Abstract

Purpose

To synthesize the available evidence comparing noninvasive methods of measuring the cessation of circulation in patients who are potential organ donors undergoing death determination by circulatory criteria (DCC) with the current accepted standard of invasive arterial blood pressure (IAP) monitoring.

Source

We searched (from inception until 27 April 2021) MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. We screened citations and manuscripts independently and in duplicate for eligible studies that compared noninvasive methodologies assessing circulation in patients who were monitored around a period of cessation of circulation. We performed risk of bias assessment, data abstraction, and quality assessment using Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation in duplicate and independently. We presented findings narratively.

Principal findings

We included 21 eligible studies (N = 1,177 patients). Meta-analysis was not possible because of study heterogeneity. We identified low quality evidence from four indirect studies (n = 89) showing pulse palpation is less sensitive and specific than IAP (reported sensitivity range, 0.76–0.90; specificity, 0.41–0.79). Isoelectric electrocardiogram (ECG) had excellent specificity for death (two studies; 0% [0/510]), but likely increases the average time to death determination (moderate quality evidence). We are uncertain whether point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) pulse check, cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), or POCUS cardiac motion assessment are accurate tests for the determination of circulatory cessation (very low-quality evidence).

Conclusion

There is insufficient evidence that ECG, POCUS pulse check, cerebral NIRS, or POCUS cardiac motion assessment are superior or equivalent to IAP for DCC in the setting of organ donation. Isoelectric ECG is specific but can increase the time needed to determine death. Point-of-care ultrasound techniques are emerging therapies with promising initial data but are limited by indirectness and imprecision.

Study registration

PROSPERO (CRD42021258936); first submitted 16 June 2021.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12630-023-02424-3.

Keywords: circulation, death, invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring, organ donation, perfusion

Résumé

Objectif

Synthétiser les données probantes disponibles comparant les méthodes non invasives de mesure de l’arrêt de la circulation chez les patients qui sont des donneurs d’organes potentiels soumis à une détermination du décès selon des critères circulatoires (DCC) avec la norme actuellement acceptée de surveillance invasive de la tension artérielle (TA).

Sources

Nous avons mené des recherches dans les bases de données MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science et le registre Cochrane des essais contrôlés de leur création jusqu’au 27 avril 2021. Nous avons examiné les citations et les manuscrits de manière indépendante et en double pour en tirer les études éligibles qui comparaient des méthodologies non invasives d’évaluation de la circulation chez les patients qui étaient sous surveillance avant, pendant et après une période d’arrêt de la circulation. Nous avons réalisé l’évaluation du risque de biais, l’extraction des données et l’évaluation de la qualité en nous fondant sur la méthodologie GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) en double et de manière indépendante. Nous présentons les résultats de façon narrative.

Constatations principales

Nous avons inclus 21 études éligibles (N = 1177 patients). Une méta-analyse n’a pas été possible en raison de l’hétérogénéité des études. Nous avons identifié des données de faible qualité issues de quatre études indirectes (n = 89) montrant que la palpation du pouls est moins sensible et spécifique que la mesure invasive de la TA (plage de sensibilité rapportée, 0,76-0,90; spécificité, 0,41-0,79). L’électrocardiogramme (ECG) isoélectrique avait une excellente spécificité pour le décès (deux études; 0 % [0/510]), mais augmente probablement le délai moyen avant la détermination du décès (données probantes de qualité modérée). Nous ne savons pas si la vérification du pouls par échographie ciblée (POCUS), la spectroscopie proche infrarouge (SPIR) cérébrale ou l’évaluation ciblée (POCUS) des mouvements cardiaques sont des examens précis pour la détermination de l’arrêt circulatoire (données probantes de très faible qualité).

Conclusion

Il n’y a pas suffisamment de données probantes pour affirmer que l’ECG, la vérification ciblée du pouls, la SPIR cérébrale ou l’évaluation ciblée des mouvements cardiaques sont supérieurs ou équivalents à la mesure invasive de la TA pour un DCC dans le cadre du don d’organes. L’ECG isoélectrique est spécifique, mais peut augmenter le délai nécessaire avant de déterminer le décès. Les techniques d’échographie ciblée sont des thérapies émergentes avec des données initiales prometteuses, mais elles sont limitées par leur caractère indirect et l’imprécision de l’examen.

Enregistrement de l’étude

PROSPERO (CRD42021258936); soumis pour la première fois le 16 juin 2021.

Although transplantation remains an effective intervention for many end-stage organ diseases, a significant limitation is the scarcity of available donations. Death can be determined using two types of criteria: death determination by circulatory criteria (DCC) and death determination by neurologic criteria (DNC). When circulatory criteria are used to determine death, the donation process is known as donation after circulatory determination of death (DCD) and has also been referred to as donation after circulatory death, donation after cardiac death, or non-heart-beating organ donation. Donation after circulatory determination of death can further be classified as either uncontrolled or controlled.1 Uncontrolled DCD refers to the process whereby organs are recovered from those who die following an unexpected cardiac arrest with unsuccessful resuscitation. Controlled DCD refers to cases where organ donors die following planned withdrawal of life-sustaining measures (WLSM) or medical assistance in dying (MAID). Regardless, for a donation to ensue, there must be adherence to the “dead donor” rule; the donor must be dead before retrieval of their organs.2 For DCD, death determination is based on the permanent cessation of circulation. Since increased time can cause loss of a donation opportunity or impact organ viability for transplant, death determination for DCD must be done in a timely fashion.

The criteria for determining death in DCD have been established in guidelines.3–5 In both adult and pediatric Canadian guidelines, the preferred method to confirm the absence of blood pressure is invasive arterial blood pressure (IAP) monitoring.4,5 In the development of the updated Canadian Clinical Practive Guideline for death determination featured in this month’s Special Issue of the Journal,6 it was recognized that in many situations IAP is uncommon, such as DCD in children and patients donating after MAID. Clinical studies outside of the context of DCD have examined other monitoring methods to confirm the absence of circulation using palpable pulse, electrocardiograms (ECGs), ultrasound images of arterial flow or cardiac motion, and regional tissue oximetry as less invasive alternatives to IAP monitoring. Our specific research question was, “In patients who are potential organ donors undergoing DCC, can alternate noninvasive means of measuring circulation versus IAP be used to diagnose cessation of circulation?” The purpose of this systematic review is to summarize the literature, as it relates to DCD, of patients monitored around a period of cessation of circulation, on the diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive methods for measuring circulation compared with the current gold standard (IAP monitoring).

