Abstract

Little has been reported about hardening nor softening indicators in Africa where smoking prevalence is low. We aimed to examine the determinants of hardening in nine African countries. We conducted two separate analyses using data from the most recent Global Adult Tobacco Survey in Botswana, Cameroon, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, Tanzania, and Uganda (total sample of 72,813 respondents): 1) multilevel logistic regression analysis to assess individual and country-level factors associated with hardcore, high dependence, and light smoking.; 2) a Spearman-rank correlation analysis to describe the association between daily smoking and hardcore, high dependence, and light smoking at an ecological level. Age-standardized daily smoking prevalence varied from 37.3% (95 %CI: 34.4, 40.3) (Egypt) to 6.1% (95 %CI: 3.5, 6.3) (Nigeria) among men; and 2.3% (95 %CI: 0.7, 3.9) (Botswana) to 0.3% (95 %CI: 0.2, 0.7) (Senegal) among women. The proportion of hardcore and high-dependence smokers was higher among men whereas for light smokers the proportion was higher among women. At the individual level, higher age and lower education groups had higher odds of being hardcore smokers and having high dependence. Smoke-free home policies showed decreased odds of both being hardcore and highly dependent smokers daily smoking correlated weakly and negatively with hardcore smoking (r = −0.243, 95 %CI: −0.781, 0.502) among men and negatively with high dependence (r = −0.546, 95 %CI: −0.888, 0.185) and positively with light smokers (r = 0.252, 95 %CI: −0.495, 0.785) among women. Hardening determinants varied between the countries in the African region. Wide sex differentials and social inequalities in heavy smoking do exist and should be tackled.

Keywords: Smokers, Hardening hypothesis, Softening, GATS, Africa, Multilevel analysis, Ecological analysis

1. Introduction

Implementation of comprehensive tobacco control policies (World Health Organization, 2003) has resulted in a decline in tobacco use mostly in high-income countries (HICs) (Bilano et al., 2015; Feliu et al., 2019a; Flor et al., 2021). However, as the smoking prevalence declines, it has been suggested that the population of smokers becomes more ‘hardened’ (DiFranza, 1989) since the remaining smokers are more addicted and less able or motivated to quit (Docherty and McNeill, 2012). The ‘hardened smokers’ seem to pose a challenge to further decline in smoking prevalence (Darville and Hahn, 2014) but this hypothesis has been thrown into question in the last years (Fagerstrom and Furberg, 2008).

Studies from HICs have tested the ‘hardening hypothesis’ by examining the changes in the smoking prevalence over time using serial survey data (Azagba, 2015, Bommele et al., 2016, Edwards et al., 2017; Feliu et al., 2019b; Kang et al., 2017, Mathews et al., 2010) with different results and critics against the hardening theory argue that by using different available variables in survey data, researchers have reported different definitions for the term ‘hardcore smoker’ which by itself is misleading, scientifically incorrect, and even stigmatizing (West and Jarvis, 2018). While smoking prevalence in HICs continues to decline through the implementation of comprehensive tobacco control policies (Flor et al., 2021), low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) still have relatively higher smoking prevalence and a less comprehensive and relatively weaker tobacco control environment (West, 2006).

Most African countries, specially Sub-Saharan ones, are still in an early stage of tobacco epidemic (Lopez et al., 1994), though experts project that tobacco consumption in African countries may experience a large increase in the upcoming decade (Bilano et al., 2015). Available data shows that smoking prevalence is still low, particularly among women, in most countries albeit a few exceptions (Sreeramareddy et al., 2014), and has even declined in some countries in the last two decades (Sreeramareddy and Acharya, 2021). However, little evidence is available about the hardcore and light smoking (smokes <5 cigarettes per day) in Africa. Hence, this study aims to estimate prevalence of hardcore smoking and light smoking in nine African countries, and to analyze the determinants of hardcore and light smoking considering both individual and contextual country-level characteristics.

2. Methods

We conducted secondary data analyses of the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) in nine African countries (Botswana, year 2017; Cameroon, year 2013; Egypt, year 2009; Ethiopia, year 2016; Kenya, year 2014; Nigeria, year 2012; Senegal, year 2015; Tanzania, year 2018; and Uganda, year 2013), by performing individual and ecological cross-sectional analyses. The total survey sample was 72,813 individuals. Country-wise sample sizes and overall response rates were Botswana, 4,643, 80.0%; Cameroon, 5,271, 94.1%; Egypt, 20,924 97.3%; Ethiopia 10,150, 93.4%; Kenya, 4,408, 87.1%; Nigeria, 9,765, 89.1%; Senegal, 4,416, 98.5%; Tanzania, 4,797 91.7% %; and Uganda, 8,508, 86.6 %.

2.1. Data source

We used GATS data available publicly at https://nccd.cdc.gov/gtssdata/Ancillary/DataReports. Briefly, GATS is a series of nationally representative, cross-sectional household surveys conducted for global tobacco surveillance systems to monitor tobacco use patterns adults. GATS collects information about tobacco use behaviors among civilian, non-institutionalized persons who are aged ≥ 15 years using a standardized core questionnaire to enable cross-country comparisons. The residents of all regions are included in the sampling frame. The survey sample is selected by a stratified multi-stage probability sampling technique. In each selected geographic unit, the households are randomly selected. One adult aged ≥ 18 years responds to the household questionnaire and listed all household members aged ≥ 15 years. All adults ≥ 15 and older are rostered but only one household member was randomly selected and interviewed with a handheld device. The implementing agencies n each country adapted the core questionnaire to suit the country context and types of tobacco products consumed. More details about survey questionnaire, methods are reported elsewhere (Palipudi et al., 2016).

