Abstract

The CBA mouse model was used to investigate the immunopathology induced in the lung by the pathogenic equine herpesvirus 1 (EHV-1) strain RacL11 in comparison to infection with the attenuated vaccine candidate strain KyA. Intranasal infection with KyA resulted in almost no inflammatory infiltration in the lung. In contrast, infection with the pathogenic RacL11 strain induced a severe alveolar and interstitial inflammation, consisting primarily of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils. Infection with either EHV-1 strain resulted in the accumulation of similar numbers and ratios of CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes in the lung and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid. Further analysis of these T-cell populations revealed identical EHV-1-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses. RNase protection analysis of RNA isolated from the BAL fluid of RacL11-infected mice on day 3 postinfection revealed much higher levels of RNA specific for macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α), MIP-1β, and MIP-2 than were observed for KyA-infected mice. Furthermore, significantly higher levels of transcripts specific for tumor necrosis factor alpha were induced on day 3 postinfection with RacL11 compared with KyA. These findings suggest that the early production of proinflammatory beta chemokines plays a major role in the severe, most often lethal, respiratory inflammatory response induced by the pathogenic EHV-1 strain RacL11.

Naturally occurring mucosal infection of the horse with equine herpesvirus 1 (EHV-1) typically results in respiratory distress, abortogenic disease, and, albeit rarely, severe neurological sequelae (5, 13, 24, 30, 31, 32). By far the most devastating outcome of EHV-1 infection of the horse is the induction of abortion in pregnant mares, which has a severe economic impact on the equine industry. EHV-1-induced abortion in pregnant mares requires a sequential infection of the respiratory epithelium, followed by infection of mononuclear cells and T cells, resulting in a cell-associated viremia and subsequent infection of endothelial cells within the endometrial vasculature (6, 10, 40). Currently, there are no available EHV-1 vaccines that elicit long-term immunity and protection in the horse (11, 12, 22).

The mouse model of EHV-1 infection was originally established in various mouse strains (2, 7). We recently adapted this model to CBA (H-2k) mice to allow characterization of the primary and memory EHV-1-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses to the attenuated vaccine candidate EHV-1 strain KyA (15, 28, 41). In these studies it was reported that KyA afforded protection in the mouse and the horse against subsequent infection with the highly pathogenic EHV-1. It was observed that KyA infection of CBA mice resulted in no clinical signs of infection. In contrast, infection of CBA mice with the pathogenic RacL11 strain resulted in severe weight loss, ruffled fur, huddling behavior, and eventually death between days 6 and 8 postinfection (41, 48).

Those observations strongly suggested a fundamental difference between these two EHV-1 strains in growth potential in vivo and/or in the host-virus interaction. Measurement of virus levels in the lungs on days 2 through 6 postinfection indicated that the pathogenic RacL11 strain was cleared from the lung tissue with kinetics identical to those observed following infection with the attenuated KyA strain. Infection with either EHV-1 strain resulted in peak viral titers on day 2 postinfection, and infectious virus was completely eliminated from the lung tissue by day 6 (40). Since these mice succumbed to RacL11 infection on days 6 to 8 postinfection, it was speculated that death was likely the result of the host interaction with EHV-1 RacL11, and not the result of inability to clear this EHV-1 strain from the lung. A clear understanding of the immune mechanisms that constitute a protective “appropriate” response versus a potentially damaging “inappropriate” response and the identification of viral components responsible for eliciting those responses are imperative for the development of an immunoprophylactic vaccine.

In the present study, we examined the acquired immune response in the infected lung following infection with EHV-1 KyA or RacL11 and the subsequent immunopathology as a result of that response. We found that intranasal (i.n.) infection with the pathogenic RacL11 strain results in a severe inflammatory infiltration involving the majority of the lung tissue, a finding not observed following KyA infection. Lung sections taken from RacL11-infected mice revealed a massive cellular consolidation of the lung, consisting primarily of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils. Lung sections from KyA-infected mice were almost completely clear of inflammatory infiltration, closely resembling sections taken from mock-infected mice. These results suggest that, while the immune response elicited by KyA is protective, the response to RacL11 is damaging and results in the death of the animal. Immune mechanisms potentially playing a role in this inappropriate response and leading to severe immunopathology of the lung are characterized and discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus and cell culture.

EHV-1 KyA and RacL11 viral stocks used for i.n. infection of mice were propagated on L2 mouse fibroblast monolayers. Titers of both virus strains were determined by standard plaque titration on RK monolayers as described previously (37, 41, 48, 49). Cells were maintained at 37°C in Eagle's minimal essential medium supplemented with penicillin (100 U per ml), streptomycin (100 μg per ml), nonessential amino acids, and 5% fetal calf serum (FCS).

Mice.

Female CBA mice, 3 to 6 weeks of age, were obtained from Harlan Sprague Dawley (Indianapolis, Ind.). Mice were maintained in the Animal Resource Facility of the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, Shreveport, in filter-topped cages. This facility is certified by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International, and all procedures were approved by the University Animal Care Committee. All mice were rested a minimum of 1 week prior to use. In all experiments, mouse groups consisted of at least five mice each. CTL assays and RNase protection analysis were performed using pooled cells isolated from groups of five mice. All experiments were performed a minimum of three times.

Histopathology.

