Abstract

Rationale & Objective

Noncitizen, undocumented patients with kidney failure have few treatment options in many states, although Illinois allows for patients to receive a transplant regardless of citizenship status. Little information exists about the experiences of noncitizen patients pursuing kidney transplantation. We sought to understand how access to kidney transplantation affects patients, their family, health care providers, and the health care system.

Study Design

A qualitative study with virtually conducted semistructured interviews.

Setting & Participants

Participants were transplant and immigration stakeholders (physicians, transplant center and community outreach professionals), and patients who have received assistance through the Illinois Transplant Fund (listed for or received transplant; patients could complete the interview with a family member).

Analytical Approach

Interview transcripts were coded using open coding and were analyzed using thematic analysis methods with an inductive approach.

Results

We interviewed 36 participants: 13 stakeholders (5 physicians, 4 community outreach stakeholders, and 4 transplant center professionals), 16 patients, and 7 partners. The following seven themes were identified: (1) devastation from kidney failure diagnosis, (2) resource needs for care, (3) communication barriers to care, (4) importance of culturally competent health care providers, (5) negative impacts of policy gaps, (6) new chance at life after transplant, and (7) recommendations for improving care.

Limitations

The patients we interviewed were not representative of noncitizen patients with kidney failure overall or in other states. The stakeholders were also not representative of health care providers because they were generally well informed on kidney failure and immigration issues.

Conclusions

Although patients in Illinois can access kidney transplants regardless of citizenship status, access barriers, and health care policy gaps continue to negatively affect patients, families, health care professionals, and the health care system. Necessary changes for promoting equitable care include comprehensive policies to increase access, diversifying the health care workforce, and improving communication with patients. These solutions would benefit patients with kidney failure regardless of citizenship.

Index Words: Kidney transplant, undocumented immigrants, end-stage kidney disease, kidney failure, qualitative study, health inequity

Plain-Language Summary.

Health inequities exist among patients with kidney failure by citizenship and documentation status owing to differential access to treatment options. In Illinois, patients with kidney failure can qualify for transplants, although little is known about the experiences of noncitizen patients who have become eligible for a kidney transplant. To help patients receive transplants, the nonprofit Illinois Transplant Fund provides health insurance premium support for patients who do not qualify for publicly funded health insurance and are unable to pay the premiums for private health insurance. We conducted interviews with kidney transplantation stakeholders and patients who have received assistance through the Illinois Transplant Fund to better understand the experiences of this unique patient group. Although transplant access has been crucial and lifesaving, significant barriers continue to exist for undocumented patients, as well as burdens on the health care teams and system. Policy changes promoting equitable transplant access could benefit patients overall, as well as families, health care providers, and the health care system at large.

Between 5,500 and 8,857 undocumented immigrants (noncitizens without a legal immigration status)1 with kidney failure live in the United States, the majority being Hispanic.2 Hispanic patients with chronic kidney disease have 1.5-2× higher odds of progressing to kidney failure—necessitating dialysis or transplant—compared with non-Hispanic patients.3 Patients with kidney failure being treated with maintenance dialysis or transplant are considered to have kidney failure.

Although transplant is the ideal treatment due to positive impacts on quality of life, morbidity, mortality, and cost effectiveness,4 transplant needs exceed that of available organs, resulting in long waitlists.5

Access to kidney transplants in the United States is heavily impacted by financial and insurance hurdles. These barriers are especially prominent among the undocumented population.6, 7, 8, 9 More than 25% of noncitizens and 42% of undocumented residents are uninsured, compared with 8% of US citizens.10 Undocumented patients do not qualify for federally subsidized assistance programs, and without private health insurance, they often cannot obtain standard-of-care dialysis—let alone transplants.11 Care provisions for undocumented patients vary widely by state, ranging from emergency-only dialysis to routine dialysis, and rarely, transplant.11 Further, undocumented patients also face barriers related to policies, financial costs, a lack of linguistically and culturally concordant transplant information, distrust of the medical system, and fear.4 The injustice of this access inequity is exacerbated by the fact that in some areas of the United States, 10% of organs come from undocumented donors, whereas less than 1% of donated organs go to undocumented recipients.12

In 2014, Illinois passed Senate Bill 741, becoming one of the first states to allow kidney transplants for undocumented patients with kidney failure through language in the Medicaid program, allowing undocumented patients to receive kidney transplantation state coverage.13 Theoretically this was a breakthrough in increasing transplant access; however, eligibility criteria, reimbursement restrictions, and state budgetary issues limited the legislation’s impact, and only one person received a transplant through this route. The Illinois Transplant Fund (ITF), a nonprofit 501c3 organization, was founded by the Gift of Hope Organ and Tissue Donation Network to provide insurance premium assistance, allowing for patients to receive transplants (primarily kidney) and post-transplant care, allowing for undocumented patients to access transplant options. ITF assists patients with financial needs (income <200% poverty level), who are ineligible for subsidized health care, and Illinois residents for 3 or more years, regardless of citizenship status.14 More than 90% of ITF’s patients identified as Hispanic.

