Abstract

Brain‐segregation attributes in resting‐state functional networks have been widely investigated to understand cognition and cognitive aging using various approaches [e.g., average connectivity within/between networks and brain system segregation (BSS)]. While these approaches have assumed that resting‐state functional networks operate in a modular structure, a complementary perspective assumes that a core‐periphery or rich club structure accounts for brain functions where the hubs are tightly interconnected to each other to allow for integrated processing. In this article, we apply a novel method, persistent homology (PH), to develop an alternative to standard functional connectivity by quantifying the pattern of information during the integrated processing. We also investigate whether PH‐based functional connectivity explains cognitive performance and compare the amount of variability in explaining cognitive performance for three sets of independent variables: (1) PH‐based functional connectivity, (2) graph theory‐based measures, and (3) BSS. Resting‐state functional connectivity data were extracted from 279 healthy participants, and cognitive ability scores were generated in four domains (fluid reasoning, episodic memory, vocabulary, and processing speed). The results first highlight the pattern of brain‐information flow over whole brain regions (i.e., integrated processing) accounts for more variance of cognitive abilities than other methods. The results also show that fluid reasoning and vocabulary performance significantly decrease as the strength of the additional information flow on functional connectivity with the shortest path increases. While PH has been applied to functional connectivity analysis in recent studies, our results demonstrate potential utility of PH‐based functional connectivity in understanding cognitive function.

Keywords: cognitive aging, functional connectivity, persistent homology, resting‐state fMRI, topological data analysis

We proposed persistent homology (PH)‐based functional connectivity to quantify the distribution of the strength of resting‐state brain network information flow, focusing on whole‐brain integration rather than brain segregation. The proposed PH‐based functional connectivity at rest explained fluid reasoning, and vocabulary abilities, while brain system segregation and graph theory‐based network topology measures did not. The weaker the strength of the additional information flow on the resting‐state brain connectivity with the shortest path, the better the cognitive ability in fluid reasoning and vocabulary.

1. INTRODUCTION

The relationship between resting‐state functional networks and cognition (Chan et al., 2014; Cohen & D'Esposito, 2016; Hausman et al., 2020; Khasawinah et al., 2017), cognitive aging (Varangis et al., 2019), and cognitive reserve (Stern et al., 2021) has been widely investigated. Brain functional connectivity has been quantified in various ways; for example, average correlation within/between networks (Hausman et al., 2020; Khasawinah et al., 2017) and brain system segregation (BSS; Chan et al., 2014; Cohen & D'Esposito, 2016). These measurements are calculated based on the assumption that the brain network structure is modular. However, a complementary perspective assumes that a core‐periphery or rich club structure accounts for brain functions where the hubs are tightly interconnected to each other to allow for integrated processing. (Bertolero et al., 2015; Gu et al., 2020; Sporns, 2013; van den Heuvel & Sporns, 2013).

Alternatively, graph theory‐based analysis quantifies the topology of the brain network structure. For example, the segregation attribute can be measured by calculating cluster coefficient and local efficiency, or the integration attribute can be measured by calculating global efficiency and shortest path length (Bassett & Sporns, 2017; Medaglia et al., 2015; Rubinov & Sporns, 2010). Many existing network topology methods based on graph theory are calculated from a binary adjacency connectivity matrix obtained from thresholding at a specific value of the association measure. Thus, although the existing graph theory‐based analysis helps researchers explore the effects of brain organization on cognitive functions and diseases, such results are difficult to reproduce and might critically depend on the thresholding choice (Boersma et al., 2013; Stam et al., 2014; van Wijk et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2016). As interest in weighted networks has increased, there have been many studies on a network topology for weighted networks (Opsahl et al., 2010; Rubinov & Sporns, 2010; Shine et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2008). But, these methods based on graph theory are locally evaluated at each node and a single edge. Although these measurements are often aggregated to obtain a global network statistic from a single graph (e.g., average shortest path length and average degree, etc.), these measurements are not enough to explain the global topological structure of the complex network (Sizemore et al., 2017).

Recent studies have used the minimum spanning tree (MST) method to address the thresholding dependency in graph theory‐based analysis for the brain organization (Boersma et al., 2013; Cao et al., 2020; Kruskal, 1956; Saba et al., 2019; van Dellen et al., 2018). The MST method locates a unique spanning tree that connects N brain regions with N‐1 edges at minimum cost (i.e., maximizing synchronization between brain regions). Under the assumption that the brain network is structured as a kind of transportation network, MST will serve as an important backbone of information flow in a weighted brain network (Blomsma et al., 2022; Saba et al., 2019; van Dellen et al., 2018; van den Heuvel et al., 2012). The MST considers topological efficiency (MST has the N‐1 shortest path) and strength efficiency (MST has the highest connectivity strength among the possible trees). That is, MST constructs the backbone structure containing the strongest connections from the set of all available weighted connections that connect whole brain regions with the smallest number of edges.

A new, increasingly popular approach to uncover the topology patterns of functional connectivity is to use ideas from algebraic topology (Gracia‐Tabuenca et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2012; Saggar et al., 2018, 2022; Sizemore et al., 2017; Stolz et al., 2021). Topological data analysis (TDA) is a relatively new and still developing branch of statistics to infer, analyze, and exploit the underlying geometric or topological features of complex data (Boissonnat et al., 2018; Chazal & Michel, 2021; Ghrist, 2008; Hatcher, 2002; Zomorodian & Carlsson, 2005). Recently, TDA has been applied to fMRI data with techniques used in TDA to study the structure of complex data sets: persistent homology (PH) and mapper. While mapper focuses on mapping high‐dimensional fMRI data to a graph‐like structure, which allows for the visualization and analysis of complex data (Saggar et al., 2018, 2022), PH focuses on extracting the topological features that persist over multiple scales, which can reveal patterns of brain activity (Cassidy et al., 2015; Choe et al., 2018; Gracia‐Tabuenca et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2012; Shnier et al., 2019). In these studies, PH has also been considered as a way to address the thresholding issue of the brain network analysis. The basic idea of PH is to study data through their low‐dimension topological features, which translate into connected components (dimension 0), loops (dimension 1), voids (dimension 2), and so on. To capture the low‐dimension topological features, TDA builds an abstract structure upon the individual nodes in the network, which is called a simplicial complex. In a network structure, the simplicial complex consists of nodes and edges, like a subgraph (for the overall concept of TDA and a detailed explanation of simplicial complex with point cloud data, which is a basic data form in TDA, refer to Chazal and Michel (2021), Ghrist (2008), and Hatcher (2002)). There are many ways to construct the simplicial complex. A common method in network settings is to add edges to the nodes one by one in a way that the edge having a stronger weight is added first. Nodes are connected to each other with edges making connected components (dimension 1) or loops (dimension 2). If the network is even more complex, it is hard to find an appropriate number of edges added in the simplicial complex that will capture all of the topological features in the network. If, instead, all possible thresholding values are considered, the set of corresponding structures can capture the relevant topological features of the network. This is the focus of PH. The set of simplicial complexes defined as the edges added into the space is called filtration. PH tracks topological features that appear (birth) or disappear (death) as the filtration increases. In this way, PH captures topological features in the brain network, as well as avoids the thresholding issue. Furthermore, our study focuses on the topological features of brain networks involved in specific topological statuses rather than a full exploration of the global network structure. Thus, we chose to use PH, a method that does not require thresholding, to identify these features. In fact, the algorithm for finding death filtration values (e.g., 1‐correlation coefficients between node pairs) of dimension 0 PH (PH capturing connected components) in the network settings is the same as that for finding heights of the MST (Kuang et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2012). That is, the MST is a tree composed of only edges having death filtration of dimension 0 PH, and dimension 0 PH has distribution information of edge weights of the structure with the most efficient information flow. From these characteristics, PH quantifies the pattern of functional connectivity of the MST network topology structure, which ensures the most efficient integrated processing of brain regions.

