Abstract

Research on trauma- and stressor-related disorders has recently expanded to consider moral injury, or the harmful psychological impact of profound moral transgressions, betrayals, and acts of perpetration. Largely studied among military populations, this construct has rarely been empirically extended to children and adolescents despite its relevance in the early years, as well as youths’ potentially heightened susceptibility to moral injury due to ongoing moral development and limited social resources relative to adults. Application of the construct to young persons, however, requires theoretical reconceptualization from a developmental perspective. The present paper brings together theory and research on developmentally-oriented constructs involving morally injurious events, including attachment trauma, betrayal trauma, and perpetration-induced traumatic stress, and describes how they may be integrated and extended to inform a developmentally-informed model of moral injury. Features of such a model include identification of potentially morally injurious events, maladaptive developmental meaning-making processes that underlie moral injury, as well as behavioral and emotional indicators of moral injury among youth. Thus, this review summarizes the currently available developmental literatures, identifies the major implications of each to a developmentally-informed construct of moral injury, and presents a conceptual developmental model of moral injury for children and adolescents to guide future empirical research.

Keywords: Moral injury, Attachment trauma, Betrayal trauma, Perpetration-induced traumatic stress, Development

To Trust is to Survive: Toward a Developmental Model of Moral Injury

The concept of moral injury (MI) has inspired and informed a growing body of research on trauma- and stressor-related disorders that follow from events that violate moral beliefs and expectations (Litz et al., 2009; Wisco et al., 2017; see Litz & Kerig, 2019 and Griffin et al., 2019 for recent reviews). Although historically focused on combat traumas that involve an element of life threat, violence, or danger to physical integrity, emerging evidence suggests that nonviolent events characterized by a perceived violation of moral beliefs or expectations also may have detrimental consequences (Jordan et al., 2017; Maguen et al., 2011). These potentially morally injurious experiences (PMIEs) share several common elements: PMIEs are deemed as actions or inactions committed either by the self (i.e., perpetration or omission) or others (i.e., transgression or betrayal) that occur in high stakes situations in which a moral value, belief, or expectation is violated through experiencing, witnessing, or learning about the event (Drescher et al., 2011; Farnsworth et al., 2017; Litz et al., 2009; Shay, 2014).

Shay (1991) originally posited that such PMIEs characterized by a “betrayal of ‘what’s right’” have the ability to shatter one’s foundational moral and philosophical assumptions about oneself, others, and the world. Thus, MI is conceptualized to follow exposure to PMIEs only when cognitive dissonance emerges between the event and one’s moral expectations (Litz et al., 2009) and attempts to resolve the resulting moral pain prompt unhelpful cognitive strategies for making sense of such a contradiction (e.g., negative attributions, rumination; Elwood et al., 2009; Farnsworth et al., 2014; Litz et al., 2009) and overwhelming negative, condemning moral emotions, including primary self-condemning emotions of guilt and shame, followed by secondary self- and other-condemning emotions of anger, disgust, and contempt (Bravo et al., 2020; Farnsworth et al., 2014; Litz et al., 2009; Shay, 2014). Although the psychological consequences of PMIEs have been noted to largely mimic PTSD symptoms of intrusions, avoidance, and negative alterations in cognition and mood, PMIE exposure has been associated with collateral manifestations of a range of self-injurious or self-handicapping behaviors (e.g., self-harm, substance use, risk-taking; Currier et al., 2014), hostility and aggression (Dennis et al., 2017), and suicide risk (Ames et al., 2019; Bryan et al., 2018; Nichter et al., 2021) above and beyond exposure to physical threat (see McEwen et al., 2020 for a recent meta-analysis). Empirical investigations tentatively support MI and PTSD as distinct constructs characterized by unique self-reported symptom markers (Bryan et al., 2018; Currier et al., 2019) and patterns of brain activation during and after danger- and nondanger-based events (Barnes et al., 2019; Ramage et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2019). MI has also been associated with specific effects related to spiritual or existential struggles (e.g., Brémault-Phillips et al., 2019; Currier et al., 2019; Drescher & Foy, 2008; Hodgson & Carey, 2017).

Despite the many proposed theoretical differences posited between the concepts of PTSD and MI, experts have noted limitations to our current empirical knowledge of the MI phenomenon and urged caution against assuming that MI is a syndrome in its own right without additional investigation (Litz & Kerig, 2019; Williamson et al., 2018). One such important limitation in MI research to date is the disproportionate application of MI to military members and veterans (Litz & Kerig, 2019). This focus is understandable given the high rates of PMIE exposure in military service (Wisco et al., 2017), which has even led some to propose that PMIEs solely impact military populations (Drescher et al., 2011). However, in a recent meta-analysis, Williamson et al. (2018) found that both military and non-military occupational PMIE exposure was associated with a host of negative mental health outcomes, particularly PTSD. Accordingly, strong evidence has emerged that harmful PMIEs may occur outside of the context of deployment (Lentz et al., 2021; McEwen et al., 2020; Steinmetz et al., 2019; Williamson et al., 2018). However, the vast majority of these studies have focused on adults, despite the potential relevance of the MI construct to youth. Given that the meaning individuals make of adverse experiences is shaped by their history and context (Jordan et al., 2017), it is unfortunate that missing from the literature to date has been attention to the developmental context of MI and consideration of how developmental processes may affect how youth make meaning of profound moral transgressions, betrayals, and acts of perpetration.

Theoretical Extensions of the MI Concept to Youth

To date, only two theoretical articles have attempted to conceptualize MI from a developmental viewpoint. Nash and Litz (2013) made an initial attempt to apply a developmental and family systems perspective to MI among military parents and their children by considering how PMIEs may interact with moral development. In this work, Nash and Litz (2013) assert that normative moral development progresses as moral values and expectations are assimilated and accommodated through minor alterations in beliefs following lived experiences. From this perspective, MI is proposed as an inherently developmental construct in that MI emerges when an event (i.e., PMIE) overwhelms one’s ability to assimilate or accommodate new information into existing moral schemas given one’s current stage of development and available familial, social, and spiritual resources. Given the limited internal and external resources children have at their disposal, due their earlier stage of development and fewer sources of social support, Nash and Litz (2013) also suggest that a wider range of transgressive events may serve as PMIEs among military children as compared to adults, including those that are real (e.g., a child’s expressions of anger toward a parent absent due to deployment) or imagined (e.g., self-blame for a parent’s death in combat).

This theoretical proposition provides a useful starting point for conceptualizing the impact of PMIEs among youth; however, there are limitations that hinder its ability to offer a comprehensive, developmentally-informed construct of MI. First, this model does not consider the ways in which PMIEs may be developmentally salient to youth outside of the military family context. Further, analogous to the emerging construct of MI among adults, Nash and Litz (2013) did not draw upon related, developmentally-oriented literatures regarding posttraumatic stress that may inform an understanding of the clinical and developmental implications of MI among youth.

Haight et al. (2016) acknowledged these limitations in a preliminary scoping review of the MI construct as it relates to social work practice. These authors extended the application of MI to child welfare practitioners and their clients, who are regularly exposed to an array of events that violate moral beliefs and expectations (e.g., child maltreatment) and thus meet criteria to be defined as PMIEs (Haight et al., 2016). Haight et al. (2016) also acknowledge the importance of applying existing, related constructs in the posttraumatic stress literature to a developmental construct of MI; however, the authors were unable to pursue an in-depth review of this research in their manuscript. Instead, Haight et al. (2016) concluded by identifying two important limitations in the literature to date: 1) few scholars have considered a theoretical application of developmentally-oriented trauma literatures to the extension of MI to children and adolescents, despite underlying similarities; and 2), at the time of their publication, there were no empirical studies examining differences among children, adolescents, and adults’ interpretations of and responses to PMIEs.

