Abstract

The isopod crustaceans reported from or expected to occur in littoral and sublittoral marine habitats of the Southern California Bight (SCB) in the northeastern Pacific Ocean are reviewed. A total of 190 species, representing 105 genera in 42 families and six suborders are covered. Approximately 84% of these isopods represent described species with the remaining 16% comprising well-documented “provisional” but undescribed species. Cymothoida and Asellota are the most diverse of the six suborders, accounting for ca. 36% and 29% of the species, respectively. Valvifera and Sphaeromatidea are the next most speciose suborders with between 13–15% of the species each, while the suborder Limnorioidea represents fewer than 2% of the SCB isopod fauna. Finally, the mostly terrestrial suborder Oniscidea accounts for ca. 5% of the species treated herein, each which occurs at or above the high tide mark in intertidal habitats. A key to the suborders and superfamilies is presented followed by nine keys to the SCB species within each of the resultant groups. Figures are provided for most species. Bathymetric range, geographic distribution, type locality, habitat, body size, and a comprehensive list of references are included for most species.

Keywords: Baja California, intertidal, isopod crustaceans, keys to species, northeastern Pacific, southern California, subtidal

Introduction

The Southern California Bight (SCB) is an important ecological region and economic resource that extends more than 600 km from Point Conception, California, USA to Cabo Colonet, Baja California, Mexico in the northeastern Pacific Ocean (Fig. 1). Because of its diverse and productive coastal ecosystems (e.g., rocky and sandy beach intertidal habitats, marshes, bays, lagoons, and estuaries, nearshore kelp forests and reefs, and offshore soft-bottom and hard-bottom benthic habitats of the continental shelf, slope, basins, and submarine canyons), and its proximity to dense human populations and associated pollutant inputs, the SCB is the focus of some of the largest and most comprehensive ocean monitoring programs in the world (Schiff et al. 2002, 2016, 2019). A key component of these programs is documenting changes in bottom dwelling invertebrate communities over space and time. In the SCB these include long-term localized programs conducted by four major wastewater discharge agencies (see City of San Diego 2018; Los Angeles County Sanitation Districts 2020; City of Los Angeles 2021; Orange County Sanitation District 2022), as well as broader regional programs that have been conducted every 4 or 5 years since 1994 (e.g., Allen et al. 1998, 2002, 2007, 2011; Bergen et al. 1998; Ranasinghe et al. 2003, 2007, 2012; Gillett et al. 2017, 2022; Walther et al. 2017; Wisenbaker et al. 2021). Key to the success of these and other programs and surveys is assuring taxonomic standardization of the resultant macroinvertebrate data sets. Fortunately, the SCB has also been home to the Southern California Association of Marine Invertebrate Taxonomists (SCAMIT) since 1982, whose members have ensured the production of accurate and reliable information for the region’s macrobenthic invertebrate fauna since that time.

Figure 1.

Southern California Bight region from Point Conception, California, USA to Punta Colonet, Baja California, Mexico, including the eight Channel Islands and Islas Coronado.

Isopoda (Crustacea: Peracarida) is a diverse and ancient order of crustaceans comprising more than 10,600 living marine, freshwater and terrestrial species known worldwide (see Boyko et al. 2008 onwards). Several recent reviews have focused on the diversity and distribution of the major groups of isopods throughout the world. These include global reviews of the biodiversity of freshwater isopods (Wilson 2008a), the marine isopods exclusive of the epicarideans and asellotes (Poore and Bruce 2012), the bopyrid and cryptoniscid isopods that are ectoparasitic on other crustaceans (McDermott et al. 2010; Williams and Boyko 2012), and the cymothoid isopods that are parasites of marine and freshwater fishes (Smit et al. 2014). Also see Smit et al. (2019) for a review of the current state of knowledge for the various parasitic crustacean taxa, including the isopods. Overall, the isopods are well represented in the SCB with more than 130 species listed in SCAMIT (2021).

There are a number of general monographs, natural history guides, taxonomic keys, and other works relevant to the coastal marine invertebrates of the northeastern Pacific Ocean that contain useful information on SCB isopods even though many are focused on regions further to the north or south and in the Gulf of California (e.g., Richardson 1905a; Ricketts and Calvin 1952, 1968; Menzies and Barnard 1959; Johnson and Snook 1967; Schultz 1969; Kozloff 1974, 1983, 1996; Miller 1975; Allen 1976; Brusca and Brusca 1978; Brusca 1980; Lee and Miller 1980; Ricketts et al. 1985; Hinton 1987; Wetzer and Brusca 1997; Wilson 1997; O’Clair and O’Clair 1998; Sept 2002, 2019; Brusca et al. 2004, 2007; Kerstitch and Bertsch 2007). Additional information is included in several species checklists (e.g., Leistikow and Wägele 1999; Espinosa-Pérez and Hendrickx 2001a, 2006; Schmalfuss 2003; Campos and Villarreal 2008). However, except for treatments of the southern California coastal shelf and submarine canyons from more than 50 years ago (Menzies and Barnard 1959; Schultz 1966), a more recent survey of the offshore benthos of the Santa Maria Basin and Western Santa Barbara Channel in the northern SCB (Wetzer and Brusca 1997; Wilson 1997), and a guide to the intertidal and supralittoral species of the California and Oregon coasts (Brusca et al. 2007), most information on the coastal isopods of the region remains scattered amongst various taxonomic or ecological contributions. Consequently, there is presently no single comprehensive treatment of the SCB coastal isopod fauna.

The purpose of this guide is to review all macrobenthic species of isopods known or expected to occur in littoral or sublittoral marine habitats of the SCB. Most of these isopods are free-living species that inhabit soft or hard bottom habitats ranging from the upper intertidal to offshore continental shelf and upper slope (depths < 500 m), as well as inland bays and estuaries. Additional species that occur in deeper waters of the lower continental slope, nearshore basins, submarine canyons, and around oceanic islands in the region are also included. Some species are typically associated with more specific microhabitats or niches. For example, these include isopods living on or within sponges (e.g., some sphaeromatids and asellotes), species living commensally with other isopods or echinoderms (e.g., some asellotes and idoteids), species living on or closely associated with kelp or other marine algae (e.g., many idoteids), species that burrow into wood, algal holdfasts or other substrates (e.g., limnoriids and some sphaeromatids), species that are micropredators or temporary parasites of fishes (e.g., aegids, cirolanids, corallanids, gnathiids), and species that are obligate parasites of other crustaceans (epicarideans) or fishes (cymothoids). Finally, although the focus of this review is on marine isopods, halophilic or semi-terrestrial species within the suborder Oniscidea that occur at or just above the high tide line in many SCB intertidal areas are also included.

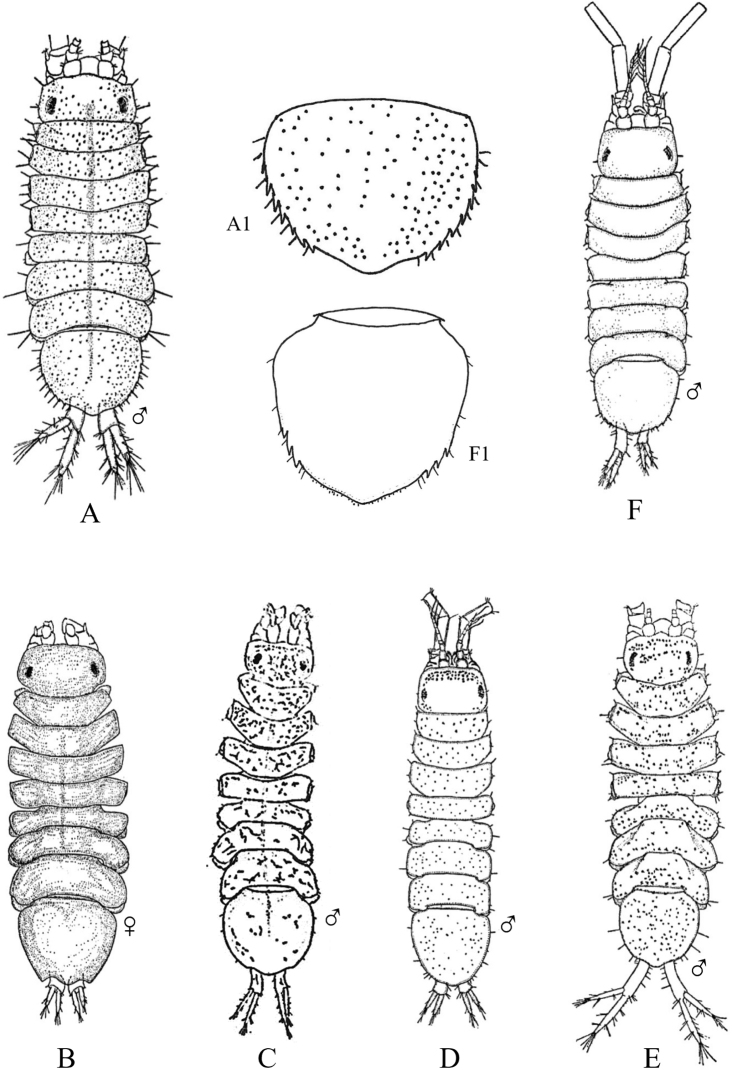

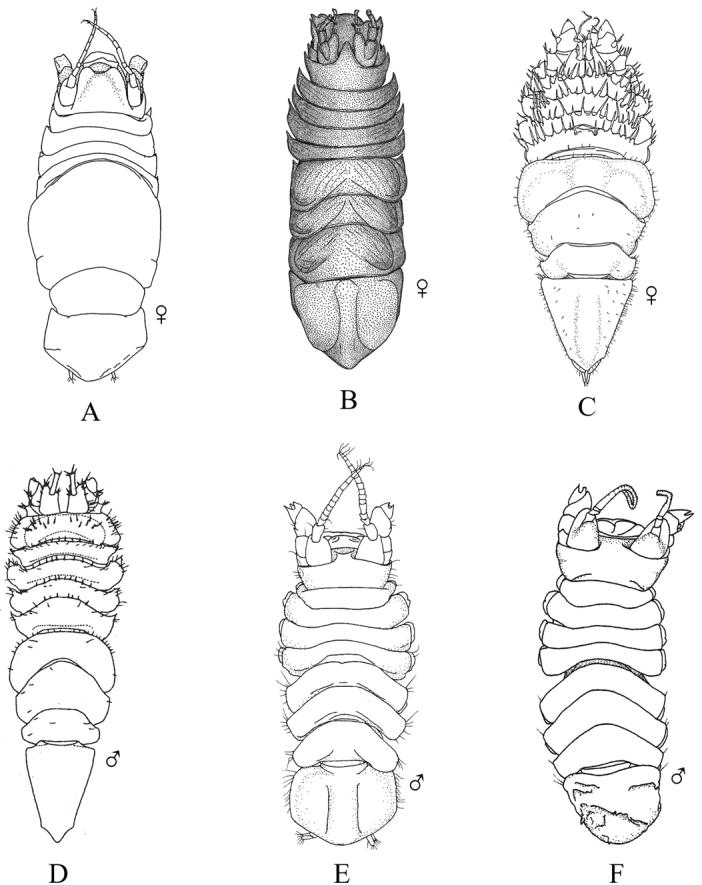

A key to the suborders and superfamilies of marine isopods occurring in the SCB is provided, which is followed by nine subsequent keys that identify the local isopod fauna to species. Some representative body types for the major groups are illustrated in Fig. 2. Dorsal whole-body illustrations are included for most species. Unless otherwise noted, these figures were reproduced or modified after original species descriptions or other sources as credited in their respective captions and the list of references. Additional figures illustrating enlarged views of specific diagnostic features referred to in the keys are provided where possible. For provisional (undescribed) species where no figures exist, an image of a representative congener is included if available. A series of endnotes to these keys is provided that includes comprehensive additional information useful in the identification or classification of specific taxa, but which does not fit neatly in the annotated list of species. This list follows the endnote section and includes bathymetric and geographic distribution information, type locality, brief habitat notes, maximum body size, and the primary taxonomic, biogeographical, and ecological literature references for each species. Our effort focuses on summarizing and organizing current biodiversity data for the SCB marine isopods and is our best attempt at bringing together their morphological, habitat, and distributional data. Although by no means exhaustive, we recognize that available illustrations in many instances are less than ideal. Presenting primarily dorsal whole-body figures is a means of standardizing taxonomic diversity and aiding in the identification of different species, but we acknowledge it is not always the best depiction of a given taxon. Other views are often readily available, and we encourage the reader to refer to the cited and original descriptions for greater detail.

