Abstract

This cohort study examines patterns and out-of-pocket costs of instrument-based screening among children 12 to 36 months.

Amblyopia is a leading cause of preventable vision loss, affecting 1.3% to 3.6% of children.1 Vision screening devices can assist pediatricians in identifying amblyogenic risk in younger children for whom eye charts are infeasible.2,3 Vision screening for children 36 months or older should be free for patients per the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,4 but adoption among younger children may not be widespread or accessible. We examined use patterns and costs of instrument-based vision screening for US children and identified factors associated with receipt of screening.

Methods

We used 2018 MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Data for children aged 12 to 36 months as of January 1, 2018, and excluded those with fewer than 12 months of continuous insurance coverage, enrollment in capitated insurance plans, no preventive care encounters, or missing data on residence. Instrument-based vision screening claims were identified using Current Procedural Terminology codes 99174 and 99177. Variables examined included age, sex, geographic region, insurance plan type, number of preventive care visits, type of screening device, median practitioner payment, and frequency and amount of patient out-of-pocket expenses for vision screening by region (eMethods in Supplement 1). Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institutional Review Board deemed this cohort study exempt from review and waived informed consent because deidentified data were used. We followed the STROBE reporting guideline.

Medians and IQRs describe nationwide instrument-based vision screening use, practitioner payment, and out-of-pocket expenses. Multivariable logistic regression models identified factors associated with receipt of vision screening. Analyses were performed using R, version 4.2.0 (R Core Team, 2022). A 2-sided P < .05 indicated significance; data were analyzed from May 19 to December 20, 2022.

Results

This study included 246 077 children (126 728 males [51.5%] and 119 349 females [48.5%]) aged 12 to 36 months as of January 1, 2018. Instrument-based vision screening was received by 48 101 children (19.5%) between January 1 and December 31, 2018.

