Abstract

Background:

Antidepressants are commonly prescribed medications, but their effect on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality remains unclear.

Methods:

Prospective cohort study of 136 293 community-dwelling postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). Women taking no antidepressants at study entry and who had at least 1 follow-up visit were included. Cardiovascular morbidity and all-cause mortality for women with new antidepressant use at follow-up (n=5496) were compared with those characteristics for women taking no antidepressants at follow-up (mean follow-up, 5.9 years).

Results:

Antidepressant use was not associated with coronary heart disease (CHD). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use was associated with increased stroke risk (hazard ratio [HR],1.45, [95% CI, 1.08-1.97]) and all-cause mortality (HR,1.32 [95% CI, 1.10-1.59]). Annualized rates per 1000 person-years of stroke with no antidepressant use and SSRI use were 2.99 and 4.16, respectively, and death rates were 7.79 and 12.77. Tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) use was associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality (HR,1.67 [95% CI, 1.33-2.09]; annualized rate, 14.14 deaths per 1000 person-years). There were no significant differences between SSRI and TCA use in risk of any outcomes. In analyses by stroke type, SSRI use was associated with incident hemorrhagic stroke (HR, 2.12 [95% CI, 1.10-4.07]) and fatal stroke (HR, 2.10 [95% CI, 1.15-3.81]).

Conclusions:

In postmenopausal women, there were no significant differences between SSRI and TCA use in risk of CHD, stroke, or mortality. Antidepressants were not associated with risk of CHD. Tricyclic antidepressants and SSRIs may be associated with increased risk of mortality, and SSRIs with increased risk of hemorrhagic and fatal stroke, although absolute event risks are low. These findings must be weighed against quality of life and established risks of cardiovascular disease and mortality associated with untreated depression.

Antidepressants are among the most widely prescribed medications in the United States. From 2001 through 2003, more than 10% of participants in the population-based National Comorbidity Survey–Replication study were treated with antidepressants, and the percentage was higher among women and older participants.1 This prevalence represents a more than 5-fold increase over the 1990-1992 period and was particularly pronounced among less severely depressed individuals. Similar trends have been observed in European countries.2

While depression is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,3–5 the effects of antidepressant use on these outcomes is less clear. Formerly first-line therapy, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have now become second-line treatments, in part because of their potential for cardiotoxic effects. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have supplanted TCAs as first-line treatments, in part owing to their relative safety in overdose. Moreover, because of the platelet-aggregating effects of serotonin, the blockade of serotonin reuptake and secondary depletion of platelet serotonin with SSRI use might have protective effects against ischemic cardiovascular events.6–8 In this regard, observational studies of the medical risks of antidepressants have had mixed results.9–13

Importantly, little is known about antidepressant safety among older women, a group at increased risk of both depression and cardiovascular disease. Therefore, we examined the prospective association between new antidepressant use and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in a large cohort of postmenopausal women who participated in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI).14–19

METHODS

The WHI consisted of 3 overlapping clinical trials (CTs) and a longitudinal cohort observational study (OS) conducted in 40 US clinical centers with the aim of investigating risk factors for several chronic diseases in 161 608 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 years. Women were enrolled from 1993 through 1998 and observed for incident events. Details of the study design and baseline characteristics are reported elsewhere.14–19

Recruitment into the WHI was mostly through mass mailings to age-eligible women using voter registration, motor vehicle, and commercial lists. Exclusion criteria included having a condition that would prevent study participation owing to drug dependency or mental illness. At the baseline visit, subjects completed questionnaires on medical and psychosocial characteristics. The first follow-up clinic visit for OS participants was at 3 years and for CT participants at 1 year after baseline and took place from 1997 through 2001 for OS and 1995 through 1999 for CT participants. The first follow-up visit constituted the start of follow-up in our analyses. The protocol and consent were approved by the participating centers’ institutional review boards, and all women gave written informed consent.

Medication use was assessed at baseline and at the first follow-up visit for all participants. Women were asked to bring all medications to the clinic in their original bottles, and drug information was entered into a medications database derived from the Master Drug Data Base (MDDB; Medi-Span, Indianapolis, Indiana). Use of antidepressants was classified into the 4 mutually exclusive categories of SSRIs, TCAs, other or multiple antidepressants, or none. Use of trazodone, which is typically used adjunctively in low doses to promote sleep, was not an exclusion criterion for the SSRI and TCA categories: 72 women were taking an SSRI with trazodone, and 3 women were taking a TCA with trazodone.

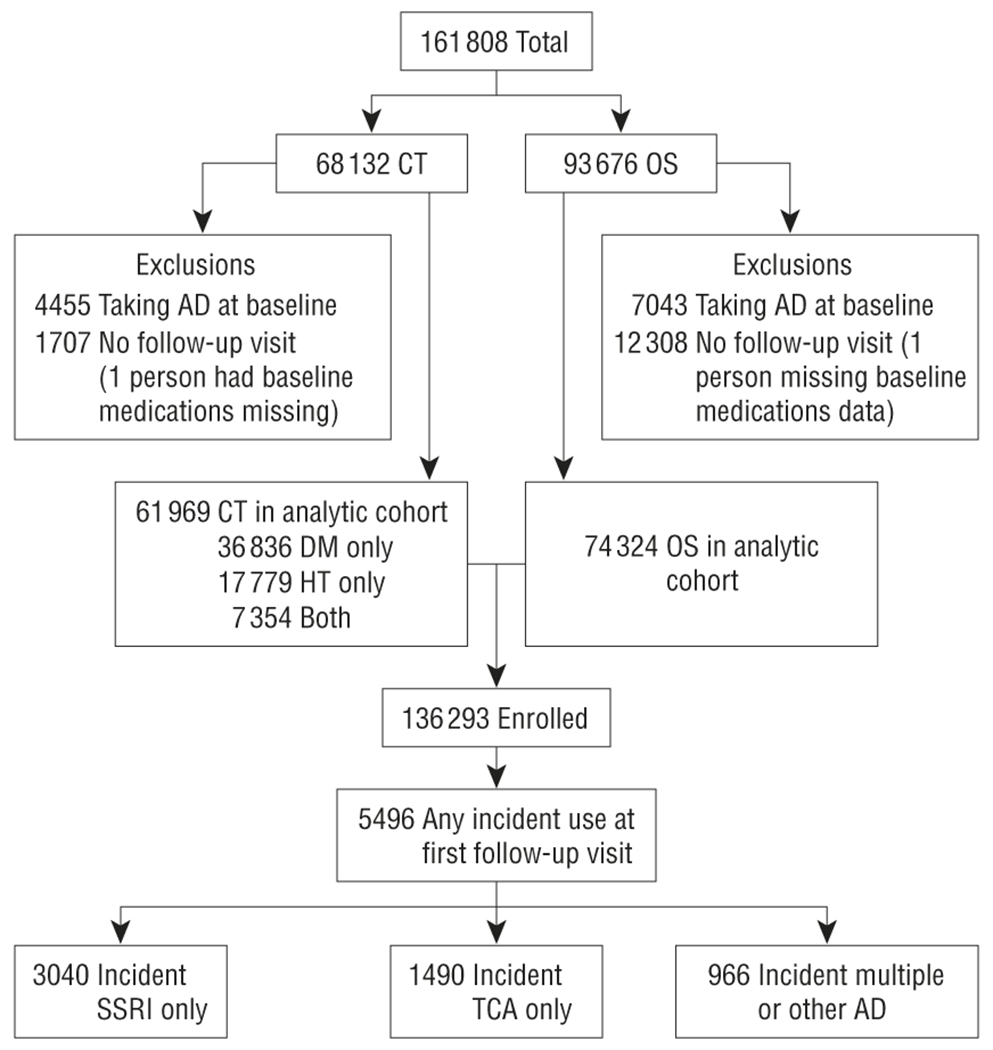

The analytic cohort consisted of women who were taking no antidepressants at baseline and who completed at least 1 follow-up visit (N=136 293). Of these, 74 324 were in the OS and 61 969 were in a CT (Figure 1). New antidepressant use was defined as use of no antidepressant medication at baseline and use of 1 of the categories of antidepressants at the first follow-up visit.

