Abstract

There are several differences between younger and older adults with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). However, few studies have evaluated these differences. We analysed the pre-hospital time interval [symptom onset to first medical contact (FMC)], clinical characteristics, angiographic findings, and in-hospital mortality in patients aged ≤50 (group A) and 51–65 (group B) years hospitalised for ACS. We retrospectively collected data from 2010 consecutive patients hospitalised with ACS between 1 October 2018 and 31 October 2021 from a single-centre ACS registry. Groups A and B included 182 and 498 patients, respectively. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) was more common in group A than group B (62.6 and 45.6%, respectively; P < 0.001). The median time from symptom onset to FMC in STEMI patients did not significantly differ between groups A and B [74 (40–198) and 96 (40–249) min, respectively; P = 0.369]. There was no difference in the rate of sub-acute STEMI (symptom onset to FMC > 24 h) between groups A and B (10.4% and 9.0%, respectively; P = 0.579). Among patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS), 41.8 and 50.2% of those in groups A and B, respectively, presented to the hospital within 24 h of symptom onset (P = 0.219). The prevalence of previous myocardial infarction was 19.2% in group A and 19.5% in group B (P = 1.00). Hypertension, diabetes, and peripheral arterial disease were more common in group B than group A. Active smoking was more common in group A than group B (67 and 54.2%, respectively; P = 0.021). Single-vessel disease was present in 52.2 and 37.1% of participants in groups A and B, respectively (P = 0.002). Proximal left anterior descending artery was more commonly the culprit lesion in group A compared with group B, irrespective of the ACS type (STEMI, 37.7 and 24.2%, respectively; P = 0.009; NSTE-ACS, 29.4 and 21%, respectively; P = 0.140). The hospital mortality rate for STEMI patients was 1.8 and 4.4% in groups A and B, respectively (P = 0.210), while for NSTE-ACS patients it was 2.9 and 2.6% in groups A and B, respectively (P = 0.873). No significant differences in pre-hospital delay were found between young (≤50 years) and middle-aged (51–65 years) patients with ACS. Although clinical characteristics and angiographic findings differ between young and middle-aged patients with ACS, the in-hospital mortality rate did not differ between the groups and was low for both of them.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndrome, Young adults, Symptom onset, First medical contact, Angiographic findings, In-hospital mortality

Introduction

The prevalence of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) among young adults is increasing.1–7 The time from symptom onset to treatment predicts the long-term outcomes of these patients.8–10 However, this time differs according to age.

In general, older patients (aged > 65 years) have longer pre-hospital delays compared with younger patients. However, previous studies have shown conflicting results, with some showing no age-related difference and others showing longer pre-hospital delays among younger compared with older patients.11–13

Although the clinical outcomes of older patients with ACS differ according to their clinical and angiographic characteristics, less is known about such differences in younger patients.11,13–16

We conducted a retrospective analysis of the difference in time from symptom onset to first medical contact (FMC), clinical and angiographic characteristics, and in-hospital outcome in younger (aged ≤50 years) and middle-aged (aged 51–65 years) patients hospitalised in a high-volume percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) centre in central Europe.

Methods

A prospective registry of consecutive ACS patients admitted to the University Hospital Královské Vinohrady Cardiocentre in Prague, Czech Republic, was created in September 2018 and has been described previously.17 We defined ACS based on the European Society of Cardiology guidelines for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and ACS without persistent ST elevation acute coronary syndrome [(non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS)].18,19 STEMI patients with a time between symptom onset and FMC [including the time spent performing an electrocardiogram (ECG)] > 24 h and typical features were considered to have sub-acute STEMI.

We retrospectively analysed the medical records and angiographic findings of patients aged 65 years diagnosed with ACS between 1 October 2018 and 31 October 2021. We calculated the time from symptom onset to FMC based on the time to first ECG in STEMI patients and time to first documented medical contact in NSTE-ACS patients. Patients with Takotsubo syndrome or missing basic anamnestic data were excluded.