While the MST method only keeps the acyclic graph with no cycles (i.e., MST keeps only connected components with no loop structure), the PH method separately tracks the information of both connected components (dimension 0) and loops (dimension 1). Thus, PH can consider additional information through loops to MST before all nodes are connected. In addition, recent studies of MST network analysis in brain networks have viewed the constructed MST as a binary network and calculated the topological characteristics of the MST, such as the number of leaves (nodes with degree 1), the maximum betweenness of nodes, and so forth (Boersma et al., 2013; Cao et al., 2020; Saba et al., 2019; Stam et al., 2014; van Dellen et al., 2018). From this perspective, MST network analysis differs slightly from the PH approach. MST network analysis quantifies the way the nodes in MST are arranged, while PH, when dimension 0 is only considered in the network setting, quantifies the edge weight pattern assigned at MST and loops added to MST.

In the current study, we call the tree connecting all brain regions with no loops (i.e., MST) and additional loops of this structure “backbone” and “cycle, ” respectively. We introduce measures describing the distribution of weights in the backbone structure and cycle structure and call these measures PH‐based functional connectivity. Briefly, the backbone structure describes brain‐integrated processing, and the cycle structure describes how the brain regions are interconnected during brain‐integrated processing. Thus, the distribution of weights in the cycle structure when the backbone structure is given can explain how tightly the hubs are interconnected to each other during brain‐integrated processing. We also investigate the relationship between PH‐based functional connectivity and cognitive aging. In addition, we compare the amount of variability in cognitive ability explained by PH‐based functional connectivity to that explained by measures describing brain organization (network topology and MST), average functional connectivity, and BSS.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Resting‐state fMRI data acquisition

The resting‐state fMRI data used in this article were obtained from Reference Ability Neural Network (RANN) Study and Cognitive Reservation (CR) Study at Columbia University Irving Medical Center (Stern, 2009; Stern et al., 2014, 2018). The data set is composed of 279 participants (gender: 159 females, 120 males; age: 53.57 16 [range 20–80]). A detailed description of the data set is available in previous reports (Stern, 2009; Stern et al., 2014; Varangis et al., 2022).

MRI data were collected on a 3.0 T Philips Achieva Magnet. There were two, 2‐hr MR imaging sessions to accommodate the 12 fMRI activation tasks as well as the additional imaging modalities. At each session, T1‐weighted MPRAGE scan (repetition time (TR) = 6.5 ms, echo time (TE) = 3 ms, flip angle = 8, field of view = 254 mm × 254 mm, in‐plane resolution = 256 × 256, 165–185 axial slices, slice‐thickness = 1 mm, gap = 0 mm) was obtained for later use in preprocessing. Resting‐state fMRI blood oxygen level‐dependent (BOLD) scans (TR = 2000 ms, TE = 20 ms, flip angle = 72, in‐plane resolution = 112 × 112, 37 axial slices, slice‐thickness = 3 mm, gap = 0 mm, scan time = 9.5 min, 285 volumes) were conducted. The participants were instructed to lie still with their eyes closed and not think of anything in particular while staying awake.

2.2. Resting‐state fMRI data preprocessing

Images were preprocessed using an in‐house developed native space method (Razlighi et al., 2014). Briefly, the preprocessing pipeline included slice‐timing correction and motion correction (MCFLIRT) performed using the FSL package (Jenkinson et al., 2012). All volumes were registered (6 df, 256 bins mutual information, and sinc interpolation) to the middle volume. Frame‐wise displacement (FWD; Power et al., 2012) was calculated from the six motion parameters and root‐mean‐square difference (RMSD) of the BOLD percentage signal in the consecutive volumes. To be conservative, the RMSD threshold was lowered to 0.3% from the suggested 0.5%. Contaminated volumes were then detected by the criteria FWD > 0.5 mm or RMSD > 0.3% and replaced with new volumes generated by linear interpolation of adjacent volumes. Volume replacement was performed before temporal filtering (Carp, 2013). Volume replacement was performed before temporal filtering (Cole et al., 2014). Flsmaths–bptf was used to pass motion‐corrected signals through a bandpass filter with cut‐off frequencies of 0.01 and 0.09 Hz. Finally, the processed data were residualized by regressing out the FWD, RMSD, left and right hemisphere white matter, and lateral ventricular signals (Birn et al., 2006). Using advanced normalization tools (ANTs), each T1 image was registered to the 2 mm MNI template, and the residualized images were warped to the 2 mm MNI template.

2.3. Cognitive abilities

Twelve measures were selected from a battery of neuropsychological tests to assess cognitive functioning (Salthouse et al., 2015). Fluid reasoning was assessed with scores on three different tests: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) III Block design task, WAIS‐III Letter–Number Sequencing test, and WAIS‐III Matrix Reasoning test. For processing speed, the Digit Symbol subtest from the WAIS‐Revised (Wechsler, 1981). Part A of the Trail making test and the Color naming component of the Stroop (Golden, 1978) test were chosen. Three episodic memory measures were based on sub‐scores of the Selective Reminding Task (Buschke & Fuld, 2011): the long‐term storage sub‐score, continuous long‐term retrieval, and the number of words recalled on the last trial. Vocabulary was assessed with scores on the vocabulary subtest from the WAIS‐III, the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading, and the American National Adult Reading Test (Grober & Sliwinski, 1991). Domain scores were generated by z‐scoring performance on each task relative to the full study sample, then average z‐scores were computed for tasks within each domain (four domain z‐scores: Fluid Reasoning, Processing Speed, Episodic Memory, and Vocabulary).

2.4. Functional connectivity

The nodes were defined using an atlas derived from Power et al. (2011) and the mean time series of each node was extracted. Due to the lack of whole cerebellum coverage during resting‐state scans, only noncerebellar ROIs were included in our analyses (264 ROIs − 8 cerebellar ROIs = 256 ROIs in total). Pearson correlations were then performed for all pairwise combinations of ROIs. Thus, 32, 640 (=256 × 255/2) functional connectivity pairs (or edges) were used in our analysis. In this article, we use absolute Pearson correlation coefficients to take both positive and negative synchronization of brain signals into account.

2.5. Measures for comparisons

2.5.1. Global network topology measures

Since PH‐based measures quantify the strength of whole‐brain (i.e., global) backbone organization, we considered three selected global network topology measures to be compared with PH‐based measures (Rubinov & Sporns, 2010): (1) characteristic path length, defined as the average shortest path length between all nodes; (2) transitivity, defined as the relative number of triangles in the graph, compared to the total number of connected triples of nodes; and (3) global efficiency, defined as the average reciprocal of the shortest path length between all nodes. The characteristic path length and global efficiency are related to network organization efficiency, and transitivity is related to the segregation of network organization. Since network topology measures differ according to the thresholding selection, we calculated the network topology measures at each edge density (from 1% to 20%).

2.5.2. MST‐based measures

We used two global MST‐based measures (Saba et al., 2019): (1) maximum betweenness, defined as the maximum number of shortest paths through each node in a graph, and (2) leaf fraction, defined as the fraction of the number of nodes with degree 1 among the number of all possible edges. We can quantify the configuration of MST with maximum betweenness and leaf fraction. High maximum betweenness and high leaf fraction indicate that MST is more likely to appear as a star‐type, while low maximum betweenness and low leaf fraction indicate line‐type MST (van Dellen et al., 2018).

2.5.3. Connectivity‐based measures

We quantified individual resting‐state functional connectivity with the mean Fisher z‐transformed correlation coefficient of all pairs of nodes. In addition, we considered measures representing the segregation of brain organization based on functional connectivity. We used the BSS (Chan et al., 2014), defined as follows:

Brain system segregation = ,

Where is the mean Fisher z‐transformed correlation coefficient between nodes within the same system [defined by Power et al. (2011)] and is the mean Fisher z‐transformed correlation coefficient between nodes of one system to all nodes in other systems.

2.6. Persistent homology‐based functional connectivity

2.6.1. Overview of persistent homology‐based functional connectivity in brain network

Topological data analysis (TDA) is a branch of mathematics that uses topology, which studies geometric properties that remain unchanged under continuous transformations, to analyze complex data. In particular, it provides tools to study the shape and connectivity of data sets, regardless of the specific values of the data points. PH is a specific method within TDA that allows us to extract important features of the data and measure how persistent they are across different scales. PH represents the data as a simplicial complex, where each node represents a data point, and each edge connects sufficiently close or similar nodes. By constructing a nested sequence of simplicial complexes that capture the topology of the data at increasing resolutions, PH can identify the most persistent topological features and track their evolution across scales.