Representative lungs from groups of infected (i.n., with 2 × 106 PFU of KyA or RacL11) mice consisting of five mice per group were infused in vivo with 1 ml of 10% buffered formalin, removed, and placed in 10% buffered formalin. Paraffin sections were cut, and individual sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Identification and quantitation of cells isolated from the BAL fluid.

Mice were infected i.n. with 2 × 106 PFU of KyA or RacL11, and the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was recovered on day 5 postinfection as follows. Mice were sacrificed by halothane inhalation, and the pleural cavity was exposed. The trachea was cut just below the larynx, and a smooth-tipped 20-gauge needle was inserted into the trachea. The needle was secured in place by tying with waxed dental floss. BAL fluid was obtained by using a 1-ml syringe to infuse 1-ml aliquots of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in and out of the lungs five times for a total of 5 ml. Cells isolated from the BAL fluid were then air dried onto a glass slide, fixed for 5 min in methanol, stained for 20 min with Giemsa stain, and rinsed with double-distilled water. Cell types were identified by standard morphological evaluation under light microscopy, and percentages of each cell type were determined by a differential count of at least 200 stained cells per sample. The data are presented as mean percentages over a range of five separate experiments.

Infection and assessment of CTL activity.

CBA mice were anesthetized with halothane (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, Mo.) and inoculated i.n. with 2 × 106 PFU of EHV-1 KyA or RacL11 in an inoculum volume of 50 μl. To assess primary CTL activity in the lung at 5 days postinfection, lymphocytes were isolated from the lung tissues as follows. The lungs were removed in the absence of the draining mediastinal lymph nodes (LN), and the tissue was minced with scissors, pressed through a 60-gauge mesh screen, and digested for 90 min with collagenase (250 U per ml) and DNase I (50 U per ml). The released lymphocytes were briefly exposed at 37°C to Tris-buffered 0.83% NH4Cl to lyse erythrocytes and then cultured for 3 days at 37°C under 5% CO2 in 12-well plates at a concentration of 107 cells per well in a total volume of 4 ml of complete RPMI 1640 (Sigma) containing 5% FCS, 20 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM HEPES, 2 mM l-glutamine, and antibiotics. Cytolytic activity was assessed in a standard 4-h 51Cr release assay in 96-well V-bottom plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) against a range of effector-to-target ratios, utilizing 104 51Cr-labeled, KyA-infected or mock-infected murine L2 fibroblasts (H-2k) as previously described (40). The percentage of specific lysis was determined by using the formula (A − B)/(C − B) × 100, where A is the amount of 51Cr released by target cells incubated with effector cells (experimental release), B is the amount of 51Cr released from targets incubated in medium alone (spontaneous release), and C is the amount of 51Cr released from targets incubated in 3% acetic acid (maximum release). Each effector-to-target ratio was assayed in triplicate. The spontaneous release never exceeded 20%, and the variability among the specific-lysis values of triplicate cultures did not exceed 5%.

Flow cytometric analysis.

Lymphocytes were isolated from lungs 5 days postinfection by pressing through a 60-gauge screen and digestion with DNase-collagenase as described above. Lymphocytes were isolated from the BAL fluid on day 5 postinfection as described above. Following isolation, the resulting lymphocytes were stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated monoclonal antibodies specific for murine CD4 or CD8 (PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) and a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated monoclonal antibody specific for murine CD3ɛ (PharMingen). Stained cells were analyzed on a FACScaliber flow cytometer-analyzer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.). Flow cytometric and off-line data analyses were provided by the Core Facility for Flow Cytometry, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, Shreveport.

Isolation of mRNA and RNase protection analysis.

BAL fluid was obtained 3 days post-i.n. infection with either KyA or RacL11 as described above. RNA was obtained from the resulting cells by using the TRIZOL reagent (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

RNase protection assays were performed by using the 32P-based RiboQuant Multi-Probe RNase protection assay system (PharMingen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Protected RNA species and appropriate standards were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using 5% acrylamide gels, which were then blotted onto filter paper, dried, and exposed to film. The resulting film was scanned using the UV Transilluminator 2000 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.), and bands were quantitated by using the Quantity One program (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

RESULTS

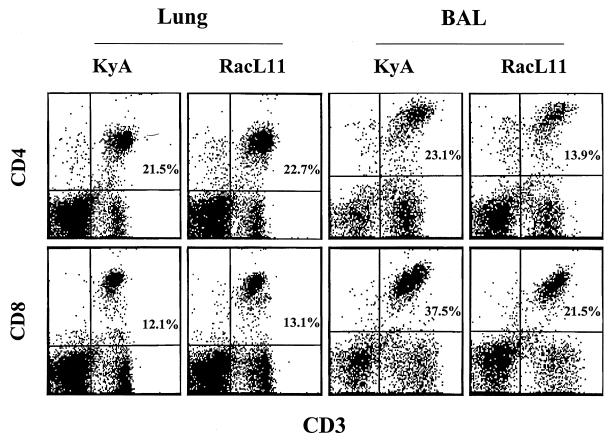

Flow cytometric analysis of T cells isolated from the lung.

