Summary

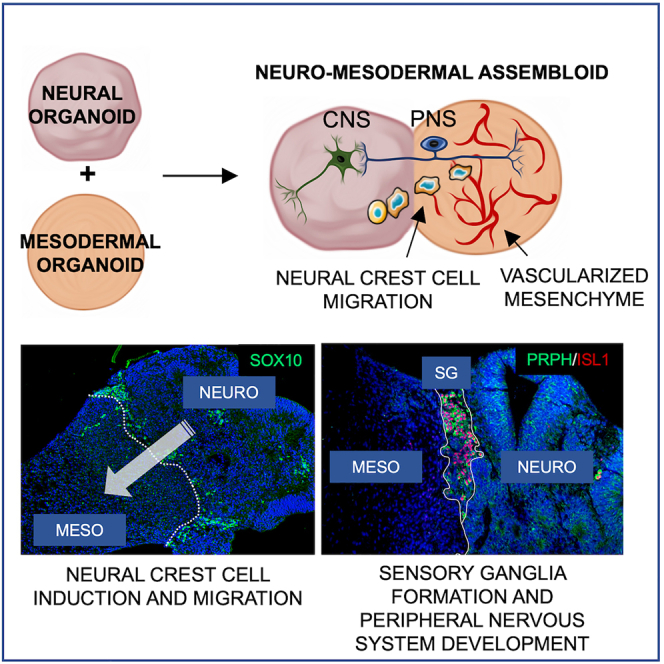

Here we describe a novel neuro-mesodermal assembloid model that recapitulates aspects of peripheral nervous system (PNS) development such as neural crest cell (NCC) induction, migration, and sensory as well as sympathetic ganglion formation. The ganglia send projections to the mesodermal as well as neural compartment. Axons in the mesodermal part are associated with Schwann cells. In addition, peripheral ganglia and nerve fibers interact with a co-developing vascular plexus, forming a neurovascular niche. Finally, developing sensory ganglia show response to capsaicin indicating their functionality.

The presented assembloid model could help to uncover mechanisms of human NCC induction, delamination, migration, and PNS development. Moreover, the model could be used for toxicity screenings or drug testing. The co-development of mesodermal and neuroectodermal tissues and a vascular plexus along with a PNS allows us to investigate the crosstalk between neuroectoderm and mesoderm and between peripheral neurons/neuroblasts and endothelial cells.

Keywords: peripheral nervous system, neural crest, sensory ganglia, sensory neuron, vasculature, blood vessel, neural organoid, mesodermal organoid, assembloid, human induced pluripotent stem cells

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Novel neuro-mesodermal assembloid model of peripheral nervous system development

-

•

Model covers neural crest cell induction, migration, and ganglion formation

-

•

Ganglia send projections to the mesodermal as well as neural compartment

-

•

Peripheral ganglia and nerve fibers interact with a co-developing vascular plexus

Wörsdörfer and colleagues describe a neuro-mesodermal assembloid model recapitulating aspects of peripheral nervous system development including neural crest cell induction, migration, and peripheral ganglion formation. The ganglia send projections to the mesodermal and the neural compartment. Peripheral ganglia and nerve fibers interact with a co-developing vascular plexus, forming a neurovascular niche. Finally, sensory ganglia respond to capsaicin indicating their functionality.

Introduction

Within the last decade, numerous human stem cell-based 3D cell culture models were explored, mimicking the development of different organs and tissues. These tissue models are termed organoids. Organoids can provide an unprecedented opportunity to investigate and understand fundamental aspects of human developmental biology in vitro (Kim et al., 2020). To increase tissue complexity and allow multi-lineage interaction, different organoids can be combined forming assembloids (Kelley and Pasca, 2022). Recently, so-called embryoids were established (Morales et al., 2021). Although, most organs and tissues have been modeled as organoids or assembloids, suitable 3D in vitro models of peripheral nervous system (PNS) development are still rare.

The nervous system is divided into two parts, the central nervous system and the PNS, which closely interact with each other. The PNS develops mostly from a highly fascinating cell population, the so-called neural crest cells (NCCs) (Etchevers et al., 2019). NCCs are of neuroectodermal origin and arise at the neural plate border. They undergo an epithelial to mesenchymal transition, start to delaminate, and finally migrate into distinct regions of the embryo shortly after neurulation. During this process, a part of the NCC population undergoes natural reprogramming processes involving OCT4 reactivation to broaden their differentiation potential (Zalc et al., 2021). As soon as migrating NCCs reach their destination, cells start to differentiate, e.g., into sensory or sympathetic neurons, Schwann cells (SCs), melanocytes, as well as smooth muscle cells, chondrocytes, or osteocytes.

Here we describe a neuro-mesenchymal assembloid model that recapitulates PNS development in vitro. The assembloid model allows neuro-mesodermal interactions and is suitable for the investigation of NCC induction, delamination, migration, and early PNS development.

Results

To generate the assembloid model, induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived SOX1+ neuroepithelial cell aggregates and mesodermal cell aggregates were brought in co-culture (Figures 1A and 1B). The purpose of this co-culture is to generate a neuro-mesodermal interface, at which an intercellular crosstalk between both tissue compartments takes place. Neuro-mesodermal interactions were discussed to trigger NCC induction and delamination in the embryo. Moreover, the mesenchymal part provides guidance for migrating NCCs and growing peripheral axons (Kahane and Kalcheim, 2021).

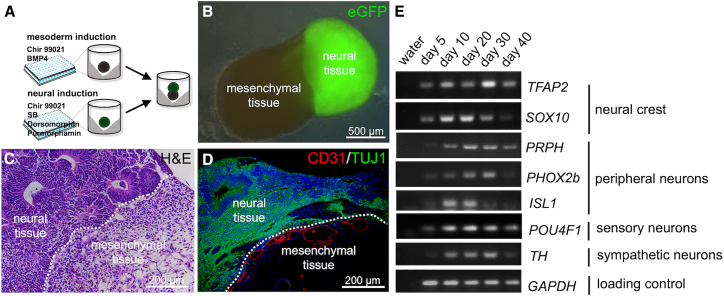

Figure 1.

Generation and initial characterization of neuro-mesodermal assembloids

(A) Schematic representation of the experimental workflow.

(B) Depiction of a typical neuro-mesodermal assembloid at day 14 of co-culture. The neural organoid was generated using GFP-labeled iPS cells.

(C) Histological section of a neuro-mesodermal assembloid at day 14 of co-culture. The paraffin section was stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E stain).

(D) Immunofluorescence analysis of neuro-mesodermal assembloid at day 14 in co-culture. The histological section incubated with specific antibodies targeted against the endothelial marker-protein PECAM (CD31) and the neuron-specific marker protein βIII-TUBULIN (TUJ1). A CD31+ vascular network is visible at the neuro-mesodermal interface.

