Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS:

Recommended surveillance intervals after complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia (CE-IM) after endoscopic eradication therapy (EET) are largely not evidence-based. Using recurrence rates in a multicenter international Barrett’s esophagus (BE) CE-IM cohort, we aimed to generate optimal intervals for surveillance.

METHODS:

Patients with dysplastic BE undergoing EET and achieving CE-IM from prospectively maintained databases at 5 tertiary-care centers in the United States and the United Kingdom were included. The cumulative incidence of recurrence was estimated, accounting for the unknown date of actual recurrence that lies between the dates of current and previous endoscopy. This cumulative incidence of recurrence subsequently was used to estimate the proportion of patients with undetected recurrence for various surveillance intervals over 5 years. Intervals were selected that minimized recurrences remaining undetected for more than 6 months. Actual patterns of post-CE-lM follow-up evaluation are described.

RESULTS:

A total of 498 patients (with baseline low-grade dysplasia, 115 patients; high-grade dysplasia [HGD], 288 patients; and intramucosal adenocarcinoma [IMCa], 95 patients) were included. Any recurrence occurred in 27.1% and dysplastic recurrence occurred in 8.4% over a median of 2.6 years of follow-up evaluation. For pre-ablation HGD/IMCa, intervals of 6, 12, 18, and 24 months, and then annually, resulted in no patients with dysplastic recurrence undetected for more than 6 months, comparable with current guideline recommendations despite a 33% reduction in the number of surveillance endoscopies. For pre-ablation low-grade dysplasia, intervals of 1, 2, and 4 years balanced endoscopic burden and undetected recurrence risk.

CONCLUSIONS:

Lengthening post-CE-IM surveillance intervals would reduce the endoscopic burden after CE-IM with comparable rates of recurrent HGD/IMCa. Future guidelines should consider reduced surveillance frequency.

Keywords: Esophagus, Barrett’s Esophagus, Adenocarcinoma, Surveillance

Endoscopic eradication therapy (EET) is recommended by all society guidelines for the treatment of Barrett’s esophagus (BE) with dysplasia or intramucosal adenocarcinoma (IMCa).1–3 After complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia (CE-IM), patients undergo endoscopic surveillance at intervals largely based on expert opinion.1,3–5 These intervals do not account for the reduction in cancer risk conferred by EET,6 resulting in a substantial number of procedures, particularly in the 2 years after CE-IM.

The timeline of recurrence after CE-IM varies across studies. Recurrence incidence is reported as higher in the first year,7 second year,8 and remaining constant over time.9 Furthermore, although recurrent IM after EET is not uncommon (8%–10% per year10), most recurrences are nondysplastic.9 The rate of dysplastic recurrence is low at 2% per year.10–12 Thus, evidence-based guidelines for surveillance after CE-IM are essential.

A single prior study used national registry data and proposed lengthening of surveillance intervals.13 However, this study was limited by many nondysplastic BE (NDBE) patients undergoing ablation, lacked granularity regarding actual timing of patient follow-up evaluation, and did not account for the delay between time of recurrence and its detection.

We aimed to evaluate the cumulative incidence of recurrence after CE-IM in a large cohort of patients treated with EET for BE-associated neoplasia, characterize their patterns of follow-up evaluation, and estimate the rate and duration of undetected recurrence for various surveillance paradigms, aimed at guiding the selection of optimal surveillance intervals.

Methods

Patient Selection and Data Collection

Adult patients with BE-low-grade dysplasia (LGD), high-grade dysplasia (HGD), or IMCa undergoing EET and achieving CE-IM between March 2004 and May 2017 were identified from prospectively maintained databases at 5 tertiary-referral academic centers with expertise in the management of BE. Three were located in the United States (Mayo Clinics in Minnesota, Arizona, and Florida) and 2 in the United Kingdom (Nottingham and Cambridge University). All diagnoses of dysplasia or IMCa were confirmed by expert gastrointestinal pathologists. Patients without endoscopic follow-up evaluation, pregnant patients, and those with esophageal varices or a history of advanced esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) were excluded.

We previously published a study examining the recurrence timeline and location using this database.9 In the present study, only patients with HGD/IMCa or LGD at baseline were included. Clinical and demographic data were abstracted manually. When follow-up evaluation occurred elsewhere, records were reviewed and included in the analysis.

We also endeavored to understand patterns of interval follow-up evaluation. To reduce practice-related variability, we limited this analysis to the US sites that function as a single integrated health care system. Results of each individual endoscopy and corresponding histologic findings after CE-IM were recorded to characterize patterns of post-EET follow-up evaluation. The UK data were used for all analyses in the study aside from this follow-up timing analysis.

Endoscopic Therapy and Surveillance

Endoscopists with expertise in BE-associated neoplasia performed all procedures. Using high-definition white-light and narrow-band imaging, any visible abnormality was resected. Radiofrequency ablation then was administered every 3 months until CE-IM was achieved. Patients were maintained on twice-daily proton pump inhibitor therapy during treatment.

After CE-IM, endoscopic surveillance was recommended for LGD at 6 months, 12 months, and yearly thereafter. For HGD/IMCa, surveillance was recommended at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months, and yearly thereafter. During surveillance, any visible abnormality was sampled separately. Biopsy specimens also were obtained in 4 quadrants every 1 to 2 cm from the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) and tubular esophagus encompassing the pretreatment BE segment.