Although these limitations largely still pertain, Chaplo et al. (2019) recently constructed a developmentally-appropriate measure of perceived exposure to morally injurious events for children, adolescents, and emerging adults. In a validation study with a sample of emerging adults, results revealed a 5-factor structure of PMIEs comprised of commission with agency, commission under duress, omission, witnessing, and betrayal. This work makes a first attempt at incorporating a developmental perspective to the empirical study of MI and offers evidence that, although PMIEs may exhibit similar qualities across developmental stages, there may be youth-specific characteristics of PMIEs (e.g., distinct forms of commission) that suggest the need for models that examine the developmental processes that may underlie these differences and influence how PMIEs are experienced by youth.

Moral Development and Moral Transgressions Among Youth

To understand the heightened salience of moral transgressions among children and adolescents, it is important to consider how these events may function as disruptions or alterations to ongoing, normative moral development. Despite longstanding debate on the trajectory and age-specific stages of normative moral identity development (Wainryb & Pasupathi, 2015), such development has historically been theorized to begin in childhood and accelerate during adolescence (e.g., Kohlberg, 1969; Malti & Ongley, 2014; Piaget, 1965). Studies aiming to examine the development of early conscience, or the inner self-regulatory mechanism governing moral emotion and conduct, suggest that this framework begins developing during the first years of life and is substantially influenced by the quality of attachment relationships and family socialization (Kochanska & Aksan, 2006; Kochanska et al., 2005, 2010). In particular, caregiver-child relationships characterized by shared positive affect and responsiveness directly predict moral emotions (e.g., guilt) and indirectly predict moral conduct through fostering eager, self-sustained compliance with the caregiver’s rules (Kochanska et al., 2005). Accordingly, the foundations of the moral self, or a child’s inner guide for moral character and behavior, are molded by the valance of the parent–child relationship and, in turn, drive internal motivation to follow or adopt parental rules as well as the experience of moral emotions following transgressions (Kochanska et al., 2010; Thompson, 2012). Children subsequently begin to understand basic elements of the “social contract,” or the implicit code of conduct that guides expectations of justice and fairness in social behavior, including the responsibilities of socialization agents to provide protection to those under their care (Rawls, 1971). Children also evince the capacity to identify actions as harmful and perceive harmful actions as “wrong” within increasingly broadening contexts during early childhood (Thompson, 2012; Wainryb, 2006).

The ability to make nuanced, context-specific judgments increases during the transition to adolescence as capacities for moral reasoning develop and concurrent strides are made in development across domains, including the biological (e.g., maturation of the prefrontal cortex), cognitive (e.g., increased capacity for abstract thinking, perspective-taking, introspection), emotional (e.g., improved emotion regulation), and social (e.g., greater recognition of human error or negligence and higher value of the social contract; Garrigan et al., 2018; McNeely & Blanchard, 2009; Oosterhoff et al., 2018; Saltzman et al., 2018; Wainryb, 2006). In addition, research examining children’s and adolescents’ narratives of harming or helping others has found that, across development, adolescents have increasingly sophisticated capacities to connect these experiences to their own identity and sense of self (Köber et al., 2015; Recchia et al., 2015; Wainryb et al., 2005). Thus, adolescence is a critical period for rapidly developing social and moral expectations about the self, others, and the world (e.g., Hardy & Carlo, 2011; Wainryb, 2011).

A defining task of normative moral development is the construction of moral agency, or the perception of oneself and others as independent moral agents responsible for actions consistent or inconsistent with beliefs, goals, and values (Black, 2016; Pasupathi & Wainryb, 2010; Wainryb et al., 2005). Moral agency, as it develops, allows youth to make sense of experiences of helping or wrongdoing as influenced by the thoughts, feelings, and desires of individuals implicated in the event (Bandura, 2006; Wainryb, 2011). Notably, experiencing and engaging in both prosocial and transgressive behaviors are hypothesized to facilitate the construction of moral agency; minor moral transgressions among children and adolescents (e.g., pushing or shoving others, ostracizing peers, spreading rumors, betraying a secret) offer an opportunity to grapple with the reasons underlying these behaviors, to reflect on their harmful consequences, and ultimately to construct an adaptive sense of the self as a moral agent who engages in disagreements, conflict, and harm but can repair these actions to establish oneself as imperfect but fundamentally moral (Midgette, 2018; Pasupathi & Wainryb, 2010; Wainryb, 2011). This adaptive form of moral agency is conceptualized to arise following a normative trajectory of moral development (Nucci, 2014; Pasupathi & Wainryb, 2010); however, profound violations of the social contract have the potential to produce clinically significant levels of distress (e.g., Layne et al., 2017) and disrupt or distort moral agency as youth struggle to make meaning of severe moral transgressions, particularly their own acts of perpetration, within the context of the cognitive, social, and emotional resources they have developed at the time of the transgression (Wainryb, 2011; Wainryb & Pasupathi, 2010).

The distortion of moral agency in the face of PMIEs is not a phenomenon that applies solely to youth; moral agency may be challenged and potentially distorted following events that occur across the lifespan. However, adults have more sophisticated cognitive, emotional, and social resources available to them to make meaning of ongoing events, making it decreasingly likely for them to experience major distortions of moral agency later in life (Wainryb, 2011). In addition, it is theorized that a wider array of events may have the possibility to interfere with the construction of moral agency among youth than adults, given that adults have a more extensive history of experiences involving both themselves and others as moral agents which offers them a wider prior context to draw upon when grappling with adverse circumstances (Wainryb, 2011).

These theoretical propositions suggest that the construction of a developmental model of MI will be aided by a review of the existing theory and empirical research on developmentally-oriented adversities that have implications for moral development. Within the literature on traumatic stress, several developmentally-salient constructs that feature a form of moral violation or transgression within a trusted interpersonal relationship are particularly relevant. The first highlights the lasting, harmful impact of such interpersonal violations within one of the most foundational relationships in a child or adolescent’s life: the caregiver-child relationship.

Attachment Trauma

The term attachment trauma (AT) refers to the traumatic impact on a child of events that threaten the strength, security, or availability of the attachment relationship with a caregiver, regardless of whether a direct life threat is involved (Bowlby, 1973/1998). Attachment figures serve as children’s first model of how to process information, regulate emotions, and behave skillfully, ultimately shaping the construction of representative beliefs (i.e., internal working models) of what to expect from others and the world (van der Kolk, 2005; Weinfield et al., 2008). Internal working models act as implicit systems through which children learn and process socioemotional information in ways that help children make meaning of interpersonal relationships (Maltby & Hall, 2012). When attachment security is undermined by absent, inconsistent, rejecting, intrusive, hostile, or violent caregiving, children may develop maladaptive internal working models of the self (e.g., as unworthy), the caregiver (e.g., as unloving), and the world (e.g., as unpredictable; Bowlby, 1973/1998; Sherman et al., 2015; Weinfield et al., 2008). Such disruptions to primary attachments interfere with a child’s ability to regulate internal (e.g., emotions, cognitions) and external (e.g., behavior) states, resulting in a wide array of internalizing and externalizing psychopathologies (Cook et al., 2005; Spinazzola et al., 2005; van der Kolk, 2005).

Attachment figures have a unique capacity to mold a child’s internal working model given that they serve as primary sources of basic, fundamental needs, including nurturance, protection and, ultimately, survival (e.g., Breidenstine et al., 2011; Doyle & Cicchetti, 2017). Thus, whether facing the threat of true danger, stress, or simply unanticipated novelty, children have an innate predisposition to seek out attachment figures in order to resolve perceived threats and restore a sense of safety in the environment (Charuvastra & Cloitre, 2008). When a caregiver’s responses to a child’s requests for assurance are erratic, unresponsive, harsh, or misattuned to developmental advances (e.g., a caregiver who becomes increasingly harsh as a toddler begins to assert independence), the internal working model may accommodate a belief that reliance on social relationships is unpredictable or threatening (Sherman et al., 2015) and children may withdraw and become isolative (Charuvastra & Cloitre, 2008).

