ABSTRACT

Galactomannan (GM) testing of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid samples has become an essential tool to diagnose invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) and is part of diagnostic guidelines. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) (enzyme immunoassays [EIAs]) are commonly used, but they have a long turnaround time. In this study, we evaluated the performance of an automated chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) with BAL fluid samples. This was a multicenter retrospective study in the Netherlands and Belgium. BAL fluid samples were collected from patients with underlying hematological diseases with a suspected invasive fungal infection. Diagnosis of IPA was based on the 2020 European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)/Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium (MSGERC) consensus definitions. GM results were reported as optical density index (ODI) values. ODI cutoff values for positive results that were evaluated were 0.5, 0.8, and 1.0 for the EIA and 0.16, 0.18, and 0.20 for the CLIA. Probable IPA cases were compared with two control groups, one with no evidence of IPA and another with no IPA or possible IPA. Qualitative agreement was analyzed using Cohen’s κ, and quantitative agreement was analyzed by Spearman’s correlation. We analyzed 141 BAL fluid samples from 141 patients; 66 patients (47%) had probable IPA, and 56 cases remained probable IPA when the EIA GM result was excluded as a criterion, because they also had positive culture and/or duplicate positive PCR results. Sixty-three patients (45%) had possible IPA and 12 (8%) had no IPA. The sensitivity and specificity of the two tests were quite comparable, and the overall qualitative agreement between EIA and CLIA results was 81 to 89%. The correlation of the actual CLIA and EIA values was strong at 0.72 (95% confidence interval, 0.63 to 0.80). CLIA has similar performance, compared to the gold-standard EIA, with the benefits of faster turnaround because batching is not required. Therefore, CLIA can be used as an alternative GM assay for BAL fluid samples.

KEYWORDS: galactomannan, chemiluminescence assay, invasive aspergillosis, GM

INTRODUCTION

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) in patients with hematological malignancies and recipients of stem cell transplants has substantial overall and attributable mortality rates (1). The inability to diagnose and treat IPA promptly has contributed to poor outcomes in the past, as conventional microscopy and culture lack sensitivity, and cultures may take up to 7 days to grow. Our ability to diagnose IPA has improved over the years with the introduction of galactomannan (GM) testing with serum samples and later with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid samples from patients with lesions on computed tomography (CT) consistent with invasive fungal disease (e.g., nodules, halo sign, cavities, or air crescents) (2, 3). In addition, several centers now use molecular assays for the detection of Aspergillus DNA directly in clinical samples, including BAL fluid samples (4).

A major drawback of the most commonly used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) for the detection of GM is the relatively long turnaround times, although the time needed to perform the GM assay is only 3 h. Because many clinical microbiology laboratories batch samples to increase cost-effectiveness, the assay is often performed only two or three times each week. In addition, laboratories may not perform the assay locally and need to send samples to a reference laboratory, which further increases the time to result. Although the time needed to perform the GM assay is only 3 h, the aforementioned delays compromise the ability to diagnose IPA early, as well as the benefits of improved survival with early treatment (5, 6).

To overcome the long turnaround time, point-of-care tests to detect Aspergillus antigen (Ag) have been developed. Currently, two commercial lateral flow tests (LFTs) are available for the detection of Aspergillus Ag in BAL fluid samples (7–10). These assays require only up to 45 min, which would dramatically shorten the time to diagnose IPA (5). Furthermore, single samples can be tested, and thus batching of samples is not required. Quantifying the fungal load remains difficult with LFTs; ideally, a digital reader would be used to interpret the results (8).

Recently, several additional assays have become available, i.e., Euroimmun Aspergillus Ag ELISA (11, 12), IMMY GM enzyme immunoassay (EIA), and Aspergillus GM Ag VirClia monotest (Vircell) (13). This VirClia monotest detects GM by an automated chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) and can be used on individual serum, plasma, and BAL fluid samples. In this retrospective study, we evaluate the performance of the new GM VirClia assay with BAL fluid samples to diagnose IPA among hematological patients receiving intensive treatment or following allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patient population.

Fifty-two BAL fluid samples from patients with a hematological disease or after alloSCT were collected in the Radboud University Medical Center between January 2017 and July 2021 during routine patient care. In addition, samples from 89 hematological patients were collected in eight other centers in the context of two observational studies (Azole Resistance Management [AzorMan] study [ClinicalTrials registration number NCT03121235] and Azole Resistance PCR Optimization Study [ARPOS] [Erasmus Medical Center, registration number NL62004.078.17]) between April 2017 and March 2021. Informed consent was provided by the study participants prior to sampling of BAL fluid. The participants agreed to the use of their body material for research purposes outside the scope of the original trials. Patients were classified, based on the 2020 European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)/Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium (MSGERC) consensus definitions, as having proven IPA, probable IPA, or possible IPA (14). Patients without clinical features suspicious for fungal infections and thus not fulfilling the IPA classifications were classified as having no IPA.

Investigations to diagnose IPA.

