Abstract

This paper examines corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the role government can play in promoting CSR. Corporations are an integral part of the large economy of any given society or country whereby these corporations operate. The government’s role is critical in promoting CSR activities or agendas because CSR is voluntary without mandatory legislation. The method used in this paper is a normative literature review and secondary data procedures. The research results show the need for developed and developing countries to share CSR’s best practices and build human institutions capable of enhancing CSR agendas by creating awareness, soft laws, partnering, and mandating business enterprises to be transparent in solving society’s problems wherever they operate. Governments in some developed nations have taken a far-reaching agenda in promoting CSR, especially the UK, European Union, the USA, and other developing countries in East Asia. However, developing countries are lagging behind in developing CSR agendas but should not simply copy from developed countries but adopt CSR’s agenda susceptive to their multiple nations’ sustainable and equitable developments. The result also shows that the lack of good governance and transparency in abundant natural resources in developing countries in the south has led to corrupt elites diverting CSR activities funds for their self-interest and not their local communities. Some developing countries still see CSR as an act of philanthropy, not as means for sustainable and equitable development for economic growth, hence the lack of transparency surrounding CSR by the various government and their elites.

Keywords: Corporate social responsibility (CSR), Role of government, Government, Society, Transparency, Good governance

Introduction

The principle of corporate social responsibility (CSR) is one of the concepts used by business corporations to contribute to various communities and societies wherever they operate voluntarily without any mandatory legislation. CSR is an emerging concept that is gaining popularity all over business organizations. CSR also refers to companies taking account of the social and environment, not just the financial consequences of their actions. United Nations Industrial Development Organization UNIDO (2022) sees CSR as being the way through which a company achieves a balance of economic, environmental, and social imperatives (“Triple-Bottom-Line-Approach”) while at the same time addressing the expectations of shareholders and stakeholders. CSR is a voluntary act of cooperation. CSR should fulfill the social responsibility of advancing the social well-being of those where they are operating. The World Bank Group (2004) acknowledges that the modern corporate social responsibility (CSR) agenda is evidence that businesses are a part of society and contribute positively to societal goals and aspirations. CSR is fundamentally a process of managing the costs and benefits of business activity to internal and external stakeholders, ranging from employees, shareholders, and investors to customers, suppliers, civil society, and community groups. According to the European Commission (2006), the role of government concerning CSR agenda is vital, even though CS agenda or activities are based on the voluntary action by companies and as an instrument for accountability and responsibility. Thus, the role of governments in promoting and developing CSR in developed and developing countries is vital to ensure effective well-being for all through collaboration, although CSR is voluntary. The recent COVID-19 pandemic is a wake-up call for both developed and developing countries to collaborate. To this effect, He and Harries (2020) argue that the uncertainty triggered by COVID-19 has caught the entire world off guard – radically changing the way the world is perceived – and is likely to have an impact on CSR in years to come. Bapuji et al. (2020) also acknowledged that the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have prompted the private sector to respond to this challenge through its CSR actions, integrating environmental and social aspects into its business activities, avoiding unethical practices, such as price increases, thus testing companies’ ethical commitment. To this effect, Idemudia (2009) argues that the community is the best neighbor of a company, and they are both interconnected. Businesses and communities are partners with mutual interests based on the win–win approach. Boadi et al. (2019) also attest to the fact that communities offer firms social licenses to operate their business operations in society. We have seen a lot of efforts by many corporations coming to the aid of a people divested by natural disasters—for example, the Asian Tsunami and the Ebola crisis in Africa. Droppert and Bennett (2015) also attest to the fact that many companies are responding to various epidemiological and demographic shifts such as HIV/AIDS, Middle East Reparatory Syndrome (MERS), Severe Acute Reparatory Syndrome (SARS), and Ebola in Africa, more importantly, the current pandemic COVID-19 which indicate the role some corporation has played in making sure that the pandemic is confronted and be eradicated. Droppert and Bennett (2015) further argue that due to increasing pressure from civil society to act as a socially responsible organization, companies worldwide are reforming and expanding their CSR strategies to fit them with the dynamic world. According to Mahmud et al. (2020), CSR is treated as an excellent tool for accomplishing sustainable development by offering a win–win strategy. No business can survive by using a win-lose strategy. Thus, the influence of corporations in our communities and societies at large is unquestionable and commendable. Hence, the World Bank Group developed good practices to be flowered by developing countries with regards to CSR to enhance the collaborative approach between the developed and developing countries since most of the corporations dealing with gas and oil explorations and forestry products originated from the north and also because we are in it together. A study by Sindakis and Minhas argues that collaboration requires interaction between participatory parties. Therefore, the government in developed and developing countries need to interact to share the best practices for CSR. Hence, the government’s role in promoting CSR needs support to ensure that rules, responsibilities, and accountabilities are taken seriously, although CSR is a voluntary instrument by businesses with no mandatory legislation. The government can ensure that corporations work according to the rules and norms of each nation or society. Governments can legislate, foster, partner with businesses, and endorse good practices to facilitate CSR development. Tang et al. argue that the government plays a direct role in promoting CSR implementation. Zueva and Fairbrass (2021) also argue that there is a growing body of literature that shows that national governments around the world are promoting CSR through a variety of practices (Albareda et al., 2007, 2008; González & Martinez, 2004; Podsiadlowski & Reichel, 2014; Rossouw, 2005; Vallentin 2015; Waagstein, 2011). For Zueva and Fairbrass (2021), academics and practitioners (as well as society in general) widely regard governments as the key societal actors capable of compelling businesses to practice corporate social responsibility (CSR).

The UK government is one of the pioneering countries in promoting the role of government in promoting CSR. Their CSR activities impacted the economy, society, and environment in enhancing sustainability (DTI, 2004). Thus, the role of government in promoting CSR is vital and should be encouraged and developed further. UK government created a minister of state responsible for CSR. The argument advanced by ) that the social responsibility of a company is to increase its profit has served its time, and the world has moved on since then.

The Background of the Study

The background on CSR stems from the fact that since time immemorial, businesses or companies have always used CSR to give back to society while strengthening the brand reputation whereby they operate. The evidence of business concerns giving back to society date back to the history of the industrial revolution and the need to solve social problems of poverty which lead to philanthropy.

The aim and objective of the paper are to examine corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the role of governments in promoting CSR in both developed and developing countries. CSR activities can create goodwill in the societies they operate, improve public perception of the enterprise, and foster some positive attitudes toward the company. Most corporations operating in developing countries are western and are required to share best practices of CSR with these countries in order to improve some social issues that may elevate poverty in developing countries. Thus, the significance of this paper is to shed light on CSR as practiced in developed countries so that developing countries can learn from the best practices in implementing CSR activities and the role governments play in promoting CSR as a means of continuous improvement.

We live in a world whereby governments, particularly businesses and civil societies, cannot do everything alone without others. The above discussion and arguments are only possible in the words of Coming (2020), and together, we will get through this; Kigo also argues that the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us an important lesson about ourselves as a human community: We are interconnected with and interdependent each other in ways we did not fully understand before. My health and well-being are dependent on your health and well-being, and the same principle applies beyond borders and regions. Thus, CSR principles, activities, or agendas and the role played by the government are vital for economic growth and development in any given community or society, and sharing the best practices of CSR by developed and developing countries is vital for the growth and development of mankind. Collaboration and sharing of good practices of CSR are great for both developed and developing nations. Thus, what is CSR?