As such, an emerging body of research suggests that within the context of caregiving relationships, both Criterion A events that involve an immediate threat of danger (e.g., physical or sexual maltreatment) and non-Criterion A events (e.g., extended separation from a caregiver, loss of a caregiver, perceived emotional abandonment by a caregiver when in need of comfort) may be perceived as overwhelming, dysregulating, and traumatic to youth (Kobak et al., 2004; Spinazzola et al., 2021). Both sets of events are defined by a perceived threat to the availability or trustworthiness of an attachment figure, which may be experienced as a threat to psychological survival through the eyes of children due to their ultimate reliance on that attachment figure for resources and support (Kerig, 2017; Kobak et al., 2004; van der Kolk, 2005). Given the salience of parent–child relationship quality on moral development (i.e., moral emotions and behavior), AT may also have moral implications as well; research suggests that youth exposed to ATs involving Criterion A events (e.g., physical abuse) as well as those that do not fit Criterion A (e.g., neglect) subsequently exhibit maladaptive alterations in moral development and behavior (Koenig et al., 2004). In fact, Bowlby (1944) himself originally posited that AT was a prime driver of antisocial behavior and juvenile delinquency.

ATs involving caregivers are unlikely to be experienced only once or in isolation of each other (Courtois, 2008). Children who experience a number of these events are considered to have experienced “complex trauma” which is associated with long-term psychological, spiritual, and interpersonal consequences (Cook et al., 2005; National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2018; Pressley & Spinazzola, 2015). Evidence suggests that complex trauma exposure disrupts and strains spiritual and religious beliefs, which may result in existential conflict, shame, and difficulty trusting a benevolent God or religious community above and beyond the effects of acute traumas characterized by life threat (Pressley & Spinazzola, 2015). Additionally, the constellation of psychological impairments following complex trauma has been proposed to extend beyond traditional PTSD symptoms and to have pervasive effects on ongoing development. In this regard, scholars proposed a new diagnosis of Developmental Trauma Disorder (DTD) that clustered these diverse symptoms into patterns of dysregulation in the domains of self and interpersonal, emotional, cognitive, and physiological development (D’Andrea et al., 2012; van der Kolk, 2005). The proposed DTD syndrome may provide a useful framework for examining the psychological and interpersonal impact of moral violations by attachment figures. For example, recent studies of children and adolescents have found that exposure to AT was associated with DTD symptom severity even after controlling for the effect of PTSD symptoms (Spinazzola et al., 2018) and that AT is uniquely associated with DTD beyond other types of trauma exposure (Spinazzola et al., 2021; van der Kolk et al., 2019).

The study of AT promises to contribute to a developmental model of MI by offering a construct dedicated to the developmentally-salient impact of events uniquely experienced by youth. Several aspects of the AT literature may be particularly informative. First, from a child’s-eye point of view (Kerig, 2017), transgressions or betrayals by caregivers that threaten the security of the attachment relationship but are not literally life threatening, as is required by Criterion A for the diagnosis of PTSD, may be perceived as “high stakes” and therefore qualify as PMIEs. Events that threaten a relationship upon which the child physically and emotionally depends thus may constitute an indirect, high-stakes threat as well as a moral betrayal or a transgression; accordingly, ATs may serve as a form of previously unrecognized PMIEs. Second, the theorized negative alterations to a child’s internal working model of the self, caregivers, and the world following ATs are reminiscent of Shay’s (1991) conceptualization that MI involves disruptions to the fundamental moral belief that are core to one’s understanding of the self, others, or the world. Children and adolescents develop an internal working model in an attempt to accurately represent and predict sources of interpersonal harm and safety in their social environment; consequently, when caregivers who are expected to serve as a source of safety actually perpetuate harm, the internal working model may be distorted such that youth perpetually expect harm, exploitation, or rejection from others (Weinfield et al., 2008) which may promote reactions of withdrawal and lasting mistrust. Such a framework may also be projected onto religious deities and figures, from whom children and adolescents may expect unconditional protection (Pressley & Spinazzola, 2015). Notably, internal working models become increasingly consolidated and less open to change over time (Sherman et al., 2015); as such, distortions to the internal working model in the context of attachment relationships reflect a developmental process that is particularly salient during childhood and integral to a developmental model of MI.

Finally, the proposed DTD diagnosis criteria may inform an understanding of the psychological ramifications of PMIEs among youth, given the many overlapping themes between the proposed DTD criteria and theorized phenomena of MI (Jinkerson, 2016; van der Kolk, 2005). In particular, DTD criteria require experiencing AT as well as a Criterion A-related traumatic events, followed by a number of forms of developmental dysregulation (e.g., cognitive, relational, self-attributional, behavioral, affective) and persistently altered attributions or expectancies (e.g., negative self-attribution, distrust of caregiver, loss of expectancy of protection, loss of trust in social agencies, lack of recourse to justice, and perceived inevitability of future victimization; D’Andrea et al., 2012; van der Kolk, 2005). Given the overlap of these AT features with MI, this proposed construct offers potential insight into how MI may present among children and adolescents within the context of attachment relationships.

Of note, although the AT literature has much to offer a developmentally-oriented conceptualization of MI, there are important elements of the MI construct that remain unaddressed by AT theory. First, AT only takes into consideration the complex, deleterious impact of betrayals or transgressions by caregivers or events that threaten the availability of caregivers. MI posits that PMIEs can occur in high stakes situations that involve any figure to whom one turns for trust, guidance, or protection (Farnsworth et al., 2017; Shay, 2014). Further, ATs do not take into consideration the potential lasting psychological consequences of one’s own transgressions or acts of perpetration, a defining feature of MI that distinguishes the phenomenon from the Criterion A definition of trauma. Thus, additional research that examines these remaining features of MI from a developmental perspective must be considered in order to fully conceptualize a developmentally-informed model of MI.

Betrayal Trauma Theory

The construct of betrayal trauma (BT; Freyd, 1994, 1996) provides a second stepping stone toward considering the morally injurious impact of a broader range of interpersonal experiences among youth. BT theory posits that profound forms of interpersonal betrayal, in isolation from or in addition to the presence of physical threat, have the potential to result in posttraumatic stress reactions (Freyd, 2013; Kelley et al., 2012). Although both AT and BT propose that betrayals that occur within the context of attachment relationships have the most impairing long-term consequences due to the primacy of caregiver relationships (Bernstein & Freyd, 2014), BT has also been extended beyond the context of attachment relationships to discuss the deeply impairing consequences following from acts that violate an expectation of trust, including social betrayals by trusted others (Platt et al., 2009), institutions (Monteith et al., 2016; Smith & Freyd, 2013, 2014), and social systems upon whom individuals depend for support or resources (Smith & Freyd, 2017). Thus, BT is set apart from the broader literature on posttraumatic stress by its central focus on the nature of the relationship between the victim and a trusted perpetrator (Birrell & Freyd, 2006; Freyd, 2013) and, similar to MI, the ensuing cognitive dissonance surrounding what “should be” or “should happen” in trusted relationships in the wake of social violations (Freyd et al., 2005).