Symptom onset was defined based on the anamnestic data as initial chest or epigastric pain or discomfort lasting ≥ 15 min. Patients were screened for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). We analysed the anamnestic data and previous symptoms reported by family members and/or bystanders to identify patients with OHCA as the first manifestation of ACS.

The time from symptom onset to FMC in STEMI patients was calculated (in min) for up to 24 h. NSTE-ACS patients were divided into six subgroups based on the time from symptom onset to FMC (<12 h, 12–24 h, 25–48 h, 49–72 h, 3–7 days, and >7 days).

The angiograms were independently re-evaluated and the culprit lesion was defined based on the ECG, echocardiographic, and angiographic findings. The SYNTAX score was used to identify the culprit vessel segments. In cases with an extended lesion, the proximal segment was selected. The severity of the lesion was estimated by visual inspection.

Patients were categorised into younger (group A; aged ≤ 50 years) and middle-aged (group B; aged 51–65 years) groups.20

We compared the pre-hospital time interval (symptom onset to FMC), clinical characteristics, angiographic findings, and in-hospital mortality between the groups.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations in figures and tables. Differences between the groups were tested using Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test. Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to detect differences in categorical variables between the groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Graphical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot (version 14.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The study registry included 2010 consecutive patients diagnosed with ACS during the 3-year study period. We further evaluated 182 patients aged ≤50 years (group A) and 498 patients aged 51–65 years (group B). Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics of the study participants. Non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome and its risk factors, such as diabetes, arterial hypertension, and peripheral arterial disease, were more common in group B than group A. Active smoking was more common in group A than group B.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Group A | Group B | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 182 (%) | n = 498 (%) | ||

| Age (mean) | 45.3 years | 58.8 years | |

| Male | 142 (78.0) | 401 (80.5) | 0.47 |

| Type of ACS | <0.0001 | ||

| STEMI | 114 (62.6) | 227 (45.6) | |

| NSTE-ACS | 68 (37.4) | 271 (54.4) | |

| Hypertension | 86 (47.3) | 300 (60.2) | 0.003 |

| Dyslipidemy | 59 (32.4) | 199 (40.0) | 0.075 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 2 (1.1) | 34 (6.9) | 0.002 |

| History of myocardial infarction | 35 (19.2) | 97 (19.5) | 1.00 |

| Pulmonary disease | 14 (7.7) | 54 (10.8) | 0.25 |

| Diabetes | 30 (16.5) | 131 (26.3) | 0.008 |

| Diet | 8 (4.4) | 23 (4.6) | |

| Oral anti-diabetics | 15 (8.2) | 78 (15.7) | |

| Insulin | 7 (3.8) | 30 (6.0) | |

| History of stroke | 3 (1.6) | 28 (5.6) | 0.035 |

| Smoking | 0.021 | ||

| Active | 122 (67) | 270 (54.2) | |

| Ex-smoker | 27 (14.8) | 98 (19.7) | |

| No. vessel disease | 0.002 | ||

| Single vessel | 95 (52.2) | 185 (37.1) | |

| Two vessel | 45 (24.7) | 156 (31.3) | |

| Three vessel | 42 (23.1) | 157 (31.5) | |

| Ejection fraction—mean % (standard deviation) | 49.2% (±10.3) | 48.6% (±11.1) | 0.257 |

| OHCA | 12 (6.6%) | 39 (7.8%) | 0.742 |

| Killip class | 0.065 | ||

| I | 167 (92.8) | 429 (86.1) | |

| II | 5 (2.8) | 33 (6.6) | |

| III | 1 (0.6) | 13 (2.6) | |

| IV | 7 (3.8) | 23 (4.6) |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; NSTE-ACS, non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction.

Interestingly, the frequency of previous myocardial infarction was comparable between groups A and B (19.2 and 19.5%, respectively; P = 1.00). Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest was similar between the groups (Table 1).

