Abstract

Patients expect high-quality surgical care and increasingly are looking for ways to assess the quality of the surgeon they are seeing, but quality measurement is often more complicated than one might expect. Measurement of individual surgeon quality in a manner that allows for comparison among surgeons is particularly difficult. While the concept of measuring individual surgeon quality has a long history, technology now allows for new and innovative ways to measure and achieve surgical excellence. However, some recent efforts to make surgeon-level quality data publicly available have highlighted the challenges of this work. Through this chapter, the reader will be introduced to a brief history of surgical quality measurement, learn about the current state of quality measurement, and get a glimpse into what the future holds.

Keywords: surgical quality, technical skills, video-based assessment, surgical quality

A Brief History of Current Measures of Quality

Considered a pioneer of outcomes research, Dr. Ernest Codman began to track his patient outcomes in the 1910s while at the Massachusetts General Hospital. He logged his data on “End Result Cards” and challenged others to do the same. He felt that by measuring his outcomes he could demonstrate superior results of his techniques. Although he collected his data on paper index cards, many of the data points he collected are similar to the data collected today. 1 Although originally shunned for his idea, he is now credited as a founder of surgical quality measurement, and he became an integral part of the founding of the American College of Surgeons. By 1917, his system of tracking his patients' “end results” had been adopted by the college as they formed their hospital standardization program. 2 Indeed, the measurement and reporting of outcomes and quality are not new concepts to surgeons, and Dr. Codman's work was the starting point for what would become the standard of care in modern medicine.

Over the next few decades, the idea of assessing quality in health care continued to grow and became more mainstream. The measurement of quality took a giant leap forward in 1966 when Avedis Donabedian proffered a three-sided model which would become the foundation of quality measurement thinking in health care. 3 His “structure–process–outcome” model served as the basis for the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations' new accreditation guidelines in the late 1980s. Over time, there has been continued evolution of our approach to quality measurement, with the establishment of programs like the Surgical Care Improvement Project, National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (NSQIP), Surgical Clinical Outcomes Assessment Program, and many others. A notable shift in quality assessment came in the 1990s when increasing consumer demand for transparency and publicly available information started leading organizations to publish their quality data. New York State published the first-of-its-kind “Cardiac Surgery Reporting System,” which provided patients with surgeon-specific mortality rates. 4 Many states followed suit, and eventually, many researchers began investigating ways to accurately assess and report individual surgeon performance. 5 6 7 Much of the quality reporting outside of the cardiac surgery data was focused on hospital-level quality, and measurement of individual surgeon performance proved to be more daunting. Although these attempts to reliably measure and compare surgeon quality were met with little success, public interest has not wavered, and investigative journalists at ProPublica have even published their own surgeon-level quality reports for public consumption. It is hard to miss that in recent years, a key component in the push for quality improvement has been the evaluation of surgeon performance. 8

However, in the absence of a defined, reliable method of measuring individual surgeon quality, other variables often get used as a proxy for quality. For example, the operative volume has frequently been touted as a useful yardstick in the measurement of surgical quality even though there is evidence both for and against this relationship, while questions remain about how much volume is necessary or sufficient. 9 10 For example, Porter et al demonstrated that surgeons with a larger volume of similar cases, or those with subspecialty training in colorectal surgery, had better oncologic outcomes for their patients undergoing surgical resection for rectal cancer. 11 But previously, in a group of nearly 1,000 patients undergoing surgery for primary colorectal cancer, Parry et al found no association between a surgeon's operative volume and the patient outcomes. 12 So, while there are many variables which can be tempting to consider when studying quality among colorectal surgeons, it is clear that one measure alone should not be used. Further, how accurately can we control for patient-level factors—what if a technically skilled surgeon is referred to the sickest patients? In this era of increasing transparency, reporting, and a growing public interest in these data, the question of “what can we measure” becomes “what should we measure,” and what metrics (if any) can accurately and reliably be used to demonstrate differences in surgeon level performance and quality. Further, to what degree should we be reporting differences in surgeon-level quality publicly versus using the data internally to stimulate improvement of the profession?