In recent years, PH has gained popularity in neuroscience, particularly in the analysis of brain networks (Cassidy et al., 2015; Choe et al., 2018; Gracia‐Tabuenca et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2012). Brain networks refer to the patterns of functional connectivity between different brain regions, which can be represented as a graph or network where nodes correspond to brain regions, and edges represent the strength of functional connectivity between them. By applying PH to brain networks, we can identify the persistent topological features of brain connectivity and gain insights into the functional organization of the brain. For example, PH can detect the number of connected components (dimension 0) and loops (dimension 1) of the brain functional organization at each scale, revealing the integration process and complexity of the brain network.

To apply PH to brain functional networks, we first need to construct a simplicial complex from the data. In the context of functional connectivity, we can think of a simplicial complex as a network of nodes and edges, where the nodes represent brain regions and the edges represent the functional connections between them. Once the nodes and edges have been defined, we can assign weights to the edges based on the strength or intensity of the functional connections between the nodes. These weights can be determined using various measures, such as correlation coefficients, coherence, or mutual information. In this study, we calculated Pearson correlation coefficients upon the 256 noncerebellar ROIs from the Power atlas for the weights. Once we have constructed the simplicial complex, we can then calculate the PH of the functional connectivity. We use a technique called “filtration.” Filtration involves gradually adding edges to the simplicial complex to create a sequence of nested subcomplexes. At each step in the filtration, we calculate the homology of the subcomplex and track how the topology changes as edges are added. PH tracks topological features that appear (birth) or disappear (death) as the filtration increases. In this way, PH captures topological features in the brain network, as well as avoids the thresholding issue.

In the context of brain networks, the creation of a connected component, which gradually grows larger as nodes are added, can be interpreted as brain regions being functionally connected in an efficient way. This is because a multi‐scale simplicial complex combines nodes into connected components with the strongest weight among the nodes that have not yet been connected to a giant connected component. This results in the most efficient information flow structure. In our study, we leverage this concept from PH to gain insights into functional connectivity involving brain functional integrative processing. We aim to develop an alternative approach to standard functional connectivity by quantifying the pattern of information flow during integrated processing. Furthermore, we also consider the edges that form cycles within a connected component, which can be seen as the complexity of an efficiently integrated brain structure.

2.6.2. Multi‐scale simplicial complex

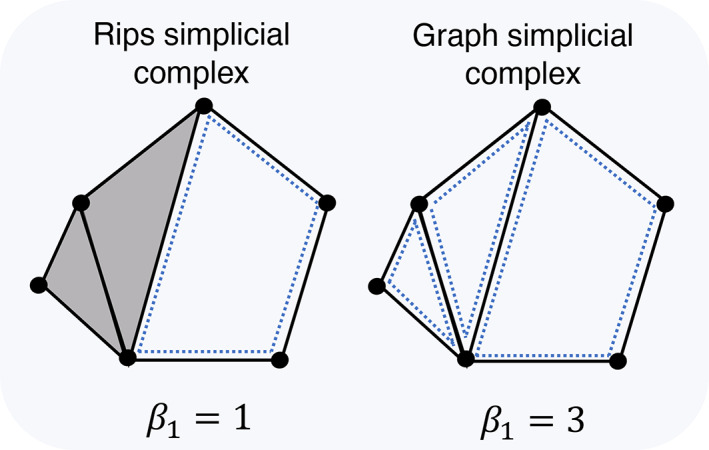

Rips filtration is the most natural way to construct a set of multi‐scale simplicial complexes due to its computational efficiency (Boissonnat et al., 2018). Many TDA applications of brain networks have also used Rips filtration to calculate PH. Several studies have directly applied Rips complex filtration using the distance between nodes [e.g., the distance between nodes can be defined as (or ), when the weighted network is constructed using Pearson correlations ()] (Gracia‐Tabuenca et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2012; Liang et al., 2021; Shnier et al., 2019; Stolz et al., 2021). However, they considered only dimension 0 topological features (i.e., connected components). This is because the definition of dimension 1 topological features (i.e., loops) under Rips simplicial complex only covers non‐clique cycles (for example, a triangle [3‐clique] is a connected component, not a loop in Rips simplicial complex), which is not easily observable in a complex network. Here, to obtain a more interpretable and observable loop structure of a complex functional brain network, we use the graph simplicial complex, which is similar to the Rips simplicial complex but considers only 0‐ and 1‐ simplices (i.e., nodes and edges), excluding 2‐ and 3‐ simplices (i.e., filled triangles and tetrahedrons) and higher‐order simplices from Rips complexes (Figure 1). Although graph filtration does not consider higher than order two relationships between nodes as connected components, we can use graph filtration to keep information of edges making all kinds of cycles (i.e., triangles, rectangles, pentagons, etc.), which describe the relationship between more than three nodes.

FIGURE 1.

Example of Rips and graph simplicial complex. Rips simplicial complex (left) assigns grey faces to three cliques (triangles) and so has one loop (). Whereas graph simplicial complex (right) only considers points and edges and so has three loops in this example ().

2.6.3. Algorithms for graph filtration and persistent homology

To construct the graph filtration, we used the distance between nodes as Rips filtration does. The algorithm for Rips filtration is to assign edges between two nodes of which distance is shorter than the filtration distance as the distance increases. In fact, this algorithm is the same as the MST algorithm as far as PH only considers connected components (Kuang et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2012). MST can be created by sorting all edges in the network from the highest weight edge to the lowest weight edge (from the shortest distance edge to the longest distance edge), assigning one at a time, and keeping edges that make trees with no cycle (Kruskal, 1956). To address cycles, the algorithm of the graph filtration keeps all edges in the MST algorithm, even if edges create cycles, but saves them separately (tree‐making edges/cycle‐making edges). Figure 2 illustrates how to construct the graph filtration with a toy example. With four nodes in the example, six edges (= 4 × 3/2) are sorted on their weights in a decreasing way. When an edge is added one at a time, the edge assumes one of two roles: (1) it connects nodes that have not yet been connected so that one of the connected components dies (red solid edge in Figure 2) or (2) it connects already connected nodes, creating a new cycle (grey dashed edge in Figure 2). Before any edge is added, all nodes are connected components by themselves; thus, the number of connected components begins with the number of nodes (N) and becomes one connected component connected by N − 1 edges. That is, each connected component has a birth time of zero and dies at the weight of that edge when each edge is added. Similarly, the added edge takes one of the two roles; therefore, out of the total N (N − 1)/2 edges, except for the N − 1 edge that reduces the connected component, the remaining (N − 1) (N − 2)/2 edges are involved in creating cycles. Here, each cycle has the birth time of the edge weight when the edge is included and does not die even when all edges are added. Therefore, each edge weight is included in either the death weight set of dimension 0 topological features or the birth weight set of dimension 1 topological features. In a formal definition,

where is a death weight set of connected components, is a birth weight set of cycles, is an edge weight set, is the ith highest edge weight, and is the dimension Betti number (i.e., the number of dimension topological features) of the simplicial complex when edge with the weight is added. The birth time set of dimension 1 topological features, , can also be decomposed as cycle weights before and after all nodes are connected, as below:

and

where is a birth weight set of cycles born before all nodes are connected, is a birth weight set of cycles born after all nodes are connected, and is the minimum death edge weight of dimension 0 topological features.

FIGURE 2.

An example of graph filtration: Graph filtration consists of four nodes and six edges. Each time a solid red edge is added, the number of connected components () decreases by 1, and each time a dashed grey edge is added, the number of cycles () increases by 1.

2.6.4. PH‐based functional connectivity

PH calculates the number of topological features across a whole range of filtration values (i.e., all possible edge weights in the network). Simultaneously, PH stores edge weight information in (for dimension 0) and (for dimension 1) when the number of topological features increases (for dimension 0) or decreases (for dimension 1) by one. While doing it, at some point, all nodes are connected into one connected component, which is the tree (i.e., no loops) connecting all N nodes with N − 1 edges, of which weights are in (i.e., MST). The studies related to MST have described the structure having MST as the “backbone” of the information flow (Blomsma et al., 2022; Saba et al., 2019; van den Heuvel et al., 2012), and here, we also called this structure “backbone.” Also, when edges with weights in are assigned to the network, additional triangles are created upon the backbone structure, and we called these edges with weights in “cycle.”

