Abstract

Mycobacterium avium intracellulare (MAI) infections of the hand, wrist, and upper extremity are rare, but potentially devastating atypical mycobacterial infections that can affect tendon, bone, and other soft tissues of the musculoskeletal system. We present an immunocompromised patient presenting with acute swelling and pain in the dorsum of the hand and wrist that underwent a wrist extensor tenosynovectomy with intraoperative cultures revealing infection with MAI. The patient developed severe progression of the infection with osteomyelitis of the distal forearm and carpal bones, multiple subsequent extensor tendon ruptures, and dorsal skin necrosis. The infection was eradicated with a combination of surgical treatment and antibiotic therapy. The case is discussed in context of the prior scant literature of infectious tenosynovitis of the hand, wrist, and upper extremity caused by MAI. This case report and literature review outline recommendations for diagnosis and effective treatment of MAI.

Keywords: atypical mycobacterial infection, mycobacterium avium intracellulare, septic extensor tenosynovitis

Mycobacterium avium intracellulare (MAI) is an atypical mycobacterial organism found most commonly as a pulmonary pathogen in immunocompromised individuals, such as those with cystic fibrosis, human immunodeficiency virus, or acquired immune deficiency syndrome. However, MAI can also be found in immunocompetent hosts. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 The organism can exist in various media, including soil and aerosolized water; birds and farm animals are the most common hosts. Tenosynovial infections of MAI of the hand and wrist have been rarely reported, but they can occur through direct inoculation or disseminated pulmonary disease. 2 The most common presentations of MAI tenosynovitis of the hand or wrist have been acute flexor tenosynovitis, 1 2 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 14 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 carpal tunnel syndrome, 4 6 7 8 10 11 16 17 18 19 20 26 27 and, less commonly, osteomyelitis 1 2 3 5 9 14 16 18 20 21 or septic arthritis. 2 3 5 9 18 20 Consensus for treatment is lacking, although published reports have shown that a combination of surgical excision and/or long-term antimycobacterial therapy has been successful.

We report a case of severe MAI infection of the wrist, causing extensor tenosynovitis and subsequent involvement of tendon, skin, and bony structures and loss of involved soft tissues. Eventually, the patient was successfully treated with serial surgical debridements and long-term antimycobacterial therapy. Few cases have been reported of MAI infections in the hand, wrist, and upper extremity, particularly of the extensor tendons.

Case Report

A 57-year-old male teacher presented with a past medical history significant for seronegative rheumatoid arthritis, treated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) including methotrexate, leucovorin, and tocilizumab. The patient had frequent environmental exposure to collecting and cleaning seashells at the beach. Five years prior to presentation, the patient underwent a right wrist flexor tenosynovectomy, carpal tunnel release, and ring finger A-1 pulley release for presumed flexor tendon inflammatory tenosynovitis. Culture specimens from that surgery were unremarkable, and pathologic assessment of the tenosynovial tissue revealed nonspecific inflammatory reaction and rice bodies. In the subsequent years, the patient's rheumatologist administered multiple prior corticosteroid injections in the dorsal right wrist for chronic wrist pain presumed to be inflammatory in nature.

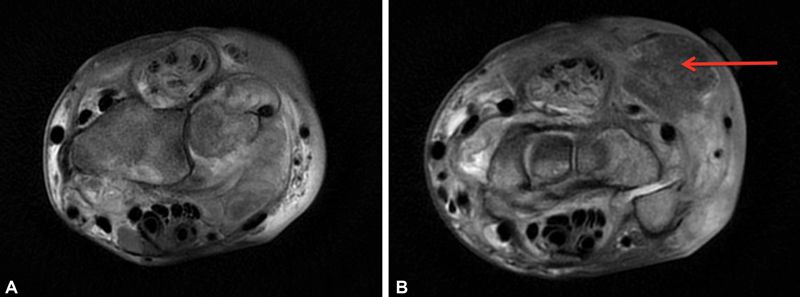

The patient's rheumatologist noted new-onset wrist pain, dorsal wrist swelling, and slight loss of middle finger extension. Physical examination revealed fullness around the fourth dorsal compartment and a lack of approximately 10 degrees of extension of the middle finger metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint without erythema, warmth, or fluctuance. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the wrist with and without contrast ( Fig. 1 ) revealed significant multicompartment tenosynovitis most extensively involving the fourth extensor compartment and scattered debris within tendon sheaths consistent with rice bodies or focal tenosynovitis.

