Abstract

Background

It is not known whether sotrovimab, a neutralizing monoclonal antibody (mAb) treatment authorized for early symptomatic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients, is also effective in preventing the progression of severe disease and mortality following severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Delta variant infection.

Methods

In an observational cohort study of nonhospitalized adult patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, 1 October 2021–11 December 2021, using electronic health records from a statewide health system plus state-level vaccine and mortality data, we used propensity matching to select 3 patients not receiving mAbs for each patient who received outpatient sotrovimab treatment. The primary outcome was 28-day hospitalization; secondary outcomes included mortality and severity of hospitalization.

Results

Of 10 036 patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, 522 receiving sotrovimab were matched to 1563 not receiving mAbs. Compared to mAb-untreated patients, sotrovimab treatment was associated with a 63% decrease in the odds of all-cause hospitalization (raw rate 2.1% vs 5.7%; adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.37; 95% confidence interval [CI], .19–.66) and an 89% decrease in the odds of all-cause 28-day mortality (raw rate 0% vs 1.0%; aOR, 0.11; 95% CI, .0–.79), and may reduce respiratory disease severity among those hospitalized.

Conclusions

Real-world evidence demonstrated sotrovimab effectiveness in reducing hospitalization and all-cause 28-day mortality among COVID-19 outpatients during the Delta variant phase.

Keywords: real-world evidence, COVID-19, sotrovimab, outpatients, mortality

Real-world evidence demonstrates that sotrovimab, a neutralizing monoclonal antibody (mAb), significantly reduces 28-day hospitalization and mortality rates when administered to high-risk outpatients recently infected with SARS-CoV-2 during the Delta variant phase, compared to a propensity-matched cohort of mAb-untreated outpatients.

High rates of transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19), persist, especially among unvaccinated individuals or those with waning vaccine or infection-related immunity [1]. Neutralizing monoclonal antibody (mAb) treatment provides short-term passive protection against SARS-CoV-2. Several mAb products have received emergency use authorization (EUA) from the US Food and Drug Administration [2] based on phase 2/3 randomized clinical trials conducted earlier in the pandemic that demonstrated efficacy towards reduced hospitalization and disease severity among high-risk outpatients [3–5]. Use of mAb products such as sotrovimab for individuals who have recently tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in the outpatient setting is critical to mitigate virus-driven impact on the health care system and is also an evidence-based treatment strategy to improve COVID-19 outcomes among high-risk individuals.

Trials supporting mAb EUA approval were conducted prior to the emergence of the Delta variant surge in the summer 2021, including the COMET-ICE trial that found a significant reduction in risk of a composite end point of all-cause hospitalization or death following sotrovimab treatment [4]. Following EUA, however, it becomes more challenging to recruit patients into randomized controlled trials [6]. As new variants such as Delta, or variant lineages such as Omicron BA.1, BA.1.1, or BA.2, emerge analysis of real-world data sufficiently robust to evaluate important clinical differences is critical to evaluate treatment effectiveness and inform policy and practice decisions, as others have successfully done [7–11]. We previously used a real-world platform to report on mAb efficacy during the Delta variant pandemic phase [12]. That prior report focused on mAbs administered through September 2021, predominantly consisting of casivirimab plus imdevimab (approximately 80%), bamlanivimab (approximately 15%), or bamlanivimab plus etesevimab (approximately 3%). Sotrovimab had been administered to only 0.7% of the overall cohort of patients with the Delta variant, thus additional data on its clinical effectiveness is warranted.

To provide useful data to help inform mAb allocation strategies and related policymaking, we leveraged our novel real-world evidence platform [12–14] to assess the clinical impact of sotrovimab therapy on high-risk outpatients with early symptomatic COVID-19 infections during a SARS-CoV-2 Delta predominant period in Colorado (1 October 2021 to 11 December 2021) [15]. This paper reports on the effectiveness of sotrovimab against progression of COVID-19 to severe disease, hospitalization, severity of hospitalization, and death.