Figure 1.

Diagram depicting derivation of analytic cohort. AD indicates antidepressant; CT, clinical trial; DM, diabetes mellitus; HT, hypertension; OS, observational study; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; and TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

Depression, as described in more detail elsewhere,5 was measured at baseline and first follow-up visit using an 8-item screening instrument developed for the Medical Outcomes Study20 that incorporates 6 items about depressive symptoms from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale21 and 2 items from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule.22 The scale score is based on a logistic regression prediction equation using a weighted combination of responses to these 8 items. This screening instrument has been validated against direct interview assessments in primary care and mental health patients.20 A cut point of 0.06 demonstrated good sensitivity (89%) and specificity (95%) for detecting presence of a depressive disorder in the past month in both the primary care and mental health populations20 and was used to define a positive depression finding in our sample. In a prior study of WHI OS cohort participants,23 the 0.06 cut point exhibited a negative predictive value of 99% for current major depression or dysthymia compared with the gold standard, a psychiatrist-administered semistructured clinical interview (the structured clinical interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [Fourth Edition]) (DSM-IV). However, the positive predictive value was only 20%, indicating that most women in this low-prevalence population classified as depressed would not meet criteria for DSM-IV depression by psychiatric interview, though they may have had subsyndromal symptoms. For lifetime major depression and dysthymia, the negative predictive value was 81%, and the positive predictive value was 52%.

End points were ascertained from medical history update questionnaires mailed annually to OS participants and semiannually to CT participants. Intensive investigation by telephone follow-up obtained additional details from medical records, laboratories, and death certificates. Potential cardiovascular outcomes were centrally adjudicated by trained physicians, and stroke outcomes by neurologists.24 Stroke was defined as the rapid onset of a persistent neurologic deficit attributed to an obstruction lasting longer than 24 hours without evidence for other causes, unless death supervened or there was a demonstrable lesion compatible with acute stroke on a computed tomographic or magnetic resonance imaging scan. Strokes were classified as ischemic or hemorrhagic based on results of brain imaging studies. For death events, communication with proxy respondents and/or National Death Index searches were conducted.

Occurrences considered events for this research were (1) the first occurrence of coronary heart disease (CHD), defined as fatal plus nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) or death due to definite or possible CHD; (2) fatal or nonfatal stroke; and (3) all-cause mortality occurring after the first follow-up visit. Cox proportional hazards models used the time to event for these outcomes, with start time being the first follow-up visit and censoring occurring either when an event took place or at the time of the last available medical update form.

Baseline characteristics were compared among those with no new antidepressant use and those with new use of the various categories of antidepressants. Annualized rates for the combined OS and CT cohorts and for each cohort separately, as well as by age group, were calculated by dividing the number of events after the first follow-up visit by years to the event or to the last follow-up contact for those with no event. This number was multiplied by 1000 to get the annualized rate per 1000 person-years. Hazard ratios (HRs) associated with SSRI or TCA use compared with no use of antidepressants were obtained from Cox proportional hazards models. Analyses combining OS and CT cohorts were stratified by WHI treatment arm, and we allowed the baseline hazard function to vary by treatment arm. This approach to combining cohorts has been previously used in WHI.25 We also compared events among users of SSRIs to those among users of TCAs. Interactions between antidepressant use and depression, aspirin use, migraine, statin use, hormone use, systolic blood pressure, and age were examined by including the interaction terms in the models. In adjusted Cox proportional hazards models, individuals were excluded for missing data on any covariate.

To address potential confounding by indication, we obtained a propensity score from a logistic regression model to predict any new antidepressant use from demographic, lifestyle, risk factor, and comorbidity variables measured at baseline. Thus these propensity scores were a weighted composite of the individual covariates for each person. The C statistic was 0.72, indicating a moderate ability of the variables included in the model to discriminate new use of antidepressants. Propensity scores were used in 2 ways: (1) we stratified on decile of propensity probability in the Cox regressions (STRATA statement in SAS software, version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina); and (2) we matched those taking antidepressants with controls taking no antidepressants by propensity probability. This yielded a matched subset of 8408 participants. We repeated this procedure for propensity to be taking SSRIs and taking TCAs. The matched groups were balanced on race and/or ethnicity, education, income, region of the country, having seen a care provider in the past year, life events, smoking, alcohol intake, physical activity, hormone use, body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, treatment for hypertension, high cholesterol level requiring treatment with pills, diabetes treatment, aspirin, hysterectomy, history of stroke or MI at baseline, and history of cardiovascular disease at baseline. The new antidepressant use group differed slightly in age and had more self-reported migraine, depression, and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), all of which characteristics were controlled for in the Cox models.

We present 5 Cox regression models: (1) unadjusted; (2) adjusted for multiple potential confounders; (3) stratified on propensity and adjusted for multiple potential confounders; (4) sensitivity analysis using model 3 and excluding those subjects with a history of MI or stroke; and (5) analyses of groups matched on propensity score. When reporting HRs, we use those from model 3 unless otherwise noted.

Based on graphical approaches and goodness of fit tests, we detected no violations of the assumption of proportional hazards. All analyses were done using SAS software, version 9.1. Results with P<.05 (2-tailed) were considered statistically significant. No adjustment was made for multiple comparisons, and we present nominal 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For SSRIs in the fully adjusted models, power was 80% at a 2-tailed significance level of .05 to detect HRs of 1.51 for CHD, 1.59 for stroke, and 1.33 for death; the corresponding HRs for TCAs were 1.80 (CHD), 1.94 (stroke), and 1.51 (death).

RESULTS

Of the 161 808 women enrolled in the WHI, 84% (n=136 293) were not taking any antidepressants at baseline and had at least 1 follow-up visit. Four percent (n=5496) were taking some antidepressant at the next follow-up visit, of whom 55.3% (n=3040) were taking only SSRIs; 27.1% (n=1490), TCA only; and 17.6% (n=966) another antidepressant or multiple antidepressants, which might have included an SSRI or TCA. For the combined CT and OS cohort, mean (SD) follow-up after the first follow-up visit was 5.86 (1.73) years (maximum, 10.8 years). For the CT women, follow-up after the first annual visit was 7.14 (1.41) years, and for the OS women, follow-up after the third-year visit was 4.80 (1.17) years.

Comparison of baseline characteristics of women with no new antidepressant use vs those with new use (Table 1) revealed that the subjects in the new use cohort were younger, had more life events in the past year, had higher levels of several cardiovascular risk factors, were more likely to have a history of migraine headache, were more likely to be undergoing hormone therapy, and were more likely to be taking aspirin or NSAIDs.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Women’s Health Initiative14–19 Clinical Trial and Observational Study Participants Who Were Not Taking ADs at Baseline and Had at Least 1 Follow-up Visit

| Participants, % |

Participants, % |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Participants, No.a | No Incident AD Use (n = 130 797) | Any Incident AD Use (n = 5496) | P Value | Incident SSRI Only (n = 3040) | Incident TCA Only (n = 1490) | Incident Other or Multiple AD (n = 966) |

| All | 136 293 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Age, y | <.001 | ||||||

| 50-59 | 44 486 | 32.42 | 37.97 | 39.51 | 31.21 | 43.58 | |

| 60-69 | 61 994 | 45.65 | 41.65 | 40.46 | 44.16 | 41.51 | |

| 70-79 | 29 813 | 21.94 | 20.38 | 20.03 | 24.63 | 14.91 | |

| Race/ethnicity | <.001 | ||||||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 543 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.60 | 0.10 | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 3736 | 2.80 | 1.27 | 1.05 | 1.74 | 1.24 | |

| Black or African American | 12 087 | 9.01 | 5.55 | 5.30 | 7.38 | 3.52 | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5097 | 3.73 | 3.98 | 4.11 | 4.09 | 3.42 | |

| White, not of Hispanic origin | 112 969 | 82.70 | 87.45 | 87.86 | 84.90 | 90.06 | |