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021258936); first submitted 16 June 2021. This review was part of a larger project to establish an updated clinical practice guideline for death determination in collaboration with the Canadian Critical Care Society, Canadian Medical Association, and the Canadian Blood Services. This manuscript adhers to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) for Diagnostic Test Accuracy checklist and guidelines.7

Eligibility criteria

We included studies on patients who were monitored around a period of cessation of circulation by comparing methods to measure circulation. Our target population was potential DCD donors (both controlled and uncontrolled), but we did not restrict our search to this population. We included all ages of participants and types of settings. We included studies on extracorporeal support if they compared methods that assess for the presence or absence of a pulse.

The intervention of interest was any noninvasive method for the measurement of circulation and could include any combination of palpable pulse, electrocardiogram, ultrasonography, or other techniques.

Our reference standard of interest was IAP monitoring, but we included any reference test that measured circulation. We were intentionally broad with our inclusion criteria given the anticipated paucity of research in this area, coupled with our desire to include data using other reference tests to provide evolving evidence that may inform future research.

We excluded animal studies. We accepted all study designs, except for commentaries, editorials, and ethical analyses. Studies had to compare methodologies for determining circulation, so studies predicting future return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) were excluded.

Although Sarti et al.8 focused on a period of hypotension and not cessation of circulation, we included this study to provide valuable specificity data in pediatrics that also used the target reference standard, IAP monitoring.

Information sources

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from inception to 27 April 2021. The latest search was completed on 27 April 2021.

Search strategy

We developed the search strategy with an information specialist (R. F.) in consultation with content experts, and this strategy was then peer-reviewed by a second information specialist (D. C.) not involved in the study using the 2020 Cochrane protocol peer review assessment form (available at community.cochrane.org). Keywords and related terms such as “heart arrest,” “measurement,” and “blood pressure” were used. The full search strategy can be found in the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM], eAppendices 1–4. We restricted our inclusion to articles in English or French.

Selection process

Retrieved citations were imported into EndNote™ X9 (Clarivate™, London, UK) for reference management and duplicates were removed automatically. Titles and abstracts were screened independently and in duplicate using a standardized study eligibility form through InsightScope (https://insightscope.ca/), a crowdsourcing platform for reviews, using predetermined selection criteria. Prospective reviewers from the platform must have obtained a total sensitivity of 0.8 after screening a set of 100 test citations. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion and a third reviewer if necessary. The same procedure was followed for full-text screening. See ESM eAppendices 5 and 6.

Data collection and items

Reviewers (J. A. K., A.-V. N., L. H.) abstracted relevant study details onto a form (Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) independently and in duplicate. We abstracted data including study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, recruitment period, outcomes, details on the index, and reference test (e.g., definitions of circulation, thresholds). Any statistical comparisons between measurement methods were recorded for each study (e.g., sensitivity, specificity). We calculated sensitivity and/or specificity if not reported by the authors and there were sufficient data to do so. The data abstraction items can be found in ESM eAppendices 7–28. Our target condition was absence of circulation. Throughout this review, sensitivity was defined as the proportion of patients with absence of circulation that were correctly identified as not having circulation; taken in the death determination context, determining someone dead who is dead. Specificity was defined as the proportion of patients with present circulation that were correctly identified as having circulation; taken in the death determination context, determining someone alive who is alive.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias was assessed independently in duplicate for our study question specifically using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) tool.9 We reviewed four domains: 1) patient selection; 2) index tests; 3) reference standard; and 4) flow and timing. Conflicts were resolved through discussion and, if needed, a third assessor. QUADAS-2 was a post hoc choice to be specific to diagnostic accuracy studies.

Synthesis methods

Meta-analysis was not possible because of heterogeneity in study design, index and reference tests, statistical analysis, and outcomes. We summarized with descriptive synthesis. Data on our population of interest (potential DCD donors, including patients undergoing withdrawal of life-sustaining measures [WLST]) were considered direct evidence while data on other populations (e.g., cardiopulmonary bypass) were considered indirect evidence.

Certainty assessment and reporting bias assessment

We assessed quality in the same aggregate body of evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework, which classifies quality as very low, low, moderate, or high based on evaluation of risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias.10 Publication bias was assessed in accordance with the GRADE recommendations.

Our study team deemed false positives (determining someone dead who is alive) a critical outcome because this would violate the dead donor rule. A test with perfect specificity (for pulselessness) will never classify an alive person as dead; therefore, a very highly specific test is critical to protect the dead donor rule.

Our study team deemed false negatives (determining someone alive who is dead) an important outcome. A highly sensitive test (for pulselessness) will almost never classify a dead person as alive; therefore, a highly sensitive test minimizes diagnostic delays that can compromise a donation opportunity or reduce organ viability for transplant.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

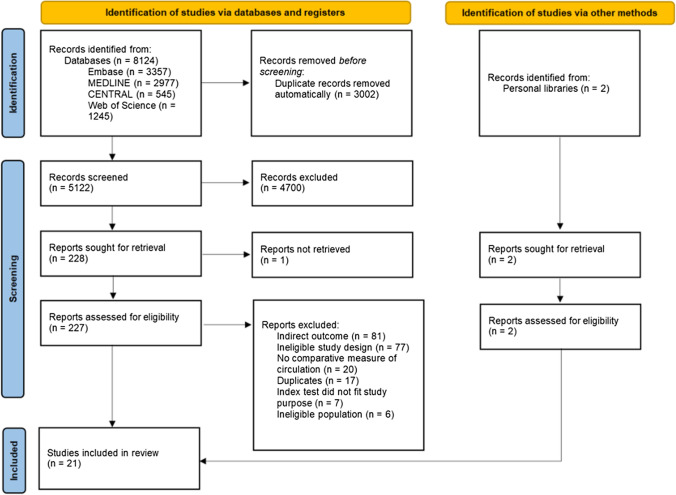

The study selection process is shown in the Figure. Our search identified 5,122 unique citations, 227 of which were reviewed in full text. We included 21 studies (N = 1,177 patients). Of these studies, ten addressed the target question with IAP as reference (10/21, 47%) in either a potential donation or WLST population (3/21, 14%), or in another population (7/21, 33%). Most studies were European (9/21, 43%), small (18/21, 86% under 50 patients), and prospective cohort designs (12/21, 57%) (Table 1). We found no studies that were designed to directly compare different devices with IAP monitoring for death determination in potential DCD donors. We found five studies related to the use of noninvasive modalities in a pediatric population, and no studies specific to death determination for uncontrolled DCD or DCD following MAID.