The striking differences between the outcomes of infection with KyA versus RacL11 strongly suggested that a fundamental difference exists between the ways these two strains grow in vivo and/or between the immune responses elicited to them. The former was ruled out by our previous demonstration that infectious RacL11 and KyA are completely cleared from the lung tissue by day 6 postinfection with identical kinetics (41). These results and the observation that the mice exhibited labored breathing before succumbing to infection suggested that the fatality observed following RacL11 infection might be the result of severe immunopathology in the lung. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that CD4 and CD8 T cells isolated from the entire lung were present in almost identical CD4/CD8 ratios of approximately 2:1 at 5 days following infection with either KyA or pathogenic RacL11 (Fig. 1). Interestingly, in the BAL fluid on day 5 postinfection, CD8 T cells were the predominant lymphocyte population, and a CD4/CD8 ratio of approximately 0.6:1 was observed in both RacL11- and KyA-infected mice (Fig. 1). Although T cells were present in the lungs of KyA- and RacL11-infected mice in comparable numbers and ratios, the total number of cells isolated from RacL11-infected lungs, most likely infiltrating monocytes and granulocytes, was generally 5- to 10-fold greater (data not shown). These results suggested a much more vigorous inflammatory infiltration into the lung in response to infection with RacL11.

FIG. 1.

Flow cytometric analysis of lymphocytes isolated from EHV-1-infected lungs on day 5 postinfection. CBA mice were infected i.n. with 2 × 106 PFU of EHV-1 KyA or RacL11. At 5 days postinfection, the lungs were removed, and lymphocytes were isolated by collagenase-DNase digestion as described in Materials and Methods. BAL fluid was obtained at day 5 postinfection as described in Materials and Methods. The resulting lymphocytes were then double stained with FITC-CD3ɛ and PE-CD4 or PE-CD8 and were analyzed by flow cytometric analysis.

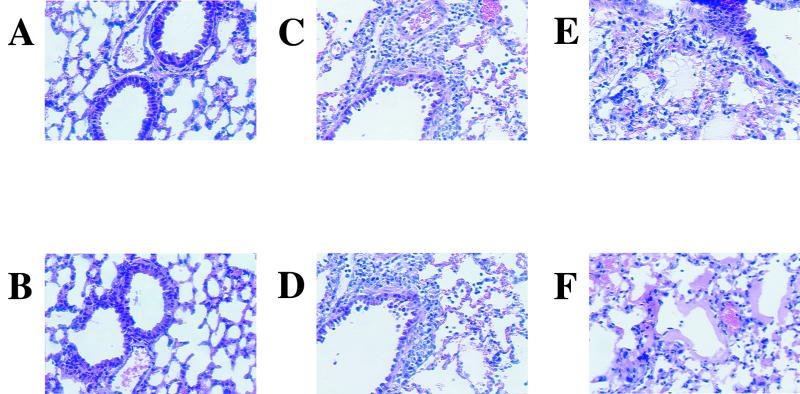

Assessment of inflammatory infiltration in the infected lung.

Macroscopic observation of KyA- and RacL11-infected lungs revealed a much more extensive inflammatory response following RacL11 infection (data not shown). The consolidation involved more than 90% of the total lung tissue compared to that observed following infection with KyA. Although inflammation was present in KyA-infected lungs compared to uninfected lungs, it encompassed only approximately 10 to 20% of the total lung. Histological analysis of infected lungs confirmed these observations. Figure 2A and B show the typical appearance of uninfected CBA lung tissue. On day 5 postinfection, KyA-infected lungs exhibited mild perivascular and peribronchial inflammation, consisting mostly of lymphocytes, with little or no infiltration into the alveolar spaces (Fig. 2C and D). The inflammatory cells infiltrating the RacL11-infected lung also appeared to be primarily lymphocytes (Fig. 2E and F). However, the lesion present in the RacL11-infected lung appeared much more severe, exhibiting diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) with alveolar edema and diffuse interstitial infiltration (Fig. 2E). Further, leakage of protein-rich fluid from the alveolar capillaries into the alveoli resulted in the formation of hyaline membranes lining the alveolar walls (Fig. 2F). Morphological examination and quantitation by light microscopy of cells isolated from the BAL fluid revealed that the BAL fluid of RacL11-infected mice consisted of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils (Table 1). In contrast, the infiltrating cells isolated from the BAL fluid of KyA-infected mice consisted of lymphocytes and macrophages; no neutrophils were detected (Table 1). We have observed previously that consolidation within the RacL11-infected lung was most severe when viral titers were at their lowest (days 5 and 6 postinfection). Taken together, these results suggested that fatality following RacL11 infection was likely due to severe DAD and was independent of levels of infectious virus (41).

FIG. 2.

Histological sections of infected lungs at 5 days postinfection. Lungs were infused with 10% buffered formalin and removed 5 days following mock infection (A and B) or i.n. infection with 2 × 106 PFU of KyA (C and D) or RacL11 (E and F). Paraffin sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

TABLE 1.

Cell types in the BAL fluid of KyA- and RacL11-infected lungsa

| Cell type | % of stained cells (mean ± SD) in lungs infected withb:

|

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KyA | RacL11 | ||

| Lymphocytes | 88.8 ± 2.9 | 80.2 ± 4.1 | 0.011 |

| Macrophages | 11.2 ± 2.9 | 10.2 ± 2.7 | 0.71 |

| Neutrophils | 0 | 9.6 ± 1.8 | 0.0004 |

| Eosinophils | 0 | 0 | |

Identification and quantitation of cells isolated from the BAL fluid at 5 days postinfection. Mice were infected i.n. with KyA or RacL11, and the BAL fluid was recovered on day 5 postinfection as described in Materials and Methods. Cell types were identified by standard morphological evaluation under light microscopy.

