Abstract

Background:

Individuals with opioid use disorder released to communities after incarceration experience an elevated risk for overdose death. Massachusetts is the first state to mandate county jails to deliver all FDA approved medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD). The present study considered perspectives around coordination of post-release care among jail staff engaged in MOUD programs focused on coordination of care to the community.

Methods:

Focus groups and semi-structured interviews were conducted with 61 jail staff involved in implementation of MOUD programs. Interview guide development, and coding and analysis of qualitative data were guided by the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment (EPIS) framework. Deductive and inductive approaches were used for coding and themes were organized using the EPIS.

Results:

Salient themes in the inner context focused on the elements of reentry planning that influence coordination of post-release care including timing of initiation, staff knowledge about availability of MOUD in community settings, and internal collaborations. Findings on bridging factors highlighted the importance of interagency communication to follow pre-scheduled release dates and use of bridge scripts to minimize the gap in treatment during the transition. Use of navigators was an additional factor that influenced MOUD initiation and engagement in community settings. Outer context findings indicated partnerships with community providers and timely reinstatement of health insurance coverage as critical factors that influence coordination of post-release care.

Conclusions:

Coordination of MOUD post-release continuity of care requires training supporting staff in reentry planning as well as resources to enhance internal collaborations and bridging partnerships between in-jail MOUD programs and community MOUD providers. In addition, efforts to reduce systemic barriers related to unanticipated timing of release and reinstatement of health insurance coverage are needed to optimize seamless post-release care.

Keywords: Jails, Opioid use disorder, Medication for opioid use disorder, Post-release coordination of care, EPIS framework

Introduction

The weeks following release from incarceration is a critical time associated with an elevated risk for overdose and premature deaths among incarcerated individuals with opioid use disorder (Binswanger et al., 2013; Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2017; Keen et al., 2021). Medications for opioid use disorder remain underutilized in correctional settings (MOUD; e.g., methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone) (Grella et al., 2020; Scott et al., 2021) despite evidence that MOUD decreases risks for relapse, death, and recidivism (De Andrade et al., 2018; Evans et al., 2021; Green et al., 2018). Provision of MOUD in jails and prisons also increases post-release engagement in MOUD treatment when linkages to community providers are coordinated prior to release (Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2018; Martin et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2016). However, a minority of incarcerated individuals, ranging from 33% to 40%, access MOUD after release (PEW Charitable Trusts, 2020), underscoring a critical need to better understand aspects of care coordination between carceral systems and community-based MOUD providers.

Prior studies that have considered implementation of MOUD in jails and prisons identified barriers to post-release care coordination, including insufficient staffing for discharge planning, a lack of post-release linkages to community providers, limited or no health insurance coverage at the time of release, and transportation issues (Ferguson et al., 2019; Friedmann et al., 2012; Kouyoumdjian et al., 2018, Martin et al., 2019; Scott et al., 2021). A recent study of the implementation of opioid agonist treatments (methadone, buprenorphine) for OUD in correctional settings (Bandara et al., 2021) identified the unanticipated release of patients from jail as a barrier to coordinating linkages to community-based providers. The same study described the strength of partnerships with local treatment providers as a key to coordination of post-release linkages and identified intensive follow-up immediately after release and use of navigators as strategies to increase the likelihood of treatment continuity among patients (Bandara et al., 2021).

The opioid-related public health crisis continues to have a significant impact in Massachusetts (Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 2021), with incarcerated individuals at high risk for opioid- related overdose deaths following release (Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 2017). A 2018 law made Massachusetts the first state to mandate delivery of all three types of FDA-approved MOUD in five county jails; two other jails chose to participate in this pilot program (An Act for Prevention and Access to Appropriate Care and Treatment of Addiction, Chapter 208 of the Acts of 2018, 2018). A key provision of the program was for the seven jails to facilitate treatment continuity by making a post-release appointment with community-based MOUD providers upon release. This mandate only requires jail-based MOUD programs to make an appointment with local MOUD providers for their soon-to-be-released patients and does not provide detailed guidance on implementation of post-release care coordination nor the allocation of funding for the provision of these services or mechanisms to monitor them.

Documenting the barriers and facilitators of linkage to community MOUD after release from jail is necessary to inform future efforts to deliver seamless continuity of care during the critical, high-risk reentry period. We thus present findings from a qualitative study of staff engaged in implementation of in-jail MOUD treatment programs in seven Massachusetts county jails.

