Abstract

Scope:

Genistein increases whole body energy expenditure by stimulating white adipose tissue (WAT) browning and thermogenesis. G-Coupled receptor GPR30 can mediate some actions of genistein, however, it is not known whether it is involved in the activation of WAT-thermogenesis. Thus, the aim of the study is to determine whether genistein activates thermogenesis coupled to an increase in WAT browning and mitochondrial activity, in GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice.

Methods and Results:

GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice are fed control or high fat sucrose diets containing or not genistein for 8 weeks. Body weight and composition, energy expenditure, glucose tolerance, and browning markers in WAT, and oxygen consumption rate, 3’, 5’-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) concentration and browning markers in adipocytes are evaluated. Genistein consumption reduces body weight and fat mass gain in a different extent in both genotypes, however, energy expenditure is lower in GPR30−/− compared to GPR30+/+ mice, accompanied by a reduction in browning markers, maximal mitochondrial respiration, cAMP concentration, and browning markers in cultured adipocytes from GPR30−/− mice. Genistein improves glucose tolerance in GPR30+/+, but this is partially observed in GPR30−/− mice.

Conclusion:

The results show that GPR30 partially mediates genistein stimulation of WAT thermogenesis and the improvement of glucose tolerance.

Keywords: energy expenditure, genistein, glucose tolerance, GPR30, thermogenesis

1. Introduction

The incidence of obesity has strikingly increase in the last decade and is now considered a pandemic worldwide.[1,2] Obesity is defined as an increase in adipose tissue in the body leading to the development of several metabolic diseases including type-2 diabetes (T2D) and cardiovascular diseases.[1,3] Accumulation of fat in adipose tissue occurs as a result of the imbalance between energy intake depending on the amount and type of carbohydrates, fat, and protein consumed in the diet, and energy expenditure, mainly associated to basal metabolism, diet-induced thermogenesis, and physical activity, but also including shivering and non-shivering thermogenesis that may play a significant role in energy utilization.[3,4] Several mechanisms are involved in the imbalance of energy homeostasis, including alterations both in mechanisms controlling energy intake, and also in those involved in the utilization of macronutrients as energy substrates.[5,6] The adipose tissues play a key role in macronutrients utilization, since white adipose tissue (WAT) stores the excess of energy in triglyceride form, whereas brown adipose tissue (BAT) utilizes macronutrients, particularly glucose and fatty acids in order to increase thermogenesis.[7–9] In addition, under certain conditions, cells of the vascular stromal fraction of white adipose tissue can be converted into beige adipocytes by a process known as WAT browning also increasing thermogenesis.[10–13]

In recent years, there has been an extensive search for inducers of WAT browning.[13–16] Among them, we and others have found that the isoflavone genistein stimulates this process.[17,18] Studies in mice or with cultured adipocytes have shown that genistein is able to increase the expression of genes involved in thermogenesis in adipose tissue including the uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) and others beige markers, such as T-box transcription factor 1 (TBX1).[17,18] In addition, consumption of genistein can increase energy expenditure preventing an excessive body weight gain even after the consumption of a high fat diet.[18,19] Studies show that genistein, in addition to stimulate thermogenesis, also improves insulin sensitivity,[18,20–22] and this is associated with increased phosphorylation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) at threonine 172, which in turn phosphorylates acetyl-CoA carboxylase decreasing the malonyl-CoA pool and thus increasing ß-fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle.[19] However, there is scarce evidence of how genistein has the ability to initiate the activation of the thermogenic program.

Studies with the breast cancer cell line SKBR3 have shown that genistein can induce gene expression of several cell proliferation-associated proteins through the G-coupled receptor GPR30.[23] GPR30 is a G protein-coupled seven-transmembrane receptor, and the human GPR30 comprises 375 amino acids with a theoretical molecular mass of approximately 41 kDa. The N-terminus region of this receptor is located outside the cell, and several aspartic acid residues are modified by glycosylation.[24] GPR30 is a receptor that mediates non-genomic responses of estrogens including the generation of second messengers such as 3’,5’-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), Ca2+, nitric oxide (NO) as well as the activation of tyrosine kinases receptors.[25] Physiologically, GPR30 participates in the regulation of cell growth.[26] Although some evidence shows that the effects of genistein may involve GPR30, it is not known whether this receptor may be associated with the activation of WAT thermogenesis by genistein. GPR30 knockout mice (GPR30−/−) were initially designed to determine the role of GPR30 in thyme atrophy induced by estrogens.[27] Later studies demonstrated that estrogens induce insulin secretion in the pancreas through GPR30 activation,[28] and GPR30−/− mice develop insulin resistance and abnormal lipid metabolism.[29] In addition, GPR30 loss-of-function induces dyslipidemia in aged male mice,[29] and decreases energy expenditure in 6 months age mice,[30] meaning that GPR30 could be involved in the maintenance of a normal metabolic state. In addition, it is not known whether changes in energy expenditure are associated with changes in the capacity of the adipose tissue to modulate thermogenesis via GPR30. Thus, the aim of the present work was to evaluate whether the stimulation of WAT thermogenesis and the modulation of energy expenditure induced by genistein are mediated by GPR30.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

Genistein was purchased from LC Laboratories, (Woburn, MA, USA). Genistein HPLC grade for cell culture stimuli was obtained from Sigma Aldrich-Merck, (Darmstad, Germany). Serum triglycerides and glucose were measured using a COBAS c111 analyzer (Roche, Switzerland). The ELISA kit for insulin was purchased from Merck Millipore (Darmstadt, Germany). Anti-AMPK, anti-phospho AMPK (pAMPK), and Anti-Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1α) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA), whereas anti-UCP1, anti-T-Box Transcription Factor 1 (TBX-1), anti-PR domain containing 16 (PRDM16) and anti-Cell Death Inducing DFFA Like Effector A (CIDEA), and anti-GAPDH were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail tablets were purchased from Roche, (Mannheim, Germany). The Immobilon Western chemiluminescent HRP substrate detection system was obtained from Millipore (Temecula, CA, USA). Other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich-Merck, (Darmstad, Germany).

2.2. Animal Care and Maintenance

All the protocols and procedures described in this section had been approved by the animal care committee of the National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition, CICUAL-1900 Mexico City. Homozygous GPR30−/− breeding mice from the genetic background derived from C56BL/6 mice were donated by Halina Offner/ DeLynn Rohrbacher, US Veterans Hospital Road, Portland Oregon. The GPR30+/+ mice used in the study were obtained from the same genetic background. Mice were breaded according to the protocols of the animal facility.

For the study, male GPR30+/+ and homozygous GPR30−/− mice of 8 weeks old with a weight of 22–25 g were maintained in cages (n = 8–9) with a 12-h light-dark cycle, at 22 °C for 60 days. Mice were randomly assigned to four different groups of diets, AIN-93 diet (control diet), high fat sucrose diet (HFSD), AIN-93 diet with 0.2% of genistein, and HFSD with 0.2% of genistein. The energy provided by the AIN-93 diet and the HFSD was 3.9 and 4.8 kcal g−1, the composition between diets was adjusted and only the fat percentage distribution and the source of lipids and carbohydrates was modified. The HFSD compared to the AIN-93 diet contained lard and twice as much sucrose. Diets were administered in dry form and the composition of each was described in Table 1. Food consumption and the body weight of the mice was measured twice a week. At the end of the study, animals were euthanized after 8 h fasted period. Whole blood was collected in a centrifuge tube with heparin and serum was obtained and frozen at −80 °C after centrifugation at 1000 × g for 10 min. Gastrocnemius skeletal muscle was also obtained, as well as inguinal subcutaneous WAT and BAT samples, which were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Table 1.

Composition of the different diets, the control AIN-93-diet and the high fat-sucrose diet (HFSD) with or without genistein.

| Ingredients | Control [%] | Control genistein [%] | HFSD [%] | HFSD Genistein [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-Cystine | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Choline bitartrate | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Vitamin mix | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Fiber | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Mineral mix | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Soybean oil | 7 | 7 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| Cornstarch | 39.74 | 39.54 | 9 | 8.8 |

| Dextrinized cornstarch | 13.2 | 13.2 | 11.4 | 11.4 |

| Sucrose | 10 | 10 | 21.3 | 21.3 |

| Casein | 20 | 20 | 24 | 24 |

| Lard | 0 | 0 | 21.88 | 21.88 |

| TBHQ | 0.0014 | 0.0014 | 0.0013 | 0.0013 |

| Genistein | – | 0.2 | – | 0.2 |

| TOTAL | 99.99 | 99.99 | 100.73 | 100.73 |

TBHQ indicates tert-butylhydroquinone.

2.3. Determination of Body Composition

Mice were individually placed into a thin-walled plastic cylinder, with a cylindrical plastic insert added to limit movement in a quantitative magnetic resonance imaging system (Echo MRI, Houston, TX, USA). While in the tube, the animals were briefly subjected to a low intensity (0.05 Tesla) electromagnetic field to measure fat and lean mass. Measurements were performed twice, at baseline and after 58 days of the study.