BAL was performed as part of routine clinical care for patients with a suspected pulmonary infection, and residual BAL fluid was stored at −70°C until further testing. Tests performed during routine medical care included direct microscopy, fungal culture, Aspergillus species PCR, Aspergillus fumigatus PCR, and GM testing using the Platelia Aspergillus Ag assay (EIA). Two PCR methods were employed for the detection of Aspergillus, namely, an in-house PCR targeting the 28S rRNA and the AsperGenius PCR kit (15, 16). Aspergillus PCR testing of blood samples was not performed. EIA optical density index (ODI) results were rounded to 1 decimal place. Samples above the quantifiable EIA ODI ranges were truncated at the highest quantifiable ODI. The EIA results were evaluated using three ODI cutoff values (1.0, 0.8, and 0.5) that are frequently used in clinical practice, with the higher cutoff value being more specific and the lower being more sensitive.

BAL fluid samples were tested centrally with the CLIA at two centers (Radboud University Medical Center and Erasmus Medical Center), based on where the samples were stored. CLIA was performed using the VirClia automated chemiluminescence system, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, with samples that had been stored at a temperature of −70°C. The technician performing the assay was blinded with respect to the results obtained from other mycological tests. The results of CLIA were analyzed using three cutoff values for positivity, i.e., (i) the ODI cutoff value for positivity specified by the manufacturer (ODI of ≥0.200), (ii) the cutoff value for dubious positivity specified by the manufacturer (ODI of ≥0.160), and (iii) an additional cutoff value of ≥0.180, which was selected ad hoc. Because the goal of the study was to compare the diagnostic characteristics of the new assay, its results were not used for classification of patients according the 2020 EORTC/MSGERC criteria. Because the Aspergillus GM immunoenzymatic sandwich microplate assay (Platelia; Bio-Rad) is part of the mycological criteria in the EORTC//MSGERC consensus definitions, we performed a separate analysis in which the results of Platelia testing were excluded from the mycological criteria to avoid incorporation bias. Indeed, including the Platelia test in the gold-standard definition would increase the performance of this test. Therefore, in this analysis only the culture and PCR results were used as mycological criteria.

Statistics.

Baseline characteristics were analyzed for comparison by using SPSS version 28.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The sensitivity and specificity of the CLIA results were calculated using the CLIA cutoff values (ODI values of ≥0.160, ≥0.180, and ≥0.200) mentioned above and compared with the result of the EORTC//MSGERC classification, using the EIA ODI cutoff values of ≥1.0, ≥0.8, and ≥0.5. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and figures were generated in GraphPad Prism v9. To measure the qualitative agreement between the CLIA and EIA results, the Cohen’s κ coefficient (with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) was used for categorical classifications; κ values of >0.8 were defined as representing almost perfect agreement, while values between 0.61 and 0.80 represented substantial agreement (17). The quantitative agreement between CLIA and EIA results was calculated with Spearman’s correlation in GraphPad Prism; R values of 0.40 to 0.59 were defined as indicating moderate correlation, 0.60 to 0.79 strong correlation, and 0.80 to 1.0 very strong correlation.

RESULTS

Population.

A total of 141 BAL fluid samples from 141 patients could be analyzed. The median age of the patients was 64 years (interquartile range [IQR], 55 to 70 years), and acute myeloid leukemia was the most common underlying disease (Table 1). There were no cases of proven IPA, while 66 cases were classified as probable IPA and 63 as possible IPA. Twelve cases could not be classified as probable IPA or possible IPA according to 2020 EORTC/MSGERC criteria and therefore were classified as no IPA. When GM was excluded as a mycological criterion, 56 (85%) of 66 cases remained classified as probable IPA because a positive culture result (n = 20) and/or duplicate positive PCR results (n = 46) were present. A. fumigatus was cultured in 16 cases, Aspergillus niger in 2 cases, and Aspergillus flavus in 1 case, while another patient had a mixed culture of A. fumigatus and A. flavus.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Parameter | Data for patients with: |

Overall finding (n = 141) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proven/probable IPA (n = 66) (%)a | Possible IPA (n = 63)a | No IPA (n = 12) | ||

| Male (no. [%]) | 41 (62) | 48 (76) | 10 (83) | 99 (70) |

| Age (median [IQR]) (yr) | 65 (59–69) | 64 (51–70) | 61 (52–67) | 64 (55–70) |

| Underlying disease (no. [%])b | ||||

| AML | 36 (55) | 31 (49) | 3 (25) | 70 (50) |

| ALL | 6 (9) | 3 (5) | 1 (5) | 10 (7) |

| Lymphoma | 5 (8) | 7 (11) | 4 (33) | 16 (11) |

| Multiple myeloma | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | 2 (17) | 6 (4) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 7 (11) | 8 (13) | 1 (8) | 16 (11) |

| Other | 11 (17) | 11 (17) | 1 (8) | 23 (16) |

| AlloSCT | 20 (30) | 12 (19) | 3 (25) | 35 (25) |

| AutoSCT | 2 (3) | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 5 (4) |

| Mycological evidence | ||||

| Positive fungal culture with BAL fluid sample (no. [%]) | 20 (30) | 0 | 0 | 20 (30) |