Methods

Conceptual framework

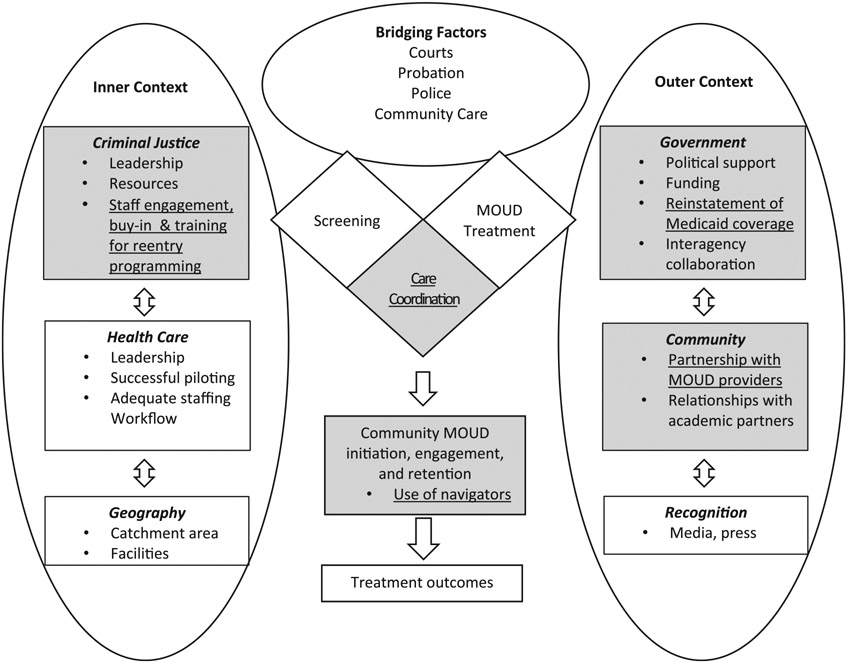

Data for the present study come from a larger study designed to understand systemic and contextual factors that facilitate and impede delivery of MOUD in jail (Evans et al., 2021). The design of the study was informed by the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment (EPIS) framework, adapted for implementation of programs within correctional settings (Ferguson et al., 2019). The contextual factors of the inner, outer, and bridging contexts within the EPIS framework were used to guide our coding and analysis process. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the inner context describes factors inside the jails that influence acceptance and feasibility of MOUD implementation (e.g., leadership and resources in criminal justice) whereas the outer context includes factors in the external environment that influence MOUD program implementation in jails (e.g., community-based MOUD treatment providers). Bridging context, in turn, includes factors that link inner and outer contexts and facilitate inter- and intra-collaborations between contexts (e.g., collaboration between jail-based MOUD program and community-based MOUD program). Prior analyses of these data have centered on implementation of the MOUD program as delivered during incarceration (Pivovarova et al., 2022). The current analysis focused on the contextual factors that facilitate and impede care coordination of post-release linkages to MOUD in the community setting (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

EPIS framework*

* Salient themes that emerged in the data are underlined in the highlighted area.

Study setting and participants

A detailed description of the qualitative research methods is provided elsewhere (Pivovarova et al., 2022). Semi-structured interviews and focus groups were conducted with 61 staff and on-site contractors within seven jails participating in a pilot project that mandated delivery of all types of FDA-approved forms of MOUD (methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone).

Participating sites present the diversity of jails in Massachusetts with respect to the size of facilities (3 large facilities with each holding more than 1000 incarcerated individuals, 2 medium facilities with each holding 501 to 1000 individuals, 2 small facilities with each holding less than 500 individuals) and urbanicity (2 urban, 4 suburban/metro, 1 rural). Purposive sampling was utilized to enroll clinical staff, security personnel, and senior administrators who were involved in MOUD implementation and/or decision-making (see Table 1 for participant characteristics).

Table 1.

Demographic information about participants.

| Female, n (%) | 37 (60.7) |

| Age1, mean (sd) | 45 (11) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 49 (80.3) |

| More than one race | 5 (8.2) |

| Missing | 4 (6.6) |

| Asian | 2 (3.3) |

| Black or African American | 1 (1.6) |

| Hispanic/Latino Ethnicity, n (%) | 3 (4.9) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 2 (3.3) |

| Some college, but no degree | 6 (9.8) |

| Associate’s degree | 6 (9.8) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 13 (21.3) |

| Master’s degree | 28 (45.9) |

| Doctoral degree or equivalent | 5 (8.2) |

| Other | 1 (1.6) |

| Job title2, n (%) | |

| Behavioral health/addiction treatment | 22 (38.6) |

| Administrative | 17 (29.8) |

| Medical | 11 (19.3) |

| Correctional | 6 (10.5) |

| Other | 1 (1.8) |

| Years working in current position3, n (%) | |

| <1 year | 15 (27.3) |

| 1-3 years | 14 (25.5) |

| 4-9 years | 18 (32.7) |

| ≥10 years | 7 (12.7) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.8) |

| Years working for your current agency3, n (%) | |

| <1 year | 7 (12.7) |

| 1-3 years | 5 (9.1) |

| 4-9 years | 20 (36.4) |

| ≥10 years | 23 (41.8) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) |

Age missing for two participants.

Roles missing for four participants.

Years in current position and jail missing for 7 participants.

Data collection

Interviews and focus groups, along with brief demographic surveys, were conducted in person at each jail between December 2019 and January 2020. Analyses for the current study focused on participants’ responses to prompts related to reentry programming and delivery of coordinated linkages to MOUD upon release.