(E) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analyses detecting the expression of neural crest marker genes (TFAP2, SOX10), peripheral neuron marker genes (PRPH, PHOX2b, ISL1), as well as sensory neuron (POU4F1 [BRN3a]) and sympathetic neuron (TH) markers. Detection of GAPDH was used as loading control. Analyses were performed using mRNA from assembloids at different time points in co-culture (day 5–day 40).

Neural and mesodermal cell aggregates were differentiated separately from iPSCs utilizing different combinations of small molecules and cytokines as previously described (Worsdorfer et al., 2019, 2020). Neural aggregate formation takes 7 days and is induced by purmorphamine, SB431542, dorsomorphin, and CHIR99021 (Figure 1A). At culture day 7, cells within the neural aggregates display a neural plate-like early neuroepithelial identity and contain cells that have the potential to differentiated into derivates of the CNS and PNS (Reinhardt et al., 2013). In the assembloids, formation of neural rosettes and expression of TUBB3 (TUJ1) are hallmarks of the neural part (Figures 1C and 1D). The generation of mesodermal aggregates takes 4 days and is directed by CHIR99021 and BMP4. At the day of assembloid fusion, mesodermal aggregates consist of undifferentiated mesodermal progenitor cells (Schmidt et al., 2022). In the assembloid, the mesodermal part is characterized by loose connective tissue and the presence of CD31-positive blood vessel-like structures that form a perineural vascular plexus at the neuro-mesodermal interface (Figures 1C and 1D).

Neuro-mesodermal assembloids were kept in co-culture for up to 40 days and were initially characterized by immunofluorescence staining and RT-PCR analyses.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR revealed the expression of NCC markers (TFAP2 and SOX10) as well as sensory and sympathetic peripheral neuron markers (PRPH, ISL1, BRN3a, TH). These initial experiments gave a first hint indicating the formation of a PNS (Figure 1E) (Hogan et al., 2004).

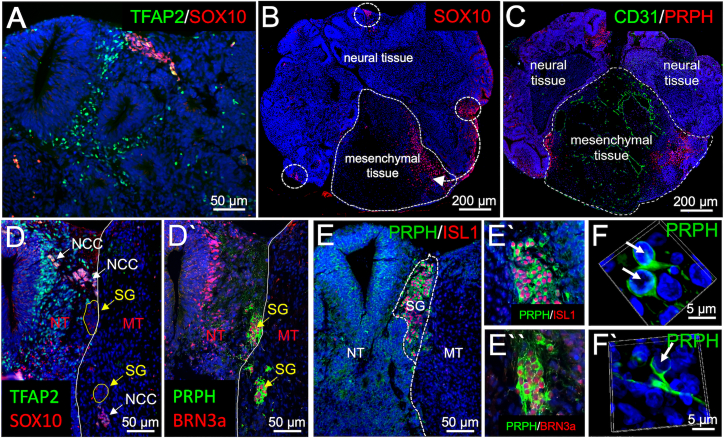

Histological analyses using immunofluorescence microscopy revealed the appearance of NCC-like cells within the neural part of the assembloid (Figures 2A, S1F, and S1I). A part of these cells is TFAP2+/SOX10–, probably representing NCC precursors, while others are TFAP2+/SOX10+, probably representing migrating NCCs (Figures 2A and S2) (Lai et al., 2021). TFAP2+/SOX10– NCC precursors are located within the neuroepithelium, while TFAP2+/SOX10+ NCCs are found in more loosely arranged parts of the neural tissue. Of note, we also found a third TFAP2+ cell population, TFAP2+/MAP2+ cells, which did not show PRPH or SOX10 expression. We conclude that these cells represent a population of developing CNS neurons (Figure S2C). The observed NCCs arise at different locations within the neural tissue and subsequently migrate to the neuro-mesodermal interface (Figure S2A).

Figure 2.

Neural crest cell migration and sensory ganglion formation in neuro-mesodermal assembloids

(A–F′) Immunofluorescence analysis performed on sections from neuro-mesodermal assembloids at day 14 in co-culture. (A) Detection of TFAP2 and SOX10 expression in the neural part of the assembloid. (B) Detection of SOX10 expression shows neural crest migration from the neural into the mesodermal part of the assembloid. (C) PRPH+ cells indicating PNS neurons are detected at the neuro-mesodermal interface. A CD31+ vascular plexus is visible in the mesodermal part of the assembloid. (D–D′) While TFAP2+/SOX10+ neural crest cells (NCCs) migrate from the neural (NT) into the mesodermal (MT) part of the assembloid, PRPH+/BRN3a+ sensory ganglia (SG) form along the migration tract near the neuro-mesodermal interface. (E–E′) Cells within the sensory ganglia co-express the sensory neuron marker proteins peripherin, BRN3a, and ISL1. (F–F′) Sensory neurons show typical pseudo-unipolar morphology.