| Positive Aspergillus PCR (no. [%])c | 46 (70) | 0 | 0 | 46 (69) |

| GM EIA ODI for serum sample (median [IQR])d | 0.2 (0.1–0.58) | 0.1 (0.07–0.10) | 0.01 (0.06–0.10) | 0.1 (0.1–0.3) |

| GM EIA ODI for BAL fluid sample (median [IQR]) | 1.03 (0.33–5.15) | 0.19 (0.1–0.3) | 0.15 (0.09–0.29) | 0.21 (0.10–0.95) |

| Aspergillus GM CLIA ODI for BAL fluid sample (median [IQR]) | 0.34 (0.08–3.61) | 0.05 (0.02–0.08) | 0.05 (0.03–0.13) | 0.08 (0.03–0.54) |

Classified based on the 2020 EORTC/MSGERC criteria.

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; autoSCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; EIA, Platelia GM assay; CLIA, VirClia GM assay.

Only duplicate PCR positive results were counted (single PCR results were positive in 2 probable IPA casus and 6 possible IPA cases).

Serum samples with the highest GM ODI values within 7 days of BAL were included.

Sensitivity, specificity, and concordance of EIA and CLIA GM assays.

In total, 42 samples had EIA ODI values of ≥1.0, and 50 samples had CLIA ODI values of ≥0.200. There were 9 samples above the quantifiable EIA ODI range, and thus values were truncated at the highest quantifiable ODI. Positivity rates with EIA ODI values of ≥1.0 were 42/66 cases (64%), 0/63 cases (0%), and 0/12 cases (0%) for patients with probable IPA, possible IPA, and no IPA, respectively. Rates with EIA ODI values of ≥0.5 were 51/66 cases (77%), 11/63 cases (17%), and 1/12 cases (8%) for patients with probable IPA, possible IPA, and no IPA, respectively. Rates with CLIA ODI values of ≥0.200 were 42/66 cases (64%), 8/63 cases (13%), and 0/12 cases (0%) for patients with probable IPA, possible IPA, and no IPA, respectively. When the Platelia EIA GM test results were excluded from the gold-standard definition, the positivity rates for EIA and CLIA were quite comparable; positivity rates with Platelia EIA ODI values of ≥1.0 were 32/56 cases (57%), 10/73 cases (14%), and 0/12 cases (0%) for probable IPA, possible IPA, and no IPA, respectively, while the positivity rates with CLIA ODI values of ≥0.200 were 34/56 cases (61%), 16/73 cases (22%), and 0/12 cases (0%), respectively.

