Abstract

Background.

IQOS, manufactured by Philip Morris International (PMI), is the highest selling heated tobacco product globally. IQOS went through several regulatory changes in Israel: from no oversight, to minimal tobacco legislation, to progressive legislation that included a partial advertisement ban (exempting print media) and plain packaging. We examined how PMI’s advertising messages changed during these regulatory periods for both IQOS and cigarettes.

Methods.

Content analysis of PMI’s IQOS and cigarette ads was performed using a predefined framework. Ad characteristics included regulatory period, target population, setting, product presentation, age and use restrictions, retail accessibility, additional detail cues (e.g., QR code), and promotions. Ad themes included product features, legislation-related elements, social norms, and comparative claims. Comparisons between IQOS and cigarette ads, and across regulatory periods, were examined using Chi-square test or Fischer’s exact test.

Results.

The dataset included 125 IQOS ads and 71 cigarette ads. IQOS ads featured more age restrictions, retail accessibility, and additional detail cues, compared to cigarette ads (93.6% vs. 16.9%; 56% vs. 0%; and 95.2% vs. 33.8%, p<.001 for all). Cigarette ads featured mostly price promotions (52.1% vs. 10.1% of IQOS ads, p<.001). The main ad themes were technology for IQOS (85.6%) and quality for cigarettes (50.7%). In later (vs. earlier) restrictive regulatory periods, IQOS ads featured more direct comparison to cigarettes, QR codes, indoor settings, and did not feature product packaging.

Conclusions.

IQOS advertisement content shifted as more restrictions went into effect, with several elements used to circumvent legislation. Findings from this study point to the necessity of a complete advertisement ban and ongoing marketing surveillance.

Introduction

Heated tobacco products (HTPs) are relatively new products that heat tobacco sticks which are inserted into an electronic device to produce an aerosol,1, 2 and purportedly intended to reduce exposure to harmful substances relative to cigarettes.1, 2 Globally, there is increasing awareness and ever use of HTPs.3–6 Philip Morris International (PMI)’s IQOS device, with accompanying HEETS tobacco sticks, is the HTP with the largest market share worldwide and is sold in more than 60 countries so far.2, 7 PMI claims that this product targets adult smokers only.8

Israel was among the first countries where IQOS emerged.1 IQOS went through several regulatory changes after entering the Israeli market in December 2016 (Table 1).1, 9, 10 First, IQOS was treated as a consumer product and thus not subject to tobacco regulations, under which cigarette advertisement on TV, radio, and billboards was banned. Then, in 04/2017, IQOS was defined as a tobacco product, subject to the same regulations as cigarettes including a ban on using it in smoke-free areas (e.g., indoor public places). In 03/2019, a partial advertisement ban that excluded print media went into effect for all tobacco products, and in 01/2020 plain packaging and a point-of-sale (POS) display ban were implemented.9, 10

Table 1.

Description of the regulatory periods included in the study

| Regulatory period | Dates | Highlights |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dec 25, 2016 - Apr 1, 2017 | IQOS was released in Israel and was categorized as a consumer product, with no restrictions on advertisements. Restrictions on cigarette advertisement included a ban on TV, radio and billboard advertisements; and a requirement to include specific ministry of health-approved health warning labels in all ads. |

| 2 | Apr 2, 2017 - Mar 7, 2019 | IQOS was declared a tobacco product, resulting in it being regulated the same as cigarettes (including a ban on use in smoke-free areas), with the same restrictions on advertising as cigarettes (not allowed on TV, radio and billboards; and required to include health warning labels within the ads). |

| 3 | Mar 8, 2019 - Jan 7, 2020 | A partial advertisement ban went into effect for all tobacco products (including IQOS and cigarettes), including cigarettes and IQOS (restricting advertising to print media only, limiting each media outlet to one tobacco ad per circulation, and advertisement not permitted in youth-oriented print media). |

| 4 | Jan 8, 2020 - Aug 4, 2020 | Plain packaging and a POS display ban for all tobacco products (including IQOS and cigarettes) went into, with enlarged textual health warning labels (to cover 65% of the packaging). |

Industry marketing aims to identify potential target consumer groups and develop advertising strategies to convince consumers to buy, or at least try, new products.11, 12 Potential consumers are grouped into segments, based on shared characteristics such as demographics, psychographics (e.g., lifestyle, interests, values), or behaviors (e.g., use frequency), to target advertising messages to appeal to these segments.13–16 The tobacco industry has a long-standing history of targeting racial/ethnic minority populations.17–19 However, there are no published data regarding targeting of Israel’s minority populations (e.g. the Arab population).

Advertising messages may try to persuade these targeted consumers to buy by comparing new products to known ones.11, 12 For example, tobacco companies have historically marketed filtered and low-tar cigarettes as healthier alternatives to regular cigarettes, using themes such as health benefits, fame, and freedom – elements that are especially attractive for non-smokers, women, and youth.20 When IQOS first entered the Israeli market, its campaign embodied PMI’s stated vision for a ‘Smoke-free Israel’ and included elements that differentiated IQOS from combustible cigarettes by positioning it as a healthier option.1

Regulatory changes, like those implemented in Israel, likely impact how tobacco companies market their products, particularly newer ones like IQOS. Whether regulatory changes have implications for targeted consumer groups is unknown. In Israel, smoking rates are much higher in the Arab population (Israel’s largest minority group), more specifically among Arab men (38.2% compared to 22.6% of Jewish men).21 Use of IQOS or electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) remains low but is higher among Israel’s Arab population (2.8% vs. 1.2% of the Jewish population).21 If PMI is indeed focusing on harm-reduction for adult smokers as they claim8, this might be reflected through targeting of subpopulations with the highest smoking rates, such as the Arab male population in Israel. In addition, the industry might change or adapt their advertisements in response to regulatory changes using strategies that may circumvent restrictions. For example, in the US, after the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) prohibited using words such as ‘mild’ or ‘light’ in cigarette advertisements, PMI replaced these descriptions in Marlboro ads with colors and filters.22

The uniqueness of the Israeli context offers an unprecedented opportunity to study how PMI positioned IQOS compared to its cigarette brands, particularly in terms of how PMI responded to changes in tobacco legislation across the distinct regulatory periods. In addition, this context provides an opportunity to examine IQOS marketing content across population groups (potential targeted marketing). Thus, this paper aimed to analyze the content of PMI’s IQOS and combustible cigarette brands ads, and identify changes over time (regulatory periods), as well as characterize these ads in relation to targeted population groups in Israel.

