Key Points

Question

Among adults with type 2 diabetes (T2D), what is the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of the novel, orally administered, small molecule glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist danuglipron?

Findings

In this phase 2 randomized clinical trial in 411 adults with T2D, danuglipron reduced glycated hemoglobin and fasting plasma glucose (at all doses) and body weight (at the highest doses) at week 16 compared with placebo, with the most commonly reported adverse events being gastrointestinal in nature.

Meaning

In this study of patients with T2D, danuglipron demonstrated an efficacy and safety profile consistent with peptidic glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, without injection or fasting restrictions.

This randomized clinical trial investigates the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of danuglipron treatment for 16 weeks in adults with type 2 diabetes and inadequate glycemic control on diet and exercise, with or without the use of metformin.

Abstract

Importance

Currently available glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonists for treating type 2 diabetes (T2D) are peptide agonists that require subcutaneous administration or strict fasting requirements before and after oral administration.

Objective

To investigate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of multiple dose levels of the novel, oral, small molecule GLP-1R agonist danuglipron over 16 weeks.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A phase 2b, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, 6-group randomized clinical trial with 16-week double-blind treatment period and 4-week follow-up was conducted from July 7, 2020, to July 7, 2021. Adults with T2D inadequately controlled by diet and exercise, with or without metformin treatment, were enrolled from 97 clinical research sites in 8 countries or regions.

Interventions

Participants received placebo or danuglipron, 2.5, 10, 40, 80, or 120 mg, all orally administered twice daily with food for 16 weeks. Weekly dose escalation steps were incorporated to achieve danuglipron doses of 40 mg or more twice daily.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Change from baseline in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c, primary end point), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), and body weight were assessed at week 16. Safety was monitored throughout the study period, including a 4-week follow-up period.

Results

Of 411 participants randomized and treated (mean [SD] age, 58.6 [9.3] years; 209 [51%] male), 316 (77%) completed treatment. For all danuglipron doses, HbA1c and FPG were statistically significantly reduced at week 16 vs placebo, with HbA1c reductions up to a least squares mean difference vs placebo of −1.16% (90% CI, −1.47% to −0.86%) for the 120-mg twice daily group and FPG reductions up to a least squares mean difference vs placebo of −33.24 mg/dL (90% CI, −45.63 to −20.84 mg/dL). Body weight was statistically significantly reduced at week 16 compared with placebo in the 80-mg twice daily and 120-mg twice daily groups only, with a least squares mean difference vs placebo of −2.04 kg (90% CI, −3.01 to −1.07 kg) for the 80-mg twice daily group and −4.17 kg (90% CI, −5.15 to −3.18 kg) for the 120-mg twice daily group. The most commonly reported adverse events were nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting.

Conclusions and Relevance

In adults with T2D, danuglipron reduced HbA1c, FPG, and body weight at week 16 compared with placebo, with a tolerability profile consistent with the mechanism of action.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03985293

Introduction

Treatment guidelines recommend glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) based on glycemic need and comorbidities and/or risk factors.1,2 All currently available GLP-1R therapies are peptidic agonists, with most requiring subcutaneous administration.3 Subcutaneous medication can be inconvenient or unsuitable for some patients and result in reduced uptake, adherence, and persistence, with patients generally preferring oral medicines.4,5 Semaglutide is currently the only peptidic GLP-1R agonist available for oral administration but has strict fasting requirements before and after administration.6

The small-molecule GLP-1R agonist danuglipron is being investigated as an adjunct to diet and exercise to improve glycemic control in T2D. It is administered orally, twice daily, with or without food.7 In a humanized mouse model, danuglipron stimulated glucose-dependent insulin release and suppressed food intake with efficacy comparable with injectable peptidic GLP-1R agonists.8 In a phase 1 study, danuglipron reduced glycemic indexes and body weight with favorable safety and pharmacokinetic profiles in adults with T2D taking metformin.8 The objectives of this study were to investigate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of danuglipron during 16 weeks in adults with T2D and inadequate glycemic control on diet and exercise, with or without the use of metformin.

Methods

Study Design

This phase 2b, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group (6 groups), dose-ranging, 16-week randomized clinical trial was conducted from July 7, 2020, to July 7, 2021, across 97 clinical research sites in 8 countries or regions (Bulgaria, Canada, Hungary, Republic of Korea, Poland, Slovakia, Taiwan, and the US). Investigators recruited participants. The study was conducted entirely during the COVID-19 global pandemic. The protocol was approved by institutional review boards or independent ethics committees at each investigational center, and all participants provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles originating in or derived from the Declaration of Helsinki9 and in compliance with International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and all local regulatory requirements were followed. This report followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. The protocol and statistical analysis plan can be found in Supplement 1.

After a screening period, there was a 2-week, single-blind, placebo, run-in period to familiarize participants with the study regimens and monitor compliance, after which participants were randomized (day 1) to 1 of 6 double-blind, parallel groups (placebo or danuglipron target dose of 2.5, 10, 40, 80, or 120 mg twice daily). For danuglipron regimens of 40 mg twice daily and above, up to 6 weeks of the 16-week, double-blind treatment period was used for dose escalation, using a prespecified fixed schedule with starting doses and increments preserved across the study groups (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). Dose deescalation was not permitted. At the end of the treatment period, there was a follow-up period of approximately 4 weeks. Clinic visits occurred at screening, placebo run-in, baseline, weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 16, and follow-up.