Fig. 1.

( A and B ) Axial T2 images of the right wrist magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast at the level of the distal radius ( A ) and proximal carpal row ( B ) revealing severe multicompartment tenosynovitis most extensively involving fourth extensor compartment with splitting of the tendons and lesser involvement of the second and third extensor compartments. On the upper right of B , a 1.8 cm × 1.9 cm mass consistent with a rice body is seen (red arrow).

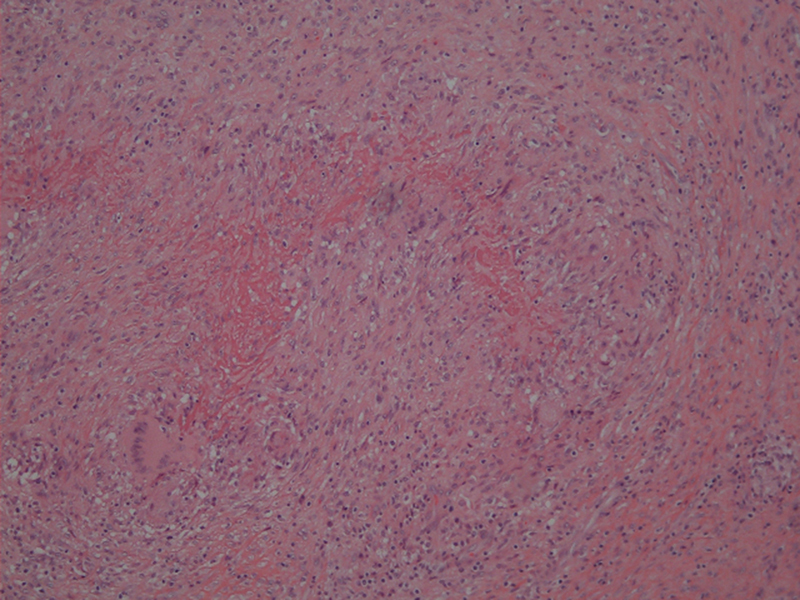

The wrist was aspirated that day, and cultures grew pan-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus . The patient was started on a course of intravenous daptomycin for 42 days and, due to lack of improvement, was referred to a hand surgeon for surgical treatment. The treating hand surgeon performed an extensor tenosynovectomy of the fourth dorsal extensor compartment soon after. Tenosynovial thickening was noted at the time of surgery. Two separate acid-fast cultures subsequently grew MAI at 9 days postoperatively. The patient was started on oral clarithromycin, ethambutol, and rifampin. Histologic analysis showed proliferative synovitis and palisading necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with multinucleated giant cells ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Tenosynovium of extensor digitorum communis (EDC) showing palisading necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with multinucleated giant cells.

A computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast 2 months postoperatively ( Fig. 3 ) revealed erosion of distal ulna, distal radius, lunate, capitate, and base of 3rd and 4th metacarpals consistent with osteomyelitis. Inflammatory markers at this time were elevated but trending down from the patient's preoperative values. The patient had a healed wound, improving motion and pain, and overall uneventful postoperative course until two and a half months postoperatively. At this time, he presented with new dorsal skin breakdown, wound drainage, acute loss of middle and long finger MCP joint extension, significant swelling, and erythema of the right dorsal wrist. There was extrusion of extensor tendon edges from the proximal wound defect ( Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 3.

( A – C ) Coronal images ( A and B ) of computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast revealing extensive bony erosions of the distal forearm, carpus, and base of the metacarpals consistent with osteomyelitis. Axial image ( C ) of CT scan revealing significant dorsal and volar erosion of cortices of distal ulna as well as volar erosion of cortices of distal radius.

Fig. 4.