Definitions and Outcomes

CE-IM was defined as 2 endoscopic sessions at least 3 months apart during which no visible or histologic evidence of BE was found on biopsy specimens of the GEJ and tubular esophagus. Nondysplastic recurrence included the finding of IM in biopsy specimens of the GEJ. Dysplastic recurrence encompassed any recurrence with LCD, HGD, or IMCa. There were 3 separate clinical end points: (1) any recurrence, (2) dysplastic recurrence, and (3) cancer recurrence.

Statistical Analysis

A detailed description of the statistical analyses is provided in the Supplementary Methods. All analyses were performed separately according to baseline histology (LGD or HGD/IMCa). To estimate the cumulative incidences of any recurrence, dysplastic recurrence, and cancer recurrence for 5 years after CE-IM, we first estimated crude cumulative incidences using the Kaplan–Meier method. Censoring occurred on the date of the last esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for patients without recurrence and recurrence was considered to occur on the date of the EGD at which it was detected. This results in cumulative incidence estimates that are biased too low.

We used the following strategy to address this: Those with any recurrence were each included in N different instances in a modified data set, where N equals the difference between the date of the EGD at which recurrence was detected (recurrence EGD) and the date of the previous EGD; each N instance was given a weight equal to f divided by N. For each instance, times to recurrence after CE-IM were assigned uniformly distributed values across the range of dates between the previous EGD to the recurrence EGD. This directly accounted for the unknown true date of recurrence by allowing for recurrence to occur on each possible intervening date, all of which were weighted equally. We then re-estimated cumulative recurrence incidence via the Kaplan-Meier method using the modified data set, accounting for the correlation between the N instances for each patient, and assuming right-censoring. We opted for the current approach over the traditional Kaplan-Meier method with interval censoring because it directly accounts for the possibility of recurrence on each day. There was strong agreement in cumulative incidence estimates for our method and traditional Kaplan-Meier estimates using interval censoring (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2).

The cumulative incidences of dysplastic and cancer recurrence then were estimated for baseline HGD/IMCa patients. Censoring occurred at either of the following dates: last EGD (for patients without recurrence), nondysplastic recurrence (when analyzing dysplastic recurrence) This censoring scheme was used because recurrences, including NDBE, generally were treated. Because treatment lowers recurrence risk, failure to censor these NDBE recurrences in the dysplastic recurrence analysis would result in cumulative incidence estimates that arc biased too low. Thus, analyses of dysplastic and cancer recurrence assumed that the risk of dysplastic/cancer recurrence was independent of nondysplastic recurrence.

Metrics for comparison of Surveillance Scenarios

We focused on the initial 5 years after CE-IM for LGD patients and on the initial 2 years after CE-IM for FIGD/IMCa patients because this is the period of most frequent surveillance. The 2 primary metrics were the proportion of patients with a wait of more than 3 or more than 6 months between the recurrence date and the date of endoscopy at which recurrence was detected. A range of plausible surveillance scenarios were considered, including the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines, and those proposed by Cotton et al.7,13

The 2 primary metrics were calculated as follows for each surveillance scenario based on the cumulative incidence estimates for any recurrence, dysplastic recurrence, or cancer recurrence. For each targeted follow-up EGD time point, the cumulative incidence of the given outcome (any recurrence, dysplastic recurrence, or cancer recurrence) was estimated at both the prior targeted follow-up EGD time point (eg, CE-IM, 6 mo, 1 y) as well as the targeted time point minus either 3 months or 6 months. The latter estimate subsequently was subtracted from the former, yielding a separate difference value for each targeted follow-up EGD time point. These differences then were summed to calculate the proportion of patients with a wait of more than 3 months (or >6 months) between the date of recurrence and the date of recurrence EGD under the given surveillance scenario. In baseline LGD patients, for surveillance scenarios that did not include a 5-year follow-up time point, an additional difference value was included as the difference in cumulative incidences of recurrence at the 5-year time point and the final follow-up time point. A visual illustration of this calculation is shown in Supplementary Figure 3.

Results

Patient Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes

A total of 498 patients (420 US patients, 78 UK patients) were included. Their baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. After a median follow-up period of 2.6 years (range, 0.2–10.6 y), recurrence was observed in 135 patients (27.1%), of whom 42 (8.4%) had a dysplastic recurrence. The location and timing of recurrence in this population have been reported previously.9

Table 1.

Patient Demographics, Clinical Characteristics, and Outcomes

| Characteristics | LGD | HGD | IMCa |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| N | 115 | 288 | 95 |

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 67 (62–72) | 68 (61–74) | 68 (62–74) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 96 (83.5) | 242 (84.0) | 87 (91.6) |

| Length of BE, cm, median (IQR) | 5 (3–7) | 4 (2–6) | 3(1–6) |

| Follow-up period, mo, median (IQR) | 29.2 (13.8–52.1) | 23.7 (12.0–37.8) | 21.9 (12.2–42.1) |

| Recurrence | |||

| Nondysplastic | 18 | 56 | 19 |

| LGD | 0 | 15 | 3 |

| HGD | 0 | 8 | 2 |

| Cancer | 3 | 7 | 4 |

BE, Barrett’s esophagus; HGD, high-grade dysplasia; IMCa, intramucosal adenocarcinoma; IQR, interquartile range; LGD, low-grade dysplasia.

