Abstract

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is a concern given its prevalence and harmful consequences such as depression, anxiety, substance misuse, and low academic performance, which pose great threats to children’s sustainable development. In response, teachers must be empowered to play crucial roles in preventing CSA and intervening to avert CSA-related harm. We therefore explored the potential for online teacher training to improve teachers’ preventive outcomes of CSA (awareness, commitment, and confidence in reporting) and student outcomes (CSA knowledge and ability to recognize, refuse, and report CSA). To assess the immediate effect of online teaching training, we analyzed pre-and post-test data from the implementation of the Second Step Child Protection Unit (CPU) on 131 teachers and 2,172 students using a multilevel structural equation modeling approach. We found a significant direct effect of online teacher training on improving teachers’ preventive outcomes. Furthermore, we detected a significant indirect effect of online teacher training on children’s preventive outcomes of CSA knowledge and ability to recognize, refuse, and report CSA via teachers’ preventive outcomes of CSA awareness.

Keywords: online teacher training, CSA, teachers, students, SEM

Introduction

Although child sexual abuse (CSA) rates have declined since the 1990s (Fallon et al., 2019), CSA affects millions of children worldwide (Barth et al., 2013). In the United States alone, approximately 60,000 children are impacted each year (Guastaferro et al., 2019). Countries all over the world should be alarmed by CSA’s high occurrence rate, and the sustainable development goals (SDGs) of promoting the health and education of children that governments have agreed upon (United Nations, 2015) cannot be reached unless CSA is prevented. CSA-affected children experience multiple challenges that may hinder their academic achievement, likelihood of graduating from high school, mental and psychological health, and social adjustment (Amédée et al., 2019; Ensink et al., 2019; McTavish et al., 2019).

Since the passage of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act in 1974 in the United States, prevention efforts have been developed and implemented to address various types of child maltreatment including CSA (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2019; Dahlberg & Mercy, 2009; Hawkins et al., 2009). However, these prevention efforts, regrettably, have suffered from a lack of a CSA focus (Fix et al., 2021; Freyd et al., 2005; Mercy, 1999). Notably, to address CSA in the U.S., national policy and resources have sought to support enactment of policies to detect, prosecute, incarcerate, and monitor offenders after CSA occurrence (Letourneau & Shields, 2017; Levenson & Letourneau, 2011). States in the U.S. have enacted mandatory reporting laws, demanding professionals who work with children to report child maltreatment cases to child protection agencies (Mathews & Kenny, 2008). The presence, content, scope, and quality of trainings for mandated reporters seem to vary across jurisdictions, but one common issue is that professionals think there is a lack of training to help them complete their duties adequately (Christian, 2008; Kenny, 2004; Starling et al., 2009). Increasingly, teachers have received a great deal of attention in prevention and intervention efforts intended to address CSA’s high prevalence rate and serious adverse consequences. Teachers are in an excellent position to educate children about sexual abuse and self-protection and to notice sudden changes in children’s behavior that may indicate abuse (Nickerson et al., 2010; Renk et al., 2002). However, despite their critical role in children’s lives and obligation to report suspected abuse, most teachers lack sufficient knowledge to identify potential cases of CSA and are unfamiliar with their schools’ procedures for reporting their suspicions (Kenny, 2004; Kleemeir et al., 1988; Marquez-Flores et al., 2016). Furthermore, one-third of teachers underreport child abuse, partially due to their fear that they would make inaccurate reports or would not be supported by administrators when reporting child abuse (Kenny, 2001, 2004; Walsh et al., 2008, 2010; Webster et al., 2005).

To help teachers address issues that may hinder them from executing CSA prevention and intervention plans effectively, we investigated the potential of teaching training. While teacher trainings have received attention as a key factor to improve teachers’ knowledge and skills (Avalos, 2011; Darling-Hammond & McLaughlin, 2011), there have been concerns over low participation and high attrition rate of teacher training despite great investments on teacher training (Kazemi & Hubbard, 2008; Ke et al., 2019). The reasons for low participation and high attrition rate can include the followings: lack of policy to promote teachers’ participation in training opportunities (e.g., teacher evaluation policy and compensation policy); scheduling issues and time constraints; and logistical barriers during school hours, short-staffing issues, and high turnover rates (Akiba, 2015; Akiba et al., 2015; Levi et al., 2021; Rheingold et al., 2015). Online teacher training is a cost-effective and accessible method of training teachers who face time and location limitations but have reliable Internet access (Davies & Tedesco, 2018; Jung, 2005). Such training can also address barriers associated with teacher turnover and attrition, as new teachers can receive training upon employment (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017). Moreover, some studies’ findings have indicated promising positive effects of online teacher training (Shaha & Ellsworth, 2013). Previous studies also revealed that CSA prevention programs for teachers resulted in significant increases in knowledge, opinions, and anticipated behaviors when dealing with children who experienced CSA (Kleemeier et al., 1988; Rheingold et al., 2015), as well as teachers’ readiness and willingness to take further prevention and intervention actions (Gushwa et al., 2019).

The effectiveness of online teacher training requires further investigation, however, as there are conflicting results related to online teacher training compared with face-to-face training. In some studies, results indicated that the effects of online teacher training were not different from (Jang, 2008; Kirtman 2009) or were worse than (Kissau, 2015) face-to-face training. To ensure that online teacher training is a viable solution, its quality must be guaranteed by ensuring that it is pedagogically sound and grounded in learning theories, regardless of its delivery mode (Stes et al., 2010). In addition, a robust study design (e.g., pretest and posttest designs and the adoption of a control group) is necessary to evaluate online teacher training (Rienties et al., 2013). There is a lack of full participation for teachers in face to face training on child maltreatment including CSA; therefore, online teacher training, featuring the flexibility of representation of the online contents and teachers’ choice of those needed contents, has great potential to promote teachers’ participation in CSA training (Kenny et al., 2017).

To contribute to the data on the effects of online teacher training, we investigated the effect of the Second Step Child Protection Unit (CPU) online teacher training, which is a component of a larger CSA school-based prevention program (http://www.cfchildren.org/child-protection). In the light of online teacher training’s potential for equipping teachers to play a crucial role in CSA prevention and intervention implementation, we explored whether and how such training can improve important teacher outcomes, represented here by teachers’ CSA knowledge, confidence, and commitment to their mandated reporters’ roles (Bear et al., 2014; Kenny 2001; Walsh et al., 2010). To carry out this empirical investigation, we used data from 161 teachers and 2,172 students who participated in the Second Step CPU. We applied multilevel structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses, which are suitable for exploring the direct effect of this online teacher training on teachers’ CSA preventive outcomes, as well as any cross-level indirect effects on student outcomes, using Mplus 8.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2018). Specifically, we examined the cross-level indirect effect of online teacher training on students’ CSA knowledge and their ability to recognize, refuse, and report CSA incidents (Tutty, 1995; Wurtele et al., 1998) through teacher outcomes. In addition, in exploring the direct and indirect effects, we controlled for covariates such as teachers’ and students’ prior outcomes, as well as their characteristics (e.g., teaching experience and student gender), which could contribute to respective teacher and student outcomes. The following research questions guided our study:

Does the online CPU teacher training result in improvements in teacher preventive outcomes (e.g., teacher CSA knowledge, confidence, and commitment)?