Interviews and focus groups lasted one to two hours and were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim, and redacted to remove identifying information. Researchers reviewed each transcript for accuracy and clarity. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. The Baystate Health Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Data analysis

We employed deductive and inductive strategies for data analysis. A codebook developed for the larger study used a priori codes from the interview guide and the EPIS framework, which were subsequently refined through an iterative coding process (Pivovarova et al., 2022). Six staff members on our research team formed three dyads, coded transcripts independently and met to discuss consistency and discrepancy in coding interpretations. Discrepancies between coders in a dyad were brought to the entire team to consider varying interpretations until the entire team reached an agreement. All coded transcripts were entered into Dedoose Version 9.0.17 (SocioCultural Research Consultants, 2021). The organization of emerging patterns and salient themes in our data were guided by the EPIS framework with illustrative quotations. Our analysis is based on four codes describing the process of community reentry, barriers and facilitators to reentry, collaboration across agencies involved in reentry, and community treatment. The entire research team, including collaborators in participating jails, reviewed the results.

Results

As Fig. 1 illustrates, our data highlighted some of the components of the EPIS framework in inner context, bridging factors, and outer context, either as barriers or facilitators around coordination of MOUD continuity of care.

Inner context

Several participants noted the importance of reentry planning, which is influenced by inner contextual factors including the timing for initiation, staff knowledge about availability and accessibility to MOUD in community settings, and collaboration between MOUD and reentry teams.

Reentry planning

Reentry planning was identified as critical for achieving seamless continuity of care during the transition out of jail and the subsequent post-release phase. Participants understood reentry as a process that, besides continuity of care, involves bringing together existing support services inside jails, care coordination specific to MOUD, and post-release wrap-around services. This scope of activities was designed to achieve continuity of care, and related complexities were well-articulated by a staff member who said,

…while you’re in the institution, it’s a very controlled kind of environment… I think the real challenges are outside of these walls. There’s not one piece that is not needed in order for [the transition] to be successful – from the education and the trainings that they have here at the jail to being stable on their MOUD, to the continuum of care when they go out. [Jail 2]

As discussed below, participants elaborated on key elements of reentry planning including initiation of reentry planning, jail staff knowledge and beliefs about types of MOUD, and internal collaboration between reentry case management and MOUD teams.

Reentry planning: Initiation of reentry planning.

Timing for initiation of reentry planning varied across sites. Some jails initiated reentry planning immediately upon arrival of individuals at the facility whereas other jails waited until a few weeks prior to release. Timing of initiation for reentry planning could serve as either a facilitator or a barrier to the development of a comprehensive reentry plan:

…from first day to last day, is keeping their actual reentry in mind. That’s something that we track all the way through. So…the patient either has a case worker or a case manager from day one. [Jail 5]

Participants also noted the need to allow for enough time to complete all of the tasks involved in reentry planning:

…it takes a lot of coordinated effort…we’re working at a really limited window…what [does] housing looks like, what pharmacy they’re going to use, what clinic they’re going to use, all of these next steps, get the reentry worker on board with saying ‘can you get them to this appointment…and make sure that medical has sent over the scripts and sign them so that the reentry workers can pick them up on the day of release and that continues. [Jail 2]

In addition to timing of initiation of reentry planning, staff knowledge and beliefs about MOUD types, and availability of licensed community-based opioid treatment providers were identified as factors that influence reentry planning and facilitate post-release continuity of care.

Reentry planning: Staff knowledge about availability and accessibility to types of MOUD in community.

According to some participants, choosing buprenorphine over methadone at reentry may support MOUD treatment adherence because, “[the former] allows people who really can keep track of themselves and be following up with the doctor to not have to go to the clinic everyday necessarily, they can pick up a prescription, they can live a pretty normal life, whereas on methadone they are required for quite some time to go to the clinic every single day” (Jail 6). The availability of a clinician licensed to prescribe MOUD, and a doctor’s appointment were also highlighted as part of the wide array of considerations that could potentially influence continuation of methadone treatment upon release. One participant said,

…from a medical standpoint, Suboxone [buprenorphine] is much easier than methadone because Suboxone [buprenorphine], as long as they have somebody that can prescribe, they can get buprenorphine…The hard one is methadone because we can’t have them with a script. They have to have an appointment that day or the next day. If we can dose them in the morning, they have to have something by the next day…There’s like a lot of things that need to be thought about before we just put somebody on methadone and hope for the best that they’ll be able to get it when they get out. [Jail 2]

Jail staff knowledge about availability and accessibility to community MOUD providers helps residents make informed decisions about appropriate treatment upon release.

Reentry planning: Collaboration between MOUD and reentry teams.