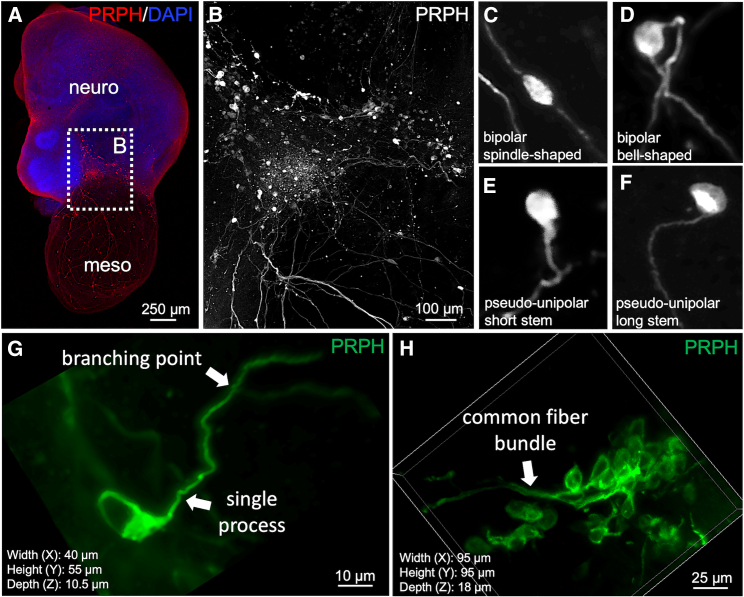

To assess if the neuro-mesodermal interaction is required for NCC induction, we compared SOX10 and TFAP2 expression in neural aggregates and mesodermal aggregates as well as neuro-mesodermal assembloids. We found that NCCs arise in both, neural aggregates as well as neuro-mesodermal assembloids. As expected, mesodermal aggregates did not show SOX10 or TFAP2 expression (Figure S1). While NCCs in the neural aggregates were found to cover the whole aggregate surface (Figure S1H), NCCs in neuro-mesodermal assembloids were mainly recruited to the neuro-mesodermal interface and started to infiltrate the mesodermal part from approximately day 8 on (Figures 2B, 2C, and S1I). Moreover, ganglion-like clusters of peripheral nerve cell perikarya were found at the interface between the neural and the mesodermal part (Figures 2C and 2D′). Cells within these ganglion-like structures stained double-positive for PRPH and ISL1 (Figure 2D′), confirming their peripheral neuron identity (Thor et al., 1991; Escurat et al., 1990). Additionally, they were also found to be BRN3a-positive (Figures 2E and 2E′), identifying them as sensory neurons (Dykes et al., 2011). 3D reconstruction of confocal fluorescence microscopic images shows a mostly pseudo-unipolar cell morphology in approximately 80% of the cells at day 14 of co-culture (Figures 2F, 2F′, 3E, 3F, and 3G). However, we also detected spindle-shaped bipolar peripheral neurons as well as bell-shaped bipolar neurons (Figures 3C and 3D) as naturally observed during sensory neuron development in the embryo (Matsuda et al., 1998). We need to mention that the morphology of only those neurons could be assessed that were not located in densely packed cell clusters (Figure 3H).

Figure 3.

Neuronal morphologies in sensory peripheral ganglia at the neuro-mesodermal interface

(A) Overview about a neuro-mesodermal assembloid. PRPH is detected by immunofluorescence microscopy. The picture shows a maximum intensity projection of confocal images.

(B) A higher magnification from (A) (white dotted square). The image shows a ganglion-like assembly of peripheral neurons at the neuro-mesodermal interface.

(C–F) Single peripheral neurons from (B) are depicted in high magnification showing a bipolar spindle-shaped (C), a bipolar bell-shaped (D), as well as a pseudo-unipolar morphology with a single short stem (E) or long stem (F) cellular process.

(G) Depiction of a pseudo-unipolar peripheral neuron.

(H) Most peripheral neurons are found in dense cell clusters, and their exact cellular morphology is difficult to assess.

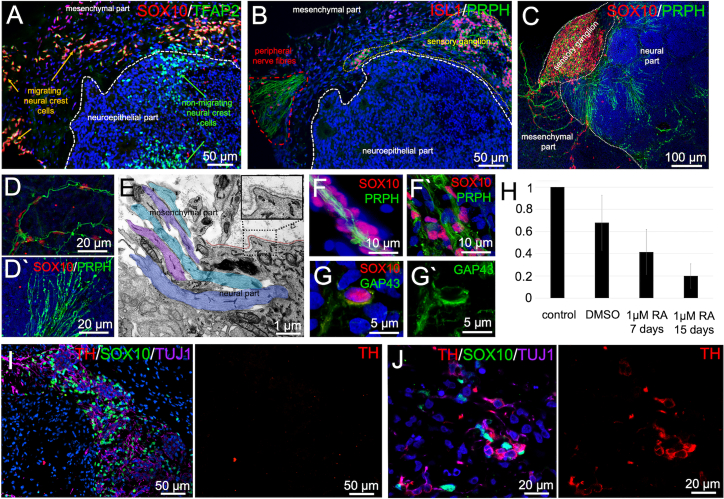

Bundles of peripheral nerve fibers were found to project from the sensory ganglia into the mesenchymal tissue (Figure 3A) and were accompanied by SOX10+ cells (Figures 4A and 4B). Moreover, 3D reconstruction of whole-mount-stained and tissue-cleared assembloids revealed that PRPH-positive neuronal processes do not only grow toward the mesenchymal but also the neural part (Figure 4C, Video S1) creating an interface between peripheral and central nervous system. Interestingly, peripheral nerve fibers in the mesenchymal part were accompanied by SOX10-positive cells (Figure 4D), which was not the case in the neural part (Figure 4D′). This is like in the in vivo situation in which peripheral neurons are either myelinated by SCs or associated with non-myelin forming SCs while central fibers are myelinated by SOX10– oligodendrocytes.

Figure 4.

Peripheral nerve formation and appearance of sympathetic ganglia in neuro-mesodermal assembloids

(A and B) Immunofluorescence analyses performed on 20-day-old assembloids show neural crest cell migration indicated by SOX10 and TFAP2 expression (A) as well as ISL1/PRPH+ ganglion formation (B). Sensory ganglia send peripheral nerve-like axon bundles into the mesodermal part of the assembloid.

(C) 3D reconstruction of immunofluorescence pictures taken from tissue cleared assembloid. A SOX10/PRPH+ ganglion is depicted sending axonal projections to the neural and the mesodermal part of the assembloid.

(D) Axons projecting to the mesodermal part are accompanied by SOX10+ Schwann cell-like cells (D). Axons projecting to the neural tissue are devoid of SOX10+ cells (D′).

(E) Transmission electron microscopic (TEM) analysis reveals axons (blue, purple, and green color) penetrating the basement membrane (brown color) at the neuro-mesodermal interface marking the basal side of the neuroepithelium.

(F and G) Peripheral nerve-like axon bundles are accompanied by SOX10/GAP43+ Schwann cell-like cells.

(H) Treatment of assembloids with 1 μM retinoic acid (RA) reduces SOX10 expression in a time-dependent manner. The solvent DMSO also showed a mild effect on SOX10 expression. The graph includes data from three independent experiments.

(I) Large sensory ganglia at the neuro-mesodermal interface do not show expression of the sympathetic neuron marker TH.

(J) Small TH/SOX10+ sympathetic ganglia can be found deeper within the mesodermal part of the assembloid.

The movie shows a large sensory ganglion at the neuro-mesodermal interface. Peripheral neurons (green) were detected using specific Peripherin antibody. Neural crest cells and derivates were detected using a SOX10 antibody (red). Nuclei are stained with DAPI. The movie shows a 3D reconstruction from a z stack of confocal images taken by laser scanning microscopy.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed that bundles of axons perforate the basement membrane at the basal side of the neuroepithelium to connect neural and mesenchymal parts of the assembloid (Figure 4E). We conclude that at least some of the SOX10+ cells accompanying peripheral nerve fiber bundles (Figures 4F and 4F′) represent SCs or SC precursors, which are exclusively found in the PNS. This assumption is supported by the detected co-expression of SOX10 and GAP43 (Figures 4G and 4G′) (Kim et al., 2017). Interestingly, younger assembloids show bundles of axons in contact with each other but isolated from the surrounding tissues by a sheath of SCs as observed in the early embryonic peripheral nerve (Figure 4F) (Peters and Muir, 1959). Later, the SCs invade the nerve, separating the axons into smaller bundles (Figure 4F′).