2.4. Intraperitoneal Glucose Tolerance Test

On day 48, an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test was performed. Before conducting this test, the mice were fasted for a short period of time (7 h). Prior to glucose injection, mice were tail pinched, and a tail blood sample was obtained to measure serum glucose in the basal phase, after which intraperitoneal injection of 2 g kg−1 body weight of glucose was performed. Tail blood samples were obtained at 15, 30, 45, 60, and 120 min after injection. Glucose concentration was measured with the OneTouch Ultra glucometer (Accu-Check Sensor, Roche Diagnostics).

2.5. Indirect Calorimetry

On day 58, an indirect calorimetry test was carried out using a Comprehensive Lab Animal Monitoring System (Columbus Instruments, OH, USA). All mice were individually housed and acclimatized in the measurement cages 24 h before the beginning of the study. Measurements were conducted during 48 h after the acclimatization period. The test was carried out at 22 °C under a 12h/12h light-dark cycle. During the test, water was always available, and food was only available from 19:00 to 7:00 h. The mice were weighted before the test was performed. Energy expenditure (EE) was calculated with the following equation: EE = (3.815 + 1.232*RER) * VO2.[31] Multiple linear regression was performed to evaluate the slopes of change in VO2 (mL h−1) and EE (kcal h−1) per unit change of body weight (g) and fat mass (g).

2.6. Serum Measurements

Serum glucose, cholesterol, and triglycerides concentration were measured by a COBAS c1 11 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Serum insulin levels were measured using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany).

2.7. Western Blot Analysis

Skeletal muscle, subcutaneous WAT, and BAT extracts were prepared by homogenizing the tissue in RIPA buffer containing PBS buffer, SDS, sodium deoxycholate, sodium azide, NP-40, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors. SVF cell extracts were obtained by washing cells with PBS buffer and prepared with RIPA buffer containing PBS buffer, SDS, sodium deoxycholate, sodium azide, NP-40, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Total protein was obtained by centrifugation for 20 min. The proteins were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The membranes were incubated with specific antibodies against pAMPK, AMPK, UCP1, PGC1α, TBX-1, PDRM16, or CIDEA, revealed using an anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies from abcam (Cambridge, UK). GAPDH antibody was used as control. Bands were detected using Immobilon Western chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA). The chemiluminescence was digitized using the ChemiDoc MP imaging system (Bio Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and analyzed using ImageJ 1.51 (100) 2015 digital imaging processing software.

2.8. Cell Culture

Pre-adipocytes were obtained from the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of inguinal adipose tissue from male GPR30+/+ or GPR30−/− mice. Inguinal tissues were dissected and digested with 0.025% type IV collagenase (Gibco Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) for 60 min at 37 °C. The digested cells were centrifuged at 1500 × g for 15 min, and the pellet was washed twice with DMEM F12 (Gibco Life Technologies). The cells were then seeded in a flask with DMEM F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco Life Technologies) and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic mixture (Caisson, Labs Smithfield, UT, USA) and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Pre-adipocytes were plated in 6-well plates (Corning Inc, Somerville, MA, USA) upon reaching 75% confluence, the medium was changed, and 2 days later (day 1), the cells were exposed to induction medium containing complete medium with 1 μM dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich Merk, Darmstadt, Germany), 1 μM insulin (Sigma-Aldrich Merk, Darmstadt, Germany), 0.5 mM isobutylmethyl-xanthine (Sigma-Aldrich Merk, Darmstadt, Germany), and 20 μM genistein (Sigma Aldrich-Merck, Darmstad, Germany) or vehicle (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich Merk, Darmstadt, Germany) for 96 h. On day 4 of differentiation, cells were plated in XFe96 microplates (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara CA, USA) (15 000 cells per well) and maintained in maturation medium (DMEM F12+1 μM insulin) with 20 μM genistein (Enzo Life Sciencies, Farmingdale, NY, USA) or vehicle (DMSO) for an additional 6 days. The medium was changed every 48 h until day 6.

To measure intracellular AMPc concentrations, pre-adipocytes were plated in 12-wells plates (Corning Inc, Somerville MA, USA) (500 000 cells per well); upon reaching 75% confluence, the medium was changed, and 2 days later (day 1), the cells were exposed to the induction medium described above with 20 μM genistein (Sigma Aldrich-Merck, Darmstad, Germany) or vehicle (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich Merk, Darmstadt, Germany) for 96 h. On day 4 of differentiation, induction medium was change and replaced with maturation medium (DMEM F12+1 μM insulin) with 20 μM genistein (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) or vehicle (DMSO) for 6 additional days. The medium was changed every 48 h until day 6. Protein abundance was measured in SVF cells differentiated into adipocytes and plated in 6-well plates. The differentiation protocol was the same as described earlier in this section.

2.9. Mitochondrial Energy Status Measurement

Mitochondrial respiration of SVF adipocytes were determined by the mitochondrial stress assay kit, in XFe96 microplates, using the XFe96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara CA, USA). Prior to measurement, cells were washed with XF basal medium (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara CA, USA) supplemented with 11 mM glucose, 1 mM pyruvate, and 2 mM glutamine. Cells were incubated for 1 h in a CO2-free incubator with the same medium. To determine mitochondrial respiration during the protocol, three different compounds were sequentially injected, 2 μM oligomycin, 1 μM carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxy phenylhydrazone (FCCP) and 1 μM rotenone/antimycin A (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara CA, USA). OCR measurements were obtained and analyzed following the manufacturer’s recommendations (Seahorse Bioscience, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara CA, USA). Results were normalized by cell number quantification using Hoechst nuclei dye, and fluorescence was measured using the Cytation-1-cell-imaging-multi-mode-reader (BioTek, Winooski, Vermont USA). Experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.10. BodiPy Staining and Adipocytes Calculation

Adipocyte differentiation and the total amount of cells were determined by staining with BodiPy (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and Hoechst (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). SVF adipocytes were incubated with 250 nM of Bodipy and 2 μM Hoechst for 20 min,fluorescence was quantified using the Cytation-1-cell-imaging-multi-mode-reader (BioTek, Winooski, Vermont USA). The number of adipocytes was determined by establishing a ratio between the number of differentiated adipocytes with respect to the total number of precursor cells for each condition.

2.11. cAMP Measurement in Adipocytes

To measure intracellular cAMP in SVF-derived adipocytes from GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice, the cAMP complete ELISA kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) was used. To perform the assay, maturation medium was replaced with fasting medium (DMEM F12+ AA) for 4 h. After fasting time, the cells were incubated and stimulated with DMEM F12 with 20 μM genistein (Sigma Aldrich-Merck, Darmstad, Germany) or vehicle (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich Merk, Darmstadt, Germany) for 15 min. After the incubation time, the cells were washed with PBS buffer and lysed with 0.1 M HCL. The lysates were collected and incubated at 4 °C for 10 min. Samples were centrifugated at 1000 ×g and the supernatant was separated from the cellular debris. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (cAMP complete ELISA kit, Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) and was carried out in the acetylated format.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

The results were presented as the means ± SEMs. Analysis of more than two groups was performed by two-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s protected least-square difference test. The differences were considered significant at p < 0.05 (GraphPad Prism San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Genistein Consumption Decreased Body Weight of GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− Mice