Collaboration among MOUD providers and other internal teams at the HOCs varied and was perceived as having a direct impact on the extent to which the MOUD program could respond to patient needs. Along these lines, some participants identified ongoing and timely collaboration as a facilitator for coordinating a plan for MOUD continuity of care:

…[MOUD Case Manager] and I know first [about the potential release date of a patient]. We’ll communicate that to the [Behavioral Health Providers] staff either in person or via email…And they have their discharge plan…[Clinical Director] might tell me, ‘Okay, he told me he’s going to [City].’…I was like, ‘Oh, I didn’t know that. Let me look at providers in [City] to see if I can connect him there.’ It’s really a group effort of making sure he’s set up and often with pre-trial they might disclose that they’re worried that they [patient] won’t have a program to go to. [Jail 5]

Reentry planning was hindered when collaboration among jail staff was absent or limited, when roles were unclear, and when teams lacked a shared information management system. A MOUD clinician said:

It would be nice for them to be on the same page as us and to not…do repetitive work. But we don’t know who’s doing what…We run two different systems [Jail 1]

Bridging factors: Care coordination

Our data indicated that bridging factors were critical to the facilitation of inter- and intra-collaborations to the coordination of MOUD continuity of care. Salient themes of the bridging context included unanticipated timing of release, and use of bridge scripts, last dosage letters and resource lists.

Unanticipated timing of release

Unanticipated jail release was identified as a major challenge for coordination of MOUD continuity of care. For example, participants noted that accrual of “good time” can reduce sentence duration (e.g., incarcerated individuals can receive an approximate eight-day sentence deduction for engagement in an approved educational, vocational or employment training program) contributing to a shift in a patient release date:

[Making a post-release appointment] is a lot of coordination because it’s that date just because it’s end of sentence isn’t necessarily the date. You got to factor good time, if there’s anything that changed, was taken away. So that is a moving target constantly so that’s something that we, we’re trying to work on getting more staff to assist in that…. [Jail 5]

In addition, in jails with large pretrial populations there is a reduced time window to coordinate linkages with community providers, because individuals are often released directly from court. Serving these detainees was identified as the biggest challenge by one participant who noted that “you want to make sure that they have MOUD and things set up in the community, and if they go to court this afternoon and don’t come back…then we can’t do anything for them” (Jail 7).

Use of bridge scripts, last dosage letters and resource lists

Participants discussed the use of “bridge scripts” as a strategy to prevent or minimize treatment gaps among individuals who were released unexpectedly. Bridge scripts were used to provide, for example, a multi-day prescription for a specific MOUD at jail exit because that “buys them enough time to go back to their provider [after release]” (Jail 7). A participant described the use of bridge scripts as follows:

…Anybody released from court is actually getting a seven-day script for buprenorphine written and we’ll hold on to them for a week. If they don’t come back, then we shred them. The inmates and detainees are told if you are released from court, come back, and get your prescriptions, so you have them. Then we’re also informing them of bridge clinics they can go to in the community. [Jail 7]

Several participants also discussed the practice of providing a “last dosage letter” along with a list of local resources (e.g., walk-in clinics, hospitals) to both sentenced and pre-trial individuals upon release:

One of the things we have done is to give a last dosage letter, which is like a golden ticket in the MOUD community. You can bring it with you anywhere. It’s a sealed envelope, you can’t open it and you bring the sealed envelope to wherever your treatment is going to be and the nurse there opens it and it clearly and officially outlines that you were being treated at this certain facility and this is the last time you were dosed including date, time and medication level, and type. [Jail 6]

Bridging factors: MOUD initiation, engagement and retention in community settings

Use of navigators

Our data also highlighted the use of navigators(i.e., recovery coaches, reentry case managers, reentry navigators) as an important element of MOUD programming that facilitates post-release MOUD engagement and retention among patients released from incarceration. While some navigators had lived experiences with substance use and incarceration, others did not. At the time of data collection, not all jails had integrated navigators into their MOUD reentry programs. Of those that had, all participants noted the benefits of the navigators’ role in achieving post-release MOUD continuity of care. Participants understood the importance of relationship building between navigators and MOUD patients, grounded in trust and care, as a critical component that enhances the likelihood of success in post-release treatment continuity. They also noted that to create this kind of relationship, in-reach activities such as behavioral health and recovery coaching, introducing patients to community resources and services, and post-release logistical case management, should begin during the pre-release phase. The pivotal role played by navigators was eloquently explained as follows:

We start a navigation piece where we develop a relationship with them before they leave. Or maybe even right when they arrive. [MOUD Coordinator] develops a relationship…as well as our navigator who is from the area. He has lived experience. Every prison, every facility, every program should have a navigator…They [patients] can trust him…He won’t jeopardize their standing, but he cares about them. Guys [released individuals] call him, all hours of the night. And he might make an appointment, a follow up with a provider for a program participant, might drive the guy to that provider. He’s out there. He works half on the street, half in the facility. [Jail 5]

According to one participant, compared to sentenced populations, pre-trial populations are at a greater disadvantage in connecting with navigators as their stay in jail is often too short. Thus, as the following participant described, the unique context of pre-trial populations renders them further disengaged from relationship building and post-release services.

