Abstract

This study explores the relationship between the time children spend outdoors with critical social and health factors. We use questionnaire data from the 2017–2018 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study in Iceland, focused on children in the 6th, 8th, and 10th grades. All Icelandic schools with pupils in these classes were invited to participate. The HBSC study is based on a research collaboration dating back to 1983 and is in cooperation with the WHO Regional Office for Europe (Inchley et al., 2020). Every four years the study is conducted in more than 50 countries and regions across Europe and North America. Data is collected on children’s health and well-being, social environments and health behaviours. The purpose of this paper is to better understand the social and health factors that impact children in Iceland, paying attention to the diversity of this social group, and how these factors relate to their outdoor behaviour. Our analysis focuses on children’s time spent outdoors on weekdays in relation to their parents, general health, leisure, and friendship. The findings reveal a complex picture of children’s outdoor lives. The results show that a great majority of children spend time outside mostly with friends and that children with poor relationships with other children spend considerably less time outside. Children’s outdoor lives emerge as a social activity that strongly relates to physical and mental health. Interventions to increase time spent outside might focus on this social dimension rather than simply on the extent of outside time.

Keywords: Time spent outdoors, Health and leisure, Friendship, Outdoor education, Outdoor recreations

Introduction

In this paper we explore the social and health factors that influence the time children spend outside during a weekday, both during school-hours as well as in their leisure time after school. A broad range of positive effects have been associated with spending more time outdoors, such as improved physical and mental health (Kaplan & Kaplan, 2002; Kuo et al., 2018) as well as an opportunity of deeper connections with nature and the local environment/neighbourhoods (Chawla, 2007). And yet several international studies suggest that the time children spend outdoors and what they do when outdoors, is changing and not for the better. Studying the status of children’s outdoor life in the UK more than a decade ago, Mannion, et al. (2007) reported that “the picture emerging about children and young people’s experience of and in outdoor and natural environments is concerning” (p. 14). If anything, this concern has deepened. Children are spending more time indoors, on their digital devices, and this development has raised awareness of the implications of reduced outdoor activity, including decreased mental and physical health (Coon et al., 2011; Gopinath et al., 2012). Little is known, however, about how much time contemporary Icelandic youth spend outdoors and factors that influence their outdoor activities.

The study reported on in this paper aimed to generate a better understanding of the social and health factors that impact children in Iceland as a diverse social group, and how these factors could influence their outdoor behaviour. The findings offer important insights for those working with children and concerned with issues of inclusion by raising awareness about those who are socially excluded and therefore have less access to the benefits of being outdoors.

Benefits of being outdoors

This section will clarify some advantages of being outdoors according to the literature. We look at the time that children spend outside, the value it confers, and why it is changing. Special emphasis is placed on social relationships and outdoor experiences, and we conclude the review by summarizing the main threads and highlight important questions that are discussed in the paper.

Spending time outdoors in nature and participating in activities in the natural environment can have a considerable positive impact on well-being and facilitate holistic and healthy development in both adults and children (Kaplan & Kaplan, 2002; Kuo et al., 2018), such as lower stress levels (Thompson et al., 2012), improved cognitive development of young children (Ulset et al., 2017), reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety (Beyer et al., 2014), and there is significant evidence of an inverse relationship between children’s and adolescents’ greenspace exposure and emotional and behavioural problems (Vanaken & Danckaerts, 2018). Studies have also shown that outdoor activities can improve physical health and lead to fewer physical ailments, and the acceleration of recovery time following illness (Maller et al., 2006; Sallis et al., 2000). What is more, the experience of the outdoors can also shape children’s attitudes toward ecological conservation (Chawla, 2007; Lekies et al., 2015) and support their academic achievements (Kuo et al., 2018).

Specifically for Iceland, a recent randomized controlled study (Olafsdottir et al., 2020) looked at how recreational exposure to the natural environment impacted mood and psychophysiological responses to stress. This study found that walking in nature resulted in lower cortisol levels when compared with nature viewing, and that walking in nature also improved mood more than watching nature scenes on TV or physical exercise alone.

Time spent outdoors and why it is changing

Despite the aforementioned benefits children are spending an increasing amount of time indoors. Outdoor experiences are also changing; they are more managed, supervised, and commercialized (e.g., Gill, 2007; Louv, 2005) and in Iceland preventive measures have consciously been put into place to limit unstructured and unmonitored outside hours in leisure time (Child Protection Act, No. 80, 2002; Kristjansson et al., 2020). This trend goes back a number of decades. Between 1981 and 2002, children’s play decreased by 25% in the USA, with a 50% decline in outdoor activities such as hiking and travelling in the outdoors (Hofferth, 2009). The current generation of children also plays outside less frequently and for shorter duration than their parent’s generation did (Bassett et al., 2015; Sahlberg & Doyle, 2019; Veitch et al., 2006). A longitudinal study conducted by Cleland et al. (2010) of children aged 5–6 and 10–12 revealed that time spent outdoors declined significantly among both age groups of boys and the older group of girls. Studies also show differences in time spent outdoors among different racial and ethnic groups. For example, African American children spending not as much time outdoors as Hispanic or white children (Larson et al., 2019) and minority groups not participating as often in outdoor recreation activities in national forests as white users (Parker & Green, 2016).

