43)] and that both Mt1 and Mt2 increased in the duodenum and colon of GF mice (44). A notable difference between the Breton et al. study and our study is that the former only examined females. We found that these changes were more pronounced in males (log2 fold changes for GF:Conv in Mt1 = +1.1 and Mt2 = +1.4, respectively) compared with females (Mt1 = +0.6 and Mt2 = +0.8). In future work, it will be important to explore mechanisms that underlie the increased expression of MTs in germ-free mice. One possibility is that gut bacterial metabolites modulate metal ion concentrations in the host and that in the absence of this regulation, the host produces more MTs to maintain metal homeostasis (45). Another possibility is that the absence of gut microbes alters the immune response in the host, leading to an upregulation of MT expression (46). We intend to leverage our findings in this study to further investigate both possibilities.

Our study has several limitations. One limitation of this study is sample size. Each experimental group (male Conv, male GF, female Conv, and female GF) contained n = 3–4 samples; a larger n value would allow for more robust conclusions. In addition, all samples were collected during the light cycle; given the intriguing changes in Per1 and Per2, it would be useful going forward to examine samples collected during the dark cycle as well. Finally, this study sought to explore whether gut microbes regulate renal gene expression; however, it is important to explore whether changes at the transcriptional level are observed at the protein level. Thus, our interpretations are limited without proteomic data in parallel.

In summary, we found that host microbiota modulate renal gene expression and that this occurs in a sex-dependent and tissue-specific manner. Although host-microbiome interactions continue to be an evolving theme in physiology, microbiome-gene interactions remain largely unexplored. The microbial genome contains more genes than the human genome by ∼100-fold (39). To this end, the gut microbiota have become increasingly recognized as the “second human genome” because their coding potential supersedes the coding potential of the human genome (39). Thus, in future studies, it will be important to expand on our findings to understand the interaction between the gut microbiome and host transcriptomics, which can provide powerful insight into the physiological processes required to maintain host health.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Tables S1 and S2: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21705977.v4.

Supplemental Table S3: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22335232.v1.

Supplemental Table S4: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22335247.v1.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship DGE-1746891 (to B.N.M.), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Diabetic Complications Consortium (RRID:SCR_001415, www.diacomp.org), and NIDDK Grants DK076169 and DK115255 (to J.L.P.) and R56DK107726 (to J.L.P.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

