Highlights

-

•

In 2021, Health and Human Services decreased some buprenorphine treatment barriers.

-

•

Support for the federal guidelines at the state level was unknown.

-

•

Westlaw identified 14 states and a survey identified 15 states with more restrictive regulations.

-

•

The Mainstreaming Addiction (MAT) act removed the waiver entirely in 2022.

-

•

State-level regulations could challenge the implementation of the MAT Act.

Keywords: Buprenorphine, Data waiver, Policy, Opioid use disorder treatment, Treatment barriers

Abstract

Background

In 2021, the Department of Health and Human Services released guidelines allowing waiver-eligible providers seeking to treat up to 30 patients to be exempt from waiver training (WT) and the counseling and other ancillary services (CAS) attestation. This study evaluates if states and the District of Columbia had more restrictive policies preventing adoption of the 2021 federal guidelines.

Methods

First, the Westlaw database was searched for buprenorphine regulations. Second, state medical, osteopathic, physician assistant, nursing boards, and single state agencies (SSA) were surveyed to assess for the WT and CAS requirements and if they were discussing the 2021 guidelines. Results were recorded and compared by state and waiver-eligible provider types.

Results

The Westlaw search revealed seven states with regulations requiring the WT and ten states requiring CAS. Survey results showed ten state boards/SSAs required WT for at least one waiver-eligible practitioner type and eleven state boards/SSAs required CAS. In some states, the WT and CAS requirements only applied in special circumstances. Eleven states had discrepancies between the Westlaw and survey results among three waiver-eligible provider types.

Conclusions

Despite the 2021 federal change intended to increase access to buprenorphine, several states had regulations and/or provider boards and SSAs that were not supportive. Now, the Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment (MAT) Act of 2022 eliminated the federal x-waiver requirement to prescribe buprenorphine. However, these states may continue to have barriers to treatment access despite the MAT Act. Strategies to engage states with these restrictive policies are needed to improve buprenorphine treatment capacity.

1. Introduction

Globally, drug use is responsible for more than 500,000 fatalities per year, and opioids account for the majority of these deaths (World Health Organization, 2021). The United States (US) leads the world in the highest number of opioid-related deaths, followed by Scotland and Canada (Jesse et al., 2022). The US opioid epidemic continues to worsen, with preliminary data estimating >80,000 opioid overdose deaths in 2021, a 61% increase compared to 2019 (Ahmad et al., 2022). Buprenorphine is an underutilized evidence-based medication treatment for opioid use disorder (MOUD) that reduces mortality by at least 50% (Santo et al., 2021; Sordo et al., 2017; Watts et al., 2022). Fewer than 25% of individuals with OUD receive any of the three FDA-approved MOUDs: buprenorphine, methadone, and extended-release naltrexone (Larochelle et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2019), creating a massive treatment gap. There are many barriers to MOUD, and the evolving policy landscape for buprenorphine, the most commonly prescribed MOUD in the US, plays an important role (Haffajee et al., 2018; Harrison et al., 2022; Nguemeni et al., 2022; Rowe et al., 2022).

The Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000) allowed US physicians to treat up to 30 patients with buprenorphine in outpatient settings outside licensed opioid treatment programs if a DATA waiver was obtained. To obtain the waiver, physicians were required to complete eight hours of specialized training and attest to being able to refer to counseling and other ancillary services. In 2006, the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) Reauthorization Act expanded buprenorphine treatment by increasing the number of patients a physician could treat from 30 to 100 for those who met specified criteria (Office of National Drug Control Policy ONDCP, 2006). The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 (CARA) expanded waiver-eligibility to most Advanced Practice Nurses (APNs) and Physician Assistants (PAs) but required 24 hours of specialized training (Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act CARA, 2016), and a final rule (Department of Health and Human Services, 2016) issued by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) in 2016 raised the patient limit to 275. The Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) Act of 2018 (SUPPORT, 2018) further expanded waiver eligibility to include all APNs (clinical nurse specialists, certified registered nurse anesthetists, certified nurse practitioners, and certified nurse midwives). In April 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released practice guidelines (Department of Health and Human Services, 2021) attempting to further expand OUD treatment access by allowing prescribers to receive a waiver exemption to treat 30 or fewer individuals with buprenorphine, removing the waiver training requirements (hereafter referred to as WT) and the necessity to attest to the ability to refer patients to counseling and ancillary services (hereafter referred to as CAS). Prescribers applying for the waiver exemption were still required to be licensed in their state of practice, have a valid Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) registration, and submit a notification of intent to SAMHSA to receive the new 30-patient limit exempt waiver (30-E).

On December 29, 2022, the Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment (MAT) Act was passed, removing (a) the x-waiver registration requirement, (b) the requirement to adhere to patient limits for buprenorphine, (c) the special DEA “X” prescribing number, (d) the CAS requirement, and (e) WT requirement. The MAT Act, like the 2021 HHS guidelines, is intended to reduce federal policy barriers for clinicians to prescribe buprenorphine in further hopes of bringing buprenorphine treatment into mainstream medical care to narrow treatment gaps across the continuum of care (Woodruff et al., 2019; Fiscella et al., 2019). However, individual states can create regulations governing buprenorphine that are more restrictive than federal requirements, potentially counteracting federal efforts to reduce policy-level barriers (Andraka-Christou et al., 2022; Silwal et al., 2022). The impact of these state-level barriers to implementing federal guidelines is uncertain, but it is likely that they are impeding expansion access to life-saving medication. Recent research suggests that the 2021 HHS guidelines were not associated with an increased buprenorphine treatment capacity and with geographical differences (Nguyen et al., 2022; Spetz et al., 2022). The purpose of this paper is to review state regulations and statutes and identify states that continued to require WT and CAS after the 2021 HHS guidelines announcement.