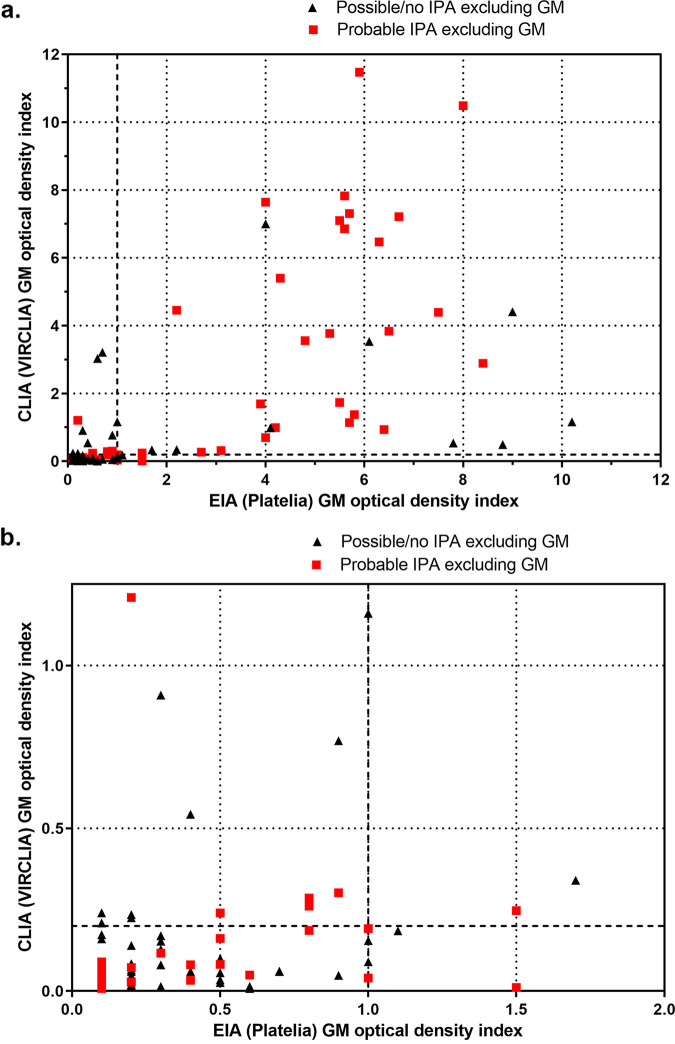

The sensitivity and specificity of EIA and CLIA were compared using the three ODI cutoff values for both tests by classifying the patients according to the 2020 EORTC/MSGERC criteria, including the Platelia EIA GM in the criteria (Table 2). The sensitivity and specificity were also calculated by using patients with no IPA as controls, as well as by using both patients with possible IPA and those with no IPA as controls. Again, the sensitivities of EIA and CLIA were quite comparable (Table 2). ROC curves for probable IPA in comparison with controls defined as patients with no IPA and controls defined as patients with no IPA or possible IPA can be found in Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material. The areas under the ROC curves were between 0.75 and 0.87, indicating good discriminative power (Table 2). The overall qualitative agreement between EIA and CLIA was between 81% and 89% using the three defined cutoff values, with Cohen’s κ values between 0.62 and 0.77, indicating substantial correlation (Table 3). The Spearman’s correlation for quantitative correlation between EIA and CLIA ODI values was 0.72 (95% CI, 0.63 to 0.80 [P < 0.001]), indicating strong correlation. The absolute ODI values for EIA and CLIA are displayed in Fig. 1.

TABLE 2.

Performance of the VirClia and Platelia GM Ag assays

| Comparison and cutoff value(s)a | Area under ROC curve (95% CI) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probable IPA vs no IPA | |||

| GM CLIA ODI of ≥0.160 | 0.80 (0.70–0.89) | 68 (56–78) | 100 (76–100) |

| GM CLIA ODI of ≥0.180 | 66 (55–77) | 100 (76–100) | |

| GM CLIA ODI of ≥0.200 | 61 (50–73) | 100 (76–100) | |

| GM EIA ODI of ≥0.5 | 0.87 (0.79–0.95) | 74 (64–84) | 92 (65–100) |

| GM EIA ODI of ≥0.8 | 69 (58–79) | 100 (76–100) | |

| GM EIA ODI of ≥1.0 | 63 (52–74) | 100 (76–100) | |

| Probable IPA vs possible IPA plus no IPA | |||

| GM CLIA ODI of ≥0.160 | 0.81 (0.73–0.88) | 68 (56–78) | 82 (74–92) |

| GM CLIA ODI of ≥0.180 | 66 (55–77) | 86 (79–94) | |

| GM CLIA ODI of ≥0.200 | 61 (50–73) | 86 (79–94) | |

| GM EIA ODI of ≥0.5 | 0.86 (0.80–0.93) | 74 (64–84) | 81 (73–90) |

| GM EIA ODI of ≥0.8 | 69 (58–79) | 97 (90–99) | |

| GM EIA ODI of ≥1.0 | 63 (52–74) | 100 (95–100) | |

| Probable IPA vs no IPA with GM excluded | |||

| GM CLIA ODI of ≥0.160 | 0.77 (0.67–0.88) | 67 (54–78) | 92 (65–100) |

| GM CLIA ODI of ≥0.180 | 65 (52–76) | 100 (76–100) | |

| GM CLIA ODI of ≥0.200 | 63 (50–74) | 100 (76–100) | |

| GM EIA ODI of ≥0.5 | 0.85 (0.76–0.94) | 72 (59–82) | 92 (65–100) |

| GM EIA ODI of ≥0.8 | 65 (52–76) | 100 (76–100) | |

| GM EIA ODI of ≥1.0 | 58 (45–70) | 100 (76–100) | |

| Probable IPA vs possible IPA plus no IPA with GM excluded | |||

| GM CLIA ODI of ≥0.160 | 0.75 (0.67–0.84) | 67 (54–78) | 79 (67–85) |

| GM CLIA ODI of ≥0.180 | 65 (52–76) | 82 (73–89) | |

| GM CLIA ODI of ≥0.200 | 63 (50–74) | 82 (73–89) | |

| GM EIA ODI of ≥0.5 | 0.77 (0.69–0.86) | 71 (59–82) | 73 (63–81) |

| GM EIA ODI of ≥0.8 | 64 (51–76) | 86 (77–91) | |

| GM EIA ODI of ≥1.0 | 57 (44–69) | 88 (80–93) | |

| GM EIA ODI of ≥1.0 and GM CLIA ODI of ≥0.200 | 52 (39–65) | 92 (85–96) | |

| GM EIA ODI of ≥1.0 or GM CLIA ODI of ≥0.200 | 67 (54–78) | 77 (68–85) |

The performance of the Platelia GM assay (EIA) and the VirClia GM assay (CLIA) were calculated for probable IPA with controls. Controls were defined either as patients with no IPA or as patients with no IPA in combination with patients with possible IPA. Patients were classified as having proven IPA, probable IPA, possible IPA, or no IPA using the 2020 EORTC/MSGERC criteria and using the same 2020 EORTC/MSGERC criteria but with the exclusion of GM as a mycological criterion.

TABLE 3.