Our pre-trial population is really difficult to engage as far as reentry case support. …pretrial guys are probably more in an unstable, chaotic place in their lives, and they haven’t built up rapport that’s strong enough to continue with our reentry case workers on the outside. So, what happens is we lose them…It’s hard. They’re more of a no show and no call, even though you ask them to do those things. [Jail 2]

Such “no shows” and “no calls” can place those who are recently released at even higher risk for opioid overdoses, as the skills of the navigators are unable to be put to work.

Participants also perceived navigators as an essential source of support in reducing barriers to continued engagement in MOUD treatment after release. Their essential role is further described by one who said:

…if we left our clients to navigate this [reentry] on their own, it wouldn’t happen. Unless we facilitate that process, the likelihood that they actually take it [a bridge script to the pharmacy] and then follow up with an appointment [with a local MOUD provider], without all of us [navigators] kind of involved in that and providing support…[is] pretty rare….We have somebody that will go knock on the door…that will show up and help support this [reentry], but otherwise, it’s a complicated system and our people [residents] are often ambivalent at the time that they’re leaving anyway…whether or not they really want to do this. [Jail 2]

In summary, some participants highlighted how the support of a navigator, which ranged from helping individuals meet their basic needs to facilitating practical linkages to resources, contributed to the development of environments that were conducive to continued engagement in MOUD treatment.

Outer context

Salient themes related to outer contextual factors that influence coordination of post-release continuity of care included partnerships with community MOUD providers and reinstatement of medical health insurance.

Partnerships with community-based MOUD providers

The coordination of an appointment with a local MOUD provider and “warm” hand-offs were identified as essential components for successful linkages to care. Participants described the urgency of setting up an appointment with a community MOUD provider the day of or the day after release.

So with the sentenced folks, it’s always a warm handoff, like we’re calling whoever their intended provider is, we’re scheduling an appointment, we’re sending over whatever documentation that they need, just as if we were in the community and somebody was moving out of state…So, we try to dose them before they leave, we try to get their appointment for the very next day so that there’s no break in care. [Jail 1]

Participants shared the importance of existing partnerships, and of expanding them with community MOUD providers. As the following quote illustrates, success of connectivity between released individuals and community providers relied on efforts geared towards strengthening these partnerships:

…We have over…a hundred providers. I go by location. if I see they’re going to a town where I don’t have a provider, I start cold calling and say ‘Hey, I am [MOUD Program Coordinator] and I might be calling you again in the future. Please keep my contact information.’ [Jail 5]

Reinstatement of health insurance

In addition, several participants noted that the reinstatement of health insurance was a major challenge when attempting to make patients’ appointments with community-based MOUD providers.

And a lot of patients, I can’t make them an appointment until their insurance is active. A lot of times they [State health insurance program] won’t activate till they leave our facility. So, it’s a catch-22, trying to set them up. I can’t help them until they’re outside which is their highest risk time…I just had an individual today who is leaving [soon]. I’m trying to make him an appointment. His insurance isn’t active yet, so they won’t make an appointment for me. [Jail 5]

As the above quote illustrates, participants in our sample acknowledged the importance of timely reinstatement of health insurance coverage to avoid gaps in treatment continuity. This highlights the systemic barrier that prevents both MOUD teams in jail settings and their patients to secure seamless post-release continuity of care.

Discussion

Our findings identified several key inner, bridging and outer contextual factors that facilitate or impede MOUD care coordination for individuals released from carceral settings. We hope the lessons learned from the findings discussed below would serve as important areas of consideration for other states implementing jail-based MOUD programs.

Salient themes in inner context indicated that effective reentry planning needs to start early, incorporate staff knowledge around availability and accessibility to local MOUD providers, and be supported by collaboration between MOUD and reentry teams. Our findings are consistent with recommendations for early initiation of reentry planning, particularly for individuals with short detention stays (Osher, 2007; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, 2017; Vigne et al., 2008). The earlier the initiation of reentry planning the better will be the likelihood of having a well-coordinated reentry plan that meet the unique needs of each patient.

Jail staff knowledge about availability of, and accessibility to, MOUD providers in the communities to which patients return also influences reentry planning. These findings suggest a need for collaboration between MOUD and reentry teams to develop individualized reentry plans that incorporate strategies to reduce access barriers in community settings. Recent related research has documented how greater coordination and communication between jail staff and community-based MOUD providers are perceived by MOUD providers to increase continuity of MOUD and other healthcare after jail release (Stopka et al., in press). Consistent with a study on MOUD provision in state prison systems (Scott et al., 2021), however, our findings also speak to the uneven availability of types of MOUD treatment in certain geographical locations. Consequently, the type of MOUD a patient receives while incarcerated, and after release, is based not on his/her preference, but on what is available and accessible in the community. Hence, in addition to support for jail MOUD programming, funding to secure and broaden the scope of community MOUD treatment options is essential to responding to patients’ treatment preferences.