Participants abstained from food and drink (except water) for at least 8 hours (preferably 10 hours) before body weight measurements and blood sampling. The sponsor study team and investigative site were blinded to postrandomization measures of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), glucagon, and fasting plasma insulin, unless the FPG results met criteria for hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. Glycemic rescue medication (metformin, sulfonylureas, or sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, prescribed according to local regulations) was permitted if participants experienced persistent fasting hyperglycemia. Participants who discontinued study medication were permitted to continue in the study.

Study Population

Adults (aged 18-75 years, self-reported male or female) with T2D treated with diet and exercise, with or without metformin use, were eligible for inclusion if their HbA1c was 7% or more and no higher than 10.5% (to convert HbA1c percentage to mmol/mol, multiply by 10.93 and subtract 23.50) at screening, body weight was greater than 50 kg and stable, and body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) was in the range of 22.5 (Asia) or 24.5 (North America and Europe) to 45.4. At least 80% of enrolled participants were required to be taking metformin before screening, with no more than 20% of the study population treated with diet and exercise alone. Participants self-reported race and sex. Race and sex data were collected and reported as part of the standard demographic information that is collected in most clinical trials and helps to provide context for these data within the wider literature and in a clinical setting. Analyses were not conducted on the basis of demographic characteristics. Key exclusion criteria can be found in the eMethods in Supplement 2. Participants who were taking metformin were required to receive a stable dose of metformin 60 days or more before screening, and they remained on this same dose throughout the study except when a dose change was medically indicated.

Intervention

Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1:1:1:1 ratio, stratified by the use of metformin and country, to 1 of 6 parallel groups (placebo or danuglipron [PF-06882961] target doses of 2.5, 10, 40, 80, or 120 mg twice daily) based on a randomization code (generated by the sponsor) that used the method of random permuted blocks. Allocation to treatment groups occurred via an interactive web-based response system. Treatment assignment was blinded to participants, investigators, and sponsor personnel, with the exception of the internal review committee members, who were independent of the study team. All study medications (danuglipron or matching placebo) were provided by Pfizer, blinded, in matching blister packs and were taken orally with food twice daily, in the morning and evening, approximately 10 to 12 hours apart, for 16 weeks.

Efficacy and Safety Assessments

Blood samples for HbA1c and FPG were analyzed using standard methods. The primary efficacy end point was change from baseline in HbA1c at week 16. Secondary end points included change from baseline in HbA1c at other time points (weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12), the proportion of participants achieving HbA1c less than 7% (at week 16), and changes from baseline in FPG and body weight at all time points (weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 16).

Safety was monitored throughout the study including the follow-up period; assessments included incidences of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), protocol-defined hypoglycemia10 (for definitions, see eTable 1 in Supplement 2), and treatment-emergent clinical laboratory abnormalities, vital sign abnormalities, and electrocardiogram abnormalities. Adverse events were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 24.0. Exploratory end points included the proportion of participants achieving body weight loss of 5% or more at week 16 and changes from baseline in fasting insulin, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), and glucagon at week 16.

Statistical Analysis

A sample size of approximately 400 was selected to provide approximately 67 participants per group, with approximately 50 completing the study per group (assuming a conservative 25% dropout rate). This yielded 80% power to detect a placebo-adjusted change in HbA1c of 0.5%, using a 1-sided t test at a 5% level and assuming a conservative SD of 1.0%.

The primary efficacy analysis population comprised all randomized participants who took 1 dose or more of study medication and is therefore similar to a modified intention-to-treat approach, where participants were analyzed based on the study medication they were randomized to. For participants who discontinued study medication and/or received glycemic rescue medication, all subsequent values were censored in the analysis. A mixed-model repeated-measures analysis was used to estimate the treatment effects for change from baseline in HbA1c at week 16 (the primary efficacy end point) and at weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12. A similar analysis was used to estimate changes in FPG and body weight at these time points, as well as changes in the exploratory end points (fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, and glucagon) at week 16 and including earlier time points in the models. The mixed-model repeated-measures models included treatment, time, strata (metformin vs diet and exercise alone), and treatment × time interaction as fixed effects, the relevant baseline measure as a covariate, and the baseline × time interaction with time fitted as a repeated effect and participant as a random effect. An unstructured correlation matrix was used, and the Kenward-Roger approximation for estimating degrees of freedom for the model parameters was used.

On the basis of the observed data, participants who reached an HbA1c goal of less than 7% at week 16 were categorized as having a response; otherwise, participants were categorized as not having a response. Participants who discontinued study medication and/or received glycemic rescue medication before week 16 had their week 16 value censored (if it was not missing). The proportion of participants who achieved a response defined as body weight loss of 5% or more at week 16 were similarly analyzed. All participants who took 1 dose or more of study medication were included in the safety analyses. Safety data were summarized descriptively.

Two-sided P < .10 was prespecified as statistically significant for the primary and secondary efficacy end points, with no adjustments for multiple comparisons. SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) was used for all statistical analyses, and therefore reported least squares (LS) mean represent marginal means for a balanced population.