Prior studies describe the dialysis experience of undocumented patients, including emergent and scheduled dialysis.15,16 Little is known regarding the experiences of undocumented patients who have become eligible for kidney transplant. We aimed to gather experiences of noncitizen patients with kidney failure, from diagnosis through transplant. We conducted interviews with patients, their families, and stakeholders involved in medical care or policies for noncitizens with kidney failure. We sought to understand how access to kidney transplantation affects the life of patients, family members, health care providers, and the health care system, and how the transplant policy could be improved.

Methods

We conducted semistructured interviews with medical and policy stakeholders involved in caring for patients with kidney failure in Chicago, Illinois, and patients and families who received financial assistance through ITF. The study was approved by the Rush University Medical Center Institutional Review Board, IRB #20022002. All participants provided written informed consent before study procedures. Stakeholder and patient interviews were conducted from June-August 2020, and January-July 2021, respectively.

Participants

Stakeholders

ITF provided contact information for potential participants through a list of stakeholders from local nonprofit agencies, advocacy organizations, and medical centers. Overall, 30 stakeholders were contacted via email, 14 responded and were eligible to participate, and 13 completed interviews (n = 1 opted to not participate after the initial screening). Stakeholders were employed at institutions providing kidney transplantation for patients receiving ITF assistance or had experience working with patients receiving ITF assistance. Interviews focused on undocumented patients, given the unique policies in Illinois allowing for transplants among this population. Participants were categorized as follows: (1) physicians providing care for patients with kidney failure (eg, nephrologists and transplant surgeons), (2) transplant center professionals (eg, nurses, financial counselors, and social workers), and (3) community outreach stakeholders working in health care access or immigration policy advocacy. Participants were encouraged to refer colleagues to participate.

Patients

ITF mailed 2 recruitment letters (in English and Spanish) to all their active patients (n = 156), followed by one text message on behalf of the research team, describing the study, and included contact information for those interested. Eligibility was assessed by telephone. In total, 24 patients responded, 22 patients were eligible (n = 1 patient was ineligible because the patient received a liver transplant and n = 1 patient decided not to participate further), and 16 completed interviews. Reasons that eligible participants did not complete interviews (n = 6) included technological issues, a lack of time owing to managing health problems, or lost contact following the initial screening. Eligibility criteria included age of 18 years or older, approved for support by ITF, on a transplant waitlist or received a transplant, fluent in Spanish or English, and had access to a device for completing an interview. Due to the significant role that family/caregivers play in this population, patients could complete the interview alone or with a partner (age ≥18 years and fluent in English or Spanish). Citizenship status was not collected to protect participant privacy.

Interview Methods

Owing to coronavirus disease 2019 restrictions, interviews were conducted via video conferencing or telephone, based on the participant’s preference. No formal pilot testing was conducted; however, the research team met regularly during the interview process in which the interview guide was deemed appropriate, and no changes were made. Interviewers briefly introduced themselves, including their name, role in the study, occupation, and purpose of the work before beginning any research procedures or reviewing the consent. Interviewers had no prior relationship with participants before interviews. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and deidentified. Transcripts for interviews completed in Spanish were translated by certified translators. Interviews were completed within 1 hour.

Stakeholders

Three research team members conducted stakeholder interviews (EBL, BSL-M, and YIG; qualifications are provided in Item S1). All stakeholders completed a brief demographic questionnaire collecting information on age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, employment, connection with ITF, and the length of time working in this setting. Interviewers used 1 of 2 semistructured guides to ensure that questions were relevant to the stakeholders’ role, with questions targeting medical or community outreach/policy stakeholders (Item S2). Questions covered barriers faced by undocumented patients with kidney failure, experience with undocumented patients, knowledge of the ITF, views on health care policies affecting care for patients with kidney failure, and health outcomes of undocumented patients with kidney failure.

Patients

Patient interviews were conducted by ME-M (Item S1). Participants (and partners, if applicable) completed a brief demographic questionnaire, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, employment, transplant status (patients), and relationship with the patient (partners). The semistructured interview guide included questions regarding the patient’s overall experience during all stages of kidney failure care (diagnosis, dialysis, and transplant), including their experience with ITF (Item S3).