2.2. Outcome variables

The respondents were asked “Do you currently smoke tobacco on a daily basis, less than daily, or not at all?” Those who replied as ‘daily’ were defined as daily current smokers. We used the question “On average, how many of the following products do you currently smoke each day?” to compute cigarettes per day (CPD). The total number of CPD was obtained by adding up the reported numbers for each type of smoking tobacco products. Light smokers were those who smoked less than five CPD (Feliu et al., 2019b). Current smokers were also asked “How soon after you wake up do you usually have your first smoke?”, “During the past 12 months, have you tried to stop smoking?” and “Which of the following best describes your thinking about quitting smoking?”.

Hardcore smokers were defined as: 1) a current daily smoker; 2) who smokes 10 or more CPD; 3) who reported having his/her first cigarette within 30 min after waking up; 4) who has not made any quit attempts during 12 months prior to the date surveyed; and 5) who has no intention to quit smoking at all or during the next 12 months (Sreeramareddy, 2021, Sreeramareddy et al., 2018).

As there is no universally accepted definition of hardcore smokers, we have also used nicotine high dependence as a main dependent variable. Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) is dependencies sum of responses to, two questions (Chabrol et al., 2005, Heatherton et al., 1989): time to first cigarette in the morning (3, 2, 1, or 0 points) and number of cigarettes per day smoked (0, 1, 2, or 3 points). Based HSI score nicotine dependence was categorized as low (0–1), medium (2–4) and high (5–6).

2.3. Independent variables

We also used information about sex (men, women), age (<25, 25–35, 36–45, >45 years old), occupation (government employee, non-government employee, self-employed, student or housewife, and unemployed or retired), education level (no education, primary school, secondary school, high school, college, or university), smoking rules at home (never allowed, not allowed with exceptions, no rules), the Household Wealth Index (HWI) and a knowledge score about health effects of cigarette smoking. To compute the HWI a list of household assets was gathered asking “please tell me whether this household or any person who lives in the household has the following items?”. The scores are divided into quintiles from 1 [poorest] to 5 [richest] based on the principal component analyses of household assets (Vyas and Kumaranayake, 2006). The knowledge score about health effects of cigarette smoking was computed as the sum of scores given to four questions about health effects of cigarette smoking i.e., “based on what you know or believe, does smoking tobacco causes, 1) serious illness, 2) stroke, 3) heart attack, and 4) lung cancer”. The response ‘yes’ was scored ‘1’ and ‘no’ or ‘don’t know’ as ‘0’.

2.4. Statistical analyses

We calculated weighted and age-standardized prevalence estimates (and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals [CI]) of daily smoking and the proportions of hardcore, high dependence (HSI score 5–6), and light smoking (among daily smokers) for each country by means of the direct method of standardization using the World Health Organization (WHO) world standard population (https://www.who.int/healthinfo/paper31.pdf). For prevalence rates (and 95% CI estimates) derived from low frequencies (as observed for women) we used the Wilson ‘score’ method using asymptotic variance (Newcombe, 1998). According to Lopez’s revised tobacco epidemic model most African nations are in stage 3 (Thun et al., 2012). As there is a very wide gap between smoking rates between men (higher) and women (lower), we conducted sex-specific analyses.

We conducted a logistic regression analysis with the individual data to assess the association (odds ratio [OR] and 95 %CI) of being a hardcore or a light smoker (dependent variable) with the country, age, occupation, education level, smoking rules at home, the HWI and the knowledge score about health effects of cigarette smoking (independent variables). In a separate model, we used country as independent variable. We also fitted multilevel logistic regression models to assess the influence of some contextual factors (e.g.: Gross Domestic Product). We used Akaike and Bayesian information criteria to determine the optimal specification of the logistic regression model. All analysis were stratified by sex.

Finally, we conducted an ecological analysis with the country as the unit of analysis. We assessed the association of daily smoking prevalence with the proportions of hardcore, high dependence, or light smokers among of daily smokers. We conducted an analysis in the total population, and by sex, by means of scatter plots and Spearman rank correlation coefficients (rsp) with the corresponding 95 %CI. All the statistical analyses were performed on Stata MP 11.

3. Results

Sex-wise distribution was nearly the same [male: 34,321 (47.1%) and female: 38,492 (52.9%)]. Mean age was 36.8 years (SD = 15.8). The distribution of survey sample by raw and weighted numbers (%) are shown in Table S1. About two thirds of the survey participants were aged between 15 and 35 years. The main occupation during the previous year was non-governmental employees (29%), self-employed (26%) and student/housewife (23%). About a quarter had not received any formal education and 56% had received primary/secondary education only. Distribution of survey respondents by HWI was nearly equitable and in 60% of the household smoking inside was ‘not allowed’.

Age-standardized prevalence estimates of daily smoking varied between the nine countries, from among men 37.3% (95 % CI: 34.4, 40.3) in Egypt to 6.1% (95 % CI: 3.5, 6.3) in Nigeria; and 2.3% (95 % CI: 0.7, 3.9) in Botswana to 0.3% (95 % CI: −0.1, 0.8) in Senegal among women, displaying very wide differences in daily smoking by sex. Moreover, the proportion of those daily smokers who were hardcore smokers ranged from 22.3% (95% CI: 5.8, 38.8) in Ethiopia to 7.4% (95 % CI: 5.1, 10.4) in Botswana among men; and 14.7% (95% CI: 4.7, 44.8) in Nigeria to 1.2% (95% CI: 1.2, 43.5) in Senegal among women. The proportion of hardcore smokers among daily smokers was relatively lesser among women than men except in Nigeria (men: 11.9% vs. women: 14.7%). The highest proportion of high dependence among men daily smokers was in Ethiopia (24.3%; 95 % CI: 6.7, 41.8), and among women in Nigeria (30.9; 95 % CI: 13.8, 60.9). Except Nigeria (men: 11.9 % vs. women: 30.9 %) and Senegal (men: 11.0% vs. women: 20.3%) the proportion of high dependence was lower among women than men. Finally, the proportion of light smokers ranged from 45.5% (95 % CI: 25.5, 65.4) in Tanzania to 15.8% (95 % CI: 11.8, 19.8) in Egypt among men; and 68.8% (95 % CI: 26.4, 79.8) in Uganda to 25.2% (95 % CI: 2.0, 48.4) in Ethiopia among women. The proportion of light smokers among daily smokers was significantly higher among women in Cameroon, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda, while it was nearly same in the other countries (Table 1).