Definitions of CSR

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has multiple meanings. CSR is a complex idea and can correlate with several values. CSR is also related to the corporate environment and the environment or community it operates. CSR is considered philanthropic behavior toward society. Bowen defines CSR as “the duty of entrepreneurs to follow these policies, to make those decisions, or to follow those lines of action that are desirable in terms of our society’s goals and values.” Davis (1973) also describes CSR as the consideration of problems outside the company’s restricted financial, technological, and legal requirements. On the other hand, Carroll describes CSR as “an economic, legal, ethical and discretionary expectation (philanthropic).” On the other hand, some studies have tried to define CSR in terms of stakeholder and social perspectives. The stakeholder perspective of CSR is based on Freeman’s (1984) argument that businesses have responsibilities for groups and individuals who can both influence and be influenced by business operations. For him, the major social responsibilities of corporations consist of community service, the improvement of relationships with employees, job creation, environmental protection, and financial returns. Hopkins (2003), who is of the stakeholder perspective, argues that CSR is to treat a company’s stakeholders morally and responsibly to attain the two-fold goal of maintaining profit and improving the living standard of stakeholders inside and outside the company.

The social perspective of CSR is reflected in Kotler’s (1991) definition of CSR as a means of running a firm to maintain and improve social well-being. Mohr et al. (2001) also reflect the social perspective when they define CSR as the commitment made by a company to remove or reduce its adverse impact on society and boost the long-term beneficial influence on society. The social perspective addresses societal issues at the core of CSR. In other words, CSR policies reflect their responsibilities to advance social interests, while the stakeholder’s perspective profits at the forefront of CSR. Carroll (1979a, b) emphasized that a company’s social responsibility covers the discretionary, ethical, legal, and economic expectations that humanity has of organizations at a particular time. Carroll framed a pyramid of CSR in trying to explore the nature of CSR and examine its parts, especially for the executive who wish to reconcile their obligations to their shareholders with those other competing groups claiming legitimacy philanthropic requirements: donation, gifts, helping the poor. It ensures goodwill and social welfare. Ethical responsibility: Follow moral and ethical values to deal with all the stakeholders. Economic responsibility: Maximize the shareholders’ value by paying a good return. Legal responsibility: Abide the laws of the land.

Nazari et al. (2012) also define CSR as having four social responsibilities of a company: economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibility. Ali and Lasmono view CSR as having four responsibilities: ethical, economic, philanthropic, and legal perspective. The World Bank (2004) defines CSR as the commitment of business to contribute to sustainable economic development—working with employees, their families, the local community, and society to improve the quality of life in ways that are both good for business and business good for development. According to European Commission (2001, 2002, 2006), corporate social responsibility (CSR) “is a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and their interaction with their stakeholders voluntarily.” EC (ibid) acknowledged that CSR enterprises are deciding to go beyond minimum legal requirements and obligations stemming from collective agreements to address societal needs; hence, CSR enterprises of all sizes, in cooperation with their stakeholders, can help to reconcile economic, social, and environmental ambitions. Thus, CSR has become an increasingly important concept globally and within the EU. For EC (ibid), the promotion of CSR reflects the need to defend shared values and increase the sense of solidarity and cohesion. Carroll (2016) presents a four-part concept structure known as the economic obligation, the legal obligation, the ethical responsibility, and the philanthropic responsibility required by society. Furthermore, Carroll (1979a, b) viewed CSR as policies and procedures adopted by the company to ensure that shareholders are recognized and covered in their strategies and operations by society or stakeholders. Hence, CSR activities and actions should be purely voluntary and considered a social responsibility. Meanwhile, McWilliams and Siegel define CSR as actions that appear to further some social good beyond the interests of the firm and that which is required by law. For them, this definition underscores to them that CSR means going beyond obeying the law. On the other hand, Jason defines CSR as a self-regulating business model that helps a company to be socially accountable – to itself, its stakeholders, and the public. Ollong (2014) defined CSR as the relationship between business and society, where the role of business is purported to go beyond the provision of goods and services. The European Commission (EC, 2011) defines CSR as “business accountability for its effect on society and what a business can do to fulfill that accountability.” EC (2006) defines CSR as “a term through which companies voluntarily incorporate social and environmental issues into their business activities.” Their relationship with their stakeholders. Smith (2001) defines CSR as “the obligations of the firm to its shareholders – people affected by corporate policy practices. These obligations go beyond the legal requirements and duties of a firm to its shareholders. Thus, the fulfillment of these obligations is to minimize any harm and maximize the long-run beneficial impact on the firm in the society.” Subsequently, Lantos (2001) also defines CSR as “an imperative responsibility steaming from the implicit social contract between company and society for businesses to respond to long-term needs and to maximize the positive impact on society.” Here are some of the best practices of CSR: (1) set a feasible, viable, and measurable goal, (2) build a lasting relationship with the community, (3) retain the community’s core values, (4) assess the impact of CSR, (5) report the impact, and (6) create community awareness.

Scholars such as McWilliam and Siegel see CSR as the corporation’s interest and its stakeholders, such as workers, civil society groups, customers, and the government, to demand that CSR’s principles and efforts are applied. The World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD, 1999) defines CSR as a commitment by a company to behave ethically and contribute to economic development while improving the quality of life of its workforce and family members, as well as the local community at large. On the other hand, the EC commission (2001) defines CSR as a definition by which businesses voluntarily decide to enhance society and a healthier climate in the context of the green paper. In subsequent years, in their communication number 681 (2011), the European legislators return to this topic of CSR, describing CSR as the responsibility of companies for their effect on society. The UK government, on the other hand, accepted a higher commercial interest responsibility for the private sector in 2001.

Crane et al. (2008) define CSR as a set of company values such as follows: (1) voluntary activities that go beyond those prescribed by law; (2) internalizing or managing negative externalities, for example, a reduction in pollution; (3) multiple stakeholder orientation and not only focusing on shareholders; (4) alignment of social and economic responsibilities to maximize the company’s profitability; (5) practices and values about why they do it; and (6) more than philanthropy alone.

Van der Heijden et al. (2010) argue that CSR is a search process that requires company leaders to develop their organization-specific balance between people, planet, and profit. These values, dimensions, and search processes have to be incorporated into organizational policies and accepted by employees to function. Some view the voluntary statutes of CSR as not going far as having mandatory legislation. To this effect, Fox (2004) cited Ward’s (2004, 3) argument, which shows that CSR is an enterprises’ contribution (both positive and negative) to sustainable development. Hence, The World Bank’s working definition which views CSR as the commitment of business to contribute to sustainable economic development, working with employees, their families, the local community, and society at large to improve the quality of life in ways that are both good for business and good for development. Fox (2004) concluded that the new CSR agenda fail to fulfill its potential contribution to development because it is voluntary business activities dominated by actors from the north, and it all focuses on the large enterprise. For him, there is a need for a more balanced and pragmatic approach that recognizes a business case for the responsibility which are in line with the development priorities and, at the same time, creates an enabling environment for responsible business in the south, building human and institutional capacity to generate agenda for development needs. For Fox (2004), the CSR agenda should be built around the core principles of sustainable and equitable development. For United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) 2022, the key CSR issues are environmental management, eco-efficiency, responsible sourcing, stakeholder engagement, labor standards, and working conditions, employee and community relations, social equity, gender balance, human rights, good governance, and anti-corruption measures. Thus, a properly implemented CSR concept can bring along a variety of competitive advantages, such as enhanced access to capital and markets, increased sales and profits, operational cost savings, improved productivity and quality, efficient human resource base, improved brand image and reputation, enhanced customer loyalty, better decision making, and risk management processes. Some scholars are critical of CSR and see it as a smokescreen for deregulation and a window dressing for reckless conduct. For Boctanski, CSR is one of the least nuanced attempts to disguise its rising control over social life created by management-created supremacy, and for ), a firm’s only responsibility is to do business and make a profit.