Pitfalls of Current Methods of Quality Measurement

National registries can be extremely useful in assessing quality differences among hospitals, but they often fall short when used to compare individual surgeon performance. In their 2018 paper, Quinn et al used NSQIP data to analyze 2,724 surgeons performing 123,000 cases to create surgeon-level comparative assessments. 8 They found that despite their large amounts of data, they were unable to detect surgeon-level differences using these risk-adjusted data with high enough reliability to support public reporting. They attributed this in part to the large case numbers required to accurately detect differences between physician performance. In general, differences between surgeons on standard quality measures such as mortality or surgical site infection are low relative to the absolute rate of these complications. Hence, several studies have demonstrated that relatively large case volumes are required to accurately identify outliers when comparing surgeons against one another. In a 2015 study, Shih et al found that to reach an acceptable level of reliability when comparing surgeon-specific complication rates after segmental colectomy, surgeons would need to have performed 168 of these procedures over a 3-year period. 6 There were 345 surgeons in their cohort, and only one was noted to have had that case volume. Given the low variation between surgeons on these measures, there is simply too much statistical noise when we try to evaluate individual surgeon performance using the outcomes data collected in these registries.

Another shortcoming of many of our large data registries is their timeliness. The data collection process leads to a lag time ranging from months to years. 13 This is inherently problematic. Adding this collection delay to the time necessary to analyze, and then report the data, we could be making inferences about a surgeon's current “quality,” using the information on their performance more than a year ago—not taking into account any new skill acquisition, experience gains, or changes in their clinical practice that may have occurred during that time. Therefore, the current process used in our large national data registries is not directly replicable and cannot be easily used to assess individual surgeon quality.

In addition to our quality registries, there have been attempts to create “surgeon scorecards” using administrative data records. ProPublica's online scorecard tool shows a surgeon's “adjusted complication rates,” which is a proprietary outcome measure that includes readmission or mortality within 30 days of an operation among other components. However, their proprietary adjusted complication rate has been widely criticized as inaccurate, biased, and incomplete. A critique of the scorecard broke down the many reasons why the scorecard presented results as unreliable and invalid when comparing surgeons against one another. 14 One critical shortcoming is the use of administrative data which do not include the clinical granularity and accuracy necessary because they are collected for the purposes of billing and not quality measurement. In addition, their adjusted complication rates wildly misrepresented actual complication rates, and they ranked the surgical outcomes of several clinicians who were not surgeons. These issues, among others, have largely invalidated their methodology. Ban and colleagues found that ProPublica's specifications would “exclude 82% of cases, miss 84% of postoperative complications, and correlated poorly with well-established postoperative outcomes.” 15 Even for very common cases, performed across the spectrum of surgeons and hospital environments, their data validity can be questioned. Take, for example, a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Jaffe and team demonstrated that the case volumes required to detect a surgeon whose complication rate after laparoscopic cholecystectomy was 50% higher than the accepted average was greater than 600 cases. No surgeon in the entire database had numbers that approached those case volumes. 16