Does the CPU teacher training promote student outcomes (CSA knowledge and the ability to recognize, refuse, and report CSA) indirectly via teacher outcomes?

Methods

Participants and Recruitment

The sample consisted of 131 Pre-K to Grade 4 teachers (93.2% female; 83 in the intervention condition and 78 in the control condition) and 2,172 students (51% female; 1,151 in the intervention condition and 1,021 in the control condition). At the start of the 2017–2018 school year, parents of all students enrolled in Pre-K-Grade 4 were mailed a letter informing them about the study and instructing them to return a signed opt-out form only if they were unwilling for their child to participate in the assessments. This passive consent procedure was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the school district. Teachers were also informed about the study and consented to participant. Of the total population in the eight schools, 88.3% of students and 96.4% of teachers participated in the study. There were no significant demographic differences between the control and intervention groups. For teachers in the control and intervention groups, teaching experience ranged from 1 to 36 years (M = 15.40, SD = 7.40). In addition, 97.5% of the teachers were Caucasian, 0.6% were members of other races, and 1.9% did not report their race.

Students’ ages ranged from 4 to 12 years (M = 7.19, SD = 1.58). The students’ grades ranged from Pre-K to Grade 4 as follows: Pre-K = 110 (5.1%), K = 264 (12.2%), Grade 1 = 324 (14.9%), Grade 2 = 307 (14.1%), Grade 3 = 623 (28.7%), and Grade 4 = 544 (25%). District-level demographics indicated that 61% of students were White (non-Hispanic); 14% were Black (non-Hispanic); 15% were Hispanic; 7% were multiracial; and 3% were American Indian, Alaskan, Asian, or Pacific Islander; 43% of all students were eligible for free or reduced lunch. Students became eligible for free/reduced lunch based on their household income and size. Annual Household Income Limits (before taxes) is $25,142 for a household size of 1 with $8,732 added per additional person (https://www.benefits.gov/benefit/2007).

Procedure

Teachers completed the pretest survey electronically via Survey Monkey one week prior to beginning the CPU teacher training modules, which lasted from August to October in 2017. Teachers in the intervention condition completed two online training modules: All-Staff Training (75–90 min) and Teach the Lesson (45–60 min for Early Learning, 60–75 min for Grades K–5). In the All-Staff Training module, teachers learned to recognize signs of abuse, respond protectively to children who experience abuse, and report abuse by working with various children suffering from abuse in realistic scenarios. In the Teach the Lesson module, teachers learned to implement the 6-lesson CPU curriculum to students, involve families, and overcome uneasy feelings when talking to students about sexually abusive touch.

In these training modules, teachers learned from multiple cases of students who revealed varied signs of abuse (e.g., a striking change in their emotional state, declining grades). Although the training provided common signs to look out for related to CSA, the training also emphasized the importance of building supportive relationships with students (that aids in being able to effectively recognize signs of abuse). Within the training, teachers were prepared to interact with students in ways that they have never thought of (e.g., telling students that it wasn’t their fault). Teachers also had the opportunity to reflect on whether they might overlook those signs and whether they tend not to report such signs because they worry about negative consequences of reporting. These cases addressed misconceptions, biases, and fears that adversely affect teachers’ confidence in responding to students and reporting suspected abuse. Furthermore, the training modules provided helpful prevention resources to reinforce the lesson, thus helping schools increase their CSA knowledge and bolster their related practices and policies.

Teachers in the control condition conducted “business as usual” and did not complete the online modules. Within one week of the completion and implementation of the CPU curriculum, teachers completed the posttest online via Survey Monkey. This period lasted from November 2017 to February 2018.

Graduate research assistants completed training in research ethics, standardization procedures, and guidelines for assessing children. A detailed administration procedure was developed, which all students studied and practiced, with feedback provided. The graduate research assistants administered pretest assessments to the students by reading the instructions and all items in an individual, small-group, or whole-class format from August to October in 2017. Prior to administering the assessments, research assistants read the child assent. Across the pre- and post-test, 102 students did not provide assent and engaged in another activity (e.g., reading, computer time). Students in Grades 2–4 took the surveys online via Survey Monkey, whereas students in Pre-K–Grade 1 received paper-and-pencil surveys in an individual or small-group format. Posttest administration, which took place from November 2017 to February 2018, followed the same procedures. The research team worked closely with the school administrators and counselors, and if there were any participants showing signs of distress, they were referred to the school counselor.

Measures

Participating teachers and students were asked to complete the measures described below. Teachers in the intervention and control groups completed measures for awareness, commitment, and confidence. Participating students in the intervention and control groups completed measures on their CSA knowledge and ability to recognize, refuse, and report CSA.

Awareness

We employed a subscale of the widely used Educators and Child Abuse Questionnaire (ECAQ; Kenny 2001) to assess the educators’ awareness of the signs and symptoms of child abuse. The ECAQ is a measure of educators’ knowledge and awareness of child abuse and related policies. We used the awareness subscale (α = 0.77–0.87) to represent teachers’ competence in identifying and assessing child abuse (e.g., “I am aware of the signs of child sexual abuse.”). Response items featured a Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater awareness of child abuse.

Commitment and Confidence

To evaluate teacher commitment and confidence, we used two subscales from the Teacher Reporting Attitude Scale-Child Sexual Abuse (TRAS-CSA; Walsh et al., 2010). The commitment scale (6 items, α = 0.71–0.80) assessed teachers’ commitment to their role as mandated reporters (e.g., “It is important for teachers to be involved in reporting child sexual abuse to prevent long-term consequences for children.”). The confidence scale (5 items, α = 0.76–0.82) evaluated teachers’ attitude toward reporting child abuse to Child Protective Services (e.g., “I would be apprehensive to report child sexual abuse for fear of family/community retaliation.”). Respondents provided answers using a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). Negatively worded items were reverse coded, so higher scores indicated a greater commitment and a more positive attitude about reporting (confidence).