Figure.

Study selection shown through the PRISMA flow diagram

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study characteristics N = 21 studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr), study mean or median | Publication date | ||

| 0–18 | 4/21 (19%) | Inception to 2005 | 4/21 (19%) |

| 19–40 | 0/21 (0%) | 2005–2021 | 17/21 (81%) |

| 41–60 | 5/21 (24%) | ||

| 61–80 | 10/21 (47%) | ||

| 81+ | 1/21 (5%) | ||

| NR | 1/21 (5%) | ||

| Region | Patient sample size | ||

| Europe | 9/21 (43%) | ≤ 50 | 18/21 (85%) |

| North America | 7/21 (33%) | 51–100 | 0/21 (0%) |

| Australia and New Zealand | 4/21 (19%) | 101–299 | 2/21 (10%) |

| Multiple regions | 1/21 (5%) | ≥ 300 | 1/21 (5%) |

| Index test | Reference test | ||

| Cerebral NIRS | 7/21 (33%) | Invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring | 10/21 (47%) |

| Ultrasound pulse (Doppler, 2D) | 5/21 (24%) | Palpable pulse | 3/21 (14%) |

| Palpable pulse | 5/21 (19%) | Clinical death exam | 3/21 (14%) |

| Electrocardiogram | 3/21 (14%) | Circulatory arresta | 3/21 (14%) |

| Ultrasound cardiac motion | 2/21c (10%) | Cessation of cerebral blood flowb | 1/21 (5%) |

| CNAP | 1/21 (5%) | Ultrasound cardiac motion | 1/21c (5%) |

| Patient characteristics | Design | ||

| Intraoperative | 8/21 (38%) | Prospective cohort | 12/21 (56%) |

| CPR | 4/21 (19%) | Case study/series | 4/21 (19%) |

| Withdrawal of life support | 3/21 (14%) | Case control | 2/21 (10%) |

| Circulatory death | 3/21 (14%) | Randomized control trial | 2/21 (10%) |

| Extracorporeal life support | 2/21 (10%) | Retrospective cohort | 1/21 (5%) |

| Brain-dead patients | 1/21 (5%) | ||

Values are n/total N (%)

aTwo studies used a period of induced ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia

bDefined as a heart rate of less than 20 bpm and a variable blood pressure threshold

cZengin et al.14 reported cardiac motion as a reference test, listed in this table as both an index and reference test

2D = two-dimensional; CNAP = continuous noninvasive arterial blood pressure; CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation; NIRS = near-infrared spectroscopy; NR = not reported; VF = ventricular fibrillation

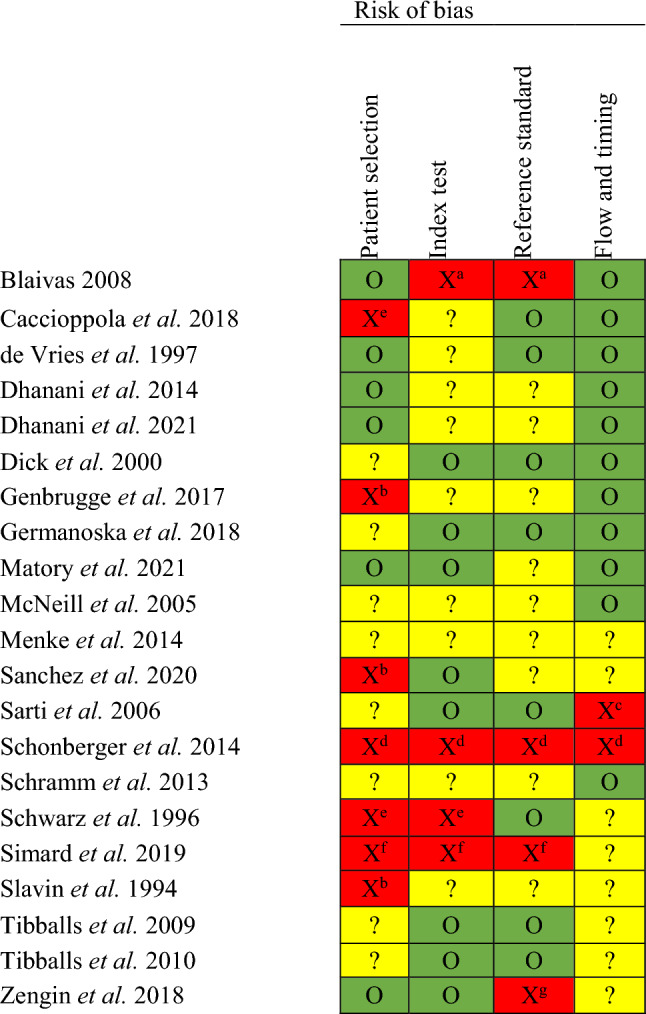

Risk of bias and quality of the evidence

The risk of bias for individual studies is summarized in Table 2. Each index test category is described narratively below, and the quality of the evidence for each modality is summarized in Table 3. Diagnostic accuracy measures are summarized in Table 4.

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment using the QUADAS-2 tool

Legend: O (green) = low; ? (yellow) = unclear; X (red) = high risk of bias.

Unclear risk of bias (?) is due to insufficient details within the publication to complete the QUADAS-2 tool for that domain.

High risk of bias is justified below

aIndex test not reported as blinded to reference test. Pulse palpation is used as reference test without invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring

bConvenience sample used

cNot all patients in the analysis. Excluded if they became hemodynamically unstable

dCase series. Unblinded and no standardization of test procedures. The time duration for tests were not standardized and tests were repeated if results were discrepant. Reference test was palpable pulse.

eCase-control study, unblinded

fConvenience sample, unblinded. Palpable pulse was the reference test without invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring.

gCardiac ultrasound was used as the reference test in statistical analysis without invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring.