Clinical photo of dorsum of right wrist revealing erythema, skin breakdown, and extrusion of extensor tendon rupture at two and a half months from initial debridement.

Repeat extensor tenosynovectomy and debridement of nonviable soft tissue revealed significant extensor tenosynovial proliferation and full-thickness rupture of the extensor digitorum communis (EDC) slips to the middle and ring fingers. A repeat acid-fast bacteria (AFB) culture was positive for MAI. Six days after the repeat debridement, the patient was unable to extend the index finger at the MCP joint, and there was a rapidly enlarging dorsal soft tissue defect with worsening drainage and erythema ( Fig. 5 ). A third surgical debridement was performed with placement of a vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) dressing. At the time of surgery, a rupture to the EDC and extensor indicis proprius to the index finger was seen, and tendon stumps were debrided to healthy tissue. Inflammatory serum markers were all within normal limits. The patient declined wound coverage of the dorsal skin defect with a flap, and a decision was made in conjunction with the hand surgeons, infectious disease specialist, and wound care specialist to treat the dorsal soft tissue defect with local wound care to promote healing by secondary intention. The VAC dressing was discontinued after 2 weeks, and wet-to-dry dressings with Dakin's solution and adaptec were administered.

Fig. 5.

Clinical photo of dorsum of right wrist severe dorsal soft tissue loss and worsening erythema and drainage at 6 days after second debridement.

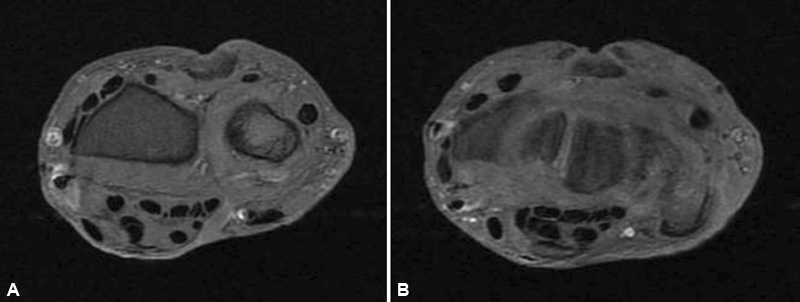

At 1 month postoperatively from the third debridement, the appearance of the wound had improved significantly, and skin edges were beginning to contract without erythema or drainage. Two months postoperatively from the third debridement, repeat local wound cultures were negative for AFB, and a repeat MRI of the wrist ( Fig. 6 ) revealed improvement of the fourth compartment tenosynovitis, attenuation of the index, middle, and ring finger EDC tendons, and stabilization of the destructive osseous changes visualized on prior CT scan. There was progressive wound granulation and reepithelialization with only the most distal 2 cm of the wound still without coverage. The patient continued the triple antibiotic therapy for the next 6 months for a total of 8 months.

Fig. 6.

Axial T2 images of the right wrist at the level of the distal radius ( A ) and proximal carpal row ( B ) revealing significant improvement in extensor tenosynovitis.

One year postoperatively, the wound was completely healed with no skin defect ( Fig. 7 ). The patient had a 50-degree extensor lag at the MCP joints of the index, middle, and ring fingers but had good intrinsic muscle function at the interphalangeal joints and full passive extension at the MCP joints. He declined delayed extensor tendon reconstruction.

Fig. 7.

Clinical photo of dorsum of right wrist 1 year postoperatively demonstrating completely healed soft tissue defect.

Discussion

Infections of the wrist and hand caused by atypical mycobacterium are infrequent. When present, however, tenosynovitis is the most common presentation of a mycobacterial infection of the hand or wrist. 1 2 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 14 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 As is common with infections of MAI, our patient's initial presentation was tenosynovitis, in this case resulting in swelling, restriction in digital extension, and pain over the digital extensor tendons. Atypical mycobacterial species, including MAI, are usually obtained from environmental sources such as soil, birds, farm animals, and water reservoirs, frequently from direct inoculation into the hand. 4 9 24 25 In the present case, environmental exposure consisted of frequent cleaning of seashells at the beach. MAI is not spread by person-to-person transmission.