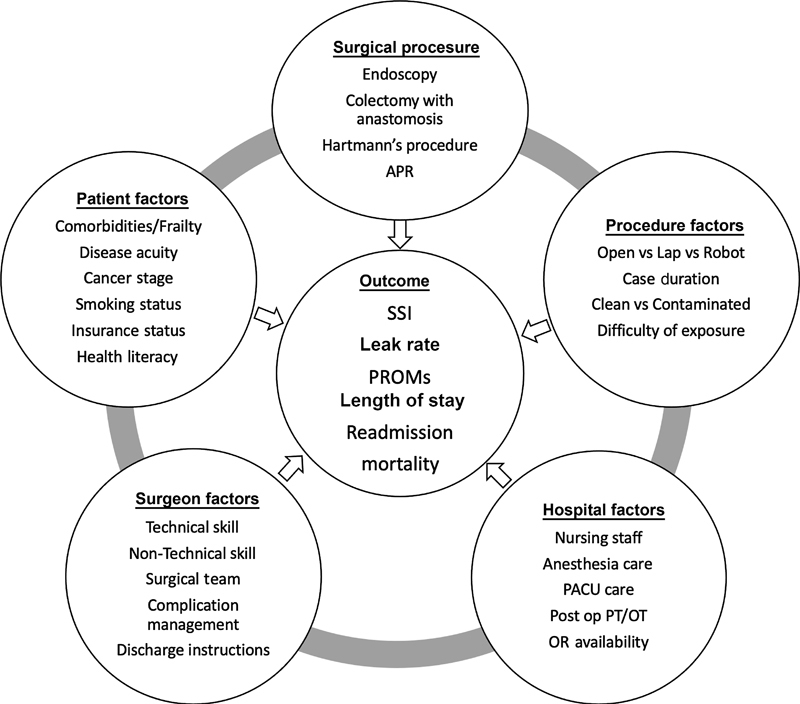

Many factors play a role in determining a patient's outcome after a surgical event ( Fig. 1 ). Patient factors, hospital factors, surgeon factors, the type of procedure, and procedural factors all have an effect. Without controlling for these, we open ourselves to statistical misinterpretation when assessing and comparing individual surgeon quality. Variables within surgical specialties, or those specific to certain types of procedures, must also be considered if we are to accurately depict surgical quality. Within colorectal surgery, based simply on the nature of procedures performed, patients are exposed to higher rates of complications such as surgical site infection after bowel resection or urinary tract infection after complex pelvic dissection. 17

Fig. 1.

Factors that influence patient outcomes.

Apart from the obvious consequences of mischaracterizing to the public the quality of care that individual surgeons provide, one must also consider longer-term effects of this reporting. For fear of how this may affect their publicly available ratings, studies have shown that surgeons may be less willing to perform necessary operations on patients that may carry higher clinical risk 18 or to involve junior surgical trainees in their cases. 19 In their look at using clinical registries to profile individual surgeons, Hall's group concluded that “No portrayal of individual medical provider quality should be accepted without consideration of modeling rationale and, critically, reliability.” 7 There is not yet a perfect system that balances all the issues discussed while considering the many variables involved in taking care of a colorectal surgical patient. Therefore, we do not yet have a quality measurement tool that can reliably distinguish differences in a surgeon's ability to provide quality care for their patient.

Better Measurements of Surgeon-Level Quality

Given the shortcomings of our current measures of surgeon-level quality, efforts have shifted to new novel methods of surgeon quality measurement. In their writing, which called into question the usefulness of current-day surgical scorecards, Engelhardt et al offered some suggestions for the future direction of this work. 13 One suggestion is the use of video-based assessments. As laparoscopic and robotic surgery becomes more ubiquitous, so does the ability to record and subsequently analyze surgical performance. As we will discuss later, groups have already begun looking into this approach and have demonstrated that, at least subjectively, surgical skills can be effectively evaluated using video in this way. 20 21 What is yet to be determined is the generalizability of this type of assessment across varying specialties and procedures, what interventions can be done with this information, and how these data might affect the ability to improve a surgeon's future performance and resulting outcomes. There are many potential avenues for the use of video-based assessments. These range from initial surgical training and recertification to skill refinement and ongoing credentialing to remediation and anonymous feedback. In the United Kingdom, programs have been developed where video-based assessment was used to determine if a surgeon was sufficiently skilled to be certified to independently perform laparoscopic colorectal surgery. 22 As with any tool, there are certain limitations. For example, using sole assessment of the video recording potentially ignores other variables that the surgeon may be considering at the time of the operation, such as hemodynamics or the input of other members of the operating room team. 23 As we learn more about the usability of video as a valid tool, the future study can be done on its effectiveness in the assessment of both technical and nontechnical surgical skills.

Another alternative to classic quality metrics is patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Engelhardt et al hypothesized that as we continue to optimize clinical processes, the differences in traditional patient outcomes between surgeons will get smaller making surgeon-level comparisons even more difficult. 13 PROs, however, may be a new area of outcomes research that can highlight differences not currently captured by classic outcome measures. These scaled scores of patient function can reflect both pre- and postoperative status and patient population changes in PROs through surgery could help us understand the value we bring to a population. Although this may be a promising tool, it is rife with challenges including standardization, integration into practice, and difficulty in risk-adjusting between patients. 24