Each value is the mean of data from five separate experiments.

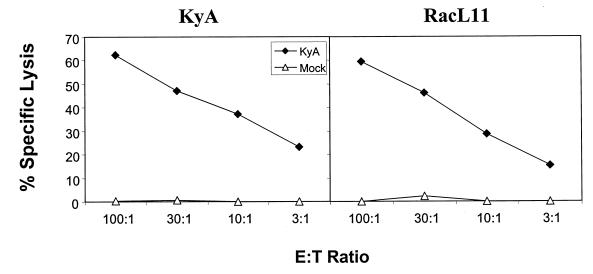

Analysis of cytolytic activity of lymphocytes isolated from infected lungs.

The severe inflammatory response in the lungs of RacL11-infected mice, present in the absence of infectious RacL11, suggested that an immunopathological response elicited by this pathogenic EHV-1 strain and likely mediated by T lymphocytes results in fatality. Although the results in Fig. 1 clearly show a similar presence of CD4 and CD8 T cells within the lungs and BAL fluid of mice infected with either KyA or RacL11, they reveal nothing regarding the function of these lymphocytes. We have previously characterized the primary and memory CTL responses elicited by KyA in the draining LN and spleen, respectively (41). To date, however, there is no information regarding CTL activity directed to the RacL11 EHV-1 strain. Furthermore, primary CTL activity isolated from the infected lung and directed against either KyA or RacL11 has not been demonstrated. When lymphocytes were isolated by enzymatic digestion from the entire lung, cultured for 3 days in vitro, and tested against EHV-1-infected targets, the primary CTL responses elicited by KyA and RacL11 were identical (Fig. 3). Further, when the cytolytic activity of lymphocytes isolated from the BAL fluid at 5 days postinfection was assessed, the primary EHV-1-specific CTL responses were also very similar. The percent specific lysis at an effector-to-target ratio of 30:1 was 32 and 36% for the BAL fluid from KyA- and RacL11-infected mice, respectively (data not shown). In a previous report (41), it was observed that KyA elicited a vigorous primary CTL response in the draining mediastinal LN but not in the draining cervical LN, even though the cervical LN drains the nasal turbinates, an important site for initial EHV-1 replication (7). Identical findings were observed following infection with the pathogenic RacL11 strain (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that, by all parameters tested, the primary RacL11-specific CTL response in the draining LN and lung is identical to that observed following infection with the attenuated EHV-1 strain KyA.

FIG. 3.

Cytolytic activity isolated from the lungs of KyA- and RacL11-infected mice. CBA mice were infected i.n. with 2 × 106 PFU of KyA or RacL11. On day 5 postinfection, the lungs were removed and lymphocytes were isolated by collagenase-DNase digestion as previously described. The resulting lymphocytes were cultured in complete RPMI for 3 days at 37°C in 5% CO2 as described in Materials and Methods. Cytolytic activity was measured in a standard 4-h 51Cr release assay using mock-infected (▵) or KyA-infected (⧫) mouse fibroblasts as targets. Each effector-to-target (E:T) ratio was assayed in triplicate. The spontaneous release never exceeded 20%, and the variability among the specific-lysis values of triplicate cultures did not exceed 5%.

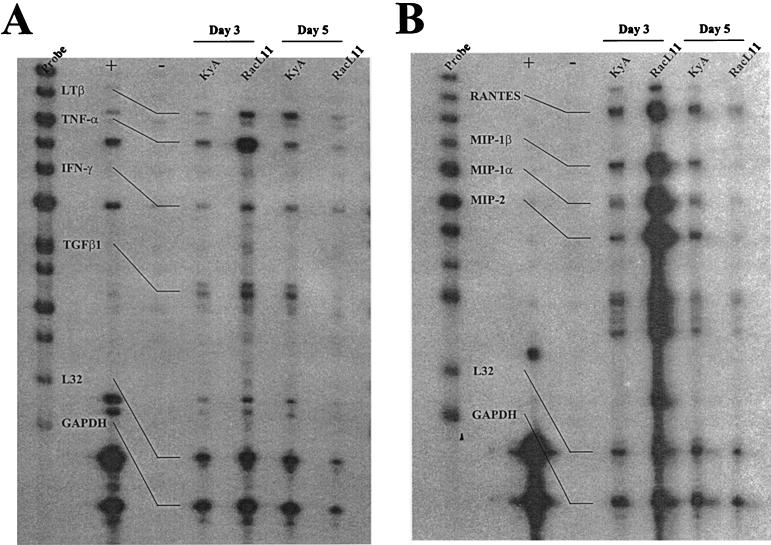

Analysis of cytokine transcripts in the infected lung.