METHODS

Study Oversight and Data Sources

We conducted a propensity-matched observational cohort study, as part of a statewide implementation/effectiveness pragmatic trial, in a collaboration between University of Colorado researchers, University of Colorado Health (UCHealth) leaders, and the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent. We obtained data from the electronic health record (EHR; Epic, Verona, WI) of UCHealth, the largest health system in Colorado with 13 hospitals around the state and 141 000 annual hospital admissions, using Health Data Compass, an enterprise-wide data warehouse. EHR data were merged with statewide data on vaccination status from the Colorado Comprehensive Immunization Information System and mortality from Colorado Vital Records.

Patient Population Studied

We included patients diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection between 1 October 2021 and 11 December 2021 allowing for at least 28 days of follow-up (n = 10 036; Supplementary Figure 1). Patients were identified using an EHR-based date of SARS-CoV-2 positive test (by polymerase chain reaction or antigen) or date of administration of mAb treatment (if no SARS-CoV-2 test result date available). The decision to seek mAb treatment was made by patients and clinicians [15]. We did not exclude patients solely for lack of EUA eligibility based on EHR data, because not all eligibility criteria were consistently available in the EHR. We excluded patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on the same day of or during hospitalization because they had already reached the primary end point of hospitalization at the time of treatment. We also excluded patients missing both a positive test date and a sotrovimab administration date (n = 708), or if it had been more than 10 days between the positive test date and sotrovimab administration (n = 26), resulting in a cohort of sotrovimab (n = 566) or mAb untreated (n = 9470) patients.

Nearest neighbor propensity matching was conducted using logistic regression with treatment status as the outcome. Approximately 3 untreated patients (n = 1563) were matched to each sotrovimab-treated patient (n = 522) [16, 17]. Only 42 sotrovimab-treated patients were lost due to incomplete covariate data. The propensity model included categorial age, sex, race/ethnicity, obesity status, immunocompromised status, number of comorbid conditions other than obesity and immunocompromised status, number of vaccinations at time of infection, and insurance status. We assessed effectiveness of matching using standardized mean differences with a threshold of 0.1, with results shown in Supplementary Table 2 [18].

Outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause hospitalization within 28 days of a positive SARS-CoV-2 test, obtained from EHR data. Secondary outcomes included 28-day all-cause mortality, emergency department (ED) visit within 28 days, in-hospital disease severity based on maximum level of respiratory support, hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) lengths of stay (LOS) in survivors, rates of ICU admission, and in-hospital mortality. For both hospitalization and ED visits, the index visit was used. When mAb-treated patients were missing a SARS-CoV-2 positive date (70.5%), we randomly imputed missing test dates from the distribution of observed time between SARS-CoV-2 to mAb administration.

Variable Definitions

Hospitalization was defined as any inpatient or observation encounter documented in the EHR. ED visits were defined as any visit to the ED, with or without an associated inpatient or observation encounter. Presence of comorbid conditions and immunocompromised status were determined as reported previously [12], as defined by the Charlson and Elixhauser Comorbidity Indices and by immune-suppressing medications, described further in the Supplementary material. The number of comorbid conditions was calculated as the sum of the presence of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, pulmonary disease, and renal disease.

COVID-19 disease severity was estimated using ordinal categories of respiratory support requirements at an encounter level, based on the highest level of support received among the following types (in increasing order): no supplemental oxygen, standard (nasal cannula/face mask) oxygen, high-flow nasal cannula or noninvasive ventilation, and invasive mechanical ventilation [19]. In-hospital mortality was the highest level of disease severity.

No virus sequencing results were available on an individual patient basis. However, this analysis focused on a period when the Delta variant was dominant (>99% by statewide data) [15] and coupled with the timing of sotrovimab EUA and distribution in Colorado. Vaccination status was categorized by the number of vaccinations (0, 1, 2, or ≥ 3) administered prior to the date of the SARS-CoV-2 positive test.