QUADAS-2 = Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2

Table 3.

Summary of findings and quality of evidence assessment

| Outcomes | Quality assessment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Other factors | |

| Palpable pulse | ||||||

| False positive | Not seriousa | Not serious | Seriousb | Not serious | None | None |

| False negative | Not seriousa | Not serious | Seriousb | Not serious | None | None |

| POCUS pulse check | ||||||

| False positive | Seriousd | Not serious | Very seriousb | Seriousc | None | None |

| False negative | Seriousd | Not serious | Very seriousb | Seriousc | None | None |

| ECG | ||||||

| False positive | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Strong association |

| False negative | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Strong association |

| POCUS cardiac motion assessment | ||||||

| False positive | Seriouse | Not serious | Seriousb | Seriousc | None | None |

| False negative | Seriouse | Not serious | Seriousb | Seriousc | None | None |

| Cerebral NIRS (rSO2) | ||||||

| False positive | Seriousf | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousc | None | None |

| False negative | Seriousf | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousc | None | None |

| Outcome | ng | Study design | Effect (descriptive) | Quality | Importance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies (patients) | |||||

| Palpable pulse | |||||

| False positive |

4g (89) |

1 RCT11 |

Overall specificity for pulselessness was reported as between 0.41 and 0.798,11–13 and overall sensitivity reported as between 0.76 and 0.90 in different patient populations.11–13 |

Low ⊕⊕◯◯ |

Critical |

| False negative |

3g (49) |

1 RCT11 |

Low ⊕⊕◯◯ |

Important | |

| POCUS pulse check | |||||

| False positive |

2g (43) |

1 prospective cohort16 |

One RCT reported that the mean [IQR] arterial pressure for detection by 2D US was 62 mm Hg [49–74] and 56 mm Hg [52–73] for Doppler.15 One observational study reported overall specificity of 2D US for pulselessness as 0.91 (95% CI, 0.89 to 0.93).16 One observational study reported overall sensitivity of 2D US for pulselessness as 0.90 (95% CI, 0.86 to 0.93).16 |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

Critical |

| False negative |

1g (23) |

1 RCT15 1 prospective cohort16 |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

Important | |

| ECG | |||||

| False positive |

2g (510) |

2 prospective cohort19,20 | Two prospective cohort studies reported that arterial line pulse did not cease before electrical asystole (0/510, 0%).19,20 The largest observational study reported the median time from final pulse to final QRS complex as 3 min 37 sec (range, 0 sec–83 min 28 sec) and lasting more than 30 minutes in 7% of cases (33/480).20 |

Moderate ⊕⊕⊕◯ |

Critical |

| False negative |

Moderate ⊕⊕⊕◯ |

Important | |||

| POCUS cardiac motion assessment | |||||

| False positive |

0g (0) |

NA (no studies used IAP monitoring as reference test) | No direct evidence or comparison with invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring. |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

Critical |

| False negative |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

Important | |||

| NIRS | |||||

| False positive |

3g (30) |

1 case series23 |

No rSO2 threshold has been suggested in the literature. Two studies have shown correlation between rSO2 and perfusion23,27 In one observational study (n = 6), the absolute rSO2 value at the moment death had a broad range.23 |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

Critical |

| False negative |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯ |

Important | |||

aOne study had a high risk of bias; however, it was consistent with the findings of the other studies

bNo direct studies on our population of interest. For POCUS pulse, there was additional indirectness in that participants interpreted prerecorded videos

cSmall number of events and inability to meta-analyze

dConvenience sample used for Sanchez et al

eConcern that reference standard may not correctly classify patients

fConcerns with patient selection, case-control design, and lack of blinding

gStudies with a reference standard other than invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring were excluded

CI = confidence interval; ECG = electrocardiogram; false positive = determining someone dead who is alive; false negative = determining someone alive who is dead; NA = not applicable; NIRS = near-infrared spectroscopy; POCUS = point-of-care ultrasound; RCT = randomized controlled trial; rSO2 = regional cerebral oxygen saturation

Table 4.

Sensitivity and specificity of noninvasive tests compared with invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring for the diagnosis of cessation of circulation

| Index test | Population | Sensitivitya | Specificityb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palpable pulse |

Cardiac bypass11 Intraoperative8 |

90%11 86%12 76%13 |

55%11 41–65%c,8 64%12 79%13 |

| POCUS pulse check: Doppler | Cardiac bypass15 | NA | 100%d,15 |

| POCUS pulse check: 2D | Cardiac bypass15,16 | 90%16 |

100%d,15 91%16 |

| ECG | WLST in ICU19,20 | NA |

100%d,19 100%d,20 |

| POCUS cardiac motion assessment |

No available measure of diagnostic accuracy compared with invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring |

||

| Cerebral NIRS | |||

aOur target condition is absence of circulation. Sensitivity was defined as the proportion of patients with absence of circulation that were correctly identified as not having circulation; in other words, taken in the death determination context, correctly determining someone dead who is dead. A highly sensitive test has low false negatives (determining someone alive who is dead) and can reduce delays in death determination

bSpecificity was defined as the proportion of patients with circulation that were correctly identified as having circulation; in other words, taken in the death determination context, correctly determining someone alive who is alive. A very highly specific test will have very low false positives (determining someone dead who is alive) and is critical to protect the dead donor rule

cSpecificity varied by the site of pulse check

dCalculated by our study team. All cases of present pulse were identified as true negative by index test

2D = two-dimensional; ECG = electrocardiogram; ECLS = extracorporeal life support; ICU = intensive care unit; NA = not available; NIRS = near-infrared spectroscopy; POCUS = point-of-care ultrasound; WLST = withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy

Palpable pulse

No studies directly addressed the diagnostic accuracy of palpable pulse in the population of interest. Five prospective studies provided indirect evidence on the accuracy of palpable pulse: three in pediatric patients on extracorporeal life support (ECLS) or during surgery, and two in adult patients during cardiac bypass or cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).8,11–14

Invasive arterial blood pressure reference test

One randomized controlled trial (RCT) (Dick et al. 2000, n = 206 ambulance personnel and lay people, n = 16 patients) assessed pulse during hypotension or pulselessness of adult patients on cardiopulmonary bypass during cardiac surgery.11 In patients with activity during IAP monitoring, 45% (66/147) of participants did not clinically detect a carotid pulse. Fully trained medical personnel (n = 9) showed a specificity of 89% for the manual diagnoses of pulselessness. Two observational studies in pediatrics assessed pulse detection on ECLS in the intensive care unit (ICU) (total n = 348 medical personnel, 33 patients).12,13 Sensitivity for pulselessness was 76–86% and specificity was 64–79%. One study by Sarti et al. focused on infants and showed that only 41–65% of physicians or nurses detected a pulse by ten seconds as present during IAP monitoring (n = 4 medical personnel, 40 infants undergoing surgery).8 The femoral site was superior to carotid or brachial sites and there was no difference in detection with hypotension.