To test whether the assembloid model is suitable for drug testing applications or toxicological screenings, we treated the cultures with different concentrations of retinoic acid (RA). RA has been shown to impact NCC delamination and migration and can cause a condition termed fetal retinoid syndrome that results in neural crest migration defects (Cohlan, 1953). We observed that RA treatment reduced the mRNA expression level of SOX10 in the assembloid cultures in a time-dependent manner. The solvent DMSO showed a mild effect on SOX10 expression as well (Figure 4H).

In the embryo, besides forming sensory ganglia, the migrating NCCs give rise to sympathetic ganglia as well. These are characterized by co-expression of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and PRPH (Escurat et al., 1990; Gervasi et al., 2016). We could detect only few weakly TH-positive cells within the sensory ganglia (Brumovsky et al., 2006) (Figure 4I and S3A–S3C) but found a higher proportion of TH/TUJ1 double-positive cells in larger distance from the neural part forming small ganglion-like structures along with SOX10+ SCs (Figures 4J and S3D–S3H). This is in line with the in vivo situation where sensory ganglia are located near the CNS, while sympathetic ganglia are located more distant within the sympathetic trunk or are associated with the abdominal aorta or its major branches (Scott-Solomon et al., 2021).

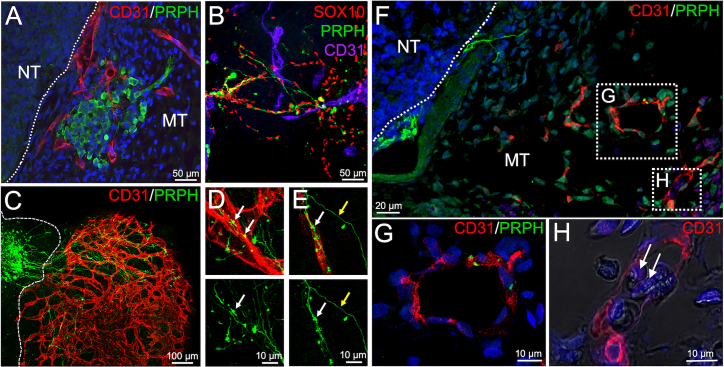

The observed sensory ganglia were surrounded by a dense CD31+ vascular network (Figure 5A). Within the mesodermal part of the assembloid, peripheral nerve fibers get in contact with CD31+ blood vessels (Figure 5B). 3D reconstruction of whole-mount-stained and tissue-cleared assembloids reveals a close interaction of PRPH+ sensory nerve fibers with the developing vascular plexus (Figure 5C, Video S2). Moreover, when the axons contact the vessels, they form bouton en passant-like structures indicating synapse formation (Figures 5D and 5E, white arrow), which is not observed in axons not contacting a vessel (Figures 5D and 5E, yellow arrow).

Figure 5.

Close interaction of blood vessels and peripheral nerves in neuro-mesodermal assembloids

(A) Immunofluorescence analyses performed on sections from neuro-mesodermal assembloids at day 20 in co-culture. PRPH+ ganglia at the neuro-mesodermal interface are enwrapped by an endothelial network.

(B) Migrating neural crest cells (SOX10+) and peripheral neurons (PRPH+) were observed to be in close contact with CD31+ vascular structures.

(C) 3D reconstruction of immunofluorescence pictures taken from tissue cleared assembloid. A large sensory ganglion is depicted sending multiple axonal projections into the mesodermal part of the assembloid. Moreover, a complex and well-organized vascular plexus can be observed.

(D and E) Peripheral nerve fibers align with blood vessels and form bouton en passant-like structures (white arrow). These structures are not observed in axons without vessel contact (white arrow).

(F–H) Transplantation of neuro-mesodermal assembloids on the chicken chorioallantoic membrane (CAM). 6 days after transplantation, assembloids were analyzed for PRPH and CD31 expression (F). Peripheral ganglia and nerve fibers could be observed. PRPH+ fibers were found in close contact to CD31+ human blood vessels (G). Chicken erythrocytes (white arrow in H) were observed inside the vessel lumen indicating vessel functionality (H).

The movie shows a hierarchically organized network of blood vessels (red) and peripheral nerve fiber bundles (green) in the mesodermal part of the assembloid. Peripheral neurons were detected using specific peripherin antibody. Blood vessels were detected using a CD31 antibody. The movie shows a 3D reconstruction from a z stack of confocal images taken by laser scanning microscopy.

To test the functionality of the vascular network, neuro-mesodermal assembloids were transplanted on the chicken chorioallantoic membrane (CAM), which led to the connection of human assembloid vessels to the chicken circulatory system (Figures 5F–5H). 6 days after transplantation, paraffin sections were made, and immunofluorescence analyses were performed. We were able to show CD31+ vascular structures as well as PRPH+ ganglia and nerve fibers. Again, peripheral nerve fibers were observed to contact human blood vessels (Figure 5G). Moreover, nucleated chicken erythrocytes were found inside the vessel lumen indicating perfusability (Figure 5H).

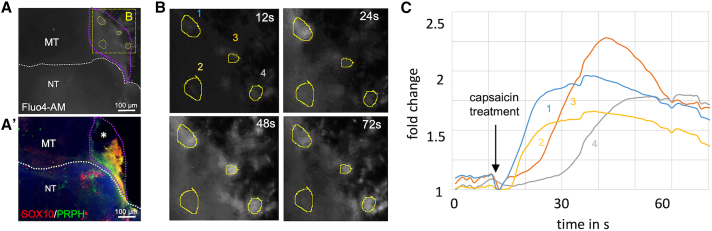

To test the functionality of sensory ganglia, we performed calcium imaging. For that purpose, assembloids were loaded with the calcium indicator Fluo4-AM and treated with the TRPV1-receptor agonist capsaicin (Caterina et al., 1997). We observed that intracellular calcium levels increased 2-fold in cells located within a sensory ganglion in response to capsaicin treatment indicating the presence of at least some functional nociceptive neurons (Figure 6, Video S3).

Figure 6.

Peripheral ganglia are responsive to capsaicin treatment

(A) Neuro-mesodermal assembloids were loaded with the calcium indicator dye Fluo4-AM and treated with capsaicin. Elevated calcium levels in response to capsaicin treatment were observed in a distinct region of the organoid (purple dotted line). See also Video S3. (A′) After calcium measurement, assembloids were fixed in 4% PFA solution, whole-mount stained for SOX10 and PRPH, and tissue cleared. 3D reconstruction of confocal immunofluorescence images confirmed the location of a peripheral ganglion in the capsaicin responsive region. Tissue was partially destroyed during sample preparation at black area marked with white asterisk.

(B) Higher magnification of the image depicted in (A) (yellow dotted square). Pictures show Fluo4-AM fluorescence at different time points (12, 24, 48, and 72 s). Capsaicin was added to the cultures after 12 s.