Recurrence Incidence and Histology

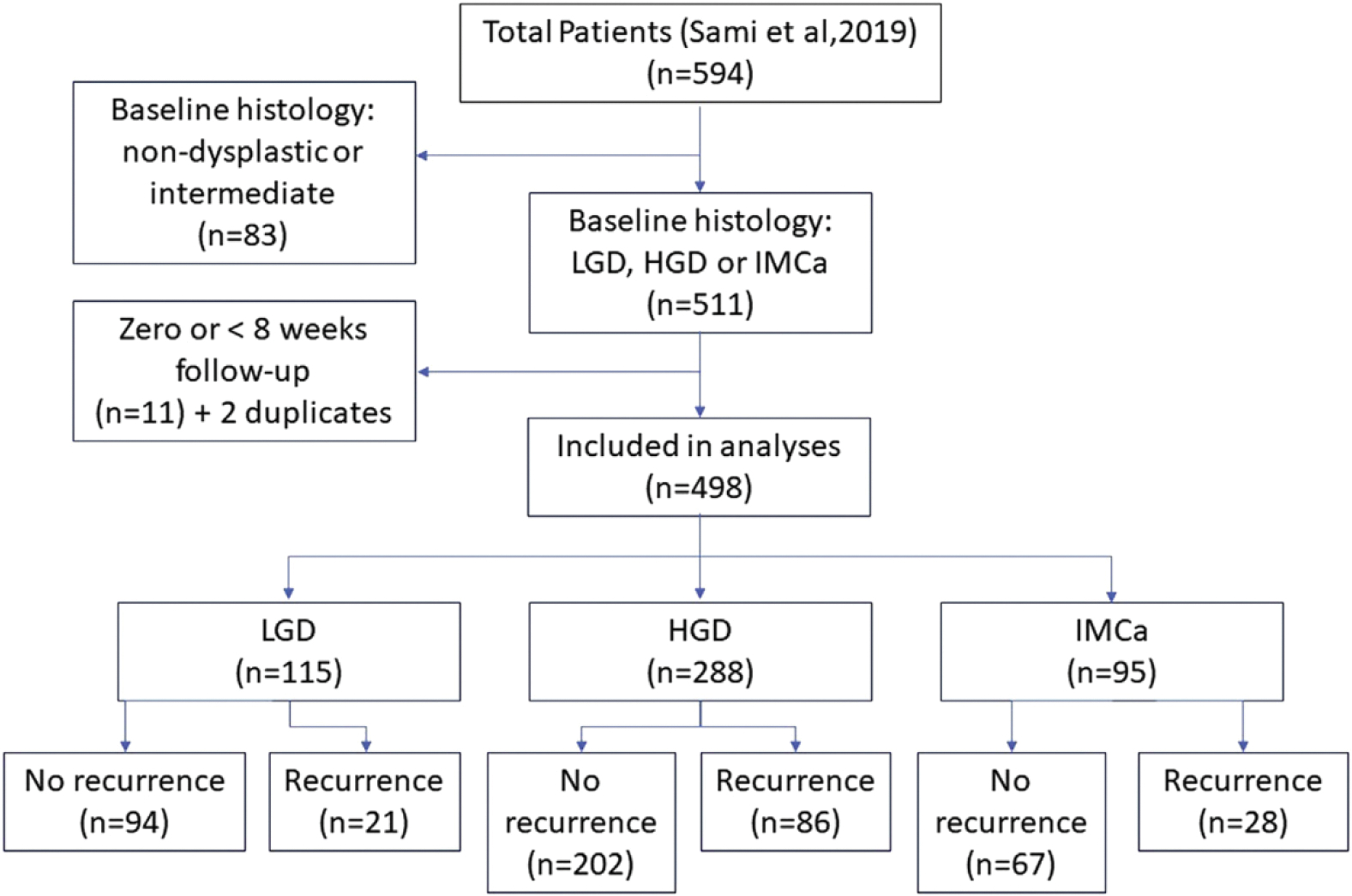

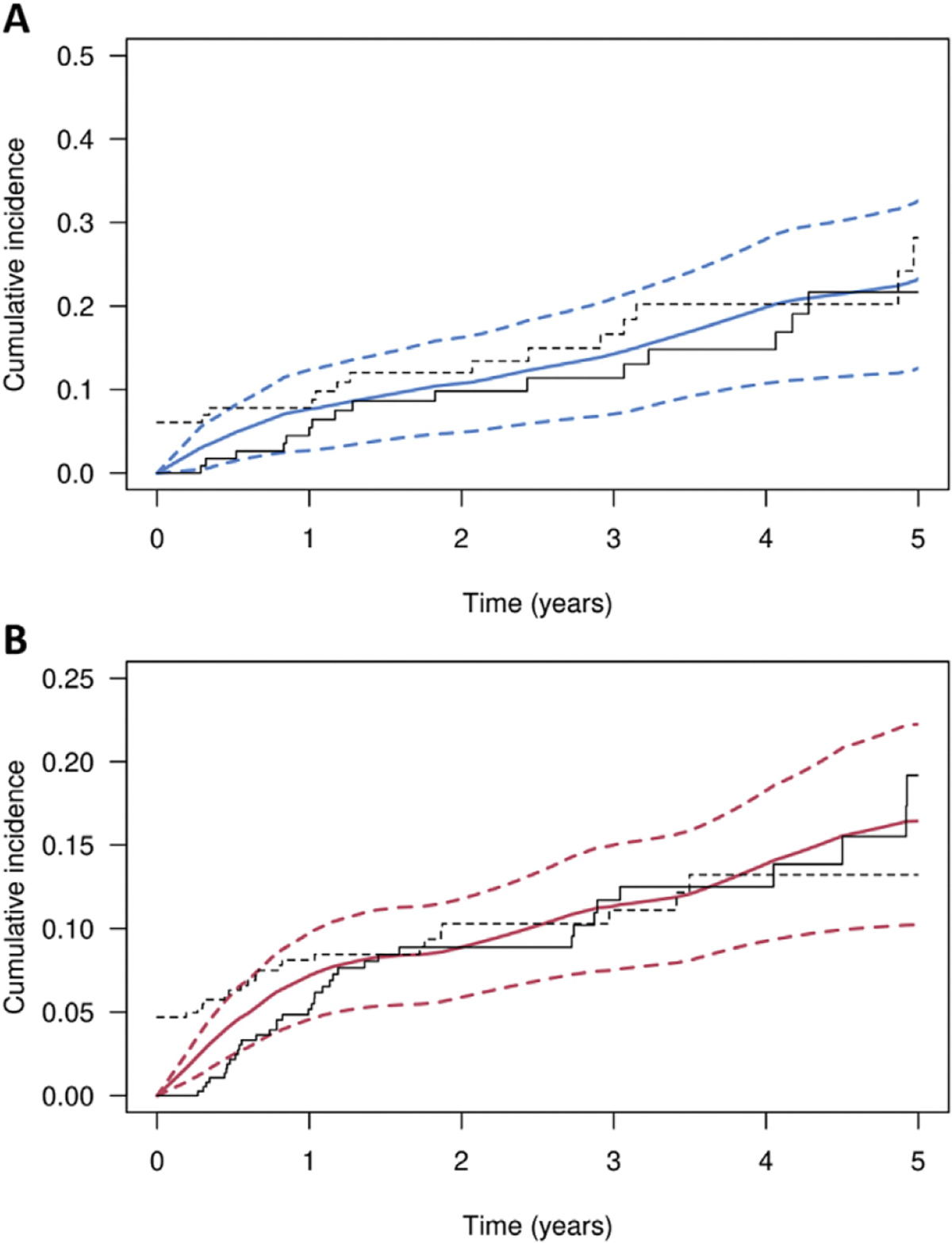

A summary of clinical outcomes is presented in Figure 1. For the 383 patients with baseline HGD/IMCa, recurrence occurred in 114 (29.7%), of which 39 (10.2%) were dyspiastic (Table 1), Cumulative incidence estimates for all recurrences and dyspiastic recurrences after CE-IM are shown in Figure 2 and Table 2 for the baseline HGD/IMCa subgroup. The cumulative incidence of any recurrence was 25.3% (95% Cl, 21.1%–30.2%) at 2 years and 40.2% (9% Cl, 32.9%–46.8%) at 5 years. The cumulative incidence of dyspiastic recurrence (LGD or higher grade) was 8.9% (95% Cl, 5.9%–11.8%) at 2 years and 16.4% (10.2%–22.2%) at 5 years.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient outcomes. HGD, high-grade dysplasia; IMCa, intramucosal adenocarcinoma; LGD, low-grade dysplasia.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of recurrence for patients with low-grade dysplasia (LGD) or high-grade dysplasia (HGD)/intramucosal adenocarcinoma (IMCa) at baseline. Kaplan-Meier curves representing the cumulative incidence of recurrence after complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia in patients with (A) LGD or (B) HGD/IMCa at baseline before endoscopic eradication therapy. (A) Cumulative incidence of any recurrence (dysplastic or nondysplastic) is shown as a solid blue line, with blue dotted lines denoting 95% CIs. (B) cumulative incidence of dysplastic recurrence is shown as a solid red line, with red dotted lines denoting 95% Cl. Additional crude cumulative incidence estimates are shown, assuming recurrence occurred at the time of detection (solid black line) and during before the endoscopic session (dotted black line)

