Abstract

Purpose

Current practice in organ donation after death determination by circulatory criteria (DCD) advises a five-minute observation period following circulatory arrest, monitoring for unassisted resumption of spontaneous circulation (i.e., autoresuscitation). In light of newer data, the objective of this updated systematic review was to determine whether a five-minute observation time was still adequate for death determination by circulatory criteria.

Source

We searched four electronic databases from inception to 28 August 2021, for studies evaluating or describing autoresuscitation events after circulatory arrest. Citation screening and data abstraction were conducted independently and in duplicate. We assessed certainty in evidence using the GRADE framework.

Principal findings

Eighteen new studies on autoresuscitation were identified, consisting of 14 case reports and four observational studies. Most studies evaluated adults (n = 15, 83%) and patients with unsuccessful resuscitation following cardiac arrest (n = 11, 61%). Overall, autoresuscitation was reported to occur between one and 20 min after circulatory arrest. Among all eligible studies identified by our reviews (n = 73), seven observational studies were identified. In observational studies of controlled withdrawal of life-sustaining measures with or without DCD (n = 6), 19 autoresuscitation events were reported in 1,049 patients (incidence 1.8%; 95% confidence interval, 1.1 to 2.8). All resumptions occurred within five minutes of circulatory arrest and all patients with autoresuscitation died.

Conclusion

A five-minute observation time is sufficient for controlled DCD (moderate certainty). An observation time greater than five minutes may be needed for uncontrolled DCD (low certainty). The findings of this systematic review will be incorporated into a Canadian guideline on death determination.

Study registration

PROSPERO (CRD42021257827); registered 9 July 2021.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12630-023-02411-8.

Keywords: critical care, death, heart arrest, life support care, systematic review, tissue and organ procurement

Résumé

Objectif

La pratique actuelle en matière de don d’organes après une détermination du décès par critères circulatoires (DCC) préconise une période d’observation de cinq minutes après l’arrêt circulatoire et le monitorage de la reprise non assistée de la circulation spontanée (c.-à-d. l’auto-réanimation). À la lumière de données plus récentes, l’objectif de cette revue systématique mise à jour était de déterminer si un temps d’observation de cinq minutes était toujours suffisant pour une détermination de décès selon des critères circulatoires (DCC).

Sources

Nous avons effectué des recherches dans quatre bases de données électroniques depuis leur création jusqu’au 28 août 2021 pour en tirer les études évaluant ou décrivant des événements d’autoréanimation après un arrêt circulatoire. L’examen des citations et l’extraction des données ont été réalisés de manière indépendante et en double. Nous avons évalué la certitude des données probantes à l’aide de la méthodologie GRADE.

Constatations principales

Dix-huit nouvelles études sur l’autoréanimation ont été identifiées, comprenant 14 présentations de cas et quatre études observationnelles. La plupart des études ont évalué des adultes (n = 15, 83 %) et les patients dont la réanimation avait échoué à la suite d’un arrêt cardiaque (n = 11, 61 %). Dans l’ensemble, l’autoréanimation a été signalée entre une et 20 minutes après l’arrêt circulatoire. Parmi toutes les études admissibles identifiées par nos comptes rendus (n = 73), sept études observationnelles ont été identifiées. Dans les études observationnelles sur l’interruption contrôlée des thérapies de maintien des fonctions vitales avec ou sans DCC (n = 6), 19 événements d’autoréanimation ont été rapportés chez 1049 patients (incidence 1,8 % ; intervalle de confiance à 95 %, 1,1 à 2,8). Toutes les reprises ont eu lieu dans les cinq minutes suivant l’arrêt circulatoire et tous les patients en autoréanimation sont décédés.

Conclusion

Un temps d’observation de cinq minutes est suffisant pour un DCC contrôlé (certitude modérée). Un temps d’observation supérieur à cinq minutes peut être nécessaire en cas de DDC non contrôlé (faible certitude). Les résultats de cette revue systématique seront intégrés à des lignes directrices canadienne de pratique clinique sur la détermination du décès.

Enregistrement de l’étude

PROSPERO (CRD42021257827); enregistrée le 9 juillet 2021.

Death determination demands well-defined, evidence-based criteria for clinical practice. While this is relevant for all instances of death, it is particularly germane in the context of deceased organ donation. Deceased donation practice must adhere to the dead donor rule, which states that “vital organs should only be taken from dead patients and, correlatively, living patients must not be killed by organ retrieval.”1 Therefore, in cases of organ donation after death determination by circulatory criteria (DCD), the permanent cessation of circulation must be decisively established to ensure that a patient is correctly determined to be dead. The ethical and legal implications of death determination also mandate that criteria for its determination be supported by the best contemporary evidence, so as to also ensure clinicians’ certainty and trust in the process of death determination.

The term autoresuscitation describes the unassisted return of spontaneous circulation, which may occur within variable periods of time following circulatory arrest.2,3 Autoresuscitation has been shown to occur most frequently following termination of unsuccessful cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR),4 but may also occur in the context of controlled withdrawal of life-sustaining measures (WLSM).2,3 Therefore, Canadian recommendations for DCD practice to date have advised an observation period of five minutes after cessation of circulation to ensure its permanence, as autoresuscitation has not been shown to occur after this time.5,6

Our group has previously published two systematic reviews summarizing the evidence on the occurrence and timing of autoresuscitation.2,3 These systematic reviews showed that evidence on autoresuscitation was low in quality and largely consisting of case reports. An updated systematic review is now needed to evaluate emerging evidence on this phenomenon, including the publication of two large observational studies since our last systematic review.7,8 Therefore, the objective of this systematic review was to summarize the information from studies published since the last review, assess the quality of the body of evidence to date, and evaluate whether a five-minute observation period is still sufficient in the context of DCD.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted as part of a larger project in collaboration with the Canadian Critical Care Society, Canadian Medical Association, and Canadian Blood Services to develop a clinical practice guideline for death determination after arrest of circulatory or neurologic function, as well as a medical, brain-based definition of death.9 The review protocol was designed a priori and registered on PROSPERO (9 July 2021; CRD42021257827). The reporting of this systematic review is in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] eAppendix 1).10