CSA Knowledge

The Child Knowledge Abuse Questionnaire – Revised (CKAQ-R; Tutty, 1995) was used to assess elementary school students’ knowledge of child abuse prevention concepts. The CKAQ-R was utilized as a measure of prevention concepts for students as it has a wider range of item difficulty and was therefore less vulnerable to ceiling effects. The revised true-false questionnaire contains 24 items assessing core concepts identified in child sexual abuse prevention programs (e.g. body ownership, good touch versus bad touch, no secrets, identification of strangers, permission to tell, fault and blame, touching by familiar people and boys’ risk of sexual abuse). Language was adapted to fit terminology consistent with the CPU curriculum (e.g. safe and unsafe touches versus good or bad touch). Correct responses received a score of 1 point and incorrect or skipped responses received 0 points, with a maximum score of 24 points. The CKAQ-R has an internal consistency of 0.87, and test-retest reliability of 0.88 (Tutty, 1995).

Ability to Recognize, Refuse, and Report CSA

An adapted version of the What-If Situations Test-III-R (WIST-R; Wurtele et al., 1988; Wurtele et al., 1998) was used to assess children’s ability to recognize, refuse, and report CSA. The WIST-R assesses self-protection skills using situational responses to stories and includes a total of six vignettes designed to assess a child’s capability to recognize, refuse, and report CSA. The measure contains three vignettes that would be considered inappropriate requests (e.g., a neighbor wanting to take pictures of the child’s private parts), as well as three appropriate requests (e.g., a physician wanting to touch a child’s injured private parts). Children’s responses to each question received scores ranging from 0 to 2, for a potential maximum Total Skill Score of 24 points. Higher scores indicated higher skill levels. The internal reliability of the WIST-R is good, ranging from.75 to.90 (Wurtele et al., 1998).

Statistical Analysis

We conducted a two-level path analysis with a multilevel SEM framework using M-plus 8.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2018). The first level was the student level, and the second level was the teacher level. The missingness of our data ranged from 17 to 26%, and the data were detected not to be missing completely at random (MCAR; p < .01; Little & Rubin, 2019). To address missing data, we utilized a full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method due to its ability to produce less biased results like multiple imputation as a recommended strategy in a SEM context (Allison, 2012; Enders 2010; Graham, 2009; Walters & Espelage, 2017).

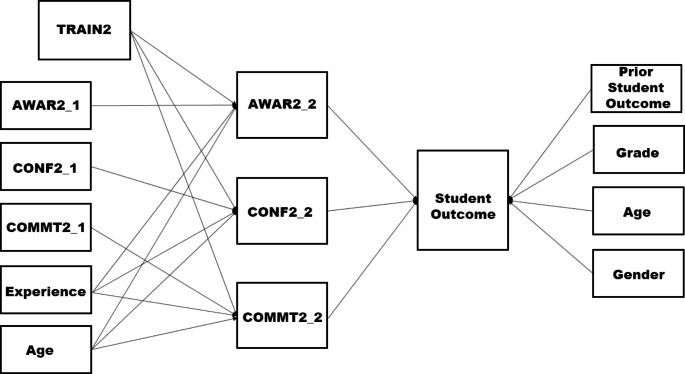

The student-level variables consisted of the following: preventive outcomes during the posttest in terms of CSA knowledge (CKAQ1_2) and ability to recognize/refuse/report CSA (WIST1_2), prior CSA knowledge (CKAQ1_1) and prior ability to recognize/refuse/report CSA (WIST1_1) during the pretest, grade, gender, and age. The teacher-level variables consisted of the following: teacher training (PD2); preventive outcomes during the posttest in terms of CSA awareness (AWAR2_2), confidence (CONF2_2), and commitment (COMMT2_2); prior outcomes during the posttest represented by CSA awareness (AWAR2_1), confidence (CONF2_1), and commitment (COMMT2_1); teaching experience; and age. By using these variables, we built two models with the CKAQ and WIST as student outcomes, respectively (see Fig. 1 for details).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual Diagram with All Variables

When performing a multilevel analysis, it is advisable to check the between-group variability (Lachowicz et al., 2015). The estimates of multilevel analyses, particularly those involving cross-level indirect effects, might be biased with a low proportion of between-group variability (i.e., the proportion of variance between groups) if the intraclass correlation (ICC) is less than 0.05. In addition, to assess the model fit, we used chi-square statistics, as well as the following additional fit statistics and their respective acceptable criteria: standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) ≤ 0.10, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.08, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) ≥ 0.90, and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) ≥ 0.90 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2015; Marsh et al., 2004).

Results

CKAQ Model

The ICC revealed that 16.2% of the variance in CKAQ1_2 was at the teacher level, supporting our adoption of a multilevel framework (Preacher et al., 2011). The model fit results showed a marginally acceptable fit for the overall model: chi-square = 149.984 (p < .001), RMSEA = 0.046, CFI/TLI = 0.951/0.914, and SRMR (within/between) = 0.079/0.105 (Bollen & Long, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2015; Marsh et al., 2004; Mills et al., 2012).

Within-Level Results

Teacher-Level Results

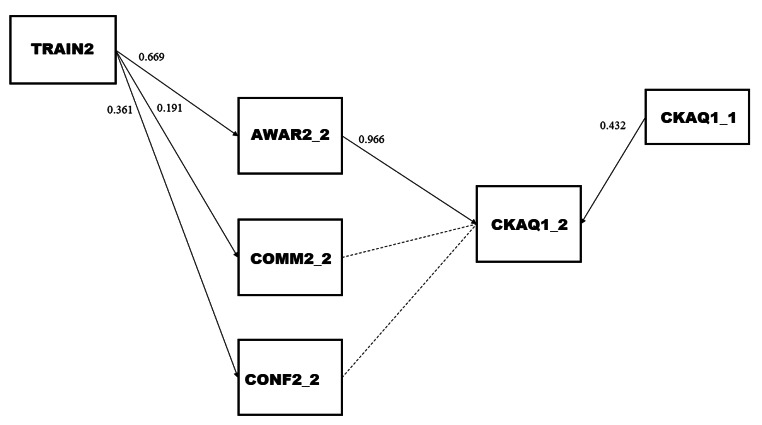

Table 1; Fig. 2 show that the teacher training (TRAIN2) had significant direct effects on all three teacher preventive outcomes: AWAR2_2 (β = 0.669, p < .001); COMMT2_2 (β = 0.191, p < .05); CONF2_2 (β = 0.361, p < .001). Compared with teachers in the control group, teachers in the intervention group demonstrated significantly higher levels of CSA awareness, commitment, and confidence. There was a significant positive association between pretest and posttest teacher outcomes. Teachers with a higher degree of CSA awareness, commitment, and confidence during the pretest had a tendency to display a higher degree of awareness (AWAR2_1 --> AWAR2_2: β = 0.233, p < .05), commitment (COMMT2_1 --> COMMT2_2: β = 0.616, p < .001, and confidence (CONF2_1 --> CONF2_2: β = 0.574, p < .001) during the posttest.