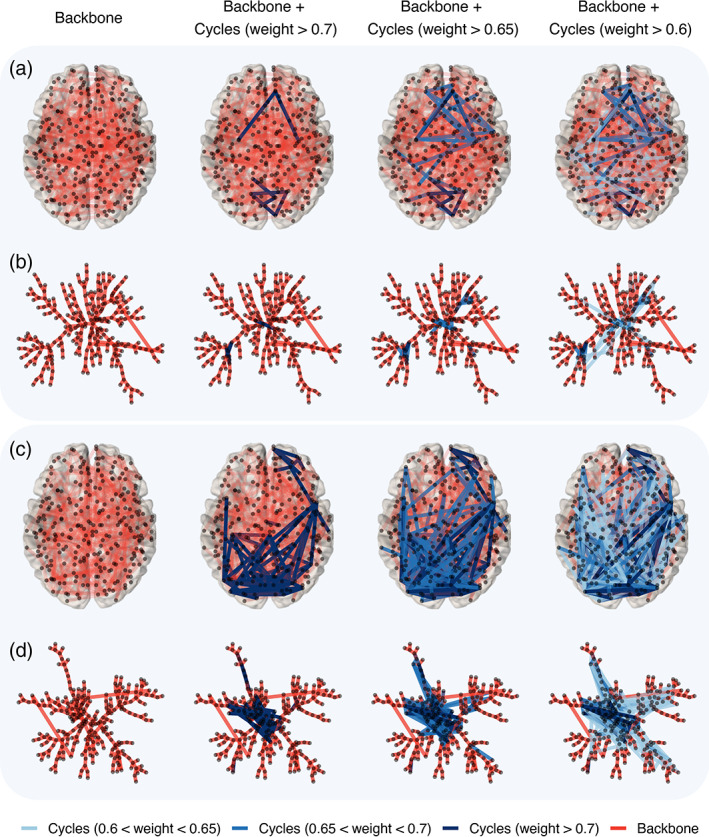

To describe the distribution of functional connectivity in the backbone and cycle structures with one value across a whole range of filtration values, we summarized the weight sets and with three measures: (1) backbone strength, defined as the average of elements in ; (2) backbone dispersion, defined as the range (the largest value minus the smallest value) of elements in ; and (3) cycle strength, defined as the average of values in . That is, backbone strength and cycle strength describe the mean functional connectivity of the brain backbone structure and the cycle structure, respectively. Since the backbone structure describes brain‐integrated processing, and the cycle structure describes how the brain regions are interconnected during brain‐integrated processing, interpretation of both backbone strength and cycle strength in the brain network can explain how tightly the hubs are interconnected to each other during brain‐integrated processing. For example, as shown in Figure 3, there are cases where two resting‐state brain networks have the same backbone strength but significantly different cycle strengths. Such information cannot be found only with dimension 0 PH (or MST), and additional cycle information in the backbone structure provides important information about the pattern of information flow. In Figure 3, a and b (c and d) visualize the functional network of an individual with the cycle strength at the first (third) quantile. At the same level of backbone strength, brain networks with high cycle strength have more cycles being involved in the flow of information when information begins to flow (i.e., with high functional connectivity, in this example, we only considered when the weight is higher than 0.6). Therefore, even with a similar backbone strength, low cycle strength is interpreted as information flow patterns with high strength are transmitted through the backbone (like highways) rather than additional cycles (like rural roads).

FIGURE 3.

Visualization of functional connectivity illustrating backbone structure and additional cycle structure of two individuals—(a, b) Functional connectivity of individual who has first quantile cycle strength; (c, d) functional connectivity of individual who has third quantile cycle strength. a and c show a top view of brain connectivity with 264 power ROIs' MNI coordinates, and b and d visualize a tree‐like graph layout based on a minimum spanning tree. The red line represents an edge in the backbone structure, and blue‐tone lines represent edges making additional cycles (Darker blue represents a cycle with stronger edge weight). The first column visualizes only the backbone structure, and the second to fourth columns visualize the cycles in which weights are added in descending order. Only cycles having weights greater than the average backbone strength of 0.6 are shown in this figure. Both individuals have the same backbone strength.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographics

The characteristics of 279 participants are displayed in Table 1. The participants were aged from 20 to 80, and the younger (ages 20–39) age group had relatively more females and thicker cortexes than the middle‐aged (ages 40–59) and older (ages 60–80) age groups. The four domain z‐score for cognitive abilities and the three PH‐functional connectivity measures are also presented separately for three age groups.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of participants.

| Overall (N = 279) | Younger adults (ages 20–39; N = 74) | Middle‐aged adults (ages 40–59; N = 68) | Older adults (ages 60–80; N = 137) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 53.573 (16.835) | 29.419 (5.397) | 51.279 (5.563) | 67.759 (5.065) |

| Education | 16.222 (2.354) | 16.041 (2.529) | 16.206 (2.315) | 16.328 (2.285) |

| Gender (Female) | 159 (57%) | 51 (68.9%) | 32 (47.1%) | 76 (55.5%) |

| Mean Thickness | 2.549 (0.116) | 2.633 (0.104) | 2.564 (0.093) | 2.497 (0.104) |

| Fluid Reasoning | 0.016 (0.793) | 0.577 (0.772) | 0.013 (0.770) | −0.285 (0.642) |

| Episodic Memory | 0.015 (0.960) | 0.635 (0.701) | 0.023 (0.949) | −0.324 (0.923) |

| Vocabulary | 0.068 (0.901) | −0.380 (0.956) | 0.041 (0.901) | 0.324 (0.770) |

| Processing Speed | 0.050 (0.815) | 0.634 (0.759) | 0.169 (0.671) | −0.326 (0.702) |

| Backbone Strength | 0.647 (0.036) | 0.648 (0.042) | 0.648 (0.035) | 0.647 (0.033) |

| Backbone Dispersion | 0.485 (0.047) | 0.493 (0.053) | 0.493 (0.043) | 0.478 (0.044) |

| Cycle Strength | 0.504 (0.035) | 0.503 (0.041) | 0.507 (0.034) | 0.503 (0.033) |

Note: Means (standard deviations in parentheses) or frequencies (percentage of sample in parentheses) are reported for each sample.

3.2. Performance of PH‐based functional connectivity

We compared the performance of PH‐based functional connectivity measures in explaining cognitive performance with MST‐based, functional connectivity‐based, and network topology measures. We fitted each linear model with each z‐score of cognitive ability as a dependent variable and one of the measures (three PH‐based functional connectivity, two MST‐based measures, two functional connectivity‐based measures, and three network topology measures) as a predictor variable controlling for age, education, gender, and mean cortical thickness. Figure 4a displays the partial of PH‐based functional connectivity measures, MST‐based measures, and connectivity‐based measures with red‐tone, blue‐tone, and grey‐tone bars, respectively. For fluid reasoning and vocabulary, cycle strength significantly explained variation of cognitive abilities (p < .010) with higher partial than all measures of MST and functional connectivity. For episodic memory, cycle strength also had the significant and highest partial (p < .010) among all measures, but backbone strength and overall functional connectivity also significantly explained the variation in cognitive ability (p < .050).

FIGURE 4.

(a) Partial comparison of PH‐based measures with MST‐based measures and connectivity‐based measures in relation to four cognitive endpoints. The partial is controlled by age, education, gender, and mean cortical thickness in each linear model. The partial of PH‐based functional connectivity measures, MST‐based measures, and connectivity‐based measures are represented with red‐tone, blue‐tone, and grey‐tone bars, respectively. (b) Partial comparison of PH‐based measures with network topology measures at each thresholding value (0.01–0.20 by .01). The partial is controlled by age, education, gender, and mean cortical thickness in each linear model. Grey‐tone points represent partial of network topology measures at each thresholding value. Red‐tone horizontal lines represent partial of PH‐based functional connectivity measures across the whole range of thresholding values (*p < .050, **p < .010, ***p < .001).