Results

Participants

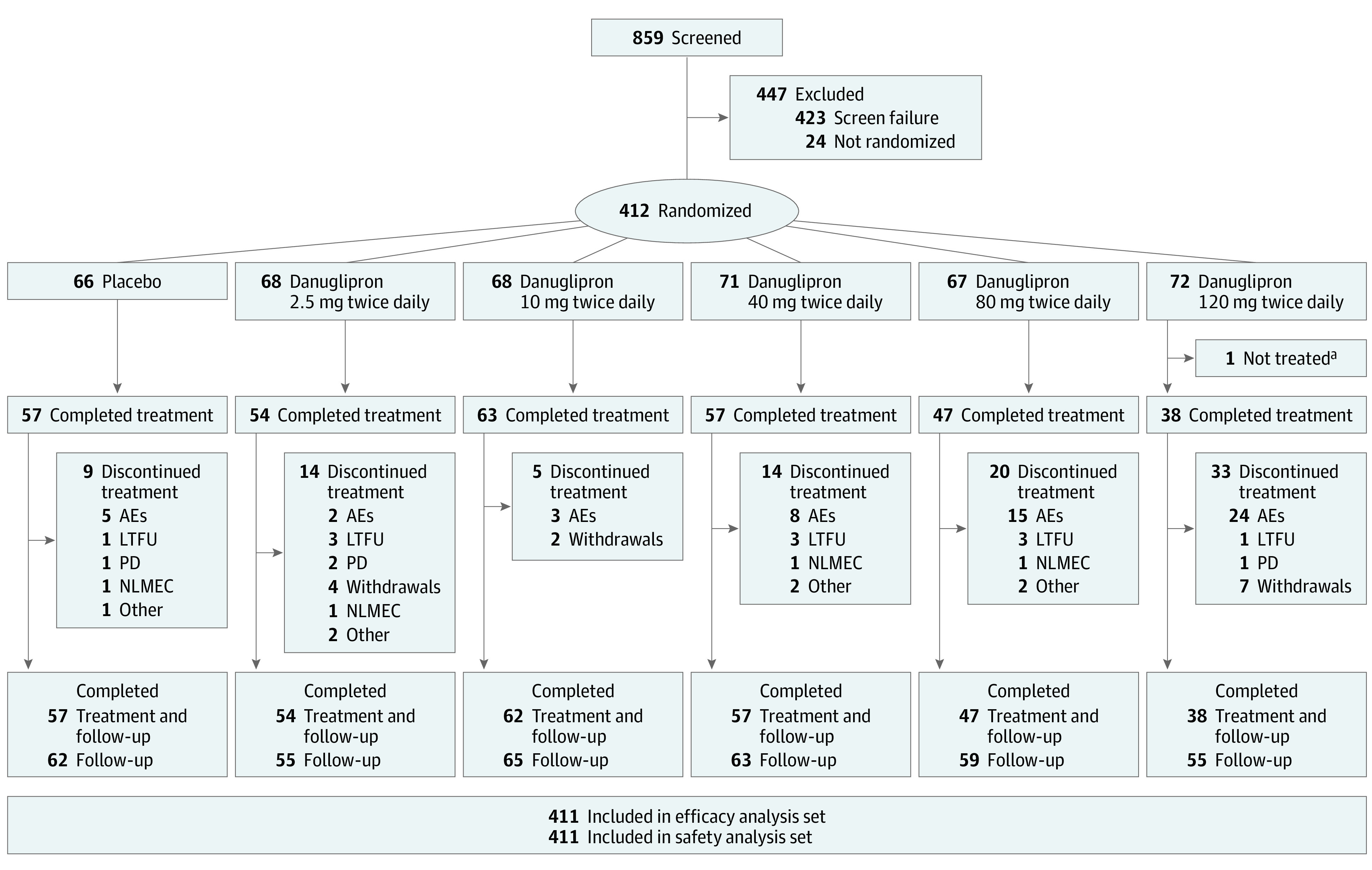

The 411 randomized participants (mean [SD] age, 58.6 [9.33] years; 202 [49%] female and 209 [51%] male) had a mean (SD) HbA1c of 8.07% (0.92%), and mean (SD) BMI of 32.8 (5.25); 376 (91%) were receiving metformin. There were no notable differences in demographic or clinical characteristics across treatment groups (Table 1). Of 859 participants screened, 423 (49%) did not meet the study entry criteria (Figure 1). A total of 411 randomized participants were treated and contributed to both efficacy and safety analysis populations (Figure 1). The double-blind treatment period was completed by 316 participants (77%), with relatively similar proportions across most of the treatment groups (Figure 1). The most common reason for discontinuation from study medication was TEAEs, occurring in 57 randomized participants (14%).

Table 1. Demographic and Baseline Characteristicsa.

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 66) | Danuglipron | Total (N = 411) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 mg twice daily (n = 68) | 10 mg twice daily (n = 68) | 40 mg twice daily (n = 71) | 80 mg twice daily (n = 67) | 120 mg twice daily (n = 71) | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 57.9 (10.27) | 58.9 (9.30) | 58.1 (9.43) | 59.6 (8.58) | 58.4 (9.18) | 58.8 (9.43) | 58.6 (9.33) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 33 (50) | 38 (56) | 35 (51) | 34 (48) | 35 (52) | 34 (48) | 209 (51) |

| Female | 33 (50) | 30 (44) | 33 (49) | 37 (52) | 32 (48) | 37 (52) | 202 (49) |

| Race | |||||||

| Asian | 5 (8) | 7 (10) | 4 (6) | 6 (8) | 6 (9) | 7 (10) | 35 (9) |

| Black or African American | 2 (3) | 4 (6) | 10 (15) | 6 (8) | 1 (1) | 4 (6) | 27 (7) |

| Pacific Islander | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 2 (<1) |

| White | 57 (86) | 57 (84) | 53 (78) | 58 (82) | 59 (88) | 59 (83) | 343 (83) |

| Not reported | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 4 (1) |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 24 (36) | 22 (32) | 17 (25) | 24 (34) | 23 (34) | 18 (25) | 128 (31) |

| Otherb | 42 (64) | 46 (68) | 50 (74) | 47 (66) | 44 (66) | 52 (73) | 281 (68) |