Table 1.

SEM Based Multilevel Analysis: Individual Parameter Estimates

| CKAQ | Teacher Level | Student Level | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWAR2_2 | COMMT2_2 | CONF2_2 | CKAQ1_2 | ||||||||||||||

| Teacher-Level | |||||||||||||||||

| TRAIN2 | 0.669*** | 0.191* | 0.361*** | - | |||||||||||||

| AWAR2_2 | - | - | - | 0.966*** | |||||||||||||

| COMMT2_2 | - | - | - | 0.063 | |||||||||||||

| CONF2_2 | - | - | - | 0.328 | |||||||||||||

| AWAR2_1 | 0.233* | - | - | - | |||||||||||||

| COMMT2_1 | 0.616*** | - | - | ||||||||||||||

| CONF2_1 | - | - | 0.574*** | - | |||||||||||||

| EXPERIENCE | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.006 | - | |||||||||||||

| AGE | 0.050 | 0.008 | 0.018 | - | |||||||||||||

| Student-Level | |||||||||||||||||

| CKAQ1_1 | - | - | - | 0.432*** | |||||||||||||

| GRADE | - | - | - | 0.414 | |||||||||||||

| AGE | - | - | - | -0.119 | |||||||||||||

| GENDER | - | - | - | -0.229 | |||||||||||||

| WIST | Teacher Level | Student Level | |||||||||||||||

| AWAR2_2 | COMMT2_2 | CONF2_2 | WIST1_2 | ||||||||||||||

| Teacher-Level | |||||||||||||||||

| TRAIN2 | 0.674*** | 0.170** | 0.350*** | - | |||||||||||||

| AWAR2_2 | - | - | - | 2.785*** | |||||||||||||

| COMMT2_2 | - | - | - | -0.482 | |||||||||||||

| CONF2_2 | - | - | - | -0.638 | |||||||||||||

| AWAR2_1 | 0.214* | - | - | - | |||||||||||||

| COMMT2_1 | 0.655*** | - | - | ||||||||||||||

| CONF2_1 | - | - | 0.592*** | - | |||||||||||||

| EXPERIENCE | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.014 | - | |||||||||||||

| AGE | 0.093 | 0.032 | 0.008 | - | |||||||||||||

| Student-Level | |||||||||||||||||

| WIST1_1 | - | - | - | 0.346*** | |||||||||||||

| GRADE | - | - | - | 0.028 | |||||||||||||

| AGE | - | - | - | 0.094 | |||||||||||||

| GENDER | - | - | - | 0.058 | |||||||||||||

* denotes a significance level at 0.05

** denotes a significance level at 0.01

*** denotes a significance level at 0.001

Fig. 2.

Conceptual Diagram with Parameter Estimates: CKAQ Model

Note: Paths of significant coefficients as solid lines and the paths of the nonsignificant coefficients as broken lines

Student-Level Results

There was a significant positive association between pretest and posttest student outcomes. Students with higher levels of CSA knowledge during the pretest tended to show higher levels of CSA knowledge during the posttest (CKAQ1_1 --> CKAQ1_2: β = 0.432, p < .001).

Cross-Level Effects

Further analyses showed cross-level direct effects of teacher preventive outcomes on student outcomes during the posttest. Students with teachers who had greater CSA awareness showed significantly higher ability to recognize, refuse, and report CSA (AWAR2_2 --> CKAQ1_2: β = 0.966, p < .001).

Table 2 shows cross-level indirect effects, including specific and total indirect effects (i.e., the combination of specific indirect effects). Teacher training had a significant positive total indirect effect on students’ CSA knowledge (TRAIN2 --> CKAQ1_2: βindirect_total = 0.732, p < .001). In particular, of three specific indirect effects, the indirect effect of teacher training on students’ knowledge through teachers’ awareness during the posttest was significant (TRAIN2 --> AWAR2_2 --> CKAQ1_2: βindirect_specific = 0.646, p < .001). In other words, online teacher training helped teachers improve their own CSA awareness, which influenced the increase in their students’ CSA knowledge.

Table 2.

Total Indirect, and Specific Indirect Effects

| Between Effects | Estimate | SE | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects from TRAIN to CKAQ1_2 | ||||

| Total Indirect | 0.732 | 0.163 | 0.000 | |

| Specific Indirect | ||||

| TRAIN → AWAR2_2 → CKAQ1_2 | 0.646 | 0.186 | 0.001 | |

| TRAIN → COMMT2_2 → CKAQ1_2 | 0.063 | 0.082 | 0.443 | |

| TRAIN → CONF2_2 → CKAQ1_2 | 0.023 | 0.081 | 0.778 | |

| Effects from TRAIN to WIST1_2 | ||||

| Total Indirect | 1.572 | 0.256 | 0.000 | |

| Specific Indirect | ||||

| TRAIN → AWAR2_2 → WIST1_2 | 1.877 | 0.333 | 0.000 | |

| TRAIN → COMMT2_2 → WIST1_2 | -0.082 | 0.073 | 0.263 | |

| TRAIN → CONF2_2 → WIST1_2 | -0.223 | 0.131 | 0.087 | |

WIST Model

The ICC displayed that 5.5% of the variance in WIST1_2 was detected at the teacher level, marginally supporting the multilevel analysis (Lachowicz et al., 2015). The fit statistics results showed a good fit for the overall model: chi-square = 34.818 (p > .05), RMSEA = 0.016, CFI/TLI = 0.980/0.959, and SRMR (within/between) = 0.001/0.088 (Bollen & Long, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2015; Marsh et al., 2004; Mills et al., 2012).

Within-Level Results.

Teacher-Level Results

Table 1; Fig. 3 show that the online teacher training (TRAIN2) had significant direct effects on all three teacher preventive outcomes: AWAR2_2 (β = 0.674, p < .001); COMMT2_2 (β = 0.170, p < .05); CONF2_2 (β = 0.350, p < .001). Teachers in the intervention group revealed significantly higher levels of CSA awareness, commitment, and confidence than their peers in the control group. There was a significant positive relationship between pretest and posttest teacher outcomes. Teachers with a higher level of CSA awareness, commitment, and confidence during the pretest had a tendency to demonstrate a higher level of awareness (AWAR2_1 --> AWAR2_2: β = 0.214, p < .05), commitment (COMMT2_1 --> COMMT2_2: β = 0.655, p < .001, and confidence (CONF2_1 --> CONF2_2: β = 0.592, p < .001) during the posttest.

