Abstract

Phthalates are endocrine-disrupting chemicals that influence endogenous hormones. Few studies have examined the link between phthalates and menopause. A recent secondary analysis revealed that phthalates were associated with self-reported sleep measures in perimenopausal women. However, the associations between phthalate exposure and additional measures of sleep remain unknown. We recruited a population of 27 midlife women (aged 45–54) to study the relationship between phthalate exposure and both subjective and objective measures of sleep. Preliminary results indicate that women with higher phthalate exposure have reduced sleep quality, more frequent sleep disruptions, and more restless sleep compared to women with lower exposure.

Keywords: Phthalates, Endocrine-disrupting chemicals, Sleep, Menopause

1. Introduction

Perimenopausal women often experience impaired sleep. Hormone changes are one commonly studied risk factor for poor sleep in midlife women. However, exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs), including phthalates could also play a role [1]. Phthalates are industrial plasticizers used in consumer products, including building materials, medical plastics, and personal care products (PCP). The relationship between phthalate exposure and sleep, including subjectively and objectively measured sleep, remains understudied.

2. Methods

This study sought to identify associations between phthalates and subjective and objective sleep in midlife women. For subjective sleep, participants completed the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and three survey questions. From the PSQI, we determined the summary score, self-reported sleep quality, sleep efficiency (time asleep relative to time in bed), sleep onset latency, number of times per month with ≥30 min sleep onset latency, total sleep duration, and number of sleep disturbances per month. From the ESS, we estimated daytime sleepiness. The frequency of sleep disturbances, insomnia, and severity of restless sleep were determined using survey questions, described previously [1,2].

All ordinal subjective sleep variables were dichotomized for analysis. In the PSQI, women who reported “very good” or “good” sleep were categorized with “good” sleep. Women who reported “bad” or “very” bad sleep were categorized with “bad” sleep. For sleep efficiency, women were grouped by ≥85% or <85%. Sleep onset latency was categorized as <15 min or ≥15 min. Women indicating having one or more nights in the past month with ≥30 min sleep onset latency were grouped as “1 or more”, compared to women with no events (“None”). Total sleep duration was categorized as ≥7 h or <7 h. We grouped number of sleep disturbances as either 0–9 or >9 disturbances. We categorized the overall PSQI score as either <5 or ≥5 (with ≥5 indicating poor sleep quality). For the ESS results, a score of <20 was indicated as “moderate daytime sleepiness” and a score of ≥20 was classified as “severe daytime sleepiness”. Responses to the sleep disturbances and insomnia survey questions were dichotomized into “weekly” or “less than weekly”. Responses to the restless sleep survey questions were dichotomized as “moderate/severe” or “mild/none”.

Objective sleep was determined using the ActiWatch (Philips Respironics). Women wore the ActiWatch for seven days following their clinic visit. Total sleep time, sleep onset latency, sleep efficiency, wake after sleep onset, and number of awakenings were measured. Sleep logs confirmed objective sleep measures. All objective sleep measures were maintained as continuous variables for analysis.

Phthalate metabolites and summaries of phthalate exposure were determined, as described previously [1,3]. Briefly, urine samples were analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography negative-ion electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. We quantified metabolites for diethyl phthalate (DEP), di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), dibutyl phthalate (DBP), diisobutyl phthalate (DiBP), dioctyl phthalate (DnOP), and benzyl butyl phthalate (BBzP). Additionally, we used five summary measures to quantify exposures to common mixtures of phthalates as previously described [1,3]. Phthalate metabolites were normalized to specific gravity as described [3]. The phthalate metabolites were selected to compare to previous research [1,3]. We estimated exposure to DEHP (sumDEHP), phthalates from PCP (sumPCP), phthalates from plastic sources (sumPLASTIC), phthalates with known anti-androgenic (AA) biological activity (sumAA), and all metabolites measured (sumALL).