| Other | 1527 | 1.12 | 1.02 | 0.82 | 1.07 | 1.55 | |

| Education | .04 | ||||||

| 0-8 y or some high school | 6623 | 4.84 | 5.24 | 5.07 | 6.11 | 4.45 | |

| High school diploma–some college | 74 081 | 54.30 | 55.60 | 54.67 | 58.66 | 53.83 | |

| College graduate or postgraduate | 54 606 | 40.13 | 38.54 | 39.64 | 34.50 | 41.30 | |

| Income, $ | .01 | ||||||

| <20 000 | 20 107 | 14.69 | 16.27 | 14.57 | 20.13 | 15.63 | |

| 20 000-49 999 | 57 247 | 42.02 | 41.56 | 42.01 | 40.94 | 41.10 | |

| ≥50 000 | 50 054 | 36.76 | 35.92 | 36.88 | 32.82 | 37.68 | |

| Do not know | 3516 | 2.59 | 2.40 | 2.50 | 2.48 | 1.97 | |

| Region | <.001 | ||||||

| Northeast | 31 499 | 23.21 | 20.69 | 23.22 | 18.39 | 16.25 | |

| South | 34 533 | 25.11 | 30.71 | 31.41 | 26.85 | 34.47 | |

| Midwest | 30 075 | 22.12 | 20.74 | 19.31 | 23.49 | 21.01 | |

| West | 40 186 | 29.55 | 27.86 | 26.05 | 31.28 | 28.26 | |

| Current care provider | <.001 | ||||||

| No | 8476 | 6.33 | 3.60 | 3.55 | 3.22 | 4.35 | |

| Yes | 126 523 | 92.72 | 95.47 | 95.79 | 95.37 | 94.62 | |

| Life events in the past year, No. | <.001 | ||||||

| 0 | 28 992 | 21.44 | 17.36 | 16.58 | 19.26 | 16.87 | |

| 1 or 2 | 72 699 | 53.48 | 50.09 | 48.95 | 51.95 | 50.83 | |

| 3 or 4 | 26 252 | 19.05 | 24.20 | 25.43 | 21.88 | 23.91 | |

| ≥5 | 5589 | 4.01 | 6.15 | 6.71 | 4.83 | 6.42 | |

| Smoking status | <.001 | ||||||

| Never smoked | 69 849 | 51.51 | 45.11 | 44.74 | 48.12 | 41.61 | |

| Past smoker | 56 015 | 40.92 | 45.40 | 46.58 | 42.82 | 45.65 | |

| Current smoker | 8774 | 6.37 | 8.10 | 7.24 | 7.58 | 11.59 | |

| Alcohol use | <.001 | ||||||

| Nondrinker | 14 594 | 10.77 | 9.22 | 8.26 | 11.14 | 9.32 | |

| Past drinker | 23 819 | 17.27 | 22.49 | 21.94 | 24.50 | 21.12 | |

| <1 Drink/mo | 16 826 | 12.34 | 12.41 | 12.96 | 11.01 | 12.84 | |

| <1 Drink/wk | 28 041 | 20.56 | 20.96 | 20.82 | 21.28 | 20.91 | |

| From 1 to <7 drinks/wk | 35 737 | 26.34 | 23.45 | 24.57 | 21.48 | 22.98 | |

| ≥7 drinks/wk | 16 317 | 12.02 | 10.74 | 10.76 | 9.93 | 11.90 | |

| Physical activity | <.001 | ||||||

| No activity | 19 590 | 14.25 | 17.36 | 17.63 | 15.77 | 18.94 | |

| Some activity of limited duration | 52 307 | 38.37 | 38.46 | 38.72 | 39.73 | 35.71 | |

| From 2 to <4 episodes/wk | 23 334 | 17.13 | 16.87 | 16.84 | 16.71 | 17.18 | |

| 4 Episodes/wk | 34 363 | 25.29 | 23.42 | 23.22 | 22.68 | 25.16 | |

| Hormone use | <.001 | ||||||

| Never used hormones | 45 180 | 33.68 | 20.61 | 21.68 | 20.87 | 16.87 | |

| Past hormone user | 30 663 | 22.53 | 21.82 | 22.70 | 21.48 | 19.57 | |

| Current hormone user | 56 362 | 40.80 | 54.60 | 52.63 | 54.36 | 61.18 | |

| Weight status, BMI | <.001 | ||||||

| Underweight, <18.5 | 1157 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.99 | 0.74 | 0.93 | |

| Normal, 18.5-24.9 | 47 316 | 34.82 | 32.30 | 30.46 | 32.95 | 37.06 | |

| Overweight, 25.0-29.9 | 47 154 | 34.66 | 33.19 | 33.29 | 33.76 | 31.99 | |

| Obesity I, 30.0-34.9 | 24 745 | 18.10 | 19.51 | 19.97 | 19.33 | 18.32 | |

| Obesity II, 35.0-39.9 | 9824 | 7.18 | 7.88 | 8.68 | 6.64 | 7.25 | |

| Extreme obesity III, ≥40 | 4955 | 3.58 | 4.95 | 5.26 | 5.37 | 3.31 | |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | .49 | ||||||

| ≤120 | 52 678 | 38.66 | 38.34 | 38.98 | 34.63 | 42.03 | |

| 120-140 | 55 657 | 40.81 | 41.56 | 42.24 | 41.21 | 39.96 | |

| >140 | 27 854 | 20.46 | 20.00 | 18.72 | 24.09 | 17.70 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | .29 | ||||||

| <90 | 126 956 | 93.14 | 93.47 | 93.65 | 92.75 | 94.00 | |

| ≤90 | 9207 | 6.77 | 6.40 | 6.25 | 7.11 | 5.80 | |

| Hypertension/treatment status | <.001 | ||||||

| Never hypertensive | 86 391 | 63.62 | 57.71 | 58.42 | 53.49 | 62.01 | |

| Untreated hypertensive | 10 230 | 7.47 | 8.26 | 8.09 | 8.19 | 8.90 | |

| Treated hypertensive | 32 033 | 23.26 | 29.39 | 28.82 | 32.62 | 26.19 | |

| High cholesterol requiring treatment with pills | <.001 | ||||||

| No | 110 549 | 81.23 | 78.33 | 79.01 | 74.83 | 81.57 | |

| Yes | 17 417 | 12.62 | 16.54 | 16.12 | 18.46 | 14.91 | |

| Treatment status for diabetes | <.001 | ||||||

| No | 130 840 | 96.10 | 93.69 | 94.57 | 90.47 | 95.86 | |

| Yes | 5342 | 3.83 | 6.15 | 5.30 | 9.19 | 4.14 | |

| Aspirin | <.001 | ||||||

| No | 105 748 | 77.69 | 75.22 | 75.26 | 75.10 | 75.26 | |

| Yes | 30 545 | 22.31 | 24.78 | 24.74 | 24.90 | 24.74 | |

| NSAIDs except aspirin | <.001 | ||||||

| No | 111 465 | 82.12 | 73.82 | 75.36 | 71.07 | 73.19 | |

| Yes | 24 828 | 17.88 | 26.18 | 24.64 | 28.93 | 26.81 | |

| Migraine | <.001 | ||||||

| No | 114 644 | 89.92 | 81.88 | 82.64 | 79.93 | 82.40 | |

| Yes | 13 322 | 10.08 | 18.12 | 17.36 | 20.07 | 17.60 | |

| Depression at baseline | <.001 | ||||||

| No | 120 665 | 89.12 | 74.55 | 71.61 | 82.42 | 71.64 | |

| Yes | 12 135 | 8.34 | 22.29 | 25.36 | 14.09 | 25.26 | |

| History of myocardial infarction before first follow-up visit | <.001 | ||||||

| No | 132 970 | 97.63 | 95.96 | 96.18 | 95.64 | 95.76 | |

| Yes | 3323 | 2.37 | 4.04 | 3.82 | 4.36 | 4.24 | |

| History of stroke before first follow-up visit | <.001 | ||||||

| No | 134 319 | 98.62 | 97.02 | 96.88 | 97.25 | 97.10 | |

| Yes | 1974 | 1.38 | 2.98 | 3.13 | 2.75 | 2.90 | |

Abbreviations: AD, antidepressant; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic AD.