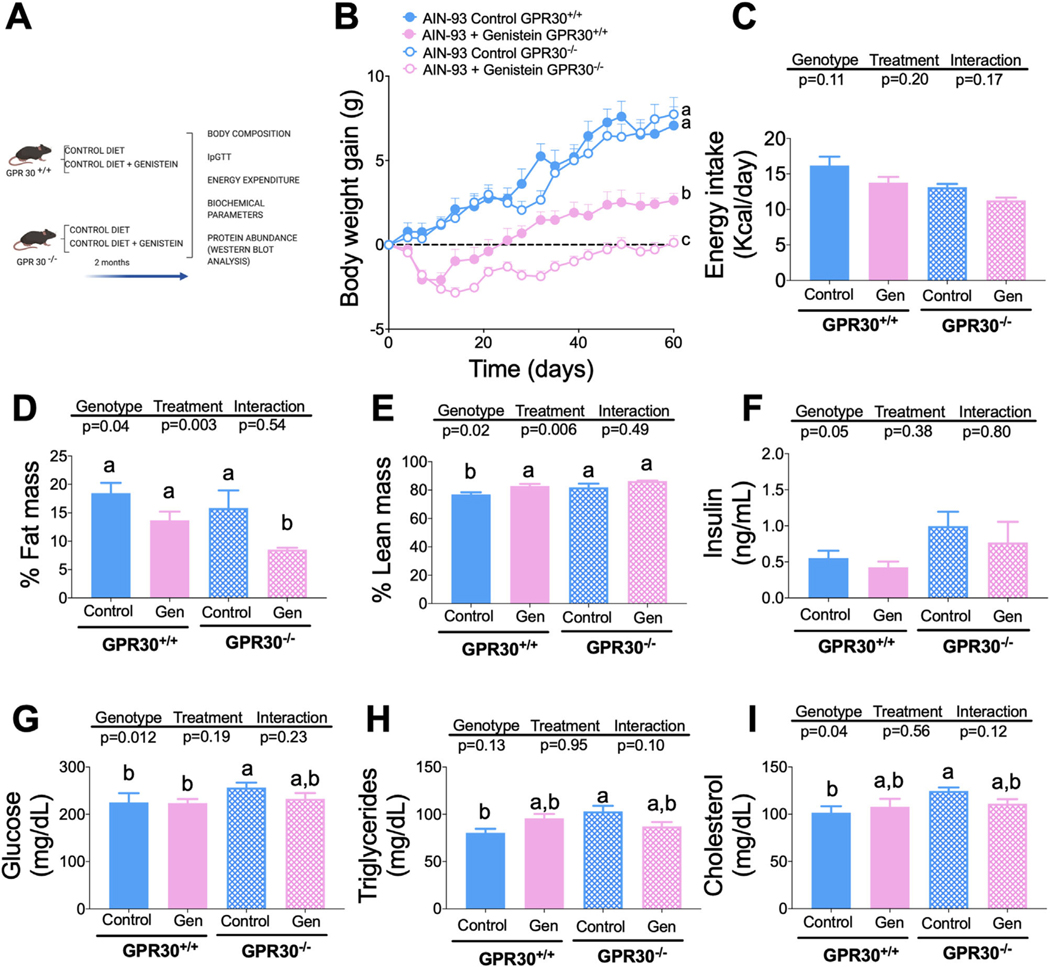

To determine whether genistein could modify body weight and body composition as well as some serum biochemical markers through GPR30, we fed GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice with a control diet with or without genistein for 2 months (Figure 1A). Interestingly, it was observed that mice fed genistein, regardless of the genotype (Figure S1A, Supporting Information), gained significantly less body weight than those fed the control diet. When net weight gain was determined, it was shown that, at the end of the study, GPR30+/+ mice fed genistein gained 59% less body weight than the GPR30+/+ group without genistein, whereas GPR30−/− mice fed genistein showed 98.4% lower body weight gain compared with the GPR30−/− group fed control diet (Figure 1B). The differences in body weight gain in mice fed diets with or without genistein were not due to changes in energy intake, as it was observed that there were no significant differences in either the average energy intake during the study or in the consumption between the groups throughout the study (Figure 1C, Supplement 2A, Supporting Information), suggesting that genistein might exert its effect on body weight through an increase in energy expenditure, possibly by modulating the thermogenic capacity, as observed previously. Consequently, the body composition of GPR30+/+ mice fed a genistein-supplemented diet showed 4.8% less fat mass compared to those fed a control diet without genistein (p = 0.07) (Figure 1D). In addition, genistein consumption increased lean mass by approximately 6% with respect to those fed control diet without genistein (p = 0.03) (Figure 1E). GPR30−/− mice fed genistein significantly reduced the percent of body fat mass by 7.3% compared to those fed control diet (p = 0.008) (Figure 1D). Whereas in these mice, genistein increased lean mass by 4.4%, compared to those consuming the control diet (p = 0.06). Interestingly, consumption of a control diet in GPR30+/+ or GPR30−/− mice produced very modest changes in the fasting biochemical parameters, including serum insulin and glucose, as well as serum lipids such as triglycerides and cholesterol (Figures 1F–I). Furthermore, supplementation of control diet with genistein did not modify these serum biochemical parameters in GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice despite the differences in body weight gain.

Figure 1.

Effects of genistein on body weight, food intake, percentage of fat mass, percentage of lean mass, serum insulin, glucose, triglyceride, and cholesterol concentration in GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice fed AIN-93 diet. A) Experimental design, B) body weight gain during the study, and C) mean food intake during the study period, D) percentage of fat mass, and E) lean mass at the end of the study. F) Insulin was measured by and EKISA Kit, G) Glucose, H) Triglycerides, and I) cholesterol were measured at the end of the study with the COBAS c111 Analyzer. Results are shown as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 7/8 by group). A two-way ANOVA was performed, letters indicate significant differences between groups (a>b>c>d).

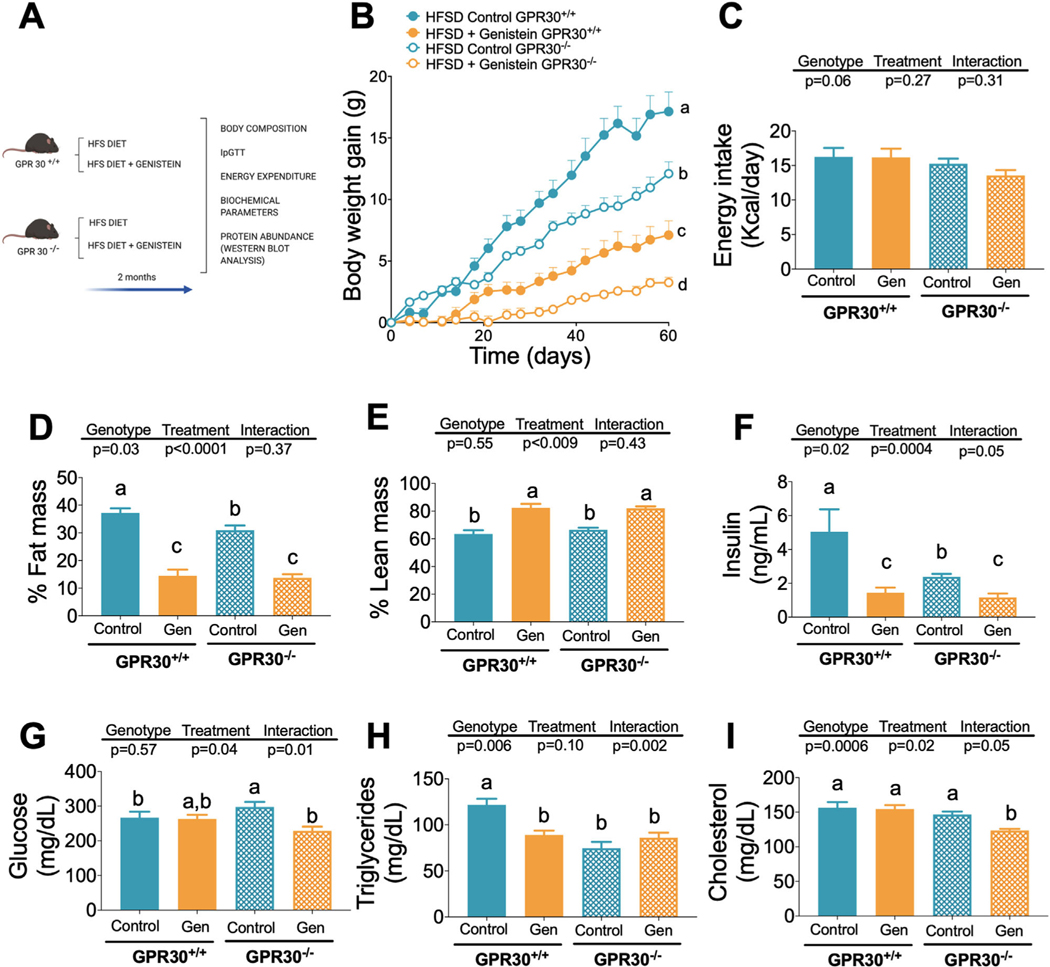

3.2. Genistein Metabolic Effects Were Magnified in Mice Fed a High Fat Sucrose Diet

Since we observed modest effects of genistein on body composition and serum biochemical variables in mice fed a control diet, we studied whether this bioactive compound could modify body weight, body composition, and serum biochemical variables after the consumption of a high fat sucrose diet for 2 months (Figure 2A) through GPR30. As expected, consumption of a HFSD significantly increased body weight in GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice, however the increase was genotype dependent (Figure S1B, Supporting Information). At the end of the study, GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice fed the HFSD diet gained 17.2 and 12.1 g of body weight, respectively. The addition of genistein to HFSD reduced net body weight gain by 58% and 73% in the GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− groups fed genistein, respectively, compared to those fed HFSD without genistein (Figure 2B). Furthermore, the difference in weight gain was not due to differences in energy intake, as all groups showed similar energy intake (Figure 2C, Suplementary 2B, Supporting Information). As a consequence, genistein consumption significantly decreased the percent of body fat mass in GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice, but also increased the percent of body lean mass in both groups (Figures 2D,E). In addition, genistein decreased serum insulin in GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− by 71% and 51%, respectively (Figure 2F). Interestingly, only GPR30−/− mice supplemented with genistein significantly reduced serum blood glucose (Figure 2G). Furthermore, genistein significantly reduced serum triglycerides only in the GPR30+/+ group (Figure 2H) and cholesterol in GPR30−/− mice (Figure 2I). To determine differences in weight gain and fat mass among groups we studied the energy expenditure.

Figure 2.