Salient themes from the bridging factors highlighted the importance of strategizing for unanticipated timing of release, and use of bridge scripts, last dosage letter and resource lists. In addition, the use of navigator was identified as a bridging factor essential to facilitating MOUD initiation, engagement and retention of patients in community setting. Consistent with previous research (Bandara et al., 2021), unanticipated timing of release was identified as a major barrier that curtailed the time for MOUD programs to plan and facilitate linkage to community providers, especially for pre-trial clients. In such situations, the use of a bridge script was indicated as a potentially helpful strategy to minimize the treatment gap. Indeed, at the time of data collection, several participants discussed post-release care coordination for pre-trial populations as a significant concern that requires better communication and coordination with courts. Additionally, some jails attempted to address this major barrier by starting discharge and reentry planning early. Using multiple approaches to addressing a persistent system-wide issue like unplanned releases over which the jails have limited direct control, may alleviate some of the associated problems.

Our finding on the use of navigators supports previous research findings (Bandara et al., 2021) noting that navigators are facilitators for increasing the likelihood of patients making post-release appointments with community MOUD providers. Importantly, navigators can help patients to counter misinformation and stigmatizing reactions to MOUD, which may support patient’s continued engagement with treatment after release (Brousseau et al., 2022). Our data further indicate that the use of navigators starting at the pre-release phase will help guide the critical transition period of release from incarceration to community. These findings are reflected in the ongoing demonstration project by MassHealth (Massachusetts’ Medicaid program), the Behavioral Health Supports for Justice Involved Individuals (BH-JI). The BH-JI is built on a reach in, reentry model to engage justice-involved populations with mental health and substance use conditions into services that respond to their health and social needs. Navigators play a central role by bridging the pre- and post-release coordination of care to create a seamless transition (London & Dupuis, 2021; Massachusetts Executive Office of Health and Human Services, 2022).

Our qualitative findings on the outer contextual factors highlighted the importance of partnerships between jails and community-based MOUD providers as well as the timely reinstatement of health insurance coverage. We found that establishment of MOUD linkages to post-release care is facilitated by existing partnerships between jails and local MOUD providers, and additional efforts geared towards establishing new ones. These findings support prior research (Bandara et al., 2021; Ferguson et al., 2019; Klein, 2018) highlighting the strength of partnership as key to securing coordination of post-release MOUD linkages. A limited literature on the development of partnerships between jails and community-based treatment agencies reveals the importance of building a mechanism to facilitate and maintain direct communication among staff from both agencies. In addition, identification of a shared interagency goal with input from staff across agencies on how to accomplish this shared goal is also necessary (Monico et al., 2016; Welsh et al., 2015). Findings from these studies suggest that a dialogue between jails and MOUD providers is pivotal to support a seamless coordination of care for MOUD patients in transition.

Reinstatement of health insurance coverage is another structural barrier to MOUD community coordination (Scott et al., 2021). Participants frequently noted this factor, already identified in existing literature (Ferguson et al., 2019; Scott et al., 2021). State Medicaid is not typically activated until a day prior to or the day of release into the community. Thus, MOUD programs are faced with limited time to set up an appointment with local MOUD providers. In order to minimize a gap in treatment, federal efforts are currently underway through the Medicaid Reentry Act of 2021 (2021) to furnish the Medicaid coverage to incarcerated individuals during the 30 days before their release.

Lastly, consistent with a study that found ambiguity in policies of problem-solving courts toward MOUD (Andraka-Christou et al., 2022), a key provision of the MOUD program under a 2018 law in Massachusetts does not provide a standard guideline for implementation of post-release care coordination. This policy mandate could be strengthened by consideration of best practice guidelines for reentry services and MOUD continuity of care along with dedicated funding and monitoring of these services.

Findings should be considered in light of several limitations. We collected data from staff responsible for MOUD program implementation who may have been invested in program’s success and thus unlikely to share negative responses. However, participants did report implementation challenges, which suggests a willingness to disclose derogatory information. These data, collected during early program implementation, may be less relevant as the program matures. Future work will collect data on community care coordination during later stages of MOUD program operation. Finally, we did not collect data from released individuals underscoring a topic for future research.

The study has some noteworthy strengths. Using qualitative methods, it assessed jail staff’s perspectives and experiences on challenges and facilitators encountered throughout coordination of post-release linkages to care. It recruited a broad range of stakeholder groups involved in MOUD implementation and representing seven correctional facilities at various stages of MOUD program implementation. Results provide useful insights into experiences and perspectives that can inform future adaptation of MOUD continuity of care.

These findings have implications for MOUD programs in correctional settings that seek to deliver seamless post-release care coordination. Indeed, most of the benefits of the jail-based MOUD programs may accrue after release in the community though beneficial impacts on willingness to resume MOUD (Rich et al. 2015), and important client outcomes like recurrent drug use, recidivism and social reintegration (Evans et al. 2022). These findings should inform the design and the implementation of MOUD programs in jails and continuity of care after release, emphasizing the importance of internal collaborations and bridging collaborations between jail-based MOUD programs and community opioid treatment providers.

