State legislatures are pursuing policies that deny rights and services to transgender youth. In 2021, 8 states have passed anti-transgender laws, while 29 others have attempted similar actions. Some policies, like those that deny transgender youth access to transition-related health services (eg, gender-affirming surgeries and hormone therapy), have explicit health implications. The health consequences of other policies, like those that ban transgender youth from athletics, are less obvious, though perhaps not absent. Drawing from transgender health research, we caution that anti-transgender legislation could exacerbate existing health disparities, facilitate risky health behaviors, and lead to preventable deaths. These potential outcomes warrant treatment as public health concerns.

Transgender People Experience Health Disparities

In 2011, the Institute of Medicine recognized transgender people as a population with unique health disparities.1 Compared to cisgender people, transgender individuals in the US report poorer self-rated health, more chronic illness, and higher rates of disability. A leading explanation for these disparities is that transgender people experience ongoing exposure to prejudice, discrimination, and harassment, which causes chronic stress that wears down the body over time.2 Importantly, transgender health disparities may be influenced by enduring systemic issues, like religious-based persecution, exclusion from institutions, and a lack of protections from discrimination in workplaces, schools, and other public accommodations.

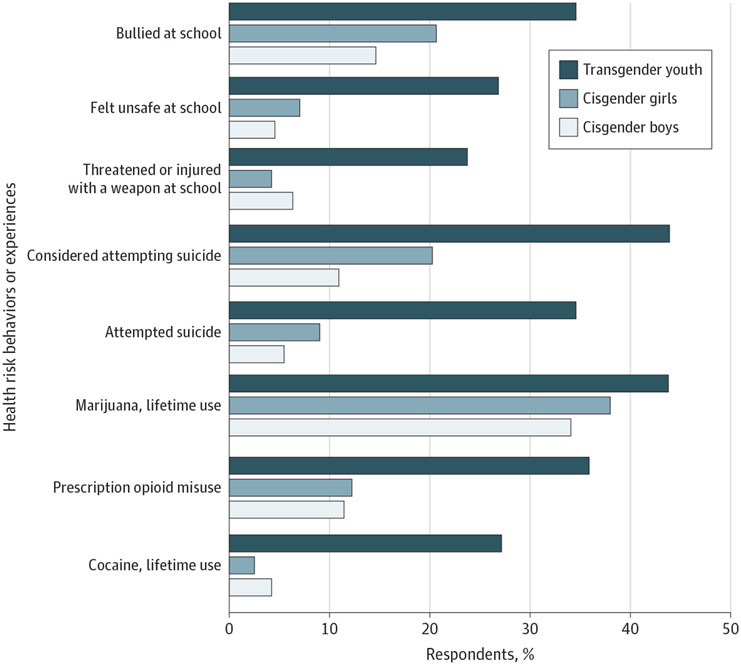

Systemic marginalization may have uniquely harmful effects on transgender youths’ health. The Figure presents analyses by Johns and colleagues,3 who studied health risk behaviors or experiences and health outcomes using the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. The researchers found that, compared to cisgender youth, transgender youth are more likely to feel unsafe at school, experience bullying, and be threatened or injured with a weapon. These forms of health risk behaviors or experiences are associated with poor mental health and harmful coping behaviors.2 For example, transgender youth are more likely than their cisgender peers to use cigarettes, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and prescription opioids (Figure). Even more alarming, nearly 35% to 44% of transgender youth have considered or attempted suicide. Legislation could help to remedy this public health problem, but a growing body of anti-transgender policy might have the opposite effect.

Figure. Health Risk Behaviors or Experiences and Outcomes Among High School Students by Gender ldentity.

Data are from the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey in 10 US states (Colorado, Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Wisconsin) and 9 large urban school districts (Boston, Massachusetts; Broward County, Florida; Cleveland, Ohio; Detroit, Michigan; District of Columbia; Los Angeles, California; New York City, New York; San Diego, California; and San Francisco, California). Adapted from Johns et al.3

New Anti-Transgender Legislation Could Exacerbate Health Disparities

Policies that prohibit physicians from providing transition-related health services to youth may exacerbate the stressors that contribute to transgender health disparities. Arkansas recently passed the so-called Save Adolescents From Experimentation (SAFE) Act— a law that bans physicians from providing puberty blockers, hormone therapy, and gender-affirming care to youth. The law argues that “the risks of gender transition far outweigh any benefit,” but this claim is not supported by studies of transgender youth who receive transition-related services. In fact, research suggests that access to transition-related care is associated with better overall health for transgender youth who desire that care.2 Studies also find that transgender youth who receive transition-related care report less suicidal ideation than transgender youth who want transition care but do not receive it.4 Access to transition-related care is not just a boon to the health of transgender youth, but also a lifesaving resource.