Effects of genistein on body weight, food intake, percentage of fat mass, percentage of lean mass, serum insulin, glucose, triglyceride and cholesterol concentration in GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice fed HFSD diet. A) Experimental design, B) body weight gain during the study, and C) mean food intake during the study period, D) percentage of fat mass, and E) lean mass at the end of the study. F) Insulin was measured by and EKISA Kit, and G) Glucose, H) Triglycerides, and I) cholesterol were measured at the end of the study with the COBAS c111 Analyzer. Results are shown as the means ± S.E.M. (n = 7/8 by group). A two-way ANOVA was performed, letters indicate significant differences between groups, (a>b>c>d).

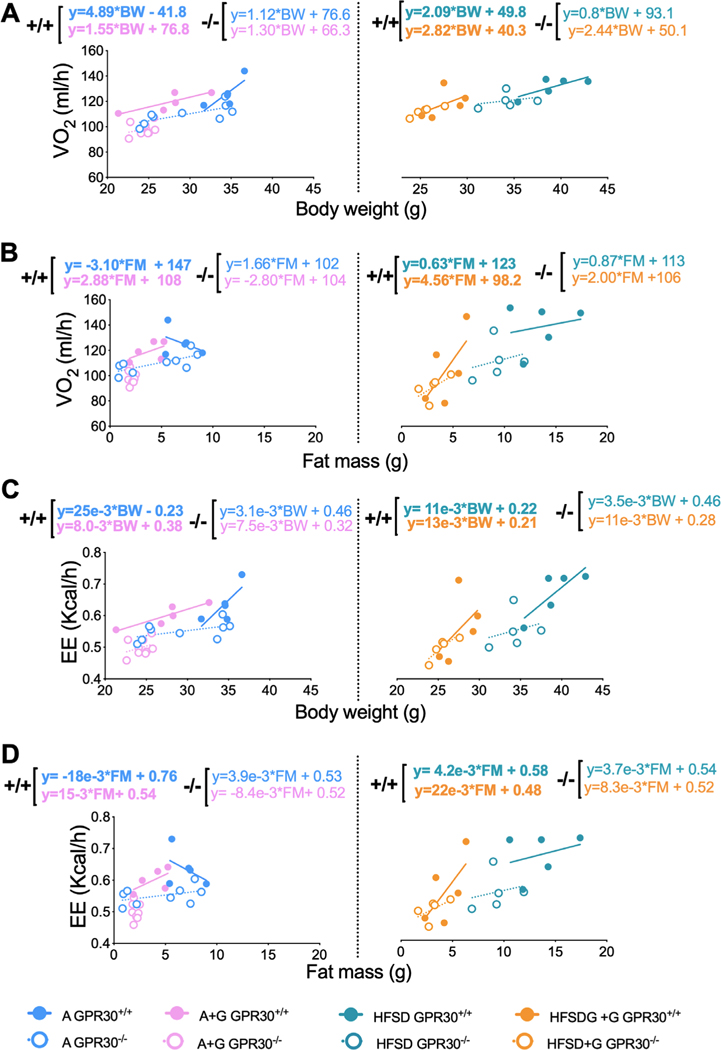

3.3. Stimulation of Energy Expenditure by Genistein in Fat Mass is GPR30-Dependent

To determine whether genistein modified oxygen consumption or energy expenditure in a GPR30-dependent manner, we performed an indirect calorimetry assay. We observed no significant differences in oxygen consumption between GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice fed a control diet during fasting and feeding conditions (Figure S3A, Supporting Information). However, GPR30−/− mice treated with genistein had lower oxygen consumption during the feeding period than GPR30+/+ mice (Figure S3B, Supporting Information), suggesting that the effect of genistein on oxygen consumption could partially be mediated by GPR30. On the other hand, we observed no significant differences in oxygen consumption between GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice fed a HFSD diet under fasting or feeding conditions or treated with genistein (Figure S3C,D, Supporting Information). To rule out that the observed changes in oxygen consumption were attributable to changes in body weight, we assessed how oxygen consumption and energy expenditure fluctuated with respect to body weight and body composition by performing a linear regression analysis as has been previously recommended.[32–34] We calculate the slopes of change of VO2 (mL h−1) or EE (kcal h−1) per unit change of body weight (g) or fat mass (g) under fed conditions in wild-type and GPR30−/− mice treated with and without genistein. Notably, oxygen consumption was on average 5 mL h−1 per g of body weight (BW) in GPR30+/+ mice fed the control diet and 2 mL h−1 per g of BW in mice fed a HFSD, and only 1 mL /h−1 per g of BW on average in GRP30−/− mice fed either the control or the HFS diet (Figure 3A). Interestingly, GPR30−/− mice treated with genistein had similar oxygen (Figure 3A). Conversely, the slope of change of oxygen consumption per g of fat mass was negative in the control group, indicating that oxygen consumption decreased as the fat mass increased. Mice treated with genistein maintained a positive slope only in GPR30+/+, indicating that genistein increased adipose tissue oxygen consumption in a GPR30-dependent manner, since GRP30−/− mice treated with genistein had also a negative slope (Figure 3B). In mice fed a HFSD, oxygen consumption was almost the same (around 2 mL h−1 per g of BW) in GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice (Figure 3A) regardless of genistein treatment. Interestingly, HFSD mice treated with genistein increased oxygen consumption from 0.6 to 4.6 mL h−1 per g of fat mass in GPR30+/+ mice and from 0.9 to only 2 mL h−1 in GRP30−/− mice (Figure 3B), these results suggest that genistein increases oxygen consumption by adipose tissue partially in a GPR30-dependent manner. On the other hand, the slope of change of EE per unit of BW and per unit of fat mass had the same pattern to that of oxygen consumption (Figures 3C,D), indicating that the substrate being oxidized was similar in all treatments. Altogether, these results indicate that genistein increased energy expenditure mainly in fat mass in a GPR30-dependent manner. This is in agreement with a previous result where we have observed that genistein increases the thermogenic program of adipose tissue with a concomitant increase in energy expenditure.[17] However, we can now suggest that this effect is partly dependent on GPR30.

Figure 3.

Effects of genistein on oxygen consumption (VO2) and energy expenditure (EE) measured by body weight (BW) and per gram of fat mass (FM) during feeding period. Indirect calorimetry was performed on GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice fed with AIN-93 and HFSD diet. Regression plots comparing A) oxygen consumption (VO2 mL h−1) per body weight gram and B) oxygen consumption (VO2 mL h−1) per gram of fat mass. C) Energy expenditure (EE, kcal h−1) per body weight gram and D) energy expenditure (EE, kcal h−1) per fat mass gram. The slope and intercept in mL h−1 or kcal h−1 are indicated for each condition, (n = 5–8 by group). AIN93 = blue circles, AIN93 + genistein = pink circles, HFSD = green circles, HFSD+ genistein = orange circles, GPR30+/+= solid circles and lines, GPR30−/− = empty circles and dotted lines.

3.4. Stimulation of Mitochondrial Respiration by Genistein in White Adipocytes Is Partially GPR30-Dependent

Based on the data obtained in the calorimetry assessment, in order to understand whether genistein was able to stimulate energy expenditure through GPR30-mediated activation of WAT mitochondrial respiration, we first analyzed the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in differentiated adipocytes from the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of the inguinal WAT of GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice. To corroborate adipocyte differentiation from the vascular fraction of the inguinal WAT of both genotypes, bodipy dye and Hoechst dye were used to determine the number of differentiated adipocytes and the total number of cells in each condition. The results showed that cells of both genotypes differentiated into adipocytes (Figure S4A, Supporting Information). The number of adipocytes obtained from SVF cells of GPR30−/− mice incubated without treatment was significantly lower compared with those obtained from GPR30+/+ mice (Figure 4A). Interestingly, genistein treatment was observed to decrease differentiation into adipocytes compared with untreated cells, and this effect was amplified when SVF cells from GPR30+/+ mice were used (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Effects of genistein on mitochondrial respiration of SVF-derived adipocytes from GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice. A) Number of adipocytes from differentiated SVF cells, in each condition, from both GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/−iWAT. B) Genistein-Control adipocyte ratio for both GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− iWAT’s SVF cells. C) OCR of GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− iWAT adipocytes treated with 20 μM genistein during differentiation. This assay was performed with XF Mito Stress Kit: oligomycin (2 μM), FCCP (1 μM), and rotenone/antimycin A (1 μM). D) Non-mitochondrial respiration, E) basal respiration, F) maximal respiration, G) spare capacity, H) ATP Linked respiration, I) proton leak respiration. For analysis of differences between genistein treatment and control adipocytes, an unpaired Student’s t-test was performed, * p = 0.05, ** p = 0.002, *** p = 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001. For the number of adipocytes and respirometry analysis a two-way ANOVA was performed, letters indicate significant differences between groups, (a>b>c).