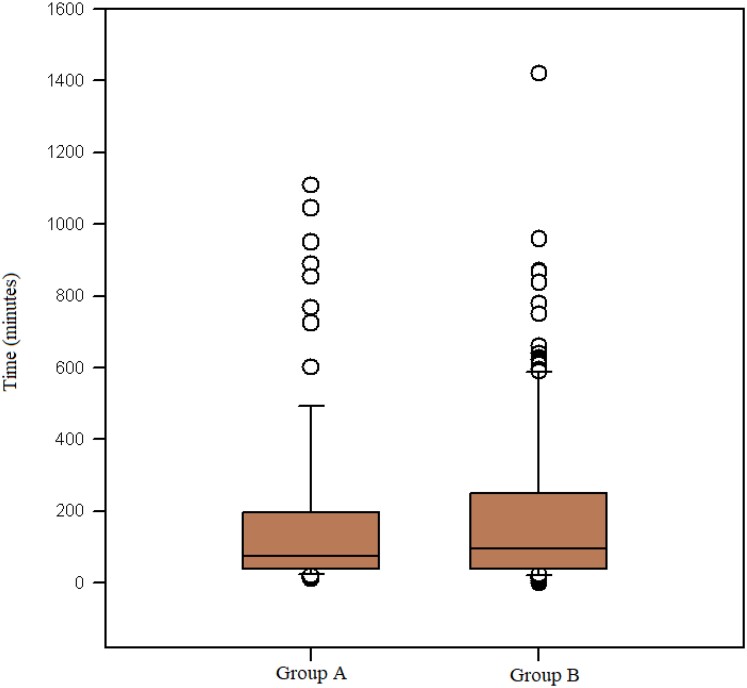

Time from symptom onset to first medical contact

For patients with acute STEMI, the median time from symptom onset to FMC was 74 (40–198) min in group A and 96 (40–249) min in group B (P = 0.369; Figure 1). The prevalence of sub-acute STEMI was similar between groups A (10.4%, n = 19) and B (9.0%, n = 45; P = 0.579).

Figure 1.

Symptoms onset to first medical contact in acute ST elevation myocardial infarction.

The time of symptom onset was unknown in 8.8% (n = 10) and 11% (n = 20) of patients in groups A and B, respectively. Similarly, 3.5% (n = 4) and 3.8% (n = 19) of patients with STEMI in groups A and B, respectively, presented with OHCA as the first manifestation of ACS without prior symptoms reported by family members and/or bystanders.

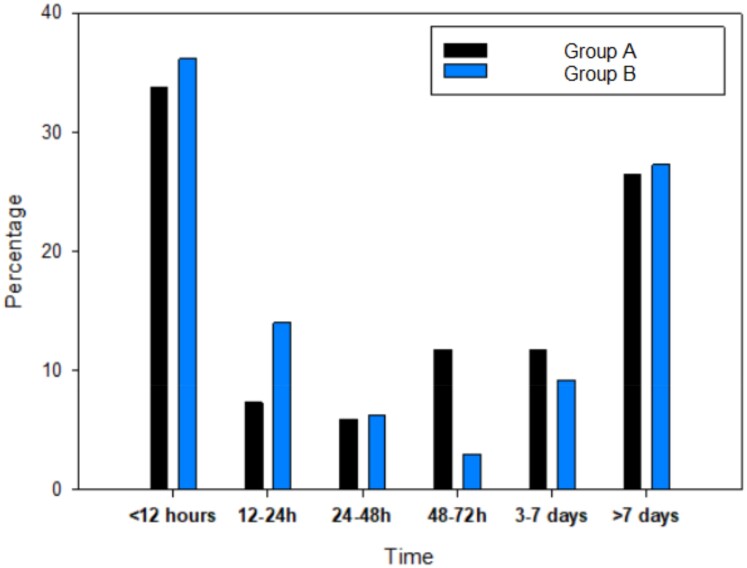

There were no differences in pre-hospital delay between NSTE-ACS patients. In groups A and B, 41.8% (n = 28) and 50.2% (n = 136) of patients, respectively, presented to the hospital within 24 h of symptom onset (P = 0.219). More detailed distribution of pre-hospital delay in NSTE-ACS patients is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Symptoms onset to first medical contact in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome.