Qualitative agreement between the VirClia and Platelia GM assaysa

| CLIA ODI cutoff value | Agreement (% [Cohen’s κ]) with EIA ODI cutoff value of: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥1.0 | ≥0.8 | ≥0.5 | |

| ≥0.200 | 86 (0.68) | 87 (0.72) | 81 (0.60) |

| ≥0.180 | 86 (0.70) | 89 (0.77) | 83 (0.65) |

| ≥0.160 | 84 (0.65) | 87 (0.71) | 82 (0.62) |

Different ODI cutoff values were used to discriminate negative and positive results. For the VirClia GM assay (CLIA), ODI cutoff values of ≥0.200, ≥0.180, and ≥0.160 was used; for the Platelia GM assay (EIA), ODI cutoff values of ≥1, ≥0.8, and ≥0.5 were used.

FIG 1.

Comparison between VirClia and Platelia GM ODI values for 141 BAL fluid samples from patients with hematological malignancies. (a) Overview of ODI values generated by the Platelia (EIA) and VirClia (CLIA) GM assays. Patients were classified based on the EORTC/MSGERC criteria but excluding GM as a mycological criterion. (b) Detail of panel a in which we zoom in on the ODI ranges of 0.0 to 1.25 for CLIA and 0.0 to 2.0 for EIA.

Discrepant GM assay results.

Details for the 20 patients with discrepant EIA and CLIA test results, defined as a GM CLIA ODI result of ≥0.200 while the GM EIA ODI value was <1.0 or an EIA ODI value of ≥1.0 while the CLIA ODI value was <0.200, can be found in Table 4. Discrepant EIA and CLIA results using EIA ODI values of ≥0.5 to are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material (excluding patients already shown in Table 4). Fourteen patients had CLIA ODI values of ≥0.200 with EIA ODI values of <1.0. Six patients had EIA ODI values of ≥1 with CLIA ODI values of ≤0.200 (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Discrepant VirClia and Platelia GM assay resultsa

| Patient no. | Patient identification | Underlying disease | Radiological finding(s) | Serum EIA ODIb | BAL fluid results |

EORTC/MSGERC 2020 classification (excluding GM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct microscopy | Culture | Aspergillus PCR | EIA ODI | CLIA ODI | ||||||

| 1 | A013 | AML | Nodules, halo | 0.1 | Negative | Negative | Positive (single PCR) | 0.1 | 0.24 | Possible IPA |

| 2 | B004 | NK-T lymphoma | Nodules, halo | 0.1 | Negative | Negative | Negative | 0.1 | 0.209 | Possible IPA |

| 3 | A003 | MM | Nodule, halo | 0.1 | Negative | Negative | Negative | 0.2 | 0.225 | Possible IPA |

| 4 | C001 | ALL | Nodules, halo | Negative | Negative | Negative | 0.2 | 0.235 | Possible IPA | |

| 5 | D020 | CML, alloSCT | Nodule, cavity | 0.1 | Negative | A. flavus plus A. fumigatus | Positive for A. fumigatus (in duplicate) | 0.2 | 1.209 | Probable IPA |

| 6 | B021 | AML | Consolidation, ground glass | 0.1 | Negative | Negative | Negative | 0.3 | 0.909 | Possible IPA |

| 7 | E032 | AML | Nodule | Negative | Negative | Negative | 0.4 | 0.543 | Possible IPA | |

| 8 | F013 | AML | Nodule, halo | 0.2 | Negative | Positive for A. fumigatus (in duplicate) | 0.5 | 0.24 | Probable IPA | |

| 9 | E013 | AML | Nodule, halo | Negative | Negative | Negative | 0.6 | 3.03 | Possible IPA | |

| 10 | G09 | DLBC | Cavity | Negative | Negative | Negative | 0.7 | 3.21 | Possible IPA | |

| 11 | D017 | AML | Nodule | 0.2 | Negative | Negative | Positive for A. fumigatus (in duplicate) | 0.8 | 0.286 | Probable IPA |

| 12 | A014 | AML | Nodule, halo | 0.1 | Negative | Negative | Positive for A. fumigatus (in duplicate) | 0.8 | 0.261 | Probable IPA |

| 13 | D061 | Polycythemia vera, alloSCT | Nodules, halo | 0.1 | Negative | Negative | Negative | 0.9 | 0.769 | Possible IPA |

| 14 | G021 | AML | Nodule, halo | 0.1 | Negative | A. flavus | Positive for Aspergillus species (single PCR) | 0.9 | 0.302 | Probable IPA |

| 15 | E008 | AML, alloSCT | Consolidation | Negative | Negative | Negative | 1,0 | 0.09 | Probable IPA (possible IPA)c | |

| 16 | B015 | AML | Consolidation, ground glass | 0.7 | Negative | Negative | NA | 1,0 | 0.155 | Probable IPA (possible IPA)c |

| 17 | G019 | AML | Nodule | NA | Negative | Negative | Positive for A. fumigatus (in duplicate) | 1 | 0.04 | Probable IPA |

| 18 | A006 | Mantle cell lymphoma | Cavitation | 0.1 | Negative | Negative | Positive for A. fumigatus (in duplicate) | 1 | 0.192 | Probable IPA |

| 19 | E026 | AML | Nodule | 0.1 | Negative | Negative | Negative | 1.1 | 0.185 | Probable IPA (possible IPA)c |

| 20 | D003 | CLL | Nodules | 0.1 | Positive | A. fumigatus | Positive for A. fumigatus (in duplicate) | 1.5 | 0.011 | Probable IPA |

Discrepant results were defined as a VirClia GM assay (CLIA) ODI value of ≥0.200 with a Platelia GM assay (EIA) ODI value of <1.0 or an EIA ODI value of ≥1.0 with a CLIA ODI value of <0.200. AML, acute myeloid leukemia; NK-T lymphoma, natural killer T-cell lymphoma; MM, multiple myeloma; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; DLBC, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; NA, not applicable.