This study was conducted by the policy workgroup of the HEALing (Helping to End Addiction Long-termSM) Communities Study (HCS), which is an ongoing multi-site study in four states (Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York, and Ohio) aimed at reducing opioid overdose deaths through a community-engaged intervention expanding evidence-based practices, including MOUD and buprenorphine as an option (The HEALing Communities Study Consortium, 2020). The NIH HEAL InitiativeSM policy workgroup seeks to examine and respond to policy barriers surrounding evidence-based practices to reduce opioid overdose, including the delivery of buprenorphine treatment as part of its scope.

2. Methods

The HCS policy workgroup developed a two-pronged research approach to examine if state regulations and laws required either the WT and/or the CAS for the 30-patient waiver exemption after the HHS guidelines were announced in April 2021. The first approach employed an electronic database search of Westlaw. However, recognizing that this approach would not be accessible to potential waiver-eligible providers, a second approach was developed, trying to mimic whom a provider may contact to determine if their state would allow them to prescribe buprenorphine utilizing the HHS 30-E waiver pathway. The second approach surveyed, via telephone and email, the state licensing boards of waiver-eligible provider types and Single State Agencies (SSAs). SSAs are the state government agencies that promote the coordination and delivery of substance use disorder services (SAMHSA, 2015). The study protocol was approved by Advarra Inc., the HEALing Communities Study single Institutional Board (sIRB).

2.1. Data sources

2.1.1. Westlaw

Two researchers conducted an electronic search using the Westlaw database. Westlaw is an online legal research platform that includes state and federal caselaw, regulations, statutes and court rules, and administrative materials (hereafter referred to as “regulations”). Searches were performed for regulations that apply when prescribing buprenorphine with a DATA 2000 waiver.

2.1.2. Boards and single state agencies (SSA) survey

The state agencies that oversee the various waiver-eligible provider types included state medical (allopathic) boards (n = 51), osteopathic boards (n = 14), physician assistant boards (n = 13), nursing boards (n = 51), and SSAs (n = 51). Contact information for state medical and osteopathic boards was obtained from the Federation of State Medical Boards website. Contact information for physician assistant boards/committees, state nursing boards, and SSAs were obtained from the websites of the American Academy of Physician Assistants, the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, and the SAMHSA SSA directory for Substance Abuse Services website, respectively.

2.2. Data collection procedures and outcomes

2.2.1. Westlaw

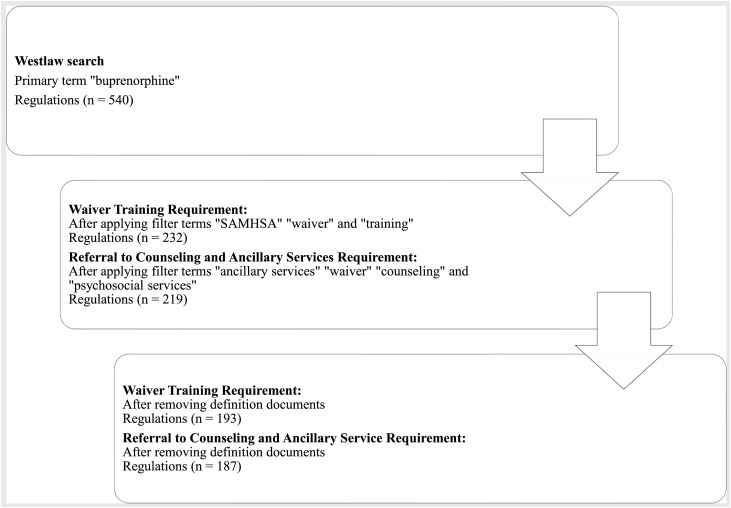

Two searches were performed using Westlaw to investigate if there were state requirements for WT, and the capacity to refer to CAS (see Fig. 1). Regulations in 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC) were identified using the main search term “buprenorphine” with subsequent terms applied specific to the HHS guidelines (85 FR 22439) exceptions (WT and CAS). The search then was narrowed by using filter terms “SAMHSA,” “training,” and “waiver” to find regulations pertinent to requirements for WT, and “ancillary services,” “waiver,” “psychosocial services,” and “counseling” to search for regulations pertinent to CAS requirements. This systematic search was conducted from February 2022 to March 2022.

Fig. 1.

Westlaw search process.

Two independent researchers individually reviewed and coded all relevant Westlaw regulations identified by the search procedure in the codebook as requiring (“yes”) or not requiring (“no”) the WT and/or the CAS for each state and DC. Researchers recorded the state name, citation including the current date of the regulation, relevant text from the regulations, and any special circumstances noted that referred to the WT and/or CAS requirement. The affected waiver-eligible provider types were recorded as (a) physicians, (b) physician assistants, and/or (c) advanced practice nurses within each regulation. If the provider type affected by each regulation was not specified due to the use of general terminology such as “practitioner,” “clinician,” or “prescriber,” researchers reviewed available definitions sections of the documents to ascertain if the provider type was specified. If provider type was not explicitly specified, the provider type recorded was based on the professional board under which the regulation was listed. For example, results were recorded as applying to physicians if the regulation was listed under or from a “Board of Medicine” or “Board of Osteopathic Medicine.” Some regulations did not specify a provider type in the text or definitions and were not housed under a specific professional board. These results were then coded as applying to all waiver-eligible provider types. If the regulation simply referred to meeting the federal requirement for prescribing buprenorphine, it was coded as following the HHS guidelines (i.e., no state requirement for WT or CAS). When results were not clear (e.g., ambiguous wording), two senior faculty reviewed to reach consensus.