| Not reported | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 2 (<1) |

| T2D duration, mean (SD), y | 8.8 (6.90) | 8.8 (6.31) | 8.5 (6.85) | 8.0 (5.82) | 9.7 (6.20) | 8.7 (7.89) | 8.8 (6.68) |

| HbA1c, mean (SD), % | 8.24 (0.90) | 8.10 (1.03) | 8.01 (0.91) | 8.00 (0.89) | 8.07 (0.95) | 8.05 (0.86) | 8.07 (0.92) |

| FPG, mean (SD), mg/dL | 173.0 (43.74) | 169.3 (42.40) | 165.4 (39.08) | 166.0 (39.33) | 172.8 (45.47) | 169.5 (40.65) | 169.3 (41.65) |

| Body weight, mean (SD), kgc | 90.1 (17.54) | 90.9 (20.13) | 92.3 (16.44) | 90.2 (18.74) | 91.3 (16.64) | 93.1 (17.95) | 91.3 (17.89) |

| BMI, mean (SD)c | 32.5 (5.08) | 32.5 (5.17) | 33.0 (5.34) | 32.3 (5.25) | 32.9 (5.06) | 33.3 (5.70) | 32.8 (5.25) |

| Metformin use | 62 (94) | 63 (93) | 63 (93) | 63 (89) | 62 (93) | 63 (89) | 376 (91) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

SI conversion factors: To convert HbA1c percentage to mmol/mol, multiply by 10.93 and subtract 23.50; to convert FPG to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0555.

Safety analysis set. Data are presented as number (percentage) of participants unless otherwise indicated.

Other includes all ethnicities not identifying as Hispanic or Latino.

Values from screening. One participant in the 80-mg twice daily group had missing data.

Figure 1. Disposition of Study Participants.

If compliance was less than 89% (based on pill count) during the 2-week placebo run-in period, the participant was not randomized and was excluded from the remainder of the study. All treated participants contributed to both efficacy and safety analysis populations. Participants who discontinued treatment might still have continued in the study. The category “completed follow-up” includes participants who completed the double-blind treatment phase as well as those who did not if they continued in the study. Six of 411 participants discontinued for COVID-19–related reasons. AE indicates adverse event; LTFU, lost to follow-up; PD, protocol deviation; and NLMEC, no longer meets eligibility criteria.

aOne participant was randomized to the 120-mg twice daily group but was not treated because of being randomized in error.