Academic discourses concerned with children’s outdoor lives often focus on nature, play, and recently also children’s use of screens. Researchers and practitioners (e.g., Foster & Linney, 2007; Larson et al., 2019; Rideout et al., 2010) have lamented that children spend more time indoors, particularly due to the rise of entertainment and communications media and the use of screens instead of being outdoors. Louv (2005) has claimed, “Our society is teaching young people to avoid direct experience in nature,” highlighting how this “lesson is delivered in schools, families, […] and codified into the legal and regulatory structure of many of our communities” (p. 2). Larson et al. (2011) pointed out that the most common reason for children not spending time outside was their interest in other activities such as listening to music or reading, watching TV, DVDs, or playing video games and using electronic media. The rapid increase in electronic media has been recognized as a significant contributor to the decline in nature-based outdoor time for young people (Loebach et al., 2021). Excessive screen time during adolescence has been linked to decreased time spent outdoors and a weaker connection to nature (Larson et al., 2019). Additionally, recreational computer use has been negatively associated with children’s outdoor time after school (Wilkie et al., 2018). According to Larson et al. (2011) less common reasons, but still important, were participation in indoor sports, limited access to outdoor recreation locations, lack of transportation and safety concerns. Other reasons for children not being outside included weather-related issues and a lack of time because of homework or school/other commitments. Related research by Cleland et al. (2010) examined the patterns that predict children’s time outdoors via a five-year longitudinal study. Their findings indicated that individual indoor and outdoor tendencies and social factors such as social opportunities, parental encouragement, and parental supervision predicted children’s time outdoors. Restrictions due to COVID-19 have most likely influenced how much time people of all ages spent outside, what they did and the social interactions between them. Restrictions in Iceland during COVID-19 took notice of the broad positive health benefits of being outside and allowed people to enjoy outdoor recreation but encourage people to keep physical distancing.

Social relationships and outdoor experiences

In a literature review Kuo et al. (2018) sought to answer the question of whether experiences with nature promoted learning. One of their key findings was that “natural settings seem to foster warmer, more cooperative relations between people” (p. 5). These settings have also been shown to give children more freedom to connect with one another and form ties than would typically not be the case in the traditional classroom (Maynard et al., 2013). Indeed, “research suggests that outdoor activities enable people to engage physically, intellectually, emotionally and spiritually with other people within outdoor environments” (Carpenter & Harper, 2015, p. 59).

Learning in greener settings has been shown to facilitate the development of meaningful and trusting friendships between peers, bridging both socio-cultural differences and interpersonal barriers (Chawla et al., 2014; Warber et al., 2015; White, 2012). This can affect how the group functions indoors in the classroom (White, 2012; Murphy, 2004) refers to a “socio-ecological approach to health” which acknowledges the complex interactions between people and their physical and social environments, and the effects that “infrastructure and systems can exert on these interactions, particularly with respect to social and health outcomes” (p. 165).

Fraser (2004) simplifies Bronfenbrenner’s (1986) ecological model and highlights key outdoor activities and protective factors for overall health. The domains are individual context, community and natural environmental context and social context that includes significant others, family, or friends. Regardless of whether we refer to organized or guided outdoor activities or free play, these experiences all involve relational factors, both social and ecological. School playtime has been connected with children’s opportunity to develop friendships which are in turn relevant to their well-being and sense of social identity (Gibson et al., 2011; Cleland et al., 2010) have shown that younger boys who have had more social opportunities, such as playing outside with friends, siblings or pets, spent significantly greater time outdoors than those who did not have these opportunities.

In summary, research clearly indicates that spending time outdoor, especially in nature, has many positive impacts on a broad a spectrum of well-being. Research, cited above, has also shown that children are spending less time outside than before. This change is complex and manifests differently for different groups and the factors driving it are diverse, e.g., increased indoor activities and facilities, technological- and social changes, young people’s social relationships and new hobbies. The purpose of this paper is to better understand the social and health factors that impact children in Iceland, paying attention to the diversity of this social group, and how these factors relate to their outdoor behaviour. We do this by asking questions about how much time children in grades 6, 8 and 10 spent outside on weekdays and weekends and with whom they were. The HBCS data gives us unique opportunity to analyse this outdoor behaviour with a broad spectrum of social and health-related issues and discern patterns that can enhance our understanding of this development and perhaps suggest relevant interventions.

Method

Participants

The study was based on self-reported data extracted from the Icelandic part of the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study (Inchley et al., 2020), a World Health Organization collaborative cross-national survey, which was conducted in 2018 by the Educational Research Institute in Iceland. All pupils in schools with grades 6, 8 and 10 (ages 12, 14 and 16) in Iceland were invited to participate and answer standardized questionnaires, between January and May 2018. Not all schools in Iceland took part, but the responses received were evenly distributed around the country and covered a wide range of schools. Of around 13,200 children in all schools in Iceland, 6,717 children answered the questions on outdoor life, yielding a response of 51% of the Icelandic cohort. Answers from 3,369 girls (50.2%) and 3,348 boys (49.8%) were analysed. A similar number of children answered in each grade, with an equal distribution of gender and habitation.

Procedure and materials

The 2017–2018 Icelandic online questionnaire contained four questions about children’s outdoor life; three of which are analysed in the current paper. We aimed to ask simple questions about how much time children spent outside. The questions were: (1) When you recall the last two weekdays, how much time did you spend outside? (Yesterday and Two days ago), (2) When you recall last weekend, how much time did you spend outside? (Saturday and Sunday), (3) When I am outside, I am mostly with … (It was possible to mark one to three items on a list of the seven options: On my own - With parents - With someone else from our family (siblings, grandparents, etc.) - With friends - With a sport club, scouts or other association - With my dog - I spent little time outside).

Independent and background variables

In our analysis of the time the children who responded spent outside, we primarily focused on children’s outdoor time during weekdays, which in the context of this survey were likely school days. Gender and age were tested as effect modifiers because previous work has suggested that there is a difference between males and females regarding their active hours outside (Klinker et al., 2014). We examined the following variables: parents’ financial status, country of birth, children and parents’ relationship, general health, physical exercise, participation in sport and leisure, loneliness, sadness and anxiety, friendship, social media and bullying.