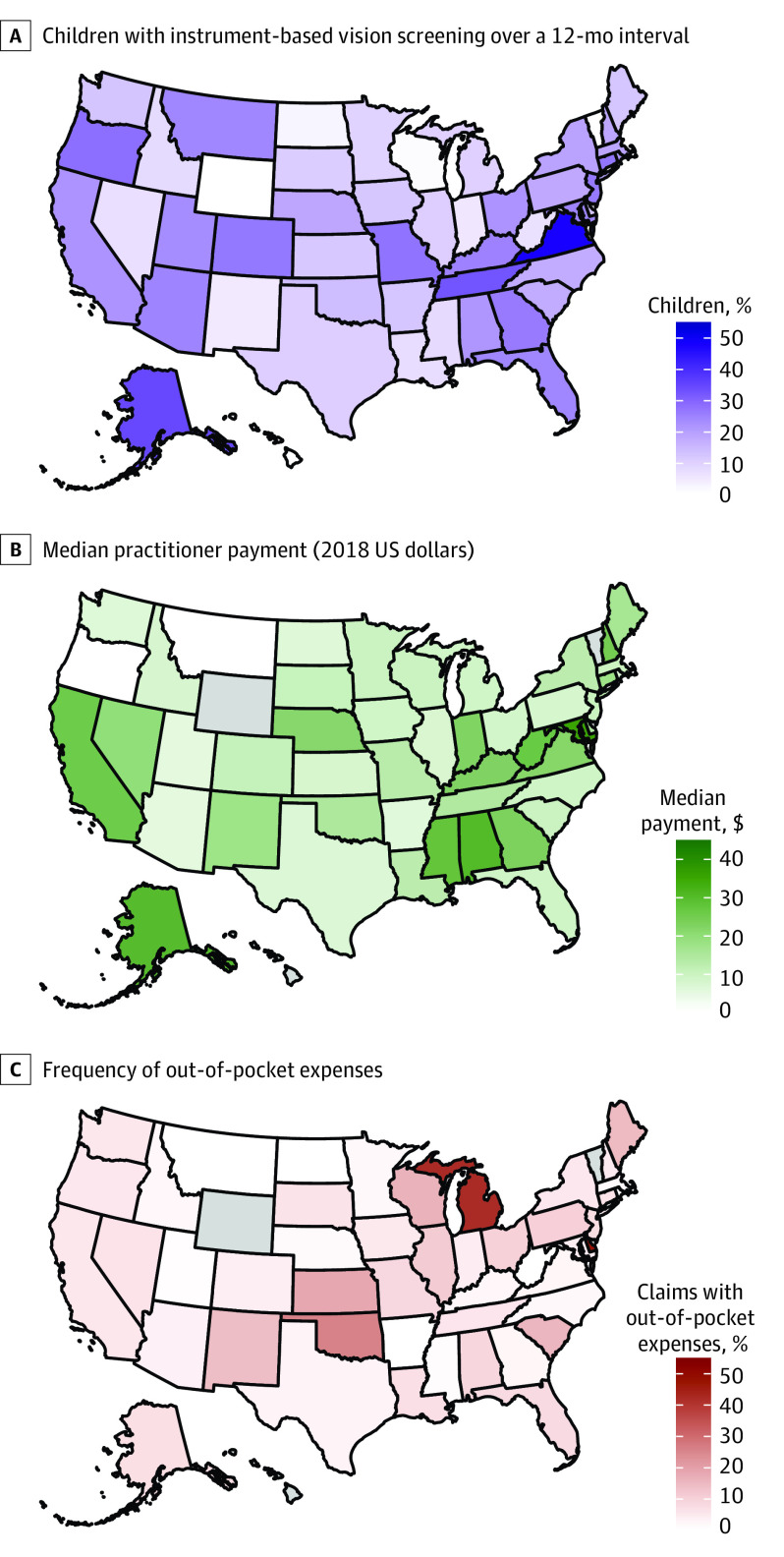

Median (IQR) practitioner payment for instrument-based vision screening claims was $13 ($6-$27). Screening incurred out-of-pocket expenses for 3378 of 48 101 children (7%); 1014 of these 3378 children (30.0%) had expenses related to copayments, 684 (20.2%) to coinsurance, and 1710 (50.7%) to deductibles. Median (IQR) out-of-pocket expense was $11 ($6-$23). There was geographic variation in the frequency of vision screening, median practitioner payment, and frequency of out-of-pocket expenses (Figure).

Figure. Instrument-Based Vision Screening of Commercially Insured US Children Aged 12 to 36 Months .

Data on out-of-pocket expenses include deductibles, coinsurance, and copayment. Children included in the study who were living in Hawaii, Vermont, and Wyoming did not have any instrument-based screening claims during the study period.

Older age, high-deductible plan enrollment, having more than 1 preventive visit, and receiving care within an area in the highest quartile of practitioner payment were associated with increased odds of vision screening (Table). Living in the Midwest and receiving care within an area in the highest quartile of out-of-pocket expense frequency were associated with decreased odds of vision screening.

Table. Factors Associated With Instrument-Based Vision Screening of Commercially Insured US Children Aged 12 to 36 Months.

| Variable | Instrument-based vision screening over a 12-mo interval, No. (%) | Adjusted odds of receiving vision screening, aOR (95% CIb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 197 976) | Yes (n = 48 101) | P valuea | ||

| Age, y | ||||

| 1 to <2 | 105 353 (82) | 22 483 (18) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] |

| 2 to <3 | 92 623 (78) | 25 618 (22) | 1.70 (1.66-1.74) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 95 983 (80) | 23 366 (20) | .70 | 1 [Reference] |

| Male | 101 993 (80) | 24 735 (20) | 0.99 (0.97-1.01) | |

| US Census region | ||||

| South | 76 648 (79) | 20 110 (21) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] |