Alternative reference test

Zengin et al. reported that, in patients with “present circulation” on cardiac ultrasound (defined as cardiac kinetic activity), a pulse could be detected in ten seconds for 0% (none) after the first minute of CPR, 72% after 15 min, and 100% at the end of CPR (n = 137 cardiac arrest adult patients).14

Point-of-care ultrasound pulse check

No studies directly addressed the diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) pulse check in the population of interest. One RCT, one prospective study, and two case series provided indirect evidence in the cardiac arrest with CPR or cardiac bypass population.14–18 No studies examined children.

Invasive arterial blood pressure reference test

One pilot RCT (Germanoska et al. 2018, n = 3 physicians, 20 patients) assessed the physician’s ability to identify pulsatile flow in recorded ultrasound videos of the carotid artery of adults undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass compared with IAP monitoring.15 The median [interquartile range (IQR)] delay of ultrasound detection was 245–40 sec for two-dimensional (2D) visual assessment without doppler and 52–17 sec for colour doppler. In this study, colour doppler ultrasound detected pulse faster and at a lower mean arterial pressure (MAP) than 2D assessment did, but was not as reliable as 2D assessment.15 Sanchez et al. examined the accuracy of 2D ultrasound of the carotid artery using portable ultrasound in adults undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass compared with IAP monitoring (n = 46 physicians, 23 patients).16 With a ten-second assessment time, sensitivity for pulselessness was 90% (95% confidence interval [CI], 86 to 93) and specificity was 91% (95% CI, 89 to 93). Pulse detection was higher in the high-systolic blood pressure (SBP) group (median SBP, 120 mm Hg). Both studies used “arterial wave” as the reference standard and did not specify a minimum pulse pressure.

Alternative reference test

One observational study and two case series compared 2D or Doppler POCUS of arteries to palpable pulse but did not compare arterial waveforms.14,17,18

Isoelectric electrocardiogram

We identified direct evidence on our population of interest from two observational studies assessing ECG following WLST19,20 and indirect evidence from one retrospective study on cardiac death in the ICU.21

Invasive arterial blood pressure reference test

Dhanani et al. conducted a large international observational study of 631 adults (n = 480 with waveform analysis) dying in the ICU after WLSM.20 One-third of the patient population was DCD eligible (32%, 205/631). An isoelectric ECG, when compared with an invasive arterial pulse pressure of at least 5 mm Hg, occurred before the last pulse in 0% of patients (0/480), simultaneously or within two sec in 19% (93/480), and after more than 30 min in 7% (33/480). The median time from the final pulse to the final QRS complex was 3 min 37 sec (range, 0 sec–83 min 28 sec). A smaller previous study (Dhanani et al. 2014, n = 30, 26 adults and four children) similarly showed that isoelectric ECG always occurred simultaneously or after cessation of pulse pressure during IAP monitoring.19 In 10% of cases, isoelectric ECG did not occur until up to 30 min after cessation of pulse pressure (3/30, one adult and two children). The four children in this study had an isoelectric ECG that followed the last pulse by 0 sec (simultaneous), 11 min 11 sec, 27 min 42 sec, and 36 min 29 sec.

Alternative reference test

Comparably to the two Dhanani et al. studies,19,20 a retrospective study reported that the last QRS complex in the ECG occurred simultaneously or after “cessation of cerebral blood flow” as defined by study authors (Matory et al., n = 19, cardiac death in a neurologic ICU).21

Point-of-care ultrasound cardiac motion assessment

No studies directly addressed the diagnostic accuracy of POCUS cardiac motion in the population of interest, and no studies compared this with IAP. We identified indirect evidence from two observational studies on POCUS cardiac motion assessment in cardiac arrest patients (Zengin et al.,14 n = 137 and Blaivas,22 n = 226). The authors did not report sensitivity or specificity.14,22 Cardiac wall motion was recorded as either present or absent (binary). We did not identify any eligible studies on other POCUS cardiac features, such as aortic valve opening. In one study, cardiac ultrasound itself was used as the reference standard for palpable pulse without comparison with IAP monitoring, so the diagnostic accuracy of cardiac ultrasound data were not available (Zengin et al.).14 The authors concluded that cardiac ultrasound may be more accurate than pulse palpation and Doppler POCUS pulse. Blaivas also found a significant discrepancy between palpation and cardiac ultrasound, with no palpable pulse in 47% of cardiac ultrasound assessments that were “felt to likely generate a detectable blood pressure.”22

Cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy

We identified direct evidence on our population of interest from a pilot study on cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) (n = 6, Genbrugge et al.).23 Indirect evidence is from one reported case (n = 1, Slavin et al.),24 two case-control studies,25,26 two observational studies during defibrillator implantation,27,28 and one pediatric study.29 No measures of diagnostic accuracy were reported and no threshold for NIRS was suggested.

Invasive arterial blood pressure reference test

Genbrugge et al. compared regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2) using NIRS to IAP in adults dying after WLSM (n = 6).23 Although rSO2 and MAP were positively correlated, there was a broad range of rSO2 values at death, defined as asystole (median [IQR] rSO2, 33%7–40).