The identical kinetics of viral clearance and the striking similarity of the primary CTL responses following RacL11 infection and KyA infection suggest that the massive inflammatory response within the RacL11-infected lung may reflect a difference in the profile of cytokines elicited by pathogenic versus attenuated EHV-1. RNase protection assays were performed to identify differences between the profiles of specific proinflammatory cytokines elicited by these two biologically distinct EHV-1 strains. RNase protection assays analyzing RNA isolated from the entire lung on days 3 and 5 postinfection revealed equivalent amounts of transcripts specific for interleukin 10 (IL-10) and the proinflammatory cytokines IL-15, IL-6, and gamma interferon in KyA- and RacL11-infected lungs (data not shown). However, when RNA isolated from BAL fluid on days 3 and 5 was analyzed, much higher levels of transcripts specific for the proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (Fig. 4A) and the beta chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α), MIP-1β, and MIP-2 (Fig. 4B) were detected on day 3 for RacL11-infected mice. Quantitation of results from four separate experiments demonstrated a consistent upregulation of MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and MIP-2 transcripts relative to the housekeeping gene L32 in EHV-1 RacL11-infected lungs (Table 2). In all four experiments, the levels of MIP transcripts from RacL11-infected mice were above the levels of L32 transcripts. In contrast, the levels of transcripts of all three MIP chemokines from KyA-infected lungs were consistently below the levels of L32 transcripts. MIP transcript levels in KyA- and RacL11-infected mice, calculated as percentages of L32 transcript levels, were compared, and the levels of MIP transcripts in RacL11-infected mice ranged from ∼2- to ∼7-fold greater than those in KyA-infected mice (Table 2). Interestingly, the levels of MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and MIP-2 transcripts isolated from the BAL fluid of RacL11-infected mice decreased by day 5 postinfection, while the levels in KyA-infected mice remained relatively unchanged (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that a rapid and vigorous production of these proinflammatory chemokines plays a major role in recruiting the massive inflammatory infiltration present in RacL11-infected lungs.

FIG. 4.

Detection of cytokine mRNA by RNase protection analysis. CBA mice were infected i.n. with 2 × 106 PFU of KyA or RacL11. On days 3 and 5 postinfection the mice were sacrificed, and BAL fluid was obtained as described in Materials and Methods. Total RNA was isolated from the BAL fluid by using the TRIZOL reagent (Life Technologies) as described in Materials and Methods. 32P-labeled probes specific for various cytokine mRNA species were generated by in vitro transcription using the probe sets mCK-2b (A) and mCK-5 (B) (RNase protection assay kit; PharMingen). RNase protection analysis was carried out according to the manufacturer's protocol. Control lanes included the labeled probes alone, pooled mouse RNA (+), and yeast tRNA (−).

TABLE 2.

Quantitation of RNase-protected transcripts

| Expt no. | Transcript | Levela in mice infected with:

|

Fold expressionb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RacL11 | KyA | |||

| 1 | MIP-1β | 96c | 42c | 2.2 |

| MIP-1α | 137 | 33 | 4.1 | |

| MIP-2 | 170 | 33 | 5.1 | |

| 2 | MIP-1β | 115 | 34 | 3.3 |

| MIP-1α | 180 | 29 | 6.2 | |

| MIP-2 | 232 | 32 | 7.2 | |

| 3 | MIP-1β | 143 | 51 | 2.8 |

| MIP-1α | 112 | 23 | 4.8 | |

| MIP-2 | 188 | 31 | 6.0 | |

| 4 | MIP-1β | 147 | 42 | 3.5 |

| MIP-1α | 128 | 21 | 6.0 | |

| MIP-2 | 193 | 32 | 6.0 | |

Expressed as a percentage of the L32 transcript level. The integrated density of each RNase-protected band was determined as described in Materials and Methods.

Calculated as the fold increase in RacL11-specific transcript levels relative to KyA-specific transcript levels.

The significance of the difference between the mean values of each chemokine species in KyA- and RacL11-infected mice was determined by the Student two-tailed t test. The P values for MIP-1β, MIP-1α, and MIP-2 were all <0.005.

DISCUSSION

Natural infections of horses with EHV-1 are associated with distinctive immunopathology of the upper respiratory tract and pathognomonic clinical signs (5). However, infection with the EHV-1 vaccine candidate strain KyA exhibits none of these signs and protects equines against subsequent infection with pathogenic, clinical isolates of EHV-1 (28). This difference between the host responses to the two viral strains suggested that the respiratory tract disease was due to immunopathological changes induced by clinical isolates rather than to differences between the immune responses to the two strains.

In CBA (H-2k) mice, clinical signs reminiscent of those in the equine are observed in response to infection with the pathogenic strain RacL11. However, the pathogenic strain RacL11 and the attenuated strain KyA reach similar levels of infectious progeny in the infected lung (41) and induce similar CD8+ T-cell responses (this study). Importantly, the two virus strains are cleared with identical kinetics, indicating that the severe clinical signs and fatality following RacL11 infection are not due specifically to viral load, but instead likely represent an immunopathological response by the host to the pathogenic strain. Further, both strains induce the infiltration of similar numbers and ratios of CD4 and CD8 T cells and induce identical EHV-1-specific CTL responses within the lung, BAL fluid, and draining LN. Therefore, the clinical outcome of RacL11 infection is not due to virus load or to the failure of the virus to induce a humoral (48) or cell-mediated immune response (41). The intense inflammatory response and DAD associated with RacL11 infection suggest that this strain has the ability to induce damaging cytokine species within the lung.