Table 2.

Cumulative Incidence of Any Recurrence (95% Cl) After CE-IM According to Baseline Histology

| Length of time after CE-IM | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Baseline histology | N | Person-years | Recurrence | 1 y | 2 y | 5 y | Rate/100 person-years |

|

| |||||||

| LGD | 115 | 359.6 | All | 7.7 (2.7–12.4) | 10.8 (4.9–16.3) | 23.3 (12.6–32.6) | 5.8 |

| Dysplastic | 0.9 (0.0–2.7) | 0.9 (0.0–2.7) | 3.1 (0.0–7.6) | 0.8 | |||

| EAC | 0.9 (0.0–2.7) | 0.9 (0.0–2.7) | 3.1 (0.0–7.6) | 0.8 | |||

| HGD/IMCa | 383 | 913.1 | All | 19.4 (15.5–23.2) | 25.8 (21.1–30.2) | 40.2 (32.9–46.8) | 12.5 |

| Dysplastic | 7.2 (4.6–9.7) | 8.9 (5.9–11.8) | 16.4 (10.2–22.2) | 4.3 | |||

| EAC | 4.2 (2.2–6.2) | 4.9 (2.6–7.0) | 9.5 (4.5–14.3) | 1.2 | |||

CE-IM, complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia; EAC, esophageal adenocarcinoma; HGD, high-grade dysplasia; IMCa, intramucosal adenocarcinoma; LGD, low-grade dysplasia.

In baseline LGD (N = 115), recurrence occurred in 21 (18.3%) patients, of which 18 (15.7%) were nondysplastic and only 3 (2.7%) were dyspiastic (Table 1), In these patients, the cumulative incidences of any recurrence is shown in Figure 2 and Table 2; the cumulative incidence of any recurrence was 10.8% (95% Cl, 4.9%–16.3%) at 2 years and 23.3% (95% Cl, 12.6%–32.6%) at 5 years.