2.2.2. Boards and single state agencies (SSA) survey

Medical boards, osteopathic (DO) boards, physician assistant (PA) boards/committees, nursing boards, and SSAs in 50 states and the DC were first contacted by phone, following a script that introduced the study purpose and provided background on the revised buprenorphine HHS practice guidelines. Three closed-ended questions were asked: (1) does the state board/agency currently require waiver training to prescribe buprenorphine for the 30-patient limit, (2) does the state board/agency currently require waivered providers with the 30-patient limit to have the ability/capacity to refer patients counseling or ancillary services as needed, and (3) is the state board/agency discussing the new HHS guidelines? For the first two questions, response options were “Yes,” “No,” “Do not Know,” and “Not Applicable.” If yes, respondents were asked to share a document or link to the requirement. For the third question, response options were “Yes,” “No,” “Do not Know,” “Meeting planned for discussion,” “Discussions are ongoing,” and “Decisions are made but cannot yet share.” (See Appendix A for survey script). If the phone call was not answered, a scripted voice mail was left with a phone number provided to call back. If phone calls were not returned, researchers attempted to find publicly available email addresses to email the relevant agencies. Three phone attempts and three email attempts were made. If no response was obtained after these attempts or if boards/agencies declined participation, they were coded as “no response.” No compensation was provided for survey participation. Survey data were collected between October 2021 and July 2022.

Some states provided comments in writing or by phone that were noted; these additional comments were not anticipated and were provided both when a response option was or was not chosen. When agencies responded “yes” to the first two survey questions (i.e., the WT and CAS requirements) and provided documents showing these requirements, those documents were reviewed to determine if the regulations applied in any special circumstance, such as only for specific payor types or in particular practice settings. Links to multiple regulations or regulations requiring purchase or labeled as unofficial were not reviewed. Responses were coded as "missing” when response options were not checked and no additional comments were provided.

When no response option was checked but comments were provided, the comments were reviewed and one of the response options was imputed if the comment clearly indicated an answer. Statements such as “declines to amend regulation until federal guidelines become permanent” or “requires training” were coded “yes*” with the * denoting the response was imputed. Comments such as “align with federal guidelines” or “adopted and endorsed the changes” were imputed as “no*.” Comments reporting “have no information to provide,” “refer to legal counsel for interpretation,” “refer to another agency,” or “has not made any statements” were imputed as “do not know*.” Comments such as “do not have authority,” “does not regulate,” or a combination of “no authority and refer to another agency” were coded as “not applicable*.”

2.3. Data analyses

The WT and CAS requirement results from the Westlaw search and waiver-eligible provider boards/SSAs surveys were tabulated by state and within each state, by provider type (a) physicians (including osteopathic), (b) physician assistants, and (c) advanced practice nurses. Findings that differed between the Westlaw search and survey among Medical Board, Nursing Board, and PA Boards were identified.

3. Results

3.1. Westlaw

Across the 50 states and DC, the Westlaw search yielded over 400 documents to review for possible state requirements for the WT and CAS. Table 1 details the regulations that were more restrictive than the 2021 HHS guidelines by state and provider types. Overall, 14 states required the WT and/or CAS. In some states, WT and/or CAS were required only for (a) office-based opioid treatment (OBOT) practices, (b) worker's compensation patient treatment, (c) individuals with Medicaid as the payor, and (d) substance use disorder treatment facilities. The Westlaw supplement table with the relevant text from the regulations is in Appendix B.

Table 1.

Westlaw Results of 14 States with More Stringent Waiver Training and/or counseling/Ancillary Service Requirements than HHS Guidelines.

| State | Physician | Physician Assistant | Advanced Practice Nurses | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTR | Date | CASR | Date | WTR | Date | CASR | Date | WTR | Date | CASR | Date | |

| Alabama | Yes1 | 12/2021 | Yes1 | 07/2021 | No | No | No | No | ||||

| Arkansas | No | Yes2 | 11/2021 | No | Yes2 | 11/2021 | No | Yes2 | 11/2021 | |||

| California | No | No | Yes | 2022 | No | Yes | 2022 | No | ||||

| Colorado | Yes3 | 02/2022 | No | No | No | No | No | |||||

| Indiana | No | Yes1 | 07/2021 | No | Yes1 | 07/2021 | No | Yes | 07/2021 | |||

| Kentucky | Yes | 03/2022 | No | Yes | 03/2022 | No | Yes | 03/2022 | No | |||

| Louisiana | Yes3 | 12/2021 | No | No | No | No | No | |||||

| Maine | Yes1 | 09/2021 | Yes1 | Medicaid: 07/2021; OBOT: 07/2021, 10/2021 | Yes1 | 09/2021 | Yes1,2 | Medicaid: 07/2021; OBOT: 07/2021, 10/2021 | Yes1 | 09/2021 | Yes1,2 | Medicaid: 07/2021; OBOT: 07/2021, 10/2021 |

| New Jersey | No | Yes4 | 11/2021 | No | No | No | No | |||||

| New Mexico | Yes2 | 11/2021 | Yes2 | 12/2021 | No | Yes2 | 12/2021 | Yes2 | 11/2021 | Yes2 | 12/2021 | |

| Ohio | No | Yes1 | 01/2022 | No | Yes1 | 01/2022 | No | Yes1 | 08/2021 | |||

| Vermont | No | Yes | 02/2022 | No | Yes | 02/2022 | No | Yes | 02/2022 | |||

| Virginia | No | Yes | 02/2022 | No | No | No | No | |||||

| West Virginia | No | Yes1 | 02/2022 | No | Yes1 | 02/2022 | No | Yes1 | 02/2022 | |||

WTR = Waiver Training Requirement.