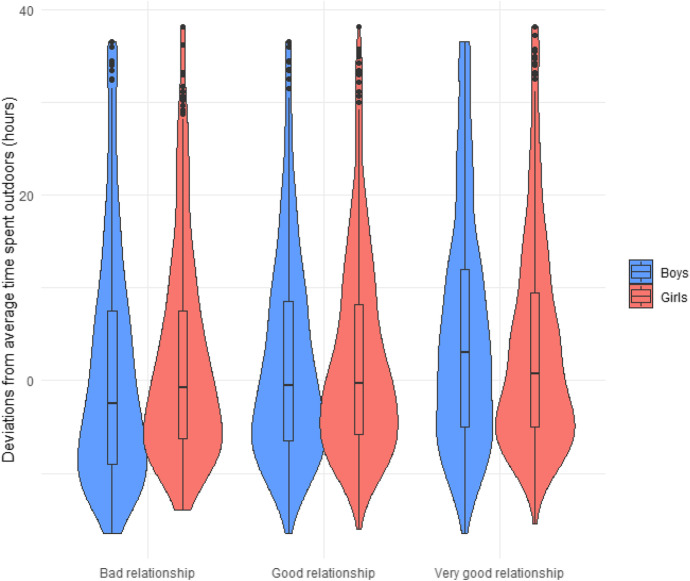

Statistical analysis

We used IBM SPSS statistics software in the descriptive analyses, using correlation to profile the full samples and cross tables. Many of the variables analysed used Likert-type questions, and sometimes, these were combined to construct Likert scales. Given the large number of data points, we used Pearson correlation (Boone & Boone, 2012) but ensured that Spearman’s rho or Kendall’s tau would also reach the same significance level (Murray, 2013), as it is debatable which is the most appropriate test to analyse this type of data (Carifio & Perla, 2008; Sullivan & Artino, 2013). To obtain a better grasp of the distributions, we present some of the data using the violin plots (Hintze and Nelson, 1998) to describe the connection between time spent outdoors and relationships with friends. Violin plots are good for presenting density (the width of the violin plot signifies higher density) and compare groups (Marmolejo-Ramos & Matsunaga, 2009). Given the high number of data points, we observe that the relations may be evident and highly significant, even though the correlation coefficients are not high.

The Icelandic HBSC study has been formally approved and fulfils ethical standards. The data were collected anonymously, and the data collection was reported to the Icelandic Data Protection Authority (No. S6463).

Findings and discussion

Our aim was to provide a better understanding of children as a diverse group with varying interests, feelings and participatory activities and explore how these might relate to their outdoor behaviour. Even if we sometimes might speculate about causal relationships, we emphasize that all we currently have are the simple correlations between variables. Nevertheless, we are sure that the factors we have identified are of importance and the discussion raises awareness about their significance and calls specifically for more research that will help us to appreciate and enhance the children’s outdoor life. The HBCS questionnaire covered a broad spectrum of social and health-related issues. In this paper we categorised factors related to Icelandic youths’ outdoor behaviour under four headings: general information, parents, health and leisure, and friendship.

General information

On average, 20% of children reported being outside 30 min or less on weekdays as the three columns to the far left in Fig. 1 shows. Of those who spend less than 30 min outdoors on weekdays close to half, or 8.9% of the overall total, of children in grades 6, 8 and 10 report not being outside at all. Time spent outside on weekdays is similar in grades 6, 8 and 10 (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Time children in grades 6, 8 and 10 spent outdoors on weekdays

The HBSC data, from the 2013/2014 study in Canada (Piccininni et al., 2018) showed exactly the same percentage of children reporting spending all of their time indoors: “A small portion (8.9%) of participants reported no outdoor play” (p. 107). Although the percentage is the same in both countries it is important to keep in mind that the Canadian study looks at outdoors after-school play and thus has a narrower focus than the Icelandic study which examines outdoor activities over a whole day. However, we disagree with our Canadian colleagues in seeing this as “a small portion” (p. 179). On the contrary, we think this figure is high, considering the wealth of research on the positive aspects of spending time outside. Given the various benefits of spending time outside we reported earlier in the paper (Kuo et al., 2018; Vanaken & Danckaerts, 2018) this number is of serious concern.

The picture of children’s outdoor life is significantly more complex than these categories indicate. We report and discuss three issues related to time spent outdoors, parents, health and leisure, and friendship.

Parents’ financial status, country of birth and connections

In Table 1, we describe the relationship between being outdoors on weekdays with three variables that indicate the financial status of the children’s parents, the closeness of the connection the children had with their parents and parent’s country of birth.

Table 1.

Correlation matrix between parents related variables and time children spend outside on weekdays

| Question | Correlation: Pearson r Being outdoors on weekdays |

|---|---|

| How well off do you think your family is? | 0.080** |

| Young adolescents perceived connection with their parents - composite variable | 0.085** |

| One or both parents born in Iceland vs. abroad - composite variable | − 0.030* |

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

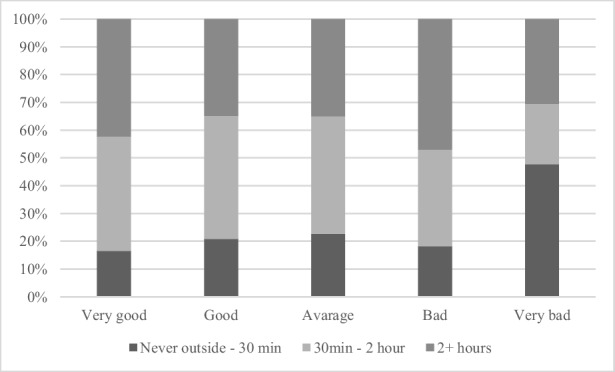

The relationship between being outdoors and the three variables shows that some parts of the family environment is important but being of Icelandic descent is only marginally so. The financial aspect is highlighted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Children’s time spent outside and five categories showing how well off they think their family is

Figure 2 reveals different outdoor profiles between the group of children that thinks their family does very badly financially (n = 23) and the other groups. There is an alarming rate of 48% report being outside for 30 min or less.