Methods

Data collection

Data was provided by Ifat media, a leading media company in Israel. It has contracts with all media outlets in Israel (magazines, newspapers, websites, TV, radio, billboards) and obtains all ads published in them on a regular basis.23 Data included links to paid ads of IQOS, HEETS, and PMI combustible cigarettes, published in all Israeli media outlets, from December 25, 2016 (the date IQOS entered the Israeli market) until August 4, 2020 (the date data were provided). For each ad, data provided by Ifat media included the date it was published, target population group, and name of the media outlet. Ads in all languages were included. Ads linked to invalid or broken websites were excluded.

All ads were reviewed to identify unique ads only; if an ad was of the same product, language, colors, visuals, and message, it was deemed as a duplicate, and therefore removed. One researcher (AK) reviewed all the ads to determine whether they were unique; the list was then examined by another researcher (MR), and discrepancies were discussed with a senior member of the research team (YBZ) until reaching 100% agreement.

Coding

A preliminary coding framework was developed based on other studies,20, 24–26 utilizing both deductive and inductive coding, and covering both the text and visual elements within each ad. Two coders (AK and MR) used the coding framework to independently code a sub-sample of the unique ads (20%, n=23: 15 IQOS ads and 8 cigarette ads). Several changes and additions were made to the preliminary coding framework (e.g., retail accessibility). Discrepancies and any changes were discussed with a senior member of the research team (YBZ). After reaching a 96.3% agreement rate, the final coding framework was then used by one researcher (AK) to code the remaining ads. Coding and calculation of the agreement rate, were conducted using Microsoft Excel v16.16.27. The codes were then divided into ‘ad characteristics’ and specific ‘ad themes’. Ad characteristics included regulatory period, target population, setting, product presentation, and information included in the ad (restrictions, retail accessibility, and promotions). Ad themes included product features, legislation/policy-related elements, social norms, and comparative claims. A detailed explanation of each code is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Ad characteristics and specific ad themes

| Ad characteristics | Definition |

| Regulatory period | Assigned based on the first and last dates the ad was published according to the data in Table 1. Note: Ads could be published in more than one regulatory period. |

| Target population | Determined and provided by Ifat media based on aspects such as the media outlet and ad language. These included the general public [media outlets in Hebrew or English not directed at a specific population group], Arab, Russian or Ultra-orthodox subpopulation. Note: Subpopulations might also use media outlets not specifically directed at them. The same ad could be published in media outlets directed at more than one target population. |

| Setting | Assigned based on whether the product was presented in an indoor or outdoor setting, or neither – on a colored or ambiguous (blurred) background. |

| Product presentation | This was coded in terms of: a) Product packaging - original, plain, both or no packaging; b) HEETS flavor or cigarette sub-brand advertised; c) Whether the product was lit or used within the ad. Note: Model-related variables that indicate specific target groups (e.g., youth, women, etc.) were considered but found to be irrelevant as no models were present in the analyzed ads. |

| Information within the ad | This includes: a) Restrictions - age and/or use restrictions - i.e., 18 and above, for smokers only; b) Retail accessibility - the mention of the number of POS at which the product is sold, or including POS specific locations; c) Additional details cues - these included an IQOS-specific website, a toll-free phone number for the IQOS store, a click button, or QR codes; d) Promotions - either price promotions (e.g., a special price, discount, etc.), and other promotions such as the ability to sample or try IQOS for free, competitions or special events. |

| Ad theme | Description |

| Product features | Including: a) Quality - i.e., high quality, fine cut tobacco, for those who value quality, etc.; b) Popularity - for IQOS: references to the number of product users or countries in which the product is available; for cigarettes: being a well-known brand; c) Style - i.e., stylish, elegant, etc.; d) Easy to use - i.e., explicitly stating that it’s easy to use; e) Innovation - using words such as innovative, novel, revolutionary or stating that the cigarette has a filter or two flavors in the same cigarette; F) Technology - either explicitly by using words such as technology, advanced, upgraded, etc., or implicitly by showing the IQOS device or situating the product close to a smartphone. |

| Legislation or policy | Elements that include specific textual reference to legislation (e.g., IQOS taxation, plain packaging). |

| Social norms | Includes codes such as: a) Everydayness - e.g., showing items normally used on a regular basis such as glasses, laptops, food or beverages; b) Socializing with non-smokers - e.g., a smoker being around non-smokers in any setting, smoking in social events/gatherings; c) Freedom/choice - e.g., references to freedom, choice, ownership, power, defying norms, creating a new world order; d) High social status - as reflected through ad elements such as an expensive setting. |

| Comparative claims | Elements that compare the advertised product to cigarettes (for IQOS: any comparison to cigarettes; for cigarettes, comparison to a different brand or previous version of the same brand). These include: a) Being of the same, similar or better taste - e.g., same known taste, true tobacco taste; b) Claims of reduced smell, no smell or no bad smell - e.g., ‘less smell’, ‘no smell’, ‘smell-free’. IQOS-specific claims include: a) No ash; b) No combustion - e.g., words such as ‘no fire’, ‘no combustion’, or ‘heat-not-burn’; c) No smoke - e.g., ‘no smoke’, ‘less smoke’ or shows IQOS use without producing smoke); d) IQOS being an alternative to smoking; e) IQOS being as satisfying as cigarettes; f) Claims of reduced harm - e.g., IQOS/HEETS containing less harmful or potentially harmful chemicals. |

Data analysis

The data was descriptively analyzed using counts and percentages for IQOS and cigarette ads, and was stratified across regulatory periods and population groups (general public, Arab, Russian, and Ultra-orthodox). Comparison of the study variables between IQOS and cigarette ads, and across regulatory periods, was examined using Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests with Bonferroni correction as appropriate, with p<.05 considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed using SPSS v27.