Table 1.

Weighted and age-standardized prevalence estimates and 95% confidence interval (CI) of daily smoking, hardcore smoking, high dependence smoking, and light smoking among current smokers in 9 African countries by sex.

| Men | Women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Daily smoking |

Hardcore smoking |

High dependence |

Light smoking |

Daily smoking |

Hardcore smoking |

High dependence |

Light smoking |

|

| Weighted estimates (% and 95 %CI) | ||||||||

| Cameroon | 9.1 (7.5, 10.7) | 17.3 (10.8, 23.7) | 11.2 (5.3, 17.2) | 26.9 (20.9, 33.0) | 0.5 (0.2, 0.7) | 21.8 (6.2, 41.0) | 6.8 (10.4, 27.0) | 67.5 (40.9, 94.0) |

| Egypt | 35.8 (34.6, 37.1) | 17.8 (16.1, 19.6) | 10.1 (8.9, 11.3) | 17.1 (15.4, 18.9) | 0.5 (0.2, 0.7) | 10.1 (0.5, 19.7) | 5.7 (4.1, 20.0) | 61.1 (46.5, 75.8) |

| Ethiopia | 5.2 (3.8, 6.7) | 18.3 (11.3, 25.3) | 26.5 (17.2, 5.9) | 25.3 (14.2, 36.5) | 1.1 (0.0, 2.3) | 1.9 (7.9, 19.9) | 5.1 (12.0, 25.0) | 26.2 (19.3, 33.1) |

| Kenya | 11.6 (9.0, 14.2) | 17.3 (10.5, 24.2) | 17.2 (9.6, 24.7) | 27.6 (18.9, 36.3) | 0.6 (0.1, 1.1) | 2.1 (0.9, 23.0) | 1.6 (2.8, 30.0) | 55.6 (15.2, 96.1) |

| Nigeria | 5.6 (4.6, 6.5) | 14.6 (7.6, 21.5) | 9.8 (3.9, 15.6) | 30.4 (23.5, 37.3) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.5) | 15.1 (4.7, 44.8) | 29.0 (2.1, 55.8) | 27.4 (1.0, 53.7) |

| Senegal | 9.7 (8.1, 11.4) | 8.9 (4.3, 13.4) | 9.7 (5.8, 13.6) | 31.1 (23.7, 38.4) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.6) | 2.4 (2.0, 44.0) | 14.0 (2.0, 44.0) | 45.4 (4.1, 86.7) |

| Uganda | 8.7 (7.4, 9.9) | 11.9 (7.4, 16.4) | 8.5 (4.7, 12.3) | 44.6 (38.0, 51.2) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.7) | 4.7 (1.5, 11.7) | 1.1 (2.5, 7.6) | 70.7 (56.7, 84.8) |

| Botswana | 18.2 (15.8, 20.6) | 6.8 (3.3, 10.4) | 14.7 (9.2, 20.2) | 37.3 (30.5, 44.2) | 2.2 (1.5, 2.9) | 9.8 (1.3, 18.3) | 8.7 (0.3, 7.6) | 56.4 (40.5, 72.3) |

| Tanzania | 9.9 (8.3, 11.5) | 10.3 (5.3, 15.2) | 8.6 (3.9, 13.3) | 39.8 (31.4, 48.3) | 0.9 (0.4, 1.4) | 3.7 (0.8, 21.0) | 6.1 (2.4, 26.8) | 59.5 (36.4, 82.7 |

| Age-standardized estimates (% and 95 %CI) | ||||||||

| Cameroon | 10.3 (6.5, 14.0) | 19.1 (2.9, 35.3) | 9.3 (5.5, 12) | 29.4 (12.9, 46.0) | 0.6 (0.4, 1.1) | 16.0 (6.2, 41.0) | 5.5 (1.1, 26.9) | 36.9 (2.4, 49.3) |

| Egypt | 37.3 (34.4, 40.3) | 17.6 (13.7, 21.4) | 10.0 (7.1, 12.9) | 15.8 (11.8, 19.8) | 0.6 (0.1, 1.0) | 11.6 (4.1, 20.3) | 8.7 (3.0, 18.2) | 61.9 (28.4, 95.4) |

| Ethiopia | 6.3 (2.9, 9.6) | 22.3 (5.8, 38.8) | 24.3 (6.7, 41.8) | 25.6 (5.6, 45.6) | 1.3 (0.0, 2.6) | 4.0 (0.0, 19.9) | 5.3 (1.2, 25.9) | 25.2 (2.0, 48.4) |

| Kenya | 14.1 (8.1, 20.1) | 13.7 (3.0, 24.3) | 15.1 (1.3, 28.9) | 23.9 (7.1, 40.8) | 0.8 (1.8, 2.6) | 2.73 (0.9, 23.6) | 2.2 (0.2, 30) | 73.5 (12.3, 53.7) |

| Nigeria | 6.1 (3.5, 8.7) | 11.9 (0.9, 23.0) | 10.7 (5.9, 12.0) | 27.4 (10.6, 44.3) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.5) | 14.7 (4.7, 44.8) | 30.9 (13.8, 60.9) | 27.1 (13.8, 60.1) |