The Role of Government in CSR promotion

The interest of governments in promoting CSR is not new because business objectives cannot be done in any given society without government involvement, either voluntarily or legally. The government has a stake in making sure that CSR objectives are well-coordinated.

In a study conducted in the United Kingdom by Moon (2004), the state’s position in promoting CSR is due to social governance deficits reflecting satellite and marketplace vulnerabilities, and ongoing and evolving societal demands are making government-recognized CSR contributions in the UK. Moon (2004) further illustrated that the effort of the UK government to institutionalize CSR was due to the realization of the government that it could not provide all the solutions to its society in the inner cities and therefore wanted the private sector to play a pivotal role. The UK government has since seen the importance of CSR and appointed a minister designated to CSR.

The speech by the then Prime Minister of Britain, Gorden Brown, cited by Moon (2004), illustrates the importance of CSR in the UK. The speech by the then Prime Minister of Britain Gorden Brown (Moon, 2004) highlights the relevance of in the UK of CSR as he asserts that “Today, corporate social responsibility goes far beyond the old philanthropy of the past, by giving money for good causes at the end of the financial year is a responsibility that companies accept for the environment around them. It is a good working practice for companies to engage in their local communities and understand that brand names depend not only on quality, price, and uniqueness but on how they interact with companies’ workforce, community, and environment.” There is more on the role of government in the literature review.

Methodology

A normative literature review is an approach used in this paper. A study done by Sindakis et al. (2022) used a systematic literature review to analyze the theoretical concepts of the resource-based view and resource-based theory by using relevant keywords and academic databases. However, the researcher used a normative literature review in this paper. According to Routio (2005), the normative method parallels system analysis and design, addresses a problem area for vulnerability, and explores the transition probability. Normative literature reviews aim at summarizing or synthesizing what has been written on a particular topic, in the case of this study CSR and the role played by the government to promote CSR but do not seek generalization or cumulative knowledge from what is reviewed. In this study, the researcher selected studies that support the view concerning the topic of study, and content analysis is also used when needed. Normative literature texts that contain knowledge are labeled positively as a possibility of action. Carroll (1979a, b) provides a very practical viewpoint in which normative CSR can be interpreted as the social responsibility of the business that encompasses the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary expectations that society has of organizations at a given point in time. Haase (2015) argues that normative concern is an idea “good for society” in terms of the diverse entities for which the results in facilitation. The Haase (2015) study concluded that normative aspects of CSR ethics inform about related values, norms, and principles. The review of literature as a method helped synthesize the available knowledge of CSR, which enables us to know the fact and evidence about CSR and be able to draw data sources to solve the problem of the research. The literature reviews in this paper seek to summarize existing research by identifying patterns, themes, and issues as well as helping to identify the conceptual content of the field and furthering theory development (Seuring & Müller, 2008). Levy and Ellis (2006) similarly define a literature review as a sequence of steps for collecting, comprehending, analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating published research to provide a firm foundation for a topic. The literature review in this paper brings credibility to writing about CSR. This literature review sheds light on CSR practice and the role of government in promoting CSR, in general, irrespective of a country in both developed and developing countries.

Theoretical Framework of CSR and Literature Review

There are many theoretical frameworks for CSR. In other words, CSR’s theoretical framework will be analyzed and reviewed through the lens of some of its theories. This paper examined the artificial entity, the aggregate, collaborative, stakeholder, political, social contract, legitimate, corporate sustainability, and corporate accountability theory. These theoretical frameworks shed light on CSR, hence informed practice. The artificial entity theory’s basic assumption is that all of the economic activity conducted by a business is separate from that of its owners. The main idea here is that all corporation activities are a limited liability or separation of ownership from control. Under this theory, the owners of the corporations are not personally responsible for the company loan, and liabilities creditors cannot go after the owner’s assets. According to Chaffee, the artificial entity implies that a company is nothing more than the legal structures to which the state gives life and that the company owes its existence to the government. Palmiter (2009) notes that a company is a structure within which modern business relationships with individuals. Therefore, the government or the state is at the core of this corporate principle. Without the consent of a government granting the right and privilege of life, companies do not exist.

TAs argued by Freeman (1984), the stakeholder approach assumes that the management of the diverse interest within a company can be improved and enhanced by maintaining a balance between shareholders’ internal and external needs. Freedman further states that company stakeholders are those “groups without whose sponsorship the business will cease to exist.” Such groups include staff, clients, political action organizations, vendors, local governments, financial institutions, media, environmental groups, policy organizations, and financial institutions. The core principle of this philosophy is that business should be motivated not only by profit but also by interest, intention, and ethics. This theory also emphasizes addressing the need of all stakeholders, particularly the quiet local communities and the environment. Thus, the organizational responsibilities go beyond profit maximization. Dellaportas et al. (2005) attest that if there is no balance between human rights and the company’s duty in that field, the company becomes a winner when society becomes a loser. A win–win partnership should be adopted by companies and societies. The review of the literature of this paper focuses on the most relevant academic publication, books, and other sources relevant to CSR, whether historical or modern means synthesis of the available knowledge of a specific area and literature refers to the knowledge and information about the concepts, definition, and theories used in the concerned field of investigation. The review of literature helps a researcher to know the facts and evidence available to solve the research problem.

Friedman (1970) argues that a company’s primary social duty is to use its capital for profit. In an article in New York Times, Freedman wrote that there is only one social responsibility of business which is to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits as long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to engage in open and free competition without deception or fraud. Furthermore, Chafee (2017) suggests that it may be reasonable to assume that corporations should be interested in socially responsible actions, but because of the nature of the organization and the theoretical nature of corporations, it is far from being understood. Chafee (2017) concluded that the present theories for firms, the concern theory, real entity theory, and engagement theory partly describe how corporate firms exist. But, it fails to explain why the company exists. Chaffee argues that while each of these corporate theories has some relevance, none of them provides a full description of what a company is. He attests to the fact that although some of these theories may seem contradictory, they have some foundation in reality. He suggested merging these three theories to form collaboration theory which explains why corporation exists. Corporations exist to make money, but they also have a social responsibility to the communities they operate in, either financially or in any other form.