Results

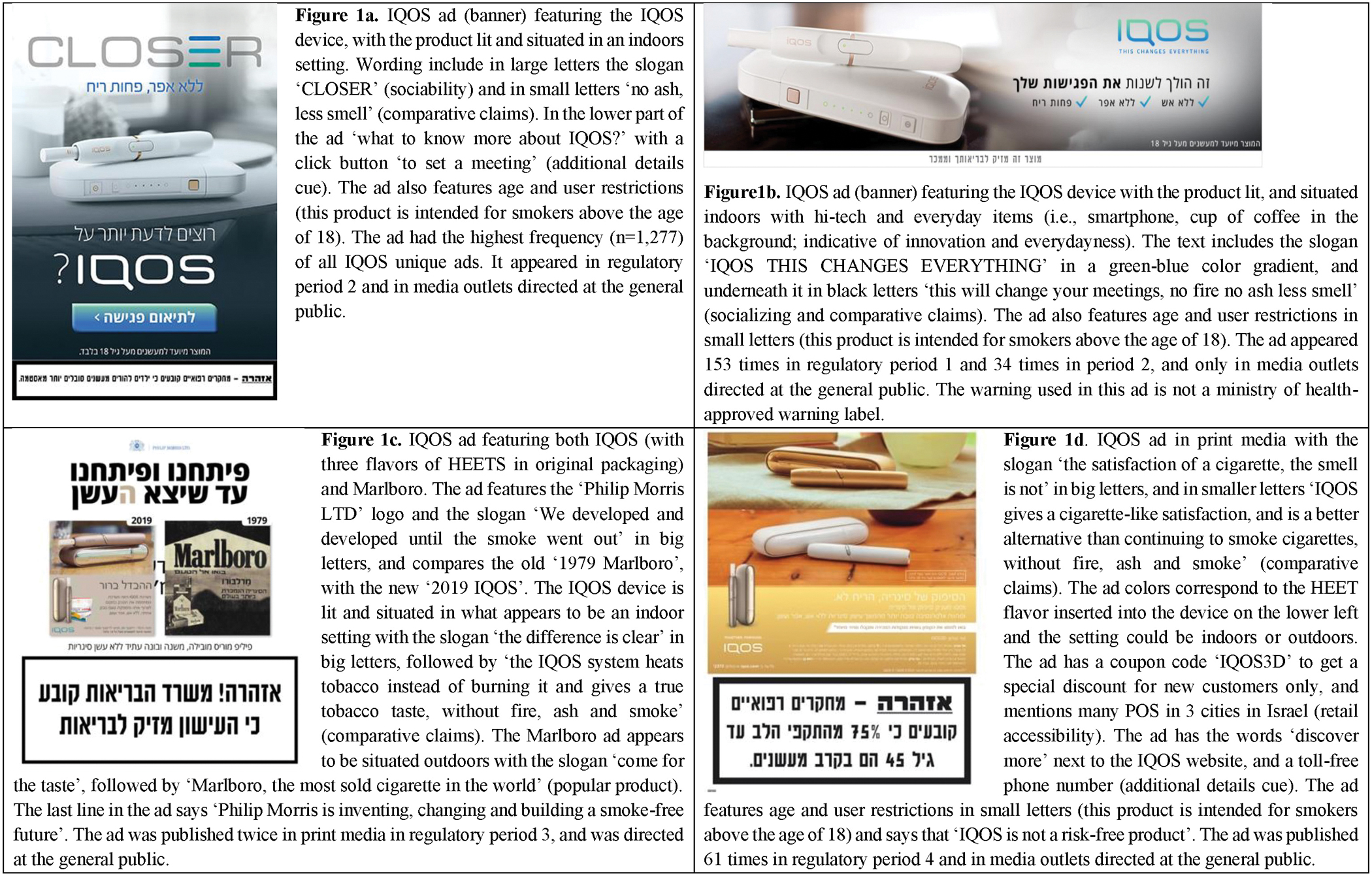

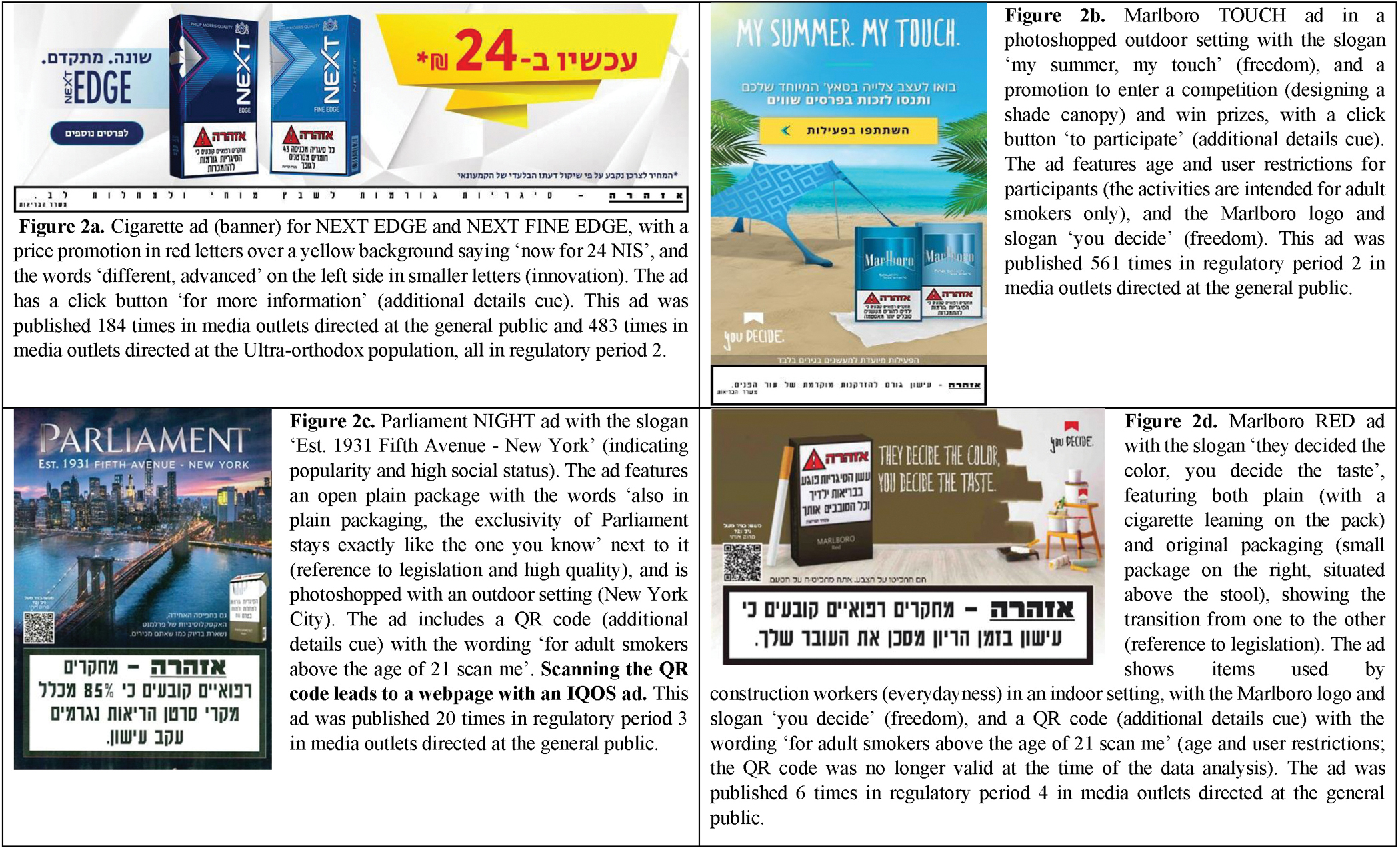

The original dataset included 8,107 IQOS advertisements with 125 unique ads, and 4,788 PMI cigarette advertisements with 71 unique ads. IQOS ad frequency ranged from 1 to 1,277, and cigarette ad frequency ranged from 1 to 677. Examples of unique ads are presented in Figures 1 (IQOS) and 2 (cigarettes). Tables 3 and 4 summarize ad characteristics and ad themes for IQOS and cigarette unique ads. Supplementary file 1 presents a comparison of the ad characteristics and ad themes of IQOS (Table S1) and cigarette ads (Table S2) across the 4 regulatory periods.

Figure 1: Examples of IQOS ads.

Table 3.

PMI IQOS and cigarette unique ad characteristics, Israel, 12/2016–08/2020

| Variables | IQOS ads N=125 N (%) |

Cigarette ads N=71 N (%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Regulatory period * | .05 | ||

| 1 | 7 (5.4) | 0 (0.00) | |

| 2 | 77 (59.2) | 49 (67.1) | |

| 3 | 29 (22.3) | 20 (27.4) | |

| 4 | 17 (l3.l) | 4 (5.5) | |

| Target population * | .02 | ||

| General population | 111 (83.5) | 52 (72.2) | |

| Arab | 4 (3.0) | 8 (11.1) | |

| Russian | 9 (6.8) | 10 (13.9) | |

| Ultra-orthodox | 9 (6.8) | 2 (2.8) | |

