Abstract

A 60-year-old woman presented with a fever of unknown origin. Echocardiography revealed a large left atrial tumor protruding into the left ventricle during diastole. Laboratory investigation showed an elevated white blood cell count, C-reactive protein concentration, and interleukin-6 concentration. Magnetic resonance imaging showed hyperacute microinfarcts and multiple old lacunar infarcts. Surgery was performed under suspicion of cardiac myxoma. A dark red jelly-like tumor with an irregular surface was removed. Histopathological examination revealed cardiac myxoma, the surface of which was covered with fibrin and bacterial masses. Preoperative blood culture was positive for Streptococcus vestibularis. These findings were compatible with a diagnosis of infected cardiac myxoma. We used an antibiotic therapeutic regimen for infective endocarditis, and the patient was discharged home on postoperative day 31. Prompt diagnosis and treatment, including effective and efficient antibiotic therapy and complete tumor resection, increased the chance of a better outcome in patients with infected cardiac myxoma.

Keywords: Cardiovascular, surgery, cardiac disease, infected cardiac myxoma

Introduction

Cardiac myxoma is the most common primary cardiac tumor in adults.1,2 It is histologically benign but clinically malignant because of the possibility of embolization. Most instances are sporadic, although family cases of the Carney complex are occasionally observed. Infected cardiac myxoma is a rare entity. 3 Because fever is common in both conditions, it is difficult to differentiate between infected and non-infected myxoma preoperatively. We herein describe the successful treatment of infected cardiac myxoma in a patient who presented with a fever of unknown origin.

Case

A 60-year-old woman developed a fever of >38°C and oral antimicrobial therapy was started. However, the fever lasted for 1 month and echocardiography revealed a large mass in the left atrium. She was transferred to our hospital for surgery in December 2018, before the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. The patient was not immunocompromised, had no recent dental history, and had no other apparent risks.

On admission, her body temperature was 37.4°C, blood pressure was 113/67 mm Hg, heart rate was 104 beats/min and regular, and blood oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. Respiratory and heart sounds were normal and tumor plop sounds were not detected. No neurological deficits were observed.

Laboratory investigation showed an elevated white blood cell count of 14,300/µL and C-reactive protein concentration of 16.4 mg/dL. Her hemoglobin concentration was low at 9.7 g/dL, but hepatic and renal functions were normal. She had elevated concentrations of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (784.8 pg/mL; reference range, 0–125 pg/mL), soluble interleukin (IL)-2 receptor (1590 U/mL; reference range, 121–613 U/mL), and IL-6 (73.3 pg/mL; reference range, 0.0–4.0 pg/mL). She also had elevated concentrations of neuron-specific enolase (24.6 ng/mL; reference range, 0–15 ng/mL) and CA125 (44.4 U/mL; reference range, 0–35 U/mL). Before antimicrobial administration, a blood specimen was collected for culture although Gram staining was not performed immediately after sampling.

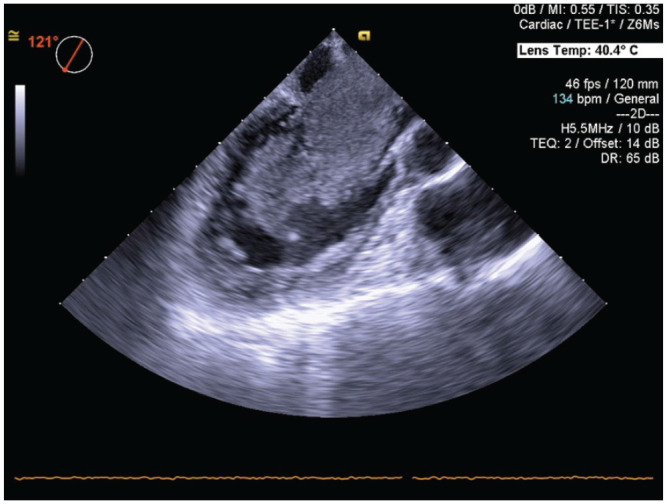

An electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm. Echocardiography revealed a 71- × 32-mm left atrial tumor protruding into the left ventricle during diastole (Figure 1). Normal left ventricular function and mild tricuspid regurgitation with a pressure gradient of 35 mm Hg were also noted. Magnetic resonance imaging showed hyperacute microinfarcts in the left temporal lobe and multiple old lacunar infarcts.