Efficacy

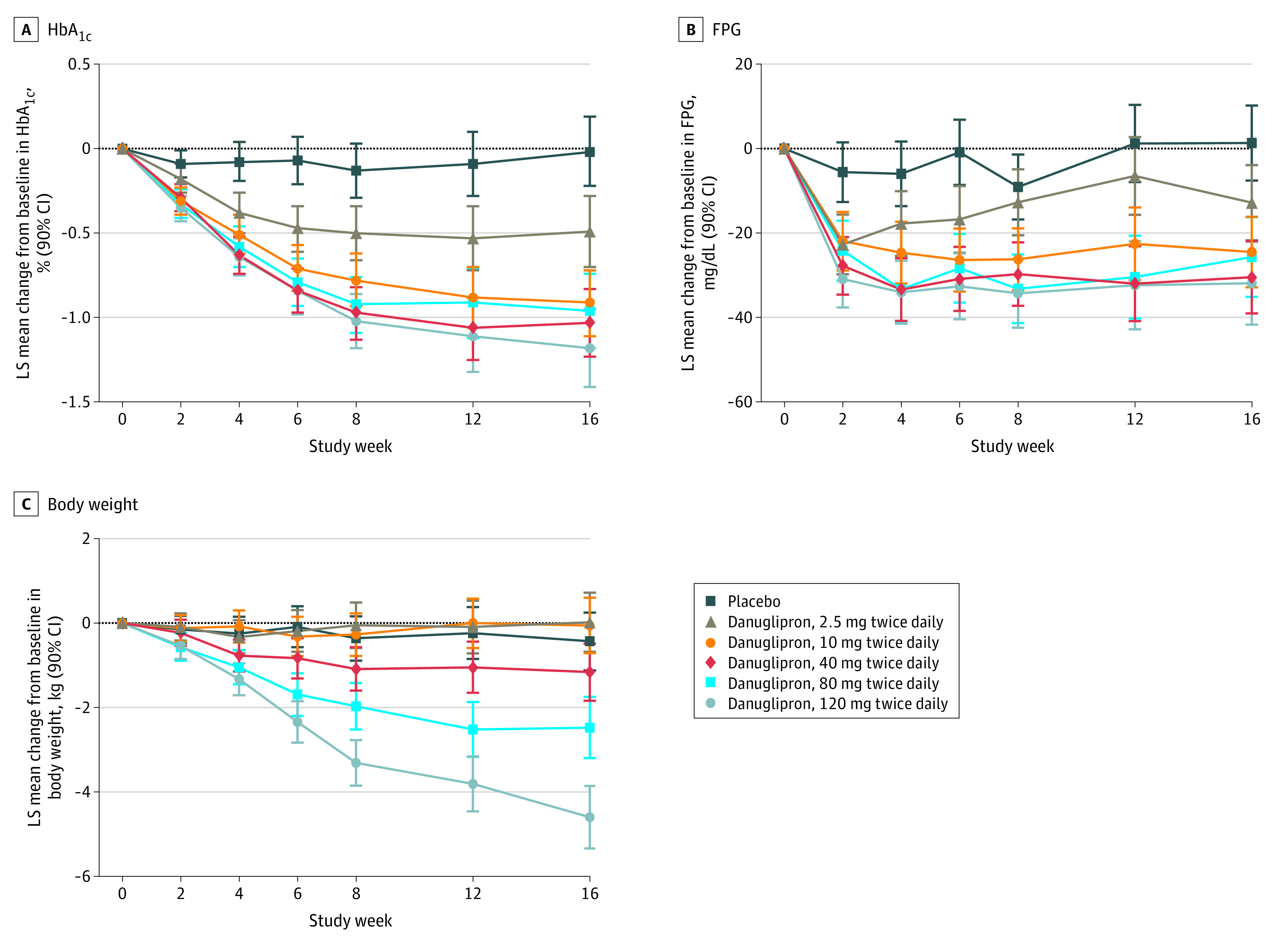

All danuglipron groups demonstrated statistically significant dose-responsive declines from baseline in HbA1c at week 16 compared with placebo, with LS mean changes of −0.49% to −1.18% across danuglipron groups and −0.02% for the placebo group (Table 2). At week 16, the LS mean difference compared with placebo in change in HbA1c was −1.16% (90% CI, −1.47% to −0.86%) for the 120-mg twice daily group (Table 2). With 1 exception, HbA1c was statistically significantly reduced with all danuglipron doses compared with placebo at earlier time points (Figure 2A). At week 16, the observed proportions of participants with HbA1c less than 7% were 31% (16 of 52) for 2.5 mg twice daily, 54% (33 of 61) for 10 mg twice daily, 58% (32 of 55) for 40 mg twice daily, 65% (30 of 46) for 80 mg twice daily, and 61% (23 of 38) for 120 mg twice daily compared with 8% (4 of 52) for placebo.

Table 2. LS Mean Change From Baseline in HbA1c, FPG, and Body Weight at Week 16a.

| Variable | Placebo | Danuglipron | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 mg twice daily | 10 mg twice daily | 40 mg twice daily | 80 mg twice daily | 120 mg twice daily | ||

| HbA1c | ||||||

| Baseline, mean (SD), % | 8.24 (0.90) | 8.10 (1.03) | 8.01 (0.91) | 8.00 (0.89) | 8.07 (0.95) | 8.05 (0.86) |

| No. of participants (week 16) | 52 | 52 | 61 | 55 | 46 | 38 |

| Change from baseline at week 16, LS mean (90% CI) | −0.02 (−0.22 to 0.19) | −0.49 (−0.70 to −0.28) | −0.91 (−1.11 to −0.72) | −1.03 (−1.23 to −0.83) | −0.96 (−1.18 to −0.74) | −1.18 (−1.41 to −0.95) |

| Difference from placebo at week 16, LS mean difference (90% CI) | NA | −0.47 (−0.76 to −0.18) | −0.90 (−1.18 to −0.62) | −1.01 (−1.30 to −0.73) | −0.94 (−1.24 to −0.65) | −1.16 (−1.47 to −0.86) |

| P value vs placebo | NA | .007 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| FPG | ||||||

| Baseline, mean (SD), mg/dL | 173.0 (43.74) | 169.3 (42.40) | 165.4 (39.08) | 166.0 (39.33) | 172.8 (45.47) | 169.5 (40.65) |

| No. of participants (week 16) | 52 | 52 | 61 | 56 | 45 | 38 |

| Change from baseline at week 16, LS mean (90% CI) | 1.31 (−7.58 to 10.20) | −12.81 (−21.71 to −3.91) | −24.53 (−32.88 to −16.18) | −30.47 (−39.06 to −21.87) | −25.71 (−35.15 to −16.26) | −31.93 (−41.73 to −22.13) |

| Difference from placebo at week 16, LS mean difference (90% CI) | NA | −14.12 (−25.77 to −2.47) | −25.84 (−37.05 to −14.62) | −31.78 (−43.20 to −20.35) | −27.02 (−39.03 to −15.01) | −33.24 (−45.63 to −20.84) |

| P value vs placebo | NA | .046 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Body weight | ||||||

| Baseline, mean (SD), kg | 89.9 (17.51) | 90.9 (20.47) | 92.2 (16.47) | 90.0 (18.44) | 91.6 (16.55) | 93.0 (17.86) |

| No. of participants (week 16) | 52 | 53 | 62 | 57 | 46 | 38 |

| Change from baseline at week 16, LS mean (90% CI) | −0.43 (−1.12 to 0.25) | 0.02 (−0.68 to 0.72) | −0.06 (−0.71 to 0.60) | −1.16 (−1.84 to −0.49) | −2.48 (−3.20 to −1.75) | −4.60 (−5.34 to −3.86) |

| Difference from placebo at week 16, LS mean difference (90% CI) | NA | 0.45 (−0.50 to 1.41) | 0.38 (−0.54 to 1.30) | −0.73 (−1.66 to 0.20) | −2.04 (−3.01 to −1.07) | −4.17 (−5.15 to −3.18) |

| P value vs placebo | NA | .43 | .50 | .20 | <.001 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; LS, least squares; NA, not applicable.

SI conversion factors: To convert HbA1c percentage to mmol/mol, multiply by 10.93 and subtract 23.50; to convert FPG to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0555.

Data are for all randomized and treated participants. For participants who discontinued study medication and/or received glycemic rescue medication, all subsequent values were censored in the analysis. An analysis including all data collected after discontinuation from study treatment and/or initiation of rescue medication is presented in eTable 7 in Supplement 2. Baseline is the closest result before dosing on day 1 (HbA1c and FPG) or mean of duplicate measurements collected closest before dosing on day 1 (body weight). Means of duplicates were used in the body weight calculations. Mixed-model repeated-measures analysis included treatment, time, strata (defined as metformin vs diet and exercise alone), and the treatment × time interaction as fixed effects, baseline as a covariate, and the baseline × time interaction with time fitted as a repeated effect and participant as a random effect. An unstructured covariance matrix was used to estimate the variances and covariance within participant across time points. All P values are 2-sided.