Acknowledgments

MassJCOIN Research Group: Baystate Health, Randall Hoskinson Jr., Lizbeth Del Toro-Mejias, Elyse Bianchet, Patrick Down

Tufts University School of Medicine: Rebecca Rottapel, Allison Manco, Mary McPoland

Essex County Sheriff’s Department: Sheriff Kevin F. Coppinger. Jason Faro

Franklin County Sheriff’s Office: Sheriff Christopher J. Donelan, Edmond Hayes

Hampden County Sheriff’s Department: Sheriff Nicholas Cocchi, Martha Lyman, Ed.D

Hampshire County Sheriff’s Office: Sheriff Patrick J. Cahillane, Melinda Cady

Middlesex County Sheriff’s Office: Sheriff Peter J. Koutoujian, Kashif Siddiqi, Daniel Lee

Norfolk County Sheriff’s Office: Sheriff Jerome P. McDermott, Tara Flynn, Erika Sica

Suffolk County Sheriff’s Department: Sheriff Steven W. Tompkins, Rachelle Steinberg, Marjorie Bernadeau-Alexandre

Funding sources

This research received funding from the following sources

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) 3UG3DA044830-02S1, 1UG1DA050067-01, K23DA049953-01.

Footnotes

Ethics approval

The authors declare that they have obtained ethics approval from an appropriately constituted ethics committee/institutional review board where the research entailed animal or human participation.

All research procedures and materials were approved by the Baystate Health Institutional Review Board, #1451266-48.

Declarations of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Atsushi Matsumoto: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Claudia Santelices: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Elizabeth A. Evans: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Ekaterina Pivovarova: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Thomas J. Stopka: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Warren J. Ferguson: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Peter D. Friedmann: Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

References

- An Act for Prevention and Access to Appropriate Care and Treatment of Addiction, Chapter 208 of the Acts of 2018. https://malegislature.gov/Laws/SessionLaws/Acts/2018/Chapter208. [Google Scholar]

- Andraka-Christou B, Randall-Kosich O, Golan M, Totaram R, Saloner B, Gordon AJ, & Stein BD (2022). A national survey of state laws regarding medications for opioid use disorder in problem-solving courts. Health and Justice, 10, 14. 10.1186/s40352-022-00178-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandara S, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Merritt S, Barry CL, & Saloner B (2021). Methadone and buprenorphine treatment in United States jails and prisons: Lessons from early adopters. Addiction, 116(12), 3473–3481. 10.1111/add.15565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, & Stern MF (2013). Mortality after prison release: Opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Annals of Internal Medicine, 159(9), 592–600. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Cloud DH, Davis C, Zaller N, Delany-Brumsey A, Pope L, & Rich J (2017). Addressing excess risk of overdose among recently incarcerated people in the USA: Harm reduction interventions in correctional settings. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 13(1), 25–31. 10.1108/IJPH-08-2016-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Macmadu A, Marshall BD, Heise A, Ranapurwala SI, Rich JD, & Green TC (2018). Risk of fentanyl-involved overdose among those with past year incarceration: Findings from a recent outbreak in 2014 and 2015. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 185, 189–191. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brousseau NM, Farmer H, Karpyn A, Laurenceau JP, Kelly JF, Hill EC, & Earnshaw VA (2022). Qualitative characterizations of misinformed disclosure reactions to medications for opioid use disorders and their consequences. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 132, Article 108593. 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Andrade D, Ritchie J, Rowlands M, Mann E, & Hides L (2018). Substance use and recidivism outcomes for prison-based drug and alcohol interventions. Epidemiologic Review, 40(1), 121–133. 10.1093/epirev/mxy004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans EA, Stopka TJ, Pivovarova E, Murphy SM, Taxman FS, Ferguson WJ, & Bernadeau-Alexandre M (2021). Massachusetts justice community opioid innovation network (MassJCOIN). Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 128, Article 108275. 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans EA, Wilson D, & Friedmann PD (2022). Recidivism and mortality after in-jail buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Article 109254. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson WJ, Johnston J, Clarke JG, Koutoujian PJ, Maurer K, Gallagher C, & Taxman FS (2019). Advancing the implementation and sustainment of medication assisted treatment for opioid use disorders in prisons and jails. Health & Justice, 7(1), 1–8. 10.1186/s40352-019-0100-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, Hoskinson R Jr., Gordon M, Schwartz R, Kinlock T, & Knight K, for the MAT Working Group of CJ-DATS. (2012). Medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice agencies affiliated with the criminal justice-drug abuse treatment studies (CJ-DATS): Availability, barriers, and intentions. Substance Abuse, 33(1), 9–18. 10.1080/08897077.2011.611460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TC, Clarke J, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Marshall BD, Alexander-Scott N, Boss R, & Rich JD (2018). Postincarceration fatal overdoses after implementing medications for addiction treatment in a statewide correctional system. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(4), 405–407. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Ostile E, Scott CK, Dennis M, & Carnavale J (2020). A scoping review of barriers and facilitators to implementation of medications for treatment of opioid use disorder within the criminal justice system. International Journal of Drug Policy, 81, Article 102768. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen C, Kinner SA, Young JT, Snow K, Zhao B, Gan W, & Slaun-white AK (2021). Periods of altered risk for non-fatal drug overdose: A self-controlled case series. The Lancet Public Health, 6(4), e249–e259. 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AR (2018). Jail-based medication-assisted treatment: Promising practices, guidelines, and resources for the field . Available from https://www.sheriffs.org/publications/Jail-Based-MAT-PPG.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kouyoumdjian FG, Cheng SY, Fung K, Orkin AM, McIsaac KE, Kendall C, & Hwang SW (2018). The health care utilization of people in prison and after prison release: A population-based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. PloS One, 13(8), Article e0201592. 10.1371/journal.pone.0201592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Vigne N, Davies E, Palmer T, & Halberstadt R (2008). Release planning for successful reentry: A guide for corrections, service providers, and community groups. Washington, DC: Urban Institute, Justice Policy Center; Available from https://thesureshuttle.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/411767-Release-Planning-for-Successful-Reentry.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- London K, & Dupuis M (April 10, 2021). Massachusetts demonstration: Medicaid supports for justice-involved individuals with behavioral health needs. [PowerPoint slides]. https://commed.umassmed.edu/sites/default/files/publications/BH-JI%20for%20ACCJH%204-9-21%20%20%20-%20%20Read-Only.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Martin RA, Gresko SA, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Stein LAR, & Clarke JG (2019). Post-release treatment uptake among participants of the Rhode Island Department of Corrections comprehensive medication assisted treatment program. Preventive Medicine, 128, Article 105766 Epub 2019 Jul 4. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health. (2017). An Assessment of fatal and nonfatal opioid overdoses in Massachusetts (2011-2015). Available from https://www.mass.gov/doc/legislative-report-chapter-55-opioid-overdose-study-august-2017/download.