The respirometry results showed that the incubation of adipocytes with genistein increased the maximal OCR in comparison with those incubated with vehicle and this effect was only observed in adipocytes obtained from GPR30+/+ mice (Figure 4C). Genistein was able to decrease the non-mitochondrial respiration by 14.8% only in the GPR30+/+ cells compared to the vehicle, and this parameter is associated with non-mitochondrial-dependent respiration such as glycolysis (Figure 4D). In GPR30+/+ adipocytes, genistein increased maximal mitochondrial respiration by 85%, but also increased the spare respiratory capacity of the cells by 150%. Interestingly, genistein was unable to increase these parameters in GPR30−/− adipocytes (Figures 4E,F) indicating that this effect is GPR30-dependent. It is noteworthy that in GPR30−/− adipocytes, maximal respiration and spare capacity were higher in cells not stimulated with genistein compared to adipocytes from GPR30+/+ cells. Basal respiration and respiration associated with ATP production was increased by genistein in GPR30−/− cells, whereas in GPR30+/+ cells basal respiration tended to increase with the genistein stimuli but did not reach statistical significance (Figure 4G,H). OCR linked to ATP production was significantly increased in both genotypes, 28.4% in GPR30+/+ and 28.8 % in GPR30−/− cells (Figure 4H), respectively. No changes were observed in the OCR related to proton leak parameter (Figure 4I). These results indicate that the effects genistein on maximal respiration and spare respiratory capacity are partially GPR30-dependent, whereas the effects of genistein on respiration associated with ATP production are GPR30-independent.

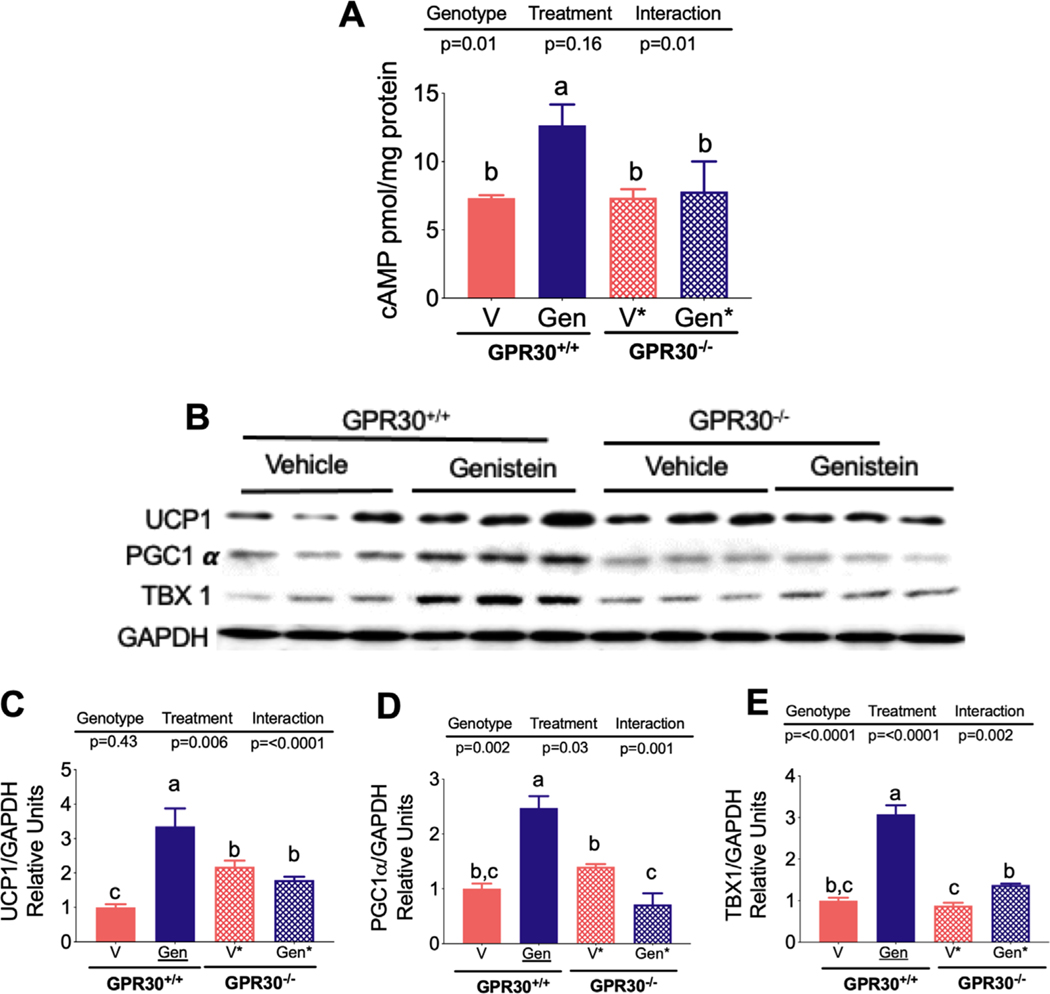

3.5. Genistein Increases cAMP in GPR30+/+ White Adipocytes Stimulating the Expression of Thermogenic Markers

There is evidence that genistein increases cAMP production in skeletal muscle, leading. to several metabolic effects, particularly an increase in fatty acid oxidation.[19] This motivated the exploration of whether genistein was able to mediate an increase in cAMP in white adipocytes via GPR30. Our results clearly show that genistein significantly increased cAMP in adipocytes derived from SVF of GPR30+/+ mice (Figure 5A). This effect was not observed in white adipocytes derived from SVF of GPR30−/− mice, indicating that GPR30 plays an important role in genistein-mediated cAMP production. Interestingly, we observed that the genistein-mediated cAMP increase in GPR30+/+ white adipocytes was accompanied by a significant increase in UCP1, PGC1α, and TBX1 abundance, suggesting that this isoflavone was able to activate the browning program in these cells (Figure 5B–E). However, in the absence of GPR30, genistein was unable to increase cAMP and this resulted in a significantly reduced expression of the aforementioned thermogenic genes, indicating that white adipocytes respond to genistein in part via GPR30.

Figure 5.

Effect of genistein on cAMP and browning markers of SVF-derived adipocytes from GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice. A) Concentration of cAMP in SVF-derived adipocytes from GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice in the presence og genistein or vehicle. B) Protein abundance of the thermogenic genes UCP-1, PGC1α, TBX1 in SVF-derived adipocytes from GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice in the presence og genistein or vehicle., and densitometric analysis of C) UCP-1, D) PGC1α, and E) TBX1. Results are showed as the means ± S.E.Ms. (n = 5 by group). Two-way ANOVA was performed, letters indicate significant differences between groups (a>b>c).