Angiographic findings

Single-vessel disease was more common in group A than group B, as indicated in Table 1. The proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery was the culprit lesion for STEMI more often in younger than middle-aged patients [37.7% (n = 43) in group A and 24.2% (n = 55) in group B; P = 0.009], while there was no significant difference between younger and middle-aged patients with NSTE-ACS [29.4% (n = 20) in group A and 21.0% (n = 57) in group B; P = 0.140]. Table 2 presents detailed angiographic analysis of culprit segments according to participant age and ACS type.

Table 2.

Angiography characteristics of culprit lesions

| Type of ACS | STEMI | NSTE-ACS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Group B | Group A | Group B | |

| n = 114 (%) | n = 227 (%) | n = 68 (%) | n = 271 (%) | |

| Coronary segment | ||||

| ȃLeft main | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.8) | 1 (1.5) | 10 (3.7) |

| ȃProximal LAD | 43 (37.7) | 55 (24.2) | 20 (29.4) | 57 (21.0) |

| ȃMid-LAD | 9 (7.9) | 35 (15.4) | 6 (8.8) | 29 (10.7) |

| ȃDistal LAD | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (2.9) | 3 (1.1) |

| ȃFirst diagonal | 6 (5.3) | 8 (3.5) | 5 (7.4) | 17 (6.3) |

| ȃSecond diagonal | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) |

| ȃProximal Cx | 5 (4.4) | 11 (4.8) | 6 (8.8) | 29 (10.7) |

| ȃIntermediate | 1 (0.9) | 3 (1.3) | 2 (2.9) | 6 (2.2) |

| ȃFirst marginal | 7 (6.1) | 13 (5.7) | 7 (10.3) | 29 (10.7) |

| ȃSecond marginal | 3 (2.6) | 3 (1.3) | 4 (5.9) | 7 (2.6) |

| ȃDistal Cx | 2 (1.8) | 4 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.8) |

| ȃLeft posterolateral | 1 (0.9) | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| ȃPosterior descending (LCA) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| ȃProximal RCA | 11 (9.6) | 36 (15.9) | 6 (8.8) | 28 (10.3) |

| ȃMid-RCA | 14 (12.3) | 29 (12.8) | 5 (7.4) | 32 (11.8) |

| ȃDistal RCA | 6 (5.3) | 13 (5.7) | 2 (2.9) | 11 (4.1) |

| ȃPosterior descending | 2 (1.8) | 5 (2.2) | 1 (1.5) | 2 (0.7) |

| ȃPosterolateral (RCA) | 3 (2.6) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (1.5) | 3 (1.1) |

| Severity of lesion | ||||

| ȃ100% | 64 (56.1) | 116 (51.1) | 12 (17.6) | 44 (16.2) |

| ȃ90–99% | 42 (36.8) | 98 (43.2) | 32 (47.1) | 151 (55.7) |

| ȃ70–89% | 8 (7.0) | 13 (5.7) | 24 (35.3) | 76 (28.0) |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; Cx, circumflex artery; LAD, left anterior descending; LCA, left coronary artery; NSTE-ACS, non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome; RCA, right coronary artery; STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction.

Treatment strategy

Primary PCI for STEMI was performed in 94.7% (n = 108) and 93.8% (n = 213) of patients in groups A and B, respectively (P = 0.737). The PCI rate for NSTE-ACS was 79.4% (n = 54) and 74.5% (n = 202) for patients in groups A and B, respectively. Surgical revascularization for NSTE-ACS was performed in 13.2% (n = 9) and 22.5% (n = 61) of patients in groups A and B, respectively (P = 0.091).