(C) Quantification of Fluo4-AM fluorescence intensity in four selected regions of interest (ROIs) (yellow circles in A and B).

The movie shows a calcium imaging experiment (left side). The intracellular calcium levels were visualized using Fluo4-AM. Calcium levels rise in response to capsaicin treatment. Video plays at 8x speed. After calcium imaging, the assembloid was fixed and whole-mount stained using specific antibodies targeted against peripherin (green) and SOX10 (red) to visualize the position of the peripheral ganglion (right side).

Discussion

Here we present a novel in vitro assembloid model mimicking several aspects of PNS development. The assembloids allow to investigate mechanisms of NCC migration in 3D cell culture without any need for animal experimentation and directly on human tissue.

The assembloids are easy to culture and develop within 20–40 days in agarose-coated non-adhesive 96-well plates. They can be manufactured in large numbers with comparable differentiation outcome (Figure S4), which makes them an attractive platform for toxicity testing or drug screenings, e.g., to identify potential teratogenic substances that influence neural crest cell delamination and migration during embryonic development (Cerrizuela et al., 2020) as demonstrated in a proof-of-concept experiment using RA (Cohlan, 1953).

Although a variety of tissues and early developmental embryo stages have been mimicked in the lab within the last decade, 3D tissue culture models of neural crest migration and PNS development are still rare. A recent publication describes neural crest cell migration and PNS development in the complex environment of long-term cultured elongating human gastruloids (Olmsted and Paluh, 2021). Two other publications describe neuromuscular organoids. These develop from neuro-mesodermal progenitor cells and show the formation of motor neurons and sensory neurons along with skeletal muscle (Faustino Martins et al., 2020; Pereira et al., 2021). An interesting paper by Xiao and colleagues describes a method to directly reprogram mouse and human fibroblasts into sensory neurons. The authors observed the appearance of ganglion-like cell clusters during the reprogramming process, which they termed “sensory ganglion organoids” (Xiao et al., 2020). These are complex assemblies of different subtypes of functional sensory neurons that arise in 2D cell culture during the reprogramming process. However, they are devoid of glial cell types such as SCs or satellite cells, are not vascularized, and are not embedded into connective tissue.

Here we present an alternative and easy to handle neuro-mesodermal assembloid model, which is generated by co-culturing mesodermal and neural spheroids. An interesting aspect of the model is that migrating NCCs co-develop and closely interact with a complex vascular plexus as found in the embryo (George et al., 2016). Moreover, the developing sensory ganglia are highly vascularized as also observed in vivo (Jimenez-Andrade et al., 2008). Finally, peripheral nerve fibers are getting in close contact with the developing blood vessels. This allows an interaction of migrating NCCs, sensory neuroblasts, and neurons with endothelial as well as peri-endothelial cells of the vascular plexus. Such neurovascular interactions have been discussed to be involved in developmental processes such as arterial specification and vessel branching (Mukouyama et al., 2002) or axonal guidance (Makita et al., 2008). Moreover, an interaction between endothelial cells and sensory neuroblasts regulates both their quiescence and differentiation behavior, e.g., via endothelial-neuroblast cytoneme contacts and Dll4-Notch signaling (Taberner et al., 2020). Finally, SOX10+ NCCs have been demonstrated to contribute to vascular development in multiple organs (Wang et al., 2017). For that reason, the presented assembloid model is a promising platform to study such neurovascular interactions in more detail directly in the human tissue context.

In the future, additional studies screening for more markers of early NCC development such as SNAIL1/2, TWIST1, FOXD3, SOX9, and ETS1 and the exact timing of their expression need to be performed to test whether the presented assembloid resembles the in vivo situation in every detail. Moreover, it will be interesting to characterize the exact sensory neuron subtype composition within peripheral ganglia and to analyze if neuronal subtype formation occurs in different waves like in the embryo (Marmigere and Ernfors, 2007). For this reason, it will be important to screen for the expression of marker genes such as NTRK1, NTRK2, and NTRK3 identifying nociceptors, mechanoreceptors, and proprioceptors (Saito-Diaz et al., 2021) and the exact timing of their expression. It will be further important to stain tissue sections for these markers to determine the abundancy and localization of NTRK1-, NTRK2-, and NTRK3-positive cells. In addition, we need to mention, that we only used PRPH as a specific marker to identify peripheral neurons. However, not all sensory neurons within peripheral ganglia express PRPH (Goldstein et al., 1991).

In summary, we think that the presented assembloid model will be useful to uncover mechanisms of human NCC induction, delamination, migration, and PNS development and can be utilized for toxicity screenings and drug testing. Finally, the assembloid allows us to investigate the crosstalk between neuroectoderm and mesoderm and between peripheral neurons/neuroblasts and endothelial cells.

Experimental procedures

Resource availability

Corresponding author

Requests for further information or more detailed protocols should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the corresponding author, Philipp Wörsdörfer (philipp.woersdoerfer@uni-wuerzburg.de).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Cell culture and neuro-mesodermal assembloid formation

To generate neuro-mesodermal assembloids, human foreskin-derived iPSCs (STEMCCA NHDF iPSCs and Sendai NHDF iPSCs) were used as previously described (Worsdorfer et al., 2019). iPS cells are cultured on human ESC Matrigel (Corning)-coated six-well plates in StemMACS iPS Brew XF (human) medium (Miltenyi Biotec) supplemented with 10 mM ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (Miltenyi Biotec) until they reach a confluency of 80%. Subsequently, cells are dissociated by using StemProAccutase cell detachment solution (Gibco/Life Technologies) and gentle pipetting.

For the induction of both neural and mesodermal organoids, cells are resuspended in StemMACS iPS Brew medium supplemented with 10 mM ROCK inhibitor Y-27632, and 4 x 103 cells (in 100 μL medium) are seeded per well of a 96-well plate. The 96 wells were previously coated with 1% Agarose (Biozym) to keep cells in suspension. Cells are cultured for 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator to allow aggregation.

To induce neural differentiation, iPSC aggregates are cultured in neural induction medium 1 (NIM1) (neurobasal medium [Gibco] 50%, DMEM-F12 [Gibco] 50%, B27 without vitamin A [Gibco] 1 x, N2-Supplement [Gibco] 1 x, L-glutamine [Gibco] 2 mM, CHIR 99210 [Sigma-Aldrich] 3 μM, SB431542 [Miltenyi Biotec] 10 μM, dorsomorphin [Tocris] 1 μM, purmorphamine [Miltenyi Biotec] 0.5 μM) for 48 h. Subsequently the medium is changed to neural induction medium 2 (NIM2) (neurobasal medium 50%, DMEM-F12 50%, B27 without vitamin A 1 x, N2-Supplement 1 x, L-glutamine 2 mM, CHIR 99210 3 μM, ascorbic acid [Sigma-Aldrich] 0.06 mg/mL [355 μM], purmorphamine 0.5 μM) for 72 h. After the induction phase, medium is changed to neural differentiation medium (NDM) (neurobasal medium 50%, DMEM-F12 50%, B27 without vitamin A 1 x, N2-Supplement 1 x, L-glutamine 2 mM, ascorbic acid 0.06 mg/mL [355 μM], penicillin/streptomycin [Sigma-Aldich] 1 x) for 24 h.