Analytical Approach

Interview transcripts were coded using open coding. Thematic analysis using an inductive approach, driven by grounded theory, was used. Microsoft Word and Excel were used for all interview coding and analyses. Bilingual research team members (ME-M and MLA-P) compared Spanish transcripts to ensure accurate coding. Team members independently reviewed the transcripts, identified potential codes, came to a consensus regarding codes, and developed a codebook representing the interview content and findings. Coding was first conducted independently, disagreements were discussed, and a consensus was reached. The analysis team met regularly to discuss progress while interviews were ongoing. Thematic saturation was determined to have been reached once no new information emerged, and all interested participants had been interviewed. The team agreed that no further recruitment was needed. Transcripts for stakeholder and patient interviews were coded separately but considered together for identifying themes.17 Codebooks were created separately for stakeholder and patient interviews; however, similar themes were found between stakeholder and patient interviews. Owing to these similarities and the complementary nature of the responses, the 2 codebooks were integrated into a single analysis, with overarching themes capturing experiences of stakeholders and patients. Coded transcripts were reviewed in relation to the themes to ensure consistent coding and generation of meaningful themes that captured the entire set of codes.17 Participants did not provide feedback on findings.

Results

Overall, 36 participants were interviewed, which includes 13 stakeholders (5 physicians, 4 community outreach stakeholders, and 4 transplant center professionals), 16 patients, and 7 partners (Table 1). In all, 62% of stakeholders were men and 23% identified as of Hispanic, Latinx, or of Spanish origin. Patients had a median age of 43 years (interquartile range, 38.5-53.5), 75% were men, 94% identified as of Hispanic, Latinx, or Spanish origin, 69% had less than a high-school diploma, 43% were unemployed, and 88% had received a transplant. Additional demographics are provided in Table 1. Most (81%) patient interviews were conducted in Spanish.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristics | Medical and Policy Stakeholders (n = 13) | Patients (n = 16) | Patient Partners (n = 7) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y), median (IQR) | 47 (46.5-52.5) | 43 (38.5-53.5) | 38 (22-57) |

| Male sex, N (%) | 8 (61.5) | 12 (75.0) | 2 (28.6) |

| Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity, N (%) | 10 (76.9) | 15 (93.8) | 7 (100) |

| Education, N (%) | |||

| Less than high school | 0 (0.0) | 11 (68.8) | 4 (57.1) |

| High-school diploma | 0 (0.0) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (14.3) |

| Some college or associate degree | 1 (7.7) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (28.6) |

| College graduate or baccalaureate degree | 3 (23.1) | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Master’s degree | 4 (30.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Doctoral degree | 5 (38.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Role, N (%) | |||