| West | 33 221 (78) | 9153 (22) | 1.04 (1.01-1.07) | |

| Midwest | 48 971 (86) | 8193 (14) | 0.68 (0.66-0.70) | |

| Northeast | 39 136 (79) | 10 645 (21) | 1.08 (1.05-1.11) | |

| High-deductible insurance plan | ||||

| No | 135 073 (81) | 31 869 (19) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 62 903 (79) | 16 232 (21) | 1.12 (1.09-1.14) | |

| Preventive care visits | ||||

| 1 | 115 444 (83) | 24 330 (17) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] |

| >1 | 82 532 (78) | 23 771 (22) | 1.77 (1.73-1.82) | |

| Screening devicec | ||||

| Off-site interpretation | 86 290 (79) | 22 447 (21) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] |

| On-site interpretation | 111 686 (81) | 25 654 (19) | 1.01 (0.99-1.03) | |

| Median practitioner payment, $c | ||||

| Quartile 1 (<$8.0) | 51 491 (81) | 12 052 (19) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] |

| Quartile 2 ($8.0-$11.4) | 56 212 (84) | 10 454 (16) | 0.78 (0.75-0.80) | |

| Quartile 3 ($11.4-$20.8) | 46 458 (78) | 13 209 (22) | 1.11 (1.08-1.15) | |

| Quartile 4 (>$20.8) | 43 815 (78) | 12 386 (22) | 1.13 (1.10-1.16) | |

| Frequency of out-of-pocket expensesc | ||||

| Quartile 1 (<2.3%) | 50 986 (81) | 11 980 (19) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] |

| Quartile 2 (2.3%-5.0%) | 47 586 (78) | 13 326 (22) | 1.14 (1.11-1.18) | |

| Quartile 3 (5.0%-8.8%) | 48 671 (79) | 12 584 (21) | 1.06 (1.03-1.10) | |

| Quartile 4 (>8.8%) | 50 733 (83) | 10 211 (17) | 0.89 (0.86-0.92) | |

Abbreviation: aOR, adjusted odds ratio.

Pearson χ2 test.

Multivariable logistic regression model includes all variables in the table.

In the core-based statistical area of residence; see the eMethods in Supplement 1 for term definitions.

Discussion

Approximately 1 in 5 commercially insured children aged 12 to 36 months received instrument-based vision screening in 2018. Children in areas with lower practitioner payment and higher frequency of out-of-pocket expenses were less likely to receive vision screening.

Although guidelines support instrument-based vision screening starting at age 12 months,3 the 2017 US Preventive Services Task Force cited insufficient evidence for screening in this age group.4 Therefore, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act requirement that insurance cover vision screening in children without cost does not apply to these children, which may explain limited uptake of screening and our finding that approximately 1 in 14 children had out-of-pocket expenses. Families subject to out-of-pocket costs and those who incorrectly believe payment is required for preventive services, may avoid vision screening.5 Others, especially families with low incomes, may experience financial burden from screening.

This study is limited by use of commercial claims data, which exclude 45% of children with public or no coverage.6 Thus, the nationwide prevalence of vision screening may differ for the general population. Differences in screening device use were associated with practitioner payment and patient out-of-pocket expenses. Mechanisms through which financial barriers may exacerbate disparities in vision screening services deserve further investigation.

eMethods.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Birch EE. Amblyopia and binocular vision. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2013;33:67-84. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silverstein E, Donahue SP. Preschool vision screening: where we have been and where we are going. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;194:xviii-xxiii. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donahue SP, Baker CN; Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics; Section on Ophthalmology, American Academy of Pediatrics; American Association of Certified Orthoptists; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; American Academy of Ophthalmology . Procedures for the evaluation of the visual system by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1). doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonas DE, Amick HR, Wallace IF, et al. Vision screening in children aged 6 months to 5 years: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2017;318(9):845-858. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.9900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reed ME, Graetz I, Fung V, Newhouse JP, Hsu J. In consumer-directed health plans, a majority of patients were unaware of free or low-cost preventive care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(12):2641-2648. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaiser Family Foundation. Health Insurance Coverage of Children 0-18. Published October 28, 2022. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/children-0-18/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.

Data Sharing Statement