In-hospital mortality

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients in group A had a statistically non-significant lower mortality rate (1.8%, n = 2) compared with those in group B (4.4%, n = 10; P = 0.210). The mortality rate for NSTE-ACS patients was similar between groups A and B [2.9% (n = 10) and 2.6% (n = 7), respectively; P = 0.873].

The overall mortality rate for ACS was 2.2% (n = 4) in group A and 3.4% (n = 17) in group B (P = 0.430).

Discussion

Our single-centre registry analysis had several important findings regarding younger patients with ACS.

First, several patients have known risk factors of ACS and one-fifth of patients had a history of previous myocardial infarction, suggesting the need to improve primary and secondary prevention in the central European region.

A previous Asian registry showed an incidence of 7.5% of acute myocardial infarction in young patients (aged ≤50 years) with STE-ACS.21 A subgroup of New Zealand and Middle East populations showed a higher incidence of previous acute myocardial infarction in ACS patients aged <50 years (10.4 and 14.1%, respectively).22,23 The large ISACS-TC registry showed an incidence of previous acute myocardial infarction of 10.7% among patients aged ≤ 45 years. In contrast, a small registry of patients with a median age of 50 years showed an incidence of previous acute myocardial infarction of 27%.24 Compared with previous studies, our study revealed a higher incidence of arterial hypertension among ACS patients aged ≤50 years, suggesting that the young patients in our registry have a substantially high risk of coronary artery disease. This is explained by the fact that the Czech Republic is a high-risk country for cardiovascular mortality (≥150/100 000 per year).25

Second, pre-hospital time delays from symptom onset were acceptable and similar in both groups of STEMI patients. Additionally, almost half of the NSTE-ACS patients had their FMC within the first 24 h.

STEMI patients have shorter pre-hospital delays compared with NSTE-ACS patients. The median total ischaemic time for STEMI patients was 185–200 min in large UK and Swedish registry studies and randomised trials.10,26 Older age, hypertension, diabetes, left circumflex artery as the culprit vessel, and female sex are associated with longer total ischaemic time.10,27 However, the total ischaemic time is significantly influenced by medical system-related variables. Therefore, analysis of the time from symptom onset to FMC can be used to explore the patients’ role in pre-hospital delays. Despite significant efforts aimed at public education and interventions with encouraging results,28,29 the large REACT trial, a 4-year multi-site community intervention study, did not observe a significant reduction in pre-hospital delay, suggesting limited power of such interventions.30

In STEMI patients, the time from symptom onset to FMC is around 70 min with additional delays observed in patients aged >65 years. In NSTEMI patients symptom onset to FMC exceeding 120 min.31–33 Erol et al.27 found that the median time from symptom onset to FMC was 47 min, which was further increased in patients aged >55 years. Canadian and Egyptian STEMI registry studies showed a median difference between the time from symptom onset of 88 min, suggesting a role of socio-economic factors.34

Our results revealed a slightly longer mean time from symptom onset to FMC for STEMI patients in both age groups. Importantly, there is no clear definition of sub-acute STEMI. European guidelines define sub-acute STEMI as presentation within 12–48 h after symptom onset.24 However, previous registries vary in their definition of sub-acute STEMI. Therefore, the use of a cut-off time of 24 h to define sub-acute STEMI may have caused a mild increase in the delay, which does not necessarily indicate an overall increase in the delay in our study population compared with available data.

Of the 6544 NSTEMI patients included in the Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry, 27.9% had a time from symptom onset to FMC ≥24 h. Predictors of pre-hospital delay were older age, female sex, atypical chest pain, dyspnoea, diabetes, and no use of emergency medical service.35 The higher all-cause mortality rate in this subgroup was independent of age, sex, and other risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and left ventricular dysfunction. Our analysis showed that a substantially higher percentage of patients with NSTE-ACS had a time from symptom onset to FMC ≥24 h, irrespective of age. Almost half (49.8%) of the patients aged >50 years and 58.9% of those aged <50 years had a time from symptom onset to FMC ≥24 h. However, according to guidelines,25 our study population also included patients with unstable angina pectoris.