| Physician | 5 (38.5) | ||

| Community outreach | 4 (30.8) | ||

| Transplant center professional | 4 (30.8) | ||

| Employment status, N (%) | |||

| Unemployed | 7 (43.8) | 3 (42.9) | |

| Full-time student | 2 (12.5) | 1 (14.3) | |

| Employed part time | 3 (18.8) | 1 (14.3) | |

| Employed full time | 4 (25.0) | 2 (28.6) | |

| Transplant status, N (%) | |||

| Received a transplant within the last year | 5 (31.3) | ||

| Received a transplant over a year ago | 9 (56.3) | ||

| On the wait list | 1 (6.3) | ||

| On the wait list for a second transplant | 1 (6.3) | ||

| Relationship with the patient, N (%) | |||

| Spouse | 5 (71.4%) | ||

| Child | 1 (14.3%) | ||

| Sibling | 1 (14.3%) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

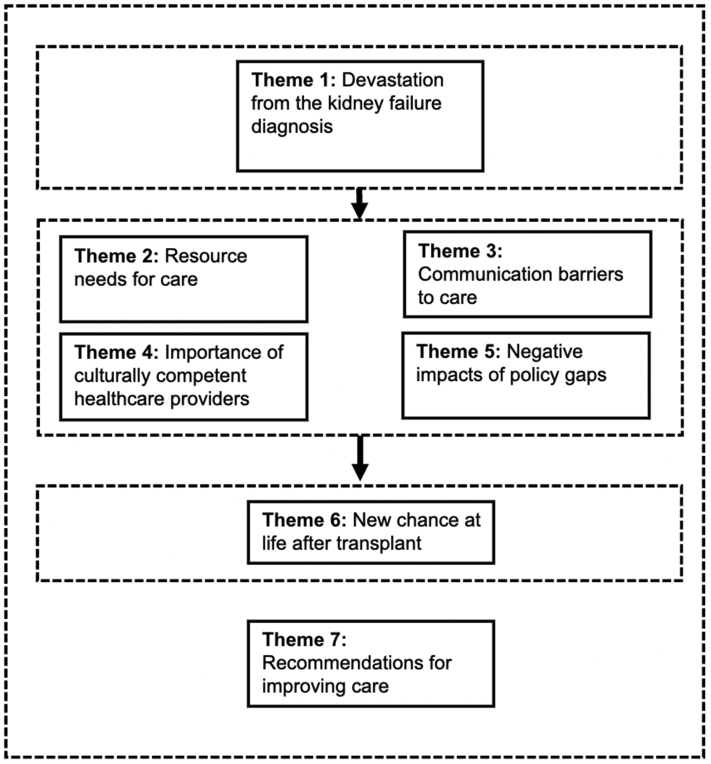

The following 7 themes were identified: (1) devastation from kidney failure diagnosis, (2) resource needs for care, (3) communication barriers to care, (4) importance of culturally competent health care providers, (5) negative impacts of policy gaps, (6) a new chance at life after transplant, and (7) recommendations for improving care. Themes, subthemes, and illustrative quotes are provided in Table 2. Overall, when patients first receive a diagnosis of kidney failure (theme 1), they encounter numerous barriers in accessing care (themes 2-5); however, if barriers are overcome and the patient receives a transplant (theme 6), they get a “new chance at life.” Throughout all stages, opportunities exist for improvement. Participants described recommendations that would improve care and reduce barriers (theme 7) (Fig 1).

Table 2.

Themes, Subthemes, and Examples From Patient and Stakeholder Interviews Regarding Kidney Transplant Experiences

| Theme | Subtheme | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Devastation from kidney failure diagnosis |

|

Patient: “… after like dialysis days you feel really exhausted and I know some people at the center would tell me, ‘All I do is I go home and sleep.’ And I’m like, ‘I can’t, I have to work.’” Social worker: “they start dialysis, and everything goes, starts going down: their finances, their job, sometimes they lose jobs... for being in dialysis...” Patient: “(After the diagnosis, we felt) very depressed. Especially, because of the sense of life you are used to. We were used to working very hard to achieve our dreams, right? And when receiving the diagnosis, well now everything crumbled. The person who is diagnosed is not the only one who is ill, but this encompasses the entire family. I mean, the whole family is ill.” Patient’s spouse: “Firstly, it was emotionally, and then it was financially because well, we had our apartment and well, we had to leave it, and come live with one of my sons, and well, everything crumbled.” |

| Theme 2: Resource needs for care |

|

Patient: “Without the ITF I would not have been able to get the transplant because I would not have had the means to pay for the medical insurance I am usually using.” Patient: “I did have transportation issues because sometimes when I left dialysis I had no transportation, especially because the bus does not go where I live or anything. So, initially that did affect me, but thank God my son’s school found out about my situation and they donated a car.” Patient: “I have a son who is a bit older, and he would tell me, he would tell me, ‘Ma, go to get that (a transplant) done.’ And he showed me more videos of people getting the transplant, that they would get one more life and all that.” Patient: “Okay well, the opportunity was presented here with the family, with my son, who donated the kidney. Well, I think he saw how I struggled when I received dialysis because at times I had a lot of cramps, and well, I did have a lot of pain. And well, I think he noticed all that, and I also struggle a lot because I was with him, he supported me a lot.” |

| Theme 3: Communication barriers to care |

|

Nephrologist: “... For the undocumented... we also have a lot of problems because of the fear of them getting deported. So sometimes they’re afraid of giving their information so that we can get them enrolled in this program and then support them.” Transplant nurse: “(There’s a) lack of information, or just that they (patients) get bombarded with so much information when they know they’re going to start dialysis. They are getting information from the dialysis center, which can be overwhelming, and then as far as transplant, they might get a lot of information here (transplant center). Especially if their primary language is Spanish, using the interpreters, a lot can get lost in translation.” Social worker: “The way health care is run in the US is different than much of the world... then insurance, the way we have insurance doesn’t exist anywhere really in the world either, and so there’s a lot of, there’s learning curve on figuring out how to navigate all those systems simultaneously and they are overwhelming if you’re feeling well, but, then add on the complexities of not feeling well and it’s hard.” Transplant surgeon: “I think there’s less offer for transplant. Less frequently these people are approached to have a transplant because I don’t think there’s clarity that we can still do the surgery for these (undocumented) patients.” Patient: “There are many people who are in our situation, and overall, because of fear and ignorance. They do not dare to ask…” Patient: “... many people are really not aware of this type of disease. But when you get it, well, you still do not know what is happening or how it works.” |

| Theme 4: Importance of culturally competent health care providers |

|

Transplant outreach consultant: “… I’m always educating myself about any changes, how we can actually give other individuals who are undocumented the access to transplant and how do we get them to that point.” Transplant nurse: “The surgeons speak Spanish, and we have translators in the clinic, so that we are able to speak Spanish throughout and have them understand that... And so, he makes sure that we have our Hispanic outreach patients are paid with a nurse who speaks Spanish. And we think that helps them kind of move along the process and helps them better understand.” Nephrologist: “so, it’s a matter of gaining that trust from them. And once you break that barrier, they really follow what you ask them to do. The problem is a much more difficult task, like in the Hispanic community, the Hispanic community in my case, of course I’m Latino, I know what to hit, I know cultural things and belief, and I know specifically how to, and again, I know the cultural background for them is very important but also for the patient it’s very comfortable, they can talk to me in Spanish and what they say I get it right away. So that has been a plus in my case.” |