Figure 2. Least Squares (LS) Mean Change from Baseline Through the 16-Week Double-Blind Treatment Period for Glycated Hemoglobin (HbA1c), Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG), and Body Weight.

Data are for all randomized and treated participants. For participants who discontinued study medication and/or received glycemic rescue medication, all subsequent values were censored in the analysis. To convert HbA1c to proportion of hemoglobin, multiply by 0.01; to convert FPG to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0555.

At week 16, FPG was statistically significantly reduced with all danuglipron doses compared with placebo, with LS mean differences of −14.12 mg/dL (90% CI, −25.77 to −2.47 mg/dL) in the 2.5-mg twice daily group to −33.24 mg/dL (90% CI, −45.63 to −20.84 mg/dL) in the 120-mg twice daily group (to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0555) (Table 2). With some exceptions, FPG was statistically significantly reduced with all danuglipron doses compared with placebo at earlier time points (Figure 2B).

Body weight was statistically significantly reduced at week 16 compared with placebo in the 80-mg twice daily group (LS mean difference, −2.04 kg; 90% CI, −3.01 kg to −1.07 kg]) and 120-mg twice daily group (−4.17 kg; 90% CI, −5.15 kg to −3.18 kg), but the differences were not statistically significant at lower danuglipron dose levels (Table 2). This pattern was generally evident at earlier time points (Figure 2C). The observed proportions of participants with body weight loss of 5% or more at week 16, relative to baseline, were 6% (3 of 53) for 2.5 mg twice daily, 10% (6 of 62) for 10 mg twice daily, 18% (10 of 57) for 40 mg twice daily, 22% (10 of 46) for 80 mg twice daily, and 47% (18 of 38) for 120 mg twice daily compared with 2% (1 of 52) for placebo. There were no consistent trends in change from baseline for fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, and fasting glucagon across all treatment groups or differences to placebo relative to the danuglipron groups (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Safety

Of the 411 participants, 224 (55%) experienced a total of 538 TEAEs. The proportions of participants with TEAEs were 46% to 64% across danuglipron groups and 48% for placebo (Table 3). The proportion of participants discontinuing study medication because of TEAEs was dose-responsive across danuglipron groups (3%-34% compared with 8% for placebo) (Table 3). Of the 538 TEAEs, 365 (68%) were reported as mild, 154 (29%) were moderate, and 19 (4%) were severe (Table 3). Thirteen participants (3%) had severe TEAEs (Table 3). Thirteen participants (3%) had serious TEAEs, without a notable dose-response relationship across groups (Table 3). One serious TEAE was reported as treatment related (acute cholecystitis in the 80-mg twice daily group) in a participant who had discontinued dosing 3 days after randomization, with the event occurring 42 days after the last dose of study medication. No deaths occurred during the treatment phase; 3 COVID-19–related deaths occurred during the follow-up phase that were not treatment related.

Table 3. Summary of TEAEs (All Causality)a.

| Measurement | No. (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 66) | Danuglipron | Total (N = 411) | |||||

| 2.5 mg Twice daily (n = 68) | 10 mg Twice daily (n = 68) | 40 mg Twice daily (n = 71) | 80 mg Twice daily (n = 67) | 120 mg Twice daily (n = 71) | |||

| No. of TEAEs | 45 | 74 | 75 | 93 | 122 | 129 | 538 |

| Mild | 35 | 54 | 54 | 66 | 70 | 86 | 365 |

| Moderate | 9 | 17 | 20 | 21 | 47 | 40 | 154 |

| Severe | 1 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 19 |

| Participants with ≥1 TEAE | |||||||

| Any TEAE | 32 (48) | 32 (47) | 31 (46) | 42 (59) | 43 (64) | 44 (62) | 224 (55) |

| Serious TEAE | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 6 (8) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 13 (3) |

| Severe TEAE | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 5 (7) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 13 (3) |

| Discontinued study medication because of TEAEb | 5 (8) | 2 (3) | 3 (4) | 8 (11) | 15 (22) | 24 (34) | 57 (14) |

| Discontinued study medication because of TEAE but continued studyc | 4 (6) | 1 (1) | 3 (4) | 6 (8) | 12 (18) | 19 (27) | 45 (11) |

| Discontinued study because of TEAEd | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 4 (6) | 12 (3) |

| Participants with gastrointestinal disorder TEAEe | 5 (8) | 13 (19) | 12 (18) | 22 (31) | 33 (49) | 35 (49) | 120 (29) |

| Participants with TEAE (all preferred terms with ≥5% in any treatment group) | |||||||

| Nausea | 2 (3) | 5 (7) | 5 (7) | 11 (15) | 22 (33) | 23 (32) | 68 (17) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (3) | 3 (4) | 4 (6) | 8 (11) | 12 (18) | 7 (10) | 36 (9) |

| Vomiting | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 5 (7) | 11 (16) | 18 (25) | 35 (9) |

| Headache | 4 (6) | 4 (6) | 1 (1) | 5 (7) | 2 (3) | 7 (10) | 23 (6) |

| Dyspepsia | 0 | 4 (6) | 3 (4) | 2 (3) | 9 (13) | 2 (3) | 20 (5) |

| Hypoglycemiaf | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 4 (6) | 6 (9) | 3 (4) | 15 (4) |

| Dizziness | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 4 (6) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 5 (7) | 15 (4) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 0 | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 4 (6) | 5 (7) | 14 (3) |

| SARS-CoV-2 test result positive | 2 (3) | 4 (6) | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 14 (3) |

| Hyperglycemia | 6 (9) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 | 4 (6) | 0 | 13 (3) |

| Abdominal distension | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) | 4 (6) | 3 (4) | 2 (3) | 11 (3) |

| Decreased appetite | 0 | 2 (3) | 0 | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 5 (7) | 10 (2) |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 5 (7) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 10 (2) |

| Hypertension | 0 | 1 (1) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 4 (6) | 1 (1) | 10 (2) |

Abbreviation: TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Safety analysis set. Except for number of TEAEs, data are number (percentage) of participants, and participants are counted only once per treatment in each row. The table includes all data collected since the first dose of double-blind study medication. Preferred terms are based on Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 24.0 coding dictionary.