| Setting | <.001 | ||

| Indoors | 33 (26.4) | 1 (14) | |

| Outdoor | 19 (15.2) | 10 (14.1) | |

| Colored/ambiguous background | 73 (58.4) | 60 (84.5) | |

| Product presentation: | |||

| Packaging # | 58 (52.3) | 68 (97.1) | <.001 |

| Flavor/sub-brand indicated # | 108 (97.3) | 69 (98.6) | 1.00† |

| Product is lit ¥ | 104 (93.7) | 0 (0.0) | <.001 |

| Information included within the ad: | |||

| Age and user restrictions | 117 (93.6) | 12 (16.9) | <.001 |

| Retail accessibility | 70 (56.0) | 0 (0.0) | <.001 |

| Additional details cue | 119 (95.2) | 24 (33.8) | <.001 |

| Price promotions | 13 (10.4) | 37 (52.1) | <.001 |

| Other promotions $ | 11 (8.8) | 6 (8.5) | .93 |

PMI – Phillip Morris International

Ads could appear in more than one regulatory period and/or target more than one population group. See text for more data.

Pischer’s exact test.

Proportion is calculated from ads that presented HEETS (N=111) or cigarettes (N=70).

Proportion is calculated from ads that presented the IQOS device (N=110) or cigarettes (N=70).

Other promotions in cigarette ads included a competition, invitation to an event or a call to join a membership club, and in IQOS ads also included an event or the ability to try the product for free.

Table 4.