The variables of interest include treatment status, categorical age in years, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance status, obesity status, immunocompromised status, number of additional comorbid conditions, and number of vaccinations. Due to small sample sizes, the variables age, race/ethnicity, insurance status, number of comorbid conditions, and vaccination status were each collapsed to the groups shown in the results tables.

Statistical Analysis

Firth’s logistic regression was used to assess the association between treatment and 28-day hospitalization, 28-day mortality, and 28-day ED visits. Firth’s logistic regression (R package logistf V 1.24) addresses estimation issues related to low event rates and complete separation [20–22]. All models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance status, obesity status, immunocompromised status, number of additional comorbid conditions, and number of vaccinations. The unadjusted number needed to treat (NNT) was calculated for hospitalization by treatment status. Due to the small number of hospitalized participants, descriptive statistics including counts and raw rates were calculated for all secondary outcomes among hospitalized participants, including disease severity, hospital LOS, ICU visit, and ICU LOS.

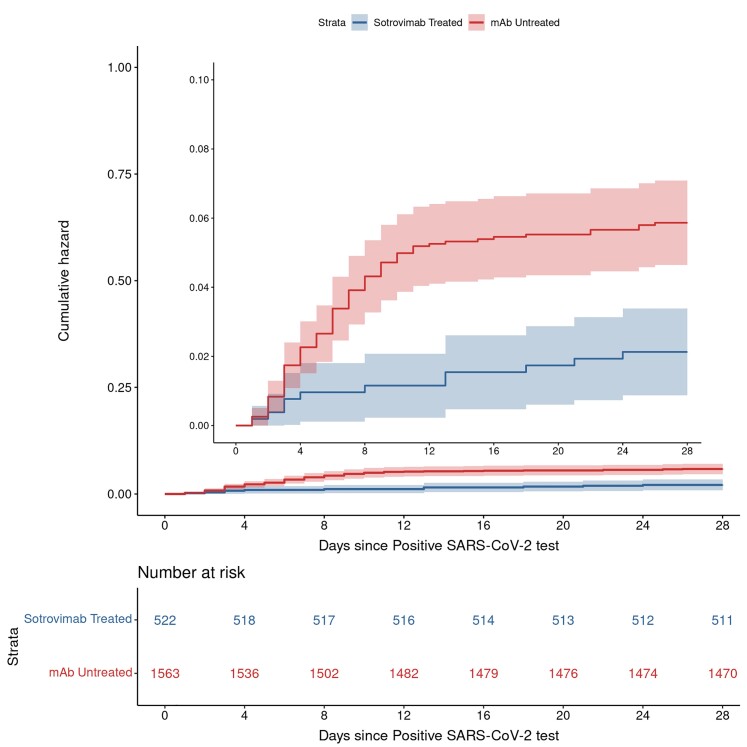

Kaplan-Meier curves were estimated to visually assess cumulative incidence patterns by treatment status for 28-day hospitalization. Additional Kaplan-Meier curves were estimated to explore the potential impact of imputation method, assessing time to event from positive test date or from time of mAb administration, by observed or imputed test date.

Two sensitivity analyses were performed. First, we repeated the above analysis using only EUA-eligible patients as verified by available EHR data. Second, we repeated the above analysis with a more conservative SARS-CoV-2 imputation approach where all missing positive test dates were imputed as 10 days prior to the mAb administration date (the maximum time difference allowed by the EUA). All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (version 3.6.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing) [23].