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest affects 6.8–7.5% of STEMI patients and only around half of patients have prodromal symptoms. This is in accordance with our findings, in which OHCA was the first manifestation of STEMI and there was no evidence of prodromal symptoms in 3.5 and 3.8% of the patients in groups A and B, respectively.36–38

Third, angiographic findings differ between age groups. The culprit lesions are more commonly located in proximal segments,39 with the LAD artery being the most frequently involved. There is a higher incidence of LAD artery culprit lesions in younger patients (45.6–61.6%); typically in patients with STEMI.14,16,40 Our data suggest that single-vessel disease and proximal LAD culprit segment are more common in younger than middle-aged patients, irrespective of ACS type.

Finally, younger patients with ACS had a very low in-hospital mortality rate. Age is one of the factors that influences in-hospital mortality. It is reported a very low in-hospital mortality rate in patients with ACS <40 years (<1%).40 Patients aged <45 years with STEMI have an in-hospital mortality rate around 1%, however, including only patients treated by PCI.14,15 Previous national registry studies of myocardial infarction reported in-hospital mortality rates of 5.8–8.8%.26 Our analysis revealed a lower in-hospital mortality rate in younger STEMI compared with middle-aged patients, albeit without statistical significance. In contrast, the mortality rate of NSTE-ACS patients did not differ according to age.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, this was a single-centre retrospective analysis based on data collected from consecutive ACS patients over 3 years; therefore, the study had a small sample size and the number of participants varied among age groups. Second, our analyses may have been biased. Patients without sufficient anamnestic data were excluded from the analysis, although this was applicable to <10% of patients. Finally, each episode of ACS was recorded as an event; therefore, the same patient may have been included in the analysis repeatedly if another ACS has occurred within the study period. Larger multi-centre registries may need to be analysed to verify the results.

Conclusion

We performed a single-centre registry study of consecutive patients with ACS from a central European country during a 3-year follow-up. The prevalence of myocardial infarction was high among young patients. There were no significant differences in the time from symptom onset to FMC between young and middle-aged STEMI patients. A high prevalence rate of traditional risks factors of ACS and risk of a second cardiovascular event in younger patients highlight the need to improve primary and secondary prevention in our region. Although the clinical characteristics and angiographic findings differ between younger and middle-aged patients with ACS, the in-hospital mortality rate did not differ and was very low in both groups.

Contributor Information

Dávid Bauer, Department of Cardiology, Third Faculty of Medicine, Charles University and University Hospital Královské Vinohrady, Šrobárova 1150/50, Prague 100 00 and Ruská 87, Prague 100 00, Czech Republic.

Marek Neuberg, Medtronic Czechia, Partner of INTERCARDIS Project, Prosecká 852/66, 190 00 Prague, Czech Republic.

Markéta Nováčková, Department of Cardiology, Third Faculty of Medicine, Charles University and University Hospital Královské Vinohrady, Šrobárova 1150/50, Prague 100 00 and Ruská 87, Prague 100 00, Czech Republic.

Viktor Kočka, Department of Cardiology, Third Faculty of Medicine, Charles University and University Hospital Královské Vinohrady, Šrobárova 1150/50, Prague 100 00 and Ruská 87, Prague 100 00, Czech Republic.

Petr Toušek, Department of Cardiology, Third Faculty of Medicine, Charles University and University Hospital Královské Vinohrady, Šrobárova 1150/50, Prague 100 00 and Ruská 87, Prague 100 00, Czech Republic.