Eligibility criteria

We included all studies with patients monitored after arrest of circulation, or that described an autoresuscitation event that was witnessed or captured with continuous monitoring. For this review, an autoresuscitation event was defined as the unassisted return of spontaneous cardiac activity, arterial blood pressure, electrocardiogram, breathing, or other (i.e., as defined by investigators) that was identified by the bedside clinician. There were no restrictions with respect to participant age, clinical context (i.e., controlled or uncontrolled DCD or otherwise), or outcomes evaluated. For this review, controlled DCD refers to DCD that follows controlled WLSM (Maastricht category III) or Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD; Maastricht category V), and uncontrolled DCD refers to DCD that follows unsuccessful CPR (Maastricht category II).11 Case reports and abstracts/conference proceedings were included. Surveys, literature reviews, commentaries/editorials, and animal and ethical analysis studies were excluded. Studies published in languages other than English or French were excluded for feasibility.

Database search and study selection

As we planned to use the results of this updated systematic review to inform a clinical practice guideline, the search strategy from our previous systematic reviews on autoresuscitation was reviewed and updated to reflect changes identified in the literature, terminology, and indexing and translated to a broader selection of databases. Our updated search strategy was designed by an information specialist (R. F.) in collaboration with content experts, and then peer-reviewed by a second information specialist (D. C.) not involved in the study. The final search strategy was developed in Medline and then translated into the other databases, as appropriate (ESM eAppendix 2). We initially searched the following electronic databases from their dates of inception to May 27, 2021: Medline (1946 to 27 May 2021), Embase (1947 to 27 May 2021), Cochrane CENTRAL (2021, Issue 4), and Web of Science (1900 to 27 May 2021). The search was subsequently updated on 28 August 2021. We restricted the search to exclude animal studies and languages other than French or English. Citations were imported into EndNote and duplicates were removed.

Citation screening and data extraction

Citations were uploaded for screening to insightScope,1 a platform for executing large reviews through crowdsourcing.12–15 Citation screening was conducted independently and in duplicate by a team of 11 reviewers recruited from Canadian Blood Services, The University of British Columbia, University of Calgary, Chulalongkorn University, University of Alberta, University of Toronto, and Nova Scotia Health Services. Prior to gaining access to the full set of citations, each potential reviewer read the systematic review protocol and was required to achieve a sensitivity of at least 0.80 when screening a test set of 100 citations (containing ten true positives). This approach is consistent with other systematic reviews conducted using large teams (crowdsourcing),14,16,17 including those published by members of our investigative team.15,18 Screening was performed in two steps (title and abstract, then full text) against the inclusion criteria by two independent reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by the study lead (J. S.) where necessary. Upon completion of full-text review, two investigators (J. S., L. H.) reviewed all retained citations to identify potential duplicates and confirm eligibility.

Data were collected using electronic data extraction forms (Microsoft Excel; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) modified from our previous systematic reviews.2,3 Data items included study and participant demographics, clinical context (e.g., WLSM, controlled or uncontrolled DCD, or otherwise), and details pertaining to the incidence, monitoring (including cardiac rhythm prior to autoresuscitation event), and identification of autoresuscitation events. Data were extracted from included studies by two independent reviewers and in duplicate. Disagreements were resolved by third reviewer arbitration (J. S. or L. H.) where necessary.

Risk of bias and certainty of evidence assessments

We planned to perform risk of bias and certainty of evidence assessments on the highest levels of evidence among the body of evidence identified in our entire search strategy (i.e., observational studies, randomized, and nonrandomized trials, and excluding case reports/series). Risk of bias was ascertained at the study level and assessed by two reviewers independently and in duplicate. Conflicts were resolved by consensus, with arbitration by a third reviewer if necessary. Assessments were performed using the domains of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, considering: 1) selection of cohorts, 2) comparability of cohorts, and 3) assessment of outcome.19 Given the implicit absence of a comparator group in the studies included in our review, we adapted the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale by excluding the risk of bias domains pertaining to selection of nonexposed cohorts and comparability of cohorts, as has been previously reported.20,21 Consequently, risk of bias was assessed out of a total of six stars with higher scores corresponding to lower risk of bias.

We assessed the certainty in the same aggregate body of evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework, which classifies certainty as very low, low, moderate, or high based on evaluation of risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias.22 We assessed the certainty of evidence for the following outcomes of interest, and separately for the context of controlled and uncontrolled DCD: 1) declaring someone dead who is not yet dead (i.e., false positive; resumption of spontaneous circulation after five minutes observation time) and 2) missing someone who is dead (i.e., false negative; no resumption of spontaneous circulation prior to the end of five minutes observation time).

Data analysis

Characteristics of included studies were summarized descriptively in tables. Binary data were summarized as counts with percentages, and continuous variables were summarized with means and standard deviations (SDs). Where necessary, we calculated means and SDs using the methods proposed by Wan et al.23 based on data provided in studies. Primary outcome data (i.e., observation time following cessation of circulation) was analyzed descriptively and presented in a summary table. Given the maturity of evidence since our last review, we restricted our primary outcome, risk of bias, and certainty in the evidence analyses to the observational studies identified in the entirety of our reviews. A summary of findings table was created to describe the certainty of the evidence for each outcome of interest. Justifications for certainty assessments are described in the table footnotes.