Today, we cannot deny that business has created an impact on a different area of society, either on employees, society, or the environment. Many corporations all over the globe have mobilized resources to help their communities in great numbers. Some companies have made financial donations toward health facilities in their local communities or to their various governments to help fight the COVID-19 pandemic. A study conducted by Cheema-Fox et al. (2020) on corporate resilience and response during COVID-19 concluded that companies with more positive sentiment exhibit higher institutional investor money flows and less negative returns than their competitors. This is especially true for companies with more salient responses. A study also done by Mahmud et al. (2021) concluded that CSR leaders in the USA adopted various mechanisms for protecting their employees, continuing customer services, and caring communities through diversified CSR – the COVID-19 initiatives. They contested that it was the best time to become together (maintaining social distance practices and health professionals’ guidelines) to save the people and make the earth more beautiful than ever it was. At this time, firms should look not only for financial performance but also for society’s benefit and the welfare of their stakeholders, such as partners, families, employees, customers, and communities. At this moment of crisis, the corporation did not think only about its profits but the various communities and societies they operate.

It is evident from Mahmud et al.’s (2021) finding that the COVID-19 pandemic has people living in a go-ahead and penetrating time, although it adversely affects the earth and causes shocks for governments, businesses, communities, families, and individuals worldwide. Businesses are ongoing to help all of their stakeholders circumnavigate difficulties as businesses always do. As communities also respond to the global public health crisis caused by COVID-19, most companies’ focus also remains on supporting their employees’ health and income while caring for their customers and communities. In this regard, Owens Corning’s representative remarked is very important when he said that “These are extraordinary times that remind us of the power of the human spirit and how much we can overcome when we come together. And together, we will get through this.” This is remarkable. The same sentiment as made by Owens Corning was also echoed by Kingo (2020), the CEO and Executive Director of United Nations Global Compact; she argued that the COVID-19 pandemic had taught us an important lesson about ourselves as a human community: We are interconnected with and interdependent in ways we did not fully understand before. My health and well-being are dependent on my health and well-being, and the same principle applies beyond borders and regions. Indeed, our collective health defines the health of businesses and economies within and across nations. This new awareness has born a sense of solidarity and interdependency that I have found heartwarming. We care about each other. She argues that when the pandemic hit, the global compact was among the first initiatives to issue a call to action to all businesses. We said that it would have huge economic and social impacts and that they needed to double down on their responsibilities regarding our 10 business principles – based around human rights, labor, anti-corruption, and the environment – and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the UN’s blueprint for change …furthermore, that the UN Global Compact left companies in no doubt that the way forward is not to just zoom in on their financial bottom line, but to become even more responsible, and anchor the Principles and the Sustainability Goals in their business. Thus, the human spirit is such that when faced with a challenge such as this COVID-19 pandemic, try to work together. Many companies have remained resilient in supporting their partners, employees, customers, and communities where they do business. Although the pandemic is very tough, many companies have adopted different approaches, such as working from home, social distancing, and travel restrictions, as well as offering other incentives such as paid leave and sick pay to remain afloat. All these approaches were geared toward a common good between the companies and their customers. Some corporations have purchased products and machinery equipment to fight this pandemic. For example, in the USA, Blue Cross Blue Shield Minnesota funded 100 kits with surgical drape material that were prepared by partner Knit & Bolt for community volunteers to make 2500 N95 mask covers for North Memorial Health in mid-April according to corporate citizenship response to Covid-19 (2020). Some companies converted their production line or chain to produce useful tools to use by doctors and nurses in hospitals, such as masks, gowns, hand sanitizers, and respirators. Some companies have even allowed their employees to work from home and given some financial support to their communities. Thus, CSR activities that are beneficial to customers, employees, and the general public would create an everlasting impact.

For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many corporations provided help in their time of need to their communities, while some companies tried to take advantage of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis by raising the prices of their products and behaving unethically. However, many corporations or companies acted ethically and provided financial support and donations to their various communities or various governments. The likes of Ferrari Company used its production chain for car manufacturers to produce valves for respirators to be used in hospitals by doctors and nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Armani decided to use its production chain to make personal protective equipment (PPE) for hospitals. Some corporations in the United Kingdom converted their production chains to produce personal protective equipment (PPE), ventilators, and sanitizers, while others donated their product or money to hospitals to help fight the pandemic. Meanwhile, some supermarkets allocated some time for the elderly and NHS workers.

In Cameroon, some corporations like SCR MAYA, UBA group, and businessman Baba Dan Pullo and others donated money to President Paul Biya’s created Solidarity Fund to fight against coronavirus. Corporations in Cameroon should embrace the CSR agenda and activities as that cooperation’s helped societies in need, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, firms or cooperation with authentic CSR activities will always build a strong relationship with their customers and the general public whenever they operate. Hence, there is strong evidence to show that citizens and businesses, during this crisis, donated money and equipment to help those in need. The help from the citizens and from the corporation will always have a significant and eternal impact on their clients, communities, and the countries in which these operate, whether during a crisis or in normal periods or circumstances.

Several business leaders have been very generous to some governments around the world during this pandemic. Jack Ma, for example, the co-founder of Alibaba in China, helped many developing countries in Africa with PPE equipment to protect frontline nurses, doctors, and people to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. Others are the USA base Bill Gates and Melinda Gates, Twitter USA’s Jack Dorsey, and several other company industrialists. These are the realities of CSR activities or agendas in action, a concept that originated from the conviction that businesses have an obligation toward society and humanity at large.

The earlier literature on CSR, according to Rahman, was more oriented toward the organization’s economic philosophy, which seeks to maximize income without disadvantages. For Carroll (1999), CSR literature dates back to Adam Smith’s work.

The literature on CSR and the role of government in promoting the CSR agenda is in the advanced stage in developed countries, such as the UK, Denmark, Austria, and the European Commission (2006). Hence, Dahlsrud (2008) acknowledged that CSR refers to specific firm activities that align their economic, environmental, and social objectives within their strategies and operational decisions. On the other hand, Gavin (2019) attested to the fact that CSR is a business model in which for-profit companies seek ways to create social and environmental benefits while pursuing organizational goals, such as revenue growth and maximizing shareholder value. McLennan and Banks (2019) also acknowledge that CSR growth as an emerging research field and more attention to the 21st-century business stem realized that business and society are interconnected in ways that exceed critical relationships between companies’ employees, customers, suppliers, and community. Subsequently, Mugova et al. (2017) also argue that corporate generosity is to not only create favorable stakeholder attitudes and better supportive behaviors (e.g., employment, purchasing, investment opportunities) but also, over the long run, strengthen stakeholders–company identifications, uphold a corporate image, and shape stakeholders’ socially responsible and advocacy behaviors. Many see CSR as an approach to bring together many aspects of an organization’s strategy that can guide a greater society. According to Batty et al. (2016), CSR is a voluntary commitment more than modest compliance with government rules and regulations. A study requested by the JURI Committee European Parliament went further to emphasize that CSR has grown to become more central to business operations, with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles assuming a pivotal role in the context of the purpose of the corporation and as such CSR roles is committed to ensuring organizations track and achieve their goals. They concluded that the promotion of CSR and RBC, on the other hand, upholding business and human rights, as well as fostering sustainability and the implementation of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable development, had made progress in the following area: (1) encouraging companies to carry out appropriate due diligence along the supply chain; (2) including human rights protection; (3) increasing transparency and promoting sustainable finance; (4) encouraging socially and environmentally friendly business practices, including through public procurement; (5) promoting the implementation of CSR and RBC, including outside the EU, through EU trade instruments and EU’s participation in multilateral fora; (6) developing dedicated approaches for certain specific sectors or companies; and (7) pursuing horizontal approaches, including working with EU’s Member States on National Action Plans.