Technical Skills as a Factor in Surgeon-Level Quality

Even with no supporting evidence, most would assume that an individual surgeon's technical skill has a direct correlation to their patients' outcomes and, therefore, to the quality of care that the surgeon provides. This is also likely to be the perception of the nonmedical public. Yet, all surgeons must meet minimum competencies to graduate from residency, so how much impact does the variation in technical skills among practicing surgeons actually have on the overall quality of care their patient receives? Until relatively recently, a very little study had been done on the assessment of surgical skills in the practicing surgeon, let alone the association between skill and a patient's outcome. 25 Most of the work had come from the world of surgical training and focused on measuring the skill of trainees. 26 27 In a first-of-its-kind study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2013, a group of surgeons in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative investigated the link between a surgeon's technical skill and their patient's outcomes. 20 They used a video review of the recorded laparoscopic gastric bypass procedure as performed by 20 different surgeons. The videos were anonymously reviewed and scored by 10 other surgeon peers using a prescribed scoring scale, and an aggregate score was calculated. They then examined the association between this technical skill score and postoperative complication rate, readmission rates, and rates of reoperation. Not only did they demonstrate that there was a range of skill levels between practicing surgeons, but they showed that technical skills could be correlated with clinical outcomes. Patients treated by the “low-skilled” surgeons had higher rates of complication, reoperation, readmission, and even death. They were also able to demonstrate that there was a strong relationship between a surgeon's volume of cases and their technical skills and that their skill level was not related to where they practiced, how long they had been in practice, or whether they had completed a fellowship. Although the study had several limitations, similar results were produced by Stulberg and team in a 2020 study which eliminated some of the limitations in previous works. 21 Instead of using gastric bypass as their procedure of study, an operation with relatively low complication rates, and one that is frequently performed at specialized centers by surgeons with a specialized practice in the field, they examined a much more common procedure, performed across the surgical spectrum—the laparoscopic colectomy. They were also able to link technical scores during a colectomy, not only to colectomy outcomes, but to that surgeon's outcomes across their repertoire of procedures. This study looked at both colorectal and general surgeons, and along with peer review by colleagues, the submitted videos were each also evaluated by two expert board-certified colorectal surgeons. The group asserted that the differences in technical skills alone between surgeons could be responsible for 26% of the variation in complication rates. When complications were separated out into skill-related (postoperative bleeding, wound dehiscence, anastomotic leak, etc.) and skill-unrelated (deep venous thrombosis, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolus, etc.) outcomes, technical skill score was strongly associated with the skill-related outcomes and not skill-unrelated outcomes. Subsequent follow-up by that same group linked technical skill score to the national cancer database and demonstrated that the technical skill score from a single laparoscopic colectomy was associated with long-term cancer survival for that surgeon's patient population. 28 Even with the exclusion of early postoperative deaths, patients who had been operated on by a surgeon with a higher level of technical skill had improved long-term survival. More work needs to be done to further quantify these associations; however, there are now validated methods to objectively measure technical skills at the surgeon level. Further, the technical skill score variation is associated with patient outcomes.

Notably, surgeons do not practice completely independently—there are teams of staff in the operating room responsible for a variety of different things, all aimed at taking the best possible care of the patient. So, even though the surgeon's technical skills as demonstrated on an intraoperative video may predict 26% of the patient outcome variability, there are other factors that play into the overall quality of a surgeon's service to their patient.

Nontechnical Skills as a Factor in Surgeon-Level Quality

Previous work has documented the importance of teamwork and other nontechnical skills in the operating room. 29 While the surgeon functions as the team lead, there are multiple members of the team who take part in some form or another in the care of that patient. Ignoring the dynamics of that team and how it functions leaves many potential areas for improvement unaddressed. It has been reported that a large portion of adverse surgical events occur due to system errors, with the breakdown in team communication alone accounting for more than 40% of these. 30 In 2003, using more than 20 years of prior research into teamwork, the department of defense (in collaboration with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) published protocols to help health care organizations improve team training. 31 Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety program has been used across the country to improve the effectiveness of teams inside and outside of the operating room. 32 The implementation of these strategies has created demonstrable change in metrics such as the percentage of on-time starts for first cases, reduction in the frequency of retained foreign bodies, and improved compliance in the “time-out” procedures. Since it is shown that improvement in these nontechnical skills has merit, we should therefore investigate how nontechnical skills can be promoted and enhanced. Simulation is used throughout surgical training to teach skill-based lessons and critical thinking. In the trauma world, for example, simulation allows the effective practice of skill for high-risk clinical scenarios, without the actual risk of a patient in shock awaiting the surgeon's decisions. 33 While there are benefits to these standardized practice scenarios, they often do not include other professions that are frequently present in real-life scenarios, such as nurses, anesthesiologists, and surgical technicians. 34 The presence of these other specialty team members in the scenarios helps to improve interprofessional communication and increases the overall effectiveness of the scenarios. The implementation of these team-based simulations has been shown to produce a statistically significant improvement in surgical morbidity and mortality. 35 Our ability to facilitate these team training exercises is likely to get easier with time. The rapid appearance and growth of tools like virtual reality, for example, has shown encouraging results in team training environments. 36 Apart from looking at the entire team, we must also look at the individual surgeon and consider what tools are available to offer nontechnical skills training.