RESULTS

Characteristics of Sotrovimab-Treated and mAb-Untreated Cohorts

Of 10 036 patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in the full cohort, 566 subjects received mAbs and 9470 patients did not (Supplementary Table 1). In the full cohort, the sotrovimab-treated group generally reflects EUA criteria for use of mAbs, with many being older (33.0% were age ≥65 years vs 11.4% in mAb-untreated group), more likely to be obese (24.0% vs 16.8%), or having 1 or more comorbidities (49.1% vs 36.5%). Propensity matching eliminated clinically meaningful differences in matching variables between groups (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2). The 522 sotrovimab-treated patients were propensity matched to 1563 untreated patients.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by mAb Treatment Status for Primary Matched Cohort

| Characteristic | Sotrovimab Treated (N = 522) | mAb Untreated (N = 1563) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group, ya | ||

| 18–44 | 169 (32.4) | 486 (31.1) |

| 45–64 | 177 (33.9) | 537 (34.4) |

| ≥65 | 176 (33.7) | 540 (34.5) |

| Sexa | ||

| Female | 296 (56.7) | 877 (56.1) |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 421 (80.7) | 1271 (81.3) |

| Hispanic, any race | 39 (7.5) | 118 (7.5) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 21 (4.0) | 57 (3.6) |

| Other | 41 (7.9) | 117 (7.5) |

| Insurance statusa | ||

| Private/commercial | 294 (56.3) | 876 (56.0) |

| Medicare | 175 (33.5) | 534 (34.2) |

| Medicaid | 34 (6.5) | 99 (6.3) |

| None/uninsured | 13 (2.5) | 39 (2.5) |

| Other/unknown | 6 (1.1) | 15 (1.0) |

| Immunocompromised statusa | ||

| Yes | 130 (24.9) | 347 (22.2) |

| Obesity statusa | ||

| Yes | 133 (25.5) | 394 (25.2) |

| Number of other comorbid conditionsa | ||

| None | 251 (48.1) | 767 (49.1) |

| 1 | 147 (28.2) | 421 (26.9) |

| 2 or more | 124 (23.8) | 375 (24.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 62 (11.9) | 209 (13.4) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 86 (16.5) | 242 (15.5) |

| Pulmonary disease | 131 (25.1) | 390 (25.0) |

| Renal disease | 32 (6.1) | 112 (7.2) |

| Hypertension | 160 (30.7) | 497 (31.8) |

| Liver disease | 39 (7.5) | 114 (7.3) |

| Number of vaccinations prior to SARS-CoV-2–positive datea | ||

| 0 | 200 (38.3) | 604 (38.6) |

| 1 | 37 (7.1) | 109 (7.0) |

| 2 | 233 (44.6) | 699 (44.7) |

| ≥3 | 52 (10.0) | 151 (9.7) |

Data are No. (%).

Abbreviations: mAb, monoclonal antibody; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Variables used in the propensity matching.

The characteristics of sotrovimab-treated and mAb-untreated patients in the matched cohort are presented (Table 1). The age distribution was similar, with 34% age ≥65 years. The cohort was 56% female, 81% non-Hispanic white, and 56% had private/commercial insurance. Hypertension (32%) and pulmonary disease (25%) were the most common comorbid conditions. Notably, 54% had received at least 2 vaccinations at the time of infection, and 39% had not received any vaccine doses. The mean time from positive SARS-CoV-2 test to administration of sotrovimab treatment was 3.7 days (SD 1.8) in those who did not have an imputed positive test date.

Hospitalization and Mortality

Sotrovimab treatment was associated with a lower rate of 28-day hospitalization compared to matched mAb-untreated controls (11 [2.1%] vs 89 [5.7%]), representing a 63% decrease in the adjusted odds of hospitalization (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.37; 95% confidence interval [CI], .19–.68; P < .001; Table 2). The unadjusted NNT for hospitalization for the untreated group was 28. Based on a time-to-event analysis, the benefits associated with reduced hospitalization were largely accrued within 10–12 days of the positive or imputed SARS-CoV-2 test date (Figure 1), or an average of 9 days after sotrovimab treatment. Kaplan-Meier curves assessing time to event from positive test date or from time of mAb administration, by observed or imputed test date, did not reveal differences to suggest an inadequate imputation method (Supplementary Figures 2–4). Other factors associated with hospitalization are in Supplementary Table 3. Covariates that were associated with increased odds of 28-day hospitalization included age ≥ 65 years (P = .049), obesity (P < .001), and 1 (P = .013) or 2 or more (P < .001) comorbid conditions other than obesity or immunocompromised status (Supplementary Table 3). Each level of vaccination status (1, 2, or ≥ 3 doses) was significantly associated with decreased odds of hospitalization in comparison to having no vaccine.