RNase protection analysis of transcripts isolated from the entire lung, either by physical grinding or by enzymatic digestion, revealed no obvious differences in the cytokines produced in the lung following infection with either strain (data not shown). However, when mRNA was isolated from the BAL fluid, the levels of MIP-1α, MIP-1β, MIP-2, and TNF-α transcripts on day 3 postinfection were much greater in response to RacL11 than to KyA. Early studies reported proinflammatory properties associated with these chemokines (16, 17, 39). Subsequent studies have implicated MIP-1α and MIP-1β in a variety of inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory muscle disease (1), herpes stromal keratitis (41), alcoholic hepatitis (3), and pulmonary inflammation (18, 26). Similarly, an important role for MIP-2 in pulmonary sepsis and interstitial lung disease has been demonstrated (18, 23, 45). The chemotactic properties of MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and MIP-2 for neutrophils (16, 39, 44) and monocytes (18, 43) correlate with the presence of both monocytes and neutrophils in the BAL fluid isolated from RacL11-infected lungs at 5 days postinfection. Interestingly, the levels of MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and MIP-2 transcripts are actually much lower in RacL11-infected lungs 5 days postinfection than in KyA-infected lungs. The downregulation of chemokine production by day 5 occurs when cellular infiltration is most severe and likely reflects no further need to recruit neutrophils and monocytes.

Infection of CBA mice with the pathogenic RacL11 EHV-1 strain results in primarily a lymphocytic and neutrophilic interstitial pneumonia in contrast to the lung eosinophilia observed following infection of the mouse with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (25, 33, 34, 38). The involvement of eosinophils following RSV infection of the lung is thought to be closely linked to the production of eosinophilic factors including RANTES and IL-5 (25, 38). Although RANTES transcripts are produced at slightly higher levels in RacL11-infected lungs than in KyA-infected lungs (Fig. 4), no appreciable differences between the levels of IL-5 transcripts were detected (data not shown).

Previous studies have demonstrated the induction of MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and MIP-2 expression by stimulation with TNF-α (8, 19, 20). The results in Fig. 4A are in agreement with this reported observation and show a concurrent upregulation of TNF-α transcripts on day 3 postinfection in RacL11-infected mice. Taken together, the results presented here suggest that proinflammatory MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and MIP-2 are produced at high levels in response to RacL11 by day 3 postinfection and are downregulated by day 5, when the inflammatory infiltration and resulting tissue damage are severe.

A clear distinction between the levels of virus in the lungs and the immunopathological destruction observed was shown recently in a study of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) pneumonia in mice (2). It was shown that inhibition of the inducible form of nitric oxide synthetase (NOS2) reduced the immunopathology associated with pneumonia to the extent that mice survived normally lethal doses. Interestingly, the levels of HSV-1 recovered from infected lungs in mice receiving the specific inhibitor were significantly greater than those from untreated controls. Therefore, NOS2 and nitric oxide itself appear to be important for HSV-1 clearance from the lung but also have a detrimental effect, inducing the immunopathological changes associated with lethal pneumonia. It is likely that the response to EHV-1 in the lung walks the fine line between elimination of infection and induction of damaging pathology.

If the difference between the responses to KyA and RacL11 cannot be explained by differences in viral load in the lung, then RacL11 must encode a protein(s) important in eliciting the immunopathology observed. Sequence analysis of EHV-1 KyA revealed a number of deletions within open reading frames (ORFs) in the viral genome. Deletions within the unique short segment of the genome include the viral envelope glycoproteins gI and gE, an ORF encoding a 10-kDa protein (21), and a large deletion in the EUS4 ORF (15). Deletions within the unique long (UL) region of the genome include an internal in-frame deletion within the EICP0 gene (9), a 1,283-bp deletion near the UL terminus (46, 47), and a 1,207-bp deletion located 5′ to the glycoprotein C ORF (29). Presently, it is not clear which of these gene products is associated with the immunopathology observed in mice or equines. However, deletion of the ORFs encoding gI and gE rendered a pathogenic strain of EHV-1 avirulent in horses, implicating these two viral glycoproteins as potential mediators of immunopathology (27). The fact that EHV-1 RacL11 is cleared from the lungs as efficiently as KyA suggests that one or more of these viral components is associated with the induction of these proinflammatory mediators associated with EHV-1 pathogenicity. Studies to address this question are in progress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Suzanne Zavecz, Marie Bruce, and Deborah Dempsey for excellent technical assistance and H. van der Heyde for critical reading of the manuscript.