| Senegal | 10.5 (6.6, 14.3) | 11.0 (5.8, 13.1) | 10.7 (7.6, 15.6) | 28.8 (9.1, 48.6) | 0.3 (0.2, 0.7) | 1.2 (1.2, 43.5) | 20.3 (2.0, 43.5) | 33.8 (13.860.9) |

| Uganda | 10.8 (7.3, 14.4) | 12.2 (1.2, 23.2) | 11.7 (6.0, 11.6) | 45.1 (27.9, 62.3) | 1.9 (0.7, 3.1) | 2.5 1.5,11.7) | 0.5 (0.3, 7.6) | 68.8 (26.4, 79.8) |

| Botswana | 18.5 (12.7, 24.3) | 7.4 (5.1, 10.4) | 16.9 (2.2, 31.6) | 34.4 (17.6, 51.2) | 2.3 (0.7, 3.9) | 9.2 (5, 19.5) | 11.0 (4.6, 22.6) | 28.8 (47.6 70.2) |

| Tanzania | 11.6 (7.8, 15.4) | 7.6 (0.8, 14.4) | 6.5 (6.9, 14.5) | 45.5 (25.5, 65.4) | 1.3 (0.7, 1.5) | 2.8 (1.8, 7.4) | 6.9 (2.8, 30.1) | 47.0 (3.0, 59.6) |

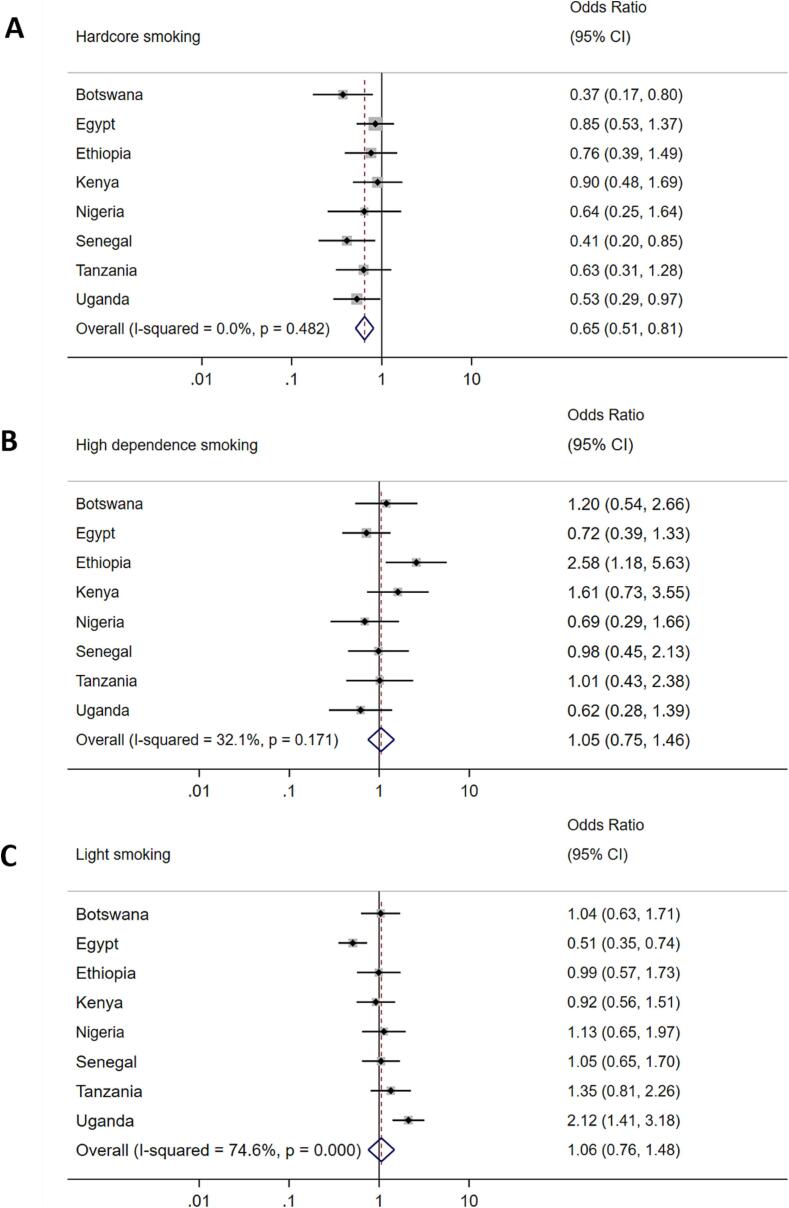

As shown in Fig. 1, with Cameroon as the reference country, the odds ratio of hardcore smoking among men were lower in Botswana (OR = 0.37, 95 % CI: 0.17, 0.80) and Senegal (OR = 0.41, 95 % CI: 0.20, 0.85). The odds ratios of high dependence smoking (HSI 5–6) were not significantly different across countries, except for Ethiopia that showed the highest odds ratio of high dependence smoking (OR = 2.58, 95 % CI: 1.18, 5.63). Finally, the odds ratio of light smoking was lower in Egypt (OR = 0.51, 95 % CI: 0.35, 0.74) and higher in Uganda (OR = 2.12, 95 % CI: 1.41, 3.18) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of being a hardcore (panel A), a high dependent (panel B), a light smoker (panel C) or a light smoker by country.* Footnote: *OR and 95%CI derived from logistic regression models adjusted for age, occupation, education level, smoking rules at home, knowledge score about health effects of cigarette smoking.

In the pooled sample the proportions of hardcore, high dependence and light smokers showed some differences by sex (Table S1). The proportions of hardcore, high dependence and light smokers by age, occupation, and HWI were similar. However, the proportions of hardcore, high dependence, and light smoking were higher in poorest, poorer, and middle wealth groups compared to richer and richest ones. More than half of the hardcore, high dependence, and light smokers were from households where smoking was allowed (Table S1).