Results

Study identification

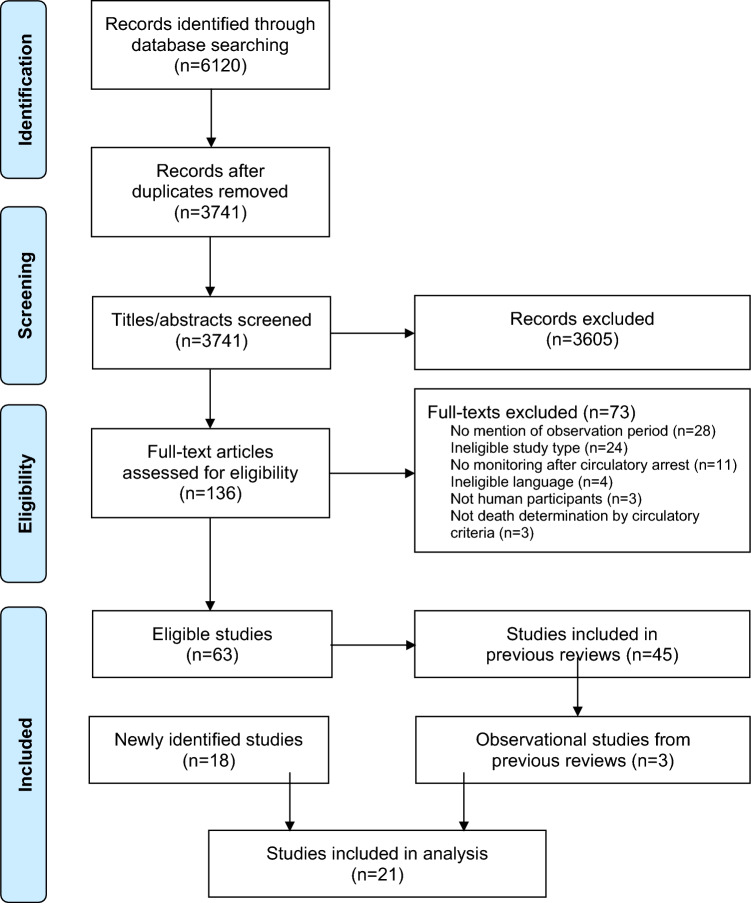

Of 6,120 records identified through the database search (ESM eAppendix 2), we reviewed 3,741 unique citations and assessed 136 full texts for eligibility. We excluded 73 full texts, leaving 63 studies meeting eligibility criteria (Figure). Of these, 45 studies had been included in our previous reviews,2,3 leaving 18 new studies7,8,24–39 identified in this systematic review update. Of these, three case reports were missed by our previous systematic reviews.35,37,38 To assess our primary outcome (i.e., observation time following cessation of circulation), risk of bias, and certainty in evidence to date, we also included the three observational studies40–42 identified prior to this review update in our results synthesis.

Figure.

PRISMA flow diagram. Details of the study selection process in this systematic review

Study characteristics

Of the 18 new studies identified in this updated systematic review, 14 (78%) were case reports26–39 and four (22%) were observational studies.7,8,24,25 Characteristics of the study participants and autoresuscitation events among the 14 case reports are summarized in Table 1. Characteristics of the seven total observational studies (i.e., three identified in previous reviews and four identified in this update) are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects and autoresuscitation events in case reports

| Reference/country (year) |

Population/age | Context | CPR duration (min) | Last cardiac rhythm prior to AR | Time from arrest/CPR cessation to AR (min) |

Type of monitoring at arrest | Continuous monitoring during arrest | Type of monitoring at AR event | Final reported outcome (AR event duration) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bao et al. USA (2021) |

Adult 39 yr |

DCD | n/a | Not reported | 1 | CRM | Yes | CRM |

Died (17 min) |

|

Mullen et al. UK (2021) |

Pediatric 18 months |

OHCA | 10 CPR cycles | Not reported | ~6 | ECG, clinical assessment | No | Clinical assessment | Survived with impairment |

|

Steinhorn et al.* USA (2021) |

Pediatric 16 yr |

WLSM | n/a | Asystole | Several | ECG, IABP | No | ECG | Survived without further impairment |

| 23 months | WLSM | n/a | Not reported | ~14 | Clinical assessment | No | Clinical assessment |

Died (3 hrs 35 min) |

|

|

Sypre et al.* Belgium (2021) |

Adult 66 yr |

IHCA | 32 | PEA | >5 (not further specified) | ECG | Yes | Not reported | Not reported |

|

Zier et al. USA (2021) |

Pediatric 2 yr |

DCD | n/a | Asystole | 2–4 | ECG, IABP | Yes | ECG, IABP |

Died (~ 20 min) |

|

Mahon et al. USA (2020) |

Adult 79 yr |

IHCA | 9 | PEA | ~9 | ECG | No | Clinical assessment |

Died (10 hrs) |

|

Sharma et al. USA (2020) |

Adult 33 yr |

IHCA | 30 | Asystole | 20 | ECG, IABP | No | Clinical assessment |

Died (7 days) |

|

Sprenkeler et al. Netherlands (2019) |

Adult 86 yr |

WLSM | n/a | Asystole | ~4 | ECG | Yes | ECG | Survived without impairment |

|

Pasquier et al. Switzerland (2018) |

Adult 63 yr |

OHCA | 70 | Asystole | ~10 | Not reported | No | Clinical assessment | Survived without impairment |

|

Yerna et al. Belgium (2018) |

Adult 61 yr |

OHCA | 45 | Asystole | 3 | ECG | Yes | ECG, clinical assessment |

Died (~12 hrs) |

|

Spowage- Delaney et al. United Kingdom (2017) |

Adult 66 yr |

OHCA | 45 | PEA | 5 | ECG | Yes | ECG, clinical assessment | Survived without impairment |

|

Sukhyanti et al. India (2016) |

Adult 25 yr |

IHCA | ~40 | Asystole | ~5-7 | ECG, pulse oximetry, noninvasive BP | No | ECG |

Died (4 hrs) |

|

Wilseck et al. USA (2015) |

Adult 50 yr |

IHCA | 30 | Asystole | ~2 | ECG, IABP | Yes | ECG, IABP | Survived with impairment |