Table 2 further describes the incidence of recurrence in relation to baseline pretreatment histology. In total, 14 patients developed EAC after successful endoscopic eradication, 10 of whom had either LGD or HGD before ablation. Eight of 14 (57.1%) recurrent EACs were IMCa, while the remaining 6 cases were more deeply invasive and required either chcmothcrapy/radiation, surgery, or a combination thereof. A single patient died as a consequence of recurrent EAC.

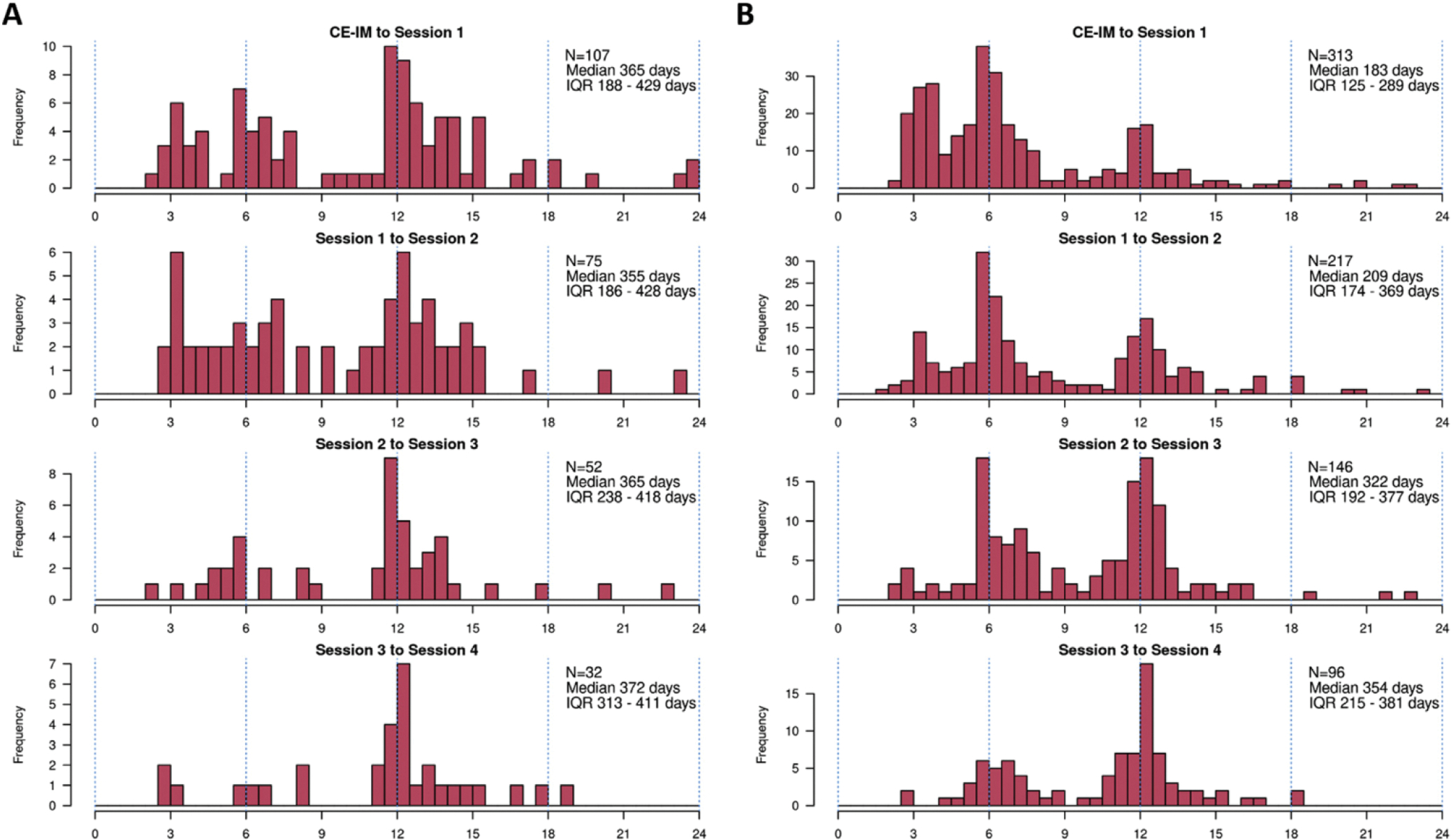

Intervals of Actual Follow-Up Evaluation

The specific dates of each surveillance endoscopy were tabulated for all US patients and frequency data are shown in Figure 3. These are shown as time between sessions rather than absolute time from CE-IM because subsequent surveillance recommendations would have been issued based on the actual date of endoscopy. The median time from CE-IM (defined as 2 consecutive endoscopies with no BE on histology) to first endoscopic surveillance was 365 days (range, 74–1111 d) for LGD and 183 days (range, 70–1000 d) in HGD/IMCa. The time frames between subsequent surveillance sessions varied widely, but most commonly occurred at either 6- or 12-month intervals.

Figure 3.

Actual follow-up intervals by visit after complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia (CE-IM). (A) Low-grade dysplasia at baseline. (B) High-grade dysplasia/intramucosal adenocarcinoma at baseline. IQR, interquartile range.