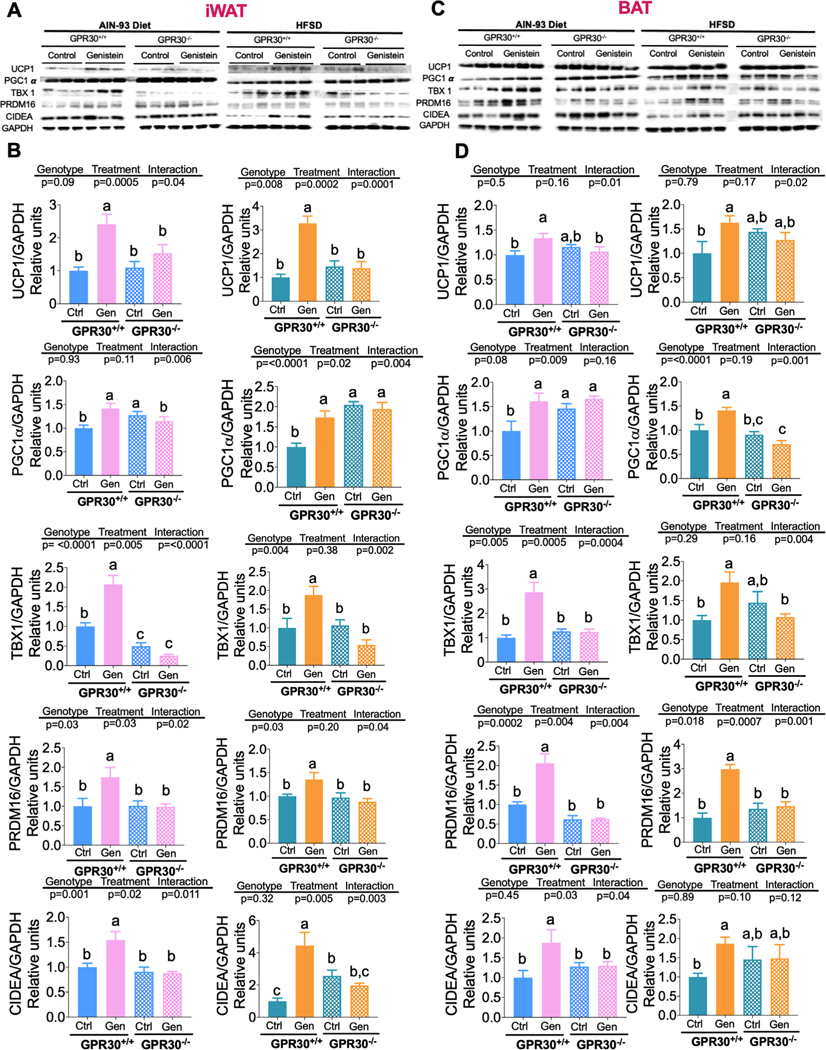

3.6. Genistein Increases Thermogenic Capacity in GPR30+/+ Mice

Since we observed that genistein was able to increase the expression of thermogenic markers in white adipocytes derived from GPR30+/+ but not from GPR30−/− mice, we then assessed whether genistein was also able to increase the thermogenic capacity via GPR30 in vivo in inguinal WAT (iWAT) or in BAT, from GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice. Similar to what was observed in cultured adipocytes, genistein was able to induce the thermogenic program by modulating the expression of UCP1 as well as some browning markers including PGC1α, TBX-1, PRDM16, and CIDEA in iWAT and in BAT and this effect was stronger in the presence of GPR30. In iWAT, genistein increased the abundance of UCP1 protein in GPR30+/+ mice and this was accompanied by a significant increase in all browning markers assessed in mice fed a control or HFSD diet (Figure 6A). In GPR30−/− mice fed a control diet or a HFSD supplemented with genistein, there was no significant increase in UCP1 protein abundance compared with the non-supplemented corresponding groups (Figure 6B). Furthermore, in GPR30−/− mice fed either control or HFSD, there was no significant increase in any of the browning markers as a consequence of genistein supplementation. These results showed that genistein is able to activate the browning signature; however, this effect was in part GPR30-dependent (Figure 6A,B). In addition, our data showed that genistein increased UCP1 abundance and brown adipocyte markers in BAT from GPR30+/+ but not from GPR30−/− mice, regardless of the type of diet (Figure 6C,D). Altogether, these results support our previous findings which showed that GPR30 mediates some of the mitochondrial effects of genistein, such as increased maximal respiration and spare capacity of SVF-derived adipocytes. The increase in these parameters indicates an improvement in the oxidative capacity of the cell which, based on the observed differences in UCP1 expression, suggests that the increase in oxidative capacity could be associated with the process of mitochondrial uncoupling. However, other respirometric effects promoted by genistein were not dependent on the presence of GPR30, including basal and ATP-associated respiration, thus further investigations are needed to establish the mechanism involved in this effect of genistein. An interesting finding is that in both iWAT and BAT from GPR30−/− mice, the protein abundance of PGC1α was elevated under basal conditions compared to GPR30+/+ mice, which may partly explain the elevated maximal respiration observed in control GPR30−/− SVF-derived adipocytes.

Figure 6.

Effects of genistein on the protein abundance of thermogenic markers in iWAT and BAT from GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice. A) Immunoblotting and B) Densitometric analysis of UCP-1, PGC1α, TBX1, PRDM16, and CIDEA proteins from iWAT of GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− fed control diet with or without genistein, C) Immunoblotting, and D) Densitometric analysis of UCP-1, PGC1α, TBX1, PRDM16, and CIDEA protein from BAT of GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− fed HFSD with or without genistein. Results are showed as the means ± S.E.Ms. (n = 6 by group). Two-way ANOVA was performed, letters indicate significant differences between groups (a>b>c).

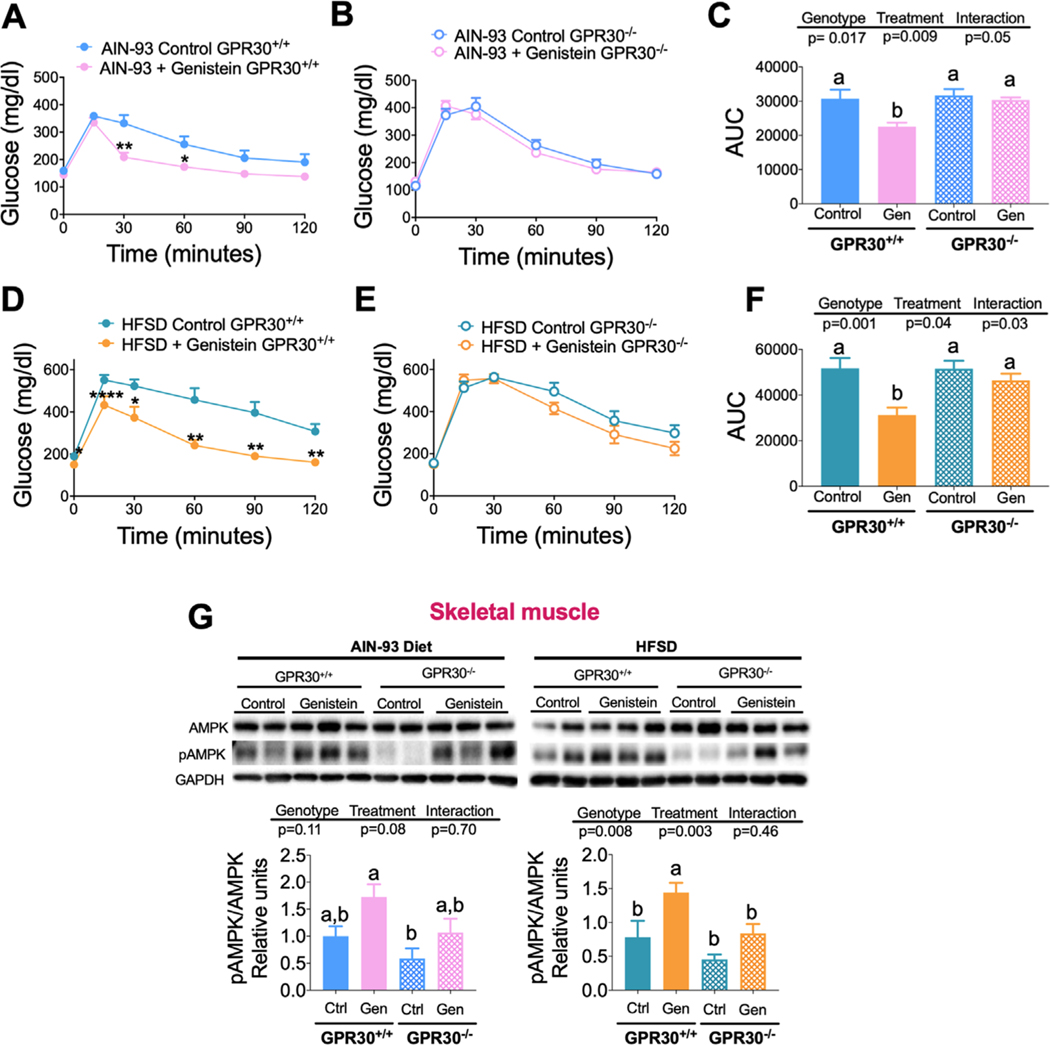

3.7. Genistein Improves Glucose Tolerance Only in GPR30+/+ Mice

An increase of WAT functionality is associated with an improvement of glucose tolerance.[35,36] Thus, we studied whether genistein consumption modified glucose tolerance through GPR30, by performing glucose tolerance tests. Our data showed that genistein improved glucose tolerance in GPR30+/+ mice (Figure 7A–F) fed control diet or HFSD, but this effect was not observed in GPR30−/− mice. In GPR30+/+ mice fed control diet or HFSD, genistein reduced the area under the curve (AUC) of the glucose tolerance test by 26.8% and 39.3%, respectively (Figures 6F and 7C). In GRP30−/− mice fed control or HFSD, genistein had a small tendency to decrease AUC, but it was not statistically significant. These results suggest that the enhancement of glucose tolerance by genistein is diminished in the absence of GPR30. Since skeletal muscle is the main organ involved in glucose uptake, metabolism and therefore glucose tolerance, we measured the phosphorylation of AMPK. Previous evidence showed that genistein can stimulate fatty acid oxidation in muscle cells by increasing AMPK phosphorylation, and thereby improving glucose to lerance.[20,37] The results showed that similar to the glucose tolerance response, GPR30+/+ mice increased AMPK phosphorylation in greater extent than GPR30−/− mice. This effect was more evident in mice fed a HFSD (Figure 7G). These results indicate that genistein improves glucose tolerance by increasing AMPK phosphorylation in mice expressing GPR30.

Figure 7.

Effects of genistein on glucose tolerance in GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− fed with control and HFSD with or without genistein. Glucose tolerance test (GTT) performed in A) GPR30+/+ mice and B) GPR30−/− mice fed a control diet with or without genistein, C) area under the curve after a GTT of GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− fed a control diet with or without genistein. Glucose tolerance test performed on D) GPR30+/+ mice and E) GPR30−/− mice fed a HFSD with or without genistein, F) area under curve after a GTT of GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− fed a HFSD with or without genistein, G) immunoblotting and densitometric analysis of total AMPK and phospho-AMPK in skeletal muscle of GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− fed a control diet or HFSD with or without genistein. GTT was performed by an intraperitoneal injection of 2 g kg−1 glucose and the area under curve was calculated. Results are shown as the mean ± S.E.M. (n = 5/8 by group). For GTT analysis, an unpaired Student’s t-test was performed, * p = 0.05, ** p = 0.002, *** p = 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001. For AUC and Western blot analysis, a two-way ANOVA was performed, letters indicate significant differences between groups, (a>b>c).