The highest serum EIA ODI value is shown.

For patients 15, 16, and 19, the EORTC/MSG classification changed from probable IPA to possible IPA with the exclusion of GM as a criterion.

Performance of combined CLIA and EIA testing.

The performance of the combined CLIA and EIA results was also analyzed. Again, we used probable IPA according to the consensus definitions with GM excluded as the mycological criterion for true-positive results and possible IPA or no IPA as true-negative results.

Both the EIA and CLIA results were positive in 29/56 cases (52%), 7/73 cases (10%), and 0/12 cases (0%) for those with probable IPA, possible IPA, or no IPA, respectively. Sensitivity (52%) and specificity (92%) for the combination of the two assays were comparable to those for a single positive test.

Also, the performance did not improve when EIA ODI of ≥1.0 or CLIA ODI of ≥0.200 was used as the criterion for positivity, because the increased sensitivity was compensated by a lower specificity. In total, 54 patients had an EIA ODI value of ≥1.0 or a CLIA ODI value of ≥0.200. Positivity rates for the combination of EIA ODI of ≥1.0 and CLIA ODI of ≥0.200 were 36/56 cases (64%), 18/73 cases (25%), and 0/12 cases (0%) for patients with probable IPA, possible IPA, or no IPA, respectively; this resulted in a sensitivity of 67% and a specificity of 77%.

DISCUSSION

We evaluated the performance of a new CLIA to detect GM in BAL fluid samples and to diagnose IPA among hematological patients. Comparing a large number of cases of probable IPA with control patients with possible or no IPA, we found the performance (i.e., sensitivity and specificity) of the CLIA with BAL fluid samples to be very similar to that of EIA. The quantitative correlation of the CLIA and EIA results was strong as well. However, since different EIA cutoff values are recommended by the manufacturer (GM index of 0.5) and the EORTC/MSGERC definitions (GM index of 1.0), we analyzed three different cutoff values for both tests. Most of the discrepancies between EIA and CLIA results had EIA/CLIA ODI results that were around the cutoff values (Table 4). Previous studies showed good accuracy of the EIA we used on BAL fluid samples for patients with hematological malignancies to discriminate patients with IPA and those without (2, 3). Still, while the specificities of both tests were high across almost all IPA classifications, their sensitivities were moderate and varied from 57% to 76%. This shows, once again, that IPA should not be excluded based on a single mycological test result but a combination of tests (culture, GM assay, and possibly also PCR) is required (18).

One study evaluated the performance of the CLIA previously (13). In that study, the EIA ODI and CLIA ODI values for 78 BAL fluid samples and 249 serum samples were compared, and concordant results were observed in 94% of cases when a CLIA ODI cutoff value of ≥0.200 and an EIA ODI cutoff value of ≥0.5 were used. The authors concluded that there was a strong correlation and high level of consistency between the two assays. As in our observations, some discordant results were observed in that study. Indeed, for 15 patients with probable or proven IPA, the EIA ODI was <0.5 while the CLIA ODI was ≥0.160, while the opposite finding (EIA ODI of ≥0.5 and CLIA ODI of <0.160) was seen for 3 patients, possibly indicating a slightly higher sensitivity of the CLIA. However, detailed information about the patients was not provided, and it is not known whether these discordant samples were BAL fluid or serum samples (13).

In our study, the performances of the CLIA and EIA were very similar when the patients were classified in accordance with the 2020 EORTC/MSGERC criteria. The 2020 EORTC/MSGERC criteria now incorporate Aspergillus PCR as a mycological criterion and have added consolidation as a radiological characteristic, compared with the previously published criteria. However, this analysis is skewed toward the EIA due to incorporation bias because the EIA is part of the EORTC/MSGERC criteria itself. Therefore, we also classified our patients according to the EORTC/MSGERC criteria while excluding the GM EIA result as mycological evidence. This unbiased comparison of the two tests resulted in a CLIA sensitivity (using an ODI cutoff value of 0.200) to detect probable IPA of 63%, while the EIA sensitivity was 57% when the most frequently used BAL fluid sample cutoff value of ≥1.00 was used. For patients with possible IPA (excluding GM as a criterion), 16/73 (22%) BAL fluid samples were positive (ODI value of ≥0.200) with CLIA, while 10/73 (14%) were positive (ODI value of ≥1.0) with EIA, possibly indicating greater sensitivity of the CLIA, as was suggested in the aforementioned study. However, because there is still no optimal test to rule out IPA and there is no test with nearly 100% specificity, the interpretation of test results for patients with possible IPA remains difficult.