Our parents have without a doubt, a major influence in most aspects of our lives, also apparently on the time children spent outside. This finding is in line with Cleland et al. (2010) findings that parental encouragement and parental supervision predicted children’s time outdoors. That, on the other hand, does not seem to be the case with respect to children’s relationships with school (mainly with teachers). We find it worrying that close to half of the group of children that spend no time or less than 30 min outside on weekdays, think their parent’s financial status is very bad. While this group is a small sample, we are compelled to find out more about the situation. Especially if they likely not to enjoy the benefits of being outdoors that Kuo, Barnes and Jordan (2019) and many other researchers have addressed (e.g. Kuo et al., 2018; Lekies et al., 2015; Ulset et al., 2017; Vanaken & Danckaerts, 2018). Schools and organized leisure activities have, among other things, the role of contributing to social equity. It is certainly worth probing if this group would benefit from encouragement or some strategic effort that might draw them outside. Expenses, such as for warm clothes or equipment, should not exclude children from outdoor recreation, outdoor learning, going to camps, or participating in whatever activity that takes children outdoors. A parent’s country of birth is not a strong factor in how much time children spend outdoors but needs to be considered. Þorsteinsson (2018) showed in a study on children attending an outdoor camp in Iceland, that children of foreign origin were less likely to participate than those of Icelandic descent. The study emphasized that cost and cultural barriers must not prevent students from having the opportunity to participate in such an experience.

Health and leisure

In Table 2, variables are presented that have something to to with health and activities such as general health, exercise, leisure activities, loneliness, sadness, and nervousness.

Table 2.

Correlation (Pearson r) between chosen health variables and time children spend outside on weekdays

| Question | Correlation: Pearson r Being outdoors on weekdays |

|---|---|

| Would you say your health is good? | 0.158** |

| Over the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 min per day? | 0.290** |

|

In your leisure time, do you do any of these organized activities? Organized activities refer to those activities that are done in a sport or another club or organization. Organized team sports (e.g. football, handball, basketball) |

0.164** |

|

In your leisure time, do you do any of these organized activities? Organized activities refer to those activities that are done in a sport or another club or organization. Organized individual sports (e.g. skiing, swimming, badminton, gymnastic, golf, horse-riding, martial arts) |

0.093** |

|

In your leisure time, do you do any of these organized activities? Organized activities refer to those activities that are done in a sport or another club or organization. Youth centres or after-school clubs |

0.094** |

|

In the last 6 months: how often have you had the following…? Feeling low |

− 0.086** |

|

In the last 6 months: how often have you had the following…? Feeling nervous |

− 0.060** |

| Do you ever feel lonely? | − 0.107** |

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

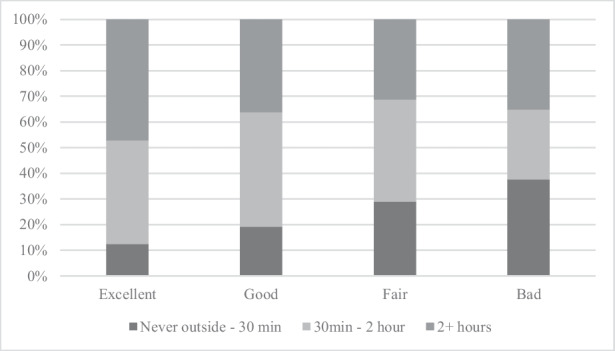

The top item shows a clear relationship with physical health. This relationship is further clarified in Fig. 3, where the pattern indicates a linear relationship between regularity in the relationship between going outside and their general health. It also implies that physical activity is involved; specifically, the relationship to specific group sports activities is clear, even though it does not tell the whole story. There is a positive correlation between time spent outside on weekdays and leisure activities such as involvement in youth centres and club activities. Psychological health variables such as feeling low and lonely shows a negative correlation with time spent outside and as does being nervous, though it is less robust.

Fig. 3.

Children’s time spent outside and estimation of general heath

Our findings of the relationship between time spent outdoors and health are well in line with prior research (see e.g., Beyer et al., 2014; Kaplan & Kaplan, 2002; Kuo et al., 2018; Maller et al., 2006; Sallis et al., 2000; Thompson et al., 2012). In our research, we identify a strong relationship between time spent outdoors and with general health (r = 0,158, p < 0.01), daily exercise (r = 0,290, p < 0.01), and group sports (r = 0.164, p < 0.01). There is a similar relationship between individual sports (r = 0.093, p < 0.01) and involvement in youth centres activities (r = 0.094, p < 0.01) that could indicate that being active is important (and not just the physical part). Our finding indicates that there is a negative correlation between time spent outside on weekdays and loneliness (r = 0.107, p < 0.01), feeling low (r = 0.086, p < 0.01), and being nervous (r = 0.06, p < 0.01). This finding is important in light of self-reported symptoms of anxiety, sadness and depressed moods, which have increased significantly over time among Icelandic adolescents (Arnarsson, 2019; Ólafsdóttir et al., 2018). This robust relationship between being outdoors and the various health and leisure variables, which is also in line with previous international research, calls for a further exploration of what ingredients of the outdoor experience give rise to the harmony observed.

Friendship

We asked the children who they were with when they were outside. They could choose between the following answers: with parents, someone else from the family, friends, clubs, dog or on their own. In Fig. 4 we see how the answers are distributed by gender. For anecdotal reasons, gender difference might be expected, but the figure indicates that this does not transpire.

Fig. 4.