PMI IQOS and Cigarette unique ad themes, Israel, 12/2016–08/2020

| Variables | IQOS ads N=125 N (%) |

Cigarette ads N=71 N (%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Product features: | |||

| Quality | 13 (10.4) | 36 (50.7) | <.001 |

| Popular product | 13 (10.4) | 6 (8.5) | .66 |

| Stylish | 9 (7.2) | 5 (7.0) | .97 |

| Easy to use | 9 (7.2) | 0 (0.0) | .028† |

| Technology | 107 (85.6) | 20 (28.2) | <.001 |

| Innovation | 9 (7.2) | 2 (2.8) | .333† |

| Reference to legislation/policy | 7 (5.6) | 7 (9.9) | .27 |

| Social norms and related factors: | |||

| Presence of everyday items | 32 (25.6) | 4 (5.6) | <.001 |

| Socializing with non-smokers | 11 (8.8) | 0 (0.00) | .008† |

| Freedom/choice | 26 (20.8) | 19 (26.8) | .34 |

| High social status | 13 (10.4) | 11 (15.5) | .30 |

| Special occasion/event | 13 (10.4) | 8 (11.3) | .85 |

| Comparative claims: | 108 (86.4) | 39 (54.9) | <.001 |

| Same/similar/better taste | 12 (11.1) | 20 (51.3) | <.001 |

| No or less smell/no bad smell | 44 (40.7) | 26 (66.6) | .84 |

| IQOS-specific comparative claims | |||

| No ash | 41 (37.9) | ||

| No combustion | 67 (62.0) | ||

| No smoke | 61 (56.5) | N/A | |

| Alternative to smoking | 29 (26.8) | ||

| As satisfying | 32 (29.6) | ||

| No or reduced harm/risk | 5 (4.6) | ||

PMI – Phillip Morris International

Fischer’s exact test.

N/A – Non-applicable.

Ad characteristics

Regulatory period:

Of the 125 IQOS unique ads, 5 were published in more than one regulatory period and 8 were directed at more than one population group. Of the 71 cigarette unique ads, 2 were published in more than one regulatory period and none were directed at more than one population group. For each regulatory period, there were more IQOS unique ads than cigarette ads, with no significant difference in the distribution of ads between regulatory periods (Table 3).

Target population:

Most IQOS (n=111/125) and cigarette ads (n=52/71) were directed at the general public. Four IQOS and 8 cigarette ads were directed at the Arab population, 9 IQOS and 10 cigarette ads at the Russian population, and 9 IQOS and 2 cigarette ads at the Ultra-orthodox population.

Setting:

Less than half of IQOS ads (41.6%, n=52/125) featured IQOS in either an indoor or outdoor setting, of these; 63.5% (n=33/52) were situated indoors. For cigarettes, 11 ads (15.5%, 11/71) featured the product either in an indoor or outdoor setting, of which only one ad featured the product indoors (9.1%, n=1/11) (Table 3). More than a quarter of IQOS ads in regulatory period 2 (when IQOS use was prohibited in indoor smoke-free settings) featured the product in an indoor setting (28.6%, n=22/77, Table S1). A significant increase in such ads was observed in period 4 compared to previous periods (52.9% vs. 28.6% in periods 1 and 2, and 6.9% in period 3, p<.001, Table S1).

Product presentation:

Out of all of IQOS ads, 111 presented HEETS; of these, almost half featured HEETS in their packaging (52.3%, n=58/111). For cigarettes, only one ad did not present the cigarettes themselves; in the remaining ads (n=70), almost all (97.1%; n=68/70) presented the cigarettes in their packaging (p<.001, Table 3). IQOS ads did not feature HEETS in plain packaging, and only 7 cigarette ads showed cigarettes in plain packaging; 6 of which had both the plain and original packaging. Featuring both original and plain packaging in cigarette ads began in regulatory period 3 (November 2019, before plain packaging went into effect – 21.1% of ads, n=4/19), and continued into regulatory period 4 (until March 2020 – 75.0% of ads, n=3/4, Table S1 and S2).

Information included within the ad:

Restrictions: More IQOS ads included any type of restrictions compared to cigarette ads (93.6%, n=117/125 vs. 16.9%, n=12/71, p<.001, Table 3). All IQOS ad restrictions included both age and user restrictions, while cigarette ad restrictions were mainly age restrictions (58.3%, n=7/12).

Retail accessibility: Indicators of retail accessibility were present in 56.0% of IQOS ads (n=70/125), but in zero cigarette ads (p<.001, Table 3). The proportion of IQOS ads that included retail accessibility information increased in regulatory periods 3 and 4 compared to periods 1 and 2 (79.3% and 94.1% of ads, vs. 14.3% and 42.9%, respectively, p<.001, Table S1). Store location was included in a higher proportion of ads targeting the Arab (100.0%, n=4/4) versus Russian (33.3%, n=3/9) and Ultra-orthodox populations (44.4%, n=4/9).

Additional detail cues: More IQOS ads contained additional detail cues compared to cigarettes (95.2% vs. 33.8%, p<.001, Table 3). While such cues increased in proportion in IQOS ads across regulatory periods (from 42.9% of ads in regulatory period 1 to 100.0% of ads in period 4; p<.001, Table S1), their use decreased in cigarette ads (from 42.9% of ads in regulatory period 2 to 25.0% of ads in period 4, p=.02, Table S2). QR codes began appearing in period 3 (when digital advertisement was banned). Only one QR code was still working by the time the data was analyzed; it appeared in a cigarette ad and directed people to a website with an IQOS ad (Figure 2c).

Promotions: More cigarette ads (52.1%) advertised a price promotion compared to IQOS ads (10.4%, p<.001, Table 3).

Figure 2: Examples of PMI cigarette ads.

Ad themes

Product features: The most advertised product feature for IQOS was ‘technology’ (85.6%, n=107/125, overall and for each regulatory period), followed by ‘popularity’ and ‘quality’ (10.4%, n=13/125 for both, Table 4, Table S1). ‘Quality’ was the most advertised product feature for cigarettes (50.7%, n=36/71), followed by ‘technology’ (28.2%, n=20/71, Table 4). Similarly, all ads directed at subpopulations focused on ‘technology’ in IQOS ads and on ‘quality’ in cigarette ads. Cigarette ads directed at the Arab population also focused on ‘taste’.