Also consistent with MI, the psychological distress that follows from betrayal-based traumas may vary depending on the degree to which an event is perceived as a social betrayal, or the mismatch between the expectations one has for the necessary systems of social dependence implicated in the event and the event itself (Freyd, 1994). This cognitive dissonance often prompts meaning-making strategies that shift the focus from the perpetrator onto the self, including distorted cognitive appraisals of self-blaming, perceiving the self as damaged, bad, or wrong (i.e., shame-based appraisals), and alienation from others (Gagnon et al., 2017). Freyd argues that such reframing of events serves the short-term function of allowing youth to maintain relationships with the abuser when all other adaptive evolutionary responses (e.g., confronting the betrayer, exiting the situation) potentially threaten the reliability of support, resources, or protection for which they simultaneously depend on the perpetrator (Barlow & Freyd, 2009; Freyd, 1994, 1996; Gagnon et al., 2017). In the case of BT, the perpetrator is someone the youth “cannot afford not to trust;” in other words, to trust is to survive (Freyd, 1996, p. 11). Taken together, these self-deprecating strategies may be conceptualized as betrayal-blindness appraisals, or tools used to help victims remain psychologically distanced from the betrayal in order to maintain a necessary relationship. Similar to MI, however, such betrayal-blindness appraisals become maladaptive over time (Gagnon et al., 2017). Consistent with this proposition, Kerig et al. (2012) reported that disengagement strategies, such as emotional numbing, accounted for the observed link between BT exposure and callous-unemotional traits in a sample of juvenile justice-involved youth. BT exposure has also been associated with heightened posttraumatic stress, dissociation, numbing, and depression symptoms, regardless of the presence of life threat during the event (Gagnon et al., 2017; Kelley et al., 2012; Platt & Freyd, 2015).

Given its noted similarities to MI, several findings from BT theory may be particularly relevant to a developmental model of MI. First, there may be important distinctions to make regarding the interpersonal contexts (i.e., types of relationships, institutions) in which youth experience betrayal consistent with PMIEs. Although much of the BT literature is devoted to examining BT within caregiver-child relationships following direct exposure to maltreatment (e.g., sexual abuse, physical abuse), there may be additional events that violate children’s fundamental trust in their caregiver’s protection, including a caregiver’s failure to protect youth from Criterion A events or other threats (when the youth perceives that the caregiver has awareness and agency to do so), or learning that a parent or caregiver has perpetrated a potentially traumatic event against someone else (e.g., sibling, friend, another caregiver, another trusted adult). Trusted adults outside of the caregiver-child bond also have the potential to develop relationships with youth characterized by social dependence, hierarchy, and the expectation of trust; the perpetrator need not be an attachment figure. Although such hierarchical relationships have been discussed more frequently in regard to young adults (e.g., Bernstein & Freyd, 2014), children and adolescents are inherently more dependent on others than are adults and are typically involved in many relationships with authority figures and socialization agents that are characterized by dependency and an expectation of trust. Given children’s limited coping resources and the inescapability of relationships from the adults who wield authority over them, children may be particularly vulnerable to reliance on betrayal-blindness appraisals to maintain these relationships as a result.

Youth are also typically involved with a large number of institutions such as schools (a studied source of institutional BT among undergraduates; Smith & Freyd, 2013), sports organizations, and after-school programs throughout their development, all of which are contexts in which institutional BT might take place; thus, teachers, coaches, non-caregiver family members, religious leaders, service professionals with authority (e.g., doctors, paramedics), and romantic dating partners may serve as relationships with the potential to involve the inherent expectation of trust for youth. Although limited research to date has examined the impact of institutional betrayal during childhood or adolescence, a recent study by Lind et al. (2020) found that perceived institutional betrayal related to sexual harassment during high school was uniquely associated with present posttraumatic stress symptoms among college students. In addition, the institutions in youths’ lives also have specific qualities that set them apart from those in which adults participate. For children, as Delker et al. (2018) argue, unsupportive familial responses to childhood abuse (e.g., failure to intervene, disbelief, blame, or punishment) may serve as a form of institutional betrayal, in that the family unit represents an institution youth trust to protect or support them. Institutional betrayal may also occur when adults do not support or believe youth who disclose abuse (e.g., if perpetrator is a respected member of the community; Delker et al., 2018), which may be particularly impactful given the inherent power differential between youth and adults. Together, these findings suggest interpersonal betrayals in relationships characterized by broad forms of social dependence may have harmful, lasting consequences among children and adolescents and warrant being considered as PMIEs.

Additionally, the central role of dissociation symptoms following profound social betrayal may also have important role in a developmental model of MI. Many studies have shown that children demonstrate heightened risk for developing dissociation following betrayal-based traumatic events (i.e., maltreatment; e.g., Macfie et al., 2001); further, adolescents who develop PTSD have been found to be substantially more likely to demonstrate symptoms of dissociation (e.g., depersonalization, derealization; Choi et al., 2019; Steuwe et al., 2012; Waelde et al., 2005; Wolf et al., 2012a, b) when compared to adults. Theoretical explanations to account for this notable age-related phenomenon suggest that dissociative experiences span a range from normative imaginative processes to disordered, pathological processes (Carlson et al., 2009) and that fractionation of experience may be a developmentally normative approach to making sense of conflicting, complicated experiences for youth (Ross et al., 2020). However, when cognitive dissonance overwhelms an adolescent’s emotional and cognitive regulation, youth may be particularly susceptible to engaging in pathological dissociation as a way to cope with traumatic distress (Carlson et al., 2009; Kerig & Bennett, 2013; Putnam, 1997).

Plattner et al. (2003) found preliminary evidence to support dissociation as a salient feature of BT, reporting significant correlations between pathological dissociation and intrafamilial, but not extrafamilial, trauma among juvenile justice-involved youth. Gobin and Freyd (2009) also found that, among young adults, a history of high BT was associated with higher levels of dissociation. Importantly, when considered as a feature of PTSD, dissociation symptoms as are conceptualized to reflect substantive disorder in the integration of the self (Macfie et al., 2001). Thus, within the context of a developmental model of MI, pathological dissociation may be a response to the challenge of integrating a profound sense of betrayal with a belief of trusted others as fundamentally moral beings, allowing dependent children and adolescents to maintain cognitive distance from ongoing betrayals and thus reducing short-term distress and dissonance.

These developmentally-salient aspects of BT theory offer insight that might assist in articulating a developmental model of MI. Thus far, this review has broadly considered how a violation of fundamental trust in the social contract within the context of attachment relationships and broader dynamics of social dependence may shape the types of events perceived as threats to survival in the form of AT and BT, respectively. However, this review has yet to consider a final form of PMIEs which, although very different from the former two, also has the capacity to constitute a violation of trust in the social contract and cause psychological harm, and that is the perpetration of moral transgressions.

Perpetration-Induced Traumatic Stress

Most research examining the harmful effects of stressful events has focused on those who are victims of the event; however, a small subset of literature on traumatic stress hypothesizes that those who perpetrate traumatic events may also be at risk for developing posttraumatic stress (MacNair, 2002). The study of perpetration-induced traumatic stress (PT) attempts to address the experience of individuals who are causal participants in a PTSD Criterion A traumatic event and subsequently develop impairing symptoms of PTSD (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013; MacNair, 2002). Although the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) has never explicitly excluded the concept of perpetration from its definition of what comprises a traumatic event, it also has never explicitly identified it as such; the most recent DSM-5 acknowledges perpetration as a potentially traumatic event only in the discussion section following the PTSD diagnosis criteria and specifies that it is relevant only “for military personnel” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Unsurprisingly, the construct of PT has been most expansively applied to military populations as a result (e.g., MacNair, 2002; Maguen et al., 2009, 2010). However, theorists have posited that PT may also apply to civilians who engage in violent acts, arguing that the historical lack of attention to perpetration as a source of traumatization may reflect reduced sympathy for those who commit violent acts or unwillingness to draw attention to the cultural, institutional, and contextual forces that lead individuals to become perpetrators (MacNair, 2015). Accordingly, research on PT among adults has only recently been extended to slaughterhouse workers (Dillard, 2009), veterinarians and animal shelter staff (Rohlf & Bennett, 2005; Whiting & Marion, 2011), police officers (Komarovskaya et al., 2011), voluntary and forced combatants (Hecker et al., 2013), and convicted adult offenders (Crisford et al., 2008; Papanastassiou et al., 2004).