Fig. 3.

Conceptual Diagram with Parameter Estimates: WIST Model

Note: Paths of significant coefficients as solid lines and the paths of the nonsignificant coefficients as broken lines

Student-Level Results

There was a significant positive relationship between pretest and posttest student outcomes. Students with higher degrees of ability to recognize/refuse/report CSA during the pretest tended to show higher degrees of ability to recognize/refuse/report during the posttest (WIST1_1 --> WIST1_2: β = 0.346, p < .001).

Cross-Level Effects

First, we reviewed cross-level direct effects of teacher preventive outcomes on student outcomes during the posttest. Students with teachers who had greater CSA awareness displayed significantly higher ability to recognize/refuse/report CSA (AWAR2_2 --> WIST1_2: β = 2.785, p < .001).

Then, we reviewed cross-level indirect effects as shown in Table 2. Online teacher training had a significant positive total indirect effect on students’ ability to recognize/refuse/report CSA (TRAIN2 --> WIST1_2: βindirect_total = 1.572, p < .001). Specifically, the indirect effect of online teacher training on students’ ability to recognize/refuse/report CSA through teachers’ awareness during the posttest was significant (TRAIN2 --> AWAR2_2 --> WIST1_2: βindirect_specific = 1.877, p < .001). Thus, online teacher training helped teachers improve their own CSA awareness, which in turn influenced the gains in their students’ ability to recognize/refuse/report CSA.

Discussion

The high prevalence rate and harmful outcomes of CSA are observed consistently despite international efforts to promote children’s well-being, as emphasized in the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda (UN, 2015). In response, we sought to evaluate the effectiveness of prevention and intervention efforts to ameliorate the effects of CSA by preparing teachers, who are experts in child education and development and spend time daily with children and young people (Nickerson et al., 2010; Renk et al., 2002; Rheingold et al., 2015), to recognize and respond to CSA. Our study responded to the need to evaluate online teaching training on CSA as a viable alternative to face-to-face training, partly because of cost-effectiveness and accessibility (Kenny et al., 2017; Wurtele, 2009), and added empirical evidence on the positive effects of online teacher training in improving the preventive outcomes of teachers’ CSA knowledge, confidence, and commitment. Importantly, we extended the existing evaluation studies of online teacher training by exploring its cross-level indirect effects on students’ preventive outcomes, beyond the direct effects on teachers themselves. This is a notable contribution to the field as most research has examined only teacher outcomes (e.g., Gushwa et al., 2019; Rheingold et al., 2015), as opposed to evaluating how training and prevention impacts teachers, and then subsequently impact their students.

By analyzing empirical data from an implementation of the CPU online teacher training as part of a larger CPU intervention, we found a significant effect of CPU online teacher training on improving teachers’ preventive outcomes of CSA knowledge, confidence, and commitment. These results align with those reported in prior studies on the positive association between teacher training opportunities and teacher outcomes such as CSA knowledge, attitudes, and confidence (Gushwa et al., 2019; Kleemeier et al., 1988). It is likely that the training that included multiple case examples and preparation for teachers to recognize signs, respond, and report abuse as well as teach these issues through the 6-week curriculum helped empower them with this knowledge and commitment. Results from a focus group study with teachers implementing the CPU indicated that despite some initial fear, anxiety, and feeling unprepared to address CSA, after completing the training and implementing the lessons, these educators noted the importance of and increased awareness of the topic, as well as the sense of community and support that was created (Allen et al., 2020).

Crucially, we found a significant overall indirect effect on students’ ability to recognize CSA through teacher outcomes, as well as specific indirect effect of CPU teacher training through teachers’ CSA knowledge. Our findings, which are based on empirical data for elementary school teachers from the years 2017–2018, contribute to the CSA prevention program field by addressing concerns that existing evaluation studies of CSA prevention programs in this fast-moving field have become outdated (Babtsikos, 2010; Tutty, 2014; Walsh et al., 2015) and that there is a lack of robust studies that explore the effects of teacher training on students beyond teachers (Kim at el., 2019). Also, it is important to note that our teacher training is accompanied by teachers’ implementation of their learning right after their training. Our findings render the support for incorporating the implementation into CSA prevention intervention for teachers in alignment with the guidelines of designed-based research for teachers’ professional development (Brown, 1992; Lee & Kim, 2017; Design-based Research Collective, 2003; Reeves, 2006; Wang et al., 2014).

Implications for Practice

Results from this study support the importance of school-based professional development and prevention of CSA in improving outcomes for teachers as well as their students. It is important to note that even online training modules, which offer a flexible and efficient training model, can lead to these positive outcomes. Results from this study add to the growing research base of quantitative and qualitative studies supporting the CPU (see e.g., Allen et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2019; Nickerson et al., 2019), yet this study is unique in showing that student outcomes are impacted through the CPU’s effect on teachers. Although schools and teachers are often pressed to focus on academic concerns, given the prevalence of CSA and its impact, it is critical to implement effective training and prevention programming in this context. The support from administrators and school-based mental health professionals (e.g., school counselors, school psychologists) has also been shown to be important in helping teachers to address these issues (Allen et al., 2020).

Limitations and Future Research Directions

To employ a methodologically robust approach that considered the importance of participant characteristics that can influence the effectiveness of online teacher training (Stes et al., 2012), we accounted for the characteristics of the teacher participants, such as age and teaching experiences, when exploring the effects of online teacher training. However, our current findings’ generalizability is limited, given the homogeneous composition of the study’s teacher participants, most of whom were female and Caucasian. For example, although males report more positive attitudes towards information and communications technology (ICT) than females, female participants tend to be more academically engaged and perform better than male participants in online learning environments (Cai et al., 2017; Chyung, 2007; Price, 2006). Accordingly, future studies should recruit more heterogeneous participants to explore the potential differential effect of online teacher training on participating teachers from varying gender and racial or ethnic groups (Ang, 2017; Black, 2018). Although the measures selected are the most updated and psychometrically sound available, they are still quite dated. A priority for future research should be to develop and validate measures assessing these constructs.