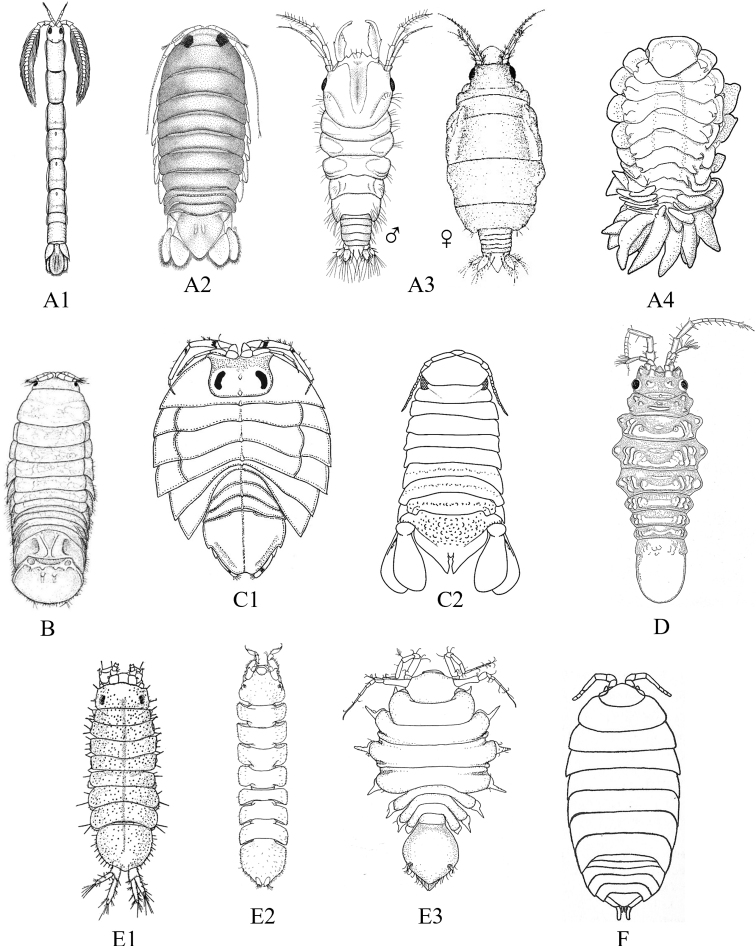

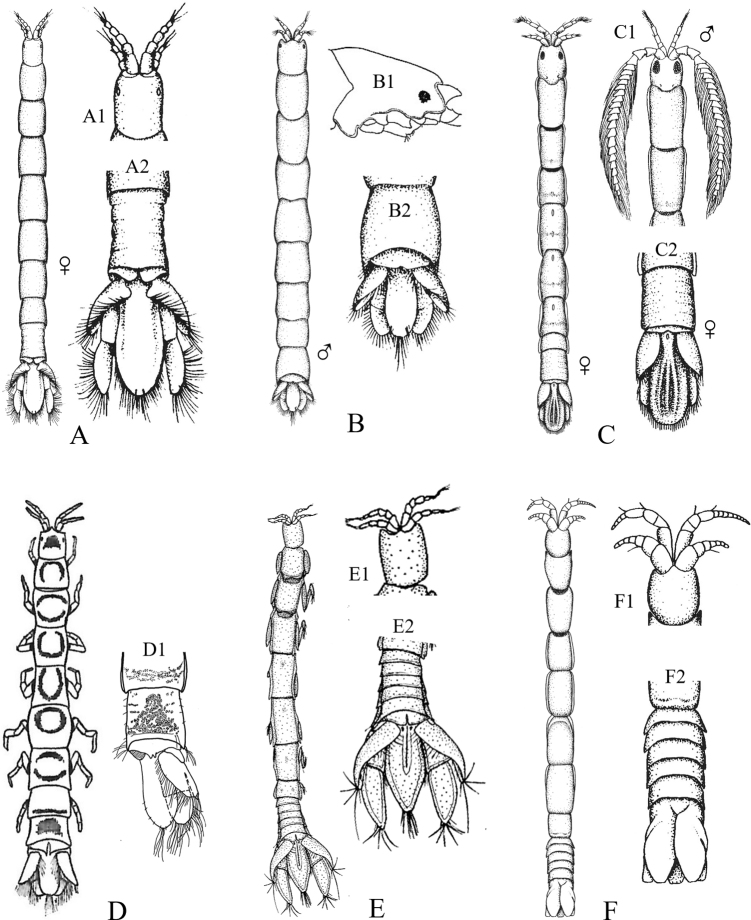

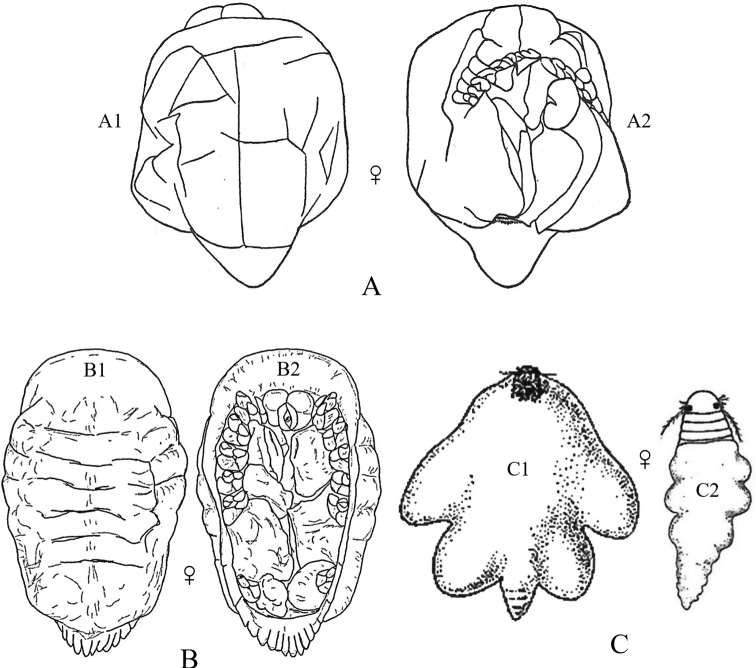

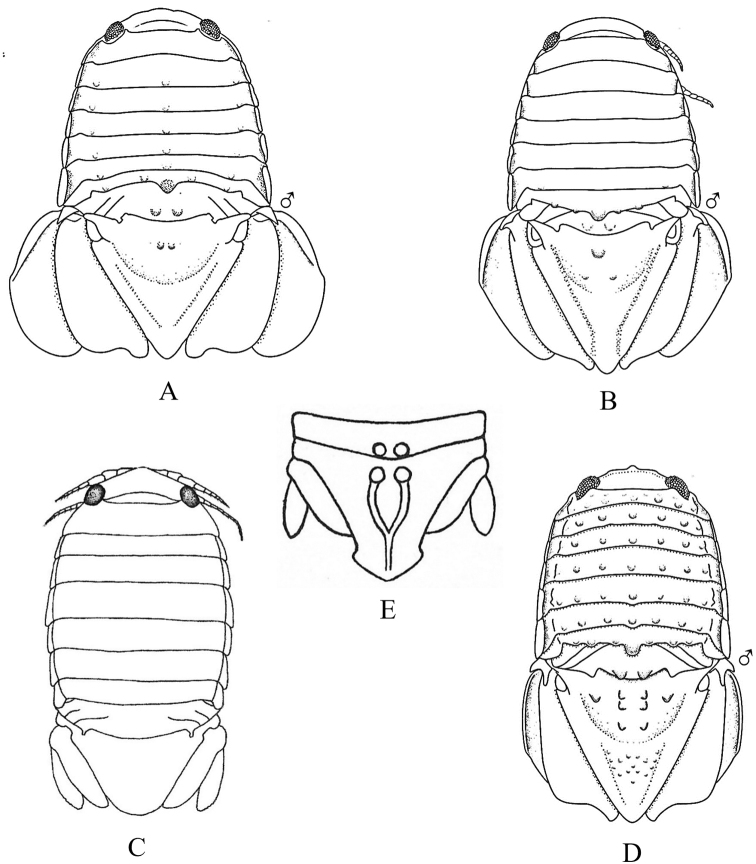

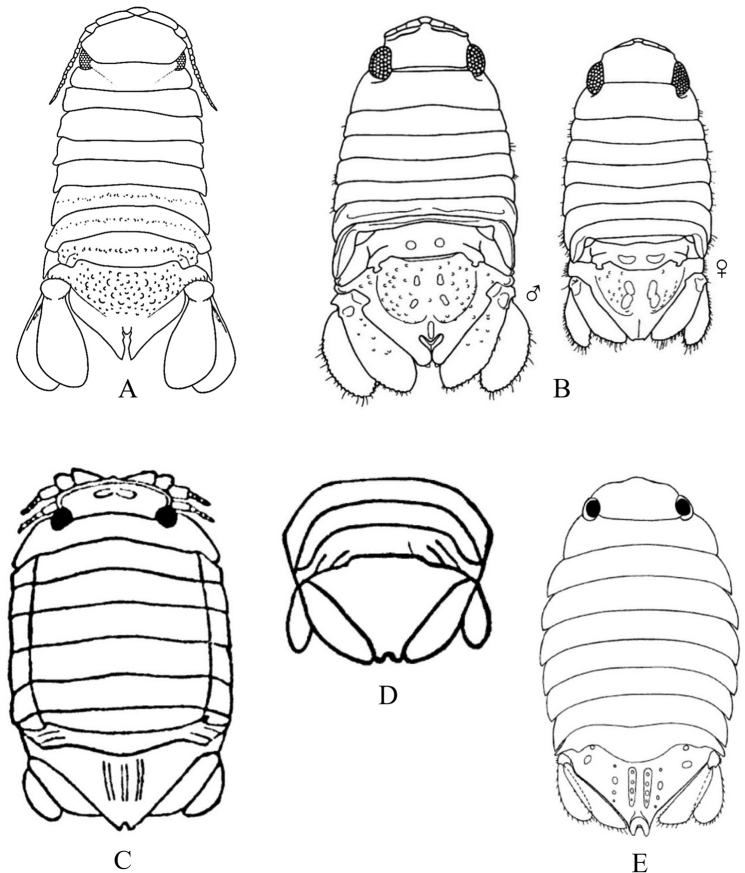

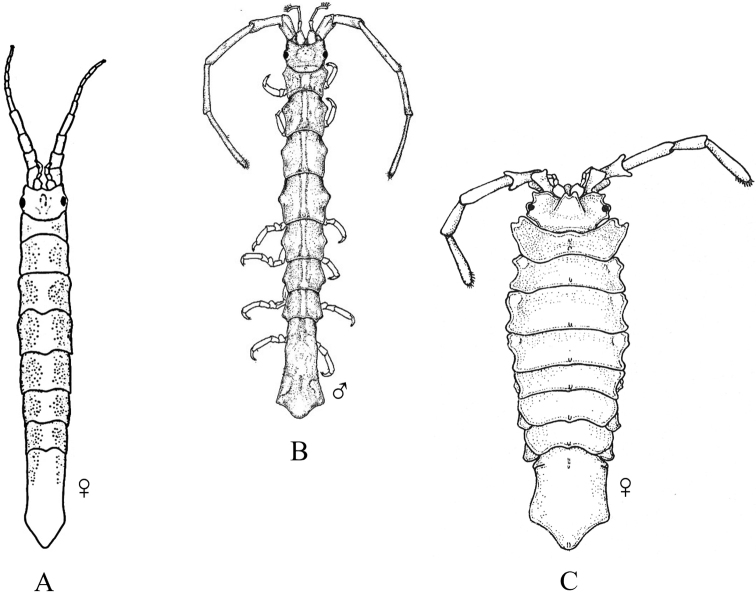

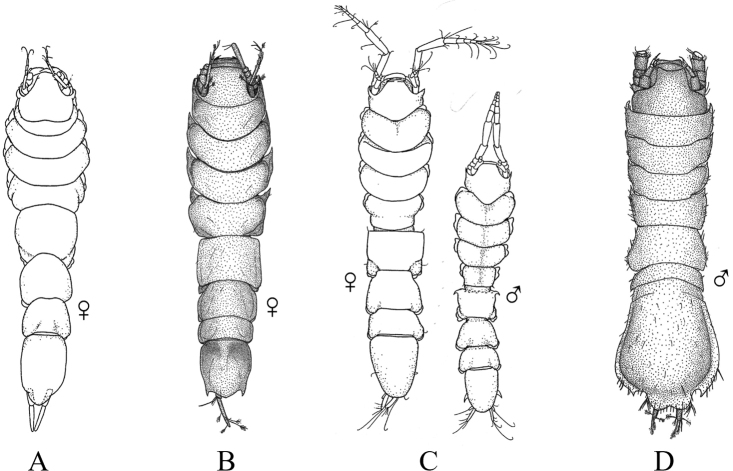

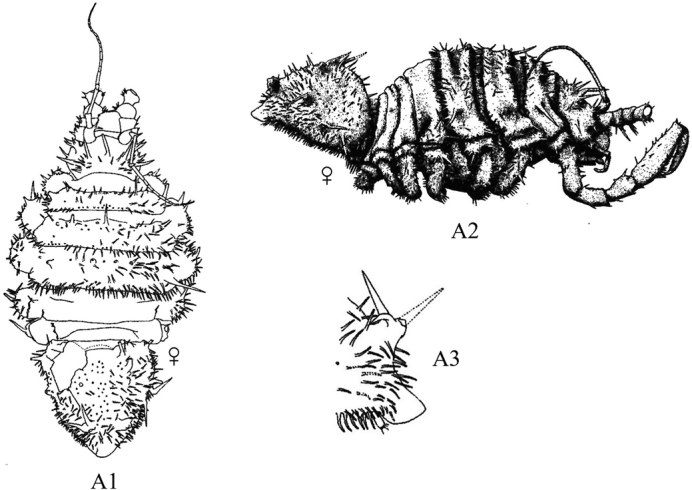

Figure 2.

Examples of representative family-level body types for each of the six suborders of marine isopods occurring in the SCB. A suborder CymothoidaA1Anthuridae (Haliophasmageminatum) A2Cirolanidae (Cirolanaharfordi) A3Gnathiidae (Gnathiatridens, male and female) A4Bopyridae (Munidionpleuroncodis) B suborder Limnorioidea, Limnoriidae (Limnoriaquadripunctata) C suborder SphaeromatideaC1Serolidae (Heteroseroliscarinata) C2Sphaeromatidae (Dynoideselegans) D suborder Valvifera, Idoteidae (Synidoteamagnifica) E suborder AsellotaE1Janiridae (Ianiropsisanaloga) E2Joeropsididae (Joeropsisconcava) E3Paramunnidae (Pleurogoniumcaliforniense) F suborder Oniscidea, Alloniscidae (Alloniscusperconvexus).

Materials and methods

Species review

All species currently recognized by the Southern California Association of Marine Invertebrate Taxonomists (SCAMIT 2021), as well as previously by the organization (SCAMIT 1994–2018) were reviewed and changes (e.g., additions, deletions, synonymies) verified. Additional species were added based on reviews of original species descriptions, taxonomic monographs, species or habitat guides, ecological studies, and published reports of site-specific or regional surveys conducted in the Southern California Bight (SCB) or elsewhere, as well as by personal observations and examination of field or museum specimens by the authors.

Classification and terminology

The higher-level classification of crustaceans and isopods has evolved over the past two decades, with 11 isopod suborders currently recognized, of which eight include marine species (e.g., see Martin and Davis 2001; Brandt and Poore 2003; Ahyong et al. 2011; Boyko et al. 2013; Wetzer et al. 2013; Martin et al. 2014; Wetzer 2015). The treatment followed herein for the SCB isopods reflects that presently accepted by the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS: Boyko et al. 2008 onwards) and SCAMIT (2021), with any differences between these lists addressed in the endnotes or annotated species list following the keys.

The Isopoda Latreille, 1817 can be distinguished from the other peracarid orders, and crustaceans in general, by the following combination of characters (after Brusca and Iverson 1985; Wetzer et al. 1997; Brusca et al. 2007).

Body usually dorsoventrally depressed but may be cylindrical or tubular in some suborders (e.g., Anthuridea and Phreatoicidea).

Body without a carapace but with a cephalic shield.

Head (cephalon) compact, typically with compound eyes, two pairs of antennae (first pair minute in Oniscidea), and mouthparts comprising one pair of mandibles, two pairs of maxillae, and one pair of maxillipeds.

Compound eyes sessile (not stalked) but may be on ocular lobes in some Asellota, Cymothoida (i.e., Gnathiidae), and Valvifera.

First and second antennae (antennules and antennae, respectively) uniramous, but with minute scales in a few taxa.

Mandible usually with a 1- to 3-articulate palp and a multidentate incisor process, left and right lacinia mobilis often differ, molar process highly variable.

First and second maxillae (maxillules and maxillae, respectively) without palps.

First thoracic appendages (thoracopods) modified as maxillipeds comprising fifth pair of mouthparts.

Long thorax of eight segments (thoracomeres), the first (and second in Gnathiidae) fused to the cephalon and bearing the maxillipeds, the remaining seven segments (pereonites) being free and collectively comprising a region called the pereon.

Pereon with seven pairs of uniramous legs (pereopods), all generally alike; the exception being the Gnathiidae in which only five pairs of walking legs are present.

Abdomen (pleon) relatively short comprising six somites (pleonites), at least one of which is always fused to the telson to form a pleotelson.

Six pairs of biramous pleonal appendages, including five pairs of plate-like pleopods specialized for respiration and/or swimming, and one pair of fan-like or stick-like, uniarticulate uropods.

Heart located primarily in the pleon.

Young isopods develop within a brood pouch (female’s marsupium) and emerge as a manca before appearance of the last pair of pereopods. Mancas have six pairs of pereopods.

Biphasic molting in which the posterior half of the body molts before the anterior half.

In terms of reproductive status, isopods can be sexed based on the presence or absence of male or female secondary sex characters. If oostegites (or a marsupium) are present with or without eggs or developing embryos, an individual is obviously female. If oostegites are absent, males can be distinguished by the presence of paired penes (may be fused) on the sternum of pereonite 7 (or pleonite 1) and/or appendices masculinae on the endopods of the second pleopods. Absence of all these characters indicates that the individual is either a juvenile, an immature female, or an immature male that has not yet developed secondary sexual features.

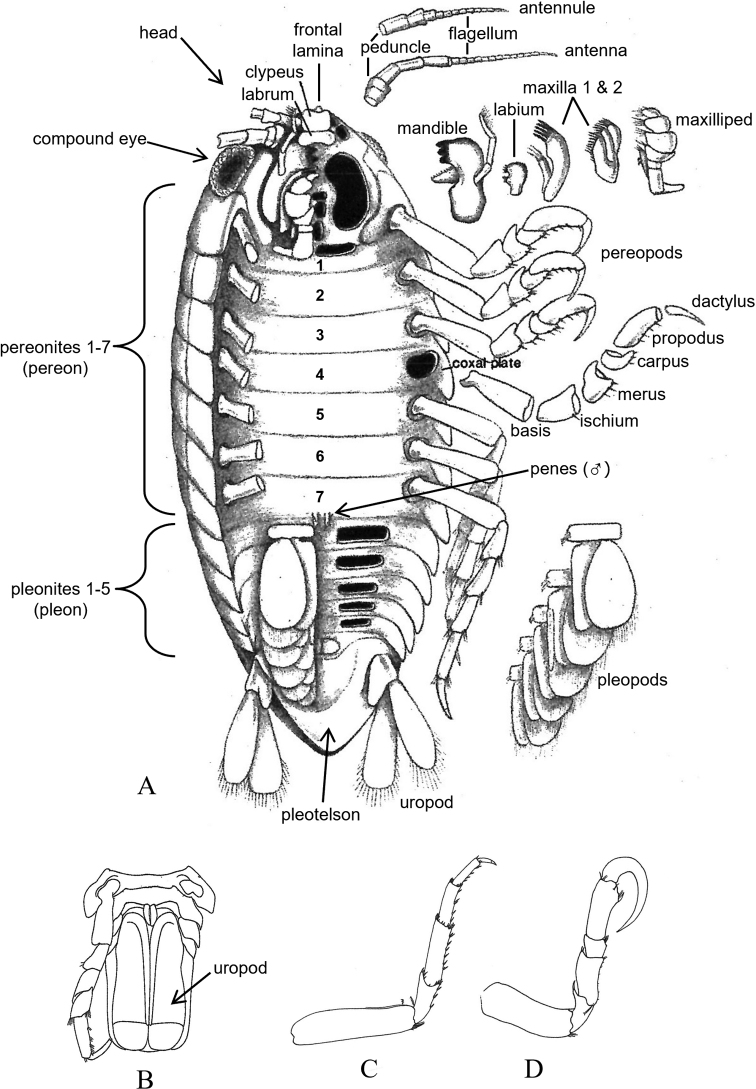

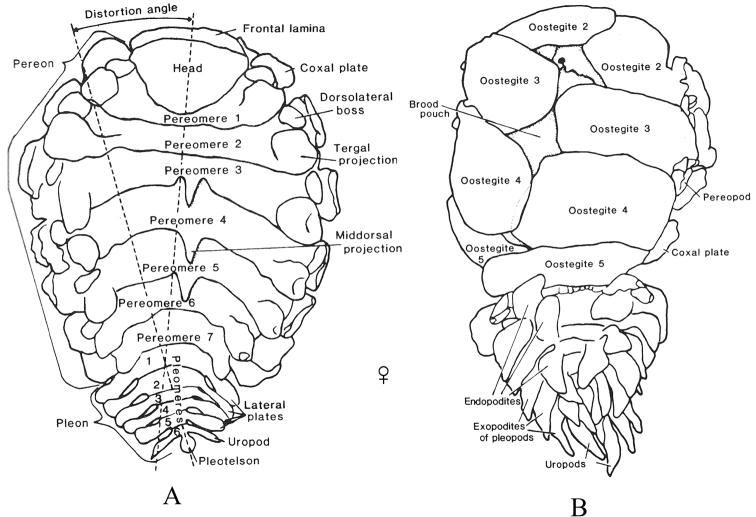

Terminology in the keys follows that which is typical for isopods in general (see Brusca and Iverson 1985; Kensley and Schotte 1989; Brusca and Wilson 1991; Wetzer et al. 1997; Brusca et al. 2007). The generalized isopod body plan characteristic of most groups is diagrammed in Fig. 3A, while Fig. 4 shows the specialized body plan characteristic of an adult female bopyrid (i.e., representative epicaridean). See Cohen and Poore (1994: fig. 1) for a detailed diagram of a stylized male gnathiid isopod.

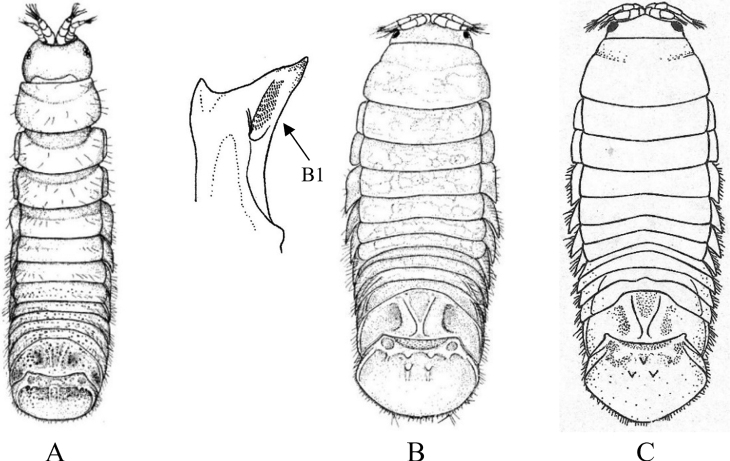

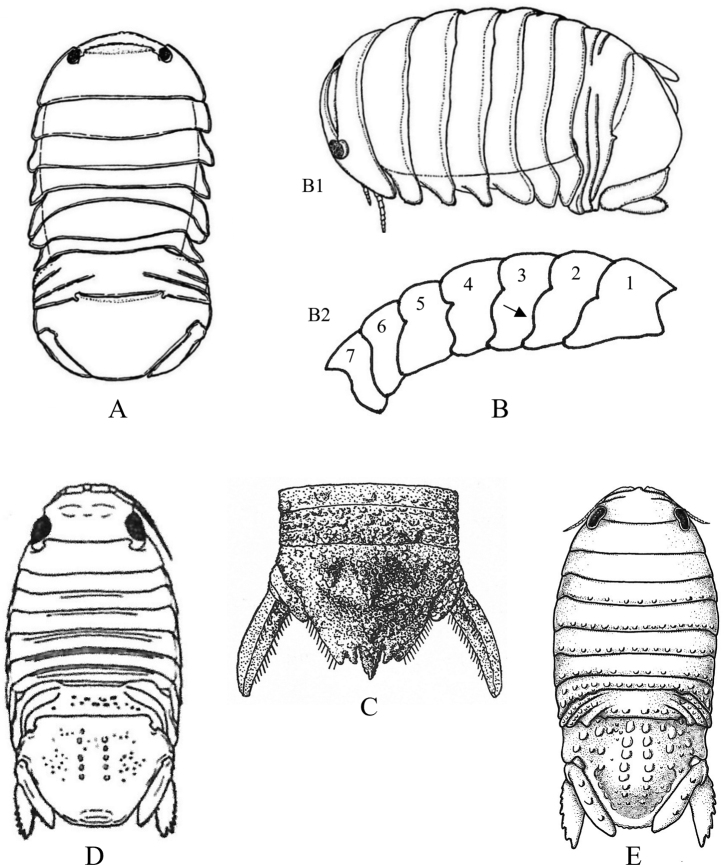

Figure 3.

A Generalized isopod body plan (modified after Kensley and Schotte 1989: fig. 2) B ventral view of valviferan pleon and pleotelson showing opercular uropods (after Poore and Lew Ton 1993: fig. 25) C example of ambulatory pereopod (after Brusca 1983a: fig. 11G) D example of prehensile pereopod (after Brusca 1983a: fig. 11F).

Figure 4.

Bopyrid isopod body plan (adult female). A dorsal view B ventral view. Modified after Markham (1985a: fig. 2).

In general, the isopod body is divided into three regions: the cephalon (head), pereon, and pleon. The cephalic region is referred to as “head” throughout the following keys. The segments of the pereon are referred to as pereonites 1–7 for most taxa or as pereomeres 1–7 for the epicarideans. Likewise, the segments of the pleon are referred to as pleonites 1–5 and the pleotelson (incorporating the fused pleonite 6 and telson) for most taxa (unless fused into fewer segments) or as pleomeres 1–6 plus telson for the epicarideans. The appendages of the pereon are numbered as pereopods 1–7, while the appendages of the pleon are referred to as pleopods 1–5 plus the uropods for all taxa. The first antennae (antenna 1) and second antennae (antenna 2) are referred to as antennules and antennae, respectively. Additional terminology is defined in glossaries of technical terms provided in Martin et al. (2022). Other useful glossaries are included in Kensley and Schotte (1989) and Wetzer et al. (1997), while Brusca and Wilson (1991) provide an extensive detailed description of isopod morphology. Key references regarding taxonomy, systematics, biogeography, and ecology of various isopod taxa are listed below for each suborder represented in this review, while specific references for each species are provided in the annotated species list.