Reference to legislation/policy: There was no difference between IQOS and cigarette ads in the inclusion of textual cues pertaining to policy or legislation (5.6%, n=7/125 of IQOS ads and 9.9%, n=7/71 of cigarette ads, p=.27, Table 4). These 7 IQOS ads were ‘Smoke-free Israel’ ads calling for IQOS to be regulated differently than other tobacco products (i.e., taxation), 6 of which were published in regulatory period 2 and one in period 3. The 7 cigarette ads appeared in regulatory periods 3 and 4 and included a textual reference to the change in color, with the products in plain packaging. 2 of these were directed at the Arab population, 1 at the Russian and none at the Ultra-orthodox population.

Social norms and related factors: ‘Everydayness’, as reflected by the presence of everyday items, was present in more IQOS (25.6%, n=32/125) compared to cigarette ads (5.6%, n=4/71, p<.001, Table 4). ‘Freedom/choice’ was the second most common social norm portrayed in IQOS ads (20.8%, n=26/125), and the most advertised norm in cigarette ads (26.8%, n=19/71). IQOS ads directed specifically at the Arab population focused on ‘freedom/choice’ (50.0%, n=2/4), whereas in the Russian and Ultra-orthodox populations ads focused on ‘everydayness’ (44.4%, n=4/9 each), and ‘freedom/choice’ was only present in one ad each (11.1%, n=1/9).

Comparative claims were found in most IQOS ads (86.4%, n=108/125); the most frequent claims were ‘no combustion’ (62.0%, n=67/108), ‘no smoke’ (56.5%, n=61/108), ‘no smell/no bad smell’ (40.7%, n=44/108) and ‘no ash’ (37.9%, n=41/108; Table 4). Cigarette ads that included comparative claims (54.9%, n=39/71) only contained two aspects of comparison, focusing on ‘less smell’ (66.6%, n=26/39) and ‘same taste’ (51.3%, n=20/39).

Discussion

The comparative claims found in IQOS’ ads suggest that PMI has attempted to position IQOS as a superior product to cigarettes in the tobacco market in Israel. In line with the diffusion of innovation theory,27 ads that featured the ‘new’ IQOS product focused on its technological aspects, provided information about the product (additional detail cues), provided information on its simplicity of use and access (retail accessibility), and focused on the relative advantage of the product (comparative claims, differentiating IQOS from cigarettes in terms of combustion, smell, ash, etc.). In contrast, ‘old’ cigarette product advertising mainly emphasized price promotions.

Our findings indicate that PMI altered its marketing messages in its paid ads over time, and across regulatory periods. Themes of IQOS being as satisfying and/or an alternative to cigarettes started appearing in regulatory period 2 (after regulating IQOS as a tobacco product), and increased in regulatory periods 3 and 4 (after a partial advertisement ban, POS display ban and plain packaging went into effect). Similar to the current study, our study in the US also found a shift in advertisement messaging after IQOS received the FDA’s Modified Risk Tobacco Product (MRTP) authorization.28 Other shifts in messaging have also been observed with regard to bans on using ‘light’ as a descriptor for cigarettes,29 and in regard to the menthol ban.30 A content analysis of selected cigarette ads in the ‘Times’ magazine between 1929–1984 showed that cigarette companies used ads to deal with growing health concerns, emphasizing innovation such as filters, and removing visible smoke from advertisements.20

The partial advertisement ban in Israel excludes print media, thus allowing PMI to use this advertisement venue as a tool for circumventing legislation. For example, some print media advertisements used QR codes to direct people to additional digital ads after advertisement in digital media was banned. The digital media ban refers to ads that people can access directly (without using a QR code); therefore, this is a gap in the current legislation. Furthermore, as only one ad per media circulation is permitted, using a QR code provides PMI an opportunity to expand the advertisement beyond the one permitted ad. Other instances that highlight the shift in PMI’s advertising content include decreased advertisements that displayed product packaging after plain packaging went into effect, and more ads showing IQOS in an indoor setting after IQOS use was not allowed in enclosed public places. Previous research in Israel focusing on the POS environment has also suggested that PMI is exploiting loopholes in legislation to continue advertisement and promotion of its products.10, 31, 32

Our findings further highlight how quickly marketing strategies evolve when faced with increasing constraints. A complete advertisement ban, banning also advertisement in print media, was recently passed in the Israeli parliament with the caveat that it will go into effect in 2029 (allowing for a seven-year ‘adjusting’ period), thus opening the door for further circumvention and delays.33, 34 An amendment to this legislation, informed by the current study findings, was proposed and approved in May 2022. This amendment includes a ban on using comparative claims (with explicit reference to another product), QR codes and/or coupons, and only allowing products to be shown in plain packaging, during the seven-year adjustment period.33, 34

Although PMI claims to be committed to a smoke-free future with a focus on offering alternatives to adult smokers,8 they continued creating unique ads for combustible cigarettes, innovating and advertising new cigarette products, and had a ‘price promotion’ featured in more than half of cigarette ads. Only one cigarette ad had a cross-promotion to IQOS (via a QR code). Similarly, a study assessing smokeless tobacco POS advertisement found that only 0.3% offered cross promotions with cigarettes.35 On the other hand, cross-promotion has been observed in other tobacco companies’ advertisements for nicotine pouches,36 and in direct mailings.37

PMI has been accused of advertising IQOS to youth and young adults, especially through social media.38 In Israel, recent repeated cross-sectional studies have shown a rise in IQOS experimentation among Jewish youth.39 Our study did not find evidence pointing specifically to youth targeting (through use of young models) or to messages of reduced risk/harm, emphasizing restrictions on age and use and potentially reflecting PMI efforts to reduce accusations and influence marketing regulations.40 However, two elements that have been previously suggested to appeal to youth were indicated: the emphasis on technology and HEETS flavors in the IQOS ads.28,41

Strengths and limitations

This is the first comprehensive analysis of PMI’s IQOS and cigarette ads in Israel, spanning more than three and a half years, and several regulatory changes. Despite the large sample size, very few unique ads were directed at specific population groups, which precluded us from analyzing targeting of specific groups. Our data was retrieved in early August 2020, a few weeks after IQOS received FDA MRTP authorization.42 Evidence from other countries point to potential exploitation of the MRTP language,43–46 which we could not assess due to this short time frame. In addition, our study did not include social media advertisement or hidden informal advertisement (e.g., through influencers).