Alternative reference test

One case-control study compared the cerebral oximetry of adults with cardiac death to healthy volunteers (Schwarz et al., n = 18 cases, 15 controls).25 Although the mean (standard deviation) values were significantly different (cases, 51.0% [26.8] vs controls, 68.4% [5.2]; P = 0.029), 6/18 (33%) of the dead adults had rSO2 values within a healthy range (rSO2 ≥ 60%). The second case-control study assessed ultrasound-tagged NIRS detection of cerebral blood flow and found false positive flow detection in all 11 of the brain-dead patients confirmed to have no flow on ancillary neuroimaging (Caccioppola et al., n = 20 healthy and n = 20 brain-dead patients).26 Menke et al. analyzed a subgroup of four children with hypothermic circulatory arrest during cardiac surgery and identified variability in the initial NIRS (54–69%), the decay (t1/2 = 5.2–9.0 min) and the nadir (51–59%) (n = 4, Menke et al.).29 Cerebral perfusion pressure correlated positively with rSO2 in the multivariable model (P < 0.01), but MAP and pulse pressure were not directly compared.29 In two observational studies on cardiac arrest in adults undergoing defibrillator implantation, rSO2 values decreased during functional cardiac arrest with induced ventricular fibrillation and/or ventricular tachycardia (n = 13, de Vries et al.27 and n = 11, McNeill et al.28).

Continuous noninvasive arterial blood pressure

We identified one prospective cohort study on adults during aortic valve implantation that compared continuous non-IAP (CNAP) with IAP monitoring (n = 33 patients).30 This device was composed of encircling finger cuffs and used the volume clamp method to create a continuous pressure waveform. There was mean blood pressure agreement within 15 mm Hg for 82.2% of the time (95% CI, 81.9 to 82.4). During rapid pacing with severe hypotension and recovery, there was no substantial difference in time to detection of hypotension or recovery.

Discussion

In this systematic review on diagnostic test accuracy for cessation of circulation during death determination, we identified 21 studies evaluating six different noninvasive index tests (palpable pulse, POCUS pulse check, ECG, POCUS cardiac motion assessment, cerebral NIRS, and CNAP) with very low to moderate quality of evidence. Ten studies addressed the target question with IAP monitoring as reference (10/21, 47%). Our findings show insufficient evidence to support the use of any other diagnostic method as equivalent or superior to IAP monitoring for the determination of death in potential DCD donors. Isoelectric ECG had zero false positive events (determining someone dead who is not), but likely delays the time to death determination. For the purpose of DCD, ECG may be appropriate to use in specific contexts such as pediatric DCD and DCD following MAID. Point-of-care ultrasound assessment of pulse and cardiac motion are emerging therapies, but the body of evidence is currently limited by indirectness and imprecision. Although the evidence is limited, there are data suggesting that palpable pulse and NIRS should not be used for DCC (low and very low quality) in potential DCD donors. We found limited or no evidence for specific subgroups (children, MAID, uncontrolled DCD).

The last Canadian adult DCD guideline published in 2006 states that IAP monitoring is the “preferred method to confirm the absence of blood pressure.”4 Subsequently, Canadian pediatric guidelines in 2017 also recommended the use of IAP monitoring for DCC.5 European recommendations for uncontrolled DCD have suggested determining death using ECG or alternatively, echocardiography or IAP “in case of electro-mechanical dissociation.”31 In some countries’ guidelines, the method is not defined, or they state that any of the three previously mentioned techniques can be used.1 This review is driven by consideration of the potential negative impacts of the use of IAP monitoring in the context of DCD; it is invasive, may be technically challenging to obtain, especially in pediatrics, and requires trained personnel as well as a hospital setting to insert and monitor. There are certain situations, such as MAID, where the patient may choose environments without invasive monitoring to die or may be able to make an informed decision preferring alternative methods.

Pulse palpation requires no additional equipment, but had unacceptably low specificity in all studies (four studies; range, 0.41–0.79; low quality evidence).8,11–13 Diagnostic tests with low specificity would have higher false positives (determining someone dead who is alive), which we deemed a critical outcome as this could violate the dead donor rule. In contrast to pulse palpation, evidence for the use of isoelectric ECG included more robust, multicentre prospective studies and zero false positives (0%, 0/510 patients, two studies).19,20 There was a strong and consistent association that, although the specificity was excellent, the use of isoelectric ECG delays the time to death determination. The median time for this delay in the largest (n = 480) included study was 3 min 37 sec (range, 0 sec–83 min 28 sec).20 A longer warm ischemia time may come at the cost of graft function if isoelectric ECG is used.32 Nevertheless, the priority to avoid false positives (determining someone dead who is alive) outweighs the impact on warm ischemia times. The two ECG studies were in the setting of WLSM. The duration between loss of pulsatile pressure and an isoelectric ECG in MAID may be shorter than seen in WLSM associated with medication administration for MAID (such as bupivacaine or potassium chloride). Indeed, warm ischemia times for MAID are reported to be shorter compared with conventional DCD donors.33–35 Medical assistance in dying patients may be a population in which the use of ECG is a suitable alternative given patient preference for noninvasive monitoring if the method of MAID includes medication causing rapid electrocardiographic arrest.

Besides MAID, situations may occur with neonates and pediatric patients where IAP may not be present. Invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring in children may be more technically challenging given smaller patient sizes and high rates of arterial line malfunction.36 As pediatric guidelines evolve, there is a balance in allowing some flexibility in monitoring while still ensuring safeguards. Family members have described the lost opportunity of DCD as “a waste of precious life-giving organs and hospital resources.”37 In pediatrics, use of ECG may be an appropriate alternative where IAP monitoring is not technically feasible.

Point-of-care ultrasound has become a common part of many clinical assessments. Nevertheless, the results of our study suggest that its use cannot be recommended given that data are limited because IAP monitoring was not included as a reference, event numbers were small, studies were on a cardiac bypass or cardiac arrest population, and/or videos were only reviewed and not also acquired in real-time. There was imprecision due to a low number of events. Point-of-care ultrasound techniques also have real-world challenges such as the requirement for training, maintenance of competence, need for standards for interpretation, and time demands on these trained individuals. There is a larger body of evidence assessing POCUS techniques for the prediction of ROSC and survival.38,39 Tsou et al. meta-analyzed 15 studies and reported that spontaneous cardiac movement had a pooled sensitivity of 0.95 (95% CI, 0.72 to 0.99) and specificity of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.63 to 0.91) in predicting ROSC during cardiac arrest, with a positive likelihood ratio of 4.8 (95% CI, 2.5 to 9.4) and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.06 (95% CI, 0.01 to 0.39).39 These studies on ROSC predict a future event and have limited application to the question on real-time cessation of circulation.