For mesodermal induction, iPSC aggregates are cultured in mesoderm differentiation medium (Advanced DMEM-F12 [Gibco] 100%, L-glutamine 2 mM, ascorbic acid 0.06 mg/mL [355 μM], CHIR 99210 10 μM, BMP4 [Pepro Tech] 25 ng/mL) for 72 h.

Finally, a single neural and a single mesodermal aggregate per well of a agarose-coated 96-well plate are brought in co-culture to allow assembloid formation. Neuro-mesodermal assembloids are kept in suspension culture in NDM for up to 40 days for 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator.

Retinoic acid treatment

RA (Sigma-Aldrich) is dissolved in DMSO (Carl Roth), and assembloids are treated with a final concentration of 1 μM RA in cell culture medium. Treatment starts at day 4 of neural organoid differentiation, and fresh RA-containing medium is added every other day. Assembloids are treated with RA either for 7 days or 15 days. For the DMSO control, assembloids are treated with the corresponding amount of DMSO for 15 days.

For quantitative RT-PCR analysis, RNA of 30-day-old assembloids is extracted by using the Direct-Zol RNA MiniPrep Plus Kit (Zymo Research) following manufacturer’s instructions. Complementary DNA is prepared by using GoScript Reverse Transcriptase (Promega). Quantitative PCR analyses are conducted using the GoTaq Q-PCR Master Mix (Promega) and a StepOnePlus Real-Time QPCR thermocycler (Applied Biosystems).

The following primer pairs were used:

GAPDH: FW 5′-TGACAACTTTGGTATCGTGGA-3′ and RV 5′-CCAGTAGAGGCAGGGATGAT-3′,

SOX10: FW 5′-CCTCACAGATCGCCTACACC-3′ and RV 5′ -CATATAGGAGAAGGCCGAGTAGA-3′.

Immunofluorescence analyses

Co-cultured organoids are fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight and subsequently washed with PBS (Sigma-Aldrich). Afterward, 5-μm paraffin (Merck) sections are prepared. For immunofluorescence analyses, sections are deparaffinized, rehydrated, and unmasked using sodium citrate buffer (10 mM, pH 6). Primary antibodies to TUJ1 (Biozol, 801202), CD31 (DAKO, M0823), SOX10 (R&D Systems, AF2864), PRPH (Merck-Millipore, AB1530), TFAP2 (DSHB, 3B5), ISL1 (DSHB), GAP43 (Novos Biology, NB300-143), TH (Abcam, AB112), and BRN3a (Santa Cruz, SC-8429) are diluted in NBS blocking solution and incubated overnight at 4°C. Secondary Cy2-, Cy3-, or Cy5-labeled antibodies (Dianova) diluted in PBS are used to visualize primary antibodies. Secondary antibodies are incubated for 1 h at room temperature. To highlight the tissue structure, paraffin sections are further H&E stained utilizing Eosin y-solution (AppliChem) and Gill’s Hematoxylin solution (Chroma). Images are taken using an Axiovert 40 CFL microscope (Zeiss) and an Eclipse Ti confocal laser scanning microscope (Nikon).

Whole-mount staining and tissue clearing

For tissue clearing, the organoids are fixed in 4% PFA in PBS overnight at 4°C. Afterward, organoids are washed thrice 30 min in PBS. Subsequently, organoids are incubated in an ascending MeOH (Sigma-Aldrich) series (30 min 50% MeOH in PBS, 30 min 80% MeOH in PBS, twice 30 min 100% MeOH) and washed twice 30 min in 20% DMSO (Carl Roth) in MeOH. Next, a descending MeOH series follows (30 min 80% MeOH in PBS, 30 min 50% MeOH in PBS, 30 min PBS). Subsequently, specimens are incubated twice 30 min in 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS and kept in penetration buffer (PBS, 0.2% Triton X-100, 0.3 M glycine [Carl Roth], 20% DMSO) at 37°C overnight. After that, organoids are incubated in blocking solution (PBS, 0.2% Triton X-100, 0.3 M glycine, 6% BSA, 10% DMSO) overnight at 37°C. For the staining process, organoids are washed two times for 1 h in washing buffer (0.2% Tween 20 [ApplyChem] in PBS) and afterward incubated with primary antibodies in blocking buffer (PBS, 20% Tween 20, 4% BSA, 5% DMSO) for 24 h at 37°C. The following primary antibodies are used: CD31 (DAKO, M0823), SOX10 (R&D Systems, AF2864), and PRPH (Merck-Millipore, AB1530). The organoids are then washed twice for 30 min in washing buffer and afterward incubated with secondary antibodies overnight at 37°C in blocking solution. Finally, organoids are washed thrice 30 min in washing buffer and dehydrated in an ascending MeOH series (thrice 30 min in 50% MeOH in PBS, thrice 30 min in 80% MeOH in PBS and thrice 30 min in 100% MeOH). For tissue clearing, samples are incubated in ethyl cinnamate (Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 h at 37°C.

Transmission electron microscopy

Organoids are fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 4% PFA in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (50 mM cacodylate, 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.2) on ice for 2 h and washed four times with 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, 5 min each. Organoids are subsequently fixed for 60 min with 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer and washed two times in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, 10 min each. After washing with bidistilled water, organoids are dehydrated in an ascending EtOH series using solutions of 30%, 50%, and 70% EtOH, 10 min each. Organoids are contrasted with 2% uranyl acetate in 70% EtOH for 60 min and subsequently dehydrated using an EtOH array of 70%, 80%, 90%, and 96% and two times 100% for 10 min each. Subsequently, organoids are incubated in propylene oxide (PO) two times for 30 min before incubation in a mixture of PO and Epon812 (1:1) overnight. The following day, samples are incubated in pure Epon for 2 h and embedded by polymerizing Epon at 60°C for 48 h.

Specimens are cut using an ultramicrotome, collected on nickel grids, and post-stained with 2.5% uranyl acetate and 0.2% lead citrate. Finally, specimens are analyzed using a LEO AB 912 transmission electron microscope (Zeiss).