Given the current study’s promising results for online teacher training, future studies should consider using further innovative approaches by employing state-of-the-art ICTs such as gamification, intelligent tutoring systems, and immersive virtual reality to make online teacher training more engaging, individualized, and scalable, particularly, to incorporate the implementation aspects as a part of the intervention for teachers (Cózar-Gutiérrez & Sáez-López, 2016; Jensen et al., 2020; Ke et al., 2020). When adopting these ICTs, given the potential moderating roles of digital competency and self-efficacy for self-regulated learning (Alghamdi et al., 2020; Broadbent & Poon, 2015; Tømte et al., 2015), future studies should include in their design instruments that measure digital competency and self-regulated learning. In addition, although teachers hold favorable attitudes toward adopting state-of-the-art ICTs, they suffer from a dearth of ICT professional development (Ertmer et al., 2012), so policymakers and administrators should invest in such opportunities to help teachers to improve their ICT knowledge and skills as necessary (Vanderlinde & van Braak, 2010).

In addition, the designers and developers of future online teacher training should consider building online communities and networks that promote shared learning, reflection on practices, and emotional support among teachers (Duncan-Howell, 2010; Herrington et al., 2006; Kelly & Antonio, 2016; Macià & García, 2016). Online communities and networks can contribute to decreasing teacher attrition and turnover (Baron, 2006; Bui et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020; Shelton & Archambault, 2018) which are critical in the context of CSA prevention and intervention efforts, given the influence of long-standing positive and trusting relationships between teachers and students on student outcomes (Armstrong et al., 2017; Baker, 2006; Garbacz et al., 2014; Hughes, 2013).

Conclusion

Overall, results from this study support the effectiveness of the CPU and extend the existing research base by using a multilevel analysis within a randomized controlled trial with a large sample to show the effect of teacher training and curriculum implementation on teacher outcomes and, in turn, the impact on students. More specifically, the intervention increases teachers’ awareness of and competence in identifying CSA, which in turn led to their students’ ability to recognize, refuse, and report CSA. Although these findings do not allow us to conclude that the intervention reduces the overall prevalence or occurrence of CSA, empowering educators and their students to recognize and respond to these potentially traumatic situations and indicators is important in our comprehensive efforts to reduce this pressing societal concern.

Unlike the European countries that have implemented prevention interventions as part of their mandatory curricula (e.g., Stay Safe), and whose teachers are prepared to deliver CSA programs (MacIntyre & Carr, 1999), the US lacks national resources and policies to support CSA prevention efforts, despite their importance in addressing the adverse impacts of CSA. As a prevention effort that can be nationally disseminated, our study showed the potential of quality teacher training using an online delivery mode which promotes scalability, cost-effectiveness, efficiency, and program fidelity. Also, our study provided one viable teacher training model that existing state-sponsored online training for mandated reporters can refer to for the modification and augmentation of their CSA related contents in order to address the issues including the significant gaps in comprehensive information such as the full legal definition of sexual abuse, related child indicators, and behavioral examples (Baker et al., 2021).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Dr. Tia Kim is employed by Committee for Children.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Akiba, M. (2015). Measuring teachers’ professional learning activities in international context.Promoting and Sustaining a Quality Teacher Workforce,87–110

- Akiba M, Wang ZE, Liang G. Organizational resources for professional development: A statewide longitudinal survey of middle school mathematics teachers. Journal of School Leadership. 2015;25(2):252–285. doi: 10.1177/105268461502500203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alghamdi A, Karpinski AC, Lepp A, Barkley J. Online and face-to-face classroom multitasking and academic performance: Moderated mediation with self-efficacy for self-regulated learning and gender. Computers in Human Behavior. 2020;102:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, K. P., Livingston, J. A., & Nickerson, A. B. (2020). Child sexual abuse prevention

- education: A qualitative study of teachers’ experiences implementing the Second Step Child Protection Unit,American Journal of Sexuality Education, 15,218–245, doi:10.1080/15546128.2019.1687382

- Allison, P. D. (2012, April). Handling missing data by maximum likelihood. In SAS global forum (Vol. 2012). Statistical Horizons, Havenford, PA

- Amédée LM, Tremblay-Perreault A, Hébert M, Cyr C. Child victims of sexual abuse: Teachers’ evaluation of emotion regulation and social adaptation in school. Psychology in the Schools. 2019;56(7):1077–1088. doi: 10.1002/pits.22236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ang CS. Internet habit strength and online communication: Exploring gender differences. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;66:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JM, Haskett ME, Hawkins AL. The student–teacher relationship quality of abused children. Psychology in the Schools. 2017;54(2):142–151. doi: 10.1002/pits.21989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avalos B. Teacher professional development in teaching and teacher education over ten years. Teaching and teacher education. 2011;27(1):10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JA. Contributions of teacher-child relationships to positive school adjustment during early elementary school. Journal of School Psychology. 2006;44:211–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AJ, LeBlanc S, Adebayo T, Mathews B. Training for mandated reporters of child abuse and neglect: content analysis of state-sponsored curricula. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2021;113:104932. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.104932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron W. Confronting the challenging working conditions, of new teachers: what mentors and induction programs can do. In: Achinstein B, Athanases SZ, editors. Mentors in the making: Developing new leaders for new teachers. New York: Teachers College Press; 2006. pp. 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Barth J, Bermetz L, Heim E, Trelle S, Tonia T. The current prevalence of child sexual abuse worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Public Health. 2013;58(3):469–483. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0426-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black FV. Providing quality early childhood professional development at the intersections of power, race, gender, and dis/ability. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood. 2018;19(2):206–211. doi: 10.1177/1463949118778017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K. A., & Long, J. S. (1993). Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA:Sage Publications

- Psychology in the Schools, 52(1), 40–60. doi:10.1002/pits.21811

- Broadbent J, Poon WL. Self-regulated learning strategies & academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: A systematic review. The Internet and Higher Education. 2015;27:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AL. Design experiments: Theoretical and methodological challenges in creating complex interventions in classroom settings. The journal of the learning sciences. 1992;2(2):141–178. doi: 10.1207/s15327809jls0202_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bui V, Woolcott G, Peddell L, Yeigh T, Lynch D, Ellis D, Samojlowicz D. An online support system for teachers of mathematics in regional, rural and remote Australia. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education. 2020;30(3):69. doi: 10.47381/aijre.v30i3.287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, Fan X, Du J. Gender and attitudes toward technology use: A meta-analysis. Computers & Education. 2017;105:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2016.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2019). About CAPTA: A legislative history. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau

- Christian CW. Professional education in child abuse and neglect. Pediatrics. 2008;122(Supplement 1):S13–S17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0715f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chyung, S. Y. Y. (2007). Age and gender differences in online behavior, self-efficacy, and academic performance.Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 8(3)