| Theme 5: Negative impacts of policy gaps |

|

Transplant surgeon: “I can tell you that this (caring for undocumented patients) is pretty resource intensive for our team. From financial counselors, social workers, and the pharmacists trying to get medications that are cheaper, accommodating to a lot of the things that are barriers for patients, for due to insurance coverage issues or whatever, so it is much more resource intensive.” Patient: “I obviously received hemodialysis, all that, but was hospitalized a couple of days more than the number of days I should have been in the hospital. Because of my immigration situation I had to wait to receive treatment in a clinic outside the hospital. So, I think I was about 9 days at the hospital. But I could have gone home on the 5th day, but because of this I was not sent home, because there was no certainty about treatment. So, until they found a place, I was able to leave.” |

| Theme 6: A new chance at life after transplant |

|

Patient’s spouse: “you could see the difference immediately in his energy level because as he mentioned, he did not want to do anything. He was just laying down, and now that he has the transplant, he does many things. He gladly takes the boy to the park 2 or 3 days in a row, he does not get tired, he is very active. It is very different from before and after the transplant.” Patient: “No well, my experience is like I tell my wife that, well, I was born again.” Patient: “(speaking about becoming an organ donor) Because I have even told my wife that now that I have been through that disease and that, God forbid, I suddenly die, or something happened, I can help someone. I am as you say, you are dead, what do you want things? And you are happy to know that you are going to make many people happy with your things which are not going to be useful for you, and people are going to be grateful, even though they do not know you, they are going to be grateful that you saved that person’s life.” Patient: “I think being a donor is a big thing. I really didn't consider any of this. Honestly, I didn't even pay attention to donor organs. None of that like I didn't think about it how I think about it now. I think it's something huge and I encourage my family to do it all the time.” Stakeholder: “when individuals who have been working so hard to get a transplant and they didn’t have the insurance and then ITF came about and they got the transplant, they hang onto their transplant.” |

| Theme 7: Recommendations for improving care |

|

Social worker: “From a systems perspective... if there were more avenues to accessing insurance so that you had a way to get a transplant, that is from our system, that’s a better option for our healthcare system and our society. Because it is more cost effective in the grand scheme of things. Besides, medically it’s also, from a systems perspective, it’s a better program.” Stakeholder: “… if there could be some funding behind the authorization that allows the dialysis only Medicaid plan to also include transplant that would open the door to more people for transplant because the marketplace like plan still, not everyone has access to that.” |

Abbreviation: ITF, Illinois Transplant Fund.

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram illustrating interconnections between themes.

Overall, when patients first receive a diagnosis of kidney failure (theme 1), they encounter numerous barriers in getting the care that they need (themes 2-5); however, if these barriers can be overcome and the patient receives a transplant (theme 6), they essentially get a “new chance at life.” Throughout all stages of care, there are opportunities for improvement, and our participants described recommendations that would improve care and help overcome these gaps (theme 7).

Theme 1: Devastation From Kidney Failure Diagnosis

The kidney failure diagnosis was devastating to many patients and families, with effects reaching beyond the patient’s physical health. One patient’s husband expressed that “when receiving the diagnosis, well, now everything crumbled,” not only for the patient, stating “the whole family is ill.” Dialysis was particularly difficult for patients, as it fundamentally changed their lives (ie, inability to work, join family activities, limited diet, and decreased energy). Although many patients described having no choice but to work while undergoing dialysis, exhaustion prevented them from working the same hours and/or intensity. Patients’ and families’ financial status was strained further when patients were unable to work fully because they often already experienced financial hardships.

Theme 2: Resource Needs for Care

Insurance was crucial to qualify for transplant. One patient stated, “Without the ITF I would not have been able to get the transplant because I would not have had the means to pay for the medical insurance I am usually using.” Although insurance was necessary, it was not sufficient for patients to receive needed care because financial and transportation barriers also existed. Some transplant centers required savings of thousands of dollars to prove having adequate funds for posttransplant care before qualifying for a transplant. Stakeholders explained that this requirement was unattainable for many patients, given existing financial difficulties. Although financial issues are not exclusive to noncitizen patients, the financial hardships for noncitizens were greater because they did not have access to public insurance and other assistance available to citizens or legal residents.

Transportation barriers were common because many patients traveled for numerous medical appointments and public transportation options were limited. Family members were crucial in overcoming resource barriers. The family often provided transportation to and from dialysis and medical appointments, cared for patients before and after surgery, and provided emotional support. The family also researched resources and options for patients and, in some cases, donated their kidney. Community members and clergy support included activism, connecting patients to resources, and fundraising.