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes by Monoclonal Antibody Treatment Status

| Outcome | Sotrovimab Treated | mAb-Untreated | Adjusted OR | (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall sample size | n = 522 | n = 1563 | ||

| All-cause 28-day hospitalization, primary outcome | 11 (2.1) | 89 (5.7) | 0.37 | (.19–.68) |

| All-cause 28-day mortality | 0 (0.0) | 15 (1.0) | 0.11 | (.00–.79) |

| Any ED visit to day 28 | 44 (8.4) | 119 (7.6) | 1.12 | (.77–1.60) |

| Hospitalized sample size | n = 11 | n = 89 | ||

| Hospital LOS days, mean (SD) | 5.3 (5.9) | 9.4 (10.6) | … | … |

| IMV or death | 0 (0.0) | 19 (21.3) | … | … |

| ICU admission | 2 (18.2) | 19 (21.3) | … | … |

| ICU LOS days, mean (SD) | 5.5 (6.4) | 8.6 (10.1) | … | … |

Data are No. (%) except where indicated. All regression models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, obesity, immunocompromised status, number of comorbidities, insurance status, and vaccination status.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; LOS, length of stay; mAb, monoclonal antibody; OR, odds ratio; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence plots for all-cause hospitalization to day 28 by sotrovimab treatment status. Compares cumulative incidence of hospitalizations between sotrovimab-treated (blue line) versus mAb-untreated (red line) patients. Shading represents 95% confidence intervals around estimates for each line. The main y-axis represents the full 0 to 1.00 scale, and the inset is a magnified version of a 0 to 0.10 scale. Abbreviations: mAb, monoclonal antibody; SARS-CoV-2 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Importantly, all-cause 28-day mortality in the sotrovimab-treated group was 0 (0%) compared to 15 (1.0%) among the mAb-untreated group, equating to an 89% decrease in the mortality odds (aOR, 0.11; 95% CI, .0–.79; Table 2). There was not a significant association between sotrovimab treatment and the odds of visiting the ED (aOR, 1.12; 95% CI, .77–1.60).

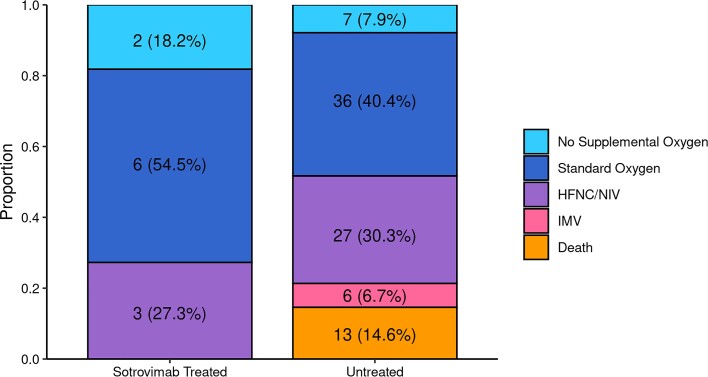

Severity of Hospitalization

Among hospitalized patients, 0 of 11 (0%) in the sotrovimab-treated group required invasive mechanical ventilation or died in the hospital, compared to 19 of 89 (21.3%) mAb-untreated group (Table 2). We also observed that a higher proportion of sotrovimab-treated patients required no supplemental oxygen or only required standard (low-flow) oxygen in comparison to mAb-untreated patients (72.7% vs 48.3%). The average hospital LOS for sotrovimab patients was 5.3 (SD 5.9) days in comparison to 9.4 (SD 10.6) days in the untreated group. Collectively, these data suggest a lower severity of disease among hospitalized sotrovimab-treated patients, although statistical inference was not performed (Figure 2). Two of 9 (18.2%) sotrovimab-treated patients required ICU level of care, a similar percentage compared to mAb-untreated patients (21.3%).