CASR = counseling and Ancillary Service Requirement.

Date = Current date (MM/YYYY) of the regulation as mentioned in the Westlaw.

Note: AK, AZ, CT, DE, DC, FL, GA, HI, ID, IL, IA, KS, MD, MA, MI, MN, MS, MO, MT, NE, NV, NH, NY, NC, ND, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, WA, WI, and WY had no regulation requiring WT or CAS.

= Requirements specific to office-based opioid treatment (OBOT) practice.

= Requirements specific to Medicaid patients.

= Requirements specific to treatment of pain under worker's compensation.

= Requirements specific to substance use disorder treatment facilities.

3.2. Boards and SSA surveys

The response rate was 70.7% (36 of 51) for Medical Boards, 64.3% (9 of 14) for Osteopathic (DO) Boards, 38.5% (5 of 13) for PA Boards, 76.5% (39 of 51) for Nursing Boards, and 72.5% (37 of 51) for SSAs. Two medical boards (KY and ME), one PA board (CA), five nursing boards (AR, CA, KY, ME, and OR), and seven SSAs (GA, IN, KY, ME, MI, MS, and NE) reported requiring WT. Agency documents provided by one SSA (IN), one medical board (ME), and one nursing board (ME) showed that the WT requirement was applied only to OBOT settings (i.e., other settings, such as emergency departments and hospitals where practitioners may need to write prescriptions to accommodate follow-up outpatient appointments, were not mentioned).

One medical board (VA), three nursing boards (KY, OR, VA), and nine SSAs (AK, AR, KY, MA, MI, MS, NE, RI, TN) reported requiring CAS. Agency documents provided by one nursing board (VA) and two SSAs (AK, TN) showed that the requirement was applied in OBOT settings only. One SSA (AK) requirement for CAS applied specifically to individuals with Medicaid.

Of the respondents, only seven medical boards (AL, IA, KY, ME, OH, RI, and VT), eight nursing boards (AR, CA, KY, MD, ME, MN, OR, and WA), and fifteen SSAs (AZ, DE, KY, MD, ME, MO, NM, OK, TN, TX, RI, SC, VT, WA, and WI) responded that they had either already discussed, planned to discuss, or were currently discussing the HHS guidelines. Notably, several boards and SSAs responded 'do not know' to several questions (for details, see Table 2).

Table 2.

Waiver eligible provider boards and Single State Agencies survey responses.

| States | Boards/SSAs | Does [the agency/board] currently require waiver training to prescribe buprenorphine for the 30-patient limit? | Does [the agency/board] currently require waivered providers with the 30-patient limit to have the ability/capacity to refer patients on buprenorphine for counseling or ancillary services as needed? | Is [the agency/board] discussing the new HHS guidelines? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | Medical | No | No | Yes* |

| Nursing | Not Applicable* | Not Applicable* | No* | |

| SSA | Not Applicable* | Not Applicable* | No* | |

| AK | Medical | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | No* |

| Nursing | No response | No response | No response | |

| SSA | No | Yes1,2 | No* | |

| AZ | Medical | Not Applicable* | Not Applicable* | No* |

| Nursing | No | No | No | |

| SSA | No | No | Meeting Planned for Discussion | |

| DO | No response | No response | No response | |

| PA | No response | No response | No response | |

| AR | Medical | No | No | No |

| Nursing | Yes | No | Yes | |

| SSA | No | Yes | No | |

| CA | Medical | No* | No* | Missing |

| Nursing | Yes* | No* | Meeting Planned for Discussion* | |

| SSA | No | No | No | |

| DO | No response | No response | No response | |

| PA | Yes | No | No | |

| CO | Medical | No | No | No |

| Nursing | No response | No response | No response | |

| SSA | No response | No response | No response | |

| CT | Medical | No response | No response | No response |

| Nursing | No | No | Do not Know | |

| SSA | No* | No* | Missing | |

| PA | No response | No response | No response | |

| DE | Medical | No response | No response | No response |

| Nursing | No response | No response | No response | |

| SSA | No* | No* | Yes* | |

| DC | Medical | No response | No response | No response |

| Nursing | No response | No response | No response | |

| SSA | No response | No response | No response | |

| FL | Medical | No response | No response | No response |

| Nursing | No | No | No | |

| SSA | Do not Know* | Not Applicable | No | |

| DO | No | Not Applicable | No | |

| GA | Medical | No response | No response | No response |

| Nursing | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | |

| SSA | Yes | Not Applicable | No | |

| HI | Medical | No | No | Do not Know |

| Nursing | No | No | No | |

| SSA | No | No | No | |

| ID | Medical | No | No | No |

| Nursing | No | No | No | |

| SSA | No | No | Do not know | |

| IL | Medical | No response | No response | No response |

| Nursing | No | No | No | |

| SSA | No response | No response | No response | |

| IN | Medical | No response | No response | No response |

| Nursing | No response | No response | No response | |

| SSA | Yes1 | No | Missing | |

| PA | No response | No response | No response | |

| IA | Medical | No | No | Meeting Planned for Discussion |

| Nursing | Do not know | Do not know | Do not know | |

| SSA | Do not Know* | Do not know* | Do not know* | |

| PA | No response | No response | No response | |

| KS | Medical | No response | No response | No response |

| Nursing | No | No | No | |

| SSA | No response | No response | No response | |

| KY | Medical | Yes* | Missing | Yes* |

| Nursing | Yes | Yes | Meeting Planned for Discussion* | |

| SSA | Yes | Yes | Discussions are ongoing | |

| LA | Medical | No | No | No |

| Nursing | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | Missing | |

| SSA | Do not Know* | Do not know* | Do not know* | |

| ME | Medical | Yes1 | No | Discussions are ongoing |

| Nursing | Yes1 | No | Discussions are ongoing | |

| SSA | Yes | No | Discussions are ongoing | |

| DO | No response | No response | No response | |

| MD | Medical | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | Do not Know* |