4. Discussion

In the past few years, the relevance of discovery of new compounds and pharmacological targets has increased in an effort to develop new treatments for diminishing the effects of obesity. Several studies on genistein consumption in either mice or humans have demonstrated that this bioactive compound can increase energy expenditure and the thermogenic capacity of WAT. In addition, genistein also improves insulin sensitivity, associated with an increase in fatty acid oxidation.[20,23,37] However, there is not enough evidence regarding how genistein can cause these metabolic improvements. A few studies have suggested that genistein generate some of these metabolic benefits by inducing the activity of the thermogenic program, increasing mitochondrial capacity and modifying WAT metabolism.[17,18] Here, we provide evidence that these effects are in part mediated through GPR30.

The involvement of GPR30 as a mediator of genistein effects of has been suggested in different fields of study, but it has not been related to the metabolic effects of genistein on thermogenesis and insulin resistance. GPR30 is highly expressed in ovaries, brain, placenta, liver, heart, pancreas, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue,[38,39] which implies it could be important for many metabolic processes. However, the function and its role in mediating genistein effects has only been described in the pancreas.[40]

The study showed that GPR30−/− mice gained less body weight than GPR30+/+ mice, independently of the type of diet consumed. This finding is consistent with a previous study in which GPR30 deletion was found to reduce adipogenic differentiation of adipose tissue-derived stromal vascular cells, leading to a decrease in body weight gain and fat mass in diet-induced obesity; however, this effect was only observed in female mice, not in males.[41]

Genistein supplementation reduced body weight gain in both genotypes, this was accompanied by a reduction in body fat percentage, particularly in mice fed a HFSD, however, the reduction in body fat was greater in GPR30+/+ compared to GPR30−/− mice. These effects were independent on food intake, since mice of both genotypes had similar energy intake, suggesting that the difference in the decrease of body weight and body fat between GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice could be associated with changes in energy expenditure.

There is evidence that genistein has the capacity to increase oxygen utilization and therefore increase energy expenditure even with the consumption of a HFSD.[19,20] In this study, we also demonstrated that genistein can promote an increase in oxygen consumption in both GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice, however, in mice fed either a control or a HFSD we found that GPR30−/− mice had a lower oxygen consumption and energy expenditure by gram of fat when compared to GPR30+/+ mice. This is in agreement with previous studies that showed that male GPR30−/− mice consume less oxygen than GPR30+/+ mice.[30] Interestingly, we observed that genistein could increase oxygen consumption in GPR30−/− mice, but this effect was less pronounced than in GPR30+/+ mice. Remarkably, we observed that this difference was dependent on oxygen consumption or energy expenditure when expressed in terms of fat mass, implying that the effect of genistein depends in part on the presence of GPR30 in adipose tissue, since the fat mass of GPR30−/− mice was less active in the presence of genistein.

The capacity of adipose tissue to increase energy expenditure depends in part on the mitochondrial activity of adipocytes. We found in SVF-derived adipocytes that genistein was able to stimulate an increase in maximal respiration and spare capacity. These two parameters are associated with the oxidative capacity of the cell, indicating that genistein increases the utilization of fatty acids as substrates in adipose tissue, an effect that was GPR30-dependent. This is consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated that genistein increases fatty acids oxidative capacity in skeletal muscle of GPR30+/+ mice.[19] Surprisingly, GPR30−/− cells without genistein stimulation, showed higher maximal respiration compared to cells expressing GPR30, indicating higher mitochondrial capacity. This could be partly associated with the fact that GPR30−/− adipocytes may have more mitochondrial content or that their mitochondria are more active compared to GPR30+/+ cells. Interestingly, we found that expression of PGC1α protein abundance in GPR30−/− mice was higher compared with GPR30+/+ mice, suggesting that these mice may have more mitochondrial biogenesis capacity, however, further studies are needed to understand this possibility. In addition, our results suggest that there are some genistein-promoted mitochondrial effects that are not GPR30-dependent, such as respiration linked to ATP production. Further research is needed to establish the molecular mediators of the increased mitochondrial respiration of GPR30-deficient cells and the GRP30-independent effects of genistein.

There is evidence that genistein can increase thermogenic capacity through an increase in UCP1 expression [16,17] which could be linked with an increase in the reserve capacity of mitochondrial function in both WAT and BAT. Our in vitro results suggest that the increase in the expression of thermogenic genes is mediated by an increase in cAMP, since genistein stimulated cAMP production in GPR30+/+ adipocytes, an effect that was not observed in GPR30−/− cultured adipocytes. These results are in agreement with a previous study conducted in ß-cells which showed that genistein increases cAMP levels through GPR30.[42] It was previously reported that genistein induces the browning signature in iWAT.[17,18] Interestingly, the upregulation we observed in cAMP levels was accompanied by a significant increase in the protein abundance of UCP1, PGC1α, and TBX1 in adipocytes from GPR30+/+ mice stimulated with genistein, and in our in vivo study, this expression pattern was also observed in iWAT and BAT from GPR30+/+ mice treated with genistein, whereas in GPR30−/− mice this effect was much less pronounced. This evidence suggests that the increase in energy expenditure as a consequence of genistein consumption is partly associated with an increase in WAT browning, but only in mice expressing GPR30. In fact, this effect was reflected in the oxygen consumption when expressed as a function of grams of fat mass, since GPR30+/+ mice fed a control diet showed an increase in this parameter when the mice were supplemented with genistein, while in GPR30−/− mice a decrease was observed when the mice were also supplemented with genistein. We also observed that in BAT, UCP1 protein abundance increased due to the consumption of genistein in GPR30+/+ mice that were fed either control or HFSD diet, this effect did not occur in GPR30−/− mice. It is noteworthy that in GPR30−/− mice fed with HFSD without genistein the UCP1 protein content in BAT was increased, without a corresponding increase of browning markers, indicating that some other modifications may occur in the absence of GPR30. Different responses between WAT and BAT have been previously observed in mice treated with angiotensin (1–7).[43] Further studies are needed to understand this observation.

The results obtained in this study show that, in addition to the effects of genistein on WAT mitochondrial respiration, genistein improved glucose tolerance through GPR30. Improvement of glucose tolerance is one of the previously reported effects of genistein consumption[17] and GPR30 has been shown to be involved in glucose homeostasis.[29,44] It has been previously reported that GPR30−/− mice show impaired insulin secretion and altered glucose tolerance. However, no changes in insulin signaling have been described.[28,29,44] Skeletal muscle is the main organ involved in glucose tolerance, depending on its insulin response capacity based on the phosphorylation of several enzymes including AMPK. We found that AMPK phosphorylation by genistein occurred in GPR30+/+ mice, particularly in HFSD-fed mice, which may partially explain the differences in glucose tolerance between GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice.

Regarding serum fasting insulin concentrations, GPR30−/− mice that were fed a HFSD did not show the same increase in insulin concentrations as the GPR30+/+ mice, this is consistent with a previous report showing that GPR30 is important for pancreatic ß-cell survival,[45] as the absence of this receptor decreases insulin secretion, which was evident in GPR30−/− mice consuming the HFSD but not on a control diet. The role of GPR30 in insulin secretion may also explain why GPR30−/− animals were less glucose tolerant. It was observed that genistein decreased cholesterol concentrations in GPR30−/− mice, even though GPR30 activation has been reported to be associated with an increase in LDL receptor expression and, consequently, a decrease in plasma cholesterol.[46,47] However, as we have already reported there is evidence that genistein present in soy protein stimulates the expression of fibroblast growth factor 15,[48] which promotes a decrease in serum cholesterol concentrations, which could be occurring in our study.

Although we have identified several GPR30-dependent effects of genistein, a limitation of our study is that at this point we cannot establish whether these effects are through direct or indirect activation of GPR30 by genistein. However, direct activation of GPR30 by genistein is possible, since evidence shows that genistein can bind to GPR30 in plasma membranes of HEK293 cells transfected with this receptor.[49] Therefore, further research is needed to demonstrate the direct binding of genistein to GPR30 in adipocytes. Another limitation of our study is that mice used had the same C57BL/6 background but were obtained from homozygous breeders. However, GPR30+/+ and GPR30−/− mice had the same oxygen consumption in basal conditions in the in vivo and ex vivo model, suggesting that, at least in that parameter, the fact that mice come from homozygous breeders was not reflected in a different phenotype.

In conclusion, our results show that GPR30 mediates the beneficial effects of genistein, thus promoting thermogenesis in WAT. Among the aforementioned GPR30-dependent effects, we found that genistein enhanced the mitochondrial oxidative capacity in adipocytes. As a consequence, the lack of GPR30 decreased oxygen consumption and energy expenditure in vivo, both parameters were modified by genistein in mice fed control and HFSD. Furthermore, the lack of this receptor reduced the beneficial effect of genistein on glucose tolerance. Taken together, these results reveal the involvement of GPR30 as a mediator of genistein’s effects on adipose tissue, describing a new mechanism by which this bioactive compound enhances metabolism with potential applications for obesity-related diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by CONACYT (ART 261843). S.V.R. received scholarship from CONACYT, Programa de Maestría y Doctorado en Ciencias Bioquímicas, UNAM. Graphical Abstract was designed with BioRender.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Saraí Vásquez-Reyes, Departamento de Fisiología de la Nutrición, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, México, CDMX México.