Figure 2.

Maximum respiratory support by monoclonal antibody treatment status among patients hospitalized within 28 days. Comparing severity of hospitalizations for n = 11 sotrovimab-treated and n = 89 mAb-untreated patients, the maximum level of respiratory support appeared lower for sotrovimab-treated patients, but inferential statistics were not able to be performed. Abbreviations: HFNC, high-flow nasal cannula oxygen; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; mAb, monoclonal antibody; NIV, noninvasive ventilation.

Sensitivity Analysis

Neither restricting the cohort to only patients meeting EUA eligibility criteria based on available EHR data or using a more conservative imputation method for missing date of positive SARS-CoV-2 test materially changed the key results and scientific conclusions (Supplementary Tables 4–7).

DISCUSSION

During a SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant-predominant period in Colorado, sotrovimab reduced 28-day hospitalization by 63% and all-cause 28-day mortality by 89%. Our study adds to the main prior clinical trial demonstrating sotrovimab efficacy that occurred prior to the emergence of the Delta variant, [4] and builds on a prior real-world analysis from another major US health system [7]. This data on the effectiveness of sotrovimab to prevent severe COVID-19 disease induced by the Delta variant may be critical given the unpredictable nature of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, in vitro studies demonstrate that sotrovimab effectively neutralizes Omicron B.1.1.529 and BA.1 variants [24], but was less effective against Omicron BA.2 and its sublineages [25, 26]. These data are supported by recent real-world clinical data suggesting ineffectiveness and a trend towards higher rates of progression to severe, critical, or fatal COVID-19 among sotrovimab-treated patients in Qatar during a BA.2 Omicron subvariant-dominant period [27]. Collectively, these data demonstrate the importance of rapid in vitro and clinical data for sotrovimab or other potential therapies to curb severity of disease derived from future variants of concern.

Although we do not directly compare sotrovimab effectiveness to other mAbs used during a Delta variant-dominated pandemic phase [7], it is notable that the adjusted OR for 28-day hospitalization in our study (aOR 0.37) is similar to what we previously reported (aOR 0.48) when casivirimab plus imdevimab, bamlanivimab, or bamlanivimab plus etesevimab use as outpatient mAb therapy were far more common than sotrovimab [12]. Further supporting sotrovimab effectiveness against the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 is a comparable NNT of 28 to prevent 1 hospitalization, which we observed despite both an increase in the overall vaccination rate and a lower baseline hospitalization rate among mAb-untreated patients compared to the earlier cohort [12].

Our results are of practical importance for policymakers and clinicians because there have been shortages of mAb supplies and infusion capacity and, as such, demonstrating their effectiveness to reduce hospitalization and mortality against each clinically relevant SARS-CoV-2 variant is crucial [28]. Study findings support continued use of sotrovimab for COVID-19 outpatients with Delta variant or other potential variants with similar properties to the Delta variant, particularly those with high baseline risk for progression to hospitalization or death.

This study has several limitations. The setting was a single health system and geographically limited to one US state with relatively low racial and ethnic minority representation, although it serves both urban and rural populations through academic and community hospitals. Even though we used statewide data for mortality and vaccination status, hospitalizations were collected only within a single health system. If mAb-untreated patients were less likely to be seen in this health system, hence more likely to be hospitalized elsewhere, this may bias our results toward the null. We also relied on EHR data, including manual chart reviews, which may have missing or inaccurate information about the presence of chronic conditions [29]. These factors might have limited our ability to detect the impact of sotrovimab treatment.