This study was supported in part by research grant AI 22001 (D.J.O.) and by funds made available through Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica GmbH, Ingleheim, Germany.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams E M, Kirkley J, Eidelman G, Dohlman J, Plotz P H. The predominance of beta (CC) chemokine transcripts in idiopathic inflammatory muscle diseases. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1997;109:275–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler H, Beland J L, Del-Pan N C, Kobzik L, Brewer J P, Martin T R, Rimm I J. Suppression of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1)-induced pneumonia in mice by inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS, NOS2) J Exp Med. 1997;185:1533–1540. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afford S C, Fisher N C, Neil D A, Fear J, Brun P, Hubscher S G, Adams D H. Distinct patterns of chemokine expression are associated with leukocyte recruitment in alcoholic hepatitis and alcoholic cirrhosis. J Pathol. 1998;186:82–89. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199809)186:1<82::AID-PATH151>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alber D G, Greensill J, Killington R A, Stokes A. Role of T-cells, virus neutralizing antibodies and complemented-mediated antibody lysis in the immune response against equine herpesvirus type-1 (EHV-1) infection of C3H (H-2k) and BALB/c (H-2d) mice. Res Vet Sci. 1995;59:205–213. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(95)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen G P, Bryans J T. Molecular epizootiology, pathogenesis, and prophylaxis of equine herpesvirus-1 infections. Prog Vet Microbiol Immunol. 1986;2:78–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen G P, Kydd J H, Slater J D, Smith K C. Advances in understanding of the pathogenesis, epidemiology and immunological control of equine herpesvirus abortion. In: Wernery U, Wade J F, Mumford J A, Kaaden O-R, editors. Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference of Equine Infectious Diseases. R & W Publishers, Newmarket, United Kingdom. 1998. pp. 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Awan A R, Chong Y C, Field H J. The pathogenesis of equine herpesvirus type 1 in the mouse: a new model for studying host responses to the infection. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:1131–1140. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-5-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bliss S K, Marshall A J, Zhang Y, Denkers E Y. Human polymorphonuclear leukocytes produce IL-12, TNF-alpha, and the chemokines macrophage-inflammatory protein-1 alpha and -1 beta in response to Toxoplasma gondii antigens. J Immunol. 1999;162:7369–7375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowles D E, Holden V R, Zhao Y, O'Callaghan D J. The ICP0 protein of equine herpesvirus 1 is an early protein that independently transactivates expression of all classes of viral promoters. J Virol. 1997;71:4904–4914. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.4904-4914.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryans J T, Allen G P. On immunity to disease caused by equine herpesvirus-1. Am Vet Med Assoc. 1969;155:294–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burki F, Rossmanith W, Nowotny N, Pallan C, Mostl K, Lussy H. Viremia and abortions are not prevented by two commercial equine herpesvirus-1 vaccines after experimental challenge of horses. Vet Q. 1990;12:80–86. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1990.9694249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burrows R, Goodridge D, Denyer M S. Trials of an inactivated equid herpesvirus-1 vaccine: challenge with a subtype-1 virus. Vet Res. 1984;114:369–374. doi: 10.1136/vr.114.15.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrol C L, Westbury H A. Isolation of equine herpesvirus type 1 from the brain of a horse affected with paresis. Aust Vet J. 1985;62:345–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1985.tb07660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colle C F, III, Flowers C C, O'Callaghan D J. Open reading frames encoding a protein kinase, homolog of glycoprotein gX of pseudorabies virus, and a novel glycoprotein map within the unique short segment of equine herpesvirus type 1. Virology. 1992;188:545–557. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90509-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colle C F, III, O'Callaghan D J. Transcriptional analyses of the unique short segment of EHV-1 strain Kentucky A. Virus Genes. 1995;9:257–268. doi: 10.1007/BF01702881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davatelis G, Tekamp-Olson P, Wolpe S D. Cloning and characterization of cDNA for murine macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP): a novel monokine with inflammatory and chemokinetic properties. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1939–1944. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.6.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davatelis G, Wolpe S D, Sherry B, Dayer J M, Chicheportiche R, Cerami A. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1: a prostaglandin-independent endogenous pyrogen. Science. 1989;243:1066–1068. doi: 10.1126/science.2646711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Driscoll K E. Macrophage inflammatory proteins: biology and role in pulmonary inflammation. Exp Lung Res. 1994;20:473–490. doi: 10.3109/01902149409031733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Driscoll K E, Hassenbein D G, Carter J. Macrophage inflammatory proteins 1 and 2: expression by rat alveolar macrophages, fibroblasts, and epithelial cells and in rat lung after mineral dust exposures. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1993;8:311–328. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/8.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dudley D J, Spencer S, Edwin S, Mitchell M D. Regulation of human decidual cell macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha (MIP-1α) production by inflammatory cytokines. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1995;34:231–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1995.tb00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flowers C C, O'Callaghan D J. The equine herpesvirus type 1 (EHV-1) homolog of herpes simplex virus type 1 US9 and the nature of a major deletion within the unique short segment of the EHV-1 KyA strain genome. Virology. 1992;190:307–315. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91217-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hannant D, Jessett D M, O'Neill T, Dolby C A, Cook R F, Mumford J A. Responses of ponies to equid herpesvirus-1 ISCOM vaccination and challenge with virus of the homologous strain. Res Vet Sci. 1993;54:299–305. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(93)90126-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang S, Paulauskis J D, Godleski J J, Kobzik L. Expression of macrophage inflammatory protein-2 and KC mRNA in pulmonary inflammation. Am J Pathol. 1992;141:981–988. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson T A, Kendrick J W. Paralysis of horses associated with equine herpesvirus 1 infection. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1971;158:1351–1357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson T R, Johnson J E, Roberts S R, Wertz G W, Parker R A, Graham B S. Priming with secreted glycoprotein G of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) augments interleukin-5 production and tissue eosinophilia after RSV challenge. J Virol. 