Assessment of Metrics for Comparison of Surveillance Scenarios

The 2 primary metric for comparison of surveillance scenarios were calculated based on cumulative incidence curves separately for LGD and HGD/IMCa patients (Table 3). Because of the small number of LGD patients experiencing dysplastic recurrence, it was not examined separately for this subgroup. For baseline LGD patients, metrics were calculated for a 5-year time frame of follow-up evaluation after CE-IM. For patients with baseline HGD/IMCa, all metrics were assessed only for the first 2 years of follow-up evaluation because this time frame is associated with the most intensive surveillance frequency.

Table 3.

Summary of Recurrence Metrics in Different Surveillance Paradigms

| Metric | 6 mo, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 y (ACG) | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 y | 3, 6 mo, 2, 4 y | 1, 2, 4 y | 1,3 y (Cotton) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| LGD pre-ablation | |||||

| Sessions over 5 years if no recurrence, | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Patients who have any recurrence that is not detected until >3 mo, % | 15.8 | 17.9 | 16.4 | 20.0 | 21.1 |

| Patients who have any recurrence that is not detected until >6 mo, % | 7.7 | 12.4 | 14.2 | 16.0 | 18.6 |

| HGD/IMCa pre-ablation | |||||

| Sessions patient will have >2 years if no recurrence, n | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Patients who have any recurrence that is not detected until >3 mo, % | 3.5 | 7.2 | 8.8 | 14.2 | 15.8 |

| Patients who have any recurrence that is not detected until >6 mo, % | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 3.9 |

| Patients who have dysplastic recurrence that is not detected until >3 mo, % | 0.9 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 4.7 | 5.1 |

| Patients who have dysplastic recurrence that is not detected until >6 mo, % | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 1.1 |

| Patients who have càncer recurrence that is not detected until >3 mo, % | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

| Patients who have càncer recurrence that is not detected until >6 mo, % | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

ACG, American College of Gastroenterology; HGD, high-grade dysplasia; IMCa, intramucosal adenocarcinoma; LGD, low-grade dysplasia.

Each surveillance paradigm shows a trade-off between the number of endoscopies and the duration of undetected recurrence. Based on an assessment of these parameters, for baseline HGD/IMCa we recommend a strategy of 6-, 12-, 18-, and 24-month surveillance after CE-IM, and annually thereafter. Although the strategy advocated by Cotton et al13 would result in fewer dysplastic recurrences undetected for more than 3 months, it would increase the proportion of recurrent HGD/EAC left undetected for more than 6 months. This proposed strategy would reduce the number of endoscopic surveillance sessions by 33% compared with those advocated by the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines. For LGD, we recommend a strategy of 1-, 2-, and 4-year surveillance in the first 5 years. Compared with the strategy suggested by Cotton et al,13 this would result in fewer dysplastic and cancer recurrences undetected for more than 6 months while still reducing the number of endoscopic surveillance sessions by 48% compared with current guidelines. In both groups, the limited number of patients and recurrence outcomes beyond 5 years did not allow for further extrapolation beyond this time frame.

Discussion

After successful EET for dysplastic BE, currently recommended endoscopic surveillance is frequent and dysplastic recurrence is uncommon, leading some to suggest intervals should be lengthened. In this study, we analyzed a large multicenter international cohort of CE- IM patients treated for dysplastic BE to generate recurrence estimates, model surveillance paradigms, and suggest optimal surveillance intervals. This study modeled the duration of undetected recurrence. We propose lengthening surveillance for HGD/IMCa after CE-IM to 6, 12, 18, and 24 months, and then annually, and for LGD we recommend a strategy of 1-, 2-, and 4-year surveillance in the first 5 years. These amended strategies would reduce the number of endoscopies by 33% to 48%, substantially reduce cost, and lead to comparable clinical outcomes. These findings have a direct and substantial impact on the management of BE patients successfully completing EET.

Current evidence to support lengthening of post-EET surveillance is limited to very few studies.13,14 The only prior study to explicitly examine surveillance intervals after CE-IM13 used registry data to build models and select the optimal surveillance paradigm. The investigators constructed a model to yield a 0.1% per-visit rate of invasive EAC (approximate risk of serious complication from a surveillance endoscopy), corresponding to a 2.9% neoplastic recurrence rate. The optimal surveillance intervals for LGD was at 1 and 3 years after CE-IM, and for HGD/IMCa at 3, 6, and 12 months, and annually thereafter. These intervals would reduce the number of surveillance endoscopies over 5 years by 38%, while still meeting the specified neoplastic recurrence threshold. A Dutch study also retrospectively examined centralized data on BE surveillance after EET and showed that frequent vs annual surveillance in the first year after CE-IM did not affect the outcome of dysplastic recurrence in short- or long-term follow-up evaluation.14 These data provide compelling evidence for the re-examination of currently recommended surveillance intervals.

Our study differs from the one by Cotton et al13 in several important ways. Our data were derived directly from patient medical records, allowing for granularity with respect to confirmation of dates, histology, and patient outcomes. Importantly, we used our recurrence data to generate metrics for the duration of undetected recurrence, rather than overall observed neoplastic recurrence. This was done to provide a range of outcomes across modeled surveillance paradigms and allow clinicians and guideline authors to weigh these factors in selecting the optimal surveillance timing. Although the precise biology of recurrent BE after CE-IM is not known, data drawn from surveillance of treatment-naïve dysplastic BE can provide some insight. The risk of EAC has been estimated at 6% to 7% annually in HGD and at 0.5% to 1 % in LGD.15,16 What degree of time, then, can pass safely before detection of recurrent BE or dysplasia? In a study of 79 patients with HGD undergoing intensive surveillance (every 3 months for 1 year, decreased only if HGD regressed) for a mean of 7.3 years, no single patient died from complications of esophageal cancer.17 Endoscopic therapy for HGD or IMCa also typically is conducted at 3-month intervals. It therefore may be reasonable to presume that a dysplastic recurrence left undetected for 3 months would be unlikely to result in advanced or metastatic EAC.