We only collected 28-day hospitalization and mortality data, and therefore we do not know whether sotrovimab effectiveness extends to a longer period after SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, our prior study would suggest that 28-day and 90-day data are similar with respect to hospitalization and mortality end points [12]. In this study, propensity scoring appropriately matched mAb-treated and mAb-untreated patient groups across multiple variables, but unmeasured confounders may remain. Our EHR data does not contain information on SARS-CoV-2 variants at the patient level. However, during Colorado’s Delta phase more than 99% of sequenced SARS-CoV-2 was Delta variant [15].

Finally, this study was conducted during a limited portion of the Delta variant-dominant period after sotrovimab drug distribution and infusion had been well-established in Colorado. In addition, hospitalization rates were lower over this same period, precluding our ability to perform inferential statistics on severity of illness among the hospitalized subcohort. Because a sotrovimab benefit towards reducing disease severity and hospitalization has been observed in 2 independent health systems, we are more confident that future SARS-CoV-2 variants that share features with SARS-CoV-2 Delta may be worth evaluating for sotrovimab effectiveness in a real-world setting. With the rapid emergence of Omicron variants of concern starting in mid-December 2021, our intent is to separately evaluate sotrovimab effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron after enough treated and untreated cases have accrued and prior to its EUA being revoked on 5 April 2022 [30].

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrated real-world evidence for effectiveness of sotrovimab treatment in reducing hospitalizations among COVID-19 outpatients during the Delta variant phase, as well as a remarkable 89% overall reduction in mortality at 28 days, compared to matched mAb-untreated patients. For hospitalized patients, prior outpatient sotrovimab treatment may reduce respiratory disease severity, hospital length of stay, and death, but a larger cohort is necessary to further examine this observation. When access to mAbs is limited, prioritizing patients at highest risk for hospitalization can reduce health system strain during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Neil R Aggarwal, Department of Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Laurel E Beaty, Department of Biostatistics and Informatics, Colorado School of Public Health, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Tellen D Bennett, Section of Informatics and Data Science, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA; Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Nichole E Carlson, Department of Biostatistics and Informatics, Colorado School of Public Health, Aurora, Colorado, USA; Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Christopher B Davis, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Bethany M Kwan, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA; Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA; Department of Family Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

David A Mayer, Department of Biostatistics and Informatics, Colorado School of Public Health, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Toan C Ong, Section of Informatics and Data Science, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Seth Russell, Section of Informatics and Data Science, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Jeffrey Steele, Research Informatics, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Adane F Wogu, Department of Biostatistics and Informatics, Colorado School of Public Health, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Matthew K Wynia, Department of Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA; Center for Bioethics and Humanities, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA; Department of Health Systems Management and Policy, Colorado School of Public Health, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Richard D Zane, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Adit A Ginde, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA; Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers UL1TR002525, UL1TR002535-03S3, and UL1TR002535-04S2).

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Science brief: SARS-CoV-2 infection-induced and vaccine-induced immunity. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/science-briefs/vaccine-induced-immunity.html. Accessed April 25. [PubMed]

- 2. COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment guidelines. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov. Accessed April 27.