Who children say they are with when they are outside, by gender

A majority, or 63%, of children report being outside with their friends, roughly equal for both girls and boys. It was perhaps expected that being outside with friends would be the overwhelming responses, but interestingly, all the alternatives indicated how many other reasons are significant for being outdoors. In Table 3, there are seven variables that we link to positive or negative relationships between children.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix between chosen friendship variables and time children spend outside on weekdays

| Question | Correlation: Pearson r Being outdoors on weekdays |

|---|---|

| How often do you meet your friends after school (excluding communication online or by phone)? | 0.245** |

| How many friends do you have now? (born in Iceland or abroad) - composite variable | 0.178** |

| Adolescents perceived connection with their friends - composite variable | 0.109** |

| How often do you have online contact with friends from a larger group? | 0.160** |

| How often have you taken part in bullying another student in school in the last few months? | − 0.034** |

| How often have you been bullied in school in the last few months? | − 0.01 |

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

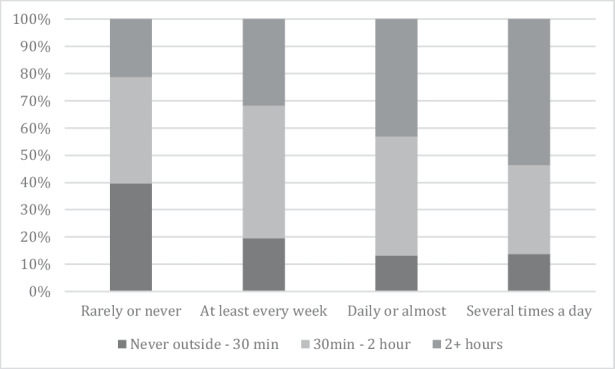

How often children meet friends after school, and how many friends they have has a strong positive correlation with time spent outside on weekdays. Figure 5 further clarifies this, where the pattern indicates a linear relationship between how often you meet your friends after school and how much you are outside on weekdays. Close to 40% of the group of children that rarely meet their friends after school are never outside, compared to 14% of the group that meets their friends almost daily or more.

Fig. 5.

How often do you meet your friends after school and how much you are outside on weekdays?

There was no question covering how much time children spent on screens or online, but one question identified children that tried over the last year to spend less time on social media, without succeeding. This question was designed to identify those who have problems with social media and can be an indicator of high screen time. There was no indication of a significant relationship between time spent on social media and time spent outdoors.

Relationships with others seem to play an important role in how much time children spend outside on weekdays. We therefore took a closer look at the variables indicating different types of relationships using violin plots to display the data. Such plots simultaneously show the typical box-plot data (based on the time spent outdoors) and the detailed density of the data along the same axis. This method of showing the data allows a visual inspection of the details of the distributions for each variable shown. The data pool enables inspection of three categories of relationships: With parents, school (mostly teachers) and friends. The strongest relationship to time spent outside is the one referring to friends and is clear significant both for boys (r = 0.176, p < 0.01) and girls (r = 0.107, p < 0.01). If a boy’s relationship with other boys was very good, they spent more time outside. Figure 6 represents the findings using a violin plot for boys and girls, each representing bad, good and very good relationships with friends, as well as the deviation from the weekly average time outdoors shown on the vertical axis in all cases. The difference in the forms is especially pronounced for boys where the means visibly increases as the friendship category improve.

Fig. 6.

Violin plot for boys (left) and girls (right) representing bad, good and very good relationships with friends, and deviation from weekly average time outdoors

The average weekly time outside is the 0 line in the figure (the mean weekly time spent outside for boys was 16.2 h and for girls it was 14.6 h) and the thick lines in the boxes in the “violins” are the median values. The bulbs show the data density at each value for the deviation from the mean time spent outside.

Deviation for the children with a very good relationship with other children is towards more time outside, and the deviation of the group with bad relationships is towards less time outside. The mean differences are also well reflected in the different distributions with the pronounced low bulb for the boys furthest to the left.

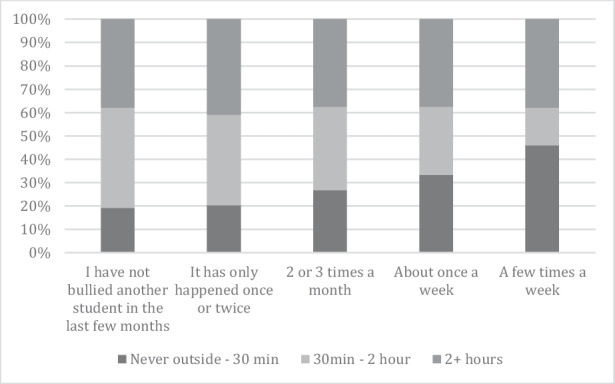

When we turn the focus to troubled relationships, like bullying, the picture is not as clear. How often have you been bullied in school in the last few months has no significant correlation with how much time children spend outside (r = 0.01). But there is a significant negative correlation between how often you have taken part in bullying another student in school in the last few months and time spent outside (r = -0.034, p < 0.01). Figure 7 illustrates incremental increases of fewer than 30 min spent outside with more bully behaviour. Close to half (46%) of the group of children that bully a few times a week (n = 37) are outside less than 30 min during the weekdays.

Fig. 7.

How often you have taken part in bullying another student in school in the last few months and time spent outside?

Nearly two-thirds (63%) of children report being outside with their friends, with no noticeable gender differences (see Fig. 4). This finding led us to investigate further the relationship between children and time spent outside, from a different perspective. We identified significant correlation between how often you meet your friends after school (r = 0.245, p < 0.01) and how many friends you have (r = 0.178, p < 0.01) with time spent outside on weekdays. Figure 5 shows close to 40% of the group of children that rarely meet friends after school are never outside. This finding can be compared to 14% of the group that meets their friends almost daily or more. The factor that shows the strongest relationship to time spent outside is the one concerning friends, especially for boys. This may be inferred from the violin plot in Fig. 6.

In modern times, online relationships matter. A variable that is an indicator of children’s social networks showed that children who often-contacted online friends were significantly more outside on weekdays (r = 0.160, p < 0,01). Answers to the question that was designed to identify those who have problems with social media (“Have you tried to spend less time on social media in the last year without success?”) could not be shown to relate to time spent outside on weekdays. Larson et al. (2011) and Larson et al. (2019) noted that the most common reasons for children not spending time outside was, among other things, their general interest in using electronic media. With social media becoming even more mobile and not hindering going out, it may even support outdoor behaviour, especially if one has a robust social network.