Conclusion

PMI adapted and modified its advertisement content as more restrictions went into effect, using the print media exemption to circumvent certain elements of the legislation such as plain packaging, ban on digital advertisement, restrictions on number of advertisements, and ban on using IQOS in public indoor settings. Findings from this study point to the necessity of a complete advertisement ban, and ongoing surveillance of tobacco marketing

and advertisement.

Supplementary Material

What this paper adds.

What is already known on this topic?

Phillip Morris International (PMI)’s IQOS is the only heated tobacco product (HTP) in Israel and the HTP with the largest market share globally.

IQOS experienced various regulatory changes in Israel, including a shift from no regulation (i.e., not deemed a tobacco product), to regulation as a tobacco product under minimal oversight (with ban on use in smoke-free areas), to more restrictive and stronger regulation, including an advertisement ban (excluding print media, allowing one ad per media outlet circulation) and subsequently plain packaging.

What this study adds?

After IQOS was regulated as a tobacco product, IQOS ads shifted to include more specific comparisons to combustible cigarettes and additional elements to increase market penetration, such as a focus on technological aspects, retail accessibility, and further information cues.

In response to progressive legislation in Israel, PMI used print media to circumvent legislation by advertising IQOS not in plain packaging, using QR codes (to bypass restrictions on number of advertisements per media outlet) and showing IQOS in indoor settings (to circumvent the ban on using IQOS in indoor smoke-free areas).

How this study might affect research, practice or policy?

Findings underscore the need to specify restrictions related to exempt media channels (e.g., banning the use of QR codes, explicit comparative claims) or to ban such exemptions.

Results also support the need for ongoing surveillance of tobacco companies’ advertisement and marketing strategies as legislation is implemented in order to respond to unanticipated consequences.

Funding:

This research was supported by the National Institute of Health (R01 1R01CA239178-01A1; MPIs: Berg, Levine).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest:

Yael Bar-Zeev has received fees for lectures in the past (2012- July 2019) from Pfizer Ltd, Novartis NCH, and GSK Consumer Health (distributors of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy in Israel). Hagai Levine had received fees for lectures from Pfizer Israel Ltd (distributor of a smoking cessation pharmacotherapy in Israel) in 2017. Lorien Abroms receives royalties for the sale of Text2Quit.

References

- 1.Rosen LJ, Kislev S. IQOS campaign in Israel. Tobacco Control 2018;27:s78–s81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg CJ, Bar-Zeev Y, Levine H. Informing iQOS regulations in the United States: a synthesis of what we know. SAGE Open January 2020. doi: 10.1177/2158244019898823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craig LV, Yoshimi I, Fong GT, et al. Awareness of marketing of heated tobacco products and cigarettes and support for tobacco marketing restrictions in Japan: findings from the 2018 International Tobacco Control (ITC) Japan Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8418. 10.3390/ijerph17228418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karim MA, Talluri R, Chido-Amajuoyi OG, Shete S. Awareness of heated tobacco products among US Adults - Health information national trends survey, 2020. Substance Abuse. 2022;43(1):1023–1034. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2022.2060440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller CR, Sutanto E, Smith DM, et al. Awareness, trial and use of heated tobacco products among adult cigarette smokers and e-cigarette users: findings from the 2018 ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey. Tobacco Control. 2022;31(1):11. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hori A, Tabuchi T, Kunugita N. Rapid increase in heated tobacco product (HTP) use from 2015 to 2019: from the Japan ‘Society and New Tobacco’ Internet Survey (JASTIS). Tobacco Control. 2021;30(4):474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg CJ, Abroms LC, Levine H, et al. IQOS marketing in the US: the need to study the impact of FDA modified exposure authorization, marketing distribution channels, and potential targeting of consumers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):10551. 10.3390/ijerph181910551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillip Morris International. Responsible marketing practices at PMI. 2019. https://www.pmi.com/resources/docs/default-source/default-document-library/responsible-marketing-practices-at-pmi.pdf?sfvrsn=496446b4_4 Accessed 04/06/2022