Death determination by circulatory criteria and DNC are aligned towards a single brain-based definition of death, recognizing a common biomedical pathway of death.40–42 In our review, we assessed evidence on cerebral NIRS as a potential noninvasive modality for DCC. Although a correlation was identified between NIRS and blood pressure, there was a concerning overlap between baseline saturation and saturation either during cessation of circulation or in patients already determined dead by cardiac criteria.23–25,27–29 Given this, NIRS likely has poor discrimination for DCC (three studies, n = 30 patients, very low-quality evidence).

Our study is strengthened by the comprehensive search strategy and an a priori protocol. We assessed the studies’ risk of bias using a standardized tool and performed the quality of evidence assessment using GRADE methodology. Nevertheless, there are several important limitations. First, none of the studies included were specifically designed to compare noninvasive methods with IAP monitoring in the context of DCD. Second, the landscape of research we found generally consisted of small, observational studies, often further limited by a case-control or unblinded design. Third, only half of the included studies used IAP monitoring as the reference standard (10/21, 47%), and few defined what their threshold for pulse pressure was. Fourth, only 14% (3/21) of the studies included potential DCD candidates or WLST; no studies included potential MAID or uncontrolled DCD candidates. Finally, our search had language restrictions. Future research should continue to assess POCUS methods, compare IAP monitoring and ECG in subgroups of uncontrolled DCD and MAID, increase representation of pediatric patients, assess the success and complication rates of IAP monitoring, assess the effect of arterial cathether location (e.g., central vs peripheral), and explore other creative noninvasive options such as CNAP.

Conclusion

There is insufficient evidence to support the use of a noninvasive method as equivalent or superior to IAP for DCC in potential DCD donors. Isoelectric ECG is specific but can increase the time to determine death (moderate quality evidence). Electrocardiography may be appropriate in specific contexts of DCD when IAP monitoring is not possible, such as MAID and pediatric DCD. This systematic review process was part of a larger project and helped inform the updated 2023 “Canadian Clinical Practice Guideline for a brain-based definition of death and criteria for its determination after arrest of circulation or neurologic function” in this Special Issue of the Journal.6

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Laura Hornby, Sonny Dhanani, Christopher J. Doig, Joann Kawchuk, and Mypinder Sekhon conceptualized and designed the study. Jennifer A. Klowak, Anna-Lisa V. Nguyen, Abdullah Malik, Laura Hornby, and Sonny Dhanani screened citations. Jennifer A. Klowak, Laura Hornby, and Anna-Lisa V. Nguyen abstracted data and assessed risk of bias. Jennifer A. Klowak, Christopher J. Doig, Joann Kawchuk, Laura Hornby, Mypinder Sekhon, and Sonny Dhanani synthesized and interpreted the data, and provided critical revisions for scientific content. Jennifer A. Klowak, Anna-Lisa V. Nguyen, Laura Hornby, and Sonny Dhanani contributed to the drafting of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their appreciation to Robin Featherstone, MLIS, for developing the search strategy; Dagmara Chojecki, MLIS, for providing peer review of the search strategy; and Dr. Bram Rochwerg for methodological support. The authors also express their gratitude to Katie O’Hearn and Dr. James Dayre McNally for their support in using the InsightScope platform. Finally, the study team would like to thank the following for their contributions to citation screening: Nedaa Aldairi, Conall Francoeur, Supun Kotteduwa Jayawarden, Ryan Sandarage, and Belinda Yee.

Disclosures

Laura Hornby is a paid consultant for Canadian Blood Services. Dr. Sonny Dhanani is an Ontario Health hospital donation physician.

Funding statement

This work was conducted as part of the project entitled “A Brain-Based Definition of Death and Criteria for its Determination After Arrest of Circulation or Neurologic Function in Canada,” made possible through a financial contribution from Health Canada through the Organ Donation and Transplantation Collaborative and developed in collaboration with the Canadian Critical Care Society, Canadian Blood Services, and the Canadian Medical Association. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada, the Canadian Critical Care Society, Canadian Blood Services, or the Canadian Medical Association.

Prior conference presentations

This work was presented at the Critical Care Canada Forum in November 2022 (Toronto, ON, Canada) both as a poster presentation by Dr. Jennifer A. Klowak entitled “Monitoring cessation of circulation for death determination by circulatory criteria: a systematic review,” and also briefly summarized as part of an oral presentation by Dr. Gurmeet Singh entitled “Overview of death by circulatory criteria.”