A literature review of cases of MAI in the hand, wrist, and upper extremity was performed using PubMed (inclusive of all years until June 2021) and revealed a total of 40 prior cases reported in the literature ( Table 1 ). MAI in the upper extremities most commonly infected the flexor tendons of the hand or wrist and/or the surrounding bony structures. Thirty-one cases of MAI in the upper extremity exhibited tenosynovitis of the flexor tendons in the hand or wrist. 1 2 4 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 14 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 The present case, on the other hand, presented with tenosynovitis of the extensor tendons. Only three other cases exhibited tenosynovitis of the extensor tendons in the hand or wrist. 5 16 20 Ten cases of MAI in the upper extremity resulted in osteomyelitis, 1 2 3 5 9 14 16 18 20 21 and six cases of MAI in the upper extremity presented with septic arthritis. 2 3 5 9 18 20 Fourteen cases of MAI in the upper extremity caused atypical carpal tunnel syndrome. 4 6 7 8 10 11 16 17 18 19 20 26 27

Table 1. Previously reported cases of MAI infectious tenosynovitis of the hand or wrist.

| Reference | # | Age/Sex | Anatomic location | Antibiotics | Antibiotic duration (mo) | Surgical debridement | # of Debridements | Extensor tenosynovitis | Flexor tenosynovitis | Carpal tunnel syndrome | Osteomyelitis | Septic Arthritis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gunther et al, 1977 1 | 1 | 64/F | Middle finger flexor sheath | INH, RMP | 17 | Yes | 2 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Demoulin et al, 1984 2 | 1 | 61/F | Index finger flexor tendon sheath and PIPJs | ERY, TMP-SMX | 2.5 | Yes | 1 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Rolfe and Sowa, 1990 3 | 1 | 25/M | Wrist capitate and hamate bones | Amikacin, Ethi, Clof, RMP | 24 | Yes | 1 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Stark, 1990 4 | 1 | 62/F | Index finger flexor tendon sheath | INH, Eth, RMP | 12 | Yes | 2 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Whitaker et al, 1991 5 | 1 | 74/M | Wrist carpal, metacarpal, radius, and ulna bones | None | None | Yes | 1 | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Marchesoni et al, 1992 6 | 1 | 61/F | Ring and small finger flexor tendon sheath | Cyse, INH, RA | Unk | No | 0 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Eggelmeijer et al, 1992 7 | 1 | 57/F | Middle finger flexor tendon sheath | Eth, ansamycin | 9 | Yes | 1 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Kozin and Bishop, 1994 8 | 6 | 1. 57/M 2. 58/M 3.56/M 4.58/M 5.68/M 6. 49/F |

1. Wrist flexor tendon sheath 2. Elbow 3. Digits (unsp) 4. Digits (unsp) 5. Wrist flexor tendon sheath 6. Elbow |

1. INH, Eth, rifampin, Cyse 2. RMP 3. RMP, Eth, CPFX 4. INH, RMP, Eth 5. STM, RMP, Eth 6. RMP, Eth, INH |

1. 8 2. 1 3. 1 4. 24 5. 3 6. 36 |

Yes | 1. Unk 2. Unk 3. Unk 4. Unk 5. Unk 6. Unk |

1. No 2. Unsp 3. No 4. No 5. No 6. Unsp |

1. Yes 2. Unsp 3. Yes 4. Yes 5. Yes 6. Unsp |

1. Yes 2. No 3. Yes 4. No 5. No 6. No |

No | No |

| Darrow et al, 1995 9 | 2 | 1. 66/M 2.67/M | 1. Thumb and small finger and wrist flexor tendon sheath (horseshoe abscess) 2. Wrist lunate, capitate, hamate, and fourth metacarpal bones, ring finger flexor sheath | 1. RMP, Eth 2. CPFX, Eth, RMP, STM | 1. 6 2. Unk |