|

Vaux et al. France (2013) |

Adult 63 yr |

OHCA | 40 | Asystole | 10 | ECG | No | ECG, clinical assessment |

Died (a few minutes) |

| 78 yr | OHCA | 41 | Asystole | ~2 | ECG | No | ECG, clinical assessment |

Died (5 min) |

*Full data unavailable, published in abstract only

AR = autoresuscitation; BP = blood pressure; CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CRM = cardiorespiratory monitoring (described as blood pressure [not specified if invasive or noninvasive], oxygen saturation, auscultation); DCD = donation after death determination by circulatory criteria; ECG = electrocardiography; IABP = invasive arterial blood pressure; IHCA = in-hospital cardiac arrest; OHCA = out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; PEA = pulseless electrical activity; WLSM = withdrawal of life-sustaining measures

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants and autoresuscitation events in observational studies

| Reference/country (year) |

Sample size AR events/ total |

Population Age, mean (SD) |

CPR duration (min) | Last cardiac rhythm prior to AR | Time from arrest/CPR cessation to AR |

Type of monitoring at arrest | Continuous monitoring during arrest | Type of monitoring at AR event | Final reported outcome (AR event duration) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Withdrawal of Life-Sustaining Measures ± DCD | |||||||||

|

Dhanani et al.* Canada (2021) |

5/631 |

Adult, WLSM ± DCD 65 (15) yr |

Not reported |

1 min– 4 min 20 s |

ECG, IABP | Yes | ECG, IABP |

All died (median 3.9 sec, range 1 sec– 13 min 14 sec) |

|

| 2/32 |

Adult, DCD subgroup 54 (12) yr |

Not reported |

64 sec, 2 min 31 sec |

ECG, IABP | Yes | ECG, IABP | |||

|

Koo et al.† USA (2019) |

7/63 |

Adult, DCD 38 (17) yr |

Asystole |

< 1 min (n = 5) 1–2 min (n = 2) |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

All died (Not reported) |

|

|

Cook et al. Australia (2018) |

5/171 |

Adult, DCD 43 (16) yr |

Asystole |

< 2 min (n = 3) 2–3 min (n = 2) |

IABP | Yes | IABP |

All died (16 min, 10 min [reported only for 2 cases]) |

|

|

Yong et al.‡ Australia (2016) |

2/81 |

Adult, DCD Age not reported (AR patient age range 4–57 yr) |

Asystole | 102 sec; 3 min | ECG, IABP§, pulse oximetry | Yes | ECG, IABP§, pulse oximetry |

All died (108 sec, 3 min) |

|

|

Dhanani et al.‡ Canada (2014) |

0/26 |

Adult, WLSM 62 (15) yr |

n/a | n/a | ECG, IABP | Yes | n/a | n/a | |

| 0/4 |

Pediatric, WLSM 13 (11) months |

n/a | n/a | ECG, IABP | Yes | n/a | n/a | ||

|

Sheth et al.‡ USA (2012) |

0/65 |

Adult, DCD 38 (9) yr |

n/a | n/a | ECG, IABP | Yes | n/a | n/a | |

| 0/8 |

Pediatric, DCD 16 (1) yr |

n/a | n/a | ECG, IABP | Yes | n/a | n/a | ||

| Terminated CPR | |||||||||

|

Kuisma et al. Finland (2017) |

5/840 |

Adult, OHCA Age not reported (AR patient age range 30–97 yr) |

12–31 |

1 asystole 4 PEA |

3–8 min | ECG, capnography, cardiac US | Yes | ECG, capnography, cardiac US |

All died (2 min— 26 hr 20 min) |

*Full study cohort included 631 patients; 480 had complete monitoring, 32 of whom were DCD donors.

†Full data unavailable, published in abstract only

‡Study identified in our previous systematic reviews

§In the patient reported to have autoresuscitation three minutes after circulatory arrest, IABP monitoring was lost because of equipment failure two minutes prior to cessation of ECG so it could not be confirmed that the return of ECG for three minutes was accompanied by a return of circulation

AR = autoresuscitation; CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation; DCD = organ donation after death determination by circulatory criteria; ECG = electrocardiography; IAB = invasive arterial blood pressure; OHCA = out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, PEA = pulseless electrical activity; US = ultrasonography; WLSM = withdrawal of life-sustaining measures.

Case reports

Ten case reports (71%) described autoresuscitation events in a total of 11 patients following unsuccessful CPR.28–30,33–39 Six patients had an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA)29,33,34,37,39 and five an in-hospital cardiac arrest.28,30,35,36,38 Most patients were adults (n = 10; age range, 25–79 yr). The one pediatric case report described an 18 month-old with unsuccessful CPR following OHCA.29 Among these case reports, autoresuscitation events were reported to occur 2–20 min following termination of CPR, with only four of these reporting any continuous vital sign monitoring during circulatory arrest.34,36,38,39 The longest reported time between cessation of circulation and autoresuscitation in patients with continuous monitoring was greater than five minutes (not further specified).36 Four of 11 patients with terminated CPR were reported to have survived following unassisted resumption of spontaneous circulation.29,33,34,38

Four case reports (29%) described five patients (age range, 23 months to 86 yr) with autoresuscitation events following controlled WLSM,26,27,31,32 including two cases during DCD.31,32 Autoresuscitation was reported to occur between one and 14 min following circulatory arrest. Nevertheless, in patients with continuous vital sign monitoring, the longest time to an autoresuscitation event was four minutes. Two patients survived, including a patient with autoresuscitation after “several” minutes of asystole. In the context of potential DCD, two autoresuscitation events were reported occurring after one and two to four minutes of circulatory arrest, respectively.31,32 One adult patient had 17 min of resumption of circulation following which they were deemed ineligible for organ donation.32 The second autoresuscitation event occurred in a pediatric patient with 20 min of resumption of circulation after which they had permanent circulatory arrest and donated kidneys.31

Observation time following cessation of circulation

To evaluate the evidence to support a shorter or longer than five-minute observation time used in death determination by circulatory criteria, we separately analyzed the seven observational studies identified from our entire systematic reviews as they represented the highest level of available evidence. Characteristics and outcomes of these studies are summarized in Table 2. Four studies had a prospective observational design7,8,40,41 and three studies were retrospective.24,25,42 The majority of studies evaluated circulatory arrest following controlled WLSM with or without DCD (n = 6),8,24,25,40–42 and the majority of participants were adults (99%; 1,877/1,889 participants).