Factors associated with hardcore smoker, high dependence smoker, and light smoker among men are shown in Table 2. Among men, hardcore smoking was associated with higher age, non-governmental employment, primary education, and smoking rules at home. Men aged 36–45 years and men educated up to primary school were 1.6 times more likely (aOR: 1.58; 95% CI: 1.11, 2.24) and 1.4 times (aOR: 1.41; 95 % CI: 1.08, 2.01) of being a hardcore smoker compared to those aged 15–25 years and uneducated, respectively. In contrast, men who were nongovernmental employees were 0.7 times less likely of being hardcore smoker (aOR: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.52, 0.92) compared to men who were government employees. High-dependence smoking was associated with being a student, having primary education, and smoking rules at home. Being a student was associated with being a high dependent smoker (aOR: 2.05; 95% CI: 1.09, 3.86) compared to government employees; and those with primary school education was associated with being a high-dependent smoker (aOR: 1.84; 95% CI: 1.31, 2.59). Finally, light smoking was associated with being s a non-government employee student and having an education up to college/university. Non-governmental employees and students had about 1.6 times and 1.8 times higher odds of being light smoker (aOR: 1.59; 95% CI: 1.21, 2.01 and aOR: 1.78; 95% CI: 1.06, 2.98, respectively) than those working in services. However, men educated up to college/university had 0.58 times lower odds of being light smoker (aOR: 0.58; 95% CI: 0.42, 0.82) than uneducated men. Notably, men from houses where smoking was ‘never allowed’ less likely of being hardcore (aOR: 0.42; 95% CI: 0.28, 0.63) and high dependent smokers (aOR: 0.61; 95% CI: 0.43, 0.88), respectively, compared to men from houses where smoking was ‘allowed’. Similarly, men in houses where smoking was ‘never allowed’ were more likely light smokers (aOR: 2.22; 95% CI: 1.69, 2.91) compared to their counterparts from houses where smoking was allowed. Among women (Supplementary Table 2), None of the factors were associated with hardcore smoking. Occupation i.e. being self-employed (aOR: 28.2; 95 % CI: 2.91, 74.00) and housewife (aOR: 8.00; 95 % CI: 1.17, 54.89 for housewives), education (aOR: 0.01; 95 % CI: 0.00, 0.20 for high school), smoking rules at home (aOR; 3.85; 95 % CI: 1.02, 14.50 for never allowed), HWI (aOR; 0.04; 95 % CI: 0.01, 0.29 for the richest) and knowledge score (aOR; 1.76; 95 % CI: 1.11, 2.80) were associated with high dependence. Occupation i.e., being self-employed (aOR; 0.09; 95 % CI: 0.02, 0.39) and smoking rules at home (aOR; 0.27; 95 % CI: 0.09, 0.81 for no rules) were associated with light smoking.

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of being a hardcore smoker, a high dependent smoker, and a light smoker among men in 9 African countries.

| Hardcore smoking (N = 6546) |

High dependence smoking (N = 6526) |

Light smoking (N = 6546) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| aOR* (95% CI) | aOR* (95% CI) | aOR* (95% CI) | |

| Age group (years) | |||

| <25 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–35 | 1.20 (0.83, 1.73) | 1.24 (0.79, 1.93) | 1.28 (0.84, 1.95) |

| 36–45 | 1.58 (1.11, 2.24) | 1.68 (1.09, 2.60) | 1.31 (0.82, 2.08) |

| >45 | 1.41 (0.98, 2.02) | 1.09 (0.69, 1.74) | 1.68 (1.01, 2.79) |

| Occupation | |||

| Government employee | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Non-government employee | 0.69 (0.52, 0.92) | 1.00 (0.74, 1.34) | 1.59 (1.21, 2.09) |

| Self-employed | 1.00 (0.52, 1.94) | 1.56 (0.80, 3.07) | 1.57 (0.99, 2.48) |

| Student | 1.21 (0.66, 2.22) | 2.05 (1.09, 3.86) | 1.78 (1.06, 2.98) |

| Unemployed or retired | 0.82 (0.57, 1.19) | 1.25 (0.85, 1.85) | 1.00 (0.72, 1.39) |

| Education | |||

| No education | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Primary school | 1.47 (1.08, 2.01) | 1.84 (1.31, 2.59) | 0.88 (0.67, 1.15) |

| Secondary school | 1.08 (0.76, 1.52) | 0.90 (0.60, 1.34) | 0.74 (0.53, 1.04) |

| High school | 1.17 (0.72, 1.89) | 1.26 (0.77, 2.07) | 0.66 (0.27, 1.61) |

| College or university | 1.17 (0.86, 1.60) | 1.25 (0.86, 1.84) | 0.58 (0.42, 0.82) |

| Smoking rules at home | |||

| Allowed | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Not allowed with exceptions | 0.88 (0.61, 1.25) | 0.76 (0.52, 1.12) | 1.37 (1.00, 1.86) |

| Never allowed | 0.42 (0.28, 0.63) | 0.61 (0.43, 0.88) | 2.22 (1.69, 2.91) |

| No rules | 0.86 (0.56, 1.32) | 1.33 (0.82, 2.16) | 1.25 (0.86, 1.81) |

| Household wealth index | |||

| Poorest | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Poorer | 1.07 (0.81, 1.41) | 1.10 (0.77, 1.58) | 0.80 (0.61, 1.04) |

| Middle | 0.91 (0.65, 1.26) | 0.96 (0.67, 1.38) | 1.02 (0.74, 1.40) |

| Richer | 1.18 (0.74, 1.88) | 0.96 (0.60, 1.53) | 0.78 (0.53, 1.15) |

| Richest | 0.84 (0.58, 1.20) | 1.05 (0.67, 1.64) | 1.01 (0.72, 1.42) |

| Knowledge score (cont.) | 1.04 (0.92, 1.17) | 1.04 (0.89, 1.21) | 1.0 (0.90, 1.10) |

*Adjusted odds ratios derived from multiple logistic regression models adjusted for all the variables in the table and country.