Theme 3: Communication Barriers to Care

Communication barriers—including those related to fear, language, culture, a lack of knowledge, and misconceptions—prevented patients from entering and navigating the health care system. Patients feared they would be “flagged” by the medical system for their immigration status when seeking care and potentially be deported. Significant language barriers existed because many noncitizens primarily spoke Spanish. Furthermore, patients and families often did not understand the unique complexities of the US health care system. When diagnosed with kidney failure, many patients described that they did not know about the disease, nor what questions to ask. Patients presumed that they would not qualify for a transplant, solely relied on information shared by health care professionals, and described being thrust into care and treatment. One patient described “you do not know what is going on... they put the needle in, and this and that, and you must go to another doctor to get the fistula and all that... it all happens very fast. They try to put everything on you very fast because, um, it is urgent, right? But at the same time, they do not let you think and analyze what is going on with your life.” Health care personnel often had misconceptions and lacked knowledge about transplant eligibility and ways for patients to obtain insurance, which were passed on to patients.

Theme 4: Importance of Culturally Competent Health Care Providers

Owing to the numerous barriers, interpersonal relationships were crucial for connecting to care. Stakeholders described that they often dedicated additional time to identify and navigate treatment options for undocumented patients. Cultural competency was crucial for connections to resources and care, and oftentimes, connections were made by health care professionals who identified as of Hispanic, Latinx, or of Spanish origin, stating that they could connect and communicate better with patients owing to shared language and cultural understanding. Some patients attributed their opportunity to receive a transplant to Spanish-speaking staff knowledgeable about options for noncitizens.

Theme 5: Negative Impacts of Policy Gaps

Policies limiting access to kidney care for undocumented immigrants with kidney failure were stressors for health care professionals because they felt limited in the care they could provide. One patient described being hospitalized for additional days because it was unclear where they could receive outpatient treatment when discharged owing to the immigration status. Several stakeholders expressed frustration that policy issues created inefficiencies because they were required to navigate complicated and changing policies and systems. Finally, they highlighted the inefficiencies embedded in the US health care system and the impact on all patients, regardless of citizenship status.

Theme 6: A New Chance at Life After Transplant

Receiving a transplant was described as “lifesaving,” with some patients saying they were reborn and given a new or second chance at life. Their motivation for seeking a transplant was often due to the debilitation of dialysis. Patients described returning to work, partaking in previously enjoyed activities, having a new appreciation for life, completing new goals, and advocating for others. Although some patients experienced complications, overall, they expressed feeling grateful for the opportunity to receive a transplant. Furthermore, they used their experiences to educate others about kidney failure, encourage friends and families to become donors, and help others navigate the health care system to receive a transplant.

When asked to contrast outcomes for citizens and undocumented patients, stakeholders, overall, expressed that health outcomes were similar but that undocumented patients were particularly appreciative for the opportunity and worked hard to maintain it because of the difficulty to obtain it.

Theme 7: Recommendations for Improving Care

Stakeholders consistently stated that without large, systemic changes to the health care system, many solutions would only add to the inefficiencies of the current patchwork system and lead to additional responsibilities for the already overworked providers. They expressed how systemic changes were needed to improve access and quality of care for all patients with kidney failure. Expanding Medicaid benefits to cover transplants in addition to dialysis was suggested. Stakeholders and patients recommended increasing awareness locally about transplant options for undocumented patients, including informing personnel at dialysis and medical centers about ITF. Many patients expressed the need for more bilingual staff and programs to reach patients who fear asking questions because of language barriers.

Discussion

Our qualitative results indicate several themes regarding experiences of undocumented patients with kidney failure in Illinois, where transplant options are available for this patient population. The devastation of a kidney failure diagnosis compounded with multiple barriers to care makes it difficult for undocumented patients to receive proper care. The need for culturally competent, bilingual providers, and resources was crucial in patients having successful transplants, which were life changing. Future improvements in large-scale health care policies could provide further access to transplant regardless of citizenship status.

Illinois legislation allowing noncitizens and undocumented patients to receive kidney transplants was largely put into place because it would reduce costs for the state’s emergency dialysis program.13 Although Illinois has substantially fewer barriers to transplants and care for undocumented patients with kidney failure compared with most states, patients still face barriers to receiving care, even with insurance coverage. Some barriers are specific to undocumented patients owing to the immigration status, including the inability to qualify for assistance programs and deportation fears. However, some barriers are faced by patients regardless of citizenship status, including long travel distances for care and financial hardships. These barriers are consistent with the results from a prior mixed-methods study examining provider perceptions of barriers faced by patients undergoing kidney transplant evaluations,18 including transportation, low health literacy, the distance to transplant centers, and a low socioeconomic status.