Suborder Cymothoida: Primary references for the superfamily Anthuroidea include Menzies and Barnard (1959), Poore (1975, 1980, 1984a, 1984b, 2001a), Wägele (1984a), Poore and Lew Ton (1986, 1988a, 1988b, 1988c, 1988d), Cadien and Brusca (1993), and Annisaqois and Wägele (2021). Key references for the superfamily Cymothooidea are available for the families Aegidae (e.g., Brusca 1983a; Brusca and France 1992; Bruce 2009a), Cirolanidae (e.g., Bruce 1981; Brusca et al. 1995), Corallanidae (e.g., Delaney 1984, 1989), Cymothoidae (e.g., Brusca 1981; Bruce 1990; Smit et al. 2014; Hata et al. 2017), Gnathiidae (e.g., Cohen and Poore 1994; Smit and Davies 2004; Haney 2006; Tanaka 2007; Wilson et al. 2011), and Tridentellidae (e.g., Bruce 1984; Delaney and Brusca 1985). Within the infraorder Epicaridea, the family Bopyridae has been treated in detail in a long series of papers by Markham since the 1970s (e.g., Markham 1974a, 1975, 1977a, 1985a, 1986, 1992, 2001, 2003, 2004, 2008, 2016, 2020), while Boyko and Williams (2021a, 2021b) recently covered the two known local genera of the family Dajidae. Other valuable recent references for bopyrid and dajid isopods include Boyko et al. (2017), Williams et al. (2019), and Williams and Boyko (2021).

Suborder Limnoriidea: Key references for the family Limnoriidae include Menzies (1951a, 1957, 1958), Cookson (1991), and Borges et al. (2014).

Suborder Sphaeromatidea: Key references for the family Serolidae include Sheppard (1933), Harrison and Poore (1984), Brandt (1988), Wägele (1994), and Bruce (2009b), while important references for the family Ancinidae include Holmes and Gay (1909), Menzies and Barnard (1959), Schultz (1973), Glynn and Glynn (1974), Bruce (1993), and Shimomura (2008). Key references for the Sphaeromatidae include Menzies (1954), Harrison and Holdich (1982, 1984), Harrison and Ellis (1991), Bruce (1993), Schotte (2005), Wetzer et al. (2013, 2018, 2021), Wall et al. (2015), and Wetzer and Mowery (2017).

Suborder Valvifera: Key references for the valviferans include Menzies (1950a, 1951b), Sheppard (1957), Menzies and Barnard (1959), Menzies and Miller (1972), Brusca and Wallerstein (1977), Brusca (1983b, 1984), Brandt (1990), Poore and Lew Ton (1990, 1993), Rafi and Laubitz (1990), Wägele (1991), Poore (2001b, 2015), and King (2003).

Suborder Asellota: Key references for the asellotes include Menzies (1951b, 1952), Menzies and Barnard (1959), George and Strömberg (1968), Hessler et al. (1979), Wilson and Hessler (1980, 1981), Poore (1984c), Wilson (1987, 1994, 1997, 2008b), Wilson and Wägele (1994), Serov and Wilson (1995), Just and Wilson (2004, 2007, 2021), Doti and Wilson (2010), and Brix et al. (2021).

Suborder Oniscidea: Useful references for the oniscids include Van Name (1936, 1940, 1942), Garthwaite et al. (1985, 1992), Garthwaite and Lawson (1992), Leistikow and Wägele (1999), Schmalfuss (2003), Schmidt and Leistikow (2004), Schmidt (2008), and Sfenthourakis and Taiti (2015).

Results

Biodiversity

A total of 190 species of isopods are covered in this review of the Southern California Bight (SCB) isopod fauna, representing 105 genera, 42 families, and six suborders (Appendix 1). These include all but two of the 132 species-level taxa currently recognized by SCAMIT (2021)Endnote 1. Approximately 84% of these isopods represent described species (see Boyko et al. 2008 onwards), while the remaining 16% represent well-documented “provisional” but undescribed species.

Of the six isopod suborders occurring in SCB coastal and offshore waters, the Cymothoida and Asellota are the most diverse, accounting for ~ 36% and 29% of the species, respectively (Table 1). The Valvifera and Sphaeromatidea are the next most speciose suborders, accounting for ~ 13–15% of species, while the suborder Limnorioidea is represented by only three species (< 2%) in SCB waters. Finally, the suborder Oniscidea is represented by nine species (~ 5%) that occur at the terrestrial-marine interface in several intertidal areas of the SCB. See Brusca et al. (2007) or contact R Wetzer for more complete lists of California oniscid isopods.

Table 1.

Number of families, genera, and species for each of the six isopod suborders occurring in littoral and sublittoral marine habitats of the Southern California Bight. For suborders represented by more than one superfamily, the breakdown per superfamily is indicated.

| Suborder/Superfamily | Number taxa per group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Families | Genera | Species | |

| Suborder Cymothoida | 15 | 47 | 69 |

| Superfamily Anthuroidea | 5 | 10 | 11 |

| Superfamily Cymothooidea | 6 | 18 | 38 |

| Infraorder Epicaridea | |||

| Superfamily Bopyroidea | 2 | 16 | 17 |

| Superfamily Cryptoniscoidea | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Suborder Limnoriidea | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Suborder Sphaeromatidea | 4 | 12 | 25 |

| Superfamily Seroloidea | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Superfamily Sphaeromatoidea | 3 | 12 | 24 |

| Suborder Valvifera | 4 | 12 | 29 |

| Suborder Asellota | 12 | 26 | 55 |

| Superfamily Janiroidea | 11 | 25 | 54 |

| Superfamily Stenetrioidea | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Suborder Oniscoidea | 6 | 6 | 9 |

| Total taxa | 42 | 105 | 190 |

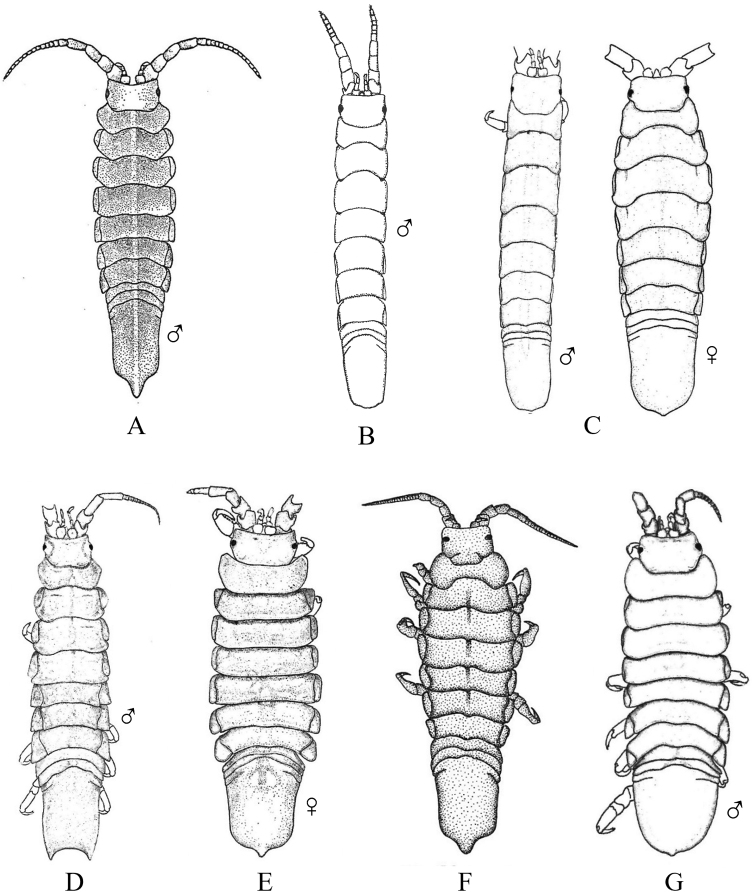

The suborder Cymothoida is represented by 69 species distributed amongst four superfamilies (Anthuroidea, Cymothooidea, Bopyroidea, Cryptnoniscoidea) and 15 families. The superfamily Anthuroidea, characterized by long, thin, cylindrical bodies usually at least 6 × longer than wide, includes 11 species in five families. Most anthuroids are thought to feed on other small invertebrates and occur in the SCB amongst fouling communities in marinas, bays, and harbors, and in both littoral and sublittoral habitats on the outer coast from the low intertidal to soft and hard-bottom benthos of the continental shelf, slope, and submarine canyons (0–1300 m depths).

The superfamily Cymothooidea is represented by six families with 38 species. Five of these families (Aegidae, Cirolanidae, Corallanidae, Cymothoidae, Tridentellidae) are generally similar in body form with sleek symmetrical bodies usually ~ 2–6 × longer than wide, the uropods and pleotelson forming a distinct tail fan, and the pereopods modified from ambulatory to prehensile reflecting their different lifestyles (e.g., Fig. 3C, D). For example, the family Cirolanidae is represented by seven species with mostly ambulatory pereopods, although pereopods 1–3 tend to have well-developed dactyli modified for grasping. In the SCB, these species occur intertidally on both sandy and rocky beaches, as well as in shallow to deep water habitats of the continental shelf, slope, and basins (0–1250 m depths). Corallanidae and Tridentellidae, represented by two species each in the SCB, are similar in shape to the cirolanids, but with the mouthparts and anterior pereopods modified for a predatory lifestyle. For example, the dactyli of pereopods 1–3 are usually as long or longer than the propodi and thus adapted for grasping prey. The two SCB corallanids occur from the intertidal to 138 m on the continental shelf, while the two SCB tridentellids have been reported from offshore depths of 53–360 m. The family Aegidae is represented by seven species in the SCB, all of which are temporary parasites of marine fishes and are characterized by prehensile pereopods 1–3 (dactylus strongly recurved and as long or longer than propodus). These species have been reported from the intertidal to deep waters of the continental shelf, slope, basins, and oceanic islands (0–2534 m depths). Although somewhat similar in general body form to the above four families, species of Cymothoidae are even more highly modified for a parasitic lifestyle with all seven pairs of pereopods being strongly prehensile. All cymothoids are obligate parasites of marine or freshwater fishes, most commonly being found attached in the gill chamber or buccal region of their host. Nine species of cymothoids are recognized herein as parasitizing a wide range of marine fishes in nearshore to offshore coastal waters of the SCB.

The sixth family of Cymothooidea occurring in SCB waters is Gnathiidae of which the males are highly modified and characterized by only six free pereonites and five pairs of pereopods. Eleven species of gnathiids are reported in the SCB, including three that are awaiting formal description. These 11 species occur in a wide range of habitats from the intertidal to shallow subtidal, and from the benthos of the offshore continental shelf, slopes, and submarine canyons to depths of ~ 1400 m.

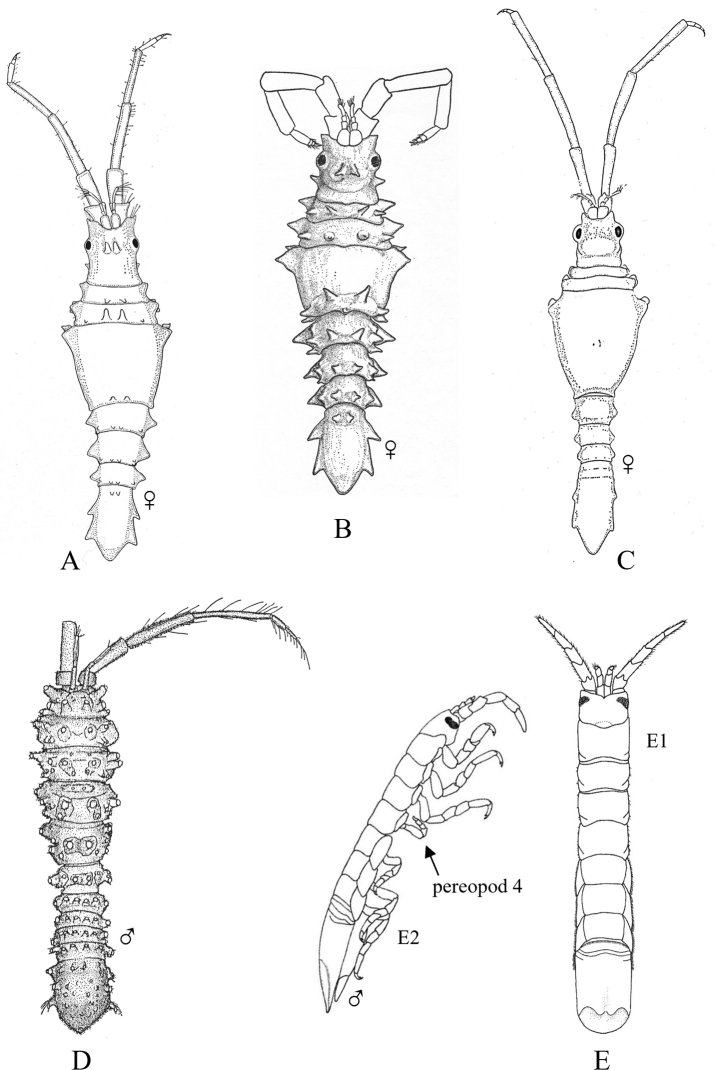

Bopyroidea and Cryptoniscoidea comprise the remaining two superfamilies of Cymothoida, both of which are highly modified obligate parasites of other crustaceans. Bopyroidea is represented by 17 species in two families (Bopyridae and Ionidae) in shallow to deep SCB waters. Sixteen of these species are branchial parasites of a wide range of decapod crustaceans (e.g., hermit crabs, shrimp, mud shrimp, ghost shrimp, galatheid crabs, squat lobsters, porcelain crabs, grapsid crabs) while one species is an abdominal parasite of mud shrimp. In contrast, Cryptoniscoidea is represented by only three species in two families. These include Dajidae represented herein by at least two species that are ectoparasites on the dorsal carapace of several species of shrimp, and Hemioniscidae represented by a single species that is an ectoparasite of barnacles.

The suborder Limnoriidea is represented by three species of the family Limnoriidae in SCB waters. All three species occur in shallow waters (0–30 m depth) where they burrow into either wood (2 species) or algal holdfasts (1 species).

The suborder Sphaeromatidea is represented by 25 species in SCB waters distributed between two superfamilies (Seroloidea and Sphaeromatoidea) and four families. The serolids (family Serolidae) presently include only a single recognized species in the SCB, Heteroseroliscarinata, which burrows just beneath the sediment surface from shallow waters in bays and harbors, and offshore to depths of ~ 100 m. However, it is possible that shallow vs. deep water populations in the region represent two distinct species (TDS, pers. obs.). In contrast, the superfamily Sphaeromatoidea includes 24 species in three families. Of these, the family Sphaeromatidae is the most diverse, represented herein by a total of 20 species. Most of these species occur from intertidal to shallow subtidal habitats < 30 m depth, although two species, Discerceisgranulosa and Paracerceisgilliana, have been reported from slightly deeper waters between 37–73 m. The other two sphaeromatoid families, Ancinidae and Tecticipitidae, are represented by only three and one species, respectively. All four of these species occur in intertidal or shallow subtidal habitats (< 30 m depths).

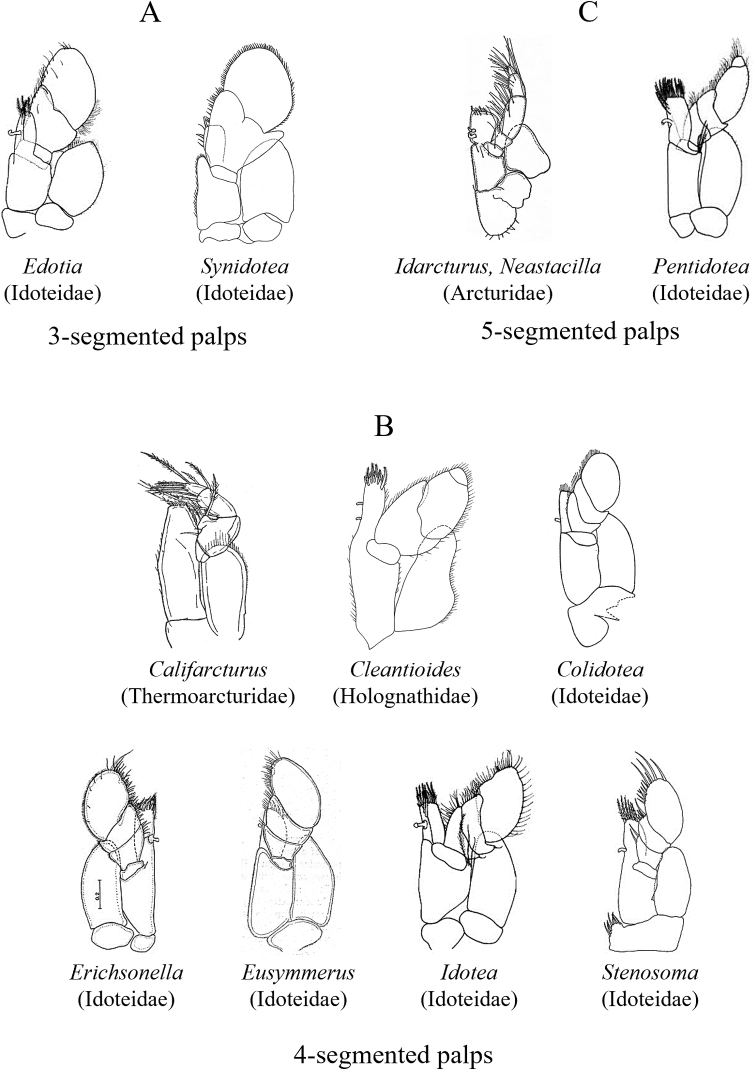

The suborder Valvifera can be distinguished from all other local isopods by the possession of hinged opercular uropods that cover the ventral surface of the pleon and pleotelson enclosing the pleopods (see Fig. 3B). Four families and 29 species of valviferans are represented in SCB waters. Idoteidae is the most diverse of these families, comprising 23 species in the study area. Many of these species, especially within the genera Colidotea, Erichsonella, Eusymmerus, Idotea, Pentidotea, and Stenosoma are most common in intertidal and shallow subtidal habitats associated with various species of kelp or algae. In contrast, the two local species of Edotia occur in soft-bottom habitats of the continental shelf between depths of ~ 14–64 m, while three of the four SCB species of Synidotea (except S.harfordi) occur on the shelf or slope at depths of ~ 30–800 m. The remaining three families of SCB valviferans comprise a total of six species. The family Arcturidae is represented by four species that occur in the low intertidal (1 species) or offshore shelf benthos (3 species) at depths < 100 m. The last two families are each represented by a single species. These include Cleantioidesoccidentalis of the Holognathidae in relatively shallow waters (intertidal to ~ 50 m), and Califarcturustannerensis of the Thermoarcturidae in deep waters (~ 1200–1300 m).