Since graph theory‐based network topology measures were different according to the thresholding values, we compared the performance of PH‐based measures in explaining cognitive performance with graph network topology at each edge density. Figure 4b displays the partial of PH‐based functional connectivity measures and network topology measures calculated at each edge density as a thresholding value from 0.01 to 0.20 increased by 0.01. Grey‐tone points represent partial of network topology measures at each thresholding value. Red‐tone horizontal lines represent partial of PH‐based functional connectivity measures across the whole range of thresholding values. Figure 4b shows that cycle strength significantly explains variation in the cognitive ability of fluid reasoning, vocabulary, and episodic memory (p < .010), and backbone strength significantly explain variation in episodic memory cognitive ability (p < .050), as shown in Figure 4a. Network topology measures at some point of thresholding value less than 0.1 (transitivity at 0.01–0.09, characteristic path length at 0.05–0.09, and global efficiency at 0.01) significantly explain variation in episodic memory (p < .050). However, networks from our data set are not “complete” (all brain regions are not connected), with edge density less than 0.1, and in fact, Figure 4b shows that the results of partial are not stable at thresholding less than 0.1. After thresholding 0.1, the results of partial become stable but not significant.

3.3. Effects of PH‐based functional connectivity

Table 2 presents the correlation coefficients between PH‐based functional connectivity and two demographic variables: age and cortical thickness. Among the three PH‐based functional connectivity measures, the brain backbone dispersion was related to both age (= − .137, 95% CI −0.254 to −0.020, p < .05) and mean cortical thickness ( = .217, 95% CI 0.102–0.332, p < .001); the relationship between brain backbone dispersion and mean cortical thickness was significant even after multiple comparisons correction. As a post hoc test, we also conducted a mediation analysis for brain backbone dispersion to examine a potential mediating role of cortical thickness in the relationship between age and backbone dispersion. Figure 5 displays the result of the mediation analysis. The mediation analysis was implemented with a bootstrapping process to construct confidence intervals for the indirect effect and proportion of mediated effect (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). The mean cortical thickness fully mediated the effect of age on brain backbone dispersion (standardized indirect effect = −0.110, 95% CI −0.186 to −0.040, p < .010), and the proportion of the mediated effect of mean cortical thickness was 0.802 with 95% CI 0.176–4.310 (p < .050).

TABLE 2.

Correlation between age and cortical thickness and PH‐based functional connectivity measures.

| PH‐measure | Standardized correlation coefficients [95% CI] | p‐value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Backbone strength | −0.016 | [−0.134, 0.102] | .791 |

| Age | Backbone dispersion | −0.137 | [−0.254, −0.020]* | .022 |

| Age | Cycle strength | −0.004 | [−0.122, 0.113] | .941 |

| Cortical thickness | Backbone strength | −0.011 | [−0.128, 0.107] | .860 |

| Cortical thickness | Backbone dispersion | 0.217 | [0.102, 0.332]*** | <.001 |

| Cortical thickness | Cycle strength | −0.031 | [−0.149, 0.087] | .607 |

Note: Statistically significant values after FDR correction are bolded.

p < .050;

p < .001.

FIGURE 5.

Mediation analysis. The path diagram (including standardized coefficients and significances) of the mediation analysis demonstrates that cortical thickness fully mediates the effect of age on backbone dispersion (*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001).

As shown in Figure 4, overall functional connectivity appears to account significantly for the variability of episodic memory performance, as well as backbone strength and cycle strength. This means that the effect of backbone strength and cycle strength may be affected by overall functional connectivity. Therefore, in order to investigate the association between cycle strength and cognitive abilities regardless of overall functional connectivity level, a regression model was fitted, controlling the overall functional connectivity along with age, gender, education, and mean cortical thickness. To control for multiple comparisons, we used the False Discovery Rate (FDR) method with a significance level of .05 and the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure for p‐value adjustment. Table 3 presents the linear regression results using each z‐score in four domains of cognitive performance as a dependent variable and one of three PH‐based functional connectivity measures as a predictor after controlling age, education, mean cortical thickness, and overall functional connectivity. Cycle strength was negatively associated with fluid reasoning ( = −.198, 95% CI −0.348 to −0.047, p < .050), and vocabulary ( = −.204, 95% CI −0.363 to −0.044, p < .050) and these relationships survived after multiple comparisons correction.

TABLE 3.

Linear regression between cognitive performances and PH‐measures.

| Cognitive performance | PH‐measure | Standardized correlation coefficients [95% CI] | p‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluid reasoning | Backbone strength | −0.002 [−0.282, 0.279] | .991 |

| Fluid reasoning | Backbone dispersion | 0.092 [−0.007, 0.191] + | .071 |

| Fluid reasoning | Cycle strength | −0.198 [−0.348, −0.047]* | .011 |

| Episodic memory | Backbone strength | 0.054 [−0.244, 0.351] | .724 |

| Episodic memory | Backbone dispersion | 0.053 [−0.053, 0.16] | .325 |

| Episodic memory | Cycle strength | −0.122 [−0.284, 0.039] | .139 |

| Vocabulary | Backbone strength | −0.114 [−0.41, 0.182] | .450 |

| Vocabulary | Backbone dispersion | 0.081 [−0.024, 0.187] | .132 |

| Vocabulary | Cycle strength | −0.204 [−0.363, −0.044]* | .013 |

| Processing speed | Backbone strength | 0.010 [−0.278, 0.298] | .945 |

| Processing speed | Backbone dispersion | 0.080 [−0.022, 0.182] | .127 |

| Processing speed | Cycle strength | −0.117 [−0.273, 0.039] | .142 |

Note: All regressions were controlled for age, gender, education, mean cortical thickness, and overall functional connectivity. Statistically significant values after FDR correction are bolded.

p < .100;

p < .050.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. PH‐based functional connectivity explains cognitive abilities

In neuroscience, researchers have used various methods to describe how the brain network functionally works during the performance of cognitive tasks or rest. For example, recent studies investigating the relationship between functional connectivity and cognitive abilities have mainly utilized average functional connectivity (over the whole brain or within or between networks; Cohen & D'Esposito, 2016; Hausman et al., 2020; Khasawinah et al., 2017), the BSS (Chan et al., 2014), and graph theory‐based network topology measures (Medaglia et al., 2015). In the current study, we introduced PH‐based functional connectivity measures and applied these measures to investigate how functional connectivity in the most efficient information flow structure explains cognitive abilities. PH‐based functional connectivity accounts for the pattern of information flow when all brain regions are connected into one connected component (i.e., integration) in the most efficient way (see Section 2.5).

From that point of view, there are several advantages of PH‐based functional connectivity compared to the existing functional connectivity measures. First, PH‐based functional connectivity is robust to weak, noisy connectivity. Overall functional connectivity, which is calculated by averaging all connectivity values across the whole brain, tends to be biased downwards due to many weak connectivity values. On the other hand, PH‐based functional connectivity only considers the edges involved in connecting all brain regions efficiently and ignores the edges with connectivity after all brain regions are connected. Thus, PH‐based functional connectivity can relieve the effect of weak, noisy edge weights. Second, PH‐based functional connectivity describes brain‐integrated processing of information flow. The existing methods describing functional connectivity, such as functional connectivity within/between networks or BSS, assume that brain network structure is modular. However, it has often been hinted that the brain integration attribute may play as important a role in explaining brain behavior as the segregation attribute (Gu et al., 2020; van den Heuvel & Sporns, 2013). In previous studies, overall functional connectivity was mainly used as a measure of brain integration properties. But, as mentioned earlier, overall functional connectivity is highly likely to be underestimated in describing brain integration attributes. On the other hand, PH‐based functional connectivity measures can explain the integration properties more intuitively because they consider the tree connecting all brain regions. Lastly, PH is free from the thresholding issue that has been frequently pointed out in the graph theory‐based network analysis (Boersma et al., 2013; Stam et al., 2014; van Wijk et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2016). Thus, PH‐based functional connectivity has an advantage in that it can bring consistent analysis results regardless of the thresholding choice (Cassidy et al., 2015; Choe et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2012). We also found that results from topology network measures based on graph theory were unstable when the network was quite sparse, while PH‐based functional connectivity measures are the same across the whole range of filtration (see Figure 4b).