Numbers in categories may not add to full cohort because of missing values for some variables.

Among the analytic cohort, there were 6262 deaths, 2357 strokes, and 2983 CHD events during follow-up. Annualized rates for death, stroke, or CHD were higher for women with new antidepressant use than for those without in both the CT and OS cohorts and in each age group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cardiovascular Events and Annualized Rates by Women’s Health Initiative14–19 Cohort, AD Use at Start of Follow-up, and Agea

| CHD |

Stroke |

Death |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD Status | Participants, No. | Events, No. | Annualized Rateb | Events, No. | Annualized Rateb | Events, No. | Annualized Rateb |

| All Cohorts (Observational Study and Clinical Trials) | |||||||

| No AD at follow-up | 130 797 | 2843 | 3.81 | 2232 | 2.99 | 5881 | 7.79 |

| Incident SSRI | 3040 | 73 | 4.73 | 64 | 4.16 | 201 | 12.77 |

| Incident TCAs | 1490 | 41 | 5.18 | 39 | 4.92 | 114 | 14.14 |

| Incident other or multiple ADs | 966 | 26 | 5.38 | 22 | 4.55 | 66 | 13.42 |

| 136 293 | 2983 | 2357 | 6262 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Observational Study Cohort Only | |||||||

| No AD at follow-up | 70 497 | 1184 | 3.61 | 9866 | 3.00 | 3018 | 9.08 |

| Incident SSRI | 2153 | 43 | 4.45 | 42 | 4.38 | 153 | 15.54 |

| Incident TCAs | 958 | 26 | 6.00 | 24 | 5.52 | 69 | 15.56 |

| Incident other or multiple ADs | 716 | 17 | 5.26 | 15 | 4.64 | 47 | 14.31 |

| 74 324 | 1270 | 9947 | 3287 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Clinical Trials Cohort | |||||||

| No AD at follow-up | 60 300 | 1659 | 3.97 | 1246 | 2.98 | 2863 | 6.77 |

| Incident SSRI | 887 | 30 | 195.19 | 22 | 793.79 | 48 | 8.15 |

| Incident TCAs | 532 | 15 | 4.19 | 15 | 4.19 | 45 | 12.40 |

| Incident other or multiple ADs | 250 | 9 | 5.63 | 7 | 4.36 | 19 | 11.63 |

|

| |||||||

| Clinical Trials Cohort by Age Group, y | |||||||

| 50-59 | |||||||

| No AD at follow-up | 42 399 | 396 | 1.53 | 268 | 1.04 | 830 | 3.20 |

| Any incident AD | 2087 | 35 | 3.02 | 20 | 1.73 | 76 | 6.49 |

| Incident SSRI | 1201 | 19 | 2.85 | 7 | 1.05 | 40 | 5.93 |

| Incident TCAs | 465 | 7 | 2.62 | 6 | 2.27 | 21 | 7.83 |

| Incident other or multiple ADs | 421 | 9 | 4.03 | 7 | 3.11 | 15 | 6.60 |

| 60-69 | |||||||

| No AD at follow-up | 59 705 | 1233 | 3.67 | 965 | 2.87 | 2382 | 7.01 |

| Any incident AD | 2289 | 55 | 4.79 | 50 | 354.35 | 148 | 12.65 |

| Incident SSRI | 1230 | 31 | 5.10 | 32 | 5.29 | 73 | 11.82 |

| Incident TCAs | 658 | 14 | 4.05 | 10 | 2.86 | 44 | 12.42 |

| Incident other or multiple ADs | 401 | 10 | 5.15 | 8 | 4.12 | 31 | 15.64 |

| 70-79 | |||||||

| No AD at follow-up | 28 693 | 1214 | 8.01 | 999 | 6.58 | 2669 | 17.18 |

| Any incident AD | 1120 | 50 | 9.75 | 55 | 10.83 | 157 | 29.53 |

| Incident SSRI | 609 | 23 | 8.57 | 25 | 9.44 | 88 | 31.26 |

| Incident TCAs | 367 | 20 | 8.04 | 23 | 6.65 | 49 | 17.49 |

| Incident other or multiple ADs | 144 | 7 | 10.68 | 7 | 10.87 | 20 | 30.07 |

Abbreviations: AD, antidepressant; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

All cohort members had no antidepressant use at baseline and also had at least 1 follow-up visit.

Per 1000 person-years.

New use of either SSRIs or TCAs was not significantly associated with the risk of CHD (Table 3). However, in unadjusted models, SSRI use was associated with a 40% higher risk of stroke (HR, 1.40 [95% CI, 1.09-1.80]). Hazard ratios were similar in models adjusted for multiple confounders and in propensity analyses, including matched analyses. Use of SSRIs compared with no antidepressant use was associated with a 32% higher relative risk of all-cause death in the adjusted model stratified on propensity score (95% CI, 1.10-1.59). The HR for TCA use was 1.67 (95% CI, 1.33-2.09). In other analyses (not shown), models additionally controlling for antianxiety agents and sensitivity analyses excluding those with treated diabetes mellitus, high cholesterol requiring treatment with pills, or current smoking did not substantively change these associations. There were no significant interactions between antidepressant use and age, migraine headache, or aspirin or NSAID use. Among women treated with antidepressants, there were no significant differences between SSRIs and TCAs for any events. The fully adjusted HR comparing SSRI with TCA was 1.17 (95% CI, 0.75-1.81) for CHD, 1.20 (95% CI, 0.76-1.87) for stroke, and 1.03 (95% CI, 0.79-1.33) for death.

Table 3.

Hazard Ratios for Cardiovascular Events and All-Cause Mortality Associated With Antidepressant Usea

| Statistical Analysis | Events, No./Participants in Analysis, No.b | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSRI | TCA | OM | ||

| MI or CHD Death | ||||

| Model 1, unadjusted | 2982/135 516 | 1.28 (1.01-1.61) | 1.37 (1.01-1.90) | 1.48 (1.00-2.17) |

| Model 2, adjusted for potential confoundersc | 2198/105 256 | 1.10 (0.83-1.48) | 1.00 (0.69-1.44) | 1.23 (076-1.99) |

| Model 3, stratified by propensity decile and adjusted for covariates assessed at start of follow-upd | 1981/95 511 | 0.95 (0.70-1.29) | 1.13 (0.77-1.65) | 1.19 (0.74-1.93) |

| Model 4, as in model 3 but excluding those with Hx stroke or MIe | 1703/92 605 | 0.88 (0.62-1.24) | 1.05 (0.68-1.62) | 1.3 (0.76-2.21) |

| Model 5, matched group analyses adjusted for covariates assessed at start of follow-upf | Varying | 0.74 (0.49-1.11) | 1.02 (0.59-1.77) | 1.30 (0.57-2.94) |

|

| ||||

| Stroke | ||||

| Model 1, unadjusted | 2357/135 666 | 1.40 (1.09-1.80) | 1.66 (1.21-2.28) | 1.54 (1.01-2.35) |

| Model 2, adjusted for potential confoundersc | 1762/105 403 | 1.55 (1.16-2.07) | 1.31 (0.90-1.90) | 1.88 (1.19-2.97) |

| Model 3, stratified by propensity decile and adjusted for covariates assessed at start of follow-upd | 1595/95 643 | 1.45 (1.08-1.97) | 1.35 (0.90-2.03) | 1.80 (1.14-2.85) |

| Model 4, as in model 3 but excluding those with Hx stroke or MIe | 1451/92 603 | 1.39 (1.00-1.91) | 1.27 (0.80-2.00) | 1.97 (1.21-3.19) |

| Model 5, matched group analyses adjusted for covariates assessed at start of follow-upf | Varying | 1.36 (0.88-2.10) | 1.35 (0.71-2.59) | 1.32 (0.66-2.60) |

|

| ||||

| Death | ||||

| Model 1, unadjusted | 6262/136 212 | 1.57 (1.36-1.81) | 1.78 (1.48-2.15) | 1.65 (1.30-2.11) |

| Model 2, adjusted for potential confoundersc | 4525/105 788 | 1.61 (1.35-1.91) | 1.58 (1.27-1.97) | 1.58 (1.17-2.14) |

| Model 3, stratified by propensity decile and adjusted for covariates assessed at start of follow-upd | 4060/95 984 | 1.32 (1.10-1.59) | 1.67 (1.33-2.09) | 1.36 (0.99-1.86) |

| Model 4, as in model 3 but excluding those with Hx stroke or MIe | 3649/92 660 | 1.30 (1.06-1.59) | 1.61 (1.25-2.07) | 1.45 (1.04-2.03) |

| Model 5, matched group analyses adjusted for covariates assessed at start of follow-upf | Varying | 1.37 (1.03-1.82) | 1.37 (0.96-1.98) | 1.42 (0.87-2.32) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CHD, coronary heart disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; Hx, history of; MI, myocardial infarction; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OM, another or multiple antidepressants; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

All analyses for combined observational study and clinical trial cohorts are stratified by study arm.