Semiquantitative RT-PCR analyses

For semiquantitative RT-PCR analyses, RNA is extracted by using the Direct-Zol RNA MiniPrep Plus Kit (Zymo Research). To generate cDNA, the GoScript Reverse Transcriptase (Promega) is used as described in the manufacturer’s protocol. The polymerase chain reaction is performed using the Red MasterMix (2x) Taq PCR MasterMix (Genaxxon) using the following primer pairs:

POU4F1: FW 5′-GGGCAAGAGCCATCCTTTCAA-3′ and RV 5′-CTGTTCATCGTGTGGTACGTG-3′,

GAPDH: FW 5′-TGACAACTTTGGTATCGTGGA-3′ and RV 5′-CCAGTAGAGGCAGGGATGAT-3′,

ISL1: FW 5′-GCGGAGTGTAATCAGTATTTGGA-3′ and RV 5′-GCATTTGATCCCGTACAACCT-3′,

PRPH: FW 5′-GCCTGGAACTAGAGCGCAAG-3′ and RV 5′-CCTCGCACGTTAGACTCTGG-3′,

PHOX2b: 5′-AACCCGATAAGGACCACTTTTG-3′ and RV 5′-AGAGTTTGTAAGGAACTGCGG-3′,

SOX10: FW 5′-CCTCACAGATCGCCTACACC-3′ and RV 5′-CATATAGGAGAAGGCCGAGTAGA-3′,

TFAP2: FW 5′-AGGTCAATCTCCCTACACGAG-3′ and RV 5′-GGAGTAAGGATCTTGCGACTGG-3′,

TH: FW 5′-GGAAGGCCGTGCTAAACCT-3′ and RV 5′-GGATTTTGGCTTCAAACGTCTC-3′.

Calcium imaging

Calcium imaging is performed on organoids glued to a cover slip using 20 μL human ESC Matrigel. Organoids are loaded with 1 μM Fluo4-AM (Gibco) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Subsequently, organoids are washed with PBS and kept in culture medium. To test the functionality of sensory ganglia, capsaicin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), dissolved in chloro-form, is added to culture medium to a final concentration of 1 μM. A video of the dynamic fluorescence changes is recorded using a Leica DM IL LED microscope equipped with an external light source for fluorescence excitation (Leica EL6000) and a Leica DFC450C camera. Quantification and data analysis are performed using ImageJ (Fiji) and Microsoft Excel.

Chick chorioallantoic membrane assay

Fertilized chicken eggs are incubated at 37 °C at a humidity of 60%. After 5 days of incubation, assembloids are transplanted on the CAM of the developing chicken embryo. For transplantation, assembloids are attached to a round nylon mesh (diameter of approximately 5 mm; 150 μm grid size, 50% open surface, 62 μm string diameter, 35 g/m2, PAS2, Hartenstein) with 10 μL Matrigel. After gelling at 37°C, the mesh is placed upside down on the CAM. After 5–10 days, the mesh with the organoids is carefully explanted, washed in PBS, and fixed for 1 h in 4% PFA. Subsequently, 5-μm paraffin sections are prepared and processed for immunofluorescence analyses as described above. All procedures comply with the regulations covering animal experimentation within the EU (European Communities Council DIRECTIVE, 2010/63/EU). They are conducted in accordance with the animal care and use guidelines of the University of Würzburg.

Author contributions

P.W. conceived the study and designed experiments; A.F.R., P.S., and P.W. conducted experiments; N.W. performed electron microscopic analyses; S.E. acquired funding and provided feedback and expertise; A.F.R. and P.W. wrote the manuscript and performed final approval. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Doris Dettelbacher-Weber, Martina Gebhardt, Erna Kleinschroth, Karin Reinfurt-Gehm, Ursula Roth, Sieglinde Schenk, Elke Varin, and Lisa Wittstatt for excellent technical assistance and all members of the Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Group for their support. This work was supported by grants of the IZKF Würzburg (Interdisziplinäres Zentrum für Klinische Forschung der Universität Würzburg) (project E-D-410) to P.W. and the German Research Foundation (DFG) by the Collaborative Research Center TRR225-B04 to S.E. This publication was supported by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Wuerzburg. The graphical abstract was produced by combining own drawings with graphics taken from the image bank of Servier Medical Art (www.servier.com) licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0). Excerpts of the original images were used, and color was edited.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Published: April 20, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2023.03.012.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

Raw data and images are available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