Across the literature on PT among adult civilian and military populations, perpetration of aggressive and violent acts has been repeatedly associated with PTSD symptoms even after controlling for exposure to life threat and other traumatic events (Komarovskaya et al., 2011; Maguen et al., 2009; Papanastassiou et al., 2004; Rohlf & Bennett, 2005). These findings were qualified by Hecker et al. (2013), who highlighted that perpetration of violence among combatants in the DR Congo was only associated with PTSD among those forcibly recruited (as opposed to those who voluntarily joined). This result is consistent with analogous findings that PTSD symptom severity was predicted by offense-related guilt among physical and sexual assault offenders (Crisford et al., 2008). Together, these findings highlight an important theme of PT that is consistent with the construct of MI, which is that, to experience PT, the act of perpetration must be perceived as conflicting with one’s self-concept, moral code, or belief system, thereby producing the kind of cognitive dissonance that results in self-attributed emotions of guilt or shame (MacNair, 2015).

Although the PT literature base is relatively small and potentially subsumed by the more expansive phenomenological umbrella of MI among adults, it does include a subset of studies on the impact of perpetration among children and adolescents that can be extended and applied to a developmentally-informed model of MI. Several groups of youth have been documented as being at-risk for experiencing PT, including child soldiers (Betancourt et al., 2013; Derluyn et al., 2004) and gang-involved youth (Kerig et al., 2013). Child soldiers, who are often forcibly recruited into armed conflict (Vindevogel et al., 2011), may not only become victims of brutal initiations, physical or sexual abuse, and exposure to violence but are often compelled to perpetrate violent executions, torture, rape, kidnapping, and other atrocities (Betancourt et al., 2013; Derluyn et al., 2013; Klasen et al., 2015). A similar victim-perpetrator phenomenon exists among gang-involved youth, who may be at risk of experiencing brutal gang initiations, physical attacks by rival gangs, and sexual victimization, but also are compelled to perpetrate acts of violence and aggression toward others as part of gang activity (Kerig et al., 2013, 2016). Notably, both in studies of international child soldiers and gang-involved youth, a substantial portion report these acts of perpetration as their most traumatizing experience (Kerig et al., 2016; Wainryb, 2011). Consistent with the MI literature, acts of perpetration can be conceptualized as potentially traumatic events when they are perceived as a transgression or violation of a moral expectation or belief. In support of this theory, for example, child soldiers who view perpetration events positively and endorse greater appetitive aggression report significantly fewer PTSD symptoms following perpetration experiences than those who report a negative perception of their actions (Weierstall et al., 2012).

Beyond these specific at-risk populations, PT may also be relevant to youth more broadly following perpetration of transgressions in the context of normative interpersonal experiences, such as intimate partner aggression (Hickman et al., 2004) or bullying (Modecki et al., 2014). Although perpetration in these contexts is not necessarily physically violent or severe (Bossarte et al., 2008; Mozley et al., 2018; Sterzing et al., 2020), psychological or electronic perpetration can have comparably profound consequences to youth victims (e.g., suicide; Exner-Cortens et al., 2013; Litwiller & Brausch, 2013) and may be relevant to a developmental model of MI. In support of this conceptualization, preliminary research suggests that perpetration of intimate partner aggression among adolescents is associated with PTSD symptoms when youth ruminate on negative emotions and endorse perceived PT (Mozley et al., 2018), which is analogous to research on rumination following adult adverse experiences (e.g., Elwood et al., 2009). Despite limited available research examining bullying perpetration as a potentially traumatic event, studies have affirmed that bullying victimization may constitute a traumatic event (Idsoe et al., 2012; Mynard et al., 2000) and recent studies suggest that bullying perpetration may be correlated with posttraumatic stress, particularly when youth identify as both victims and perpetrators of bullying (i.e., bully-victims; Baldry et al., 2019; Idsoe et al., 2012; Sterzing et al., 2020).

Within the limited literature on PT among children and adolescents, the primary developmental process that has emerged as important to the psychological impact of perpetration among youth is the task of establishing moral agency. When youth perceive that their acts of perpetration have caused irreparable damage to others, alterations to moral agency may ensue, characterized by detachment, internal conflict, or a sense of one’s own irredeemableness (Wainryb, 2011). If youth remain unassisted, these alterations may become enduring and result in stunted psychological growth, withdrawal from potentially corrective experiences, internalized shame and guilt, and posttraumatic negative cognitions associated with their interpretation of the experience (Wainryb, 2011). Given the similarities between these outcomes of PT and the construct of MI, distortions to moral agency may be an underlying developmental process that has implications for a model of MI in children and adolescents (Wainryb, 2011). Stigma and blame by others may further exacerbate existing cognitive dissonance and moral conflict surrounding perpetration, strengthening beliefs that the self is deeply flawed, shameful, and irreparable; in contrast, studies show that family acceptance, community acceptance, and social support serve as significant protective factors against psychopathology following child soldiering (Betancourt et al., 2013; Corbin, 2008), gang involvement (Van Damme, 2017), and bullying (Holt & Espelage, 2007). Further, perceived spiritual support may also be protective against PTSD, depression, as well as behavioral and emotional problems among former child soldiers (Betancourt & Khan, 2008; Klasen et al., 2010).

In summary, the phenomenon of PT gives credence to the notion that acts of perpetration have the potential to trigger posttraumatic stress reactions among youth, particularly adolescents, as well as many of the negative cognitions, emotions, and behaviors that are associated with MI. Given that little research to date has empirically studied the association between MI and PTSD among youth, and that the boundaries and distinctions between these two constructs are still open to debate more generally (Litz & Kerig, 2019; Williamson et al., 2018), a question that warrants further investigation is whether symptoms that initially present as consistent with PTSD in the aftermath of PT actually represent facets of MI. Further empirical studies examining MI in youth are necessary to determine whether these forms of perpetration are best characterized as PMIEs.

Adapting Moral Injury to Children and Adolescents: Toward A Developmental Model

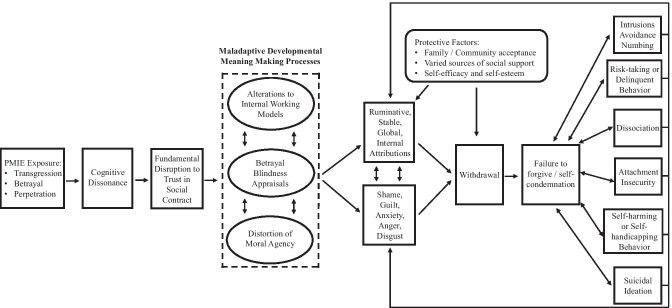

To summarize, the developmentally-oriented literatures of AT, BT, and PT collectively provide evidence to support the claim that PMIEs, including profound moral transgressions, social betrayals, and acts of perpetration, may have lasting, harmful psychological consequences for youth. These three constructs stand alone as discrete phenomena but, when integrated under a conceptual umbrella, represent theoretical facets of a developmental framework for PMIEs and MI. In addition to affirming that many of the features of MI documented in the adult literature can be extended to children and adolescents, these phenomena offer insights into developmental processes that may shape how MI emerges among youth. A theoretical model that identifies these processes and extends previous adult models (Litz et al., 2009) to children and adolescents is warranted and may lay the foundation for future research on MI among youth samples (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A theoretical developmental model of moral injury for children and adolescents.

Adapted from a model framework presented in Litz et al. (2009)

The synthesis of these three literatures, on AT, BT, and PT, offers support for the proposition that the presentation of MI in youth requires exposure to an event, whether committed by the self or others via commission or omission, which occurs in the context of high stakes situations such that, through experiencing, witnessing, or learning about the event, youth become aware that a deeply-held moral value, belief, or expectation has been violated (see first box of Fig. 1). Although these defining components of a PMIE appear to be consistent for youth and adults, there are important developmental considerations regarding the identities and roles of the important figures who are implicated in PMIEs, what situations are considered “high stakes,” and when one might become aware of the moral violation during childhood and adolescence.