The numbers vary depending on adjustment because those with missing values in any covariate are omitted from the Cox regression models.

Model 2 is adjusted for the following potential confounders assessed at the baseline screening visit: age, race, income, high cholesterol level requiring treatment with pills, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol intake, treatment for diabetes, log of baseline depression score. Model 2 is also adjusted for the following variables assessed at the start of follow-up: SBP, BMI, log of depression score, hormone use, migraine or bad headache, aspirin or NSAID use, history of stroke or MI.

Model 3 is stratified by decile of propensity to be taking any new antidepressant at the start of follow-up and adjusted for the following covariates assessed at the first follow-up visit: SBP, BMI, log of depression, hormone use, migraine or bad headache, aspirin or NSAID use, and history of stroke or MI.

Model 4 is stratified by propensity decile and adjusted for the same covariates as in model 3 but excludes those with a history of stroke or MI prior to the start of follow-up.

Model 5 involves analyses of matched groups adjusted for the following covariates assessed at the start of follow-up: SBP, log depression score, BMI, hormone use, migraine or bad headache, aspirin or NSAID use, history of MI or stroke.

Numbers vary because separate propensity matchings were done for each antidepressant. For CHD, the numbers were SSRI, 107/4130; TCA, 55/2084; and OM, 30/1411. For stroke, the numbers were SSRI, 89/4125; TCA, 40/2088; and OM, 37/1412. For death, the numbers were SSRI, 211/4162; TCA, 129/2100; and OM, 85/1530. The following variables entered in the propensity logistic: age, race/ethnicity, education, income, physical activity, region of the country, having current health care provider, having last medical visit within past year, alcohol use, smoking, self-reported general health, life events, social functioning, social support, emotional well-being, hormone use, hysterectomy, having been diagnosed as having diabetes ever, being treated for diabetes, having high cholesterol level requiring treatment pills, BMI, waist to hip ratio, SBP, DBP, treatment for hypertension, history of cancer, pulmonary embolism, congestive heart failure, and history of MI, stroke, transient ischemic attack, angina, or revascularization.

Of the 2357 strokes occurring after the first follow-up visit, 1518 were adjudicated as ischemic, 392 as hemorrhagic, 273 as other type, and 174 as unknown type. There were 1907 nonfatal strokes, 445 stroke deaths, and 5 stroke cases in which the patient died of unknown or missing cause. Of the 445 stroke deaths, 134 involved ischemic strokes, 134 hemorrhagic, 24 other, and 153 unknown stroke type. Excess risk of stroke with SSRIs was largely for hemorrhagic stroke (HR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.10-4.07) (Table 4). The risk of ischemic stroke associated with new SSRI use did not reach statistical significance (HR, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.80-1.83). The use of SSRIs and the use of TCAs were both associated with an increased risk of all fatal strokes (HR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.15-3.81 and HR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.26-5.26, respectively). However, SSRIs appeared to convey a higher risk of death from hemorrhagic stroke (HRhemorrhagic stroke death, 2.04; 95% CI, 0.74-5.61) than from ischemic stroke (HRischemic stroke death, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.24-4.11). There were no significant interactions for hemorrhagic stroke between use of SSRIs and use of statins or aspirin.

Table 4.

Hazard Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervalsa for Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Strokes and for Stroke Mortality for Incident Use of Ans Compared With No Use

| New Use of AD | Ischemic Stroke (n = 1026/95 074)b | Hemorrhagic Stroke (n = 271/94 319)b | All Fatal Strokes (n = 288/94 336)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSRI | 1.21 (0.80-1.83) | 2.12 (1.10-4.07) | 2.10 (1.15-3.81) |

| TCA | 1.04 (0.59-1.85) | 1.11 (0.35-3.48) | 2.56 (1.26-5.26) |

| OM | 1.67 (0.92-3.05) | 1.18 (0.29-4.78) | 1.98 (0.73-5.40) |

Abbreviations: AD, antidepressant; BMI, body mass index; MI, myocardial infarction; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OM, another or multiple antidepressants; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic AD.

Cox regression analyses are stratified on treatment arm and on decile of propensity to be taking any new AD and adjusted for the following variables assessed at the start of follow-up: hormone use, log of depression screen score, BMI, history of MI or stroke, systolic blood pressure, migraine or bad headaches, aspirin or NSAID use.

Total reported as number of events/number of participants in the analysis.

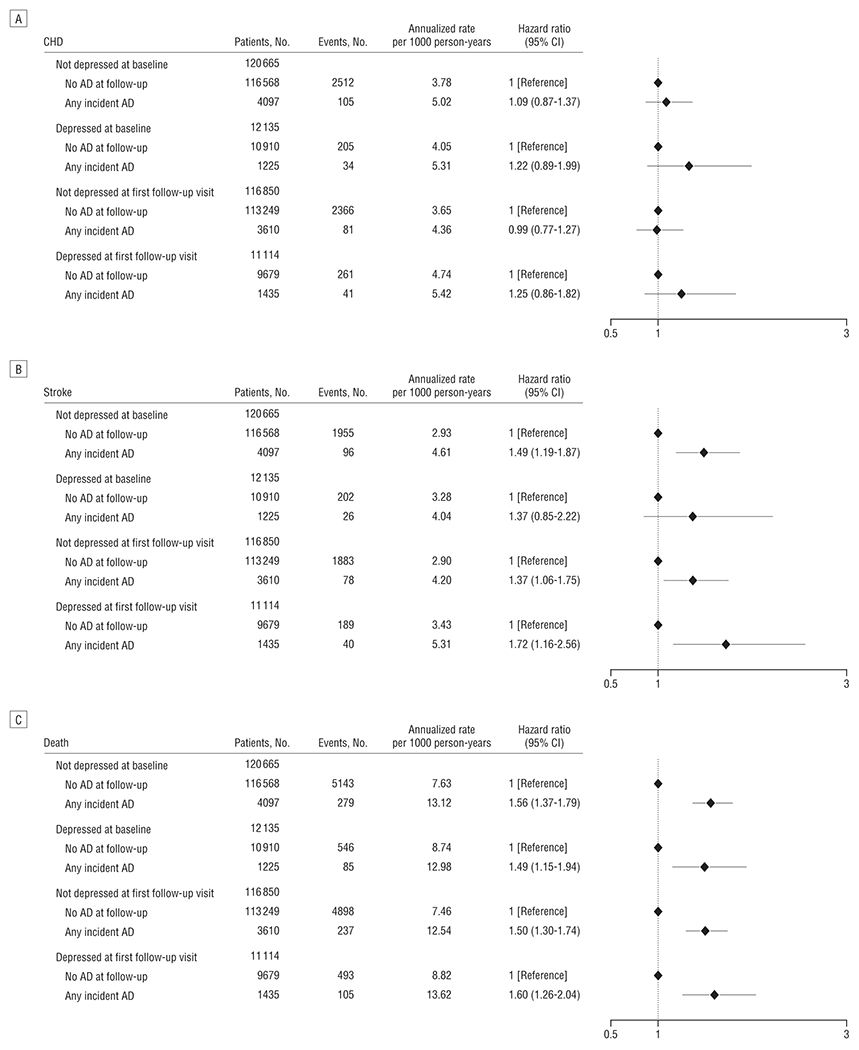

To further explore the sensitivity of our results to the timing of depression assessment, we calculated HRs for any new antidepressant use among those above and below the cut point for depression at baseline and, separately, at first follow-up visit. The risk of stroke and death was elevated whether the baseline or follow-up depression score was used (Figure 2). We examined the distributions of causes of death by antidepressant type and did not observe any clear association between antidepressant classes and cause of death (Table 5).