| Nursing | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | Meeting Planned for Discussion* | |

| SSA | No | No | Yes | |

| MA | Medical | No response | No response | No response |

| Nursing | Not Applicable* | Not Applicable* | Do not Know* | |

| SSA | No | Yes | Do not know | |

| PA | No response | No response | No response | |

| MI | Medical | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | Do not Know* |

| Nursing | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | No* | |

| SSA | Yes | Yes | Do not know | |

| PA | No response | No response | No response | |

| DO | No response | No response | No response | |

| MN | Medical | No response | No response | No response |

| Nursing | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | Meeting Planned for Discussion* | |

| SSA | No | No | No | |

| MS | Medical | No response | No response | No response |

| Nursing | No response | No response | No response | |

| SSA | Yes | Yes | No | |

| MO | Medical | No response | No response | No response |

| Nursing | No | No | No | |

| SSA | No | No | Yes | |

| PA | No response | No response | No response | |

| MT | Medical | No | No | No |

| Nursing | Not Applicable | Do not Know | No | |

| SSA | No | No | No | |

| NE | Medical | No | No | No |

| Nursing | No response | No response | No response | |

| SSA | Yes | Yes | No | |

| NV | Medical | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | No |

| Nursing | Not Applicable | Do not Know | No | |

| SSA | No response | No response | No response | |

| DO | No | No | No | |

| NH | Medical | No | No | Do not Know |

| Nursing | No | No | No | |

| SSA | No response | No response | No response | |

| NJ | Medical | No response | No response | No response |

| Nursing | No response | No response | No response | |

| SSA | Not Applicable | Do not know | Do not know | |

| PA | No response | No response | No response | |

| NM | Medical | No | No | No |

| Nursing | No response | No response | No response | |

| SSA | No | No | Yes | |

| NY | Medical | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | No |

| Nursing | No response | No response | No response | |

| SSA | No | No | No | |

| NC | Medical | No | No | No |

| Nursing | No | No | No | |

| SSA | No response | No response | No response | |

| ND | Medical | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | No |

| Nursing | Not Applicable | No | No | |

| SSA | No response | No response | No response | |

| OH | Medical | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | Yes* |

| Nursing | No* | No* | Missing | |

| SSA | No response | No response | No response | |

| OK | Medical | No | No | No |

| Nursing | No | No | No | |

| SSA | Not Applicable | No | Meeting Planned for Discussion | |

| DO | No | No | No | |

| OR | Medical | No | No | No |

| Nursing | Yes | Yes | Meeting Planned for Discussion | |

| SSA | No response | No response | No response | |

| PA | Medical | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | No* |

| Nursing | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | Missing | |

| SSA | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Do not know | |

| DO | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | No* | |

| RI | Medical | No | No | Yes |

| Nursing | No* | No* | Missing | |

| SSA | Not Applicable | Yes | Discussions are ongoing | |

| PA | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | |

| SC | Medical | No response | No response | No response |

| Nursing | No* | No* | Missing | |

| SSA | No | No | Discussions are ongoing | |

| SD | Medical | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | Do not Know* |

| Nursing | No | No | No | |

| SSA | No response | No response | No response | |

| DO | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | |

| TN | Medical | Do not Know | Do not Know | Do not Know |

| Nursing | No response | No response | No response | |

| SSA | No | Yes1 | Yes | |

| PA | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | Missing | |

| DO | Do not Know | Do not Know | Do not Know | |

| TX | Medical | No | No | No |

| Nursing | No | Not Applicable | Yes | |

| SSA | No response | No response | No response | |

| PA | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | No* | |

| UT | Medical | No | No | No |

| Nursing | No | No | No | |

| SSA | No response | No response | No response | |

| DO | No | No | No | |

| PA | Do not Know* | Do not Know* | Missing | |

| VT | Medical | No | No | Meeting Planned for Discussion* |

| Nursing | No | No | No | |

| SSA | No | No | Yes | |

| DO | No | No | No | |

| VA | Medical | No | Yes | No |

| Nursing | No | Yes1 | No | |

| SSA | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | No | |

| WA | Medical | Not Applicable | No | No |

| Nursing | No | No | Yes | |

| SSA | No | No | Yes | |

| DO | No | No | No | |

| WV | Medical | No response | No response | No response |

| Nursing | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | No | |

| SSA | No response | No response | No response | |

| DO | No response | No response | No response | |

| WI | Medical | No | No | No |

| Nursing | No response | No response | No response | |

| SSA | No | No | Discussions are ongoing | |

| WY | Medical | No | No | No |

| Nursing | No | No | No | |

| SSA | No | No | No |

= Requirement applies specifically to office-based opioid treatment (OBOT) setting.

= Requirement applies specifically to Medicaid patients.

= Imputed response.