At an ecological level, we explored the association between the prevalence of hardcore, high dependence and light smoking as a proportion of daily smokers and the smoking prevalence in each country. Daily smoking among both men (r = −0.243, 95% CI: −0.781 to 0.502) and women (r = -0.294, 95% CI: −0.802 to 0.460) correlated weakly and negatively with hardcore smoking suggesting that a low smoking prevalence would be associated with a high proportion of hardcore smokers. Among men, no association was found between daily smoking and proportion of high dependence nor light smoking. However, among women daily smoking was negatively correlated with high dependence (r = −0.546, 95% CI: −0.888 to 0.185) and positively with light smoking (r = 0.252, 95% CI: −0.495 to 0.785) suggesting that a low smoking prevalence would be associated with a low proportion of high dependent smokers and a high proportion of light smoker.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main results

Nationally representative survey data from nine African countries showed differences in daily smoking rates across countries and wide sex-differences within each country. Sex-specific analyses revealed that among daily smokers, proportions of hardcore and high dependence smokers were higher among men while light smoker was higher among women in all countries. Men aged 36 to 45 years old and educated up to primary school had higher odds of being hardcore and high dependence smokers while men aged > 45 years had higher odds of being light smoker. Men living in ‘smoke-free’ homes had lower odds of hardcore and high dependence smoking, but higher odds of being a light smoker. Finally, men who were self-employed or into business had lower odds of being hardcore smoker but higher odds of being light smoker. No association was found between daily smoking prevalence and any of the hardening indicators at the ecological level.

4.2. Interpretation of the results

Daily smoking prevalence among women in Africa was < 5%. These results were in line with a previous study reporting smoking prevalence in 30 Sub-Saharan African countries (Sreeramareddy et al., 2014). Consequently, because of low prevalence in women, the sample size of hardcore, high dependence and light smokers was even lower and, hence, we decided to focus on individual factors associated with hardening and softening among men to ensure statistical power.

At the individual level, we found that hardcore smoking was associated with a higher age (36–45 years), manual occupations, and lower education as observed in previous studies in LMICs (Yin et al., 2019) and from European countries (Feliu et al., 2019b). Our findings indicate that both hardcore and light smoking are associated both to individual socioeconomic and demographic characteristics also in Africa. The observed social gradient in heavy smoking highlights that the socioeconomic inequalities and the increased burden of smoking-related diseases among people in low socioeconomic groups (Clare et al., 2014). Hence, hardening is a burden of the poorest individuals of societies even in already deprived populations.

In our ecological analyses, daily smoking among both men and women correlated weakly and negatively with hardcore smoking suggesting that countries with a low smoking prevalence would have a high proportion of hardcore smoker among daily smokers. Conversely, among women daily smoking correlated weakly and positively with light smoker which is suggestive that remaining female smokers continue to smoke but reduced cigarettes per day (Fernandez et al., 2015). Daily smoking and high dependence smoker, however, were not correlated suggesting that daily smoking rates is not associated with nicotine dependence. Studies from European HICs with high daily smoking rates that tested the “hardening hypothesis” with ecological analyses have shown conflicting results for correlation of daily smoking rates with smoking dependence (Feliu et al., 2019b; Fernandez et al., 2015). However, GATS report of 10 LMICs has shown that change between two surveys in daily smoking correlated moderately and positively with proportion of hardcore smoker (Sreeramareddy, 2021). This shows that empirical evidence about “hardening hypothesis” is conflicting in LMICs even where the prevalence of smoking is lower than HICs for which literature about hardcore smoking is available.

The lack of evidence of “hardening” in HICs, where tobacco use is declining and tobacco control policies are more comprehensive, and the limited evidence of ‘hardening’ in LMICs, where tobacco control policies are still scarce, has shifted the focus towards exploring the “softening hypothesis” (Edwards, 2019). A softening of the smoking population would suggest that tobacco control policies (e.g. smoke-free policies, tobacco taxation and advertising bans) are effective not only in motivating light smokers to quit, but also in influencing hardcore and high dependent smokers to quit smoking or at least to reduce their daily cigarette consumption (Feliu et al., 2019b). On the contrary, in LMICs, where tobacco control policies are weak hardening could be occurring as shown by our results These results suggests moving beyond tobacco control towards a tobacco-free future (Beaglehole et al., 2015). Smokers in HICs nowadays belong to more deprived population groups than in the past (Augustson et al., 2008; Feliu et al., 2019b). While research in this direction is underway among the disadvantaged groups of HICs (Edwards et al., 2017, Kulik and Glantz, 2019), some research from LMICs report that lower education, and income are the indicators of having higher odds of being hardcore smoker (Kien et al., 2017, Yin et al., 2019), but further longitudinal research is needed to be able to assess not only hardcore and light smoking determinants in African countries as in our study, but also to confirm or reject the hardening hypothesis.

Regardless of the evidence of “hardening” or the lack of thereof, the focus should be to emphasize on the individuals who continue to smoke and those who find it hard to quit, to further reduce smoking and achieve the tobacco endgame, which suggests moving beyond tobacco control towards a tobacco-free future wherein commercial tobacco products would be phased out or their use and availability significantly restricted (McDaniel et al., 2016). To further reduce smoking prevalence and attain smoke-free generation a comprehensive approach is needed to prevent uptake of smoking especially the youth.