In the United Kingdom, a Non-Technical Skills for Surgeons (NOTSS) program was developed which encompasses four areas of important nontechnical skills—situational awareness, communication and teamwork, leadership, and decision-making. 37 This tool, which includes the evaluation of individual surgeons in the operating room, has been validated and used in many countries when assessing nontechnical skills. 29 38 Despite this increasing recognition of the importance of a surgeon's nontechnical skills, evidence is lacking on if and how improvements in nontechnical skills can have tangible effects on overall patient outcomes. A team in New Hampshire showed that there was up to a 33% reduction in mortality when comparing patients treated by teams that had undergone training in certain nontechnical skills versus those taken care of by teams which had no training. 39 Abahuje and colleagues used the NOTSS tool to assess observed behaviors of surgeons during live operations and looked at how this affected their intraoperative performance. 40 Their study confirmed that nontechnical skills can be reliably assessed in the operating room, and using this information, further work can hopefully be done to study their effect on operating room performance, surgical training, and more importantly—patient outcomes. What role nontechnical skills assessment has on public reporting of quality measures and whether there is a demonstrable difference in patient outcomes between surgeon-level nontechnical skill scores is yet unknown.

Effects of Coaching

At some point in our life, we have all been inspired by someone who is great at what they do. A star swimmer, your favorite basketball team, or even a brilliant pianist. They spend thousands of hours training to do what they do. They practice repeatedly, analyze videos of themselves and others in their field, study theory and strategy, learn from mistakes, and practice some more. All this effort is so that when the time comes for that big game, or major show, they know exactly what to do. In many ways, surgical training follows these same principles. Yet even for the best athletes or musicians in the world, no one would reasonably expect them to have achieved their level of proficiency and success without the ongoing input of a coach. If there is such immense value in coaching for other high-performance jobs, why then should surgery be any different? While surgery is not a sport, it is obvious that a surgeon who is not performing at the top of their game has a greater potential to cause harm. In a 2022 systematic review looking at coaching in surgical education, the authors found that other well-established forms of guidance, such as mentorship and teaching, were being used interchangeably with coaching in the literature. 41 They suggest that the establishment of specific coaching criteria will help set coaching apart in future works and allow for more effective implementation of this necessary tool going forward. While these other activities are useful and necessary, by targeting existing skills and techniques, coaching allows for more specific goal setting and empowers the individual to improve their own performance. 42 Recently, the value of coaching in the surgical field has begun to gain recognition. Groups in multiple states including Wisconsin, Michigan, and Illinois have implemented coaching initiatives aimed at improving surgical quality and patient outcomes. Surgical societies have also begun to see the value of ongoing coaching, with the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons developing an online video-based didactic series in which learners “engage in intraoperative video-based coaching sessions.” The aim of the series is “sharing operative techniques and improving procedural confidence.” With increasing adoption, coaching can potentially be used to improve other areas of surgical performance such as teaching techniques, teamwork, leadership skills inside and outside of the operating room, and stress management and coping strategies. Similar to their study of video-based assessment of technical skills, the group in Illinois also looked at video-based coaching as a potential tool to improve technical skills and patient outcomes. 43 Participants identified many benefits including increased self-awareness, introduction to different techniques or methods that they may not have been directly exposed to during their training, and the ability to modify their practice when they identified a technique that was “better than the technique they are using.” Interestingly, but perhaps not totally surprisingly, they found that not all surgeons could accept the process for what it was, and there was an underlying perception that “coaching” implied that they were deficient in some way and required remediation. Although not always easy to do, they did find that when the right coach was paired with the right coachee, there was a useful exchange between them and both participants left the session having gained from the experience. While it is still unclear exactly which skills are the most likely to benefit from coaching, how exactly coaching impacts the end goal of patient outcome or ultimately what effect coaching has on overall surgeon-level quality, what we do know is that coaching is an area that has shown great potential for improving at least some aspects of surgical performance. In a 2022 survey of colorectal surgeons from across the country, Rivard et al found that although there was no agreement on what a perfect system of coaching would look like, there was “widespread enthusiasm” for the idea. 44