We determined the relationship of each summary measure with each continuous sleep variable using linear regression. The relationships between phthalate measures and the binomial sleep variables were determined using logistic regression. For all comparisons, we fit unadjusted models. All models were fit using the MASS package in R version 3.6.1 (Action of the Toes) [4]. All linear regression plots and boxplots were made using ggplot2 and ggpubr packages in R version 3.6.1. No adjusted models were fit; therefore, results are considered preliminary.

3. Results

The study consists of 27 participants (Table 1). Of 27 women, 4 women did not complete survey data and were excluded from all analyses. Of the 23 that completed survey data, 6 were premenopausal, 8 were perimenopausal, and 9 were postmenopausal. The majority of women were white, educated, and made at last $50,000 a year. More than 80% had never smoked. More than 50% experienced hot flashes at night and moderate-to-severe hot flashes. The phthalate exposure differed from previous reports of midlife women [1,3], with these participants having less overall exposure.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of the study participants (n = 23).

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Menopause status | ||

| Premenopausal | 6 | 26.1 |

| Perimenopausal | 8 | 34.8 |

| Postmenopausal | 9 | 39.1 |

| Race | ||

| White | 19 | 82.6 |

| Black | 1 | 4.3 |

| Asian | 3 | 13 |

| Education | ||

| High school | 2 | 8.7 |

| College training | 11 | 47.8 |

| Postgraduate | 10 | 43.5 |

| Income | ||

| <$50,000 | 2 | 9 |

| >$50,000 | 21 | 91 |

| Hot flashes at night | ||

| No | 9 | 42.9 |

| Yes | 12 | 57.1 |

| Severity of hot flashes | ||

| Mild | 4 | 23.5 |

| Moderate to Severe | 13 | 76.5 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Nonsmoker | 20 | 87.0 |