- Cózar-Gutiérrez, R., Sáez-López, J. M. Game-based learning and gamification in initial teacher training in the social sciences: an experiment with MinecraftEdu. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 13(1), 2., Darling-Hammond, L., & McLaughlin, M. W. (2016). (2011). Policies that support professional development in an era of reform. Phi delta kappan, 92(6), 81–92

- Dahlberg, L. L., & Mercy, J. A. (2009).The history of violence as a public health issue [DOI] [PubMed]

- Davies SC, Tedesco MF. Efficacy of an Online Concussion Training Program for School Professionals. Contemporary School Psychology. 2018;22(4):479–487. doi: 10.1007/s40688-018-00213-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Design-Based Research Collective (2003). Design-based research: An emerging paradigm for educational inquiry.Educational Researcher,5–8

- Duncan-Howell J. Teachers making connections: Online communities as a source of professional learning. British journal of educational technology. 2010;41(2):324–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.00953.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. Guilford press

- Ensink, K., Borelli, J. L., Normandin, L., Target, M., & Fonagy, P. (2019). Childhood sexual abuse and attachment insecurity: Associations with child psychological difficulties. The American journal of orthopsychiatry [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ertmer PA, Ottenbreit-Leftwich AT, Sadik O, Sendurur E, Sendurur P. Teacher beliefs and technology integration practices: A critical relationship. Computers & education. 2012;59(2):423–435. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fix RL, Busso DS, Mendelson T, Letourneau EJ. Changing the paradigm: Using strategic communications to promote recognition of child sexual abuse as a preventable public health problem. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2021;117:105061. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyd, J. J., Putnam, F. W., Lyon, T. D., Becker-Blease, K. A., Cheit, R. E., Siegel, N. B., & Pezdek, K. (2005). The science of child sexual abuse. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Garbacz LL, Zynchinski KE, Feuer RM, Carter JS, Budd KS. Effects of teacher-child interaction training (TCIT) on teacher ratings of behavior change. Psychology in the Schools. 2014;51(8):850–865. doi: 10.1002/pits.21788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual review of psychology. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guastaferro K, Zadzora KM, Reader JM, Shanley J, Noll JG. A Parent-focused Child Sexual Abuse Prevention Program: Development, Acceptability, and Feasibility. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2019;28(7):1862–1877. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01410-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gushwa M, Bernier J, Robinson D. Advancing child sexual abuse prevention in schools: An exploration of the effectiveness of the Enough! online training program for K-12 teachers. Journal of child sexual abuse. 2019;28(2):144–159. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2018.1477000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins SR, Clinton-Sherrod AM, Irvin N, Hart L, Russell SJ. Logic models as a tool for sexual violence prevention program development. Health promotion practice. 2009;10(1_suppl):29S–37S. doi: 10.1177/1524839908318803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrington A, Herrington J, Kervin L, Ferry B. The design of an online community of practice for beginning teachers. Contemporary issues in technology and teacher education. 2006;6(1):120–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN. Longitudinal effects of teacher and student perspectives of teacher-student relationship qualities on academic adjustment. Elementary School Journal. 2013;112:38–60. doi: 10.1086/660686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, E., Dale, M., Donnelly, P. J., Stone, C., Kelly, S., Godley, A., & D’Mello, S. K. (2020, April). Toward automated feedback on teacher discourse to enhance teacher learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–13)

- Jung I. Cost-effectiveness of online teacher training. Open Learning: The Journal of Open Distance and e-Learning. 2005;20(2):131–146. doi: 10.1080/02680510500094140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi E, Hubbard A. New directions for the design and study of professional development: Attending to the coevolution of teachers’ participation across contexts. Journal of teacher education. 2008;59(5):428–441. doi: 10.1177/0022487108324330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ke, F., Pachman, M., & Dai, Z. (2020). Investigating educational affordances of virtual reality for simulation-based teaching training with graduate teaching assistants.Journal of Computing in Higher Education,1–21

- Ke, Z., Yin, H., & Huang, S. (2019). (). Teacher participation in school-based professional development in China: does it matter for teacher efficacy and teaching strategies?.Teachers and Teaching,1–16

- Kelly N, Antonio A. Teacher peer support in social network sites. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2016;56:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny MC. Child abuse reporting: Teachers’ perceived deterrents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25:81–92. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny MC. Teachers’ attitudes toward and knowledge of child maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2004;28:1311–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, M. C., Lopez-Griman, A. M., & Donohue, B. (2017). Development and initial evaluation of a cost-effective, internet-based program to assist professionals in reporting suspected child maltreatment. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 10(4), 385–393.

- Kim, S., Nickerson, A., Livingston, J. A., Dudley, M., Manges, M., Tulledge, J., & Allen, K. (2019). Teacher Outcomes from the Second Step Child Protection Unit: Moderating Roles of Prior Preparedness, and Treatment Acceptability. Journal of child sexual abuse, 1–19 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kim, S., Nickerson, A. B., Livingston, J., Dudley, M., Manges, M., & Tulledge, J., &AllenK. Teacher outcomes from Second Step Child Protection Unit: Moderating roles of preparedness and treatment acceptability.Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 28,726–744 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kirtman L. Online versus in-class courses: An examination of differences in learning outcomes. Issues in teacher education. 2009;18(2):103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kissau S. Type of instructional delivery and second language teacher candidate performance: online versus face-to-face. Computer Assisted Language Learning. 2015;28(6):513–531. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2014.881389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleemeir C, Webb C, Hazzard A, Pohl J. Child sexual abuse prevention: Evaluation of a teacher training model. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1988;12:555–561. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(88)90072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications

- Lachowicz MJ, Sterba SK, Preacher KJ. Investigating multilevel mediation with fully or partially nested data. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 2015;18(3):274–289. doi: 10.1177/1368430214550343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CJ, Kim C. A technological pedagogical content knowledge based instructional design model: a third version implementation study in a technology integration course. Educational Technology Research and Development. 2017;65(6):1627–1654. doi: 10.1007/s11423-017-9544-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Jung J, Shin S, Otternbreit-Leftwich A, Glazewski K. A Sociological View on Designing a Sustainable Online Community for K–12 Teachers: A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2020;12(22):9742. doi: 10.3390/su12229742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Letourneau, E. J., & Shields, R. T. (2017). Ending child sexual abuse: A look at prevention efforts in the United States

- Levenson, J. S., & Letourneau, E. J. (2011). Preventing Sexual Abuse: Community Protection Policies and Practice. APSAC Handbook of Child Maltreatment