The suborder Asellota is represented by 55 species in SCB waters distributed between two superfamilies (Janiroidea and Stenetrioidea) and 12 families. However, only ~ 64% of these species are formally described, with the remaining 36% representing provisional species (see Appendix 1). Stenetrioidea includes a single species (Stenetrium sp. A) reported from 90–131 m in the Santa Maria Basin. In contrast, Janiroidea is represented by a diverse group of 11 families that occur in a wide range of habitats and depths from the intertidal to nearly 4000 m. Janiridae is the most diverse of these families, comprising 18 species; ca. two-thirds of the janirids occur in shallow waters from the intertidal to depths of ~ 30 m, while the remaining third occur on the continental shelf at depths between ~ 30–200 m. Paramunnidae is the next most diverse family with nine species, two of which occur in the shallow subtidal (9–20 m) and seven on the continental shelf (75–197 m). Munnidae is the third most diverse family with eight species, of which five species occur in intertidal to shallow subtidal habitats, two species occur at mostly shelf depths (12–237 m), and one species occurs in deeper slope waters (500 m). The Munnopsidae is represented by six species that occur at depths between 73–1118 m. The Joeropsididae is represented by five species that occur at depths from the intertidal to 161 m, while the Desmosomatidae includes three species that range in depth from ~ 100–3000 m. The remaining five families are each represented by a single species. These include Dendrotionidae (Acanthomunnatannerensis at ~ 600–800 m), Haplomunnidae (Haplomunnacaeca at ~ 4000 m), Lepidocharontidae (Microcharon sp. A at 75 m), Nannoniscidae (Nannonisconuslatipleonus at ~ 300–500 m), and Pleurocopidae (Pleurocope sp. A at < 1 m).

The suborder Oniscidea is represented in this review by nine species distributed between six families. Each of these species typically occurs at or above the high tide mark in its respective habitat. The families Alloniscidae (2 species) and Tylidae (1 species) occur on sandy beaches in the SCB. The Detonidae (3 species) and Halophiloscidae (1 species) both occur in marshes, bays, and estuaries. The Platyarthridae (1 species) is reported to occur on both sandy beaches and at the edges of marshes. The Ligiidae is represented herein by a single species that typically occurs in the spray zone on rocky intertidal shores.

Keys to species

Ten keys were constructed to facilitate identification of the 190 species of isopods included in this guide. Key A represents a key to the suborders and main superfamilies, which are then identified to species in Keys B–J. Keys B–E cover the suborder Cymothoida (superfamilies Anthuroidea, Cymothooidea, Bopyroidea, and Cryptoniscoidea). Key B covers the Anthuroidea (5 families, 11 species). Key C covers the families Aegidae, Cirolanidae, Corallanidae, Cymothoidae, and Tridentellidae of Cymothooidea (27 species). Key D covers the remaining cymothooidean family, Gnathiidae (11 species). Key E covers the epicaridean superfamilies Bopyroidea and Cryptoniscoidea (4 families, 20 species). Key F covers the suborder Limnoriidea (1 family, 3 species). Key G covers the superfamilies Seroloidea and Sphaeromatoidea of the suborder Sphaeromatidea (4 families, 25 species). Key H covers the suborder Valvifera (4 families, 29 species). Key I covers the superfamilies Janiroidea and Stenetrioidea of the suborder Asellota (12 families, 55 species). Key J covers the suborder Oniscidea (6 families, 9 species).

Key A. Suborders and Superfamilies of SCB Marine Isopods

| 1 | Adult isopods free-living, but may live commensally with other isopods or invertebrates; females and males with clear bilateral symmetry, typically similar in size; antennae well developed, never vestigial; antennules variable | 2 |

| – | Adult isopods obligate parasites of other crustaceans; females with slightly to highly distorted or reduced bilateral symmetry; male minute, bilaterally symmetrical, living on body of adult female; antennae vestigial in female; antennules reduced to ≤ 3 articles [Suborder Cymothoida: Superfamilies Bopyroidea and Cryptoniscoidea] | Key E |

| 2 | Adult isopods with 5 pairs of pereopods (thoracomere 2 fused to cephalon with its appendages modified into pylopods; thoracomere 8 reduced, without legs); adult males with enlarged, forward projecting forceps-like mandibles; females without mandibles [Suborder Cymothoida: Superfamily Cymothooidea (in part), Family Gnathiidae] | Key D |

| – | Adult isopods usually with 7 pairs of distinct pereopods (7th pair may be small and folded against ventral body wall in juveniles); newly released isopods (mancas) from the marsupium with only 6 pairs of pereopods; males without projecting forceps-like mandibles; females with mandibles | 3 |

| 3 | Species terrestrial or halophilic, mostly restricted to upper littoral (e.g., high tide line, spray zone) or brackish water habitats along coast; antennules vestigial, minute; pleon always composed of 5 free pleonites plus pleotelson [Suborder Oniscidea: Superfamily Oniscoidea] | Key J |

| – | Species fully marine, occurring in littoral or sublittoral habitats; antennules normal, or not minute if reduced; pleon variable, with or without fused pleonites | 4 |

| 4 | Uropods operculate, modified into pair of ventral covers (opercula) enclosing the pleopods (Fig. 3B), but do not confuse with operculate pleopods [Suborder Valvifera] | Key H |

| – | Uropods not modified as ventral opercula, hinged laterally or terminally on pleotelson | 5 |

| 5 | Uropods typically flattened and hinged on anterolateral margins of pleotelson (may be greatly reduced) | 6 |

| – | Uropods styliform and hinged terminally or nearly so on posterior margins of pleotelson [Suborder Asellota: Superfamilies Janiroidea and Stenetrioidea] | Key I |

| 6 | Adult body elongated, usually > 6 × longer than wide [Suborder Cymothoida: Superfamily Anthuroidea] | Key B |

| – | Adult body not elongated, < 4 × longer than wide (not elongated) | 7 |

| 7 | Uropods greatly reduced with small claw-like exopods, generally not visible dorsally; species burrow in wood or algal holdfasts [Suborder Limnoriidea: Superfamily Limnorioidea] | Key F |

| – | Uropods not as above, clearly visible dorsally as expanded, flattened “tail fan” or long caudal processes | 8 |

| 8 | Pleon composed of 4 or 5 free pleonites plus pleotelson [Suborder Cymothoida: Superfamily Cymothooidea (in part), Families Aegidae, Cirolanidae, Corallanidae, Cymothoidae, and Tridentellidae] | Key C |

| – | Pleon composed of ≤ 3 free pleonites plus pleotelson [Suborder Sphaeromatidea: Superfamilies Seroloidea and Sphaeromatoidea] | Key G |

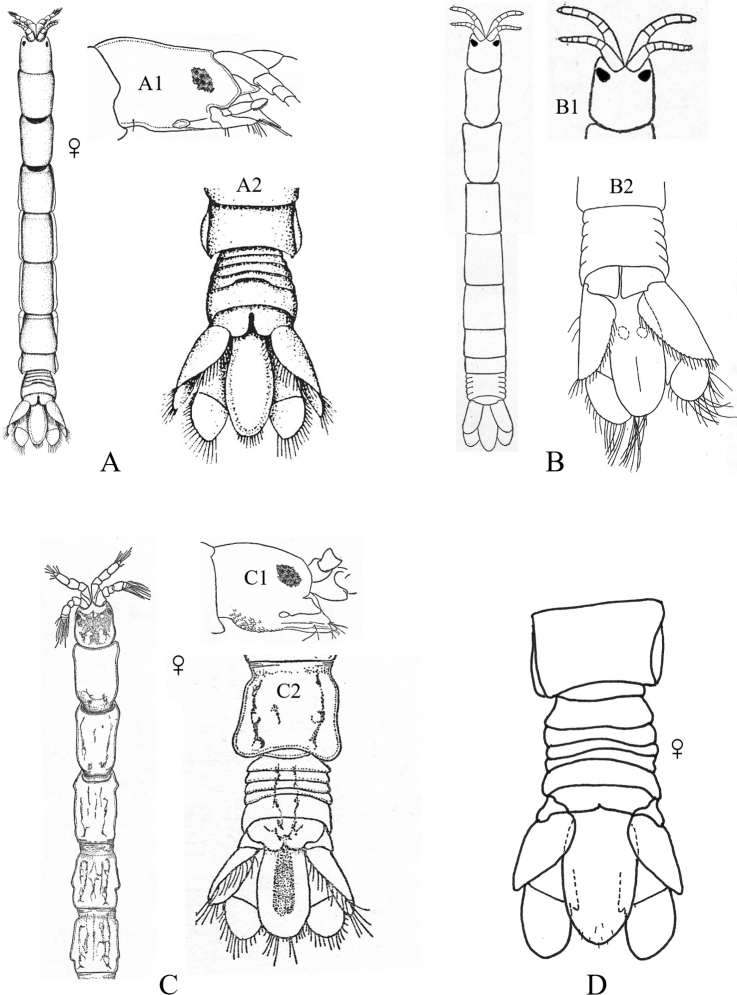

Key B. Suborder Cymothoida, Superfamily Anthuroidea

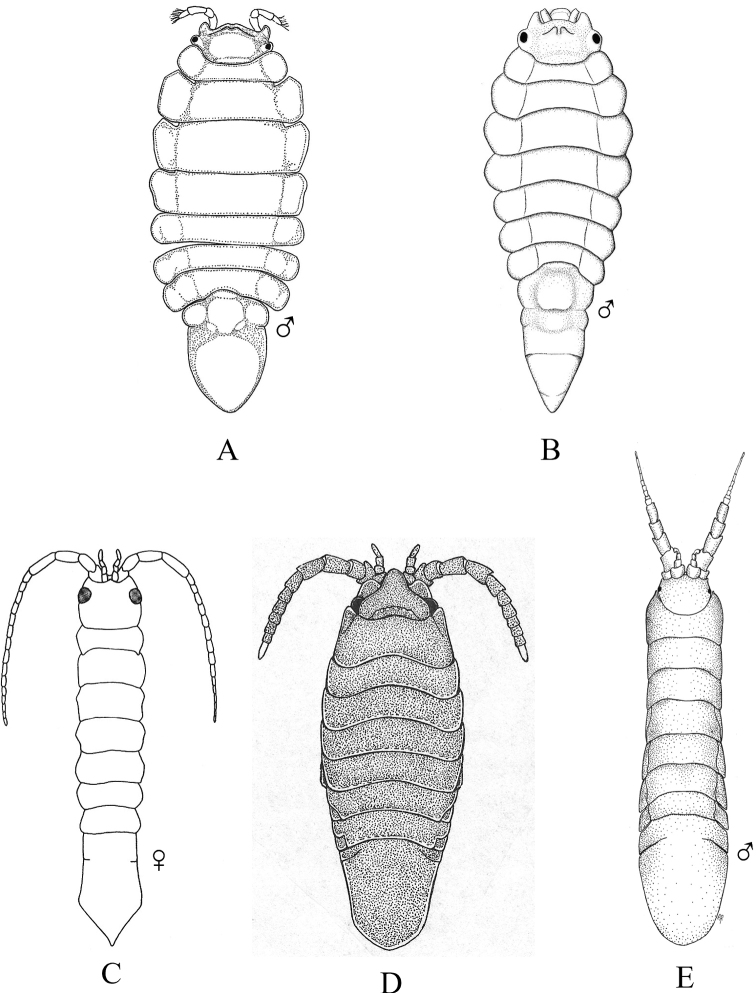

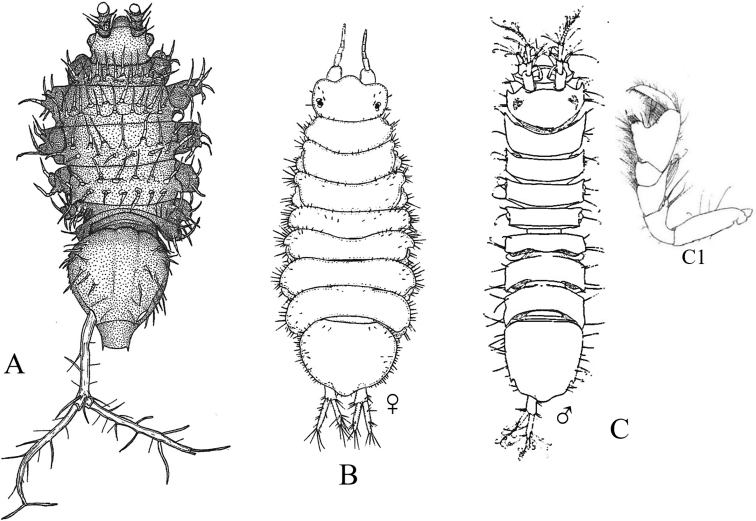

Figure 5.

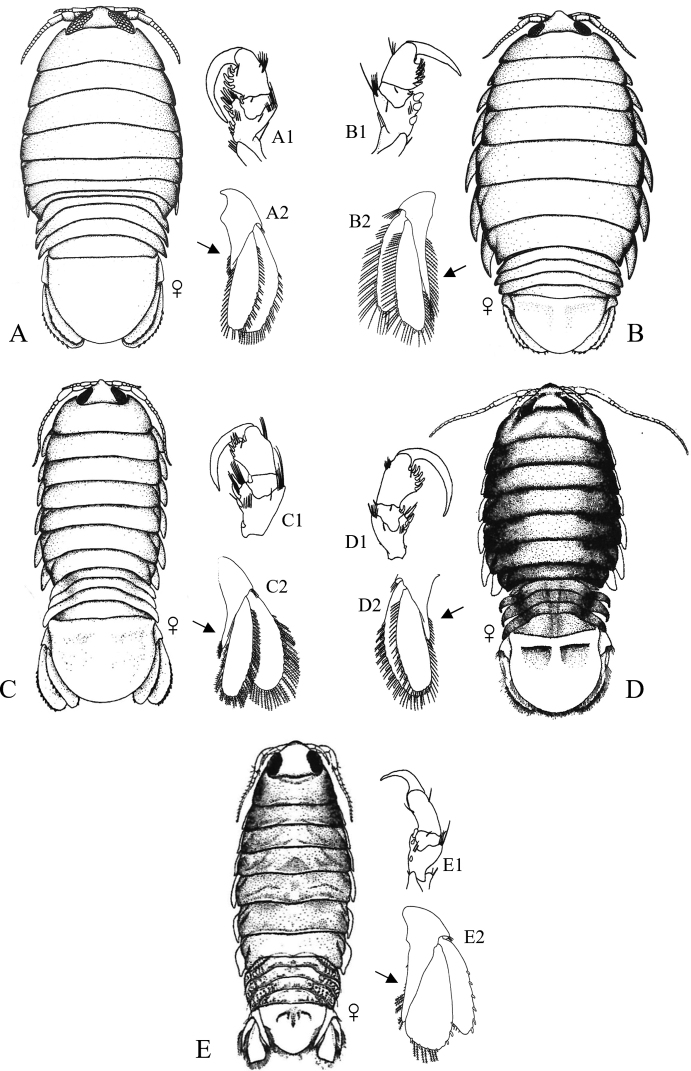

Isopoda, Cymothoida, Anthuroidea, Paranthuridae: AParanthuraelegansA1 lateral view of head (piercing mouthparts) A2 dorsal view of pereonite 7, free pleonites 1–5, pleotelson and uropods (after Menzies 1951b; Wetzer and Brusca 1997) BParanthurajaponicaB1 dorsal close-up view of head B2 dorsal view of fused pleonites 1–5, pleotelson and uropods (after Richardson 1909; Brusca et al. 2007) CCalifanthurasquamosissima (male with antenna loaded with aesthetascs) C1 lateral view of head (piercing mouthparts) C2 dorsal view of pereonites 6 and 7, dorsally fused pleonites 1–5, pleotelson and uropods (after Menzies 1951b) DColanthurabruscai, dorsal view of pereonites 6 and 7, free pleonites 1–5, pleotelson and uropods (after G. Poore, personal contribution).

Figure 6.

Isopoda, Cymothoida, Anthuroidea, Anthuridae: AAmakusanthuracaliforniensisA1 dorsal close-up view of head A2 dorsal view of pereonite 7, dorsally fused pleonites 1–5, pleotelson and uropods (after Wetzer and Brusca 1997) BCyathuramundaB1 lateral view of head (biting mouthparts) B2 dorsal view of pereonite 7, dorsally fused pleonites 1–5, pleotelson and uropods (after Menzies 1951b) CHaliophasmageminatumC1 dorsal view of head and pereonites 1 and 2 of male C2 dorsal view of pereonite 7, dorsally fused pleonites 1–5, pleotelson and uropods (after Wetzer and Brusca 1997) DMesanthuraoccidentalisD1 dorsal view of pereonite 7, dorsally fused pleonites 1–5, pleotelson and right uropod (after Allen 1976). Antheluridae: EAnanthuralunaE1 dorsal close-up view of head E2 dorsal view of pereonite 7, free pleonites 1–5, pleotelson and uropods (after Schultz 1966). Hyssuridae: FKupellonura sp. A F1 dorsal close-up view of head F2 dorsal view of pereonite 7, free pleonites 1–5, pleotelson and uropods (after Wetzer and Brusca 1997).

| 1 | Eyes present | 2 |

| – | Eyes absent | 10 |

| 2 | Mouthparts form forward directed cone-like structure under the head, adapted for piercing and sucking | 3 [Paranthuridae] |

| – | Mouthparts not forming ventral cone-like structure, adapted for biting and chewing | 6 |

| 3 | Pereon composed of 7 distinct, well-developed pereonites with 7 pairs of pereopods; pereonite 7 ca. half as long as pereonite 6 and visible laterally | 4 |

| – | Pereon composed of 6 distinct pereonites with 6 pairs of pereopods (7th pereopods absent); pereonite 7 very short, < 20% as long as pereonite 6, not visible laterally | 5 |

| 4 | Pleonites 1–5 free, not fused; pleonite 5 ca. 3 × longer than other pleonites (Fig. 5A) | Paranthuraelegans |

| – | Pleonites 1–5 fused mid-dorsally, but distinct laterally; all pleonites of similar length (Fig. 5B) | Paranthurajaponica |

| 5 | Pleonites 1–5 free, separated from each other by dorsal integumental folds; pleonite 1 ca. 2 × longer than pleonite 2 (Fig. 5D) | Colanthurabruscai |

| – | Pleonites 1–5 dorsally fused, all pleonites of similar length (Fig. 5C) | Califanthurasquamosissima |

| 6 | Dorsal surface of pleotelson with median row of spines; uropodal and pleotelsonic margins serratedEndnote 2 | Eisothistos sp. A [Expanathuridae] |

| – | Dorsal surface of pleotelson smooth or ridged, without spines; uropodal and pleotelsonic margins not serrated | 7 [Anthuridae] |

| 7 | Pleotelson with 3 raised dorsal longitudinal ridges or carinae; uropodal exopods curve up and over base of pleotelson (Fig. 6C) | Haliophasmageminatum |

| – | Pleotelson without dorsal ridges or carinae; uropodal exopods may or may not curve up over pleotelson | 8 |

| 8 | Pleonites 1–5 fused only along dorsal midline, segments free laterally and visible dorsally; uropodal exopods ca. half length of endopods and pleotelson, curving up and partially over pleotelson base; uropodal endopods narrow, ca. half as wide as pleotelson (Fig. 6A) | Amakusanthuracaliforniensis |

| – | Pleonites 1–5 completely fused dorsally; uropodal exopods > 50% length of endopods and pleotelson, may or may not cover the pleotelson dorsally; uropodal endopods broad, subequal in width to pleotelson | 9 |

| 9 | Dorsal surface of pereon pigmented, with complete or nearly complete dark rings on pereonites 2–6 and posterior transverse band on pereonite 7; uropodal exopods partially cover dorsal surface of pleotelson (Fig. 6D) | Mesanthuraoccidentalis |

| – | Dorsal surface of pereon covered with diffuse pigment splotches, but without pigment rings; uropodal exopods do not cover base of pleotelson (Fig. 6B) | Cyathuramunda |

| 10 | Uropodal exopods with distinct lateral lobes, exopods overlapping broadly to cover almost entire dorsal surface of pleotelson; uropodal rami nearly reach, but do not exceed, posterior margin of pleotelson; tips of uropodal rami without tufts of stiff setae (Fig. 6F) | Kupellonura sp. A [Hyssuridae] |

| – | Uropodal exopods without lateral lobes, overlapping only base of pleotelson; uropodal endopod distinctly longer than pleotelson; tips of uropodal rami with tufts of long stiff setae (Fig. 6E) | Ananthuraluna [Antheluridae] |

Key C. Suborder Cymothoida, Superfamily Cymothooidea (in part): Families Aegidae, Cirolanidae, Corallanidae, Cymothoidae, Tridentellidae

Figure 7.