Research conducted by Moon (2004) on the role of government in promoting CSR found that governments were interested in CSR production in Denmark and the Netherlands. Moon (2004) argues that while the United Kingdom and Denmark promoted CSR in the case of Denmark, they give parallel examples, unemployment and social exclusion were high in the 1990s, and Karen Jesperson, Denmark’s then Minister for Social Affairs, was inspired by the Grundfos Company’s CSR. She saw the way business contributed to solving social problems.

) suggested five core themes to be followed by the government in developing countries to promote CSR as follows: (1) building awareness of the CSR agenda and its implications, (2) building capacity to shape the CSR agenda, (3) engaging a stable and transparent environment for pro-CSR investment, (4) engaging the private sector in the public policy process, and (5) frameworks for assessing priorities and developing strategy.

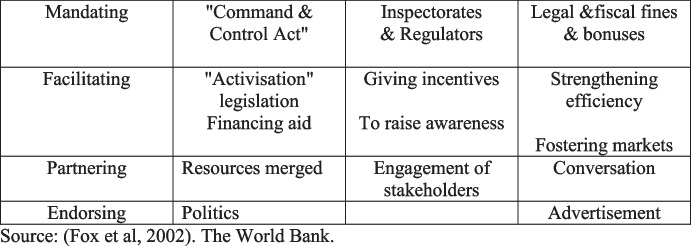

He argues that the relevance of a specific initiative by country may vary, and it is clear from the above discussion that mandating, facilitating, partnering, and endorsing are the vital roles of the government in promoting CSR. Figure 1 below provides a bird-eye view of the key roles of the government across specific themes in promoting CSR.

Fig. 1.

Four core roles of CSR development

There is also a comprehensive analysis by ) on the government’s position in promoting CSR based on four critical roles as seen in Table 1, namely, (1) mandating – defining, under the law of the nation, the minimum requirement for business performance; (2) facilitating and promoting the CSR agenda and delivering social and environmental matters; (3) partnering – enabling public, private, and civil society players; and (4) recognizing or rewarding best practices for companies that manufacture a green product, for example, creating a green product that protects the environment. ) acknowledge that each government has a diverse approach to CSR. For example, western or European countries may differ from developing countries in Africa. To this effect, Gond et al. (2011) argue that the European government often uses public policy means to guide companies to fulfill their CSR, considering that government policies for global economic growth would benefit them. The critical forces for CSR are also government policies and legislation. They gave examples of countries in East Asia, such as Japan, Korea, and China, whose governments are becoming less internationalist and more empowered by civil society. Therefore, their approaches to the CSR agenda are different due to various government and governance structures and policies.

Table 1.

Instrument that the government can use in advancing the CSR agenda

| Type | Instrument |

|---|---|

| Awareness raising | Award systems, information portal, campaigns, training and capacity building initiatives, public agency transparency of payments, identifying bad results, marking tool kits |

| Partnering | Multi-stakeholder participation, public–private collaboration, attempts at collective action, round tables |

| Soft law | Corporate Governance Code, Code of Ethics, Enforcement of International Standards, CR Reporting Laws, Tax Exceptions for Philanthropic Activities, Connection of CR Aspects to Public Procurement Policies, and Credit Boards for Export |

| Mandating | Corporation rules, mutual plan regulations, CR reporting rules on stock market legislation, fines for failure to comply |

UN Global Compact and Bertelsmann Stiftung (2010); The World Bank

The UN Global Compact and Bertelsmann Stiftung (2010) also strengthened the framework governments can use to help CSR: raising awareness, cooperation, soft legislation, and compulsory resources to facilitate and encourage voluntary actions, mandating measures to track and implement corporate responsibility. An instrument that governments can use in advancing the CSR agenda is in Table 1 below. In promoting CSR, these tools are vital for government support.

Studies conducted by Zadek (2001) indicate that the government should be interested in changing the link between companies and society. To him, voluntary corporate citizenship programs by corporations are inadequate to address deep-rooted social and environmental problems or challenges. He calls for governmental, corporate, and civil society partnerships. Another study conducted by Reich (2008) rejects that companies determine their CSR and that the political process should be the way to form the private sector’s social responsibility. In other words, collaboration is good for the government, private, and civil society in shaping the CSR agenda. The government to develop alliances with others to promote the CSR agenda that follows their activity in their region. The above studies and reviews of many writers of CSR note that government can play a vital part in the CSR agenda by ensuring business-to-society ties are transparent. The government should not let corporate self-regulate but have a say on how corporations can behave for the benefit of the countries or societies where they operate due to the belief that corporations have a responsibility toward society socially, economically, and environmentally. A study done by Chapagain in Nepal shows that the role of the government in promoting CSR is still inadequate due to the big gap, particularly in endorsing the role of the government, followed by collaborative, regulating, and assisting roles.

Subsequently, a study conducted by Chapple and Moon (2005) on seven countries on CSR in Asia concluded that CSR is different among these seven countries and was not explained by growth but by factors in the business systems of these countries. They testify that CSR, although pursuing the countries of service, was embraced by multinational corporations.

Fukukawa and Moon (2004) conducted a study on a Japanese model of CSR. They concluded that Japan’s business model is comparatively “society-friendly” due to features of its corporate governance, strong alignment with government economic policy, and lifelong work. Another study by Albareda et al. (2009) concluded that the government has been putting policy initiatives to promote CSR. Furthermore, an article written by Kinnear (2020) shows that CSR started as a voluntary formula of private rule, and now, the government is increasingly involved. Many governments and private industries collaborate to promote social agendas, especially during higher unemployment and social discontent in many countries. Therefore, the collaboration between the government and the private corporation is critical to solving some of society’s problems. A study conducted by Aberada et al. on the changing role of government in CSR concluded that governments have common ground on CSR when associating with private and social sectors. Another study conducted by Bhave (2009) concluded that by ensuring that companies perform according to the rules and norms of the society in which they work and that companies profit from CSR activities, the government has a role to play. The government should legislate, collaborate, promote business, and support best practices to boost CSR growth. He concluded that the Government of Gujarat in India is promoting CSR programs to encourage social development.

A study by Tamvada (2020) argues that accountability is partly the regulation of CSR moral responsibility associated with the role of business and the future impacts on society. A vital moral obligation for an organization is the growth of CSR. A study conducted by Sighal in India concluded that the government has a role in ensuring that corporations comply with society’s rules and standards. He suggests that the government can legislate, foster, partner with businesses, and recommend best practices to facilitate CSR expansion. A study conducted by Idemudia (2010) in the state of Nigeria in the Niger Delta concluded that government support for CSR in Nigeria is still restricted and fragmented, so there is no enabling environment in the Niger Delta that stimulates CSR growth. The reasons for the non-existence are the Nigerian state’s systemic and systematic insufficiencies, which reflect a relationship between the state and society. Due to the nature of the Nigerian state, where the politics of anxiety set in and the government cannot properly enforce a coherent CSR policy structure that supports CSR growth in the Niger Delta, the restriction in implementing CSR again is due to practices in Nigeria. The other drawback is that the government restricts CSR practices that contribute to community growth. The study of Idemudia highlights the constraint between the style of the government and its economic system to implement CSR as an enabling vehicle for community development Niger Delta. Government instrument matters concerning CSR agenda and confusion about who does what at a governmental level can create problems, allocating funds from corporations to society, especially in developing countries. There is a need for great alignment and transparency within a government to ensure that the appropriate people within the communities benefit from the corporation’s CSR agenda.