Although our interviews with patients mainly detailed success stories, these stories were told by patients and their families who had been connected to care. Stakeholders, however, described experiences with a wider range of patients, including those who ultimately could not get a transplant. Stakeholders described the hardships in providing care in an environment characterized by resource constraints and policy gaps. Overall, limiting access to transplants for undocumented patients with kidney failure negatively affected not only the patients and their families but also the providers. Physician stakeholders described feeling distressed about limited options available for noncitizens relative to other patients with kidney failure. This is consistent with the emotional tolls physicians face in emergency-only dialysis settings.19 In states in which emergency-only dialysis is the sole option for undocumented patients with kidney failure, clinicians face moral distress, burnout, and emotional exhaustion from not being able to provide standard of care, witnessing needless suffering, and overextending themselves to bridge gaps in care.19 However, many also described that noncitizen patients with kidney failure often had good outcomes posttransplant, which is consistent with work using the US Renal Data System because insured, nonresident aliens (presumed to be undocumented patients) had better transplant outcomes, compared with US citizens.20

Our results are also consistent with work reporting the experience of caregivers of undocumented patients relying on emergency-only hemodialysis.21 Caregivers in that study provided emotional, physical, and economic support, advocated for the patient, and helped navigate the health care system. Family members reported anxiety from watching their loved ones suffer.21 Although our patients did not rely on emergency-only dialysis, similarities existed as family members and friends had to consistently advocate for their loved ones with kidney failure, find available resources, and experience stress related to immigration status and having a loved one with a serious disease.

Communication barriers and knowledge gaps regarding kidney disease have been described among other patient groups.22, 23, 24, 25 Unidirectional communication, including infrequently questioning treatment regimens, is consistent with work describing communication barriers among veterans with chronic kidney disease. These veterans often perceived their role as the “listener” when interacting with their health care provider.22 This unidirectional communication meant that patients often had limited knowledge of their chronic kidney disease, including confusion regarding laboratory measures and medications. Communication barriers faced by our participants were further complicated by cultural differences, language, fear regarding immigration status, unfamiliarity with the US health care system, and complex rules regarding transplantation. Our interviews highlight the importance of cultural competency among health care providers and staff, including having language-concordant staff, health care personnel, and interpreters at every level, and culturally tailored educational materials and outreach programs. Social challenges among Latinx patients with kidney failure have also been described,26 demonstrating that communication and cultural barriers lead to low-quality care and difficulty accessing care. Taken together, the need for consistent and widespread messaging regarding resources, access, and kidney failure overall is needed to ensure that patients are not inappropriately discouraged from transplantation when they may in fact qualify.

One policy change suggested by stakeholders—expanding state programs to cover transplants instead of only dialysis—has been passed in Illinois. In July 2021, the Illinois Governor signed legislation directing the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services to cover posttransplant care for noncitizen kidney transplant recipients. Patients began to enroll in this new state benefit in November 2021. Although not completely comprehensive, 75% of ITF patients will be eligible for the program.

This study provides new information from a unique sample of noncitizen patients who qualified for a kidney transplant. Including patients and stakeholders allowed for a robust understanding of kidney transplantation for noncitizens/undocumented patients. However, limitations exist. First, the experiences of these patients are not representative of undocumented kidney failure patients in the United States, given the vast differences in policies across the country. Second, because of the cultural emphasis on their family, patients could complete their interview with a partner. Responses may have differed for participants completing the interview alone versus those completing with a partner. Third, stakeholders were generally well informed regarding kidney failure and/or immigration and, therefore, not necessarily representative of health care providers overall. Finally, interviews were completed virtually. Our goal was to accommodate participants, although the virtual environment/telephone may have led to a different interview dynamic as compared with in person.

In conclusion, although patients in Illinois can access kidney transplants regardless of citizenship status, access barriers and health care policy gaps continue to negatively affect patients, their families, health care professionals, and the health care system. Improving access to kidney failure care is needed and can benefit patients regardless of citizenship status, as well as the people who care for this patient population.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Yumiko I. Gely, BS, BHS, Maritza Esqueda-Medina, BS, Tricia J. Johnson, PhD, Melissa L. Arias-Pelayo, BS, Nancy A. Cortes, R.T. (R), CPhT, BHS, Zeynep Isgor, PhD, Elizabeth B. Lynch, PhD, Brittney S. Lange-Maia, PhD, MPH.

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: BSL-M, EBL; data acquisition: BSL-M, EBL, YIG, NAC, ME-M; data analysis/interpretation: BSL-M, YIG, TJJ, MLA-P, NAC, ZI; supervision or mentorship: BSL-M. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

This study was supported by a research grant awarded to Rush University Medical Center provided by the Gift of Hope Organ and Tissue Donor Network. The Illinois Transplant Fund, a nonprofit organization created by the Gift of Hope Organ and Tissue Network, assisted in participant recruitment. However, the funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Peer Review

Received October 10, 2022. Evaluated by 2 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from an Associate Editor and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form March 26, 2023.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

Items S1-S3.