Figure 2.

Hazard ratios for coronary heart disease (CHD) (A), stroke (B), and all-cause mortality (C). All panels compare antidepressant users and nonusers stratified by depression status at baseline and first follow-up and adjusted for age, race, income, log of depression screen score at baseline and follow-up, systolic blood pressure, high cholesterol level requiring treatment with pills, hypertension treatment, smoking status, physical activity, body mass index, alcohol use, diabetes treatment, history of myocardial infarction or stroke, hormone therapy use, migraine headaches, aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use, and decile of propensity for any incident antidepressant use. AD indicates antidepressant; CI, confidence interval.

Table 5.

Cause of Death as a Percentage of Total Number of Deaths in Each Medication Category

| Incident Use | Total Deaths, No. | Proportion of Total Deaths, % |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke | CVDa | Cancer | Suicide | Other Traumatic | Other or Unknown | ||

| No AD | 5881 | 7.28 | 22.3 | 44.43 | 0.17 | 2.58 | 23.21 |

| No AD among depressed | 546 | 7.14 | 23.44 | 41.21 | 0.00 | 2.38 | 25.82 |

| No AD among nondepressed | 5143 | 7.31 | 22.13 | 45.09 | 0.17 | 2.64 | 22.65 |

| SSRI | 201 | 7.96 | 18.41 | 38.31 | 1.00 | 1.49 | 32.84 |

| TCA | 114 | 10.53 | 21.05 | 33.33 | 0.88 | 1.75 | 32.46 |

| OM | 66 | 6.06 | 30.31 | 33.33 | 1.52 | 3.03 | 25.76 |

Abbreviations: AD, antidepressant; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; OM, another or multiple antidepressants; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic AD.

Cardiovascular disease includes CHD, pulmonary embolism, and other or unknown CVD.

COMMENT

Our results indicate that among postmenopausal women, antidepressant use is associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality and, for SSRI users, stroke (particularly, hemorrhagic stroke). To our knowledge, this is the largest study of the association between antidepressant use and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality among older women. Compared with women with no antidepressantuse, those using SSRIs had a 45% increased relative risk of incident stroke and 32% increased risk of death in models stratified on propensity and adjusted for multiple covariates. The risk of death was similarly increased among TCA users. We did not observe any significant differences in risk between SSRI and TCA users, which suggests that among women whose symptoms were believed to require treatment, neither class of antidepressant was associated with greater risk. Consistent with prior evidence that SSRIs may increase the risk of abnormal bleeding due to their antiplatelet effects, we observed a significantly increased hazard for hemorrhagic stroke among SSRI users compared with nonusers, though absolute risks were small.

A key question is whether the association between antidepressant use and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality is truly related to drug exposure or to underlying differences in other cardiovascular risk factors, including depression, among the exposed groups. In this study, we found adverse effects of antidepressant use despite controlling for traditional cardiovascular risk factors and the propensity to be taking an antidepressant. Depression is an established risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality3–5 and has been associated with an increased risk of stroke4 and increased mortality following stroke and MI.26,27 We found no significant difference in risk of stroke or death between those using SSRIs and those using TCAs, despite their different therapeutic mechanisms, which raises the possibility that residual confounding by depression could account for part of the excess risk.

We attempted to address residual confounding due to depression by exploring multiple ways of removing the variance attributable to depression. Antidepressant exposure was associated with the excess in analyses that (1) controlled for depression at baseline and/or follow-up visits and (2) included depression as a continuous score at both baseline and follow-up as covariates in our fully adjusted models. If residual confounding were operative, we might expect an association with CHD rather than stroke because there were more CHD outcomes, and the association between depression and CHD is better established. Prior evidence from the WHI OS cohort5 demonstrated that the baseline depression screen predicted cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality, which suggests that this measure is sensitive to the morbidity and mortality effects of depression.

The depression screen used in the present study has been used extensively in previous epidemiologic studies20,28–30 and has demonstrated good sensitivity and specificity for detecting major depression and dysthymia in primary care samples.31 Nevertheless, this depression screen was not designed as a diagnostic assessment and has psychometric limitations.23 Thus, we cannot entirely rule out residual confounding. If our observation of increased risk with antidepressant use is attributable to such confounding, our results would at least imply that antidepressant treatment in a community sample of postmenopausal women does not remove the cerebrovascular and mortality risks associated with depressive symptoms.

Consistent with several previous studies,13,32,33 we did not observe an association between antidepressant use and CHD. In 1 study of union health plan members,9 an increased risk of MI was associated with TCA (but not SSRI) use. However, the mean age of this cohort was approximately 45 years, substantially younger than the WHI women. Our results also contrast with several studies that have suggested a protective effect of SSRIs on risk of MI.12,33 A Danish case-control study of first-time hospitalization for MI33 found a modest protective effect of SSRIs but only among individuals with a history of cardiovascular disease. Another case-control study of first MI cases12 found a protective effect for SSRIs with a high affinity for the serotonin transporter but no effect for non-SSRI antidepressants. A study using the United Kingdom General Practice Research Database (GPRD)13 reported a reduced risk of MI among SSRI users but no effect of non-SSRI antidepressants. However, recent past use of SSRIs (discontinued within the past month) was associated with an increased risk of MI. In contrast, a larger study using GPRD data (61% male)10 found an increased risk of MI for both SSRI use (odds ratio [OR], 1.49; 95% CI, 1.43-1.56) and TCA use (OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.37-1.45). In that study, risk was elevated primarily within 28 days of exposure to the antidepressant for both SSRIs and TCAs but was not increased with more prolonged use.

In contrast to our findings for CHD, we observed an increased risk of stroke with antidepressant use, largely attributable to hemorrhagic stroke, consistent with the antiplatelet effects of SSRIs. Of 5 previous studies,4,26,34–36 only 136 found evidence of increased risk of stroke among antidepressant users. In the GPRD database,34 there was no association between use of SSRIs and risk of intracranial hemorrhage. However, this study had limited power, with only 7 SSRI users among 65 cases. A larger registry-based Danish case-control study also did not find an effect of SSRI use on stroke risk,35 although there was a nonsignificant increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke (OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 0.9-6.2) among individuals taking both SSRIs and NSAIDs. No increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke was found in another study of 2441 cases of intracranial hemorrhage and 1776 controls.37 A prospective study of Framingham Heart Study participants4 found no association between antidepressant treatment and stroke, although the analyses did not distinguish type of antidepressants or stroke. The only prior study to find a link between antidepressants and stroke analyzed 1086 cases of depression and stroke and 6515 controls identified through a medical claims database.36 An increased risk of cerebrovascular events was seen with use of SSRIs (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.07-1.44), TCAs (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.10-1.62), and other antidepressants (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.21-1.69). Discrepancies between our results and those of prior studies may be due to differences in methodology, sample characteristics, or power considerations.

The association between antidepressants and all-cause mortality in our study is notable because this outcome has not been widely examined in prior studies. The distribution of causes of death did not indicate any category that accounted for this excess risk. Thus, it remains unclear from our data whether antidepressants have a causal effect on mortality or are merely a marker of increased risk from other causes (eg, residual depressive symptoms) that may not have been fully controlled.