When looking at the performance of PH‐functional connectivity in explaining cognitive abilities, the results in Figure 4 show that PH‐based functional connectivity performed better in explaining cognitive ability than overall functional connectivity, brain segregation, or graph theory‐based measures. These results suggest that cognitive abilities have more to do with the pattern of information flow over the whole brain than with connections within and between the networks.

4.2. Edge weight distribution of brain backbone and cortical thickness

One of the main concepts of PH‐based functional connectivity in the current study is “backbone.” The algorithm for finding edges involving reducing the number of connected components (dimension 0 topological features) in the graph filtration PH setting (see Section 2.5) is the same as MST algorithm. Since the union of all shortest paths coincides with the MST, the MST might represent the critical backbone of the information flow (Cao et al., 2020; Saba et al., 2019; Tewarie et al., 2014; van Dellen et al., 2018; Van Mieghem & Magdalena, 2005), and thus the death weight set of connected components, , has information of backbone weights. Among our PH‐functional connectivity measures, backbone strength and backbone dispersion describe the distribution of weights of backbone structure. Backbone dispersion, which is the range of the distribution of , represents the strength difference in the critical backbone of the information flow. In the current study, backbone dispersion was positively associated with the mean cortical thickness (see Table 2 and Figure 5). This suggests that the greater the thickness of the grey matter cortex of the brain, the greater the difference in the strength of connections in the flow of information to the whole brain.

4.3. Cycle strength and cognitive abilities

Another main concept of PH‐based functional connectivity in the current study is “cycles.” The cycle provides additional information to the backbone of information flow, while MST only considers a tree with no loops. In other words, the backbone strength represents the overall strength of the information flow, but the pattern of strength omitted in the process can be reinforced from the birth weight set of cycles, . As shown in the example of Figure 3, even with a similar backbone strength, low cycle strength is interpreted as information flow patterns with high strength are transmitted through the backbone rather than additional cycles. In the current study, we found that fluid reasoning and vocabulary were negatively correlated to cycle strength (Table 3). This suggests that cognitive ability increases as the flow of important information (here, strong connectivity) tend to go through the backbone structure without being dispersed into several cycles.

4.4. Possible limitations of cycle measures

Our study offers novel insights into functional connectivity, utilizing the PH method to examine the weight strength associated with the complexity of brain networks during the brain integration process. Our results demonstrate that the average functional connectivity of cycles involving all brain regions provides valuable information on brain network complexity. Rather than examining the existing topological structure, we focused on the distribution of functional connectivity involved in brain integration and its complexity. To achieve this, we focused on the average and range of edge weights in the last set of edges added during the filtration process instead of topological features.

We acknowledge that measures that illustrate the topological status of cycle structures may offer additional information to capture the full information of cycles and their association with cognition. To address this concern, we explored cycle measures that directly represent the complexity of network structure. Specifically, we considered the size of cliques, which are groups of nodes in a graph where each node is directly connected to every other node in the group. Large cliques indicate highly interconnected regions or communities that can contribute to the overall complexity of the network, potentially indicating important functional or structural modules within the network. The average and median sizes of cliques were also calculated to better understand the complexity of brain network structure in addition to functional connectivity. While none of the associations between cognitive abilities and clique size were significant or survived after multiple comparisons correction (Table 4), future studies may explore other cycle measures that can reveal additional information about the structure and function of brain networks.

TABLE 4.

Linear regression between cognitive performances and size of cliques when all brain regions are connected.

| Cognitive performance | Clique size | Standardized correlation coefficients [95% CI] | p‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluid reasoning | Mean clique size | 0.044 [−0.072, 0.160] | .456 |

| Fluid reasoning | Median clique size | 0.029 [−0.087, 0.145] | .621 |

| Episodic memory | Mean clique size | −0.009 [−0.130, 0.112] | .881 |

| Episodic memory | Median clique size | −0.013 [−0.134, 0.108] | .834 |

| Vocabulary | Mean clique size | 0.067 [−0.051, 0.184] | .266 |

| Vocabulary | Median clique size | 0.059 [−0.059, 0.176] | .327 |

| Processing speed | Mean clique size | 0.108 [−0.011, 0.227] + | .076 |

| Processing speed | Median clique size | 0.111 [−0.008, 0.230] + | .069 |

Note: All regressions were controlled for age, gender, education, and mean cortical thickness.

p < .100.

Furthermore, we did not include cycles born after all nodes are connected, which are captured in the last set of edges added (), in our analysis. We focused on cycles that emerged during the growth of the simplicial complex and before all nodes were connected, as they provide valuable information about the integration of brain regions. Our decision to exclude cycles born after all nodes are connected was motivated by the fact that these cycles do not provide any additional information about the integration process once all nodes are connected. Additionally, edges added after all nodes are connected tend to have relatively small weights, which could be due to noise or spurious connections (Bordier et al., 2017; Serrano et al., 2009). Therefore, including these edges in our analysis may not provide useful information about the brain's functional organization. However, it is worth noting that further investigations may be necessary to determine whether these edges contain any valuable information that may have been missed by excluding them from our analysis.

4.5. PH‐based functional connectivity versus Betti curve features

Unlike general PH on point cloud data, which is interested in how many significant hole structures appear from data points sampled from the underlying shape of the data, the topological features appearing in the brain connectivity describe a way of connecting predefined nodes (i.e., brain regions). Thus, to effectively describe these characteristics of topological features of brain connectivity, the Betti curve, which tracks the number of topological features (e.g., connected components or loops) at each filtration value, has been considered one of the summarized representations of the PH of brain connectivity. Many applications of the Betti curve to brain connectivity have used measures describing the shape of the Betti curve such as the area under the Betti curve and the slope of the Betti curve (Cassidy et al., 2015; Choe et al., 2018; Gracia‐Tabuenca et al., 2020; Kuang et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2012; Stolz et al., 2021). These summaries of Betti curves quantify the shape characteristics of Betti curves rather than directly summarizing the dynamic topological characteristics of brain connection structures. For example, while the slope of the dimension 0 Betti curve has been interpreted as the “speed” of brain connectivity, the concept of “speed” here is very abstract and derivative. “Speed” here mathematically means the change in the number of connected components as the filtration value (i.e., Pearson correlation) changes. In fact, the topology referred to in graph theory‐based analysis focuses on how nodes are arranged or interconnected, whereas the topology referred to in PH (hence, Betti curves) refers to the number of holes in the space. In addition, unlike graph theory‐based analysis that quantifies the network topology varying with filtration (or thresholding), the Betti curve is constructed in a way that captures the filtration values where birth and death occur in each Betti number. Therefore, the interpretation of the Betti curve is more natural when focusing on the filtration values according to each fixed Betti number.

In the current study, we applied PH with graph filtration to decompose the weight set into dimension 0 death weight set and dimension 1 birth weight set. In fact, the application of graph filtration can make the individual Betti curve only depend on the edge weights when the connected component dies and the cycle is born. Thus, instead of using the Betti curve, we considered the weight sets of edges involving the death of each connected component and the birth of each cycle. The weights included in are the same as the death filtration observed for each dimension 0 Betti number. By doing so, we sought to extend the interpretation of PH from simply describing the speed of brain connectivity to explaining the cost distribution of the economic backbone structure (i.e., MST) and cycles adding information to MST of the whole brain.

Moreover, using the defined weight set, the dimension 0 Betti curve can be defined as follows:

where is an indicator function, and is dimension Betti curve. Also, the standardized Betti curves are defined as:

where is the number of nodes, is the standardized dimension Betti curve. Then, the area under the standardized Betti curve is negatively related to the mean of (= ), which is backbone strength in this article, as follows:

Therefore, the small value of the area under the curve (AUC) of dimension 0 Betti curve can be interpreted as the high average strength of the backbone structure (i.e., the overall strength of information flow in the brain network is high).