Conclusion

We are excited to see the measure of a surgeon's quality move beyond simply their operative volume or “adjusted complication rates.” Although there is obvious value in the use of large registries for certain metrics and analyses, we must also factor in the many areas of quality which these databanks fail to accurately capture. As technology rapidly evolves, we gain many potential new ways to evaluate and report quality and better measures of that quality at the surgeon level. The recognition of both technical and nontechnical skills as important components in the overall quality of care that we provide opens our eyes to different ways to approach quality improvement, and the advent of coaching as a possible accelerant for this change is a welcome addition to future quality improvement initiatives. While we have come a long way from the “end result cards” of Dr. Codman, the measure of surgical quality is still very much a work in progress.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest E.A.C.: None

J.J.S.: Consulting for Intuitive Surgical Inc. which is unrelated to the submitted work.

References

- 1.Chun J, Bafford A C. History and background of quality measurement. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2014;27(01):5–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1366912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts J S, Coale J G, Redman R R.A history of the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals[published correction appears in JAMA 1987 Nov 20;258(19):2698]JAMA 198725807936–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q. 2005;83(04):691–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hannan E L, Cozzens K, King S B, III, Walford G, Shah N R. The New York State cardiac registries: history, contributions, limitations, and lessons for future efforts to assess and publicly report healthcare outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(25):2309–2316. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferraris V A, Ferraris S P, Wehner P S, Setser E R. The dangers of gathering data: surgeon-specific outcomes revisited. Int J Angiol. 2011;20(04):223–228. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1284433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shih T, Cole A I, Al-Attar P M. Reliability of surgeon-specific reporting of complications after colectomy. Ann Surg. 2015;261(05):920–925. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall B L, Huffman K M, Hamilton B H. Profiling individual surgeon performance using information from a high-quality clinical registry: opportunities and limitations. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(05):901–913. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.07.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinn C M, Bilimoria K Y, Chung J W, Ko C Y, Cohen M E, Stulberg J J. Creating individual surgeon performance assessments in a statewide hospital surgical quality improvement collaborative. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;227(03):303–312000. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khuri S F, Daley J, Henderson W.Relation of surgical volume to outcome in eight common operations: results from the VA National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Ann Surg 199923003414–429., discussion 429–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birkmeyer J D, Stukel T A, Siewers A E, Goodney P P, Wennberg D E, Lucas F L. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(22):2117–2127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porter G A, Soskolne C L, Yakimets W W, Newman S C. Surgeon-related factors and outcome in rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 1998;227(02):157–167. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199802000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parry J M, Collins S, Mathers J, Scott N A, Woodman C B. Influence of volume of work on the outcome of treatment for patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1999;86(04):475–481. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engelhardt K E, Bilimoria K Y, Stulberg J J. Surgeon scorecards: accurate or not? Adv Surg. 2018;52(01):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedberg M W, Pronovost P J, Shahian D M. A methodological critique of the ProPublica surgeon scorecard. Rand Health Q. 2016;5(04):1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ban K A, Cohen M E, Ko C Y. Evaluation of the ProPublica surgeon scorecard “adjusted complication rate” measure specifications. Ann Surg. 2016;264(04):566–574. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaffe T A, Hasday S J, Dimick J B. Power outage-inadequate surgeon performance measures leave patients in the dark. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(07):599–600. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regenbogen S E, Read T E, Roberts P L, Marcello P W, Schoetz D J, Ricciardi R. Urinary tract infection after colon and rectal resections: more common than predicted by risk-adjustment models. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213(06):784–792. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burack J H, Impellizzeri P, Homel P, Cunningham J N., JrPublic reporting of surgical mortality: a survey of New York State cardiothoracic surgeons Ann Thorac Surg 199968041195–1200., discussion 1201–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burns E M, Pettengell C, Athanasiou T, Darzi A. Understanding the strengths and weaknesses of public reporting of surgeon-specific outcome data. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(03):415–421. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative . Birkmeyer J D, Finks J F, O'Reilly A. Surgical skill and complication rates after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(15):1434–1442. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1300625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stulberg J J, Huang R, Kreutzer L.Association between surgeon technical skills and patient outcomes[published correction appears in JAMA Surg. 2020 Oct 1;155(10):1002] [published correction appears in JAMA Surg. 2021 Jul 1;156(7):694]JAMA Surg 202015510960–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackenzie H, Ni M, Miskovic D. Clinical validity of consultant technical skills assessment in the English National Training Programme for laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2015;102(08):991–997. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bilgic E, Valanci-Aroesty S, Fried G M. Video assessment of surgeons and surgery. Adv Surg. 2020;54:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merkow R P, Massarweh N N. Looking beyond perioperative morbidity and mortality as measures of surgical quality. Ann Surg. 2022;275(02):e281–e283. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fecso A B, Szasz P, Kerezov G, Grantcharov T P. The effect of technical performance on patient outcomes in surgery: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2017;265(03):492–501. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin J A, Regehr G, Reznick R. Objective structured assessment of technical skill (OSATS) for surgical residents. Br J Surg. 1997;84(02):273–278. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1997.02502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reznick R K, MacRae H. Teaching surgical skills—changes in the wind. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(25):2664–2669. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brajcich B C, Stulberg J J, Palis B E. Association between surgical technical skill and long-term survival for colon cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(01):127–129. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood T C, Raison N, Haldar S. Training tools for nontechnical skills for surgeons—a systematic review. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(04):548–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gawande A A, Zinner M J, Studdert D M, Brennan T A. Analysis of errors reported by surgeons at three teaching hospitals. Surgery. 2003;133(06):614–621. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker D P, Beaubien J M, Holtzman A K. Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research; 2003. DoD Medical Team Training Programs: An Independent Case Study Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sinyard R D, Rentas C M, Gunn E G. Managing a team in the operating room: The science of teamwork and non-technical skills for surgeons. Curr Probl Surg. 2022;59(07):101172. doi: 10.1016/j.cpsurg.2022.101172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noonan M, Olaussen A, Mathew J, Mitra B, Smit V, Fitzgerald M. What is the clinical evidence supporting trauma team training (TTT): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019;55(09):551. doi: 10.3390/medicina55090551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan S B, Pena G, Altree M, Maddern G J.Multidisciplinary team simulation for the operating theatre: a review of the literature ANZ J Surg 201484(7-8):515–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forse R A, Bramble J D, McQuillan R. Team training can improve operating room performance. Surgery. 2011;150(04):771–778. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chheang V, Fischer V, Buggenhagen H. Toward interprofessional team training for surgeons and anesthesiologists using virtual reality. Int J CARS. 2020;15(12):2109–2118. doi: 10.1007/s11548-020-02276-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yule S, Flin R, Paterson-Brown S, Maran N, Rowley D. Development of a rating system for surgeons' non-technical skills. Med Educ. 2006;40(11):1098–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pradarelli J C, Gupta A, Lipsitz S. Assessment of the Non-Technical Skills for Surgeons (NOTSS) framework in the USA. Br J Surg. 2020;107(09):1137–1144. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neily J, Mills P D, Young-Xu Y. Association between implementation of a medical team training program and surgical mortality. JAMA. 2010;304(15):1693–1700. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abahuje E, Johnson J, Halverson A, Stulberg J J. Intraoperative Assessment of Non-Technical Skills for Surgeons (NOTSS) and qualitative description of their effects on intraoperative performance. J Surg Educ. 2022;79(05):1237–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2022.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Louridas M, Sachdeva A K, Yuen A, Blair P, MacRae H. Coaching in surgical education: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2022;275(01):80–84. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pradarelli J C, Hu Y Y, Dimick J B, Greenberg C C. The value of surgical coaching beyond training. Adv Surg. 2020;54:31–47. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kreutzer L, Hu Y Y, Stulberg J, Greenberg C C, Bilimoria K Y, Johnson J K. Formative evaluation of a peer video-based coaching initiative. J Surg Res. 2021;257:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rivard S J, Varlamos C, Hibbard C E. A national qualitative study of surgical coaching: opportunities and barriers for colorectal surgeons. Surgery. 2022;172(02):546–551. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2022.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]