If antidepressants do contribute to stroke and mortality, the pathogenesis could be multifactorial and might vary by drug class. Tricyclic antidepressants have potential cardiac toxic effects that could increase the risk of fatal MI, stroke, and sudden death, including orthostatic hypotension, reduced heart rate variability, and QT interval prolongation.38 Preclinical studies suggest that both TCAs and SSRIs have calcium-channel blocking activity in cardiac myocytes and antagonize voltage-gated ion channels.39,40 Like TCAs, SSRIs and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors appear to have effects on cardiac conduction and negative inotropic effects.39 Also, SSRIs have other effects relevant to cardiovascular outcomes. First, blockade of the serotonin transporter by SSRIs can deplete platelet serotonin levels and interfere with thrombus formation.41 This has been linked to bleeding complications42,43 and could contribute to the association between SSRI use and hemorrhagic stroke observed in our study. Second, serotonin has vasoconstrictive effects on larger cerebral arteries; proserotonergic effects of SSRIs could exacerbate stroke risk, although, despite sporadic reports of cerebral vasospasm associated with serotonergic medications,44 there is little direct evidence for this.45,46 Finally, small studies have found that SSRIs can be associated with adverse effects on a number of cardiovascular risk factors, including reduced heart rate variability, and increases in pulse pressure, C-reactive protein levels, and serum cholesterol levels.47,48

Our results should be considered in light of several limitations. First, this was an observational study and not a randomized trial of antidepressant use. Second, our analyses of multiple outcomes followed by post hoc analyses of stroke subtype may have incurred a risk of type I error. In addition, available data did not permit us to determine precise dosages or medication adherence. Nevertheless, variability in antidepressant exposure might be expected to obscure rather than spuriously produce a relationship between antidepressant use and cardiovascular outcomes.

It should also be noted that we measured exposure (new use of antidepressant) at the first follow-up visit. It is possible that individuals treated only between baseline and first follow-up would be classified as unexposed. This could bias the observed effect estimates toward the null, making our results conservative.

Our exposure definition also does not capture new use of antidepressants after the start of follow-up. A more stringent statistical analysis might treat antidepressant use as a time-dependent variable, since it is probable that antidepressant use changed during follow-up. However, treating antidepressant use as a time-dependent variable was not possible in the combined cohort because in the WHI OS cohort,14–19 antidepressant use was measured only at baseline and the start of follow-up. Thus, our results should be interpreted with great caution. Nevertheless, exposure misclassification during follow-up would likely produce bias toward the null hypothesis.

Furthermore, while the depression screen used herein has been shown to predict cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in this sample,5 it may be less sensitive or specific than a clinician diagnosis of depression. If the increased risks we observed are attributable to residual confounding by depressive symptoms, our results suggest that antidepressant treatment does not neutralize the effects of depression on stroke and mortality among postmenopausal women. Overall, the interpretation and implications of our results must be placed in the context of the observational nature of these analyses, the imperfect measurement of depression, and the known risks associated with depression. Finally, this sample comprised predominantly white older women, and inferences to other populations must be drawn cautiously.

In this prospective study of antidepressant use and incident cardiovascular morbidity and mortality among postmenopausal women, we observed increased risks of all-cause mortality in association with incident use of any antidepressants. The most commonly used antidepressants, SSRIs, were also associated with incident stroke and, in particular, hemorrhagic stroke. Although these results raise concerns about adverse effects of antidepressants, it is important to note that depression itself has been implicated as a risk factor for CHD, stroke, early death, and other adverse outcomes. In addition, inadequately treated depression is associated with substantial disability, impairments in quality of life, and health care costs.49 Nevertheless, our results suggest that physicians should be vigilant about controlling other modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in women taking antidepressants. Further research is needed to clarify the risk-benefit ratio of antidepressant use among older women.

After acceptance of the manuscript for this article, we became aware of a recent report by Whang et al50 that also found no relationship between antidepressant use and CHD but found a significant association with sudden cardiac death. As in our study, the possibility of residual confounding by depression cannot be ruled out.

Women’s Health Initiative Investigators.

Program Office

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland: Elizabeth Nabel, Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Joan McGowan, Leslie Ford, and Nancy Geller.

Clinical Coordinating Centers

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington: Ross Prentice, Garnet Anderson, Andrea LaCroix, Charles L. Kooperberg, Ruth E. Patterson, Anne McTiernan; Medical Research Labs, Highland Heights, Kentucky: Evan Stein; University of California at San Francisco: Steven Cummings.

Clinical Centers

Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York: Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller; Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas: Aleksandar Rajkovic; Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts: JoAnn E. Manson; Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island: Charles B. Eaton; Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia: Lawrence Phillips; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle: Shirley Beresford; George Washington University Medical Center, Washington, DC: Lisa Martin; Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor–UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California: Rowan Chlebowski; Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, Portland, Oregon: Yvonne Michael; Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, California: Bette Caan; Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee: Jane Morley Kotchen; MedStar Research Institute and Howard University, Washington, DC: Barbara V. Howard; Northwestern University, Chicago and Evanston, Illinois: Linda Van Horn; Rush Medical Center, Chicago: Henry Black; Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, California: Marcia L. Stefanick; State University of New York at Stony Brook: Dorothy Lane; The Ohio State University, Columbus: Rebecca Jackson; University of Alabama at Birmingham: Cora E. Lewis; University of Arizona, Tucson and Phoenix: Cynthia A. Thomson; New York University at Buffalo: Jean Wactawski-Wende; University of California at Davis and Sacramento: John Robbins; University of California at Irvine: F. Allan Hubbell; University of California at Los Angeles: Lauren Nathan; University of California at San Diego, LaJolla, and Chula Vista: Robert D. Langer; University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio: Margery Gass; University of Florida, Gainesville and Jacksonville: Marian Limacher; University of Hawaii, Honolulu: J. David Curb; University of Iowa, Iowa City and Davenport: Robert Wallace; University of Massachusetts and Fallon Clinic, Worcester: Judith Ockene; University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark: Norman Lasser; University of Miami, Miami, Florida: Mary Jo O’Sullivan; University of Minnesota, Minneapolis: Karen Margolis; University of Nevada, Reno: Robert Brunner; University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill: Gerardo Heiss; University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Lewis Kuller; University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis: Karen C. Johnson; University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio: Robert Brzyski; University of Wisconsin, Madison: Gloria E. Sarto; Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina: Mara Vitolins; Wayne State University School of Medicine and Hutzel Hospital, Detroit, Michigan: Michael Simon.

Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study

Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem: Sally Shumaker.

Financial Disclosure:

Dr Smoller has served as a consultant for Eli Lilly; received honoraria from Hoffman-La Roche Inc, Enterprise Analysis Corporation, and MPM Capital; and served on an advisory board for Roche Diagnostics Corporation. Dr Perlis has received honoraria and/or consulting and/or speaking fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Proteus LLC; he is also a stockholder in Concordant Rater Systems LLC from which he received consulting fees and royalties. Dr Robinson has received grants from Abbott, Aegerion, Andrx Labs, Astra-Zeneca, Atherogenics Inc, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffman La Roche, Merck, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Sankyo, Schering-Plough, Takeda, and Wyeth Ayerst; she has received speaker honoraria for education programs from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, and Pfizer and honoraria from Reliant; she has also served as consultant for and/or on the advisory boards of Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Pfizer, Proliant, and Wellmark. Dr Wenger has received research grants and/or contracts and/or served on a trial steering committee and/or trial adjudication committee for Pfizer, Merck, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Gilead Sciences (formerly CV Therapeutics), Abbott, Sanofi-Aventis, and Eli Lilly; she has held consultantships with the Women’s Advisory Board, Gilead Sciences (formerly CV Therapeutics), Cardiovascular Advisory Board, Leadership Council for Improving Cardiovascular Care (LCIC) Executive Committee, Schering-Plough, AstraZeneca, Abbott, Merck, Pfizer, Boston Scientific, Medtronic Women’s CV Health Advisory Panel, and Genzyme. Dr Wassertheil-Smoller received an honorarium from the GLG HealthCare Council.

Funding/Support:

The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, through contracts N01WH22110, 24152, 32100-2, 32105-6, 32108-9, 32111-13, 32115, 32118-32119, 32122, 42107-26, 42129-32, and 44221.