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Maureen Meade, Guest Editor, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ortega-Deballon I, Hornby L, Shemie SD. Protocols for uncontrolled donation after circulatory death: a systematic review of international guidelines, practices and transplant outcomes. Crit Care. 2015;19:268. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0985-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Girlanda R. Deceased organ donation for transplantation: challenges and opportunities. World J Transplant. 2016;6:451–459. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v6.i3.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhanani S, Hornby L, Ward R, Shemie S. Variability in the determination of death after cardiac arrest: a review of guidelines and statements. J Intensive Care Med. 2012;27:238–252. doi: 10.1177/0885066610396993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shemie SD, Baker AJ, Knoll G, et al. National recommendations for donation after cardiocirculatory death in Canada: donation after cardiocirculatory death in Canada. CMAJ. 2006;175:S1. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss MJ, Hornby L, Rochwerg B, et al. Canadian guidelines for controlled pediatric donation after circulatory determination of death—summary report. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18:1035–1046. doi: 10.1097/pcc.0000000000001320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shemie SD, Wilson LC, Hornby L, et al. A brain-based definition of death and criteria for its determination after arrest of circulation or neurologic function in Canada: a 2023 Clinical Practice Guideline. Can J Anesth 2023; 10.1007/s12630-023-02431-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Salameh JP, Bossuyt PM, McGrath TA, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies (PRISMA-DTA): explanation, elaboration, and checklist. BMJ 2020; 370: m2632. 10.1136/bmj.m2632 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Sarti A, Savron F, Ronfani L, Pelizzo G, Barbi E. Comparison of three sites to check the pulse and count heart rate in hypotensive infants. Paediatr Anaesth. 2006;16:394–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2005.01803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011; 64: 401–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Dick WF, Eberle B, Wisser G, Schneider T. The carotid pulse check revisited: what if there is no pulse? Crit Care Med. 2000;28:N183–N185. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200011001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tibballs J, Russell P. Reliability of pulse palpation by healthcare personnel to diagnose paediatric cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2009;80:61–64. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tibballs J, Weeranatna C. The influence of time on the accuracy of healthcare personnel to diagnose paediatric cardiac arrest by pulse palpation. Resuscitation. 2010;81:671–675. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zengin S, Gümüşboğa H, Sabak M, Eren ŞH, Altunbas G, Behçet A. Comparison of manual pulse palpation, cardiac ultrasonography and Doppler ultrasonography to check the pulse in cardiopulmonary arrest patients. Resuscitation. 2018;133:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Germanoska B, Coady M, Ng S, Fermanis G, Miller M. The reliability of carotid ultrasound in determining the return of pulsatile flow: a pilot study. Ultrasound. 2018;26:118–126. doi: 10.1177/1742271x17753467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez S, Miller M, Asha S. Assessing the validity of two-dimensional carotid ultrasound to detect the presence and absence of a pulse. Resuscitation. 2020;157:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schonberger RB, Lampert RJ, Mandel EI, Feinleib J, Gong Z, Honiden S. Handheld Doppler to improve pulse checks during resuscitation of putative pulseless electrical activity arrest. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:1042–1045. doi: 10.1097/aln.0000000000000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simard RD, Unger AG, Betz M, Wu A, Chenkin J. The POCUS pulse check: a case series on a novel method for determining the presence of a pulse using point-of-care ultrasound. J Emerg Med. 2019;56:674–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2019.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhanani S, Hornby L, Ward, et al. Vital signs after cardiac arrest following withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy: a multicenter prospective observational study. Crit Care Med 2014; 42: 2358–69. 10.1097/ccm.0000000000000417 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Dhanani S, Hornby L, van Beinum A, et al. Resumption of cardiac activity after withdrawal of life-sustaining measures. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:345–352. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2022713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matory AL, Alkhachroum A, Chiu WT, et al. Electrocerebral signature of cardiac death. Neurocrit Care. 2021;35:853–861. doi: 10.1007/s12028-021-01233-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blaivas M. 282: discordance between pulse detection and emergent echocardiography findings in adult cardiopulmonary arrest patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:S128. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.06.301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Genbrugge C, Eertmans W, Jans F, Boer W, Dens J, De Deyne C. Regional cerebral saturation monitoring during withdrawal of life support until death. Resuscitation. 2017;121:147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slavin KV, Dujovny M, Ausman JI, Hernandez G, Luer M, Stoddart H. Clinical experience with transcranial cerebral oximetry. Surg Neurol. 1994;42:531–539. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(94)90084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwarz G, Litscher G, Kleinert R, Jobstmann R. Cerebral oximetry in dead subjects. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 1996;8:189–193. doi: 10.1097/00008506-199607000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caccioppola A, Carbonara M, Macrì M, et al. Ultrasound-tagged near-infrared spectroscopy does not disclose absent cerebral circulation in brain-dead adults. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:588–594. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Vries JW, Visser GH, Bakker PF. Neuromonitoring in defibrillation threshold testing. A comparison between EEG, near-infrared spectroscopy and jugular bulb oximetry. J Clin Monit 1997; 13: 303–7. 10.1023/a:1007323823806 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.McNeill E, Gagnon RE, Potts JE, Yeung-Lai-Wah JA, Kerr CR, Sanatani S. Cerebral oxygenation during defibrillator threshold testing of implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28:528–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2005.09518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menke J, Möller G. Cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy correlates to vital parameters during cardiopulmonary bypass surgery in children. Pediatr Cardiol. 2014;35:155–163. doi: 10.1007/s00246-013-0754-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schramm C, Huber A, Plaschke K. The accuracy and responsiveness of continuous noninvasive arterial pressure during rapid ventricular pacing for transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Anesth Analg. 2013;117:76–82. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3182910df5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Domínguez-Gil B, Duranteau J, Mateos A, et al. Uncontrolled donation after circulatory death: European practices and recommendations for the development and optimization of an effective programme. Transpl Int. 2016;29:842–859. doi: 10.1111/tri.12734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heylen L, Pirenne J, Naesens M, Sprangers B, Jochmans I. “Time is tissue”—a minireview on the importance of donor nephrectomy, donor hepatectomy, and implantation times in kidney and liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2021;21:2653–2661. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilbo N, Jochmans I, Jacobs-Tulleneers-Thevissen D, et al. Survival of patients with liver transplants donated after euthanasia, circulatory death, or brain death at a single center in Belgium. JAMA. 2019;322:78–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Raemdonck D, Neyrinck A, Van Cromphaut S, et al. Transplantation of lungs recovered from donors after euthanasia results in excellent long-term outcome. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:S364–S365. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2016.01.1050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Reeven M, Gilbo N, Monbaliu D, et al. Evaluation of liver graft donation after euthanasia. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:917–924. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hebal F, Sparks HT, Rychlik KL, Bone M, Tran S, Barsness KA. Pediatric arterial catheters: complications and associated risk factors. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53:794–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor LJ, Buffington A, Scalea JR, et al. Harms of unsuccessful donation after circulatory death: an exploratory study. Am J Transplant. 2018;18:402–409. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reynolds JC, Issa MS, Nicholson TC, et al. Prognostication with point-of-care echocardiography during cardiac arrest: a systematic review. Resuscitation. 2020;152:56–68. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsou PY, Kurbedin J, Chen YS, et al. Accuracy of point-of-care focused echocardiography in predicting outcome of resuscitation in cardiac arrest patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2017;114:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greer DM, Shemie SD, Lewis A, et al. Determination of brain death/death by neurologic criteria: the World Brain Death Project. JAMA. 2020;324:1078–1097. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Omelianchuk A, Bernat J, Caplan A, et al. Revise the uniform determination of death act to align the law with practice through neurorespiratory criteria. Neurology. 2022;98:532–536. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000200024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shemie SD, Hornby L, Baker A, et al. International guideline development for the determination of death. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:788–797. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3242-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.