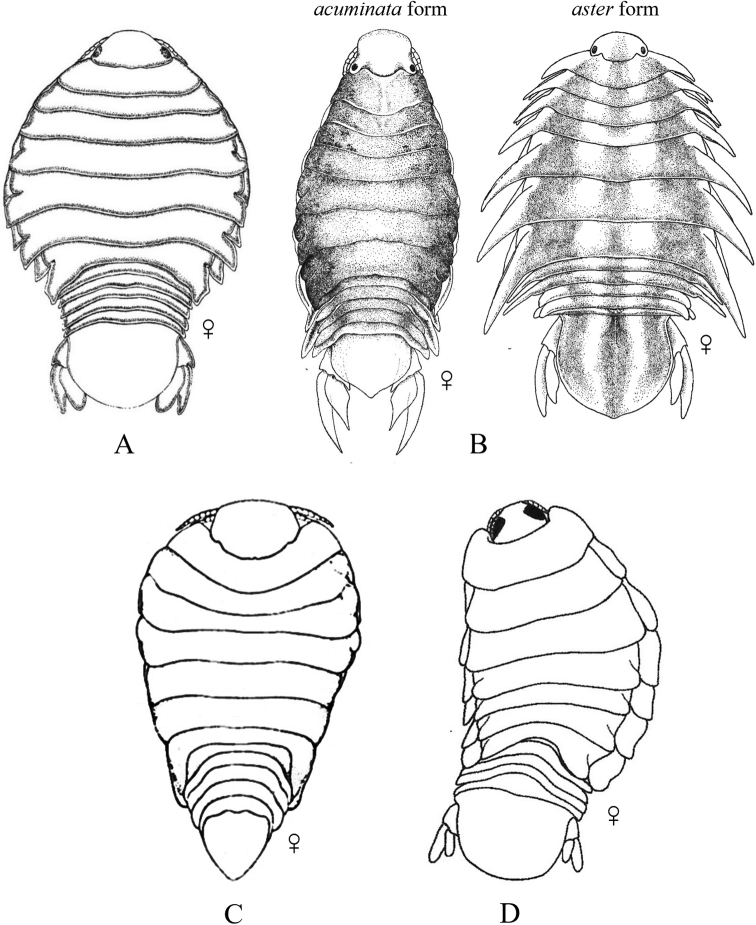

Isopoda, Cymothoida, Cymothooidea, Cirolanidae: ACirolanadiminuta (after Brusca et al. 1995) BCirolanaharfordi (after Brusca et al. 1995) CEurydicecaudata (after Brusca et al. 1995) DExcirolanachiltoni (after Schultz 1969) EExcirolanalinguifrons (after Schultz 1969) FMetacirolanajoanneae (after Schultz 1966) GNatatolanacaliforniensis (after Brusca et al. 1995).

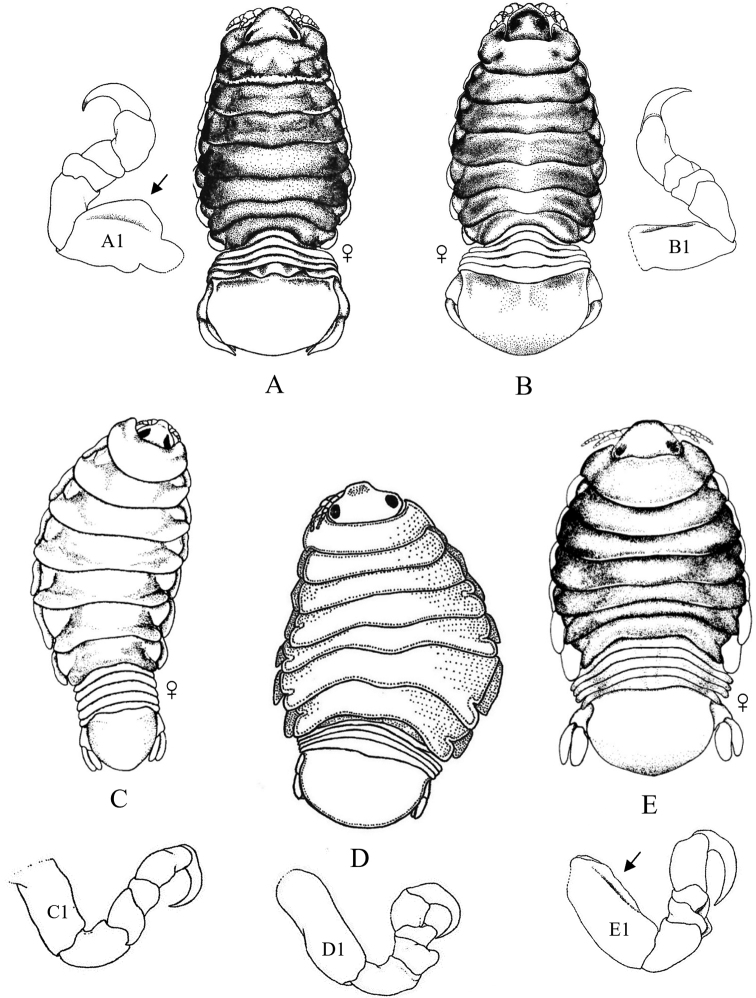

Figure 11.

Isopoda, Cymothoida, Cymothooidea, Cymothoidae (in part): ACeratothoagaudichaudiiA1 pereopod 4 with arrow indicating carina (after Brusca 1981) BCeratothoagilbertiB1 pereopod 4 (after Brusca 1981) CElthusacalifornicaC1 pereopod 4 (after Brusca 1981) DElthusamenziesiD1 pereopod 4 (after Menzies 1962a; Brusca 1981) EElthusavulgarisE1 pereopod 4 with arrow indicating carina (after Brusca 1981).

| 1 | Pereopods 1–3 ambulatory with dactylus shorter than propodus (e.g., Fig. 3C) | 2 [Cirolanidae] |

| – | Pereopods 1–3 prehensile or sub-prehensile with dactylus generally as long as, or longer than propodus and strongly curved (e.g., Fig. 3D) | 8 |

| 2 | Eyes absent; head immersed in pereonite 1 with posterior margin appearing deeply concave; pereon with coxae 4–7 produced beyond posterior margins of their respective pereonites, at least 2 or more visible in dorsal view; lateral margins of pleonite 5 obscured by pleonite 4 (Fig. 7G) | Natatolanacaliforniensis |

| – | Eyes present; posterior margin of head not appearing distinctly concave; with or without dorsally visible coxae on pereonites; lateral margins of pleonite 5 may or may not be obscured by pleonite 4 | 3 |

| 3 | Coxae of pereonites 2–7 well-developed, typically visible in dorsal view and expanded laterally with acute posterior angles; epimeres of pleonites 2–5 well-developed, expanded laterally, with acute posterior angles; pleotelson with squarish to pointed posterior margin and a strong, middorsal longitudinal ridge; margins of pleotelson and uropodal rami notched (Fig. 7F) | Metacirolanajoanneae |

| – | Pereonites, pleonites, pleotelson and uropods not as above | 4 |

| 4 | Head with prominent spatulate rostral process separating left and right antennules (Fig. 7D, E) | 5 |

| – | Head without a prominent rostral process between antennules | 6 |

| 5 | Posterior margin of pleotelson broadly rounded and crenulate; antennular peduncle articles 2 and 3 subequal in length (Fig. 7E) | Excirolanalinguifrons |

| – | Posterior margin of pleotelson obtusely rounded and acuminate; antennular peduncle article 3 longer than article 2 (Fig. 7D) | Excirolanachiltoni |

| 6 | Antennules geniculated, with peduncle article 1 longer than articles 2 or 3, and article 2 arising at right angles to article 1; peduncle of antennae with 4 articles, antennae long and extending beyond pereonite 7; lateral margins of pleonite 5 not obscured by pleonite 4; uropodal rami truncate distally, exopod does not extend to posterior margin of pleotelson (Fig. 7C) | Eurydicecaudata |

| – | Antennules not geniculated; peduncle of antennae with 5 articles; lateral margins of pleonite 5 obscured by pleonite 4; uropodal rami distally rounded or acuminate, extending beyond posterior of pleotelson | 7 |

| 7 | Uropodal rami with apical notches and not distally rounded; peduncle articles 1 and 2 of antennules fused; coxae of pereonites 5–7 visible dorsally; pereonites, pleonites and pleotelson without dorsal tubercles, carina, or setae (Fig. 7A) | Cirolanadiminuta |

| – | Uropodal rami rounded distally, without notches; peduncle articles 1 and 2 of antennules not fused; coxae visible dorsally on pereonites 2–7; pleonites 3–5 with row of small tubercles on posterior margins; pleotelson of adult males with two large dorsal submedian tubercles or carinae (Fig. 7B) | Cirolanaharfordi |

| 8 | Pereopods 4–7 ambulatory (dactylus shorter than propodus) | 9 |

| – | Pereopods 4–7 prehensile (dactylus generally as long as, or longer than propodus and strongly curved); adults parasitic on fishes | 19 [Cymothoidae] |

| 9 | Dorsal surface of pleon tuberculate, with small to medium tubercles present on posterior margins of at least pleonites 3–5 | 10 |

| – | Dorsal surface of pleon without tubercles | 13 [Aegidae] |

| 10 | Pleotelson dorsally setose, lateral margins with single incision | 11 [Corallanidae] |

| – | Pleotelson not dorsally setose, lateral margins without incisions | 12 [Tridentellidae] |

| 11 | Male head with 3 large horns or tubercles, including 1 rostral and 2 posterolateral between the eyes (female without tubercles); pereonites 2–7 without dorsal setae or tubercles; pleotelson subtriangular with rounded apex, dorsal surface setose except for median longitudinal area (Fig. 8A) | Excorallanatricornisoccidentalis |

| – | Head of both males and females without horns or tubercles; pereonites 4–7 with dorsal setae and row of small tubercles on posterior margin; pleotelson triangular with subacute apex, entire dorsal surface densely covered with bifid golden setae (Fig. 8B) | Excorallanatruncata |

| 12 | Body dorsal surface sculptured with low or small tubercles; head of male with 5 low tubercles, including 1 rostral, 1 pair near anterior margin, and 1 pair near posterior margin; male pereonite 1 with 2 small, median tubercles near anterior margin; female lacking tubercles on head and pereon; pleonites 3–5 with small tubercles on posterior margins; pleotelson minutely tuberculate dorsally with widely rounded, slightly crenulate posterior margin (Fig. 8D) | Tridentellaquinicornis |

| – | Body dorsal surface sculptured with large processes and numerous tubercles; male head with 2 dorsal posterolateral horns, frontal margin produced into large, upturned process and smaller ventrally projecting rostrum; pereonite 1 with 3 large dorsal processes; all pereonites and pleonites with numerous dorsal tubercles that increase in size and become more spine-like posteriorly; pleotelson triangular with subtruncate apex, dorsally covered with longitudinal rows of large, spine-like tubercles; females much less spinose than males, lacking large processes on head and pereonite 1 (Fig. 8C) | Tridentellaglutacantha |

| 13 | Peduncular articles 1 and 2 of antennules greatly expanded (dilated), article 2 with gradual distal process extending 25–50% the distance into article 3; posterior margin of pleotelson truncate, crenulated and fringed with setae (Fig. 8E) | Aegalecontii |

| – | Peduncular articles of antennules not dilated, article 2 without distal process; posterior margin of pleotelson rounded or subacuminate | 14 |

| 14 | Eyes large, close-set, nearly touching at midline; pleotelson shield-shaped with subacuminate apex and weekly serrated (notched) posterolateral margins; uropodal rami ovate with subacuminate apices (Fig. 8F)Endnote 3 | Aegiochusplebeia |

| – | Eyes medium to large, but distinctly separated and not nearly touching medially; posterior margin of pleotelson rounded; uropodal rami with broadly rounded to truncate apices | 15 |

| 15 | Medial process of uropodal peduncle very long, extending at least 75% of length of endopod | 16 |

| – | Medial process of uropodal peduncle extends 50% or less of length of endopod | 17 |

| 16 | Propodi of pereopods 1–3 with large, broad, spine-bearing medial lobe; dactyli of pereopods 1–3 longer than propodi; frontal lamina broadly expanded anteriorly, arrowhead or spatulate shaped (Fig. 9B) | Rocinelabelliceps |

| – | Propodi of pereopods 1–3 without expanded medial lobe; dactyli of pereopods 1–3 subequal in length to propodi; frontal lamina thin and narrow (Fig. 9E) | Rocinelasignata |

| 17 | Medial process of uropodal peduncle extends < 40% of length of endopod; propodi of pereopods 1–3 with 4 stout, recurved acute spines; merus of pereopods 1–3 with 5–8 acute spines (3–5 distal, 2 or 3 proximal) (Fig. 9A) | Rocinelaangustata |

| – | Medial process of uropodal peduncle extends ~ 50% of length of endopod; propodi of pereopods 1–3 with 4–6 acute spines; merus of pereopods 1–3 with 4 acute spines (3 distal, 1 proximal) | 18 |

| 18 | Propodi of pereopods 1–3 with 5 thin, straight acute spines; apical article of maxillipedal palp with thin, nearly straight, acute spines (Fig. 9C) | Rocinelalaticauda |

| – | Propodi of pereopods 1–3 with 4–6 stout and recurved acute spines; apical article of maxillipedal palp with stout, recurved acute spines (Fig. 9D) | Rocinelamurilloi |

| 19 | Pleopods and uropods not setose | 20 |

| – | Pleopods and uropods heavily setose, adapted for swimming (juvenile cymothoids)Endnote 4 | unidentified Cymothoidae |

| 20 | Body very broad and darkly pigmented; pereon at least 2× as wide as pleon with strongly convex lateral margins (widest at pereonite 5); parasite of barspot cardinalfish and Panamic fanged blenny in Eastern Pacific (Fig. 10A)Endnote 5 | Renocilathresherorum |

| – | Body not as above | 21 |

| 21 | Posterior margin of head weakly to strongly trisinuate; pleon not immersed in pereon | 22 |

| – | Posterior margin of head not trisinuate; pleon partially immersed in pereon | 23 |

| 22 | Head not immersed in pereonite 1, posterior border distinctly trisinuate; coxal margins of all or just posterior pereonites with acute or subacute posterolateral angles, coxae may be held close to body (acuminata form) or greatly expanded laterally (aster form); uropods visible dorsally, extending clearly beyond posterior border of pleotelson; parasite of ~ 40 different species of fishes (Fig. 10B) | Nerocilaacuminata |

| – | Head somewhat immersed in pereonite 1, subquadrate anteriorly with weakly trisinuate posterior border; uropods not visible in dorsal view, typically held concealed under pleotelson and not extending beyond posterior border; parasite of Pacific bumper, pompanos, serranos, carangids, and other fishes (Fig. 10C) | Smenispaconvexa |

| 23 | Basal articles of antennules expanded and touching or nearly touching | 24 |

| – | Basal articles of antennules not expanded and touching | 25 |

| 24 | Pereopods 4–7 carinate; posterior margin of pleonite 5 trisinuate except in occasional males; parasite of pelagic fishes, including striped mullet off southern California and pompanos and herring off Baja California (Fig. 11A)Endnote 6 | Ceratothoagaudichaudii |

| – | Pereopods 4–7 not carinate; posterior margin of pleonite 5 smooth, not trisinuate; parasite of mullets and flatfish (Fig. 11B) | Ceratothoagilberti |

| 25 | Antennules longer than antennae; parasite of California and skipper halfbeaks (Fig. 10D) | Mothocyarosea |

| – | Antennules shorter than antennae | 26 |

| 26 | Frontal margin of head broadly rounded or truncate (not produced); bases of pereopods 4–7 with distinct carinae; coxae of pereonites 6 and 7 extending to and usually beyond posterior edge of respective pereonites; pleotelson in adult females nearly 2× as wide as long; parasite of at least 30 species of fishes (Fig. 11E) | Elthusavulgaris |

| – | Frontal margin of head produced; bases of posterior pereopods of females without distinct carinae; coxae of pereonites 6 and 7 not reaching posterior margins of respective pereonites; pleotelson in adult females either as wide as or wider than long | 27 |

| 27 | Merus and carpus of pereopod 4 expanded; bases of pleopods with well-developed accessory lamellae; pleotelson in adult females broadly rounded, ~ 1.5–2.0 × wider than long; males with coxal carinae on pereopods 4–7; parasite of wooly sculpin, northern clingfish, and reef finspot (Fig. 11D) | Elthusamenziesi |

| – | Merus and carpus of pereopod 4 not expanded; accessory lamellae of pleopodal bases not well developed; pleotelson in adult females ca. as wide as long; males without carinae on posterior pereopods; parasite of surfperch, smelt, gobies, killifish, and grunion (Fig. 11C) | Elthusacalifornica |

Figure 8.

Isopoda, Cymothoida, Cymothooidea, Corallanidae: AExcorallanatricornisoccidentalis (after Delaney 1984) BExcorallanatruncata (after Delaney 1984). Tridentellidae: CTridentellaglutacantha (after Delaney and Brusca 1985) DTridentellaquinicornis (after Delaney and Brusca 1985). Aegidae (in part): EAegalecontii (after Schultz 1969) FAegiochusplebeia (after Brusca 1983a).

Figure 9.

Isopoda, Cymothoida, Cymothooidea, Aegidae (in part): ARocinelaangustata (after Brusca and France 1992) BRocinelabelliceps (after Brusca and France 1992) CRocinelalaticauda (after Brusca and France 1992) DRocinelamurilloi (after Brusca and Iverson 1985; Brusca and France 1992) ERocinelasignata (after Brusca and Iverson 1985; Brusca and France 1992) A1–E1 = pereopods 3 A2–E2 = uropods with medial process of peduncle indicated by arrows.

Figure 10.

Isopoda, Cymothoida, Cymothooidea, Cymothoidae (in part): ARenocilathresherorum (after Brusca 1981) BNerocilaacuminata (after Brusca and Iverson 1985) CSmenispaconvexa (after Brusca 1981) DMothocyarosea (after Brusca et al. 2007).