Controlled withdrawal of life-sustaining measures with or without organ donation after death determination by circulatory criteria

Following controlled WLSM with or without DCD, 19/1,049 participants were reported to have had an autoresuscitation event (incidence 1.8%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1 to 2.8). The longest duration between circulatory arrest and autoresuscitation was four minutes 20 sec. The largest observational study on autoresuscitation in participants with controlled WLSM (n = 631) defined resumption of cardiac electrical and pulsatile activity as a return of arterial pulse pressure of at least 5 mm Hg corresponding to at least one QRS complex on electrocardiography, after a period of pulse pressure of less than 5 mm Hg for at least 60 sec, as detected by an indwelling arterial pressure catheter monitor.8 Five autoresuscitation events were reported clinically and confirmed retrospectively with analysis of invasive arterial blood pressure waveforms. The retrospective waveform analysis in this study also found an additional 62 events meeting the study criteria for autoresuscitation that were not reported clinically, totalling 67 autoresuscitation events in 480 participants with complete waveform data.8 Similarly, a pilot observational study including participants with controlled WLSM reported no clinically observed autoresuscitation events, but identified four occurrences of spontaneous return of invasive arterial blood pressure waveforms.41 Only one of these events resulted in a measurable blood pressure, and the longest duration to any spontaneous return of arterial waveform was 89 sec following circulatory arrest.41 Of note, no participants with autoresuscitation in any of the included studies survived.

Three studies reported more than one autoresuscitation event among a total of ten participants,8,24,25 with no subsequent autoresuscitation occurring outside of a five-minute observation period. In the specific context of DCD, we identified five observational studies enrolling a total of 420 potential DCD participants, including eight pediatric participants.8,24,25,40,42 Among these, 16 participants (incidence, 3.8%; 95% CI, 2.2 to 6.1) experienced autoresuscitation events, all within three minutes following circulatory arrest.

Uncontrolled organ donation after death determination by circulatory criteria

There was no direct evidence pertaining to autoresuscitation in uncontrolled DCD patients. Nevertheless, we identified one prospective observational study that enrolled 840 participants in the context of unsuccessful CPR following OHCA.7 Five autoresuscitation events were reported (incidence, 0.6%; 95% CI, 0.2 to 1.4). The duration of CPR prior to these events ranged from 12 to 31 min, and both the initial and last cardiac rhythm prior to autoresuscitation was asystole (n = 1) or pulseless electrical activity (n = 4). Three participants experienced autoresuscitation at three minutes after CPR termination, one patient at six minutes and one patient at eight minutes. Autoresuscitation events in the latter two participants were confounded by failure to disconnect the ventilation bag from the endotracheal tube, and continuation of a norepinephrine infusion after cessation of CPR, respectively. No patients with autoresuscitation survived.

Pediatrics

Two studies included pediatric participants (n = 12) in the context of WLSM. One study included infants and toddlers with WLSM only (n = 4; mean [SD] age, 13 [11] months),41 and another teenagers with potential DCD (n = 8; mean [SD] age, 16 [1] yr).40 No autoresuscitation events were observed among pediatric participants.

Risk of bias and certainty of evidence

Risk of bias assessments were performed for the seven included observational studies and are summarized in Table 3. The certainty of evidence by GRADE criteria is summarized in Table 4.

Table 3.

Risk of bias in included studies

| Study (year) |

Selection of Cohort | Outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of exposed cohort (maximum: ★) |

Ascertainment of exposure (maximum: ★) |

Outcome of interest not present at start of study (maximum: ★) |

Assessment of outcome (maximum: ★) |

Length of follow-up (maximum: ★) |

Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts (maximum: ★) |

Total Score |

|

|

Dhanani et al. (2021) |

★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 6 |

|

Koo et al. (2019) |

★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 4 | ||

|

Cook et al. (2018) |

★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 4 | ||

|

Kuisma et al. (2017) |

★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 6 |

|

Yong et al. (2016) |

★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 4 | ||

|

Dhanani et al. (2014) |

★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 6 |

|

Sheth et al. (2012) |

★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 4 | ||

Modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale risk of bias assessment. All included studies were prospective or retrospective single cohorts; therefore, the domains of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale pertaining to “selection of the nonexposed cohort” and “comparability of cohorts” were not applicable

Table 4.