As in recent studies related to the application of PH to the brain network, the summary values (e.g., AUC) of the Betti curve considering only dimension 0 consider limited edge weight information related to the backbone, so it may not be sufficient to explain the pattern of functional connectivity in some cases. At least in this study, the overall strength of brain information flow, for example, the backbone strength (or AUC of dimension 0 Betti curve), was insufficient to explain cognitive ability. Instead, additional information on cycle structure in the current study suggested that cognitive ability is related to patterns of brain information flow.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In sum, in this study, we presented a novel measure to quantify an important aspect of functional connectivity which characterizes the pattern of whole‐brain integration by using PH. We applied the new measures to study the relationship between the pattern of resting‐state functional connectivity and cognitive ability. Our approach offers a novel insight into functional connectivity during integrative processing, and PH‐based functional connectivity measures explain cognitive aging, while segregation‐focused connectivity measures or graph theory‐based network topology does not.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Hyunnam Ryu and Seonjoo Lee designed research; Hyunnam Ryu, Seonjoo Lee, Christian Habeck, and Yaakov Stern performed research; Hyunnam Ryu analyzed data; Hyunnam Ryu wrote the paper; and Seonjoo Lee, Christian Habeck, and Yaakov Stern provided detailed feedback and suggestions on the draft version of the paper.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have declared no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by three grants from the National Institute on Aging (R01AG026158, principal investigator: Yaakov Stern; R01AG038465, principal investigator: Yaakov Stern; R01AG062578, principal investigator: Seonjoo Lee).

Ryu, H. , Habeck, C. , Stern, Y. , & Lee, S. (2023). Persistent homology‐based functional connectivity and its association with cognitive ability: Life‐span study. Human Brain Mapping, 44(9), 3669–3683. 10.1002/hbm.26304

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

R‐package “PHfconn” (available at https://github.com/hyunnamryu/PHfconn) contains source code files to compute the persistent homology‐based functional connectivity. The package also contains the example data and code files for statistical evaluations and visualizations presented in the article. Data are available upon reasonable request and are subject to a formal data use agreement.

REFERENCES

- Bassett, D. S. , & Sporns, O. (2017). Network neuroscience. Nature Neuroscience, 20(3), 353–364. 10.1038/nn.4502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolero, M. A. , Yeo, B. T. T. , & D'Esposito, M. (2015). The modular and integrative functional architecture of the human brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(49), E6798–E6807. 10.1073/pnas.1510619112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birn, R. M. , Diamond, J. B. , Smith, M. A. , & Bandettini, P. A. (2006). Separating respiratory‐variation‐related fluctuations from neuronal‐activity‐related fluctuations in fMRI. NeuroImage, 31(4), 1536–1548. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomsma, N. , de Rooy, B. , Gerritse, F. , van der Spek, R. , Tewarie, P. , Hillebrand, A. , Otte, W. M. , Stam, C. J. , & van Dellen, E. (2022). Minimum spanning tree analysis of brain networks: A systematic review of network size effects, sensitivity for neuropsychiatric pathology, and disorder specificity. Network Neuroscience, 6(2), 301–319. 10.1162/netn_a_00245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boersma, M. , Smit, D. J. , Boomsma, D. I. , de Geus, E. J. , Delemarre‐Van de Waal, H. A. , & Stam, C. J. (2013). Growing trees in child brains: Graph theoretical analysis of electroencephalography‐derived minimum spanning tree in 5‐ and 7‐year‐old children reflects brain maturation. Brain Connectivity, 3(1), 50–60. 10.1089/brain.2012.0106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissonnat, J.‐D. , Chazal, F. , & Yvinec, M. (2018). Geometric and topological inference. Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/9781108297806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bordier, C., Nicolini, C., & Bifone, A . (2017). Graph Analysis and Modularity of Brain Functional Connectivity Networks: Searching for the Optimal Threshold. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 11, 441. 10.3389/fnins.2017.00441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschke, H. , & Fuld, P. A. (2011). Evaluating storage, retention and retrieval in disordered memory and learning. Neurology, 76(20), 1725. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000398283.10171.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, R. , Hao, Y. , Wang, X. , Gao, Y. , Shi, H. , Huo, S. , Wang, B. , Guo, H. , & Xiang, J. (2020). EEG functional connectivity underlying emotional valance and arousal using minimum spanning trees. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14, 355. 10.3389/fnins.2020.00355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carp, J. (2013). Optimizing the order of operations for movement scrubbing: Comment on Power et al. NeuroImage, 76, 436–438. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, B. , Rae, C. , & Solo, V. (2015). Brain activity: Conditional dissimilarity and persistent homology. In Proceedings of the IEEE 12th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), pp. 1356–1359. 10.1109/ISBI.2015.7164127 [DOI]