- 9.Rosen L, Kislev S, Bar-Zeev Y, Levine H. Historic tobacco legislation in Israel: a moment to celebrate. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research. 2020;9(1):22. 10.1186/s13584-020-00384-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bar-Zeev Y, Berg CJ, Kislev S, et al. Tobacco legislation reform and industry response in Israel. Tobacco Control. 2021;30(e1):e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fennis BM, Stroebe W. The psychology of advertising. 3rd edition. Taylor and Francis; 2020. doi: 10.4324/9781315681030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keller KL. Building strong brands in a modern marketing communications environment. Journal of Marketing Communications. 2009;15(2–3):139–155. doi: 10.1080/13527260902757530 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J, Liao X, Huang W, Liao X. Market segmentation: a multiple criteria approach combining preference analysis and segmentation decision. Omega. 2019;83:1–13. 10.1016/j.omega.2018.01.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berg CJ, Haardörfer R, Getachew B, et al. Fighting fire with fire: using industry market research to identify young adults at risk for alternative tobacco product and other substance use. Social Marketing Quarterly. 2017;23(4):302–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lotenberg L, Schechter C, J. S. The SAGE handbook of social marketing. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iyer G, Soberman D, Villas-Boas JM. The targeting of advertising. Marketing Science. 2005;24(3):461–476. [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Silva J, O’Gara E, Villaluz NT. Tobacco industry misappropriation of American Indian culture and traditional tobacco. Tobacco Control 2018;27(e1):e57–e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ranney L, Baker H, Jefferson D, Goldstein A. Identifying outcomes and gaps impacting tobacco control and prevention in African American Communities,. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice. 2016;9(4). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosario C, Harris KE. Tobacco advertisements: what messages are they sending in African American communities? Health Promotion Practice. 2020;21(1, Suppl):54S–60S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warner KE. Tobacco industry response to public health concern: a content analysis of cigarette ads. Health Education Quarterly. 1985;12(1):115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Israel Minstry of Health. Minister of Health Report on Smoking in Israel 2020. May 2021. https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/reports/smoking-2020/he/files_publications_smoking_prevention_smoking_2020.pdf. Accessed 04/06/2022

- 22.Connolly GN, Alpert HR. Has the tobacco industry evaded the FDA ban on ‘light’ cigarette descriptors? Tobacco Control. 2014;23(2):140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.IFAT group. www.ifat.com. Accessed 27/07/2022

- 24.Haardörfer R, Cahn Z, Lewis M, et al. The advertising strategies of early E-cigarette brand leaders in the United States. Tobacco Regulatory Science. 2017;3(2):222–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banerjee S, Shuk E, Greene K, Ostroff J. Content analysis of trends in print magazine tobacco advertisements. Tobacco Regulatory Science. 2015;1(2):103–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grana RA, Ling PM. ‘Smoking revolution’: a content analysis of electronic cigarette retail websites. American Journal of Preventive Medecine. 2014;46(4):395–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. Third Edition.The Free Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berg CJ, Romm KF, Bar-Zeev Y, et al. IQOS marketing strategies in the USA before and after US FDA modified risk tobacco product authorisation. Tobacco Control 2021. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alpert HR, Carpenter D, Connolly GN. Tobacco industry response to a ban on lights descriptors on cigarette packaging and population outcomes. Tobacco Control 2018;27(4):390–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown J, DeAtley T, Welding K, et al. Tobacco industry response to menthol cigarette bans in Alberta and Nova Scotia, Canada. Tobacco Control. 2017;26(e1):e71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bar-Zeev Y, Berg CJ, Khayat A, et al. IQOS marketing strategies at point-of-sales: a cross-sectional survey with retailers. Tobacco Control. 2022. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-057083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bar-Zeev Y, Berg CJ, Abroms LC, et al. Assessment of IQOS marketing strategies at points-of-sale in israel at a time of regulatory transition. Nicotine Tobacco Research. 2022;24(1):100–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.News Srugim. A blow to cigarette companies: they will not be able to publish in newspapers.(link). 2022. Accessed 27/07/2022. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knesset (Israeli Parliament). Advertisment ban and marketing restrictions for smoking and tobacco products, 1983. -correction #8. 01/06/2022. https://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/Legislation/Laws/Pages/LawBill.aspx?t=LawReshumot&lawitemid=2157495. Accessed 27/07/2022

- 35.James SA, Heller JG, Hartman CJ, et al. Smokeless tobacco point of sale advertising, placement and promotion: Associations with store and neighborhood characteristics. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021;9. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.668642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Talbot EM, Giovenco DP, Grana R, Hrywna M, Ganz O. Cross-promotion of nicotine pouches by leading cigarette brands. Tobacco Control. 2021:tobaccocontrol-2021–056899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brock B, Schillo BA, Moilanen M. Tobacco industry marketing: an analysis of direct mail coupons and giveaways. Tobacco Control. 2015;24(5):505–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rábová K Analysis of Presumed IQOS Influencer Marketing on Instagram in the Czech Republic in 2018–2019. ADIKTOLOGIE Journal. 2019; 19(1), 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kislev S, Kislev M. Smoking in Israel 2021: the characteristics of smoking among Jewish youth, young adults and adults. Smoke Free Israel Report. (link). 2021. Accessed 29/04/2022 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Savell E, Gilmore AB, Fooks G. How does the tobacco industry attempt to influence marketing regulations? A systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jackler RK, Ramamurthi D, Axelrod A, et al. Global marketing of IQOS the Philip Morris campaign to popularize ‘heat not burn’ tobacco. 2020. SRITA White paper. (http://tobacco.stanford.edu/iqosanalysis) [Google Scholar]

- 42.FDA news release: FDA authorizes marketing of iqos tobacco heating system with ‘reduced exposure’ information. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-authorizes-marketing-iqos-tobacco-heating-system-reduced-exposure-information. Published 2022. Updated July 07, 2020. Accessed 16/06/2022, 2022.

- 43.Yang B, Massey ZB, Popova L. Effects of modified risk tobacco product claims on consumer comprehension and risk perceptions of IQOS. Tobacco Control. 2021:tobaccocontrol-2020–056191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKelvey K, Baiocchi M, Halpern-Felsher B. PMI’s heated tobacco products marketing claims of reduced risk and reduced exposure may entice youth to try and continue using these products. Tobacco Control. 2020;29(e1):e18–e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tobacco Tactics. PMI promotion of IQOS using FDA MRTP order. https://tobaccotactics.org/wiki/pmi-iqos-fda-mrtp-order/. Published 2020. Accessed 16/06/2022.

- 46.Lempert LK, Bialous S, Glantz S. FDA’s reduced exposure marketing order for IQOS: why it is not a reliable global model. Tobacco Control. 2021:tobaccocontrol-2020–056316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.