Summary of findings and certainty of evidence assessment

| Outcomes | Certainty assessment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Other factors | |

| Controlled DCD | ||||||

| False positive* | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not detected | Strong association‡ |

| False negative† | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not detected | Strong association‡ |

| Uncontrolled DCD | ||||||

| False positive* | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious§ | Not serious | Not detected | None |

| False negative† | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious§ | Not serious | Not detected | None |

| Outcomes | n | Effect | Certainty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (studies) | |||

| Controlled DCD | |||

| False positive* | 1,049 (6) | Nineteen clinically reported and confirmed autoresuscitation events among 1,037 adults with circulatory arrest following WLSM. No autoresuscitation events were reported in the 12 pediatric patients in these studies. In Dhanani et al. 2021 (631), an additional 62 autoresuscitation events were reported based on retrospective review of invasive arterial blood pressure and ECG waveforms among 480 patients who had complete data. All events occurred within 5 minutes of circulatory arrest (maximum, 4 minutes 20 seconds). Studies including controlled DCD patients (n = 420) reported 16 autoresuscitation events (maximum, 3 minutes). |

Moderate ⊕⊕⊕○ |

| False negative† |

Moderate ⊕⊕⊕○ |

||

| Uncontrolled DCD | |||

| False positive* | 840 (1) | Five autoresuscitation events in 840 OHCA patients with unsuccessful resuscitation, with an incidence of 5.95/1,000 (95% CI, 2.1 to 14.3). Three events occurred, one at 3 minutes after terminated resuscitation, one at 6 minutes, and one at 8 minutes. |

Low ⊕⊕○○ |

| False negative† |

Low ⊕⊕○○ |

||

*Declaring someone dead who is not yet dead (i.e., resumption of spontaneous circulation after 5 minutes observation time).

†Missing someone who is dead (i.e., no resumption of spontaneous circulation prior to end of 5 minutes observation time).

‡Upgraded given large series of representative patients allowing inference of a strong association.

§Although study cohort was OHCA patients with unsuccessful resuscitation and did not include any uncontrolled DCD patients, indirectness was not rated down because of minimal perceived differences between the two contexts.

DCD = organ donation after circulatory determination of death; ECG = electrocardiogram; OHCA = out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; WLSM = withdrawal of life-sustaining measures

Discussion

This updated systematic review on autoresuscitation following circulatory arrest shows the following key findings. First, 18 new studies were identified that evaluated or described autoresuscitation events, consisting of 14 case reports and four observational studies. In the entirety of our reviews, seven observational studies evaluating autoresuscitation were published. Second, in the context of controlled WLSM with or without DCD, a five-minute observation time was sufficient for death determination by circulatory criteria (moderate certainty). This evidence considers a large, multicentred observational study of 631 patients with continuous vital sign monitoring showing that the longest time to any autoresuscitation event was four minutes and 20 sec. Finally, data in the context of pediatrics and uncontrolled DCD remain limited, consisting largely of case reports. Two observational studies have shown no autoresuscitation events in a small sample of pediatric participants (n = 12). One large observational study evaluated autoresuscitation after unsuccessful CPR, suggesting that a five-minute observation time may be insufficient for death determination in uncontrolled DCD (low certainty).

Concerns regarding unassisted return of spontaneous circulation after circulatory arrest, termed autoresuscitation, initially emerged from reports in patients with cardiac arrest where resuscitation was unsuccessful and CPR was terminated. As organ donation after controlled WLSM and DCD increased in clinical practice, physiologic research on autoresuscitation was imperative to ensuring that the ethical foundation of deceased donation adhered to the dead donor rule.1 In death determination by circulatory criteria, circulatory arrest is considered permanent following an observation period for unassisted return of spontaneous circulation.

This updated review confirms that autoresuscitation research has grown in both quantity and quality. Several observational studies have shown that, while autoresuscitation does occur in the context of controlled WLSM or DCD, it has not been observed beyond a five-minute observation period following circulatory arrest. The large multicentre study by Dhanani et al. reported that among the 13 autoresuscitation events clinically described by bedside observation in 631 patients, only five were corroborated by invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring waveform analysis.8 Retrospective waveform analysis also showed resumption in circulatory activity in 14% of participants, albeit using a conservative definition of at least 5 mm Hg intra-arterial pulse pressure.8 A pilot study by Dhanani et al. also identified four events of spontaneous return of invasive arterial blood pressure waveform among 30 patients without any corresponding clinically observed autoresuscitation events, though only one of these waveforms resulted in a measurable blood pressure by the monitoring device.41 This finding underscores the importance of appropriate vital sign monitoring in death determination by circulatory criteria. Further, it identifies the potential bias in case reports reporting autoresuscitation beyond a five-minute observation period in controlled WLSM due to variability in observation and monitoring techniques. Studies included in this systematic review also reported that patients may have multiple transient resumptions in circulation or pulsatile activity, but none of these occurred outside of any subsequent five-minute observation time. As a result, this updated systematic review significantly impacts the clarity and certainty regarding unassisted return of spontaneous circulation in controlled DCD.

We did not identify any direct evidence pertaining to autoresuscitation in uncontrolled DCD—an organ donation practice which is still limited internationally.43 Nevertheless, this updated review identified several new case reports and a large observation study evaluating patients with terminated CPR following cardiac arrest. While indirect, this context is comparable to uncontrolled DCD. These studies showed that autoresuscitation may occur after five minutes of observation following terminated CPR, occurring up to 20 min after terminated CPR in one case report.28 A large observational study supported these case report observations though important confounders were identified in the two autoresuscitation events occurring beyond five minutes of observation, leading to low certainty in the evidence.7 One patient (autoresuscitation at six minutes) did not have the ventilation bag disconnected from the endotracheal tube, and another patient (autoresuscitation at eight minutes) had continuation of norepinephrine infusion after CPR cessation.7 From our previous systematic reviews, evidence on autoresuscitation following terminated CPR was limited to case reports only.2,3 Acknowledging important variability in observation and vital sign monitoring procedures, these case reports also showed that unassisted return of spontaneous circulation may be observed after five minutes in this context.2,3 There is also limited information allowing for comparison of autoresuscitation outcomes with respect to cardiac rhythm leading to cardiac arrest (i.e., ventricular fibrillation/tachycardia versus asystole/pulseless electrical activity). Therefore, an observation time longer than five minutes may be needed for death determination by circulatory criteria in uncontrolled DCD.