The strengths of our study are its multicenter design and the large number of BAL fluid samples from well-characterized patients with probable IPA. Many of the patients (84%) with probable IPA had additional positive mycological test results and remained classified as having probable IPA even when GM was excluded as a mycological criterion. The ability to exclude IPA has increased by using molecular tests in combination with GM assays with BAL fluid samples. Several patients who would have been previously classified as having possible IPA would be classified as having probable IPA with the incorporation of PCR as a mycological criterion.

Our study also has several limitations. First, the gold standard for IPA is histopathological confirmation of tissue invasive growth, and our study population did not include any proven IPA cases. This may, for example, result in overestimation of the sensitivity when true cases may be missed by GM assays or all other mycological tests and thus not classified as proven/probable IPA. Second, the study included only 12 patients who could be classified as having no aspergillosis. The entry criterion was a host factor, according to the 2020 EORTC/MSGERC criteria, and the indication to perform BAL was almost always the presence of unexplained pulmonary infiltrates. In contrast to the 2008 criteria, the 2020 EORTC/MSGERC criteria added patients with a host factor and a lobar or segmental infiltrate to the definition of possible IPA. This results in few patients being classified as having no IPA. Third, a limitation of this study is its retrospective nature. The EIA was carried out prospectively, whereas the CLIA was conducted on samples that had been stored. Despite previous research indicating the stability of GM in frozen samples (19), the study design might have introduced bias due to possible quality loss with freezing/thawing. Additionally, the limited volume of stored samples prevented the retesting of samples with discrepant results from the EIA and CLIA.

Our study indicates that the CLIA can be used with BAL fluid samples to identify IPA in patients with hematological malignancies and in alloSCT recipients. Because the CLIA can be performed easily on individual samples, on-demand testing is possible, while the EIA is commonly conducted two or three times per week with batched samples. The CLIA may prove to be particularly valuable in centers in which a limited number of GM tests are ordered. The performance of the CLIA should be further studied with BAL fluid samples from other patient groups, such as patients with solid organ transplants or patients admitted to the intensive care unit with suspected coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)- or influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Furthermore, because this study evaluated only the performance of CLIA with BAL fluid samples, more studies on the performance of CLIA with serum samples are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all patients who agreed to participate in this study.

This study received no external funding.

J.B.B. received research grants from Gilead Sciences and F2G Ltd. E.d.K. received a research grant from Gilead Sciences. B.R. received a research grant from Gilead Sciences, consulting fees from F2G Ltd., and support for meetings from Pfizer, Gilead Sciences, and F2G Ltd. S.H. received travel support from Gilead Sciences. P.E.V. received grants from Gilead Sciences, MSD, Pfizer, Mundipharma, and F2G and nonfinancial support from OLM and IMMY. B.R. participated in the ExeVir Data and Safety Monitoring Board and received travel support to medical conferences from Gilead Sciences and Pfizer. A.D., A.S., M.R., D.L., K.v.D., A.B., P.-J.H., D.F.P., B.B., F.Z.D., and W.J.G.M. declare no conflict of interests.

Conceptualization: J.B.B., P.E.V., and B.R.; methodology: J.B.B., S.H., P.E.V., and B.R.; formal analysis: J.B.B. and S.H.; investigations: J.B.B., S.H., A.D., A.S., M.R., D.L., K.v.D., A.B., P.-J.H., D.F.P., B.B., F.Z.D., E.d.K., and W.J.G.M.; supervision: P.E.V. and B.R.; writing, original draft: J.B.B. and S.H.; writing, review and editing: all authors.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Jochem B. Buil, Email: jochem.buil@radboudumc.nl.