Our analysis sheds light on a social relationship as being a factor that seems to play an influential role in how much time children spend outside. This finding has not been widely reported in research, but we found it is in line with findings by Cleland et al. (2010), namely, that boys who have social opportunities to go outdoors with someone may spend more time outdoors. Children with no friends, or who are socially isolated, have no one to accompany them outside to their parents’ dismay. A recent study in Iceland based on interviews with parents about the outdoor life of the family (Sigurjónsdóttir, 2020) concludes that “the social factor is more important than the conditions for outdoor life in the local area” (p. 8). As a result, it is possible to argue that time spent outside has a meaningful social impact. This finding is in line with Carpenter and Harper’s (2015, p. 59) writings about the “health and well-being benefits of activities in the outdoors”. Fraser’s (2004) model of socio-ecological health and well-being domains highlights the social context of activities in the outdoors. From an educational standpoint this reflects in Wattchow et al. (2016) writings that advocates for adapting a socio-ecological philosophy and practice to education. The emphasis is on approaches rooted in the contexts of our community involving personal and social dimensions.

Could it be characteristic for many of the children who choose to spend time indoors that their relationships with others are limited or even broken and problematic? When looking at children who reported being bullied, we thought we would find that the group tended not to be outdoors. That was not the case but, interestingly, we found a significant negative correlation (r = -0.034, p < 0.01) between time spent outside and having taken part in bullying another child in school. Figure 7 illustrates an incremental increase and that 46% of the group of children that bully others a few times a week (n = 37) spend less than 30 min outside on weekdays. We do not know why this is, but this should be studied further because research shows many other adverse effects on those who bully, e.g., substance use, self-harm, and suicidal thoughts (Gower & Borowsky, 2013). Bullies have more depression and anxiety (Weng et al., 2017). This is troubling, because greener settings are tied to the development of meaningful and trusting friendships between peers (Chawla et al., 2014; Warber et al., 2015; White, 2012). Moreover, learning in greener settings has been regularly linked to the bridging of both socio-cultural differences and interpersonal barriers (Cooley et al., 2014; Warber et al., 2015). Playing outdoors is a good training ground for peer-to-peer relationships and serves to prevent bullying perpetration.

Conclusion

Children in Iceland devote on average significant time outside, but the nature of children’s outdoor life is complex. We identify that on average 20% of children reported in 2017–2018 being outside for 30 min or less on weekdays and close to half of that group (8.9%) reports being not outside at all during the whole day. These are high numbers. The parental factor is clearly influential and children’s health and active behaviour in leisure life are variables associated with outdoor life. Marginal groups are of interest to us. We find it worrying that close to half of the group of children that estimate their parent’s financial status is very bad spend no time or less than 30 min outside on weekdays. This group is small in Iceland, but we are compelled to learn more about the situation here.

We clearly identify a significant relationship between time spent outdoors and general health. A similar relationship is between individual sports and involvement in youth centres and club activities and that could indicate that being active is important and not just the physical part. After analysing three categories of relationships (with parents, teachers, and friends) the strongest association to time spent outdoors is the one referring to friends, and this aspect applies more frequently to boys. Close to 40% of the group of children that rarely meet their friends after school are never outside, compared to 14% of the group that meets their friends almost daily or more. Having a strong social network on social media is associated with outdoor behaviour. The results indicate that children’s relationships with other children, their social connections, should be better recognized.

We interpret the results as supporting the view that children’s outdoor life should be viewed as a social activity and as a relationship with other children as it fosters relationships with the environment. This finding is in line with the view that natural settings appear to foster more cooperative and warmer relations between people, and our findings indicate that friendship is related to how much time children spend outdoors. Time spent outdoors has, therefore, the potential to transform the social relationships of children and act as a training ground for peer-to-peer relationship. This finding possibly also highlights the opposite, that those children that have weaker social connections spend less time outdoors. From this perspective, intervention to increase the time children spend outside might, therefore, focus on children as a group, or a part of a group, and encourage them to go out to play and socialize. Sometimes the message from the society is the other way around and the aim is to decrease the number of unstructured and unmonitored leisure time hours outside as a prevention (Child Protection Act, No. 80, 2002; Kristjansson et al., 2020). Groups of children outside are seen as indicating an “undesirable group formation” or even “bad company”. Larson et al. (2011) suggested ways to encourage more teenagers to spend time outside with outdoor activity settings that promote peer interaction and social networking. To play outside can been seen as a training ground for formation of peer-to-peer relationship and heavy constraints from parents and society could possible hinder positive social development.

This study throws a light on the pre-COVID situation and offers a platform for a further study when a new data set is available post-COVID. A more thorough investigation of where children go outside, what they are doing there, and their relationship with their peers, is needed. Thus, we conclude by calling for a much better understanding of the complex social aspect of the outdoors experience. In particular, we need to know more about what children are doing, what is the essence of their outdoor experience, in which company they spend their time, and how this company develops and indeed much more, from several perspectives, about where and how they spend their precious time.

Acknowledgements

We warmly thank the members of the international and national HBSC team (the Icelandic director of the 2017-18 HBSC is Dr. Ársæll Arnarsson, professor at the School of Education - University of Iceland). The survey was carried out by the Educational Research Institute in Iceland.

Biographies

Jakob Frímann Thorsteinsson

is an adjunct in Leisure Studies and PhD student at the School of Education. He completed a B.Ed. degree in Teaching in 1993 and a MA in Teaching and Learning Studies with an emphasis on Outdoor Education in 2011. His research is in the field of outdoor education, outdoor recreation and leisure pedagogy (corresponding author).

Ársæll Arnarsson

is a professor of leisure studies at the University of Iceland School of Education. He completed a BA degree in psychology in 1993, an MSc degree in Health Sciences in 1997 and a PhD in Biomedical Sciences in 2009 from the University of Iceland. For the past decade, his research has focused on the health and well-being of adolescents.