Pediatric DCD is still a growing practice as most pediatric organ donors have death determination by neurologic criteria.6 Evidence on autoresuscitation in pediatric patients is limited to case reports and two observational studies enrolling a total of 12 pediatric patients following WLSM, including eight potential pediatric DCD patients.26,31,40,41 Similarly, we did not identify any studies pertaining to the neonatal population or those with MAiD. These represent cohorts that may merit further study to increase clarity and certainty in death determination following circulatory arrest.

Strengths of this systematic review include its rigorous methodology with a comprehensive and extensive literature search, improving upon our previous reviews. We conducted a comprehensive analysis of the highest level of evidence across the entire published research to date, including certainty in evidence assessments using the GRADE framework. Given the ethical limitations preventing a randomized controlled trial on this subject, this review stands as the most comprehensive summary of literature on autoresuscitation, including recently published large observational studies. The main limitations of this review include its risk of bias assessment, given the paucity of risk of bias appraisal tools to evaluate studies of outcomes associated with a specific exposure.44 In the absence of a preferred appraisal tool for the observational studies included in this review, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was modified as a means to provide some assessment of risk of bias. While this modification has been previously reported,20,21 we acknowledge potential limitations. Additionally, we excluded studies not published in English or French for feasibility, recognizing that these results may miss reports of autoresuscitation events described in other languages.

Conclusion

The breadth of research evidence pertaining to autoresuscitation after circulatory arrest has grown in both quantity and quality, with several observational studies including patients with WLSM, DCD, and failed CPR. Given the importance placed on the timely determination of death as an irreversible process, this systematic review indicates that a five-minute observation time is sufficient and necessary for death determination by circulatory criteria in the context of controlled WLSM and DCD in adults. For uncontrolled DCD, several case reports and a large observational study suggest that a longer observation time may be required to accurately determine death by circulatory criteria. Data pertaining to pediatrics, neonates, and MAiD are limited or absent and may merit further study.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Jonah Shemie, Laura Hornby, Gurmeet Singh, Shauna Matheson, and Sonny Dhanani designed the study. David J. Zorko, Jonah Shemie, Laura Hornby, Gurmeet Singh, Shauna Matheson, Ryan Sandarage, Krista Wollny, Lalida Kongkiattikul, and Sonny Dhanani assessed citations for eligibility. David J. Zorko, Jonah Shemie, and Laura Hornby abstracted data, assessed risk of bias, and checked data for accuracy. David J. Zorko, Jonah Shemie, Laura Hornby, and Sonny Dhanani conducted analyses. All authors contributed to interpretation of the data. David J. Zorko and Jonah Shemie contributed equally as first authors. All authors read the manuscript and provided feedback.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their appreciation to Robin Featherstone, MLIS, for her help in updating the search strategy, and Dagmara Chojecki, MLIS, for providing peer review of the search strategy. The authors also express their gratitude to Katie O’Hearn and Dr. James Dayre McNally for their support in using the insightScope platform.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. The use of insightScope in this systematic review was financially supported by funding provided by Health Canada through the Organ Donation and Transplantation Collaborative.

Funding statement

This work was conducted as part of the project entitled, “A Brain-Based Definition of Death and Criteria for its Determination After Arrest of Circulation or Neurologic Function in Canada,” made possible through a financial contribution from Health Canada through the Organ Donation and Transplantation Collaborative and developed in collaboration with the Canadian Critical Care Society, Canadian Blood Services, and the Canadian Medical Association. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada, the Canadian Critical Care Society, Canadian Blood Services, or the Canadian Medical Association.

Prior conference presentations

Critical Care Canada Forum (November 2022).

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Helen Opdam, Guest Editor, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Footnotes

insightScope. The future of systematic reviews, 2020. Available from URL: https://insightscope.ca (accessed October 2022).

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

David J. Zorko and Jonah Shemie have contributed equally as co-first authors.

References

- 1.Lizza JP. Why DCD donors are dead. J Med Philos. 2020;45:42–60. doi: 10.1093/jmp/jhz030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hornby K, Hornby L, Shemie SD. A systematic review of autoresuscitation after cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1246–1253. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0b013e3181d8caaa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hornby L, Dhanani S, Shemie SD. Update of a systematic review of autoresuscitation after cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:e268–e272. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000002920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon L, Pasquier M, Brugger H, Paal P. Autoresuscitation (Lazarus phenomenon) after termination of cardiopulmonary resuscitation - a scoping review. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2020;28:14. doi: 10.1186/s13049-019-0685-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shemie SD, Baker AJ, Knoll G, et al. National recommendations for donation after cardiocirculatory death in Canada: donation after cardiocirculatory death in Canada. CMAJ. 2006;175:S1. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss MJ, Hornby L, Witteman W, Shemie SD. Pediatric donation after circulatory determination of death: a scoping review. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17:e87–108. doi: 10.1097/pcc.0000000000000602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuisma M, Salo A, Puolakka J, et al. Delayed return of spontaneous circulation (the Lazarus phenomenon) after cessation of out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2017;118:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhanani S, Hornby L, van Beinum A, et al. Resumption of cardiac activity after withdrawal of life-sustaining measures. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:345–352. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2022713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canadian Blood Services. ODTC project snapshot: developing a brain-based definition of death and evidence- based criteria for its determination after arrest of circulation or neurologic function in Canada, 2021. Available from URL: https://professionaleducation.blood.ca/en/organs-and-tissues/practices-and-guidelines/current-projects/organ-donation-and-transplantation (accessed October 2022).