| Former smoker | 2 | 8.7 |

| Current smoker | 1 | 4.3 |

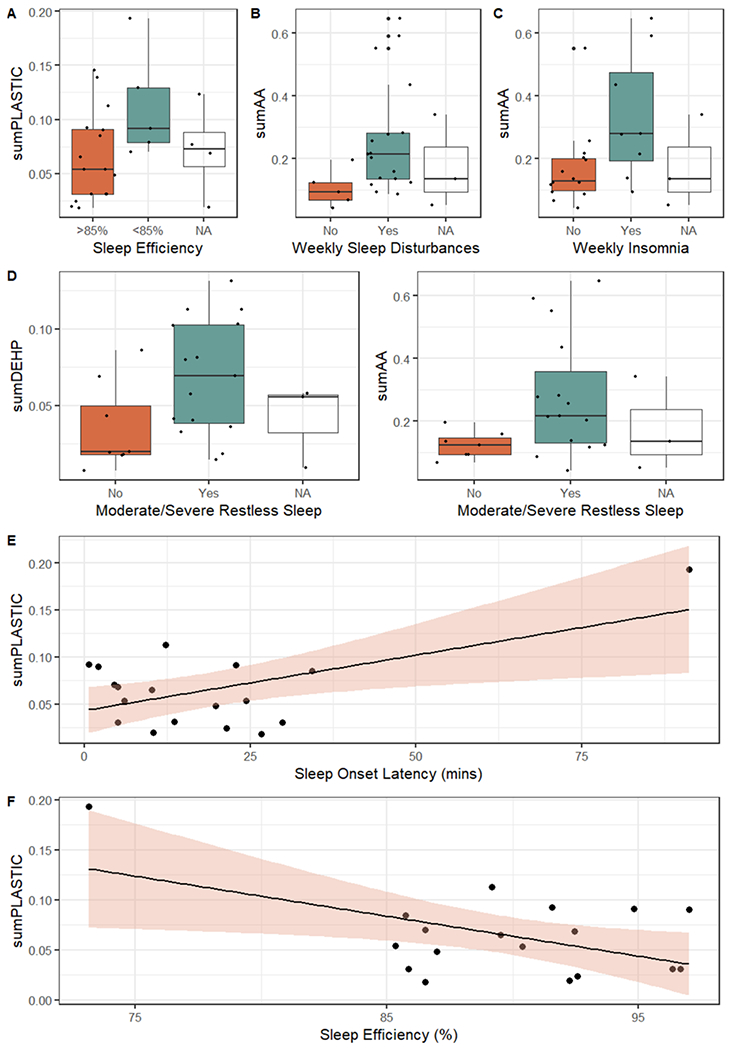

Higher phthalate summary measures were associated with worse sleep outcomes (Fig. 1). Women exposed to higher sumPLASTIC were more likely to self-report sleep efficiency below 85% (Fig. 1A). Women exposed to higher sumAA reported more frequent (i.e. weekly) sleep disturbances and insomnia (Fig. 1B and C). Similarly, women exposed to higher sumDEHP and sumAA were more likely to report moderate-to-severe restless sleep (Fig. 1D). sumPLASTIC was positively associated with sleep onset latency (Fig. 1E) and negatively associated with sleep efficiency (Fig. 1F). However, these associations may be driven by one participant. No phthalate measures were associated with other objective or subjective sleep measures.

Fig. 1.

Unadjusted associations between summary phthalate measures and subjective (A–D) or objective (E-F) measures of sleep. (A) Relationship between sum-PLASTIC and self-reported sleep efficiency from the PSQI. (B) Relationship between sumAA and weekly sleep disturbances. (C) Relationship between sumAA and weekly insomnia. (D) Relationship of SumDEHP and sumAA with moderate-to-severe restless sleep. (E) Linear relationship between sumPLASTIC and sleep onset latency (mins). (F) Linear relationship between sumPLASTIC and sleep efficiency (%). A–D) Black points are representative of individual participants, with boxplot fill color based on response to sleep variables. E–F) Black points are individual participants. Shading is representative of 95% confidence intervals. Women who did not complete sleep surveys were indicated by Not Available (NA). All associations shown were statistically significant.

4. Discussion

Overall, higher phthalates exposure was associated with worse objective and subjective sleep outcomes in midlife women. Specifically, higher exposure to sumPLASTIC was associated with decreased sleep efficiency (both self-reported and objective) and higher objective sleep onset latency compared to women with lower exposure. Women with higher exposure to sumAA self-reported more frequent sleep disturbances and insomnia and more severe restless sleep, compared to women with lower sumAA. Finally, women with higher exposure to sumDEHP reported more severe restless sleep compared with women with lower sumDEHP. There are two caveats to this preliminary study. First, some associations were likely driven by a small number of women. Second, relationships were determined via unadjusted analyses and did not consider covariates. Future studies with larger sample sizes will allow for a more thorough understanding of the relationship between phthalates and sleep.

We are among the first to identify associations between phthalate exposure and sleep in midlife women. Future studies with menopausal women must utilize both subjective and objective sleep measures, as these often differ. Such findings would illuminate risk factors associated with both subjective and objective sleep, thereby allowing more individualized therapy and interventions.

Funding

This work was funded by the Carle Illinois Collaborative Research Seed Funding Program.

Footnotes

Ethical approval

The University of Illinois Office for the Protection of Research Subjects Institutional Review Board approved the data collection before this study was completed (IRB 16CNI1250). All subjects of this study gave written informed consent.

Research data (data sharing and collaboration)

There are no linked research data sets for this paper. Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- [1].Hatcher KM, et al. , Association of phthalate exposure and endogenous hormones with self-reported sleep disruptions: results from the Midlife Women’s Health Study, Menopause 27 (11) (2020) 1251–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Smith RL, Flaws JA, Mahoney MM, Factors associated with poor sleep during menopause: results from the Midlife Women’s Health Study, Sleep Med. 45 (2018) 98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ziv-Gal A, et al. , Phthalate metabolite levels and menopausal hot flashes in midlife women, Reprod. Toxicol 60 (2016) 76–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].R Development Core Team, R: a language and environment for statistical computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austrial, 2013. [Google Scholar]