At least one of the provider boards or SSAs from 24 states provided comments when they did not check a response that allowed for the coding of an imputed answer (as noted by * in Table 2). The comments such as “not the appropriate agency” and “do not handle buprenorphine” showed ambiguity around knowing whether the boards or SSAs oversee buprenorphine practice. Some provider boards indicated that the state Department of Health or SSA was the appropriate agency that knew about the requirements. In contrast, some SSAs referred to the medical and nursing boards as authoritative bodies that could respond to survey questions. Other agencies to which study team members were referred by respondents included the Board of Pharmacy, Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, private legal counsel, or the state's Office of the Attorney General. Further, one SSA responded but did not want researchers to share their statement, whereas another SSA responded that their agency advocates are “old school,” resulting in a delay in the decision to adopt the 2021 HHS guidelines. Several boards and SSAs responded that “they were not aware of the 2021 guidelines,” “they do not have any information regarding the 2021 HHS buprenorphine guidelines and did not know whom to refer to,” and “not aware of the guidelines being discussed.” See Table 2 for individual provider boards' and SSAs' responses.

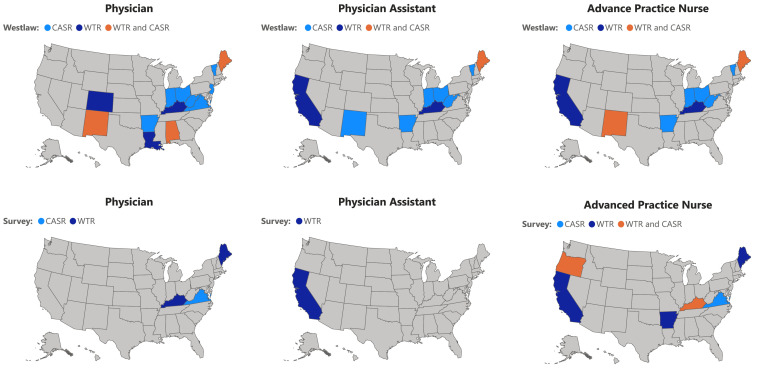

3.3. Westlaw and survey response discordant results

Discordant results between Westlaw searches and survey responses occurred in eleven states (AL, AR, CO, KY, LA, ME, NM, OH, VT, VA, and WV) and affected all three waiver-eligible provider types (i.e., physicians, PAs, and APNs.) The discrepant results between the Westlaw and survey responses are displayed in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

States with discrepancies between Westlaw and Provider Licensing Boards/Single State Agency responses on the requirements for waiver training (WT) and counseling and ancillary services (CAS).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to identify states that may have had more restrictive policies in place preventing implementation of the 2021 HHS guidelines. Boards and SSAs were contacted six months after the HHS guidelines announcement. Study results show that most state boards and SSAs aligned with federal guidelines; however, several were more restrictive, such as Kentucky, where opioid overdose mortality rates continue to increase (Slavova et al., 2021). Since these data were collected, passage of the MAT Act has removed the federal waiver requirement entirely. States not aligning with the 2021 federal guidelines may now struggle to capitalize on opportunities to increase buprenorphine treatment afforded by the MAT Act. Fifteen states did not allow at least one provider type to practice with the 30-E waiver. Notably, five of these (KY, LA, ME, OH, WV) are among the 10 states with the highest drug overdose mortality rates (CDC, 2022). Furthermore, a previous study on OBOT laws found that three of these five states imposed additional regulatory hurdles for OBOTs, such as state laws dictating the frequency of counseling and office visits with providers, and buprenorphine dosing limits (Andraka-Christou et al., 2022). State-level barriers to buprenorphine access are worrisome for public health. States with restrictive regulations may struggle to expand buprenorphine access, including at important transition points of care, such as discharge from the hospital, emergency departments, and carceral settings (Fiscella et al., 2019).

There are several potential reasons that some states may have more restrictive regulations. The comment from one SSA about being “old school” suggests that there is ongoing stigma or misinformation about OUD and buprenorphine treatment. Reducing stigma may be challenging if policymakers and leadership do not follow the research that has demonstrated that buprenorphine is an evidence-based, safe, cost-effective, and mortality reducing treatment for OUD. Other comments, such as the “board will undertake a review of the policy in coming months” and “not aware of the [2021] federal guidelines,” however, suggest that state-level regulatory barriers may be a result of limited knowledge of federal guidelines or changes in the guidelines. It is concerning that some boards and SSAs were unaware of their agency requirements or did not know to whom to refer researchers about whether they had WT and CAS requirements, given the fact that the opioid epidemic has been ongoing and worsening for more than a decade.

The study results highlight how the shared governance model of federalism across federal, state, and local levels of government is often a barrier to implementing policy change which has been a persistent issue in expanding access to OUD treatment (Andraka-Christou et al., 2022; Jackson et al., 2020). Federal regulatory policy changes are not systematically implemented at the state and local levels limiting the impacts of policy innovations at different levels of government (El-Sabawi, 2020). Thus, to label the federal policy change as a failure without taking state laws into consideration may be an oversimplification. The results further indicate the need to develop a strategic communication process and dissemination design in promoting the delivery of federal policy changes with state-level boards/SSAs that oversee substance use treatment providers, particularly those outside licensed opioid treatment program settings. Feedback on federal policy can help eliminate provider barriers in the provision of buprenorphine treatment (Haffajee et al., 2018), and research on dissemination effectiveness is needed (Purtle et al., 2017). It is also possible that improved federal-state level communication can promote compliance with federal changes and prevent and remove restrictive state regulations.