Jennifer Pluznick is an editor of American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology and was not involved and did not have access to information regarding the peer-review process or final disposition of this article. An alternate editor oversaw the peer-review and decision-making process for this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.M. and J.L.P. conceived and designed research; B.M. analyzed data; B.M. and J.L.P. interpreted results of experiments; B.M. drafted manuscript; B.M. and J.L.P. edited and revised manuscript; B.M. and J.L.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the current and past members of the J. L. Pluznick laboratory for their insightful discussions. We also thank Dr. Hua Ding and the animal care staff of the Johns Hopkins University Germ-Free facility, the Johns Hopkins University Single Cell and Transcriptomics Core for library prep and sequencing, Dr. Liliana Florea and Dr. Corina Antonescu for the help with the RNA-Seq analysis, and finally Dr. James Robert White (Resphera Biosciences) for microbial sequencing analysis. The graphical abstract was created with BioRender.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Thursby E, Juge N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem J 474: 1823–1836, 2017. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wilck N, Matus MG, Kearney SM, Olesen SW, Forslund K, Bartolomaeus H, et al. Salt-responsive gut commensal modulates TH17 axis and disease. Nature 551: 585–589, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nature24628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang T, Santisteban MM, Rodriguez V, Li E, Ahmari N, Carvajal JM, Zadeh M, Gong M, Qi Y, Zubcevic J, Sahay B, Pepine CJ, Raizada MK, Mohamadzadeh M. Gut dysbiosis is linked to hypertension. Hypertension 65: 1331–1340, 2015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li Y, Su X, Gao Y, Lv C, Gao Z, Liu Y, Wang Y, Li S, Wang Z. The potential role of the gut microbiota in modulating renal function in experimental diabetic nephropathy murine models established in same environment. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1866: 165764, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen YY, Chen DQ, Chen L, Liu JR, Vaziri ND, Guo Y, Zhao YY. Microbiome-metabolome reveals the contribution of gut-kidney axis on kidney disease. J Transl Med 17: 5, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1756-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ramezani A, Raj DS. The gut microbiome, kidney disease, and targeted interventions. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 657–670, 2014. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lau WL, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Vaziri ND. The gut as a source of inflammation in chronic kidney disease. Nephron 130: 92–98, 2015. doi: 10.1159/000381990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hauser AB, Stinghen AE, Gonçalves SM, Bucharles S, Pecoits-Filho R. A gut feeling on endotoxemia: causes and consequences in chronic kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract 118: c165–c172, 2011. doi: 10.1159/000321438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li J, Zhao F, Wang Y, Chen J, Tao J, Tian G, Wu S, Liu W, Cui Q, Geng B, Zhang W, Weldon R, Auguste K, Yang L, Liu X, Chen L, Yang X, Zhu B, Cai J. Gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to the development of hypertension. Microbiome 5: 14, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0222-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mell B, Jala VR, Mathew AV, Byun J, Waghulde H, Zhang Y, Haribabu B, Vijay-Kumar M, Pennathur S, Joe B. Evidence for a link between gut microbiota and hypertension in the Dahl rat. Physiol Genomics 47: 187–197, 2015. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00136.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peti-Peterdi J, Kishore BK, Pluznick JL. Regulation of vascular and renal function by metabolite receptors. Annu Rev Physiol 78: 391–414, 2016. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pluznick JL. Gut microbes and host physiology: what happens when you host billions of guests? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 5: 91, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rabb H, Pluznick J, Noel S. The microbiome and acute kidney injury. Nephron 140: 120–123, 2018. doi: 10.1159/000490392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Raizada MK, Joe B, Bryan NS, Chang EB, Dewhirst FE, Borisy GG, Galis ZS, Henderson W, Jose PA, Ketchum CJ, Lampe JW, Pepine CJ, Pluznick JL, Raj D, Seals DR, Gioscia-Ryan RA, Tang WHW, Oh YS. Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group on the role of microbiota in blood pressure regulation: current status and future directions. Hypertension 70: 479–485, 2017. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pluznick JL. The gut microbiota in kidney disease. Science 369: 1426–1427, 2020. doi: 10.1126/science.abd8344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Usami M, Miyoshi M, Yamashita H. Gut microbiota and host metabolism in liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 21: 11597–11608, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i41.11597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tremaroli V, Bäckhed F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature 489: 242–249, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nature11552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pluznick JL, Protzko RJ, Gevorgyan H, Peterlin Z, Sipos A, Han J, Brunet I, Wan LX, Rey F, Wang T, Firestein SJ, Yanagisawa M, Gordon JI, Eichmann A, Peti-Peterdi J, Caplan MJ. Olfactory receptor responding to gut microbiota-derived signals plays a role in renin secretion and blood pressure regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 4410–4415, 2013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215927110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Richards AL, Muehlbauer AL, Alazizi A, Burns MB, Findley A, Messina F, Gould TJ, Cascardo C, Pique-Regi R, Blekhman R, Luca F. Gut microbiota has a widespread and modifiable effect on host gene regulation. mSystems 4: e00323-18, 2019. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00323-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weger BD, Gobet C, Yeung J, Martin E, Jimenez S, Betrisey B, Foata F, Berger B, Balvay A, Foussier A, Charpagne A, Boizet-Bonhoure B, Chou CJ, Naef F, Gachon F. The mouse microbiome is required for sex-specific diurnal rhythms of gene expression and metabolism. Cell Metab 29: 362–382.e8, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sun J, Zhong H, Du L, Li X, Ding Y, Cao H, Liu Z, Ge L. Gene expression profiles of germ-free and conventional piglets from the same litter. Sci Rep 8: 10745, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29093-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30: 2114–2120, 2014. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Magoc T, Salzberg SL. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27: 2957–2963, 2011. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Peña AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7: 335–336, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26: 2460–2461, 2010. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Drewes JL, White JR, Dejea CM, Fathi P, Iyadorai T, Vadivelu J, Roslani AC, Wick EC, Mongodin EF, Loke MF, Thulasi K, Gan HM, Goh KL, Chong HY, Kumar S, Wanyiri JW, Sears CL. High-resolution bacterial 16S rRNA gene profile meta-analysis and biofilm status reveal common colorectal cancer consortia. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 3: 34, 2017. [Erratum in NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 5: 2, 2019]. doi: 10.1038/s41522-017-0040-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15: 550, 2014. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aleksandrova K, Romero-Mosquera B, Hernandez V. Diet, gut microbiome and epigenetics: emerging links with inflammatory bowel diseases and prospects for management and prevention. Nutrients 9: 962, 2017. doi: 10.3390/nu9090962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ransick A, Lindström NO, Liu J, Zhu Q, Guo JJ, Alvarado GF, Kim AD, Black HG, Kim J, McMahon AP. Single-cell profiling reveals sex, lineage, and regional diversity in the mouse kidney. Dev Cell 51: 399–413.e7, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li Y, Zhu B, Yang C, Miao L. Commentary: focus on the gut-kidney axis in health and disease. Front Med (Lausanne) 8: 669561, 2021. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.669561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Poll BG, Cheema MU, Pluznick JL. Gut microbial metabolites and blood pressure regulation: focus on SCFAs and TMAO. Physiology (Bethesda) 35: 275–284, 2020. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00004.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bridgewater LC, Zhang C, Wu Y, Hu W, Zhang Q, Wang J, Li S, Zhao L. Gender-based differences in host behavior and gut microbiota composition in response to high fat diet and stress in a mouse model. Sci Rep 7: 10776, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11069-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sheng L, Jena PK, Liu HX, Kalanetra KM, Gonzalez FJ, French SW, Krishnan VV, Mills DA, Wan YY. Gender differences in bile acids and microbiota in relationship with gender dissimilarity in steatosis induced by diet and FXR inactivation. Sci Rep 7: 1748, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01576-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sinha T, Vich Vila A, Garmaeva S, Jankipersadsing SA, Imhann F, Collij V, Bonder MJ, Jiang X, Gurry T, Alm EJ, D'Amato M, Weersma RK, Scherjon S, Wijmenga C, Fu J, Kurilshikov A, Zhernakova A. Analysis of 1135 gut metagenomes identifies sex-specific resistome profiles. Gut Microbes 10: 358–366, 2019. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2018.1528822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shi J, Wang F, Tang L, Li Z, Yu M, Bai Y, Weng Z, Sheng M, He W, Chen Y. Akkermansia muciniphila attenuates LPS-induced acute kidney injury by inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB pathway. FEMS Microbiol Lett 369: fnac103, 2022. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnac103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Selwyn FP, Cheng SL, Klaassen CD, Cui JY. Regulation of hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes in germ-free mice by conventionalization and probiotics. Drug Metab Dispos 44: 262–274, 2016. doi: 10.1124/dmd.115.067504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fu ZD, Selwyn FP, Cui JY, Klaassen CD. RNA-Seq profiling of intestinal expression of xenobiotic processing genes in germ-free mice. Drug Metab Dispos 45: 1225–1238, 2017. doi: 10.1124/dmd.117.077313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cheema MU, Pluznick JL. Gut microbiota plays a central role to modulate the plasma and fecal metabolomes in response to angiotensin II. Hypertension 74: 184–193, 2019. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nichols RG, Davenport ER. The relationship between the gut microbiome and host gene expression: a review. Hum Genet 140: 747–760, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s00439-020-02237-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Markle JG, Frank DN, Mortin-Toth S, Robertson CE, Feazel LM, Rolle-Kampczyk U, von Bergen M, McCoy KD, Macpherson AJ, Danska JS. Sex differences in the gut microbiome drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science 339: 1084–1088, 2013. doi: 10.1126/science.1233521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Douma LG, Crislip GR, Cheng KY, Barral D, Masten S, Holzworth M, Roig E, Glasford K, Beguiristain K, Li W, Bratanatawira P, Lynch IJ, Cain BD, Wingo CS, Gumz ML. Knockout of the circadian clock protein PER1 results in sex-dependent alterations of ET-1 production in mice in response to a high-salt diet plus mineralocorticoid treatment. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 98: 579–586, 2020. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2019-0688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Boffa LC, Vidali G, Mann RS, Allfrey VG. Suppression of histone deacetylation in vivo and in vitro by sodium butyrate. J Biol Chem 253: 3364–3366, 1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cresci GA, Thangaraju M, Mellinger JD, Liu K, Ganapathy V. Colonic gene expression in conventional and germ-free mice with a focus on the butyrate receptor GPR109A and the butyrate transporter SLC5A8. J Gastrointest Surg 14: 449–461, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Breton J, Daniel C, Dewulf J, Pothion S, Froux N, Sauty M, Thomas P, Pot B, Foligné B. Gut microbiota limits heavy metals burden caused by chronic oral exposure. Toxicol Lett 222: 132–138, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Duan H, Yu L, Tian F, Zhai Q, Fan L, Chen W. Gut microbiota: a target for heavy metal toxicity and a probiotic protective strategy. Sci Total Environ 742: 140429, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Subramanian Vignesh K, Deepe GS Jr.. Metallothioneins: emerging modulators in immunity and infection. Int J Mol Sci 18: 2197, 2017. doi: 10.3390/ijms18102197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Tables S1 and S2: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21705977.v4.

Supplemental Table S3: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22335232.v1.

Supplemental Table S4: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22335247.v1.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.