Participants who discontinued study medication might still have continued in the study.

Participants with record of a TEAE indicating that the action taken was to withdraw study medication but the TEAE did not cause them to discontinue from the study.

Participants with record of a TEAE indicating the TEAE caused them to be discontinued from the study.

TEAEs with 2 or more occurrences in any treatment group.

These reports of TEAEs of hypoglycemia did not necessarily meet the criteria for protocol-defined hypoglycemic events (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

The most commonly reported TEAEs were nausea (7%-33% across danuglipron groups compared with 3% for placebo), diarrhea (4%-18% vs 3% for placebo), and vomiting (0%-25% vs 0% for placebo) and a higher proportion of participants reported these TEAEs with higher doses of danuglipron compared with placebo (Table 3). The frequencies of nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting at different time points through the study are provided in eFigure 2 in Supplement 2. There were no cases of pancreatitis. There was 1 report of acute cholecystitis (described previously) and no other cases of gallbladder disease. There were no episodes of protocol-defined severe hypoglycemia (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). No clinically significant, adverse trends in vital signs (eTable 3 in Supplement 2); amylase, lipase, calcitonin (eTable 4 in Supplement 2), or other laboratory measures (eTable 5 in Supplement 2); or electrocardiogram (eTable 6 in Supplement 2) were apparent.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study presents the first phase 2 clinical data with an oral small-molecule GLP-1R agonist and found that in adults with T2D, with or without metformin use, danuglipron administration during 16 weeks reduced HbA1c and FPG at all dose levels studied and reduced body weight at doses of 80 mg or more twice daily compared with placebo. Danuglipron was generally safe in this population, with most participants receiving metformin background therapy, with a tolerability profile consistent with the mechanism of action.11,12

Multiple dose levels of danuglipron resulted in HbA1c reductions at 16 weeks of approximately 1%. Reductions in HbA1c and FPG, compared with placebo, were evident for all danuglipron groups as early as week 2 and continued through week 16, with some exceptions for the lowest-dose group. Reductions in HbA1c at week 16 were relatively similar across danuglipron doses of 10 to 120 mg twice daily, and the placebo-adjusted reductions in glycemic parameters are commensurate with phase 2 data with peptidic GLP-1R agonists over similar durations of time.13,14,15 A greater proportion of participants receiving danuglipron compared with placebo achieved the glycemic target of HbA1c less than 7%, and the proportion achieving this target generally increased with higher danuglipron doses.

Reductions in body weight were observed at all time points from week 2 through week 16 with danuglipron doses of 80 mg or more twice daily compared with placebo. Lower doses of danuglipron (≤40 mg twice daily) were body weight neutral and were not clearly different from placebo during the 16-week study duration. The weight loss seen with the higher doses of danuglipron in this study is supported by the phase 1 pharmacodynamic data for danuglipron,8 and the weight loss with danuglipron in the current study is of a similar magnitude to that observed in the phase 2 data for oral semaglutide and the injectable GLP-1R agonists during similar durations of dosing.13,14,15

As has been noted with the GLP-1R agonist class,13,14,15 the most common TEAEs were gastrointestinal in nature and consisted of nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting. Most TEAEs with danuglipron were mild, although TEAEs were also the most common reason for discontinuation, discontinuations due to TEAEs were dose responsive, and dose reduction was not permitted in the study. For danuglipron doses less than 40 mg twice daily, the proportion of participants with TEAEs was similar to placebo, whereas higher doses (≥80 mg twice daily) were associated with higher rates of TEAEs and higher rates of discontinuation related to TEAEs. In the 120-mg twice daily group, 1 participant had TEAEs of severe intensity, which was similar to or lower than other groups, including placebo; and the number of moderate TEAEs was lower than in the 80-mg twice daily group. Although rates of nausea and diarrhea were similar to the 80-mg twice daily group, the rate of vomiting was higher in the 120-mg twice daily group. However, in comparison with semaglutide phase 2 data14,15 (the phase 2 semaglutide studies used more rapid dose escalation schemes compared with the schemes used in the phase 3 semaglutide studies16), the range of proportion of participants experiencing gastrointestinal TEAEs with danuglipron was relatively similar. Consistent with the mechanism of action, the rates of hypoglycemia were low in the current study, and there were no episodes of severe hypoglycemia.

At the time of study design, weekly dose escalation steps were considered an acceptable and efficient approach to assess glycemic efficacy during 16 weeks, taking into account the half-life of danuglipron.7,8 Danuglipron doses were expected to reach pharmacokinetic steady state within the weekly timeframe, and weekly steps were of a longer duration than had been used previously.8 However, clinical data with peptidic GLP-1R agonists have demonstrated that longer dose escalation steps are more likely to result in better tolerability, particularly at higher doses,17 and monthly steps are used for many of the peptidic GLP-1R agonists in clinical use.