Ariana Vargas-Castillo, Departamento de Fisiología de la Nutrición, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, México, CDMX México.

Lilia G. Noriega, Departamento de Fisiología de la Nutrición, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, México, CDMX México

Laura A. Velázquez-Villegas, Departamento de Fisiología de la Nutrición, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, México, CDMX México

Berenice Pérez, Departamento de Fisiología de la Nutrición, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, México, CDMX México.

Mónica Sánchez-Tapia, Departamento de Fisiología de la Nutrición, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, México, CDMX México.

Guillermo Ordaz, Departamento de Fisiología de la Nutrición, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, México, CDMX México.

Renato Suárez-Monroy, Departamento de Fisiología de la Nutrición, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, México, CDMX México.

Alfredo Ulloa-Aguirre, Red de Apoyo a la Investigación, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México-Instituto Nacional de, Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, Mexico City, CDMX México.

Halina Offner, Neuroimmunology Research, R&D-31, VA Portland Health Care System, 3710 SW U.S. Veterans, Hospital Rd., Portland, OR 97239, USA; Department of Neurology, Oregon Health & Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Rd, Portland, OR 97239, USA; Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Rd, Portland, OR 97239, USA.

Nimbe Torres, Departamento de Fisiología de la Nutrición, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, México, CDMX México.

Armando R. Tovar, Departamento de Fisiología de la Nutrición, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, México, CDMX México

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.

References

- [1].Blüher M, Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jaacks LM, Vandevijvere S, Pan A, McGowan CJ, Wallace C, Imamura F, Mozaffarian D, Swinburn B, Ezzati M, Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Haslam DW, James WP, Lancet 2005, 366, 1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Schrauwen P, Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2011, 301, R285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hill James O, Wyatt Holly R, Peters John C, Circulation 2012, 126, 126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Romieu I, Dossus L, Barquera S, Blottiere HM, Franks PW, Gunter M, Hwalla N, Hursting SD, Leitzmann M, Margetts B, Nishida C, Potischman N, Seidell J, Stepien M, Wang Y, Westerterp K, Winichagoon P, Wiseman M, Willett WC, I. w. g. o. E., Cancer Causes Control 2017, 28, 247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Choe SS, Huh JY, Hwang IJ, Kim JI, Kim JB, Front Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2016, 7, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vegiopoulos A, Rohm M, Herzig S, EMBO J. 2017, 36, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rui L, Compr. Physiol. 2017, 7, 1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bartelt A, Heeren J, Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Harms M, Seale P, Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kuryłowicz A, Puzianowska-Kuźnicka M, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kaisanlahti A, Glumoff T, J. Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 75, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Concha F, Prado G, Quezada J, Ramirez A, Bravo N, Flores C, Herrera JJ, Lopez N, Uribe D, Duarte-Silva L, Lopez-Legarrea P, Garcia-Diaz DF, Rev.Endocr. Metab. Disord 2019, 20, 161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Silvester AJ, Aseer KR, Yun JW, J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 64, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Vargas-Castillo A, Fuentes-Romero R, Rodriguez-Lopez LA, Torres N, Tovar AR, Arch. Med. Res. 2017, 48, 401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Palacios-González B, Vargas-Castillo A, Velázquez-Villegas LA, Vasquez-Reyes S, López P, Noriega LG, Aleman G, Tovar-Palacio C, Torre-Villalvazo I, Yang LJ, Zarain-Herzberg A, Torres N, Tovar AR, J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 68, 59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].López P, Sánchez M, Perez-Cruz C, Velázquez-Villegas LA, Syeda T, Aguilar-López M, Rocha-Viggiano AK, Del Carmen Silva-Lucero M, Torre-Villalvazo I, Noriega LG, Torres N, Tovar AR, Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, e1800313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Palacios-González B, Zarain-Herzberg A, Flores-Galicia I, Noriega LG, Alemán-Escondrillas G, Zariñan T, Ulloa-Aguirre A, Torres N, Tovar AR, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1841, 132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Guevara-Cruz M, Godinez-Salas ET, Sanchez-Tapia M, Torres-Villalobos G, Pichardo-Ontiveros E, Guizar-Heredia R, Arteaga-Sanchez L, Gamba G, Mojica-Espinosa R, Schcolnik-Cabrera A, Granados O, López-Barradas A, Vargas-Castillo A, Torre-Villalvazo I, Noriega LG, Torres N, Tovar AR, BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care. 2020, 8, e000948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Amanat S, Eftekhari MH, Fararouei M, Bagheri Lankarani K, Massoumi SJ, Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yang R, Jia Q, Mehmood S, Ma S, Liu X, Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Maggiolini M, Vivacqua A, Fasanella G, Recchia AG, Sisci D, Pezzi V, Montanaro D, Musti AM, Picard D, Andò S, J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 25, 27008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mizukami Y, Endocr. J. 2010, 57, 101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Prossnitz ER, Arterburn JB, Sklar LA, Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2007, 265–266, 138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wei W, Chen ZJ, Zhang KS, Yang XL, Wu YM, Chen XH, Huang HB, Liu HL, Cai SH, Du J, Wang HS, Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wang C, Dehghani B, Magrisso IJ, Rick EA, Bonhomme E, Cody DB, Elenich LA, Subramanian S, Murphy SJ, Kelly MJ, Rosenbaum JS, Vandenbark AA, Offner H, Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 22, 636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sharma G, Prossnitz ER, Endocrinology 2011, 152, 3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sharma G, Hu C, Brigman JL, Zhu G, Hathaway HJ, Prossnitz ER, Endocrinology 2013, 154, 4136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Davis KE, Carstens EJ, Irani BG, Gent LM, Hahner LM, Clegg DJ, Horm. Behav. 2014, 66, 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Nie Y, Gavin TP, Kuang S, Bio. Protoc 2015, 5, e1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tschop MH, Speakman JR, Arch JR, Auwerx J, Bruning JC, Chan L, Eckel RH, Farese RV Jr., Galgani JE, Hambly C, Herman MA, Horvath TL, Kahn BB, Kozma SC, Maratos-Flier E, Muller TD, Munzberg H, Pfluger PT, Plum L, Reitman ML, Rahmouni K, Shulman GI, Thomas G, Kahn CR, Ravussin E, Nat. Methods 2011, 9, 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kaiyala KJ, Schwartz MW, Diabetes 2011, 60, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Fernandez-Verdejo R, Ravussin E, Speakman JR, Galgani JE, Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Longo M, Zatterale F, Naderi J, Parrillo L, Formisano P, Raciti GA, Beguinot F, Miele C, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kahn CR, Wang G, Lee KY, J. Clin. Invest. 2019, 129, 3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Palacios-González Z-HA, Flores-Galicia I, Noriega LG, Alemán-Escondrillas G, Zariñan T, Ulloa-Aguirre A, Torres N, Tovar AR, Bioch. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1841, 132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Shi H, Kumar SPDS, Liu X, Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2013, 114, 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hugo ER, Brandebourg TD, Woo JG, Loftus J, Alexander JW, Ben-Jonathan N, Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Luo J, Wang A, Zhen W, Wang Y, Si H, Jia Z, Alkhalidy H, Cheng Z, Gilbert E, Xu B, Liu D, J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 58, 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wang A, Luo J, Moore W, Alkhalidy H, Wu L, Zhang J, Zhen W, Wang Y, Clegg DJ, Bin X, Cheng Z, McMillan RP, Hulver MW, Liu D, Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Luo J, Wang A, Zhen W, Wang Y, Si H, Jia Z, Alkhalidy H, Cheng Z, Gilbert E, Xu B, Liu D, J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 58, 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Vargas-Castillo A, Tobon-Cornejo S, Del Valle-Mondragon L, Torre-Villalvazo I, Schcolnik-Cabrera A, Guevara-Cruz M, Pichardo-Ontiveros E, Fuentes-Romero R, Bader M, Alenina N, Vidal-Puig A, Hong E, Torres N, Tovar AR, Metabol.–Clin,Exp. 2020, 103, 154048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Mårtensson UEA, Salehi SA, Windahl S, Gomez MF, Swärd K, Daszkiewicz-Nilsson J, Wendt A, Andersson N, Hellstrand P, Grände P-O, Owman C, Rosen CJ, Adamo ML, Lundquist I, Rorsman P, Nilsson B-O, Ohlsson C, Olde B. r., Leeb-Lundberg LMF, Endocrinology 2009, 150, 687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Liu S, Le May C, Wong WPS, Ward RD, Clegg DJ, Marcelli M, Korach KS, Mauvais-Jarvis F, Diabetes 2009, 58, 2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Feldman RD, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 760.27213340 [Google Scholar]

- [47].Hussain Y, Ding Q, Connelly Philip W, Brunt JH, Ban Matthew R, McIntyre Adam D, Huff Murray W, Gros R, Hegele Robert A, Feldman Ross D, Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, 213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Arellano-Martínez GL, Granados O, Palacios-González B, Torres N, Medina-Vera I, Tovar AR, Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Thomas P, Dong J, Steroid Biochem J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 102, 175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.