The findings suggest, too, that providers interested in obtaining the DATA 30-E waiver may have struggled to obtain information about it from their own licensing board or SSA, including whether the state would have allowed them to practice with that license. Some boards/SSAs were unaware of the HHS guidelines and suggested reaching out to private legal counsel for interpretation of the regulation, which suggest to some providers that this treatment is controversial or not a sound standard of care. Without a clear endorsement or support for the federal change, these board/SSA responses may be interpreted as disapproval of HHS guidelines and providers may choose not to prescribe buprenorphine, fearing it may put their license at risk. On the other hand, when the boards/SSAs decline to respond or are unresponsive, some providers may move forward adopting the federal change. Notably, the number of waivered clinicians increased under the 2021 guidelines (Spetz et al., 2022), but it is unclear whether those providers prescribed buprenorphine given the inconsistencies related to board/SSA guidance. The lack of support and responsiveness from state organizations (boards/SSAs) may have been a significant barrier to adopting and implementing the 2021 HHS federal policy change, and this lack of support could extend to the MAT Act. While the MAT Act removed the X-waiver and related buprenorphine-specific training requirements, the Medication Access and Training Expansion (MATE) Act that was included in the same legislative package requires all DEA registrants to complete a one-time eight-hour training on managing patients with substance use disorders. While the MATE Act is intended to expand prescriber education on treating opioid and other substance use disorders, it remains unclear if states with more restrictive policies will continue to require buprenorphine-specific training that has been eliminated at the federal level. It is possible that states could amend their buprenorphine regulations to align with the federal change and support their licensees. Alternatively, they could amend regulations to require additional hours of training and educational requirements, thereby upholding barriers for providers of buprenorphine treatment that do not exist for other DEA Schedule III controlled substances.

Further, it is concerning that some state buprenorphine regulations identified in the Westlaw legal database were inconsistent with the survey responses obtained from the boards/SSAs. Some state regulations mention the presence of WT and/or CAS requirements, while the provider boards and SSAs responded that they align with federal changes. We recommend that state boards and SSAs which have adopted the HHS guidelines to prioritize amending their state-level buprenorphine guidelines to reflect the new MAT Act changes.

This study has limitations. First, Westlaw was used as the primary database to search state regulations, and it is possible that Westlaw does not include all state-level policies pertaining to buprenorphine practice. However, prior publications have used the Westlaw database as a primary source to explore state regulations related to buprenorphine (Andraka-Christou et al., 2022). Additionally, search terms such as “partial agonist” were not used which may have led to more documents to review. There was also a poor response rate from PA boards. The study was conducted prior to the enactment of the MAT Act, and it is not known how states’ policies around buprenorphine treatment will affect MAT Act implementation.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that several states continue imposing more restrictive regulations despite the 2021 federal announcement allowing clinicians to treat up to 30 patients at any given time without completing WT or CAS requirements. Given the persistent gap in OUD treatment, particularly in settings like the emergency department, it is imperative to understand why some states persist with restrictive buprenorphine treatment policies and to address their concerns proactively. States with provider licensing boards and SSAs not adopting the 2021 HHS federal change may continue to have inadequate access to buprenorphine treatment even after the passage of the MAT Act. More than ever, buprenorphine treatment access is needed along the continuum of care, including at critical points of transitions of care (e.g., hospital discharge), to help healthcare systems reduce the high rates of untreated OUD and attempt to decrease the associated morbidity and mortality of this disease. The 2021 HHS buprenorphine practice guidelines was a promising step in addressing regulatory barriers for some new prescribers. Now, the MAT Act further removes federal policy barriers and may help reduce stigma, increase treatment accessibility, and support the integration of OUD treatment into primary care and other needed practice settings in the states whose buprenorphine policies align with the federal government. However, the states with the most restrictive regulations may restrict the implementation and expansion of buprenorphine practice even with the elimination of the waiver. This raises an important question - will these states revise or remove their buprenorphine regulations and align themselves with the MAT Act? As our work demonstrates, federal policymakers have an opportunity to evaluate their policy dissemination designs and to work with state leadership to advocate for scientific and evidence-based treatment in responding to the opioid overdose crisis, ensuring that federal policy changes are known and implemented at the state level and to thereby, ensuring equitable access to treatment across all states.

Author disclosures

Role of funding source

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health through the NIH HEAL (Helping End Addiction Long-termSM) Initiative under award numbers UM1DA049406 (University of Kentucky), UM1DA049412 (Boston Medical Center), UM1DA049415 (Columbia University), UM1DA049394 (RTI International): R01GM987654. The ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier is NCT04111939. This study protocol (MP0087) was approved by Advarra Inc., the HEALing Communities Study Single Institutional Review Board (sIRB). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the NIH HEAL InitiativeSM, or the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Contributors

M.R. Lofwall developed the idea of the study. M.R. Lofwall, J. Talbert, A. Silwal, and J.R. Kelsch led the writing of the article. A. Silwal and J. Kelsch conducted the Westlaw database search and review. A. Silwal, C. Cook, M. Gallivan, R. Bohler, S. Hatcher, and S. Williams collected the survey responses. M.R. Lofwall and J. Talbert guided, reviewed, approved the methodology and analysis, and wrote the first draft with A. Silwal. All authors reviewed, provided critical feedback, and approved the final article.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors have no conflicts to declare.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.dadr.2023.100164.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Ahmad F.B., Rossen L.M., Spencer M.R., Warner M., Sutton P. Vol. 2018. National Center for Health Statistics; 2022. (Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts). [Google Scholar]

- Andraka-Christou B., Gordon A.J., Bouskill K., Smart R., Randall-Kosich O., Golan M., Totaram R., Stein B.D. Toward a typology of office-based buprenorphine treatment laws: themes from a review of state laws. J Addict. Med. 2022;16(2):192–207. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2022. Drug overdose mortality by state. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/drug_poisoning_mortality/drug_poisoning.htm (Accessed 9/7/2022). 2022.

- Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA), Pub. L. No. 114-198, 2016. https://www.congress.gov/114/plaws/publ198/PLAW-114publ198.pdf. (Accessed 10/7/2022).