Kimberly E. Hanson, University of Utah

REFERENCES

- 1.Latge JP, Chamilos G. 2019. Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis in 2019. Clin Microbiol Rev 33:e00140-18. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00140-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Haese J, Theunissen K, Vermeulen E, Schoemans H, De Vlieger G, Lammertijn L, Meersseman P, Meersseman W, Lagrou K, Maertens J. 2012. Detection of GM in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples of patients at risk for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: analytical and clinical validity. J Clin Microbiol 50:1258–1263. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06423-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maertens J, Maertens V, Theunissen K, Meersseman W, Meersseman P, Meers S, Verbeken E, Verhoef G, Van Eldere J, Lagrou K. 2009. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid GM for the diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with hematologic diseases. Clin Infect Dis 49:1688–1693. doi: 10.1086/647935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imbert S, Meyer I, Palous M, Brossas JY, Uzunov M, Touafek F, Gay F, Trosini-Desert V, Fekkar A. 2018. Aspergillus PCR in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for the diagnosis and prognosis of aspergillosis in patients with hematological and non-hematological conditions. Front Microbiol 9:1877. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Eiff M, Roos N, Schulten R, Hesse M, Zuhlsdorf M, van de Loo J. 1995. Pulmonary aspergillosis: early diagnosis improves survival. Respiration 62:341–347. doi: 10.1159/000196477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene RE, Schlamm HT, Oestmann JW, Stark P, Durand C, Lortholary O, Wingard JR, Herbrecht R, Ribaud P, Patterson TF, Troke PF, Denning DW, Bennett JE, de Pauw BE, Rubin RH. 2007. Imaging findings in acute invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: clinical significance of the halo sign. Clin Infect Dis 44:373–379. doi: 10.1086/509917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White PL, Price JS, Posso R, Cutlan-Vaughan M, Vale L, Backx M. 2020. Evaluation of the performance of the IMMY sona Aspergillus GM lateral flow assay when testing serum to aid in diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol 58:e00053-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00053-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenks JD, Miceli MH, Prattes J, Mercier T, Hoenigl M. 2020. The Aspergillus lateral flow assay for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis: an update. Curr Fungal Infect Rep 14:378–383. doi: 10.1007/s12281-020-00409-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenks JD, Mehta SR, Taplitz R, Law N, Reed SL, Hoenigl M. 2019. Bronchoalveolar lavage Aspergillus GM lateral flow assay versus Aspergillus-specific lateral flow device test for diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with hematological malignancies. J Infect 78:249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lass-Florl C, Samardzic E, Knoll M. 2021. Serology anno 2021—fungal infections: from invasive to chronic. Clin Microbiol Infect 27:1230–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egger M, Penziner S, Dichtl K, Gornicec M, Kriegl L, Krause R, Khong E, Mehta S, Vargas M, Gianella S, Porrachia M, Jenks JD, Venkataraman I, Hoenigl M. 2022. Performance of the Euroimmun Aspergillus antigen ELISA for the diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. J Clin Microbiol 60:e00215-22. doi: 10.1128/jcm.00215-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dichtl K, Seybold U, Ormanns S, Horns H, Wagener J. 2019. Evaluation of a novel Aspergillus antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol 57:e00136-19. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00136-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calero AL, Alonso R, Gadea I, Vega MDM, Garcia MM, Munoz P, Machado M, Bouza E, Garcia-Rodriguez J. 2022. Comparison of the performance of two GM detection tests: Platelia Aspergillus Ag and Aspergillus GM Ag Virclia monotest. Microbiol Spectr 10:e02626-21. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02626-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donnelly JP, Chen SC, Kauffman CA, Steinbach WJ, Baddley JW, Verweij PE, Clancy CJ, Wingard JR, Lockhart SR, Groll AH, Sorrell TC, Bassetti M, Akan H, Alexander BD, Andes D, Azoulay E, Bialek R, Bradsher RW, Bretagne S, Calandra T, Caliendo AM, Castagnola E, Cruciani M, Cuenca-Estrella M, Decker CF, Desai SR, Fisher B, Harrison T, Heussel CP, Jensen HE, Kibbler CC, Kontoyiannis DP, Kullberg BJ, Lagrou K, Lamoth F, Lehrnbecher T, Loeffler J, Lortholary O, Maertens J, Marchetti O, Marr KA, Masur H, Meis JF, Morrisey CO, Nucci M, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Pagano L, Patterson TF, Perfect JR, Racil Z, et al. 2020. Revision and update of the consensus definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Clin Infect Dis 71:1367–1376. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chong GM, van der Beek MT, von Dem Borne PA, Boelens J, Steel E, Kampinga GA, Span LF, Lagrou K, Maertens JA, Dingemans GJ, Gaajetaan GR, van Tegelen DW, Cornelissen JJ, Vonk AG, Rijnders BJ. 2016. PCR-based detection of Aspergillus fumigatus Cyp51A mutations on bronchoalveolar lavage: a multicentre validation of the AsperGenius assay in 201 patients with haematological disease suspected for invasive aspergillosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:3528–3535. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White PL, Linton CJ, Perry MD, Johnson EM, Barnes RA. 2006. The evolution and evaluation of a whole blood polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection of invasive aspergillosis in hematology patients in a routine clinical setting. Clin Infect Dis 42:479–486. doi: 10.1086/499949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landis JR, Koch GG. 1977. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33:159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoenigl M, Prattes J, Spiess B, Wagner J, Prueller F, Raggam RB, Posch V, Duettmann W, Hoenigl K, Wölfler A, Koidl C, Buzina W, Reinwald M, Thornton CR, Krause R, Buchheidt D. 2014. Performance of GM, β-d-glucan, Aspergillus lateral-flow device, conventional culture, and PCR tests with bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol 52:2039–2045. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00467-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wheat LJ, Nguyen MH, Alexander BD, Denning D, Caliendo AM, Lyon GM, Baden LR, Marty FM, Clancy C, Kirsch E, Noth P, Witt J, Sugrue M, Wingard JR. 2014. Long-term stability at −20°C of Aspergillus GM in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage specimens. J Clin Microbiol 52:2108–2111. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03500-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material. Download jcm.00044-23-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.3 MB (288.7KB, pdf)