Limitations

Limitations of the study include the study duration and rapid dose escalation, which likely impacted optimal assessment of tolerability, leading to greater discontinuation rates, and may have limited efficacy assessments of 120 mg twice daily of danuglipron because the target dose for this group was reached less than 12 weeks before the end of treatment assessment. Dose reduction was not permitted in this phase 2 study. Additional complexity was encountered because the study was conducted during the earliest stages of the COVID-19 pandemic; the indirect impact of the pandemic is difficult to quantify.

Conclusions

This phase 2b randomized clinical trial of danuglipron, a novel, oral, small molecule GLP-1R agonist, demonstrated glycemic and body weight efficacy in a range of doses during a short but clinically relevant timeframe in adults with T2D. The safety and efficacy profile of danuglipron was in line with the peptidic GLP-1R agonists and without fasting restrictions.

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eMethods. Key Exclusion Criteria

eTable 1. Protocol-Defined Hypoglycemic Events

eTable 2. Least Squares Mean Change From Baseline in Pharmacodynamic Outcomes at Week 16

eTable 3. Least Squares Mean Change From Baseline in Vital Signs at Week 16

eTable 4. Least Squares Mean Change From Baseline in Laboratory Measures at Week 16

eTable 5. Clinical Chemistry Laboratory Test Abnormalities

eTable 6. Categorization of Post-Baseline Electrocardiogram Data

eTable 7. Sensitivity Analysis for Least Squares Mean Change From Baseline in HbA1c at Week 16

eFigure 1. Study Design

eFigure 2. Percentage of Participants With Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events (All Causality) of A) Nausea, B) Diarrhea, and C) Vomiting, by Study Week

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Draznin B, Aroda VR, Bakris G, et al. ; American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee . 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(suppl 1):S125-S143. doi: 10.2337/dc22-S009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A, et al. 2019 update to: management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018: a consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2020;43(2):487-493. doi: 10.2337/dci19-0066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hussein H, Zaccardi F, Khunti K, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(7):1035-1046. doi: 10.1111/dom.14008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooke CE, Lee HY, Tong YP, Haines ST. Persistence with injectable antidiabetic agents in members with type 2 diabetes in a commercial managed care organization. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(1):231-238. doi: 10.1185/03007990903421994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sikirica MV, Martin AA, Wood R, Leith A, Piercy J, Higgins V. Reasons for discontinuation of GLP1 receptor agonists: data from a real-world cross-sectional survey of physicians and their patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2017;10:403-412. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S141235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bækdal TA, Breitschaft A, Donsmark M, Maarbjerg SJ, Søndergaard FL, Borregaard J. Effect of various dosing conditions on the pharmacokinetics of oral semaglutide, a human glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue in a tablet formulation. Diabetes Ther. 2021;12(7):1915-1927. doi: 10.1007/s13300-021-01078-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffith DA, Edmonds DJ, Fortin J-P, et al. A small-molecule oral agonist of the human glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor. J Med Chem. 2022;65(12):8208-8226. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saxena AR, Gorman DN, Esquejo RM, et al. Danuglipron (PF-06882961) in type 2 diabetes: a randomized, placebo-controlled, multiple ascending-dose phase 1 trial. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):1079-1087. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01391-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Diabetes Association . 6. Glycemic targets: Standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S61-S70. doi: 10.2337/dc19-S006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drucker DJ. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic application of glucagon-like peptide-1. Cell Metab. 2018;27(4):740-756. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bain EK, Bain SC. Recent developments in GLP-1RA therapy: a review of the latest evidence of efficacy and safety and differences within the class. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(suppl 3):30-39. doi: 10.1111/dom.14487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skrivanek Z, Gaydos BL, Chien JY, et al. Dose-finding results in an adaptive, seamless, randomized trial of once-weekly dulaglutide combined with metformin in type 2 diabetes patients (AWARD-5). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(8):748-756. doi: 10.1111/dom.12305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies M, Pieber TR, Hartoft-Nielsen ML, Hansen OKH, Jabbour S, Rosenstock J. Effect of oral semaglutide compared with placebo and subcutaneous semaglutide on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(15):1460-1470. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.14752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nauck MA, Petrie JR, Sesti G, et al. ; Study 1821 Investigators . A phase 2, randomized, dose-finding study of the novel once-weekly human GLP-1 analog, semaglutide, compared with placebo and open-label liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(2):231-241. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lavernia F, Blonde L. Clinical review of the efficacy and safety of oral semaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with other oral antihyperglycemic agents and placebo. Postgrad Med. 2020;132(suppl 2):15-25. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2020.1798638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drucker DJ, Habener JF, Holst JJ. Discovery, characterization, and clinical development of the glucagon-like peptides. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(12):4217-4227. doi: 10.1172/JCI97233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eMethods. Key Exclusion Criteria

eTable 1. Protocol-Defined Hypoglycemic Events

eTable 2. Least Squares Mean Change From Baseline in Pharmacodynamic Outcomes at Week 16

eTable 3. Least Squares Mean Change From Baseline in Vital Signs at Week 16

eTable 4. Least Squares Mean Change From Baseline in Laboratory Measures at Week 16

eTable 5. Clinical Chemistry Laboratory Test Abnormalities

eTable 6. Categorization of Post-Baseline Electrocardiogram Data

eTable 7. Sensitivity Analysis for Least Squares Mean Change From Baseline in HbA1c at Week 16

eFigure 1. Study Design

eFigure 2. Percentage of Participants With Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events (All Causality) of A) Nausea, B) Diarrhea, and C) Vomiting, by Study Week

Data Sharing Statement