Legislation that prohibits transgender youth from competing in sports consistent with their gender identity could also engender negative health consequences. Overall, sports participation has positive effects on youths’ health, but studies suggest that marginalizing transgender athletes could reduce those health rewards.5 As an illustration, transgender people who experience harassment in athletic environments, like gyms and locker rooms, are exposed to stress that appears to limit or erase the health benefits that they would otherwise enjoy from sports participation.5 Policies that ban transgender youth from athletics—or force them to play on teams that do not align with their gender identity—stigmatize transgender athletes, legitimize marginalization that already exists in athletic spaces, and add health-harming discrimination to transgender people’s lives. Rather than weaponizing athletics against transgender people, policy makers should ensure that sports participation is a mechanism that improves health.

In 2021, state legislatures have manufactured a wave of anti-transgender policies that allow religious-based discrimination against transgender people, prevent transgender people from obtaining gender-affirming identity documents, and require businesses to notify patrons if they allow transgender people to use bathrooms aligned with their gender identity. Such laws send messages to transgender people that they are not welcomed in places where people live, work, learn, and play.6 These policies may be devastating to the health of transgender people, but also to entire communities that lose human resources because of a less healthy population.2,6,7

Policy Makers and Clinicians Can Solve This Public Health Crisis

Policy makers could build a healthier population by prioritizing legislation that reduces discrimination against transgender people. For example, if policy makers are concerned about the health of youth who receive transition care, they could invest in research and medical training on gender minority groups and their health needs, which could improve treatments and better prepare health care professionals to support transgender patients. Further, instead of banning transgender athletes from sports, policy makers should encourage innovative categories for competition that organize people based on strength and skill, rather than anatomy. Federal policies that provide nondiscrimination protections, like the Equality Act, could also produce gains in the health of transgender youth. In the meantime, we urge policy makers to oppose policy initiatives that marginalize transgender youth.

Clinicians can also offset the potentially harmful effects of anti-transgender legislation. First, clinicians could ensure that their facilities and online spaces are welcoming and accessible for transgender youth by offering transgender-specific health information and consulting with transgender health advocacy groups. Clinicians could also seek continuing education that would improve their ability to treat transgender patients and refer them to appropriate physicians and services.

In sum, the transgender population endures unique health challenges that may be compounded by anti-transgender policies. Legislation that denies transgender youth access to gender-affirming care or prohibits their participation in sports prevents an already vulnerable population from enjoying services and activities with known health benefits and exposes transgender youth to more health-threatening marginalization.2 Although large, these problems are surmountable. If guided by research, compassionate health care policy and practice can solve this public health concern.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

Dr Barbee was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award R01AG063771 during the writing of this manuscript. Dr Gonzales was supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. No other disclosures were reported.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Contributor Information

Harry Barbee, Department of Medicine, Health & Society, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee..

Cameron Deal, Program for Public Policy Studies, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee..

Gilbert Gonzales, Department of Medicine, Health & Society, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee; Program for Public Policy Studies, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee; Department of Health Policy, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee..

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People. National Academy of Sciences; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delozier AM, Kamody RC, Rodgers S, Chen D. Health disparities in transgender and gender expansive adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2020;45(8):842–847. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johns MM, Lowry R, Andrzejewski J, et al. Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students—19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(3):67–71. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turban JL, King D, Carswell JM, Keuroghlian AS. Pubertal suppression for transgender youth and risk of suicidal ideation. Pediatrics. 2020;145(2):E20191725. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones BA, Arcelus J, Bouman WP, Haycraft E. Sport and transgender people. Sports Med. 2017;47(4):701–716. doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0621-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughto JMW, Meyers DJ, Miniaga MJ, Reisner SL, Cahill S. Uncertainty and confusion regarding transgender non-discrimination policies. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. Published online June 11, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s13178-021-00602-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conron KJ, O’Neill K, Vasquez LA. Prohibiting Gender-Affirming Medical Care for Youth. Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law; 2021. [Google Scholar]