Moreover, to understand indicators of heavy smoking, we did not only assess the individual level, but also country contextual factors (Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and MPOWER score (Ngo et al., 2017)) associated with hardcore, high dependence and light smoking by conducting a multilevel logistic regression analysis to account for clustering of observations within countries. However, due to very little variation in the contextual factors across the nine countries under study and the small statistical power, we did not further test these factors as second level of analysis.

4.3. Limitations and strengths

Among the limitations, we lack serial survey data needed to test the “hardening hypotheses” as was proposed in HICs (Azagba, 2015, Bommele et al., 2016; Brennan et al., 2019; Fagerstrom and Furberg, 2008). The association reported cannot be interpreted as causal, given the cross-sectional design of the survey. Self-reported tobacco use behaviors are likely to be affected by reporting bias; however, self-reports on smoking status have acceptable validity (Gorber et al., 2009). The survey was conducted across different years in the nine countries, and it could have affected our pooled data analyses since tobacco control measures and tobacco use rates are dynamic. Hardcore smoker is variedly defined according to available constructs with our data whereas other studies have used other indicators (Buchanan et al., 2020). However, we have included different measures of heavy smoking to have a broader idea of what it is the reality in the region.

Our study presents strengths worth to mention. We used data from the GATS, an international survey designed specifically for tobacco use surveillance in nationally representative samples, to provide robust estimates of tobacco use. The GATS questionnaire is intended for cross-national comparisons (Sreeramareddy et al., 2018, Yin et al., 2019). The surveys follow a standard and strict protocol reassuring against potential selection and information biases and thus preventing systematic errors due to survey methodology between countries. Moreover, the rich information gathered in the GATS has allowed us to test the association between our outcomes and several independent factors, and to test for variability across countries. Our study is the first to report hardening, high dependence, and light smoking prevalence in nine African countries and to describe hardening and light smoking determinants from both an ecological and individual perspective.

5. Conclusions

Our study showed that hardening determinants among daily smokers varied widely between the nine African countries and had very wide sex-differentials. Social inequalities observed in heavy smoking highlight that population-based tobacco control policies are not enough to achieve the tobacco endgame. Understanding hardening determinants in African population, where smoking prevalence are still low but is expected to increase soon, offers the opportunity to tailor tobacco control policies to more hardened groups to ensure that no one is left behind, while moving beyond tobacco control towards a tobacco-free future (Husain et al., 2016). Serial population-based survey data are needed to monitor daily smoking as well as for test of hardening in African countries.

Contributors CTS, EF and AF conceived the manuscript aim and analysis plan. CTS obtained the GATS data files and analyzed the data with AF supervision. CTS wrote the first draft of the manuscript, to which EF and AF contributed. All the authors contributed to manuscript preparation and approved its final version prior to submission. EF is the guarantor.

The Tobacco Control Research Group at ICO-IDIBELL (AF and EF) is partly supported by the Ministry of Universities and Research, Government of Catalonia (2021SGR00) and thank CERCA Programme, Generalitat de Catalunya for the institutional support to IDIBELL.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Ethics approval Since secondary data was used, ethical approval was not needed.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102226.

Contributor Information

Chandrashekhar T Sreeramareddy, Email: chandrashekharats@yahoo.com.

Esteve Fernandez, Email: efernandez@iconcologia.net.

Ariadna Feliu, Email: af.josa@gmail.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

The data used to prepare this report are publicly available at the website of Centre for Disease Control, Atlanta. The Stata code used for the analyses can be provided up on reasonable request.