Across the theory and empirical research published on AT and BT, there is a wealth of evidence to suggest that moral transgressions committed by caregivers, regardless of imminent life threat, may be associated with the deleterious outcomes akin to MI (e.g., Bernstein & Freyd, 2014). BT theory expands this notion to consider how betrayals by other trusted adults (e.g., teachers, coaches, non-caregiver family members, service professionals), peers (e.g., romantic dating partners) and institutions (e.g., schools, community organizations, sports organizations) have the potential to confer profound morally injuries. Finally, research on PT affirms that youth may experience MI as a direct result of their own acts of perpetration. Forms of perpetration relevant to the construct of MI in children and adolescents include those that involve an element of physical threat (e.g., child soldiering, gang activity, physical dating violence or bullying) as well as those that do not (e.g., emotional or electronic forms of dating aggression and bullying). Taken together, these events involve notable violations of the social contract. Given that youth are dependent on other individuals and institutions for survival and become increasingly attuned to violations of the social contract throughout development (Saltzman et al., 2018), a profound violation of the social contract (even if perpetrated by oneself) may violate expectations of the world as fundamentally safe, secure, and predictable. In short, to trust is to survive, and to violate that trust is to indirectly threaten survival.

Importantly, in order for injurious experiences to prompt MI, theory regarding BT and PT suggests that PMIE exposure must be followed by awareness of a discrepancy between the event and the moral beliefs or expectations associated with one or more of a youth’s roles or identities, ultimately causing cognitive dissonance or role conflict (see second box of Fig. 1; Freyd, 1994; MacNair, 2015). When dissonance does occur, it can fundamentally impact the way youth see themselves, others, and the world; disrupt the youth’s trust in the social contract; and leave to struggle to make meaning of the event in order to navigate their altered social world effectively in the future (see third box of Fig. 1). An important developmental consideration at this juncture is the timing of PMIE exposure; although PMIEs certainly may occur during early childhood, the phenomenon of MI may not emerge until late childhood or adolescence when youth make sufficient advances in moral, cognitive, social, and emotional development and become increasingly aware when an event has violated deeply-held moral values, beliefs, or expectations (Garrigan et al., 2018; McNeely & Blanchard, 2009; Saltzman et al., 2018; Wainryb, 2006). Accordingly, empirical research should make a concerted effort to examine when MI begins to emerge across childhood and adolescence following PMIE exposure.

Youth and adults alike attempt to make meaning of PMIEs by reconciling newfound discrepancies in how they view themselves, others, or the world with their former conceptualizations. However, youth may be set apart by specific developmental processes that characterize how they attempt to make meaning. Maladaptive developmental meaning-making processes highlighted in this review include alterations to internal working models, distortions to self or others’ moral agency, and betrayal-blindness appraisals (see fourth box of Fig. 1; Freyd, 1994, 1996; Gagnon et al., 2017; Wainryb, 2011; Weinfield et al., 2008). According to AT theory, negative alterations to a child’s previously secure internal working model may reflect difficulty effectively assimilating the experience of PMIEs involving caregivers with a former sense of the world as a trustworthy and moral place, resulting in overaccommodated expectations of future harm, exploitation, and disappointment from all others. According to PT theory, distortions to moral agency may reflect difficulty integrating such transgressions with the understanding of oneself and others as moral beings, resulting in perceptions of the self as conflicted, alienated, or irredeemable. Finally, betrayal-blindness appraisals documented in BT theory may reflect a shift of blame from the perpetrator to the self in order to maintain a necessary relationship with a perpetrator on whom the youth is highly dependent.

Evidence across studies of the AT, BT, and PT constructs suggests that these developmentally-oriented meaning-making processes may be instrumental to the development of long-lasting psychopathology. Youth may be particularly vulnerable to sustaining these strategies over time simply as a result of their relatively limited emotional, cognitive, and social resources (Nash & Litz, 2013; Wainryb, 2011); however, it is also important to acknowledge that these processes may emerge among youth as a result of the contexts in which they experience PMIEs. Unlike civilian adults, when youth experience PMIEs, they are much less likely to have the autonomy that would allow them to permanently exit the situation (e.g., home, school, community), resulting in a perceived or actual likelihood that the PMIE will happen repeatedly and the youth will be able to do little to prevent it. Accordingly, these maladaptive processes may serve the inherently developmental function of allowing youth to survive a context in which they perceive PMIEs to be an inescapable, unavoidable reality in a morally injurious world.

Following one or more maladaptive meaning-making processes, youth may perceive the cause of the event to be negative, global, internal, and stable, such that they fuse their PMIE exposure and themselves together in the belief that the event(s) must have occurred because they are inherently unforgivable, incompetent, unlovable, or unworthy (e.g., Gagnon et al., 2017; Wainryb, 2011; Weinfield et al., 2008). These cognitive attributions may be prompted or followed by self-condemning moral emotions such as shame, guilt, anxiety, anger, and disgust (see fifth boxes in Fig. 1). These self-condemning beliefs and emotions pervade the literatures on AT, BT, and PT, suggesting that they are consistently associated with the experience of moral violations among youth and warrant prominent consideration in the development of a developmental theoretical framework of MI (Betancourt et al., 2010; Klasen et al., 2015; Platt & Freyd, 2015; van der Kolk, 2005; Wainryb, 2011). To cope with their mounting distress, youth may have an urge to withdraw and condemn themselves or others implicated in the event (see sixth and seventh box of Fig. 1). Indeed, withdrawal and condemnation are conceptualized as features of AT and PT (Charuvastra & Cloitre, 2008; D’Andrea et al., 2012; Menesini et al., 2009) and emotional numbing and detachment have been noted as a means of maintaining relationships with perpetrators following BT (Freyd et al., 2007; Kerig et al., 2012).

The development of negative global attributions, condemning moral emotions, and withdrawal may be mitigated by a host of potential protective factors, including family and community acceptance, varied sources of social support (i.e., relying on more than just one person or belief), and a strong sense of self-efficacy and self-esteem (see Protective Factors box of Fig. 1; Betancourt et al., 2013; Charuvastra & Cloitre, 2008; Holt & Espelage, 2007; Nash & Litz, 2013). Of note, although spirituality and religious beliefs have been cited as a protective factor in some instances (e.g., re: PT; Betancourt & Khan, 2008; Klasen et al., 2010), they also have been identified as a risk factor (e.g., re: AT; Pressley & Spinazzola, 2015); this is consistent with findings in the adult MI literature, which has yet to arrive at a consensus regarding the role of spirituality in the etiology of MI (Drescher & Foy, 2008). Thus, this review acknowledges the importance of continued consideration of spirituality in MI among children and adolescents but does not include it in the developmental model, given that there is not conclusive evidence to indicate whether it serves as a protective factor, risk factor, or both.

When protective factors do not exist, are not available, or are not effective at modulating distress, the research on AT, BT, and PT has documented a host of psychological outcomes that may reflect a broader theoretical set of phenomena associated with developmental MI (see six outcome boxes in Fig. 1). First and foremost, exposure to PMIEs has been repeatedly associated with posttraumatic stress symptoms; consistent with research findings on adult MI, the PTSD symptoms most notably associated with AT, BT, or PT events include intrusions, avoidance, and emotional numbing (Kelley et al., 2012; Kerig et al., 2016; van der Kolk, 2005). The BT research also highlights the presence of pathological dissociation (e.g., derealization and depersonalization) as a common phenomenon following profound moral transgressions, betrayals, and perpetration among youth (Gobin & Freyd, 2009; Kerig et al., 2016; Plattner et al., 2003; van der Kolk, 2005). Such findings are absent in the adult MI literature and should be highlighted in future studies of MI among children and adolescents. Interpersonal transgressions or violations of social expectations by attachment figures may be among the most impactful (Bernstein & Freyd, 2014), and also may be directly associated the development of insecure working models of attachment (e.g., Bailey et al., 2007; Breidenstine et al., 2011). Given the centrality of attachment relationships to youth and the relative impact of potential PMIEs that involve caregivers, consideration of attachment insecurity as a possible indicator of a developmentally-informed MI construct is critical. Finally, exposure to the developmentally-oriented forms of trauma discussed in this review has also been associated with risky behaviors and behaviors indicative of difficulty discerning risk in youth, including self-harming, self-handicapping, aggression, risky sexual behavior, and delinquent behavior (Begle et al., 2011; Delker & Freyd, 2014; Espelage et al., 2012; Kerig & Becker, 2010; Maas et al., 2008; McVie, 2014; van der Kolk, 2005; Wilson et al., 2015). These outcomes are highly consistent with those discussed in Litz et al. (2009) framework for MI; however, these authors did not explicitly include suicidal ideation as an outcome, even though emerging findings suggest that MI is associated with suicide risk among military members and veterans (Ames et al., 2019; Bryan et al., 2018; Nichter et al., 2021). Research similarly indicates an association between PT and suicidal ideation (Bossarte et al., 2008; Chiodo et al., 2012; Klomek et al., 2013) among youth, suggesting that suicidal ideation warrants formal consideration as an indicator of MI in children and adolescents. Any combination of these outcomes may prompt further stigma from others, self-condemnation, and failure to forgive, which may ultimately perpetuate a cycle in which youth return to ruminate on their stable, global, internal attributions and self- or other-condemning moral emotions and become stuck in a state of MI.