Another important difference is the use of a definition of CE-IM as 2 consecutive endoscopic sessions. Sampling error is critical to avoiding misclassification bias when assigning definitions of eradication and recurrence. Recent studies of recurrence after CE-IM have conducted subset analyses modifying this definition from a single to 2 endoscopic sessions and shown no substantial change in their findings. 7,8 However, the number of patients in each of these studies was relatively modest when compared with the Cotton et al13 modeling study and this effect may have had a greater impact on the early recurrence estimates. A meta-analysis of 1973 patients showed that recurrence was higher in the first year for CE-IM defined as a single endoscopy, suggesting this impacts timing of detection more than recurrence rate itself.18

Importantly, this study also examined the actual follow-up intervals of patients with dysplastic BE or IMCa after successful CE-IM. Despite extensive counseling on surveillance intervals, it is evident that recommendations are not strictly followed by patients. Potential reasons for this include patient factors (eg, socioeconomic barriers, personal events, and so forth) and system factors (eg, scheduling delays, lack of centralized BE patient tracking, and so forth).

Indeed, this large real-world cohort with less frequent surveillance than currently recommended clearly shows the implications of this approach. Of 498 patients, only 6 patients (1.2%) developed invasive EAC requiring surgery and/ or chemoradiation. Furthermore, only 1 of these patients (0.2% of total patients) died from complications of metastatic EAC and another died from unknown causes. Thus, despite HGD/IMCa patients having more than 60% fewer than recommended endoscopies in the first 2 years after CE-IM and LGD patients having 28% fewer endoscopies than recommended in 5 years after CE-IM, the clinical outcomes were acceptable overall. The EAC incidence in this study was 1.2 per 100 person-years for pre-ablation HGD/EAC and 0.8 for pre-ablation LGD. This is higher than the incidence rates of 0.6 and 0.51, respectively, seen in patients enrolled in the AIM Dysplasia randomized trial6 and likely is attributable to lower adherence to follow-up recommendations outside of a trial protocol.

The selection of a best surveillance paradigm thus is inherently complex and multidimensional. Is there a tolerable level of invasive EAC during surveillance? It is clear from this study and others referenced that invasive EAC can occur even in a relatively stringent surveillance program. Our data provide an opportunity to weigh the duration of undetected recurrence against the number of endoscopic sessions in a real-world scenario balancing a 33% to 48% reduction in endoscopic evaluations against reasonable outcomes.

We acknowledge certain limitations. By virtue of the retrospective design, treatment protocols could have varied between endoscopists. However, given the expertise of treating endoscopists in BE EET, this is unlikely. Furthermore, the observed recurrence incidence was comparable with those reported in large randomized trials.19,20 The study was performed in expert centers in 2 countries, which may limit global generalizability to other populations. The modeling analysis requires the assumption that rate of dysplastic recurrence was independent of prior nondysplastic recurrence. A recent study supported this notion because dysplastic recurrence incidence was not significantly different between those who did or did not develop GEJ nondysplastic recurrence.21 Nevertheless, it is conceivable that the relationship between nondysplastic and subsequent dysplastic recurrence could impact these estimates. We acknowledge that the clinical significance of nondysplastic recurrence after CE-IM is a matter of some controversy. However, we deliberately included nondysplastic recurrence as an outcome in this analysis for several reasons. Our pre-ablation concept of carcinogenesis assumes that all dysplastic recurrences arise from nondysplastic ones and we endoscopically treat all recurrences. Therefore, the precise natural history of untreated NOBE after CE-IM is not known and progression rates in treatment-naïve NOBE do not provide a valid comparison. An analysis that removes nondysplastic recurrences and creates estimates solely on the basis of dysplastic recurrence incidence would not be a valid statistical model for the outcome of interest. Follow-up data were based on return to the treating facility. Patients could have undergone unreported surveillance at other facilities, although clinical documentation was reviewed carefully to detect this. Finally, the number of patients with LGD, and by extension the number of recurrences in this group, was relatively small and therefore limited predictive estimates based on dysplastic recurrence.

In conclusion, in this study of dysplastic BE patients achieving CE-IM we used recurrence data to model paradigms for more efficient endoscopic surveillance. Despite suboptimal adherence to recommended surveillance timing, patient outcomes generally were good. Furthermore, we suggest strategies that substantially reduce the number of endoscopies with only a modest increase in the proportion of patients with undetected recurrence at more than 6 months, in line with a recent modeling study suggesting similarly expanded strategies. These data are another important step forward in crafting evidence-based guidelines for post-CE-IM surveillance, they provide additional metrics to assess various surveillance paradigms and incorporate an understanding of real-world follow-up evaluation. Further studies are needed to personalize strategies beyond baseline histology and involve patients in the complex decision making that governs their resources and risk.

Supplementary Material

What You Need to Know.

Background

Surveillance after endoscopic eradication of dysplasia or intramucosal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus is performed in frequent intervals and is not evidence-based.