- Brumovsky P., Villar M.J., Hokfelt T. Tyrosine hydroxylase is expressed in a subpopulation of small dorsal root ganglion neurons in the adult mouse. Exp. Neurol. 2006;200:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina M.J., Schumacher M.A., Tominaga M., Rosen T.A., Levine J.D., Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerrizuela S., Vega-Lopez G.A., Aybar M.J. The role of teratogens in neural crest development. Birth Defects Res. 2020;112:584–632. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohlan S.Q. Excessive intake of vitamin A as a cause of congenital anomalies in the rat. Science. 1953;117:535–536. doi: 10.1126/science.117.3046.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykes I.M., Tempest L., Lee S.I., Turner E.E. Brn3a and Islet1 act epistatically to regulate the gene expression program of sensory differentiation. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:9789–9799. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0901-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escurat M., Djabali K., Gumpel M., Gros F., Portier M.M. Differential expression of two neuronal intermediate-filament proteins, peripherin and the low-molecular-mass neurofilament protein (NF-L), during the development of the rat. J. Neurosci. 1990;10:764–784. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-03-00764.1990. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2108230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etchevers H.C., Dupin E., Le Douarin N.M. The diverse neural crest: from embryology to human pathology. Development. 2019;146:dev169821. doi: 10.1242/dev.169821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustino Martins J.M., Fischer C., Urzi A., Vidal R., Kunz S., Ruffault P.L., Kabuss L., Hube I., Gazzerro E., Birchmeier C., Gouti M. Self-organizing 3D human trunk neuromuscular organoids. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;26:172–186.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George L., Dunkel H., Hunnicutt B.J., Filla M., Little C., Lansford R., Lefcort F. In vivo time-lapse imaging reveals extensive neural crest and endothelial cell interactions during neural crest migration and formation of the dorsal root and sympathetic ganglia. Dev. Biol. 2016;413:70–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervasi N.M., Scott S.S., Aschrafi A., Gale J., Vohra S.N., MacGibeny M.A., Kar A.N., Gioio A.E., Kaplan B.B. The local expression and trafficking of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA in the axons of sympathetic neurons. RNA. 2016;22:883–895. doi: 10.1261/rna.053272.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein M.E., House S.B., Gainer H. NF-L and peripherin immunoreactivities define distinct classes of rat sensory ganglion cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 1991;30:92–104. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490300111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan K.A., Ambler C.A., Chapman D.L., Bautch V.L. The neural tube patterns vessels developmentally using the VEGF signaling pathway. Development. 2004;131:1503–1513. doi: 10.1242/dev.01039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Andrade J.M., Herrera M.B., Ghilardi J.R., Vardanyan M., Melemedjian O.K., Mantyh P.W. Vascularization of the dorsal root ganglia and peripheral nerve of the mouse: implications for chemical-induced peripheral sensory neuropathies. Mol. Pain. 2008;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahane N., Kalcheim C. From bipotent neuromesodermal progenitors to neural-mesodermal interactions during embryonic development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:9141. doi: 10.3390/ijms22179141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley K.W., Pașca S.P. Human brain organogenesis: toward a cellular understanding of development and disease. Cell. 2022;185:42–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.S., Lee J., Lee D.Y., Kim Y.D., Kim J.Y., Lim H.J., Lim S., Cho Y.S. Schwann cell precursors from human pluripotent stem cells as a potential therapeutic target for myelin repair. Stem Cell Rep. 2017;8:1714–1726. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Koo B.K., Knoblich J.A. Human organoids: model systems for human biology and medicine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020;21:571–584. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0259-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai X., Liu J., Zou Z., Wang Y., Wang Y., Liu X., Huang W., Ma Y., Chen Q., Li F., Jiang B. SOX10 ablation severely impairs the generation of postmigratory neural crest from human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:814. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-04099-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makita T., Sucov H.M., Gariepy C.E., Yanagisawa M., Ginty D.D. Endothelins are vascular-derived axonal guidance cues for developing sympathetic neurons. Nature. 2008;452:759–763. doi: 10.1038/nature06859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmigère F., Ernfors P. Specification and connectivity of neuronal subtypes in the sensory lineage. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:114–127. doi: 10.1038/nrn2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda S., Kobayashi N., Mominoki K., Wakisaka H., Mori M., Murakami S. Morphological transformation of sensory ganglion neurons and satellite cells. Kaibogaku Zasshi. 1998;73:603–613. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9990197 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales J.S., Raspopovic J., Marcon L. From embryos to embryoids: how external signals and self-organization drive embryonic development. Stem Cell Rep. 2021;16:1039–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2021.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukouyama Y.S., Shin D., Britsch S., Taniguchi M., Anderson D.J. Sensory nerves determine the pattern of arterial differentiation and blood vessel branching in the skin. Cell. 2002;109:693–705. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00757-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmsted Z.T., Paluh J.L. Co-development of central and peripheral neurons with trunk mesendoderm in human elongating multi-lineage organized gastruloids. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:3020. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23294-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira J.D., DuBreuil D.M., Devlin A.C., Held A., Sapir Y., Berezovski E., Hawrot J., Dorfman K., Chander V., Wainger B.J. Human sensorimotor organoids derived from healthy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis stem cells form neuromuscular junctions. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:4744. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24776-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A., Muir A.R. The relationship between axons and Schwann cells during development of peripheral nerves in the rat. Q. J. Exp. Physiol. Cogn. Med. Sci. 1959;44:117–130. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1959.sp001366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt P., Glatza M., Hemmer K., Tsytsyura Y., Thiel C.S., Höing S., Moritz S., Parga J.A., Wagner L., Bruder J.M., Sterneckert J. Derivation and expansion using only small molecules of human neural progenitors for neurodegenerative disease modeling. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito-Diaz K., Street J.R., Ulrichs H., Zeltner N. Derivation of peripheral nociceptive, mechanoreceptive, and proprioceptive sensory neurons from the same culture of human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2021;16:446–457. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2021.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S., Alt Y., Deoghare N., Krüger S., Kern A., Rockel A.F., Wagner N., Ergün S., Wörsdörfer P. A blood vessel organoid model recapitulating aspects of vasculogenesis, angiogenesis and vessel wall maturation. Organoids. 2022;1:41–53. doi: 10.3390/organoids1010005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Solomon E., Boehm E., Kuruvilla R. The sympathetic nervous system in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2021;22:685–702. doi: 10.1038/s41583-021-00523-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taberner L., Bañón A., Alsina B. Sensory neuroblast quiescence depends on vascular cytoneme contacts and sensory neuronal differentiation requires initiation of blood flow. Cell Rep. 2020;32:107903. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thor S., Ericson J., Brännström T., Edlund T. The homeodomain LIM protein Isl-1 is expressed in subsets of neurons and endocrine cells in the adult rat. Neuron. 1991;7:881–889. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90334-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Wu F., Yuan H., Wang A., Kang G.J., Truong T., Chen L., McCallion A.S., Gong X., Li S. Sox10(+) cells contribute to vascular development in multiple organs-brief report. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017;37:1727–1731. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wörsdörfer P., Dalda N., Kern A., Krüger S., Wagner N., Kwok C.K., Henke E., Ergün S., Ergun S. Generation of complex human organoid models including vascular networks by incorporation of mesodermal progenitor cells. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:15663. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52204-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wörsdörfer P., Rockel A., Alt Y., Kern A., Ergün S. Generation of vascularized neural organoids by Co-culturing with mesodermal progenitor cells. STAR Protoc. 2020;1:100041. doi: 10.1016/j.xpro.2020.100041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao D., Deng Q., Guo Y., Huang X., Zou M., Zhong J., Rao P., Xu Z., Liu Y., Hu Y., Xiang M. Generation of self-organized sensory ganglion organoids and retinal ganglion cells from fibroblasts. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eaaz5858. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz5858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalc A., Sinha R., Gulati G.S., Wesche D.J., Daszczuk P., Swigut T., Weissman I.L., Wysocka J. Reactivation of the pluripotency program precedes formation of the cranial neural crest. Science. 2021;371:eabb4776. doi: 10.1126/science.abb4776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The movie shows a large sensory ganglion at the neuro-mesodermal interface. Peripheral neurons (green) were detected using specific Peripherin antibody. Neural crest cells and derivates were detected using a SOX10 antibody (red). Nuclei are stained with DAPI. The movie shows a 3D reconstruction from a z stack of confocal images taken by laser scanning microscopy.

The movie shows a hierarchically organized network of blood vessels (red) and peripheral nerve fiber bundles (green) in the mesodermal part of the assembloid. Peripheral neurons were detected using specific peripherin antibody. Blood vessels were detected using a CD31 antibody. The movie shows a 3D reconstruction from a z stack of confocal images taken by laser scanning microscopy.

The movie shows a calcium imaging experiment (left side). The intracellular calcium levels were visualized using Fluo4-AM. Calcium levels rise in response to capsaicin treatment. Video plays at 8x speed. After calcium imaging, the assembloid was fixed and whole-mount stained using specific antibodies targeted against peripherin (green) and SOX10 (red) to visualize the position of the peripheral ganglion (right side).

Data Availability Statement

Raw data and images are available upon request to the corresponding author.