Key D. Suborder Cymothoida, Superfamily Cymothooidea (in part): Family Gnathiidae

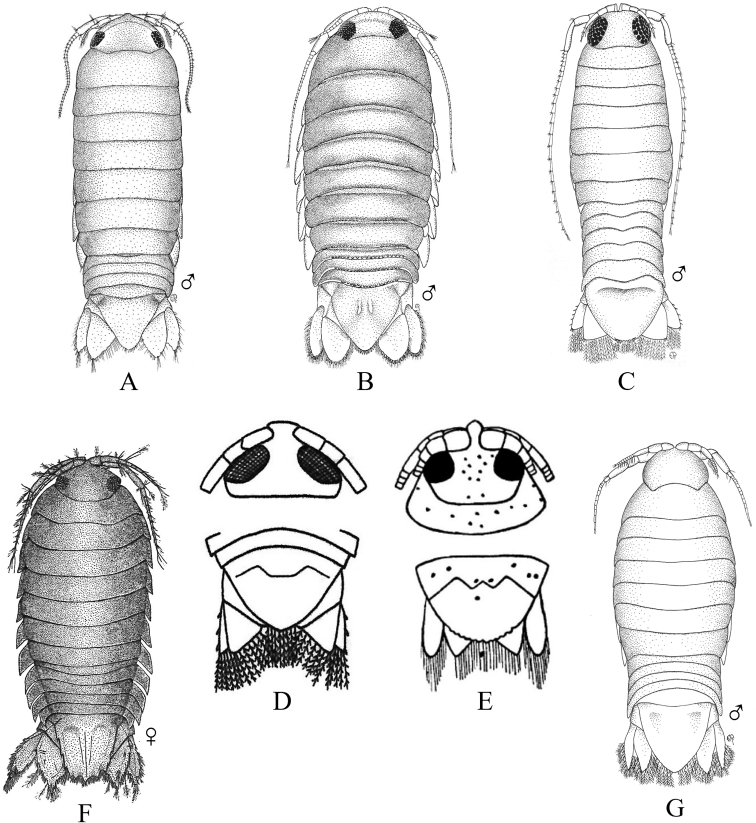

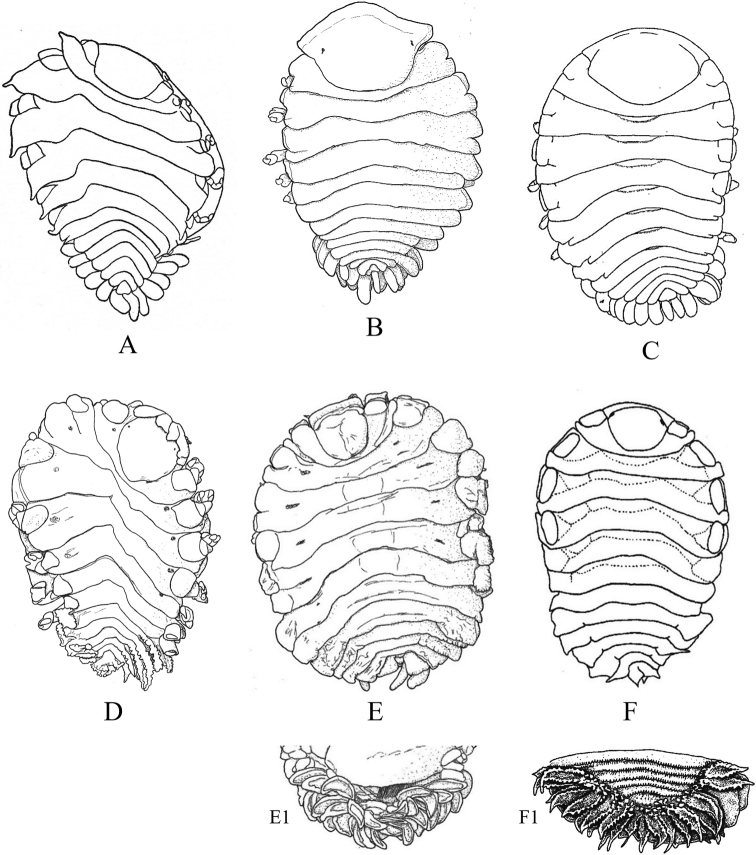

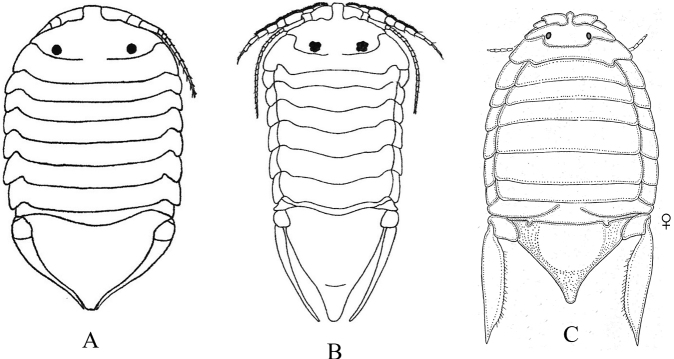

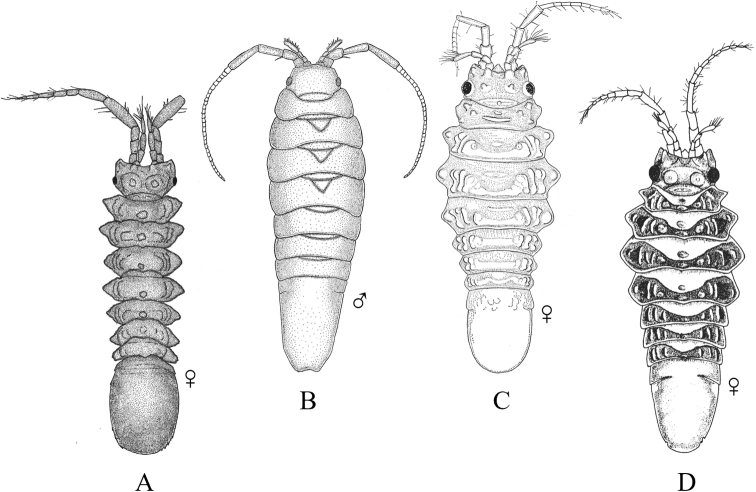

Fig. 12

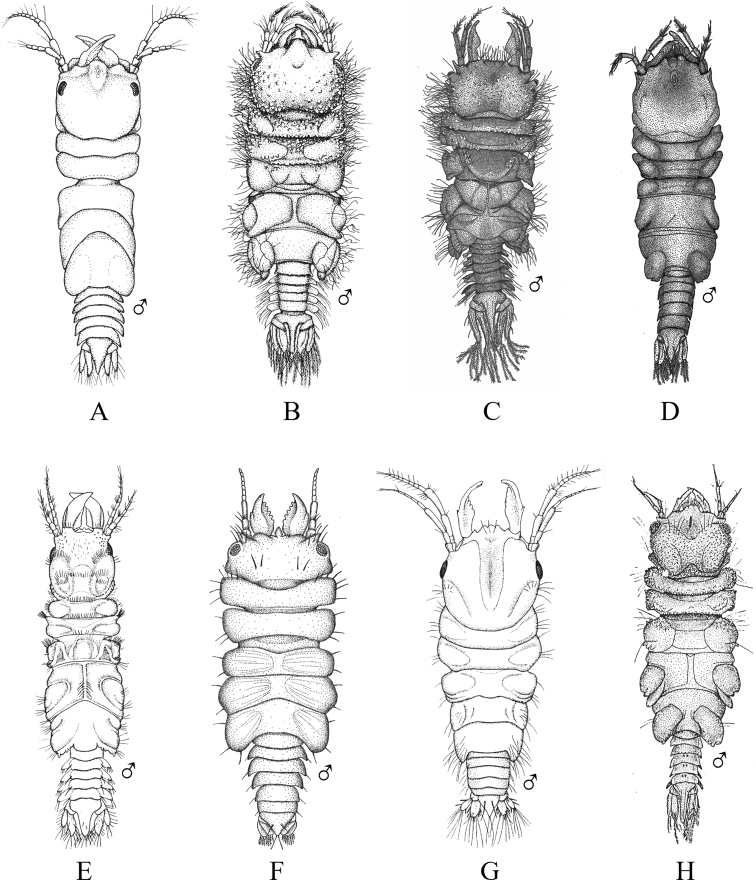

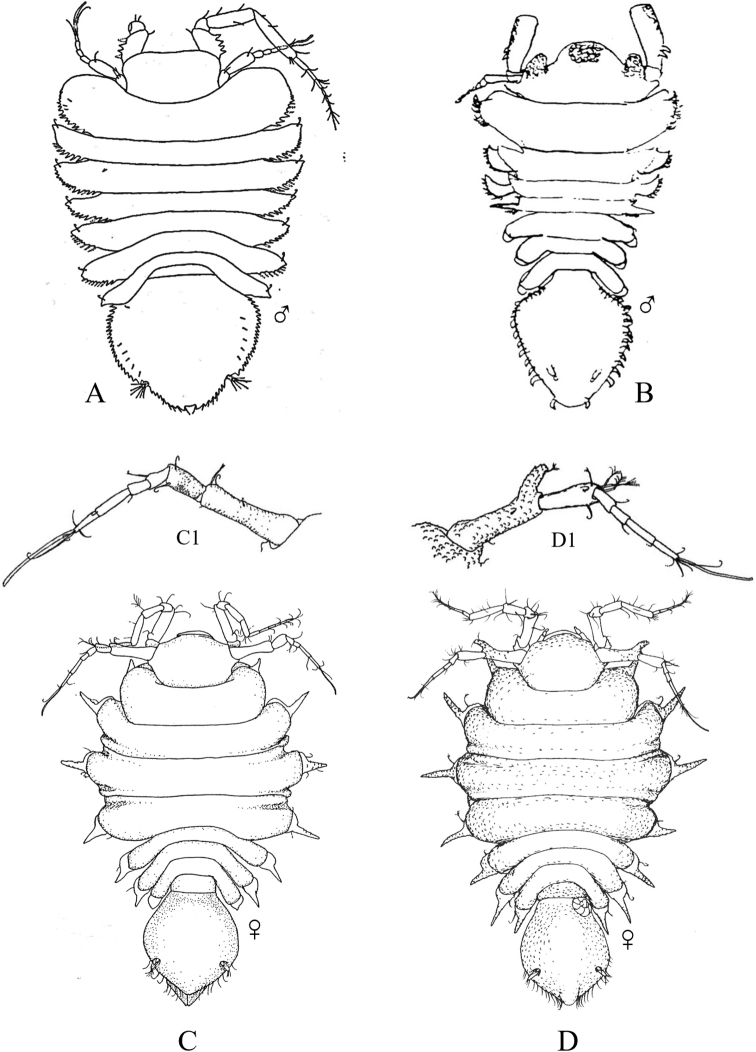

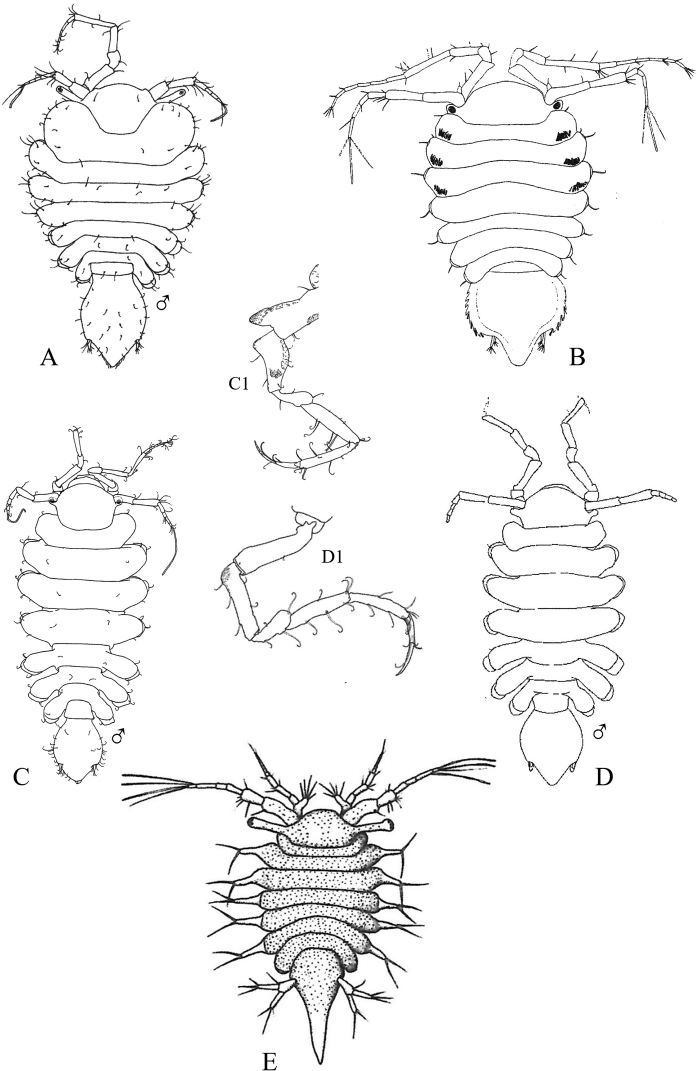

Figure 12.

Isopoda, Cymothoida, Cymothooidea, Gnathiidae: ACaecognathiacrenulatifrons (after Wetzer and Brusca 1997) BCaecognathiasanctaecrucis (after Wetzer and Brusca 1997) CGnathiaclementensis (after Schultz 1966) DGnathiacoronadoensis (after Schultz 1966) EGnathiaproductatridens (after Wetzer and Brusca 1997) FGnathiasteveni (after Menzies 1962a) GGnathiatridens (after Wetzer and Brusca 1997) HGnathiatrilobata (after Schultz 1966).

| 1 | Head with enlarged forceps-like mandibles projecting anteriorly (male gnathiids) | 2 |

| – | Head not as above, without projecting mandibles; body often sac-like (female and juvenile gnathiids)Endnote 7 | Gnathiidae spp. |

| 2 | Eyes present, with or without pigment; telson variable in shape | 3 |

| – | Eyes absent; frontal margin of head (frons) with 3 central processes, laterals larger than middle process; epimeres single, dorsal, laterally projected; telson distinctly triangular (Fig. 12D) | Gnathiacoronadoensis |

| 3 | Pleotelson distinctly triangular | 4 |

| – | Pleotelson arrowhead or T-shaped with base expanded | 8 |

| 4 | Pleonal epimeres laterally expanded, highly visible; body with few to numerous setae | 5 |

| – | Pleonal epimeres not laterally expanded, barely visible; body with relatively few setae | 7 |

| 5 | Frontal margin of head forming broad, transverse, minutely crenulated plate (best viewed ventrally); eyes brown to reddish brown; body setosity light, without numerous setae; pleopods without setae (Fig. 12A) | Caecognathiacrenulatifrons |

| – | Frontal margin of head not transverse (lobes or processes present); eyes reddish brown; body not hirsute, but with numerous setae; pleopods with setae | 6 |

| 6 | Body mottled with brown pigment; frontal margin of head forming centrally extended narrow lobe with crenulations; mandibles split into 2 articlesEndnote 8 | Caecognathia sp. A |

| – | Body without pigment; frontal margin of head trilobed with 3 central subequal processes; mandibles of single article only (not split into 2 articles) (Fig. 12G) | Gnathiatridens |

| 7 | Eyes dark brown, body mottled with brown pigment; frontal margin of head with 3 processes, median process largest and shaped as stepwise pyramid; head with setae and tuberculations (Fig. 12F) | Gnathiasteveni |

| – | Eyes reddish brown; body without pigmentation; frontal margin of head with central 3-dimensional expansion in shape of box, with 2 large setae extending outward centrally; head with setae, but lacking tuberculationsEndnote 8 | Gnathia sp. MBC1 |

| 8 | Pleotelson distinctly T-shaped | 9 |

| – | Pleotelson arrowhead-shaped | 10 |

| 9 | Eyes sessile, dark brown, lens with tuberculations; body speckled with tiny black dots; frontal margin of head produced into single large lobe; pleopods ovate, paddle-like; body hirsute (Fig. 12B) | Caecognathiasanctaecrucis |

| – | Eyes on distinct ocular peduncles, unpigmented, lens without tuberculations; frontal margin of head with 2 medium–large lateral processes and 4 central subequal processes; pleopods long and narrow; body hirsute (Fig. 12C) | Gnathiaclementensis |

| 10 | Pleonal epimeres double (dorsal and ventral); eyes golden/amber in color; frontal margin of head with 3 central, subequal processes; body with numerous scattered setae, but not hirsute (Fig. 12H) | Gnathiatrilobata |

| – | Pleonal epimeres single (dorsal only) | 11 |

| 11 | Eyes golden or amber in color; head with dorsal carina present; frontal margin of head as 1 broad truncate lobe with medial carina; body hirsuteEndnote 8 | Caecognathia sp. SD1 |

| – | Eyes with red and white checkerboard pattern; head without dorsal carina; frontal margin of head with 3 central subequal processes; body not hirsute, but with numerous setae (Fig. 12E) | Gnathiaproductatridens |

Key E. Suborder Cymothoida, Superfamilies Bopyroidea and Cryptoniscoidea

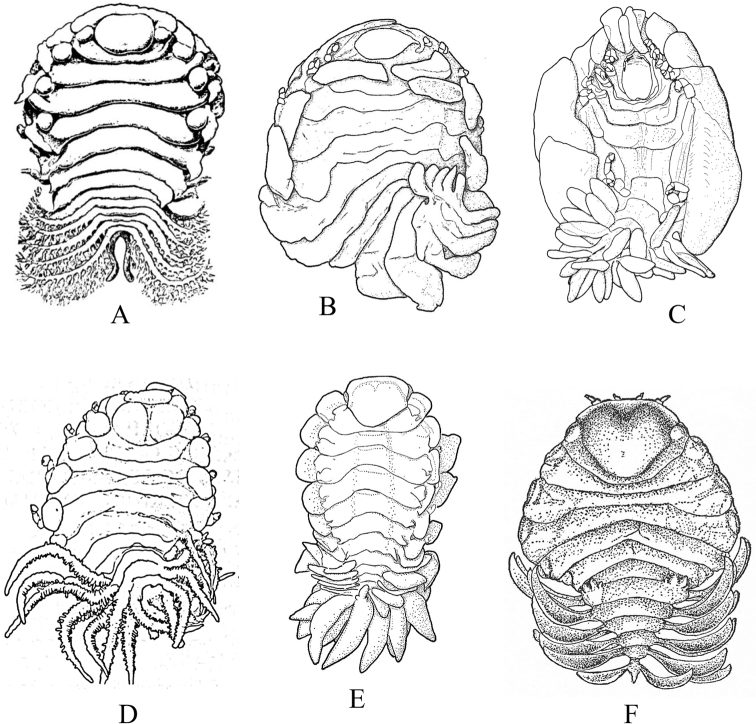

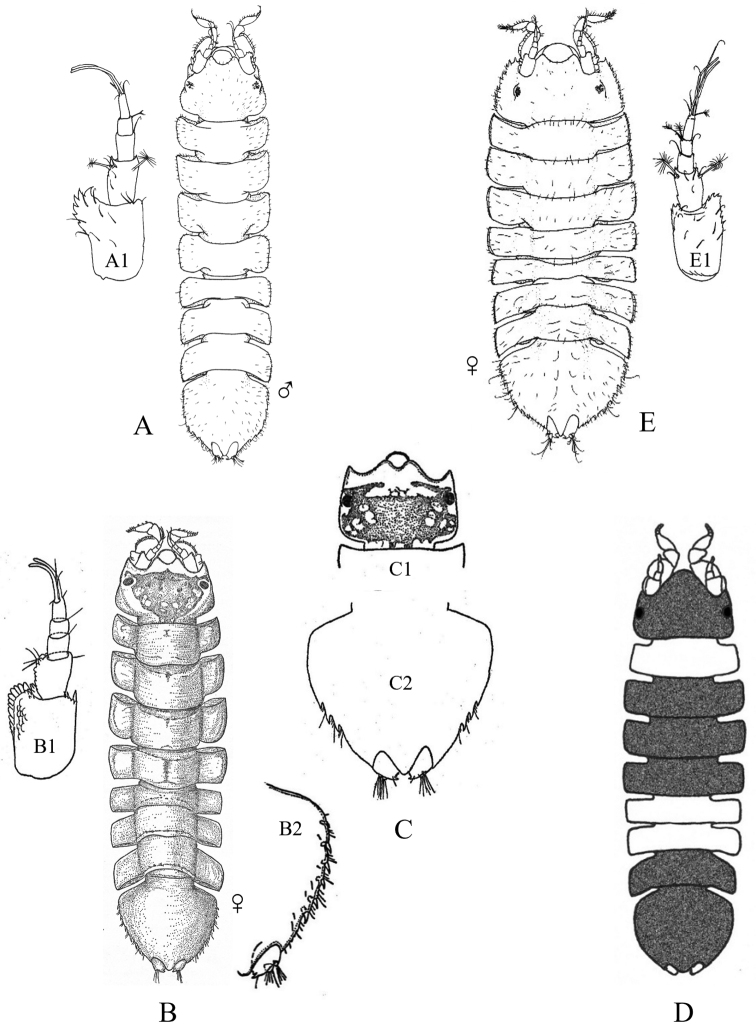

Figure 13.