Jón Torfi Jónasson

is a professor emeritus of the School of Education, University of Iceland. He has written on all levels of education in Iceland (i.e. pre-primary, compulsory, and upper secondary, with emphasis on both the vocational and academic sectors, on tertiary education and adult education). His emphasis has been on the development of the educational system, both in qualitative and quantitative terms, recently with increased focus on the future of education. See: http://uni.hi.is/jtj/en/.

Funding

Icelandic Directorate of Health and the University of Iceland Research Fund.

Data Availability

The data is available from the authors.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Arnarsson Á. Depurð meðal skólabarna á Íslandi (sadness amongst school-children in Iceland) Netla - Veftímarit um uppeldi og menntun. 2019 doi: 10.24270/serritnetla.2019.30. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett DR, John D, Conger SA, Fitzhugh EC, Coe DP. Trends in physical activity and sedentary behaviors of United States youth. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2015;12(8):1102–1111. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2014-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer KM, Kaltenbach A, Szabo A, Bogar S, Nieto FJ, Malecki KM. Exposure to neighborhood green space and mental health: Evidence from the survey of the health of Wisconsin. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014;11(3):3453–3472. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110303453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone HN, Boone DA. Analyzing likert data. Journal of Extension. 2012;50(2):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22, 723–742.

- Carifio J, Perla R. Resolving the 50-year debate around using and misusing likert scales. Medical Education. 2008;42(12):1150–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, C., & Harper, N. (2015). Health and wellbeing benefits of activities in the outdoors. In B. Humberstone, H. Prince, & K. A. Henderson (Eds.), International handbook of outdoor studies (pp. 59–68). Routledge.

- Chawla L. Childhood experiences associated with care for the natural world: A theoretical framework for empirical results. Children Youth and Environments. 2007;17(4):144–170. doi: 10.7721/chilyoutenvi.17.issue-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, L., Keena, K., Pevec, I., & Stanley, E. (2014). Green schoolyards as havens from stress and resources for resilience in childhood and adolescence. Health & Place,28, 1–13. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Child Protection Act. No. 80. (2002).https://www.government.is/media/velferdarraduneyti-media/media/acrobat-enskar_sidur/Child-Protection-Act-as-amended-2016.pdf.Accessed 12 Jan 2023

- Cleland, V., Timperio, A., Salmon, J., Hume, C., Baur, L. A., & Crawford, D. (2010). Predictors of time spent outdoors among children: 5-year longitudinal findings. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health,64(5), 400–406. 10.1136/jech.2009.087460 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cooley SJ, Holland MJ, Cumming J, Novakovic EG, Burns VE. Introducing the use of a semi-structured video diary room to investigate students’ learning experiences during an outdoor adventure education groupwork skills course. Higher Education: The International Journal of Higher Education and Educational Planning. 2014;67(1):105–121. doi: 10.1007/s10734-013-9645-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coon J, Boddy K, Stein K, Whear R, Barton J, Depledge MH. Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental well-being than physical activity indoors? A systematic review. Environmental Science Technology. 2011;45:1761–1772. doi: 10.1021/es102947t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster, A., & Linney, G. (2007). Reconnecting Children through Outdoor Education. COEO Research Document: Executive Summary. Council of Outdoor Educators of Ontario. https://www.coeo.org/research-summary/. Accessed 12 Jan 2022

- Fraser, M. (Ed.). (2004). Risk and resilience in Childhood: An ecological perspective (2nd ed.). NASW Press.

- Gibson J, Hussain J, Holsgrove S, Adams C, Green J. Quantifying peer interactions for research and clinical use: The Manchester Inventory for Playground Observation. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2011;32(6):2458–2466. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill, T. (2007). No fear: Growing up in a risk averse society. Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

- Gopinath, B., Hardy, L. L., Baur, L. A., Burlutsky, G., & Mitchell, P. (2012). Physical activity and sedentary behaviors and health-related quality of life in adolescents. Pediatrics, 130(1), e167. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gower AL, Borowsky IW. Associations between frequency of bullying involvement and adjustment in adolescence. Academic Pediatrics. 2013;13(3):214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintze JL, Nelson RD. Violin plots: A box plot-density trace synergism. The American Statistician. 1998;52(2):181–184. [Google Scholar]

- Hofferth SL. Changes in american children’s time–1997 to 2003. Electronic International Journal of Time Use Research. 2009;6(1):26. doi: 10.13085/eijtur.6.1.26-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inchley, J., Currie, D., Budisavljevic, S., Torsheim, T., Jåstad, A., Cosma, A., & Kelly, C., Ársæll, M. A., Barnekow, V. & Weber, M. M. (2020). Spotlight on adolescent health and well-being: Findings from the 2017/18 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey in Europe and Canada. Volume 1: Key findings. World Health Organization.

- Kaplan R, Kaplan S. Adolescents and the natural environment: A time out? In: Kahn P Jr, Kellert S, editors. Children and nature: Psychological, sociocultural, and Evolutionary Investigations. MIT Press; 2002. pp. 227–258. [Google Scholar]