Findings

Cumulative recurrence incidence after successful endoscopic therapy in a large international cohort was modeled to determine optimal surveillance paradigms. For baseline high-grade dysplasia or intramucosal adenocarcinoma, optimal intervals were 6, 12, 18, and 24 months, and then annually. For baseline low-grade dysplasia, optimal intervals were 1, 2, and 4 years.

Implications for patient care

Surveillance intervals likely can be lengthened safely after successful endoscopic therapy of Barrett’s esophagus-related neoplasia, allowing for a substantial reduction in the number of endoscopic surveillance procedures.

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- ACG

American College of Gastroenterology

- BE

Barrett’s esophagus

- CE-IM

complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia

- EAC

esophageal adenocarcinoma

- EET

endoscopic eradication therapy

- EGD

esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- GEJ

gastroesophageal junction

- HGD

high-grade dysplasia

- IMCa

intramucosal adenocarcinoma

- LGD

low-grade dysplasia

- NOBE

nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

This author discloses the following: Prasad Iyer has received research funding from Exact Sciences and Pentax Medical, and has consulted for Medtronic, Ambu, and Symple Surgical. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Allon Kahn, MD (Data curation: Lead; Writing – original draft: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Lead)

Julia Crook, PhD (Data curation: Equal)

Michael Heckman, MS (Data curation: Equal)

Mikolaj Wieczorek, BS (Data curation: Equal)

Sarmed Sarni, MBChB, PhD (Data curation: Equal)

Diana Snyder, MD (Data curation: Equal)

Siddharth Agarwal, MBBS (Data curation: Equal)

Jose Santiago, MD (Data curation: Equal)

Jacobo Ortiz Fernandez-Sardo, MD (Data curation: Equal)

W. Keith Tan, MD (Data curation: Equal)

Ramona Lansing, RN (Data curation: Equal)

Kenneth K. Wang, MD (Data curation: Equal)

Krish Ragunath, MD (Data curation: Equal)

Massimiliano DiPietro, MD (Data curation: Equal)

Herbert Wolfsen, MD (Data curation: Equal)

Francisco Ramirez, MD (Data curation: Equal)

David Fleischer, MD (Data curation: Equal)

Cadman L. Leggett, MD (Data curation: Equal)

Prasad G. Iyer, MD MS (Supervision: Lead; Writing – original draft: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Supplementary Methods

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology at www.cghjournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2022.02.043.

References

- 1.Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111 :30–50; quiz 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Standards of Practice Committee, Wani S, Qumseya B, et al. Endoscopic eradication therapy for patients with Barrett’s esophagus-associated dysplasia and intramucosal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;87:907–931 e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 2014;63:7–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Gastroenterological Association, Spechler SJ, Sharma P, et al. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 2011;140:1084–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Qumseya B, Sultan S, et al. ASGE guideline on screening and surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 2019;90:335–359 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaheen NJ, Overholt BF, Sampliner RE, et al. Durability of radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia. Gastroenterology 2011;141:460–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotton CC, Wolf WA, Overholt BF, et al. Late recurrence of Barrett’s esophagus after complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia is rare: final report from ablation in intestinal metaplasia containing dysplasia trial. Gastroenterology 2017; 53:681–688 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wani S, Han S, Kushnir V, et al. Recurrence is rare following complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia in patients with Barrett’s esophagus and peaks at 18 months. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:2609–2617 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarni SS, Ravindran A, Kahn A, et al. Timeline and location of recurrence following successful ablation in Barrett’s oesophagus: an international multicentre study. Gut 2019;68:1379–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnamoorthi R, Singh S, Ragunathan K, et al. Risk of recurrence of Barrett’s esophagus after successful endoscopic therapy. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83:109G–1106 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii-Lau LL, Cinnor B, Shaheen N, et al. Recurrence of intestinal metaplasia and early neoplasia after endoscopic eradication therapy for Barrett’s esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open 2017;5:E43G–E449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan MC, Kanthasamy KA, Yeh AG, et al. Factors associated with recurrence of Barrett’s esophagus after radiofrequency ablation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:65–72 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cotton CC, Haidry R, Thrift AP, et al. Development of evidence-based surveillance intervals after radiofrequency ablation of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 2018;155:316–326.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Munster S, Nieuwenhuis E, Weusten B, et al. Long-term outcomes after endoscopic treatment for Barrett’s neoplasia with radiofrequency ablation +/− endoscopic resection: results from the national Dutch database in a 10-year period. Gut 2022;71:265–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rastogi A, Puli S, El-Serag HB, et al. Incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett’s esophagus and high-grade dysplasia: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2008;67:394–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh S, Manickam P, Amin AV, et al. Incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus with low-grade dysplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;79:897–909 e4; quiz 83 e1, 83 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schnell TG, Sontag SJ, Chejfec G, et al. Long-term nonsurgical management of Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia. Gastroenterology 2001;120:1607–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawas T, Iyer PG, Alsawas M, et al. Higher rate of Barrett’s detection in the first year after successful endoscopic therapy: meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:959–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phoa KN, Pouw RE, Bisschops R, et al. Multimodality endoscopic eradication for neoplastic Barrett oesophagus: results of an European multicentre study (EURO-II). Gut 2016;65:555–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pouw RE, Klaver E, Phoa KN, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for low-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: long-term outcome of a randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc 2020;92:569–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solfisburg QS, Sarni SS, Gabre J, et al. Clinical significance of recurrent gastroesophageal junction intestinal metaplasia after endoscopic eradication of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.