- Department of Health and Human Services Medication assisted treatment for opioid use disorders. Fed Regist. 2016;81:44712–44739. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2016-07-08/pdf/2016-16120.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services Practice guidelines for the administration of buprenorphine for treating opioid use disorder. Fed. Regist. 2021;86:22439–22440. https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2021-08961 [Google Scholar]

- El-Sabawi T. MHPAEA & marble cake: parity & the forgotten frame of federalism. Dickinson Law Rev. 2020;124:591. [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K., Wakeman S.E., Beletsky L. Buprenorphine deregulation and mainstreaming treatment for opioid use disorder: x the X Waiver. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(3):229–230. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3685. PMID: 30586140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffajee R.L., Bohnert A., Lagisetty P.A. Policy pathways to address provider workforce barriers to buprenorphine treatment. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018;54(6 Suppl 3):S230–S242. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison J.M., Kerber R., Andraka-Christou B., Sorbero M., Stein B.D. State policies and buprenorphine prescribing by nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2022 doi: 10.1177/10775587221086489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEALing Communities Study Consortium The HEALing (Helping to End Addiction Long-term SM) Communities Study: protocol for a cluster randomized trial at the community level to reduce opioid overdose deaths through implementation of an integrated set of evidence-based practices. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J.R., Harle C.A., Silverman R.D., Simon K., Menachemi N. Characterizing variability in state-level regulations governing opioid treatment programs. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2020;115 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesse C., Gumas E.D., Gunja M.Z. 2022. Too many lives lost: comparing overdose mortality rates and policy solutions across high-income countries. The CommonWealth Fund. May 19, 2022. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2022/too-many-lives-lost-comparing-overdose-mortality-rates-policy-solutions (Accessed March 21, 2023).

- Larochelle M.R., Bernson D., Land T., Stopka T.J., Wang N., Xuan Z., Bagley S.M., Liebschutz J.M., Walley A.Y. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: a cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018;169(3):137–145. doi: 10.7326/M17-3107. Aug 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguemeni Tiako M.J., Meinhofer A., Friedman A., South E.C., Epstein R.L., Meisel Z.F., Morgan J.R. Buprenorphine uptake during pregnancy following the 2017 guidelines update on prenatal opioid use disorder. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.05.041. S0002-9378(22)00392-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T., Andraka-Christou B., Arnaudo C., Bradford W.D., Simon K., Spetz J. Analysis of US county characteristics and clinicians with waivers to prescribe buprenorphine after changes in federal education requirements. JAMA Netw. Open. 2022;5(10) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.37912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) Reauthorization Act of 2006, Pub. L. No. 109-469, 2006. https://www.congress.gov/109/plaws/publ469/PLAW-109publ469.pdf. (Accessed 10/7/2022).

- Purtle J., Elizabeth A.D., Brownson R.C., Brownson R.C., Colditz G.A., Proctor E.K. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. 2nd edn. Oxford Academic; New York: 2017. Policy dissemination research. 2017; online edn. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe C.L., Ahern J., Hubbard A., Coffin P.O. Evaluating buprenorphine prescribing and opioid-related health outcomes following the expansion the buprenorphine waiver program. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2022;132 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santo T.J., Clark B., Hickman M., Grebely J., Campbell G., Sordo L., Chen A., Tran L.T., Bharat C., Padmanathan P., Cousins G., Dupouy J., Kelty E., Muga R., Nosyk B., Min J., Pavarin R., Farrell M., Degenhardt L. Association of opioid agonist treatment with all-cause mortality and specific causes of death among people with opioid dependence: a Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(9):979–993. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silwal A., Bohler R., Thomas C.P., South A., Talbert J., Fanucchi L., Lofwall M.R. New HHS guidance for increasing number of buprenorphine clinicians who can treat OUD. Hospitalist. 2022;26(6):12–13. https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/32316/clinical-guidelines/new-hhs-guidance-for-increasing-number-of-buprenorphine-providers-who-can-treat-oud/ [Google Scholar]

- Slavova S., Quesinberry D., Hargrove S., Rock P., Brancato C., Freeman P.R., Walk S.L. Trends in drug overdose mortality rates in Kentucky, 2019-2020. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4(7) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16391. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spetz J., Hailer L., Gay C., Tierney M., Schmidt L., Phoenix B., Chapman S. Changes in US clinician waivers to prescribe buprenorphine management for opioid use disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic and after relaxation of training requirements. JAMA Netw. Open. 2022;5(5) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.5996. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sordo L., Barrio G., Bravo M.J., Indave B.I., Degenhardt L., Wiessing L., Ferri M., Pastor-Barriuso R. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Funding and characteristics of single state agencies for substance abuse services and state mental health agencies, 2015. HHS Pub. No. (SMA) SMA-17-5029. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Substance Use-disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) for Patients and Communities Act, Pub. L. No. 115-271, 2018. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-115publ271/html/PLAW-115publ271.htm (Accessed 10/7/2022).

- Watts B.V., Gottlieb D.J., Riblet N.B., Gui J., Shiner B. Association of medication treatment for opioid use disorder with suicide mortality. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2022;179(4):298–304. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21070700. Apr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A.R., Nunes E.V., Bisaga A., Levin F.R., Olfson M. Development of a cascade of care for responding to the opioid epidemic. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45(1):1–10. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2018.1546862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff A.E., Tomanovich M., Beletsky L., Salisbury-Afshar E., Wakeman S., Ostrovsky A. Dismantling buprenorphine policy can provide more comprehensive addiction treatment. NAM Perspect. 2019 doi: 10.31478/201909a. Sep 9; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2021. Opioid overdose. August 4, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/opioid-overdose. Accessed March 21, 2023.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.