References

- Augustson E.M., Barzani D., Finney Rutten L.J., Marcus S. Gender differences among hardcore smokers: an analysis of the tobacco use supplement of the current population survey. J. Womens Health. 2008;17(7):1167–1173. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azagba S. Hardcore smoking among continuing smokers in Canada 2004–2012. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaglehole R., Bonita R., Yach D., Mackay J., Reddy K.S. A tobacco-free world: a call to action to phase out the sale of tobacco products by 2040. The Lancet. 2015;385(9972):1011–1018. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilano V., Gilmour S., Moffiet T., d'Espaignet E.T., Stevens G.A., Commar A., Tuyl F., Hudson I., Shibuya K. Global trends and projections for tobacco use, 1990–2025: an analysis of smoking indicators from the WHO Comprehensive Information Systems for Tobacco Control. The Lancet. 2015;385(9972):966–976. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60264-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommele J., Nagelhout G.E., Kleinjan M., Schoenmakers T.M., Willemsen M.C., van de Mheen D. Prevalence of hardcore smoking in the Netherlands between 2001 and 2012: a test of the hardening hypothesis. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3434-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan T., Magee C.A., V. See H., Kelly P.J. Tobacco harm reduction: are smokers becoming more hardcore? J. Public Health Policy. 2020;41(3):286–302. doi: 10.1057/s41271-020-00226-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabrol H., Niezborala M., Chastan E., de Leon J. Comparison of the Heavy Smoking Index and of the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence in a sample of 749 cigarette smokers. Addict. Behav. 2005;30(7):1474–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare P., Bradford D., Courtney R.J., Martire K., Mattick R.P. The relationship between socioeconomic status and ‘hardcore’smoking over time–greater accumulation of hardened smokers in low-SES than high-SES smokers. Tob. Control. 2014;23(e2):e133–e138. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darville A., Hahn E.J. Hardcore smokers: what do we know? Addict. Behav. 2014;39(12):1706–1712. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza J.R. Hard-core smokers. JAMA. 1989;261:2634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docherty G., McNeill A. The hardening hypothesis: does it matter? Tob. Control. 2012;21:267–268. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R., Tu D., Newcombe R., Holland K., Walton D. Achieving the tobacco endgame: evidence on the hardening hypothesis from repeated cross-sectional studies in New Zealand 2008–2014. Tob. Control. 2017;26:399–405. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom K., Furberg H. A comparison of the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence and smoking prevalence across countries. Addiction. 2008;103:841–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, R., 2019. Hardening is dead, long live softening; time to focus on reducing disparities in smoking. Tob Control. 2019:tobaccocontrol-2019-055067. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brennan, E., Greenhalgh, E.M., Durkin, S.J., Scollo, M.M., Hayes, L., Wakefield, M.A., 2019. Hardening or softening? An observational study of changes to the prevalence of hardening indicators in Victoria, Australia, 2001-2016. Tob Control.:tobaccocontrol-2019-054937. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Feliu, A., Filippidis, F.T., Joossens, L., Fong, G.T., Vardavas, C.I., Baena, A., Castellano, Y., Martinez, C., Fernandez, E., 2019b. Impact of tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence and quit ratios in 27 European Union countries from 2006 to 2014. Tob. Control 28, 101–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Feliu A., Fernandez E., Martinez C., Filippidis F.T. Are smokers “hardening‾ or rather “softening‾? An ecological and multilevel analysis across 28 European Union countries. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(3):1900596. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00596-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez E., Lugo A., Clancy L., Matsuo K., La Vecchia C., Gallus S. Smoking dependence in 18 European countries: hard to maintain the hardening hypothesis. Prev. Med. 2015;81:314–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor L.S., Reitsma M.B., Gupta V., Ng M., Gakidou E. The effects of tobacco control policies on global smoking prevalence. Nat. Med. 2021;27(2):239–243. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01210-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorber S.C., Schofield-Hurwitz S., Hardt J., Levasseur G., Tremblay M. The accuracy of self-reported smoking: a systematic review of the relationship between self-reported and cotinine-assessed smoking status. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2009;11:12–24. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton T.F., Kozlowski L.T., Frecker R.C., Rickert WILLIAM, Robinson JACK. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Br. J. Addict. 1989;84(7):791–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain M.J., English L.M., Ramanandraibe N. An overview of tobacco control and prevention policy status in Africa. Prev. Med. 2016;91:S16–S22. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang E., Lee J.A., Cho H.J. Characteristics of hardcore smokers in South Korea from 2007 to 2013. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4452-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kien V.D., Jat T.R., Giang K.B., Hai P.T., Huyen D.T.T., Khue L.N., Lam N.T., Nga P.T.Q., Quan N.T., Van Minh H. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities among adult male hardcore smokers in Vietnam: 2010–2015. Int. J. Equity Health. 2017;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0623-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulik M.C., Glantz S.A. Similar softening across different racial and ethnic groups of smokers in California as smoking prevalence declined. Prev. Med. 2019;120:144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez A.D., Collishaw N.E., Piha T. A descriptive model of the cigarette epidemic in developed countries. Tob. Control. 1994;3(3):242–247. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews R., Hall W.D., Gartner C.E. Is there evidence of ‘hardening’among Australian smokers between 1997 and 2007? Analyses of the Australian National Surveys of Mental Health and Well-Being. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2010;44(12):1132–1136. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.520116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel P.A., Smith E.A., Malone R.E. The tobacco endgame: a qualitative review and synthesis. Tob. Control. 2016;25(5):594–604. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcombe R.G. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat. Med. 1998;17(8):857–872. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<857::aid-sim777>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo A., Cheng K.W., Chaloupka F.J., Shang C. The effect of MPOWER scores on cigarette smoking prevalence and consumption. Prev. Med. 2017;105:S10–S14. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palipudi K.M., Morton J., Hsia J., Andes L., Asma S., Talley B., Caixeta R.D., Fouad H., Khoury R.N., Ramanandraibe N., Rarick J., Sinha D.N., Pujari S., Tursan d’Espaignet E. Methodology of the global adult tobacco survey 2008–2010. Glob. Health Promot. 2016;23(2_suppl):3–23. doi: 10.1177/1757975913499800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreeramareddy C.T., Acharya K. JAMANetwork Open; 2021. Trends in prevalence of tobacco use by gender and socioeconomic status in 22 Sub-Saharan African Countries, 2003–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreeramareddy C.T., Pradhan P.M., Sin S. Prevalence, distribution, and social determinants of tobacco use in 30 sub-Saharan African countries. BMC Med. 2014;12:243. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0243-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreeramareddy C.T., Hon J., Abdulla A.M., Harper S. Hardcore smoking among daily smokers in male and female adults in 27 countries: A secondary data analysis of global adult tobacco surveys (2008–2014) J. Glob Health Rep. 2018;2 [Google Scholar]

- Sreeramareddy, C.T., 2021. Changes in adult smoking behaviours in ten Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) countries during 2008-2018-a test of ‘hardening’hypothesis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Thun M., Peto R., Boreham J., Lopez A.D. Stages of the cigarette epidemic on entering its second century. Tob. Control. 2012;21(2):96–101. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas S., Kumaranayake L. Constructing socio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21:459–468. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czl029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R. Tobacco control: present and future. Br. Med. Bull. 2006;77:123–136. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldl012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R., Jarvis M.J. Is “hardcore smoker” a useful term in tobacco control? Addiction. 2018;113:3–4. doi: 10.1111/add.14073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization WHO framework convention on tobacco control. World Health. 2003 Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Yin S., Ahluwalia I.B., Palipudi K., Mbulo L., Arrazola R.A. Findings from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey. Tob. Induc; Dis: 2019. Are there hardened smokers in low-and middle-income countries? p. 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used to prepare this report are publicly available at the website of Centre for Disease Control, Atlanta. The Stata code used for the analyses can be provided up on reasonable request.