In Cameroon, there has been a case where local administrative officials and traditional rulers (Chief/Fon) were squabbling in public regarding corporation funds not benefiting their local community, especially forestry products, and mining of the quarries, especially locations near big towns in Cameroon. Local chiefs are not happy that the big companies logging wood products in their area are not developing their communities. There are many cases whereby local authorities and the tribal local rulers disagree in public on who should control funding from corporations exploring their local land. Good governance and transparency within the government at all levels of authority are vital so that boundaries are known to avoid clashes of interest by administrators and auxiliary Chiefs/Fons. Disagreement between the local chief and the administrative authorities can lead to conflict. A previous case involving the late mayor of Njombe Penja, Moungou Division, Littoral Province of Cameroon, when he tried to suspend the mining of the quarry operations of his local municipality of Njombe Penja, created a crisis.

The mayor requested that companies exploiting quarries in his municipality should pay CFA 3 to 5 million monthly for the development of his local community runs into problems due to the over-centralization of power in Cameroon by those in government in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Decentralization of authorities or federation would solve some of these problems in Cameroon.

The present system of government in Cameroon of centralization has led to civil war in the two Anglophone provinces, NOSO (Southern Cameroon). There is a need for proper decentralization, federations, or federalism in Cameroon to foster development and growth.

The government in Cameroon needs to collaborate with businesses to implement CSR agenda so that the local mayors and their localities benefit from the natural resource in their locality or municipality. The political elite seems to be the one benefiting more from corporate activities, especially those relating to forestry, aquarist, and mines, to the detriment of the local poor.

Ngaundje and Kwei’s study (2021) reflects the reality on the ground in Cameroon, in which there is a disconnect between the practice and implementation of CSR components. As they argue that businesses have abdicated their responsibilities, but governments have also failed to provide a legal framework within which corporations can effectively comply with their obligations. Since the inception of CSR in Cameroon, the Cameroonian government has remained silent on the subject. Companies in the country retain the option of engaging in CSR or not. Corporations cannot be held solely accountable for a country’s social obligations to its citizens. The government should be involved and draft some soft laws for the corporation and the maintenance of law and order, the provision of security, and the provision of public infrastructure and other critical services. They argue that while mobile telecommunication companies (MTN) and other businesses have a social responsibility to the communities in which they operate, the government must provide the framework necessary to ensure they comply with their responsibilities. It is the government’s responsibility to ensure that an adequate regulatory and enforcement framework exists, ensuring businesses operate sustainably. The government in Yaoundé should therefore provide a legal framework within which cooperation engages in CSR agenda or have effective decentralization or federalism so that some of these issues of CSR are resolved at the local level to meet the needs of the people, not the few elites.

Annex conducted a literature review on CSR and Sustainable Development Goals in sub-Saharan Africa, in particular, CSR activities by businesses and organizations in French-speaking sub-Saharan African countries, and concluded that while CSR core values are about business companies’ contribution to society, it is possible to incorporate economic and environmental activities into their agenda. Hence, there is little evidence of policy reforms reflecting CSR activities among businesses representing the sustainable development agenda in sub-Saharan countries. Therefore, there is a need to access CSR practices among corporations regarding healthy and inclusive growth and sustainable development, and this requires government collaboration either at the local or national level. According to a study conducted by Capaldi (2016), some CSR literature fails to address the economic question of how we value CSR about the loss of resources that could have been used for other purposes, such as shareholder charitable contributions. He asserts that the critical question in CSR scholarship is whether it is descriptive, normative, or something else. According to him, the current normative literature is insufficiently descriptive and philosophically deficient. He proposed several additional CSR research activities (for example, consumer responsibility) that are compatible with a morally pluralistic world conducive to market economies. On the other hand, Walker and Chen (2019) argue that social innovation is frequently conflated with corporate social responsibility in public discourse.

Anep cited GIZ in a survey showing that the CSR barriers in businesses are in several components, such as policy structure, monitoring, reporting, staff involvement, finance, government, assessment, project management, leadership and governance, and benefits, especially in businesses or businesses in Namibia, South Africa, Kenya, Ghana, Mozambique, and Malawi. He cited the survey GIZ, which concluded that in French-speaking Sub-Saharan African countries such as Cameroon. In a study done by Giron et al. (2021) on sustainability reporting and firms’ economic performance, evidence from Asia and Africa, cited by Reverte (2009), argue that media exposure is the most influential variable for explaining CSR disclosure practices of Spanish-listed firms. On the other hand, a study conducted by Heikka and Karayiannis (2019) explains how corporate social responsibility efforts on the community level by using dialogic methods to learn the needs of the communities. Communities should be the greatest beneficiaries of the CSR agenda and not the elites of those communities, as in many developing countries. The government should take a leading role in implementing various CSR agendas in their various nations.

Oginni and Omojowo (2016) conducted a study on sustainable development and CSR in sub-Saharan Africa and concluded that industries in Cameroon are above the economic dimension in the order of priority environmental and social magnitudes. Hence, few enterprises implement broad-based CSR to encourage sustainable business practices.

Khan et al. (2013) conducted an explorative study of CSR in Saudi Arabia and concluded that the government of Saudi Arabia encourages businesses to embrace CSR activities in serving society as a whole. They concluded that, because of the socio-cultural background and Islamic values, Saudi Arabia as a kingdom was historically socially responsible. They argue that CSR activities are more philanthropic than linked to a strategic approach in some Middle East and GCC states. They argue that these companies are very serious about their CSR activity, and so they create separate departments to deal with CSR supported by the top management of these companies. However, they caution that most companies in the Kingdom lack the atmosphere created by Aramco and other enterprises. Saudi Arabia companies need a multi-pronged approach to addressing economic, legal, social, and environmental goals.

Khan et al. (2013) argue that Islamic ideas are deeply ingrained in Saudi business culture and business conduct of social responsibility because of the Zakat (compulsory charity) principle that is a must for all Muslims. Islam, especially in Middle Eastern countries, has influenced CSR. See the definition of Zakat (compulsory charity) (Quran 51:19) and also the Prophet Muhammad’s words (PBUH). Concerning their societies and society at large, Saudi companies should support CSR initiatives. The policies and practices of the CSR initiative that contribute to the enhancement of community growth and solve problems with employability at the community level and society as a whole are good. Khan et al. (2013) also stressed the role of educational institutions, business schools, and universities in ensuring that CSR teaching and training were included in the curriculum to benefit businesses and communities as a whole, helping the Kingdom’s development.

Alharthey (2016) in Saudi Arabia regarding CSR argues that Saudi Arabia’s CSR work is philanthropy influenced by Saudi Arabia’s socio-economic, religious, and cultural perspectives. The government has not pressured or compelled companies to implement socially beneficial policies’ CSR programs. Examining the role of CSR activities in universities, Alharthey concluded that universities are more philanthropic than CSR strategy. Gravem (2010) did a study in Saudi Arabia on CSR and concluded that CSR in the Kingdom is considered an essential instrument for the private sector to contribute to the growth of Saudi society through the Saudification of the labor force and the diversification of the Kingdom’s economy. The main difference between CSR and Saudi’s international concept is that CSR focuses globally on human rights, labor rights, the climate, and anti-corruption, while CSR focuses globally on human rights, labor rights, and anti-corruption. Research by Ward et al. (2020) on CSR and developing countries concluded that CSR provides middle- and low-income governments with empirical incentives to enhance business cooperation conditions.