1. Yes 2. Yes | 1. 1 2.1 | 1. No 2. No | 1. Yes 2. Yes | 1. No 2. No | 1. No 2. Yes | 1. No 2. Yes |

| Lefèvre et al, 2000 10 | 1 | 55/F | Index finger flexor tendon sheath | RFB, CLM | 16 | Yes | 2 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Anim-Appiah et al, 2004 11 | 1 | 44/M | Wrist and palm flexor tendon sheaths | CLM, RFB, Eth | 12 | Yes | 2 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Akahane et al, 2006 12 | 1 | 65/M | Small finger and wrist flexor tendon sheath | RA, levofloxacin, Cyse | 6 | Yes | 2 | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Vuppalapati et al, 2006 13 | 1 | 58/M | Dorsal skin and subcutaneous tissue of hand and wrist | RA, Eth | 2 | Yes | 1 | No | No | No | No | No |

| Yoon et al, 2011 14 | 1 | 63/F | Wrist flexor tendon sheath | CLM, RFB, Eth | Unk | Yes | 1 | no | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Carlos et al, 2012 15 | 1 | 66/F | Dorsal skin and subcutaneous tissues of thumb | CLM, RFB, Eth | 9 | No | 0 | No | No | No | No | No |

| Tsai at el, 2013 16 | 1 | 66/F | Wrist flexor and extensor tendon | CLM, RFB, Eth | 9 | Yes | 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Regnard et al., 1996 17 | 1 | 76/F | Wrist flexor tendon sheath | Eth, INH, Pirilene | 18 | Yes | 2 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Kanik and Greenwald, 2000 18 | 1 | 53/F | Bilateral wrist flexor tendon sheath, thumb MCPJ, bilateral index finger MCPJ, middle finger MCPJ, thumb, index, and middle finger PIPJs | CLM, RFB, Eth | 24 | Yes | 3 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Moores and Grewal, 2011 19 | 1 | 77/F | Wrist flexor tendon sheath | None | Unk | Yes | 1 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Matcuk et al, 2020 20 | 1 | 80/F | Thumb, small finger, and wrist flexor tendon sheath (horseshoe abscess), middle flexor tendon sheath, ring finger extensor tendon sheath | Azithromycin, RFB (changed to moxifloxacin due to rash), and Eth, linezolid | 6–12 | Yes | 2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Choi et al, 2013 21 | 1 | 51/F | Wrist and thumb flexor tendon sheath | RA, INH, PZA and Eth, azithromycin | 12 | Yes | 3 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Hellinger et al, 1995 22 | 6 | 1. 50/M 2.65/M 3.82/M 4.66/M 5.71/F 6.48/F | 1. Middle finger flexor tendon sheath 2.Index finger MCPJ and PIPJ 3.Wrist flexor and extensor tendon sheaths 4.Index finger flexor tendon sheath and MCPJ 5.Wrist flexor tendon sheath 6.Middle finger MCPJ | 1. CLM, Eth, RMP, CPFX 2.None 3.CLM, CPFX, Eth 4.CLM, CPFX, Eth 5.CPFX, RMP, Eth 6.CPFX, Clof, Ethi, RMP | 1. 12 2. None 3.4 (discontinued)4. 12 5. 24 6. 2 (1 of RMP) | 1. Yes 2.Yes 3.Yes 4.Yes 5.Yes 6.Yes | 1. 1 2.1 3.2 4.1 5.1 6.1 | 1. Unsp 2.No 3.Unsp 4.No 5.Unsp 6.Unsp | 1. Unsp 2.Yes 3.Unsp 4.Yes 5.Unsp 6.Unsp | No | No | No |

| Hung et al, 2003 23 | 1 | 36/F | Index flexor tendon sheath | None | None | Yes | 1 | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Noguchi et al, 2005 24 | 2 | 1. 75/M 2.Unk | 1. Thumb and wrist flexor tendon sheath 2.Hand extensor tendon sheath | 1. CLM, minocycline 2.INH, RIF | 1. 24 2. 5 | 1. Yes 2. Unk | 1. 3 2. Unk | 1. No 2. Unk | 1. Yes 2. Unk | 1. No 2. No |