Future Directions

This review aimed to provide a stepping stone toward enhancing our understanding of youth who are grappling with the aftermath of exposure to profound moral transgressions, betrayals, and acts of perpetration. The theoretical and empirical literatures reviewed here suggest that the phenomena of AT, BT, and PT during childhood and adolescence, when considered collectively, bear close correspondence to the phenomenon of MI that has been studied in adults and offers evidence suggestive that the broader construct of MI warrants consideration among children and adolescents. However, it is important to underscore that this proposed model remains theoretical and is based on extant research on analogous constructs; the phenomenon of MI remains largely unstudied formally in youth samples to date. Empirical research on the construct from a developmental perspective is needed in several respects.

First, further empirical studies are needed to examine which events identified across the AT, BT, and PT literatures in this review constitute PMIEs among children and adolescents. Utilization of newly-developed measures designed to examine links between hypothesized PMIEs and youth’s perceived exposure to morally injurious experiences would contribute to the effort to identify which adverse events are experienced as morally injurious by youth (e.g., Chaplo et al., 2019). The second important direction of future empirical research will be to formally test the impact of PMIEs (i.e., perceived moral violations, transgressions, or betrayals) on youth samples. If findings suggest that these events have a unique impact on children and adolescents, this would support for efforts to establish specific, developmentally-informed indicators of MI and to develop an instrument that would allow for the measurement of MI outcomes among youth. Thus, empirical efforts to test elements of the developmental model of MI proposed in this review are needed, as well as studies that examine the overlap and potential synthesis of AT, BT, and PT phenomena.

Research on the development of MI also will need to investigate components of the construct as they emerge across the continuum of developmental periods from early childhood through adolescence, in order to situate the construct within the context of its prerequisite building blocks, which include the emergence of cognitive capacities involved in moral reasoning (e.g., Kohlberg, 2008), conscience (e.g., Kim & Kochanska, 2019), and the development of self-conscious emotions of shame and guilt (e.g., Tracy et al., 2007; see Kerig et al., 2012).

Of primary importance to these efforts is the consideration of the intersection of cultural identity with moral development among youth. The meaning made of PMIEs is inherently shaped by cultural expectations, norms, and values (e.g., Branco, 2012); thus, MI would only be expected to emerge when an individual perceives that they or others have violated the moral or ethical expectations of their culture(s). Although the research on MI among military veterans has highlighted the potential impact that PMIEs has on spiritual and religious beliefs, there is little empirical research examining how various cultural norms or values may shape the forms of events that are perceived as morally injurious and the presentation of MI across individuals from differing racial, ethnic, SES, religious, ability level, or gender and sexual orientation backgrounds. Moreover, most studies of MI have been conducted within one specific context with a culture of its own: military members and veterans. Future research should pay close attention to any differences across various cultural identities, with focused attention to the forms of events that may constitute PMIEs among underrepresented cultural groups.

Finally, future research should attempt to identify to protective factors that reduce the likelihood of youth MI following PMIE exposure. Consistent with the phenomenon of PTSD, not all youth who experience PMIEs subsequently develop the negative outcomes associated with MI; thus, there may be environmental, biological, or sociocultural protective factors that may offer protection from the maladaptive cognitive and affective processes that underlie this psychopathology. If such protective factors specific to MI were identified and understood, these findings could help to inform future intervention efforts to foster recovery, resilience, and growth among at-risk youth exposed to PMIEs. Such intervention efforts are profoundly needed, as current interventions for PTSD largely have not demonstrated equivalent efficacy for resolving MI-related distress (Haight et al., 2016). Given the many contexts and situations in which youth are likely to be exposed to PMIEs, children and adolescents require interventions effective in assisting them with meaning-making following experiences that challenge their understanding of the moral framework of the world. With future research that extends this construct to be relevant to the developmental lens through which youth view the world, we have the opportunity to provide them the resources they need to grapple with the many complex experiences they encounter in their interpersonal worlds.

Author contributions

Both authors contributed to the conception of this theoretical review. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Mallory C. Kidwell and Patricia K. Kerig made revisions and provided additional original content. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Declarations

Competing Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ames D, Erickson Z, Youssef NA, Arnold I, Adamson S, Sones AC, Yin J, Haynes K, Volk F, Teng EJ, Oliver JP, Koenig HG. Moral injury, religiosity, and suicide risk in active duty military with PTSD symptoms. Military Medicine. 2019;184:e271–e278. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usy148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey HN, Moran G, Pederson DR. Childhood maltreatment, complex trauma symptoms, and unresolved attachment in an at-risk sample of adolescent mothers. Attachment & Human Development. 2007;9:139–161. doi: 10.1080/14616730701349721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldry AC, Sorrentino A, Farrington DP. Post-traumatic stress symptoms among Italian preadolescents involved in school and cyber bullying and victimization. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2019;28:2358–2364. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1122-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2006;1:164–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, M. R., & Freyd, J. J. (2009). Adaptive dissociation: Information processing and response to betrayal. In P. F. Dell & J. A. O'Neil (Eds.), Dissociation and the dissociative disorders: DSM-V and beyond (p. 93–105). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Barnes HA, Hurley RA, Taber KH. Moral injury and PTSD: Often co-occurring yet mechanistically different. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2019;31:A4–103. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.19020036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begle AM, Hanson RF, Danielson CK, McCart MR, Ruggiero KJ, Amstadter AB, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Longitudinal pathways of victimization, substance use, and delinquency. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:682–689. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, R. E., & Freyd, J. J. (2014). Trauma at home: How betrayal trauma and attachment theories understand the human response to abuse by an attachment figure. New Directions in Psychotherapy and Relational Psychoanalysis, 8, 18–41. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-376

- Betancourt TS, Borisova II, Williams TW, Brennan RT, Whitfield TH, de la Soudiere M, Williamson J, Gilman SE. Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers: A follow-up study of psychosocial adjustment and community reintegration. Child Development. 2010;81:1077–1095. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, T. S., Borisova, I. I., Williams, T. W., Meyers-Ohki, S. E., Rubin-Smith, J. E., Annan, J., & Kohrt, B. A. (2013). Research review: Psychosocial adjustment and mental health in former child soldiers – a systematic review of the literature and recommendations for future research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54, 17–36. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02620.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Betancourt TS, Khan KT. The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: Protective processes and pathways to resilience. International Review of Psychiatry. 2008;20:317–328. doi: 10.1080/09540260802090363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell, P. J., & Freyd, J. J. (2006). Betrayal trauma: Relational models of harm and healing. Journal of Trauma Practice, 5, 49–63. 10.1300/J189v05n01_04

- Black JE. An introduction to the moral agency scale: Individual differences in moral agency and their relationship to related moral constructs, free will, and blame attribution. Social Psychology. 2016;47:295–310. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bossarte RM, Simon TR, Swahn MH. Clustering of adolescent dating violence, peer violence, and suicidal behavior. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:815–833. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Forty-four juvenile thieves: Their characters and home-life (II) International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 1944;25:107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. (1973/1998). Attachment and Loss Vol II: Separation. London, UK: Pimlico.