- Chan, M. Y. , Park, D. C. , Savalia, N. K. , Petersen, S. E. , & Wig, G. S. (2014). Decreased segregation of brain systems across the healthy adult lifespan. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(46), E4997–E5006. 10.1073/pnas.1415122111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazal, F. , & Michel, B. (2021). An introduction to topological data analysis: Fundamental and practical aspects for data scientists. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 4, 667963. 10.3389/frai.2021.667963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe, M. K. , Lim, M. , Kim, J. S. , Lee, D. S. , & Chung, C. K. (2018). Disrupted resting state network of fibromyalgia in theta frequency. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 2064. 10.1038/s41598-017-18999-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. R. , & D'Esposito, M. (2016). The segregation and integration of distinct brain networks and their relationship to cognition. The Journal of Neuroscience, 36(48), 12083–12094. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2965-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole, M. W. , Bassett, D. S. , Power, J. D. , Braver, T. S. , & Petersen, S. E. (2014). Intrinsic and task‐evoked network architectures of the human brain. Neuron, 83(1), 238–251. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghrist, R. (2008). Barcodes: The persistent topology of data. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 45(1), 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, C. J. (1978). A manual for the clinical and experimental use of the Stroop color and word test. Stoelting. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia‐Tabuenca, Z. , Díaz‐Patiño, J. C. , Arelio, I. , & Alcauter, S. (2020). Topological data analysis reveals robust alterations in the whole‐brain and frontal lobe functional connectomes in attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. ENeuro, 7(3), ENEURO.0543‐19.2020. 10.1523/ENEURO.0543-19.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober, E. , & Sliwinski, M. (1991). Development and validation of a model for estimating premorbid verbal intelligence in the elderly. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 13(6), 933–949. 10.1080/01688639108405109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, S. , Xia, C. H. , Ciric, R. , Moore, T. M. , Gur, R. C. , Gur, R. E. , Satterthwaite, T. D. , & Bassett, D. S. (2020). Unifying the notions of modularity and core‐periphery structure in functional brain networks during youth. Cerebral Cortex, 30(3), 1087–1102. 10.1093/cercor/bhz150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher, A. (2002). Algebraic topology. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hausman, H. K. , O'Shea, A. , Kraft, J. N. , Boutzoukas, E. M. , Evangelista, N. D. , Van Etten, E. J. , Bharadwaj, P. K. , Smith, S. G. , Porges, E. , Hishaw, G. A. , Wu, S. , DeKosky, S. , Alexander, G. E. , Marsiske, M. , Cohen, R. , & Woods, A. J. (2020). The role of resting‐state network functional connectivity in cognitive aging. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 12, 177. 10.3389/fnagi.2020.00177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson, M. , Beckmann, C. F. , Behrens, T. E. J. , Woolrich, M. W. , & Smith, S. M. (2012). FSL. NeuroImage, 62(2), 782–790. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasawinah, S. , Chuang, Y.‐F. , Caffo, B. , Erickson, K. I. , Kramer, A. F. , & Carlson, M. C. (2017). The association between functional connectivity and cognition in older adults. Journal of Systems and Integrative Neuroscience, 3(3), 1–10. 10.15761/JSIN.1000164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kruskal, J. B. (1956). On the shortest spanning subtree of a graph and the traveling salesman problem. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, 7(1), 48–50. 10.2307/2033241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, L. , Han, X. , Chen, K. , Caselli, R. J. , Reiman, E. M. , & Wang, Y. (2019). A concise and persistent feature to study brain resting‐state network dynamics: Findings from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Human Brain Mapping, 40(4), 1062–1081. 10.1002/hbm.24383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H. , Kang, H. , Chung, M. K. , Kim, B. N. , & Lee, D. S. (2012). Persistent brain network homology from the perspective of dendrogram. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 31(12), 2267–2277. 10.1109/TMI.2012.2219590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, D. , Xia, S. , Zhang, X. , & Zhang, W. (2021). Analysis of brain functional connectivity neural circuits in children with autism based on persistent homology. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 15, 745671. 10.3389/fnhum.2021.745671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medaglia, J. D. , Lynall, M. E. , & Bassett, D. S. (2015). Cognitive network neuroscience. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 27(8), 1471–1491. 10.1162/jocn_a_00810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opsahl, T., Agneessens, F., & Skvoretz, J. (2010). Node centrality in weighted networks: Generalizing degree and shortest paths. Social Networks, 32(3), 245–251. 10.1016/j.socnet.2010.03.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Power, J. D. , Barnes, K. A. , Snyder, A. Z. , Schlaggar, B. L. , & Petersen, S. E. (2012). Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. NeuroImage, 59(3), 2142–2154. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power, J. D. , Cohen, A. L. , Nelson, S. M. , Wig, G. S. , Barnes, K. A. , Church, J. A. , Vogel, A. C. , Laumann, T. O. , Miezin, F. M. , Schlaggar, B. L. , & Petersen, S. E. (2011). Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron, 72(4), 665–678. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K. J. , & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. 10.3758/BF03206553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razlighi, Q. R. , Habeck, C. , Steffener, J. , Gazes, Y. , Zahodne, L. B. , Mackay‐Brandt, A. , & Stern, Y. (2014). Unilateral disruptions in the default network with aging in native space. Brain and Behavior: A Cognitive Neuroscience Perspective, 4(2), 143–157. 10.1002/brb3.202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinov, M. , & Sporns, O. (2010). Complex network measures of brain connectivity: Uses and interpretations. NeuroImage, 52(3), 1059–1069. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saba, V. , Premi, E. , Cristillo, V. , Gazzina, S. , Palluzzi, F. , Zanetti, O. , Gasparotti, R. , Padovani, A. , Borroni, B. , & Grassi, M. (2019). Brain connectivity and information‐flow breakdown revealed by a minimum spanning tree‐based analysis of MRI data in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 211. 10.3389/fnins.2019.00211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saggar, M. , Shine, J. M. , Liégeois, R. , Dosenbach, N. U. F. , & Fair, D. (2022). Precision dynamical mapping using topological data analysis reveals a hub‐like transition state at rest. Nature Communications, 13(1), 1. 10.1038/s41467-022-32381-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saggar, M. , Sporns, O. , Gonzalez‐Castillo, J. , Bandettini, P. A. , Carlsson, G. , Glover, G. , & Reiss, A. L. (2018). Towards a new approach to reveal dynamical organization of the brain using topological data analysis. Nature Communications, 9(1), 1. 10.1038/s41467-018-03664-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse, T. A. , Habeck, C. , Razlighi, Q. , Barulli, D. , Gazes, Y. , & Stern, Y. (2015). Breadth and age‐dependency of relations between cortical thickness and cognition. Neurobiology of Aging, 36(11), 3020–3028. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, M. Á. , Boguñá, M. , & Vespignani, A. (2009). Extracting the multiscale backbone of complex weighted networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(16), 6483–6488. 10.1073/pnas.0808904106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shine, J. M., Bissett, P. G., Bell, P. T., Koyejo, O., Balsters, J. H., Gorgolewski, K. J., Moodie, C. A., & Poldrack, R. A . (2016). The Dynamics of Functional Brain Networks: Integrated Network States during Cognitive Task Performance. Neuron, 92(2), 544–554. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shnier, D. , Voineagu, M. A. , & Voineagu, I. (2019). Persistent homology analysis of brain transcriptome data in autism. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 16(158), 20190531. 10.1098/rsif.2019.0531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sizemore, A. E. , Giusti, C. , & Bassett, D. S. (2017). Classification of weighted networks through mesoscale homological features. Journal of Complex Networks, 5(2), 245–273. 10.1093/comnet/cnw013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sporns, O. (2013). Network attributes for segregation and integration in the human brain. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 23(2), 162–171. 10.1016/j.conb.2012.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam, C. J. , Tewarie, P. , Van Dellen, E. , van Straaten, E. C. W. , Hillebrand, A. , & Van Mieghem, P. (2014). The trees and the forest: Characterization of complex brain networks with minimum spanning trees. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 92(3), 129–138. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Y. (2009). Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia, 47(10), 2015–2028. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Y. , Gazes, Y. , Razlighi, Q. , Steffener, J. , & Habeck, C. (2018). A task‐invariant cognitive reserve network. NeuroImage, 178, 36–45. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.05.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Y. , Habeck, C. , Steffener, J. , Barulli, D. , Gazes, Y. , Razlighi, Q. , Shaked, D. , & Salthouse, T. (2014). The reference ability neural network study: Motivation, design, and initial feasibility analyses. NeuroImage, 103, 139–151. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.09.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Y. , Varangis, E. , & Habeck, C. (2021). A framework for identification of a resting‐bold connectome associated with cognitive reserve. NeuroImage, 232, 117875. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.117875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolz, B. J. , Emerson, T. , Nahkuri, S. , Porter, M. A. , & Harrington, H. A. (2021). Topological data analysis of task‐based fMRI data from experiments on schizophrenia. Journal of Physics: Complexity, 2(3), 035006. 10.1088/2632-072X/abb4c6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tewarie, P. , Hillebrand, A. , Schoonheim, M. M. , van Dijk, B. W. , Geurts, J. J. G. , Barkhof, F. , Polman, C. H. , & Stam, C. J. (2014). Functional brain network analysis using minimum spanning trees in multiple sclerosis: An MEG source‐space study. NeuroImage, 88, 308–318. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dellen, E. , Sommer, I. E. , Bohlken, M. M. , Tewarie, P. , Draaisma, L. , Zalesky, A. , Di Biase, M. , Brown, J. A. , Douw, L. , Otte, W. M. , Mandl, R. C. W. , & Stam, C. J. (2018). Minimum spanning tree analysis of the human connectome. Human Brain Mapping, 39(6), 2455–2471. 10.1002/hbm.24014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel, M. P. , Kahn, R. S. , Goñi, J. , & Sporns, O. (2012). High‐cost, high‐capacity backbone for global brain communication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(28), 11372–11377. 10.1073/pnas.1203593109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel, M. P. , & Sporns, O. (2013). Network hubs in the human brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17(12), 683–696. 10.1016/j.tics.2013.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Mieghem, P. , & Magdalena, S. M. (2005). Phase transition in the link weight structure of networks. Physical Review. E, Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics, 72(5 Pt 2), 056138. 10.1103/PhysRevE.72.056138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wijk, B. C. M. , Stam, C. J. , & Daffertshofer, A. (2010). Comparing brain networks of different size and connectivity density using graph theory. PLoS One, 5(10), e13701. 10.1371/journal.pone.0013701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varangis, E. , Habeck, C. G. , Razlighi, Q. R. , & Stern, Y. (2019). The effect of aging on resting state connectivity of predefined networks in the brain. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 11, 234. 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varangis, E. , Qi, W. , Stern, Y. , & Lee, S. (2022). The role of neural flexibility in cognitive aging. NeuroImage, 247, 118784. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. , Hernandez, J. M. , & Van Mieghem, P. (2008). Betweenness centrality in a weighted network. Physical Review E, 77(4), 046105. 10.1103/PhysRevE.77.046105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. (1981). The psychometric tradition: Developing the Wechsler adult intelligence scale. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 6, 82–85. 10.1016/0361-476X(81)90035-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M. , Gouw, A. A. , Hillebrand, A. , Tijms, B. M. , Stam, C. J. , van Straaten, E. C. W. , & Pijnenburg, Y. A. L. (2016). Different functional connectivity and network topology in behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease: An EEG study. Neurobiology of Aging, 42, 150–162. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zomorodian, A. , & Carlsson, G. (2005). Computing persistent homology. Discrete and Computational Geometry, 33(2), 249–274. 10.1007/s00454-004-1146-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

R‐package “PHfconn” (available at https://github.com/hyunnamryu/PHfconn) contains source code files to compute the persistent homology‐based functional connectivity. The package also contains the example data and code files for statistical evaluations and visualizations presented in the article. Data are available upon reasonable request and are subject to a formal data use agreement.