1. No 2. No |

1. No2. No |

| Namkoong et al., 2016 25 | 1 | 76/M | Thumb flexor tendon sheath and MCPJ | INH, RA, Eth(changed to CLM, RA, Eth, sitafloxacin due to failure of response) | 6, 24 | Yes | 3 | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Kelly et al, 1967 26 | 2 | 1. 65/F 2. 57/F | 1. Bilateral wrist flexor tendon sheath 2. Ring finger flexor tendon sheath | 1. STM, INH, pyridoxine 2. None | 1. 22 2. None | 1. Yes 2. Yes | 1. 1 2. 1 | 1. No 2. No | 1. Yes 2. Yes | 1. Yes 2. No | 1. No 2. No | 1. No 2. No |

| Sutker et al, 1979 27 | 2 | 1. 67/F 2. 57/M | 1. Wrist and palm flexor tendon sheath 2. Index finger flexor tendon sheath | 1. INH, Eth, RMP 2. INH, Eth, RMP, STM | 1. Unk 2. Unk | 1. Yes 2. Yes | 1. 1 2. 1 | 1. No 2. No | 1. Yes 2. Yes | 1. Yes 2. No | 1. No 2. No | 1. No 2. No |

| Raffi et al, 1990 28 | 1 | 46/M | Wrist flexor tendon sheath | RA, INH, PZA, PFX | 13 | Yes | 2 | No | Yes | No | No | No |

Abbreviations: CLM, clarithromycin; Clof, clofazimine; CPFX, ciprofloxacin; Cyse, cycloserine; ERY, erythromycin; Eth, ethambutol; Ethi, ethionamide; INH, isoniazid; MCPJ, metacarpophalangeal joints; PFX, pefloxacin; PIPJs, proximal interphalangeal joints; PZA, pyrazinamide; RA, rifampicin; RFB, rifabutin; RMP, rifampin; STM, streptomycin; TMP-SMX, co-trimoxazole; Unk, unknown; Unsp, unspecified.

The present case report illustrated a particularly severe infection in an immunocompromised host with risk factors including rheumatoid arthritis, use of DMARDs, and multiple prior local corticosteroid injections in the affected wrist. MAI can be found both in immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients but is more common in immunocompromised hosts compared with immunocompetent hosts. One case series of 44 patients with culture positive nontuberculous mycobacterial infection of an upper extremity identified 20 patients who were immunocompromised. Immunocompromised patients had fewer known inoculations compared with immunocompetent patients, but this series reported similar outcomes between immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients. 29 In another case series of 33 patients with culture-positive atypical mycobacterial infections of the upper extremity, immunocompetent patients had better outcomes than those who were immunocompromised. 8

Diagnosis of MAI requires fluid or tissue samples of the affected tissues. MAI tenosynovitis is frequently discovered from specimens of debridement. 1 24 As in the present case, cultures and/or acid-fast staining can diagnose MAI; however, they are not always reliable, as mycobacterial species require culture on Lowenstein–Jensen culture agar, and the clinician must have a suspicion of mycobacterial infection when specifying culture analysis. An alternative method to identify mycobacterium is through the use of broad-range polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification followed by suspension array identification system. This method is useful in identifying mycobacterial species for cases where mycobacteria are seen on histopathology but not on the tissue culture, but PCR amplification is also not always reliable. 2 15 24 PCR amplification has the advantage of rapid diagnosis, as traditional culture can take greater than 3 weeks to grow which may delay the initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy.