- Klinker CDC, Schipperijn JJ, Kerr JJ, Ersbøll AKA, Troelsen JJ. Context-specific outdoor time and physical activity among school-children across gender and age: Using accelerometers and GPS to advance methods. Frontiers in Public Health. 2014;2:20. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristjansson AL, Mann MJ, Sigfusson J, Thorisdottir IE, Allegrante JP, Sigfusdottir ID. Implementing the icelandic model for preventing adolescent substance use. Health Promotion Practice. 2020;21(1):70–79. doi: 10.1177/1524839919849033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M, Browning MHEM, Sachdeva S, Westphal L, Lee K. Might school performance grow on trees? Examining the link between “greenness” and academic achievement in urban, high-poverty schools. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018;9:1669. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M, Barnes M, Jordan C. Do experiences with nature promote learning? Converging evidence of a cause-and-effect relationship. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10:305. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson LR, Green GT, Cordell HK. Children’s time outdoors: Results and implications of the National Kids Survey. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration. 2011;29(2):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Larson LR, Szczytko R, Bowers EP, Stephens LE, Stevenson KT, Floyd MF. Outdoor time, screen time, and connection to nature: Troubling trends among rural youth? Environment and Behavior. 2019;51(8):966–991. doi: 10.1177/0013916518806686. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lekies KS, Lost G, Rode J. Urban youth’s experiences of nature: Implications for outdoor adventure education. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism. 2015;9:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jort.2015.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loebach J, Sanches M, Jaffe J, Elton-Marshall T. Paving the way for outdoor play: Examining socio-environmental barriers to community-based outdoor play. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(7):3617. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louv, R. (2005). Last child in the woods: Saving our children from nature deficit disorder. Algonquin Books.

- Maller C, Townsend M, Pryor A, Brown P, St Leger L. Healthy nature healthy people: Contact with nature as an upstream health promotion intervention for populations. Health Promotion International. 2006;21(1):45–54. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dai032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannion, G., Sankey, K., Doyle, L., & Mattu, L. (2007). Young People’s Interaction with Natural Heritage Through Outdoor Learning Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report, (ROAME No.F06AB03), 225, Scottish Natural Heritage. https://dspace.stir.ac.uk/bitstream/1893/3239/1/ReportNo225.pdf. Accessed 20 Sept 2020

- Marmolejo-Ramos F, Matsunaga M. Getting the most from your curves: Exploring and reporting data using informative graphical techniques. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology. 2009;5:40–50. doi: 10.20982/tqmp.05.2.p040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard T, Waters J, Clement C. Child-initiated learning, the outdoor environment and the “underachieving” child. Early Years. 2013;33:212–225. doi: 10.1080/09575146.2013.771152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, B. (2004). Health education and communication strategies. In H. Keleher, & B. Murphy (Eds.), Understanding health: A Determinants Approach (pp. 152–169). Oxford University Press.

- Murray J. Likert data: What to use, parametric or non-parametric? International Journal of Business and Social Science. 2013;4:11. [Google Scholar]

- Olafsdottir G, Cloke P, Schulz A, Van Dyck Z, Eysteinsson T, Thorleifsdottir B, Vögele C. Health benefits of walking in nature: A randomized controlled study under conditions of real-life stress. Environment and Behavior. 2020;52(3):248–274. doi: 10.1177/0013916518800798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ólafsdóttir J, Hrafnsdóttir S, Orjasniemi T. Depression, anxiety, and stress from substance-use disorder among family members in Iceland. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2018;35(3):165–178. doi: 10.1177/1455072518766129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SE, Green GT. A comparative study of recreation constraints to national forest use by ethnic and minority groups in north Georgia. Journal of Forestry. 2016;114:449–457. doi: 10.5849/jof.13-079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piccininni C, Michaelson V, Janssen I, Pickett W. Outdoor play and nature connectedness as potential correlates of internalized mental health symptoms among canadian adolescents. Preventive Medicine. 2018;112:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Þorsteinsson, J. F. (2018). Reynsla af þróunarverkefni í skólabúðunum á Úlfljótsvatni árið 2017. Rannsóknarstofa í tómstundafræði. (Experience of a Development project in the School camp at Úlfljótsvatn Scout Centre in 2017).

- Rideout, V. J., Foehr, U. G., & Roberts, D. F. (2010). Generation M2: Media in the lives of 8- to 18-Year-Olds. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED527859.pdf. Accessed 4 Oct 2021

- Sahlberg, P., & Doyle, W. (2019). Let the children play: How more play will save our schools and help children thrive. Oxford University Press.

- Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Taylor WC. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2000;32(5):963–975. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200005000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurjónsdóttir, B. (2020). Gildi og vægi útiveru í lífi foreldra og barna á Höfuðborgarsvæðinu (Unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Iceland).

- Sullivan GM, Artino AR., Jr Analyzing and interpreting data from Likert-type scales. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2013;5(4):541. doi: 10.4300/JGME-5-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CW, Roe J, Aspinall P, Mitchell R, Clow A, Miller D. More green space is linked to less stress in deprived communities: Evidence from salivary cortisol patterns. Landscape Urban Planning. 2012;105:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ulset V, Vitaro F, Brendgen M, Bekkhus M, Borge AI. Time spent outdoors during preschool: Links with children’s cognitive and behavioral development. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2017;52:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vanaken GJ, Danckaerts M. Impact of green space exposure on children’s and adolescents’ mental health: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018;15(12):2668. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15122668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veitch J, Bagley S, Ball K, Salmon J. Where do children usually play? A qualitative study of parents’ perceptions of influences on children’s active free-play. Health & place. 2006;12(4):383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.02.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warber, S. L., DeHurdy, A. A., Bialko, M. F., Marselle, M. R., & Irvine, K. N. (2015). Addressing “nature-deficit disorder”: A mixed methods pilot study of young adults attending a wilderness camp. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 1–13. 10.1155/2015/651827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wattchow, B., Jeanes, R., Alfrey, L., Brown, T., Cutter-Mackenzie, A., & O’Connor, J. (2016). Socioecological Educator. Springer.

- Weng X, Chui WH, Liu L. Bullying behaviors among macanese adolescents—association with psychosocial variables. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017;14(8):887. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14080887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R. A sociocultural investigation of the efficacy of outdoor education to improve learner engagement. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties. 2012;17(1):13–23. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2012.652422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie HJ, Standage M, Gillison FB, Cumming SP, Katzmarzyk PT. The home electronic media environment and parental safety concerns: Relationships with outdoor time after school and over the weekend among 9–11 year old children. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):456. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5382-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data is available from the authors.