- Branco, A. U. (2012). Values and socio-cultural practices: Pathways to moral development. In J. Valsiner (Ed.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of culture and psychology (p. 749–766). Oxford University Press.

- Bravo AJ, Kelley ML, Mason R, Ehlke SJ, Vinci C, Redman JC. Rumination as a mediator of the associations between moral injury and mental health problems in combat wounded veterans. Traumatology. 2020;26:52–60. doi: 10.1037/trm0000198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breidenstine AS, Bailey LO, Zeanah CH, Larrieu JA. Attachment and trauma in early childhood: A review. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma. 2011;4:274–290. doi: 10.1080/19361521.2011.609155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brémault-Phillips S, Pike A, Scarcella F, Cherwick T. Spirituality and moral injury among military personnel: A mini-review. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2019;10:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Bryan AO, Roberge E, Leifker FR, Rozek DC. Moral injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, and suicidal behavior among national guard personnel. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2018;10:36–45. doi: 10.1037/tra0000290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EA, Yates TM, Sroufe LA. Dissociation and development of the self. In: Dell PF, O’Neil JA, editors. Dissociation and the dissociative disorders: DSM-V and beyond. Routledge; 2009. pp. 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chaplo SD, Kerig PK, Wainryb C. Development and validation of the moral injury scales for youth. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2019;32:448–458. doi: 10.1002/jts.22408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charuvastra A, Cloitre M. Social bonds and posttraumatic stress disorder. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008;59:301–328. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiodo D, Crooks CV, Wolfe DA, McIsaac C, Hughes R, Jaffe PG. Longitudinal prediction and concurrent functioning of adolescent girls demonstrating various profiles of dating violence and victimization. Prevention Science. 2012;13:350–359. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KR, Ford JD, Briggs EC, Munro-Kramer ML, Graham-Bermann SA, Seng JS. Relationships between maltreatment, posttraumatic symptomatology, and the dissociative subtype of PTSD among adolescents. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation. 2019;20:212–227. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2019.1572043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A, Spinazzola J, Ford J, Lanktree C, Balustein M, Cloitre M, DeRosa R, Hubbard R, Kagan R, Liautaud J, Mallah K, Olafson E, van der Kolk B. Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals. 2005;35:390–398. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20050501-05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin JN. Returning home: Resettlement of formerly abducted children in Northern Uganda. Disasters. 2008;32:316–333. doi: 10.1111/j.0361-3666.2008.01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois C. A. (2008). Complex trauma, complex reactions: Assessment and treatment. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, S 86–100 10.1037/1942-9681.S.1.86

- Crisford H, Dare H, Evangeli M. Offence-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptomatology and guilt in mentally disordered violent and sexual offenders. The Journal of Forensic Psychology & Psychiatry. 2008;19:86–107. doi: 10.1080/14789940701596673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Currier JM, Foster JD, Isaak SL. Moral injury and spiritual struggles in military veterans: A latent profile analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2019;32:393–404. doi: 10.1002/jts.22378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier JM, Holland JM, Jones HW, Sheu S. Involvement in abusive violence among Vietnam veterans: Direct and indirect associations with substance use problems and suicidality. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2014;6:73–82. doi: 10.1037/a0032973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea W, Ford J, Stolbach B, Spinazzola J, van der Kolk BA. Understanding interpersonal trauma in children: Why we need a developmentally appropriate trauma diagnosis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82:187–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01154.x187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delker, B. C., & Freyd, J. J. (2014). From betrayal to the bottle: Investigating possible pathways from trauma to problematic substance use. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27, 576–584. 10.1002/jts.21959 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Delker BC, Smith CP, Rosenthal MN, Bernstein RE, Freyd JJ. When home is where the harm is: Family betrayal and posttraumatic outcomes in young adulthood. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma. 2018;27:720–743. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2017.1382639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis PA, Dennis NM, van Voorhees EE, Calhoun PS, Dennis MF, Beckham JC. Moral transgression during the Vietnam war: A path analysis of the psychological impact of veterans’ involvement in wartime atrocities. Anxiety, Stress, & eCoping. 2017;30:188–201. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2016.1230669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derluyn I, Broekaert E, Schuyten G, de Temmerman E. Posttraumatic stress in former Ugandan child soldiers. Lancet. 2004;363:861–863. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15734-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derluyn I, Vindevogel S, de Haene L. Toward the future: Implications of research and intervention with traumatized former child soldiers. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma. 2013;22:869–886. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2013.824058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dillard J. A slaughterhouse nightmare: Psychological harm suffered by slaughterhouse employees and the possibility of redress through legal reform. Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law & Policy. 2009;15:391–408. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle C, Cicchetti D. From the cradle to the grave: The effect of adverse caregiving environments on attachment and relationships throughout the lifespan. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2017;24:203–217. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher KD, Foy DW. When they come home: Posttraumatic stress, moral injury, and spiritual consequences for veterans. Reflective Practice: Formation and Supervision in Ministry. 2008;28:85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Drescher KD, Foy DW, Kelly C, Leshner A, Schutz K, Litz BT. An exploration of the viability and usefulness of the construct of moral injury in war veterans. Traumatology. 2011;17:8–13. doi: 10.1177/1534765610395615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elwood LS, Han KS, Olatunji BO, Williams NL. Cognitive vulnerabilities to the development of PTSD: A review of four vulnerabilities and the proposal of an integrative vulnerability model. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:87–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Basile KC, Hamburger ME. Bullying perpetration and subsequent sexual violence perpetration among middle school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, Rothman E. Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2013;131:71–78. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnsworth JK, Drescher KD, Evans W, Walser RD. A functional approach to understanding and treating military-related moral injury. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2017;6:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2017.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farnsworth JK, Drescher KD, Nieuwsma JA, Walser RB, Currier JM. The role of moral emotions in military trauma: Implications for the study and treatment of moral injury. Review of General Psychology. 2014;18:249–262. doi: 10.1037/gpr0000018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freyd, J. J. (1994). Betrayal trauma: Traumatic amnesia as an adaptive response to childhood abuse. Ethics & Behavior, 4, 307–329. 10.1207/s15327019eb0404_1

- Freyd JJ. Betrayal trauma: The logic of forgetting childhood abuse. Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Freyd, J. J. (2013). Preventing betrayal. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 14, 495–500. 10.1080/15299732.2013.824945 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Freyd JJ, DePrince AP, Gleaves DH. The state of betrayal trauma theory: Reply to McNally — conceptual issues and future directions. Memory. 2007;15:295–311. doi: 10.1080/09658210701256514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freyd JJ, Klest B, Allard CB. Betrayal trauma: Relationship to physical health, psychological distress, and a written disclosure intervention. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2005;6:83–104. doi: 10.1300/J229v06n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon KL, Lee MS, DePrince AP. Victim-perpetrator dynamics through the lens of betrayal trauma theory. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2017;18:373–382. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrigan B, Adlam ALR, Langdon PE. Moral decision-making and moral development: Toward an integrative framework. Developmental Review. 2018;49:80–100. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2018.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gobin RL, Freyd JJ. Betrayal and revictimization: Preliminary findings. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2009;1:242–257. doi: 10.1037/a0017469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, B. J., Purcell, N., Burkman, K., Litz, B. T., Bryan, C. J., Schmitz, M., Villierme, C., Walsh, J., & Maguen, S. (2019). Moral injury: An integrative review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32, 350–362. 10.1002/jts.22362 [DOI] [PubMed]