The present case was treated with a combination of 8 months of triple antimycobacterial therapy and three surgical debridements in addition to local wound care. While there is not clear consensus on the optimal treatment of MAI infection of the upper extremity, most reported cases have been treated with at least one surgical debridement and a combination of three antibiotics ( Table 1 ). 3 Controversy remains as to whether surgery or antibiotics alone may be optimal treatment to eradicate the infection. 8 29 30 31 Surgical debridement was performed on 39 of 42 cases found in the literature. 1 2 3 4 5 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Thirty-four patients needed a combination of surgical debridement and antibiotics. 1 2 3 4 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 16 17 18 20 21 22 24 25 26 27 28 There were only five cases in which the infection was successfully treated only with debridement 5 19 22 23 26 and only two cases in which antibacterial therapy alone was able to eradicate the infection. 6 15 Thus, it appears prudent to apply both surgical debridement and antibiotic therapy in the treatment of infection with MAI; the use of both surgical debridement and antibiotic therapy was effective in the present case. Repeat surgical debridements are frequently required, as illustrated in the literature; surgical debridement was required once for 20 cases, 2 3 5 7 9 13 14 16 19 22 23 26 27 twice for 9 cases, 1 4 10 11 12 17 20 22 28 and three times for 4 cases. 18 21 24 25 Of those patients that had surgery, nine had median nerve symptoms that warranted concurrent carpal tunnel release. 4 7 10 11 18 19 20 22 27

With regards to type of antibiotic treatment, a multidrug antibacterial therapy has been successful in patients with MAI. 1 7 10 11 12 22 30 31 There are no standard guidelines for which drugs to use, but a combination of clarithromycin or azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifampin or rifabutin has been used with success in the treatment of the majority of cases of tenosynovitis caused by MAI ( Table 1 ). 11 Prior authors have recommended antibiotics for a range of 8 months to 2 years to completely eradicate the infection. 1 3 4 8 19 24 29 In our patient, triple antibiotic therapy with oral clarithromycin, ethambutol, and rifampin was successful with an 8-month course of treatment. A decision was made between the patient and surgeon not to perform delayed extensor tendon reconstruction because of the risk of further infection with the introduction of foreign material such as allograft or suture material.