Ngaundje and Kwei (2021) conducted a study on Cameroon’s mobile phone network corporate social responsibility in Cameroon: the Case of MTN. To help society, they participate in CSR activities such as youth education, volunteer work, and distribution of school supplies and other necessities to those in need. Because of MTN Cameroon’s high-profit margins, they argue little is known about the concept of CSR and how CSR is applied. CSR is still a relatively new concept in Cameroon, which is why big corporations lack CSR policies or a CSR team due to the absence of a comprehensive framework for corporate social responsibility (CSR) policy in the country. CSR is still in its infancy in Cameroon, and the country’s CSR dialog has just begun. A large part of their CSR activities is philanthropy: Companies perform charitable acts.

Ndzi (2016) affirms the argument made by Ngaundje and Kwei (2021). CSR concept is relatively new in Cameroon. Hence, many big companies do not have either a CSR policy in place or a team that deals with CSR issues; few companies are identified in Cameroon as having CSR policies in place. One of these companies is the energy of Cameroon (ENEO) which is the hydro-electrical company in Cameroon where she conducted her study. To her, ENEO is one of the companies in Cameroon that has CSR policies and is involved in activities and projects to help the local communities and the country to alleviate poverty. However, the finding from her study indicates that ENEO CSR practices have not been efficient and very limited in these areas. ENEO could be described as not practicing any CSR activities. However, the none existence of CSR activities in these areas does not affect the profitability of the business because ENEO has a monopoly in the market in Cameroon. That is why cooperation in developing countries can put policies and not follow them like ENEO. There is no law requiring these big corporations to follow concerning CSR. In reviewing the literature on CSR from developed and developing countries, it is evident that the government should directly intervene in CSR activities or agenda by introducing soft laws and policies directly related to CSR instead of leaving it to companies to safely regulate or be it voluntary as the case of today. There is a need for the government not only to promote CSR but also to put soft laws or regulations measures and financial incentives to drive these big corporations to give back to the various communities they operate in terms of tax rebirth.

Discussion

There is a need to understand corporate social responsibilities (CSR) and the role government can play in promoting CSR activities and agenda as practiced in developed western countries and some Asian countries compared to developing countries. Good collaboration between the two in sharing good practices can enhance CSR activities and lead to growth and development instead of seeing CSR as philanthropy in developing countries. Business is not only about making money wherever they operate but also about contributing to the greater good of the society they operate. To this effect, a study done by the JURI Committee European Parliament emphasizes that CSR is central to business operations, with environmental, social, and governance principles assuming a pivotal role in the context of the purpose of the corporation and as such CSR roles is committed to ensuring organizations track and achieve their goals. They concluded that the promotion of CSR should be such that corporations be upholding business and human rights as well as fostering sustainability and the implementation of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable development by doing the following: (1) encouraging companies to carry out appropriate due diligence along the supply chain; (2) including concerning the human rights protection; (3) increasing transparency and promoting sustainable finance; (4) encouraging socially and environmentally friendly business practices, including through public procurement; (5) promoting the implementation of CSR and RBC, including outside the EU, through EU trade instruments and EU’s participation in multilateral fora; (6) developing dedicated approaches for certain specific sectors or companies; and (7) pursuing horizontal approaches, including working with EU’s Member States on National Action Plans.

Research Implication

This study examines CSR and the role of government in promoting CSR. It is evidenced that CSR has multiple meanings with a complex idea and can correlate with several values, for example, environment and the environment or community it operates; it could be considered philanthropic behavior toward society and also can be seen as following policies and activities that are desirable in terms of society’s goals and values. For others, it could be seen as a consideration of problems outside the company’s restricted financial, technological, and legal requirements. But for Carroll, it is an economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary expectation (philanthropic). For Freeman (1984), it is the business’s responsibility to groups and individuals who can both influence and be influenced by business operations. For Hopkins (2003), it is a company’s stakeholder’s moral and responsibility to attain the two-fold goal of maintaining profit and improving the living standard of stakeholders inside and outside the company. For Mohr et al. (2001), it is the commitment made by a company to remove or reduce its adverse impact on society and boost the long-term beneficial influence on society. Scholars who view CSR as a social perspective put social issues at the core of activities, i.e., CSR policies reflect its responsibilities to advance social interests, while the stakeholder’s perspective puts profit at the core of CSR. Whatever the direction of firm CSR activities, developed countries’ governments play a role in promoting CRS based on four critical roles as follows: (1) mandating – defining, under the law of the nation, the minimum requirement for business performance; (2) facilitating and promoting the CSR agenda and delivering social and environmental matters; (3) partnering – enabling public, private, and civil society players; and (4) recognizing or rewarding best practices for companies that manufacture a green product, for example, creating a green product that protects the environment. The government in developed countries also uses some frameworks to help strengthen CSR through awareness raising, cooperation, soft legislation, and compulsory resources to facilitate and encourage voluntary actions, mandating measures to track and implement corporate responsibility. They also create a ministerial department to facilitate the CSR agenda in their countries.

In some developing countries, CSR is inexistence; see a study conducted by Idemudia (2010). For some, CSR is philanthropic and not geared toward economic development and growth. For some countries, CSR is having religious connotations. Developing countries need to learn from some good practices as developed in the west whereby a government takes an active role in promoting CSR and at the same time creating soft laws that the companies can follow rather than letting it be a voluntary practice by companies. In developing countries, due to the absence of soft laws and regulations, the elite are the ones who benefit, not the masses. Therefore, the government needs to play an important role in promoting CSR. This research has extended the literature review on developed and developing countries and the role the government can play in promoting CSR.

Practical Implications

In terms of practical relevance, the government in both developed and developing countries can play an important part in promoting CSR because CSR is still voluntary without strong legislation behind it. The need for collaboration and sharing of good practices is necessary for developed and developing countries because the majority of these big companies operating in developing countries are mostly western companies. This research is useful for companies or big businesses in the west operating their business in developing countries. CSR activities that follow good legal, environmental, social, and developmental issues in giving back to the communities they operate in would always be trusted. Thus, the four core CSR responsibilities of economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic are important, and the government has to be involved because they are the one that gives licenses to these companies to operate. Developed countries have already incorporated all these aspects of CSR, economic, ethical, legal, and philanthropic responsibilities within their corporation. Firm managers need to create value for the community in which they operate by giving back to affect growth and development. Developing countries should therefore adopt best practices. For example, the British government sees CSR as a long-term business strategy for giving back to society. Japan’s business model of CSR is comparatively “society-friendly” due to features such as its corporate governance, strong alignment with government economic policy, and lifelong work.