- Levi, B. H., Mundy, M., Palm, C., Verdiglione, N., Fiene, R., & Mincemoyer, C. (2021). An interactive online learning program on child abuse and its reporting.The journal of educators online, 18(2) [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Little, R. J., & Rubin, D. B. (2019). Statistical analysis with missing data (793 vol.). John Wiley & Sons

- Macià M, García I. Informal online communities and networks as a source of teacher professional development: A review. Teaching and teacher education. 2016;55:291–307. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.01.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre D, Carr A. Evaluation of the effectiveness of the stay safe primary prevention programme for child sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23(12):1307–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez-Flores MM, Marquez-Hernandez VV, Granados-Gamez G. Teacher’s knowledge and beliefs about child sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse; Research Treatment and Program Innovations for Victims Survivors & Offenders. 2016;25:538–555. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2016.1189474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Hau KT, Wen Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural equation modeling. 2004;11(3):320–341. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews B, Kenny MC. Mandatory reporting legislation in the United States, Canada, and Australia: A cross-jurisdictional review of key features, differences, and issues. Child maltreatment. 2008;13(1):50–63. doi: 10.1177/1077559507310613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercy JA. Having new eyes: Viewing child sexual abuse as a public health problem. Sexual Abuse. 1999;11(4):317–321. doi: 10.1177/107906329901100407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills B, Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Bernstein IH. The dimensionality and measurement properties of alcohol outcome expectancies across Hispanic national groups. Addictive behaviors. 2012;37(3):327–330. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTavish JR, Sverdlichenko I, MacMillan HL, Wekerle C. Child sexual abuse, disclosure and PTSD: a systematic and critical review. Child abuse & neglect. 2019;92:196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2018). Mplus User’s Guide (8th ed.) Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén

- Nickerson AB, Heath MA, Graves LA, Tulledge A, Manges T, Kesselring M, Parks S. School-based interventions for children impacted by sexual abuse. In: Paludi M, DenMark FL, editors. Victims of sexual assault and abuse: Resources and responses for individuals and families, Vol. 2: Cultural, community, educational and advocacy responses. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. Nickerson; 2010. pp. 77–99. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson, A. B., Tulledge, J., Manges, M., Kesselring, S., Parks, T., Livingston, J. A., & Dudley, M. (2019). Randomized controlled trial of the Child Protection Unit: Grade and gender as moderators of CSA prevention concepts in elementary students. Child Abuse and Neglect, 96, 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104101 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Preacher KJ, Zhang Z, Zyphur MJ. Alternative methods for assessing mediation in multilevel data: The advantages of multilevel SEM. Structural Equation Modeling. 2011;18:161–182. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2011.557329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Price L. Gender differences and similarities in online courses: challenging stereotypical views of women. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. 2006;22(5):349–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2729.2006.00181.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves TC. Design research from a technology perspective. Educational design research. 2006;1(3):52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Renk K, Liljequist L, Steinberg A, Bosco G, Phares V. Prevention of child sexual abuse: Are we doing enough? Trauma Violence & Abuse. 2002;3(1):68–84. doi: 10.1177/15248380020031004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rheingold AA, Zajac K, Chapman JE, Patton M, de Arellano M, Saunders B, Kilpatrick D. Child sexual abuse prevention training for childcare professionals: An independent multi-site randomized controlled trial of stewards of children. Prevention Science. 2015;16(3):374–385. doi: 10.1007/s11121-014-0499-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rienties B, Brouwer N, Lygo-Baker S. The effects of online professional development on higher education teachers’ beliefs and intentions towards learning facilitation and technology. Teaching and teacher education. 2013;29:122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2012.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaha, S. H., & Ellsworth, H. (2013). Predictors of success for professional development: Linking student achievement to school and educator successes through on-demand, online professional learning.Journal of Instructional Psychology, 40

- Shelton C, Archambault L. Discovering how teachers build virtual relationships and develop as professionals through online teacherpreneurship. Journal of Interactive Learning Research. 2018;29(4):579–602. [Google Scholar]

- Starling SP, Heisler KW, Paulson JF, Youmans E. Child abuse training and knowledge: a national survey of emergency medicine, family medicine, and pediatric residents and program directors. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e595–e602. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stes A, Min-Leliveld M, Gijbels D, Van Petegem P. The impact of instructional development in higher education: The state-of-the-art of the research. Educational research review. 2010;5(1):25–49. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2009.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stes A, De Maeyer S, Gijbels D, Van Petegem P. Instructional development for teachers in higher education: effects on students’ learning outcomes. Teaching in Higher Education. 2012;17(3):295–308. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2011.611872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN) (2015, September 25). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly. Retrieved 10 June 2020, from http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E

- United Nations (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. General Assembley 70 session

- Vanderlinde R, van Braak J. The e-capacity of primary schools: Development of a conceptual model and scale construction from a school improvement perspective. Computers & education. 2010;55(2):541–553. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2010.02.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K, Bridgstock R, Farrell A, Rassafiani M, Schweitzer R. Case, teacher and school characteristics influencing teachers’ detection and reporting of child physical abuse and neglect: Results from an Australian survey. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2008;32:983–993. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, K., Rassafiani, M., Mathews, B., Farrell, A., & Butler, D. (2010). Teachers’ attitudes [DOI] [PubMed]

- toward reporting child sexual abuse: Problems with existing research leading to new scale development.Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 19(3),310–336. doi:10.1080/10538711003781392 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Walters GD, Espelage DL. Mediating the bullying victimization–delinquency relationship with anger and cognitive impulsivity: A test of general strain and criminal lifestyle theories. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2017;53:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2017.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SK, Hsu HY, Reeves TC, Coster DC. Professional development to enhance teachers’ practices in using information and communication technologies (ICTs) as cognitive tools: Lessons learned from a design-based research study. Computers & Education. 2014;79:101–115. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2014.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webster SW, O’Toole RO, O’Toole AW, Lucal B. Overreporting and underreporting of child abuse: Teachers’ use of professional discretion. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2005;29:1281–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtele, S. K., Hughes, J. W., & Owens, J. S. (1998). An examination of the reliability of the “What If” Situations Test: A brief report. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 7, 41–52. https://doi.org.10.1300/j070v07n01_03

- Wurtele, S. K., Kast, L. C., & Kondrick, P. A. (1988, August). Development of an instrument to evaluate sexual abuse prevention programs. Paper presented at the convention of the American Psychological Association, Atlanta, GA

- Wurtele SK. Preventing sexual abuse of children in the twenty-first century: Preparing for challenges and opportunities. Journal of child sexual abuse. 2009;18(1):1–18. doi: 10.1080/10538710802584650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]