In summary, the current case illustrates that hand surgeons and other physicians should consider atypical mycobacterium infections when presented with tenosynovitis, especially when reoccurring, in an immunocompromised patient or in a patient on immune modulating agents. It is important to obtain adequate culture and biopsy specimen in such cases and alert the microbiology laboratory that specific culture techniques may be necessary to rule out atypical mycobacterial specimen. Antibacterial therapy or surgery alone are usually not able to eradicate the infection. 5 6 15 19 23 26 Combined surgical debridement and antimicrobial therapy provide the best chance of clinical resolution in the treatment of MAI.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Gunther S F, Elliott R C, Brand R L, Adams J P. Experience with atypical mycobacterial infection in the deep structures of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1977;2(02):90–96. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(77)80089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demoulin L, Lesire M R, Hisette L. Osteoarthritis and tenosynovitis of the finger due to Mycobacterium intracellulare. A case report and review of the literature [in French] Pathol Biol (Paris) 1984;32(09):965–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rolfe B, Sowa D T. Mixed gonococcal and mycobacterial sepsis of the wrist. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(257):100–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stark R H. Mycobacterium avium complex tenosynovitis of the index finger. Orthop Rev. 1990;19(04):345–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitaker M D, Jelinek J S, Kransdorf M J, Moser R P, Jr, Brower A C. Case report 653: arthritis of the wrist due to Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare. Skeletal Radiol. 1991;20(04):291–293. doi: 10.1007/BF02341669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchesoni A, Parafioritti A, Tosi S. On another case of tenosynovitis due to Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1992;10(06):630–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eggelmeijer F, Kroon F P, Zeeman R J, Dijkmans B A, van 't Wout J W. Tenosynovitis due to Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare: case report and a review of the literature. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1992;10(02):169–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kozin S H, Bishop A T. Atypical Mycobacterium infections of the upper extremity. J Hand Surg Am. 1994;19(03):480–487. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darrow M, Foulkes G, Richmann P N, de los Reyes C L, Floyd W E., III Deep infection of the hand with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare: two case reports. Am J Orthop. 1995;24(12):914–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lefèvre P, Gilot P, Godiscal H, Content J, Fauville-Dufaux M. Mycobacterium intracellulare as a cause of a recurrent granulomatous tenosynovitis of the hand. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;38(02):127–129. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(00)00169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anim-Appiah D, Bono B, Fleegler E, Roach N, Samuel R, Myers A R. Mycobacterium avium complex tenosynovitis of the wrist and hand. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(01):140–142. doi: 10.1002/art.20086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akahane T, Nakatsuchi Y, Tateiwa Y. Recurrent granulomatous tenosynovitis of the wrist and finger caused by Mycobacterium intracellulare: a case report. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;56(01):99–101. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vuppalapati G, Turner A, La Rusca I, Schonauer F. Mycobacterium avium infection involving skin and soft tissue of the hand treated by radical debridement and reconstruction in addition to multidrug chemotherapy. J Hand Surg [Br] 2006;31(06):693–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon H J, Kwon J W, Yoon Y C, Choi S H. Nontuberculous mycobacterial tenosynovitis in the hand: two case reports with the MR imaging findings. Korean J Radiol. 2011;12(06):745–749. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2011.12.6.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlos C A, Tang Y W, Adler D J, Kovarik C L. Mycobacterial infection identified with broad-range PCR amplification and suspension array identification. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39(08):795–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2012.01934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai M S, Chang C M, Yang D C, Huang C C. Mycobacterium avium complex tenosynovitis manifesting as carpal tunnel syndrome in an elderly adult. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(10):1842–1843. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regnard P J, Barry P, Isselin J. Mycobacterial tenosynovitis of the flexor tendons of the hand. A report of five cases. J Hand Surg [Br] 1996;21(03):351–354. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(05)80201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanik K S, Greenwald D P. Mycobacterium avium/Mycobacterium intracellulare complex-associated arthritis masquerading as a seronegative rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2000;6(03):154–157. doi: 10.1097/00124743-200006000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moores C D, Grewal R. Radical surgical debridement alone for treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome caused by mycobacterium avium complex flexor tenosynovitis: case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(06):1047–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matcuk G R, Jr, Patel D B, Lefebvre R E. Horseshoe abscess of the hand with rice bodies secondary to mycobacterium avium intracellulare infection. Clin Imaging. 2020;63:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi J J, Ban W H, Jung Y H. Mycobacterial tenosynovitis of the hand in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16(03):364–366. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hellinger W C, Smilack J D, Greider J L., Jr Localized soft-tissue infections with Mycobacterium avium/Mycobacterium intracellulare complex in immunocompetent patients: granulomatous tenosynovitis of the hand or wrist. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21(01):65–69. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hung G U, Lan J L, Yang K T, Lin W Y, Wang S J. Scintigraphic findings of Mycobacterium avium complex tenosynovitis of the index finger in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Nucl Med. 2003;28(11):936–938. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000093093.00736.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noguchi M, Taniwaki Y, Tani T. Atypical Mycobacterium infections of the upper extremity. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2005;125(07):475–478. doi: 10.1007/s00402-005-0042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Namkoong H, Fukumoto K, Hongo I, Hasegawa N. Refractory tenosynovitis with ‘rice bodies’ in the hand due to Mycobacterium intracellulare. Infection. 2016;44(03):393–394. doi: 10.1007/s15010-015-0844-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly P J, Karlson A G, Weed L A, Lipscomb P R. Infection of synovial tissues by mycobacteria other than Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1967;49(08):1521–1530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sutker W L, Lankford L L, Tompsett R. Granulomatous synovitis: the role of atypical mycobacteria. Rev Infect Dis. 1979;1(05):729–735. doi: 10.1093/clinids/1.5.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raffi F, Moinard D, Drugeon H B.Non-tuberculous mycobacterial tenosynovitis Lancet 1990335(8689):613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sotello D, Garner H W, Heckman M G, Diehl N N, Murray P M, Alvarez S. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections of the upper extremity: 15-year experience at a tertiary care medical center. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43(04):3870–3.87E10. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zenone T, Boibieux A, Tigaud S. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial tenosynovitis: a review. Scand J Infect Dis. 1999;31(03):221–228. doi: 10.1080/00365549950163482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsueh J H, Fang S Y, Hsieh Y H, Chen L W, Lee S S. Failure among patients with non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections in skin, soft tissue, and musculoskeletal system in southern Taiwan, 2012–2015. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2019;20(06):492–498. doi: 10.1089/sur.2018.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]