In some developing countries, CSR is in existence or only in corporations palpitate; see a study by Idemudia (2010) in the state of Nigeria in the Niger Delta which concluded that government support for CSR in Nigeria is still restricted and fragmented, so there is no enabling environment in the Niger Delta that stimulates CSR growth. The reasons for the non-existence are the Nigerian state’s systemic and systematic insufficiencies. Due to the nature of the Nigerian states where the politics of anxiety set in and the government is unable to properly enforce a coherent CSR policy structure that supports CSR growth in the Niger Delta, the restriction in implementing CSR again is due to practices in Nigeria. Also, see a study by Ngaundje and Kwei (2021) with regards to CSR in Cameroon’s mobile phone network MTN which concluded that CSR is still a relatively new concept in Cameroon, which is why the majority of large corporations lack CSR policies or a CSR team. This is due to the absence of a comprehensive framework for corporate social responsibility (CSR) policy in the country at large. CSR is still seen as philanthropy in some developing countries and needs to be part of growth and development in the developed world and in some countries in the Middle East.

Limitations and Future Research

This present research is constrained by certain limitations. The first of which is that the majority of literature for this study is western. Fewer studies on CSR activities and the role of government in promoting CSR are from developing countries; hence, CSR in developing is new or inexistence, and even if it is in the books of the corporation operating in developing countries, only the elites seem to be benefiting from funds which could go a long way for their development and economic growth instead of seeing it mere philanthropy. In future studies, the researcher will try to gather more literature from developing countries’ perspectives on CSR and the government’s play in promoting CSR.

Conclusion

The outcome of this paper demonstrates that governments should play a proactive role in promoting CSR in any given nation or state, as Caroll (1991) argues that CSR is “an economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary expectation (philanthropic).” The same sentiment is expressed by Freeman (1984), who argues that business has responsibilities for groups and individuals who can both influence and be influenced by business operations. Hopkins (2003) also acknowledged that CSR has four core principles or addenda of economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary expectation (philanthropic) that should not be left only to the corporation’s voluntary means but should be safeguarded and managed so that there is a win–win situation between a corporation and the communities or societies they operate. In some developing countries in Africa, CSR activities are inexistence not implemented, or the elites are the ones who benefit from such funds that could help spur development in those countries. CSR’s best practices should be transferred from developed west to developing countries since most of these corporations operating in developing countries are businesses with origins in the western world, for example, firms operating in mining or forestry products or communication.

Collaboration is vital so that CSR core issues are shared. There is a need for a transfer of best practices of CSR. In promoting CSR activities or agendas, each country or government should carefully consider its own social, economic, cultural, political, and growth situations. Hence, good governance is essential for CSR activities, especially in developing countries where centralization leads to inefficiencies and ineffectiveness. There is a need to avoid situations whereby some oil companies and forestry exploration corporations in developing countries in Africa do not directly benefit their local communities.

Most local communities in developing countries feel abandoned by corporations exploring their natural resources. There is a growing sentiment of anti-western domination, notably when some of these western companies are operating in developing countries and are not implementing CSR activities or are benefiting a small elite in developing countries. Good governance and transparency in the management of natural resources in developing countries concerning CSR agenda are welcome, and best practices should be shared and not kept as a policy that is not used or communicated. The need for local chiefs in developing countries and the local authorities to be transparent in managing local land and its natural resources for local development and growth is essential hence the CSR agenda. Thus, the significant contribution of this paper is that governments should play a proactive role in promoting CSR activities that benefit local communities and their societies. Developing countries’ nature government systems need to be transparent and serve the interest of their people. We need to avoid a situation whereby rich oil countries with significant natural resources do not benefit those at the local level but rather tiny elites who have confiscated the country’s natural resources for themselves only and their families. Developing countries’ governments can use varied instruments in promoting CSR by creating awareness, fostering and partnering, mandating, volunteering, or putting soft legislation in place for corporations to further improve CSR activities that benefit communities at large. Soft legislation will enable some of these corporations to comply with their CSR initiatives. For example, tax exemptions for a business that contributes money to educational, environmental, and social issues are vital for developing countries instead of CSR activities as philanthropic only. CSR should not be seen only as a philanthropic agenda but rather should focus on social, economic, environmental, and legal to spur economic growth and development for developing countries, especially in Africa.

The literature shows that many countries in the west and some developing countries profit from CSR activities and, more importantly, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The result also shows that developing countries should not blindly be copying from western countries’ CSR agendas. They should create CSR agendas that reflect their realities. Developing countries in the south should learn from developed countries’ CSR implementation, for example, the United Kingdom, the USA, Sweden, Denmark, South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Saudi Arabia, and India. There should not be a blind adoption of the implementation of the CSR agenda from the north; government and governance must create their own CSR agenda that fit them and their communities’ realities and context. This study contributes to CSR issues in developed countries, including how developing countries can learn from good practices in the developed world to strengthen CSR in developing countries, as well as the role of government in promoting CSR agendas for development and growth rather than seeing CSR as philanthropy. Good collaboration between developed and developing countries in enhancing best practices of CSR is vital because corporations have responsibilities to society that go beyond economic, legal, and moral expectations. Future research is needed to examine CSR agendas in both developed and developing countries and not allow CSR activities to be only a voluntary act by corporations.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Interdisciplinarity and Transdisciplinarity in Higher Education, Democracy and Economy

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Albareda L, Lozano JM, Ysa T. Public policies on corporate social responsibility: The role of governments in Europe. Journal of Business Ethics. 2007;74:391–407. doi: 10.1007/s10551-007-9514-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albareda, L., Lozano, J. M., Tencati, A., Midttun, A., & Perrini, F. (2008). The changing role of governments in corporate social responsibility: drivers and responses. Business ethics: A European review, 17(4), 347–363. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1259960 or 10.1111/j.1467-8608.2008.00539.x

- Albareda L., Lozano J.M., Tencati A., Perrini F., & Midttun A. (2009). The role of government in corporate social responsibility. In: Zsolnai L, Boda Z, Fekete L (eds) Ethical Prospects. Springer, Dordrecht

- Alharthey BK. Role of corporate social responsibility practices in Saudi universities. International Journal of Business and Social Research. 2016;06(01):2016. doi: 10.18533/ijbsr.v6i1.902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bapuji H, Patel C, Ertug G, Allen D. Corona crisis and inequality: Why management research needs a societal turn. Journal of Management. 2020;46(7):1205–1222. doi: 10.1177/0149206320925881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batty RJ, Cuskelly G, Toohey K. Community sport events and CSR sponsorship: Examining the impacts of a public health agenda. Journal of Sport and Social Issues. 2016;40(6):1–20. doi: 10.1177/0193723516673189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhave, A. G. (2009). Experiences of the role of government in promoting corporate social responsibility initiatives in the private sector recommendations to the Indian state of Gujarat. A master thesis submitted to the University of Lund, Sweden. https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?fileOId=1511079&func=downloadFile&recordOId=1 511060

- Boadi EA, He Z, Bosompem J, Say J, Boadi EK. Let the talk count: Attributes of stakeholder engagement, trust, perceive environmental protection and CSR. SAGE Open. 2019;9(1):1–15. doi: 10.1177/2158244019825920. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi, N. (2016) Directions in corporate social responsibility. Int J Corporate Social Responsibility, 1(4) . 10.1186/s40991-016-0005-5#citeas [DOI]

- Caroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons.

- Caroll AB. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business and Society. 1999;38:268–295. doi: 10.1177/000765039903800303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll A. A three dimensional model of corporate performance. Academy of Management Review. 1979;4(4):497–505. doi: 10.2307/257850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll AB. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate governance. Academy of Management Review. 1979;4(4):497–505. doi: 10.5465/AMR.1979.449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]