Funding

This study was supported by the project National Institute for Research of Metabolic and Cardiovascular Diseases (Programme EXCELES, ID Project No. LX22NPO5104), funded by the European Union—Next Generation EU. Partly the manuscript was co-funded also by the Charles University Research Program “Cooperatio Cardiovascular Sciences” and by the project Interventional Treatment of Life-Threatening Cardiovascular Diseases (INTERCARDIS), project EU No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/ 16_026/0008388, with the cooperation of project partner Medtronic Czechia.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Wu WY, Berman AN, Biery DW, Blankstein R. Recent trends in acute myocardial infarction among the young. Curr Opin Cardiol 2020;35:524–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Andersson C, Vasan RS. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in young individuals. Nat Rev Cardiol 2017;15:230–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Puricel S, Lehner C, Oberhänsli M, Rutz T, Togni M, Stadelmann Met al. Acute coronary syndrome in patients younger than 30 years—aetiologies, baseline characteristics and long-term clinical outcome. Swiss Med Wkly 2013;143:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson APet al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2020 update a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020;141:347–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zanchin C, Ledwoch S, Bär S, Ueki Y, Otsuka T, Häner JDet al. Acute coronary syndromes in young patients: phenotypes, causes and clinical outcomes following percutaneous coronary interventions. Int J Cardiol 2022;350:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bęćkowski M. Acute coronary syndromes in young women—the scale of the problem and the associated risks. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol 2015;12:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McNamara RL, Wang Y, Herrin J, Curtis JP, Bradley EH, Magid DJet al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: current state of the science: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018;137:e523–e557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McNamara RL, Wang Y, Herrin J, Curtis JP, Bradley EH, Magid DJet al. Effect of door-to-balloon time on mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:2180–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rollando D, Puggioni E, Robotti S, De Lisi A, Bravo MF, Vardanega Aet al. Symptom onset-to-balloon time and mortality in the first seven years after STEMI treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart 2012;98:1738–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Redfors B, Mohebi R, Giustino G, Chen S, Selker HP, Thiele Het al. Time delay, infarct size, and microvascular obstruction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2021;14:E009879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nguyen HL, Saczynski JS, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ. Age and sex differences in duration of Pre-hospital delay in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010;3:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ayuna A, Sultan A. Acute coronary syndrome: which age group tends to delay call for help? Egypt Heart J 2021;73:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mohan B, Bansal R, Dogra N, Sharma S, Chopra A, Varma Set al. Factors influencing prehospital delay in patients presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction and the impact of prehospital electrocardiogram. Indian Heart J 2018;70:S194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ergelen M, Uyarel H, Gorgulu S, Norgaz T, Ayhan E, Akkaya Eet al. Comparison of outcomes in young versus nonyoung patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty. Coron Artery Dis 2010;21:72–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rathod KS, Jones DA, Gallagher S, Rathod VS, Weerackody R, Jain AKet al. Atypical risk factor profile and excellent long-term outcomes of young patients treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2016;5:23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chhabra ST, Kaur T, Masson S, Soni RK, Bansal N, Takkar Bet al. Early onset ACS: an age based clinico-epidemiologic and angiographic comparison. Atherosclerosis 2018;279:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bauer D, Neuberg M, Nováčková M, Mašek P, Kočka V, Moťovská Zet al. Predictors allowing early discharge after interventional treatment of acute coronary syndrome patients. Eur Heart J Suppl 2022;24:B10–B15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno Het al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2018;39:119–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, Barthélémy O, Bauersachs J, Bhatt DLet al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent STsegment elevation. The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent STsegment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J; doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa575 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ielapi J, de Rosa S, Deietti G, Critelli C, Panuccio G, Cacia MAet al. 774ȃYoung Adults with acute coronary syndrome: still a long road ahead. Eur Heart J Suppl 2021;23:72. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tung BWL, Ng ZY, Kristanto W, Saw KW, Chan SP, Sia Wet al. Characteristics and outcomes of young patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: retrospective analysis in a multiethnic Asian population. Open Heart 2021;8:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Matsis K, Holley A, Al-Sinan A, Matsis P, Larsen PD, Harding SA. Differing clinical characteristics between young and older patients presenting with myocardial infarction. Heart Lung Circ 2017;26:566–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ahmed E, Alhabib KF, El-Menyar A, Asaad N, Sulaiman K, Hersi Aet al. Age and clinical outcomes in patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes. J Cardiovasc Dis Res 2013;4:134–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Soeiro AD, Fernandes FL, Soeiro MC, Serrano CV, Oliveira MT. Clinical characteristics and long-term progression of young patients with acute coronary syndrome in Brazil. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2015;13:370–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon Let al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. The Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J 2020;41:111–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chung SC, Gedeborg R, Nicholas O, James S, Jeppsson A, Wolfe Cet al. Acute myocardial infarction: a comparison of short-term survival in national outcome registries in Sweden and the UK. Lancet 2014;383:1305–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Erol MK, Kayikçioglu M, Yavuzgil O, Kiliçkap M, Güler A, Öztürk Öet al. Time delays in each step from symptom onset to treatment in acute myocardial infarction: results from a nation-wide TURKMI registry. Anatol J Cardiol 2021;25:294–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Herlitz J, Blohm M, Hartford M, Karlson BW, Luepker R, Holmberg Set al. Follow-up of a 1-year media campaign on delay times and ambulance use in suspected acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 1992;13:171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gaspoz JM, Unger PF, Urban P, Chevrolet JC, Rutishauser W, Lovis Cet al. Impact of a public campaign on pre-hospital delay in patients reporting chest pain. Heart 1996;76:150–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Luepker RV, Raczynski JM, Osganian S, Goldberg RJ, Finnegan JR, Hedges JRet al. Effect of a community intervention on patient delay and emergency medical service use in acute coronary heart disease: the Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment (REACT) Trial. JAMA 2000;284:60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thylén I, Ericsson M, Hellström Ängerud K, Isaksson RM, Sederholm Lawesson S. First medical contact in patients with STEMI and its impact on time to diagnosis; an explorative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nguyen HL, Gore JM, Saczynski JS, Yarzebski J, Reed G, Spencer FAet al. Age and sex differences and 20-year trends (1986 to 2005) in prehospital delay in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction; doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.957878. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2010;3:82–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ängerud KH, Lawesson SS, Isaksson RM, Thylén I, Swahn E, Ängerud KH. Differences in symptoms, first medical contact and pre-hospital delay times between patients with ST-and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2019;8:201–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Balbaa A, ElGuindy A, Pericak D, Natarajan MK, Schwalm JD. Before the door: comparing factors affecting symptom onset to first medical contact for STEMI patients between a high and low-middle income country. IJC Heart Vasc 2022;39:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cha JJ, Bae SA, Park DW, Park JH, Hong SJ, Park SMet al. Clinical outcomes in patients with delayed hospitalization for non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79:311–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Müller A, Maggiorini M, Radovanovic D, Erne P. Twenty-year trends in the characteristic, management and outcome of patients with ST–elevation myocardial infarction and out-of-hospital reanimation. Insight from the national AMIS PLUS registry 1997–2017. Resuscitation 2019;134:55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jánosi A, Ferenci T, Tomcsányi J, Andréka P. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in patients treated for ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction: incidence, clinical features, and prognosis based on population-level data from Hungary. Resusc Plus 2021;6:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nehme Z, Bernard S, Andrew E, Cameron P, Bray JE, Smith K. Warning symptoms preceding out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: do patient delays matter? Resuscitation 2018;123:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Katritsis DG, Efstathopoulos EP, Pantos J, Korovesis S, Kourlaba G, Kazantzidis Set al. Anatomic characteristics of culprit sites in acute coronary syndromes. J Interv Cardiol 2008;21:140–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maroszyńska-Dmoch EM, Wozakowska-Kapłon B. Clinical and angiographic characteristics of coronary artery disease in young adults: a single centre study. Kardiol Pol 2016;74:314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.