- 3. Dougan M, Nirula A, Azizad M, et al. Bamlanivimab plus etesevimab in mild or moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:1382–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gupta A, Gonzalez-Rojas Y, Juarez E, et al. Effect of sotrovimab on hospitalization or death among high-risk patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2022; 327:1236–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, et al. REGN-COV2, a neutralizing antibody cocktail, in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:238–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lynch HF, Caplan A, Furlong P, Bateman-House A. Helpful lessons and cautionary tales: how should COVID-19 drug development and access inform approaches to non-pandemic diseases? Am J Bioeth 2021; 21:4–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huang DT, McCreary EK, Bariola JR, et al. Effectiveness of casirivimab and imdevimab, and sotrovimab during Delta variant surge: a prospective cohort study and comparative effectiveness randomized trial. medRxiv [preprint], 27 December 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.12.23.21268244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8. O’Horo JC, Challener DW, Speicher L, et al. Effectiveness of monoclonal antibodies in preventing severe COVID-19 with emergence of the Delta variant. Mayo Clin Proc 2022; 97:327–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ganesh R, Pawlowski CF, O’Horo JC, et al. Intravenous bamlanivimab use associates with reduced hospitalization in high-risk patients with mild to moderate COVID-19. J Clin Invest 2021; 131:e151697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Razonable RR, Pawlowski C, O’Horo JC, et al. Casirivimab-imdevimab treatment is associated with reduced rates of hospitalization among high-risk patients with mild to moderate coronavirus disease-19. EClinicalMedicine 2021; 40:101102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jarrett M, Licht WB, Bock K, et al. Early experience with neutralizing monoclonal antibody therapy for COVID-19. JMIRx Med 2021; 2(3):e29638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12. Wynia MK, Beaty LE, Bennett TD, et al. Real world evidence of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies for preventing hospitalization and mortality in COVID-19 outpatients. medRxiv [preprint], 11 January 2022. doi: 10.1101/2022.01.09.22268963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13. International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research . About real-world evidence. December 2021. https://www.ispor.org/strategic-initiatives/real-world-evidence/about-real-world-evidence. Accessed 25 April 2022.

- 14. Angus DC. Optimizing the trade-off between learning and doing in a pandemic. JAMA 2020; 323:1895–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment . COVID-19 treatments. https://covid19.colorado.gov/for-coloradans/covid-19-treatments#collapse-accordion-40911-4. Accessed February 10.

- 16. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res 2011; 46:399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ho DE, King G, Stuart EA. Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Anal 2007; 15:199–236. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med 2009; 28:3083–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. National Institute of Health. COVID-19 treatment guidelines. Clinical spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 infection. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/overview/clinical-spectrum. Accessed April 25.

- 20. Heinz G, Ploner M. Logistf: Firth’s Bias-Reduced Logistic Regression. R package version 1.24. 2020. https://cran.r-project.org/package=logistf. Accessed 16 February 2022.

- 21. Heinze G, Schemper M. A solution to the problem of separation in logistic regression. Stat Med 2002; 21:2409–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Puhr R, Heinze G, Nold M, Lusa L, Geroldinger A. Firth's logistic regression with rare events: accurate effect estimates and predictions? Stat Med 2017; 36:2302–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cameroni E, Saliba C, Bowen JE, et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies overcome SARS-CoV-2 Omicron antigenic shift. Nature 2022; 602:664–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25. Iketani S, Liu L, Guo Y, et al. Antibody evasion properties of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages. Nature 2022; 604:553–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Takashita E, Kinoshita N, Yamayoshi S, et al. Efficacy of antiviral agents against the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Subvariant BA.2. N Engl J Med 2022; 386: 1475–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zaqout A, Almaslamani MA, Chemaitelly H, et al. Effectiveness of the neutralizing antibody sotrovimab among high-risk patients with mild to moderate SARS-CoV-2 in Qatar. medRxiv [preprint], 22 April 2022. doi: 10.1101/2022.04.21.22274060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28. National Academies . Strategies to allocate scarce COVID-19 monoclonal antibody treatments to eligible patients examined in new rapid response to government. January 2021. https://www.nationalacademies.org/news/2021/01/strategies-to-allocate-scarce-covid-19-monoclonal-antibody-treatments-to-eligible-patients-examined-in-new-rapid-response-to-government. Accessed April 25.

- 29. Bennett TD, Moffitt RA, Hajagos JG, et al. Clinical characterization and prediction of clinical severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection among US adults using data from the US National COVID Cohort Collaborative. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2116901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Food and Drug Administration . FDA updates sotrovimab emergency use authorization. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-updates-sotrovimab-emergency-use-authorization. Accessed 29 April 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.