Contributor Information

Jordan W. Smoller, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Matthew Allison, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, University of California San Diego, La Jolla.

Barbara B. Cochrane, Department of Family & Child Nursing, University of Washington, Seattle.

J. David Curb, Department of Geriatric Medicine, John A. Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Roy H. Perlis, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Jennifer G. Robinson, Departments of Epidemiology & Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City.

Milagros C. Rosal, Division of Preventive and Behavioral Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester.

Nanette K. Wenger, Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia.

Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller, Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mojtabai R Increase in antidepressant medication in the US adult population between 1990 and 2003. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(2):83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montagnier D, Barberger-Gateau P, Jacqmin-Gadda H, et al. Evolution of prevalence of depressive symptoms and antidepressant use between 1988 and 1999 in a large sample of older French people: results from the personnes agées quid study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(12):1839–1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, et al. Depression as a risk factor for coronary artery disease: evidence, mechanisms, and treatment. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(3):305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salaycik KJ, Kelly-Hayes M, Beiser A, et al. Depressive symptoms and risk of stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 2007;38(1):16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wassertheil-Smoller S, Shumaker S, Ockene J, et al. Depression and cardiovascular sequelae in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(3):289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maurer-Spurej E, Pittendreigh C, Solomons K. The influence of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on human platelet serotonin. Thromb Haemost. 2004; 91(1):119–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nair GV, Gurbel PA, O’Connor CM, Gattis WA, Murugesan SR, Serebruany VL. Depression, coronary events, platelet inhibition, and serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(3):321–323, A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serebruany VL, Gurbel PA, O’Connor CM. Platelet inhibition by sertraline and N-desmethylsertraline: a possible missing link between depression, coronary events, and mortality benefits of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Pharmacol Res. 2001;43(5):453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen HW, Gibson G, Alderman MH. Excess risk of myocardial infarction in patients treated with antidepressant medications: association with use of tricyclic agents. Am J Med. 2000;108(1):2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tata LJ, West J, Smith C, et al. General population based study of the impact of tricyclic and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitorantidepressants on the risk of acute myocardial infarction. Heart. 2005;91(4):465–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sauer WH, Berlin JA, Kimmel SE. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;104(16):1894–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sauer WH, Berlin JA, Kimmel SE. Effect of antidepressants and their relative affinity for the serotonin transporter on the risk of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;108(1):32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlienger RG, Fischer LM, Jick H, Meier CR. Current use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of acute myocardial infarction. Drug Saf. 2004;27(14):1157–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Women’s Health Initiative Study Group. Design of the Women’s Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19(1):61–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curb JD, McTiernan A, Heckbert SR, et al. ; WHI Morbidity and Mortality Committee. Outcomes ascertainmentand adjudication methods in the Women’s Health Initiative. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9)(suppl):S122–S128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Cauley JA, McGowan J. The Women’s Health Initiative calcium-vitamin D trial: overview and baseline characteristics of participants. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9)(suppl):S98–S106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langer RD, White E, Lewis CE, Kotchen JM, Hendrix SL, Trevisan M. The Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study: baseline characteristics of participants and reliability of baseline measures. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9)(suppl):S107–S121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritenbaugh C, Patterson RE, Chlebowski RT, et al. The Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification trial: overview and baseline characteristics of participants. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9)(suppl):S87–S97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stefanick ML, Cochrane BB, Hsia J, Barad DH, Liu JH, Johnson SR. The Women’s Health Initiative postmenopausal hormone trials: overviewand baseline characteristics of participants. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9)(suppl):S78–S86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burnam MA, Wells K, Leake B, Landsverk J. Development of a brief screening instrument for detecting depressive disorders. Med Care. 1988;26(8):775–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radloff L The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(4):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robins LN, Helzer J, Croughan J, Ratcliff K. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(4):381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tuunainen A, Langer RD, Klauber MR, Kripke DF. Short version of the CES-D (Burnam screen) for depression in reference to the structured psychiatric interview. Psychiatry Res. 2001;103(2-3):261–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wassertheil-Smoller S, Hendrix SL, Limacher M, et al. ; WHI Investigators. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on stroke in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289(20):2673–2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neuhouser ML, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Thomson C, et al. Multivitamin use and risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease in the Women’s Health Initiative cohorts. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(3):294–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams LS, Ghose SS, Swindle RW. Depression and other mental health diagnoses increase mortality risk after ischemic stroke. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(6):1090–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dickens C, McGowan L, Percival C, et al. New onset depression following myocardial infarction predicts cardiac mortality. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(4):450–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262 (7):914–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spangler L, Scholes D, Brunner RL, et al. Depressive symptoms, bone loss, and fractures in postmenopausal women. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):567–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hlatky MA, Boothroyd D, Vittinghoff E, Sharp P, Whooley MA; Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. Quality-of-life and depressive symptoms in postmenopausal women after receiving hormone therapy: results from the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS) trial. JAMA. 2002;287(5):591–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mulrow CD, Williams JW Jr, Gerety MB, Ramirez G, Montiel OM, Kerber C. Case-finding instruments for depression in primary care settings. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122(12):913–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meier CR, Schlienger RG, Jick H. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of developing first-time acute myocardial infarction. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;52(2):179–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monster TB, Johnsen SP, Olsen ML, McLaughlin JK, Sorensen HT. Antidepressants and risk of first-time hospitalization for myocardial infarction: a population-based case-control study. Am J Med. 2004;117(10):732–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Abajo FJ, Jick H, Derby L, Jick S, Schmitz S. Intracranial haemorrhage and use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;50(1):43–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bak S, Tsiropoulos I, Kjaersgaard JO, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and the risk of stroke: a population-based case-control study. Stroke. 2002;33(6):1465–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Y, Guo JJ, Li H, Wulsin L, Patel NC. Risk of cerebrovascular events associated with antidepressant use in patients with depression: a population-based, nested case-control study. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(2):177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kharofa J, Sekar P, Haverbusch M, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of hemorrhagic stroke. Stroke. 2007;38(11):3049–3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roose SP, Laghrissi-Thode F, Kennedy JS, et al. Comparison of paroxetine and nortriptyline in depressed patients with ischemic heart disease. JAMA. 1998;279(4):287–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pacher P, Kecskemeti V. Cardiovascular side effects of newantidepressants and an-tipsychotics: new drugs, old concerns? Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10(20):2463–2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zahradník I, Minarovic I, Zahradnikova A. Inhibition of the cardiac L-type calcium channel current by antidepressant drugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324(3):977–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hergovich N, Aigner M, Eichler HG, Entlicher J, Drucker C, Jilma B. Paroxetine decreases platelet serotonin storage and platelet function in human beings. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;68(4):435–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dalton SO, Johansen C, Mellemkjaer L, Norgard B, Sorensen HT, Olsen JH. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding: a population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Opatrny L, Delaney JA, Suissa S. Gastro-intestinal haemorrhage risks of selective serotonin receptor antagonist therapy: a new look. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(1):76–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singhal AB, Topcuoglu MA, Dorer DJ, Ogilvy CS, Carter BS, Koroshetz WJ. SSRI and statin use increases the risk for vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology. 2005;64(6):1008–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramasubbu R Cerebrovascular effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(12):1642–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noskin O, Jafarimojarrad E, Libman RB, Nelson JL. Diffuse cerebral vasoconstriction (Call-Fleming syndrome) and stroke associated with antidepressants. Neurology. 2006;67(1):159–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dawood T, Lambert EA, Barton DA, et al. Specific serotonin reuptake inhibition in major depressive disorder adversely affects novel markers of cardiac risk. Hypertens Res. 2007;30(4):285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim EJ, Yu BH. Increased cholesterol levels after paroxetine treatment in patients with panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25(6):597–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Merikangas KR, Ames M, Cui L, et al. The impact of comorbidity of mental and physical conditions on role disability in the US adult household population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1180–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whang W, Kubzansky LD, Kawachi I, et al. Depression and risk of sudden cardiac death and coronary heart disease in women: results from the Nurses’ Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(11):950–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]