Isopoda, Cymothoida, Epicaridea, Bopyroidea, Ionidae: AIonecornuta (after Richardson 1905a). Bopyridae (in part): BBathygygegrandis (after Markham 2016) CAnathelgeshyphalus (after Markham 1974a) DLeidyainfelix (after Markham 2002) EMunidionpleuroncodis (after Markham 1975); FPhyllodurusabdominalis (after Richardson 1905a).

Figure 16.

Isopoda, Cymothoida, Epicaridea, Cryptoniscoidea, Dajidae: AHolophryxusalaskensis (adult female) A1 dorsal view A2 ventral view (after Richardson 1905b) BZonophryxusprobisowa (adult female) B1 dorsal view B2 ventral view (Peruvian species = representative for unidentified SCB species of Zonophryxus; after Boyko and Williams 2021a). Hemioniscidae: CHemioniscusbalaniC1 adult female C2 juvenile female (after Nierstrasz and Brender à Brandis 1926; Williams and Boyko 2012).

| 1 | Body of adult female distinctly segmented with clear division of head (cephalon), thoracic (pereon), and abdominal (pleon) regions | 2 [Bopyridae and Ionidae] |

| – | Body of adult female sac-like, with at most weak segmentation visible | 18 [Dajidae and Hemioniscidae] |

| 2 | Adult female body broadly oval; pleon strongly torsioned and reflexed forward over pereon; head without eyes, deeply embedded in pereon, anterior margin covered by oostegites; pleomeres 3–6 fused medially; branchial parasite of deep-water crangonid shrimps of genus Glyphocrangon (Fig. 13B) | Bathygygegrandis |

| – | Female body not as above, pleon not strongly reflexed over pereon | 3 |

| 3 | Female pleon with pleopods and/or elongated lateral plates (epimeres or pleural lamellae) clearly noticeable in dorsal view | 4 |

| – | Female pleon without pleopods or elongated lateral plates noticeable in dorsal view | 12 |

| 4 | Lateral plates of pleon and/or pleopods conspicuously elongate, foliaceous, or lanceolate, with or without digitated or crenulated margins | 5 |

| – | Lateral plates of pleon and pleopods relatively short, distal margins of pleopods mostly rounded | 10 |

| 5 | Adult female with elongated lateral plates fringed with long, branched processes; branchial parasite of ghost shrimps of genus Neotrypaea (Fig. 13A) | Ionecornuta |

| – | Adult female with or without lateral plates, but lateral plates not as above if present | 6 |

| 6 | Adult female body nearly oval, with oostegites conspicuously visible dorsally arching over margins of head and pereon; head longer than wide, deeply immersed in pereon, eyes absent; pereomere 6 much longer than other pereomeres, pereomeres 1–5 concave anteriorly, pereomeres 6 and 7 concave posteriorly; pleon with “triramous appendages” in appearance, but each one consists of a foliaceous lanceolate lateral plate and identical biramous pleopod; branchial parasite of hermit crabs Parapagurodeslaurentae and P.makarovi (Fig. 13C) | Anathelgeshyphalus |

| – | Adult female body not as above, pereomere 6 subequal in length to other pereomeres; pleon with lateral plates and pleopods not appearing like triramous appendages | 7 |

| 7 | Adult females with pair of dorsolateral papillae on pleomere 1; pleon with long, narrow biramous pleopods arising from thin peduncle or stem on each segment, without lateral plates; head slightly wider than long, bilobate, eyes absent; abdominal parasite of mud shrimps of genus Upogebia (Fig. 13F) | Phyllodurusabdominalis |

| – | Adult females without dorsolateral papillae on pleomere 1; pleomeres with both elongated lateral plates and pleopods, but morphology of pleopods not as above | 8 |

| 8 | Pleon of adult females enclosed by tentacular-like, elongated lanceolate lateral plates and pleopodal exopods, each with deeply digitate margins, ventral surface covered partially by smaller foliate pleopodal endopods with crenulated margins; head completely embedded in pereon, dorsal surface divided into two large sub-oval lobes, eyes absent; branchial parasite of grapsid crab Pachygrapsuscrassipes (Fig. 13D) | Leidyainfelix |

| – | Pleon of adult females with lateral plates and pleopods not as above; head not bilobate | 9 |

| 9 | Adult female body ~ 2 × longer than wide, pyriform in shape; head slightly wider than long, eyes absent; coxal plates very large, overlapping, and extending well beyond lateral margins of pereomeres; pleon obscured by prominent ovate lateral plates and long, biramous lanceolate pleopods; branchial parasite of pelagic galatheid “red crab” Pleuroncodesplanipes (Fig. 13E) | Munidionpleuroncodis |

| – | Adult female body slightly longer than wide; head subcircular, eyes absent; coxal plates prominent but not widely extended on pereomeres 1–4; lateral edges on convex side of pereomeres 5–7 produced into slender points reflexed back over dorsum; pleomeres 1–5 with dentate-margined lanceolate lateral plates and similar biramous pleopods; branchial parasite of hermit crab Isochelespilosus (Fig. 14D) | Asymmetrioneambodistorta |

| 10 | Adult female head somewhat bilobate, eyes absent; pereomeres 1–6 with sharply pointed tergal projections on longer side of body; pleomeres 1–5 with short lateral plates and distally rounded uniramous pleopods; branchial parasite of several genera of crangonid and hippolytid shrimps (e.g., Crangon, Eualus) (Fig. 14A) | Argeiapugettensis |

| – | Adult females not as above; head not bilobate, with or without eyes; pereon without sharp tergal projections; pleopods biramous | 11 |

| 11 | Adult female head wider than long with rounded anterior and posterior margins, eyes absent; narrow and rudimentary coxal plates on pereomeres 3 and 4 on both sides of body; branchial parasite of porcelain crab Pachychelespubescens (Fig. 14C) | Aporobopyrusoviformis |

| – | Adult female head subtriangular in shape, anterolateral margins produced into small obtuse projections, eyes present; rudimentary coxal plates of pereomeres 3 and 4 only on longer side of body; branchial parasite of porcelain crabs Pachycheles spp. (Fig. 14B) | Aporobopyrusmuguensis |

| 12 | Adult female body oval to broadly oval, pereon and pleon subequal in width; branchial parasite of mud shrimps of genus Upogebia | 13 |

| – | Adult female body not oval, pleon tapering to much narrower than widest pereomeres | 14 |

| 13 | Adult female body broadly oval, almost as wide as long (L:W ratio ~ 1.2); head almost square, deeply embedded in pereomere 1, eyes absent; ventral surface of pleomeres covered by overlapping lanceolate lateral plates and uniramous uropods, middle region covered by similar sized biramous pleopods (Fig. 14E) | Orthionegriffenis |

| – | Adult female body oval, distinctly longer than wide (L:W ratio ~ 1.5); head slightly wider anteriorly than posteriorly, deeply embedded in pereomere 1, eyes present; ventral surface of pleomeres covered by numerous ridges and lanceolate biramous, marginally tuberculate pleopods (Fig. 14F) | Progebiophilusbruscai |

| 14 | Pleon of adult females composed of 5 medially fused pleomeres and pleotelson, the latter deeply arcuate and embedded in pleomere 5; head roughly triangular, separated from pereon by deep groove, eyes absent; branchial parasite of hippolytid shrimps Hippolytecaliforniensis and Thoralgicola (Fig. 15E) | Schizobopyrinastriata |

| – | Adult female body not as above; pleomeres distinctly separate, not medially fused; head with or without eyes | 15 |

| 15 | Head of adult female partially fused with pereomere 1 and separated by only short lateral notches; frontal margin of head slightly sinuated with anterolateral process usually on just short side of body, small eyes present; pleotelson entirely set within curves of pleomere 5; branchial parasite of snapping shrimps Alpheopsisequidactylus and Synalpheuslockingtoni (Fig. 15A) | Bopyrellacalmani |

| – | Female head distinctly separate and not fused with pereomere 1, eyes absent; pleotelson not completely set within curves of pleomere 5 | 16 |

| 16 | Head of adult female squarish with distinct anterolateral horns and a small anteromedial indentation; pleon with 6 distinct pleomeres separated by deep lateral notches; pleopods 1–4 biramous (5th pair absent), uropods absent; branchial parasite of alpheid shrimp Automate sp. A (Fig. 15B)Endnote 9 | Capitetragonia sp. A |

| – | Female head wider anteriorly than posteriorly, without anterolateral horns; pleon with 5 pleomeres not separated by deep notches and very small 6th segment, 5 pairs of biramous pleopods, and terminal pair of lanceolate uropods | 17 |

| 17 | Endopods of pleopods 1–5 much larger than exopods, elongate and pointed, surface rough with irregular rugae; coxal plates of pereomeres 5–7 not developed as lamellae; branchial parasite of hermit crabs of genus Pagurus (Fig. 15C)Endnote 10 | Eremitionegiardi |

| – | Endopods of pleopods 1–5 only slightly larger than exopods, triangular or ovate, surface smooth; coxal plates of pereomeres 5–7 developed as lamellae; branchial parasite of squat lobsters Galacanthadiomedeae and Munidaquadrispina in the East Pacific (Fig. 15D) | Pseudionegalacanthae |

| 18 | Adult female body simply an egg sac, without evidence of segmentation; antennae and mouthparts absent; parasite on barnacles of genera Balanus and Chthamalus (Fig. 16C) | Hemioniscusbalani [Hemioniscidae] |

| – | Adult female body with weak evidence of segmentation visible dorsally or laterally; antennae and mouthparts present; parasitic on caridean shrimp of families Pasiphaeidae and Pandalidae | 19 [Dajidae] |

| 19 | Adult female body typically elongate and symmetrical, but may be irregular with deeper, stouter body in some specimens; head separate, typically hemispherical, visible dorsally or ventrally; segmentation of pereon usually visible laterally by 4 coxal plates; pleonal region posteriorly projected as unsegmented conical prominence; parasite on carapace of pasiphaeid shrimp Pasiphaeapacifica (Fig. 16A)Endnote 11 | Holophryxusalaskensis |

| – | Adult female body ovate, all regions fused and indistinct dorsally; posterior margin of pleon appears notched with row of triangularly shaped processes; parasite on carapace of pandalid shrimps Pantomusaffinis and Plesionikatrispinus (Fig. 16B)Endnote 12 | Zonophryxus sp. |

Figure 14.

Isopoda, Cymothoida, Epicaridea, Bopyroidea, Bopyridae (in part): AArgeiapugettensis (after Richardson 1905a) BAporobopyrusmuguensis (after Markham 2008) CAporobopyrusoviformis (after Shiino 1934) DAsymmetrioneambodistorta (after Markham 1985b) EOrthionegriffenisE1 ventral view of pleon and pleopods (after Markham 2004) FProgebiophilusbruscaiF1 ventral view of pleon and pleopods (after Campos and de Campos 1998).

Figure 15.

Isopoda, Cymothoida, Epicaridea, Bopyroidea, Bopyridae (in part): ABopyrellacalmani (after Sassaman et al. 1984) BCapitetragoniaalphei (Caribbean species = representative for Capitetragonia sp. A; after Markham 1985a) CEremitionegiardi (after Richardson 1905a) DPseudionegalacanthae (after Richardson 1905a) ESchizobopyrinastriata (after Campos and de Campos 1990).

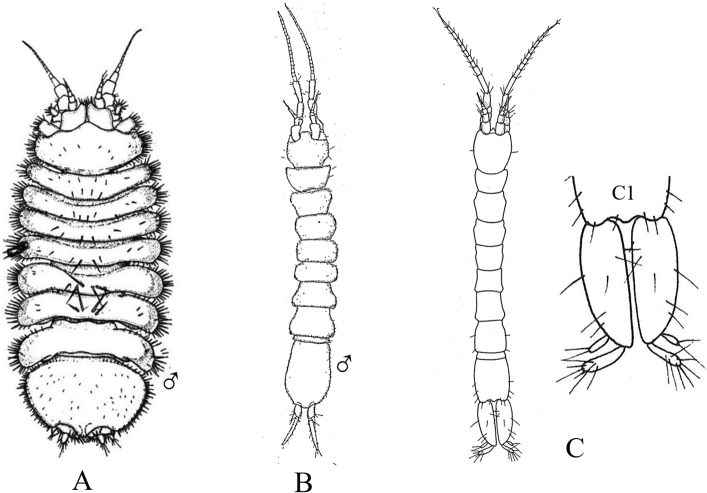

Key F. Suborder Limnoriidea, Superfamily Limnorioidea: Family Limnoriidae

Fig. 17

Figure 17.

Isopoda, Limnoriidea, Limnorioidea, Limnoriidae: ALimnoriaalgarum (after Menzies 1957) BLimnoriaquadripunctataB1 inner surface of left mandible showing “rasp” (after Menzies 1957) CLimnoriatripunctata (after Allen 1976).

| 1 | Dorsal surface of pleotelson without symmetrically arranged tubercles; left mandible without rasp or file-like ridges; burrowing in algal holdfasts (Fig. 17A) | Limnoriaalgarum |

| – | Dorsal surface of pleotelson with 3 or 4 symmetrically arranged anterior tubercles; left mandible with rasp or file-like ridges (see Fig. 17B); burrowing in wood | 2 |

| 2 | Dorsal surface of pleotelson with 3 anterior tubercles arranged in triangle; lateral and posterior margins of pleotelson tuberculate (Fig. 17C) | Limnoriatripunctata |

| – | Dorsal surface of pleotelson with 2 pairs of anterior tubercles; margins of pleotelson not tuberculate (Fig. 17B) | Limnoriaquadripunctata |