1998;72:2871–2880. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2871-2880.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnston C J, Finkelstein J N, Gelein R, Oberdorster G. Pulmonary cytokine and chemokine mRNA levels after inhalation of lipopolysaccharide in C57BL/6 mice. Toxicol Sci. 1998;46:300–307. doi: 10.1006/toxs.1998.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumura T, Kondo T, Sugita S, Damiani A M, O'Callaghan D J, Imagawa H. An equine herpesvirus type 1 recombinant with a deletion in the gE and gI genes is avirulent in young horses. Virology. 1998;242:68–79. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumura T, O'Callaghan D J, Kondo T, Kamada M. Lack of virulence of the murine fibroblast adapted strain, Kentucky A (KyA), of equine herpesvirus type 1 (EHV-1) in young horses. Vet Microbiol. 1996;48:353–365. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(09)59999-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsumura T, Smith R H, O'Callaghan D J. DNA sequence and transcriptional analyses of the region of the equine herpesvirus type 1 Kentucky A strain genome encoding glycoprotein C. Virology. 1993;193:910–923. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer H, Thein P, Hubert P. Characterization of two equine herpesvirus (EHV) isolates associated with neurological disorders in horses. Zentbl Vetmed Reihe B. 1987;34:545–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1987.tb00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mumford J A, Hannant D A, Jessett D M, O'Neill T, Smith K C, Ostlund E N. Abortogenic and neurological disease caused by infection with equid herpesvirus-1. In: Nakajima H, Plowright W, editors. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference of Equine Infectious Diseases. R & W Publishers, Newmarket, United Kingdom. 1995. pp. 261–275. [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Callaghan D J, Osterrieder N. Equine herpesviruses. In: Webster R, Granoff A, editors. Encyclopedia of virology. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press Ltd.; 1999. pp. 508–515. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olszewska-Pazdrak B, Casola A, Saito T, Alam R, Crowe S E, Mei F, Ogra P L, Garofalo R P. Cell-specific expression of RANTES, MCP-1, and MIP-1α by lower airway epithelial cells and eosinophils infected with respiratory syncytial virus. J Virol. 1998;72:4756–4764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4756-4764.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olszewska-Pazdrak B, Pazdrak K, Ogra P L, Garofalo R P. Respiratory syncytial virus-infected pulmonary epithelial cells induce eosinophil degranulation by a CD18-mediated mechanism. J Immunol. 1998;160:4889–4895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osterrieder N, Neubauer A, Brandmuller C, Kaaden O-R, O'Callaghan D J. The equine herpesvirus 1 IR6 protein influences virus growth at elevated temperature and is a major determinant of virulence. Virology. 1996;226:243–252. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osterrieder N, Neubauer A, Brandmuller C, Kaaden O-R, O'Callaghan D J. The equine herpesvirus 1 IR6 protein that colocalizes with nuclear lamin is involved in nucleocapsid egress and migrates from cell to cell independently of virus infection. J Virol. 1998;72:9806–9817. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9806-9817.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perdue M L, Kemp M C, Randall C C, O'Callaghan D J. Studies of the molecular anatomy of the L-M strain of equine herpesvirus type 1: protein of the nucleocapsid and intact virion. Virology. 1974;59:201–216. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(74)90216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saito T, Deskin R W, Casola A, Haeberle H, Olszewska B, Ernst P B, Alam R, Ogra P L, Garofalo R. Respiratory syncytial virus induces selective production of the chemokine RANTES by upper airway epithelial cells. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:497–504. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saukkonen K, Sande S, Cioffe C. The role of cytokines in the generation of inflammation and tissue damage in experimental gram positive meningitis. J Exp Med. 1990;171:439–448. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott J C, Dutta S K, Myrup A C. In vivo harboring of equine herpesvirus-1 in leukocyte populations and subpopulations and their quantitation from experimentally infected ponies. Am J Vet Res. 1983;44:1344–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith P M, Zhang Y, Jennings S R, O'Callaghan D J. Characterization of the cytolytic T-lymphocyte response to a candidate vaccine strain of equine herpesvirus 1 in CBA mice. J Virol. 1998;72:5366–5372. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5366-5372.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su Y H, Yan X T, Oakes J E, Lausch R N. Protective antibody therapy is associated with reduced chemokine transcripts in herpes simplex virus type 1 corneal infection. J Virol. 1996;70:1277–1281. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1277-1281.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J M, Sherry B, Fivash J M, Kelvin D J, Oppenheim J J. Human recombinant macrophage inflammatory protein-1α and β and monocyte chemotactic and activating factor utilize common and unique receptors on human monocytes. J Immunol. 1993;150:3022–3028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolpe S D, Sherry B, Juers D, Davatelis G, Yurt R W, Cerami A. Identification and characterization of macrophage inflammatory protein 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:612–616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xing Z, Jordana M, Kirpalani H, Driscoll K E, Schall T J, Gauldie J. Cytokine expression by neutrophils and macrophages in vivo: endotoxin induces tumor necrosis factor alpha, macrophage inflammatory protein-2, interleukin-1 beta, and interleukin-6, but not RANTES or transforming growth factor beta 1 mRNA expression in acute lung inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;10:148–153. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.2.8110470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yalamanchili R R, O'Callaghan D J. Sequence and organization of the genomic termini of equine herpesvirus type 1. Virus Res. 1990;15:149–162. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(90)90005-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yalamanchili R R, O'Callaghan D J. Equine herpesvirus sequence near the left terminus codes for two open reading frames. Virus Res. 1990;18:109–116. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(91)90012-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Y, Smith P M, Jennings S R, O'Callaghan D J. Quantitation of virus-specific classes of antibodies following immunization of mice with attenuated equine herpesvirus 1 and viral glycoprotein D. Virology. 2000;268:482–492. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y, Smith P M, Tarbet E B, Osterrieder N, Jennings S R, O'Callaghan D J. Protective immunity against equine herpesvirus type 1 (EHV-1) infection in mice induced by recombinant EHV-1 gD. Virus Res. 1998;56:11–24. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(98)00054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]