Supplementary Material

Items S1-S3.

References

- 1.Undocumented immigrant. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/undocumented_immigrant Updated 2022.

- 2.Rodriguez R., Cervantes L., Raghavan R. Estimating the prevalence of undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease in the united states. Clin Nephrol. 2020;93(1):108–112. doi: 10.5414/CNP92S119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hounkpatin H.O., Fraser S.D.S., Honney R., Dreyer G., Brettle A., Roderick P.J. Ethnic minority disparities in progression and mortality of pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease: a systematic scoping review. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):217. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-01852-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rizzolo K., Cervantes L. Barriers and solutions to kidney transplantation for the undocumented latinx community with kidney failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(10):1587–1589. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03900321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Understanding the transplant waitlist. https://www.kidney.org/content/understanding-transplant-waitlist#:∼:text=Once%20you%20are%20added%20to,geographical%20regions%20of%20the%20country

- 6.Laurentine K.A., Bramstedt K.A. Too poor for transplant: finance and insurance issues in transplant ethics. Prog Transplant. 2010;20(2):178–185. doi: 10.7182/prtr.20.2.xhu0678655331488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herring A.A., Woolhandler S., Himmelstein D.U. Insurance status of US organ donors and transplant recipients: the uninsured give, but rarely receive. Int J Health Serv. 2008;38(4):641–652. doi: 10.2190/HS.38.4.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kucirka L.M., Grams M.E., Balhara K.S., Jaar B.G., Segev D.L. Disparities in provision of transplant information affect access to kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(2):351–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park C., Jones M.M., Kaplan S., et al. A scoping review of inequities in access to organ transplant in the United States. Int J Equity Health. 2022;21(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01616-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Health coverage of immigrants. 2022. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-of-immigrants/

- 11.Cervantes L., Mundo W., Powe N.R. The status of provision of standard outpatient dialysis for US undocumented immigrants with ESKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(8):1258–1260. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03460319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douthit N.T., Old C. Renal replacement therapy for undocumented immigrants: current models with medical, financial, and physician perspectives-a narrative review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(10):2246–2253. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05237-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ansell D., Pallok K., Guzman M.D., Flores M., Oberholzer J. Illinois law opens door to kidney transplants for undocumented immigrants. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(5):781–787. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lange-Maia B.S., Johnson T.J., Gely Y.I., Ansell D.A., Cmunt J.K., Lynch E.B. End stage kidney disease in non-citizen patients: epidemiology, treatment, and an update to policy in illinois. J Immigr Minor Health. 2022;24(6):1557–1563. doi: 10.1007/s10903-021-01303-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cervantes L., Fischer S., Berlinger N., et al. The illness experience of undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):529–535. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez R.A. Dialysis for undocumented immigrants in the United States. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015;22(1):60–65. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun V., Clarke V. In: APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological. Cooper H., Camic P.M., Long D.L., Panter A.T., Rindskopf D., Sher K.J., editors. American Psychological Association; 2012. Thematic analysis; pp. 57–71.https://search.proquest.com/docview/154756815918 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Browne T., McPherson L., Retzloff S., et al. Improving access to kidney transplantation: perspectives from dialysis and transplant staff in the southeastern United States. Kidney Med. 2021;3(5):799–807.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2021.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cervantes L., Richardson S., Raghavan R., et al. Clinicians’ perspectives on providing emergency-only hemodialysis to undocumented immigrants: a qualitative study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(2):78–86. doi: 10.7326/M18-0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen J.I., Hercz D., Barba L.M., et al. Association of citizenship status with kidney transplantation in Medicaid patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(2):182–190. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cervantes L., Carr A.L., Welles C.C., et al. The experience of primary caregivers of undocumented immigrants with end-stage kidney disease that rely on emergency-only hemodialysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(8):2389–2397. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05696-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lederer S., Fischer M.J., Gordon H.S., Wadhwa A., Popli S., Gordon E.J. Barriers to effective communication between veterans with chronic kidney disease and their healthcare providers. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8(6):766–771. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfv079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lockwood M.B., Saunders M.R., Nass R., et al. Patient-reported barriers to the prekidney transplant evaluation in an at-risk population in the United States. Prog Transplant. 2017;27(2):131–138. doi: 10.1177/1526924817699957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harding J.L., Perez A., Patzer R.E. Nonmedical barriers to early steps in kidney transplantation among underrepresented groups in the United States. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2021;26(5):501–507. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis A.L., Stabler K.A., Welch J.L. Perceived informational needs, problems, or concerns among patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Nurs J. 2010;37(2):143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cervantes L., Rizzolo K., Carr A.L., et al. Social and cultural challenges in caring for latinx individuals with kidney failure in urban settings. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.25838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Items S1-S3.