Key G. Suborder Sphaeromatidea, Superfamilies Seroloidea and Sphaeromatoidea

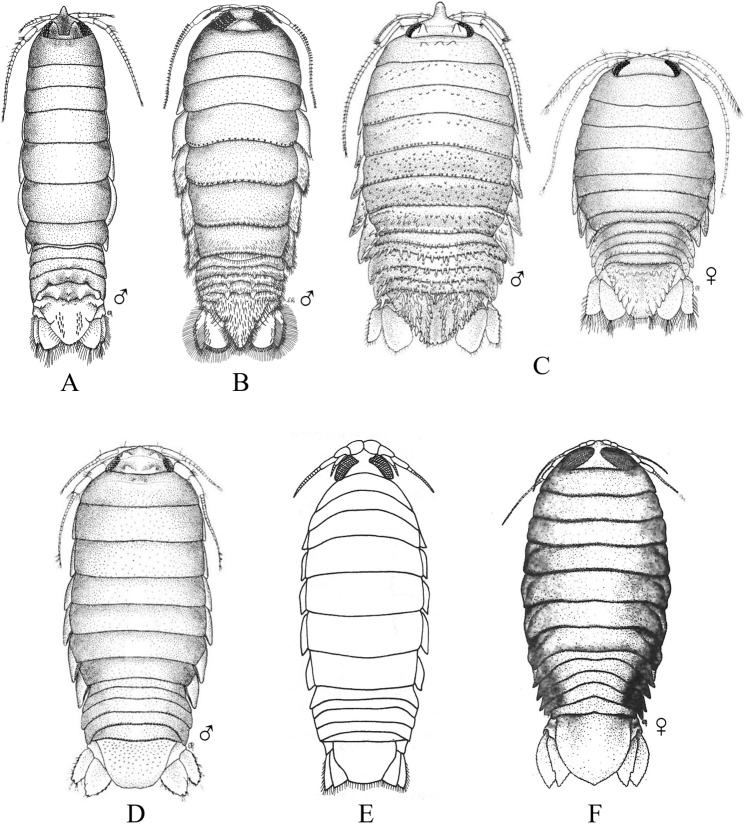

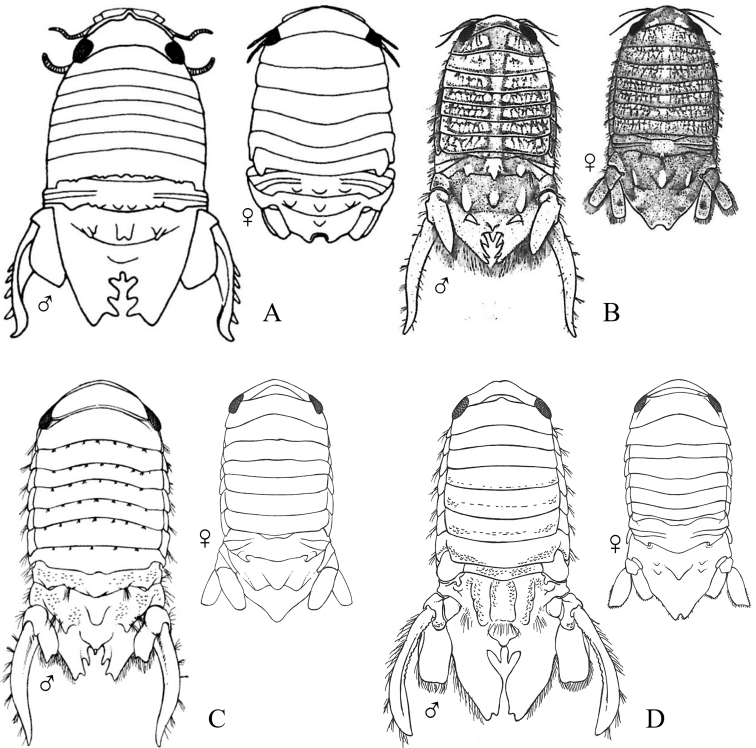

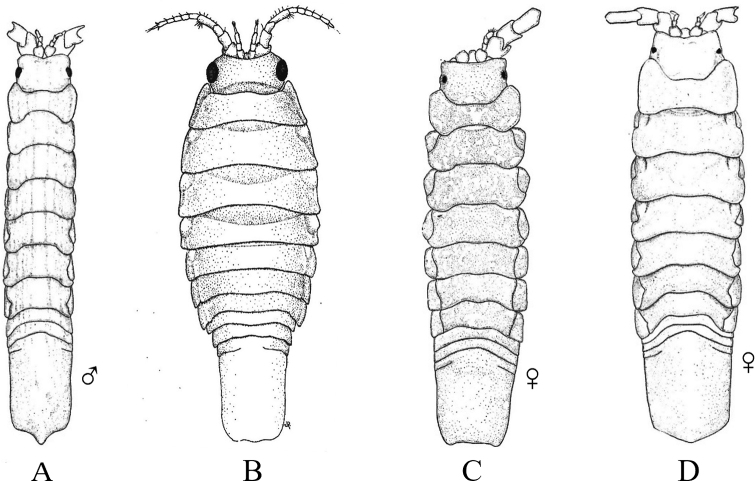

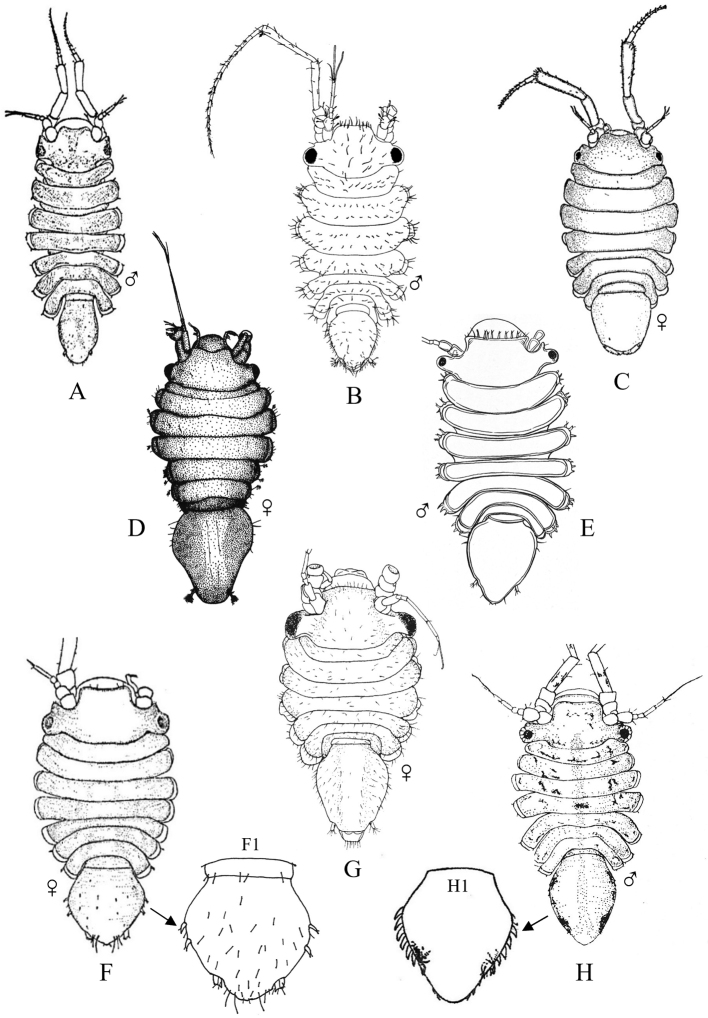

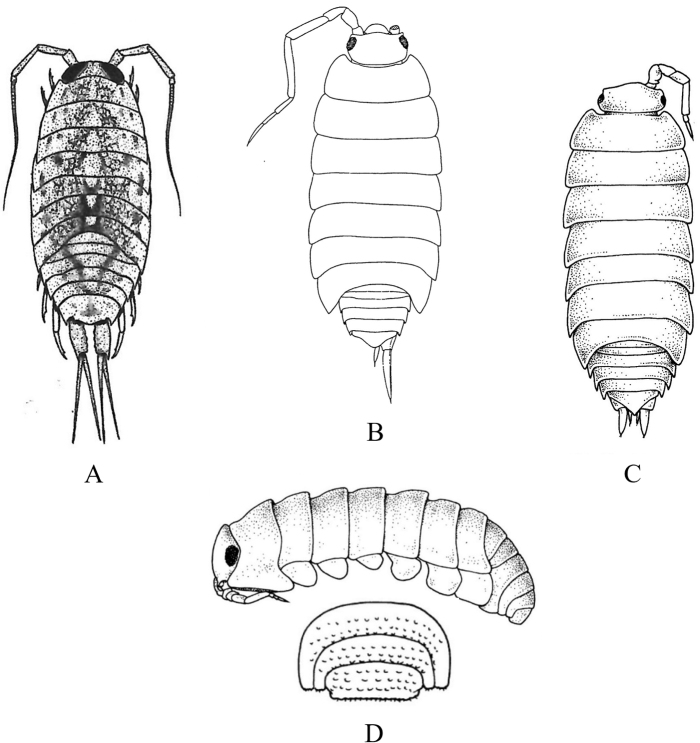

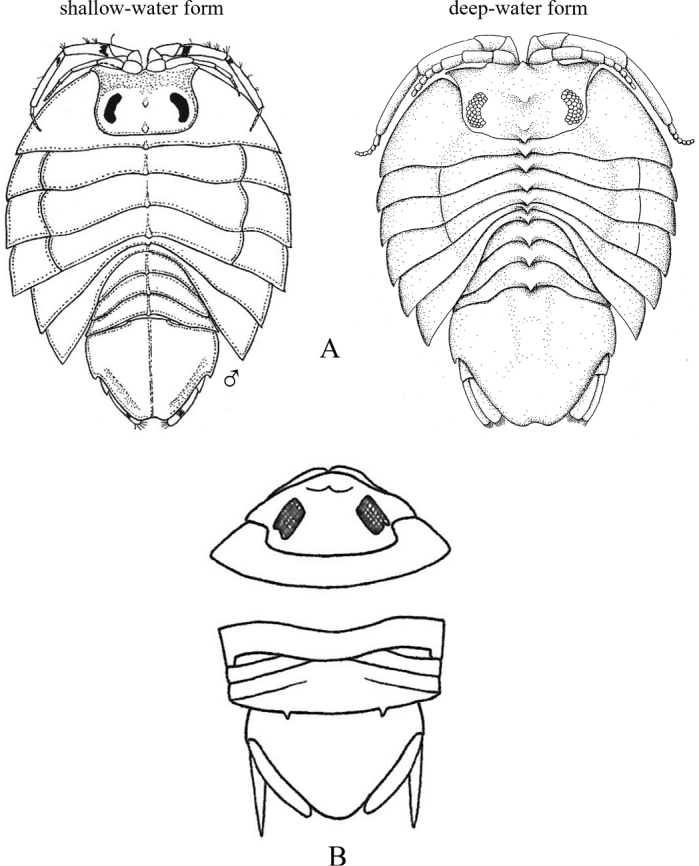

Figure 18.

Isopoda, Sphaeromatidea, Seroloidea, Serolidae: AHeteroseroliscarinata (shallow-water form after Menzies and Barnard 1959; deep-water form after Wetzer and Brusca 1997). Tecticipitidae: BTecticepsconvexus (after Richardson 1905a; Schultz 1969).

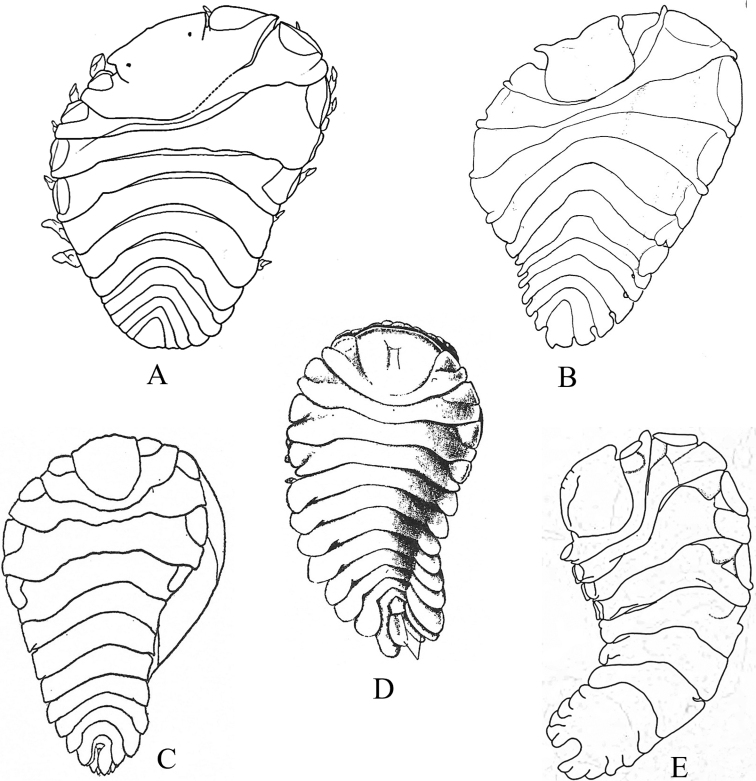

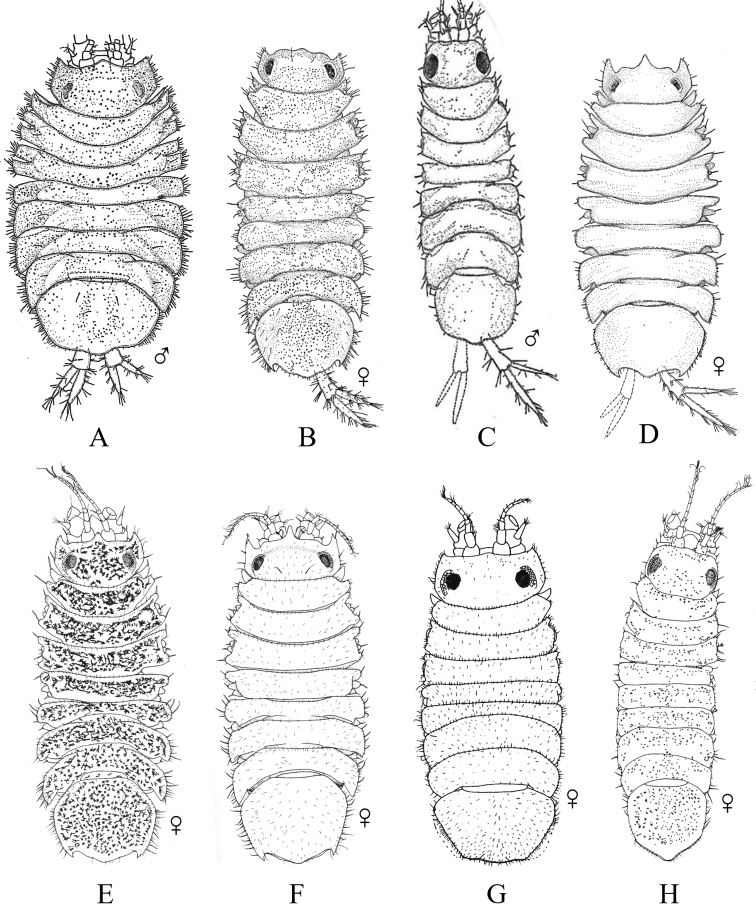

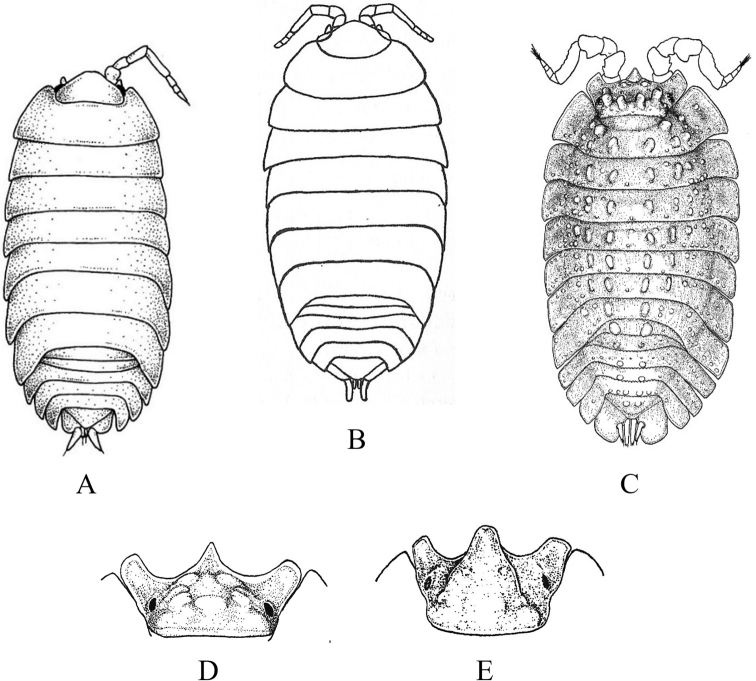

Figure 23.

Isopoda, Sphaeromatidea, Sphaeromatoidea, Sphaeromatidae (in part): AExosphaeromaamplicauda (after Wall et al. 2015) BExosphaeromaaphrodita (after Wall et al. 2015) CExosphaeromainornata (after Iverson 1982) DExosphaeromapentcheffi (after Wall et al. 2015) EExosphaeromarhomburum (after Richardson 1899, 1905a).

| 1 | Pleon composed of 3 free pleonites plus pleotelson; body broad, depressed and platter-like; dorsum with distinct medial carinae (Fig. 18A)Endnote 13 | Heteroseroliscarinata [Serolidae] |

| – | Pleon composed of 1 or 2 dorsally visible free pleonites plus pleotelson | 2 |

| 2 | Pereopod 1 subchelate in both sexes, with broadly expanded propodus and prehensile dactylus (propodus at least 5 × wider than dactylus); pereopod 2 prehensile only in males | 3 |

| – | Pereopod 1 ambulatory or only weakly prehensile, propodus narrow (propodus < 2 × as wide as dactylus) | 6 [Sphaeromatidae] |

| 3 | Head medially fused to pereonite 1; pleopod 5 with both rami lacking transverse pleats or folds; uropods uniramous, lacking exopods | 4 [Ancindae] |

| – | Head and pereonite 1 not fused; both rami of pleopod 5 with transverse pleats or folds; uropods biramous, exopods slender and spine-like; first segment of pleon with 3 suture lines (fused pleonites 1–4) and 2 small triangular processes on posterior margin; pleotelson with rounded posterior border (Fig. 18B) | Tecticepsconvexus [Tecticipitidae] |

| 4 | Lateral margins of head strongly produced; pleon with 2 short posterior projections overhanging anterior margin of pleotelson; pleopod 1 biramous; uropodal ramus narrow proximally, then expands at least twofold for ~ 80% of length before tapering to acute point (Fig. 19C) | Bathycopeadaltonae |

| – | Lateral margins of head weakly produced; pleon without posterior projections; pleopod 1 uniramous; uropodal ramus styliform, widest proximally and tapering to an acute point | 5 |

| 5 | Body broad (L:W ratio ~ 1.7) with densely granulated surfaces; pereonite 1 narrower than pereonites 2–7; pleotelson inflated, distinctly wider than long with truncate apex; eyes slightly elevated on swellings; uropods strongly recurved distally (Fig. 19A)Endnote 14 | Ancinusgranulatus |

| – | Body relatively narrow (L:W ratio > 2.0) with smooth surfaces; pereonite 1 wider than pereonites 2–7; pleotelson not inflated, longer than wide with nearly acute or narrowly rounded apex; eyes not elevated; distal tips of uropods only slightly recurved (Fig. 19B)Endnote 14 | Ancinusseticomvus |

| 6 | Endopods of pleopods 4 and 5 without branchial pleats or folds | 7 |

| – | Endopods of pleopods 4 and 5 with branchial pleats or folds | 8 |

| 7 | In lateral view, anterior margins of coxal plates of pereonites 2–4 appear raised and posterior margins not raised, giving the coxae a somewhat S-shaped appearance; species is fully marine (Fig. 20B)Endnote 15 | Gnorimosphaeromaoregonense |

| – | In lateral view, anterior margins of coxal plates 2–4 are not raised, and coxae do not appear S-shaped; species occurs in brackish or freshwater habitats (Fig. 20A) | Gnorimosphaeromanoblei |

| 8 | Pleopods 4 and 5 with branchial pleats on both rami | 9 |

| – | Pleopods 4 and 5 with branchial pleats only on endopods | 19 |

| 9 | Uropods of male highly modified, each composed of elongated, cylindrical, or flattened exopod and very short endopod fused to the protopod; both uropodal rami lamellar in females; ovigerous females with 4 pairs of oostegites on pereonites 1–4 | 10 |

| – | Uropods lamellar in both sexes; ovigerous females with 3 pairs, 1 pair, or no pairs of oostegites | 14 |

| 10 | Pleotelson of males with pronounced posteromedial tooth that completely fills apical notch and extends posteriorly beyond level of notch opening; dorsum of pleotelson with 3 transverse elevations at base, median elevation terminating in a spine; body surface densely granulated; sexual dimorphism pronounced with female body smooth, lacking ornamentation or setae (Fig. 20C) | Discerceisgranulosa |

| – | Pleotelson of males with highly complex and open apical notch, internal lateral margins of notch with various numbers of teeth forming sinuses of different shapes; body surface not densely granulated; sexual dimorphism pronounced, females without complex pleotelsonic notch, terminal notch either very short and simple or absent; dorsum of pleotelson sculptured with various types of tubercles | 11 |

| 11 | Uropods of male with ventrolateral spines on exopods; female pleotelson stout, with 4 dorsal tubercles and wide, but shallow apical notch (Fig. 21A) | Paracerceiscordata |

| – | Uropods of male without spines; female pleotelson not as above | 12 |

| 12 | Pleotelson of males long, subequal in length to pereon, with complex medial sinus formed by 2 pairs of teeth, pleotelsonic sinus expanded basally into round foramen overhung by basal knob bearing tall acute spine (spine length ≥ 4 × diameter), sinus then narrowing distally to long thin channel; female pleotelson with small distal notch and 5 dorsal tubercles (1 large medial, 4 smaller lateral); female uropodal exopods with sharply toothed posteromedial margins (Fig. 21D) | Paracerceis sp. A |

| – | Pleotelson of males relatively short, ca. half length of pereon; pleotelsonic sinus not as above, without round basal foramen, with or without short spine overhanging base of notch; female uropodal exopods without sharply toothed margins | 13 |

| 13 | Male pleotelson with short acute spine (i.e., length subequal to diameter) on basal knob overhanging sinus, interior margins of sinus with 2 pairs of lateral teeth; pleotelson of female elongate, acuminate posteriorly, with 3 dorsal tubercles (Fig. 21C)Endnote 16 | Paracerceissculpta |

| – | Male pleotelson with large dorsal tubercle at base of sinus, interior margins of sinus with 3 pairs of sharp teeth; female pleotelson not as above (Fig. 21B) | Paracerceisgilliana |

| 14 | Pleotelson apex entire, upturned; dorsal surface of pleotelson with 2 pairs of prominent tubercles and numerous scattered small tubercles; female sculpturing less pronounced than males (see Bruce and Wetzer 2008: fig. 1) | Pseudosphaeroma sp. |

| – | Pleotelson without upturned apex, sculpturing not as above | 15 |

| 15 | Pleotelson of males with deeply slit apical notch or expanded foramen, notch may be reduced to small depression or dorsally visible slit in females; uropodal rami subequal in length, typically extending beyond posterior margin of pleotelson; ovigerous females with 1 or 3 pairs of oostegites | 16 |

| – | Pleotelson of males and females with shallow terminal notch; uropodal exopod shorter than endopod, rami not extending beyond posterior border of pleotelson; ovigerous females without oostegites | 17 |

| 16 | Pleotelsonic sinus (foramen) distinctly heart shaped with median point in males, but greatly reduced in females; dorsum of pleon with 2 rounded submedian tubercles just lateral to midline on pleonite 5, and 4 similarly spaced tubercles on pleotelson; uropodal rami with crenulated margins (at least in males) (Fig. 22B) | Paradelladianae |

| – | Pleotelsonic sinus long and narrow, with prominent rounded tubercle barely overhanging anterior base, sinus walls straight sided and finely crenulate; dorsal surface of pleotelson covered with small tubercles; uropodal rami without crenulated margins (Fig. 22A) | Dynoideselegans |

| 17 | Frontal margin of head produced as a quadrangular process; antennular articles 1 and 2 dilated; dorsal surface of pleotelson sculptured with 3 longitudinal ridges (Fig. 22C)Endnote 17 | Dynamenelladilatata |

| – | Frontal margin of head not produced; antennular articles not dilated; dorsal surface of pleotelson smooth or tuberculate | 18 |

| 18 | Dorsal surface of pleotelson with many tubercles (Fig. 22E) | Dynamenellasheareri |

| – | Dorsal surface of pleotelson smooth, without tubercles or ridges (Fig. 22D)Endnote 17 | Dynamenellaglabra |

| 19 | Uropodal exopods with distinctly serrated outer margins | 20 |

| – | Uropodal exopods with smooth or lightly crenulated outer margins | 21 |

| 20 | Dorsal surface of pleotelson lightly sculptured with 2 longitudinal rows of small tubercles, posterior margin with prominent transverse elevation (Fig. 20D) | Sphaeromaquoianum |

| – | Dorsal surface of pleotelson heavily sculptured with many longitudinal rows of small to large heavy tubercles, posterior margin without prominent transverse elevation (Fig. 20E) | Sphaeromawalkeri |