Figure 1.

Transesophageal echocardiography revealed a 71- × 32-mm left atrial tumor protruding into the left ventricle during diastole.

We diagnosed the patient with a left atrial myxoma, and surgery was performed the day after admission. Considering the possibility of infective endocarditis, intravenous ceftriaxone was started upon admission.

Surgery was performed through a median sternotomy with cardiopulmonary bypass. After obtaining cardiac arrest, right-sided left atriotomy was performed. A dark red jelly-like tumor (6.0 × 3.5 × 2.8 cm) with an irregular surface and a 1 cm stalk was attached caudal to the fossa ovalis (Figure 2). The tumor was removed along with the endocardium of the attached area. Many fibrin clots were observed on the posterior mitral leaflet and posterior wall of the left atrium, and they were scraped off as much as possible (Supplemental Material—Video 1). Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography showed no mitral regurgitation, shunt flow, or residual tumor.

Figure 2.

Gross examination revealed a dark red jelly-like tumor with an irregular surface and a stalk attached caudal to the fossa ovalis.

The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful. Her fever subsided quickly after the surgery. Her IL-6 concentration decreased to 7.3 pg/mL on postoperative day (POD) 10. On the day after surgery, her preoperative blood culture exhibited growth of Gram-positive cocci, which were identified as Streptococcus vestibularis on POD 4. All blood cultures taken intraoperatively and postoperatively were negative.

Histopathological examination of the removed mass showed cuboidal cells, spindle-shaped cells, and stellate cells scattered on the background of a myxomatous matrix, and immunohistochemistry was positive for calretinin. The tumor surface was covered with fibrin and bacterial masses (Figure 3). These findings were compatible with a diagnosis of infected cardiac myxoma.

Figure 3.

Histopathological examination showed acute inflammation with neutrophil infiltration and attachment of Gram-positive cocci on the surface of the myxoma (Gram stain, ×400).

Because there are no guidelines for infected cardiac myxoma, we used the antibiotic therapeutic regimen described in the guidelines for infective endocarditis. Intravenous ceftriaxone was continued for 4 weeks after surgery. After intravenous ceftriaxone was switched to oral ampicillin, the patient was discharged home on POD 31. The oral antimicrobial therapy was discontinued 6 months postoperatively. As of the 21st postoperative month, the patient had no recurrence of infection, and no tumor or cerebral aneurysm was detected.

Discussion

Cardiac myxoma is the most common primary cardiac tumor in adults. Its clinical presentation of obstructive, embolic, and constitutional symptoms is known as Goodwin’s triad.2,4 The incidence of asymptomatic cardiac myxoma ranges widely from 0.0% to 28.4%, and the incidence is rising with the advancement of imaging modalities and increased opportunities for screening. 5

Infected cardiac myxoma is rare; only about 80 cases have been reported to date.3,6 According to the diagnostic criteria reported by Revankar and Clark, 3 a definitive diagnosis is confirmed when the following conditions are met: the myxoma is confirmed by pathologic examination, microorganisms are seen on pathologic examination or in a positive blood culture, and inflammation is present on pathologic examination. Because these conditions were met in our case, a diagnosis of infected cardiac myxoma was confirmed.

Our patient presented with a persistent fever, which occurs in approximately 10% to 20% of patients with cardiac myxoma.5,7 Acebo et al. 8 reported that 74% of cardiac myxomas showed the immunohistochemical expression of IL-6. In our patient, the preoperative IL-6 concentration was high and decreased quickly after tumor resection. This inflammatory cytokine causes fever, which makes it difficult to differentiate between infected and non-infected myxoma preoperatively based on the presence of fever alone. Therefore, in a febrile patient with myxoma, it is essential to initiate blood cultures before starting preoperative antimicrobial therapy.