- 10.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372: n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Thuong M, Ruiz A, Evrard P, et al. New classification of donation after circulatory death donors definitions and terminology. Transpl Int. 2016;29:749–759. doi: 10.1111/tri.12776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashkanase J, Nama N, Sandarage RV, et al. Identification and evaluation of controlled trials in pediatric cardiology: crowdsourced scoping review and creation of accessible searchable database. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:1795–1804. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nama N, Iliriani K, Xia MY, et al. A pilot validation study of crowdsourcing systematic reviews: update of a searchable database of pediatric clinical trials of high-dose vitamin D. Transl Pediatr 2017; 6: 18–26. 10.21037/tp.2016.12.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Nama N, Sampson M, Barrowman N, et al. Crowdsourcing the citation screening process for systematic reviews: validation study. J Med Internet Res 2019; 21: e12953. 10.2196/12953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Zorko D, McNally JD, Rochwerg B, et al. Pediatric chronic critical illness: protocol for a scoping review. JMIR Res Protoc 2021; 10: e30582. 10.2196/30582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Nama N, Barrowman N, O'Hearn K, Sampson M, Zemek R, McNally JD. Quality control for crowdsourcing citation screening: the importance of assessment number and qualification set size. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;122:160–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Hearn K, Gertsman S, Sampson M, et al. Decontaminating N95 and SN95 masks with ultraviolet germicidal irradiation does not impair mask efficacy and safety. J Hosp Infect. 2020;106:163–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zorko DJ, Gertsman S, O'Hearn K, et al. Decontamination interventions for the reuse of surgical mask personal protective equipment: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect. 2020;106:283–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses, 2000. Available from URL: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed November 2022).

- 20.Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2018;23:60–63. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2017-110853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmitz S, Maguire Á, Morris J, et al. The use of single armed observational data to closing the gap in otherwise disconnected evidence networks: a network meta-analysis in multiple myeloma. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:66. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0509-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011; 64: 401–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koo C, Helmick R, Van Frank K, Gilley K, Eason J. Incidence of autoresuscitation in donation after cardiac death donors. Available from URL: https://atcmeetingabstracts.com/abstract/incidence-of-autoresuscitation-in-donation-after-cardiac-death-donors/ (accessed November 2022).

- 25.Cook DA, Widdicombe N. Audit of ten years of donation after circulatory death experience in Queensland: observations of agonal physiology following withdrawal of cardiorespiratory support. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2018;46:400–403. doi: 10.1177/0310057x1804600409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinhorn D, Calligan AL. Lazarus Syndrome in pediatric hospice care: does it occur and what home hospice providers should know? Am Acad Pediatrics. 2021;147:538–539. doi: 10.1542/peds.147.3MA6.538b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sprenkeler DJ, van Hout GP, Chamuleau SA. Lazarus in asystole: a case report of autoresuscitation after prolonged cardiac arrest. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2019;3:1–5. doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytz134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma M, Chandna M, Nguyen T, et al. When a dead patient is not really dead: Lazarus phenomenon. Case Rep Crit Care. 2020;2020:8841983. doi: 10.1155/2020/8841983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mullen S, Roberts Z, Tuthill D, Owens L, Te Water Naude J, Maguire S Lazarus Syndrome - challenges created by pediatric autoresuscitation. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37:e210–e211. doi: 10.1097/pec.0000000000001593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahon T, Kalakoti P, Conrad SA, Samra NS, Edens MA. Lazarus phenomenon in trauma. Trauma Case Rep 2020; 25: 100280. 10.1016/j.tcr.2020.100280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Zier JL, Newman NA. Unassisted return of spontaneous circulation following withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy during donation after circulatory determination of death in a child. Crit Care Med. 2022;50:e183–e188. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000005273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bao A, Bao S. Pronounced dead twice: what should an attending physician do in between? Am J Case Rep 2021; 22: e930305. 10.12659/ajcr.930305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Pasquier M, de Riedmatten M, Paal P. Autoresuscitation in accidental hypothermia. Am J Med. 2018;131:e367–e368. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spowage-Delaney B, Edmunds CT, Cooper JG. The Lazarus phenomenon: spontaneous cardioversion after termination of resuscitation in a Scottish hospital. BMJ Case Rep 2017; 2017. 10.1136/bcr-2017-219203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Sukhyanti K, ShriKrishan C, Anu K, Ashish D. Lazarus phenomenon revisited: a case of delayed return of spontaneous circulation after carbon dioxide embolism under laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2016;20:338–340. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sypré L, Rongen M. Autoresuscitation after cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a case report. Acta Clin Belg. 2021;76:29–30. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaux J, Revaux F, Hauter A, Chollet-Xemard C, Marty J. Le phénomène de Lazare. Ann Fr Med Urgence. 2013;3:182–183. doi: 10.1007/s13341-013-0284-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilseck Z, Cho K. Spontaneous circulation return after termination of resuscitation efforts for cardiac arrest following embolization of a ruptured common hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm. Gastrointest Interv. 2015;4:55–57. doi: 10.1016/j.gii.2015.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yerna MJ, Tarta CR, Verjans JA, Verjans RA, Aouachria AS. Autoresuscitation after cardiac arrest: the Lazarus phenomenon [French] Louvain Med. 2018;137:708–713. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheth KN, Nutter T, Stein DM, Scalea TM, Bernat JL. Autoresuscitation after asystole in patients being considered for organ donation. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:158–161. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0b013e31822f0b2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dhanani S, Hornby L, Ward R, et al. Vital signs after cardiac arrest following withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy: a multicenter prospective observational study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:2358–2369. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yong SA, D'Souza S, Philpot S, Pilcher DV. The Alfred Hospital experience of resumption of cardiac activity after withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2016;44:605–606. doi: 10.1177/0310057x1604400508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ortega-Deballon I, Hornby L, Shemie SD. Protocols for uncontrolled donation after circulatory death: a systematic review of international guidelines, practices and transplant outcomes. Crit Care. 2015;19:268. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0985-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bero L, Chartres N, Diong J, et al. The risk of bias in observational studies of exposures (ROBINS-E) tool: concerns arising from application to observational studies of exposures. Syst Rev. 2018;7:242. doi: 10.1186/s13643-018-0915-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.