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health. (2021). Data brief: Opioid-related overdose deaths among Massachusetts residents, November 2021. Available from https://www.mass.gov/doc/opioid-related-overdose-deaths-among-ma-residents-november-2021/download.

- Massachusetts Executive Office of Health and Human Services. (2022). MassHealth behavioral health supports for justice Involved individuals (BH-JI). https://www.mass.gov/masshealth-behavioral-health-supports-for-justice-involved-individuals-bh-ji.

- Monico LB, Mitchell SG, Welsh W, Link N, Hamilton L, Malvini Redden S, & Friedmann PD (2016). Developing effective interorganizational relationships between community corrections and community treatment providers. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 55(7), 484–501. 10.1080/10509674.2016.1218401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osher FC (2007). In Short-term strategies to improve reentry of jail populations: Expanding and implementing the APIC Model: 20 (pp. 9–18). American Jails. [Google Scholar]

- PEW Charitable Trusts. (2020). Brief: Opioid use disorder treatment in jails and prisons Washington, DC: Available from https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2020/04/opioid-use-disorder-treatment-in-jails-and-prisons. [Google Scholar]

- Pivovarova E, Evans EA, Stopka TJ, Santelices C, Ferguson WJ, & Friedmann PD (2022). Legislatively mandated implementation of medications for opioid use disorders in jails: A qualitative study of clinical, correctional, and jail administrator perspectives. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Article 109394. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich JD, McKenzie M, Larney S, Wong JB, Tran L, Clarke J, & Zaller N (2015). Methadone continuation versus forced withdrawal on incarceration in a combined US prison and jail: A randomized, open-label trial. The Lancet, 386(9991), 350–359. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62338-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML, Grella CE, Mischel AF, & Carnevale J (2021). The impact of the opioid crisis on US state prison systems. Health & Justice, 9(1), 1–16. 10.1186/s40352-021-00143-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, O’Grady KE, Kelly SM, Gryczynski J, Mitchell SG, & Schwartz RP (2016). Pharmacotherapy for opioid dependence in jails and prisons: Research review update and future directions. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 7, 27. 10.2147/SAR.S81602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicaid Reentry Act of 2021. (2021). H.R. 955 −117th Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/955.

- SocioCultural Research Consultants. (2021). Dedoose Version 9.0.17, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data.

- Stopka T, Rottapel R, Ferguson W, Pivovarova E, Del Toro-Mejias L, Friedmann P, & Evans E (2022). Medication for opioid use disorder treatment continuity post-release from jail: A qualitative study with community-based treatment providers. International Journal of Drug Policy In Press. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2017). Guideline for successful transition of people with mental or substance use disorders from jail and prison: Implementation Guide. Rockville, MD: (SMA)-16-4998. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh WN, Knudsen HK, Knight K, Ducharme L, Pankow J, Urbine T, & Friedmann PD (2015). Effects of an organizational linkage intervention on interorganizational service coordination between probation/parole agencies and community treatment providers. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(1). 10.1007/s10488-014-0623-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]