In a review of infected cardiac myxoma, Yuan 6 reported that Gram-positive cocci such as Streptococcus and Staphylococcus accounted for about 70% of the causative organisms. In our case, Streptococcus vestibularis was detected in preoperative blood cultures. Intraoperative blood cultures were negative because antibiotics had been administered. We did not perform a bacterial culture of the tumor. The appropriate duration of postoperative antibiotic treatment is not clear. In two previous review articles, postoperative antibiotics were given for an average of 2.9 weeks 3 and 31.2 days, 6 respectively. In some reports, antimicrobial agents were administered as for the treatment of infective endocarditis.3,6 Thus, we adopted the treatment described in the guidelines for infective endocarditis 9 and used intravenous antibiotics for 4 weeks after surgery.

Thirty to fifty percent of left atrial myxomas cause embolisms. 2 The incidence of embolization was reported to be two to three times higher in patients with infected than non-infected cardiac myxoma because of the fragile fibrin thrombus on the tumor surface, as in infective endocarditis. 10 In our case, various old and fresh multiple cerebral infarctions were also detected by brain magnetic resonance imaging. In addition, the pathological examination showed numerous fibrin clots on the tumor surface and in areas where the tumor contacted normal structures, such as the mitral valve and left atrial wall. Considering the risk of embolization, surgery should be performed as soon as possible after diagnosis in such cases. We suggest there is no benefit in delaying surgery until the results of blood cultures are known.

Similar to the mechanism of mycotic aneurysm formation, cardiac myxoma sometimes induces cerebral aneurysm formation. 11 Therefore, infected myxoma may have a higher risk of cerebral aneurysm formation than non-infected myxoma. The average time from tumor removal to aneurysm discovery was reported to be 3 years. To date, no cerebral aneurysm has been detected in the present case throughout the 21-month follow-up. However, we think longer-term observation is needed.

Conclusion

We reported the successful treatment of a case of infected cardiac myxoma. In patients with concurrent myxoma and fever of unknown origin, infected cardiac myxoma should be suspected. In addition to prompt surgical resection, the following two points are important: preoperative blood culture should be initiated before therapy, and postoperative antimicrobial therapy should be performed using the same regimen as that for infective endocarditis. During postoperative follow-up, the clinician should carefully watch for recurrence of the tumor and infection as well as formation of a cerebral aneurysm.

Supplemental Material

Video 1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Angela Morben, DVM, ELS, and J. Ludovic Croxford, PhD, from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac), for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Author contributions: S.K. conceptualized and wrote the original draft. S.K. and M.H. contributed to the methodology. All authors contributed substantially to the acquisition and analysis of the data. K.K. supervised the writing. All authors have read the manuscript and have approved this submission.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for her anonymized information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Shintaro Kuwauchi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5422-5227

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5422-5227

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Islam AKMM. Cardiac myxomas: a narrative review. World J Cardiol 2022; 14: 206–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reynen K. Cardiac myxomas. N Engl J Med 1995; 333: 1610–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Revankar SG, Clark RA. Infected cardiac myxoma. Case report and literature review. Medicine 1998; 77(5): 337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapiro LM. Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and management. Heart 2001; 85: 218–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee PT, Hong R, Pang PY, et al. Clinical presentation of cardiac myxoma in a Singapore national cardiac centre. Singapore Med J 2021; 62(4): 195–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan SM. Infected cardiac myxoma: an updated review. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg 2015; 30(5): 571–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinede L, Duhaut P, Loire R. Clinical presentation of left atrial cardiac myxoma. A series of 112 consecutive cases. Medicine 2001; 80(3): 159–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acebo E, Val-Bernal JF, Gómez-Román JJ, et al. Clinicopathologic study and DNA analysis of 37 cardiac myxomas: a 28-year experience. Chest 2003; 123(5): 1379–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakatani S, Ohara T, Ashihara K, et al. JCS 2017 guideline on prevention and treatment of infective endocarditis. Circ J 2019; 83: 1767–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagata T, Totsugawa T, Katayama K, et al. Infected cardiac myxoma. J Card Surg 2013; 28: 682–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato T, Saji N, Kobayashi K, et al. A case of cerebral embolism due to cardiac myxoma presenting with multiple cerebral microaneurysms detected on first MRI scans. Clin Neurol 2016; 56(2): 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video 1.